Abstract

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a relatively common prothrombotic adverse drug reaction of unusual pathogenesis that features platelet-activating immunoglobulin G antibodies. The HIT immune response is remarkably transient, with heparin-dependent antibodies no longer detectable 40 to 100 days (median) after an episode of HIT, depending on the assay performed. Moreover, the minimum interval from an immunizing heparin exposure to the development of HIT is 5 days irrespective of the patient’s previous heparin exposure status or history of HIT. This means that short-term heparin reexposure can be safely performed if platelet-activating antibodies are no longer detectable at reexposure baseline and is recommended when heparin is the clear anticoagulant of choice, such as for cardiac or vascular surgery. The risk of recurrent HIT 1 to 2 weeks after heparin reexposure is ∼2% to 5% and is attributable to formation of delayed-onset (or autoimmune-like) HIT antibodies that activate platelets even in the absence of pharmacologic heparin. Some studies suggest that longer-term heparin reexposure (eg, for chronic hemodialysis) may also be reasonable. However, for other antithrombotic indications that involve patients with a history of HIT (eg, treatment of venous thromboembolism or acute coronary syndrome), preference should be given to non-heparin agents such as fondaparinux, danaparoid, argatroban, bivalirudin, or one of the new direct-acting oral anticoagulants as appropriate.

Introduction

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, or HIT, represents an antibody-mediated adverse drug reaction characterized by platelet-activating immunoglobulin G (IgG) that recognize platelet factor 4 (PF4)/heparin complexes.1,2 Because HIT is a clinical-pathological disorder, diagnosis requires integrating clinical and laboratory features.3,4 HIT is a profound hypercoagulability state5 strongly associated with thrombosis.6,7 Moreover, HIT is relatively common: although it occurs in only ∼0.2% of hospitalized patients undergoing any heparin exposure,8 it is more common in certain high-risk patient populations. For example, the frequency of HIT is ∼5% in postorthopedic surgery patients receiving unfractionated heparin (UFH) for 10 to 14 days.9,10 In cardiac surgery patients who are given intraoperative UFH (for cardiopulmonary bypass [CPB]) and who receive postoperative UFH thromboprophylaxis, the frequency is ∼1% to 2%.11-15 The ubiquity of heparin and the relatively common occurrence of HIT explain the increasing numbers of patients with a history of HIT.

Several issues are relevant when considering anticoagulant management of a patient with a history of HIT. First, there are 3 conditions—cardiac surgery, vascular surgery, hemodialysis—for which UFH is the clear anticoagulant of choice. Second, there are different laboratory tests to detect anti-PF4/heparin antibodies, for which implications regarding antibody pathogenicity vary, particularly for immunoassays versus platelet activation assays.16 Third, anti-PF4/heparin antibodies are among the most transient in clinical medicine17 : a patient with HIT will generally have antibodies detectable by both PF4-dependent immunoassay and platelet activation assay at the time of acute HIT, but these antibodies can be difficult to detect as little as a few weeks or months later. Fourth, a minimum of 5 days is required to generate, or to regenerate, pathogenic platelet-activating antibodies.17,18 Thus, for certain patient populations, deliberate and planned reexposure to heparin has a rational basis. Indeed, this strategy was pioneered by Pötzsch et al,19 who described unremarkable outcomes of heparin reexposure for CPB in 10 patients with previous HIT who were antibody negative at reexposure (and who remained antibody negative 10 days after reexposure).

For many clinical situations, alternative non-heparin anticoagulation is well established (eg, treatment and/or prevention of venous thromboembolism or management of acute coronary syndrome). Thus, one can usually identify 1 or more appropriate options among the large panoply of agents, such as direct oral anticoagulants, either factor Xa (rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban) or thrombin (dabigatran) inhibiting, or a parenteral agent (anti-Xa [fondaparinux, danaparoid] or anti-IIa [bivalirudin, argatroban]). For these clinical settings, we do not discuss UFH and low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) as management options for patients with a previous history of HIT.

HIT immunobiology

The HIT immune response does not conform to the classic, adaptive immune response taught in the first-year medical school curriculum. There, the primary immune response, triggered by a first exposure to a foreign substance (antigen), triggers an early (ie, beginning about 5 to 7 days after exposure) IgM-predominant and transient response.20 The secondary immune response, after reexposure to the same antigen, begins earlier, is IgG predominant, and typically results in long-lasting antibody detectability.

In the case of HIT, any immunizing exposure to heparin, whether triggered by the first exposure to heparin or any subsequent reexposure, leads to a relatively rapid immune response, with detectability of anti-PF4/heparin antibodies occurring a median of 4 days after exposure21,22 and onset of HIT occurring at least 1 day later (ie, occurrence within the characteristic day 5 to 10 window of HIT, in which day 0 indicates the presumed immunizing heparin exposure).17,21 There does not seem to be any tendency to an earlier, more rapid immune response, including in patients who have had previous heparin exposures17 or even a previous history of HIT.18,23-25 (Although there is a syndrome named rapid-onset HIT, it does not reflect a new immune response but is simply the triggering of an acute platelet count decrease in a patient who already has circulating HIT antibodies associated with a recent exposure to heparin.17,26 )

Case 1: patient with remote history of HIT requiring urgent cardiac surgery

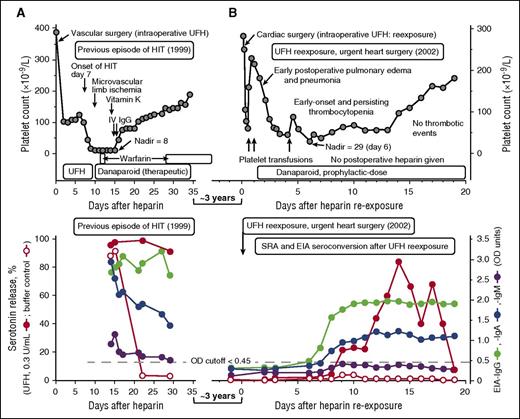

A 51-year-old male, who was the index case in the original report of congenital erythroblastic multinuclearity associated with a positive acidified serum test27 (and was listed as patient 8 in our report18 describing outcomes of heparin reexposure in patients with a history of HIT), developed severe HIT (platelet count nadir, 8 × 109/L) and was successfully treated with therapeutic-dose danaparoid (Figure 1A, upper panel). Tests for HIT antibodies were strongly positive (Figure 1A, lower panel). Three years later, he developed acute pulmonary edema secondary to flail mitral valve, requiring urgent cardiac surgery. Hematology consultation was requested because of the history of HIT. There was no time to perform repeat HIT antibody testing before cardiac surgery. What treatment was recommended?

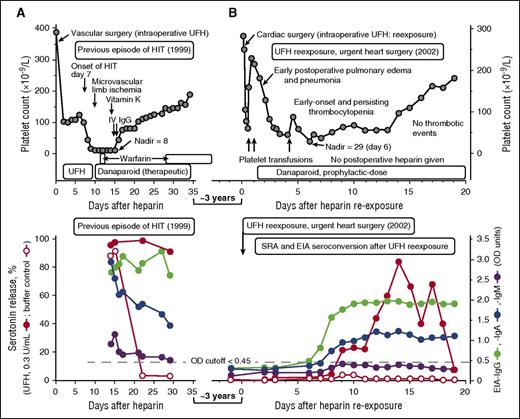

UFH reexposure for urgent cardiac surgery in a patient with a history of HIT. Patient 8 in Table 1. (A) Summary of the clinical (upper panel) and serological (lower panel) features of the patient’s previous episode of HIT (1999). The patient had unusually severe HIT but ultimately did well with therapeutic-dose danaparoid sodium (no new or progressive thrombosis and no ischemic limb loss). The patient tested strongly positive in the SRA, EIA-IgG, and EIA-IgA, and weakly positive in the EIA-IgM tests. (B) Summary of the clinical (upper panel) and serological (lower panel) features of the patient’s UFH reexposure to permit urgent cardiac surgery (2002). After reexposure to UFH, the patient had early-onset and persistent thrombocytopenia (platelet count nadir, 29 × 109/L on POD 6), but this was not related to HIT (the SRA tested negative on POD6). The prolonged period of postoperative thrombocytopenia was probably also unrelated to subsequent formation of platelet-activating antibodies, given that the platelet count recovery occurred as the patient was developing a strongly positive SRA, and given that the buffer control (ie, at 0 U/mL UFH) reactivity in the SRA remained negative throughout the postoperative period and also remained negative in the presence of danaparoid (data indicating absence of danaparoid cross-reactivity not shown). IV, intravenous.

UFH reexposure for urgent cardiac surgery in a patient with a history of HIT. Patient 8 in Table 1. (A) Summary of the clinical (upper panel) and serological (lower panel) features of the patient’s previous episode of HIT (1999). The patient had unusually severe HIT but ultimately did well with therapeutic-dose danaparoid sodium (no new or progressive thrombosis and no ischemic limb loss). The patient tested strongly positive in the SRA, EIA-IgG, and EIA-IgA, and weakly positive in the EIA-IgM tests. (B) Summary of the clinical (upper panel) and serological (lower panel) features of the patient’s UFH reexposure to permit urgent cardiac surgery (2002). After reexposure to UFH, the patient had early-onset and persistent thrombocytopenia (platelet count nadir, 29 × 109/L on POD 6), but this was not related to HIT (the SRA tested negative on POD6). The prolonged period of postoperative thrombocytopenia was probably also unrelated to subsequent formation of platelet-activating antibodies, given that the platelet count recovery occurred as the patient was developing a strongly positive SRA, and given that the buffer control (ie, at 0 U/mL UFH) reactivity in the SRA remained negative throughout the postoperative period and also remained negative in the presence of danaparoid (data indicating absence of danaparoid cross-reactivity not shown). IV, intravenous.

Natural history of HIT antibody seroreversion

Transience of HIT antibodies (seroreversion) is one of the remarkable features of HIT. The time to nondetectability of HIT antibodies after an episode of HIT ranges from 40 to 100 days, depending on the assay performed (serotonin release assay [SRA] and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [EIA]-IgG, respectively).17 There is considerable biological variability around these point estimates: some patients develop negative or weakly positive results within 1 or 2 weeks after HIT. Indeed, platelet counts can recover despite continued heparin administration in patients with acute HIT,22,28 with waning of HIT antibody levels despite ongoing administration of heparin.22

Approach to managing case 1

On the basis of the known natural history of HIT antibody seroreversion and the need for urgent cardiac surgery 3 years after HIT, I (T.E.W.) viewed as negligible the possibility of clinically significant HIT antibodies still being present. I therefore recommended the usual intraoperative anticoagulation with UFH, with postoperative thromboprophylaxis with danaparoid sodium,29 a mixture of anticoagulant glycosaminoglycans (predominantly heparan sulfate) approved in many jurisdictions (although not in the United States) for treatment of HIT. Figure 1B (upper panel) shows the postoperative clinical course, which was characterized by early postoperative pulmonary edema and/or pneumonia and (non-HIT-related) early-onset and persisting thrombocytopenia, with platelet count recovery 2 weeks later. Figure 1A-B (lower panels) compare the HIT antibody test results at the time of previous HIT (strongly positive SRA, EIA-IgG, and EIA-IgA with a weak positive EIA-IgM), with the results following reexposure. Despite repeat seroconversion (by EIA-IgG, EIA-IgA, and SRA), there was no new platelet count decrease that occurred in association with this seroconversion, and serum-induced platelet activation at 0 U/mL UFH was negligible. The patient ultimately did well with no postoperative thrombosis.

Case 2: patient with positive EIA but negative SRA requiring cardiac surgery

A 56-year-old female had a previous history of HIT (without associated thrombosis) that complicated the use of therapeutic-dose dalteparin for new-onset atrial fibrillation; HIT was diagnosed on the basis of a 57.4% platelet count decrease to 77 × 109/L (nadir) and no other plausible explanation (4Ts score, 6 points). The patient tested strongly positive by polyspecific EIA (>4.0 optical density [OD] units) and had a positive SRA. The patient had mitral valve regurgitation, and valve repair was recommended. Subsequent repeat testing for HIT antibodies using another blood sample obtained 24 weeks after HIT diagnosis showed that the SRA was now negative, but the EIA-IgG remained positive (0.85 OD units). What treatment was recommended?

Risk of recurrent HIT with positive EIA and negative platelet activation assay at baseline

EIA-positive/SRA-negative patients who receive heparin do not develop acute HIT.9,14,16,30 Accordingly, we18 and others31 have used heparin with good results in patients with a previous history of HIT who tested negative in a sensitive (washed platelet) activation test, such as the SRA or heparin-induced platelet activation (HIPA) test but who continued to test EIA positive.

Table 1 presents our updated experience with deliberate planned UFH reexposures for cardiac or vascular surgery in patients with a previous history of HIT and summarizes our previous experience,18 with the addition of 2 more recent cases (including case 2 presented above).32 Of the 20 patient reexposures summarized, 10 featured a positive EIA-IgG at reexposure baseline. None of these 10 EIA-positive patients developed apparent HIT, either at the time of UFH reexposure or during the later postoperative period.

Table 1 indicates that a positive EIA at reexposure baseline is not associated with an appreciably increased risk of subsequent seroconversion to a positive SRA or more strongly positive EIA (defined as >100% increase in OD). Of the 10 patients with a baseline negative EIA, 4 patients (40%) developed subsequent SRA seroconversion, and 6 patients (60%) developed EIA seroconversion. In contrast, SRA and EIA seroconversion occurred in 5 (50%) of 10 and 7 (70%) of 10, respectively, of the patients who tested EIA positive at reexposure baseline.

As will be discussed later (see “What is the risk of recurrent HIT with heparin reexposure for cardiac or vascular surgery?”), in our 20-patient case series, we observed only 1 case of recurrent HIT, but ironically this occurred in 1 of the 10 patients who tested negative by EIA for anti-PF4/heparin antibodies at preoperative reexposure baseline.

Approach to managing case 2

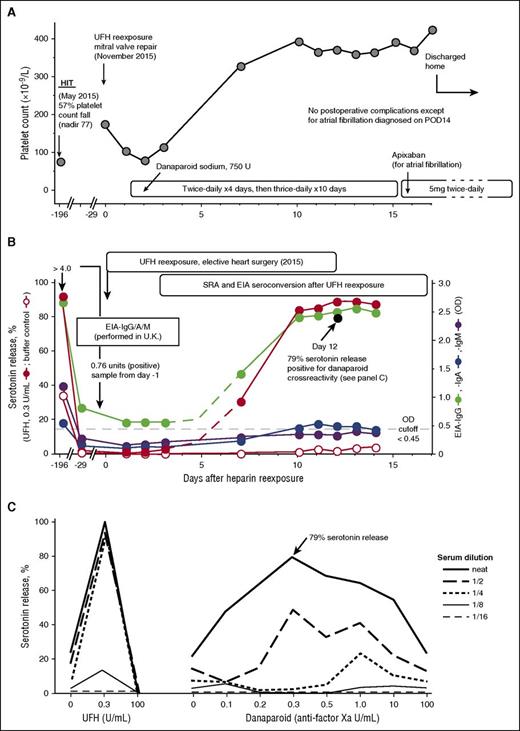

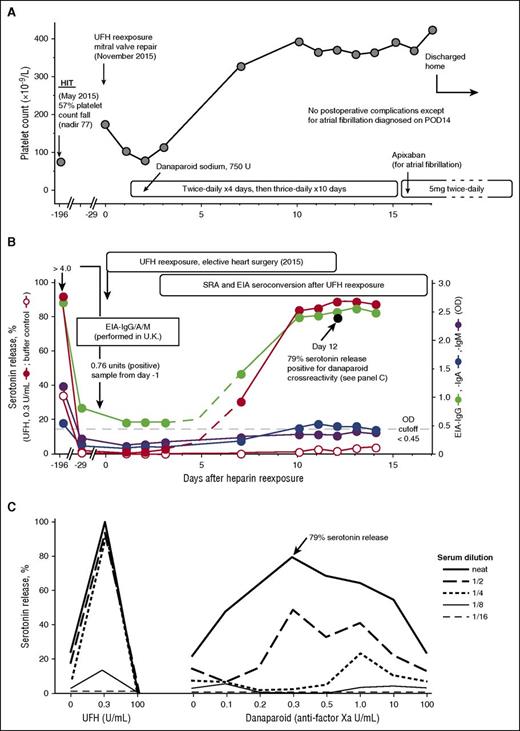

I (J.A.M.A.) recommended the usual intraoperative anticoagulation with UFH and postoperative thromboprophylaxis with danaparoid for the patient (patient 22 in Table 1). The mitral valve repair proceeded uneventfully. Figure 2A shows the postoperative platelet count changes. Although there were no platelet count changes suggestive of HIT (eg, a >30% platelet count decrease after postoperative day 4 [POD4]), the patient did develop atrial fibrillation on POD14. The patient was switched from subcutaneous danaparoid to oral apixaban. No thrombosis was evident.

UFH reexposure for cardiac surgery in a patient with history of HIT who is now SRA negative but EIA-IgG positive. Patient 22 in Table 1. (A) Clinical summary. The patient had HIT in May 2015. UFH reexposure to permit mitral valve repair was performed in November 2015. The patient received postoperative anticoagulation with danaparoid sodium. The postoperative course was unremarkable except for atrial fibrillation (POD14), which was treated with subcutaneous danaparoid followed by oral apixaban (continued at discharge). (B) Serological summary (including seroconversion after reexposure). The patient tested strongly positive for HIT antibodies at HIT diagnosis, including EIA-IgG/IgA/IgM >4.00 OD units (PF4 Enhanced, Immucor GTI Diagnostics, Waukesha, WI), EIA-IgG (McMaster Platelet Immunology Laboratory) 2.67 OD units (90% inhibition by high heparin), and a positive SRA (peak serotonin release, 92% at 0.1 U/mL UFH, with 34% serotonin release at buffer control). At 24-week follow-up (day −29), the SRA tested negative (<10% serotonin release), but the EIA-IgG remained positive at 0.85 OD units (68% inhibition by high heparin). After reexposure to UFH, the patient developed repeat strongly positive seroconversion by SRA and EIA-IgG and weakly positive seroconversion by EIA-IgA. The buffer control reactivity in the SRA remained negative throughout the postoperative period. Later testing for danaparoid cross-reactivity (POD12 blood sample) showed a peak of 79% serotonin release in the presence of danaparoid (panel C). (C) Positive testing for danaparoid cross-reactivity. POD12 serum was later tested for danaparoid cross-reactivity; patient serum-induced serotonin-release at buffer control (ie, at 0 U/mL UFH) was weakly positive (21% release), which increased to a peak of 79% serotonin release at 0.3 anti-factor Xa U/mL (final) danaparoid, thus confirming in vitro cross-reactivity.

UFH reexposure for cardiac surgery in a patient with history of HIT who is now SRA negative but EIA-IgG positive. Patient 22 in Table 1. (A) Clinical summary. The patient had HIT in May 2015. UFH reexposure to permit mitral valve repair was performed in November 2015. The patient received postoperative anticoagulation with danaparoid sodium. The postoperative course was unremarkable except for atrial fibrillation (POD14), which was treated with subcutaneous danaparoid followed by oral apixaban (continued at discharge). (B) Serological summary (including seroconversion after reexposure). The patient tested strongly positive for HIT antibodies at HIT diagnosis, including EIA-IgG/IgA/IgM >4.00 OD units (PF4 Enhanced, Immucor GTI Diagnostics, Waukesha, WI), EIA-IgG (McMaster Platelet Immunology Laboratory) 2.67 OD units (90% inhibition by high heparin), and a positive SRA (peak serotonin release, 92% at 0.1 U/mL UFH, with 34% serotonin release at buffer control). At 24-week follow-up (day −29), the SRA tested negative (<10% serotonin release), but the EIA-IgG remained positive at 0.85 OD units (68% inhibition by high heparin). After reexposure to UFH, the patient developed repeat strongly positive seroconversion by SRA and EIA-IgG and weakly positive seroconversion by EIA-IgA. The buffer control reactivity in the SRA remained negative throughout the postoperative period. Later testing for danaparoid cross-reactivity (POD12 blood sample) showed a peak of 79% serotonin release in the presence of danaparoid (panel C). (C) Positive testing for danaparoid cross-reactivity. POD12 serum was later tested for danaparoid cross-reactivity; patient serum-induced serotonin-release at buffer control (ie, at 0 U/mL UFH) was weakly positive (21% release), which increased to a peak of 79% serotonin release at 0.3 anti-factor Xa U/mL (final) danaparoid, thus confirming in vitro cross-reactivity.

Figure 2B depicts the results of testing serial blood samples for HIT antibodies, which showed EIA-IgG and SRA seroconversion by POD7, followed by EIA-IgA seroconversion on POD10. Peak SRA reactivity was observed on POD13, with 89% serotonin release seen at 0.3 U/mL. Despite the strong SRA seroconversion, the patient’s clinical course was judged successful, without recurrence of HIT. Of note, cross-reactivity for danaparoid was shown using a POD12 sample (Figure 2C), but the clinical significance of this result is uncertain.

Case 3: patient with positive SRA at time of planned UFH reexposure

A 76-year-old woman, listed as patient 21 in Table 1, developed HIT while receiving UFH for medical thromboprophylaxis and required cardiac surgery 12 weeks later to remove renal carcinoma invading the inferior vena cava and right atrium. Her EIA-IgG remained strongly positive (2.58 OD units) as did her SRA (99% serotonin release at 0.3 IU/mL UFH). What management options could be considered?

Management of a patient with a positive platelet activation assay who requires cardiac or vascular surgery

Three different approaches have been described to manage a patient known to have a positive washed platelet activation assay (either the SRA or HIPA test) at the time of cardiac or vascular surgery and in whom further watchful waiting in anticipation of a negative assay is judged infeasible because of urgent/emergent need for surgery: (1) intraoperative anticoagulation with a non-heparin anticoagulant, especially bivalirudin33,34 ; (2) intraoperative anticoagulation with UFH combined with a platelet inhibitor such as iloprost (prostacyclin analog)35 ; and (3) therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) to convert the patient from seropositive to seronegative32 or to reduce EIA titers.36 Although all 3 approaches have their merits, my (T.E.W.) approach has been to permit the surgeons to use UFH (their usual practice) to avoid the inherent complications of learning to use a nonstandard anticoagulant for a complex procedure such as CPB, usually in an urgent/emergent setting. Moreover, using bivalirudin for CPB has risks (eg, proteolysis of bivalirudin within stagnant blood, which results in clotting within the surgical field, clamped native vessels and/or grafts, or within the CPB tubing and/or reservoir37,38 ) as does iloprost (eg, severe hypotension38 ).

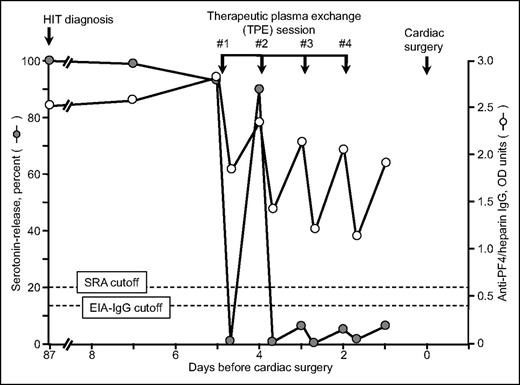

Thus, for case 3, where clinical circumstances did not allow waiting for the SRA to become negative, I (T.E.W.) used TPE to convert the patient from SRA-positive to SRA-negative status.32 Interestingly, although 4 plasma exchanges achieved SRA-negative status, the patient continued to have a moderately positive EIA-IgG (Figure 3). The patient underwent cardiac surgery without developing clinical evidence of acute HIT; in addition, the patient did not show evidence of postoperative seroconversion.

Serial SRA and IgG-specific anti-PF4/heparin EIA test results in relation to 4 therapeutic plasma exchange sessions performed on 4 consecutive days (last therapeutic plasma exchange performed 2 days before cardiac surgery using heparin). This is patient 21 in Table 1. Reprinted from Warkentin et al32 with permission.

Serial SRA and IgG-specific anti-PF4/heparin EIA test results in relation to 4 therapeutic plasma exchange sessions performed on 4 consecutive days (last therapeutic plasma exchange performed 2 days before cardiac surgery using heparin). This is patient 21 in Table 1. Reprinted from Warkentin et al32 with permission.

To confirm that TPE-induced seroreversion to a negative SRA would always precede EIA seroreversion, we performed serial dilutions of 15 different strongly positive HIT sera and showed that seroreversion to a negative SRA always occurred before an EIA became negative.32 Thus, performing serial TPE to the end point of a negative EIA would mean that several additional plasma exchanges would be performed versus the minimum required to achieve a negative SRA.

Welsby and colleagues36 used intraoperative TPE to decrease anti-PF4/heparin antibody levels in patients with recent HIT who were given UFH for heart transplantation despite being EIA positive (but platelet aggregation test negative) at surgery. None of the patients developed recurrent HIT using this management strategy.

What is the risk of recurrent HIT with heparin reexposure for cardiac or vascular surgery?

Table 1 shows that recurrent HIT developed in only 1 patient (patient 17), for a frequency of 5% (1 of 20) in our updated case series. Postoperative heparin was not given to any of the 20 patients; rather, anticoagulation was administered with danaparoid (n = 10), fondaparinux (n = 5), warfarin (n = 1), clopidogrel/aspirin (n = 2), or no postoperative anticoagulation (n = 2). The lack of postoperative heparin might suggest that the risk of recurrent HIT should be very low, perhaps negligible, given that the patient would not be receiving heparin when a recurrent immune response might be forming. What then explains the recurrence of HIT in patient 17?

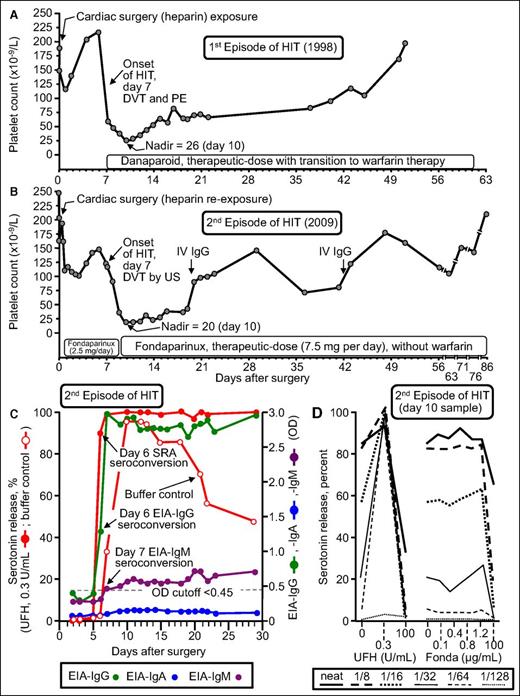

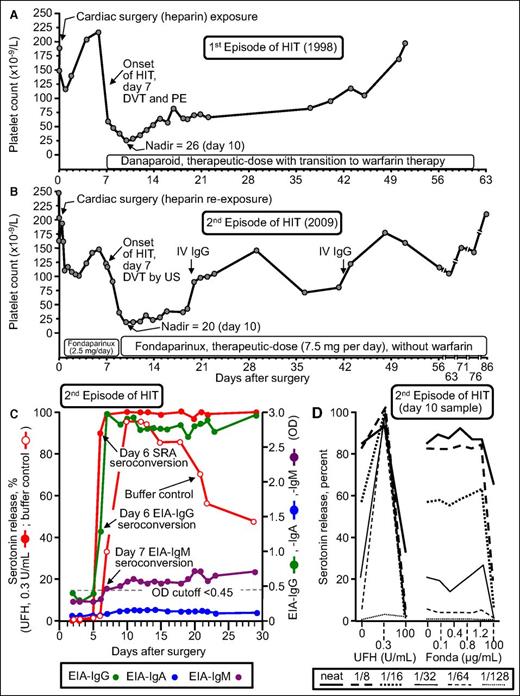

Figure 4 summarizes the clinical and serological features of patient 17 who developed recurrent HIT. He developed an unexpected 86.5% platelet count decrease (from 148 to 20) that began on POD7 while receiving fondaparinux thromboprophylaxis; the patient was shown to have an asymptomatic lower-limb deep vein thrombosis by ultrasound (4Ts score, 8 points). Of note, the patient formed strong HIT antibodies that activated platelets in vitro even in the absence of pharmacologic heparin (Figure 4, open circles). Moreover, there was no cross-reactivity with fondaparinux. Thus, this patient had the serological features of delayed-onset HIT39,40 (also called autoimmune HIT41 ). However, this patient was unusual in another respect: both of his episodes of HIT (in 1998 and 2009) were characterized by the phenomenon of persisting HIT (ie, both HIT episodes lasted for more than 4 weeks before platelet count recovery, which is a rare but recognized course of HIT).42,43 In addition, the patient developed a generalized maculopapular rash (not a reported feature of HIT). Thus, it is difficult to generalize the outcome of this most unusual patient case. Nevertheless, our overall observed frequency of HIT of 5% is in keeping with a recent literature review by Dhakal et al.44 They reviewed 141 reexposure episodes in 136 patients who had a history of HIT and identified 3 patients with recurrent HIT for an overall frequency of 2.1% (95% CI, 0.73% to 6.07%).

Patient with recurrent HIT after UFH reexposure for elective heart surgery. Patient 17 in Table 1. (A) First episode of HIT (1998) complicated by symptomatic deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE). (B) Second episode of HIT after intraoperative UFH rechallenge (2009). The patient developed HIT on POD7, with associated asymptomatic DVT shown by venous ultrasound (US). (C) Timing of SRA and EIA seroconversion after UFH reexposure. Both the EIA-IgG and SRA became positive on POD6. IgM seroconversion occurred on POD7. Serotonin release at buffer control (ie, at 0 U/mL UFH) was very strong (>90% from POD10 to POD13), which explains why the patient developed HIT despite not receiving postoperative heparin. (D) Assessment of UFH- and fondaparinux-dependent platelet activation in the presence of patient serum at various dilutions. Strong serum-induced platelet activation (>80% serotonin release) was observed at 0 U/mL UFH (ie, buffer control), using neat and 1/8 diluted serum; strong heparin-dependent platelet activation was shown by the increase in serotonin release at 0.3 U/mL UFH compared with buffer control at higher dilutions of serum (1/16, 1/32, 1/64, 1/128). The absence of fondaparinux-dependent platelet activation argues against fondaparinux cross-reactivity as an explanation for the patient’s persisting thrombocytopenia. Fonda, fondaparinux. Reprinted from Warkentin et al18 with permission.

Patient with recurrent HIT after UFH reexposure for elective heart surgery. Patient 17 in Table 1. (A) First episode of HIT (1998) complicated by symptomatic deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE). (B) Second episode of HIT after intraoperative UFH rechallenge (2009). The patient developed HIT on POD7, with associated asymptomatic DVT shown by venous ultrasound (US). (C) Timing of SRA and EIA seroconversion after UFH reexposure. Both the EIA-IgG and SRA became positive on POD6. IgM seroconversion occurred on POD7. Serotonin release at buffer control (ie, at 0 U/mL UFH) was very strong (>90% from POD10 to POD13), which explains why the patient developed HIT despite not receiving postoperative heparin. (D) Assessment of UFH- and fondaparinux-dependent platelet activation in the presence of patient serum at various dilutions. Strong serum-induced platelet activation (>80% serotonin release) was observed at 0 U/mL UFH (ie, buffer control), using neat and 1/8 diluted serum; strong heparin-dependent platelet activation was shown by the increase in serotonin release at 0.3 U/mL UFH compared with buffer control at higher dilutions of serum (1/16, 1/32, 1/64, 1/128). The absence of fondaparinux-dependent platelet activation argues against fondaparinux cross-reactivity as an explanation for the patient’s persisting thrombocytopenia. Fonda, fondaparinux. Reprinted from Warkentin et al18 with permission.

Table 1 shows that the frequency of EIA seroconversion in our case series was 13 (65%) of 20, a rate similar to that in other populations after cardiac surgery.11,13,14,45,46 However, 9 (69.2%) of the 13 EIA-IgG seroconverting patients also showed SRA seroconversion, a proportion much higher than expected (∼5% to 20%).14,45,46 This suggests that patients with a history of HIT are more likely to develop platelet-activating antibodies within their anti-PF4/heparin response and thus to develop HIT if they receive postoperative heparin (not recommended), or if they develop strongly reactive autoimmune-like platelet-activating antibodies (substantial serotonin release at buffer control), a phenomenon we discuss further.

Autoimmune-like HIT antibodies with positive buffer control reactivity as a marker for risk of recurrent HIT

Table 2, which summarizes the positive SRA results among the 13 SRA-seroconverting patients, shows that patient 17, who developed recurrent HIT, exhibited the strongest serum-induced serotonin release at buffer control (ie, 0 U/mL UFH). This in vitro phenomenon is correlated with clinical features of various types of HIT such as delayed-onset HIT,39,40 persisting HIT,43 fondaparinux-induced HIT,47 and spontaneous HIT syndrome,48 and we believe this serological profile explains the potential for recurrent HIT beginning 5 to 10 days after heparin reexposure despite no further heparin being given. These antibodies prompt platelet activation via (non-heparin) platelet-associated glycosaminoglycans.49

What are the temporal and serological features of a recurrent anti-PF4/heparin immune response?

In addition to the high frequency of a positive SRA, there are other noteworthy features of the recurrent anti-PF4/heparin immune response. For example, the timing of antibody formation is no different than in the primary HIT-related immune response.18 For the patients shown in Table 1 for whom evidence of an anti-PF4/heparin immune response was documented after heparin reexposure, the earliest day of detectability of antibodies was POD5 (patient 18), with a median time to a positive SRA observed on POD8 (range, POD6 to POD11), for EIA-IgG on POD7 (range, POD6 to POD9), EIA-IgA POD9 (range, POD7 to POD10), and EIA-IgM POD8 (range, POD5 to POD9). This timing of seroconversion is no sooner than that reported in other patients exhibiting anti-PF4/heparin seroconversion after heparin exposure, either with or without overt HIT.17,21,22 Interestingly, available data regarding antibody isotypes (IgG, IgA, IgM) for the initial episode of HIT, as well as for the subsequent repeat seroconversion after UFH reexposure, never showed formation of a new isotype that had not been present during the time of previous HIT, although the converse was not true (ie, in 3 of 8 patients, an isotype detected at previous HIT was not present at repeat seroconversion).

Recommended management including postoperative platelet count monitoring

Given the risk of recurrent HIT in patients who undergo planned reexposure to UFH, even when postoperative heparin is not administered, we recommend platelet count monitoring once per day (or once every other day), not only during the first 4 postoperative days (when risk of recurrent HIT is biologically implausible), but especially during the POD5-to-POD10 window during which recurrent HIT could occur (Table 3). We also recommend collecting and storing serial postoperative blood samples to permit serological investigations, if needed, to determine whether there has been any occurrence of unexpected thrombocytopenia (which is not usually performed in real time). We would treat any platelet count decrease >30% that occurs during the day 5 to day 14 time period as presumptive HIT, as was done for patient 17 (Figure 4). This patient was treated promptly for HIT (increase in fondaparinux from prophylactic to therapeutic dose) and the ultimate clinical course was favorable, with recovery of thrombocytopenia and lack of progression of subclinical deep vein thrombosis.

How I would treat a mechanical heart valve replacement patient with a history of HIT

The above 3 illustrative cases were real. But how would we treat the following (theoretical) case? Consider a patient with a history of definite previous HIT with no detectable HIT antibodies who now requires cardiac surgery for replacement of a mechanical heart valve. The patient is receiving chronic warfarin therapy. Classic bridging with UFH or LMWH is problematic because of the risk of retriggering HIT antibodies before surgery.

Our plan would be to hold warfarin for 2 days before surgery and give prothrombin complex concentrates immediately before surgery, along with a small dose of intravenous vitamin K. This would avoid the need for preoperative heparin bridging. Prothrombin complex concentrates contain heparin,50 so we would avoid giving them a few days before surgery.) The cardiac surgery would then proceed with usual heparinization and protamine reversal. During the postoperative period, once hemostasis was apparent, we would recommend that intravenous UFH be given, starting at a low dose (eg, 500 U/h), with gradual increase over the next 3 to 4 days. Although this would seem to break the rule about avoiding UFH other than for surgery, in this case, UFH is the preferred anticoagulant for mechanical prostheses, and it would (in theory) be safe for the first 96 hours during the early stages of warfarin therapy. Then, in the evening of the fourth day, we would begin dosing with 5 mg fondaparinux and then give 7.5 mg the morning of the fifth day, with the plan being to continue fondaparinux once per day while continuing warfarin overlap (an alternative anticoagulant option would be danaparoid, if available). Platelet count monitoring for HIT recurrence would be performed until at least POD10.

Hemodialysis

This article has focused on managing the patient with a previous history of HIT who requires cardiac or vascular surgery. But what about the other clinical setting for which UFH is the anticoagulant agent of choice—hemodialysis? Hemodialysis and other forms of renal replacement therapy have an important distinguishing feature from cardiac/vascular surgery, namely that they are not a one-off exposure but rather a therapy that will require continuous or intermittent heparin exposure for a period of at least several days, if not weeks, months, or indefinitely. Thus, acute hemodialysis and other renal replacement therapy will generally require anticoagulation with a non-heparin anticoagulant (eg, argatroban,51 danaparoid,52 bivalirudin,53 or fondaparinux54-56 ), which at least in theory can be continued indefinitely. However, the expense and inconvenience of using an alternative non-heparin anticoagulant for intermittent hemodialysis 3 times per week on an indefinite basis has led some investigators57-59 to resume UFH anticoagulation after HIT antibody seroreversion.

Hartman et al57 reported no instances of HIT recurrence in 3 patients who resumed anticoagulation with LMWH agent nadroparin; the patients had undergone hemodialysis with lepirudin after HIT was diagnosed because of heparin-induced anaphylactoid reactions during hemodialysis, which led to recognition of HIT. More recently, Wanaka et al58,59 reported unremarkable resumption of UFH anticoagulation for hemodialysis in 14 patients after antibody seroreversion; however, HIT recurred in their fifteenth patient who underwent UFH reexposure for hemodialysis.59 This 69-year-old male developed recurrent thrombocytopenia and circuit clotting on the fifth hemodialysis session (ie, day 10) after resumption of UFH, which is consistent with our own experience that HIT recurrence (from negative SRA baseline) does not occur more quickly than what is usually seen with typical-onset HIT. On the basis of this experience, it would seem reasonable to consider resumption of UFH in a patient with previous HIT who is undergoing chronic hemodialysis, although this would require a thorough discussion of the risks and benefits with the patient. If UFH were to be resumed, it would be prudent to measure pre- and postdialysis platelet counts and to collect pre- and postdialysis blood samples for testing for HIT antibodies for at least 2 weeks after resumption of UFH or LMWH anticoagulation. Although the risk of recurrent HIT is likely to be low (∼5% frequency), vigilance for HIT recurrence is key. On theoretical grounds, it might be reasonable to infuse UFH slowly (over 30 minutes) from days 5 to 14 after reinitiating UFH rather than as a bolus because of the potential for an anaphylactoid reaction with bolus UFH administration.60 We do not have any personal experience with resuming UFH or LMWH in this clinical setting. A further consideration is that later recurrence of HIT is possible if intercurrent surgery or another acute event resets the HIT immunological clock.42

How dangerous is the administration of UFH to a patient with SRA-positive subacute HIT?

Subacute HIT is defined as a patient who has detectable platelet-activating HIT antibodies but who has a normal platelet count.31,38 Such a clinical situation will usually occur for a relatively short period of time (several weeks) after recovery from an episode of HIT, or in a patient who has formed (platelet-activating) HIT antibodies after UFH exposure but in whom HIT might not have occurred (perhaps because postoperative heparin was not being given). What are the potentially adverse outcomes if heparin (UFH or LMWH) is administered to such a patient?

It is clear that administration of heparin in therapeutic doses (eg, 5000 U bolus of UFH17,60 ; 12 000 U injection of LMWH dalteparin61 ) can result in abrupt platelet count decrease (rapid-onset HIT), sometimes with a life-threatening anaphylactoid reaction.59,60 Although rare, acute intraoperative thrombosis has also been reported when UFH (∼5000 U) has been administered to a patient undergoing vascular surgery.62 (Interestingly, patient cases have been reported in which UFH to permit emergency thromboembolectomy did not result in adverse consequences.63 ) To our knowledge, there are no reports of patients who have experienced adverse consequences of UFH administered for CPB in which the explanation was unrecognized presence of (platelet-activating) HIT antibodies at time of cardiac surgery. In fact, a case was reported64 in which a patient had an uneventful intraoperative course, and it was subsequently proven that the patient was in the early stages of acute HIT when UFH was administered for CPB. This suggests that the very large doses of UFH routinely given during cardiac surgery might be relatively protective against adverse consequences of HIT antibodies. Supportive data include observations in patients with a ventricular assist device who have acute or recent HIT and who underwent heart transplantation with UFH irrespective of their anti-PF4/heparin antibody status; although the authors found that antibody-positive patients had lower postoperative platelet counts compared with controls, none developed intraoperative thrombosis.65 HIT is a disorder characterized by many paradoxes, and it is not inconceivable that the risk of catastrophic consequences of high doses of UFH administered during cardiac surgery in a patient with HIT antibodies are much lower than one might surmise.

Summary

Table 3 summarizes concepts regarding heparin reexposure and our recommendations for patients with a previous history of HIT.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of the McMaster Platelet Immunology Laboratory in performing the testing for HIT antibodies, both PF4-dependent immunoassays and the SRA washed platelet assay, to identify the serological patterns that underlie the HIT and non-HIT-associated anti-PF4/heparin immune responses, both serconversion and seroreversion, especially the work of Jo-Ann I. Sheppard (who also prepared the figures) and Jane C. Moore. T.E.W. thanks John G. Kelton and Andreas Greinacher for their ongoing support.

Authorship

Contribution: T.E.W. wrote the initial draft, contributed cases 1 and 3, and summarized the data for the first 2 tables; J.A.M.A. contributed case 2; and both authors revised the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: T.E.W. has received lecture honoraria from Pfizer Canada and Instrumentation Laboratory, royalties from Taylor & Francis (Informa), and consulting fees and research funding from W.L. Gore and Instrumentation Laboratory and has provided expert witness testimony relating to HIT. The remaining author declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Theodore E. Warkentin, Hamilton General Hospital, Room 1-270B, 237 Barton St East, Hamilton, ON L8L 2X2, Canada; e-mail: twarken@mcmaster.ca.