Abstract

NKp80, an activating homodimeric C-type lectin-like receptor (CTLR), is expressed on essentially all human natural killer (NK) cells and stimulates their cytotoxicity and cytokine release. Recently, we demonstrated that the ligand for NKp80 is the myeloid-specific CTLR activation-induced C-type lectin (AICL), which is encoded in the natural killer gene complex (NKC) adjacent to NKp80. Here, we show that NKp80 also is expressed on a minor fraction of human CD8 T cells that exhibit a high responsiveness and an effector memory phenotype. Gene expression profiling and flow cytometric analyses revealed that this NKp80+ T-cell subset is characterized by the coexpression of other NK receptors and increased levels of cytotoxic effector molecules and adhesion molecules mediating access to sites of inflammation. NKp80 ligation augmented CD3-stimulated degranulation and interferon (IFN)γ secretion by effector memory T cells. Furthermore, engagement of NKp80 by AICL-expressing transfectants or macrophages markedly enhanced CD8 T-cell responses in alloreactive settings. Collectively, our data demonstrate that NKp80 is expressed on a highly responsive subset of effector memory CD8 T cells with an inflammatory NK-like phenotype and promotes T-cell responses toward AICL-expressing cells. Hence, NKp80 may enable effector memory CD8 T cells to interact functionally with cells of myeloid origin at sites of inflammation.

Introduction

T cells can be subdivided according to their phenotype, state of activation, and responsiveness into naive, central memory, effector memory, and CD45RA+ effector memory T cells.1,2 CD45RA+ effector memory T cells (TEMRA cells) are thought to represent the most differentiated subset of T cells and are characterized by a high effector potential and a preferential recruitment into inflammation sites.2-4 In contrast to naive and central memory T cells, effector memory T cells lack expression of CCR7, a chemokine receptor that facilitates routine homing into lymph nodes. Unlike naive T cells, effector memory CD8 T cells commonly express receptors originally found on natural killer (NK) cells, and therefore are often referred to as NK receptors.5-9 Among these are members of the leukocyte receptor complex (LRC)–encoded killer cell immunoglobulin like receptors (KIR) as well as members of the natural killer gene complex (NKC)–encoded C-type lectin-like receptors (CTLR).7-9 Examples of NKC-encoded CTLR expressed on T cells are mouse Ly49 family MHC class I receptors and killer lectin-like receptor (KLR) family members such as CD94/NKG2A and KLRG1.7,9,10 Another prominent example of NKC-encoded CTLR is the activating receptor NKG2D, which not only triggers NK cell effector functions11 but also costimulates CD8 T cells in humans12 and promotes CD8 T cell–mediated tumor rejection and autoimmunity in mice.13,14

We recently showed that the stimulatory NK receptor NKp80 functionally engages the activation-induced C-type lectin (AICL).15 Both NKp80 and AICL are type II transmembrane, homodimeric CTLR, and their respective genes, KLRF1 and CLEC2B, are located in a tail-to-tail orientation only 7 kb apart in the telomeric subregion of the NKC adjacent to the CD69 gene.16,17 NKp80 is expressed on nearly all NK cells, whereas AICL is selectively expressed on myeloid cells such as monocytes and macrophages. In the presence of proinflammatory cytokines, NKp80-AICL engagement mutually promotes cytokine release by autologous NK cells and monocytes.15 These data suggest that the NKp80-AICL interaction may contribute to reciprocal activation of NK and myeloid cells at sites of inflammation. Further, NKp80 also promotes NK cytotoxicity against the malignant myeloid cell line U937,15 but involvement of NKp80 in the immunosurveillance of primary myeloid leukemia cells remains to be addressed.

In previous studies, NKp80 expression was noted for some γδ T cells and CD56+ T cells with frequencies varying greatly between individual donors.15,18 However, phenotypic characteristics of NKp80-expressing T cells and functional implications of NKp80 for T-cell biology have not yet been addressed. In our efforts to further elucidate the immunologic function of NKp80, we observed a widespread NKp80 expression by human cytomegalovirus (HCMV)–specific CD8 T cells and went on to further define the phenotype and functional properties of NKp80-expressing CD8 T cells.

Methods

Reagents

Anti–CD3-PerCP (SK7), anti–CD8-AmCyan/-PerCP/-APC-Cy7 (SK1), anti–CD56-PE-Cy7 (B159), anti–CCR7-PE-Cy7, anti–CD11c-PE (B-ly6), anti–CD162-PE (KPL-1), anti–4-1BBL-PE (C65-485), anti–HLA-DR-FITC (L243), anti–HLA-ABC-FITC (G46-2.6), anti–CD107a-FITC (H4A3), anti–granzyme B-FITC (GB11), anti-IL-2-APC (5344.11), anti–TNF-PE (6401.1111), anti–IFN-γ-FITC/-PE (4S.B3) were from BD Biosciences (Heidelberg, Germany); anti–CD45RA-Pacific Blue (HI100), anti–CD4-Pacific Blue, anti–CD27-APC-Cy7 (O323), and anti–perforin-PE (dG9) were from BioLegend (San Diego, CA); anti–CD28-FITC (KOLT-2), anti–CD29-FITC (2A4), anti–CD16-FITC (5D2), anti–CD11a-FITC (TB-133), anti–CD18-FITC (MEM48), anti–CD54-PE (15.2), and anti–CD62L-FITC (LT-TD180) were from Immunotools (Friesoythe, Germany); anti–CD45RA-PE-Cy5.5 was from Invitrogen (Karlsruhe, Germany); and anti–PD-1-APC (MIH4), anti–TCRαβ-PE (IP26), anti–CD127-FITC (eBioRDR5) were from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Anti–CD158b-APC (DX27), anti–CD158e-APC (DX9), anti–CD161-FITC (191B8), and anti–CD25-PE (4E3) were from Miltenyi Biotec (Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) and anti–ILT2-PE (HP-F1) from Beckman Coulter (Krefeld, Germany). Anti-CD8 (OKT8; ATCC CRL-8014) and anti-CD3 (OKT3; ATCC CRL-8001) were purified from hybridoma supernatant. OKT8 was biotinylated with sulfo-N-hydroxysuccinimidobiotin (Perbio Science, Bonn, Germany). Anti-NKp80 mAb 5D12 and NP (4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenylacetyl)-specific mouse IgG1 (control IgG1), the respective Alexa Fluor 647 conjugates and endotoxin-free F(ab′)2 derivatives, and NKp80 tetramers were previously described.15 Anti-KLRG1 mAb 13A219 was kindly provided by H. Pircher (University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany). Biotinylated major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I/peptide complexes HLA-A2/HCMV pp65495-503 (pp65 peptide NLVPMVATV) and HLA-A2/EBV LMP2426-434 (LMP2 peptide CLGGLLMTV) were a kind gift of S. Stevanovic (University of Tübingen) and tetramerized with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated streptavidin (Invitrogen) as described elsewhere.20

Cells

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by density centrifugation from venous heparinized blood of healthy donors after informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approval from the University of Tübingen local ethics committee. For purification of CD8+ cells, PBMCs were incubated with 5 μg/mL biotinylated OKT8 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.5% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 2 mM ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) for 15 minutes at 4°C. After washing, cells were incubated with streptavidin-coupled microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) for further 15 minutes at 4°C, and CD8+ cells were purified according to the manufacturer's instructions. Isolated CD8+ cells had a purity greater than 95% and were cultured in T-cell medium (TCM; RPMI-1640 with 10% human serum) for at least 2 days before further stimulation or cell sorting. Macrophages were obtained after cultivation of plastic-adherent freshly isolated monocytes for 10-14 days in the presence of 10 ng/mL macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF; Immunotools) and 1% human serum in X-vivo 15 (Cambrex Biosciences, East Rutherford, NJ). 293T cells stably expressing AICL (293T-AICL) were obtained by transfection with a bicistronic AICL-EGFP construct using FuGENE6 (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) and cultured in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM)/10% FCS with G418 (1.8 mg/mL). The AICL-EGFP construct was obtained by cloning the full-length open reading frame of AICL in front of the internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) of the vector pIRES-EGFP (Clontech, Mountain View, CA).

Flow cytometry

After blocking Fc receptors with human IgG (at 10 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, Munich, Germany), cells were stained with fluorophore-conjugated antibodies and analyzed by the use of flow cytometry with FACSCalibur, FACS Canto II or LSR-II machines (BD Biosciences). For analysis of perforin and granzyme B, unstimulated cells were fixed and permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences). Washing cells twice with PBS supplemented with 0.1% saponin, 5% FCS, and 2 mmol/L EDTA was followed by incubation with the respective antibodies. To exclude NK cells from the analysis of CD8 cells, CD3+ CD8+ cells were gated for analysis. For analysis of HCMV- or EBV-specific CD8 T cells, PBMCs were first stained with the respective monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and then with PE-labeled HLA-A2/HCMV- or HLA-A2/EBV-tetramers, respectively, in PBS/50% FCS.

Microarray analysis

Freshly isolated PBMCs from 6 healthy donors (age range, 25-30 years; 3 male and 3 female donors) were pooled, depleted of CD4+ and CD14+ cells by MACS, and subsequently stained with anti-CCR7-PE-Cy7, anti-TCRαβ-PE, anti-CD3-FITC, anti-CD8-AmCyan, and anti-NKp80-Alexa647. NKp80+ and NKp80− subpopulations of CCR7− CD8 αβ T cells were sorted on a FACSAria cell sorter (BD Biosciences). RNA isolation, complementary (c)DNA synthesis, and hybridization with Affymetrix HG-U133 Plus 2.0 microarrays was performed by the Microarray Facility, Tübingen. We performed data analysis by using the GCOS software (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). Scaling of signal intensities was performed for each array based on the average intensity of approximately 100 probe sets representing housekeeping genes selected by Affymetrix (http://www.affymetrix.com/support/technical/mask_files.affx). Differences in expression between samples were determined by baseline comparison algorithms provided by GCOS. The transcriptome of the NKp80− subset was always defined as the baseline. Microarray data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database under accession number GSE10178 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE10178).

Degranulation assay and intracellular cytokine staining

Degranulation of purified CD8+ T cells was measured by staining for surface CD107a during a 6-hour incubation period in the presence of Golgi Stop (BD Biosciences). CD8+ cells (105) were resuspended in TCM and stimulated with 1 nmol/L phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA) and 10 ng/mL ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) or indicated antibodies. For antibody stimulation, plates were coated with 0.5 μg/mL OKT3 in combination with 5 μg/mL control IgG1 or 5 μg/mL 5D12. Anti-CD107a-FITC was added to the assay and Golgi Stop (monensin, BD Biosciences) after 1 hour of incubation according to the manufacturer's instructions. After additional 5 hours, CD8+ CD3+ cells were gated and analyzed for CD107a by flow cytometry. For analysis of intracellular IFN-γ, stimulated CD8 T cells were permeabilized after the incubation period with Cytofix/Cytoperm and stained with anti–IFN-γ-PE. CD8+ CD3+ cells were gated and analyzed by flow cytometry. For analysis of the expression of multiple cytokines, freshly isolated PBMCs were stimulated with PMA/ionomycin for 6 hours in the presence of Golgi Stop and Brefeldin A (Sigma-Aldrich), permeabilized, simultaneously stained with anti–IFN-γ-FITC, anti–TNF-PE, and anti–IL-2-APC, and coexpression of these cytokines by NKp80+ and NKp80− subsets of CCR7− CD8+ CD3+ cells evaluated by flow cytometry.

Proliferation assay

PBMCs or purified CD8+ cells were labeled in PBS for 10 minutes at room temperature with 0.5 μmol/L CFSE (5,6-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester; Invitrogen). After further incubation with RPMI-1640/20% FCS for 20 minutes, cells were washed thrice and seeded at a density of 3 × 105/mL in X-Vivo 15 (Cambrex Biosciences) supplemented with 10% FCS. CFSE-labeled cells were cultured for 7 days either with a cytokine cocktail containing interleukin (IL)-2 (300 U/mL; Novartis, Basel, Switzerland), IL-15 (10 ng/mL; Promocell, Heidelberg, Germany), and IL-7 (10 ng/mL; Immunotools) or with allogeneic macrophages in the presence of F(ab′)2 fragments of mAb 5D12 or control IgG1. Cells were stained for surface markers and CD3+ CD8+ cells analyzed via flow cytometry for CFSE.

Alloreactive T-cell responses

For analysis of alloresponses to 293T cells, purified CD8+ from healthy donors were stimulated in vitro for 8 days in TCM supplemented with 50 U/mL IL-2 in the presence of irradiated (60 Gy) 293T-neo or 293T-AICL cells. On day 8, CD8+ cells were restimulated with the respective 293T transfectants for 6 hours at a 1:1 ratio and analyzed for degranulation by CD107a staining in flow cytometry. Where indicated, anti-NKp80 mAb (5D12) or control IgG1 (both at 10 μg/mL) were added twice, at beginning of stimulation (day 0) and at beginning of restimulation (day 8). Alternatively, NKp80+ and NKp80− subsets of effector memory T cells (CCR7−CD3+CD8+) underwent fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) from purified CD8+ cells and were stimulated in vitro with irradiated 293T-neo cells in TCM containing 50 U/mL IL-2 and 10 ng/mL IL15 for 8 to 10 days and subsequently analyzed in 6-hour chromium release assays as previously described15 for cytotoxicity against 293T-neo and 293T-AICL cells. For analyses of alloresponses to macrophages, purified CD8+ cells were stimulated in vitro for 8 days in X-vivo medium (10% human serum, 50 U/mL IL-2) in the presence of irradiated (30 Gy) allogeneic macrophages and endotoxin-free F(ab′)2 of mAb 5D12 or control IgG1, respectively. On day 8, CD8+ cells were restimulated with macrophages from the same donor for 6 hours at a 1:1 ratio in the presence of freshly added F(ab′)2 and analyzed for IFN-γ secretion.

Statistical analysis

Statistical evaluation was performed with the Student t test for paired data by using the SigmaStat 3.1 software (Systat Software, San Jose, CA).

Results

NKp80 is expressed by a subset of human CD8 T cells

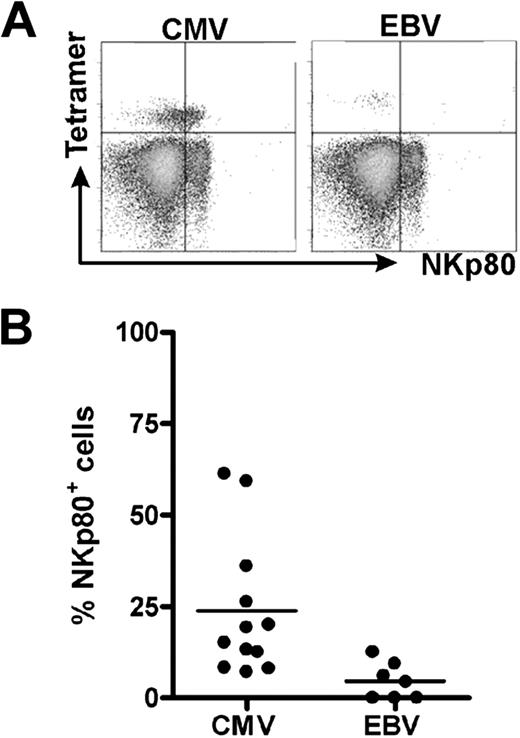

In the course of characterizing HCMV-specific CD8 αβ T cells, we detected NKp80 receptors on a substantial fraction of HLA-A2/HCMV pp65495-503-specific CD8 αβ T cells in most individuals analyzed. In 2 of the 13 tested donors, more than 50% of the HLA-A2/HCMVpp65-specific T cells expressed NKp80 (Figure 1A). Overall, frequencies of NKp80+ cells among these HCMV-specific CD8 T cells varied greatly (range, 7%-61%). We also detected NKp80+ cells among EBV-specific CD8 T cells of some of these donors, although the frequencies were rather low (Figure 1B).

NKp80 is expressed by certain HCMV-specific CD8 T cells. Shown are flow cytometric analyses of HCMV- and EBV-specific CD8 T cells for surface NKp80. Freshly isolated PBMCs from healthy HLA-A2+ donors were stained with NKp80-specific mAb 5D12 and HLA-A2/HCMV pp65495-503 or HLA-A2/EBV LMP2426-434 tetramers. CD8+ cells were gated for analysis. (A) Flow cytometric data of a selected donor with abundant NKp80 expression on HCMV-pp65–specific CD8 T cells (left) and a poor NKp80 expression on EBV-specific T cells (right). (B) Frequencies of NKp80+ cells among HCMV-specific and EBV-specific CD8 T cells. Among the 13 donors analyzed (age range, 31-59 years), 12 contained detectable HCMV-specific and 7 detectable EBV-specific T cells. Horizontal bars represent mean values.

NKp80 is expressed by certain HCMV-specific CD8 T cells. Shown are flow cytometric analyses of HCMV- and EBV-specific CD8 T cells for surface NKp80. Freshly isolated PBMCs from healthy HLA-A2+ donors were stained with NKp80-specific mAb 5D12 and HLA-A2/HCMV pp65495-503 or HLA-A2/EBV LMP2426-434 tetramers. CD8+ cells were gated for analysis. (A) Flow cytometric data of a selected donor with abundant NKp80 expression on HCMV-pp65–specific CD8 T cells (left) and a poor NKp80 expression on EBV-specific T cells (right). (B) Frequencies of NKp80+ cells among HCMV-specific and EBV-specific CD8 T cells. Among the 13 donors analyzed (age range, 31-59 years), 12 contained detectable HCMV-specific and 7 detectable EBV-specific T cells. Horizontal bars represent mean values.

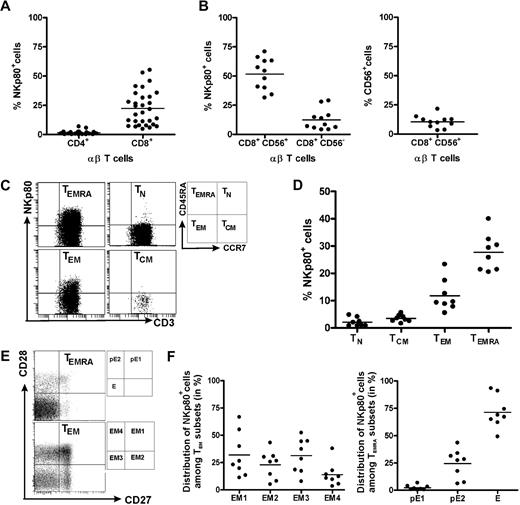

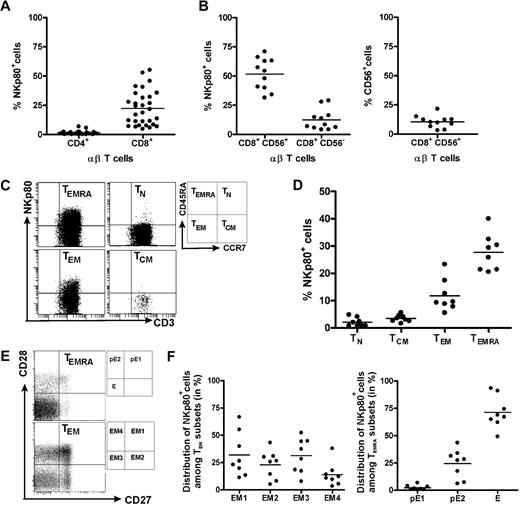

This finding prompted us to revisit NKp80 expression by αβ T cells and to further characterize NKp80+ CD8 T cells with regard to phenotype and a potential functional role of NKp80. Flow cytometric analyses of freshly isolated PBMCs from 30 healthy donors confirmed previous reports that NKp80 is variably expressed on a substantial fraction of T cells15,18 : Whereas almost all CD4 αβ T cells lacked surface NKp80 (range, 0%-7%; mean, 1.5%), NKp80 was detected on a subset of CD8+ αβ T cells at greatly varying frequencies among 30 donors (range, 5%-55%; mean, 22.4%; Figure 2A).

NKp80 expression on CD8 T cells is largely restricted to subsets of effector memory cells. Freshly isolated PBMCs from healthy donors were analyzed for NKp80 surface expression (anti-NKp80 mAb 5D12) by various subsets of αβ T cells. (A) Frequencies of NKp80+ cells among CD8 αβ T cells or CD4 αβ T cells. Stained PBMCs of 30 donors were gated for CD3 and αβ TCR and analyzed for frequencies of NKp80+ cells among CD4- or CD8-expressing cells. (B) Frequencies of NKp80+ cells among CD56+ and CD56− CD8 T cells (left), and of CD56+ cells among CD8 T cells (right). Stained PBMCs of 11 donors were analyzed for NKp80+ cells after gating on CD3 and CD8. (C,D) Analysis of NKp80 expression by naive (TN), central memory (TCM), effector memory (TEM), and effector (TEMRA) CD8 αβ T cells. PBMCs gated for CD8 and αβ TCR-gated cells were further subgated according to CD45RA and CCR7 expression (C, right), and subgated cells analyzed for frequencies of NKp80+ cells. (C) Representative example and (D) data compiled from 8 donors are shown. (E,F) Prevalence of NKp80+ cells among subsets of TEM and TEMRA CD8 αβ T cells. PBMCs were gated as in (C) and TEM and TEMRA cells further subdivided according to their CD27/CD28 expression (E, right). (E) Representative analysis of TEM and TEMRA CD8 T cells for distribution of NKp80+ (black dots) and NKp80− (gray dots) cells in the respective subsets. (F) Distribution of NKp80+ TEM CD8 αβ T cells among subsets EM1, EM2, EM3, and EM4 (left) and NKp80+ TEMRA CD8 αβ T cells among pE1, pE2, and E subsets (right) is depicted for 8 donors. In panels A, B, D, and F, means are indicated by horizontal bars.

NKp80 expression on CD8 T cells is largely restricted to subsets of effector memory cells. Freshly isolated PBMCs from healthy donors were analyzed for NKp80 surface expression (anti-NKp80 mAb 5D12) by various subsets of αβ T cells. (A) Frequencies of NKp80+ cells among CD8 αβ T cells or CD4 αβ T cells. Stained PBMCs of 30 donors were gated for CD3 and αβ TCR and analyzed for frequencies of NKp80+ cells among CD4- or CD8-expressing cells. (B) Frequencies of NKp80+ cells among CD56+ and CD56− CD8 T cells (left), and of CD56+ cells among CD8 T cells (right). Stained PBMCs of 11 donors were analyzed for NKp80+ cells after gating on CD3 and CD8. (C,D) Analysis of NKp80 expression by naive (TN), central memory (TCM), effector memory (TEM), and effector (TEMRA) CD8 αβ T cells. PBMCs gated for CD8 and αβ TCR-gated cells were further subgated according to CD45RA and CCR7 expression (C, right), and subgated cells analyzed for frequencies of NKp80+ cells. (C) Representative example and (D) data compiled from 8 donors are shown. (E,F) Prevalence of NKp80+ cells among subsets of TEM and TEMRA CD8 αβ T cells. PBMCs were gated as in (C) and TEM and TEMRA cells further subdivided according to their CD27/CD28 expression (E, right). (E) Representative analysis of TEM and TEMRA CD8 T cells for distribution of NKp80+ (black dots) and NKp80− (gray dots) cells in the respective subsets. (F) Distribution of NKp80+ TEM CD8 αβ T cells among subsets EM1, EM2, EM3, and EM4 (left) and NKp80+ TEMRA CD8 αβ T cells among pE1, pE2, and E subsets (right) is depicted for 8 donors. In panels A, B, D, and F, means are indicated by horizontal bars.

In agreement with previous reports15,18 we found that NKp80+ cells were especially prevalent among the CD8+ αβ T cells expressing CD56+ (range, 31%-71%; mean, 51.6%; Figure 2B). CD56+ T cells have been reported to represent a potent effector subpopulation,21 but represent only a minor fraction of all CD8+ T cells, at least in our panel of donors (range, 3-22%; mean, 10.5%; Figure 2B). In addition, we now also observed NKp80 expression on a small proportion of CD8+ CD56− αβ T cells at frequencies, again varying greatly between donors (range, 4%-29%; mean, 12.4%; Figure 2B).

NKp80 is commonly expressed by effector memory CD8 T cells

Next, we further defined the phenotype of NKp80+ CD8 αβ T cells. According to the model proposed by Sallusto et al,1,2 CD8+ αβ T cells can be classified into 4 different subpopulations according to activation state and surface expression of CD45RA and CCR7: naive (TN; CD45RA+, CCR7+), central memory (TCM; CD45RA−, CCR7+), effector memory (TEM; CD45RA−, CCR7−) and CD45RA+ effector memory T cells (alias effector T cells [TEMRA]; CD45RA+, CCR7+).We found that expression of NKp80 and CCR7 on CD8 T cells is almost completely mutually exclusive (Figure 2C). Thus, NKp80 expression is strictly associated with TEM and TEMRA cells but is nearly entirely absent from naive or TCM cells (Figures 2C,D). However, again, there is great interindividual variability in NKp80 expression on effector memory T cells, both for the TEM (range, 6%-23%; mean, 12%) and TEMRA subset (range, 21%-40%; mean: 28%).

HCMV-specific CD8 T cells have been reported mostly to possess a TEMRA phenotype,22,23 which is in line with the abundant NKp80 expression observed here (Figure 1). Further subdivisions within the effector memory T cells recently have been proposed on the basis of the expression of the costimulatory molecules CD27 and CD28.4,23 Accordingly, TEMRA cells can be subdivided into 3 subsets and TEM into 4 subsets, respectively, whereas naive T cells and TCM cells homogeneously express both CD27 and CD28 (Figure 2E). In this context, NKp80 expression was not found to be preferentially associated with any particular TEM subset. On average, there is an almost equal distribution of NKp80+ cells among the EM1 (CD27+, CD28+; range, 11%-67%; mean, 32%), EM2 (CD27+, CD28−; range, 5%-31%; mean, 23%), EM3 (CD27−, CD28−; range, 8%-52%; mean, 31%), and EM4 (CD27−, CD28+; range, 3%-38%; mean: 14%) subsets, with a large degree of interindividual variation (Figure 2E,F). In contrast to EM cells, most NKp80+ TEMRA cells express neither CD27 nor CD28 and therefore belong to the effector (E) subset (CD27−, CD28−; range, 49%-93%; mean, 71%). A minor fraction of NKp80+ TEMRA cells exhibit a pE1 (CD27+, CD28+; range, 0.4-6.5; mean, 3%) and a pE2 (CD27+, CD28−; range: 6%-43%; mean, 24%) phenotype, respectively (Figure 2E,F). Expression of CD28 and CD27 is sequentially silenced in the course of CD8 T-cell differentiation and the effector (E) subset is considered to possess the most potent cytotoxic capacity.4,24,25

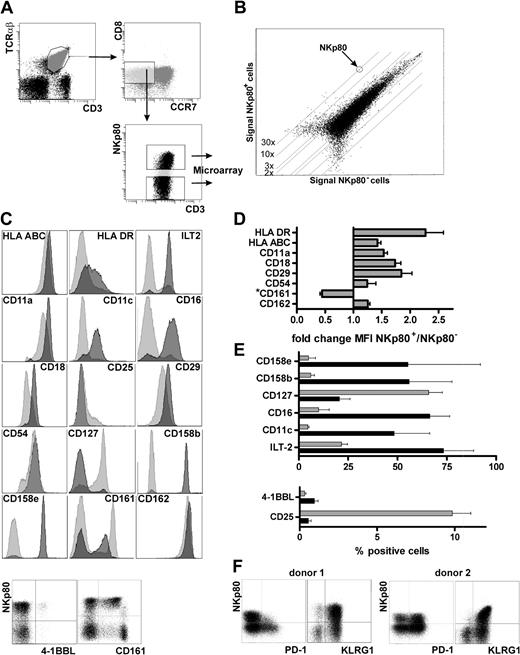

Transcriptional profiling of NKp80+ CD8 T cells

To further characterize NKp80-expressing CD8 T cells, we compared the transcriptomes of NKp80+ and NKp80− effector memory T cells. For this purpose, we sorted both NKp80+ and NKp80− subsets of effector memory CD8 T cells (CD3+, TCRαβ+, CD8+, CCR7−) from freshly isolated PBMCs by FACS and performed whole-genome oligonucleotide arrays on their cDNA (Figure 3A). A very similar global gene expression profile was found in both subsets (Figure 3B), with the majority of those genes that are differentially expressed being immune-associated. NKp80+ cells contain markedly increased levels of transcripts encoding several members of the KIR family with a most pronounced overexpression of the HLA-C–specific inhibitory receptors KIR2DL2 and KIR2DL3 (Table 1). Transcripts encoding other NK receptors such as NKG2E, NKp30/NCR3, CD16, CD160/BY55, CD244/2B4, and CD306/LAIR2 also are overexpressed in the NKp80+ subset. Similarly, transcripts of the inflammatory cytokine TL1A/VEGI and chemokines XCL2, CCL3, and CCL4 are increased in NKp80+ T cells, whereas cytokines/cytokine receptors tumor necrosis factor (TNF), IL-14, IL-23, IL-6R, and IL-7R/CD127 are decreased. With regard to cytotoxic effector molecules, transcripts of perforin (3.25-fold) as well as granzymes A (1.23-fold) and B (1.52-fold) are moderately up-regulated in NKp80+ cells, whereas granzyme K levels are greater (3.48-fold) in NKp80− cells. The latter is in line with a previous study in which the authors reported that granzyme K expression ceases during differentiation of effector memory CD8 T cells.26

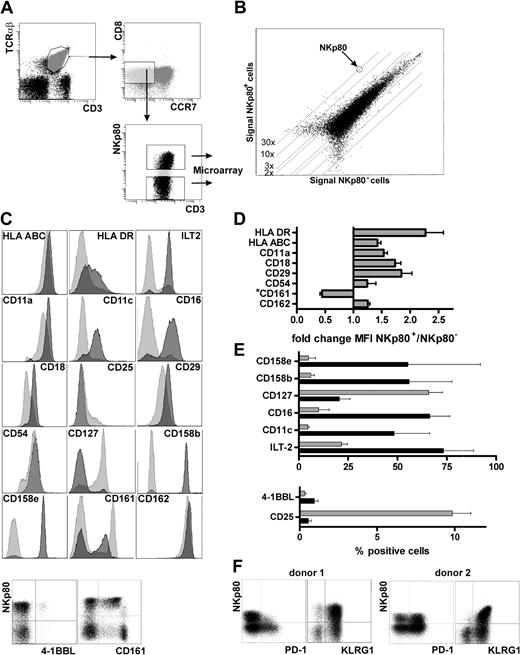

NKp80+ effector CD8 T cells possess an inflammatory NK-like phenotype. (A) NKp80+ and NKp80− cells within the effector memory CD8 subset (CCR7− CD8+ αβ TCR+) in freshly isolated PBMCs (pooled from 6 donors and depleted of CD4+ and CD14+ cells) were sorted by FACS for transcriptional profiling by microarray analysis. (B) Signal intensities of mRNA microarrays for FACS-sorted NKp80+ versus NKp80− cells. One dot represents expression of one gene. Differentially expressed genes are listed in Table 1. (C-F) Flow cytometric analysis of effector memory CD8 T cells (CCR7− CD8+ αβ TCR+) for coexpression of NKp80 and various cell surface receptors selected on the basis of differential mRNA expression in NKp80+ versus NKp80− subsets of CCR7− CD8+ T cells (see Table 1). (C) Results for a representative donor. For analysis of most surface molecules, respective histograms for NKp80+ (dark gray) and NKp80− cells (light gray) are overlaid. Coexpression of 4-1BBL and CD161, respectively, with NKp80 is shown in dot plots. (D,E) Data compiled from 3 donors and depicted either as fold change in MFI in NKp80+ versus NKp80− cells (D) or percentage of marker-positive cells (E) among NKp80+ cells (■) and NKp80− cells ( ). Mean values of data are shown with error bars indicating standard deviation. For analysis of NKR-P1A/CD161 in (D), only MFI of the CD161+ subpopulation were considered. (F) Coexpression of PD-1 and KLRG1, respectively, with NKp80 on effector memory CD8 T cells (CCR7− CD8+ αβ TCR+) of 2 representative donors.

). Mean values of data are shown with error bars indicating standard deviation. For analysis of NKR-P1A/CD161 in (D), only MFI of the CD161+ subpopulation were considered. (F) Coexpression of PD-1 and KLRG1, respectively, with NKp80 on effector memory CD8 T cells (CCR7− CD8+ αβ TCR+) of 2 representative donors.

NKp80+ effector CD8 T cells possess an inflammatory NK-like phenotype. (A) NKp80+ and NKp80− cells within the effector memory CD8 subset (CCR7− CD8+ αβ TCR+) in freshly isolated PBMCs (pooled from 6 donors and depleted of CD4+ and CD14+ cells) were sorted by FACS for transcriptional profiling by microarray analysis. (B) Signal intensities of mRNA microarrays for FACS-sorted NKp80+ versus NKp80− cells. One dot represents expression of one gene. Differentially expressed genes are listed in Table 1. (C-F) Flow cytometric analysis of effector memory CD8 T cells (CCR7− CD8+ αβ TCR+) for coexpression of NKp80 and various cell surface receptors selected on the basis of differential mRNA expression in NKp80+ versus NKp80− subsets of CCR7− CD8+ T cells (see Table 1). (C) Results for a representative donor. For analysis of most surface molecules, respective histograms for NKp80+ (dark gray) and NKp80− cells (light gray) are overlaid. Coexpression of 4-1BBL and CD161, respectively, with NKp80 is shown in dot plots. (D,E) Data compiled from 3 donors and depicted either as fold change in MFI in NKp80+ versus NKp80− cells (D) or percentage of marker-positive cells (E) among NKp80+ cells (■) and NKp80− cells ( ). Mean values of data are shown with error bars indicating standard deviation. For analysis of NKR-P1A/CD161 in (D), only MFI of the CD161+ subpopulation were considered. (F) Coexpression of PD-1 and KLRG1, respectively, with NKp80 on effector memory CD8 T cells (CCR7− CD8+ αβ TCR+) of 2 representative donors.

). Mean values of data are shown with error bars indicating standard deviation. For analysis of NKR-P1A/CD161 in (D), only MFI of the CD161+ subpopulation were considered. (F) Coexpression of PD-1 and KLRG1, respectively, with NKp80 on effector memory CD8 T cells (CCR7− CD8+ αβ TCR+) of 2 representative donors.

As expected, transcript levels of CCR7, CD27, and CD28 are markedly decreased in the NKp80+ subset. Conversely, transcripts of MHC class I and class II molecules are increased. It is noteworthy that transcripts of adhesion molecules also are differentially expressed in these T-cell subsets. NKp80+ cells express increased levels of the integrins αX, β2, and β7, whereas integrin β3 is decreased. Further, transcripts for PECAM-1 and CD99, which are both important for T-cell diapedesis,27 also are preferentially expressed in NKp80+ T cells. Interestingly, expression of the P-selectin ligand (PSGL-1) and one of its intracellular adaptors (ie, moesin) is increased markedly in NKp80+ cells, whereas transcripts of E-selectin (CD62E), a counterreceptor of PSGL-1, are down-regulated.28,29

NKp80+ CD8 T cells possess an NK-like, “inflammatory” phenotype

Next, we investigated whether differences in the transcriptomes of NKp80+ versus NKp80− effector memory T cells translate into a differential expression of surface receptors. In accord with increased transcript levels, we observed an up-regulated expression of MHC class I and class II molecules on NKp80+ cells. Similarly, expression levels of integrins αL (CD11a) and β2 (CD18), of ICAM1 (CD54) and PSGL-1 (CD162), were increased on NKp80+ T cells (Figure 3C,D). Integrin αX (CD11c) was detected on many NKp80+ cells, whereas NKp80− cells were mostly CD11c-negative. Again in line with the transcriptional profiling, NK-cell receptors such as ILT-2, CD16, CD158b, and CD158e were abundantly expressed by NKp80+ cells but were found only on a few NKp80− cells. Conversely, the receptors for cytokines IL-2 (CD25) and IL-7 (CD127) were more prominently expressed by NKp80− cells but rarely by NKp80+ cells. There was no correlation between surface expression of NKp80 and expression of CD56, CD57, or CD62L neither at transcript nor protein level. KLRG1, an “NK receptor” associated with a memory phenotype of T cells,19,30 was expressed on almost all NKp80+ and most NKp80− effector memory cells, which is in line with a slight increase of KLRG1 transcript levels in the NKp80+ subset (Table 1, Figure 3F). For PD-1, an inhibitory member of the B7 family and marker for exhausted T cells,31,32 transcript levels are lower for NKp80+ cells compared with NKp80− cells (Table 1). Correspondingly, PD-1–expressing cells were clearly more frequent among NKp80− cells compared with NKp80+ cells in 4 of 7 donors tested, whereas they were present at similar frequencies in the other 3 donors (Figure 3F and data not shown). The increased levels of 4-1BBL transcripts in NKp80+ cells (Table 1) turned out to be attributable to the presence of a small population of 4-1BBL+ CD8 T cells within the NKp80+ subset (∼1%), which was observed for all 3 donors analyzed (Figure 3C-E). Of note, most effector memory CD8 T cells that expressed NKR-P1A (CD161), an inhibitory KLR related to NKp80, showed a reduced expression of NKR-P1A when NKp80 was coexpressed and vice versa (Figure 3C,D). Together, data from transcriptional profiling and cell surface receptor analyses of NKp80+ effector memory CD8 T cells revealed that these are cells with an NK-like phenotype and an increased expression of adhesion molecules which may facilitate migration into inflamed, peripheral tissues.4

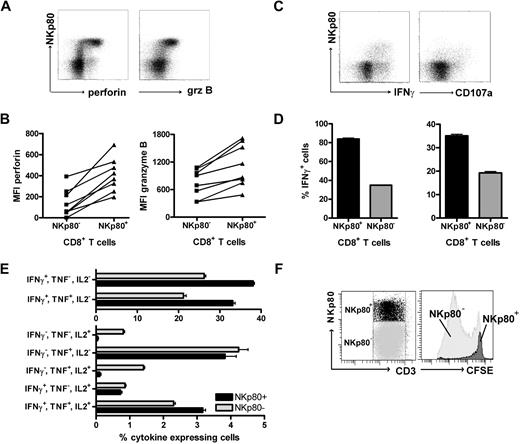

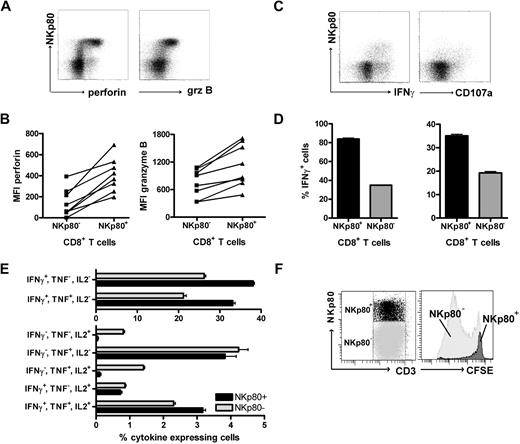

NKp80+ CD8+ αβ T cells are potent effector cells

To assess the cytolytic capacity of NKp80+ CD8+ αβ T cells, we analyzed intracellular levels of cytotoxic effector molecules by flow cytometry. NKp80+ CD8 αβ T cells revealed greater levels of both granzyme B and perforin than NKp80− CD8 αβ T cells in all 8 donors tested (Figure 4A,B). To address T-cell responsiveness, we measured intracellular levels of IFN-γ and surface expression of the endosomal marker CD107a (Lamp1) after stimulation with PMA/ionomycin. NKp80+ CD8+ αβ T cells were clearly more responsive than NKp80− cells (Figure 4C,D). Together, these data suggest that NKp80-expressing CD8 T cells are potent effectors. It has been reported that differentiation of memory CD8 T cells is associated with a transition from a polyfunctional stage at which multiple cytokines are expressed to a more restricted cytokine production with a predominance of IFN-γ secretion.31 Hence, we assessed simultaneous secretion of cytokines IL-2, TNF, and IFN-γ by NKp80+ and NKp80− effector memory CD8 T cells. We found that cells expressing all 3 cytokines simultaneously or only TNF were distributed equally in both subpopulations (Figure 4E). In contrast, cells expressing only IFN-γ (or IFN-γ in combination with TNF) were more prevalent among NKp80+ T cells, whereas cells expressing only IL-2 (or IL-2 in combination with TNF) were almost exclusively in the NKp80− T-cell subset.

NKp80+ CD8 T cells are potent effectors. (A,B) Enhanced expression of cytotoxic effector proteins perforin and granzyme B by NKp80+ CD8 T cells. Flow cytometric analysis of freshly isolated PBMCs gated on CD3+CD8+ cells for coexpression of NKp80 and intracellular perforin or granzyme B, respectively. (A) Representative dot plot analysis of 1 donor and (B) compiled MFI data for 8 healthy donors are shown. Lines indicate MFI values derived from same donors. (C,D) High responsiveness of NKp80+ CD8 T cells. Freshly purified CD8+ cells were stimulated with PMA/ionomycin for 6 hours and stained for CD107a or intracellular IFNγ in conjunction with NKp80. CD3+CD8+ T cells were gated for flow cytometric analysis. Dot plots (C) and means and standard deviations (D) of triplicates for one representative donor. Similar results were obtained with 2 other donors (not shown). (E) Multiple cytokine expression by NKp80+ CD8 T cells. Freshly isolated PBMCs were stimulated with PMA/ionomycin for 6 hours and simultaneously stained for intracellular IFN-γ, TNF, and IL-2. CD3+CD8+CCR7− T cells were gated for flow cytometric analysis of cytokine expression by NKp80+ and NKp80− cells, respectively. Means and standard deviations of frequencies of T-cell subsets expressing different combinations of cytokines are shown for 1 representative donor. Similar data were obtained with 3 other donors. (F) Fresh PBMCs were stained with CFSE and cultured for 8 days in the presence of IL-2, IL-7, and IL-15. On day 8, NKp80+CD3+ and NKp80−CD3+ cells were gated (left) and analyzed for CFSE levels (right). Data are representative of 5 experiments.

NKp80+ CD8 T cells are potent effectors. (A,B) Enhanced expression of cytotoxic effector proteins perforin and granzyme B by NKp80+ CD8 T cells. Flow cytometric analysis of freshly isolated PBMCs gated on CD3+CD8+ cells for coexpression of NKp80 and intracellular perforin or granzyme B, respectively. (A) Representative dot plot analysis of 1 donor and (B) compiled MFI data for 8 healthy donors are shown. Lines indicate MFI values derived from same donors. (C,D) High responsiveness of NKp80+ CD8 T cells. Freshly purified CD8+ cells were stimulated with PMA/ionomycin for 6 hours and stained for CD107a or intracellular IFNγ in conjunction with NKp80. CD3+CD8+ T cells were gated for flow cytometric analysis. Dot plots (C) and means and standard deviations (D) of triplicates for one representative donor. Similar results were obtained with 2 other donors (not shown). (E) Multiple cytokine expression by NKp80+ CD8 T cells. Freshly isolated PBMCs were stimulated with PMA/ionomycin for 6 hours and simultaneously stained for intracellular IFN-γ, TNF, and IL-2. CD3+CD8+CCR7− T cells were gated for flow cytometric analysis of cytokine expression by NKp80+ and NKp80− cells, respectively. Means and standard deviations of frequencies of T-cell subsets expressing different combinations of cytokines are shown for 1 representative donor. Similar data were obtained with 3 other donors. (F) Fresh PBMCs were stained with CFSE and cultured for 8 days in the presence of IL-2, IL-7, and IL-15. On day 8, NKp80+CD3+ and NKp80−CD3+ cells were gated (left) and analyzed for CFSE levels (right). Data are representative of 5 experiments.

Next, we investigated the proliferative capacity of NKp80+ CD8+ αβ T cells. Freshly isolated PBMCs were CFSE-labeled and cultured in vitro in the presence of a mixture of growth-promoting cytokines (IL-2, IL-7, IL-15) for 7 days. In line with previous reports, strongly proliferating cells had a naive or a central memory phenotype, whereas TEMRA cells proliferated poorly or not at all (data not shown). Analysis of NKp80+ versus NKp80− T cells showed that NKp80+ T cells had not proliferated notably, whereas most NKp80− T cells had undergone extensive rounds of cell division (Figure 4F).

NKp80 promotes CD8 T-cell effector functions

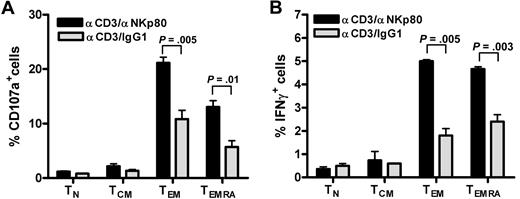

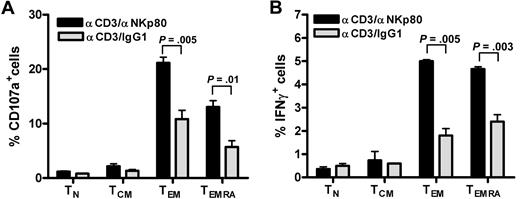

We and others previously reported that NKp80 stimulates effector functions of NK cells.15,18 To address the functional relevance of NKp80 for CD8 T cells, we stimulated freshly purified CD8 T cells with anti-NKp80 mAb 5D12 together with anti-CD3 mAb OKT3 and monitored intracellular expression of IFN-γ and the appearance of CD107a on the cell surface separately for the 4 major CD8 T-cell subsets. Stimulation with anti-CD3/anti-NKp80 resulted in a marked increase of responding CD107a+ or IFN-γ+ T cells in either the TEMRA or TEM subset compared with anti-CD3/control IgG1-exposure (Figure 5). Neither naive T cells nor TCM cells, both largely devoid of NKp80 expression, showed enhanced responses to anti-NKp80 treatment.

NKp80 stimulates effector functions of CD8 T cells. (A,B) CD8+ cells were purified from a healthy donor and stimulated for 6 hours with mixtures of immobilized anti-CD3 mAb OKT3 and anti-NKp80 mAb 5D12 or anti-CD3 and control IgG1, and subsequently analyzed for (A) CD107a and (B) intracellular IFN-γ expression. TN, TCM, TEM, and TEMRA were separately evaluated by gating on CD3 and appropriate CD45RA/CCR7 phenotypes. Means and standard deviations of triplicates are shown. Similar results were obtained with CD8+ cells from 2 other donors (data not shown).

NKp80 stimulates effector functions of CD8 T cells. (A,B) CD8+ cells were purified from a healthy donor and stimulated for 6 hours with mixtures of immobilized anti-CD3 mAb OKT3 and anti-NKp80 mAb 5D12 or anti-CD3 and control IgG1, and subsequently analyzed for (A) CD107a and (B) intracellular IFN-γ expression. TN, TCM, TEM, and TEMRA were separately evaluated by gating on CD3 and appropriate CD45RA/CCR7 phenotypes. Means and standard deviations of triplicates are shown. Similar results were obtained with CD8+ cells from 2 other donors (data not shown).

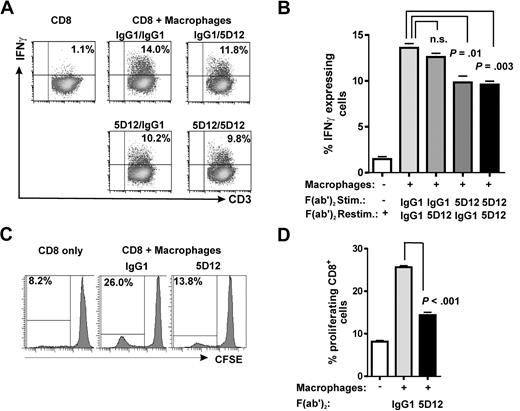

NKp80 augments alloreactive responses of CD8 T cells

To address the functional consequences of ligand-mediated NKp80 stimulation, we tested alloreactivity of CD8 T cells exposed to cells expressing the NKp80-ligand AICL. To this end, freshly purified CD8 T cells were cocultured with irradiated mock-transfected 293T cells (293T-neo) or 293T-transfectants stably expressing AICL (293T-AICL; Figure 6A), and alloreactive responses were measured after 8 days in a CD107a degranulation assay. A greatly increased frequency of degranulating CD8 T cells was observed in the 293T-AICL–stimulated cultures compared with controls; this effect was partially inhibited by addition of the anti-NKp80 mAb 5D12 to the cultures (Figure 6B,C).

NKp80-AICL interactions enhance alloreactive CD8 T-cell responses. (A, left) 293T-AICL transfectants broadly express AICL at the cell surface and bind soluble NKp80. Staining of 293T-AICL with anti-AICL mAb 7F12 (black histogram) and isotype control (dashed line) overlaid with staining of 293T-neo (7F12 [gray histogram]; isotype control [dotted line]). (A, right) Tetramers of soluble NKp80 ectodomains bind to 293T-AICL (black histogram) but not to 293T-neo (gray histogram). (B,C) Purified CD8+ cells were cocultured with irradiated 293T-neo or 293T-AICL in the presence of IL-2 and, where indicated, of anti-NKp80 5D12 or control IgG1. After 8 days of coculture, cells were restimulated with 293T-neo or 293T-AICL cells and CD107a expression of CD3+ cells was analyzed with flow cytometry. (B) Representative dot plots for donor 1. (C) Means and standard deviations of triplicates for donors 1, 2, and 3. (D) Enhanced cytolysis of 293T-AICL by alloreactive NKp80+ CD8+ T cells. NKp80+ and NKp80− subsets of effector memory T cells (CCR7−CD8+CD3+) were sorted with FACS from purified CD8+ cells, cocultured with irradiated 293T-neo for 10 days, and subsequently used as effector cells in chromium release assays with 293T-neo and 293T-AICL, respectively, as target cells.

NKp80-AICL interactions enhance alloreactive CD8 T-cell responses. (A, left) 293T-AICL transfectants broadly express AICL at the cell surface and bind soluble NKp80. Staining of 293T-AICL with anti-AICL mAb 7F12 (black histogram) and isotype control (dashed line) overlaid with staining of 293T-neo (7F12 [gray histogram]; isotype control [dotted line]). (A, right) Tetramers of soluble NKp80 ectodomains bind to 293T-AICL (black histogram) but not to 293T-neo (gray histogram). (B,C) Purified CD8+ cells were cocultured with irradiated 293T-neo or 293T-AICL in the presence of IL-2 and, where indicated, of anti-NKp80 5D12 or control IgG1. After 8 days of coculture, cells were restimulated with 293T-neo or 293T-AICL cells and CD107a expression of CD3+ cells was analyzed with flow cytometry. (B) Representative dot plots for donor 1. (C) Means and standard deviations of triplicates for donors 1, 2, and 3. (D) Enhanced cytolysis of 293T-AICL by alloreactive NKp80+ CD8+ T cells. NKp80+ and NKp80− subsets of effector memory T cells (CCR7−CD8+CD3+) were sorted with FACS from purified CD8+ cells, cocultured with irradiated 293T-neo for 10 days, and subsequently used as effector cells in chromium release assays with 293T-neo and 293T-AICL, respectively, as target cells.

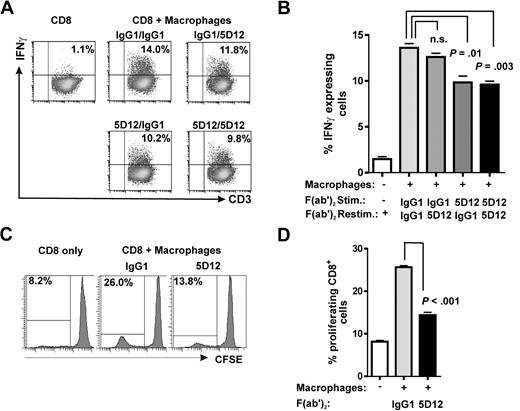

To further address a contribution of NKp80-AICL interaction to the cytotoxic effector responses of T cells, we FACS-sorted NKp80+ and NKp80− subsets of effector memory CD8 T cells from purified CD8+ T cells, stimulated these in vitro with 293T-neo cells and, subsequently assayed their cytotoxic capacity against 293T transfectants in chromium release assays. We observed that NKp80+ T cells were more potent killers compared with NKp80− T cells and that NKp80+ cells lysed 293T-AICL cells more efficiently compared with 293T-neo cells (Figure 6D). Next, we assessed a contribution of NKp80 in alloresponses of CD8 T cells to macrophages that endogenously express AICL.15 Purified CD8+ cells were stimulated with in vitro–generated allogeneic macrophages and assayed for IFN-γ secretion upon restimulation with these allogeneic macrophages (Figure 7A,B). Frequencies of IFN-γ–secreting CD8 T cells were significantly reduced when NKp80 engagement was blocked during the stimulation by the addition of anti-NKp80 F(ab′)2 compared with the control. However, NKp80 blockade had no significant effect when anti-NKp80 F(ab′)2 were added only during the IFN-γ secretion assay. Finally, we examined the impact of NKp80 on the proliferation of CD8 T cells in cocultures with allogeneic macrophages. Here, addition of anti-NKp80 F(ab′)2, but not of control IgG1 F(ab′)2, resulted in a significant impairment of CD8 T-cell proliferation, suggesting that NKp80 is contributing to the expansion of alloreactive CD8 effector memory T cells (Figure 7C,D).

NKp80 stimulates alloresponses of CD8 T cells toward macrophages. (A,B) Purified CD8+ T cells were stimulated with irradiated allogeneic macrophages for 8 days in the presence of anti-NKp80 (Fab′)2 5D12, or control IgG1 (stimulation) and subsequently, assayed for IFNγ secretion upon restimulation with macrophages. Allogeneic macrophages used for stimulation and restimulation came from the same culture. Dot plots (A) and mean and standard deviations of triplicates (B) for one representative of 3 experiments are shown. (C,D) CFSE-labeled, purified CD8 T cells were cocultured with allogeneic macrophages for 8 days in the presence of anti-NKp80 (Fab′)2 5D12 or control IgG1 and frequencies of proliferating cells analyzed by flow cytometry. Histogram plots (C) and means and standard deviations of triplicates (D) for one representative of 3 experiments are shown. Purified CD8 T cells used for experiments shown in panels A through D were approximately 15%-20% NKp80+.

NKp80 stimulates alloresponses of CD8 T cells toward macrophages. (A,B) Purified CD8+ T cells were stimulated with irradiated allogeneic macrophages for 8 days in the presence of anti-NKp80 (Fab′)2 5D12, or control IgG1 (stimulation) and subsequently, assayed for IFNγ secretion upon restimulation with macrophages. Allogeneic macrophages used for stimulation and restimulation came from the same culture. Dot plots (A) and mean and standard deviations of triplicates (B) for one representative of 3 experiments are shown. (C,D) CFSE-labeled, purified CD8 T cells were cocultured with allogeneic macrophages for 8 days in the presence of anti-NKp80 (Fab′)2 5D12 or control IgG1 and frequencies of proliferating cells analyzed by flow cytometry. Histogram plots (C) and means and standard deviations of triplicates (D) for one representative of 3 experiments are shown. Purified CD8 T cells used for experiments shown in panels A through D were approximately 15%-20% NKp80+.

Discussion

Previous studies addressing expression and function of NKp80 focused on NK cells of humans and nonhuman primates.15,18,33,34 In this study, we scrutinized human αβ T cells for expression and functionality of NKp80. We observed that NKp80 is virtually absent from CD4 T cells and naive CD8 T cells but is expressed by a subset of effector memory CD8 T cells, with most of these representing terminally differentiated TEMRA cells devoid of CD27 and CD28 surface expression. NKp80-expressing CD8 T cells are distinguished by their abundant expression of cytotoxic effector molecules, such as perforin and granzyme B, and an enhanced capacity to degranulate and secrete IFN-γ. In line with their more differentiated phenotype, NKp80+ T cells contain more IFN-γ–secreting cells and less IL-2–secreting cells compared with NKp80− effector memory T cells, although the frequencies of cells secreting multiple cytokines (ie, IL-2, TNF, IFN-γ) did not significantly differ between these 2 subsets. Although NKp80+ T cells belong to the differentiated TEMRA subset, they do not comprise more putatively “exhausted” PD-1+ cells than NKp80− effector memory T cells.

Transcriptional and flow cytometric profiling of NKp80+ effector memory CD8 T cells revealed characteristics well in accord with an “inflammatory” character of these T cells, including the enhanced expression of adhesion molecules, chemokine receptors, and cytotoxic effector molecules known to be present in T cells prone to migrate into inflamed tissue sites.35,36 For example, NKp80+ CD8 T cells express high levels of TL1A/VEGI, which is known to augment IFNγ and GM-CSF production in synergy with the monokines IL-12 and IL-18.37 NKp80+ cells also express increased levels of the dendritic cell (DC)–associated integrin CD11c. Expansion of CD11c+CD8+ T cells was recently described in mice treated with anti-4-1BB mAb.38 Increased expression of PECAM-1 and CD99 on NKp80+ T cells also is indicative of an increased tendency to extravasate and migrate into sites of inflammation.27 Transcripts for integrin β7, which is important for migration to mucosal tissue, are also increased in NKp80+ cells.36 A recent study demonstrated that in mice, effector T cells can enter reactive lymph nodes in a CCR7- and CD62L-independent manner where they kill dendritic cells.35 LFA-1 and ligands of endothelial selectins such as PSGL-1, which are expressed at higher levels on NKp80+ T cells, are thought to facilitate the entry of CCR7− T cells into reactive lymph nodes.35,39

Surprisingly, we also detected a small population of 4-1BBL–expressing cells among NKp80+ effector memory T cells. To the best of our knowledge, expression of 4-1BBL has not yet been reported for human T cells but rather is considered to be mostly restricted to activated antigen-presenting cells such as monocytes, DC, and B cells, where it stimulates activated T cells via 4-1BB.40

NKp80+ T cells also greatly express other NK receptors. Previous reports had already shown that many effector CD8 T cells up-regulate the expression of NK receptors, such as CD94/NKG2A, members of the mouse Ly49 and human KIR families, and KLRG1,6,9,10 which we also find coexpressed by most NKp80+ T cells. However, in many cases, the functional consequences of expression of these NK receptors on CD8 effector T cells remain unclear. This is different for NKG2D, which has been shown to promote effector responses of human and mouse CD8 T cells.12-14 A recent publication demonstrated that certain CD8 T cells are “reprogrammed” to behave like NK cells in celiac disease (CD)8 and can be activated via NKG2D without “signal 1” being provided by the T-cell receptor. Interestingly, that study also reported that levels of NKp80 transcripts are approximately 11-fold greater in NKG2C+ peripheral blood CTL of patients with CD.8 In contrast to the NK receptors NKp44 and NKp46, which are expressed on CD8 T cells of patients with CD but are absent on T cells of healthy donors, NKp80 is expressed constitutively on a subset of effector memory CD8 T cells. Effector memory CD8 T cells were previously reported to express NKR-P1A receptors either at intermediate or high levels.41 We now observed that strong expression of NKp80 is associated with an intermediate (or absent) expression of NKR-P1A and vice versa. In fact, there are only very few cells that strongly express both NKp80 and NKR-P1A, which may indicate that there is a mechanism/factor limiting strong coexpression of these KLR that are encoded in the same subregion of the NKC, that engage related ligands (AICL/CLEC2B vs LLT1/CLEC2D), share a structurally related ectodomain, and yet mediate opposing functions (activation vs inhibition).15,42-44

With regard to function of NKp80, we show here that crosslinking of NKp80 (in combination with engagement of CD3) strongly increased the fraction of responding effector memory CD8 T cells. Further, NKp80 engagement by AICL-expressing allogeneic cells markedly augmented effector responses of CD8 T cells, demonstrating that NKp80 can stimulate the responsiveness of effector memory CD8 T cells when they encounter AICL-expressing cells. We observed enhanced NKp80-dependent alloresponses not only when CD8 T cells were stimulated with AICL-transfected cells but also when cocultured with allogeneic macrophages that endogenously express AICL.15 Our data from NKp80 blockade of IFNγ-secretion and proliferation assays suggest that NKp80 enhances alloresponses to macrophages primarily by expanding alloreactive T cells. Although NKp80+ T cells poorly proliferate upon exposure to cytokines, NKp80 engagement appears to promote their expansion in an alloreactive setting.

NKp80 is expressed by a high percentage of HCMV-pp65-specific CD8 T cells in accord with their TEMRA phenotype. Because myeloid cells are a major reservoir of HCMV,45,46 NKp80 expression on HCMV-specific T cells may contribute to containment of HCMV infection by eliminating infected cells. In this context, it will also be of interest to investigate whether HCMV encodes proteins allowing immune escape from NKp80, such as recently reported for KSHV.47 Alternatively, NKp80-AICL interaction may allow for mutual activation of effector T cells and myeloid cells under inflammatory conditions analogous to our observations with NK cells15 and thereby augment or exacerbate ongoing immune reactions. Activation of memory CD8 T cells by recruited dendritic cells in inflamed tissue has recently been reported48 and NKp80+ T cells express high levels of the cytokine TL1A which was reported to support maturation of DC.49

In summary, we demonstrate here that the stimulatory NK receptor NKp80 is expressed on a subset of effector memory CD8 T cells that are characterized by high responsiveness and an “inflammatory” NK-like phenotype. Further, we demonstrate that NKp80 stimulation augments CD8 T-cell responses toward AICL-expressing cells. Our findings highlight a novel facet of effector T cells that may be important for their functional interaction with myeloid cells in the course of immune responses and should be addressed in future studies.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrea Weltgen and Wiebke Ruschmeier for excellent technical assistance, Mathias Schuler for help with analysis of microarray data, Steffen Walter and Stefan Stevanovic for HLA-A2 tetramers, Hanspeter Pircher for the KLRG1-specific antibody, and Rene van Lier and Ineke ten Berge for support.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grants SFB 685/A1 to A.S. and SFB 685/B4 to G.P. and a stipend, GK794, to S. Kuttruff).

Authorship

Contribution: S. Kuttruff designed and performed most experiments, analyzed and interpreted resulting data, and participated in writing the manuscript; S. Koch performed and evaluated MHC tetramer stainings; A.K. established 293T-AICL cells; G.P. and H.-G.R. contributed to experimental design and manuscript writing; and A.S. designed research, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.S. filed a patent application on NKp80/AICL. All other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Alexander Steinle, Interfakultäres Institut für Zellbiologie, Abteilung Immunologie, Auf der Morgenstelle 15, 72076 Tübingen, Germany; e-mail: alexander.steinle@uni-tuebingen.de.

![Figure 6. NKp80-AICL interactions enhance alloreactive CD8 T-cell responses. (A, left) 293T-AICL transfectants broadly express AICL at the cell surface and bind soluble NKp80. Staining of 293T-AICL with anti-AICL mAb 7F12 (black histogram) and isotype control (dashed line) overlaid with staining of 293T-neo (7F12 [gray histogram]; isotype control [dotted line]). (A, right) Tetramers of soluble NKp80 ectodomains bind to 293T-AICL (black histogram) but not to 293T-neo (gray histogram). (B,C) Purified CD8+ cells were cocultured with irradiated 293T-neo or 293T-AICL in the presence of IL-2 and, where indicated, of anti-NKp80 5D12 or control IgG1. After 8 days of coculture, cells were restimulated with 293T-neo or 293T-AICL cells and CD107a expression of CD3+ cells was analyzed with flow cytometry. (B) Representative dot plots for donor 1. (C) Means and standard deviations of triplicates for donors 1, 2, and 3. (D) Enhanced cytolysis of 293T-AICL by alloreactive NKp80+ CD8+ T cells. NKp80+ and NKp80− subsets of effector memory T cells (CCR7−CD8+CD3+) were sorted with FACS from purified CD8+ cells, cocultured with irradiated 293T-neo for 10 days, and subsequently used as effector cells in chromium release assays with 293T-neo and 293T-AICL, respectively, as target cells.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/113/2/10.1182_blood-2008-03-145615/6/m_zh80010928790006.jpeg?Expires=1769171957&Signature=j1gU~UvjKOwzC-U9bHGyTpa6s9ckijKM7KDGyIFrnUp2YqpB83U1tX-amL17cIPByY9UoRvCuvz8Ij~Nf8Euaz2BmsSr9VJKL2O5OY1y5pEHx-WJn0ryus8gPJpLJXkj53qFyxM1IPUmvtrjMevD9ImIX2qcGytT-3bnbLIar86ZiKWu05-M3-CsbM5FsDU-3A1-du2uF1AvTIPrDXEmr9VpU8udM5okoloC0W51CngES3sKhUm~x~0FjU45ijAUetnCXa3FIxyrOQEzvd1V1mPP~W4UNY8WmwAiN4Fs7bMyPl63GkEfmKnMAPGV096YKuGLfq7dhQvdSr~PR88rlA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

). Mean values of data are shown with error bars indicating standard deviation. For analysis of NKR-P1A/CD161 in (D), only MFI of the CD161+ subpopulation were considered. (F) Coexpression of PD-1 and KLRG1, respectively, with NKp80 on effector memory CD8 T cells (CCR7− CD8+ αβ TCR+) of 2 representative donors.

). Mean values of data are shown with error bars indicating standard deviation. For analysis of NKR-P1A/CD161 in (D), only MFI of the CD161+ subpopulation were considered. (F) Coexpression of PD-1 and KLRG1, respectively, with NKp80 on effector memory CD8 T cells (CCR7− CD8+ αβ TCR+) of 2 representative donors.

![Figure 6. NKp80-AICL interactions enhance alloreactive CD8 T-cell responses. (A, left) 293T-AICL transfectants broadly express AICL at the cell surface and bind soluble NKp80. Staining of 293T-AICL with anti-AICL mAb 7F12 (black histogram) and isotype control (dashed line) overlaid with staining of 293T-neo (7F12 [gray histogram]; isotype control [dotted line]). (A, right) Tetramers of soluble NKp80 ectodomains bind to 293T-AICL (black histogram) but not to 293T-neo (gray histogram). (B,C) Purified CD8+ cells were cocultured with irradiated 293T-neo or 293T-AICL in the presence of IL-2 and, where indicated, of anti-NKp80 5D12 or control IgG1. After 8 days of coculture, cells were restimulated with 293T-neo or 293T-AICL cells and CD107a expression of CD3+ cells was analyzed with flow cytometry. (B) Representative dot plots for donor 1. (C) Means and standard deviations of triplicates for donors 1, 2, and 3. (D) Enhanced cytolysis of 293T-AICL by alloreactive NKp80+ CD8+ T cells. NKp80+ and NKp80− subsets of effector memory T cells (CCR7−CD8+CD3+) were sorted with FACS from purified CD8+ cells, cocultured with irradiated 293T-neo for 10 days, and subsequently used as effector cells in chromium release assays with 293T-neo and 293T-AICL, respectively, as target cells.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/113/2/10.1182_blood-2008-03-145615/6/m_zh80010928790006.jpeg?Expires=1769171958&Signature=ZUEmqBjYp9ng8te1QrAE99uT2MqFQ2xPKZMkum8wl3d648qjDx8AhY357YDNK0E9MwfJOe1~EgQNs4CuLeTpl9DXs0maKQ3JDTYzgClmm8PwfzP9gdT1TGm84rDm8cFHlpZUXNXoFrpgHSgx31b4Ub55yCPmEj8hZPflQJ1Y8T10BStCr2Z4geAjJITmySbMjNm1SQFtQiwfFi1KMbhOBlvP8jSZOGSlS11ic~DuIIE1az1wPj4VcVBM1sJ5G7c6W~Sk7H2utSOKtKdcooomwvnP6lnHtLnjA3ltCJIU7-rbh-PzqlcsNJymjptLRL-yuRXC5ytHG5Z7YWpT0eRZlg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)