Key Points

APA is associated with LM gain with significant improvement in all physical tests.

APA is more efficient in case of shorter neutropenia or younger age.

Visual Abstract

Adapted physical activity (APA) has become an essential asset in the care of patients with cancer. Although its positive impact has mainly been studied regarding quality of life, few studies have focused on changes in lean mass (LM) and its determinants. This study reports the results of an APA program for inpatients in the hematology department of Nice University Hospital (France). Body composition analyses and physical tests were performed at admission and discharge. A total of 123 patients were analyzed with relative LM gain as the primary outcome. Over a median hospitalization duration of 33 days, the average observed LM variation was +0.32 kg (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.15-0.50), representing an average relative gain of +0.64% (95% CI, 0.28-1.01), with significant improvement in all physical tests. In multivariate analyses, a younger age and a shorter neutropenia duration were best predictive of LM gain. We show here that it is possible to maintain LM during hospitalization for hematology patients undergoing chemotherapy in a real-life setting.

Introduction

Adapted physical activity (APA) is a concept dating back to the 1970s, developed to become an important asset among supportive care for patients with chronic diseases. It differs from regular physical exercise by placing a special emphasis on the interests and capabilities of individuals with limiting conditions, with the goal of muscle strengthening and improving overall physical condition. Such exercise must be regular, progressive, and patient specific.1,2

Typically, oncology patients can greatly benefit from APA, because they face disease-specific restrictions and treatment-related toxicities, which limit their physical abilities. Patients treated for hematological malignancies are subject to additional constraints such as isolation, repeated transfusions, severe infections, and bleeding risk. In addition, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), which is the only curative option for many hematological malignancies, remains associated with high and prolonged toxicities despite improvements over the years.3 For all these reasons, the American College of Sports Medicine recommends for patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT “moderate-intensity exercise over short periods with increased frequency and gradual progression.”4 The largest body of evidence regarding the positive impact of APA on patients with neoplasia involves reducing disease-related symptoms, improving health-related quality of life, and physical functions.5,6 However, to date, most of the available literature focuses on solid tumors and very few publications study APA in hematology.7

Several authors have reported the negative impact of sarcopenia in oncology as it is a common issue among patients and because it has been identified as a major determinant of health-related quality of life.8 Sarcopenia is defined by a progressive and generalized loss of skeletal muscle mass (MM) and strength, leading to impaired physical performance. It is to be distinguished from cachexia (which is a multifactorial syndrome associated with underlying disease and systemic inflammation, resulting in sarcopenia and adipopenia), and from malnutrition (which is primarily based on inadequate nutrient intake or absorption).9,10 In a recent study involving 126 in-hospital patients with myeloid neoplasms, it was found that a weight loss would occur over hospitalization primarily in lean mass (LM) and despite nutritional support. This LM loss co-occurred with a decrease in muscle function measured with hand grip test (HGT).11 Moreover, optimizing the physical and nutritional parameters of patients with acute myeloid leukemia could help predict the risk of complications, and improving these parameters may lead to shorter hospital stays and better survival.11-14 Still, few authors analyzed specifically the beneficial impact of physical exercise programs on LM gain in the setting of oncohematology and the determinants of this gain have been poorly studied.15

LM is frequently used interchangeably with MM. LM (or fat-free mass) is composed of body water, MM, and bone mass.16 The MM itself can be assessed by different methods: computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (which are considered gold-standard methods that measure MM by cross-sectional scans), dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (which measures MM by evaluating tissue attenuation of X-rays), and bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA). It has been shown that BIA correlates well with other methods, such as X-ray absorptiometry, to determine body composition.17,18 This has been recommended by the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP), the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia, the Foundation for National Institute of Health Sarcopenia Project, and the Korean Working Group on Sarcopenia as an accurate method for detecting low MM and sarcopenia. Additionally, these groups incorporated muscular function to the definition of sarcopenia, using screening tests such as the HGT and the chair stand test to help screening for sarcopenia.19-22

In this context, we conducted a prospective study that sets relative LM gain, as measured by BIA, as the primary outcome and aimed at identifying the determinants of this gain during hospitalization in a population of hematology patients receiving chemotherapy and benefiting from regular APA interventions associated with standard supportive cares.

Materials and methods

This study involved patients hospitalized in the hematology department at the Nice University Hospital in France, who benefited from face-to-face supervised APA intervention led by a certified APA instructor.

The intervention was proposed as current practice to all hospitalized patients and consisted of 3 moderate-intensity sessions per week, lasting between 20 and 30 minutes. Exercises were inspired by gymnastics, yoga, and Pilates, and were focused on targeting the body’s deep muscles to improve tone and balance with the use of posture maintenance, movement repetition and light weights (1.5 kg) for the upper body. The intensity of effort was aimed at being moderate, and sessions were postponed after transfusion when hemoglobin was <8 g/dL (except for patients with cardiovascular diseases, for whom the threshold was 9 g/dL) or when platelet count was <10 × 109/L (except for patients receiving antiplatelet or anticoagulant treatment, for whom the threshold was 50 × 109/L). Each patient was encouraged to use a bicycle and weights in their room whenever they wanted outside of sessions. Other supportive cares included nutritional support, dietetic consultation, psychological evaluation, and physiotherapy.

Patients were recruited consecutively from September 2019 to February 2023, and there were no exclusion criteria. Consent was provided by all patients before starting the program. Each patient agreed to be evaluated at the beginning and at the end of their hospitalization. Body composition was measured using BIA with an individual in-room impedance meter (Tanita model BC545N, with an error of 100 g). This model was previously used in several publications.23,24 Body mass index, fat mass percentage, and LM (corresponding here to “fat-free mass” excluding bone mass) were reported. The number of patients who did not consent to the APA intervention and the reasons for refusal were not collected. Patients without a discharge assessment, or whose discharge assessments corresponded to a different hospitalization, and those with a too-short care period (<14 days), were excluded from the statistical analysis.

Fatigue level was systematically evaluated using the Pichot fatigue scale. Fatigue variation during hospitalization (referred to as “fatigue delta” in the statistics) was calculated as fatigue level at end of intervention minus fatigue level at start of the intervention. Motivation level, pain level, and effort intensity were self-assessed using numerical scales from 0 to 10. Patients were also asked about their physical activity habits (hours of practice per week before disease diagnosis). Motor function was assessed at the beginning and at the end of hospitalization using the following tests on the dominant and nondominant limbs: HGT, arm curl test, one leg stance test (OLST) and 30-second chair stand test (30SCT). The OLST realization was limited to 31 seconds. Additional variables were retrospectively extracted from patient records, including performance status, severe neutropenia duration (defined as absolute neutrophil count of <0.5 × 109/L), intensive chemotherapy regimen (defined by an expected duration of severe neutropenia of >7 days), occurrence of severe sepsis, and admission to intensive care unit during hospitalization (excluding admission for hyperleukocytic acute leukemia [AL]). Treatment failure was defined as persistent disease or graft rejection after chemotherapy or transplantation. Pretreatment paraclinical evaluations were documented: left ventricular ejection fraction, carbon monoxide diffusion capacity, and presence of obstructive ventilatory disorder. Artificial nutrition did not include oral nutritional complements. The use of artificial nutrition was reported, as well as clinical malnutrition according to the Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition criteria.25 For patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT, presence and grade of acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and disease status at the time of transplant (remission or not) were also reported, using the MAGIC score for acute GVHD.26

All statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.4.0. Continuous variables were tested for normality. Mean gains in parameters were compared with the null mean using Student t test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Univariate analyses for predictors of LM gain were performed using simple linear regression for quantitative variables and Student t test for qualitative variables, with relative LM gain as the reference value and a significance threshold of 5% for the α risk. Relative LM variation was expressed in percentage, using the formula ) to account for interindividual differences in patients morphology. Variables previously identified as significant in univariate analyses were compiled in a generalized linear model for multivariate testing, and data from the multivariate model were standardized using the “scale” function in R. In an ad hoc analysis, the same method was applied to the subpopulation of patients hospitalized for allogeneic HSCT.

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This human study was approved by the Ministère de l'enseignement supérieur et de la recherche (approval reference number: AC-2018-3110). All adult participants provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

Results

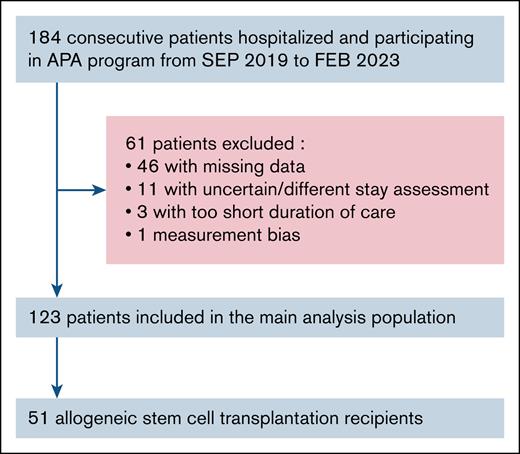

A total of 184 patients hospitalized in the oncohematology department of the Nice University Hospital were consecutively recruited from September 2019 to February 2023. Among them, 61 were excluded from the statistical analysis: 46 secondary to missing discharge assessment and/or BIA data, 14 secondary to uncertain or too-short duration-of-care period. One more patient was excluded because the BIA data were deemed incompatible with a physiological gain. Therefore, 123 patients remained in the final analysis (Figure 1). A comparative analysis with the 61 patients excluded from the main analysis is available in supplemental Table 1 and did not identify a significant difference.

Flowchart of hospitalized patients included in the APA program. FEB, February; SEP, September.

Flowchart of hospitalized patients included in the APA program. FEB, February; SEP, September.

Characteristics of the population are reported in Table 1. The median age was 57 years (range, 18-87) and 28.5% (n = 35/123) of the patients were aged >65 years. The male-to-female ratio was 1.28. The median performance status was 1 (range, 0-3). The median number of previous lines of treatment was 1 (range, 0-6). The median body mass index was 24.25 (range, 15.6-41.1), 11.4% of patients were obese, whereas 39.8% of the population exhibited clinical malnutrition and 66.7% of patients received artificial nutrition during hospitalization. The most common pathologies were AL for 45.5% of patients, followed by myelodysplastic (MDS) and/or myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) and lymphoma. Allogeneic HSCT was the most common reason for hospitalization (n = 51/123 [41.46%]), 97.6% of patients received chemotherapy, and 77.2% received intensive chemotherapy. Main events of interest that occurred during hospitalizations are reported in supplemental Table 2. There was no report of adverse events related to APA in the retrospective review of patient files.

Baseline characteristics of the study population (n = 123 patients)

| General demographic and clinical characteristics | |

| Median age (range), y | 57 (18-87) |

| Age ≥65 years, % | 28.5 |

| Sex ratio, (M/F, n) | 1.28 (69/54) |

| Median performance status (0/1/2/3, %) | 1 (49.4/43.0/6.3/1.3) |

| Median number of previous lines (range), n | 1 (0-6) |

| Professional status, active/retired/other, % | 57.7/35.0/7.3 |

| Practice of physical activity (<3 hours/>3 hours a week), % | 79.7/20.3 |

| Pathology, n | |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 56 |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 14 |

| Lymphoma (high/low grade) | 16 (14/2) |

| Multiple myeloma | 4 |

| Other myeloid neoplasms (MDS and/or MPN) | 27 (14/13) |

| Other (aplastic anemia/hemoglobinopathy) | 6 (5/1) |

| Reason for hospitalization, n | |

| Chemotherapy (induction/salvage/consolidation) | 43 (27/6/10) |

| Allogeneic HSCT | 51 |

| Autologous HSCT | 5 |

| CAR T cell | 10 |

| Other (microtransplant, immunosuppressant, complication) | 14 |

| Health and physical metrics | |

| Median BMI (range), kg/m2 | 24.25 (15.6-41.1) |

| Obesity, % | 11.4 |

| Median fat mass (range), % of body weight | 20.1 (5.4-42.2) |

| Median LM (range), kg | 53.4 (31.1-88.5) |

| Median albumin level (range), g/L | 33.2 (18.0-46.0) |

| Median prealbumin level(range), g/L | 0.228 (0.073-0.432) |

| Malnutrition, % | 39.8 (n = 37/93) |

| Median fatigue level (interquartile range) | 7 (4-11) |

| Median motivation level (interquartile range) | 9 (8-10) |

| Median pain level (interquartile range) | 0 (0-3) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction of <50%, % | 5.0 (n = 5/100) |

| Diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide of <60%, % | 15.8 (n = 13/82) |

| Obstructive respiratory disorder, % | 15.5 (n = 13/84) |

| General demographic and clinical characteristics | |

| Median age (range), y | 57 (18-87) |

| Age ≥65 years, % | 28.5 |

| Sex ratio, (M/F, n) | 1.28 (69/54) |

| Median performance status (0/1/2/3, %) | 1 (49.4/43.0/6.3/1.3) |

| Median number of previous lines (range), n | 1 (0-6) |

| Professional status, active/retired/other, % | 57.7/35.0/7.3 |

| Practice of physical activity (<3 hours/>3 hours a week), % | 79.7/20.3 |

| Pathology, n | |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 56 |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 14 |

| Lymphoma (high/low grade) | 16 (14/2) |

| Multiple myeloma | 4 |

| Other myeloid neoplasms (MDS and/or MPN) | 27 (14/13) |

| Other (aplastic anemia/hemoglobinopathy) | 6 (5/1) |

| Reason for hospitalization, n | |

| Chemotherapy (induction/salvage/consolidation) | 43 (27/6/10) |

| Allogeneic HSCT | 51 |

| Autologous HSCT | 5 |

| CAR T cell | 10 |

| Other (microtransplant, immunosuppressant, complication) | 14 |

| Health and physical metrics | |

| Median BMI (range), kg/m2 | 24.25 (15.6-41.1) |

| Obesity, % | 11.4 |

| Median fat mass (range), % of body weight | 20.1 (5.4-42.2) |

| Median LM (range), kg | 53.4 (31.1-88.5) |

| Median albumin level (range), g/L | 33.2 (18.0-46.0) |

| Median prealbumin level(range), g/L | 0.228 (0.073-0.432) |

| Malnutrition, % | 39.8 (n = 37/93) |

| Median fatigue level (interquartile range) | 7 (4-11) |

| Median motivation level (interquartile range) | 9 (8-10) |

| Median pain level (interquartile range) | 0 (0-3) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction of <50%, % | 5.0 (n = 5/100) |

| Diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide of <60%, % | 15.8 (n = 13/82) |

| Obstructive respiratory disorder, % | 15.5 (n = 13/84) |

BMI, body mass index; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; F, female; M, male.

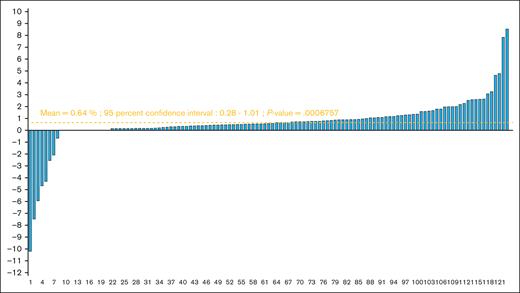

Over a median hospitalization duration of 33 days (range, 14-93), the observed average relative LM gain was 0.64% (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.28-1.01; P = .00068) for the study population (Figure 2). This gain was 0.61% (95% CI, 0.15-1.06) in the subgroup of patients who has received allogeneic HSCT (supplemental Figure 1) and 0.04% (95% CI = −0.67 to 0.74) in the subgroup of patients aged ≥65 years (supplemental Figure 2). Different studied parameters and their evolutions are reported in Tables 2 and 3. The average absolute LM gain among patients was 0.33 kg (95% CI, 0.15-0.50), and the average absolute difference of fat mass percentages was −0.60 (95% CI, −0.75 to −0.43). All physical tests significantly improved compared with their baseline levels and an average reduction of 4.54 points in fatigue level (95% CI, −5.38 to −3.71) was observed. The number of patients with low strength by HGT according to the EWGSOP criteria also decreased (supplemental Table 3).

LM gain (% of original) among 123 hospitalized patients included in the final analysis.

LM gain (% of original) among 123 hospitalized patients included in the final analysis.

Variation of patient parameters during hospitalization

| Body composition and nutritional data . | Start of intervention . | End of intervention . | Variation (gain or loss) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean . | SD . | Mean . | SD . | Mean . | 95% CI . | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.79 | 4.18 | 24.42 | 4.06 | −0.37 | −0.48 to −0.26 |

| Fat mass, % | 20.33 | 9.04 | 19.73 | 8.72 | −0.60 | −0.75 to −0.43 |

| LM, kg | 54.16 | 12.53 | 54.49 | 12.55 | 0.33 | 0.15-0.50 |

| Albumin, g/L | 33.13 | 5.39 | 31.98 | 6.24 | −1.18 | −2.38 to 0.02 |

| Prealbumin, g/L | 0.22 | 0.08 | 0.26 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.02-0.06 |

| Body composition and nutritional data . | Start of intervention . | End of intervention . | Variation (gain or loss) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean . | SD . | Mean . | SD . | Mean . | 95% CI . | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.79 | 4.18 | 24.42 | 4.06 | −0.37 | −0.48 to −0.26 |

| Fat mass, % | 20.33 | 9.04 | 19.73 | 8.72 | −0.60 | −0.75 to −0.43 |

| LM, kg | 54.16 | 12.53 | 54.49 | 12.55 | 0.33 | 0.15-0.50 |

| Albumin, g/L | 33.13 | 5.39 | 31.98 | 6.24 | −1.18 | −2.38 to 0.02 |

| Prealbumin, g/L | 0.22 | 0.08 | 0.26 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.02-0.06 |

| Exercise-related data . | Start of intervention . | End of intervention . | Variation (gain or loss) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median . | Q1; Q3 . | Median . | Q1; Q3 . | Mean . | 95% CI . | |

| Pain | 1.26 | 0; 3 | 0.32 | 0; 0 | −0.95 | −1.33 to −0.56 |

| Fatigue | 8.29 | 4; 11.5 | 3.75 | 1; 6 | −4.54 | −5.38 to −3.71 |

| Effort intensity | 5 | 4; 5 | 5 | 4; 5 | −0.29 | −0.54 to −0.05 |

| Exercise-related data . | Start of intervention . | End of intervention . | Variation (gain or loss) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median . | Q1; Q3 . | Median . | Q1; Q3 . | Mean . | 95% CI . | |

| Pain | 1.26 | 0; 3 | 0.32 | 0; 0 | −0.95 | −1.33 to −0.56 |

| Fatigue | 8.29 | 4; 11.5 | 3.75 | 1; 6 | −4.54 | −5.38 to −3.71 |

| Effort intensity | 5 | 4; 5 | 5 | 4; 5 | −0.29 | −0.54 to −0.05 |

BMI, body mass index; Q1/Q3, quartile 1/3 (interquartile range); SD, standard deviation.

Variation of patient physical test results during hospitalization

| . | Start of intervention . | End of intervention . | Variation (gain) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean . | SD . | Mean . | SD . | Mean . | 95% CI . | |

| HGT (dominant hand, women),∗ kg | 20.98 | 5.24 | 21.87 | 5.06 | 0.89 | 0.55-1.22 |

| HGT (dominant hand, men),∗ kg | 36.31 | 9.26 | 37.43 | 9.25 | 1.12 | 0.68-1.56 |

| HGT (nd hand, women),∗ kg | 19.02 | 5.32 | 19.98 | 5.22 | 0.96 | 0.70-1.21 |

| HGT (nd hand, men),∗ kg | 34.33 | 9.01 | 35.48 | 8.93 | 1.15 | 0.82-1.48 |

| ACT (dominant arm), n | 20.66 | 6.18 | 22.85 | 8.86 | 2.19 | 1.77-2.61 |

| ACT (nd arm), n | 20.20 | 6.44 | 22.41 | 6.41 | 2.21 | 1.75-2.68 |

| 30SCT (women),∗ n | 13.81 | 5.18 | 15.48 | 4.97 | 1.67 | 1.29-2.04 |

| 30SCT (men),∗ n | 14.88 | 6.05 | 16.77 | 5.64 | 1.88 | 1.49-2.28 |

| . | Start of intervention . | End of intervention . | Variation (gain) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean . | SD . | Mean . | SD . | Mean . | 95% CI . | |

| HGT (dominant hand, women),∗ kg | 20.98 | 5.24 | 21.87 | 5.06 | 0.89 | 0.55-1.22 |

| HGT (dominant hand, men),∗ kg | 36.31 | 9.26 | 37.43 | 9.25 | 1.12 | 0.68-1.56 |

| HGT (nd hand, women),∗ kg | 19.02 | 5.32 | 19.98 | 5.22 | 0.96 | 0.70-1.21 |

| HGT (nd hand, men),∗ kg | 34.33 | 9.01 | 35.48 | 8.93 | 1.15 | 0.82-1.48 |

| ACT (dominant arm), n | 20.66 | 6.18 | 22.85 | 8.86 | 2.19 | 1.77-2.61 |

| ACT (nd arm), n | 20.20 | 6.44 | 22.41 | 6.41 | 2.21 | 1.75-2.68 |

| 30SCT (women),∗ n | 13.81 | 5.18 | 15.48 | 4.97 | 1.67 | 1.29-2.04 |

| 30SCT (men),∗ n | 14.88 | 6.05 | 16.77 | 5.64 | 1.88 | 1.49-2.28 |

| . | Median . | Q1; Q3 . | Median . | Q1; Q3 . | Mean . | 95% CI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OLST (dominant leg), s | 21.25 | 10.5; 31 | 23.80 | 15; 31 | 2.55 | 1.65-3.45 |

| OLST (nd leg), s | 21.18 | 10; 31 | 24.11 | 16.5; 31 | 2.93 | 1.97-3.89 |

| . | Median . | Q1; Q3 . | Median . | Q1; Q3 . | Mean . | 95% CI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OLST (dominant leg), s | 21.25 | 10.5; 31 | 23.80 | 15; 31 | 2.55 | 1.65-3.45 |

| OLST (nd leg), s | 21.18 | 10; 31 | 24.11 | 16.5; 31 | 2.93 | 1.97-3.89 |

ACT, arm curl test; BMI, body mass index; FNIHSP, Foundation for National Institute of Health Sarcopenia Project; KWGS, Korean Working Group on Sarcopenia; nd, nondominant; Q1/Q3, quartile 1/3 (interquartile range); SD, standard deviation.

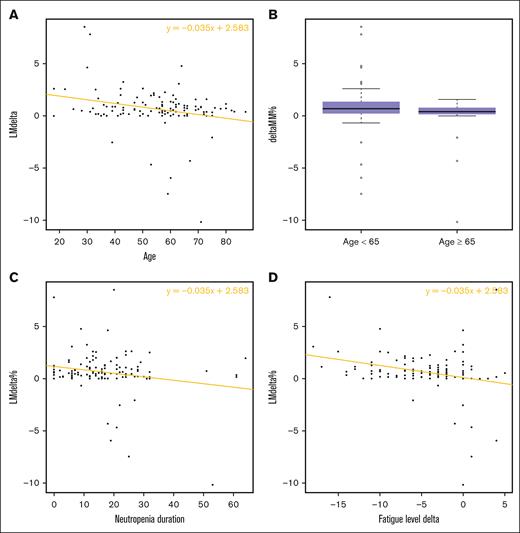

Variables tested in univariate analysis for their relationship with relative LM gain are listed in Tables 4 and 5. There was a significant difference in relative LM gain between patients aged <65 years and those aged ≥65 years (0.89% vs 0.04%, respectively; P = .041). Subject-related variables that had a statistically significant correlation with relative LM gain were age (negatively, P = .0044), initial fatigue level (positively, P = .020), increase in fatigue over hospitalization (negatively, P = .0028), and neutropenia duration (negatively, P = .024; Figure 3). In contrast, hospitalization duration did not influence this gain significantly (P = .82). Among reasons for hospitalization, the diagnosis of AL had a positive impact on relative LM gain whereas the diagnosis of MDS and/or MPN had a negative impact (P = .044 and .017, respectively). Variables related to physical tests that were significantly associated with relative LM gain included result of the initial OLST on the dominant limb (positively, P = .049), an improvement of the HGT over hospitalization on both dominant and nondominant limbs (positively, P = .0033 and P = .022, respectively), and an improvement of the 30SCT over hospitalization (positively, P = .045). In multivariate analysis, variables that remained significantly associated with relative LM gain were (1) a short duration of neutropenia and (2) a younger age (Table 6).

Univariate analysis for LM gain in the study population (clinical data)

| . | Linear correlation coefficient . | P value . |

|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.03518 | .004404∗∗ |

| Performance status at admission | 0.04675 | .8882 |

| Number of previous lines | −0.2156 | .20832 |

| Albumin | 0.03009 | .430 |

| Prealbumin | 4.5128 | .0818 |

| Body mass index | −0.01567 | .725 |

| Body fat mass percentage | 0.01179 | .567 |

| Motivation level | 0.1117 | .363 |

| Initial fatigue level | 0.07620 | .0199∗ |

| Initial pain level | 0.001587 | .98548 |

| Perceived effort intensity | −0.003353 | .979 |

| Fatigue Δ | −0.11705 | .00275∗∗ |

| Neutropenia duration | −0.03392 | .024227∗ |

| Hospitalization duration | 0.002952 | .817 |

| . | Linear correlation coefficient . | P value . |

|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.03518 | .004404∗∗ |

| Performance status at admission | 0.04675 | .8882 |

| Number of previous lines | −0.2156 | .20832 |

| Albumin | 0.03009 | .430 |

| Prealbumin | 4.5128 | .0818 |

| Body mass index | −0.01567 | .725 |

| Body fat mass percentage | 0.01179 | .567 |

| Motivation level | 0.1117 | .363 |

| Initial fatigue level | 0.07620 | .0199∗ |

| Initial pain level | 0.001587 | .98548 |

| Perceived effort intensity | −0.003353 | .979 |

| Fatigue Δ | −0.11705 | .00275∗∗ |

| Neutropenia duration | −0.03392 | .024227∗ |

| Hospitalization duration | 0.002952 | .817 |

| . | Difference in relative gain (%) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|

| Age of ≥65 years | 0.89 (n) vs 0.04 (y) | .04061∗ |

| Sex | 0.72 (female) vs 0.58 (male) | .7424 |

| Allogeneic HSCT | 0.67 (n) vs 0.61 (y) | .8653 |

| Intensive chemotherapy | 0.40 (n) vs 0.71 (y) | .5568 |

| AL | −0.20 (n) vs 0.98 (y) | .04356∗ |

| MDS and/or MPN | 0.87 (n) vs -0.17 (y) | .01712∗ |

| Lymphoma | 0.65 (n) vs 0.60 (y) | .8573 |

| Evolutive disease | 0.83 (n) vs 0.47 (y) | .3125 |

| Malnutrition | 0.92 (n) vs 0.47 (y) | .3045 |

| Use of artificial nutrition | 0.62 (n) vs 0.65 (y) | .9458 |

| Obesity | 0.66 (n) vs 0.53 (y) | .5959 |

| Physical activity of >3 h/wk | 0.63 (n) vs 0.69 (y) | .9276 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction of <50% | 0.67 (n) vs 0.47 (y) | .463 |

| Obstructive respiratory disorder | 0.71 (n) vs 0.35 (y) | .259 |

| Diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide of <60% | 0.77 (n) vs −0.13 (y) | .2037 |

| Severe sepsis | 0.70 (n) vs 0.56 (y) | .7158 |

| Intensive care admission | 0.69 (n) vs −1.09 (y) | .5536 |

| Viral infection | 0.80 (n) vs 0.01 (y) | .1999 |

| Invasive fungal infection | 0.64 (n) vs 0.68 (y) | .8913 |

| Mucositis grade ≥3 | 0.65 (n) vs 0.53 (y) | .8474 |

| Treatment failure | 0.69 (n) vs −0.17 (y) | .5974 |

| . | Difference in relative gain (%) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|

| Age of ≥65 years | 0.89 (n) vs 0.04 (y) | .04061∗ |

| Sex | 0.72 (female) vs 0.58 (male) | .7424 |

| Allogeneic HSCT | 0.67 (n) vs 0.61 (y) | .8653 |

| Intensive chemotherapy | 0.40 (n) vs 0.71 (y) | .5568 |

| AL | −0.20 (n) vs 0.98 (y) | .04356∗ |

| MDS and/or MPN | 0.87 (n) vs -0.17 (y) | .01712∗ |

| Lymphoma | 0.65 (n) vs 0.60 (y) | .8573 |

| Evolutive disease | 0.83 (n) vs 0.47 (y) | .3125 |

| Malnutrition | 0.92 (n) vs 0.47 (y) | .3045 |

| Use of artificial nutrition | 0.62 (n) vs 0.65 (y) | .9458 |

| Obesity | 0.66 (n) vs 0.53 (y) | .5959 |

| Physical activity of >3 h/wk | 0.63 (n) vs 0.69 (y) | .9276 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction of <50% | 0.67 (n) vs 0.47 (y) | .463 |

| Obstructive respiratory disorder | 0.71 (n) vs 0.35 (y) | .259 |

| Diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide of <60% | 0.77 (n) vs −0.13 (y) | .2037 |

| Severe sepsis | 0.70 (n) vs 0.56 (y) | .7158 |

| Intensive care admission | 0.69 (n) vs −1.09 (y) | .5536 |

| Viral infection | 0.80 (n) vs 0.01 (y) | .1999 |

| Invasive fungal infection | 0.64 (n) vs 0.68 (y) | .8913 |

| Mucositis grade ≥3 | 0.65 (n) vs 0.53 (y) | .8474 |

| Treatment failure | 0.69 (n) vs −0.17 (y) | .5974 |

n, no; y, yes.

P ≤ .05; ∗∗P ≤ .01.

Univariate analysis for LM gain in the study population (physical tests)

| Test . | Linear correlation coefficient . | P value . |

|---|---|---|

| HGT (dominant hand) | −0.0005862 | .973 |

| HGT (nd hand) | −0.003054 | .860 |

| ΔHGT (dominant hand) | 0.3395 | .00328∗∗ |

| ΔHGT (nd hand) | 0.3556 | .0217∗ |

| ACT (dominant arm) | 0.00121 | .968 |

| ACT (nd arm) | −0.00124 | .966 |

| ΔACT (dominant arm) | 0.08071 | .305 |

| ΔACT (nd arm) | 0.04453 | .5348 |

| OLST (dominant leg) | 0.03266 | .0488∗ |

| OLST (nd leg) | 0.01252 | .444 |

| ΔOLST (dominant leg) | −0.008772 | .81249 |

| ΔOLST (nd leg) | 0.06128 | .0752 |

| 30SCT | 0.04256 | .258 |

| Δ30SCT | 0.2440 | .0454∗ |

| Test . | Linear correlation coefficient . | P value . |

|---|---|---|

| HGT (dominant hand) | −0.0005862 | .973 |

| HGT (nd hand) | −0.003054 | .860 |

| ΔHGT (dominant hand) | 0.3395 | .00328∗∗ |

| ΔHGT (nd hand) | 0.3556 | .0217∗ |

| ACT (dominant arm) | 0.00121 | .968 |

| ACT (nd arm) | −0.00124 | .966 |

| ΔACT (dominant arm) | 0.08071 | .305 |

| ΔACT (nd arm) | 0.04453 | .5348 |

| OLST (dominant leg) | 0.03266 | .0488∗ |

| OLST (nd leg) | 0.01252 | .444 |

| ΔOLST (dominant leg) | −0.008772 | .81249 |

| ΔOLST (nd leg) | 0.06128 | .0752 |

| 30SCT | 0.04256 | .258 |

| Δ30SCT | 0.2440 | .0454∗ |

ACT, arm curl test; nd, nondominant.

P ≤ .05; ∗∗P ≤ .01.

LM gain (% of original) according to main variables. (A) Age, (B) age (dichotomized, <65 year, ≥65 years), (C) neutropenia duration, and (D) fatigue level evolution over hospitalization.

LM gain (% of original) according to main variables. (A) Age, (B) age (dichotomized, <65 year, ≥65 years), (C) neutropenia duration, and (D) fatigue level evolution over hospitalization.

Multivariate analysis for LM gain in the study population

| . | Model parameter . | P value . |

|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.53969 | .006828∗∗ |

| AL | 0.42628 | .051549 |

| MDS and/or MPN | −0.02426 | .910164 |

| Initial fatigue | −0.07740 | .801872 |

| Fatigue Δ | −0.51106 | .104255 |

| Neutropenia duration | −0.57065 | .001322∗∗ |

| ΔHGT (dominant hand) | 0.23881 | .170249 |

| ΔHGT (nd hand) | 0.20220 | .242166 |

| OLST (dominant leg) | 0.18752 | .334147 |

| Δ30SCT | 0.12569 | .493220 |

| . | Model parameter . | P value . |

|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.53969 | .006828∗∗ |

| AL | 0.42628 | .051549 |

| MDS and/or MPN | −0.02426 | .910164 |

| Initial fatigue | −0.07740 | .801872 |

| Fatigue Δ | −0.51106 | .104255 |

| Neutropenia duration | −0.57065 | .001322∗∗ |

| ΔHGT (dominant hand) | 0.23881 | .170249 |

| ΔHGT (nd hand) | 0.20220 | .242166 |

| OLST (dominant leg) | 0.18752 | .334147 |

| Δ30SCT | 0.12569 | .493220 |

nd, nondominant.

P ≤ .05; ∗∗P ≤ .01.

The ad hoc analysis involved 51 patients admitted for allogeneic HSCT. The results of the univariate analysis for this population are grouped in Tables 7 and 8. Factors significantly associated with relative LM gain in this population were diagnosis of AL (positively, P = .0033), MDS and/or MPN (negatively, P = .030), an evolutive disease (not in remission) at the time of transplantation (negatively, P = .030), and an improvement in fatigue level over hospitalization (positively, P = .013). Notably, the occurrence of grade 3 or 4 digestive acute GVHD negatively affected LM gain but this result did not meet statistical significance (0.78 [absence] vs −0.21 [presence]; P = .3742). Regarding physical tests, an improvement over hospitalization in all patients had a significant positive association with relative LM gain. However, in the multivariate analysis no variable was significantly predictive of this gain.

Univariate analysis for gain of LM among patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT (clinical data)

| . | Linear correlation coefficient . | P value . |

|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.01076 | .526 |

| Performance status (at admission) | 0.2380 | .6510 |

| No. of previous lines | −0.07808 | .7306 |

| Albumin level | 0.05704 | .252 |

| Prealbumin level | 4.4092 | .177 |

| Body mass index | −0.005473 | .917 |

| Body fat mass percentage | 0.01711 | .502 |

| Motivation | −0.06251 | .745 |

| Initial fatigue | 0.07648 | .146 |

| Initial pain level | −0.06133 | .563 |

| Fatigue Δ | −0.14815 | .0134∗ |

| Neutropenia duration | −0.02400 | .534 |

| Hospitalization duration | −0.006617 | .663 |

| . | Linear correlation coefficient . | P value . |

|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.01076 | .526 |

| Performance status (at admission) | 0.2380 | .6510 |

| No. of previous lines | −0.07808 | .7306 |

| Albumin level | 0.05704 | .252 |

| Prealbumin level | 4.4092 | .177 |

| Body mass index | −0.005473 | .917 |

| Body fat mass percentage | 0.01711 | .502 |

| Motivation | −0.06251 | .745 |

| Initial fatigue | 0.07648 | .146 |

| Initial pain level | −0.06133 | .563 |

| Fatigue Δ | −0.14815 | .0134∗ |

| Neutropenia duration | −0.02400 | .534 |

| Hospitalization duration | −0.006617 | .663 |

| . | Difference in relative gain (%) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|

| Age ≥ 65 years | 0.70 (n) vs 0.23 (y) | .4312 |

| Sex | 0.68 (f) vs 0.55 (m) | .8055 |

| AL | −0.06 (n) vs 1.25 (y) | .003261∗∗ |

| MDS and/or MPN | 1.03 (n) vs −0.17 (y) | .0296∗ |

| Lymphoma | 0.65 (n) vs 0.18 (y) | .1413 |

| Evolutive disease | 1.05 (n) vs −0.08 (y) | .02986∗ |

| Malnutrition | 1.00 (n) vs 0.36 (y) | .3011 |

| Use of artificial nutrition | NA (all but 1 observation) | NA |

| Obesity | 0.62 (n) vs 0.54 (y) | .8294 |

| Physical activity of >3 h/wk | 0.47 (n) vs 1.16 (y) | .2939 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction of <50% | 0.61 (n) vs 0.47 (y) | .6143 |

| Obstructive respiratory disorder | 0.67 (n) vs 0.36 (y) | .5492 |

| Diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide of <60% | 0.90 (n) vs −1.05 (y) | .07107 |

| Failure of treatment | NA (1 observation) | NA |

| Intensive care admission | 0.75 (n) vs −2.89 (y) | .3742 |

| Viral infection | 0.81 (n) vs 0.34 (y) | .3431 |

| Invasive fungal infection | 0.62 (n) vs 0.52 (y) | .7996 |

| Mucositis grade ≥3 | 0.65 (n) vs 0.20 (y) | .5942 |

| Acute digestive GVHD grade ≥3 | 0.78 (n) vs −0.21 (y) | .3742 |

| Acute cutaneous GVHD grade ≥3 | 0.40 (n) vs 1.38 (y) | .1071 |

| . | Difference in relative gain (%) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|

| Age ≥ 65 years | 0.70 (n) vs 0.23 (y) | .4312 |

| Sex | 0.68 (f) vs 0.55 (m) | .8055 |

| AL | −0.06 (n) vs 1.25 (y) | .003261∗∗ |

| MDS and/or MPN | 1.03 (n) vs −0.17 (y) | .0296∗ |

| Lymphoma | 0.65 (n) vs 0.18 (y) | .1413 |

| Evolutive disease | 1.05 (n) vs −0.08 (y) | .02986∗ |

| Malnutrition | 1.00 (n) vs 0.36 (y) | .3011 |

| Use of artificial nutrition | NA (all but 1 observation) | NA |

| Obesity | 0.62 (n) vs 0.54 (y) | .8294 |

| Physical activity of >3 h/wk | 0.47 (n) vs 1.16 (y) | .2939 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction of <50% | 0.61 (n) vs 0.47 (y) | .6143 |

| Obstructive respiratory disorder | 0.67 (n) vs 0.36 (y) | .5492 |

| Diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide of <60% | 0.90 (n) vs −1.05 (y) | .07107 |

| Failure of treatment | NA (1 observation) | NA |

| Intensive care admission | 0.75 (n) vs −2.89 (y) | .3742 |

| Viral infection | 0.81 (n) vs 0.34 (y) | .3431 |

| Invasive fungal infection | 0.62 (n) vs 0.52 (y) | .7996 |

| Mucositis grade ≥3 | 0.65 (n) vs 0.20 (y) | .5942 |

| Acute digestive GVHD grade ≥3 | 0.78 (n) vs −0.21 (y) | .3742 |

| Acute cutaneous GVHD grade ≥3 | 0.40 (n) vs 1.38 (y) | .1071 |

f, female; m, male; n, no; NA, not applicable; y, yes.

P ≤ .05; ∗∗P ≤ .01.

Univariate analysis for gain of LM among patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT (physical tests)

| Test . | Linear correlation coefficient . | P value . |

|---|---|---|

| HGT (dominant hand) | −0.01520 | .482 |

| HGT (nd hand) | −0.01366 | .528 |

| ΔHGT (dominant hand) | 0.3131 | .0129 |

| ΔHGT (nd hand) | 0.56002 | .00769 |

| ACT (dominant arm) | 0.02146 | .570 |

| ACT (nd arm) | 0.02148 | .564 |

| ΔACT (dominant arm) | 0.26561 | .00673 |

| ΔACT (nd arm) | 0.24913 | .0198 |

| OLST (dominant leg) | 0.009909 | .633 |

| OLST (nd leg) | −0.00453 | .823 |

| ΔOLST (dominant leg) | 0.12160 | .00123 |

| ΔOLST (nd leg) | 0.13512 | .000279 |

| 30SCT | 0.02938 | .501 |

| Δ30SCT | 0.45942 | .00123 |

| Test . | Linear correlation coefficient . | P value . |

|---|---|---|

| HGT (dominant hand) | −0.01520 | .482 |

| HGT (nd hand) | −0.01366 | .528 |

| ΔHGT (dominant hand) | 0.3131 | .0129 |

| ΔHGT (nd hand) | 0.56002 | .00769 |

| ACT (dominant arm) | 0.02146 | .570 |

| ACT (nd arm) | 0.02148 | .564 |

| ΔACT (dominant arm) | 0.26561 | .00673 |

| ΔACT (nd arm) | 0.24913 | .0198 |

| OLST (dominant leg) | 0.009909 | .633 |

| OLST (nd leg) | −0.00453 | .823 |

| ΔOLST (dominant leg) | 0.12160 | .00123 |

| ΔOLST (nd leg) | 0.13512 | .000279 |

| 30SCT | 0.02938 | .501 |

| Δ30SCT | 0.45942 | .00123 |

ACT, arm curl test; nd, nondominant.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the only study specifically addressing APA in a population of hospitalized adult patients with hematological malignancies and receiving chemotherapy and/or allogeneic HSCT.

Firstly, this study showed that it is possible to obtain LM preservation for patients benefiting from APA associated with other supportive cares (mean absolute gain of 0.33 kg [95% CI, 0.15-0.50]); mean relative gain of 0.64% (95% CI, 0.28-1.01; P = .00068). Such a finding is supported by previously reported results regarding the impact of physical activity on body composition among patients with cancer. In a recent meta-analysis including 34 studies involving patients with various malignancies (some of them undergoing chemotherapy), it was found that physical exercise resulted in an absolute LM gain of 0.51 kg (95 % CI, −0.05 to 1.06; P = .072) in the intervention arms and an absolute LM gain difference of 0.85 kg compared with control arms (95% CI, 0.26-1.43; P = .004).27 Still, the benefits of physical exercise on LM are inconstantly found in the literature, especially in oncology and hematology studies involving smaller numbers of patients.15,28 And therefore, to date, we lack specific recommendations for physical exercise in the management of cancer-related sarcopenia.29

Secondly, this study identified risk factors for LM loss for hematology patients during hospitalization. Among factors commonly known for influencing LM gain in the physiological or pathological setup are protein supplementation (positively), resistance training (positively), and age (negatively).29-32 There is also evidence that face-to-face interventions have a positive impact compared with unsupervised sessions.27,33 In our study, age was found to be a key determinant for LM gain during hospitalization, along with the duration of severe neutropenia, which also had a negative impact on LM gain. This latter result could be related to interindividual sensitivity to chemotherapy (because chemotherapy inhibits the muscle metabolism),34 or with the cumulative impact of other variables associated with prolonged neutropenia (such as infections or treatment failure). Another explanation could be that neutropenia remains a source of apprehension for patients and caregivers, limiting the participation in physical activity, although it has been proven safe among patients with neutropenia with hematological malignancies.35 There is also some evidence that physical exercise might help stimulate neutrophil function and recovery, which may explain why patients with worst LM gain have longer neutropenia.36

In this study, an increase in fatigue during hospitalization had a negative impact on LM gain in univariate analysis, supporting the idea that regular management of fatigue might be a relevant strategy to prevent LM loss. One potential strategy to combat fatigue could involve increasing session intensity for selected patients. Several studies have reported greater reductions in fatigue with higher exercise intensity among patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy.37 However, it remains uncertain whether this approach is suitable for all hematology patients, especially considering their unique vulnerabilities,4 and some individuals may benefit more from increased session frequency rather than intensity to manage fatigue without causing exhaustion.

Additionally, physical tests could serve as useful monitoring tools in daily practice to screen patients losing or at risk of losing LM, while being easily performable inside patient rooms. In our study, an improvement of HGT on the dominant limb and of the 30SCT were the physical parameters most strongly correlated with LM gain over hospitalization in univariate analysis. Of note, the use of these 2 tests is recommended to identify patients with low muscle strength and screening for sarcopenia by the EWGSOP, the Foundation for National Institute of Health Sarcopenia Project, and the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia.19-21 In our study, the dominant limb best accounted for the variation in LM. In the literature however, the importance of the limb chosen for physical tests (dominant vs nondominant) is debated.38,39

Our study has some limitations. We chose LM gain as the main criterion because it is objectively quantifiable and recognized as a determinant of favorable outcome for patients. In the case of LM measurement, BIA presents limitations. Notably, it does not directly measure LM but rather derives an estimation based on body electrical conductivity through equations as previously mentioned. Age, ethnicity, and especially fluid balance can influence results.18,19,40 Nevertheless, BIA is the only precision method directly performable inside a hospital room, which is essential for hematology patients who need to stay isolated during sever neutropenia induced by chemotherapy.

This study was monocentric with heterogeneous population related to a heterogeneous population with a variety of treatments and hematological malignancies, thus reflecting a real-life hospitalization setting. To address a potential selection bias, we compared the main characteristics between the study population and excluded patients and did not find any significant difference between groups (supplemental Table 1). Median age in our study was 57 years (range, 18-87), whereas the median age at diagnosis for most hematological malignancies is closer to 65 to 70 years,41,42 and a substantial proportion of patients in our study underwent allogeneic HSCT, further selecting for fitter patients.

Conclusions

This study illustrates the feasibility of LM preservation during hospitalization of patients with hematological malignancies and benefiting from APA. It highlights a younger age and a short neutropenia as determinants of LM gain. Among physical tests, the HGT performed repeatedly on the dominant limb, and the 30SCT were good tools for identifying patients at risk of losing LM. We believe that patients would benefit from APA interventions being integrated into routine practice in oncohematology and hypothesize that patients with identified specific features may benefit from closer monitoring and adapted interventions aimed at tailoring physical activity programs to their needs. Our conclusions need to be confirmed in a larger sample size study.

Authorship

Contribution: A.S. and A.P. collected data; A.S. and N.M. performed the statistical analysis; N.M. and T.C. designed the study; A.S., N.M., and T.C. wrote the manuscript; and all authors edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Thomas Cluzeau, Hematology Department, Nice University Hospital, 151 route Saint Antoine de Ginestière, 06200 Nice, France; email: cluzeau.t@chu-nice.fr.

References

Author notes

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author, Thomas Cluzeau (cluzeau.t@chu-nice.fr).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.