Key Points

Inhibition of mast cells with cromolyn or imatinib results in reduced systemic inflammation and neurogenic inflammation in sickle mice.

Pharmacological inhibition or genetic depletion of mast cells in sickle mice ameliorates chronic and hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced pain.

Abstract

Sickle cell anemia (SCA) is an inherited disorder associated with severe lifelong pain and significant morbidity. The mechanisms of pain in SCA remain poorly understood. We show that mast cell activation/degranulation contributes to sickle pain pathophysiology by promoting neurogenic inflammation and nociceptor activation via the release of substance P in the skin and dorsal root ganglion. Mast cell inhibition with imatinib ameliorated cytokine release from skin biopsies and led to a correlative decrease in granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and white blood cells in transgenic sickle mice. Targeting mast cells by genetic mutation or pharmacologic inhibition with imatinib ameliorates tonic hyperalgesia and prevents hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced hyperalgesia in sickle mice. Pretreatment with the mast cell stabilizer cromolyn sodium improved analgesia following low doses of morphine that were otherwise ineffective. Mast cell activation therefore underlies sickle pathophysiology leading to inflammation, vascular dysfunction, pain, and requirement for high doses of morphine. Pharmacological targeting of mast cells with imatinib may be a suitable approach to address pain and perhaps treat SCA.

Introduction

Sickle cell anemia (SCA) is one of the world’s most common inherited disorders, characterized by chronic hemolytic anemia and recurrent episodes of vaso-occlusive crisis (VOC) and pain. An autosomal recessive disorder, SCA is caused by substitution of a valine residue for glutamic acid at position 6 in the β-globin chain of hemoglobin.1 Homozygosity for this mutation leads to a severe clinical phenotype in which sickle hemoglobin (Hb) molecules are prone to polymerize under hypoxic conditions to form rigid fibers within red blood cells (RBCs), giving them their characteristic sickle shape. Sickle RBCs cluster together to occlude blood vessels and impair oxygen supply, resulting in VOC characterized by acute pain.2 Although VOC plays an important role in SCA pathophysiology, pain also occurs in the absence of VOC, with many patients experiencing severe nonretractable pain beginning in infancy and continuing throughout life.3 Pain due to VOC is considered more severe than labor pain and has dramatic impacts on morbidity and mortality.4 Hence, sickle patients often require hospitalization and high doses of chronic opioids, creating an increased risk of tolerance and addiction that pose major challenges for pain management.

Although the genetic mechanism of SCA is well defined, the pathophysiology of pain remains poorly understood. It has been hypothesized that the neural response to unrelieved pain may in turn contribute to sickle pathophysiology and further amplify pain.5 Unmyelinated C-fiber nociceptors serve a sensory afferent function to transmit information about noxious (painful) stimulation to the central nervous system (CNS), but also serve an efferent function that causes vasodilatation and plasma extravasation, a phenomenon termed neurogenic inflammation.6 Upon activation of these fibers, action potentials travel orthodromically along the axon to the CNS as well as antidromically to invade endings of their arborizations, leading to the release of the neuropeptides substance P (SP) and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) in the periphery that produce neurogenic inflammation.6 We previously observed increased immunoreactivity (ir) of SP and CGRP in the skin of mice expressing sickle Hb, which was accompanied by hyperalgesia.7

The transmission and perception of pain is modified via neuromodulators released from nonneuronal cells, such as mast cells, and contributes to the generation of hyperalgesia.8,9 Indeed, one mechanism by which C-fiber nociceptors can be excited during inflammation is through tryptase released by mast cell activation/degranulation (termed activation henceforth). Tryptase causes nociceptor excitation by activating protease activated receptor 2 (PAR2).10,11 Mast cells are tissue-resident inflammatory cells that are known for their role in allergic hypersensitivity but have been recently implicated in several immune, vascular, and sensory functions including pain.12-14 Because SP and CGRP play an important role in cutaneous neurogenic inflammation6 via mast cell–dependent mechanisms,15 we hypothesized that mast cell activation and neuropeptide release contribute to the pro-inflammatory milieu and pain in SCA. In the present study, we used transgenic sickle HbSS-BERK mice to investigate the role of mast cell activation and neurogenic inflammation in the pathophysiology of pain in SCA. Because HbSS-BERK mice exhibit inflammation, endothelial activation, and deep as well as cutaneous mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia similar to those reported for patients with SCA,7,16,17 studies performed herein may have the translational potential to develop mast cell–targeted therapies to ameliorate pain in SCA.

Materials and methods

Detailed methods are described in the supplementary file online (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Mice

Transgenic sickle mice (HbSS-BERK) expressing >99% human sickle hemoglobin and littermate controls (HbAA-BERK) expressing normal human hemoglobin were used.7 Sickle mice were backcrossed with WBB6F1-KitW/KitW-v mice (Jackson Labs) with a point mutation in c-kit lacking mast cells to obtain sickle mice lacking mast cells and other congenic controls. All procedures were performed in compliance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Minnesota.

Drug treatment of mice

Mice were treated daily for 5 days with 100 mg/kg body weight cromolyn sodium (CS) (Sigma) or imatinib mesylate (Gleevec; Novartis) via intraperitoneal injection or gavage, respectively. On day 5, mice were treated with a single subcutaneous injection of morphine sulfate (MS) at a dose of 10 mg/kg.

Hypoxia/reoxygenation treatment

Mice were exposed to 3 hours of hypoxia with 8% O2 and 92% N2 followed by reoxygenation for 1 hour in room air.16

Behavioral testing

Animals were tested for deep/musculoskeletal pain, mechanical hyperalgesia, and thermal sensitivity to heat and cold as described.7

Cytokine and neuropeptide release from skin/dorsal root ganglia

Skin punch biopsies (4 mm diameter) and dorsal root ganglia (DRG) were removed and washed in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10 000 units/mL penicillin G sodium, 10 000 units/mL streptomycin sulfate, and 2.5 μg/mL amphotericin B. Tissues were incubated in DMEM plus antibiotics with 2 mM l-glutamine and 10 mM HEPES for indicated times at 37°C in a 5% CO2 chamber. The culture medium was analyzed for cytokines/neuropeptides.

Statistical analyses

Differences between groups of mice were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni test or Student unpaired t test for individual comparisons. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (v 5.0a, GraphPad Prism). A P value of <.05 was considered significant. All data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Results

Mast cell activation occurs in sickle cell anemia

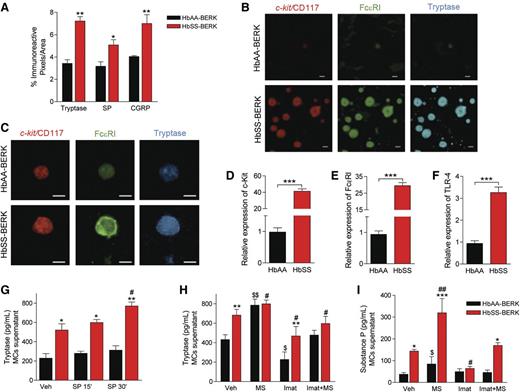

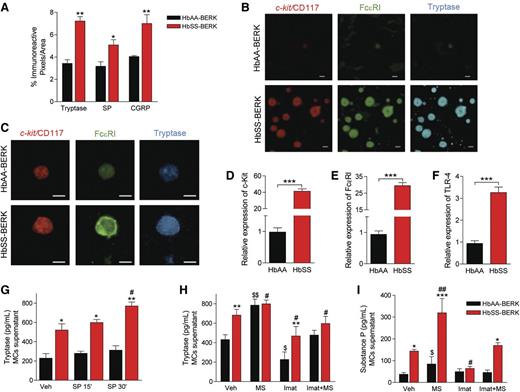

Mast cells release tryptase and SP upon activation.6 Tryptase-, SP-, and CGRP-ir was significantly higher in tissue sections from skin of sickle HbSS-BERK mice than of control HbAA-BERK mice (Figure 1A). Increased cutaneous tryptase colocalized with expression of Fc ε receptor I (FcεRI) and c-kit/CD117, 2 receptors involved in mast cell activation (Figure 1B). Similarly, mast cells isolated from the skin of sickle mice had higher levels of immunoreactive c-kit, FcεRI, and tryptase (Figure 1C) and significantly higher levels of transcripts for c-kit and FcεRI (Figure 1D and E) than control mice. In addition, transcripts for the pattern-recognition receptor toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), which is involved in FcεRI-mediated mast cell activation,18 were >3-fold higher in the mast cells isolated from sickle mouse skin than from control skin (Figure 1F). Cultured mast cells derived from sickle skin continued to release tryptase into cell culture supernatant at higher levels than control cells (Figure 1G). This continued release of tryptase could be due to an autocrine mechanism whereby mast cells release SP upon activation to drive a feed-forward cycle that results in sustained tryptase and SP release.6 Stimulation of mast cells with SP for 30 min led to a significant increase in tryptase in culture supernatant of sickle skin–derived mast cells but not control skin–derived mast cells (Figure 1G). Morphine significantly enhanced tryptase and SP release from cultured mast cells (Figure 1H). In contrast, imatinib mesylate, a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) inhibitor that inhibits c-kit, inhibited the release of tryptase and SP in vehicle- and morphine-treated mast cells (Figure 1H,I). Thus, mast cell activation stimulates a feed-forward cycle of the release of tryptase and SP, which may enhance inflammation, vascular dysfunction, and nociceptor sensitization in SCA.

Mast cell activation occurs in sickle cell anemia. (A) ir pixels for tryptase, SP, and CGRP in the dorsal skin. *P < .05, **P < .01 vs corresponding HbAA-BERK (ANOVA, with Bonferroni). (B) Representative confocal images of dorsal skin sections showing mast cell–specific costaining for c-kit/CD117 (red), FcεRI (green), and tryptase (blue). (C) Skin mast cells in culture stained for c-kit/CD117 (red), FcεRI (green), and tryptase (blue). (D-F) Gene expression of c-kit/CD117 (D), FcεRI (E), and TLR-4 (F) in mast cells derived from skin, measured by reverse-transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR), normalized to GAPDH mRNA, and shown relative to HbAA-BERK, which was given an arbitrary value of 1. ***P < .001 (Student t test). (G) Tryptase levels in the supernatant of skin-derived mast cells after incubation with vehicle (Veh) or SP for indicated time. Black bars, HbAA-BERK; red bars, HbSS-BERK. *P < .05, **P < .01 vs corresponding HbAA-BERK; #P < .05 vs vehicle HbSS-BERK (ANOVA, with Bonferroni). (H-I) Skin-derived mast cells incubated with imatinib mesylate (Imat, 10 μM) and/or morphine sulfate (MS, 1 μM) for 24 hours. Culture medium showing tryptase (H) and SP (I) levels. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001 vs corresponding HbAA-BERK, #P < .05, ##P < .01 vs HbSS-BERK vehicle, $P < .05, $$P < .01 vs HbAA-BERK vehicle (Student t test). Each value is the mean ± SEM of 5 mice of each type, and each image represents images from the skin or skin-derived mast cells from 5 different mice.

Mast cell activation occurs in sickle cell anemia. (A) ir pixels for tryptase, SP, and CGRP in the dorsal skin. *P < .05, **P < .01 vs corresponding HbAA-BERK (ANOVA, with Bonferroni). (B) Representative confocal images of dorsal skin sections showing mast cell–specific costaining for c-kit/CD117 (red), FcεRI (green), and tryptase (blue). (C) Skin mast cells in culture stained for c-kit/CD117 (red), FcεRI (green), and tryptase (blue). (D-F) Gene expression of c-kit/CD117 (D), FcεRI (E), and TLR-4 (F) in mast cells derived from skin, measured by reverse-transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR), normalized to GAPDH mRNA, and shown relative to HbAA-BERK, which was given an arbitrary value of 1. ***P < .001 (Student t test). (G) Tryptase levels in the supernatant of skin-derived mast cells after incubation with vehicle (Veh) or SP for indicated time. Black bars, HbAA-BERK; red bars, HbSS-BERK. *P < .05, **P < .01 vs corresponding HbAA-BERK; #P < .05 vs vehicle HbSS-BERK (ANOVA, with Bonferroni). (H-I) Skin-derived mast cells incubated with imatinib mesylate (Imat, 10 μM) and/or morphine sulfate (MS, 1 μM) for 24 hours. Culture medium showing tryptase (H) and SP (I) levels. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001 vs corresponding HbAA-BERK, #P < .05, ##P < .01 vs HbSS-BERK vehicle, $P < .05, $$P < .01 vs HbAA-BERK vehicle (Student t test). Each value is the mean ± SEM of 5 mice of each type, and each image represents images from the skin or skin-derived mast cells from 5 different mice.

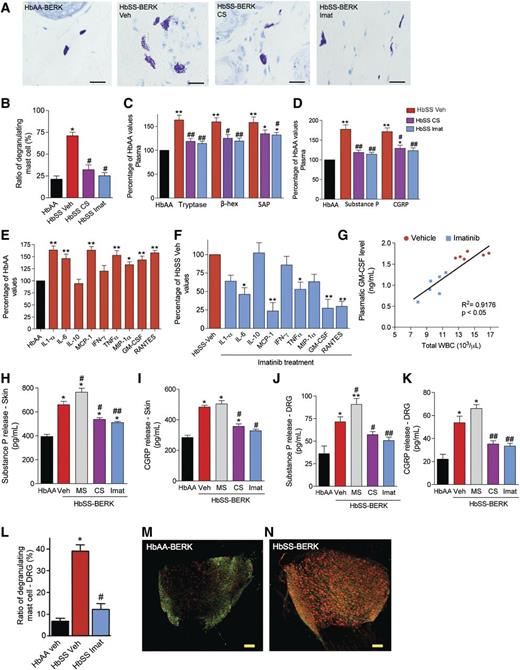

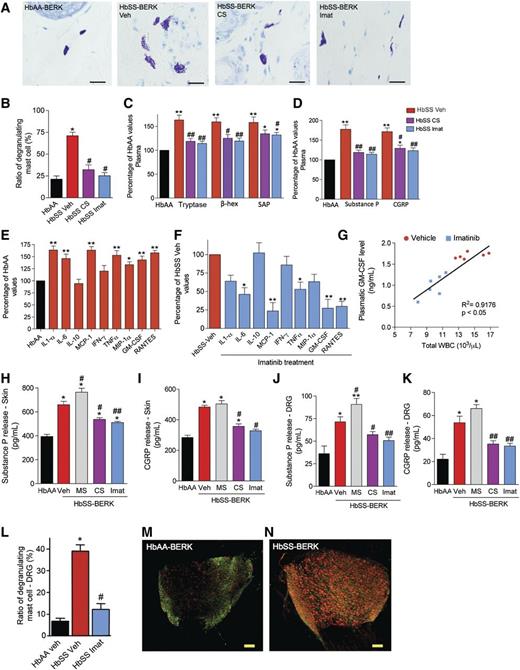

Mast cell activation contributes to inflammation in SCA

We examined if mast cell activation contributes to inflammation by treating sickle and control mice for 5 days with the mast cell stabilizer CS or imatinib. Consistent with their inhibitory effect on mast cell activation (Figure 2A-B), CS and imatinib but not vehicle reduced plasma tryptase, β-hexosaminidase, and serum amyloid protein (SAP), an acute-phase protein, as well as the neuropeptides SP and CGRP in sickle mice (Figure 2C-D). This suggests that mast cell activation contributes to inflammation in sickle mice.

Mast cell activation contributes to neuro-inflammation in SCA. (A-K) HbSS-BERK mice were treated with saline (Veh), CS, or imatinib mesylate (Imat) for 5 days followed by analysis as indicated with each figure. (A) Representative images of Toluidine blue–stained dorsal skin sections. n = 6; bar = 100 μm. (B) Ratio of degranulating/total mast cells. *P < .01 vs HbAA-BERK, #P < .05 vs HbSS-BERK Veh (ANOVA, with Bonferroni). (C-D) Levels of tryptase, β-hexosaminidase (β-hex), SAP, SP, and CGRP expressed as the percentage of HbAA-BERK values. Red bars, HbSS-veh; magenta bars, HbSS-CS; blue bars, HbSS-Imat. *P < .05, **P < .01 vs HbAA-BERK, #P < .05, ##P < .01 vs HbSS-BERK Veh (ANOVA, with Bonferroni). (E-F) Cytokine released following 24 hours of incubation of skin from mice treated with vehicle or imatinib for 5 days. Black bars, HbAA-BERK Veh; red bars, HbSS-BERK Veh; blue bars, HbSS-BERK imatinib. Values are expressed as a percent of HbAA (E) or HbSS veh (F). *P < .05, **P < .01 vs HbAA-BERK Veh (E) or HbSS-BERK Veh (F) (Student t test). (G) Linear regression analysis of the expression of plasma GM-CSF and total WBC counts. (H-K) Neuropeptide release from the skin (H-I) and DRG (J-K) following 24 hours in culture. *P < .05, **P < .01 vs HbAA-BERK (H,J). *P < .05 vs HbSS-BERK Veh, **P < .01 vs HbSS-BERK Veh (I,K) (ANOVA, with Bonferroni). Each value is the mean ± SEM of 6 mice per group (in B-K). (L) Percentage of degranulating mast cells in DRG of mice treated with vehicle or imatinib for 5 days. *P < .001 vs HbAA-BERK Veh, #P < .05 vs HbSS-BERK Veh (ANOVA, with Bonferroni). (M-N) Representative confocal images showing coexpression of ATF3 (green) and GFAP (red). Scale bar, 100 µm; n = 6.

Mast cell activation contributes to neuro-inflammation in SCA. (A-K) HbSS-BERK mice were treated with saline (Veh), CS, or imatinib mesylate (Imat) for 5 days followed by analysis as indicated with each figure. (A) Representative images of Toluidine blue–stained dorsal skin sections. n = 6; bar = 100 μm. (B) Ratio of degranulating/total mast cells. *P < .01 vs HbAA-BERK, #P < .05 vs HbSS-BERK Veh (ANOVA, with Bonferroni). (C-D) Levels of tryptase, β-hexosaminidase (β-hex), SAP, SP, and CGRP expressed as the percentage of HbAA-BERK values. Red bars, HbSS-veh; magenta bars, HbSS-CS; blue bars, HbSS-Imat. *P < .05, **P < .01 vs HbAA-BERK, #P < .05, ##P < .01 vs HbSS-BERK Veh (ANOVA, with Bonferroni). (E-F) Cytokine released following 24 hours of incubation of skin from mice treated with vehicle or imatinib for 5 days. Black bars, HbAA-BERK Veh; red bars, HbSS-BERK Veh; blue bars, HbSS-BERK imatinib. Values are expressed as a percent of HbAA (E) or HbSS veh (F). *P < .05, **P < .01 vs HbAA-BERK Veh (E) or HbSS-BERK Veh (F) (Student t test). (G) Linear regression analysis of the expression of plasma GM-CSF and total WBC counts. (H-K) Neuropeptide release from the skin (H-I) and DRG (J-K) following 24 hours in culture. *P < .05, **P < .01 vs HbAA-BERK (H,J). *P < .05 vs HbSS-BERK Veh, **P < .01 vs HbSS-BERK Veh (I,K) (ANOVA, with Bonferroni). Each value is the mean ± SEM of 6 mice per group (in B-K). (L) Percentage of degranulating mast cells in DRG of mice treated with vehicle or imatinib for 5 days. *P < .001 vs HbAA-BERK Veh, #P < .05 vs HbSS-BERK Veh (ANOVA, with Bonferroni). (M-N) Representative confocal images showing coexpression of ATF3 (green) and GFAP (red). Scale bar, 100 µm; n = 6.

Because nociceptor sensitization occurs in sickle mouse skin,19 mast cell activation may amplify the endogenous release of cytokines and neuropeptides. We analyzed cytokine and neuropeptide release from skin biopsies in organ culture. Skin from sickle mice exhibited enhanced release of several cytokines (interleukin [IL]-1α, IL-6, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-α, macrophage inflammatory protein 1α, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor [GM-CSF], RANTES, etc.) compared with control mouse skin (Figure 2E), and this effect was reduced following pretreatment of mice with imatinib for 5 days (Figure 2F). RANTES and GM-CSF are involved in mast cell recruitment and function,12,20 whereas cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 are implicated in SCA pathophysiology and organ disease.21

GM-CSF plays a critical role in regulating leukocyte counts that are often elevated in SCA.22 HbSS-BERK mice exhibited leukocytosis compared with HbAA-BERK mice (Table 1). We therefore examined whether mast cells influence white blood cell (WBC) counts. Treatment with imatinib for 5 days decreased both plasma GM-CSF and WBC counts (Figure 2G). Moreover, c-kit mutant (lacking mast cells) HbSS-BERK (HbSS-W/Wv) mice displayed WBC counts comparable to those of control HbAA-BERK mice and reduced sickle RBCs (Table 1). Thus mast cell activation triggers an inflammatory response in the sickle milieu.

CS and imatinib treatment also decreased SP and CGRP release from skin and whole DRG compared with vehicle-treated sickle mice (Figure 2H-K). In contrast, morphine enhanced the release of SP from the skin and DRG, supporting the proneuroinflammatory activity of morphine (Figure 2K). Therefore, it is likely that morphine activates the release of SP from mast cells in the skin and DRG.

Mast cells in DRG of sickle mice show elevated activation compared with control mice DRG (Figure 2L). Treatment of sickle mice with imatinib for 5 days led to a significant reduction in mast cell activation in DRG (Figure 2L). Thus, mast cell activation contributes to the increased SP release observed from the DRG of sickle mice. In addition, it is likely that SP from mast cells excites DRG neurons, which in turn release more SP, thus further augmenting SP release from the DRG. Furthermore, the antidromic release of SP from excited neurons and activated mast cells in the DRG may contribute to elevated SP-ir and SP release in the skin of sickle mice. No significant changes were observed in HbAA-BERK mice following CS and imatinib treatment (supplementary Fig. 1A-E).

Activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3)-ir, a marker of neuronal injury, and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-ir, a marker of inflammatory satellite cells in the DRG, were increased in sickle mice compared with control mice (Figure 2M,N; supplementary Figure 5C,D). Increased expression of ATF3 and GFAP is consistent with increased peripheral insult due to inflammation and the accompanying increase in the expression of neuropeptides and tryptase observed in the skin of sickle mice.

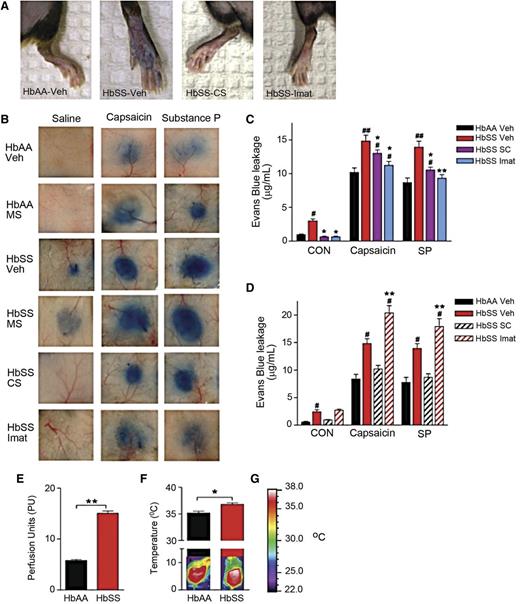

Neurogenic inflammation in SCA

SP and CGRP mediate neurogenic inflammation characterized by increased blood flow and microvascular permeability.6,23 Neurogenic inflammation can occur via mast cell–dependent6 or –independent mechanisms.24 Because mast cells contributed to the increased release of SP and CGRP in sickle mice, we examined whether mast cell–dependent neurogenic inflammation occurred in SCA.

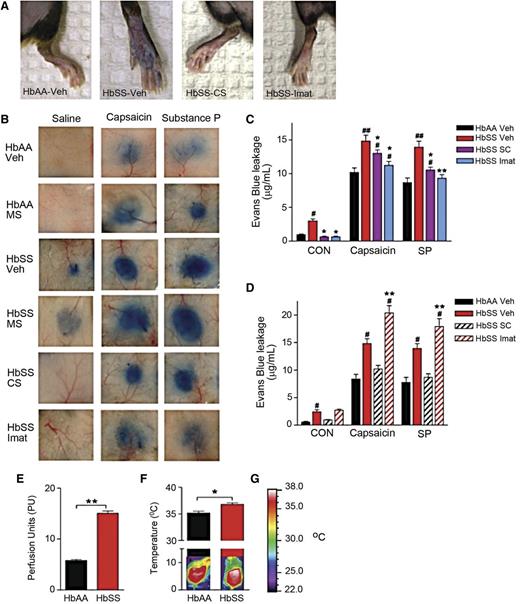

Evans blue leakage, a measure of microvascular permeability, was increased in sickle mice compared with control mice (Figure 3A-C). Also, evoked leakage of Evans blue by intradermal injection of capsaicin (the pungent ingredient in hot chili peppers which activates nociceptive primary afferent nociceptors via transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 channels) or SP was greater in the skin of sickle than control mice (Figure 3B-C). We also observed a correlative increase in cutaneous blood flow and dorsal skin temperature in sickle mice compared with control (Figure 3E-F), further supporting the existence of neurogenic inflammation in SCA. A contribution of mast cells to neurogenic inflammation was demonstrated by a reduction in evoked Evans blue leakage in sickle mice treated with CS or imatinib (Figure 3B-C). In contrast, morphine treatment increased Evans blue leakage compared with vehicle-treated sickle mice in response to capsaicin and SP (Figure 3D). Thus, the observed mast cell activation by morphine above contributes to neurogenic inflammation.

Neurogenic inflammation occurs in SCA. (A-B) Evans blue leakage evoked by injection of saline, capsaicin, or SP in the hind paws (A) and dorsal skin (B) of mice treated with vehicle (saline), morphine sulfate (MS, 10 mg/kg), CS (100 mg/kg), or imatinib (Imat, 100 mg/kg). (C-D) Evans blue leakage. *P < .05, **P < .01 vs HbSS-BERK Veh, #P < .05, ##P < .01 vs HbAA-BERK Veh (ANOVA with Bonferroni). (E) Measures of cutaneous blood flow. **P < .01 (Student t test). (F) Temperature of the dorsal skin of mice with representative thermogram. *P < .05 (Student t test). (G) Calibration bar used.

Neurogenic inflammation occurs in SCA. (A-B) Evans blue leakage evoked by injection of saline, capsaicin, or SP in the hind paws (A) and dorsal skin (B) of mice treated with vehicle (saline), morphine sulfate (MS, 10 mg/kg), CS (100 mg/kg), or imatinib (Imat, 100 mg/kg). (C-D) Evans blue leakage. *P < .05, **P < .01 vs HbSS-BERK Veh, #P < .05, ##P < .01 vs HbAA-BERK Veh (ANOVA with Bonferroni). (E) Measures of cutaneous blood flow. **P < .01 (Student t test). (F) Temperature of the dorsal skin of mice with representative thermogram. *P < .05 (Student t test). (G) Calibration bar used.

To further determine whether mast cell activation contributes to neurogenic inflammation, we treated mice lacking mast cells (W/Wv) and wild-type mice (+/+) with vehicle or lipopolysaccharide, an activator of inflammation, and measured evoked Evans blue leakage. W/Wv mice displayed less Evans blue leakage in response to capsaicin, SP, and saline compared with the wild-type controls (supplementary Figure 4A-B), further demonstrating that mast cells contribute to neurogenic inflammation in SCA.

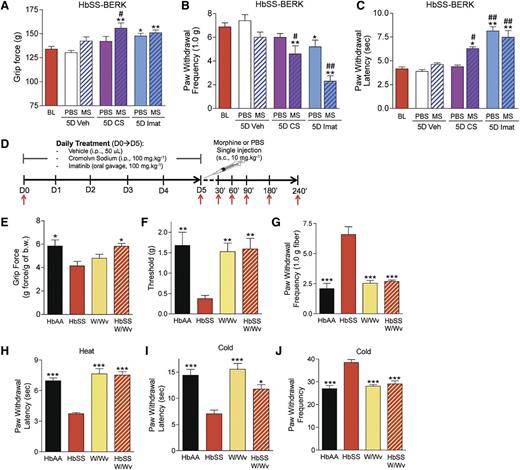

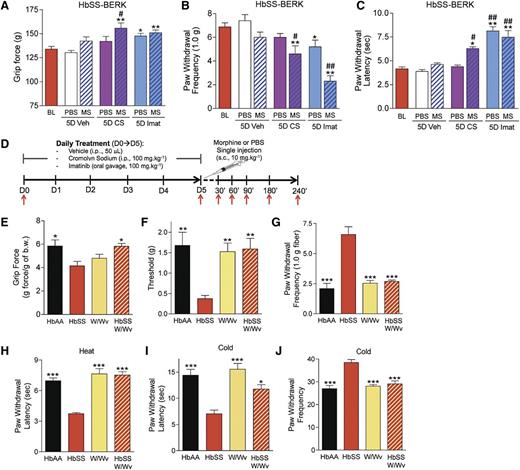

Mast cells contribute to hyperalgesia in SCA

Tryptase released from mast cells interacts with PAR2 on primary afferent nociceptors and contributes to nociceptor sensitization and hyperalgesia.25,26 We therefore examined the contribution of mast cell activation to hyperalgesia and hypoxia reperfusion injury–induced pain by simulating VOC in sickle and control mice. Five days of treatment with imatinib, but not CS, reduced deep-tissue (Figure 4A), mechanical (Figure 4B), and heat (Figure 4C) hyperalgesia in sickle mice. Because morphine activates mast cells27 and also sensitizes the CNS response to subsequent inflammatory insult,28,29 we hypothesized that morphine may contribute to hyperalgesia via mast cell activation while concomitantly acting on the CNS to provide analgesia. Therefore, we examined if mast cell stabilization would improve the analgesic efficacy of 10 mg/kg morphine that is normally ineffective in sickle mice.7 Morphine was effective in reducing hyperalgesia in sickle mice pretreated with CS for 5 days before morphine administration (Figure 4A-C). Importantly, imatinib treatment of 5 days also ameliorated deep and cutaneous hyperalgesia in sickle mice, suggesting that mast cell activation contributes to hyperalgesia in SCA. To verify that the decrease in nocifensive behaviors was not due to a sedative effect of imatinib, mice were tested for motor coordination and balance using the rotarod test. Motor performance of sickle mice treated with imatinib was not impaired and actually improved over time (P < .01 vs baseline) (supplementary Figure 2E). Thus, inhibition of mast cells ameliorated hyperalgesia in sickle mice most likely owing to the decrease in release of cytokines and tryptase that sensitize nociceptors.

Mast cells contribute to hyperalgesia in SCA. (A-D) HbSS-BERK mice were treated with vehicle (Veh), CS, or imatinib (Imat). On day 5, measures of pain were recorded 30 min after the injection of morphine (MS) or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) as shown in (D). Measures of deep pain (A), mechanical hyperalgesia (B), and thermal sensitivity (C) are shown. BL, baseline obtained before the treatments. *P < .05, **P < .01 versus BL (ANOVA, with Bonferroni). #P < .05, ##P < .01 vs PBS for each corresponding treatment (Student t test). Each value is the mean ± SEM from 8 mice with 3 observations per mouse. (D) Treatment protocol. HbAA-BERK and HbSS-BERK mice were treated with saline, CS, or imatinib sulfate for 5 days. At day 5, a single injection of morphine sulfate or PBS was given and pain behaviors were followed for 240 min. i.p., intraperitoneal; s.c., subcutaneous; red arrow, pain testing. (E-J) Pain-related behaviors of age-matched HbAA BERK, HbSS-BERK, KitW/Wv (W/Wv), and HbSS-KitW/Wv (HbSS-W/Wv) mice. Each value is the mean ± SEM from 4-6 mice with 3 observations per mouse. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001 vs HbSS-BERK (ANOVA, with Bonferroni).

Mast cells contribute to hyperalgesia in SCA. (A-D) HbSS-BERK mice were treated with vehicle (Veh), CS, or imatinib (Imat). On day 5, measures of pain were recorded 30 min after the injection of morphine (MS) or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) as shown in (D). Measures of deep pain (A), mechanical hyperalgesia (B), and thermal sensitivity (C) are shown. BL, baseline obtained before the treatments. *P < .05, **P < .01 versus BL (ANOVA, with Bonferroni). #P < .05, ##P < .01 vs PBS for each corresponding treatment (Student t test). Each value is the mean ± SEM from 8 mice with 3 observations per mouse. (D) Treatment protocol. HbAA-BERK and HbSS-BERK mice were treated with saline, CS, or imatinib sulfate for 5 days. At day 5, a single injection of morphine sulfate or PBS was given and pain behaviors were followed for 240 min. i.p., intraperitoneal; s.c., subcutaneous; red arrow, pain testing. (E-J) Pain-related behaviors of age-matched HbAA BERK, HbSS-BERK, KitW/Wv (W/Wv), and HbSS-KitW/Wv (HbSS-W/Wv) mice. Each value is the mean ± SEM from 4-6 mice with 3 observations per mouse. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001 vs HbSS-BERK (ANOVA, with Bonferroni).

To confirm the contribution of mast cells in hyperalgesia, we examined nocifensive behaviors in mast cell–lacking sickle mice (HbSS-W/Wv). In contrast to sickle mice (HbSS-BERK), deep-tissue and cutaneous hyperalgesia did not develop in mast cell–lacking sickle mice (Figure 4E-J). All nocifensive behavioral responses in the latter mice were similar to those of control (HbAA-BERK) or mast cell–lacking (W/Wv) non-sickle mice. Together, these data support the contribution of mast cells to hyperalgesia in sickle mice.

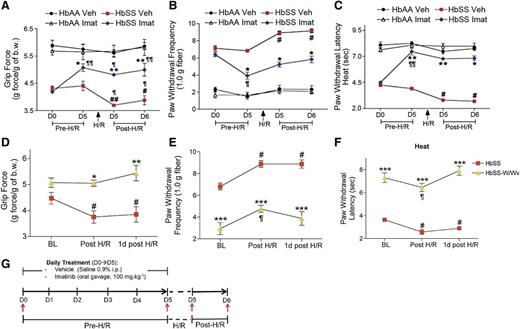

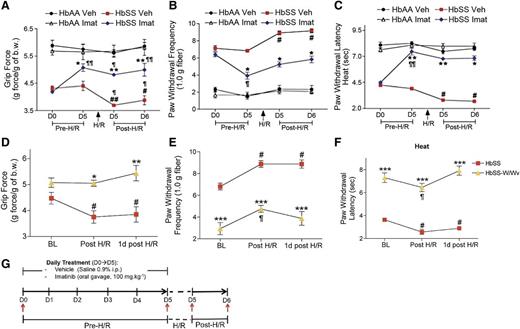

We next examined if mast cells contribute to hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced hyperalgesia in sickle mice. Treatment with imatinib for 5 days before inciting hypoxia/reoxygenation reduced deep-tissue and cutaneous hyperalgesia in sickle mice (Figure 5A-C). Furthermore, the hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced hyperalgesia in sickle mice did not occur in mast cell–lacking sickle (HbSS-W/Wv) mice (Figure 5D-F). The effects of imatinib treatment and mast cell deficiency on reducing hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced hyperalgesia lasted for at least 24 hours (last period of observation). Thus, pharmacological and molecular targeting of mast cells ameliorates hyperalgesia evoked by hypoxia/reoxygenation.

Mast cell activation contributes to hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced pain in SCA. (A-C) HbAA- and HbSS-BERK mice were treated with saline (Veh) or imatinib (imat) for 5 days. All mice were then treated with 3 hours hypoxia and 1 hour reoxygenation (H/R). Pain measures were obtained before starting the drug treatments on day 0 (D0), at the conclusion of drug treatments, D5 before inciting H/R, immediately after H/R, and 24 hours after H/R as indicated by red arrows in the schema in (G). Measures of deep pain (A), mechanical hyperalgesia (B), and thermal sensitivity (C) are shown. ¶P < .05, ¶¶P < .001 versus D0 of matched treatment; #P < .05, ##P < .001 vs D5 pre-H/R of matched treatment; *P < .05, **P < .01 versus HbSS Veh (ANOVA, with Bonferroni). Each value is the mean ± SEM from 6 mice with 3 observations per mouse. (D-F) Pain-related behaviors from age-matched HbSS-BERK and HbSS-KitW/Wv (HbSS-W/Wv) mice before (baseline, BL), immediately after (Post H/R), and 1 day post-H/R. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001 vs HbSS-BERK of matched pain-testing time point; #P < .05 vs HbSS-BERK BL; ¶P < .05 vs HbSS-W/Wv BL (Student t test). Each value is the mean ± SEM of 5 mice.

Mast cell activation contributes to hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced pain in SCA. (A-C) HbAA- and HbSS-BERK mice were treated with saline (Veh) or imatinib (imat) for 5 days. All mice were then treated with 3 hours hypoxia and 1 hour reoxygenation (H/R). Pain measures were obtained before starting the drug treatments on day 0 (D0), at the conclusion of drug treatments, D5 before inciting H/R, immediately after H/R, and 24 hours after H/R as indicated by red arrows in the schema in (G). Measures of deep pain (A), mechanical hyperalgesia (B), and thermal sensitivity (C) are shown. ¶P < .05, ¶¶P < .001 versus D0 of matched treatment; #P < .05, ##P < .001 vs D5 pre-H/R of matched treatment; *P < .05, **P < .01 versus HbSS Veh (ANOVA, with Bonferroni). Each value is the mean ± SEM from 6 mice with 3 observations per mouse. (D-F) Pain-related behaviors from age-matched HbSS-BERK and HbSS-KitW/Wv (HbSS-W/Wv) mice before (baseline, BL), immediately after (Post H/R), and 1 day post-H/R. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001 vs HbSS-BERK of matched pain-testing time point; #P < .05 vs HbSS-BERK BL; ¶P < .05 vs HbSS-W/Wv BL (Student t test). Each value is the mean ± SEM of 5 mice.

Discussion

SCA is characterized by inflammation, vascular dysfunction, and pain,3,21 which pose major therapeutic challenges due to a poor understanding of the mechanisms that underlie sickle pathophysiology. We show that mast cell activation contributes to sickle pathophysiology by mediating inflammation, pain, and reduced responsiveness to morphine, all hallmarks of SCA. Inflammatory cytokines and neuropeptides released from mast cells in the periphery orchestrate neurogenic inflammation, a previously undocumented phenomenon, and resultant hyperalgesia in SCA. Inhibition of mast cells with the c-kit/tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib or deletion of mast cells ameliorated hyperalgesia in sickle mice, whereas the mast cell stabilizer CS improved the analgesic responsiveness to relatively low doses of morphine, which are otherwise ineffective. Importantly, imatinib or mast cell absence provides a protective response in hypoxia/reoxygenation-evoked pain. Complementary to our observation of mast cell–dependent inflammatory, vascular, and nociceptive insult in sickle mice, imatinib treatment completely prevented VOC and hospitalization of a patient with a history of recurrent VOCs before initiation of imatinib treatment given for concurrent chronic myeloid leukemia.30 Discontinuation of imatinib led to the recurrence of VOC in this patient, suggestive of a protective role of imatinib. In another report, tryptase levels in the blood were significantly elevated in conjunction with sickle crisis–type pain and acute chest syndrome following a fatal overdose of fentanyl in a patient with sickle cell/β-thalassemia.31 Elevation of tryptase was suggested to be associated with opioid-induced acute anaphylaxis, but its significance in sickle pathophysiology leading to death remained unclear. No other data exist on the involvement of mast cells in SCA. Therefore, our findings on mast cell–dependent neurogenic inflammation and hyperalgesia and morphine-induced mast cell activation strongly argue in favor of a critical role for mast cell activity in SCA, as well as the potential for development of mast cell–targeted pharmaceuticals to treat SCA.

In SCA patients, the proliferation of primitive hematopoietic progenitors from the bone marrow is increased, and a larger number of progenitors are mobilized into the peripheral blood.32 During VOC, there is a further increase in circulating myeloid cells and stem cell factor and GM-CSF.33 Because circulating bone marrow–derived precursor cells differentiate into mast cells and proliferate in response to suitable stimuli,14 endothelial activation and inflammation in SCA replete with stem cell factor, GM-CSF, and other cytokines may promote mast cell differentiation, proliferation, survival, and activation, following the homing of mobilized progenitors to tissues. We speculate that these phenomena may contribute to our observation of increased numbers and activation of mast cells in sickle mice. Once large numbers of mast cells are generated, their activation further augments inflammation by release of cytokines, promoting a feed-forward cycle of mast cell activation and inflammation. Of note, imatinib treatment led to a decrease in mast cell activation and correlative decrease in WBC counts and GM-CSF, suggesting that mast cells play a causative role in the inflammatory process in SCA. This notion is further supported by the observation that imatinib treatment completely prevented the incidence of VOC in a sickle patient with recurrent frequent VOCs before treatment.30

Mast cells contribute to inflammation by multiple mechanisms. Mast cells are known to release inflammatory mediators and proteases, including tryptase, upon activation in response to physiological and chemical stimuli.14 Proinflammatory cytokines, including TNFα, released from mast cells alter the functions and phenotype of other inflammatory cells34 and contribute to heightened inflammation observed in SCA. In addition, SP and CGRP can interact with diverse immune and inflammatory cells, including mast cells,6,35 to cause activation.36 Increased expression of FcεRI and TLR4 on the mast cells of sickle mice leads to mast cell activation and subsequent elevated levels of acute-phase protein SAP in the plasma and cytokine release from the skin. Mast cell activation also occurs in response to ischemia reperfusion injury,37 influencing leukocyte adhesion and transmigration. Ischemia reperfusion injury occurs in SCA, resulting in elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines and endothelial activation.21 Considering the close proximity of mast cells to the vasculature, endothelial perturbation may contribute to mast cell activation in its vicinity. Nitric oxide (NO) inhibits FcεRI-dependent cytokine release from mast cells,38,39 but due to impairment of NO bioavailability in SCA,40 mast cell activation may remain unregulated. Thus, the sickle microenvironment favors persistent endogenous mast cell activation, which may pose a major challenge to conventional anti-inflammatory therapies.

Inflammation, vascular dysfunction, and pain in SCA are suggestive of neurogenic inflammation, but it was never examined in previous studies. However, serum levels of SP were shown to be elevated in 2- to 18-year-old SCA patients compared with healthy age-matched controls and rose further during painful crises.41 Elevated serum SP levels and SP-ir in the skin concomitant to increased release of SP from skin biopsies and DRG in sickle mice complement the study on SCA patients, demonstrating a critical role of SP in pain pathophysiology in SCA. Other factors, including prostaglandins, nerve growth factor, interleukins, free radicals, and proteases such as tryptase, released from mast cells contribute to nociceptor sensitization and are elevated in SCA.30,40,42 Nociceptor sensitization in sickle mice19 and thermal hyperalgesia in patients with SCA17 have been demonstrated and are consistent with the elevation of these factors. Furthermore, elevated levels of serum SP in patients with SCA41 and increased expression of neuropeptides in sickle mice further support the hypothesis of ongoing nociceptor activation and neurogenic inflammation in SCA. Importantly, we found that imatinib inhibited serum SP or that released from skin and neurogenic inflammation with a concomitant decrease in hyperalgesia. Therefore, serum SP or that released by skin biopsies may serve as a biomarker for pain and to test the efficacy of therapeutic agents that will ameliorate sickle pathophysiology and pain.

Pain in SCA may be due to cytokines released from mast cells, such as TNF-α, that sensitize nociceptors.13,43 Elevated levels of TNF-α were found in sickle mice21 and are consistent with our observations that sickle BERK mice exhibit hyperalgesia, which is exaggerated by hypoxia/reoxygenation.7 Hypoxia/reoxygenation stimulates VOC in sickle mice, which further exaggerates hyperalgesia.16 Abnormal activity in DRG neurons may also contribute to pain associated with neurogenic inflammation in SCA. Increased expression of ATF3, a marker for neuronal injury,44 and GFAP, a marker for glial and other satellite cells,45 in the DRG of sickle mice suggests that neuronal and glial activation occurs. ATF3 degranulates mast cells,46 and because activated mast cells are found in the DRG of sickle mice, it is conceivable that activation of mast cells in DRG excites small-diameter DRG neurons that release SP and CGRP in the skin by antidromic activity, thus contributing to neurogenic inflammation.

Leukocytosis is frequently observed in SCA,47 and neurogenic inflammation likely contributes to leukocyte migration by altering vascular physiology. Plasma levels of GM-CSF are elevated in SCA patients and correlate with the number of total leukocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, and monocytes.22 Our finding that imatinib decreased GM-CSF level and WBC counts has important implications for improving VOC and has been observed clinically.30 It appears that imatinib has a disease-modifying effect in SCA that prevents VOC and the accompanying pain.

In addition to promoting inflammation and neurogenic inflammation, mast cell tryptase activates PAR2 on peripheral nerve endings and promotes nociception.34,48 Mast cell activation contributes to postoperative pain, which is reduced if treated with mast cell stabilizers preoperatively but not postoperatively,48 suggesting a preventive effect on pain. Similarly, we found that pretreatment with imatinib had a preventive effect on hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced nociception in sickle mice. Thus mast cells play a causative role in the development of hyperalgesia and their inhibition may attenuate pain during VOC and prevent chronic pain.

Currently, high doses of narcotics are required to treat pain in SCA.3 This could be due to morphine-induced SP release from skin and DRG, the occurrence of neurogenic inflammation as seen in in sickle mice, and mast cell activation.27 We propose that morphine concomitantly stimulates mast cell activation–mediated hyperalgesia and analgesia via CNS mechanisms. This proposition is supported by our observations that mast cell stabilizer CS increased the analgesic effectiveness of low-dose morphine, which is otherwise ineffective in ameliorating hyperalgesia in sickle mice.7 Morphine is known to promote TLR4 signaling in the glial cells,29 while repeated exposure to morphine leads to mechanical allodynia produced by inflammation in mice.28 Increased expression of TLR4 on mast cells in SCA may promote morphine-induced activation. Therefore, cotreatment with a mast cell stabilizer or a TLR4 receptor antagonist may improve morphine analgesia in SCA while reducing the inflammation induced by morphine. Imatinib was shown to eliminate tolerance to morphine in rats.49 Because CS and imatinib are US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs, these observations have a translational potential to effectively treat pain in SCA following appropriate clinical trials.

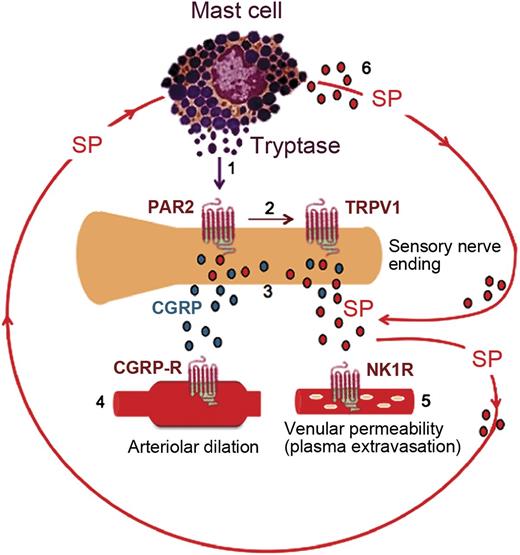

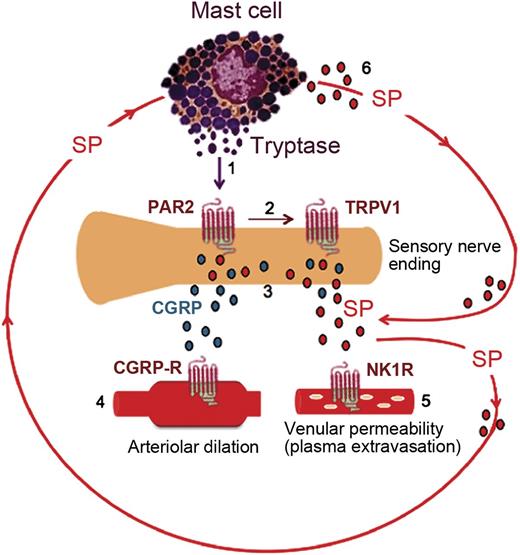

In summary, this is the first description of mast cell activation and its contribution to hyperalgesia in SCA. We posit that mast cell tryptase activates nociceptors via PAR2, resulting in increased release of neuropeptides leading to neurogenic inflammation and hyperalgesia (Figure 6). Reduced hyperalgesia in sickle mice lacking mast cells supports the conclusion that mast cells are part of a persistent feed-forward cycle of neurogenic inflammation and pain in sickle mice (Figure 6). Therefore, treatments aimed at reducing mast cell activity may reduce the pathophysiological consequences of SCA and potentiate the therapeutic efficacy of opioid analgesics.

Activated mast cells contribute to a feed-forward cycle of neuropeptide release in the skin of sickle mice. (1) Tryptase from mast cells activates PAR2 on the peripheral nerve endings. (2) Activation of PAR2 sensitizes transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1). (3) Excited nociceptors stimulate the release of CGRP and SP from the sensory nerve endings. (4) CGRP interacts with the type 1 CGRP receptor on arterioles to induce dilatation. (5) Substance P activates plasma extravasation via neurokinin 1 (NK1) receptors. (6) SP released from nerve endings as well as from mast cells also acts on the mast cells themselves, thus promoting a vicious cycle of mast cell activation.

Activated mast cells contribute to a feed-forward cycle of neuropeptide release in the skin of sickle mice. (1) Tryptase from mast cells activates PAR2 on the peripheral nerve endings. (2) Activation of PAR2 sensitizes transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1). (3) Excited nociceptors stimulate the release of CGRP and SP from the sensory nerve endings. (4) CGRP interacts with the type 1 CGRP receptor on arterioles to induce dilatation. (5) Substance P activates plasma extravasation via neurokinin 1 (NK1) receptors. (6) SP released from nerve endings as well as from mast cells also acts on the mast cells themselves, thus promoting a vicious cycle of mast cell activation.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs David Wood and Celalettin Ustun for the critical review of the manuscript; Bola Taiwo for suggestions; Stefan Kren, Katherine N. H. Johnson, and Sugandha Rajput for breeding, genotyping, and phenotyping mice and/or technical assistance; Drs Robert P. Hebbel and David Archer for providing breeder sickle mice; Drs David Largaespada and Anindya Bagchi for advice on mouse genetics; Dr Jatinder Lamba for RT-qPCR facilities and advice; Dr Hemant Kumar for RT-qPCR; and Michael J. Franklin and Carol Taubert for editorial assistance.

This work was supported by NIH grants HL68802 and 103773 to KG.

Authorship

Contribution: L.V. performed experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; D.V., pain-testing and analysis; K.L. and J.N., isolation and culture of mast cells, immunofluorescent staining, and confocal microscopy; M.G., interpretation of data and manuscript writing/editing; M.E.E., confocal microscopy; D.A.S., advice and editing the manuscript; and K.G. conceived, designed, planned, and supervised the entire study, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote/edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Kalpna Gupta, Vascular Biology Center, Medicine—Hematology, Oncology and Transplantation, University of Minnesota, Mayo Mail Code 480; 420 Delaware St SE, Minneapolis, MN, 55455; e-mail: gupta014@umn.edu.