To the editor:

The challenging issue of anticoagulant therapy in patients with inherited bleeding disorders was highlighted by Martin and Key in a recent article in Blood.1 In this field of limited evidence, expert opinions are of importance for guidance into clinical practice. We believe that the enclosed additional considerations are useful because a few newer concepts on the management of cardiovascular diseases in the general population should also be considered in persons with hemophilia (PWH). Our suggestions are based on a mixture of personal clinical experience, laboratory data, and extrapolation of data from the nonhemophilia population to PWH.

Atrial fibrillation in hemophilia

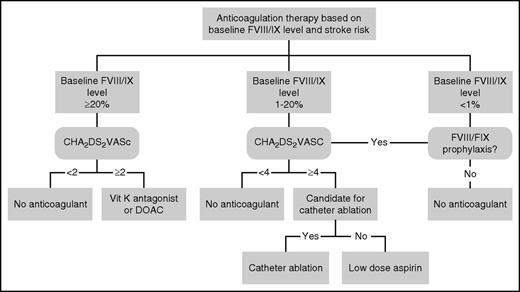

For PWH with atrial fibrillation, we refer to Figure 1 from the previous publication in which the CHADS2 (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 years, diabetes mellitus, prior stroke or transient ischemic attack or thromboembolism) score and factor plasma levels were used to make an individualized decision.2 Since then, several important changes necessitate an update of the flowchart (Figure 1). First, the risk stratification for considering anticoagulation is now preferably based on the CHA2DS2VASC (CHADS2–vascular disease, age 65-74 years, sex category) score.3 In PWH, the CHA2DS2VASC score probably overestimates the risk for embolic stroke, a level of at least 3 being considered high risk by an expert panel.4 However, as score items such as female sex, peripheral arterial disease, and age >75 years will infrequently be seen in PWH, we maintain the general threshold of 2 in order to consider anticoagulation in mild PWH. To date, there are no data to validate any threshold in PWH. Considering the fact that in real life, hemophilia treaters do not use a common CHA2DS2VASC threshold to start anticoagulant therapy in PWH,5 we believe that our suggestion provides uniformity. Second, we tend to lower the factor VIII/IX (FVIII/IX) plasma level threshold considered safe for oral anticoagulation from 30% to 20%. This minimum trough FVIII/FIX level considered safe for anticoagulation is based on experience in several patients, expert opinion, and laboratory data. The amount of published data on PWH who received anticoagulation is very small. There are reports of spontaneous hemorrhage (other than in joints) in PWH receiving warfarin and clotting factor levels <20%.5,6 On the other hand, the safe use of anticoagulation in PWH with clotting factor levels >20% has been reported.7,8 However, long-term data on the use of vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) in PWH are lacking. Laboratory data, as indicated in the last paragraph of this section, indicate that the majority of PWH with FVIII levels <20% have low endogenous thrombin potential (ETP) levels. From this point of view, we do not recommend anticoagulation in them. We and others have uneventfully managed oral anticoagulation in several patients with trough factor FVIII levels between 20% and 30% (although our experience is based on <10 cases).5,7 It should be noted that this threshold should be considered very carefully in each patient, based on bleeding phenotype, thrombotic risk, and (not least of all) logistics.

Recommendation for anticoagulant therapy in hemophilia patients with atrial fibrillation. Compared with our previous flowchart,2 notice the following adaptations: baseline FVIII/FIX changed from 30% to 20%; CHADS2 changed to CHA2DS2VASC; DOAC added; in patients with factor levels 1% to 20%, the threshold for the CHA2DS2VASC is raised to 4 and the option of catheter ablation is added.

Recommendation for anticoagulant therapy in hemophilia patients with atrial fibrillation. Compared with our previous flowchart,2 notice the following adaptations: baseline FVIII/FIX changed from 30% to 20%; CHADS2 changed to CHA2DS2VASC; DOAC added; in patients with factor levels 1% to 20%, the threshold for the CHA2DS2VASC is raised to 4 and the option of catheter ablation is added.

Third, in the era of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), we now more often consider the lower dose of dabigatran (110 mg twice daily) in patients with FVIII/IX levels >20% because of the superior safety profile of DOACs to that of VKAs, particularly regarding intracerebral bleeding.9 Fourth, in PWH who are below the trough factor level of 20%, we consider the bleeding risk for any form of anticoagulant therapy to be higher and, therefore, we increase the CHA2DS2VASC threshold needed to consider starting this therapy to 4. Fifth, because we believe that VKAs or DOACs are contraindicated in PWH with FVIII/IX levels <20%, the question is whether aspirin should be recommended. The use of low-dose aspirin has been reported in at least 40 PWH with no significant increase in major bleeding episodes.5,7,8,10 It should be carefully noted that all patients with severe hemophilia using aspirin used regular clotting factor prophylaxis. In 1 patient with mild hemophilia, the dual antiplatelet therapy was stopped due to a gastrointestinal bleed; in 1 patient with severe hemophilia, the prophylaxis dose was increased due to easy bruising.8 However, the role for aspirin in the prevention of ischemic stroke in atrial fibrillation has been questioned, leading to the omission of aspirin in most current cardiology guidelines.3 Furthermore, the rates of major bleeding with aspirin do not differ from those with oral anticoagulants in the general population.11 The bleeding risks associated with anticoagulant therapy depends strongly on the a priori bleeding risk. Indeed, 1 of the strongest predictors for major bleeding during anticoagulant therapy for atrial fibrillation is a prior history of bleeding, as demonstrated in the frame of the HAS-BLED (hypertension, abnormal renal and/or liver function, stroke, bleeding, labile international normalized ratios, elderly, drugs or alcohol) and the recently published ORBIT (older age [>74 years], reduced hemoglobin, bleeding history, insufficient kidney function, treatment with antiplatelets) and ABC (age, biomarkers, clinical history) bleeding scores.12,13 Therefore, regardless of other risk factors for bleeding such as age, cancer, and renal insufficiency, we consider hemophilia patients to be at high risk for bleeding. In the setting of moderate and mild hemophilia, it is as yet unknown whether the bleeding risks of aspirin vs oral anticoagulants are comparable. Therefore, we still tend to use low-dose aspirin in PWH with FVIII/FIX levels 1 to 20 and a CHA2DS2VASC score of ≥4. This is in line with the level A recommendation from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) 2012 guideline for patients with a HAS-BLED score ≥3.3 Furthermore, given the uncertainties of the bleeding risks as depicted, in some patients, strategies meant to avoid the need of long-term anticoagulant therapy altogether should be considered and implemented. The first consideration is catheter ablation (pulmonary vein isolation), with short-term substitution of clotting factor concentrates during periprocedural treatment with VKAs or DOACs. Recently, it has been demonstrated that in patients at high risk for stroke (CHA2DS2VASC score ≥2), discontinuation of oral anticoagulants 3 months after successful ablation was comparable with prolonged duration of anticoagulants in terms of prevention of long-term thromboembolic complications. In contrast, in patients at high risk for bleeding (HAS-BLED ≥3), prolonged anticoagulation resulted in more serious bleeding.14 Second, percutaneous closure of the left atrial appendage (LAA) is another possibility for these patients with a high bleeding risk,15 in whom short-term substitution of clotting factor concentrates during periprocedural treatment with VKAs is indicated during the endothelialization of the LAA occluder.

Finally, it has been demonstrated that the ETP in patients with severe and moderate hemophilia is equal to that of patients on VKAs, whereas mild hemophilia patients are in between controls and VKAs.16,17 This is in line with our suggestion to withhold anticoagulants in severe hemophilia without prophylaxis but we tend to use them in the very mild cases. As there is considerable heterogeneity within mild hemophilia patients, individualized thrombin generation guided therapy might be the future. However, there is currently no data to support the use of thrombin generation in predicting the bleeding risk in PWH using anticoagulation.

Acute coronary syndromes and stenting in hemophilia

Many expert panels, including past recommendations from ourselves2 and the recent How I Treat article from Martin and Key,1 recommend bare metal stents (BMSs) over drug-eluting stents (DESs) due to the shorter period of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) (1 month compared with 1 year). This approach was valid for the first-generation DESs, which carried a higher risk of stent thrombosis. In contrast, the second-generation DESs show better clinical outcomes than BMSs in terms of thrombosis, restenosis, death, and myocardial infarction (MI).18 Current guidelines advocate 1 month of DAPT in BMSs and 6 months of DAPT in DESs for patients with low bleeding risk,19 after stenting in stable coronary artery disease. In the recent randomized Zeus trial,20 a second-generation DES with a 1-month period of DAPT was compared with a BMS in 1606 DES candidates, of whom more than half were considered to be at high risk of bleeding. The clinical outcomes were clearly in favor of DESs with shorter DAPT: there was a reduction of MI, revascularization, and of the composite outcome of any death or nonfatal MI, as well as of cardiovascular death and nonfatal MI. Moreover, there was no difference in the rate of any grade of bleeding. Because nowadays second-generation DESs are widely available, we strongly suggest their use over BMSs also in PWH, followed by a 1-month period of DAPT. Finally, drug-eluting balloons to avoid stenting21 may be considered in the treatment of coronary disease in these patients with a high bleeding risk.

All in all, treating hemophilia patients with anticoagulation is a complex matter, especially due to the lack of clinical data on larger cohorts. Our suggestions are meant to be a clinical guidance for individual consideration. There is an urgent need for data on safety and efficacy of anticoagulation in PWH that would be obtained by the implementation of registries in the context of specialized hemophilia centers.

Authorship

Contribution: R.E.G.S., J.F.v.d.H., E.P.M.-B., and P.M.M. all wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Roger E. G. Schutgens, Van Creveldkliniek, University Medical Center Utrecht, Heidelberglaan 100, 3584CX Utrecht, The Netherlands; e-mail: r.schutgens@umcutrecht.nl.