Key Points

FVNara (W1920R), associated with serious deep vein thrombosis, is more resistant to APC relative to FVLeiden (R506Q).

This mechanism results from significant decreases in FVa susceptibility to APC and FV cofactor activity for APC.

Abstract

Factor V (FV) appears to be pivotal in both procoagulant and anticoagulant mechanisms. A novel homozygote (FVNara), a novel mechanism of thrombosis associated with Trp1920→Arg (W1920R), was found in a Japanese boy and was associated with serious deep vein thrombosis despite a low level of plasma FV activity (10 IU/dL). Activated partial thromboplastin time–based clotting assays and thrombin generation assays showed that FVNara was resistant to activated protein C (APC). Reduced susceptibility of FVaNara to APC-catalyzed inactivation and impaired APC cofactor activity of FVNara on APC-catalyzed FVIIIa inactivation contributed to the APC resistance (APCR). Mixtures of FV-deficient plasma and recombinant FV-W1920R confirmed that the mutation governed the APCR of FVNara. APC-catalyzed inactivation of FVa-W1920R was significantly weakened, by ∼11- and ∼4.5-fold, compared with that of FV–wild-type (WT) and FVLeiden (R506Q), respectively, through markedly delayed cleavage at Arg506 and little cleavage at Arg306, consistent with the significantly impaired APC-catalyzed inactivation. The rate of APC-catalyzed FVIIIa inactivation with FV-W1920R was similar to that without FV, suggesting a loss of APC cofactor activity. FV-W1920R bound to phospholipids, similar to FV-WT. In conclusion, relative to FVLeiden, the more potent APCR of FVNara resulted from significant loss of FVa susceptibility to APC and APC cofactor activity, mediated by possible failure of interaction with APC and/or protein S.

Introduction

Factor V (FV) contributes to opposing mechanisms in the regulation of coagulation.1,2 The procoagulant action of FV is associated with cofactor activity for FXa in the prothrombinase complex, which catalyzes the conversion of prothrombin to thrombin on a phospholipid (PL) surface.3-5 FV is converted to FVa by proteolytic cleavage by thrombin. Development of a hypercoagulant state is controlled by downregulation by activated protein C (APC) with protein S (PS). Hence, FVa is rapidly inactivated by proteolytic cleavage of the heavy chain (HCh) at Arg306, Arg506, and Arg679.6,7 Cleavage at Arg506 is essential for the exposure of other cleavage sites but is not directly required for the decrease in activity. Cleavage at Arg306 results in near-complete loss of FVa activity. Nevertheless, any defect of 1 or more cleavage reactions significantly affects the processes of APC-induced inactivation.8,9 The alternative function of FV is as an anticoagulant cofactor of APC in FVIIIa inactivation.1 FVIIIa functions as a cofactor in the tenase complex and is responsible for PL-dependent FXa generation by FIXa.10-12 In the process of APC-induced FVIIIa inactivation, FV acts as an anticoagulant cofactor of APC with PS, resulting in acceleration of FVIIIa inactivation through cleavage at Arg336.13,14 This anticoagulant activity of FV is mediated by a product of proteolysis by APC before cleavage by thrombin. Cleavage at Arg506 of FV attached to the B domain is essential to the anticoagulant activity of FV, whereas cleavage at Arg306 appears to contribute less to this mechanism.15,16 Any molecular defect of these cleavage reactions confers APC resistance (APCR).1

A point mutation of the F5 gene, Arg506→Gln (R506Q; FVLeiden), is the major cause of APCR2 and is detected in ∼20% of Caucasians with deep venous thrombosis (DVT).17,18 The loss of the APC cleavage site at Arg506 in FVLeiden results in a loss of APC-induced FVa inactivation and impairment of FV cofactor activity of APC in FVIIIa inactivation. Rare FV point mutations Arg306→Thr (R306T; FVCambridge)19,20 and Arg306→Gly (R306G; FVHong Kong)20,21 affect the APC cleavage site at Arg306 and are associated with mild APCR.22 No FV mutations linked to APCR have been identified in Japanese populations, however. We describe the findings in a Japanese boy with severe DVT in the paradoxical presence of FV deficiency with FV activity (FV:C) 10 IU/dL. We have identified a novel mechanism of thrombosis associated with a Trp1920→Arg (W1920R) mutation in the F5 gene (FVNara). The defect resulted in APCR more potent than that seen with FVLeiden.

Materials and methods

Blood samples were obtained after informed consent following local ethical guidelines. DNA direct sequencing and the expression of recombinant protein were approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of Tokyo Medical University. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Reagents

The pMT2/FV mammalian expression plasmid containing the full-length F5 cDNA was provided by Dr Kaufman (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI). The EZ1 DNA Blood Kit, QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit, and QIAfilter Plasmid Kit (Qiagen, Dusseldorf, Germany) and the QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) were purchased. Recombinant FVIII was a generous gift from Bayer Corporation, Japan. A monoclonal antibody (mAb)C5,23 recognizing the C-terminus of the FVIII A1 domain, was provided by Dr Carol Fulcher (Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA). FV, FIXa, FX, FXa, α-thrombin, APC, PS, mAbAHV-5146 against the FV HCh (Hematologic Technologies, Essex Junction, VT), lipidated TF (Innovin; Dade Behring, Marburg, Germany), and fluorogenic substrate Z-Gly-Gly-Arg-AMC (Bachem, Bubendorf, Switzerland) were purchased commercially. FV-deficient plasmas (George King. Overland Park, KS), PT, and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) reagent (Instrumentation Laboratory, Bedford, MA; Sysmex, Kobe, Japan) were purchased. PL vesicles containing phosphatidylserine/phosphatidylcholine/phosphatidylethanolamine, 10%/60%/30%, were prepared using N-octylglucoside.24

DNA direct sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from leukocytes, using the BioRobot EZ1 workstation. PCR assays were performed with Taq DNA polymerase (TaKaRa-Bio, Otsu, Japan). PCR products were electrophoresed on agarose gels and purified by gel extraction. Purified PCR products from genomic DNA and F5 plasmids were confirmed by sequencing using a BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems) and analyzed with a 3730 DNA analyzer. All sequences were compared with wild-type (WT) F5 sequences (GenBank number Z99572).

Expression of recombinant FV

The mutations were introduced independently into a pMT2/FV plasmid by site-directed mutagenesis.25 The WT and mutant plasmids used in transfection experiments were purified. Vectors expressing recombinant proteins were transfected into HEK293 cells, using the lipofection method. After 60 hours, the culture media and cells were harvested. Conditioned media (CM) were collected, centrifuged to remove cell debris, and stored at −80°C. FV antigen (FV:Ag) levels in CM and cell lysates were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Affinity Biologicals). FV:C in CM was measured in PT-based clotting assays, using the ACL9000 coagulation analyzer (Instrumentation Laboratory). The specific activity of FV was calculated as the ratio of FV:C to the concentration of FV:Ag, both of which were measured in CM. The proteins were harvested in serum-free medium and concentrated by filtration (cutoff ∼100 kDa).

APCR assay

aPTT-based assays.

The APC-resistance kit, which is not approved and not commercially available in Japan, was provided by Instrumentation Laboratory for research use. This assay was performed using ACL9000 with predilution of sample plasmas in FV-deficient plasma. The APC sensitivity ratios (APCsrs) were expressed as ratios of aPTT clotting times in the presence of APC divided by clotting times in its absence. This assay reflects the effect of APC on inactivation of both FVa and FVIIIa; hence, a low level of APCsr indicates a defect in the inactivation of FVa and/or FVIIIa and, consequently, reflects APCR.

Thrombin generation-based assays.

Calibrated automated thrombin generation assay (Thrombinoscope) was performed as previously reported.26 Platelet-poor plasma (PPP) or platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was preincubated for 10 minutes with TF (5 pM), APC (8 or 40 nM), and PL (0 or 10 μM), respectively. PRP was adjusted to 15 × 104 platelets/μL. Measurements were commenced after the addition of CaCl2 and fluorogenic substrate (final concentration [f.c.] 16.7 mM and 417 μM, respectively). Fluorescent signals were monitored continuously in a Fluoroskan microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Franklin, MA). For data analyses, the parameters (lag time, peak thrombin, time to peak, and endogenous thrombin potential [ETP]) were derived. The APCsrs were expressed as ratios of the parameter in the absence (or presence) of APC, divided by the ratio in its presence (or absence).

FXa generation-based assays.

Normal or patient’s plasma was mixed with FV-deficient plasma in various proportions and assayed using the FXa generation assay (COATEST SP-FVIII, Chromogenix, Milan, Italy), with minor modifications.27 The test specifically quantifies FVIIIa:C in 16-fold diluted plasma by measuring intrinsic FXa generation mediated by excess exogenous FIXa and FX with PL. The simultaneous addition of APC (40 nM) with cofactors PS and FV in plasma inhibits intrinsic FXa generation by inactivating FVIIIa. The APCsrs were expressed as ratios of the amount of generated FXa in the absence of APC divided by that in its presence. A low level of APCsr indicates a defect in FVIIIa inactivation and, consequently, reflects APCR.

Prothrombinase assay

FV (2 nM) was activated by thrombin (20 nM) for 1 minute, followed by the addition of hirudin. The reactants were mixed with prothrombin (1.4 μM), PL, and 5-dimethylamino-naphthalene-1-sulfonylarginine-N-(3-ethyl-1,5-pentanediyl)-amide (30 μM), followed by initiation by the addition of FXa (10 pM). Aliquots were removed to assess the initial rates of product formation, and the reactions were quenched with EDTA (f.c. 50 mM). Rates of thrombin generation were determined at absorbance 405 nm (Abs405) after the addition of S-2238 (f.c. 0.46 mM). Thrombin generation was quantified from a standard curve prepared using known amounts of thrombin.

FV–PL binding

Binding of FV to immobilized PL was examined in ELISAs.28 α-phosphatidyl-L-serine (5 μg/mL) in methanol was added to microtiter wells and air-dried. The wells were blocked by the addition of gelatin solution (5 mg/mL), and serial dilutions of FV were added and incubated at 37°C for 2 hours. Bound FV was quantified by the addition of anti-FV mAbAHV-5146 (2.5 μg/mL) and goat anti-mouse peroxidase-linked antibody, followed by measuring at Abs492. The amount of nonspecific immunoglobulin G (IgG) binding without FV was <3% of the total signal. Specific binding was estimated by subtracting the amount of nonspecific binding.

APC-catalyzed inactivation of FVa

FV (8 nM) was incubated with thrombin (100 nM) for 5 minutes at 37°C, and reaction was terminated by the addition of hirudin (25 U/mL). Samples containing the generated FVa (2 nM) were incubated with APC (25 pM), and PS (30 nM) with PL (20 μM), for the indicated times. Aliquots were obtained from the mixtures and diluted ∼30-fold. Residual FV:C was measured in aPTT-based clotting assays. The presence of thrombin and hirudin in the diluted samples had little effect in these assays.

APC cofactor activity of FV

The APC cofactor activity of FV variants was measured in a FVIIIa degradation assay,29 with minor modifications. FVIII (10 nM) and PL (20 μM) were activated by thrombin (5 nM) for 30 seconds, and the reaction was terminated by the addition of hirudin (2.5 U/mL). The generated FVIIIa was then incubated with APC (0.5 nM) and PS (5 nM) with various concentrations of FV variants for 20 minutes. The reactants were diluted 9-fold before incubation with FIXa (2 nM) and FX (200 nM) for 1 minute. Generated FXa was measured in a chromogenic assay with S-2222 at Abs405. Relative FVIII:C was calculated from the amounts of generated FXa.

Western blotting

Sodium dodecyl sulfate/polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was performed using 8% gels, followed by western blotting.30 Protein bands were probed using the indicated mAbs, followed by the addition of goat anti-mouse peroxidase-linked antibody.30 Signals were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence, and densitometric scans were quantified using Image J 1.34.

Results

Patient’s profile

A 13-year-old boy was admitted for massive DVT in association with swelling of the lower extremities. There was no personal or family history of thrombosis. Laboratory findings demonstrated prolonged PT and aPTT (18.9/67.6 seconds; control, 12.2/30.2 seconds). FV:C and FV:Ag were 10 and 40 IU/dL, respectively, indicating a cross-reactive material–reduced reaction. Anti-FV inhibitor was not detected. Other procoagulant and anticoagulant factors, including fibrinolytic factors and antiphospholipid syndrome-associated factors, were within normal range. Free tissue factor pathway inhibitor was 20.2 ng/mL (normal, 15-35 ng/mL).31 His parents and 3 siblings had normal levels of FV:C and FV:Ag (Table 1). He was treated with warfarin to maintain prothrombin time-international normalized ratio 2.5 to 3.0. Nevertheless, a fresh thrombus developed in his left external iliac-vein, and the right inferior vena cava was completely occluded. After heparinization and urokinase therapy, the patient was treated with higher doses of warfarin to maintain prothrombin time-international normalized ratio 4.0 to 5.0, and he has since been free of recurrent DVT.

Gene analysis

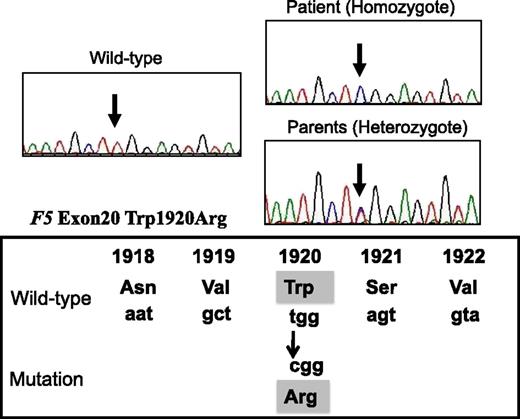

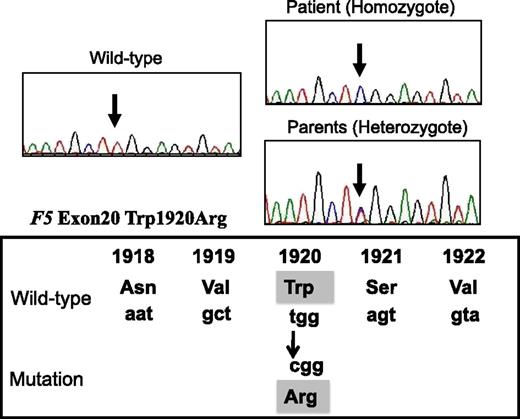

Direct sequencing identified a W1920R homozygous mutation of exon 20 of F5 in the patient (Figure 1). His parents heterozygously carried this mutation, but it was undetected in his siblings. Neither the FVLeiden mutation (R506Q) nor FV-HR2 haplotype (H1299R and D2194G) were found in the patient or his family members. The W1920R mutation was not detected in 100 alleles from Japanese control subjects using direct sequencing, and the novel F5 missense mutation that we identified was designated FVNara.

DNA direct sequencing of exon 20 of F5 gene from the patient, his parents, normal WT. The mutation (T–C) is present at codon 1920, resulting in a Trp1920→Arg substitution in the FV protein (FVNara).

DNA direct sequencing of exon 20 of F5 gene from the patient, his parents, normal WT. The mutation (T–C) is present at codon 1920, resulting in a Trp1920→Arg substitution in the FV protein (FVNara).

APCR in FVNara plasma

We investigated whether the FVNara was resistant to APC. aPTT-based APCR assays, reflecting APC inactivation of FVa and FVIIIa, were performed. The APCsr obtained in patient’s plasma was similar to those of FVLeiden patients and significantly lower than those in healthy control patients (Table 1). APCsrs in the parents were intermediate, and those in the siblings were equal to the levels of healthy controls. APCsrs of 3 mild FV-deficient patients with FV:C ∼50 IU/dL were similar to those of control. APCsrs of inherited FV-deficient patients with FV:C ∼10 IU/dL were not measurable, however, because the clotting times after the addition of APC were markedly prolonged (data not shown). These results demonstrated that the FVNara mutation conferred APCR.

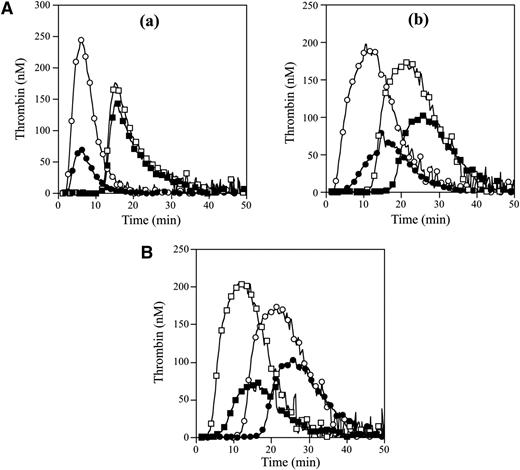

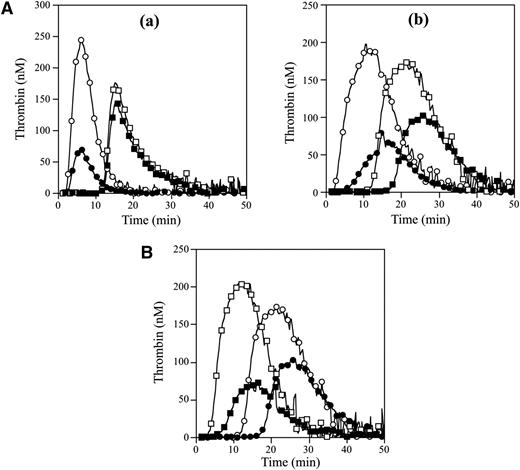

APCR in the FVNara patient was examined using PPP in thrombin generation assay initiated by low concentrations of TF with APC. The time-related parameters (lag time and time to peak) and peak thrombin obtained with FVNara PPP were prolonged and decreased, respectively, compared with control (Figure 2Aa and Table 2). The addition of APC showed that the peak thrombin and ETP with FVNara were less moderated than those with control, although the time-related readings were unaffected. The APCsrs (minus APC/plus APC) with FVNara (1.22 and 1.25) were significantly lower than those with control (3.48 and 3.70), supportive of the APCR with FVNara. Platelet FV also participates in the clotting function of FV; to evaluate the role of platelet FV in these mechanisms, therefore, experiments were repeated using PRP. Similar to PPP, the addition of APC showed that APCsrs (plus APC/minus APC) in time-related parameters in FVNara were lower than those in control, and the APCsrs (minus APC/plus APC) with FVNara were also lower than those with control (Figure 2Ab). These findings provided further evidence of APCR with FVNara. Similar experiments in PPP using 40 nM APC (equal amount in PRP) showed that the thrombin generation of FVNara, as well as normal plasma, was little detected (data not shown), again confirming that the platelet FV was particularly resistant to APC-mediated inactivation.

Thrombin generation in the FVNara patient’s plasma. (A) Effects of the addition of APC: thrombin generation after extrinsic activation (TF; 5 pM) of PPP (a) or PRP (b) in normal individuals (circle symbols) and PPP (a) or PRP (b) in FVNara patient (square symbols) in the absence (open symbols) or presence (closed symbols) of APC was measured as described in “Materials and methods.” With PPP, APC (8 nM) was added with PL vesicles (10 μM), whereas with PRP, APC (40 nM) was added without PL. A representative thrombogram is shown. (B) Effects of the addition of native FV: thrombin generation was measured after extrinsic activation (TF; 5 pM) of the patient’s PRP with the addition of native FV (circles, 0 IU/dL; squares, 10 IU/dL) in the absence (open symbols) or presence (closed symbols) of APC (40 nM). All experiments were performed at least 3 separate times, and a representative thrombogram is shown.

Thrombin generation in the FVNara patient’s plasma. (A) Effects of the addition of APC: thrombin generation after extrinsic activation (TF; 5 pM) of PPP (a) or PRP (b) in normal individuals (circle symbols) and PPP (a) or PRP (b) in FVNara patient (square symbols) in the absence (open symbols) or presence (closed symbols) of APC was measured as described in “Materials and methods.” With PPP, APC (8 nM) was added with PL vesicles (10 μM), whereas with PRP, APC (40 nM) was added without PL. A representative thrombogram is shown. (B) Effects of the addition of native FV: thrombin generation was measured after extrinsic activation (TF; 5 pM) of the patient’s PRP with the addition of native FV (circles, 0 IU/dL; squares, 10 IU/dL) in the absence (open symbols) or presence (closed symbols) of APC (40 nM). All experiments were performed at least 3 separate times, and a representative thrombogram is shown.

To further assess the contribution of plasma FV in the APCR of FVNara, normal FV was added to the patient’s PRP before measuring thrombin generation with APC (Figure 2B). In the presence of normal FV (10 IU/dL) corresponding to the level in patient’s plasma, the time-related parameters were moderately shortened, and the peak thrombin and ETP were slightly increased. Thus, the presence of native FV improved reactivity to APC in FVNara PRP, suggesting that the APCR of FVNara might be caused by defective patient’s plasma FV. Furthermore, even small amounts of plasma FV appeared to influence APC-induced deceleration of blood coagulation.

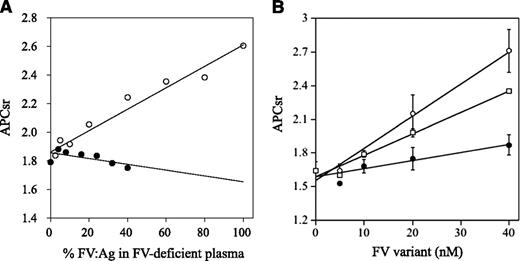

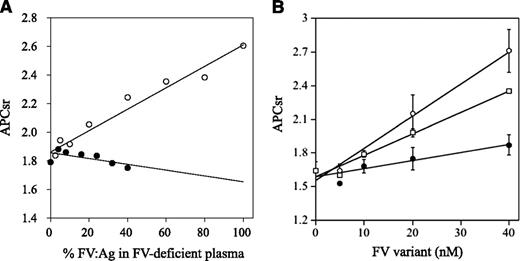

APC cofactor activity of FVNara

APCR resulting from a F5 mutation or mutations is caused by a reduced sensitivity of FVa to APC-catalyzed inactivation7,32 and/or reduced FV cofactor activity in APC-catalyzed FVIIIa inactivation,33 but these components are difficult to distinguish. FXa generation assays, reflecting intrinsic tenase activity, were used to examine the APC cofactor activity of FV.27 We therefore determined APCsrs in samples after the addition of APC to probe APCR resulting from defective FV cofactor activity. Normal or FVNara plasma was mixed with FV-deficient plasma in proportions from 2.5% to 100%. Because FVNara:Ag was 40 IU/dL, the concentration of FVNara in these assays varied between 2.5% and 40%. APCsrs increased linearly in proportion to the level of normal FV, and clear differences were demonstrated between 0% and 100% normal plasma (1.8 and 2.6, respectively), similar to an earlier report.27 APCsrs were independent of the concentration of FVNara, however, and remained relatively constant or modestly decreased (Figure 3A). The slopes obtained with normal and FVNara plasmas (ΔAPCsr; 0.72 and −0.18/IU FV, respectively) were significantly different (P < .01), indicating that FVNara possessed little APC cofactor activity.

APCR in FXa generation assays. (A) Effects of FV levels on the APCsr in the FVNara plasma. Normal plasma (open circles) and the patient’s plasma (closed circles) were mixed with FV-deficient plasma in various proportions, and FXa generation was measured with COATEST SP FVIII after the simultaneous addition of APC (40 nM) as described in “Materials and methods.” The APCsrs were expressed as ratios of the amount of generated FXa in the absence of APC divided by that in its presence. All experiments were performed at least 3 separate times, and the average values are shown. (B) APCR of FV-deficient plasma mixed with recombinant FV-W1920R. Various concentrations of FV (WT, open circles; W1920R, closed circles; R506Q, open squares) were mixed with diluted FV-deficient plasma, and FXa generation was measured with COATEST SP FVIII after the simultaneous addition of APC (40 nM), as described in “Materials and methods.” The APCsrs were expressed as ratios of the amount of generated FXa in the absence of APC divided by that in its presence. All experiments were performed at least 3 separate times, and the average and/or standard deviation values are shown.

APCR in FXa generation assays. (A) Effects of FV levels on the APCsr in the FVNara plasma. Normal plasma (open circles) and the patient’s plasma (closed circles) were mixed with FV-deficient plasma in various proportions, and FXa generation was measured with COATEST SP FVIII after the simultaneous addition of APC (40 nM) as described in “Materials and methods.” The APCsrs were expressed as ratios of the amount of generated FXa in the absence of APC divided by that in its presence. All experiments were performed at least 3 separate times, and the average values are shown. (B) APCR of FV-deficient plasma mixed with recombinant FV-W1920R. Various concentrations of FV (WT, open circles; W1920R, closed circles; R506Q, open squares) were mixed with diluted FV-deficient plasma, and FXa generation was measured with COATEST SP FVIII after the simultaneous addition of APC (40 nM), as described in “Materials and methods.” The APCsrs were expressed as ratios of the amount of generated FXa in the absence of APC divided by that in its presence. All experiments were performed at least 3 separate times, and the average and/or standard deviation values are shown.

APCR of FV-W1920R mutant

The measurements of APCR of FVNara could have been affected by quantitative or qualitative abnormalities of individual plasma components other than FV. To confirm FV specificity, recombinant FV-WT and 2 FV mutant proteins (W1920R and R506Q) were prepared. The levels of FV:Ag and specific activity of the W1920R mutant expressed in CM were similar to the data observed with patient’s plasma, at 50% and 45% of WT, respectively. Corresponding levels in CM of R506Q were 125% and 86% of WT, respectively.

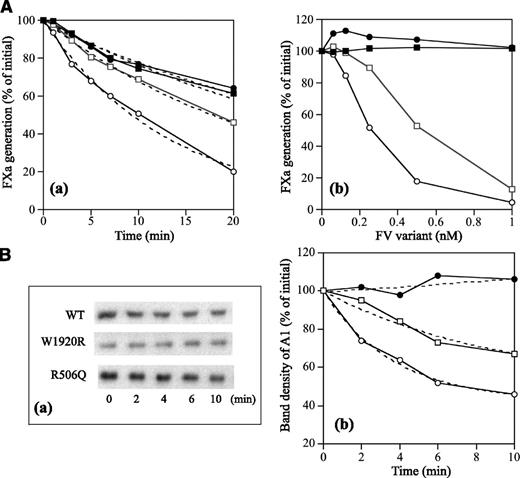

APCR assays were repeated using mixtures of FV-deficient plasmas and recombinant FV variants. FXa generation assays were devised in which FV-deficient plasma and FV were diluted 16-fold before mixing with APC; this facilitated measurements at lower levels of FV:Ag (0.3-2.5 nM). These concentrations were comparable to diluted plasma containing physiological levels of FV:Ag (5-40 nM; 15%-120% of normal FV:Ag). In mixtures with WT, APCsrs increased dose-dependently (ΔAPCsr; 2.85 × 10−2/nM FV; Figure 3B). The APCsr in W1920R was lower by ∼4-fold (0.71 × 10−2/nM FV) than WT, in keeping with the impairment of APC cofactor activity in W1920R. With R506Q, the APCsr was greater by ∼2.7-fold (1.91 × 10−2/nM FV) than that with W1920R. These findings demonstrated that APCR in FVNara plasma resulted from W1920R, and the APC cofactor activity of W1920R appeared to be more defective than that of R506Q.

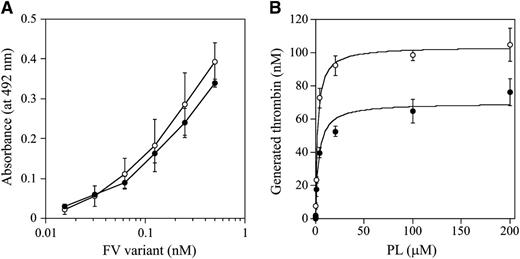

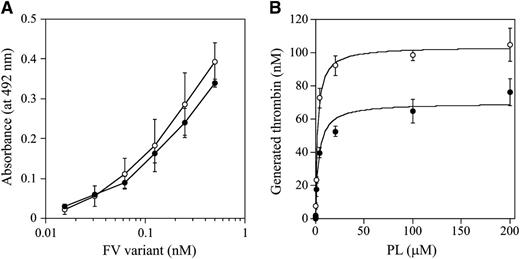

The C1 and/or C2 domains of FV(a) bind to PL membranes,34,35 which governs the susceptibility of FVa for APC-catalyzed inactivation and the APC cofactor activity of FV. W1920 is in proximity to the PL-binding region or regions,36 and we speculated that the APCR of FV-W1920R might be a result of significant disturbances in PL binding. The PL binding of W1920R was maintained at ∼90% that of WT in ELISA, however (Figure 4A). The influence of PL on prothrombinase activity with W1920R was also investigated. Thrombin generation with W1920R was ∼70% the level of that with WT, again supporting the cross-reactive material–reduced type on FVNara. However, the affinity of PL for W1920R was not significantly different compared with WT (Km: 3.25 ± 0.77/2.22 ± 0.24 μM, respectively; Figure 4B). Thrombin and PL-dependent FXa activation of W1920R showed a similar reaction to the activation of WT (data not shown). These findings indicated that W1920R–PL interactions were not disturbed.

FV-W1920R affecting the association with PL. (A) FV-PL binding. α-Phosphatidyl-L-serine (5 μg/mL) was added to microtiter wells and air-dried. After blocking, serial dilutions of FV were added to the immobilized PL. Bound FV-WT (open circles) and FV-W1920R (closed circles) was quantified by the addition of AHV-5146, as described in “Materials and methods.” The average values and standard deviations are shown. (B) The effects of PL on prothrombinase activity; FV (WT, open circles; W1920R, closed circles; 2 nM) was activated by thrombin (20 nM) for 1 minute, followed by the addition of hirudin. The reactants were incubated with prothrombin (1.4 μM) and various amounts of PL, followed by initiation by the addition of FXa (10 pM). Aliquots were removed, and the reactions were quenched by the addition of EDTA. Rates of thrombin generation were determined at Abs405 after the addition of S-2238. Thrombin generation was quantified by extrapolation from a standard curve prepared using known amounts of thrombin. The plotted data were fitted using the Michaelis-Menten equation. All experiments were performed at least 3 separate times, and the average values are shown.

FV-W1920R affecting the association with PL. (A) FV-PL binding. α-Phosphatidyl-L-serine (5 μg/mL) was added to microtiter wells and air-dried. After blocking, serial dilutions of FV were added to the immobilized PL. Bound FV-WT (open circles) and FV-W1920R (closed circles) was quantified by the addition of AHV-5146, as described in “Materials and methods.” The average values and standard deviations are shown. (B) The effects of PL on prothrombinase activity; FV (WT, open circles; W1920R, closed circles; 2 nM) was activated by thrombin (20 nM) for 1 minute, followed by the addition of hirudin. The reactants were incubated with prothrombin (1.4 μM) and various amounts of PL, followed by initiation by the addition of FXa (10 pM). Aliquots were removed, and the reactions were quenched by the addition of EDTA. Rates of thrombin generation were determined at Abs405 after the addition of S-2238. Thrombin generation was quantified by extrapolation from a standard curve prepared using known amounts of thrombin. The plotted data were fitted using the Michaelis-Menten equation. All experiments were performed at least 3 separate times, and the average values are shown.

APC-catalyzed inactivation of FVa-W1920R

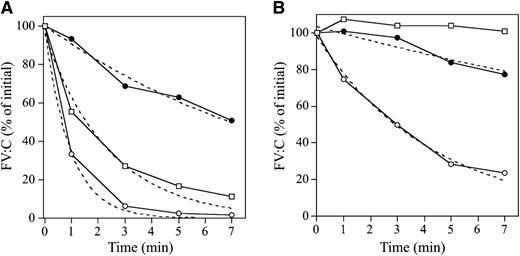

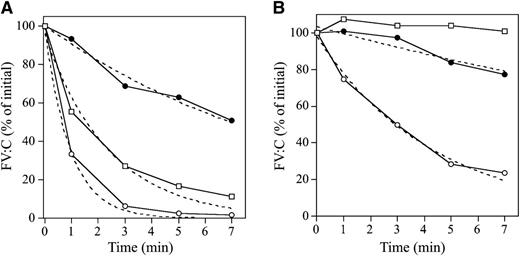

APC-catalyzed inactivation of FVa-W1920R, compared with the inactivation of WT and R506Q (FVLeiden), were examined in 1-stage clotting assays. FVa-WT:C was very rapidly decreased after the addition of APC and PS and declined to ∼2% of the initial level at 5 minutes (Figure 5A). FVa-R506Q:C was reduced to ∼20% of the initial level at 5 minutes. Surprisingly, FVa-W1920R:C decreased very slowly and persisted at ∼60% of the initial level. The inactivation rate of W1920R was ∼11- and ∼4.5-fold lower than the rates of WT and R506Q, respectively (Table 3), indicating significantly defective APC-induced inactivation of W1920R. Without PS, the inactivation rate of FVa-WT:C was significantly decreased, with ∼20% of the rate obtained with PS (Figure 5B), whereas inactivation of FVa-R506Q:C was not observed. The inactivation rate of FVa-W1920R:C appeared to be ∼40% less than that with PS, but this was ∼6-fold lower than that of WT, supporting the theory that W1920R as a cofactor for PS contributed less to the mechanisms of APCR than WT and R506Q.

APC-mediated inactivation of FVa-W1920R mutant. FV variants (8 nM) were incubated with thrombin (100 nM) for 5 minutes, and the reaction was terminated by the addition of hirudin (25 U/mL). FVa variant samples (2 nM) were reacted with APC (25 pM) and PL (20 μM) in the presence (A) or absence (B) of PS (30 nM). After dilution, FVa activity was measured in an aPTT-based 1-stage clotting assay. The symbols used are as follows: open circles, WT; closed circles, W1920R; open squares, R506Q. Initial activities of FVa variants were regarded as 100%. The plotted data were fitted in an equation of single exponential decay. All experiments were performed at least 3 separate times, and the average values are shown.

APC-mediated inactivation of FVa-W1920R mutant. FV variants (8 nM) were incubated with thrombin (100 nM) for 5 minutes, and the reaction was terminated by the addition of hirudin (25 U/mL). FVa variant samples (2 nM) were reacted with APC (25 pM) and PL (20 μM) in the presence (A) or absence (B) of PS (30 nM). After dilution, FVa activity was measured in an aPTT-based 1-stage clotting assay. The symbols used are as follows: open circles, WT; closed circles, W1920R; open squares, R506Q. Initial activities of FVa variants were regarded as 100%. The plotted data were fitted in an equation of single exponential decay. All experiments were performed at least 3 separate times, and the average values are shown.

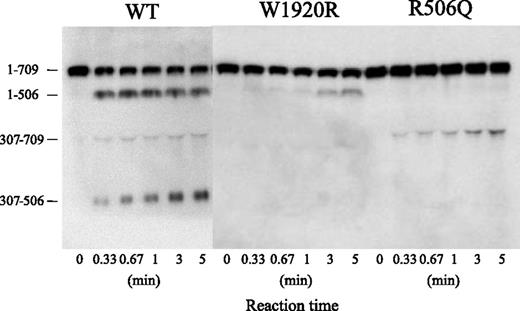

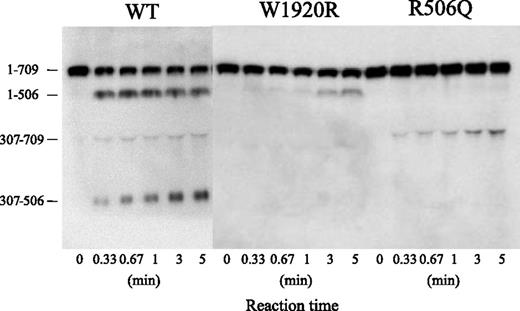

Sodium dodecyl sulfate/polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of APC cleavage was designed to investigate the mechanism or mechanisms contributing to the defective APC-catalyzed inactivation of FVa-W1920R (Figure 6). Using FVa-WT, the band of residues 1 to 506 rapidly appeared within 20 seconds after the addition of APC, followed sequentially by the appearances of the 307 to 506 and 307 to 709 bands, consistent with rapid, consecutive cleavage at Arg506 and Arg306. Cleavage of FVa-R506Q at Gln506 was not evident during a 5-minute reaction. The appearance of the 307 to 709 band was evident at similar velocity to that in WT, but the total ratio of Arg306 cleavage in R506Q was reduced. The appearance of the 1 to 506 band in W1920R was markedly delayed compared with WT, however, and cleavage at Arg306 was not detected. These results suggested that the loss of APC-catalyzed inactivation of FVa-W1920R was a result of a significant delay in cleavage at Arg506 and little cleavage at Arg306.

APC-catalyzed proteolytic cleavage of the HCh of FVa-W1920R. FV variants (8 nM) were incubated with thrombin (100 nM) for 5 minutes, and the reaction was terminated by the addition of hirudin (25 U/mL). FVa variant samples (0.5 nM) were incubated with APC (1 nM) and PS (30 nM) in the presence of PL (20 μM) for the indicated times. Samples were analyzed on 8% gels, followed by western blotting using an anti-FV HCh mAb 5146 IgG, as described in “Materials and methods.” A vertical line is inserted to indicate a repositioned gel lane.

APC-catalyzed proteolytic cleavage of the HCh of FVa-W1920R. FV variants (8 nM) were incubated with thrombin (100 nM) for 5 minutes, and the reaction was terminated by the addition of hirudin (25 U/mL). FVa variant samples (0.5 nM) were incubated with APC (1 nM) and PS (30 nM) in the presence of PL (20 μM) for the indicated times. Samples were analyzed on 8% gels, followed by western blotting using an anti-FV HCh mAb 5146 IgG, as described in “Materials and methods.” A vertical line is inserted to indicate a repositioned gel lane.

Cofactor FV-W1920R on APC-catalyzed FVIIIa inactivation

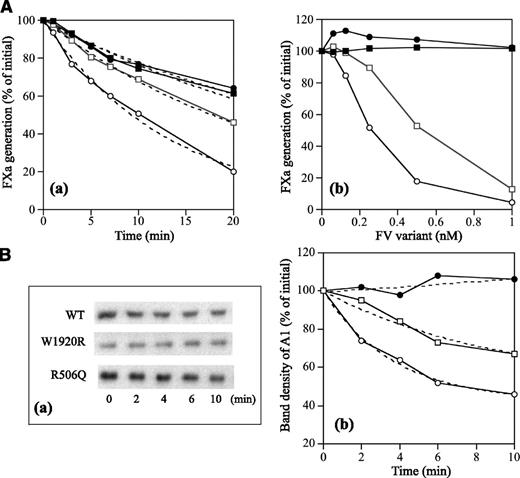

Properties of FV-W1920R as a cofactor for APC were examined in a FVIIIa degradation assay.29 FV-WT significantly enhanced APC-catalyzed FVIIIa inactivation with a ∼3-fold inactivation rate compared with that in its absence, again confirming the APC cofactor activity of FV (Figure 7Aa and Table 4). FV-R506Q moderately diminished APC-catalyzed inactivation with the ∼50% inactivation rate of WT. However, the rate with W1920R was similar to that in its absence, emphasizing earlier findings that APC cofactor activity was markedly depleted with W1920R. With regard to the effects of varying amounts of FV on APC cofactor activity, FV-WT enhanced the APC-catalyzed inactivation dose-dependently (50% reduction, 0.25 nM) (Figure 7Ab). Inactivation with R506Q was also enhanced, but the 50% reduction of 0.55 nM was greater than that with WT. However, even at 1 nM of W1920R, little enhancement of this mechanism was demonstrated, indicating that impairment of APC cofactor activity with W1920R was more pronounced than with R506Q.

APC cofactor activity of FV-W1920R assessed by the degradation of FVIIIa. (A) FVIIIa inactivation. FVIII (10 nM) with PL (20 μM) was activated by thrombin (5 nM), followed by the addition of hirudin (2.5 U/mL). Generated FVIIIa was incubated either with mixtures of APC (0.5 nM), PS (5 nM), and FV variants (0.5 nM) for the indicated times (a) or with various concentrations of FV variants for 20 minutes (b). FXa generation was initiated by the addition of FIXa (2 nM) and FX (200 nM) for 1 minute. The symbols used are as follows: open circles, WT; closed circles, W1920R; open squares, R506Q; closed squares, no FV. Values of FXa generation at the initial time (a) or in the absence of FV variants (b) were regarded as 100%. The data in (a) were fitted on an equation of single exponential decay (dashed lines). All experiments were performed at least 3 separate times, and the average values are shown. (B) A1 cleavage at Arg336; FVIII (10 nM) with PL (20 μM) was activated by thrombin (5 nM) for 30 second, followed by the addition of hirudin (2.5 U/mL). Generated FVIIIa was incubated with mixtures of APC (0.5 nM), PS (5 nM), and FV variants (0.5 nM) for the indicated times. Samples were analyzed on 8% gels, followed by western blotting using an anti-A1 C5 IgG, as described in “Materials and methods” (a). Band densities of intact A11-372 observed from panel a were measured by quantitative densitometry. Density before the addition of APC was regarded as 100% (b). The plotted data were fitted in an equation of single exponential decay (dashed lines). The symbols used are as follows: open circles, WT; closed circles, W1920R; open squares, R506Q. All experiments were performed at least 3 separate times, and the average values are shown.

APC cofactor activity of FV-W1920R assessed by the degradation of FVIIIa. (A) FVIIIa inactivation. FVIII (10 nM) with PL (20 μM) was activated by thrombin (5 nM), followed by the addition of hirudin (2.5 U/mL). Generated FVIIIa was incubated either with mixtures of APC (0.5 nM), PS (5 nM), and FV variants (0.5 nM) for the indicated times (a) or with various concentrations of FV variants for 20 minutes (b). FXa generation was initiated by the addition of FIXa (2 nM) and FX (200 nM) for 1 minute. The symbols used are as follows: open circles, WT; closed circles, W1920R; open squares, R506Q; closed squares, no FV. Values of FXa generation at the initial time (a) or in the absence of FV variants (b) were regarded as 100%. The data in (a) were fitted on an equation of single exponential decay (dashed lines). All experiments were performed at least 3 separate times, and the average values are shown. (B) A1 cleavage at Arg336; FVIII (10 nM) with PL (20 μM) was activated by thrombin (5 nM) for 30 second, followed by the addition of hirudin (2.5 U/mL). Generated FVIIIa was incubated with mixtures of APC (0.5 nM), PS (5 nM), and FV variants (0.5 nM) for the indicated times. Samples were analyzed on 8% gels, followed by western blotting using an anti-A1 C5 IgG, as described in “Materials and methods” (a). Band densities of intact A11-372 observed from panel a were measured by quantitative densitometry. Density before the addition of APC was regarded as 100% (b). The plotted data were fitted in an equation of single exponential decay (dashed lines). The symbols used are as follows: open circles, WT; closed circles, W1920R; open squares, R506Q. All experiments were performed at least 3 separate times, and the average values are shown.

APC-catalyzed FVIIIa inactivation is regulated by cleavage at Arg336 in A1.37 Figure 7B illustrates time-dependent cleavage at Arg336 analyzed by western blotting using mAbC5. This mAb recognizes the residues 337 to 372, and the disappearance of this band represents cleavage at Arg336.38 With FV-WT, intact A1 gradually decreased time-dependently (Figure 7Ba). With FV-W1920R, however, cleavage at Arg336 was not observed during a 10-minute reaction time, and the rate of cleavage with FV-R506Q appeared to be ∼40% of that of FV-WT (Figure 7Bb and Table 4), consistent with the results obtained in FXa generation assays. These data confirmed that APC cofactor activity was partially or completely impaired with R506Q and W1920R, respectively.

Discussion

We described a novel FV-W1920R missense mutation associated with APCR in a Japanese boy with serious DVT. The APCR of FVNara was greater than that of FVLeiden and involved a novel mechanism related to a significant inhibition of cleavage at both sites because of the possible failure of direct and/or indirect interactions with APC and/or PS.

FV-W1920 is a highly conserved residue among other mammalians. According to the crystal structure of APC-inactivated bovine FVa,36 bovine-W1907 (corresponding to human-W1920) is located on the internal structure in the C1 domain, which is involved in 3 spike-like structures of β-strand as PL-binding sites. W1907 forms hydrogen bonding with W1891 (W1904) and L2013 (L2026), which is located at the first and second spike of PL-binding, respectively. W1920R may have an effect on the PL binding at the C1 interface and may be an unstable molecule by modification (eg, misfolding). However, because a functional assay such as prothrombinase activity, FXa activation, and a PL-binding assay did not indicate significant differences between WT and W1920R, this molecule would be not significantly disturbed structurally; thereby, the reason for secretion defect is unclear.

Our assays for APC-catalyzed FV cleavage demonstrated little cleavage of W1920R at Arg306, and cleavage at Arg506 was markedly delayed. As discussed earlier, the Arg506 cleavage is considered to be essential for direct and FVIII-related anticoagulant properties of FV,15,16,29 whereas the Arg306 cleavage is associated with FVa inactivation. Mutations at Arg306, including FVCambridge, contribute to mild APCR, and a similar mutation FVHong Kong, appears not to affect the APC response.19-21 We speculate, therefore, that the impairment of APC-catalyzed cleavage at Arg506 in FVNara resulted in persistent levels of FVIIIa:C and FVa:C and was the most influential defect in the APCR mechanism. The complete loss of cleavage at Arg306 in FVNara also contributed to the stability of FVa:C. These findings provide potential new insights into the physiological role or roles of FV in (anti)coagulation systems.

The recurrence of DVT in FVNara was evident despite low levels of plasma FV:C. This observation appears to be unique in FV mutations reported with APCR. The precise reason or reasons for thrombotic symptoms in these circumstances remain to be clarified but could be explained by some laboratory features. First, moderately low levels of plasma FV:C (>5%) promote thrombin generation near to normal plasma and could facilitate significant effects on APCR. The thrombin-related procoagulant capacity of lower levels of FV:C (<2∼3%) is very restricted, however, and the anticoagulant function of FV might be negligible. Second, platelet FV:C might be more important than plasma FV:C in physiological procoagulant activity.39 Platelet FV:C in FVNara was ∼20% (data not shown), and the peak level of thrombin formation in PRP was comparable to that of normal PRP (∼90% of normal). The peak thrombin after the addition of APC was increased (145% of normal) (Figure 2Ab). Third, other hemostasis-related mechanisms may have a potential effect on the thrombotic diathesis. Other laboratory findings were within normal range in our patient, however, and we demonstrated directly that FV-W1920R conferred APCR.

The APCR mechanisms in FVNara appeared to be distinct from other APCR-associated FV mutations. With the exception of FVLiverpool (I359T),40 all FV mutations have been identified in the HCh and constitute point mutations at cleavage sites that lead to the impairment of FV(a) inactivation. Delayed cleavage at Arg306 was described in FVLiverpool, resulting in impaired inactivation of FVa and in clinically severe DVT. This mutation led to the creation of a glycosylation consensus sequence at Asn357 that is slightly remote from the Arg306 site. Cleavage at Arg506 in FVa and APC cofactor activity for FVIIIa inactivation was normal. However, W1920R is significantly remote from the APC-cleavage sites and from moderated cleavage at both Arg306 and Arg506. Although W1920 in FV is close to the PL-binding site,36 the binding ability of W1920R to PL was almost equivalent to that of FV-WT, indicating that W1920R in FVNara might affect the direct association (binding-site) or indirect association (conformational change) with APC. In addition, W1920R was little cleaved by APC at Arg306, depending on PS, which might supporting a defective interaction with PS. Our conclusion that FVNara was resistant to APC inactivation through an impaired interaction with this protease might be further supported by observations that FVa-W1920R, when assembled into prothrombinase, was protected from FXa-catalyzed APC inactivation and that the inhibitory effect of FXa on APC-catalyzed inactivation of FVa-W1920R was observed, similar to WT (data not shown).

FVLeiden is known to be a major cause of hereditary thrombotic diseases among Caucasians.2,41 Studies of the ethnic distribution of FVLeiden indicated that the mutation was not found in Asians.17,18 A different FV mutation (E666D) causing APCR coupled with DVT has been reported in China,42 but there are no reports of FV-associated APCR in Japan. The parents of the current propositus were heterozygous for the W1920R mutation, but they have not developed any thrombotic symptoms to date, although aPTT-based assays demonstrated mild APCR. It is possible that similar to FVLeiden, the heterozygote FVNara may have a potential risk for thrombosis compounded by other prothrombotic factors.

Presented in abstract form at the 53rd annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Diego, CA, December 12, 2011.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Koji Yada, Dr Hiroaki Minami, and Dr Shoko Furukawa for the clinical support.

This work was partly supported by grants from Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) (21591370 and 24591558 to K.N.) and an unrestricted research grant from Baxter (to K.F.).

Authorship

Contribution: K.N. and K.A. designed of research; K.N. and K.S. wrote the manuscript; K.N., K.S., K.O., and T.M. performed experiments; K.N., K.S., and K.O. analyzed the data; and K.F. and M.S. supervised the study, interpreted data, and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: K.S. is an endowed assistant professor funded by Baxter; has given lectures at educational symposiums organized by Baxter, Bayer, and Novo Nordisk; has received payment for lectures from Baxter, Bayer, and Novo Nordisk; and has received the Award from Baxter Coagulation Research Fund in Japan. K.F. and K.A. are professors of additional post in Molecular Genetics of Coagulation Disorder without additional salary. K.A. is a board member of the Factor Eight Inhibitor Bypass Activity Post Marketing Surveillance Study Board in Japan organized by Baxter; has received payment for lectures from Baxter, Bayer, Biogen Idec, Kaketsuken, Novo Nordisk, and Pfizer; has received payment for consultancy meetings with Baxter, Bayer, CSL Behring, Kaketsuken, Novo Nordisk, and Pfizer; and has received unrestricted grants supporting research from Pfizer. K.F. is an investigator of Hemophilia Research Study Update organized by Baxter, a board member of the Advate Safety Board in Japan organized by Baxter, and a board member of the Benefix Post Marketing Surveillance Study Board in Japan, organized by Pfizer; has received payment for consultancy meetings with Baxter, Pfizer, Biogen Idec, Bayer, CSL Behring, Kaketsuken, SRL, Mitsubishi Chemical Medience, and Novo Nordisk; has received unrestricted grants supporting research from Baxter, Pfizer, Bayer, Kaketsuken, Japan Blood Products Organization, and CSL Behring; and has received payment for lectures from Baxter, Bayer, Pfizer, Novo Nordisk, CSL Behring, Roche Diagnostics, Fujirebio Inc, and Sekisui Medical. M.S. is a board member of the Feiba and an Advate Safety Board in Japan, organized by Baxter, and a board member of the Benefix Post Marketing Surveillance Study Board in Japan, organized by Pfizer; has received payment for consultancy meetings with Baxter, Pfizer, Biogen Idec, Bayer, CSL Behring, Kaketsuken, Chugai Therapeutic Company, and Novo Nordisk; has received unrestricted grants supporting research from Baxter, Pfizer, Bayer, Kaketsuken, Novo Nordisk, Chugai Pharmaceutical Company, and CSL Behring; and has received payment for lectures from Baxter, Bayer, Novo Nordisk, and Pfizer. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Keiji Nogami, Department of Pediatrics, Nara Medical University, Kashihara, Nara 634-8522, Japan; e-mail: roc-noga@naramed-u.ac.jp.

References

Author notes

K.N. and K.S. contributed equally to this study.