Key Points

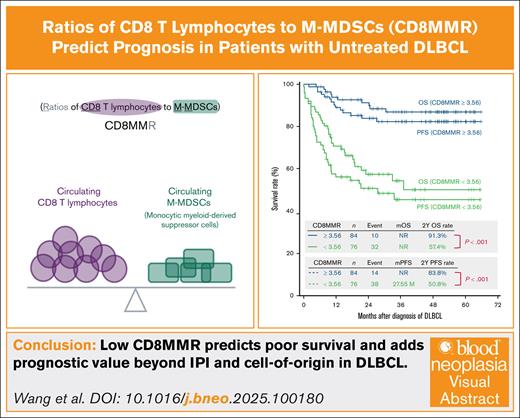

CD8MMR integrates pretreatment tumor immunity into risk stratification for patients with DLBCL.

Low CD8MMR is linked to poor survival and adds prognostic value beyond IPI and cell of origin in DLBCL.

Visual Abstract

CD8 and CD4 T lymphocytes play critical roles in antitumor immunity and are central to immune-based therapies for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Conversely, monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells (M-MDSCs) promote immunosuppression and tumor progression. This study investigates the prognostic value of the ratios of CD8 and CD4 T lymphocytes to M-MDSCs, referred to as CD8MMR and CD4MMR, in patients with untreated DLBCL. In a prospective observational study, 160 patients newly diagnosed with DLBCL were enrolled and randomized into training (n = 120) and validation (n = 40) cohorts. Circulating immune cells were assessed from fresh peripheral blood using flow cytometry, and cutoff values for CD8MMR and CD4MMR were determined by receiver operating characteristic curve and area under the curve analysis. Patients with high-risk International Prognostic Index (IPI), double-expressor lymphoma, or Epstein-Barr virus–positive DLBCL had significantly lower CD8MMR and CD4MMR. Low CD8MMR (<3.56) or CD4MMR (<3.79) was significantly associated with inferior progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). When combining both ratios, patients with high levels of CD8MMR and CD4MMR had the most favorable survival, whereas those with low levels of both had the poorest outcomes; discordant levels corresponded to intermediate survival. Multivariate analysis revealed CD8MMR as an independent predictor of PFS and OS, with greater predictive strength than CD4MMR. Furthermore, CD8MMR stratified survival outcomes across different IPI risk categories and cell-of-origin subtypes, consistently identifying patients with poor prognosis. These findings suggest that CD8MMR is a novel and independent prognostic biomarker in DLBCL, offering additional value for risk stratification in clinical practice.

Introduction

The application of cell therapies and immunotherapies, including chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy (CAR T; such as axicabtagene ciloleucel, tisagenlecleucel, and lisocabtagene maraleucel)1-5 and CD3×CD20 bispecific T-cell engagers (such as glofitamab, mosunetuzumab, epcoritamab, and odronextamab),6-9 has recently marked a significant milestone in treating patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). CAR T-cell therapies and bispecific T-cell engagers function by targeting the patient’s CD3+ T cells, including CD4 T lymphocytes and CD8 T lymphocytes. Notably, lower levels of circulating CD4 or CD8 T lymphocytes have been associated with poorer prognoses in patients with DLBCL.10-15

Monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells (M-MDSCs) are well known for their immunosuppressive role in the tumor microenvironment.16,17 A pivotal study revealed that M-MDSCs could impair the efficacy of CAR T cells in patients with relapsed DLBCL.18 Furthermore, prior research, including our own findings, has shown that higher levels of circulating M-MDSCs correlate with poorer progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients with untreated DLBCL.19,20

The lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR) is a known prognostic marker in DLBCL, with a higher LMR indicating a better prognosis and a lower LMR suggesting a poorer outcome.21-24 Given the prognostic significance of circulating CD4 T lymphocytes, CD8 T lymphocytes, and M-MDSCs in patients with DLBCL, this study aims to explore whether lymphocytes can be further specified by CD4 or CD8 T lymphocytes, and whether M-MDSCs can specify monocytes. We propose establishing new ratios of CD4 or CD8 T lymphocytes to M-MDSCs (CD4MMR or CD8MMR), hypothesizing that these could offer more precise prognostic predictions for patients with DLBCL before treatment, potentially outperforming the predictive value of LMR.

Material and methods

Study on human patients

This prospective observational study was conducted at a tertiary medical center in Taiwan. From 15 May 2019 to 30 November 2023, adult individuals with untreated DLBCL were eligible for enrollment in the Division of Hematology and Oncology at Taipei Veterans General Hospital. The enrolled patients with DLBCL were randomized into the training or validation cohorts at a 3:1 ratio.

Exclusion criteria included patients with DLBCL originating from the central nervous system (primary central nervous system lymphoma) or mediastinum, as these patients received distinct initial treatments compared with those with other DLBCL origins. Additionally, individuals with HIV infection, other active infections, or concurrent malignancies receiving treatment within 2 years were excluded.

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Taipei Veterans General Hospital (numbers 2019-04-015CC and 2020-07-024BCF), and all participating patients provided written informed consent for the scientific use of their blood. Consent for publication was obtained from the patients.

Clinical definition to subclassify patients with DLBCL

The International Prognostic Index (IPI) uses 5 distinct risk factors for assessment25: (1) age >60 years, (2) performance status >1, (3) elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase levels, (4) >1 extranodal disease site, and (5) Ann Arbor stage III or IV. Based on these factors, patients were categorized into 3 risk groups: low (0-1 factor), intermediate (2-3 factors), and high risk (4-5 factors).

To differentiate between cells of origin (COO) for germinal center B-cell (GCB) and non-GCB subtypes, the Hans algorithm was applied, using immunohistochemistry (IHC) to stain for CD10, BCL6, and MUM1.26 Double-expressor lymphoma (DEL) was defined by ≥40% of tumor cells expressing MYC protein and ≥50% expressing BCL2 protein, as determined through IHC.27 Double-hit lymphoma (DHL) is defined by concurrent MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 rearrangements detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization.28

The diagnosis of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–positive DLBCL, not otherwise specified (EBV+ DLBCL, NOS), followed the 2016 World Health Organization revised classification.29 Detection of EBV-encoded RNA using in situ hybridization was the standard test, with EBV-encoded RNA positivity defined as >80% of neoplastic cells.

Detection of M-MDSCs through flow cytometry

Circulating human M-MDSCs (defined as CD45+ CD15− CD14+ CD11b+ CD33+ HLA-DRlow/− cells) were collected from freshly isolated peripheral blood white cells, as previously described.19 Identification was performed using fluorescent-labeled monoclonal antibodies (supplemental Table S1): mouse anti-human CD45, CD15, CD14, CD33, and HLA-DR, and rat anti-human CD11b. Exclusion of dead cells was done using propidium iodide staining (Sigma-Aldrich). Analysis was conducted using a FACSFortessa (BD Biosciences) instrument and FlowJo software.

Quantification of CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells

Peripheral blood white cells were stained with Beckman Coulter CYTO-STAT tetraCHROME monoclonal antibodies (supplemental Table S2) for flow cytometric counting of CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells among all participants. This was performed using a Navios Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter) and analyzed with Navios Tetra software. Absolute values of CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells were calculated by multiplying the patient’s absolute lymphocyte count by the percentage of each T-cell subset identified by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

The study employed Mann-Whitney U tests for quantitative comparisons, Fisher exact tests for categorical data, and Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests for survival analysis, with follow-up until death or 1 October 2024. Survival end points were defined as death from any cause for OS and either disease progression or death for PFS. The study determined the optimal cutoff values for LMR, CD4MMR, and CD8MMR using the receiver operating characteristic curve and area under the curve (AUC) analysis. The cutoff for age was set at the median value. Cox regression models were used to calculate hazard ratios, considering variables that met the proportional hazard assumption and had a P value of <.20 in univariate analyses for multivariate modeling; hazard ratios were reported with corresponding P values and 95% confidence intervals. To compare the prognostic predictions of LMR, CD4MMR, and CD8MMR in patients with DLBCL before initiating treatment, the study used both the Akaike information criterion (AIC)30 and Bayesian information criterion (BIC)31; a difference of ≥2 indicated a significant preference for the model with the lowest AIC or BIC value. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 22.0, with a 2-tailed P value <.05 considered significant.

Results

Enrolled patients

This prospective observational study was conducted at Taipei Veterans General Hospital. A total of 160 untreated adult patients with DLBCL were enrolled (supplemental Figure S1). The patients were randomly assigned to either the training cohort (120 patients) or the validation cohort (40 patients) in a 3:1 ratio. Among these 160 patients (Table 1), the median age was 69 years, 61.3% were male, 40.6% were in Ann Arbor stage IV, and 34.4% had a high-risk IPI score. Additionally, 72.5% of the COO was identified as the non-GCB subtype according to the Hans algorithm using IHC staining, 41.9% had DEL, 7.5% were EBV+ DLBCL, and 4.4% had transformed from indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The median value of LMR was 2.17, whereas the median values of CD4MMR and CD8MMR were 4.88 and 3.71, respectively.

Characteristics of 160 patients with DLBCL before treatment initiation

| Patient characteristics . | No. of patients (%) or median value (interquartile range) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Training cohort (n = 120) . | Validation cohort (n = 40) . | ITT (N = 160) . | |

| Age, y | 69 (57-78) | 69 (59-76) | 69 (58-78) |

| ≥70 | 57 (47.5) | 20 (50.0) | 77 (48.1) |

| Sex, male | 75 (62.5) | 23 (57.5) | 98 (61.3) |

| Hepatitis B carrier∗ | 12 (10.0) | 7 (17.5) | 19 (11.9) |

| Ann Arbor stage | |||

| I | 23 (19.2) | 6 (15.0) | 29 (18.1) |

| II | 26 (21.7) | 8 (20.0) | 34 (21.3) |

| III | 24 (20.0) | 8 (20.0) | 32 (20.0) |

| IV | 47 (39.2) | 18 (45.0) | 65 (40.6) |

| IPI | |||

| Low risk | 27 (22.5) | 12 (30.0) | 39 (24.4) |

| Intermediate risk | 51 (42.5) | 15 (37.5) | 66 (41.3) |

| High risk | 42 (35.0) | 13 (32.5) | 55 (34.4) |

| BM involvement | 31 (25.8) | 11 (27.5) | 42 (26.3) |

| Complex karyotype | 12 (10.0) | 5 (12.5) | 17 (10.6) |

| Bulky mass >7.5 cm | 47 (39.2) | 15 (37.5) | 62 (38.8) |

| COO by IHC stain† | |||

| GCB type‡ | 31 (25.8) | 13 (32.5) | 44 (27.5) |

| Non-GCB type | 89 (74.2) | 27 (67.5) | 116 (72.5) |

| DEL§ | 49 (40.8) | 18 (45.0) | 67 (41.9) |

| EBV+ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma‖ | 9 (7.5) | 3 (7.5) | 12 (7.5) |

| Transformation from previous indolent lymphoma¶ | 5 (4.2) | 2 (5.0) | 7 (4.4) |

| Percentages among peripheral blood white cells | |||

| Lymphocytes (%) | 18.2 (13.0-27.5) | 22.5 (9.2-29.1) | 19.0 (12.7-27.7) |

| Monocytes (%) | 7.7 (6.3-11.0) | 8.3 (6.0-14.8) | 7.8 (6.2-11.9) |

| LMR | 2.23 (1.34-3.99) | 2.05 (1.04-3.35) | 2.17 (1.29-3.65) |

| T lymphocytes in peripheral blood | |||

| CD4 T lymphocytes (absolute count, ×109/L) | 4.54 (2.50-7.28) | 4.88 (2.92-6.26) | 4.66 (2.61-7.14) |

| CD8 T lymphocytes (absolute count, ×109/L) | 3.72 (2.23-5.15) | 4.17 (2.67-5.13) | 3.83 (2.31-5.15) |

| M-MDSCs in peripheral blood (absolute count, ×109/L) | .88 (.39-1.76) | .90 (.43-1.49) | .88 (.40-1.65) |

| Ratio of circulating CD4 T lymphocytes to M-MDSCs (CD4MMR) | 4.82 (2.17-14.11) | 5.30 (2.20-11.96) | 4.88 (2.17-13.14) |

| Ratio of circulating CD8 T lymphocytes to M-MDSCs (CD8MMR) | 3.71 (1.74-10.35) | 3.72 (2.13-13.70) | 3.71 (1.82-10.35) |

| Patient characteristics . | No. of patients (%) or median value (interquartile range) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Training cohort (n = 120) . | Validation cohort (n = 40) . | ITT (N = 160) . | |

| Age, y | 69 (57-78) | 69 (59-76) | 69 (58-78) |

| ≥70 | 57 (47.5) | 20 (50.0) | 77 (48.1) |

| Sex, male | 75 (62.5) | 23 (57.5) | 98 (61.3) |

| Hepatitis B carrier∗ | 12 (10.0) | 7 (17.5) | 19 (11.9) |

| Ann Arbor stage | |||

| I | 23 (19.2) | 6 (15.0) | 29 (18.1) |

| II | 26 (21.7) | 8 (20.0) | 34 (21.3) |

| III | 24 (20.0) | 8 (20.0) | 32 (20.0) |

| IV | 47 (39.2) | 18 (45.0) | 65 (40.6) |

| IPI | |||

| Low risk | 27 (22.5) | 12 (30.0) | 39 (24.4) |

| Intermediate risk | 51 (42.5) | 15 (37.5) | 66 (41.3) |

| High risk | 42 (35.0) | 13 (32.5) | 55 (34.4) |

| BM involvement | 31 (25.8) | 11 (27.5) | 42 (26.3) |

| Complex karyotype | 12 (10.0) | 5 (12.5) | 17 (10.6) |

| Bulky mass >7.5 cm | 47 (39.2) | 15 (37.5) | 62 (38.8) |

| COO by IHC stain† | |||

| GCB type‡ | 31 (25.8) | 13 (32.5) | 44 (27.5) |

| Non-GCB type | 89 (74.2) | 27 (67.5) | 116 (72.5) |

| DEL§ | 49 (40.8) | 18 (45.0) | 67 (41.9) |

| EBV+ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma‖ | 9 (7.5) | 3 (7.5) | 12 (7.5) |

| Transformation from previous indolent lymphoma¶ | 5 (4.2) | 2 (5.0) | 7 (4.4) |

| Percentages among peripheral blood white cells | |||

| Lymphocytes (%) | 18.2 (13.0-27.5) | 22.5 (9.2-29.1) | 19.0 (12.7-27.7) |

| Monocytes (%) | 7.7 (6.3-11.0) | 8.3 (6.0-14.8) | 7.8 (6.2-11.9) |

| LMR | 2.23 (1.34-3.99) | 2.05 (1.04-3.35) | 2.17 (1.29-3.65) |

| T lymphocytes in peripheral blood | |||

| CD4 T lymphocytes (absolute count, ×109/L) | 4.54 (2.50-7.28) | 4.88 (2.92-6.26) | 4.66 (2.61-7.14) |

| CD8 T lymphocytes (absolute count, ×109/L) | 3.72 (2.23-5.15) | 4.17 (2.67-5.13) | 3.83 (2.31-5.15) |

| M-MDSCs in peripheral blood (absolute count, ×109/L) | .88 (.39-1.76) | .90 (.43-1.49) | .88 (.40-1.65) |

| Ratio of circulating CD4 T lymphocytes to M-MDSCs (CD4MMR) | 4.82 (2.17-14.11) | 5.30 (2.20-11.96) | 4.88 (2.17-13.14) |

| Ratio of circulating CD8 T lymphocytes to M-MDSCs (CD8MMR) | 3.71 (1.74-10.35) | 3.72 (2.13-13.70) | 3.71 (1.82-10.35) |

EBER, EBV-encoded RNA.

Defined as positive hepatitis B surface antigen.

Defined according to the Hans algorithm.

Examined all 44 patients with GCB-type DLBCL for MYC, BCL2, and BCL6 rearrangements by fluorescence in situ hybridization to identify DHL. In the training cohort, 5 patients were diagnosed with BCL6-DHL and 4 with BCL2-DHL, whereas 1 patient was deemed indeterminate due to severely crushed samples. In the validation cohort, 2 patients were diagnosed with BCL6-DHL, and 1 patient was deemed similarly indeterminate.

Defined as the IHC staining of MYC and BCL2 in lymphoma cells ≥40% and ≥50%, respectively.

In situ hybridization of EBER for diagnosis, with EBER positivity defined as >80% of neoplastic cells.

In the training cohort, 2 patients from follicular lymphoma, 2 from marginal zone lymphoma, and 1 from mature B-cell neoplasm. In the validation cohort, 1 patient from follicular lymphoma, and 1 from marginal zone lymphoma.

After a median follow-up of 28.0 months (supplemental Figure S2), both median PFS and median OS were not reached among the intent-to-treat (ITT) population of 160 patients. The 2-year PFS and OS rates were 68.3% and 75.7%, respectively. There were no significant differences in PFS or OS between the training and validation cohorts.

Levels of LMR, CD4MMR, and CD8MMR stratified by patient characteristics

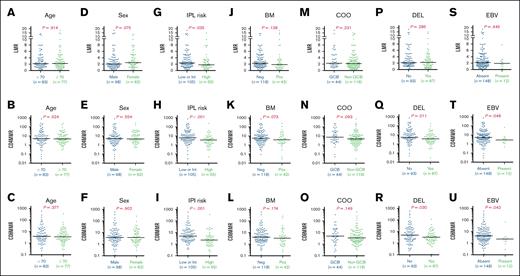

For all 160 patients in the ITT group, the levels of LMR, CD4MMR, and CD8MMR before any lymphoma treatment were stratified based on age (≥70 years vs <70 years), sex (male vs female), IPI scores (low or intermediate risk vs high risk), bone marrow (BM) involvement by lymphoma (negative vs positive), COO per the Hans algorithm (GCB vs non-GCB), double IHC expression of cMYC and BCL2 (DEL vs non-DEL), and EBV+ DLBCL status (present vs absent).

As illustrated in Figure 1, patients with high-risk IPI scores exhibited significantly lower levels of LMR, CD4MMR, and CD8MMR than those with low- or intermediate-risk IPI scores. Additionally, patients classified as DEL also displayed significantly lower levels of CD4MMR and CD8MMR when compared with patients with non-DEL. Those with EBV+ DLBCL showed significantly lower levels of CD4MMR and CD8MMR than patients without EBV+ DLBCL.

The immune cell ratios based on clinical characteristics for 160 patients with DLBCL. The LMR, the ratios of CD4 T lymphocytes to M-MDSCs (CD4MMR), and the ratios of CD8 T lymphocytes to M-MDSCs (CD8MMR) were displayed across various stratifications, including age (A-C), sex (D-F), IPI risk (G-I), BM involvement (J-L), COO (M-O), DEL (P-R), and EBV+ DLBCL (S-U). Int, intermediate; Neg, negative; Pos, positive.

The immune cell ratios based on clinical characteristics for 160 patients with DLBCL. The LMR, the ratios of CD4 T lymphocytes to M-MDSCs (CD4MMR), and the ratios of CD8 T lymphocytes to M-MDSCs (CD8MMR) were displayed across various stratifications, including age (A-C), sex (D-F), IPI risk (G-I), BM involvement (J-L), COO (M-O), DEL (P-R), and EBV+ DLBCL (S-U). Int, intermediate; Neg, negative; Pos, positive.

Otherwise, male patients tended to have lower LMR levels than female patients; patients with the non-GCB subtype showed a trend toward lower levels of CD4MMR and CD8MMR than those with the GCB subtype; patients with BM involvement exhibited a trend of lower LMR, CD4MMR, and CD8MMR than those without such involvement.

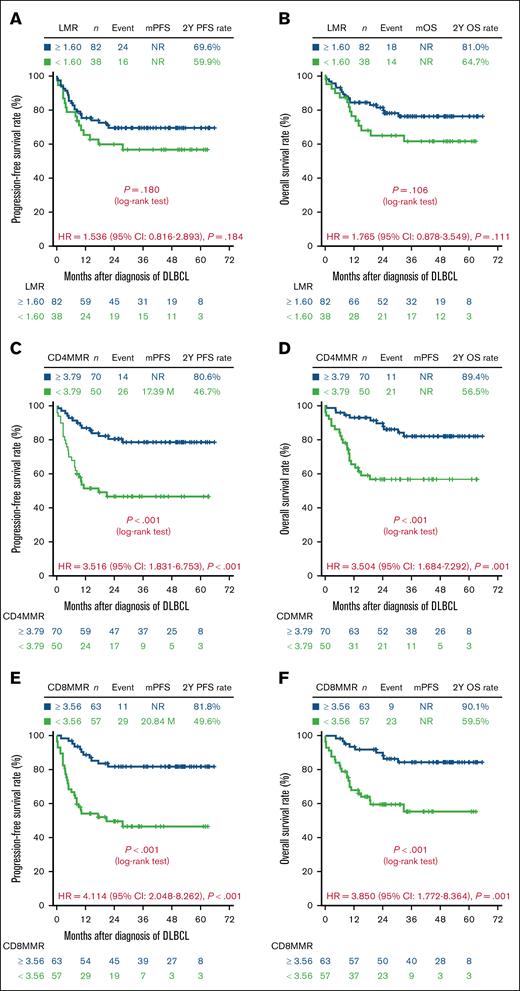

PFS and OS stratified by LMR, CD4MMR, and CD8MMR (training cohort)

To evaluate the prognostic impact of LMR, CD4MMR, and CD8MMR in the training cohort of 120 patients with DLBCL, we first assessed their discriminative ability using receiver operating characteristic curve analysis and corresponding AUC values to determine optimal cutoff thresholds (supplemental Figures S3-S5; supplemental Tables S3-S6). PFS and OS were then analyzed according to these stratifications, as shown in Figure 2.

Survival outcomes of 120 patients with DLBCL based on immune cell ratios in the training cohort. The PFS and OS were categorized according to 3 specific immune cell ratios: LMR (A-B), ratios of CD4 T lymphocytes to M-MDSCs (CD4MMR) (C-D), and ratios of CD8 T lymphocytes to M-MDSCs (CD8MMR) (E-F). P values were calculated using Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; mOS, median OS; mPFS, median PFS; NR, not reached.

Survival outcomes of 120 patients with DLBCL based on immune cell ratios in the training cohort. The PFS and OS were categorized according to 3 specific immune cell ratios: LMR (A-B), ratios of CD4 T lymphocytes to M-MDSCs (CD4MMR) (C-D), and ratios of CD8 T lymphocytes to M-MDSCs (CD8MMR) (E-F). P values were calculated using Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; mOS, median OS; mPFS, median PFS; NR, not reached.

Patients with an LMR <1.60 exhibited a trend toward inferior PFS and OS compared with those with an LMR ≥1.60 (Figure 2A-B). However, the discriminatory performance of LMR for predicting PFS and OS was poor, with AUC values consistently close to 0.5 across all time points (supplemental Figure S3), suggesting that LMR had limited prognostic utility in this cohort.

In contrast, CD4MMR demonstrated moderate discriminative ability across time points (supplemental Figures S4 and S5; AUC range, 0.700-0.796). Patients with a CD4MMR <3.79 had significantly shorter PFS and OS than those with a CD4MMR ≥3.79 (Figure 2C-D). Notably, CD8MMR showed the strongest prognostic performance among the 3 indices, with consistently high AUC values for both PFS and OS (supplemental Figures S4 and S5; AUC range, 0.781-0.849), indicating good discriminative accuracy throughout the follow-up period. Patients with a CD8MMR <3.56 had significantly worse survival outcomes compared with those with a CD8MMR ≥3.56, as shown by 2-year PFS rates of 54.6% vs 90.2%, and 2-year OS rates of 50.0% vs 95.0%, respectively (Figure 2E-F).

Determination of CD8MMR as an independent predictor of PFS and OS in patients with untreated DLBCL (training cohort)

Various multivariate Cox regression analysis models were used to determine whether CD4MMR and CD8MMR could serve as independent predictors of survival in patients with untreated DLBCL (Table 2).

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses of prognostic predictors in 120 patients with DLBCL before treatment initiation (training cohort)

| Clinical factors . | Univariate . | Multivariate∗,† . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Id . | Model IIe . | Model IIIf . | ||||||

| HR (95% CI) . | P value . | HR (95% CI) . | P value . | HR (95% CI) . | P value . | HR (95% CI) . | P value . | |

| PFS | ||||||||

| Age, ≥70 years | 1.857 (0.986-3.497) | .055 | 2.278 (1.194-4.347) | .013 | 2.219 (1.153-4.271) | .017 | 2.006 (1.065-3.781) | .031 |

| Sex, female | 0.973 (0.513-1.846) | .934 | ||||||

| High-risk IPI | 2.105 (1.130-3.920) | .019 | ||||||

| BM involvement | 2.346 (1.244-4.422) | .008 | 3.100 (1.572-6.113) | .001 | 2.443 (1.228-4.859) | .011 | 2.716 (1.437-5.133) | .002 |

| Non-GCB subtype‡ | 1.908 (0.843-4.316) | .121 | ||||||

| DEL | 2.029 (1.087-3.785) | .026 | 1.993 (1.067-3.722) | .031 | 1.711 (0.906-3.229) | .098 | ||

| EBV+ DLBCL | 1.900 (0.744-4.851) | .179 | 3.250 (1.202-8.791) | .020 | 3.386 (1.218-9.413) | .019 | ||

| LMR <1.60 | 1.536 (0.816-2.893) | .184 | ||||||

| CD4MMR <3.79 | 3.516 (1.831-6.753) | <.001 | – | 2.740 (1.393-5.393) | .004 | |||

| CD8MMR <3.56 | 4.114 (2.048-8.262) | <.001 | – | – | 4.396 (2.184-8.846) | <.001 | ||

| OS | ||||||||

| Age, ≥70 years | 2.165 (1.058-4.431) | .034 | 2.955 (1.404-6.221) | .004 | 2.690 (1.286-5.627) | .009 | 2.670 (1.289-5.532) | .008 |

| Sex, female | 1.289 (0.641-2.592) | .477 | ||||||

| High-risk IPI | 3.164 (1.570-6.376) | <.001 | ||||||

| BM involvement | 3.041 (1.517-6.094) | .002 | 3.746 (1.826-7.687) | <.001 | 2.926 (1.404-6.098) | .004 | 3.584 (1.772-7.249) | <.001 |

| Non-GCB subtype‡ | 1.707 (0.702-4.150) | .238 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| DEL | 2.697 (1.318-5.520) | .007 | 2.886 (1.399-5.955) | .004 | 2.410 (1.150-5.051) | .020 | 2.097 (0.997-4.412) | .051 |

| EBV+ DLBCL | 1.784 (0.626-5.089) | .279 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| LMR <1.60 | 1.765 (0.878-3.549) | .111 | ||||||

| CD4MMR <3.79 | 3.504 (1.684-7.292) | .001 | – | 2.382 (1.097-5.173) | .028 | |||

| CD8MMR <3.56 | 3.850 (1.772-8.364) | .001 | – | – | 3.400 (1.525-7.584) | .003 | ||

| Clinical factors . | Univariate . | Multivariate∗,† . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Id . | Model IIe . | Model IIIf . | ||||||

| HR (95% CI) . | P value . | HR (95% CI) . | P value . | HR (95% CI) . | P value . | HR (95% CI) . | P value . | |

| PFS | ||||||||

| Age, ≥70 years | 1.857 (0.986-3.497) | .055 | 2.278 (1.194-4.347) | .013 | 2.219 (1.153-4.271) | .017 | 2.006 (1.065-3.781) | .031 |

| Sex, female | 0.973 (0.513-1.846) | .934 | ||||||

| High-risk IPI | 2.105 (1.130-3.920) | .019 | ||||||

| BM involvement | 2.346 (1.244-4.422) | .008 | 3.100 (1.572-6.113) | .001 | 2.443 (1.228-4.859) | .011 | 2.716 (1.437-5.133) | .002 |

| Non-GCB subtype‡ | 1.908 (0.843-4.316) | .121 | ||||||

| DEL | 2.029 (1.087-3.785) | .026 | 1.993 (1.067-3.722) | .031 | 1.711 (0.906-3.229) | .098 | ||

| EBV+ DLBCL | 1.900 (0.744-4.851) | .179 | 3.250 (1.202-8.791) | .020 | 3.386 (1.218-9.413) | .019 | ||

| LMR <1.60 | 1.536 (0.816-2.893) | .184 | ||||||

| CD4MMR <3.79 | 3.516 (1.831-6.753) | <.001 | – | 2.740 (1.393-5.393) | .004 | |||

| CD8MMR <3.56 | 4.114 (2.048-8.262) | <.001 | – | – | 4.396 (2.184-8.846) | <.001 | ||

| OS | ||||||||

| Age, ≥70 years | 2.165 (1.058-4.431) | .034 | 2.955 (1.404-6.221) | .004 | 2.690 (1.286-5.627) | .009 | 2.670 (1.289-5.532) | .008 |

| Sex, female | 1.289 (0.641-2.592) | .477 | ||||||

| High-risk IPI | 3.164 (1.570-6.376) | <.001 | ||||||

| BM involvement | 3.041 (1.517-6.094) | .002 | 3.746 (1.826-7.687) | <.001 | 2.926 (1.404-6.098) | .004 | 3.584 (1.772-7.249) | <.001 |

| Non-GCB subtype‡ | 1.707 (0.702-4.150) | .238 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| DEL | 2.697 (1.318-5.520) | .007 | 2.886 (1.399-5.955) | .004 | 2.410 (1.150-5.051) | .020 | 2.097 (0.997-4.412) | .051 |

| EBV+ DLBCL | 1.784 (0.626-5.089) | .279 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| LMR <1.60 | 1.765 (0.878-3.549) | .111 | ||||||

| CD4MMR <3.79 | 3.504 (1.684-7.292) | .001 | – | 2.382 (1.097-5.173) | .028 | |||

| CD8MMR <3.56 | 3.850 (1.772-8.364) | .001 | – | – | 3.400 (1.525-7.584) | .003 | ||

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Multivariate Cox regression model (the backward stepwise method) included all available variables with P value <.200.

Age and sex were forced into the multivariate analysis because they may confound comparisons between patients.

According to the Hans algorithm, by IHC stain.

Model I selected 8 factors: age ≥70 years, sex, high-risk IPI, bone marrow involvement by lymphoma, non-GCB subtype, DEL, EBV-positive DLBCL, and LMR <1.60.

Model II selected 9 factors: the 8 factors in Model I plus CD4MMR <3.79.

Model III selected 10 factors: the 9 factors in Model II plus CD8MMR <3.56.

In model I, 8 factors were included: age (≥70 years), sex, high-risk IPI, BM involvement by lymphoma, non-GCB subtype, DEL, EBV+ DLBCL, and LMR (<1.60). The results indicated that age (≥70 years), BM involvement by lymphoma, DEL, and EBV+ DLBCL were independent predictors of poor PFS, whereas age (≥70 years), BM involvement by lymphoma, and DEL were independent predictors of poor OS.

In model II, CD4MMR (<3.79) was added to the 8 factors from model I. The analysis revealed that age (≥70 years), BM involvement by lymphoma, EBV+ DLBCL, and CD4MMR (<3.79) were independent predictors of poor PFS, whereas age (≥70 years), BM involvement by lymphoma, DEL, and CD4MMR (<3.79) were independent predictors of poor OS.

In model III, CD8MMR (<3.56) was included alongside the 9 factors from model II, resulting in a total of 10 factors. Notably, CD8MMR (<3.56) was identified as an independent predictor of both PFS and OS. In addition, age (≥70 years) and BM involvement by lymphoma were recognized as independent predictors of poor PFS and OS.

Comparative analysis of LMR, CD4MMR, and CD8MMR in predicting prognosis of patients with untreated DLBCL (training cohort)

Supplemental Table S7 displayed the AIC and BIC values for LMR, CD4MMR, and CD8MMR in predicting disease progression. Specifically, the AIC values were 164 for LMR, 152 for CD4MMR, and 150 for CD8MMR. The corresponding BIC values were 172 for LMR, 160 for CD4MMR, and 158 for CD8MMR. These metrics indicate that CD8MMR and CD4MMR have superior predictive accuracy compared with LMR for disease progression in patients with untreated DLBCL.

In addition, supplemental Table S8 presented the AIC and BIC values for predicting mortality. The AIC values for LMR, CD4MMR, and CD8MMR were 148, 140, and 140, respectively, whereas the BIC values were 156, 148, and 148. These findings further highlight the improved predictive performance of CD8MMR and CD4MMR over LMR in estimating mortality for patients with untreated DLBCL.

Confirmation of the prognostic value of CD8MMR in patients with untreated DLBCL (validation cohort)

To further confirm the prognostic value of CD8MMR in patients with DLBCL before treatment initiation, we first analyzed the PFS and OS stratified by LMR, CD4MMR, and CD8MMR in the validation cohort (supplemental Figure S6). Consistent with the findings from the training cohort, patients with DLBCL with a CD8MMR <3.56 exhibited significantly poorer PFS and OS than those with a CD8MMR ≥3.56 (supplemental Figure S6E-F).

Next, we assessed the AIC and BIC values for LMR, CD4MMR, and CD8MMR within the validation cohort (supplemental Tables S9 and S10). As shown in supplemental Table S9, CD8MMR had the lowest AIC and BIC values for predicting progressive disease. Similarly, in supplemental Table S10, CD8MMR also demonstrated the lowest AIC and BIC values for predicting mortality.

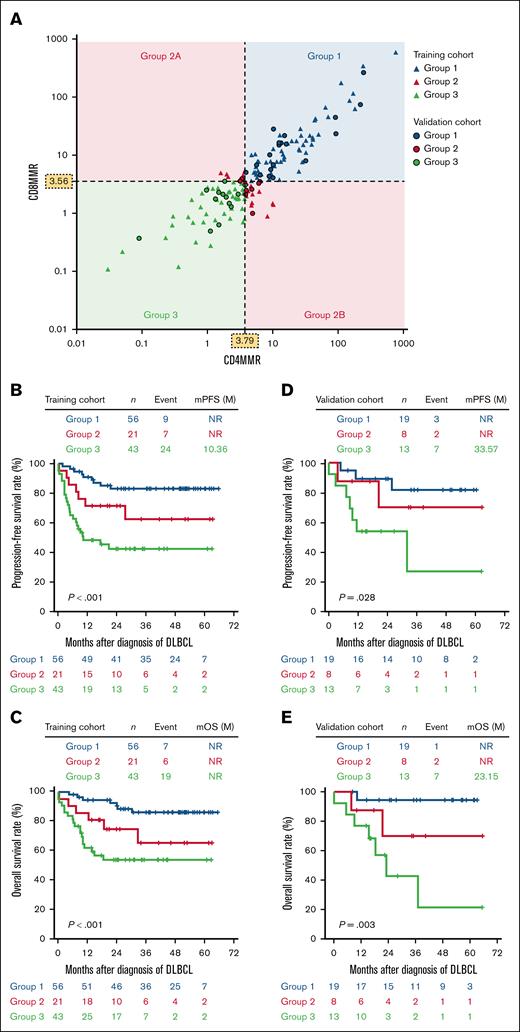

Subcategorizing patients with untreated DLBCL based on CD4MMR and CD8MMR

We proceeded to subcategorize patients with untreated DLBCL into 3 groups based on their CD8MMR and CD4MMR levels (Figure 3A): group 1 included patients with CD8MMR ≥3.56 and CD4MMR ≥3.79; group 3 included patients with CD8MMR <3.56 and CD4MMR <3.79; patients with discordant CD8MMR and CD4MMR values were assigned to group 2.

Stratification of patients with DLBCL based on CD8MMR and CD4MMR. (A) CD8MMR and CD4MMR were combined to categorize patients with DLBCL into 3 distinct groups: group 1 includes patients with CD8MMR ≥3.56 and CD4MMR ≥3.79; group 3 consists of patients with CD8MMR <3.56 and CD4MMR <3.79; and group 2 includes patients who do not meet the criteria for either group 1 or group 3. In the training cohort of 120 patients with DLBCL, PFS (B) and OS (C) were analyzed according to group 1, group 2, and group 3. Similarly, among the validation cohort of 40 patients with DLBCL, PFS (D) and OS (E) were assessed by group 1, group 2, and group 3. P values were calculated using Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests. mOS, median OS; mPFS, median PFS; NR, not reached.

Stratification of patients with DLBCL based on CD8MMR and CD4MMR. (A) CD8MMR and CD4MMR were combined to categorize patients with DLBCL into 3 distinct groups: group 1 includes patients with CD8MMR ≥3.56 and CD4MMR ≥3.79; group 3 consists of patients with CD8MMR <3.56 and CD4MMR <3.79; and group 2 includes patients who do not meet the criteria for either group 1 or group 3. In the training cohort of 120 patients with DLBCL, PFS (B) and OS (C) were analyzed according to group 1, group 2, and group 3. Similarly, among the validation cohort of 40 patients with DLBCL, PFS (D) and OS (E) were assessed by group 1, group 2, and group 3. P values were calculated using Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests. mOS, median OS; mPFS, median PFS; NR, not reached.

For the 120 patients with DLBCL in the training cohort (Figure 3B-C), there was a gradual decline in PFS and OS from group 1 to group 2, and further to group 3. For the 40 patients with DLBCL in the validation cohort (Figure 3D-E), a comparable decline in PFS and OS was observed from group 1 to group 2 and further to group 3.

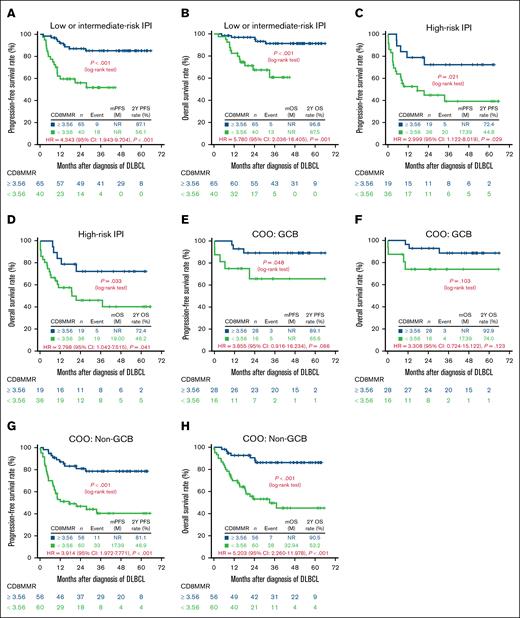

CD8MMR as a prognostic discriminator stratified by IPI risk and COO

CD8MMR further discriminated prognosis when stratified by IPI risk (low or intermediate risk vs high risk) and COO (GCB vs non-GCB), as shown in Figure 4.

Discrimination of survival outcomes based on CD8MMR among 160 patients with DLBCL categorized by IPI risk or COO. (A) PFS and (B) OS in patients with low- or intermediate-risk IPI; (C) PFS and (D) OS in patients with high-risk IPI; (E) PFS and (F) OS in patients with GCB subtype; (G) PFS and (H) OS in patients with non-GCB subtype. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; mOS, median OS; mPFS, median PFS; nNR, not reached.

Discrimination of survival outcomes based on CD8MMR among 160 patients with DLBCL categorized by IPI risk or COO. (A) PFS and (B) OS in patients with low- or intermediate-risk IPI; (C) PFS and (D) OS in patients with high-risk IPI; (E) PFS and (F) OS in patients with GCB subtype; (G) PFS and (H) OS in patients with non-GCB subtype. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; mOS, median OS; mPFS, median PFS; nNR, not reached.

For patients with DLBCL categorized as low or intermediate IPI risk, those with CD8MMR <3.56 experienced significantly worse PFS and OS compared with those with CD8MMR ≥3.56 (Figure 4A-B). Similarly, among patients with high-risk IPI, those with CD8MMR <3.56 also demonstrated significantly worse PFS and OS compared with those with CD8MMR ≥3.56 (Figure 4C-D).

In the GCB subtype, patients with CD8MMR <3.56 had significantly worse PFS compared with those with CD8MMR ≥3.56 (Figure 4E), with a trend toward poorer OS in patients with CD8MMR <3.56 than those with CD8MMR ≥3.56 (Figure 4F). Furthermore, for patients with the non-GCB subtype, those with CD8MMR <3.56 were associated with significantly worse PFS and OS compared with those with CD8MMR ≥3.56 (Figure 4G-H).

Prognostic impact of CD8MMR across first-line regimens

Among the 160 patients in the ITT group, the standard first-line regimen was R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone). Patients could be scheduled for R-EPOCH (rituximab, etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin) if they met any of the following criteria: (1) IPI score ≥3 (high-intermediate or high risk), (2) bulky disease >7.5 cm, (3) DHL confirmed by fluorescence in situ hybridization, (4) EBV+ DLBCL, or (5) cardiac concern as determined by the treating physician.

Overall, 126 patients were scheduled for R-CHOP and 34 for R-EPOCH as first-line therapy; the latter group was most frequently assigned due to higher IPI scores or bulky disease (supplemental Figure S7). Compared with those scheduled for R-CHOP, patients scheduled for R-EPOCH were significantly younger and had a higher prevalence of bulky disease (supplemental Table S11). Regarding survival outcomes, no significant differences in PFS or OS were observed between the 2 groups (supplemental Figure S8). When the first-line regimen (R-CHOP vs R-EPOCH) was included as a covariate in multivariate Cox regression models of either the training cohort (supplemental Table S12) or the ITT population (supplemental Table S13), low CD8MMR (<3.56) consistently remained an independent predictor of inferior PFS and OS.

In the subgroup of 126 patients scheduled for R-CHOP, those with low CD8MMR (<3.56) had significantly shorter PFS and OS (supplemental Figure S9E-F). Among the 34 patients scheduled for R-EPOCH, the limited sample size reduced statistical power, but a similar trend toward inferior PFS and OS was still observed in those with low CD8MMR (supplemental Figure S10E-F).

Discussion

In this prospective, observational study, 160 patients with DLBCL were enrolled before initiating any treatment. Participants were randomized into either a training or validation cohort to evaluate the clinical impact of CD8MMR and CD4MMR, and to determine if these novel biological markers are superior to LMR.

Our study revealed several key findings. First, patients with high-risk IPI, DEL, or EBV+ DLBCL exhibited significantly lower levels of CD8MMR and CD4MMR than those with low- or intermediate-risk IPI, non-DEL, or EBV− DLBCL (Figure 1). Second, patients with DLBCL with low levels of CD8MMR or CD4MMR had significantly worse PFS and OS than those with high levels of these markers (Figure 2; supplemental Figure S6). Third, CD8MMR was an independent predictor of PFS and OS in the Cox regression model that included CD8MMR, CD4MMR, and LMR (Table 2). CD4MMR was also an independent predictor of PFS and OS in the model that included CD4MMR and LMR but excluded CD8MMR. Fourth, compared with CD4MMR and LMR, CD8MMR demonstrated the lowest AIC and BIC values for predicting PFS and OS in untreated DLBCL (supplemental Tables S7-S10), indicating superior prognostic value. Fifth, patients with DLBCL with both high CD8MMR and high CD4MMR had the best survival outcomes, whereas patients with both low CD8MMR and low CD4MMR experienced the worst survival outcomes (Figure 3). Sixth, CD8MMR further stratified PFS and OS outcomes in patients with DLBCL when analyzed within subgroups defined by IPI risk and COO (Figure 4).

Although CD8 T lymphocytes are the main effector cells in adaptive immunity and are responsible for killing tumor cells, CD4 T lymphocytes support the activation of CD8 T lymphocytes and coordinate with many other immune cells. Both circulating CD8 and CD4 T lymphocytes have been proposed as prognostic factors in patients with newly diagnosed DLBCL.10-15 A higher number of circulating CD8 or CD4 T lymphocytes is associated with a better prognosis, suggesting that increased numbers of these cells are beneficial for mounting an effective antitumor response, even though T cells can be effector, memory, or exhausted.

M-MDSCs are immunosuppressive cells that impair the immune system’s ability to fight cancer.32 They can recruit more regulatory T cells (Treg) into the tumor microenvironment and drive the differentiation of CD4 T lymphocytes toward Treg. M-MDSCs express programmed death-ligand 1 to induce the apoptosis of T cells, alter or modify tumor-antigen peptides to interfere with T-cell receptor recognition, and impair subsequent activation. M-MDSCs also downregulate the fitness and proliferation of T cells by depleting essential metabolites within the tumor microenvironment.

The ratios of CD8 or CD4 T lymphocytes to M-MDSCs (CD8MMR or CD4MMR) can be likened to a seesaw. On one end are the antitumor cells (CD8 and CD4 T lymphocytes), and on the other end are the protumor cells (M-MDSCs). A higher ratio indicates a more robust antitumor immune response, whereas a lower ratio suggests more substantial immunosuppression and tumor progression. However, CD4 T lymphocytes comprise functionally diverse subsets, including T helper 1 (TH1), T helper 2 (TH2), T helper 17 (Th17), regulatory T cells (Treg), and T follicular helper cells (TFH). Treg are immunosuppressive and generally considered to be protumor cells, with studies indicating that circulating Treg are increased in patients with DLBCL.33

In our cohort, we collected all CD4 T lymphocytes, including Treg, even though Treg cells account for ∼5% of CD4 T cells in peripheral blood. Some patients with DLBCL may have abnormally high percentages of circulating Treg, especially those with advanced stages and high-risk IPI (data not shown). This could explain why CD4MMR has lower predictive power in the multivariate Cox regression model than CD8MMR. In contrast, TH1 cells usually outnumber Treg and represent the highest proportion among circulating CD4 T lymphocytes. These TH1 cells collaborate with CD8 T cells to fight against cancer cells. As shown in Figure 3, patients with DLBCL with both high CD8MMR and high CD4MMR had the best PFS and OS, whereas those with both low CD8MMR and low CD4MMR had the worst outcomes.

LMR demonstrated limited discriminative power in predicting survival in our study. This limitation may partly stem from the heterogeneity of immune cell populations encompassed within both lymphocytes and monocytes, as well as from the heterogeneous characteristics of the enrolled patient population. Specifically, the lymphocyte compartment comprises diverse subsets, including CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells, natural killer cells, and B cells, whereas the monocyte compartment includes classical and nonclassical monocytes, as well as M-MDSCs. Cellular diversity implies that the biological and clinical significance of LMR can vary among individuals with differing immune profiles. In addition, our training cohort included a relatively high proportion of patients at advanced stage (nearly 40% with stage IV disease, more than one-third with high-risk IPI, and over one-fourth with BM involvement), which further increases interpatient variability and may contribute to the limited prognostic performance of LMR observed in this study.

BM is one of the major sites for the expansion and conditioning of M-MDSCs, which subsequently migrate and become pathologically activated in peripheral tissues, such as within tumors.34 For patients with DLBCL with BM involvement, the BM can serve as a favorable microenvironment that facilitates the expansion and accumulation of M-MDSCs. This could explain our finding that patients with DLBCL with BM involvement tend to have lower values of CD8MMR and CD4MMR than those without BM involvement (Figure 1). Furthermore, BM involvement by lymphoma is an independent poor prognostic factor for PFS and OS, as demonstrated in the multivariate Cox regression models (Table 2).

With respect to COO, we observed that patients with non-GCB DLBCL with low CD8MMR experienced significantly worse PFS and OS compared with those with high CD8MMR (Figure 4G-H). Among patients with DLBCL with the GCB subtype (Figure 4E-F), low CD8MMR was also associated with significantly inferior PFS, although the difference in OS did not reach statistical significance. The smaller proportion of patients with the GCB subtype in Asian populations could partly explain this lack of significance in OS among patients with the GCB subtype.35 Additionally, the survival disparity between low and high CD8MMR was more pronounced in the non-GCB subtype. This pattern likely reflects 2 factors: (1) patients with high CD8MMR showed similar survival outcomes in both GCB and non-GCB subtypes, whereas (2) patients with low CD8MMR experienced poorer survival in the non-GCB subtype than in the GCB subtype.

Modern molecular classification systems, such as LymphGen36,37 and DLBclass,38,39 are primarily defined by the genetic features of lymphoma cells. More recently, the MD Anderson Cancer Center introduced LymphoMAP, which incorporates non-B cells within the lymphoma microenvironment and delineates 3 archetypal profiles.40 Among them, the LN-archetype is enriched in patients with DLBCL GCB subtype and characterized by naïve and memory T cells, whereas the TEX-archetype is enriched in patients with DLBCL ABC subtype and marked by superactivated macrophages and exhausted CD8 T cells. Building on these insights, CD8MMR could be further refined by distinguishing memory from exhausted CD8 T cells, and by integrating the relationship between circulating and tumor-infiltrating CD8 T cells.

Our study demonstrates that patients with EBV+ DLBCL exhibit significantly lower CD8MMR and CD4MMR values than those with EBV− disease (Figure 1). Clinically, EBV+ DLBCL has been associated with inferior survival outcomes following chemotherapy,41,42 although the prognostic gap appears attenuated when patients receive immunochemotherapy.43-45 Whether reduced T-cell levels contribute to EBV reactivation or, conversely, EBV infection drives alterations in T-cell populations remains uncertain. Moreover, EBV positivity in DLBCL does not necessarily reflect active EBV viremia. The mechanisms by which EBV shapes or reprograms the lymphoma microenvironment remain incompletely understood and warrant further investigation.

Our study has several limitations. First, the limited number of participants may obscure some clinical characteristics that are not readily apparent. Second, our results require further external validation in clinical trials to confirm their robustness and applicability in broader patient populations. Nevertheless, we utilized a prospective and randomized design to minimize bias and enhance the reliability of our observations. Third, our current cohort included all CD4 T lymphocytes, and future studies may consider excluding Treg due to their immunosuppressive nature.

In conclusion, the ratio of CD8 T lymphocytes to M-MDSCs (CD8MMR) is a novel prognostic predictor for patients with newly diagnosed DLBCL before initiating treatment. A low level of CD8MMR is associated with worse survival outcomes and can further discriminate PFS and OS in patients with DLBCL when analyzed within subgroups defined by IPI risk and COO. Our study provides valuable insights into the prognostic significance of CD8MMR, warranting further investigation to validate its clinical utility.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank all participating patients, without whom this study would not have been possible. They are grateful to Chiu-Mei Yeh (National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University) for her statistical consultation, and to Brent Stewart for his assistance with scientific editing.

This study was supported by grants from the Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST 108-2314-B-075-070-MY3 and MOST 111-2314-B-075-037), Taipei Veterans General Hospital (V110B-012), the Yin Shu-Tien Foundation at Taipei Veterans General Hospital and National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University for the Excellent Physician Scientists Cultivation Program (number 112-V-B-040), the Chong Hin Loon Memorial Cancer and Biotherapy Research Center, the Melissa Lee Cancer Foundation, and the Taiwan Clinical Oncology Research Foundation.

Authorship

Contribution: H.-Y.W. designed the study; H.-Y.W., C.-K.T., P.-S.K., and Y.-C.L. were responsible for caring for the patients enrolled in the study; H.-Y.W., F.-C.Y., and P.-C.L. performed all flow cytometry experiments and statistical analyses; H.-Y.W., F.-C.Y., and C.-F.Y. acquired the data; H.-Y.W. and N.-J.C. interpreted the results; J.-P.G., J.-H.L., and P.-M.C. verified the data and results; H.-Y.W. drafted the manuscript; H.-Y.W. and N.-J.C. had full access to all the data in the study, acted as guarantors, and took responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole; and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Hao-Yuan Wang, Division of Hematology and Oncology, Department of Medicine, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, No. 201, Sec. 2, Shipai Rd, Beitou District, Taipei 112, Taiwan; email: B101091114@tmu.edu.tw; and Nien-Jung Chen, Institute of Microbiology and Immunology, School of Life Sciences, National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, No. 155, Sec. 2, Linong St, Beitou District, Taipei 112, Taiwan; email: njchen@nycu.edu.tw.

References

Author notes

The data sets analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author, Hao-Yuan Wang (B101091114@tmu.edu.tw), upon reasonable request in accordance with the Institutional Review Board regulations of Taipei Veterans General Hospital.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.