Key Points

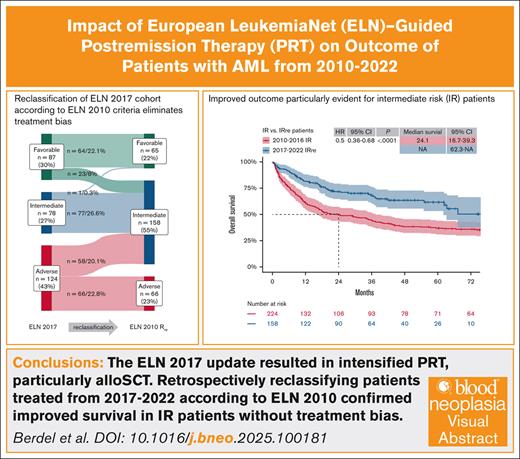

The ELN 2017 update led tointensified PRT, mainly allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant, improving survival of patients with AML.

Reclassifying patients treated from 2017 to 2022 according to ELN 2010 confirmed improved survival in IR patients without treatment bias.

Visual Abstract

The European LeukemiaNet (ELN) classification for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) incorporates cytogenetic and mutational risk profiles of AML to define separate risk groups that correlate with survival outcomes. Recommendations for postremission treatment (PRT) intensity, mainly allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant, are based on these risk groups. In-depth genetically defined cohorts of registries or clinical trials, often reported as retrospective real-world validation cohorts, contain an inherent bias as patients were not treated according to recommendations matching time intervals of the respective ELN classification. We analyzed 662 patients with AML who received intensive induction therapy at our center between 2010 and 2022. Patients were classified according to ELN 2010 if treated between 2010 and 2016, and ELN 2017 if treated between 2017 and 2022. Overall survival (OS) and relapse-free survival (RFS) significantly improved for patients treated between 2017 and 2022 compared with those treated between 2010 and 2016 (4-year OS, 60% vs 40%; 4-year RFS, 54% vs 35%). To eliminate treatment bias, patients treated between 2017 and 2022 were retrospectively reclassified for genetic risk according to ELN 2010 and compared with regularly classified patients treated between 2010 and 2016. The improved outcome was particularly evident for intermediate-risk (IR) patients, whereas favorable and adverse subgroups showed no significant difference. This is, to our knowledge, the first analysis examining the impact of ELN-guided PRT in the context of treatment algorithms applied in the respective ELN time period. We conclude that the shift of risk groups between ELN 2010 and 2017, along with the resulting intensified PRT, contributed to significantly improved survival of patients with AML, particularly those with IR.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a heterogeneous diagnostic category, driven by a variety of genetic aberrations that impact on the treatment outcome of patients1-3 (for review, see DiNardo and Lachowiez,4 and Shimony et al5). The European LeukemiaNet (ELN) classification of AML incorporates cytogenetic and mutational risk profiles of AML to define separate genetic risk groups.2,6,7 In particular, AML postremission treatment (PRT), including allogeneic stem cell transplant (alloSCT), is selected based on these defined risk groups. Periodical updates of the ELN classification and recommendations reflect our increasing understanding of genetic risk factors and their prognostic impact on patients with AML. The first ELN classification was published in 2010 (ELN 2010),7 defining 1 favorable-risk (FR) group, 2 intermediate-risk (IR) groups, and 1 adverse-risk (AR) group. During that time period, alloSCT as a PRT was generally recommended if feasible for IR patients with a suitable HLA-matched related donor, and AR patients.7-11 The first update of the ELN 2010 was published in 2017 (ELN 2017), defining 1 FR, IR, and AR group each,6 redistributing a large number of patients in the IR group to the AR group and some to the FR group. Another significant change during that time period was continuously improving outcomes of alloSCT, due to decreasing transplant-related mortality, leading to alloSCT being recommended as PRT if feasible for IR and AR patients, regardless of donor relation.6,8,10,12-14 Further significant changes took place in the field of AML induction therapy, with the introduction of novel agents such as fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) inhibitors,15-18 gemtuzumab-ozogamicin,19,20 and CPX351.21 The most recent ELN update was published in 2022 (ELN 2022),2 in the largest part again shifting patients from FR to IR or IR to AR groups, and a smaller part in the other direction, based on a growing understanding of several genetic risk factors.22

So far, genetically defined cohorts of registries or clinical trials were often used as retrospective real-world validation cohorts for both the ELN 2010 to ELN 2017, and ELN 2017 to ELN 2022 updates.23-34 These validation cohorts all contain an inherent bias of patients not being treated according to treatment recommendations fitting to the time interval of the respective ELN classification. Therefore, these cohorts can, in retrospect, be genetically defined to newly described ELN risk groups; their outcome, however, is defined by outdated treatment algorithms.

In our study, we retrospectively analyzed patients treated at our center between 2010-2016 and 2017-2022, who were classified according to ELN 2010 or ELN 2017, respectively. To eliminate the previously mentioned treatment bias and to ensure comparability of AML genetic risk between patient groups in the 2 treatment intervals (2010-2016 and 2017-2022), we reclassified the 2017 to 2022 patient group according to ELN 2010 and compared their outcome with the actual 2010 to 2016 patient group. This reclassification allowed us to confirm the positive impact of ELN-guided PRT definition on patient outcomes, rather than the impact of genetics in the context of former treatment algorithms. To our knowledge of the current literature, this is the first “as treated” analysis that examines the impact of ELN-guided PRT in the context of the treatment algorithms applied in the respective ELN time period.

Patients and methods

All analyses were performed with the previous approval of our local ethics committee (AZ 2020-742-f-S) and in full compliance with relevant ethical and regulatory guidelines, including the Declaration of Helsinki. We retrospectively reviewed the electronic medical records of all adult patients diagnosed with AML and admitted to the University Hospital Münster between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2022. General treatment recommendations and allocations during this period were based on genetic risk criteria proposed by the ELN recommendations,6,7 although in a minority of cases individualized treatment recommendations were made, taking into account specific risk factors not reflected in the ELN guidelines, and allocation of patients into various clinical trials performed at the center,12,15,16,35,36 reflecting the real-word setting of our data. Treatment recommendations were based on ELN recommendations only in patients who could receive intensive induction chemotherapy. Therefore, only patients aged 18 to 75 years who received ≥1 cycle of intensive AML induction therapy at our center were included for further analysis. Among them, several patients were enrolled in prospective clinical trials (DaunoDouble trial,37 n = 72; ETAL-1 trial,36 n = 27; ASAP trial,38 n = 47). Patients were retrospectively assigned to a treatment cohort according to either ELN 2010 (1 January 2010 to 31 December 2016: 2010-2016) or ELN 2017 (1 January 2017 to 31 December 2022: 2017-2022). The 2 IR groups in ELN 2010 were fused for the purpose of this comparison, as previously described.39,40 In a further theoretical step of analysis, we reclassified the risk (Rre) of the 2017-2022 patient group according to ELN 2010 and compared their outcome with the actual 2010-2016 patient cohort in identical risk groups (R vs Rre comparison).

Response after induction therapy was assessed after 1 or 2 courses of induction therapy according to previously published criteria.6 Briefly, patients achieving either a complete remission (CR) or a CR with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRi) before proceeding to PRT were considered to have achieved a first CR (CR1). Refractory disease, morphologic leukemia-free survival, or early death before PRT were considered as induction failures.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics of both patient groups were compared using either the χ2 test for categorical variables or the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of initial diagnosis, with patients alive censored at the date of last follow-up. Relapse-free survival (RFS) was calculated from the date of first remission, and RFS events included relapse or death from any cause. Correspondingly, OSallo and RFSallo were calculated from the day of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell infusion. Time-to-event variables were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using Cox proportional hazards survival regression.

Cumulative incidences of relapse (CIR) and nonrelapse mortality (NRM) were estimated according to Aalen-Johansen and compared using Gray method.41 The occurrence of hematologic relapse after either first hematologic remission (CR1) or, by definition, after performed alloSCT (CIRallo) excluded the occurrence of NRM. The terms NRM and NRM after performed alloSCT (NRMallo), when used as percentage, refer to the proportion of deaths observed per patient sample without evidence of prior hematologic relapse. Cox proportional hazards were used for multivariable adjustment of time-to-event variables for age at diagnosis, AML genetic risk according to ELN 2010 criteria, and treatment intervals. For competing risk end points, multivariable models were calculated according to Fine and Gray42 to adjust for potential confounders. Missing values were not imputed. The heterogeneity of the effects of treatment intervals on clinical outcomes was assessed by test for interaction.

Statistical analysis and visualization were performed using RStudio, version 2024.04.2+764. Two-sided P values <.05 were considered as indicating statistically significant differences for all analyses.

Results

Baseline characteristics, ELN risk group classification, and resulting treatment intention at initial diagnosis between time periods 2010-2016 and 2017-2022

A total of 843 patients were admitted to the University Hospital Münster with the initial diagnosis of AML, of whom 161 (19%) were not eligible for intensive induction therapy, 1 (0.1%) refused therapy, and 19 (2%) died before treatment could be initiated (supplemental Figure 1). The remaining 662 patients (79%) received intensive induction therapy and were included in the final analysis set. According to the time interval of diagnosis and treatment decision, 373 patients (56%) were classified according to ELN 2010 and treated between 2010 and 2016, with 60 patients (16% of ELN 2010) categorized as FR, 224 (60%) as IR, and 89 (24%) as AR. The remaining 289 patients (44%) were classified according to ELN 2017 and treated between 2017 and 2022, with 87 patients (30% of ELN 2017) classified as FR, 78 (27%) as IR, and 124 (43%) as AR.

Patients’ baseline characteristics were evenly distributed between 2010-2016 and 2017-2022, except that in the latter cohort there were more patients with therapy-related AML (tAML; Table 1; supplemental Table1; P < .001) and nucleophosmin-1 (NPM1)-mutated AML (Table 1; P = .0171), and more patients were classified as IR (Table 1; P < .001). The median age was 60 years (range, 18-75) years.

Baseline characteristics of the overall treatment cohort, stratified by treatment intervals

| Variables . | All patients . | 2010-2016 . | 2017-2022 . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (% of all patients) | 662 (100) | 373 (56) | 289 (44) | |

| Age, median (range), y | 60 (18-75) | 60 (18-75) | 61 (19-75) | .35∗ |

| Sex, n (%) | .24† | |||

| Female | 285 (43) | 168 (45) | 117 (40) | |

| Male | 377 (57) | 205 (55) | 172 (60) | |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | .71† | |||

| 0-1 | 414 (64) | 231 (63) | 183 (63) | |

| ≥2 | 248 (37) | 142 (38) | 106 (37) | |

| AML type, n (%) | .02† | |||

| De novo | 442 (67) | 259 (69) | 183 (63) | |

| sAML | 142 (21) | 81 (22) | 61 (21) | |

| tAML | 59 (9) | 23 (6) | 36 (12) | |

| Other‡ | 19 (3) | 10 (3) | 9 (3) | |

| ELN risk,§n (%) | ELN 2010 | ELN 2017 | <.001† | |

| FR | 147 (22) | 60 (16) | 87 (30) | |

| IR|| | 302 (46) | 224 (60) | 78 (27) | |

| AR | 213 (32) | 89 (24) | 124 (43) | |

| ELN risk analog 2010, n (%) | Reclassified | Original | Reclassified | .11† |

| FR | 125 (19) | 60 (16) | 65 (22) | |

| IR|| | 382 (58) | 224 (60) | 158 (55) | |

| AR | 155 (23) | 89 (24) | 66 (23) | |

| N¶ = 635 | N¶= 358 | N¶= 277 | ||

| Adverse cytogenetic risk, n (%) | 157 (25) | 92 (26) | 65 (23) | .54† |

| −5 or del(5q) | 50 (8) | 31 (9) | 19 (7) | |

| −7 | 46 (7) | 23 (6) | 23 (8) | |

| Abnl(17p) | 20 (3) | 10 (3) | 10 (4) | |

| Complex karyotype | 95 (15) | 52 (15) | 43 (16) | |

| N¶ = 655 | N¶ = 370 | N¶ = 285 | ||

| NPM1 mutation, n (%) | .0171† | |||

| Yes | 163 (25) | 79 (21) | 84 (29) | |

| No | 492 (75) | 291 (79) | 201 (71) | |

| FLT3-ITD, n (%) | .62† | |||

| Yes | 123 (19) | 67 (18) | 56 (20) | |

| No | 532 (81) | 303 (82) | 229 (80) |

| Variables . | All patients . | 2010-2016 . | 2017-2022 . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (% of all patients) | 662 (100) | 373 (56) | 289 (44) | |

| Age, median (range), y | 60 (18-75) | 60 (18-75) | 61 (19-75) | .35∗ |

| Sex, n (%) | .24† | |||

| Female | 285 (43) | 168 (45) | 117 (40) | |

| Male | 377 (57) | 205 (55) | 172 (60) | |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | .71† | |||

| 0-1 | 414 (64) | 231 (63) | 183 (63) | |

| ≥2 | 248 (37) | 142 (38) | 106 (37) | |

| AML type, n (%) | .02† | |||

| De novo | 442 (67) | 259 (69) | 183 (63) | |

| sAML | 142 (21) | 81 (22) | 61 (21) | |

| tAML | 59 (9) | 23 (6) | 36 (12) | |

| Other‡ | 19 (3) | 10 (3) | 9 (3) | |

| ELN risk,§n (%) | ELN 2010 | ELN 2017 | <.001† | |

| FR | 147 (22) | 60 (16) | 87 (30) | |

| IR|| | 302 (46) | 224 (60) | 78 (27) | |

| AR | 213 (32) | 89 (24) | 124 (43) | |

| ELN risk analog 2010, n (%) | Reclassified | Original | Reclassified | .11† |

| FR | 125 (19) | 60 (16) | 65 (22) | |

| IR|| | 382 (58) | 224 (60) | 158 (55) | |

| AR | 155 (23) | 89 (24) | 66 (23) | |

| N¶ = 635 | N¶= 358 | N¶= 277 | ||

| Adverse cytogenetic risk, n (%) | 157 (25) | 92 (26) | 65 (23) | .54† |

| −5 or del(5q) | 50 (8) | 31 (9) | 19 (7) | |

| −7 | 46 (7) | 23 (6) | 23 (8) | |

| Abnl(17p) | 20 (3) | 10 (3) | 10 (4) | |

| Complex karyotype | 95 (15) | 52 (15) | 43 (16) | |

| N¶ = 655 | N¶ = 370 | N¶ = 285 | ||

| NPM1 mutation, n (%) | .0171† | |||

| Yes | 163 (25) | 79 (21) | 84 (29) | |

| No | 492 (75) | 291 (79) | 201 (71) | |

| FLT3-ITD, n (%) | .62† | |||

| Yes | 123 (19) | 67 (18) | 56 (20) | |

| No | 532 (81) | 303 (82) | 229 (80) |

Abnl, abnormalities; del, deletion; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; FLT3-ITD, internal tandem duplication of the FLT3 gene; PS, performance status; sAML, secondary AML; tAML, therapy-related AML.

Mann-Whitney U test.

χ2 test.

Subgroup not included in statistical comparison.

According to ELN of either 2010 or 2017 definitions.

ELN 2010 Intermediate-I and Intermediate-II subgroups were combined.

Number of evaluable patients.

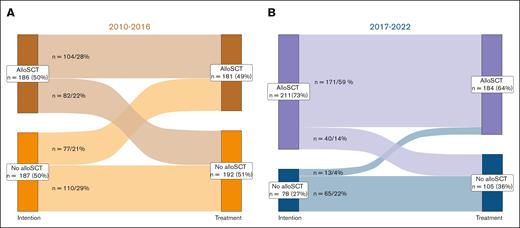

Following the treatment recommendations for 373 patients classified according to ELN 2010 between 2010 and 2016, 186 (50%) were intended for and 104 (28%) received an alloSCT as PRT, whereas 187 (50%) were intended for conventional consolidation, with 77 (21%) receiving an alloSCT as subsequent therapy (Figure 1A; Table 2). The main reasons for 82 patients (22%) not reaching alloSCT as intended were severe infection or comorbidities (n = 38), early death (n = 29), no suitable donor found (n = 1), or other reasons (ie, patient decision or lost to follow-up; n = 14). A total of 55 patients (15%) were not intended for alloSCT due to missing related donors. Of 289 patients in the ELN 2017 period, 211 (73%) were planned for, and 171 (59%) received, an alloSCT, whereas 78 (27%) were intended for consolidation, of whom 13 (5%) received transplant (Figure 1B; Table 2). The main reasons for 40 patients (14%) not reaching alloSCT as intended were early death (n = 23), severe infection or comorbidity (n = 6), no suitable donor found (n = 1), or other reasons (n = 10). In summary, significantly more patients were intended for alloSCT as PRT after 2016 (Table 2; P < .001).

Treatment intention vs treatment received after induction therapy. (A-B) Sankey diagram for the intention of PRT at first diagnosis and the treatment patients eventually received after induction therapy. For patients treated between (A) 2010 and 2016 ELN 2010 classification (225 patients with CR/CRi) and (B) 2017 and 2022 ELN 2017 classification (198 patients with CR/CRi) were applied to determine PRT.

Treatment intention vs treatment received after induction therapy. (A-B) Sankey diagram for the intention of PRT at first diagnosis and the treatment patients eventually received after induction therapy. For patients treated between (A) 2010 and 2016 ELN 2010 classification (225 patients with CR/CRi) and (B) 2017 and 2022 ELN 2017 classification (198 patients with CR/CRi) were applied to determine PRT.

Treatment and transplant characteristics

| Variables . | All patients . | 2010-2016 . | 2017-2022 . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (% of all patients) | 662 (100) | 373 (56) | 289 (44) | |

| Induction chemotherapy, n (%) | ||||

| 1 cycle | 662 (100) | 373 (100) | 289 (100) | |

| 2 cycles | 309 (47) | 226 (61) | 83 (29) | <.001∗ |

| Anthracycline-based | 561 (85) | 350 (94) | 211 (73) | <.001∗ |

| + TKI | 34 (5) | 0 (0) | 34 (12) | |

| + GO | 29 (4) | 0 (0) | 29 (10) | |

| CPX351 | 64 (10) | 0 (0) | 64 (22) | |

| Other | 37 (6) | 23 (6) | 14 (5) | |

| Induction response, n (%) | .03∗ | |||

| CR/CRi | 423 (64) | 225 (60) | 198 (69) | |

| Induction failure | 239 (36) | 148 (40) | 91 (31) | |

| Consolidation chemotherapy, n (%) | .002† | |||

| Yes | 254 (38) | 163 (44) | 91 (31) | |

| No | 405 (61) | 208 (56) | 197 (68) | |

| Lost to follow-up‡ | 3 (<1) | 2 (1) | 1 (<1) | |

| Indication for alloSCT in CR1, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 397 (60) | 186 (50) | 211 (73) | <.001† |

| AlloSCT as intended | 275 (42) | 104 (28) | 171 (59) | |

| No donor identified | 3 (<1) | 2 (1) | 1 (<1) | |

| No alloSCT after induction | 122 (18) | 82 (22) | 40 (14) | |

| No | 265 (40) | 187 (50) | 78 (27) | |

| AlloSCT, n (%) | ||||

| Total | 435 (66) | 219 (59) | 216 (75) | <.001† |

| After induction | 365 (55) | 181 (49) | 184 (64) | .001† |

| Remission status before alloSCT, n (%) | .001† | |||

| CR/CRi | 234 (35) | 101 (27) | 133 (46) | |

| After induction (CR1) | 211 (32) | 90 (24) | 121 (42) | |

| Active disease | 201 (30) | 118 (32) | 83 (29) | |

| Primary refractory | 124 (19) | 67 (18) | 57 (20) | |

| Relapse | 77 (12) | 51 (14) | 26 (9) | |

| HCT-CI score,§n (%) | .024† | |||

| 0-2 | 466 (70) | 276 (74) | 190 (66) | |

| ≥3 | 188 (28) | 91 (24) | 95 (33) | |

| Unknown/not determinable‡ | 8 (1) | 4 (1) | 4 (1) | |

| Conditioning, n (%) | <.001|| | |||

| RIC | 223 (34) | 87 (23) | 136 (47) | |

| SEQ | 202 (31) | 125 (34) | 77 (27) | |

| MAC | 10 (2) | 7 (2) | 3 (1) | |

| Donor, n (%) | .99|| | |||

| MRD | 108 (16) | 57 (15) | 51 (18) | |

| MMRD | 18 (3) | 9 (2) | 9 (3) | |

| Haploidentical | 17 (3) | 8 (2) | 9 (3) | |

| MUD | 248 (37) | 122 (33) | 126 (44) | |

| MMUD | 61 (9) | 31 (8) | 30 (10) |

| Variables . | All patients . | 2010-2016 . | 2017-2022 . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (% of all patients) | 662 (100) | 373 (56) | 289 (44) | |

| Induction chemotherapy, n (%) | ||||

| 1 cycle | 662 (100) | 373 (100) | 289 (100) | |

| 2 cycles | 309 (47) | 226 (61) | 83 (29) | <.001∗ |

| Anthracycline-based | 561 (85) | 350 (94) | 211 (73) | <.001∗ |

| + TKI | 34 (5) | 0 (0) | 34 (12) | |

| + GO | 29 (4) | 0 (0) | 29 (10) | |

| CPX351 | 64 (10) | 0 (0) | 64 (22) | |

| Other | 37 (6) | 23 (6) | 14 (5) | |

| Induction response, n (%) | .03∗ | |||

| CR/CRi | 423 (64) | 225 (60) | 198 (69) | |

| Induction failure | 239 (36) | 148 (40) | 91 (31) | |

| Consolidation chemotherapy, n (%) | .002† | |||

| Yes | 254 (38) | 163 (44) | 91 (31) | |

| No | 405 (61) | 208 (56) | 197 (68) | |

| Lost to follow-up‡ | 3 (<1) | 2 (1) | 1 (<1) | |

| Indication for alloSCT in CR1, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 397 (60) | 186 (50) | 211 (73) | <.001† |

| AlloSCT as intended | 275 (42) | 104 (28) | 171 (59) | |

| No donor identified | 3 (<1) | 2 (1) | 1 (<1) | |

| No alloSCT after induction | 122 (18) | 82 (22) | 40 (14) | |

| No | 265 (40) | 187 (50) | 78 (27) | |

| AlloSCT, n (%) | ||||

| Total | 435 (66) | 219 (59) | 216 (75) | <.001† |

| After induction | 365 (55) | 181 (49) | 184 (64) | .001† |

| Remission status before alloSCT, n (%) | .001† | |||

| CR/CRi | 234 (35) | 101 (27) | 133 (46) | |

| After induction (CR1) | 211 (32) | 90 (24) | 121 (42) | |

| Active disease | 201 (30) | 118 (32) | 83 (29) | |

| Primary refractory | 124 (19) | 67 (18) | 57 (20) | |

| Relapse | 77 (12) | 51 (14) | 26 (9) | |

| HCT-CI score,§n (%) | .024† | |||

| 0-2 | 466 (70) | 276 (74) | 190 (66) | |

| ≥3 | 188 (28) | 91 (24) | 95 (33) | |

| Unknown/not determinable‡ | 8 (1) | 4 (1) | 4 (1) | |

| Conditioning, n (%) | <.001|| | |||

| RIC | 223 (34) | 87 (23) | 136 (47) | |

| SEQ | 202 (31) | 125 (34) | 77 (27) | |

| MAC | 10 (2) | 7 (2) | 3 (1) | |

| Donor, n (%) | .99|| | |||

| MRD | 108 (16) | 57 (15) | 51 (18) | |

| MMRD | 18 (3) | 9 (2) | 9 (3) | |

| Haploidentical | 17 (3) | 8 (2) | 9 (3) | |

| MUD | 248 (37) | 122 (33) | 126 (44) | |

| MMUD | 61 (9) | 31 (8) | 30 (10) |

GO, gemtuzumab-ozogamicin; HCT-CI, hematopoietic cell transplant–specific comorbidity index; MAC, myeloablative conditioning; MMRD, HLA-mismatched related donor; MMUD, HLA-mismatched unrelated donor; MRD, HLA-matched related donor; MUD, HLA-matched unrelated donor; SEQ, sequential conditioning; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

χ2 test.

Mann-Whitney U test.

Subgroup not included in statistical comparison.

According to Sorror et al43.

Fisher exact test.

General course of treatment

A total of 423 patients achieved a CR1(CR/CRi) after induction therapy (Table 2), 225 (60% of cohort) in the 2010-2016 cohort, and 198 (69%) in the 2017-2022 cohort, respectively (P = .03). Between 2010 and 2016, 155 patients (71%) received 2 cycles of induction chemotherapy, 163 (44%) proceeded to consolidation chemotherapy, and 181 (49%) received an alloSCT. Between 2017 and 2022, only 83 patients (31%) received 2 cycles of induction (ELN 2010 vs 2017 cohort, P < .001), 91 (31%) proceeded to consolidation (ELN 2010 vs 2017 cohort, P = .002), and 184 (64%) to alloSCT (ELN 2010 vs 2017 cohort, P < .001). Generally, alloSCT as PRT was recommended for patients with ELN 2010 IR (HLA-matched related donor) and AR (HLA-matched related or unrelated donor) AML. With the implementation of the ELN 2017 classification, alloSCT as PRT was recommended for patients with IR and AR irrespective of donor relation.

Comparison of treatment outcomes between time periods 2010-2016 and 2017-2022

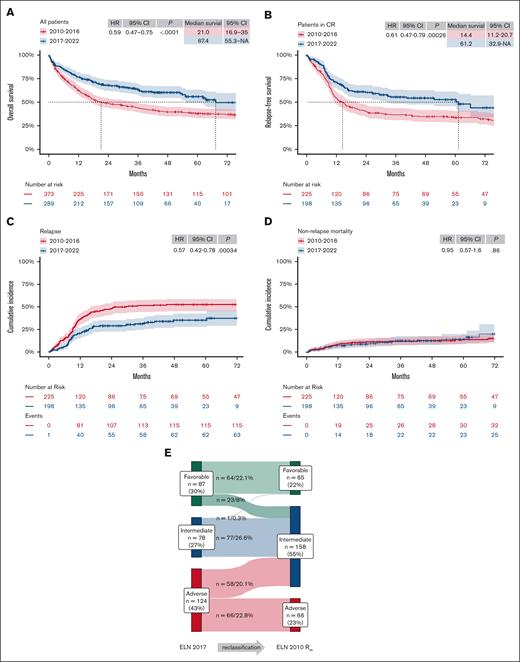

Median follow-up was 61 months (range, 36-89), with 90 months (range, 65-113) for ELN 2010 and 42 months (range, 28-59) for ELN 2017 cohorts, respectively. OS and RFS improved significantly for patients treated between 2017 and 2022 compared with those treated between 2010 and 2016 (Figure 2A-B; 4-year OS, 60% vs 40% [hazard ratio (HR), 0.59; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.47-0.75; P < .0001]; 4-year RFS, 54% vs 35% [HR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.47-0.79; P ≤ .001]). Patients achieving a first remission treated in 2017-2022 had a significantly lower CIR, with similar NRM, than those treated in 2010-2016 (Figure 2C-D; CIR [HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.42-0.78; P < .001] and NRM [HR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.57-1.6; P = .86]).

Patient outcomes significantly improved after 2016. (A-B) Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS (A) and RFS (B) of patients treated either in the time period 2010-2016 or 2017-2022, respectively. Median survival in months and HRs with 95% CIs, and P values of Cox regression, are tabulated in each plot. (C-D) CIR (C) and NRM (D) of patients upon reaching CR1 in the same time periods were estimated according to Aalen-Johansen and compared using Gray's method. (E) Sankey diagram of retrospective reclassification of the 2017-2022 cohort based on genetic risk according to ELN 2010 classification (ELN 2010 Rre). NA, not applicable.

Patient outcomes significantly improved after 2016. (A-B) Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS (A) and RFS (B) of patients treated either in the time period 2010-2016 or 2017-2022, respectively. Median survival in months and HRs with 95% CIs, and P values of Cox regression, are tabulated in each plot. (C-D) CIR (C) and NRM (D) of patients upon reaching CR1 in the same time periods were estimated according to Aalen-Johansen and compared using Gray's method. (E) Sankey diagram of retrospective reclassification of the 2017-2022 cohort based on genetic risk according to ELN 2010 classification (ELN 2010 Rre). NA, not applicable.

A total of 435 patients (66%) received an alloSCT, 219 (59%) between 2010 and 2016, and 216 (75%) between 2017 and 2022 (Table 2; supplemental Table 1; P < .001). When treated after 2016, significantly more patients received alloSCT with CR/CRi, either as CR1 or after relapse (P = .001), more patients with a higher hematopoietic cell transplant–specific comorbidity index (P = .024)43 received transplant, more received reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC; P < .001), and transplant from sex-matched donors (P = .03). Other transplant-related characteristics were balanced between treatment intervals.

Survival outcome of patients in the ELN 2017 cohort receiving an alloSCT either in CR1 (n = 211), with primary refractory disease after at least 1 induction cycle (n = 124), or after relapse (n = 100) was better (supplemental Figure 2A-B; 4-year OSallo, 66% vs 50% [HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.5-0.8; P = .0016]; 4-year RFSallo, 59% vs 45% [HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.5-0.9; P = .0056]), and NRM rates decreased (supplemental Figure 2C; HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.42-0.94; P = .02), whereas CIR was unchanged (supplemental Figure 2D; HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.54-1.14; P = .2).

The association of ELN time intervals with patient outcome was substantiated on multivariable analysis with adjustment for age and AML genetic risk according to ELN 2010 criteria (Table 3). Notably, treatment based on the updated ELN 2017 classification was the only variable that showed a significant association with CIR (Table 4). Conversely, AR genetics were not associated with relapse incidence after adjustment for treatment intervals. Despite a trend toward lower NRM in patients treated from 2017, only higher age was significantly associated with NRM.

Multivariable Cox regression analysis for OS and RFS

| Category . | OS . | RFS . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | |

| Age, per 10 years increase | 1.40 | 1.27-1.54 | <.001 | 1.21 | 1.09-1.35 | <.001 |

| Treatment according | ||||||

| ELN 2010 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| ELN 2017 | 0.56 | 0.45-0.71 | <.001 | 0.59 | 0.45-0.76 | <.001 |

| ELN 2010 genetic risk | ||||||

| Nonadverse | Ref | 1 | Ref | |||

| Adverse | 2.13 | 1.69-2.68 | <.001 | 1.07 | 0.88-1.31 | .50 |

| Category . | OS . | RFS . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | |

| Age, per 10 years increase | 1.40 | 1.27-1.54 | <.001 | 1.21 | 1.09-1.35 | <.001 |

| Treatment according | ||||||

| ELN 2010 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| ELN 2017 | 0.56 | 0.45-0.71 | <.001 | 0.59 | 0.45-0.76 | <.001 |

| ELN 2010 genetic risk | ||||||

| Nonadverse | Ref | 1 | Ref | |||

| Adverse | 2.13 | 1.69-2.68 | <.001 | 1.07 | 0.88-1.31 | .50 |

Ref, reference.

Multivariable Fine and Gray regression models for the CIR and NRM in patients achieving a first remission after induction chemotherapy

| Category . | CIR . | NRM . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | |

| Age, per 10 years increase | 0.98 | 0.82-1.18 | .84 | 1.60 | 1.21-2.11 | <.001 |

| Treatment according | ||||||

| ELN 2010 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| ELN 2017 | 0.54 | 0.35-0.83 | .005 | 0.62 | 0.36-1.08 | .09 |

| ELN 2010 genetic risk | ||||||

| Nonadverse | Ref | 1 | Ref | |||

| Adverse | 0.85 | 0.49-1.50 | .58 | 1.52 | 0.85-2.69 | .16 |

| Category . | CIR . | NRM . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | |

| Age, per 10 years increase | 0.98 | 0.82-1.18 | .84 | 1.60 | 1.21-2.11 | <.001 |

| Treatment according | ||||||

| ELN 2010 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| ELN 2017 | 0.54 | 0.35-0.83 | .005 | 0.62 | 0.36-1.08 | .09 |

| ELN 2010 genetic risk | ||||||

| Nonadverse | Ref | 1 | Ref | |||

| Adverse | 0.85 | 0.49-1.50 | .58 | 1.52 | 0.85-2.69 | .16 |

Reclassification of 2017-2022 group according to ELN 2010 and “as treated” comparison of 2010-2016 vs 2017-2022

To eliminate treatment bias, patients treated between 2017 and 2022 were retrospectively reclassified based on genetic risk according to ELN 2010 (Figure 2E). After reclassification, group sizes of patients in the retrospectively reclassified 2017-2022 cohort (FRre, IRre, and ARre) were comparable to those in the 2010-2016 cohort (Table 1). Most patients were reclassified from FR (23 patients [8%] of cohort) or AR (58 patients [20%]) to IRre, whereas no patient was reclassified to ARre (Figure 2E). One patient with comutation of biallelic CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha (CEBPA) and FLT3-ITD with high allelic ratio was unclassifiable according to ELN 2017, treated as IR, and reclassified from IR to FRre.

Rates of CR1 after induction therapy were similar when comparing time periods for each risk group classified according to ELN 2010 (Table 2), although more patients received alloSCT as PRT in the IRre group (n = 87 [30%]) compared with the IR group treated between 2010 and 2016 (n = 48 [13%]; P = .001), reflecting the shift in PRT choice and donor availability (particularly broader acceptation of unrelated donors for IR patients) based on the ELN 2017 update.

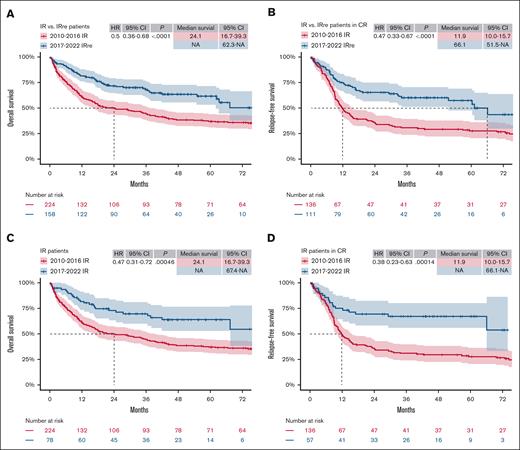

The IRre subgroup of patients treated between 2017 and 2022 showed better OS and RFS when compared with the IR subgroup of the 2010-2016 cohort (Figure 3A-B; OS [HR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.36-0.68; P < .0001] and RFS [HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.33-0.67; P < .0001]). In the regular IR group comparison (Figure 3C-D; OS [HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.31-0.72; P ≤ .001] and RFS [HR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.23-0.63; P ≤ .001]), the improvement in OS and RFS was comparable. In the AR group, however, the OS benefit found in regular comparison (supplemental Figure 3A; OS: HR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.43-0.85; P = .0038) was leveled in the ARre group comparison (supplemental Figure 3C; OS: HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.52-1.15; P = .2). There was no significant difference in RFS in the AR and ARre comparison (supplemental Figure 3B,D), nor in OS or RFS in the FR and FRre comparisons (supplemental Figure 4) between both time intervals.

“As treated” comparison (IR vs IRre comparison) of ELN 2017 and ELN 2010 cohorts. (A-B) Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS (A) and RFS (B) of patients who were retrospectively reclassified as IR (IRre) analog to ELN 2010 classification, treated between 2017 and 2022, compared with regular IR patients, treated between 2010 and 2016 (IR vs IRre). (C-D) Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS (C) and RFS (D) of IR patients regularly classified according to ELN 2010 or ELN 2017, treated between 2010-2016 and 2017-2022, respectively. Median survival in months and HRs with 95% CIs, as well as P values of Cox regression, are tabulated in each plot. NA, not applicable.

“As treated” comparison (IR vs IRre comparison) of ELN 2017 and ELN 2010 cohorts. (A-B) Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS (A) and RFS (B) of patients who were retrospectively reclassified as IR (IRre) analog to ELN 2010 classification, treated between 2017 and 2022, compared with regular IR patients, treated between 2010 and 2016 (IR vs IRre). (C-D) Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS (C) and RFS (D) of IR patients regularly classified according to ELN 2010 or ELN 2017, treated between 2010-2016 and 2017-2022, respectively. Median survival in months and HRs with 95% CIs, as well as P values of Cox regression, are tabulated in each plot. NA, not applicable.

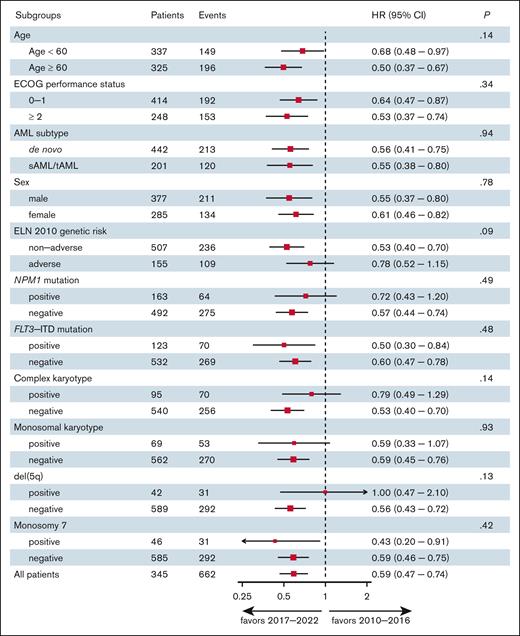

Although improved outcomes were most pronounced in non-AR patients (according to ELN 2010), subgroup analysis displayed no significant heterogeneity of the effect of the treatment intervals on OS as confirmed by test for interaction (Figure 4). However, a trend toward a limited survival benefit was observed in patients with AR genetics (according to ELN 2010 criteria), complex karyotype, and del(5q) over the time intervals. Conversely, a trend toward improved outcome was observed for patients aged >60 years, when treated after 2016 (Figure 4). Consistent with these findings, the improved posttransplant outcomes were primarily driven by patients who received RIC regimens (eg, patients with either CR or CRi), as opposed to those with active disease or high-risk genetics who received sequential conditioning/myeloablative conditioning (test for interaction: HR, 0.54 vs 0.91; P = .036).

Subgroup and interaction analysis. The forest plot shows the heterogeneity of the effect of the treatment interval (2010-2016 vs 2017-2022) on survival outcomes among subgroups. ECOG, ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; sAML, secondary AML; tAML, therapy-related AML.

Subgroup and interaction analysis. The forest plot shows the heterogeneity of the effect of the treatment interval (2010-2016 vs 2017-2022) on survival outcomes among subgroups. ECOG, ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; sAML, secondary AML; tAML, therapy-related AML.

Discussion

Ever more precise genetic definition has greatly contributed to our understanding of the heterogeneity of AML and subsequent implications on treatment outcome as well as treatment intensity, as defined in the ELN classifications.2,6,7 With the updated ELN 2017, more patients were classified as having IR or AR AML, resulting in a broader indication for alloSCT as PRT. Together with increased donor availability and broader acceptation of unrelated donors for IR patients, a significantly larger number of patients underwent transplants.

Large cohorts of patients in clinical registries or prospective multicenter clinical trials have been used for retrospective validation by post hoc genetic analysis with great precision.23-34 Although these cohorts adequately capture the impact of newly defined or redefined genetic risk factors and validate the need for reclassification and adaptation of treatment, they contain an inherent treatment bias, because these patients were treated according to old standards or clinical trial regimens, and therefore neglect the impact of treatment adaptation based on the updated classification.

Our study analyzed patients treated between 2010 and 2016, classified according to ELN 2010, and between 2017 and 2022, classified according to ELN 2017, to compare substantial changes in PRT standards, showing a significant benefit in OS and RFS with reduced CIR and similar NRM for patients treated after 2016. Furthermore, the shift in PRT intensity is reflected in the significantly increased rate of IR patients receiving alloSCT in CR1 between 2017 and 2022. Patients who received transplants after 2016 had better OS and RFS, as well as lower NRM rates, with unchanged CIR.

To eliminate treatment bias, the 2017-2022 cohort was retrospectively reclassified according to ELN 2010, and risk groups were compared between time intervals (R vs Rre group comparison). The IR group benefited significantly in OS and RFS from the updated ELN 2017 classification and subsequent PRT intensification in the IR vs IRre comparison. The shift in PRT intensity is also depicted in the significantly increased rate of patients in the IRre group receiving alloSCT in CR1. However, patients classified as AR according to ELN 2010, including patients with a complex karyotype, did not show a survival benefit in the AR vs ARre comparison, highlighting the unchanged inferior outcome in this high-risk patient collective.

Strikingly, after adjustment for age and ELN time period on multivariable analysis, adverse genetic risk did not show a significant association with relapse risk in CR1 patients. Instead, treatment interval and, thus, PRT, was the key modifier of relapse incidence after CR1. Despite the broader indication for intended alloSCT in patients treated after 2016, there was a significant reduction in NRM after alloSCT. Additionally, both a significant increase of patients receiving RIC after 2016 and a significant benefit of this group compared with more intense conditioning regimes underscores the impact of ELN risk–based choice of PRT.

According to AMLCG study group experience35 and to randomized intergroup comparisons,44 further intensification of conventional induction therapy has not lead to better treatment outcome for patients with intensively treatable AML. On the contrary, PRT by alloSCT when compared with conventional PRT in a prospective matched-pairs analysis was found to significantly improve RFS and showed a trend toward better OS in patients with AML with the IR karyotype as classified at this time.12 Furthermore, a prospectively randomized comparison of alloSCT vs conventional PRT with early salvage alloSCT in case of relapse, performed in IR patients with AML,showed a significantly better 2-year disease-free survival with no clear impact on OS.36 Both results are in line with our retrospective, real-world R vs Rre comparison. We conclude that the 2017 update of the ELN classification on the basis of increasing biological understanding of the disease and subsequent changes in PRT intensity has made a significant contribution to improving the outcomes of patients with AML.

Because PRT intensity was not the only therapeutic advancement during the observed period, a variety of known and unknown confounding factors must be taken into account as limitations of our analysis. Baseline disease characteristics were comparable between populations in both time intervals, except for an increased number of tAML and NPM1 mutations. Increased fractions of patients with tAML might reflect significant improvements in supportive care over time, and a higher proportion of patients with malignant diseases eligible for intensive treatments.45-47 Likewise, in patients who received transplants after 2016, higher hematopoietic cell transplant–specific comorbidity index scores mirror increased eligibility of patients to undergo alloSCT, at least partly driven by RIC regimens, advancements in supportive care and graft-versus-host disease management. Also, the higher proportion of patients with NPM1 mutated AML might also be explained through more patients being eligible for intensive induction regimens and significant improvements in supportive care over time. In summary, however, after multivariable adjustment for ELN genetic risk, the amount of tAML- or NPM1-mutated patients had no significant impact on the relevant outcome differences observed between the time periods.

Furthermore, induction therapy regimens have substantially improved with the introduction of FLT3 inhibitors,15-18,48 gemtuzumab-ozogamicin,19,20,48 and CPX351,21 which is also reflected in our data (Table 2). Also, significantly less patients received a second cycle of induction after 2016, in part due to a substantial number of patients that were enrolled in the DaunoDouble trial between 2014 and 2022, comparing higher-dose daunorubicin and double vs single induction regimens.37 Consistent with the results of the DaunoDouble trial, CR1 rates were comparable between both time periods, rendering a significant effect of variation in induction regimens unlikely. Furthermore, several patients were enrolled in the ETAL-1 trial36 between 2011 and 2018 that assessed alloSCT as PRT in CR1 for IR patients as compared with conventional PRT and early salvage alloSCT in case of relapse. Because most patients from our cohort treated in the ETAL-1 trial belong to the 2010-2016 cohort and therefore were not treated as intended when randomized to the alloSCT in CR1 arm, this most likely only weakened the observed beneficial effect of alloSCT for IR patients reclassified in this analysis. Furthermore, maintenance therapy with sorafenib49-51 may have contributed to a decrease in CIR for FLT3 mutated patients. Additionally, treatment options for relapsed/refractory AML have also improved with increasing use of hypomethylating agents, that is, azacitidine or decitabine,52-54 either alone or in combination with venetoclax.2,55-57 A further relevant factor affecting treatment outcome is minimal residual disease before transplant.58 Because the quality of the data concerning the measuring methods and consistency of measurements of minimal residual disease before alloSCT varies greatly, especially between the 2 time periods, reliable data on this variable could not be analyzed.

Another relevant factor contributing to improved outcomes is the reduction of NRM following alloSCT for patients treated after 2016. Recent improvements in conditioning regimens with increased use of RIC, for example, treosulfan-based conditioning in older patients,59 or implementation of sequential induction regimens for patients with relapsed/refractory AML who underwent transplants with active disease, as performed for patients enrolled in the ASAP trial,38 as well as advances in immunosuppressive agents (eg, the incorporation of posttransplant cyclophosphamide60), in graft-versus-host disease therapy (eg, the JAK2 inhibitor ruxolitinib61-64), and in cytomegalovirus prophylaxis (eg, letermovir65) have an impact on the observed lower NRM rates after alloSCT in the 2017-2022 cohort. The increase of patients reaching intended alloSCT as PRT in CR1 and conditioned with RIC after 2016 might also contribute to reduction of NRM. However, general supportive care standards at our center (eg, antimycotic prophylaxis with posaconazole) were not subject to major changes during the observed time periods. Furthermore, first- and second-line anti-infective treatment standards were not changed during both time periods.

Because our analysis is retrospective, some confounding variables could not be eliminated. Nevertheless, our monocenter study included a large number of patients with a very low variation in treatment standards. Additionally, in contrast to registry-based data, our analysis comprises a primary data set with robust and reliable data quality. Our large patient collective showed rather balanced baseline characteristics and treatment variables, allowing for a robust real-world validation of the impact of PRT choice based on the updated ELN classification. Further, as the question studied in this report will not be answered anymore by prospective randomized comparison, our analysis represents the highest possible evidence level to prove the positive impact of ELN updates on AML outcome.

Although treatment practices have increasingly aligned following the introduction of the ELN criteria and corresponding treatment recommendations in Germany and Europe, differences in standards and practices at transplant centers, as well as their experience and patient numbers, may affect treatment outcomes. At our center, we strictly adhered to the practice standards described in the “Methods.” To address our question of treatment bias and maintain the internal consistency of the data, we intentionally favored the monocenter study.

Based on the analysis of >600 patients with AML treated at our center from 2010 to 2022, we conclude that the updated ELN 2017 classification moving more patients to IR and AR as well as the subsequent intensification of PRT with a higher proportion of patients proceeding to intended alloSCT, significantly helped to improve the survival of patients with AML. Together with recent advances in peritransplant and posttransplant patient management, introduction of novel induction therapy regimens, the increasing availability of targeted therapies, and an ever-improving understanding of the pathophysiology of AML, regular updates of disease classifications and treatment recommendations therefore play a crucial role in improving the survival of patients with AML.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all involved data managers and caregivers. Most importantly, the authors owe their gratitude to the patients who contributed their data.

A.F.B. was supported by a research grant from the Innovative Medical Research Fund (IMF; BE122204) of the University of Münster Faculty of Medicine and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; German Research Foundation, 493624047 [Clinician Scientist CareerS Münster]). J.R. was supported by a research grant from IMF (RO212301) of the University of Münster Faculty of Medicine and the Circle of Friends of the Bone Marrow Transplantation Center in Münster. D.V.W. is supported by the DFG (German Research Foundation, 511811315 [Walter Benjamin fellowship]). T.J.B. was supported by a grant from the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF; German Federal Ministry for Education and Research; Netzwerk Universitätsmedizin, NUM-DIZ 01KX2121).

Authorship

Contribution: A.F.B., C.S., W.E.B., and M.S. conceptualized the study; A.F.B., J.R., D.V.W., L.J.K., P.B., T.J.B., and A.W. collected data; A.F.B., J.R., and L.A. were responsible for methodology and software; K.W., T.K., A.K., R.M.M., C.R., and J.-H.M. were responsible for validation; A.F.B., J.R., C.S., W.E.B., and M.S. were responsible for investigation; A.F.B. and J.R. curated data and wrote the original draft of the manuscript; C.S., W.E.B., M.S., and G.L. reviewed and edited the manuscript; and all authors read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.F.B. reports speaker honoraria from AbbVie and Aurikamed; and travel grant from AbbVie. J.R. declares speaker honoraria from Aurikamed; and travel grant from AbbVie. D.V.W. reports conference support/travel grant from Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Servier, Celgene, Amgen, Gilead, and Daiichi Sankyo. A.K. declares speaker honoraria from Roche, AbbVie, Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD), Takeda, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), and Amgen; and travel grant from BMS, Sobi, AbbVie, European Union Studies Association (EUSA), and BeiGene. T.K. declares travel grant and advisory board from Daiichi-Sankyo. J.-H.M. declares advisory board participation from Pfizer, Daiichi Sankyo, Laboratoires Delbert, and Otsuka; lecture fees from BMS, Pfizer, Celgene, Novartis, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, and BeiGene; and congress support from Alexion, Astellas, Pfizer, Celgene, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, and Novartis. W.E.B. declares other business ownership, grant/contract, patent, other intellectual property from Anturec Pharmaceuticals; other business ownership and patent from Elvesca Biotherapeutics; and stock, grant/contract, and travel support from Philogen S.p.A. G.L. received research grants (not related to this study) from Agios, Aquinox, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Celgene, Gilead, Janssen, MorphoSys, Novartis, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, and Verastem; and received honoraria from ADC Therapeutics, AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, BeiGene, BMS, Celgene, Constellation, Genase, Genmab, Gilead, Hexal/Sandoz, Immagene, Incyte, Janssen, Karyopharm, Lilly, Miltenyi, MorphoSys, MSD, NanoString, Novartis, PentixaPharm, Pierre Fabre, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, and Sobi. C.S. declares travel support from Jazz Pharmaceuticals, AbbVie, BMS, and Pfizer; other support from AbbVie, BMS, Pfizer, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Laboratories Delbert, Novartis, Roche, Servier, and Jazz Pharmaceuticals; and honoraria/advisory board participation from AbbVie, BMS, Pfizer, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Laboratories Delbert, Novartis, Roche, Servier, and Jazz Pharmaceuticals; and grants/contracts from Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Angio Biomed, and from Anturec Pharmaceuticals. M.S. has served as a consultant for Pfizer, MSD, BMS, Incyte, Takeda, Astellas, and Amgen; has served as a speaker for Pfizer, Medac, MSD, Astellas, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Amgen, Novartis, Gilead, Celgene, BMS, AbbVie, and Incyte; has received research funding from Pfizer; and has received travel support from Medac and Pfizer. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Matthias Stelljes, Department of Medicine A, Hematology/Oncology, University Hospital Münster, Albert-Schweitzer Campus 1, 48149 Münster, Germany; email: matthias.stelljes@ukmuenster.de; and Andrew F. Berdel, Department of Medicine A, Hematology/Oncology, University Hospital Münster, Albert-Schweitzer Campus 1, 48149 Münster, Germany; email: andrew.berdel@ukmuenster.de.

References

Author notes

A.F.B. and J.R. contributed equally to this study.

Partially presented at the annual meeting of the German, Austrian, and Swiss Associations of Hematology and Medical Oncology, Basel Switzerland, 13 October 2024.

Presented in abstract form at the 66th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Diego, CA, 7 to 10 December 2024.

The data sets generated and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding authors, Andrew F. Berdel (andrew.berdel@ukmuenster.de) and Matthias Stelljes (matthias.stelljes@ukmuenster.de), upon reasonable request.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.