Key Points

SKIDA1 is a fetal/neonatal-biased MLL::ENL target that binds polycomb repressive complex 2.

SKIDA1 sustains MLL::ENL-expressing neonatal HSCs and multipotent progenitor cells and promotes B-cell lineage priming.

Visual Abstract

Infant leukemias arise as B-cell acute lymphoblastic or acute myeloid leukemia. Most are driven by chromosomal rearrangements of the MLL/KMT2A gene (MLLr) and arise in utero, implying a fetal cell of origin. Fetal and neonatal hematopoietic progenitors have unique transcriptomes and epigenomes, raising the question of whether MLL fusion proteins activate distinct target genes during these early stages of life. In this study, we used a transgenic mouse model of MLL::ENL-driven leukemia to identify Skida1 as a target gene that is more highly induced in fetal and neonatal progenitors than in adult progenitors. SKIDA1 is highly expressed in human MLLr leukemias, and the encoded protein associates with the polycomb repressive complex 2. We show that Skida1 is dispensable for normal hematopoiesis, but it promotes B-cell priming and maintains MLL::ENL-expressing hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and multipotent progenitor cells during neonatal development. Conditional deletion of Skida1 has no effect on normal HSC function, yet it impairs B-cell production from neonatal MLL::ENL-expressing HSCs while leaving myeloid leukemogenesis unaffected. Temporally restricted targets of MLL fusion proteins, such as SKIDA1, can therefore tune cell fates at different ages, potentially influencing the types MLLr leukemias that arise at different ages.

Introduction

Infant leukemias can present as either acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL).1 Most infant leukemias are driven by chromosomal rearrangements that involve the MLL (KMT2A) gene. The rearranged loci express MLL fusion proteins (eg, MLL::ENL, MLL::AF9, and MLL::AF4) that ectopically activate HOX genes and MEIS1 to drive leukemic transformation.2-5MLL rearrangements (MLLr) have been shown to arise before birth in patients who ultimately developed infant leukemias, indicating a fetal/neonatal cell of origin.6-9 This raises the question of whether MLLr activate distinct leukemogenic programs when they arise in fetal/neonatal progenitors as compared with adult progenitors. Fetal- or neonatal-specific effectors of transformation might explain why infant leukemias are often less responsive to chemotherapy than noninfant childhood or adult leukemias.

Previous studies have shown that fetal and neonatal progenitors do have distinct transcriptional and functional responses to MLL fusion proteins. For example, we previously used a transgenic mouse model to test whether MLL::ENL induces AML with varying degrees of efficiency across fetal, neonatal, and adult stages of development.10 Neonatal MLL::ENL induction initiated AML with greater efficiency than fetal or adult MLL::ENL induction, suggesting that transformation efficiency peaks shortly after birth. Likewise, MLL::AF9 and MLL::AF4 have been shown to transform human fetal and umbilical cord progenitors more efficiently than adult bone marrow progenitors.11-13 These data suggest that MLL fusion proteins activate subsets of target genes more effectively in fetal and neonatal progenitors than in adult progenitors. Such targets might potentiate transformation, or they might alter lineage biases within preleukemic cells of origin.

To understand how age alters transcriptional responses to MLL fusion proteins, we used a previously described, inducible model of MLL::ENL-driven AML to identify target genes that distinguish fetal, neonatal, and adult progenitors.10,14 We identified Skida1 as a gene that is more highly induced in fetal and neonatal progenitors than in adult progenitors. SKIDA1 is highly expressed in human MLLr leukemias, and the encoded protein associates with several components of the polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2). Using conditional loss-of-function mice, we found that Skida1 is dispensable for normal hematopoiesis and myeloid leukemogenesis. Furthermore, Skida1 selectively maintains B-cell potential in MLL::ENL-expressing neonatal hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). Altogether, these data show that Skida1 is an effector of MLL::ENL-driven B-lineage priming and HSC/ multipotent progenitor cell (MPP) maintenance during neonatal stages of life.

Methods

Mouse lines

Details on construction of Skida1 loss-of-function alleles are provided in the supplemental Methods. Vav1-Cre, Rosa26LSL-rtTA-IRES-mKate2, and Rosa26LSL-tTA were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory.15-17Col1a1TetO-MLL::ENL mice (from David Bryder, Lund University, Lund, Sweden) have been described previously.14 All procedures were performed according to institutional animal care and use committee–approved protocols.

Flow cytometry, library construction, cell culture, and analyses

Bone marrow or liver cells were isolated and analyzed as described previously18 and in the supplemental Methods. Myeloid and B-cell colony formation assays were performed as previously described.19 RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) libraries were generated as described in the supplemental Methods. Cellular indexing of transcriptomes and epitopes sequencing libraries were generated as previously described using 10x Genomics 3′ kits per manufacturer instructions. For cell line studies, THP-1 and KOPN-8 cells were edited with AAVS- or SKIDA1-specific guide RNA. Cell counts were made on hemocytometer or MTS (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-5-[3-carboxymethoxyphenyl]-2-[4-sulfophenyl]-2H-tetrazolium) assay (Promega). Complete details, including culture media and drug treatment conditions, are in the supplemental Methods.

Immunoprecipitation, mass spectrometry, and western blots

Indicated cell lines were transduced with control or SKIDA1-FLAG lentivirus produced from a pInducer20 plasmid. SKIDA1-FLAG expression was induced by treating cells with doxycycline for 72 hours. Immunoprecipitation was performed using anti-FLAG beads or indicated antibodies. Immunoprecipitates were evaluated by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry or western blotting. Complete details are available in the supplemental Methods.

PDX editing

Infant B-ALL patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) were generated from clinically annotated primary specimens, without protected health information, collected under the auspices of institutional review board–approved research protocols at Washington University or Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, as previously described.20,21 Details on CRISPR/CRISPR–associated protein 9 (Cas9) editing and variant allele assessments are provided in the supplemental Methods.

Results

Skida1 is an MLL::ENL target gene that is more highly induced in fetal and neonatal progenitors than in adult progenitors

To identify genes that are more strongly induced by MLL::ENL in fetal and neonatal progenitors than in adult progenitors, we analyzed MLL::ENL-driven changes in gene expression in HSC/MPPs (lineage−Sca1+Kit+ [LSK]) at embryonic day 16 (E16), postnatal day 14 (P14), and 8 weeks after birth. For these experiments, we used mice with Vav1-Cre, Rosa26LoxP-STOP-LoxP-reverse-tet-transactivator (Rosa26LSL-rtTA) and Col1a1TetO-MLL::ENL alleles (hereafter referred to as Tet-On-ME). These mice express MLL::ENL specifically in hematopoietic cells upon exposure to doxycycline. We cultured LSK cells for 48 hours, with or without doxycycline, and then performed RNA-seq to identify changes in gene expression that occurred shortly after MLL::ENL induction, independently of microenvironmental differences that might distinguish fetal, neonatal, and adult progenitors (supplemental Figure 1A).

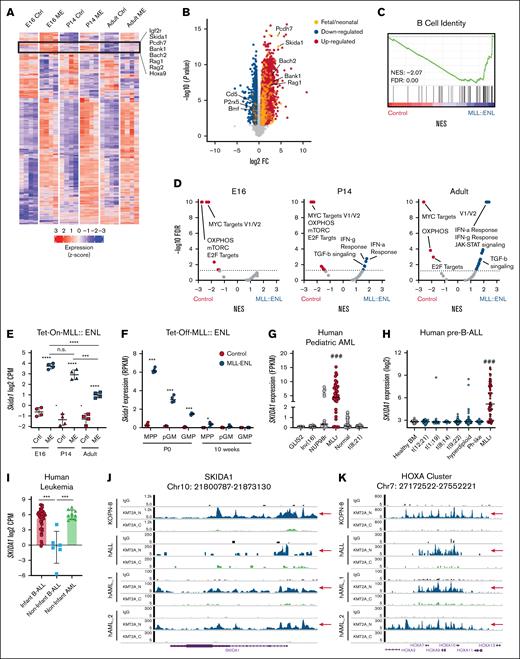

MLL::ENL induced extensive changes in gene expression for each age studied (Figure 1A; supplemental Table 1). Most differentially expressed genes were induced or repressed to similar levels in fetal, neonatal, and adult progenitors (Figure 1A; supplemental Table 1). However, several genes were more highly induced by MLL::ENL in fetal and neonatal HSC/MPPs as compared with adult HSC/MPPs (Figure 1A, highlighted cluster), including the known MLL::ENL target gene Hoxa9 (Figure 1A). In addition, B-cell identity genes, including Rag1, Rag2, Bach2, and Bank1, were more highly expressed in E16 and P14 progenitors (Figure 1A-C), indicating that MLL::ENL enhances B-lymphoid priming in fetal/neonatal progenitors. Several Hallmark gene signatures, including MYC target genes, oxidative phosphorylation genes, and E2F target genes, were downregulated in MLL::ENL-expressing progenitors at all ages based on gene set enrichment analysis (Figure 1D). Interferon and transforming growth factor β signatures were activated by MLL::ENL, specifically in P14 and adult progenitors (Figure 1D). These observations reinforce the premise that MLL::ENL induces distinct transcriptional programs in fetal, neonatal, and adult progenitors, independently of any microenvironmental differences.

MLL::ENL induces Skida1 expression in fetal and neonatal HSC/MPPs.(A) Heat map showing genes that are significantly differentially expressed (FDR < 0.05, log2FC > 0.6) upon MLL::ENL induction in E16 and P14 and 8-week-old adult Tet-On-ME LSK cells. A cluster of genes that are more highly induced in fetal and neonatal LSK cells, relative to adult LSK cells, is outlined with representative genes indicated. (B) Volcano plot indicating genes that are significantly differentially expressed in fetal LSK upon MLL::ENL induction, with color coding to indicate genes that are selectively induced in fetal and neonatal progenitors. (C) Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) plot showing B-cell signature enrichment in E16 MLL::ENL-expressing progenitors. (D) Volcano plots indicating changes in expression in Hallmark gene signatures upon MLL::ENL expression, based on GSEA. (E) Skida1 expression in LSK cells from the indicated ages, based on RNA-seq; n = 4 biological replicates per genotype and age. ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001 by 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Tukey post hoc test. (F) Skida1 expression in wild-type and Tet-Off-ME progenitors at P0 and age 10 weeks; n = 4 biological replicates per progenitor population and age. ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗P < .001 by Student t test. (G-H) SKIDA1 expression in MLLr pediatric AML and B-ALL. ###P < .001 relative to all other subtypes by 1-way ANOVA with the Tukey post hoc test. (I) SKIDA1 expression in infant B-ALL, noninfant B-ALL, and noninfant AML. ∗∗∗P < .001 by 2-way ANOVA with the Tukey post hoc test. (J-K) MLL fusion protein binding to the SKIDA1 and HOXA loci in KOPN-8 cells or primary MLLr leukemias. CPM, counts per million; Ctrl, control; FC, fold change; FDR, false discovery rate; IFN-a/g, interferon alpha/gamma; IgG, immunoglobulin G; ME, MLL::ENL; mTORC, mammalian Target of Rapamyxin; NES, normalized enrichment scores; n.s., not significant; OXPHOS, oxidative phosphorylation; TGF-b, transforming growth factor β.

MLL::ENL induces Skida1 expression in fetal and neonatal HSC/MPPs.(A) Heat map showing genes that are significantly differentially expressed (FDR < 0.05, log2FC > 0.6) upon MLL::ENL induction in E16 and P14 and 8-week-old adult Tet-On-ME LSK cells. A cluster of genes that are more highly induced in fetal and neonatal LSK cells, relative to adult LSK cells, is outlined with representative genes indicated. (B) Volcano plot indicating genes that are significantly differentially expressed in fetal LSK upon MLL::ENL induction, with color coding to indicate genes that are selectively induced in fetal and neonatal progenitors. (C) Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) plot showing B-cell signature enrichment in E16 MLL::ENL-expressing progenitors. (D) Volcano plots indicating changes in expression in Hallmark gene signatures upon MLL::ENL expression, based on GSEA. (E) Skida1 expression in LSK cells from the indicated ages, based on RNA-seq; n = 4 biological replicates per genotype and age. ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001 by 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Tukey post hoc test. (F) Skida1 expression in wild-type and Tet-Off-ME progenitors at P0 and age 10 weeks; n = 4 biological replicates per progenitor population and age. ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗P < .001 by Student t test. (G-H) SKIDA1 expression in MLLr pediatric AML and B-ALL. ###P < .001 relative to all other subtypes by 1-way ANOVA with the Tukey post hoc test. (I) SKIDA1 expression in infant B-ALL, noninfant B-ALL, and noninfant AML. ∗∗∗P < .001 by 2-way ANOVA with the Tukey post hoc test. (J-K) MLL fusion protein binding to the SKIDA1 and HOXA loci in KOPN-8 cells or primary MLLr leukemias. CPM, counts per million; Ctrl, control; FC, fold change; FDR, false discovery rate; IFN-a/g, interferon alpha/gamma; IgG, immunoglobulin G; ME, MLL::ENL; mTORC, mammalian Target of Rapamyxin; NES, normalized enrichment scores; n.s., not significant; OXPHOS, oxidative phosphorylation; TGF-b, transforming growth factor β.

The list of genes that were more highly induced by MLL::ENL in fetal/neonatal HSC/MPPs, as compared with adult HSC/MPPs, included Skida1, a gene that lacks a previously described function in infant or MLLr leukemogenesis (Figure 1E) but may serve as a biomarker.22 Analysis of previously collected in vivo RNA-seq data10 showed that Skida1 is more highly expressed in P0 MLL::ENL-expressing HSC/MPPs, relative to P14 and 8-week-old HSC/MPPs (Figure 1F). Fetal pre–granulocyte-monocyte progenitors (pGM) and granulocyte-monocyte progenitors (GMPs) showed somewhat lower levels of Skida1 induction at P0 (Figure 1F). Skida1 expression was very low in all normal cell populations at all ages. Thus, Skida1 is a fetal/neonatal MLL::ENL target gene both in ex vivo culture experiments and in vivo.

Next, we assessed SKIDA1 expression and MLL fusion protein binding at the SKIDA1 locus in human leukemias by analyzing previously collected RNA-seq and cleavage under targets and tagmentation data.23-26 In both AML and B-ALL, SKIDA1 expression was much higher in MLLr leukemias than in non-MLLr leukemias (Figure 1G-H). MLLr AML expressed SKIDA1 in both infant and noninfant cases (supplemental Figure 1B). In contrast, MLLr B-ALL expressed SKIDA1 only in infant cases, illustrating a unique fetal-/neonatal-specific mode of regulation in B-lineage leukemias (Figure 1I). As in mice, normal human progenitors did not express SKIDA1 at high levels at any age (supplemental Figure 1C). MLL fusion proteins bound directly to the SKIDA1 locus in both B-ALL and AML, similar to canonical target genes such as the HOXA cluster (Figure 1J-K). Thus, SKIDA1 is selectively expressed in MLLr leukemias, including age-restricted expression in infant B-ALL, and it is a direct target of MLL fusion oncoproteins based on the localization of fusion proteins to the SKIDA1 promoter. These observations raise questions as to how SKIDA1 functions at a molecular level and whether it promotes MLLr leukemogenesis.

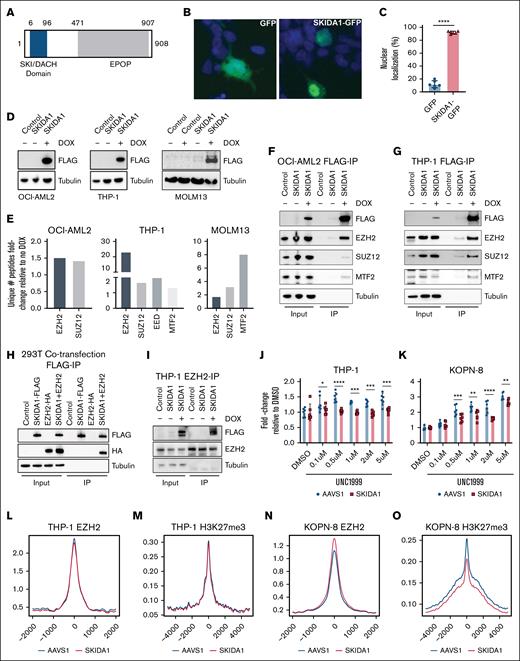

SKIDA1 is a nuclear protein that interacts with the PRC2

Skida1 encodes a 98 kDa protein with an N-terminal SKI/DACH domain and a C-terminal EPOP (elongin BC and PRC2-associated protein) homology region (Figure 2A). A SKIDA1–green fluorescent protein fusion localized primarily to the nucleus (Figure 2B-C), suggesting potential interactions with other nuclear proteins and transcriptional regulators. Indeed, SKI/DACH domains have been shown to bind SMAD family transcription factors, and EPOP has been shown to interact with PRC2 to restrict chromatin interactions.27-34 These features suggest that SKIDA1 may interact with either SMAD family proteins or PRC2.

SKIDA1 is a nuclear protein that interacts with PRC2 proteins. (A) Schematic of the SKIDA1 protein highlighting the SKI/DACH (blue) and EPOP homology (gray) domains with corresponding human amino acid numbers. (B) Representative pictures of green fluorescent protein (GFP) (left) and SKIDA1-GFP (right) subcellular localization in transfected 293T cells. The localization pattern of SKIDA1-GFP was considered “nuclear” for the purpose of quantification in panel C, based on overlap with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; blue). (C) Quantification of cells with nuclear SKIDA1-GFP localization. ∗∗∗∗P < .0001 by Student t test. (D) Western blot showing SKIDA1-FLAG expression in in human OCI-AML2, THP-1, and MOLM13 cell lines after 3 days of doxycycline (DOX) exposure. (E) Fold increase in unique peptides identified in SKIDA1-FLAG pulldown assays by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry in OCI-AML2, THP-1, and MOLM13 cell lines, based on no DOX vs DOX comparison. (F-G) Coimmunoprecipitation of PRC2 proteins with SKIDA1-FLAG in OCI-AML2 and THP-1 cells. (H) Coimmunoprecipitation of HA-tagged EZH2 with SKIDA1-FLAG in cotransfected 293T cells. (I) Coimmunoprecipitation of SKIDA1-FLAG with EZH2 in THP-1 cells. (J-K) MTS assays showing modestly increased numbers of THP-1 and KOPN-8 cells after 8 days of incubation with UNC1999. SKIDA1 deletion mitigated this growth increase; n = 6 replicated per dose and genotype. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001 by 2-way ANOVA with the Tukey post hoc test. (L-O) Aggregate histogram traces for EZH2 and H3K27me3 peaks in THP-1 or KOPN-8 cells, based on cleavage under targets and release using nuclease assay. IP, immunoprecipitation.

SKIDA1 is a nuclear protein that interacts with PRC2 proteins. (A) Schematic of the SKIDA1 protein highlighting the SKI/DACH (blue) and EPOP homology (gray) domains with corresponding human amino acid numbers. (B) Representative pictures of green fluorescent protein (GFP) (left) and SKIDA1-GFP (right) subcellular localization in transfected 293T cells. The localization pattern of SKIDA1-GFP was considered “nuclear” for the purpose of quantification in panel C, based on overlap with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; blue). (C) Quantification of cells with nuclear SKIDA1-GFP localization. ∗∗∗∗P < .0001 by Student t test. (D) Western blot showing SKIDA1-FLAG expression in in human OCI-AML2, THP-1, and MOLM13 cell lines after 3 days of doxycycline (DOX) exposure. (E) Fold increase in unique peptides identified in SKIDA1-FLAG pulldown assays by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry in OCI-AML2, THP-1, and MOLM13 cell lines, based on no DOX vs DOX comparison. (F-G) Coimmunoprecipitation of PRC2 proteins with SKIDA1-FLAG in OCI-AML2 and THP-1 cells. (H) Coimmunoprecipitation of HA-tagged EZH2 with SKIDA1-FLAG in cotransfected 293T cells. (I) Coimmunoprecipitation of SKIDA1-FLAG with EZH2 in THP-1 cells. (J-K) MTS assays showing modestly increased numbers of THP-1 and KOPN-8 cells after 8 days of incubation with UNC1999. SKIDA1 deletion mitigated this growth increase; n = 6 replicated per dose and genotype. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001 by 2-way ANOVA with the Tukey post hoc test. (L-O) Aggregate histogram traces for EZH2 and H3K27me3 peaks in THP-1 or KOPN-8 cells, based on cleavage under targets and release using nuclease assay. IP, immunoprecipitation.

To test whether SKIDA1 interacts with PRC2 or other nuclear proteins, we performed coimmunoprecipitation assays followed by mass spectrometry. We generated a doxycycline-inducible SKIDA1-3×FLAG lentiviral construct (SKIDA1-FLAG) and transduced THP-1, OCI-AML2, and MOLM13 AML cells to generate stable, inducible MLLr cell lines (Figure 2D). We immunoprecipitated SKIDA1-FLAG from doxycycline-treated and untreated cells and performed liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. We identified 2 PRC2 proteins, EZH2 and SUZ12, as having greater than twofold higher peptide counts in doxycycline-treated cells relative to untreated cells across the 3 cell lines and in a murine cell line, 32D (Figure 2E; supplemental Tables 2 and 3). Additional PRC2 proteins, EED and MTF2, were also immunoprecipitated in THP-1 and MOLM13 cells (Figure 2E). Coimmunoprecipitation assays validated the interaction between SKIDA1 and EZH2 (Figure 2F-I; supplemental Figure 2A), as well as weaker interactions with SUZ12 and MTF2. Other nuclear transcription factors, such PU.1 and RUNX1, did not coimmunoprecipitate (data not shown). Thus, SKIDA1 interacts with PRC2.

PRC2 places inhibitory histone H3, lysine 27 trimethyl marks (H3K27me3) on chromatin, and we therefore tested whether SKIDA1 inactivation alters PRC2 function. We induced frameshift mutations near the 5′ end of the single SKIDA1 coding exon in THP-1 and KOPN-8 (infant B-ALL) cell lines by CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis. An AAVS1-directed guide RNA served as a control. SKIDA1 mutations did not alter baseline proliferation of either cell line (supplemental Figure 2B-C). The EZH2 inhibitor UNC1999 modestly enhanced proliferation of both THP-1 and KOPN-8 cells, suggesting that PRC2 exerts a modest negative effect on MLLr leukemia growth (Figure 2J-K). SKIDA1 inactivation mitigated the growth advantage in both cell lines. Cleavage under targets and tagmentation assays showed that SKIDA1 inactivation modestly enhanced EZH2 binding but reduced H3K27me3 placement in KOPN-8 but not THP-1 cells (Figure 2L-O). Taken together, these data show that SKIDA1 binds PRC2 and modulates its activity. Any effects of SKIDA1 on PRC2 function appear to be small and context-specific. Nevertheless, these observations raise the question of whether Skida1 regulates hematopoiesis and leukemogenesis in vivo.

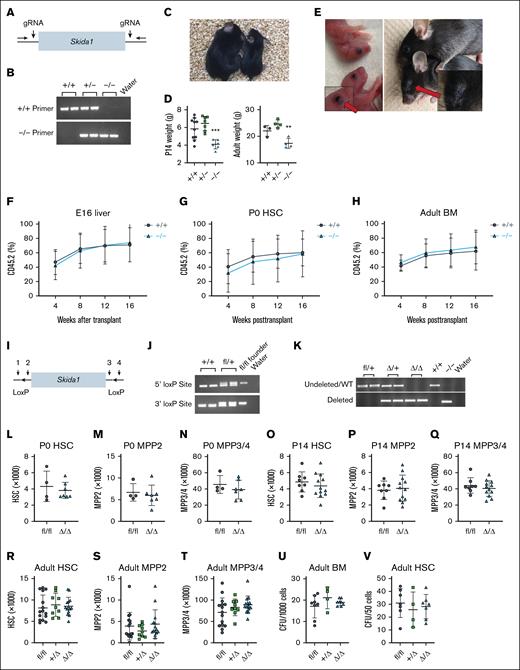

Skida1 is dispensable for normal murine hematopoiesis and HSC function

To test whether Skida1 regulates normal development, we generated mice with a germ line Skida1 loss-of-function allele. We used CRISPR/Cas9 to delete the single Skida1 coding exon to generate a null allele (Figure 3A-B). Skida1−/− mice were born at normal Mendelian ratios but grew less than wild-type or Skida1+/− littermates over the first 21 days of life (Figure 3C-D). Many Skida1-deficient mice did not survive past weaning (supplemental Figure 3A), and those that did survive remained small into adulthood (Figure 3D). The most obvious gross morphological defect in Skida1−/− mice was failure to develop normal eyes. At birth, Skida1−/− mice had partially opened eyelids (Figure 3E, left panel), and by adulthood, the orbits were scarred shut and the eyes decayed (Figure 3E, right panel). Thus, in addition to being an MLL::ENL target gene, Skida1 regulates eye development.

Skida1 is not required for normal hematopoiesis or HSC function during fetal, neonatal, or adult stages. (A) Diagram of Skida1 germ line loss-of-function allele with vertical arrows indicating cut sites around the single coding exon to generate Skida1 null mice. (B) Representative genotyping polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of the deleted Skida1 allele. (C) Representative pictures of P21 Skida1−/− (right) and Skida1+/+ littermates (left). (D) Body weights for Skida1+/+, Skida1+/−, and Skida1−/− mice at P14 and age 8 weeks. P14 n = 10 (+/+), n = 7 (+/−), n = 6 (−/−); age 8 weeks, n = 3 (+/+), n = 4 (+/−), n = 4 (−/−). ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001 by 1-way ANOVA with the Tukey post hoc test. (E) Representative pictures of eye defects in Skida1−/− mice at P0 and age 8 weeks. (F-H) CD45.2+ peripheral blood chimerism levels in recipients of E16 fetal liver cells, P0 HSCs or age 8 weeks BM cells from donors with the indicated genotypes. E16 recipients: n = 17 (+/+), n = 18 (−/−); P0 recipients: n = 17 (+/+), n = 19 (−/−); and aged 8 weeks recipients: n = 9 (+/+), n = 8 (−/−). (I) Diagram of Skida1 conditional loss-of-function allele. LoxP sites were inserted around the single coding exon by Cas9 editing and homologous recombination. Genotyping primer sites (1-4) are indicated. (J) Representative genotyping PCR for the Skida1fl allele. (K) Representative PCR indicating complete deletion of the floxed allele in CD45.2+ peripheral blood cells from Skida1fl/fl;Vav-Cre mice. (L-T) Total cell numbers of indicated populations and genotypes in P0 whole liver, or P14 or adult BM from 2 hind limbs (tibia and femur). P0: n = 4 (fl/fl), n = 7 (Δ/Δ); P14: n = 8 (fl/fl), n = 12 (Δ/Δ); adult: n = 15 (fl/fl), n = 9 (+/Δ), n = 14 (Δ/Δ). (U-V) CFU frequencies generated from 1000 whole BM cells or sorted HSCs from adult mice with the indicated genotypes. Whole BM: n = 8 (fl/fl), n = 4 (+/Δ), n = 8 (Δ/Δ); HSCs: n = 7 (fl/fl), n = 4 (+/Δ), n = 7 (Δ/Δ). None of the comparisons in panels L through V indicated significant differences among the genotypes, as calculated by Student t test or 1-way ANOVA with the Tukey post hoc test. BM, bone marrow; gRNA, guide RNA; WT, wild type.

Skida1 is not required for normal hematopoiesis or HSC function during fetal, neonatal, or adult stages. (A) Diagram of Skida1 germ line loss-of-function allele with vertical arrows indicating cut sites around the single coding exon to generate Skida1 null mice. (B) Representative genotyping polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of the deleted Skida1 allele. (C) Representative pictures of P21 Skida1−/− (right) and Skida1+/+ littermates (left). (D) Body weights for Skida1+/+, Skida1+/−, and Skida1−/− mice at P14 and age 8 weeks. P14 n = 10 (+/+), n = 7 (+/−), n = 6 (−/−); age 8 weeks, n = 3 (+/+), n = 4 (+/−), n = 4 (−/−). ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001 by 1-way ANOVA with the Tukey post hoc test. (E) Representative pictures of eye defects in Skida1−/− mice at P0 and age 8 weeks. (F-H) CD45.2+ peripheral blood chimerism levels in recipients of E16 fetal liver cells, P0 HSCs or age 8 weeks BM cells from donors with the indicated genotypes. E16 recipients: n = 17 (+/+), n = 18 (−/−); P0 recipients: n = 17 (+/+), n = 19 (−/−); and aged 8 weeks recipients: n = 9 (+/+), n = 8 (−/−). (I) Diagram of Skida1 conditional loss-of-function allele. LoxP sites were inserted around the single coding exon by Cas9 editing and homologous recombination. Genotyping primer sites (1-4) are indicated. (J) Representative genotyping PCR for the Skida1fl allele. (K) Representative PCR indicating complete deletion of the floxed allele in CD45.2+ peripheral blood cells from Skida1fl/fl;Vav-Cre mice. (L-T) Total cell numbers of indicated populations and genotypes in P0 whole liver, or P14 or adult BM from 2 hind limbs (tibia and femur). P0: n = 4 (fl/fl), n = 7 (Δ/Δ); P14: n = 8 (fl/fl), n = 12 (Δ/Δ); adult: n = 15 (fl/fl), n = 9 (+/Δ), n = 14 (Δ/Δ). (U-V) CFU frequencies generated from 1000 whole BM cells or sorted HSCs from adult mice with the indicated genotypes. Whole BM: n = 8 (fl/fl), n = 4 (+/Δ), n = 8 (Δ/Δ); HSCs: n = 7 (fl/fl), n = 4 (+/Δ), n = 7 (Δ/Δ). None of the comparisons in panels L through V indicated significant differences among the genotypes, as calculated by Student t test or 1-way ANOVA with the Tukey post hoc test. BM, bone marrow; gRNA, guide RNA; WT, wild type.

We analyzed hematopoiesis in E16, P0, and adult wild-type Skida1+/− and Skida1−/− mice. HSC (CD150+CD48−LSK) and MPP (CD48+LSK) numbers were similar across all 3 genotypes at E16 (supplemental Figure 3B-C). At P0, we observed a small increase in total HSC numbers in Skida1−/− pups but no differences in MPP numbers (supplemental Figure 3D-E). Surviving adult Skida1−/− mice had similar numbers of HSCs and MPPs (supplemental Figure 3F-G). To assess HSC function, we competitively transplanted 300 000 fetal liver cells from E16 wild-type or Skida1−/− mice (CD45.2+) along with 300 000 wild-type competitor bone marrow cells (CD45.1+) into lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipient mice. We did not observe differences in donor peripheral blood chimerism over 16 weeks of posttransplant evaluation (Figure 3F; supplemental Figure 3H). We also transplanted 20 purified HSCs per recipient from P0 wild-type or Skida1−/− mice, along with 300 000 wild-type competitor cells, followed by secondary transplants of 3 million unfractionated primary recipient bone marrow cells. We did not see differences in repopulation in either primary or secondary recipients (Figure 3G; supplemental Figure 3I,K,L). Finally, we competitively transplanted 300 000 bone marrow cells from adult wild-type and Skida1−/− mice and again saw no difference in repopulating activity (Figure 3H; supplemental Figure 3J). Together, these data show that Skida1 does not regulate normal fetal, neonatal, or adult hematopoietic progenitor frequencies or HSC function, consistent with its low level of expression in the absence of MLL::ENL (Figure 1F).

The growth and survival defects of Skida1−/− mice confounded plans to evaluate preleukemic progenitors and leukemogenesis in the context of MLL::ENL expression so we generated a conditional loss-of-function Skida1flox allele (Figure 3I-J). We used Vav1-Cre to delete Skida1 in hematopoietic progenitors beginning at E10.5 (Figure 3K). Adult Skida1fl/fl;Vav1-Cre (Skida1Δ/Δ) mice had normal weights, bone marrow cellularity, spleen weights, and peripheral blood cell counts (supplemental Figure 3M-P). Skida1 deletion did not alter HSC, MPP2 (CD150+CD48+LSK), MPP3/4 (CD150−CD48+LSK), or GMP (lineage−Sca1−Kit+CD105−CD16/32+) numbers in P0 or P14 mice, or 8-week-old adult mice (Figure 3L-T; supplemental Figures 3Q-R and 4).35,36 Control and Skida1Δ/Δ progenitors had similar colony forming unit (CFU) frequencies in methylcellulose media supplemented with myeloid and erythroid cytokines (Figure 3U-V). Altogether, these data show that Skida1 has little to no role in normal fetal, neonatal, or adult hematopoiesis.

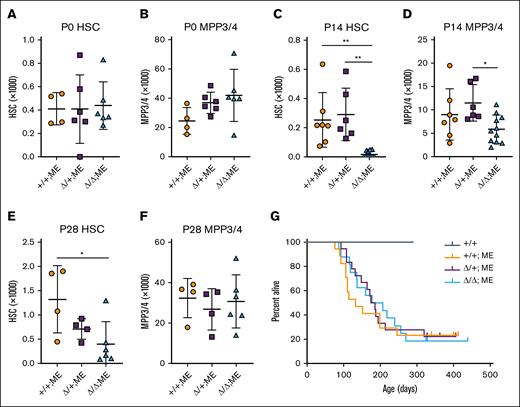

Skida1 selectively sustains neonatal MLL::ENL-expressing HSCs and MPPs

Next, we tested whether Skida1 regulates hematopoiesis and leukemogenesis in the context of MLL::ENL expression. We generated mice with Skida1flox and previously described Tet-Off-ME (Vav1-Cre;Rosa26LoxP-STOP-LoxP-tet-transactivator;Col1a1TetO-MLL::ENL) alleles and evaluated HSC and MPP3/4 numbers at P0, P14, and P28. Tet-Off-ME mice expressed MLL::ENL in developing blood progenitors in the absence of doxycycline, beginning at E10.5.10Skida1 deletion caused no significant changes in MLL::ENL-expressing HSC or MPP3/4 numbers at P0 (Figure 4A-B). However, by P14, we observed severe depletion of HSCs, and to a lesser extent MPP3/4s, in Skida1Δ/Δ;Tet-Off-ME mice (Figure 4C-D). P28 Skida1Δ/Δ;Tet-Off-ME mice showed sustained HSC depletion, but MPP3/4 numbers recovered and were similar to those of Skida1+/+;Tet-Off-ME controls (Figure 4E-F). We did not observe reductions in pGM or GMP numbers in P14 or P28 Skida1Δ/Δ;Tet-Off-ME mice (supplemental Figure 5A-D), suggesting that the ectopic self-renewal mechanisms that sustain these populations in the setting of MLL fusion proteins do not require Skida1. Altogether, these data indicate a role for Skida1 in maintaining preleukemic HSC/MPPs, but only after birth.

Skida1 sustains neonatal MLL::ENL-expressing HSCs and MPPs. (A-F) HSC and MPP3/4 numbers for the indicated genotypes in P0 whole liver (A-B), P14 bone marrow (C-D), or P28 bone marrow (E-F). Panels C through F indicate cell numbers for 2 hindlimbs (tibia plus femur). P0: n = 4 (+/+;ME), n = 6 (Δ/+;ME), n = 6 (Δ/Δ;ME); P14: n = 7 (+/+;ME), n = 6 (Δ/+;ME), n = 11 (Δ/Δ;ME); P28: n = 4 (+/+;ME), n = 4 (Δ/+;ME), n = 6 (Δ/Δ;ME). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01 by 1-way ANOVA with the Tukey post hoc test. (G) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for Tet-Off-ME mice of the indicated Skida1 genotypes. n = 6 (+/+), n = 14 (+/+;ME), n = 14 (Δ/+;ME), n = 13 (Δ/Δ;ME). ME, MLL::ENL.

Skida1 sustains neonatal MLL::ENL-expressing HSCs and MPPs. (A-F) HSC and MPP3/4 numbers for the indicated genotypes in P0 whole liver (A-B), P14 bone marrow (C-D), or P28 bone marrow (E-F). Panels C through F indicate cell numbers for 2 hindlimbs (tibia plus femur). P0: n = 4 (+/+;ME), n = 6 (Δ/+;ME), n = 6 (Δ/Δ;ME); P14: n = 7 (+/+;ME), n = 6 (Δ/+;ME), n = 11 (Δ/Δ;ME); P28: n = 4 (+/+;ME), n = 4 (Δ/+;ME), n = 6 (Δ/Δ;ME). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01 by 1-way ANOVA with the Tukey post hoc test. (G) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for Tet-Off-ME mice of the indicated Skida1 genotypes. n = 6 (+/+), n = 14 (+/+;ME), n = 14 (Δ/+;ME), n = 13 (Δ/Δ;ME). ME, MLL::ENL.

Next, we evaluated longitudinal survival of Tet-Off-ME mice after deleting 1 or both Skida1 alleles. Some, but not all, fully transformed Tet-Off-ME AML expressed Skida1 (supplemental Figure 5E). We therefore anticipated a delay but not a complete abrogation of leukemogenesis, given that HSC/MPP depletion in Skida1Δ/Δ;Tet-Off-ME neonates does not extend to pGM/GMP populations, and not all AML express the Skida1 gene. Instead, Skida1 deletion had no effect on survival (Figure 4G). All mice died of morphologically and phenotypically similar AML, irrespective of Skida1 genotype (supplemental Figure 5F). Thus, despite having a role in maintaining neonatal MLL::ENL-expressing HSC/MPPs before the onset of AML, Skida1 is not required for myeloid leukemogenesis. This may reflect the fact that MLLr AML can arise from HSCs, MPPs, pGMs, or GMPs,14,37 yet only MLL::ENL-expressing HSCs and MPPs depend on Skida1.

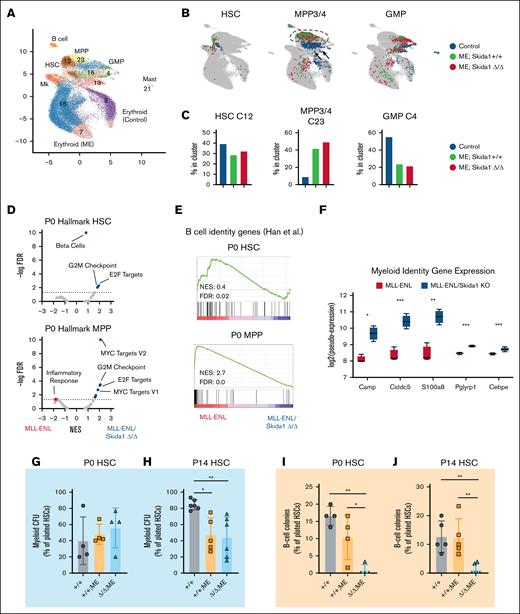

Skida1 deletion causes loss of B-cell identity programs and B-cell potential in neonatal MLL::ENL-expressing HSCs

One explanation for why leukemogenesis proceeds normally in Skida1Δ/Δ;Tet-Off-ME mice, despite neonatal HSC/MPP depletion, is that Tet-Off-ME mice develop AML exclusively, and Skida1 might selectively maintain lymphoid-biased, MLL::ENL-expressing HSC/MPPs. To assess B-cell priming and other population-specific gene expression changes, we performed cellular indexing of transcriptomes and epitopes sequencing on P0 control (Vav1-Cre negative), Skida1+/+;Tet-Off-ME and Skida1Δ/Δ;Tet-Off-ME lineage−c-Kit+ progenitors. We performed the assays at P0 because this time point preceded the depletion of progenitors observed at P14, and it allowed us to capture HSCs in the data set. The data were analyzed by iterative clustering with guide gene selection, version 238 to generate clusters and visualize the data by uniform manifold approximation and projection (Figure 5A). We annotated the clusters based on antigen-derived tags and gene expression as previously described19,39 and identified populations of phenotypic HSCs, MPP3/4, and GMPs (Figure 5B; supplemental Figure 6). Skida1+/+;Tet-Off-ME and Skida1Δ/Δ;Tet-Off-ME progenitors had similar distributions across the uniform manifold approximation and projection and similar frequencies of each cell population (Figure 5B-C). MLL::ENL caused MPP3/4 cluster expansion, at the expense of HSCs and GMPs, irrespective of Skida1 genotype. To identify Skida1-dependent changes in gene expression, we generated pseudobulk populations and compared gene expression in Skida1+/+;Tet-Off-ME and Skida1Δ/Δ;Tet-Off-ME HSC– and MPP3/4-enriched clusters (clusters 12 and 23, respectively; supplemental Tables 4 and 5).40 Gene set enrichment analysis with Hallmark gene sets revealed that Skida1 deletion resulted in modest but significant enrichment of genes associated with cell cycle and metabolism (eg, E2F targets, MYC targets, and G2M checkpoint signatures),41 suggesting either a role for SKIDA1 in cell cycle regulation or changes in the composition of the HSC/MPP populations that manifests as altered cell proliferation (Figure 5D). A B-cell signature was significantly enriched in Skida1+/+;Tet-Off-ME HSCs and MPPs, relative to Skida1Δ/Δ;Tet-Off-ME HSCs and MPPs (Figure 5E). This was accompanied by increased expression of genes associated with myeloid identity (Figure 5F). This observation suggests that Skida1 deletion reduces B-cell priming in newborn, MLL::ENL-expressing HSCs and MPPs, in addition to sustaining HSC/MPP numbers.

Skida1 promotes B-cell priming and supports B-cell potential in MLL::ENL-expressing neonatal progenitors. (A-B) Uniform manifold approximation and projection representing single-cell gene expression in P0 lineage−c-Kit+ cells from control (Vav1-Cre negative), Skida1+/+;Tet-Off-ME, and Skida1Δ/Δ;Tet-Off-ME mice. Cluster identities were assigned by iterative clustering with guide gene selection and are indicated. Cells were annotated based on antigen derived tags and gene expression as shown in supplemental Figure 6. (C) Distribution of cells for each of the indicated genotypes that map to clusters 12 (HSC-enriched), cluster 23 (MPP3/4-enriched), and cluster 4 (GMP-enriched). (D) Volcano plots showing enrichment of Hallmark gene sets within the indicated genotypes as measured by GSEA performed to compare Skida1+/+;Tet-Off-ME and Skida1Δ/Δ;Tet-Off-ME HSCs (cluster 12) and MPP3/4s (cluster 23); n = 4 pseudoreplicates. (E) GSEA plot showing reduced B-cell gene expression in P0 HSC and MPP in the absence of Skida1. (F) Expression of myeloid genes in Skida1+/+;Tet-Off-ME and Skida1Δ/Δ;Tet-Off-ME MPP3/4; n = 4 pseudoreplicates. (G-H) Myeloid CFU frequencies from P0 liver (G) and P14 bone marrow (H) HSCs. P0: n = 4 (+/+), n = 4 (+/+;ME), n = 4 (Δ/Δ;ME); P14: n = 6 (+/+), n = 5 (+/+;ME), n = 6 (Δ/Δ;ME). (I-J) B-cell colony formation frequencies from P0 liver (I) and P14 bone marrow (J) HSCs. P0: n = 4 (+/+), n = 4 (+/+;ME), n = 4 (Δ/Δ;ME); P14: n = 5 (+/+), n = 5 (+/+;ME), n = 6 (Δ/Δ;ME). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01 by 1-way ANOVA with the Tukey post hoc test. KO, knockout; ME, MLL::ENL; Mk, megakaryocyte.

Skida1 promotes B-cell priming and supports B-cell potential in MLL::ENL-expressing neonatal progenitors. (A-B) Uniform manifold approximation and projection representing single-cell gene expression in P0 lineage−c-Kit+ cells from control (Vav1-Cre negative), Skida1+/+;Tet-Off-ME, and Skida1Δ/Δ;Tet-Off-ME mice. Cluster identities were assigned by iterative clustering with guide gene selection and are indicated. Cells were annotated based on antigen derived tags and gene expression as shown in supplemental Figure 6. (C) Distribution of cells for each of the indicated genotypes that map to clusters 12 (HSC-enriched), cluster 23 (MPP3/4-enriched), and cluster 4 (GMP-enriched). (D) Volcano plots showing enrichment of Hallmark gene sets within the indicated genotypes as measured by GSEA performed to compare Skida1+/+;Tet-Off-ME and Skida1Δ/Δ;Tet-Off-ME HSCs (cluster 12) and MPP3/4s (cluster 23); n = 4 pseudoreplicates. (E) GSEA plot showing reduced B-cell gene expression in P0 HSC and MPP in the absence of Skida1. (F) Expression of myeloid genes in Skida1+/+;Tet-Off-ME and Skida1Δ/Δ;Tet-Off-ME MPP3/4; n = 4 pseudoreplicates. (G-H) Myeloid CFU frequencies from P0 liver (G) and P14 bone marrow (H) HSCs. P0: n = 4 (+/+), n = 4 (+/+;ME), n = 4 (Δ/Δ;ME); P14: n = 6 (+/+), n = 5 (+/+;ME), n = 6 (Δ/Δ;ME). (I-J) B-cell colony formation frequencies from P0 liver (I) and P14 bone marrow (J) HSCs. P0: n = 4 (+/+), n = 4 (+/+;ME), n = 4 (Δ/Δ;ME); P14: n = 5 (+/+), n = 5 (+/+;ME), n = 6 (Δ/Δ;ME). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01 by 1-way ANOVA with the Tukey post hoc test. KO, knockout; ME, MLL::ENL; Mk, megakaryocyte.

We tested whether Skida1 deletion alters the myeloid and B-cell potential of MLL::ENL-expressing HSCs by performing myeloid and B-cell colony forming assays. Myeloid colony formation was assessed by sorting single P0 or P14 HSCs into methylcellulose media that contained myeloid and erythroid cytokines and then counting colonies 14 days later. B-cell potential was assessed by sorting single HSCs into media supported by interleukin-7, FMS-related tyrosine kinase 3 ligand, and OP9 stromal cells.19 We analyzed B-cell production 21 days later by flow cytometry (supplemental Figure 7A-B). MLL::ENL had no effect on myeloid colony formation at P0, although it led to a modest reduction in myeloid CFU at P14 (Figure 5G-H). Skida1 deletion had no effect on myeloid CFU at either age (Figure 5G-H). In contrast, Skida1 deletion led to near-complete loss of HSC B-cell potential at both P0 and P14 (Figure 5I-J). Of note, we did not see a reduction in HSC-derived B-cell colonies when Skida1 was deleted on a non–MLL::ENL-expressing background (supplemental Figure 7C). These data show that Skida1 regulates B-cell priming and potential in neonatal MLL::ENL-expressing HSCs.

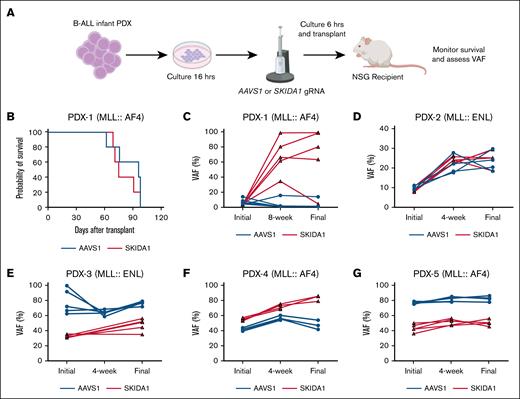

SKIDA1 is not required to sustain fully transformed infant B-ALL

Next, we assessed whether SKIDA1 maintains human B-ALL. We used PDX models, generated from infants with either MLL::ENL or MLL::AF4 leukemias, to test whether SKIDA1 is necessary to sustain infant B-ALL.20,21 We used CRISPR/Cas9 to create targeted insertion-deletion mutations within SKIDA1 (targeting the N-terminal region of the protein) or a noncoding control site within the AAVS1 gene (Figure 6A). Edited cells were then transplanted into immunodeficient NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice. We observed similar levels of human CD45+ AML engraftment between AAVS1-edited and SKIDA1-edited donor cells (supplemental Figure 8A-B). We then monitored recipient survival, recognizing that differences might not be evident due to rapid growth of unedited cells. Indeed, across 5 independent PDX models, we did not observe survival differences between recipients of AAVS1- and SKIDA1-edited cells (Figure 6B, data not shown).

SKIDA1 is not required to sustain infant B-ALL. (A) Experimental design for CRISPR/Cas9-mediated inactivation of SKIDA1 in infant B-ALL PDX. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for NSG recipients of AAVS- or SKIDA1-edited infant B-ALL PDX-1. (C-G) Initial and posttransplant VAF levels in cultured PDX cells (initial, collected at 72 hours after editing), or in engrafted cells at the indicated time points and at time of death (final, 8-12 weeks). Five unique PDX models were evaluated, and the underlying driver mutation is indicated for each (MLL::AF4 or MLL::ENL). PDX-1: n = 5 (AAVS1) and n = 5 (SKIDA1); PDX-2: n = 4 (AAVS1) and n = 5 (SKIDA1); PDX-3: n = 5 (AAVS1) and n = 5 (SKIDA1); PDX-4: n = 4 (AAVS1) and n = 4 (SKIDA1); PDX-5: n = 5 (AAVS1) and n = 5 (SKIDA1).

SKIDA1 is not required to sustain infant B-ALL. (A) Experimental design for CRISPR/Cas9-mediated inactivation of SKIDA1 in infant B-ALL PDX. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for NSG recipients of AAVS- or SKIDA1-edited infant B-ALL PDX-1. (C-G) Initial and posttransplant VAF levels in cultured PDX cells (initial, collected at 72 hours after editing), or in engrafted cells at the indicated time points and at time of death (final, 8-12 weeks). Five unique PDX models were evaluated, and the underlying driver mutation is indicated for each (MLL::AF4 or MLL::ENL). PDX-1: n = 5 (AAVS1) and n = 5 (SKIDA1); PDX-2: n = 4 (AAVS1) and n = 5 (SKIDA1); PDX-3: n = 5 (AAVS1) and n = 5 (SKIDA1); PDX-4: n = 4 (AAVS1) and n = 4 (SKIDA1); PDX-5: n = 5 (AAVS1) and n = 5 (SKIDA1).

We tracked variant allele frequencies (VAFs) in the AAVS1 or SKIDA1 genes before transplant (initial), after engraftment (4 or 8 weeks after transplant), and at the time of death. In the posttransplant periods, human B-ALL cells were isolated by flow cytometry before assessing VAFs. If SKIDA1 is necessary to sustain infant B-ALL, then SKIDA1 VAFs should have declined over time in edited leukemias, even if survival itself was unaffected due to growth of unedited cells. Instead, recipients of 1 PDX model showed expansion of SKIDA1-mutant cells over time, whereas the other 4 PDX models showed relatively stable VAFs over time, with almost all variants reflecting out-of-frame insertion-deletion mutations (Figure 6C-G; supplemental Figure 8A). We did not observe changes in B-cell (CD19) or myeloid (CD33) surface marker expression that would indicate lineage switching within the leukemia (supplemental Figure 8C). SKIDA1 deletion in KOPN-8 cells modestly reduced sensitivity to the menin inhibitor revumenib at low concentrations (supplemental Figure 8D). Thus, although the murine data identify a role for SKIDA1 in sustaining B-cell primed MLLr HSCs, SKIDA1 does not appear necessary to sustain MLLr B-ALL after transformation.

Discussion

Mechanisms that define lineage bias in MLLr leukemias remain poorly understood. Although MLL fusion proteins drive both B-ALL and AML, their prevalence within each leukemia subtype varies with age. For example, B-ALL accounts for 70% to 80% of all MLLr leukemia diagnoses in children aged <1 year.1,25,42,43 At later ages, the incidence MLLr AML exceeds that of infant ALL.25,44 These data suggest that in humans, infancy favors B-cell leukemogenesis. This has been difficult to model in mice due to the strong predilection toward AML, but some mechanisms have been identified. For example, CCL5 expression in adult bone marrow inhibits B-cell leukemogenesis.45 Likewise, fetal-specific Igf2/Igf2r and Fn1/VLA-4 may promote lymphoid bias.46 Mechanisms underlying the lymphoid bias of fetal/neonatal MLLr progenitors are therefore captured in mouse models, even if the models ultimately develop AML.

Here, we identified Skida1 as an effector of fetal/neonatal B-cell priming, specifically in the context of MLL fusion protein expression. SKIDA1 associates with PRC2 yet it has no clear role in normal hematopoiesis. The lack of phenotype in Skida1 deficient mice implies that SKIDA1 has only a limited effect on PRC2 function overall because other PRC2 proteins, such as EED and either EZH1 or EZH2, are required for fetal, neonatal, and adult HSC function.47,48 This may reflect redundancy between SKIDA1 and a structurally similar protein, EPOP.34 In contrast to normal hematopoiesis, SKIDA1 helps sustain MLL::ENL-expressing HSCs and MPPs through neonatal and juvenile stages of life. This dependence is temporally restricted because it does not arise until shortly after birth, and MLL::ENL-expressing MPP numbers recover by P28. SKIDA1 is necessary to support B-cell potential in newborn and neonatal MLL::ENL-expressing HSCs, and it may therefore contribute to infant B-ALL initiation rather than B-ALL maintenance. Unfortunately, the MLL::ENL mouse model is limited in its ability to resolve effects on B-ALL initiation because the mice exclusively develop AML. Humanized models of infant B-ALL might better resolve effects of SKIDA1 on leukemic transformation.13,49,50 SKIDA1 appears to have little to no role in myelopoiesis or myeloid leukemogenesis, unlike other PRC2 proteins.51,52 Thus, SKIDA1 shapes some but not all of the cellular and molecular consequences of MLL fusion protein expression.

These data illustrate how select, age-biased targets of MLL fusion proteins can tune cell fates at different ages. Previous studies have shown that HSCs and MPPs begin acquiring adult-like properties during late gestation, and the transition to adult identity then proceeds gradually through neonatal and juvenile stages of life.53,54 Although MLLr often originate in fetal HSC/MPPs, these data implicate neonatal programs as critical determinants of SKIDA1 dependence and lymphoid bias.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank David Bryder for providing TetO-MLL::ENL mice, J. Michael White for assistance in generating the Skida1 loss-of-function mice, and Jing Ma and Jeffrey Klco for SKIDA1 expression data.

This work was supported by grants (J.A.M.) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL152180), the National Cancer Institute (NCI; R01CA285272), Gabrielle’s Angel Foundation, and the Children’s Discovery Institute of Washington University and St. Louis Children’s Hospital. J.M.-C. was supported by an NCI career development grant (F31CA268923). S.K.T. was supported by NCI U01CA232486 and U01CA243072 awards, a Pennsylvania Department of Health Commonwealth Universal Research Enhancement Program CURE award, and the SchylerStrong Foundation. S.K.T. and J.A.M. are Scholars of Blood Cancer United.

Authorship

Contribution: J.A.M. designed and oversaw all experiments, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript with J.M.-C., who also designed, conducted, and interpreted the experiments; W.Y. performed all bioinformatic analyses; E.D., R.M., E.B.C., and R.M.P. performed the experiments; S.K.T. provided infant leukemia patient-derived xenograft specimens; and all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jeffrey A. Magee, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 S Euclid Ave, St Louis, MO 63110; email: mageej@wustl.edu.

References

Author notes

Sequencing data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession numbers GSE239107 and GSE239108).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.