Key Points

Single-cell proteogenomic analysis of AML PDX models offers the potential to study clonal evolution in response to different therapies.

Cotransplanting multiple primary samples into a single animal can generate PDX models with the desired genetic composition.

Visual Abstract

Clonal heterogeneity in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) can drive drug resistance because different clones may respond variably to treatments. Studying the evolution of these clones under the influence of therapeutic selective pressures is important for designing strategies to overcome drug resistance. Here, we used single-cell proteogenomic analysis to monitor the clonal evolution and differentiation of isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)–mutated AML in patient-derived xenografts (PDX) treated with IDH inhibitors alone or in combination with other antileukemic therapies. Furthermore, we generated mixed PDX models by coengrafting ≥2 leukemic samples into the same animal and used single-cell DNA sequencing to deconvolute their clonal composition. Using these models, we tracked clonal evolution under selective pressure from IDH inhibitors and combination therapies, identifying an association between WT1 mutations and ivosidenib (IDH1 inhibitor) monotherapy resistance, as well as an antagonism between ivosidenib and enasidenib (IDH2 inhibitor) when tested in IDH1-mutated cells. Our findings demonstrate how single-cell proteogenomic analysis of PDX models can illuminate drug resistance mechanisms and inform therapeutic strategies.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) arises from the stepwise accumulation of driver mutations in hematopoietic stem cells and progenitor cells.1,2 Clonality analysis based on bulk DNA sequencing (bDNA-seq) or single-cell DNA sequencing (scDNA-seq) have shown that the clonal architecture of human AML samples can be highly heterogeneous.3-5 This genetic diversity complicates the treatment of AML, because different clones may respond variably to therapies, contributing to treatment resistance and disease relapse.

The generation of patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models has revolutionized the study of AML.6-8 Prior studies have shown that xenografts generally have a more restricted clonal diversity relative to the input leukemia and are usually dominated by one or a few clones.5,9,10 However, a common limitation of these studies was that bDNA-seq analysis was used to infer clonal architecture. It is challenging to accurately assign mutations, especially those with low variant allele frequencies, to specific clonal populations based on bulk sequencing data alone. Single-cell mutational profiling can overcome this limitation. In 1 study using scDNA-seq, Morita et al found that AML xenografts generally recapitulated the diverse genetic populations present in the original AML samples, albeit with differences in their relative proportions.4 Thus, scDNA-seq analysis is required to accurately study the changes in clonal composition of AML xenografts in response to drug therapy. Furthermore, we postulate that the use of scDNA-seq would enable deconvolution of the clonal composition of highly complex models generated by the transplantation of ≥2 patient samples. These mixed PDXs (mPDX) can model the competition and response to treatment between genetically distinct clones that may not be readily identified in individual patient samples.

Here, we used scDNA-seq in combination with surface proteome profiling to monitor changes in the clonal composition and surface immunophenotype of isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1)–mutated AML xenografts in response to ivosidenib (IVO), a mutant IDH1 inhibitor, either as monotherapy or in combination with venetoclax (VEN), azacitidine (AZA), or enasidenib (ENA). Through these studies, we demonstrate the utility of single-cell mutational profiling to track clonal evolution in both traditional single-sample PDX (sPDX) and mPDX models and provide novel insights into mechanisms of IVO resistance.

Methods

Patient samples

All samples were collected before any exposure to IDH inhibitors (supplemental Table 1).

PDX models

Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines approved by the University Health Network Animal Care Committee. Female NSG mice (NOD/SCID/IL2Rγ−/−, RRID:IMSR_JAX:005557), aged 4 to 6 weeks, received 2.25 Gy of irradiation for conditioning. One day after irradiation, 1 × 106 CD3-depleted cells from primary AML samples were transplanted into each conditioned mouse via tail vein or intrafemoral injection. After confirming leukemic engraftment in the BM at week 3 after transplantation, we initiated assigned treatments. Treatment response was monitored through BM sampling by femoral aspiration at baseline (pretreatment) and week 4 after treatment, followed by complete harvest of tibial, femoral, and iliac marrow at week 8 (end point).

Single-cell proteogenomic sequencing

BM samples were thawed, pooled when necessary, and sorted for live human CD45+ cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. The sorted cells were immediately processed for library preparation. For surface protein sequencing, cells were stained with the TotalSeq-D Heme Oncology Cocktail (BioLegend; RRID:AB_2890849), containing antibodies targeting 42 unique surface antigens and 3 isotype control antibodies, plus an additional TotalSeq-D0392 anti-human CD15 antibody (BioLegend; RRID:AB_2904344). After staining, cells were washed and processed using the Tapestri platform as previously described.11 The DNA sequencing panel targeted 127 amplicons across 20 genes commonly mutated in human AML (supplemental Table 2). Variant calling was performed using Mission Bio Tapestri Pipeline v2. Protein data were normalized using centered log-ratio transformation across cells.

Single-cell data analysis and quality control

We filtered out genotype calls with Phred quality scores <30 or sequencing depth <10. To ensure high-quality data, we excluded cells lacking complete pathogenic variant genotyping. In mPDX models, cells carrying combinations of mutations known to be mutually exclusive in patients were marked as doublets and removed. For pseudobulk analysis of surface protein expression, we applied 2-sided Student t tests on normalized protein counts, with P values corrected using the Benjamini-Hochberg method to control for multiple comparisons. Cells passing quality control were assigned to phylogenetic tree clones based on their most descendant mutation. Following the infinite sites assumption,12 wild-type calls for ancestral variants were interpreted as mutant allele dropouts. Additional methods are provided in the supplemental Methods.

Human AML samples from peripheral blood or bone marrow (BM) biopsies were obtained with written consent according to procedures approved by the University Health Network ethics committee and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Tracking clonal evolution at single-cell resolution under the selective pressure of IVO monotherapy or combination therapies

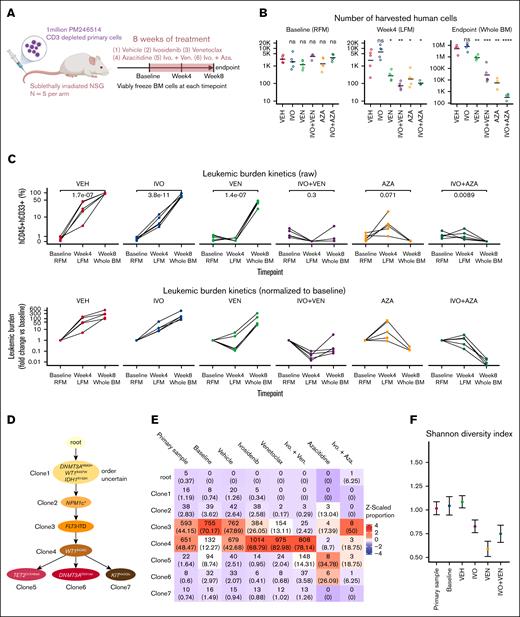

The combinations of IVO+VEN13 and IVO+AZA14 have demonstrated superior efficacy compared with IVO monotherapy in clinical trials. To study how these combination regimens might differentially affect clonal evolution compared with single agents, we generated sPDX models using an IDH1R132H-mutated AML sample (PM246514). After confirmation of engraftment (>0.1% hCD45+/hCD33+ cells in BM), mice were randomly assigned to 1 of 6 treatment groups (n = 5 each): vehicle control, IVO, VEN, AZA, IVO+VEN, or IVO+AZA (Figure 1A). We monitored disease progression and treatment effect in BM samples collected at baseline (pretreatment) and at 4 weeks and 8 weeks after treatment initiation. The absolute number and proportion of leukemic cells in BM were similar between the treatment arms at baseline (Figure 1B-C). During the 8-week treatment period, leukemic burden progressively increased in vehicle-treated animals (Figure 1C). IVO monotherapy had minimal effect on leukemic progression; however, its combination with VEN or AZA reduced the absolute number and proportion of leukemic cells to a greater degree than single agents (Figure 1B-C). The IVO+VEN combination blocked the rapid expansion of resistant cells from week 4 to week 8 in the VEN monotherapy arm (Figure 1C). These findings show that IVO+VEN and IVO+AZA were more effective at lowering leukemic burden than single agents in our IDH1-mutated AML sPDX model.

Tracking clonal evolution at single-cell resolution under the selective pressure of IVO monotherapy or combination therapies. (A) Schematic of experiment. (B) Dot plot showing the number of human leukemic cells (defined as hCD45+/hCD33+) collected from each animal across the indicated treatments and timepoints. The horizontal bar represents the mean. The y-axis is in log-scale. Statistical significance was determined using unpaired 2-sided Student t test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; not significant (ns). (C) Dot plot showing the raw (top) and normalized (bottom) leukemic burden (% hCD45+/hCD33+ gated on all live cells) in the BM across the indicated treatments and time points. Each line connects data from the same mouse. Statistical significance was determined using unpaired 2-sided Student t test. (D) Reconstructed phylogenetic tree showing the sequence of mutations acquired by PM246514. (E) Heat map showing the number of cells sequenced from each clone (with the corresponding proportion shown in parentheses) across the clones defined in panel D for each sample. The baseline sample is a pool of all 30 mice before any treatment. The color represents the z-scaled proportion of each clone within each sample. (F) Dot plot and error bar showing the posterior mean and 95% credible interval of the Shannon diversity index of the indicated samples. (G) Density plot showing the posterior distribution of log2 fold changes in the number of leukemic cells collected from each animal for each treatment group and clone, compared to the vehicle control. Values represent log2 fold changes with statistical significance in parentheses: ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001; ns. LFM, left femur; RFM, right femur.

Tracking clonal evolution at single-cell resolution under the selective pressure of IVO monotherapy or combination therapies. (A) Schematic of experiment. (B) Dot plot showing the number of human leukemic cells (defined as hCD45+/hCD33+) collected from each animal across the indicated treatments and timepoints. The horizontal bar represents the mean. The y-axis is in log-scale. Statistical significance was determined using unpaired 2-sided Student t test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; not significant (ns). (C) Dot plot showing the raw (top) and normalized (bottom) leukemic burden (% hCD45+/hCD33+ gated on all live cells) in the BM across the indicated treatments and time points. Each line connects data from the same mouse. Statistical significance was determined using unpaired 2-sided Student t test. (D) Reconstructed phylogenetic tree showing the sequence of mutations acquired by PM246514. (E) Heat map showing the number of cells sequenced from each clone (with the corresponding proportion shown in parentheses) across the clones defined in panel D for each sample. The baseline sample is a pool of all 30 mice before any treatment. The color represents the z-scaled proportion of each clone within each sample. (F) Dot plot and error bar showing the posterior mean and 95% credible interval of the Shannon diversity index of the indicated samples. (G) Density plot showing the posterior distribution of log2 fold changes in the number of leukemic cells collected from each animal for each treatment group and clone, compared to the vehicle control. Values represent log2 fold changes with statistical significance in parentheses: ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001; ns. LFM, left femur; RFM, right femur.

To determine the impact of different treatments on clonal composition in vivo, we performed scDNA-seq using the Tapestri platform on human-enriched cells harvested at baseline (pooled from all 30 mice) and end point (pooled from mice in each treatment arm), as well as the input primary AML sample. Because variant calling from scDNA-seq data can be error prone,15 we performed targeted bDNA-seq of a BM sample from PM246514-engrafted mice at 1511× average depth. This revealed 33 high confidence variants, with 32 also detected by scDNA-seq in the pooled vehicle-treated sample (supplemental Figure 1A-B). From the list of 32 high confidence variants, we focused on 9 mutations that are known or predicted to be pathogenic to reconstruct the phylogenetic tree of PM246514. The analysis revealed an initial linear evolutionary path, with early acquisition of DNMT3Ap.R882H, WT1p.R467W, and IDH1p.R132H mutations. This was followed by the sequential acquisition of NPM1p.Trp288Cysfs∗12, FLT3-ITD, and WT1p.R439C mutations. The second WT1p.R439C mutation was found to occur in cis with the first WT1p.R467W mutation, as determined by long-range polymerase chain reaction, cloning, and sequencing. Three subclones branched off at the end of this linear path, with each acquiring either a TET2p.Q1548del, DNMT3Ap.D531del, or KITp.H40QfsTer6 mutation (Figure 1D).

The overall clonal composition of the input primary sample and pooled sample from vehicle-treated animals at end point were remarkably similar, with 2 dominant clones (clone 3 and clone 4) present in similar proportions (Figure 1E). Although clone 4 was initially smaller in the baseline sample than the vehicle-treated sample, it eventually reached a proportion comparable to the input sample, suggesting slower expansion kinetics (Figure 1E). Treatment with single-agent IVO resulted in contraction of clone 3 and expansion of clone 4 relative to other clones (Figure 1E) and a corresponding decrease in clonal diversity as measured by the Shannon diversity index (Figure 1F). A similar change in clonal composition and diversity was observed with single-agent VEN and IVO+VEN treatments (Figure 1E-F). In contrast, although analysis of samples treated with single-agent AZA or IVO+AZA was challenged by the limited number of human cells recovered (Figure 1B), we did not observe a clear selection for any of the surviving clones (Figure 1E). To better assess how different clones responded to treatment, we developed a hierarchical multinomial Bayesian model that estimated the fold change in absolute cell numbers for each clone relative to vehicle treatment. This analysis revealed that both single-agent VEN and IVO+VEN were generally more effective in targeting earlier-stage clones (clones 1-3) than later-stage clones (clones 4-7; Figure 1G). In contrast, single-agent AZA and IVO+AZA were effective in eliminating clone 4 as well as earlier-stage clones (Figure 1E,G). Notably, the IVO+AZA combination was effective in reducing all the clones by approximately the same magnitude, including clones 5 and 6, which demonstrated a lower sensitivity to AZA monotherapy (Figure 1E,G). Given that the WT1p.R434C mutation, acquired in clone 4, distinguishes early- from late-stage clones (Figure 1D), these findings suggest that WT1 mutations may contribute to IVO and VEN resistance, which AZA can potentially overcome.

WT1 knockout confers resistance to IVO-induced differentiation

To investigate the role of WT1 mutations in IVO resistance, we generated knockout mutations in exon 7 of the Wt1 gene using a multiguide CRISPR/Cas9 approach in OCI-mIDH1/N cells (supplemental Figure 2A). This murine hematopoietic progenitor cell line carries the IdhR132H and Npm1 mutations and differentiates in response to IVO treatment.16 We selected exon 7, which is highly conserved between human and mouse,17 for targeting because it is the most frequently mutated region of WT1 in human myeloid neoplasms.18 Treatment of nonedited OCI-mIDH1/N cells with IVO upregulated the expression of the Fcγ receptors CD16/32 (supplemental Figure 2B). In contrast, Wt1 knockout OCI-mIDH1/N cells had a diminished differentiation response to IVO (supplemental Figure 2B). These findings suggest that WT1 loss of function contributes to IVO resistance.

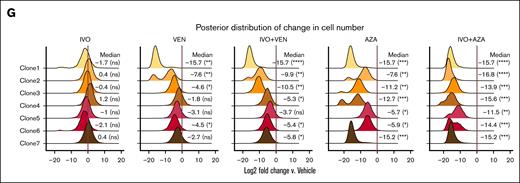

Single-cell analysis of the impact of IVO treatment on the surface proteome

IVO monotherapy had minimal impact on leukemic burden in the above sPDX model (Figure 1B-C). However, given that IVO exerts its primary antileukemic effect by triggering cellular differentiation as opposed to cytotoxicity, changes in leukemic burden might not be an appropriate readout of treatment effects. To assess the impact of IVO on the differentiation state of the different clones, we performed single-cell protein sequencing to profile the expression of 43 surface markers on the vehicle and IVO-treated samples using the Tapestri platform.11,19 Pseudobulk analysis of the single-cell data revealed a total of 18 differentially expressed proteins, 10 of which were higher and 8 lower in IVO-treated cells (Figure 2A). The most significantly upregulated protein was CD69, a C-type lectin receptor,20 the significance of which is unclear in the context of AML differentiation. The most significantly downregulated protein was the stem cell marker CD117 (c-KIT), suggestive of a decrease in stemness properties after IVO treatment. However, the overall magnitude of change for both proteins was relatively modest (Figure 2B). This modest effect could be attributed to co-occurring mutations in WT1, as demonstrated by our findings, and/or FLT3, which have previously been linked to resistance to IVO monotherapy.21,22 We did not observe obvious differences in the protein response to IVO treatment between the different genetic subclones (Figure 2C).

Single-cell analysis of the impact of IVO treatment on the surface proteome. (A) Volcano plot showing the pseudobulk analysis of differentially expressed proteins in IVO vs vehicle (VEH). (B) Ridgeline plots of normalized CD117 and CD69 expression in the indicated samples. (C) Heat map showing clone-specific differences in the expression of proteins that are significantly differentially expressed (FDR <0.05) between IVO and VEH, based on pseudobulk analysis. The proteins are ordered by hierarchical clustering. (D) Dot plots showing flow cytometry analysis of the expression of the myeloid differentiation markers CD11b, CD14, and CD15, as well as granularity (side-scatter), on human CD45+ cells collected from mice BM at end point (n = 3-5 per arm). Statistical significance was determined using unpaired 2-sided Student t test. CLR, centered log ratio; Diff., difference; FDR, false discovery rate.

Single-cell analysis of the impact of IVO treatment on the surface proteome. (A) Volcano plot showing the pseudobulk analysis of differentially expressed proteins in IVO vs vehicle (VEH). (B) Ridgeline plots of normalized CD117 and CD69 expression in the indicated samples. (C) Heat map showing clone-specific differences in the expression of proteins that are significantly differentially expressed (FDR <0.05) between IVO and VEH, based on pseudobulk analysis. The proteins are ordered by hierarchical clustering. (D) Dot plots showing flow cytometry analysis of the expression of the myeloid differentiation markers CD11b, CD14, and CD15, as well as granularity (side-scatter), on human CD45+ cells collected from mice BM at end point (n = 3-5 per arm). Statistical significance was determined using unpaired 2-sided Student t test. CLR, centered log ratio; Diff., difference; FDR, false discovery rate.

We queried whether the addition of AZA or VEN to IVO could trigger a more robust differentiation response. Due to the very low number of viable cells recovered from the remaining 4 treatment arms, surface proteome profiling using the Tapestri platform was not feasible. As such, we used flow cytometry to measure the expression of 3 myeloid differentiation markers (CD11b, CD14, and CD15) on the residual leukemic population and their granularity (side-scatter) at end point across all treatment arms. Consistent with the single-cell protein sequencing data, IVO monotherapy had no significant impact on the expression of CD11b or CD14 and only increased CD15 and granularity by a small magnitude in this model (Figure 2D). However, the combination IVO+AZA, but not IVO+VEN, strongly upregulated the expression of all 3 myeloid markers to a greater extent than with either single agent (Figure 2D). These findings suggest that AZA and IVO could synergize to overcome the differentiation block in IDH1-mutated AML cells with multiple genetic alterations.

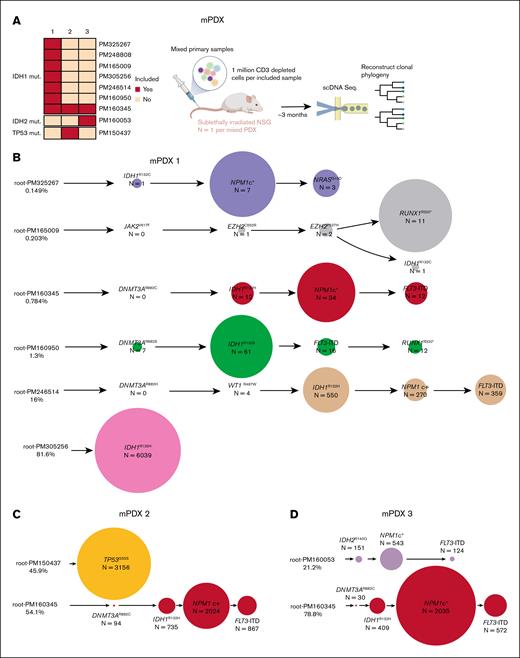

Single-cell deconvolution of mPDX models

To engineer xenografts with specific genetic compositions, we developed mPDX models by cotransplanting multiple AML samples into individual mice. As a proof of concept, we generated 3 mPDX models, each containing at least 1 IDH1-mutated sample (Figure 3A). All cotransplanted samples were confirmed to engraft NSG mice individually (supplemental Figure 3) and harbored mutually exclusive combination of variants that enabled us to bioinformatically deconvolute the sample origin of each cell (supplemental Figure 4A-C). The first mPDX model was generated by transplanting a mixture of 7 IDH1-mutated primary AML samples in equal proportions (Figure 3A; supplemental Table 1). By leveraging the unique mutational fingerprint of each sample, we were able to determine the sample of origin for each sequenced cell and reconstruct the phylogenetic tree of each engrafted sample (Figure 3B). Leukemic cells from PM305256 emerged as the dominant clone, accounting for 81.6% of the sequenced cells (Figure 3B). Five samples engrafted at lower proportions and 1 sample (PM248808) was not detected. The other 2 mPDX models were generated by cotransplanting PM160345, an IDH1-mutated AML sample, with a second AML sample carrying either a TP53p.I255S or an IDH2p.R140Q mutation (Figure 3C-D). These results demonstrate the potential of combining mPDX models with scDNA-seq to investigate clonal competition among populations with specific genetic compositions.

Single-cell deconvolution of mPDX models. (A) Schematic showing the generation of mPDX models. (B-D) Reconstructed phylogenetic tree of each of the mPDX models. The circle size is scaled within each sample in panel B and across both samples in panels C-D. mut, mutated.

Single-cell deconvolution of mPDX models. (A) Schematic showing the generation of mPDX models. (B-D) Reconstructed phylogenetic tree of each of the mPDX models. The circle size is scaled within each sample in panel B and across both samples in panels C-D. mut, mutated.

Monitoring clonal evolution at single-cell resolution in an mPDX model of mutant IDH isoform switching

Restoration of (R)-2-hydroxyglutarate (R-2-HG) production is one of the mechanisms by which IDH1/2-mutated AML acquires resistance to mutant IDH inhibitors.22,23 This can be achieved through a process called isoform switching, in which an IDH2 mutation emerges under the selection pressure of mutant IDH1 inhibitors or vice versa.23 In a study of relapsed or refractory IDH1-mutated AML treated with IVO monotherapy, isoform switching was observed in 12% of the patients who experienced disease relapse or progression.22 In the same study, scDNA-seq analysis showed that IDH2 mutations can be found in cells distinct from the IDH1-mutated clone. The generation of traditional sPDX models to model this mode of isoform switching would be challenging because it requires the identification of an IDH1-mutated sample with a separate coexisting IDH2-mutated clone before treatment initiation, which occurs infrequently.22

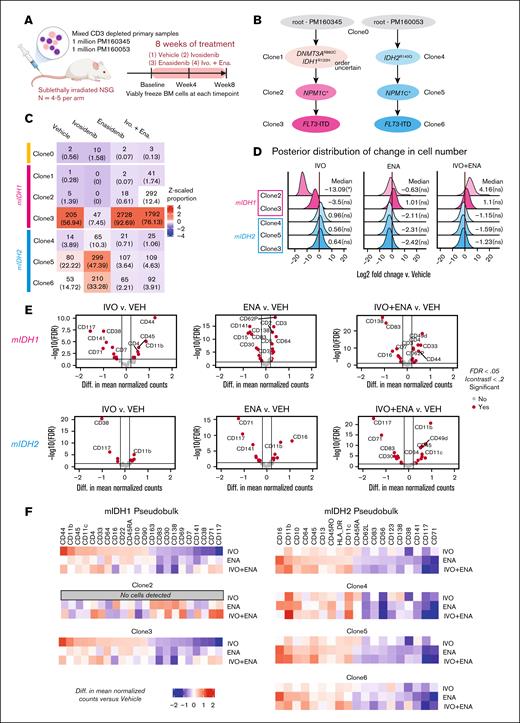

To overcome this limitation, we used our above-described IDH1p.R132H/IDH2p.R140Q mPDX to model isoform switching in both directions by treating the animals with either IVO or ENA, a mutant IDH2 inhibitor.24 We also used this mPDX model to test whether concurrent dual mutant IDH1 and IDH2 inhibition (IVO+ENA) is a potential strategy to overcome isoform switching, as previously suggested.23 We generated the mPDXs by transplanting equal proportions of IDH1-mutated cells (PM160345) and IDH2-mutated cells (PM160053) IV into conditioned NSG mice. After confirmation of leukemic engraftment in the BM at 3 months after transplantation, animals were randomized to receive 1 of 4 treatments (n = 4-5 per arm): (1) vehicle control, (2) IVO, (3) ENA, or (4) IVO+ENA for 8 weeks (Figure 4A). We collected BM cells at baseline (immediately before treatment), 4 weeks after treatment by femoral aspiration, and 8 weeks after treatment (end point) by harvesting total BM cells from the tibias, femurs, and ilia (supplemental Figure 5).

Monitoring clonal evolution at single-cell resolution in an mPDX model of mutant IDH isoform switching. (A) Schematic of experiment. (B) Annotated phylogenetic tree showing the sequence of mutations acquired by the “isoform switching” model. (C) Heat map showing the number of cells sequenced from each clone (with the corresponding proportion shown in parentheses) across the clones defined in panel B for each sample. The color represents the z-scaled proportion of each clone within each sample. (D) Density plot showing the posterior distribution of log2 fold changes in the number of leukemic cells collected from each animal for each treatment group and clone, compared to the vehicle control. Values represent log2 fold changes with statistical significance in parentheses: ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001; ns. (E) Volcano plot showing the pseudobulk analysis of differentially expressed proteins in each treatment arm vs VEH. Cells derived from PM160345 (top) and PM160053 (bottom) were analyzed separately. (F) Heat maps showing pseudobulk and clone-specific differences in protein expression between each treatment group and the VEH control. Cells derived from PM160345 (left) and PM160053 (right) were analyzed separately. FDR, false discovery rate.

Monitoring clonal evolution at single-cell resolution in an mPDX model of mutant IDH isoform switching. (A) Schematic of experiment. (B) Annotated phylogenetic tree showing the sequence of mutations acquired by the “isoform switching” model. (C) Heat map showing the number of cells sequenced from each clone (with the corresponding proportion shown in parentheses) across the clones defined in panel B for each sample. The color represents the z-scaled proportion of each clone within each sample. (D) Density plot showing the posterior distribution of log2 fold changes in the number of leukemic cells collected from each animal for each treatment group and clone, compared to the vehicle control. Values represent log2 fold changes with statistical significance in parentheses: ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001; ns. (E) Volcano plot showing the pseudobulk analysis of differentially expressed proteins in each treatment arm vs VEH. Cells derived from PM160345 (top) and PM160053 (bottom) were analyzed separately. (F) Heat maps showing pseudobulk and clone-specific differences in protein expression between each treatment group and the VEH control. Cells derived from PM160345 (left) and PM160053 (right) were analyzed separately. FDR, false discovery rate.

To determine the treatment effects on clonal composition and differentiation response, we performed scDNA+protein sequencing on hCD45+ human cells sorted from the BM samples at end point (pooled from mice in each treatment arm). Based on the scDNA-seq results, we determined the sample origin of each cell and the evolutionary path of each sample (Figure 4B). In the vehicle-treated sample, the proportions of IDH1- and IDH2-mutated cells were 58.6% and 40.8%, respectively (Figure 4C). Treatment with single-agent IVO resulted in a reduction in the proportion of IDH1-mutated clones (clones 2-3) and a corresponding increase in the proportion of IDH2-mutated clones (clones 4-6) relative to vehicle treatment (Figure 4C). Conversely, ENA monotherapy led to a decrease in the proportion of IDH2-mutated clones and an increase in the proportion of IDH1-mutated clones compared with vehicle treatment (Figure 4C). The absolute cell numbers of the IDH1- and IDH2-mutated clones, determined based on their proportions and absolute numbers of leukemic cells harvested at the end of treatment, were reduced with IVO or ENA monotherapy, respectively, compared with vehicle treatment (Figure 4D). The absolute cell numbers of the nontargeted clones remained largely unaffected. In this model, IVO+ENA combination treatment reduced both the proportion and absolute cell numbers of IDH2-mutated clones, although the magnitude of reduction appeared lower than that of ENA monotherapy (Figure 4C-D). Although IVO monotherapy reduced the absolute numbers of IDH1-mutated clones, the IVO+ENA combination failed to show this effect (Figure 4D).

To determine whether the above findings correlated with differentiation response, we analyzed the protein sequencing data to profile the expression of 43 surface markers on cells from the 4 treatment arms. We found that IVO monotherapy significantly increased the expression of myeloid differentiation markers such as CD11b, CD11c, and CD64 and decreased the expression of stem/progenitor markers such as CD117 and CD7125 on IDH1-mutated cells in clone 3 (Figure 4E-F), consistent with a robust differentiation response. We observed a similar trend with ENA monotherapy on IDH2-mutated cells, with the upregulation of myeloid differentiation markers such as CD16, CD11b, CD64, CD13, and CD11c and the downregulation of stem/progenitor markers such as CD117 and CD71 (Figure 4E-F). The impact of ENA on surface protein expression was largely consistent across different IDH2-mutated clones (ie, clones 4-6; Figure 4F). IVO and ENA monotherapies also changed the expression of some surface proteins on their corresponding nontargeted cell populations. This effect was most pronounced with IVO monotherapy on IDH2-mutated cells, in which some of the changes included an upregulation of CD11b and downregulation of CD117 (Figure 4E-F). The impact of ENA+IVO on the expression of differentiation and stem cell/progenitor markers on IDH2-mutated clones was largely similar to that of ENA monotherapy (Figure 4E-F). However, IDH1-mutated cells showed less pronounced changes in the expression of these markers with ENA+IVO compared to IVO monotherapy (Figure 4E-F). These findings suggest that concurrent treatment with ENA may diminish IVO’s effects.

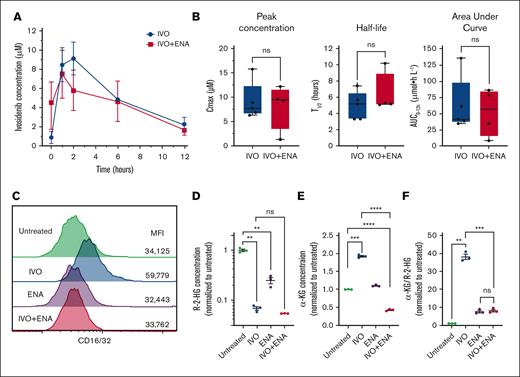

ENA suppresses IVO-induced differentiation of IDH1-mutated cells

One potential explanation for the reduced IVO efficacy could be drug-drug interactions that decrease IVO exposure in vivo. To test this hypothesis, we conducted pharmacokinetic (PK) studies by administering IVO alone or concurrently with ENA for 7 days in NSG mice. Plasma concentrations of both compounds were measured after the final IVO dose. PK analysis revealed no significant effect of ENA coadministration on IVO's peak concentration, half-life time (t1/2), and area under curve from 0 to 12 hours (Figure 5A-B; supplemental Figure 6). Although this shorter treatment duration differed from our 8-week treatment studies, these results suggest that reduced IVO exposure was unlikely to explain the diminished efficacy. To further investigate the mechanism, we tested the direct impact of ENA on IVO’s effects in Idh1-mutated OCI-mIDH1/N cells using relevant drug concentrations based on our PK findings (5 μM for IVO and 15 μM for ENA). Consistent with our in vivo findings, concurrent treatment with ENA suppressed the differentiation response to IVO in OCI-mIDH1/N cells, as measured by CD16/32 expression (Figure 5C). Given that IVO acts by alleviating the inhibition of α-ketoglutarate (α-KG)–dependent dioxygenases, which are activated by α-KG and inhibited by R-2-HG, we hypothesized that the reduced differentiation response to IVO in the presence of ENA could be attributed to a failure to suppress R-2-HG and/or a decline in α-KG levels. To test this hypothesis, we measured intracellular R-2-HG and α-KG concentrations in OCI-mIDH1/N cells treated with IVO alone (5 μM), ENA alone (15 μM), IVO+ENA combination, or left untreated as controls. The combination treatment reduced R-2-HG concentrations to a similar extent as IVO alone (Figure 5D), ruling out compromised mutant IDH1 inhibition as the underlying mechanism. ENA alone also decreased R-2-HG levels, albeit to a lesser degree than IVO (Figure 5D). In contrast, although IVO treatment alone increased α-KG concentrations relative to untreated controls, the combination treatment not only prevented this elevation but decreased α-KG below baseline levels, resulting in ∼20% of the concentration seen with IVO treatment alone (Figure 5E). To assess the relative balance of treatment-induced changes, we calculated the ratio of α-KG to R-2-HG. IVO alone substantially increased this ratio compared to untreated controls (Figure 5F). However, the combination treatment led to a markedly smaller increase in this ratio, comparable to that observed with ENA alone (Figure 5F). These findings suggest that cotreatment with ENA suppresses IVO-induced differentiation by depleting α-KG availability, thereby impairing α-KG–dependent dioxygenase activity, despite the concurrent reduction in 2-HG levels.

Impact of concurrent ENA treatment on PK and differentiation efficacy of IVO. (A) Plasma concentrations of IVO measured at baseline (0 hour) and at 1, 2, 6, and 12 hours after the final dose in mice receiving IVO alone or IVO+ENA combination. Data represent mean values from 5 mice (IVO alone) and 4 mice (IVO+ENA). Error bars indicate standard error of the mean (SEM). (B) PK parameters including peak concentration (Cmax), half-life (t1/2), and area under the curve (AUC0-12hr) for IVO in mice treated with IVO alone (n = 5) or IVO+ENA combination (n = 4). The box represents the interquartile range, with the median indicated by the line inside the box. Whiskers extend to the minimum and maximum values. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of CD16/32 expression levels on OCI-mIDH1/N cells left untreated or treated with IVO (5 μM), ENA (15 μM), or both compounds for 5 days. Values represent MFI. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (D) Intracellular R-2-HG concentrations in OCI-mIDH1/N cells from experiment in panel C. Data are normalized to untreated control samples and shown as mean ± SEM. (E) Intracellular α-KG concentrations in OCI-mIDH1/N cells from experiment in panel C. Data are normalized to untreated control samples and shown as mean ± SEM. (F) Ratio of α-KG to R-2-HG in OCI-mIDH1/N cells from experiment in panel C. Data are normalized to untreated control samples and shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined using unpaired 2-sided Student t test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001; ns. MFI, median fluorescence intensity.

Impact of concurrent ENA treatment on PK and differentiation efficacy of IVO. (A) Plasma concentrations of IVO measured at baseline (0 hour) and at 1, 2, 6, and 12 hours after the final dose in mice receiving IVO alone or IVO+ENA combination. Data represent mean values from 5 mice (IVO alone) and 4 mice (IVO+ENA). Error bars indicate standard error of the mean (SEM). (B) PK parameters including peak concentration (Cmax), half-life (t1/2), and area under the curve (AUC0-12hr) for IVO in mice treated with IVO alone (n = 5) or IVO+ENA combination (n = 4). The box represents the interquartile range, with the median indicated by the line inside the box. Whiskers extend to the minimum and maximum values. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of CD16/32 expression levels on OCI-mIDH1/N cells left untreated or treated with IVO (5 μM), ENA (15 μM), or both compounds for 5 days. Values represent MFI. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (D) Intracellular R-2-HG concentrations in OCI-mIDH1/N cells from experiment in panel C. Data are normalized to untreated control samples and shown as mean ± SEM. (E) Intracellular α-KG concentrations in OCI-mIDH1/N cells from experiment in panel C. Data are normalized to untreated control samples and shown as mean ± SEM. (F) Ratio of α-KG to R-2-HG in OCI-mIDH1/N cells from experiment in panel C. Data are normalized to untreated control samples and shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined using unpaired 2-sided Student t test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001; ns. MFI, median fluorescence intensity.

Discussion

We used scDNA-seq and protein sequencing to track clonal evolution in AML PDX models treated with IDH inhibitors as monotherapy or in combination with other antileukemic therapies. We demonstrated that PDX models can recapitulate the clonal diversity of input leukemic samples. Furthermore, we showed that the engrafted leukemia can be “engineered” to achieve specific genetic compositions by coengrafting ≥2 leukemic samples into the same animal host.

We studied the impact of IVO+VEN and IVO+AZA, as well as single agents, on the clonal evolution and disease burden of an IDH1-mutated PDX model. Recent clinical studies provide important context for our findings. In newly diagnosed IDH1-mutated AML, VEN+AZA achieved a modest complete remission (CR) rate of 27%,26 whereas IVO+AZA demonstrated a higher CR rate of 47% in the phase 3 AGILE trial.14 A real-world study also showed superior outcomes with IVO+hypomethylating agent (HMA) compared to VEN+HMA (CR, 42.5% vs 26.3%; composite CR + CR with incomplete hematological recovery, 63.0% vs 48.5%).27 In our model, IVO+AZA also appeared more active than IVO+VEN, but whether this difference extends broadly to patients remains uncertain, because IVO+VEN was also highly effective.13 Emerging evidence suggests that the triplet combination of IVO+AZA+VEN may be the most effective strategy for eliminating diverse leukemic clones in IDH1-mutated AML, with early-phase clinical data reporting composite CR + CR with incomplete hematological recovery + CR with partial hematological recovery (CRh) rates of up to 86%.13

Single-cell mutation analysis and Bayesian modeling of the IDH1-mutated PDX model revealed that clones with 2 WT1 mutations exhibited greater resistance to single-agent IVO and VEN than clones with 1 WT1 mutation. The 2 WT1 mutations, both of which are in the DNA-binding domain of the transcription factor, were found to occur in cis, suggesting that they act in concert to modulate WT1 function to a greater extent than each alone. Using an Idh1-mutated murine cell line model, we found that disruption of the Wt1 gene suppressed the differentiation response to IVO. The resistance mechanism likely stems from WT1's role in facilitating TET2 activity,28 in which WT1 mutations directly reduce TET2 activity, diminishing the leukemic cell's reliance on 2-HG–mediated TET2 suppression to maintain its undifferentiated state. However, the clinical relevance of WT1 mutations on IVO sensitivity in patients remains uncertain. Although a previous cohort study of 167 IDH1-mutated relapsed/refractory patients with AML treated with IVO monotherapy showed that none of the 6 patients with WT1 mutations achieved CR or CRh compared to a 35% CR + CRh rate (57/161) in patients without WT1 mutations, this difference was not statistically significant (P = .096).22 Additional studies with larger cohorts are needed to definitively establish whether WT1 mutations contribute to IVO resistance in patients.

Using mPDX models with IDH1/IDH2 mutations, we investigated isoform switching under IVO alone, ENA alone, or combination therapy. Single agents produced expected outcomes, but concurrent ENA attenuated IVO-induced differentiation in IDH1-mutated cells. Using the Idh1-mutated OCI-mIDH1/N cell line model, we discovered opposing effects on α-KG levels, with IVO monotherapy increasing α-KG and combination treatment decreasing it. Because α-KG serves as a critical cofactor for α-KG–dependent dioxygenases, its reduced availability would be expected to impair their activity even when R-2-HG levels are low, thereby maintaining the differentiation block. This effect on α-KG levels may result from the combined off-target inhibitory effects of IVO and ENA on wild-type IDH1 and IDH2 enzymes' oxidative activity (isocitrate to α-KG conversion). Although less potent against wild type compared to mutant enzymes,24,29 their combination may work together to compromise the cellular capacity for α-KG production. Given that similar effects would be expected in IDH2-mutated cells under combination treatment, the reduced antagonism observed in these cells in our mPDX model suggests that additional or alternative mechanisms may be at play, depending on the specific mutational context.

There are several limitations of our study. First, a limited number of patient samples were studied, which may affect the general applicability of our findings. Second, the samples used to generate mPDX need to harbor mutational profiles that are sufficiently distinct from each other so that the sample origin of each cell can be identified with a high level of confidence. Lastly, in the mPDX models, the differential responses to therapies between clones may be influenced by factors beyond their mutation profiles, because these clones originate from different leukemias.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the staff at the Princess Margaret Leukemia Tissue Bank and the patients for donating the samples used in this study. The authors also thank the Princess Margaret Flow Cytometry Core Facility for their assistance with cell sorting. Furthermore, the authors appreciate the valuable support provided by Mission Bio in optimizing the workflow and proofreading the manuscript.

This study was supported by funding from Servier Pharmaceuticals.

Authorship

Contribution: A.C.H.L., S.C., Y.Y., and L.L. performed animal experiments; F.A., A.Abow, and G.B. performed library preparation and sequencing; D.M.A., D.L.D., A.M., E.G., M.H., and V.W. contributed to data collection; T.K., B.N., D.M.M., and A.E.T. were involved in planning the experiments; A.Arruda and M.D.M. provided the primary samples used in this study; A.C.H.L. performed computational analysis and data visualization; A.C.H.L. and S.M.C. wrote the manuscript; and S.M.C. conceptualized the experiments, supervised the project, and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for B.N. is Parabilis Medicines, Cambridge, MA.

Correspondence: Steven M. Chan, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, Princess Margaret Cancer Research Tower, 101 College St, Room 8-354, Toronto, ON M5G 1L7, Canada; email: steven.chan@uhn.ca.

References

Author notes

A.C.H.L., S.C., and D.M.A. contributed equally to this work.

Raw single-cell DNA + antibody-derived tags (ADTs) sequencing data generated in this study have been deposited in Figshare (https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Single-cell_proteogenomic_analysis_of_clonal_evolution_in_PDX_models_of_AML_treated_with_IDH_inhibitors/30356587) in H5 format. FASTQ files are not available because of patient privacy restrictions.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.