Abstract

Hematologic malignancies are typically associated with leukemogenic fusion proteins, which are required to maintain the oncogenic state. Previous studies have shown that certain oncogenes that promote solid tumors, such as RAS and BRAF, can induce senescence in primary cells, which is thought to provide a barrier to tumorigenesis. In these cases, the activated oncogene elicits a DNA damage response (DDR), which is essential for the senescence program. Here we show that 3 leukemogenic fusion proteins, BCR-ABL, CBFB-MYH11, and RUNX1-ETO, can induce senescence in primary fibroblasts and hematopoietic progenitors. Unexpectedly, we find that senescence induction by BCR-ABL and CBFB-MYH11 occurs through a DDR-independent pathway, whereas RUNX1-ETO induces senescence in a DDR-dependent manner. All 3 fusion proteins activate the p38 MAPK pathway, which is required for senescence induction. Our results reveal diverse pathways for oncogene-induced senescence and further suggest that leukemias harbor genetic or epigenetic alterations that inactivate senescence induction genes.

Introduction

Oncogene-induced senescence and apoptosis are thought to play important roles in suppressing tumorigenesis by preventing proliferation of cells at risk for neoplastic transformation.1,2 Several studies have demonstrated a functional linkage between oncogene-induced senescence and activation of the DNA damage response (DDR).3-5

Oncogene-induced senescence and apoptosis have been primarily studied in the context of solid tumors and not hematopoietic malignancies, which often result from leukemogenic fusion proteins.6 Here we study the ability of 3 leukemogenic fusion proteins, BCR-ABL, CBFB-MYH11, and RUNX1-ETO (also known as AML1-ETO), to induce senescence in primary fibroblasts and hematopoietic progenitors.

Methods

Retroviral transduction

Retroviral constructs pMSCV-BCR-ABL-IRES-GFP (Warren Pear, University of Pennsylvania), pMSCV-IRES-GFP, pMSCV-CBFB-MYH11-IRES-GFP, or pMSCV-RUNX1-ETO-IRES-GFP (all provided by Lucio Castilla, University of Massachusetts Medical School), were cotransfected into 293-gag-pol cells with the packaging vector. IMR90 fibroblasts (ATCC) or bone marrow cells isolated as previously described7 were transduced at multiplicity of infection = 20 and green fluorescent protein–positive cells were isolated 2 days later and used for all subsequent experiments. A retrovirus expressing pBABE-puro-H-RAS V12 (William Hahn, Harvard University) was generated as described in this section, and HRAS V12-expressing cells were puromycin-selected for 3 days.

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase assays

Cells were stained for β-galactosidase activity as described8 and visualized on a Zeiss Axiovert 40 CFL microscope (Carl Zeiss). Images were captured using QCapture Pro, Version 5 software (QImaging Corporation).

Immunoblot analysis

Extracts were prepared by lysis in Laemmli buffer with or without a phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). Blots were probed with β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich), acetyl-H3K9 (Millipore), p16, phospho-ATM (Ser1981), ATM, phospho-p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182), or p38 MAPK (Cell Signaling) antibodies. SB203580 (Invitrogen) was used at 5μM.

DNA replication assays

Cells were incubated with 20μM bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU; Sigma-Aldrich) for 4 hours and stained as described.9 For ATM knockdown, cells stably expressing a nonsilencing or ATM shRNA (Open Biosystems; Oligo IDs V2HS-89368 and V2HS-192880) or ATM siRNA (5′-UGAUCUGCUCAUUUGCUGC-3′ and 5′-AGAAGUGGAUAAAUUUAAG-3′) were transduced and analyzed for BrdU incorporation.

Immunofluorescence assays

γ-H2AX immunofluorescence was performed as per the supplier's recommendations (Millipore). For quantitation, 100 cells (in triplicate) were visualized and scored positive if they contained more than 10 γ-H2AX foci. For the comet assay, cells were trypsinized and prepared as described,10 analyzed in alkaline conditions, and visualized using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope. Comet length was measured in 100 cells (in triplicate).

Results and discussion

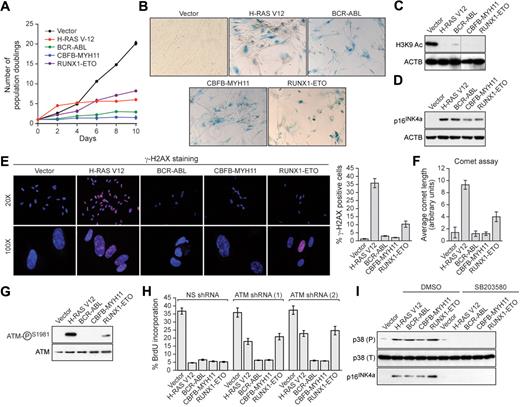

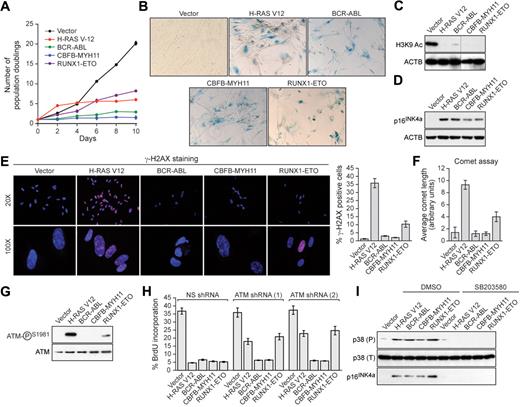

Human primary IMR90 fibroblasts were transduced with a retrovirus encoding BCR-ABL, CBFB-MYH11, or RUNX1-ETO, or as a control an activated RAS mutant (H-RAS V12). Cells expressing H-RAS V12, BCR-ABL, CBFB-MYH11, or RUNX1-ETO exhibited decreased cellular proliferation (Figure 1A) and displayed 2 well-characterized senescence markers8,11 : positive staining for senescence-associated β-galactosidase (Figure 1B) and loss of histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9) acetylation (Figure 1C). Furthermore, expression of BCR-ABL, CBFB-MYH11, or RUNX1-ETO increased the percentage of cells in G1 and substantially decreased DNA replication, indicative of G1 arrest (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Finally, expression of H-RAS V12, BCR-ABL, CBFB-MYH11, or RUNX1-ETO induced expression of the cell cycle inhibitor p16INK4a (Figure 1D). Collectively, these results demonstrate that leukemogenic fusion proteins induce senescence in primary fibroblasts.

Leukemogenic fusion proteins induce senescence in human primary fibroblasts. (A) IMR90 cells expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein were monitored for proliferation by trypan blue viability assay. Error bars represent SEM. Quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction confirmed that the expression level of each oncogene was comparable (supplemental Figure 5). (B) IMR90 cells expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein were stained for senescence-associated β-galactosidase. (C) Immunoblot analysis monitoring H3K9 acetylation (H3K9 Ac) in IMR90 cells expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein. β-Actin (ACTB) was monitored as a loading control. (D) Immunoblot analysis monitoring p16INK4a levels in IMR90 cells expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein. (E) IMR90 cells expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein were stained for γ-H2AX and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. (Right) Quantification of γ-H2AX staining. Cells with more than 10 γ-H2AX foci were included in the analysis. Error bars represent SEM. (F) IMR90 cells expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein were analyzed by comet assay under alkali conditions, and comet tail length was quantified. Error bars represent SEM. (G) Immunoblot analysis monitoring levels of phospho-ATM and, as a control, total ATM in IMR90 cells expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein. (H) BrdU incorporation assay in IMR90 cells stably expressing either a nonsilencing (NS) shRNA or one of 2 unrelated shRNAs directed against ATM, and expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein. Error bars represent SEM. (I) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylated p39 (P), total p38 (T), and p16INK4a levels in IMR90 cells expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580.

Leukemogenic fusion proteins induce senescence in human primary fibroblasts. (A) IMR90 cells expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein were monitored for proliferation by trypan blue viability assay. Error bars represent SEM. Quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction confirmed that the expression level of each oncogene was comparable (supplemental Figure 5). (B) IMR90 cells expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein were stained for senescence-associated β-galactosidase. (C) Immunoblot analysis monitoring H3K9 acetylation (H3K9 Ac) in IMR90 cells expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein. β-Actin (ACTB) was monitored as a loading control. (D) Immunoblot analysis monitoring p16INK4a levels in IMR90 cells expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein. (E) IMR90 cells expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein were stained for γ-H2AX and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. (Right) Quantification of γ-H2AX staining. Cells with more than 10 γ-H2AX foci were included in the analysis. Error bars represent SEM. (F) IMR90 cells expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein were analyzed by comet assay under alkali conditions, and comet tail length was quantified. Error bars represent SEM. (G) Immunoblot analysis monitoring levels of phospho-ATM and, as a control, total ATM in IMR90 cells expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein. (H) BrdU incorporation assay in IMR90 cells stably expressing either a nonsilencing (NS) shRNA or one of 2 unrelated shRNAs directed against ATM, and expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein. Error bars represent SEM. (I) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylated p39 (P), total p38 (T), and p16INK4a levels in IMR90 cells expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580.

To investigate whether leukemogenic fusion proteins induced senescence through a DDR-mediated pathway, we first analyzed cells for the formation of phosphorylated H2AX (γ-H2AX) foci, a marker of double-strand DNA breaks.12,13 As expected, expression of activated RAS elicited a large number of γ-H2AX foci; by contrast, BCR-ABL or CBFB-MYH11 did not induce γ-H2AX foci, whereas RUNX1-ETO modestly induced γ-H2AX foci (Figure 1E). Second, we performed comet assays, which can detect both single- and double-strand DNA breaks.10 Cells expressing BCR-ABL or CBFB-MYH11 displayed a round, well-defined DNA staining contained within the nucleus that was indistinguishable from control cells (supplemental Figure 2; quantified in Figure 1F). By contrast, H-RAS V12-expressing cells displayed a large comet-like tail, indicative of significant DNA damage, whereas RUNX1-ETO-expressing cells displayed a small tail, indicative of modest DNA damage. Third, we found that phosphorylation of the ATM kinase, which occurs after DNA damage,14 was not detectable in cells expressing BCR-ABL or CBFB-MYH11, whereas cells expressing RUNX1-ETO contained modest levels of phospho-ATM (Figure 1G). Consistent with these results, RNA interference experiments demonstrated that ATM, an essential component of the DDR,14-16 was required for senescence induction by H-RAS V12 and RUNX1-ETO but not by BCR-ABL or CBFB-MYH11 (Figure 1H). Collectively, these results indicate that senescence induction by RUNX1-ETO involves the canonical ATM-dependent DDR, whereas senescence induction by BCR-ABL and CBFB-MYH11 is DDR-independent.

Recent studies have implicated the p38 MAPK/p27/Rb pathway in senescence induction.17 Figure 1I shows that H-RAS V12 or any of the 3 leukemogenic fusion proteins induced expression of p38 MAPK. Treatment of cells with the selective p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 prevented induction of p38 MAPK as well as p16INK4a.

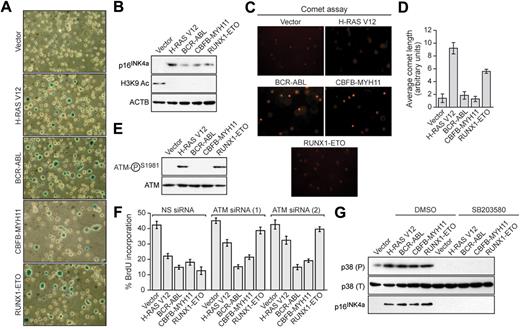

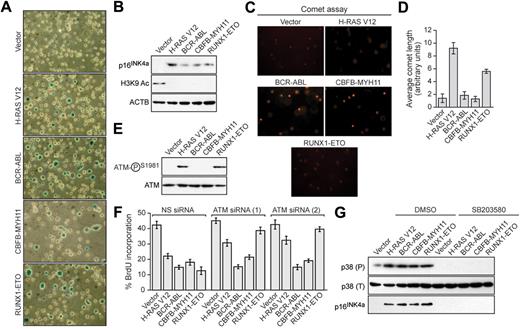

We next asked whether the leukemogenic fusion proteins would induce senescence in hematopoietic progenitors. Bone marrow cells enriched for hematopoietic progenitors were harvested from 5-fluorouracil-treated mice, transduced with a retrovirus expressing H-RAS V12 or a leukemogenic fusion protein, and analyzed for senescence. Hematopoietic cells expressing H-RAS V12 or any of the 3 leukemogenic fusion proteins stained positively for senescence-associated β-galactosidase (Figure 2A) and displayed induction of p16INK4a and loss of H3K9 acetylation (Figure 2B). Comet assays showed that expression of BCR-ABL or CBFB-MYH11 did not result in any detectable DNA damage, whereas expression of H-RAS V12 or RUNX1-ETO induced DNA damage (Figure 2C; quantified in Figure 2D). Similarly, phospho-ATM was not detectable in BCR-ABL- or CBFB-MYH11-expressing cells but was detectable in cells expressing H-RAS V12 or RUNX1-ETO (Figure 2E). Accordingly, ATM was required for senescence induction by H-RAS V12 and RUNX1-ETO but not by BCR-ABL or CBFB-MYH11 (Figure 2F; supplemental Figure 3). All 3 leukemogenic fusion proteins stimulated expression of p38 MAPK, which was required for p16INK4a induction (Figure 2G). Thus, as in fibroblasts, senescence induction in hematopoietic progenitors by RUNX1-ETO involves the DDR, whereas senescence induction by BCR-ABL and CBFB-MYH11 is DDR independent.

Leukemogenic fusion proteins induce senescence in hematopoietic progenitors. (A) Bone marrow cells were isolated from 5-fluorouracil-treated mice, transduced with a retrovirus expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein, and stained for senescence-associated β-galactosidase. (B) Immunoblot analysis monitoring levels of p16INK4a and H3K9 Ac in hematopoietic cells expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein. (C) Hematopoietic cells expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein were analyzed by comet assay under alkali conditions. (D) Quantification of comet tail length. Error bars represent SEM. (E) Immunoblot analysis monitoring levels of phospho-ATM and, as a control, total ATM in hematopoietic cells expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein. (F) BrdU incorporation assay in hematopoietic cells stably expressing either a nonsilencing (NS) siRNA or one of 2 unrelated siRNAs directed against ATM, and expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein. Error bars represent SEM. (G) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylated p39 (P), total p38 (T), and p16INK4a levels in hematopoietic cells expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or SB203580.

Leukemogenic fusion proteins induce senescence in hematopoietic progenitors. (A) Bone marrow cells were isolated from 5-fluorouracil-treated mice, transduced with a retrovirus expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein, and stained for senescence-associated β-galactosidase. (B) Immunoblot analysis monitoring levels of p16INK4a and H3K9 Ac in hematopoietic cells expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein. (C) Hematopoietic cells expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein were analyzed by comet assay under alkali conditions. (D) Quantification of comet tail length. Error bars represent SEM. (E) Immunoblot analysis monitoring levels of phospho-ATM and, as a control, total ATM in hematopoietic cells expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein. (F) BrdU incorporation assay in hematopoietic cells stably expressing either a nonsilencing (NS) siRNA or one of 2 unrelated siRNAs directed against ATM, and expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein. Error bars represent SEM. (G) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylated p39 (P), total p38 (T), and p16INK4a levels in hematopoietic cells expressing empty vector, H-RAS V12, or a leukemogenic fusion protein treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or SB203580.

Here we have shown that well-studied leukemogenic fusion proteins can induce senescence in human fibroblasts and hematopoietic progenitors. However, there were some notable differences in senescence induction between the leukemogenic fusion proteins and that of other oncogenes. For example, unlike RAS and BRAF,1,18 the leukemogenic fusion proteins did not cause an initial hyperproliferative response (Figure 1A). Most importantly, like RAS- and BRAF-induced senescence, induction of senescence by RUNX1-ETO involved the DDR. By contrast, BCR-ABL and CBFB-MYH11 did not elicit a DDR, and senescence induction by these leukemogenic fusion proteins was DDR independent. A recent study found, similar to our results, that expression of RUNX1-ETO in primary fibroblasts results in growth arrest, which is accompanied by a level of DNA damage much lower than that observed in RAS-expressing fibroblasts.19 However, our ATM knockdown experiments show that, although the level of DNA damage elicited by RUNX1-ETO is relatively low, it is nonetheless important for the efficient induction of senescence. Collectively, our results reveal diverse molecular pathways for oncogene-induced senescence.

The finding that leukemogenic fusion proteins can induce senescence has important implications for the genetic basis of hematopoietic malignancies. Senescence is a tumor-prevention mechanism that is overcome during cancer development (supplemental Figure 4). Our results imply that hematopoietic malignancies harbor genetic or epigenetic alterations in genes involved in senescence induction. Delineating the pathways by which leukemogenic fusion proteins induce senescence should provide clues about the cooperating mutations that are involved in hematopoietic malignancies.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lucio Castilla, Warren Pear, and William Hahn for reagents; Lynn Chamberlain, Susan Griggs, Laura Almstead, and the Bioinformatics Core at the Yale Center of Excellence in Molecular Hematology for technical assistance; and Sara Evans for editorial assistance.

This work was supported in part by Yale University (start-up funds; N.W.). N.W. is a member of the Yale Cancer Center. M.R.G. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Authorship

Contribution: N.W., S.-Z.W., R.W.S., P.D.S., A.N., and X.Z. performed the experiments; and N.W., S.-Z.W., and M.R.G. analyzed the data and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Michael R. Green, Program in Gene Function and Expression, University of Massachusetts Medical School, 364 Plantation St, Worcester, MA 01606; e-mail: michael.green@umassmed.edu; or Narendra Wajapeyee, Department of Pathology, Yale University School of Medicine, P O Box 208023, 310 Cedar St, LH 214A, New Haven, CT 06520; e-mail: narendra.wajapeyee@yale.edu.

References

Author notes

N.W. and S.-Z.W. contributed equally to this study.