Key Points

IFN-γ alone leads to aplastic anemia by disrupting the generation of common myeloid progenitors and lineage differentiation.

The inhibitory effect of IFN-γ on hematopoiesis is intrinsic to hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells.

Abstract

Aplastic anemia (AA) is characterized by hypocellular marrow and peripheral pancytopenia. Because interferon gamma (IFN-γ) can be detected in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of AA patients, it has been hypothesized that autoreactive T lymphocytes may be involved in destroying the hematopoietic stem cells. We have observed AA-like symptoms in our IFN-γ adenylate-uridylate–rich element (ARE)–deleted (del) mice, which constitutively express a low level of IFN-γ under normal physiologic conditions. Because no T-cell autoimmunity was observed, we hypothesized that IFN-γ may be directly involved in the pathophysiology of AA. In these mice, we did not detect infiltration of T cells in bone marrow (BM), and the existing T cells seemed to be hyporesponsive. We observed inhibition in myeloid progenitor differentiation despite an increase in serum levels of cytokines involved in hematopoietic differentiation and maturation. Furthermore, there was a disruption in erythropoiesis and B-cell differentiation. The same phenomena were also observed in wild-type recipients of IFN-γ ARE-del BM. The data suggest that AA occurs when IFN-γ inhibits the generation of myeloid progenitors and prevents lineage differentiation, as opposed to infiltration of activated T cells. These results may be useful in improving treatment as well as maintaining a disease-free status.

Introduction

Aplastic anemia (AA) is a life-threatening disease characterized by hypocellular marrow and pancytopenia as a result of reduction in hematopoietic progenitor and stem cells (HSPCs). Usually, AA is a result of HSPC destruction targeted by autoreactive cytotoxic T cells. Oligoclonal expansion of T-cell receptor (TCR) Vβ subfamilies and interferon gamma (IFN-γ) can be detected in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of these patients. Although many factors have been implicated in autoreactive T-cell activation, no conclusive causes have been identified. In <10% of AA patients, the disease mechanism has a genetic basis with inherited mutations or polymorphism in genes that repair or protect telomeres. These defects result in short telomeres, which dramatically decrease the proliferative capacity of HSPCs.1,2 Currently, the most effective therapy for AA is hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; however, <30% of patients have a suitable HLA-matched donor.3 Because most AA patients are immune mediated, when a histocompatible donor is unavailable, patients undergo immunosuppressive therapy (IST) consisting of antithymocyte globulin/antilymphocyte globulin with cyclosporine. This treatment results in a significant reduction in the number of circulating T cells followed by disease resolution.4,5

Several recent studies have determined that a high percentage of AA patients show a T→A single nucleotide polymorphism at position +874 of intron 1 in the IFN-γ gene compared with normal controls, resulting in higher levels of IFN-γ expression.6-8 Thus, it was suggested that higher IFN-γ expression levels may correlate with a greater risk of developing AA. Additional evidence suggested that IFN-γ +874 TT, a high IFN-γ expression genotype is a predictor of a better response to IST in AA patients.9 Moreover, Dufour et al10 found that AA patients who responded to IST had a significantly higher frequency of CD3+/IFN-γ+ cells than normal controls (561 vs 50 cells per milliliter), which implied that IST may not fully clear IFN-γ from patients. Blockade of IFN-γ in a culture with marrow from IST responders showed an increase in burst-forming unit erythroid. Therefore, it was proposed that patients with acquired AA would benefit from IST combined with IFN-γ neutralization treatment. These studies suggest that IFN-γ contributes significantly to AA pathology and may also be a therapeutic target. Although several studies have explored this question, their models used IFN-γ that was either added exogenously or expressed by non-IFN-γ–expressing cells.11,12 Therefore, our laboratory developed an animal model whereby IFN-γ is expressed by natural killer (NK) and T cells, which normally express IFN-γ and will allow us to better investigate the mechanisms of how IFN-γ contributes to the development of AA. Our BALB/c mouse model contains a 162-nucleotide targeted substitution in the 3′ untranslated region of the IFN-γ gene that eliminates the adenylate-uridylate–rich element (ARE) of the IFN-γ messenger RNA (mRNA) (mice are designated as ARE-del). The ARE of the IFN-γ mRNA mediates the destabilization of the mRNA.13 Thus, the deletion increases the half-life of IFN-γ mRNA and results in constant expression of IFN-γ. Although we did not observe an active T-cell response in the ARE-del mice, these animals exhibited an AA-like phenotype, including hypocellular marrow and pancytopenia. Therefore, we believe that IFN-γ plays a role in the AA pathology in these mice. In this study, we found that AA in ARE-del mice was the result of constant exposure to low levels of IFN-γ by inhibiting the differentiation of multipotent progenitors (MPPs) to myeloid progenitors, as well as the differentiation of red blood cells (RBCs) and B cells.

Methods

IFN-γ ARE-del mice

The 162-neucleotide ARE sequence was replaced by electroporation of the IFN-γ/Neo cassette into the DY380 bacterial strain with a bacterial antigen complex containing the IFN-γ gene. A 9.9-kb sequence containing the recombined locus was retrieved from the bacterial antigen complex and cloned into a pBR322 plasmid. The modified pBR322 plasmid was introduced into an embryonic stem cell line by gene targeting to generate chimeric mice. The Neo cassette removal was accomplished by crossing the chimeras with β-actin Cre-transgenic mice. Animals used in this study were 3 to 8 weeks old. Animal care was provided in accordance with the procedures outlined in the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Flow cytometry

The following antibodies were used in this study: anti-NKp46, CD3, IFN-γ, Sca-1, c-Kit, interleukin (IL)-7Rα, CD16/32, CD71, CD19, and B220 (eBioscience), CD34 and CD135 (BD Biosciences PharMingen), and CD43, CD44, Gr-1, CD25, Ter119, and Mac-1 (BioLegend). For NK cell, T-cell, and lineage analysis, whole bone marrow (BM) cells were used. For HSPCs, immunophenotype analysis lineage-negative cells were selected by using the Lineage Cell Depletion Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) before antibody staining. Dead cells were excluded by using Fixable Viability Dye eFluor 660 (eBioscience). An LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) was used for acquiring data, and results were analyzed by using FlowJo software (TreeStar).

BM transplantation

For BM transplantation, recipient wild-type (WT) or ARE-del mice received 400 rad of radiation and were injected with 5 × 106 BM cells from WT mice. For the chimera model, recipient WT Balb/c mice were treated with trimethoprim-sulfomethoxazole in the drinking water 1 week before receiving 900 rad of radiation and were injected with 106 BM cells from either WT or ARE-del mice. Phenotypes were examined 8 weeks after BM reconstitution.

IFN-γ–neutralizing antibody treatment

WT and ARE-del mice were injected intraperitoneally with 200 μg of IFN-γ–neutralizing antibody (XMG-6, generously provided by Dr Giorgio Trinchieri) or control antibody (GL113) in 100 μL phosphate-buffered saline once per week for 8 weeks. Animals were retro-orbitally bled once every 2 weeks for complete blood count analysis. BM cell immunophenotypes were examined at the end of the treatment period.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed unpaired Student t test. Differences were considered significant if P < .05. All the statistical analyses were performed by using the GraphPad Prism statistical package.

Results

ARE-del mice exhibit an AA phenotype resembling human disease

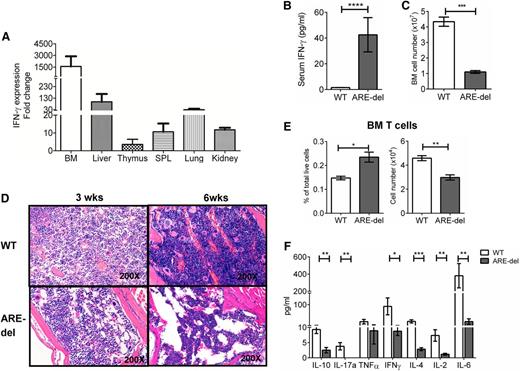

Because the absence of the ARE region stabilizes IFN-γ mRNA, we were able to detect increased IFN-γ mRNA expression in BM, liver, thymus, spleen, lungs, and kidneys (Figure 1A). Under normal physiological conditions, we detected measureable IFN-γ in the serum at ∼40 pg/mL (Figure 1B). Although measurable, IFN-γ serum levels less than 50 pg/mL are considered low in human serum.14 Indeed, ARE-del mice have several phenotypes consistent with human AA. The hypocellular marrow in severe AA is defined as ≤50% of the BM cellularity of healthy individuals.15 In ARE-del mice, total BM cellularity was ∼25% that of the WT mice (Figure 1C). Histopathologic examination of ARE-del BM confirmed that cellularity was significantly decreased at 3 weeks of age with a marked decrease in megakaryocytes. BM cellularity was further decreased with a loss of myeloid cells at week 6 (Figure 1D). As a consequence of the BM hypocellularity, ARE-del mice exhibited another hallmark of AA, peripheral blood pancytopenia with low white blood cell (WBC), RBC, and platelets counts (Table 1). On the basis of these observations, we used this mouse model to determine how a low level of IFN-γ contributes to AA pathology.

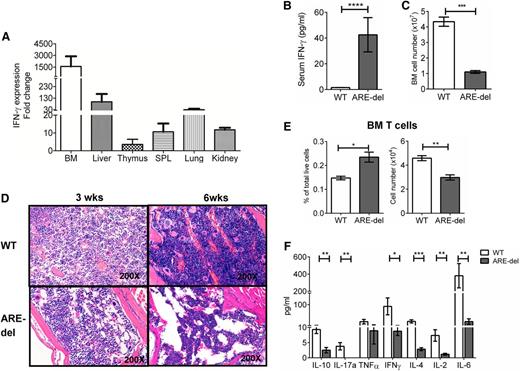

T cells are not the cause of the AA-like phenotype in ARE-del mice. (A) Total RNA was extracted from tissues. Equal amounts of RNA were reverse transcribed into mRNA. IFN-γ mRNA levels were detected by using real-time polymerase chain reaction. Data were normalized against glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase mRNA levels and calculated relative to IFN-γ expression levels in WT tissue set to 1 (n = 3). (B) Serum from animals was analyzed by using a cytometric bead array to determine IFN-γ levels (n = 7). (C) Single-cell suspensions of BM cells were prepared and counted, and total cell numbers are shown (n = 7). (D) Sternums from 6 WT and 6 ARE-del mice were fixed and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Depicted here are representative photographs from 1 set of animals. (E) Seven-color flow cytometry analyses were performed on total BM cells. T cells were gated on the live NKp46–CD11b–B220–Gr1–CD3+ population. The bar graphs show both the total cell number and percentage of live cells (n = 4). (F) T cells were selected from BM. The function of T cells was determined by the intensity of cytokine responses against TCR agonists (anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibodies). Cytokine levels in the medium were measured 6 hours after stimulation by using a cytometric bead array. The bar graphs displays the concentration of each cytokine measured (n = 4). All experiments were performed at least 3 times. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001. SPL, spleen.

T cells are not the cause of the AA-like phenotype in ARE-del mice. (A) Total RNA was extracted from tissues. Equal amounts of RNA were reverse transcribed into mRNA. IFN-γ mRNA levels were detected by using real-time polymerase chain reaction. Data were normalized against glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase mRNA levels and calculated relative to IFN-γ expression levels in WT tissue set to 1 (n = 3). (B) Serum from animals was analyzed by using a cytometric bead array to determine IFN-γ levels (n = 7). (C) Single-cell suspensions of BM cells were prepared and counted, and total cell numbers are shown (n = 7). (D) Sternums from 6 WT and 6 ARE-del mice were fixed and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Depicted here are representative photographs from 1 set of animals. (E) Seven-color flow cytometry analyses were performed on total BM cells. T cells were gated on the live NKp46–CD11b–B220–Gr1–CD3+ population. The bar graphs show both the total cell number and percentage of live cells (n = 4). (F) T cells were selected from BM. The function of T cells was determined by the intensity of cytokine responses against TCR agonists (anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibodies). Cytokine levels in the medium were measured 6 hours after stimulation by using a cytometric bead array. The bar graphs displays the concentration of each cytokine measured (n = 4). All experiments were performed at least 3 times. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001. SPL, spleen.

AA phenotype in ARE-del mice is not caused by activated T cells in the BM

To rule out T-cell–mediated destruction of HSPCs, we measured the levels of T-cell infiltration into the BM. The slight increase in the percentage of T cells (∼0.1%) observed in ARE-del BM was a result of low BM cell number, since the absolute T-cell number was significantly lower (Figure 1E). To evaluate the function of BM T cells, we measured cytokine production after stimulating with TCR agonists (anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibodies). The cytokine levels expressed by ARE-del BM T cells after TCR stimulation were significantly lower than in WT mice, except tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (Figure 1F). We also observed the same hyporesponsiveness in ARE-del mice spleen and lymph node T cells after a mixed lymphocyte reaction (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site). Because an abnormal T-cell repertoire has been reported in AA patients, we characterized the ARE-del BM T-cell repertoire by flow cytometric methods using antibodies that detect different TCR Vβ chains.16-18 Abnormal expansions of Vβ-expressing T cells were defined as values greater than the mean obtained from WT animals plus 2 × standard deviation as previously described.19 Although we observed a slight expansion in 4 Vβ subfamilies in CD4 T cells and 2 Vβ subfamilies in CD8 T cells in ARE-del BM, both the percentage of expansion and the expansion ratio (CD4: 27%, CD8: 17%) in ARE-del mice are much lower compared with that previously reported in AA patients (expansion ratio, 40% to 80%) (supplemental Figure 2).17,19 In addition, histopathological examination of the spleen, thymus, and lymph nodes revealed structural damage and apparent atrophy (supplemental Figure 3), a characteristic reported in congenital AA animal models, which implies that ARE-del mice are severely immunodeficient.20 To summarize, the absence of T-cell infiltration in the BM, nonresponsive BM T cells, no abnormal BM T-cell expansion, and general immunodeficiency indicate that T cells are unlikely the cause of AA in ARE-del mice.

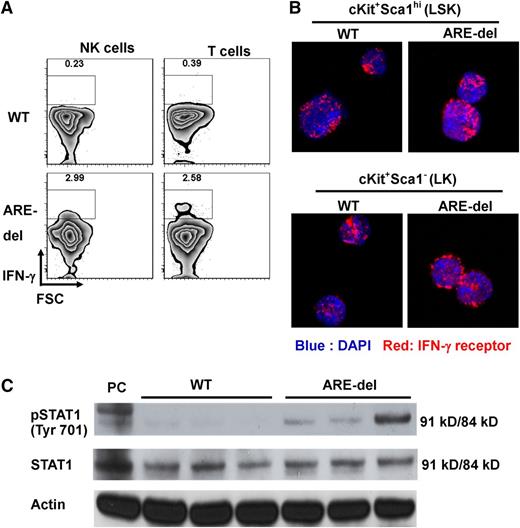

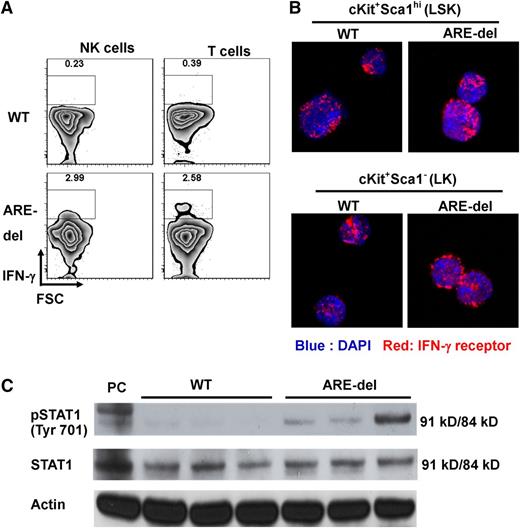

IFN-γ signaling is detected in ARE-del BM cells

To test the hypothesis that IFN-γ was responsible for the AA phenotype in ARE-del mice, we first identified the source of IFN-γ in ARE-del BM. We detected IFN-γ expression in NK and T cells without additional stimulation (Figure 2A), indicating that IFN-γ is present in the BM microenvironment under basal conditions. We were not able to detect IFN-γ expression from lineage-negative cells, which are progenitor-enriched cells, B cells, and myeloid cells in BM (supplemental Figure 4). IFN-γ affects cells by ligand-receptor interaction-triggered JAK/STAT signaling. We found IFN-γ receptor expressed on all lin−cKit+Sca1hi (LSK) and lin−cKit+Sca1− (LK) cells by using confocal microscopy (Figure 2B). This result suggests that HSPCs could be direct targets of IFN-γ. To determine whether BM cells could respond to IFN-γ, we evaluated STAT1 phosphorylation in unstimulated BM cells from both WT and ARE-del mice and could detect STAT1 phosphorylation only in ARE-del BM cells (Figure 2C). These data support the hypothesis that IFN-γ in ARE-del BM induces JAK/STAT signaling in HSPCs and contributes to BM failure.

IFN-γ and IFN-γ signaling are detected in ARE-del BM. (A) T cells were gated on the live NKp46–CD11b–B220–Gr1–CD3+ population, and NK cells were gated on the live NKp46+CD11b–B220–Gr1–CD3– population. IFN-γ expression by BM NK and T cells was detected by using intracellular cytokine staining. Dot plots are representative of 1 set of 4 experiments. (B) Total BM cells from WT and ARE-del mice were sorted into LSK (LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, and MPPs) and LK (CMPs, GMPs, and MEPs) populations and centrifuged onto slides. The cells were then stained with antibody against IFN-γ receptor. The expression of IFN-γ receptor was captured with a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope. (C) Total protein was extracted from untreated WT and ARE-del BM. Proteins were detected by western blotting with antibody against phosphorylated Stat1 (pSTAT1) tyrosine 701 residue. Stat1 and actin were used as loading controls. Positive control (PC) is protein extracted from WT splenocytes stimulated with IFN-γ for 15 minutes. DAPI, 4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole. FSC, forward side scatter.

IFN-γ and IFN-γ signaling are detected in ARE-del BM. (A) T cells were gated on the live NKp46–CD11b–B220–Gr1–CD3+ population, and NK cells were gated on the live NKp46+CD11b–B220–Gr1–CD3– population. IFN-γ expression by BM NK and T cells was detected by using intracellular cytokine staining. Dot plots are representative of 1 set of 4 experiments. (B) Total BM cells from WT and ARE-del mice were sorted into LSK (LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, and MPPs) and LK (CMPs, GMPs, and MEPs) populations and centrifuged onto slides. The cells were then stained with antibody against IFN-γ receptor. The expression of IFN-γ receptor was captured with a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope. (C) Total protein was extracted from untreated WT and ARE-del BM. Proteins were detected by western blotting with antibody against phosphorylated Stat1 (pSTAT1) tyrosine 701 residue. Stat1 and actin were used as loading controls. Positive control (PC) is protein extracted from WT splenocytes stimulated with IFN-γ for 15 minutes. DAPI, 4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole. FSC, forward side scatter.

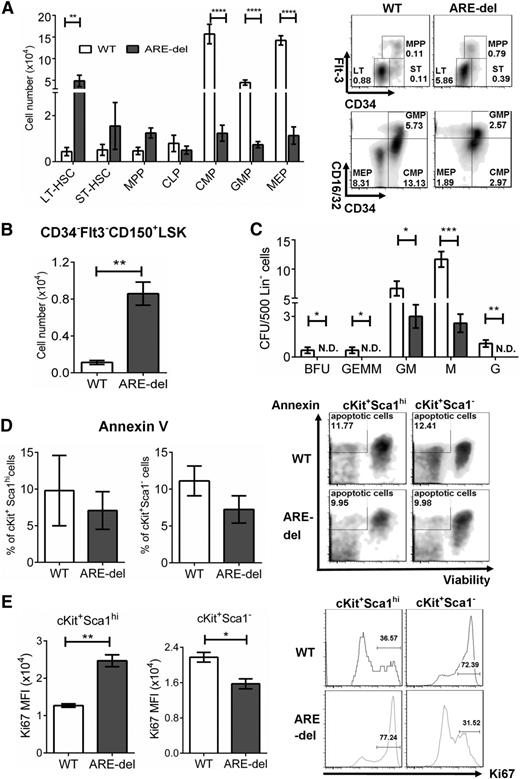

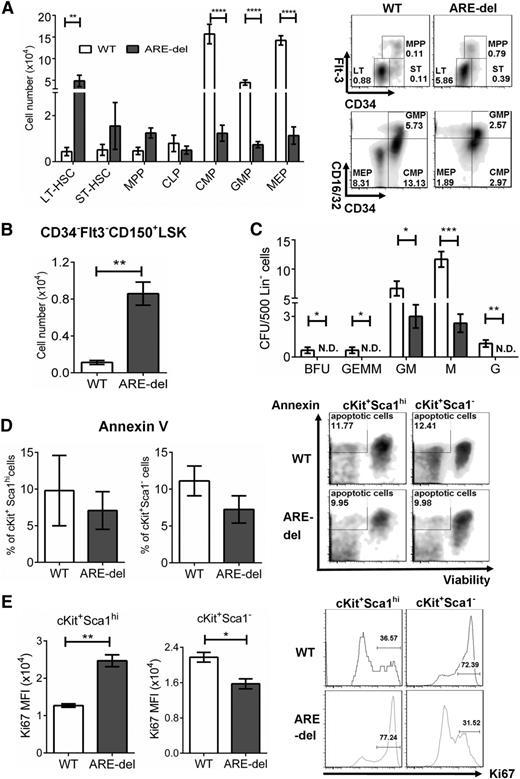

IFN-γ disrupts the differentiation of MPPs to myeloid progenitors

To determine the impact of IFN-γ on hematopoiesis, we compared the total number of immunophenotypic HSPCs present in WT and ARE-del BM. We saw a dramatic decrease in the cell numbers of common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) (fourfold), granulocyte/monocyte progenitors (GMPs) (fourfold), and megakaryocyte/erythrocyte progenitors (MEPs) (eightfold) in ARE-del mice. There were no significant differences in the cell numbers of short-term hematopoietic stem cells (ST-HSCs), MPPs, and common lymphoid progenitors (Figure 3A). Because IFN-γ has been known to suppress hematopoiesis,11 we were surprised to see an increase in long-term HSCs (LT-HSCs) (2.5-fold). Thus, we confirmed the increase of LT-HSCs by using the SLAM marker, CD150, which is co-expressed on HSCs with self-renewal capability.21 We observed a fourfold increase in the cell number of lin–cKit+Sca1hiCD34–Flt3–CD150+ (Figure 3B). To confirm that the decrease in CMPs, GMPs, and MEPs is correlated to a decrease in function, we examined the ability of these progenitors to form colonies. We found that the total number of burst-forming unit erythroid, colony-forming unit (CFU)-granulocyte, -erythrocyte, -macrophage, and -megakaryocyte (CFU-GEMM), CFU-granulocyte, -macrophage (CFU-GM), CFU-megakaryocyte (CFU-M), and CFU-granulocyte (CFU-G) progenitors were significantly lower in ARE-del mice, demonstrating that these progenitors are not only decreased in number but are also decreased in function (Figure 3C). These data indicate that the generation of CMPs, GMPs, and MEPs is significantly inhibited in ARE-del mice. The block in myeloid progenitor production could have a profound impact on the generation of blood cells, and thus contribute to the pathology of pancytopenia in AA.

Constant exposure to IFN-γ alters the composition of HSPCs. (A) HSPC composition was gated on lineage-negative BM cells by using flow cytometry, LT-HSCs (lin–cKit+Sca1hiCD34–Flt3–), ST-HSCs (lin–cKit+Sca1hiCD34+Flt3–), MPPs (lin–cKit+Sca1hiCD34+Flt3+), common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs; lin–cKitintSca1intIL-7R+), CMPs (lin−cKit+Sca1–CD34+CD16/32int), GMPs (lin−cKit+Sca1−CD34+CD16/32hi), and MEPs (lin−cKit+Sca1–CD34–CD16/32lo) (n = 7). The bar graph shows the total cell number of each cell type. Density plots are representative of HSPC gating from 1 set of 4 experiments. (B) The lin–cKit+Sca1hiCD34–Flt3+CD150+ population was used to confirm HSC composition. The bar graph shows the total cell number (n = 5). (C) The function of CMPs, GMPs, and MEPs was analyzed by using a colony-forming assay. Lineage-negative BM cells were plated in triplicate, and the colonies were counted after culture for 7 days. The numbers of each colony are shown. (D) Apoptosis in HSPC was assessed by using Annexin V staining and Fixable Viability Dye eFluor 660. The Annexin V–positive/Viability Dye–negative population represents apoptotic cells. The bar graph shows the percentage of apoptotic cells in the LSK or LK population (n = 4). Density plots are representative of 1 set of 4 experiments. (E) The proliferation of HSPCs was determined by the expression level of Ki-67. The bar graph shows the medium fluorescent intensity (MFI) of Ki-67 cells in the LSK or LK population. Histograms are representative of 1 set of 4 experiments. All experiments were performed at least 3 times. Similar results were obtained from 3 different experiments. Results are expressed as mean ± SD. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001. N.D., not detectable.

Constant exposure to IFN-γ alters the composition of HSPCs. (A) HSPC composition was gated on lineage-negative BM cells by using flow cytometry, LT-HSCs (lin–cKit+Sca1hiCD34–Flt3–), ST-HSCs (lin–cKit+Sca1hiCD34+Flt3–), MPPs (lin–cKit+Sca1hiCD34+Flt3+), common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs; lin–cKitintSca1intIL-7R+), CMPs (lin−cKit+Sca1–CD34+CD16/32int), GMPs (lin−cKit+Sca1−CD34+CD16/32hi), and MEPs (lin−cKit+Sca1–CD34–CD16/32lo) (n = 7). The bar graph shows the total cell number of each cell type. Density plots are representative of HSPC gating from 1 set of 4 experiments. (B) The lin–cKit+Sca1hiCD34–Flt3+CD150+ population was used to confirm HSC composition. The bar graph shows the total cell number (n = 5). (C) The function of CMPs, GMPs, and MEPs was analyzed by using a colony-forming assay. Lineage-negative BM cells were plated in triplicate, and the colonies were counted after culture for 7 days. The numbers of each colony are shown. (D) Apoptosis in HSPC was assessed by using Annexin V staining and Fixable Viability Dye eFluor 660. The Annexin V–positive/Viability Dye–negative population represents apoptotic cells. The bar graph shows the percentage of apoptotic cells in the LSK or LK population (n = 4). Density plots are representative of 1 set of 4 experiments. (E) The proliferation of HSPCs was determined by the expression level of Ki-67. The bar graph shows the medium fluorescent intensity (MFI) of Ki-67 cells in the LSK or LK population. Histograms are representative of 1 set of 4 experiments. All experiments were performed at least 3 times. Similar results were obtained from 3 different experiments. Results are expressed as mean ± SD. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001. N.D., not detectable.

IFN-γ inhibits LK population proliferation

IFN-γ induces PD-L1 expression on T cells, NK cells, macrophages, myeloid cells, B cells, epithelial cells, and endothelial cells, and PD-L1 binding to its receptor PD-1 induces apoptosis.22 Because this mechanism could account for the loss in CMPs, GMPs, and MEPs in ARE-del mice, we evaluated apoptosis in ARE-del BM cells. We did not detect a significant increase in apoptosis in either LSK or LK cells in ARE-del BM compared with WT (Figure 3D). These results were confirmed when we evaluated apoptotic cells by using the terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling assay (supplemental Figure 5A). Because IFN-γ has been shown to inhibit HSPC proliferation in vitro, this inhibition may be the result of the decrease in HSPCs. We evaluated HSPC proliferation by measuring Ki-67 and found that Ki-67 expression level in the LSK population of ARE-del mice was twofold higher compared with WT, whereas in the LK population, the level was 30% lower (Figure 3E). The inhibition of LK proliferation by IFN-γ was also observed in vitro when we evaluated the proliferation of CMPs, GMPs, and MEPs cultured with IFN-γ. CMPs cultured with IFN-γ had a significantly lower proliferation rate compared with those cultured with medium only. Although the trend was not statistically significant, we observed a trend toward inhibition of GMP proliferation by IFN-γ. Interestingly, the inhibitory effect of IFN-γ on MEPs was observed only in ARE-del mice (supplemental Figure 5B). Together, these data suggest that the hypocellularity in ARE-del mice BM was a result of disruption in CMP generation and a reduction in the proliferative potential of the LK population.

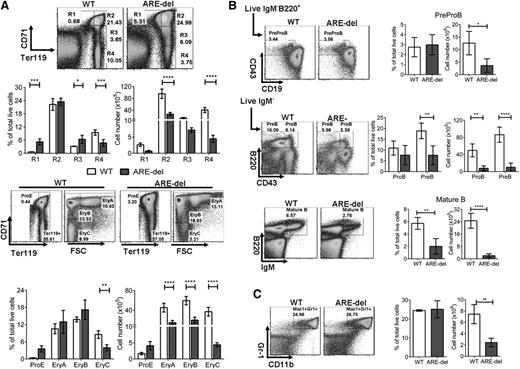

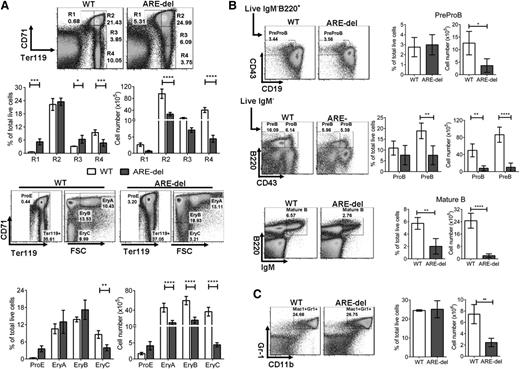

IFN-γ disrupts multilineage differentiation

To determine whether cell lineages were affected in ARE-del mice, we examined the development of erythroid, myeloid, and lymphoid cells. We first examined BM cells with anti-CD71 and Ter119 antibodies to identify different stages of erythroid differentiation.23 There was a twofold increase in the percentage of immature erythrocytes, proerythroblasts, and polychromatophilic erythroblasts and a twofold decrease in the mature erythrocytes and orthochromatophilic erythroblasts in ARE-del BM compare with WT (Figure 4A). We confirmed these results by using cell size, CD71, and Ter119.24 Specifically, we observed an increase, although not significant, in the percentage of the immature erythrocytes ProE, EryA, and EryB and a twofold decrease in the mature erythrocytes EryC in ARE-del BM (Figure 4A). When we calculated the absolute cell number, we found that there was a ninefold decrease in the total output of erythroid cells in ARE-del mice. These results suggest that immature erythrocytes in ARE-del mice fail to differentiate into mature cells, resulting in a severe decrease in the cell output that would ultimately lead to anemia.

Constant exposure to IFN-γ interrupts RBC and B-cell differentiations. Total BM cells were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies for lineage differentiation analysis. (A) Different developmental stages of RBCs were gated according to the expression levels of Ter119 and CD71 (R1: proerythroblasts, Ter119medCD71high; R2: early basophilic erythroblasts, Ter119highCD71high; R3: polychromatophilic erythroblasts, Ter119highCD71med; R4: orthochromatophilic erythroblasts, Ter119highCD71lo). ProE cells are gated on the CD71hi and Ter119low population. Ter119hi population was then further defined on the basis of the expression levels of CD71 and cell size into EryA (CD71highFSChigh), EryB (CD71highFSClow), and EryC (CD71lowFSClow). (B) Live IgM–B220+ population in BM was measured by using CD43 and CD19 to define PreProB (CD43+CD19–). PreB (B200+CD43–) and ProB (B220+CD43+) populations were gated on live IgM– population in BM using CD43 and B220. Mature B cells were gated on a live IgM+B220+ population. (C) Myeloid cells in BM were gated on the Mac1+CD11b+ population. Dot plots are representative of 1 set of multiple experiments. Bar graphs show the percentage of total live BM cells and the total cell numbers of each cell type (n = 5). Similar results were obtained from 4 different experiments. Results are expressed as mean ± SD. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001.

Constant exposure to IFN-γ interrupts RBC and B-cell differentiations. Total BM cells were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies for lineage differentiation analysis. (A) Different developmental stages of RBCs were gated according to the expression levels of Ter119 and CD71 (R1: proerythroblasts, Ter119medCD71high; R2: early basophilic erythroblasts, Ter119highCD71high; R3: polychromatophilic erythroblasts, Ter119highCD71med; R4: orthochromatophilic erythroblasts, Ter119highCD71lo). ProE cells are gated on the CD71hi and Ter119low population. Ter119hi population was then further defined on the basis of the expression levels of CD71 and cell size into EryA (CD71highFSChigh), EryB (CD71highFSClow), and EryC (CD71lowFSClow). (B) Live IgM–B220+ population in BM was measured by using CD43 and CD19 to define PreProB (CD43+CD19–). PreB (B200+CD43–) and ProB (B220+CD43+) populations were gated on live IgM– population in BM using CD43 and B220. Mature B cells were gated on a live IgM+B220+ population. (C) Myeloid cells in BM were gated on the Mac1+CD11b+ population. Dot plots are representative of 1 set of multiple experiments. Bar graphs show the percentage of total live BM cells and the total cell numbers of each cell type (n = 5). Similar results were obtained from 4 different experiments. Results are expressed as mean ± SD. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001.

When investigating B-cell lineage differentiation, we found there was no difference in the percentage of PrePro B cells (the immature early B cells arising from common lymphoid progenitors) and ProB cells (the early B cells derived from PreProB cells). However, we found a twofold reduction in the percentage of PreB (the early B cells differentiated from ProB cells) (Figure 4B). This result implies a disruption in early B-cell differentiation. The decrease in the percentage of PreB cells in ARE-del mice has a profound impact on the output of early B cells and the generation of mature B cells. The absolute cell numbers of PreB and mature B cells were reduced approximately eightfold (Figure 4B). In contrast, we did not observe any effect on myeloid differentiation, although ARE-del mice had a threefold reduction in the total number of myeloid cells in BM (Figure 4C). To summarize, IFN-γ impairs multilineage differentiation and severely reduces the output of mature erythrocytes, B cells, and myeloid cells, which would account for hypocellular marrow and pancytopenia.

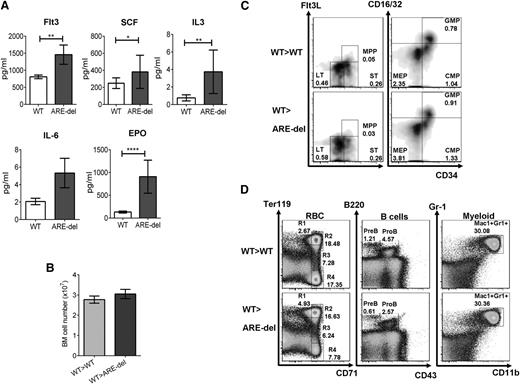

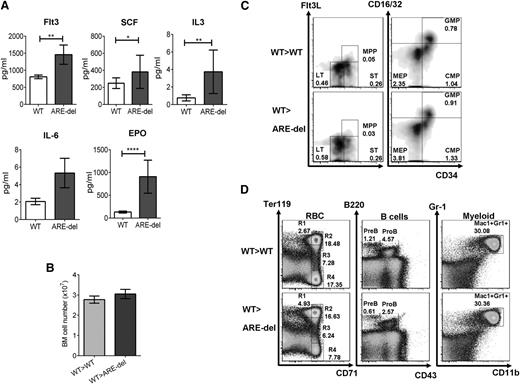

AA phenotype in ARE-del mice is not a result of a cell nonautonomous effect of IFN-γ on the BM microenvironment

Next, we determined whether the BM failure observed in ARE-del mice was a result of a cell nonautonomous effect of IFN-γ on the BM microenvironment, which could impair the ability of niche cells to support normal hematopoiesis. First, we evaluated the levels of serum hematopoietic cytokines produced by stromal cells. Serum levels of Flt3 ligand (Flt3L) (twofold), stem cell factor (SCF) (1.5 fold), IL-3 (threefold), and erythropoietin (EPO) (sevenfold) were all significantly higher in ARE-del mice (Figure 5A). IL-6 levels were also higher in ARE-del mice, although not significantly higher. Granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor was not detectable in the serum of ARE-del and WT mice, which demonstrates that BM niche cells in ARE-del mice were capable of secreting cytokines required to maintain functional hematopoiesis. Furthermore, it suggests that AA phenotype in ARE-del mice was not a result of a deficiency in hematopoietic cytokines.

The AA phenotype in ARE-del mice is not a result of a cell nonautonomous effect of IFN-γ on the BM microenvironment. (A) The function of stromal cells in ARE-del mice was determined by the serum levels of Flt3L, SCF, IL-3, IL-6, and EPO. The concentrations of cytokines were measured by using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and shown in bar graphs (n = 6). BM phenotypes in WT>WT and ARE-del >WT mice were analyzed 8 weeks after reconstitution. (B) The bar graph shows BM cell numbers of chimeric mice (n = 6). (C) HSPC composition was analyzed on lineage-negative BM cells from WT>WT and WT>ARE-del mice by using flow cytometry. Density plots are representative of HSPC gating from 1 set of 3 experiments. (D) Total BM cells from WT>WT and WT>ARE-del mice were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies for lineage differentiation analysis. Dot plots are representative of 1 set of 3 experiments. Similar results were obtained from 3 different experiments. Results are expressed as mean ± SD. *P < .05; **P < .01; ****P < .0001.

The AA phenotype in ARE-del mice is not a result of a cell nonautonomous effect of IFN-γ on the BM microenvironment. (A) The function of stromal cells in ARE-del mice was determined by the serum levels of Flt3L, SCF, IL-3, IL-6, and EPO. The concentrations of cytokines were measured by using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and shown in bar graphs (n = 6). BM phenotypes in WT>WT and ARE-del >WT mice were analyzed 8 weeks after reconstitution. (B) The bar graph shows BM cell numbers of chimeric mice (n = 6). (C) HSPC composition was analyzed on lineage-negative BM cells from WT>WT and WT>ARE-del mice by using flow cytometry. Density plots are representative of HSPC gating from 1 set of 3 experiments. (D) Total BM cells from WT>WT and WT>ARE-del mice were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies for lineage differentiation analysis. Dot plots are representative of 1 set of 3 experiments. Similar results were obtained from 3 different experiments. Results are expressed as mean ± SD. *P < .05; **P < .01; ****P < .0001.

We then investigated whether the BM niche in ARE-del mice is able to support hematopoiesis by using a BM chimera model. We transferred BM cells from healthy WT mice into ARE-del mice and examined their phenotype 8 weeks after reconstitution. Similar to the human disease, BM transplantation reversed the AA phenotype in WT BM-reconstituted ARE-del (WT>ARE-del) chimeras. The BM cellularity in WT>ARE-del chimeras was comparable to the WT BM-reconstituted WT (WT>WT) chimeras (Figure 5B). Although WBC, RBC, and platelet counts in WT>ARE-del chimeras were slightly lower than in WT>WT chimeras, they were all within the normal range (Table 2). WT BM transplantation was able to restore the HSPC composition to one more closely resembling that in WT (Figure 5C). Furthermore, WT BM transplantation also resolved the blocks in erythropoiesis and early B-cell differentiation observed in the ARE-del mice (Figure 5D). These data show that the BM niche in ARE-del mice is functional and able to support normal hematopoiesis.

ARE-del BM-reconstituted WT (ARE-del>WT) chimeras exhibit an early AA phenotype 8 weeks after BM reconstitution

The ability of WT BM-restoring normal hematopoietic development in the ARE-del mice indicates that the inhibitory effect of IFN-γ on hematopoiesis may be cell intrinsic. To confirm this hypothesis, we transplanted the ARE-del BM cells into lethally irradiated WT BALB/c mice. We then analyzed the phenotype 8 weeks after BM reconstitution. Complete blood count analysis revealed that ARE-del>WT chimeras had a slight decrease in WBC and RBC counts and severe thrombocytopenia, which, in the human disease, is the first sign of AA followed by anemia and pancytopenia (Table 3).25 In addition, ARE-del>WT chimeras had significantly lower BM cellularity than WT>WT chimeras (Figure 6A). These results show that ARE-del>WT chimeras were in the early stage of disease, which allowed us to investigate T-cell involvement in the initiation of AA. Similar to that observed in ARE-del mice, we observed a slight increase (∼0.2%) in the T-cell percentage of total BM cells in ARE-del>WT chimeras. However, there was no difference in the absolute T-cell number (Figure 6B). When stimulated with TCR agonists, the cytokine responses of ARE-del>WT BM T cells were either lower than or equivalent to those of WT>WT chimeras, except IFN-γ (Figure 6C). These findings demonstrate that ARE-del>WT BM T cells were not activated and were not involved in disease initiation. When we examined the BM progenitors by immunophenotype, we observed HSPC composition in ARE-del>WT BM similar to that in ARE-del BM: high LT-HSC and low CMPs, GMPs, and MEPs (Figure 6D). We observed a block in erythroid development similar to that in ARE-del mice but to a lesser extent (Figure 6E). Together, these data indicate that IFN-γ results in a cell-intrinsic defect in HSPCs that leads to inhibition of hematopoiesis and disruption in erythropoiesis.

ARE-del>WT chimera mice exhibit early signs of BM failure with HSPC composition similar to that of ARE-del mice. BM phenotype of chimeric mice was evaluated 8 weeks after reconstitution. (A) The bar graph shows the total BM cell number from WT>WT and ARE-del>WT (n = 8). (B) T-cell population in BM of chimeric mice was analyzed by using 7-color flow cytometry analyses. T cells were gated on live NKp46–CD11b–B220–Gr1–CD3+ populations. Bar graphs show both the total cell number of T cells and the percentage of live cells (n = 8). (C) The function of T cells in chimeric BM was determined by the intensity of cytokine responses against TCR agonists (anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibodies [Abs]). Cytokine levels in the medium were measured 6 hours after stimulation by using a cytometric bead array. The bar graphs displays the concentration of each cytokine measured (n = 8). (D) HSPC composition in the BM of chimeric mice was analyzed on lineage– BM cells by using flow cytometry. The bar graph shows the total cell number of each cell type (n = 8). (E) Total BM cells from WT>WT and ARE-del>WT mice were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies for lineage differentiation analysis. Dots plots are representative of 1 set of 3 experiments. (F) BM cells from all 4 groups (WT/control, WT/neutralizing, knockout (KO)/control and KO/neutralizing) were analyzed for LSK and LK populations and (G) erythropoiesis. Density and dot plots are representatives of 1 set of 3 experiments. Results are expressed as mean ± SD. *P < .05; **P < .01; ****P < .0001

ARE-del>WT chimera mice exhibit early signs of BM failure with HSPC composition similar to that of ARE-del mice. BM phenotype of chimeric mice was evaluated 8 weeks after reconstitution. (A) The bar graph shows the total BM cell number from WT>WT and ARE-del>WT (n = 8). (B) T-cell population in BM of chimeric mice was analyzed by using 7-color flow cytometry analyses. T cells were gated on live NKp46–CD11b–B220–Gr1–CD3+ populations. Bar graphs show both the total cell number of T cells and the percentage of live cells (n = 8). (C) The function of T cells in chimeric BM was determined by the intensity of cytokine responses against TCR agonists (anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibodies [Abs]). Cytokine levels in the medium were measured 6 hours after stimulation by using a cytometric bead array. The bar graphs displays the concentration of each cytokine measured (n = 8). (D) HSPC composition in the BM of chimeric mice was analyzed on lineage– BM cells by using flow cytometry. The bar graph shows the total cell number of each cell type (n = 8). (E) Total BM cells from WT>WT and ARE-del>WT mice were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies for lineage differentiation analysis. Dots plots are representative of 1 set of 3 experiments. (F) BM cells from all 4 groups (WT/control, WT/neutralizing, knockout (KO)/control and KO/neutralizing) were analyzed for LSK and LK populations and (G) erythropoiesis. Density and dot plots are representatives of 1 set of 3 experiments. Results are expressed as mean ± SD. *P < .05; **P < .01; ****P < .0001

IFN-γ–neutralizing antibody treatment reverses HSPC composition and restores erythropoiesis

To confirm the inhibitory effect of IFN-γ on hematopoiesis in ARE-del mice, we blocked the effect of IFN-γ by treating with IFN-γ–neutralizing antibodies once per week for 8 weeks and then analyzed the phenotype of ARE-del mice. The treatment was performed on 3-week-old ARE-del mice, which exhibited thrombocytopenia but not anemia and were healthy enough to receive injections. Mice were bled once every 2 weeks to monitor the platelet levels. More than 50% of ARE-del mice receiving control antibody died during the treatment period, which resulted in an early termination of treatment at week 6. Nonetheless, we found that treatment with IFN-γ–neutralizing antibodies was able to restore the platelet levels in ARE-del mice close to that in WT mice (supplemental Figure 6). When we examined the HSPC composition at the end of the treatment period, we found that treatment with IFN-γ–neutralizing antibodies restored the ARE-del BM HSPC composition to closely resemble that in WT mice, from high LT-HSCs and low CMPs, GMPs, and MEPs to low LT-HSCs and high CMPs, GMPs, and MEPs (Figure 6F). The neutralizing antibody treatment was also able to restore erythropoiesis in ARE-del mice. We observed an increased percentage of mature erythrocytes (R4) and reduced frequency of immature erythrocytes (R2) compared with the ARE-del mice control group, indicating a rescue of erythroid development (Figure 6G). These results demonstrated that blocking IFN-γ signaling ameliorates the thrombocytopenia and corrects the BM phenotype of ARE-del mice, which further validates the role of IFN-γ in AA pathology in ARE-del mice.

Discussion

In this study, we provide evidence that IFN-γ can lead to AA by inhibition of hematopoiesis in a cell-intrinsic manner. During hematopoiesis, MPPs differentiate into CMPs which differentiate into GMPs and MEPs that give rise to myeloid cells, RBCs, and platelets. IFN-γ inhibits hematopoiesis by disrupting CMP generation and hampers the proliferation of CMPs, GMPs, and MEPs, which would have a severe impact on hematopoiesis and eventually lead to an empty marrow and pancytopenia. Furthermore, we observed disruptions of both B-cell and erythrocyte-lineage differentiation in ARE-del mice, which further contributes to the pathology of pancytopenia (supplemental Figure 7). We have shown that the disruption in hematopoiesis in ARE-del mice is not a result of a dysfunctional BM niche but rather a result of a cell-intrinsic IFN-γ inhibitory effect on HSPCs and lineage differentiation. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that IFN-γ contributes to AA by affecting the BM microenvironment in a nonhematopoietic-related fashion. Further studies are needed to fully elucidate the possible effects of IFN-γ on the BM niche.

Among the reports on the impact of IFN-γ on hematopoiesis, our study is the first to identify the stages of hematopoiesis on which IFN-γ has an inhibitory effect. Similar to the result we report, Sellerri et al have reported the inhibitory effect of IFN-γ using an in vitro culturing system with decreased cultured HSPC cell numbers and functionality.26 Their results imply that IFN-γ inhibits hematopoiesis in part by inducing apoptosis; however, we did not observe such a phenomena in our mice. Maintenance of HSPCs requires a specialized BM niche that is difficult to duplicate in vitro. Although Sellerri and colleagues cultured HSPCs with stromal cells, that system does not recapitulate the BM niche, which may explain the difference in their observation regarding apoptosis. In addition, we found that the strength of IFN-γ signaling may account for differences in the results. The phenotypes of ARE-del heterozygotes, which express less IFN-γ than ARE-del homozygotes, appear to be normal. This observation implies that IFN-γ signaling strength may significantly contribute to the effect of IFN-γ on hematopoiesis. The IFN-γ concentration used in Sellerri’s system is between 1 and 50 ng/mL, whereas the concentration in the BM plasma in our mice is ∼10 pg/mL (data not shown). It is possible that inducing apoptosis requires stronger IFN-γ signaling strength, which could explain the lack of apoptosis in our system.

In addition to IFN-γ, increased TNF-α expression has been associated with AA and was shown to inhibit erythropoiesis in vitro.27-29 Because we could detect TNF-α in the serum of both ARE-del mice and ARE-del>WT chimeras (data not shown), we cannot rule out the involvement of TNF-α in AA pathology in ARE-del mice. However, the observations that IFN-γ suppresses the proliferation of CMPs and MEPs in vitro and that neutralizing IFN-γ restores erythropoiesis indicate that IFN-γ plays a role in erythropoiesis inhibition in ARE-del mice. However, the fact that TNF-α expression is stimulated by IFN-γ and that both cytokines activate nuclear factor kappa B make it difficult to identify which cytokine is causative. It is possible that the AA pathology observed in ARE-del mice is a result of synergistic inhibition of IFN-γ and TNF-α. Nonetheless, the notion that IFN-γ and TNF-α are found in ARE-del mice further strengthens our model, because both cytokines can also be found in the BM plasma of AA patients.30

The majority of human AA is a consequence of autoreactive T cells destroying HSPCs in the BM. In this study, we provide evidence that deregulation of IFN-γ alone could result in AA pathology with a novel animal model that exhibits hypocellular marrow and peripheral pancytopenia, which closely resembles human AA. However, unlike in human AA, the pathology of ARE-del mice is entirely IFN-γ dependent, because we did not detect either T-cell infiltration in BM or abnormal BM T-cell clonal expansion. Because different levels of IFN-γ have different physiological outcomes,31,32 with the average IFN-γ concentration in ARE-del BM plasma (∼10 pg/mL) similar to the levels in the BM of AA patients (<75 pg/mL),33 we believe that the ARE-del model provides an opportunity to investigate and define the physiological effects of endogenous IFN-γ on hematopoiesis. In addition, the unique characteristic of the ARE-del model, chronic expression of IFN-γ, also offers an opportunity to develop better treatment options for AA patients by identifying and testing approaches to blocking chronic cytokine production.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the technical support of Kathleen Noer and Roberta Matthai and thank Dr Giorgio Trinchieri for the generous gifts of IFN-γ neutralizing and control antibodies, Dr Jerrold Ward for his pathological analysis, and Drs Arthur Hurwitz, Steve Anderson, and Ram Savan and the National Institutes of Health Fellows Editorial Board for their critical review of the manuscript.

This work is supported by National Cancer Institute intramural funding and National Institutes of Health grant Z1A BC009283-30.

Authorship

Contribution: F.-c.L. helped design, perform, and interpret the experiment and write the manuscript; M.K. and B.S. helped perform the experiment; D.L.H. helped design and generate the mouse strain; T.C. helped design the experiment; K.C.B. helped perform and interpret the experiment; and J.R.K. and H.A.Y. supervised the project and provided input into experimental design and data interpretation.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Fan-ching Lin, Cancer and Inflammation Program, PO Box B, Building 560, Room 31-16, Frederick, MD 21702; e-mail: fanching.lin@nih.gov; Jonathan R. Keller, Hematopoiesis and Stem Cell Biology Section, PO Box B, Building 560, Room 12-03, Frederick, MD 21702; e-mail: kellerjo@mail.nih.gov; and Howard A. Young, Cancer and Inflammation Program, PO Box B, Building 560, Room 31-16, Frederick, MD 21702; e-mail: younghow@mail.nih.gov.

References

Author notes

J.R.K. and H.A.Y. were joint principal investigators for this study.

![Figure 6. ARE-del>WT chimera mice exhibit early signs of BM failure with HSPC composition similar to that of ARE-del mice. BM phenotype of chimeric mice was evaluated 8 weeks after reconstitution. (A) The bar graph shows the total BM cell number from WT>WT and ARE-del>WT (n = 8). (B) T-cell population in BM of chimeric mice was analyzed by using 7-color flow cytometry analyses. T cells were gated on live NKp46–CD11b–B220–Gr1–CD3+ populations. Bar graphs show both the total cell number of T cells and the percentage of live cells (n = 8). (C) The function of T cells in chimeric BM was determined by the intensity of cytokine responses against TCR agonists (anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibodies [Abs]). Cytokine levels in the medium were measured 6 hours after stimulation by using a cytometric bead array. The bar graphs displays the concentration of each cytokine measured (n = 8). (D) HSPC composition in the BM of chimeric mice was analyzed on lineage– BM cells by using flow cytometry. The bar graph shows the total cell number of each cell type (n = 8). (E) Total BM cells from WT>WT and ARE-del>WT mice were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies for lineage differentiation analysis. Dots plots are representative of 1 set of 3 experiments. (F) BM cells from all 4 groups (WT/control, WT/neutralizing, knockout (KO)/control and KO/neutralizing) were analyzed for LSK and LK populations and (G) erythropoiesis. Density and dot plots are representatives of 1 set of 3 experiments. Results are expressed as mean ± SD. *P < .05; **P < .01; ****P < .0001](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/124/25/10.1182_blood-2014-01-549527/4/m_3699f6.jpeg?Expires=1767756489&Signature=OQnCoS0ipYRnQ1eGKjNRfQobjCS-QCi2k33e5LFV2heFtZoM8GwnXM9rwachpnJK4t2JlkUlsbAyHhe85FM53yzyKEWGeNEw6DXTiOg~Ljv5g4DMtIpYw71ThucAaHHspMVZBE9z6TM8BBa2YKgKtHbrrx12Lf9nG-v3amJ23hossvynyTHoWpcAIf3HAUaTSnaOW0Nb~Y-qXGiem6BQRa2JUkoJ4ridZuaezf87RF2rDns2hB7kgDSxKK5JSkQzvkFAV-hOSSyez93cU9zWc7ueOK-JzNnD8zGpXFjdz~Wx70LgsY~nOY1qd7b6B3FNo9r2BD4cuCUoB58oLg5WJQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 6. ARE-del>WT chimera mice exhibit early signs of BM failure with HSPC composition similar to that of ARE-del mice. BM phenotype of chimeric mice was evaluated 8 weeks after reconstitution. (A) The bar graph shows the total BM cell number from WT>WT and ARE-del>WT (n = 8). (B) T-cell population in BM of chimeric mice was analyzed by using 7-color flow cytometry analyses. T cells were gated on live NKp46–CD11b–B220–Gr1–CD3+ populations. Bar graphs show both the total cell number of T cells and the percentage of live cells (n = 8). (C) The function of T cells in chimeric BM was determined by the intensity of cytokine responses against TCR agonists (anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibodies [Abs]). Cytokine levels in the medium were measured 6 hours after stimulation by using a cytometric bead array. The bar graphs displays the concentration of each cytokine measured (n = 8). (D) HSPC composition in the BM of chimeric mice was analyzed on lineage– BM cells by using flow cytometry. The bar graph shows the total cell number of each cell type (n = 8). (E) Total BM cells from WT>WT and ARE-del>WT mice were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies for lineage differentiation analysis. Dots plots are representative of 1 set of 3 experiments. (F) BM cells from all 4 groups (WT/control, WT/neutralizing, knockout (KO)/control and KO/neutralizing) were analyzed for LSK and LK populations and (G) erythropoiesis. Density and dot plots are representatives of 1 set of 3 experiments. Results are expressed as mean ± SD. *P < .05; **P < .01; ****P < .0001](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/124/25/10.1182_blood-2014-01-549527/4/m_3699f6.jpeg?Expires=1767756490&Signature=QWD2m54e~f4MLv57kZDWilUJ9TapF6e1oz19E-6G-Dnpasn2U~4fNI8iN0cGxJMhibd1Qp5uaXcnX4J8nTYLdgWrt~SD-t32lwU-dLnmcGTbqq5jbwqSyysGrQAywfJS8pLJ1lwbd367GuXHzQj9i3j8If9vEE5Nxo7eV9b1f43SNahPqBqqhDkWvFzKdbo1914b8L-5gZDT2mrOZbVb9LKRrRRMJKx4UU1uvmJf9yCftv3IRhSPv5ZJsPj1pe978mX6eBemSU2coeqqKGQmzwCvlhim-9p2wuCRz5N8sEMsy8Z0sOsDFqwT24ct6Fp5L9qaZsEPqaLLjqhZmXdBlg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)