Key Points

Dapolsertib (MEN1703) is a dual kinase inhibitor of proviral integration site for PIM and FLT3 kinases.

Dapolsertib has a manageable safety profile and activity in a phase 1/2 study in patients with AML.

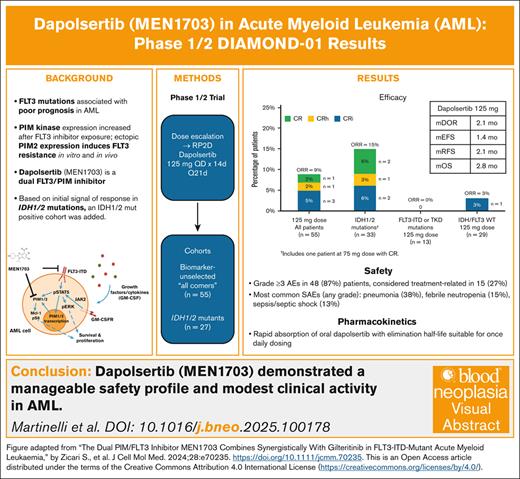

Visual Abstract

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is an aggressive hematopoietic cancer with poor survival outcomes. Despite improvements with recent FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) inhibitors, resistance is common, and responses are short. Dapolsertib (MEN1703) is a novel, first-in-class dual inhibitor of PIM (proviral integration site for Moloney murine leukemia virus) and FLT3 kinases, with activity in both FLT3-mutated and wild-type cells. A phase 1/2 open-label, multicenter, dose-escalation study (DIAMOND-01) investigated the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of single-agent dapolsertib and assessed its safety, efficacy, pharmacokinetic (PK) profile, pharmacodynamic biomarkers, and genomics in patients with AML with no standard therapeutic options available. Seventy-three patients received oral doses of dapolsertib ranging from 25 to 150 mg per day (14 consecutive days over 21-day cycles). In the dose-escalation phase, the MTD was 125 mg and was selected for dose expansion. The most common grade ≥3 adverse events in patients receiving 125 mg were pneumonia (38%), thrombocytopenia (30%), and anemia (27%); most of these events were deemed not treatment related. For patients receiving 125 mg dapolsertib (n = 55), the overall response rate was 9%, with a median 2.07-month duration of response, and 4 of 5 responses were observed in patients with isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1)/IDH2 mutations. PK analysis indicated rapid absorption of oral dapolsertib, an elimination half-life suitable for once daily dosing and a PK independent of formulation and IDH mutational status. Pharmacodynamic activity was confirmed in 50% of evaluable patients. Overall, dapolsertib demonstrated modest single-agent activity in patients with AML. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT03008187.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML), an aggressive hematopoietic cancer derived from clonal proliferation of malignant myeloid blast cells, has increased in both incidence and mortality over the past 30 years.1 Patients with mutations in FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) represent ∼30% of patients with AML,2 and they have a particularly poor prognosis, including shorter remission duration and higher relapse rates, compared with patients with FLT3-unmutated AML.3

Although FLT3-internal tandem duplication (ITD) mutations remain associated with poor prognosis, outcomes have improved recently due to the approval of the FLT3 inhibitors gilteritinib, quizartinib, and midostaurin for the treatment of AML.4-7 Despite these improvements, outcomes in the relapsed/refractory (R/R) setting are suboptimal, responses are typically short-lived, and overall survival (OS) is poor.8-12 Improved treatment options for patients with FLT3-mutated AML, particularly those with R/R disease and prior exposure to an FLT3 inhibitor, remains an unmet medical need.

Mutations in isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) or IDH2 are a genetic feature found in ∼20% of AML cases.2 Although 3 IDH inhibitors are approved for the treatment of AML with IDH mutations (eg, ivosidenib and olutasidenib for IDH1 mutations and enasidenib for IDH2 mutations), outcomes of R/R patients treated with IDH inhibitors are still unsatisfactory, with OS ranging from 9 to 11 months.13-15

Upregulation or overexpression of proviral integration site for Moloney murine leukemia virus (PIM) kinases, particularly PIM-1 and PIM-2, is a recurrent observation in a spectrum of hematologic malignancies, including AML.16,17 The rationale for targeting PIM kinases in AML has spurred significant preclinical research, leading to the evaluation of small-molecule inhibitors, which are in early stage of clinical development.16

PIM kinases are involved in AML pathogenesis and progression and, as effectors of FLT3-ITD activity via PIM-mediated phosphorylation of FLT3 in a positive feedback loop, are considered major drivers of the resistance phenotype.17-20 Increased PIM kinase expression was observed in samples from patients treated with FLT3 inhibitor ex vivo, and ectopic PIM-2 expression induced FLT3 resistance both in vitro and in vivo.17 Furthermore, concomitant inhibition of PIM and FLT3 led to restoration of sensitivity to FLT3 inhibitor activity in resistant cells.17 These results support the notion that simultaneous PIM and FLT3 inhibition may represent an opportunity to improve upon existing therapeutic approaches for AML treatment.

Dapolsertib (MEN1703) is a first-in-class, oral, type I dual PIM/FLT3 inhibitor that targets all isoforms of the PIM kinases, including PIM1, PIM2, and PIM3, as well as FLT3, with activity in FLT3-mutated and FLT3-unmutated AML cells. Dapolsertib has previously demonstrated significant in vitro activity in AML cell lines and primary blasts, irrespective of FLT3 status, as well as in in vivo xenograft AML models.18 The DIAMOND-01 trial is a first-in-human, phase 1/2, open-label study of dapolsertib in patients with AML without standard therapeutic options (NCT03008187). Although the study was initially designed for unselected patients with AML, after an initial signal of response was detected in IDH1/2 mutations in the first phases of the trial, dapolsertib activity was explored in an additional cohort of patients harboring IDH1/2 mutations. Here, we report the results of this study.

Methods

Study design

The DIAMOND-01 trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03008187) was a phase 1/2, open-label, multicenter, dose-escalation, and dose-expansion study designed to evaluate dapolsertib in patients with AML. In the dose-escalation phase, both patients with treatment-naïve AML confirmed unsuitable for induction therapy and those with R/R AML could be enrolled. The primary objective was to estimate the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) and determine the recommended phase 2 dose (RP2D) of dapolsertib.

The dose-expansion phase enrolled only patients with R/R AML who were treated at the RP2D in 2 expansion cohorts: an “all comers” cohort of biomarker-unselected patients with R/R AML and an “IDH mutant” cohort of patients with R/R AML harboring an IDH mutation (IDH1 or IDH2). The primary objective was to further characterize the safety profile of single-agent dapolsertib at the recommended dose level by examining safety data for all treated patients. Secondary objectives included antileukemic efficacy of dapolsertib on overall response rate (ORR), which included complete response (CR), complete remission with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRi), complete remission with partial hematologic recovery (CRh), and morphologic leukemia-free state, as well as duration of response (DoR), relapse-free survival, event-free survival, and OS. Additional secondary endpoints include safety, tolerability, and the pharmacokinetic (PK) profile of dapolsertib; pharmacodynamic activity of dapolsertib was an additional exploratory objective.

The study was conducted at 21 centers across the European Union and the United States in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Council for Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The protocol was approved by appropriately constituted independent ethics committees; written informed consent was provided by all patients before enrollment.

Patients

Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years and had a diagnosis of AML (≥20% blasts in bone marrow [BM] or peripheral blood [PB]), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 to 2, treatment naïve with no standard therapeutic options available (dose-escalation phase only), and either relapsed AML unsuitable for intensive chemotherapy or primary refractory AML unsuitable for intensive chemotherapy (dose-escalation and dose-expansion phases). Initially, R/R biomarker-unselected patients could be enrolled in the first expansion cohort (“all-comers” cohort). After a protocol amendment in April 2021, only patients harboring IDH1 or IDH2 mutations (per local assessment) could be enrolled (“IDH mutant” cohort). Patients naïve to IDH inhibitors were eligible only if no IDH inhibitors were approved or available where enrolled.

Exclusion criteria included prior treatment with a PIM inhibitor, leukocytes >30 × 109/L immediately before the first dose and/or clinical concerns of leukostasis, clinically significant active central nervous system leukemia, hematopoietic stem cell transplant within 4 months of the first dose, or requirement for systemic immune-modulating therapy for the prophylaxis or treatment of graft-versus-host disease.

Treatment

In the dose-escalation phase, the starting dose was 25 mg dapolsertib orally once daily for 14 consecutive days over 21-day treatment cycles. See the supplemental Methods for dose escalation and dose-limiting toxicity definitions. In the dose-expansion phase, patients received 125 mg dapolsertib orally once daily for 14 consecutive days over 21-day treatment cycles.

Treatment with dapolsertib continued until disease progression, intolerable toxicity, or any events leading to withdrawal. Wherever possible, follow-up assessments were conducted every 3 months after the final study visit, regardless of initiation of additional treatments, for up to 1 year.

Safety and tolerability assessments

All patients who received ≥1 doses of dapolsertib were considered evaluable for safety. Adverse events (AE), serious AEs (SAE), and laboratory abnormalities were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for AEs V4.03. The relationship of the study treatment to an AE was determined by the investigator and reviewed by the medical monitor.

Efficacy assessments

The efficacy population included all patients who completed 1 treatment cycle (considering both treatment and washout period, totaling 21 days) and took ≥75% of dapolsertib during the first cycle. Antileukemic activity data were collected throughout the study and summarized by cohort and dose levels. Disease assessment was performed according to the AML Response Criteria described in the 2017 European LeukemiaNet recommendations.21

PK assessments

PK evaluations were performed on all patients who received study drug and had ≥1 measurable drug concentration (PK population). Plasma PK parameters were derived from individual plasma concentration-versus-time profiles of dapolsertib. Urinary PK parameters were also examined. Additional details are in the supplemental Methods.

Pharmacodynamic assessments

The classic PIM kinase substrate pS6 was selected as a potential pharmacodynamic biomarker due to the strong correlation between pS6 inhibition and dapolsertib in vitro and in vivo activity in previous preclinical studies of dapolsertib in AML cell lines.18,22 Additional details are in the supplemental Methods.

Genomic profiling and mutation analysis

AML samples were collected from patients to investigate genomic alterations via next-generation sequencing as described in the supplemental Methods. Because CLK/DYRK kinases are important regulators of serine/arginine-rich splicing factor (SRSF) splice junction enhancer–binding proteins,23 post hoc exploratory analyses were performed focusing on the presence/absence of SRSF2 mutations or mutations in spliceosome genes (SRSF2, U2AF1, and ZRSR2; see the supplemental Methods).

Statistical analysis

Safety and tolerability evaluations were performed via descriptive statistics; the incidence of AE was reported as summary statistics using combinations of Common Terminology Criteria for AE toxicity grade, relationship with study drug, seriousness, System Organ Class or Body System, and Preferred Term. Time-to-event variables were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method.

Results

Participants

Seventy-three patients were enrolled and treated with 25- to 150-mg dapolsertib. Patient characteristics are displayed in Table 1 and supplemental Figure 1. The median age was 68 years (range, 25-84). Most patients (63%) had de novo AML; 26%, 3%, and 8% of patients had AML secondary to myelodysplastic syndrome, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, or previous chemotherapy/radiotherapy, respectively. Thirty-six percent of patients had primary refractory AML, 62% relapsed, and 3% newly diagnosed AML (enrolled only during dose escalation). The median number of prior therapies was 2 (range, 0-6). Twenty-three percent of patients harbored a FLT3 mutation; 23% had an IDH1 mutation, and 23% had an IDH2 mutation; 1 patient harbored both IDH1 and IDH2 mutations (Table 1; supplemental Tables 1-3).

Demographics of study population

| Characteristic . | All doses (N = 73) . | 125-mg dapolsertib (N = 55) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range), y | 68 (25-84) | 68 (33-83) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 40 (55) | 31 (56) |

| Female | 33 (45) | 24 (44) |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 24 (33) | 22 (40) |

| 1 | 45 (62) | 30 (55) |

| 2 | 2 (3) | 2 (4) |

| Not reported | 2 (3) | 1 (2) |

| AML type at diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| De novo | 46 (63) | 35 (64) |

| Secondary | 27 (37) | 20 (36) |

| Cytogenetic risk category, n (%) | ||

| Favorable | 11 (15) | 7 (13) |

| Intermediate | 17 (23) | 15 (27) |

| Unfavorable | 25 (34) | 18 (33) |

| Recorded as unknown | 15 (21) | 12 (22) |

| Other | 1 (1) | 1 (2) |

| Not reported | 4 (6) | 2 (4) |

| AML status at study entry, n (%) | ||

| Primary refractory | 26 (36) | 17 (31) |

| Relapsed, unfit for IC | 44 (60) | 37 (67) |

| ND, unfit for IC | 3 (4) | 1 (2) |

| Previous lines, n (%) | ||

| Median (min-max) | 2 (0-6) | 2 (0-5) |

| 0 | 3 (4) | 1 (2) |

| 1 | 23 (32) | 20 (36) |

| 2 | 23 (32) | 19 (35) |

| ≥3 | 24 (33) | 15 (27) |

| Mutation, n (%)∗ | ||

| FLT3 | 17 (23.3) | 13 (23.6) |

| IDH1† | 17 (23.3) | 13 (23.6) |

| IDH2† | 17 (23.3) | 15 (27.3) |

| NPM1 | 15 (20.5) | 13 (23.6) |

| DNMT3A | 12 (16.4) | 8 (14.5) |

| ASXL1 | 13 (17.8) | 6 (10.9) |

| SRSF2 | 6 (8.2) | 4 (7.3) |

| Characteristic . | All doses (N = 73) . | 125-mg dapolsertib (N = 55) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range), y | 68 (25-84) | 68 (33-83) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 40 (55) | 31 (56) |

| Female | 33 (45) | 24 (44) |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 24 (33) | 22 (40) |

| 1 | 45 (62) | 30 (55) |

| 2 | 2 (3) | 2 (4) |

| Not reported | 2 (3) | 1 (2) |

| AML type at diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| De novo | 46 (63) | 35 (64) |

| Secondary | 27 (37) | 20 (36) |

| Cytogenetic risk category, n (%) | ||

| Favorable | 11 (15) | 7 (13) |

| Intermediate | 17 (23) | 15 (27) |

| Unfavorable | 25 (34) | 18 (33) |

| Recorded as unknown | 15 (21) | 12 (22) |

| Other | 1 (1) | 1 (2) |

| Not reported | 4 (6) | 2 (4) |

| AML status at study entry, n (%) | ||

| Primary refractory | 26 (36) | 17 (31) |

| Relapsed, unfit for IC | 44 (60) | 37 (67) |

| ND, unfit for IC | 3 (4) | 1 (2) |

| Previous lines, n (%) | ||

| Median (min-max) | 2 (0-6) | 2 (0-5) |

| 0 | 3 (4) | 1 (2) |

| 1 | 23 (32) | 20 (36) |

| 2 | 23 (32) | 19 (35) |

| ≥3 | 24 (33) | 15 (27) |

| Mutation, n (%)∗ | ||

| FLT3 | 17 (23.3) | 13 (23.6) |

| IDH1† | 17 (23.3) | 13 (23.6) |

| IDH2† | 17 (23.3) | 15 (27.3) |

| NPM1 | 15 (20.5) | 13 (23.6) |

| DNMT3A | 12 (16.4) | 8 (14.5) |

| ASXL1 | 13 (17.8) | 6 (10.9) |

| SRSF2 | 6 (8.2) | 4 (7.3) |

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; IC, intensive chemotherapy; ND, newly diagnosed; PS, performance status.

Full list of common mutations found in ≥3 patients available in supplemental Table 1.

One patient treated at 125 mg (“IDH mutant” cohort) had IDH1/2, with IDH1 and IDH2 mutations coexpressed at the same time. Thus, the number of patients with IDH mutations totals 33 overall and 27 at 125 mg.

Determination of dapolsertib MTD/RP2D

In the dose-escalation phase, 25 patients were treated at the following doses: 25 mg (n = 2), 50 mg (n = 3), 75 mg (n = 3), 100 mg (n = 6), 125 mg (n = 7), and 150 mg (n = 4). Five patients experienced dose-limiting toxicities, including 1 grade 3 hypophosphatemia at the 25-mg dose level, 1 grade 4 pneumonia fungal leading to fatal respiratory distress at the 125-mg dose level, and 4 events occurring in 3 patients at the 150-mg dose level: 2 grade 3 events of transaminase increase/alanine aminotransferase increase, 1 grade 5 cerebral venous thrombosis, and 1 grade 3 blood alkaline phosphatase increase.

The MTD/RP2D of dapolsertib was determined to be 125 mg; patients received this dose for the expansion phase. The demographics of the MTD/RP2D population were similar to the overall population (Table 1).

Safety and tolerability

Overall, 72 patients (99%) reported at least 1 AE. Grade ≥3 AE were reported in 65 patients (89%) and considered treatment related in 23 (32%). SAE were reported in 48 patients (66%). Supplemental Table 4 summarizes the most common grade ≥3 AE and SAE.

Fifty-five patients received 125-mg dapolsertib (Table 2; supplemental Table 5). These patients received a median of 2 cycles of dapolsertib (range, 1-29), with a median duration of exposure of 35 days (range, 9-611). AEs leading to drug interruption occurred in 18 patients (33%); no AE resulted in dose reductions. Grade ≥3 AE were reported in 48 patients (87%) and were considered treatment related in 15 (27%). The most common grade ≥3 treatment-related AE was hyponatremia in 4 patients (7%). Similar to the overall population, the most common SAE (any grade) included pneumonia in 21 patients (38%; 3 [6%] due to fungal infection, 1 [2%] due to bacterial infection, and 17 [31%] with no pathogen isolated), febrile neutropenia in 8 patients (15%), and sepsis/septic shock in 7 patients (13%). Most common AE in the 125-mg group are summarized in Table 2.

Most common AEs by preferred term at 125-mg dapolsertib dose level (n = 55)

| Grade ≥3 AEs occurring in ≥10% of patients, n (%) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preferred term . | Grade ≥3 . | Treatment-related grade ≥3 . |

| Hematologic | ||

| Thrombocytopenia∗ | 17 (31) | 2 (4) |

| Anemia | 15 (27) | 0 (0) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 10 (18) | 2 (4) |

| Neutropenia† | 10 (18) | 2 (4) |

| Leukocytosis | 7 (13) | 0 (0) |

| Nonhematologic | ||

| Pneumonia‡ | 21§ (38) | 1 (2) |

| Asthenia∥ | 9 (16) | 2 (4) |

| Sepsis¶ | 7 (13) | 1 (2) |

| ALT increased | 6 (11) | 3 (6) |

| Grade ≥3 AEs occurring in ≥10% of patients, n (%) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preferred term . | Grade ≥3 . | Treatment-related grade ≥3 . |

| Hematologic | ||

| Thrombocytopenia∗ | 17 (31) | 2 (4) |

| Anemia | 15 (27) | 0 (0) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 10 (18) | 2 (4) |

| Neutropenia† | 10 (18) | 2 (4) |

| Leukocytosis | 7 (13) | 0 (0) |

| Nonhematologic | ||

| Pneumonia‡ | 21§ (38) | 1 (2) |

| Asthenia∥ | 9 (16) | 2 (4) |

| Sepsis¶ | 7 (13) | 1 (2) |

| ALT increased | 6 (11) | 3 (6) |

| SAEs occurring in ≥5% of patients, n (%) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| . | Any grade . | Treatment related . |

| Hematologic | ||

| Febrile neutropenia | 8 (15) | 2 (4) |

| Nonhematologic | ||

| Pneumonia‡ | 21 (38) | 1 (2) |

| Sepsis¶ | 7 (13) | 1 (2) |

| SAEs occurring in ≥5% of patients, n (%) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| . | Any grade . | Treatment related . |

| Hematologic | ||

| Febrile neutropenia | 8 (15) | 2 (4) |

| Nonhematologic | ||

| Pneumonia‡ | 21 (38) | 1 (2) |

| Sepsis¶ | 7 (13) | 1 (2) |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

Includes aggregated terms of platelet count decrease and thrombocytopenia.

Includes aggregated terms of neutrophil count decrease and neutropenia.

Includes aggregated terms of pneumonia/fungal pneumonia/pseudomonal pneumonia/lung infection.

Three events were due to fungal infection, 1 due to bacterial infection, and in 17 with no pathogen isolated.

Includes aggregated terms of asthenia and fatigue.

Includes aggregated terms of sepsis and septic shock.

AE leading to death were reported in 18 patients (25%) in the overall population and in 15 patients (27%) treated at 125 mg. Pneumonia was the most common AE leading to death and was reported in 6 patients, all of whom were treated with 125 mg. One treatment-related death due to cerebral venous thrombosis occurred in a patient who received 150-mg dapolsertib (see the supplemental Results for details).

Efficacy

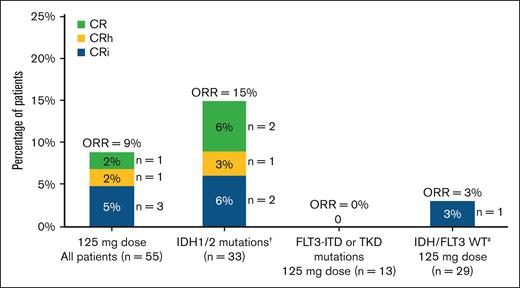

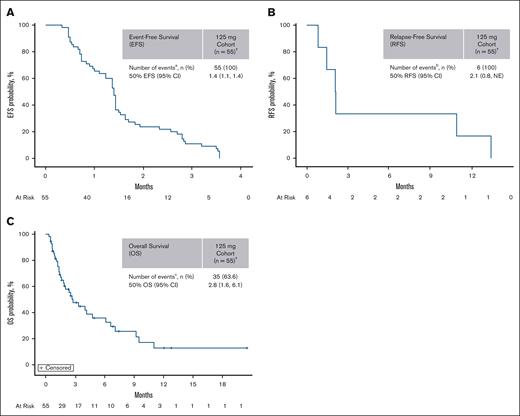

Efficacy was evaluated in the 55 patients who received 125-mg dapolsertib. Five patients experienced a response for an ORR of 9%, including 1 (2%) CR, 1 (2%) CRh, and 3 (5%) CRi (Figure 1). Partial responses or morphologic leukemia-free state were not observed. The median DoR was 2.1 months; the median time to best response was 4.5 months; the median event-free survival was 1.4 months; the median relapse-free survival was 2.1 months; and the median OS (mOS) was 2.8 months (Figure 2). One additional response (CR) was reported in a patient treated at 75 mg.

Summary of responses to dapolsertib. Overall response was defined as CR + CRh + CRi + morphologic leukemia-free state (MLFS); no partial responses or MLFS were observed. † indicates that the subset included 1 patient at 75 mg dose with CR. ‡ indicates that the patient with CRi had the following mutations: ASXL1, CUX1, DDX41, EZH2, and PRPF8.

Summary of responses to dapolsertib. Overall response was defined as CR + CRh + CRi + morphologic leukemia-free state (MLFS); no partial responses or MLFS were observed. † indicates that the subset included 1 patient at 75 mg dose with CR. ‡ indicates that the patient with CRi had the following mutations: ASXL1, CUX1, DDX41, EZH2, and PRPF8.

Dapolsertib efficacy in the 125-mg dose level. (A-C) EFS (A), RFS (B), and OS end points (C) were estimated in patients who received 125-mg dapolsertib (n = 55) using the Kaplan-Meier method. † indicates 1 patient with CRi was recorded, but the sponsor did not consider this patient as a responder because the response was achieved after 2 months of drug interruption (started at C1D10) due to an unrelated AE. aRelapsed, progressed, or died; brelapsed, treatment failed, or died; and cdied. CI, confidence interval; EFS, event-free survival; NE, not estimable; RFS, relapse-free survival.

Dapolsertib efficacy in the 125-mg dose level. (A-C) EFS (A), RFS (B), and OS end points (C) were estimated in patients who received 125-mg dapolsertib (n = 55) using the Kaplan-Meier method. † indicates 1 patient with CRi was recorded, but the sponsor did not consider this patient as a responder because the response was achieved after 2 months of drug interruption (started at C1D10) due to an unrelated AE. aRelapsed, progressed, or died; brelapsed, treatment failed, or died; and cdied. CI, confidence interval; EFS, event-free survival; NE, not estimable; RFS, relapse-free survival.

Throughout the study, after treatment of the first 48 patients (including those patients treated at 125 mg as well as other doses of 25, 50, 75, 100, and 150 mg during dose escalation), 3 responses were observed among 8 patients with IDH1/2 mutations. Of these patients, 3 were previously treated with IDH inhibitors, including the patient who achieved a CR at 75 mg (previously treated with enasidenib). Subsequently, 25 additional patients were enrolled in a cohort harboring IDH1/2 mutations, with 3 previously treated with IDH inhibitors. Only 2 additional responses (8%) were observed (1 CR and 1 CRh) in this cohort. Overall, among the 27 patients with IDH1/2 mutations and treated at 125 mg, 4 responses (15%) were observed (1 CR, 1 CRh, and 2 CRi), with 1 patient with concomitant IDH2 and NPM1 mutations having a DoR of 17.8 months. None of the responders at the 125-mg dose level had previously received an IDH inhibitor.

No responses were observed among the 13 patients with FLT3-ITD or TKD mutations treated at 125 mg. The remaining response observed at 125 mg was a CRi reported in a patient with ASXL1, CUX1, DDX41, EZH2, and PRPF8 mutations.

For all dose levels, patients with baseline and at least 1 postbaseline BM assessment available represented 56% of the overall population (n = 41), 58% of the IDH-mutated subset (n = 19), and 35% of the FLT3-mutated subset (n = 6; supplemental Table 6). Of these patients in the overall population, 19 (46%) experienced a BM blast reduction from baseline, with a median of 3 cycles (range, 1-11) to achieve maximum reduction and a median change from baseline of ˗67%. Among patients with IDH mutations, 12 (63%) experienced BM blast reduction from baseline, with a median of 3 cycles (range, 1-11) to achieve maximum reduction and a median change from baseline of ˗77%. Among those with FLT3 mutations, 1 patient (17%) experienced BM blast reduction from baseline, with 5 cycles to achieve a maximum reduction of ˗31%.

Mutation analysis

Post hoc next-generation sequencing genomic profiling was performed in 54 patients who received 125 mg with available samples. The most frequently mutated genes were FLT3-ITD (23%), DNMT3A (19%), TET2 (19%), NPM1 (16%), WT1 (16%), and TP53 (16%), whereas the most frequently mutated genes in the IDH-mutated subset were IDH2 (52%), IDH1 (43%), DNMT3A (35%), SRSF2 (35%), NPM1 (22%), and RUNX1 (22%).

In patients with SRSF2-mutated tumors, mOS was 7.0 months vs 2.7 months in patients with SRSF2-wild-type (WT) tumors (hazard ratio, 0.32; 95% confidence interval, 0.12-0.85; log-rank test P = .018). In patients with spliceosome-mutated tumors, mOS was 6.1 months vs 2.5 months in patients with spliceosome WT tumors (hazard ratio, 0.40; 95% confidence interval, 0.17-0.94; log-rank test P = .03).

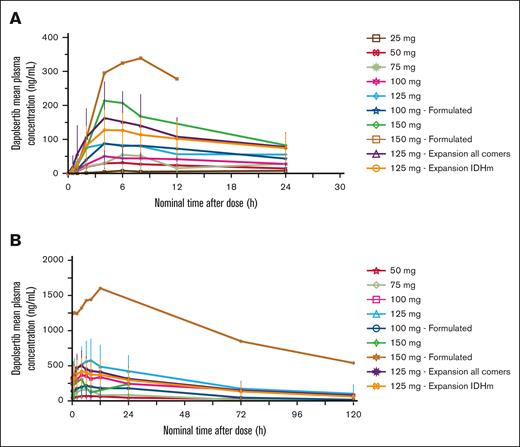

PK

Analysis of PK parameters was performed on the PK population (n = 73). The mean concentration time profiles and mean PK parameters of dapolsertib after single- and repeat-dose administration are presented in Figure 3 and Table 3, respectively. Dapolsertib was rapidly absorbed, with maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) reached ∼5 hours after dose intake. Dapolsertib exhibited a long terminal elimination half-life (t1/2) ranging from 24 to 44 hours across the 50- to 125-mg dose range. This slow elimination explains the observed accumulation between cycle 1 day 1 (C1D1) and C1D14, with mean accumulation ratio values ranging from 2.5 to 4.4 for Cmax and from 1.8 to 5.1 for area under the time-concentration curve (AUC0-24) across the 50- to 150-mg dose range. Dapolsertib displayed similar plasma PK profiles in patients who received either the formulated or nonformulated dapolsertib at 100 mg, suggesting no significant formulation impact on the PK of dapolsertib (Figure 3). In addition, dapolsertib plasma PK profiles and parameters overall were similar between IDH wild-type and IDH-mutated patients, more specifically at the 125-mg RP2D (supplemental Figure 2), suggesting that IDH mutational status had no significant impact on the PK of dapolsertib. Based on a descriptive analysis of the dose-normalized Cmax and AUC vs the dose, administration of dapolsertib resulted in a trend of a more than proportional increase of Cmax and AUC0-24 across the tested dose range (supplemental Figure 3). After single-dose dapolsertib administration at 50 to 150 mg, the mean fraction of dose excreted as unchanged drug in urine over 24 hours was 1% to 4%, and the mean renal clearance of dapolsertib was low, ranging from 0.57 to 0.87 L/h, indicating a marginal contribution of renal clearance to the elimination of dapolsertib (supplemental Table 7).

Dapolsertib mean plasma PK profiles after single- and repeat-dose administration. Mean (± standard deviation) dapolsertib plasma concentration time curves grouped by dose level from the PK population analysis set. (A) C1D1; (B) C1D14. IDHm, isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) mutated.

Dapolsertib mean plasma PK profiles after single- and repeat-dose administration. Mean (± standard deviation) dapolsertib plasma concentration time curves grouped by dose level from the PK population analysis set. (A) C1D1; (B) C1D14. IDHm, isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) mutated.

Dapolsertib mean plasma PK parameters after single and repeat dose

| Visit . | PK parameter . | Units . | Dose, mg . | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 . | 50 . | 75 . | 100 . | 125 . | 150 . | |||||||||

| Value∗ . | n . | Value∗ . | n . | Value∗ . | n . | Value∗ . | n . | Value∗ . | n . | Value∗ . | n . | |||

| C1D1 | Tmax | h | 14.04 [4.0-24.1] | 2 | 6 [4.1-6.3] | 3 | 3.98 [2.0-6.0] | 3 | 5.08 [4.0-8.0] | 6 | 4.08 [2.0-24.0] | 55 | 5.04 [4.0-8.0] | 4 |

| Cmax | ng/mL | 8.77 (29.3) 8.77 | 2 | 33.58 (33.5) 30.16 | 3 | 60.55 (88.3) 42.34 | 3 | 73.25 (50.4) 63.22 | 6 | 152.90 (53.9) 121.17 | 55 | 249.00 (26.8) 239.68 | 4 | |

| AUClast | ng × h/mL | 152.17 (43.0) 152.17 | 2 | 490.37 (24.3) 450.93 | 3 | 729.48 (116.3) 287.89 | 3 | 1016.62 (69.5) 951.59 | 6 | 1936.61 (64.2) 1760.22 | 55 | 2608.31 (47.0) 2881.54 | 4 | |

| C1D14 | Tmax | h | — | — | 6.00 [4.0-6.0] | 3 | 4.02 [3.9-6.1] | 3 | 5.89 [4.0-6.0] | 6 | 4 [0-23.4] | 42 | 4 [0.4-10.0] | 3 |

| Cmax | ng/mL | — | — | 74.32 (64.1) 55.72 | 3 | 167.08 (60.9) 132.85 | 3 | 294.25 (53.5) 295.06 | 6 | 507.18 (44.0) 501.51 | 42 | 759.36 (97.8) 473.82 | 3 | |

| AUCtau | ng × h/mL | — | — | 1330.03 (78.4) 784.1 | 3 | 2885.33 (66.7) 2175.12 | 3 | 5574.10 (52.6) 5475 | 6 | 9224.62 (50.6) 8587.13 | 38 | 15769.60 (106.3) 10021.99 | 3 | |

| AUCinf | ng × h/mL | — | — | 5876.73 (103.2) 5876.73 | 2 | 5751.94 (58.8) 4893.54 | 3 | 18255.06 (65.9) 18156.1 | 6 | 31055.94 (68.4) 24990.85 | 35 | — | — | |

| Vz/F | L | — | — | 2137.49 (30.4) 2137.49 | 2 | 1227.98 (57.3) 1465.58 | 3 | 1436.49 (69.9) 1032.98 | 6 | 969.16 (42.1) 930.15 | 37 | — | — | |

| CLss/F | L/h | — | — | 52.6 (55.0) 63.77 | 3 | 34.09 (56.0) 34.48 | 3 | 24.05 (64.7) 18.44 | 6 | 17.66 (57.5) 14.59 | 36 | 4.33 | 1 | |

| t1/2 | h | — | — | 43.58 (49.8) 43.58 | 2 | 24.39 (19.0) 23.32 | 3 | 42.96 (35.3) 41.52 | 6 | 42.64 (40.2) 42.2 | 35 | — | — | |

| RAC Cmax | — | — | 2.58 (89.4) 1.29 | 3 | 3.38 (35.3) 3.14 | 3 | 4.39 (54.8) 4.1 | 6 | 4.01 (58.5) 3.22 | 42 | 2.51 (79.7) 1.93 | 3 | ||

| RAC AUC | — | — | 3.01 (94.9) 1.49 | 3 | 4.62 (48.5) 3.71 | 3 | 5.10 (65.4) 3.2 | 5 | 4.82 (65.8) 3.89 | 34 | 1.80 (66.5) 1.8 | 2 | ||

| Visit . | PK parameter . | Units . | Dose, mg . | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 . | 50 . | 75 . | 100 . | 125 . | 150 . | |||||||||

| Value∗ . | n . | Value∗ . | n . | Value∗ . | n . | Value∗ . | n . | Value∗ . | n . | Value∗ . | n . | |||

| C1D1 | Tmax | h | 14.04 [4.0-24.1] | 2 | 6 [4.1-6.3] | 3 | 3.98 [2.0-6.0] | 3 | 5.08 [4.0-8.0] | 6 | 4.08 [2.0-24.0] | 55 | 5.04 [4.0-8.0] | 4 |

| Cmax | ng/mL | 8.77 (29.3) 8.77 | 2 | 33.58 (33.5) 30.16 | 3 | 60.55 (88.3) 42.34 | 3 | 73.25 (50.4) 63.22 | 6 | 152.90 (53.9) 121.17 | 55 | 249.00 (26.8) 239.68 | 4 | |

| AUClast | ng × h/mL | 152.17 (43.0) 152.17 | 2 | 490.37 (24.3) 450.93 | 3 | 729.48 (116.3) 287.89 | 3 | 1016.62 (69.5) 951.59 | 6 | 1936.61 (64.2) 1760.22 | 55 | 2608.31 (47.0) 2881.54 | 4 | |

| C1D14 | Tmax | h | — | — | 6.00 [4.0-6.0] | 3 | 4.02 [3.9-6.1] | 3 | 5.89 [4.0-6.0] | 6 | 4 [0-23.4] | 42 | 4 [0.4-10.0] | 3 |

| Cmax | ng/mL | — | — | 74.32 (64.1) 55.72 | 3 | 167.08 (60.9) 132.85 | 3 | 294.25 (53.5) 295.06 | 6 | 507.18 (44.0) 501.51 | 42 | 759.36 (97.8) 473.82 | 3 | |

| AUCtau | ng × h/mL | — | — | 1330.03 (78.4) 784.1 | 3 | 2885.33 (66.7) 2175.12 | 3 | 5574.10 (52.6) 5475 | 6 | 9224.62 (50.6) 8587.13 | 38 | 15769.60 (106.3) 10021.99 | 3 | |

| AUCinf | ng × h/mL | — | — | 5876.73 (103.2) 5876.73 | 2 | 5751.94 (58.8) 4893.54 | 3 | 18255.06 (65.9) 18156.1 | 6 | 31055.94 (68.4) 24990.85 | 35 | — | — | |

| Vz/F | L | — | — | 2137.49 (30.4) 2137.49 | 2 | 1227.98 (57.3) 1465.58 | 3 | 1436.49 (69.9) 1032.98 | 6 | 969.16 (42.1) 930.15 | 37 | — | — | |

| CLss/F | L/h | — | — | 52.6 (55.0) 63.77 | 3 | 34.09 (56.0) 34.48 | 3 | 24.05 (64.7) 18.44 | 6 | 17.66 (57.5) 14.59 | 36 | 4.33 | 1 | |

| t1/2 | h | — | — | 43.58 (49.8) 43.58 | 2 | 24.39 (19.0) 23.32 | 3 | 42.96 (35.3) 41.52 | 6 | 42.64 (40.2) 42.2 | 35 | — | — | |

| RAC Cmax | — | — | 2.58 (89.4) 1.29 | 3 | 3.38 (35.3) 3.14 | 3 | 4.39 (54.8) 4.1 | 6 | 4.01 (58.5) 3.22 | 42 | 2.51 (79.7) 1.93 | 3 | ||

| RAC AUC | — | — | 3.01 (94.9) 1.49 | 3 | 4.62 (48.5) 3.71 | 3 | 5.10 (65.4) 3.2 | 5 | 4.82 (65.8) 3.89 | 34 | 1.80 (66.5) 1.8 | 2 | ||

RAC AUC was calculated as AUC C1D14/AUC C1D1; RAC Cmax was calculated as Cmax C1D14/Cmax C1D1.

AUCinf, AUC from time 0 to infinity; AUClast, AUC from time 0 to the last observation; AUCtau, AUC from time 0 to time tau (the dosing interval) at steady state; CLss/F, apparent plasma clearance at steady state; RAC AUC, accumulation ratio for AUC; RAC Cmax, accumulation ratio for Cmax; Tmax, time corresponding to Cmax; Vz/F, apparent volume of distribution.

PK parameters are expressed as mean (coefficient of variation percent) median except for Tmax and t1/2 for which data are expressed as median (min, max).

pS6 inhibition as a biomarker of dapolsertib target engagement

In vitro studies in 27 AML cell lines with different genetic alterations showed a direct correlation between dapolsertib activity and levels of pS6 inhibition (supplemental Figure 4). The degree of pS6 inhibition corresponding to antileukemic effect varied in responder cells; a growth inhibition 50% of <500 nM was associated with 50% to 100% pS6 inhibition.

Baseline pS6 levels

For patients who received 125-mg dapolsertib with available samples, pharmacodynamics were monitored via pS6 expression in PB and BM (Table 4). High heterogeneity in pS6 levels between patients with AML was detected at baseline, consistent with the unselected population of patients with AML (supplemental Figure 5). In 9 of 48 evaluable patients (19%), a high pS6 level at baseline (≥15 000 for percentage of pS6-positive blast cells multiplied by the mean fluorescence intensity value) corresponded with consistent dapolsertib-mediated pS6 inhibition of ≥50%.

Inhibition of pS6 in BM and PB at 125-mg dapolsertib

| pS6 inhibition in BM, % . | pS6 inhibition in PB, % . | |

|---|---|---|

| C1D14 . | C1D14 . | C3D1 before dose . |

| — | 0 | — |

| 76 | 78 | — |

| — | 0 | — |

| 40 | 89 | — |

| 0 | 0 | — |

| — | 75 | — |

| — | 67 | — |

| — | 0 | — |

| — | 0 | — |

| — | 60 | — |

| — | 42 | — |

| — | 0 | — |

| — | 0 | 80 |

| — | 0 | 0 |

| — | 0 | — |

| — | 33 | 76 |

| — | — | 99 |

| — | 85 | 62 |

| — | 66 | — |

| — | 0 | — |

| — | 84 | — |

| — | 34 | 4 |

| — | 40 | 56 |

| — | 99 | 0 |

| — | 0 | 0 |

| — | 99 | — |

| — | 0 | — |

| — | — | — |

| — | 0 | 25 |

| — | 94 | 98 |

| — | 0 | — |

| — | 11 | 0 |

| — | 0 | — |

| — | 64 | — |

| — | — | 0 |

| — | 0 | — |

| — | 90 | — |

| — | 21 | — |

| — | 81 | 53 |

| — | 63 | — |

| — | 62 | 48 |

| — | 0 | — |

| — | 93 | — |

| — | 0 | — |

| — | 63 | — |

| — | 0 | 0 |

| pS6 inhibition in BM, % . | pS6 inhibition in PB, % . | |

|---|---|---|

| C1D14 . | C1D14 . | C3D1 before dose . |

| — | 0 | — |

| 76 | 78 | — |

| — | 0 | — |

| 40 | 89 | — |

| 0 | 0 | — |

| — | 75 | — |

| — | 67 | — |

| — | 0 | — |

| — | 0 | — |

| — | 60 | — |

| — | 42 | — |

| — | 0 | — |

| — | 0 | 80 |

| — | 0 | 0 |

| — | 0 | — |

| — | 33 | 76 |

| — | — | 99 |

| — | 85 | 62 |

| — | 66 | — |

| — | 0 | — |

| — | 84 | — |

| — | 34 | 4 |

| — | 40 | 56 |

| — | 99 | 0 |

| — | 0 | 0 |

| — | 99 | — |

| — | 0 | — |

| — | — | — |

| — | 0 | 25 |

| — | 94 | 98 |

| — | 0 | — |

| — | 11 | 0 |

| — | 0 | — |

| — | 64 | — |

| — | — | 0 |

| — | 0 | — |

| — | 90 | — |

| — | 21 | — |

| — | 81 | 53 |

| — | 63 | — |

| — | 62 | 48 |

| — | 0 | — |

| — | 93 | — |

| — | 0 | — |

| — | 63 | — |

| — | 0 | 0 |

Hyphen (—) indicates not evaluable.

Longitudinal assessment of pS6 inhibition

pS6 was longitudinally monitored in PB from patients treated with 125 mg (supplemental Figure 6). pS6 inhibition of ≥50% was observed at C1D14 in 12 of 25 evaluable patients (48%). However, among remaining patients with low or no pS6 inhibition at C1D14, five of 11 showed pS6 inhibition of ≥50% beyond the C1D14 time point (C2D14, C5D1, and C7D1). In the IDH-mutated cohort, pS6 inhibition of ≥50% was observed at C1D14 in 8 of 17 evaluable patients (47%). No correlation between pS6 inhibition and clinical response was found.

Discussion

In this phase 1/2, first-in-human study, single-agent dapolsertib demonstrated a manageable safety profile and modest clinical activity at the 125-mg RP2D.

Overall, 6 of 73 patients achieved a response, with 5 of these responses observed among the 55 patients treated at 125 mg, for an ORR at the RP2D of 9% and an mOS of 2.8 months. When looking at the different subpopulations, an initial signal was detected, with responses observed in 3 of 8 patients with IDH1/2 mutations during the dose-escalation phase and the first cohort of the dose-expansion phase. This observation prompted the exploration of dapolsertib activity in an additional cohort of patients harboring IDH1/2 mutations.

Despite the lack of direct IDH inhibition, potential biological mechanisms for the modest activity observed in the IDH-mutated setting might be found in dapolsertib’s activity as a PIM inhibitor. Indeed, IDH-mutant AML exhibits distinct biological characteristics with heightened reliance on mitochondrial function for ATP production, thus creating potential vulnerabilities to specific drugs that modulate mitochondria metabolism.24,25 Increasing evidence suggests that PIM kinases act directly on the maintenance of mitochondrial integrity and function, with their inhibition driving excessive mitochondrial fragmentation and cell death.26,27 This specific role has been also observed in IDH-mutated cancer cells, in which the disruption of the balance between mitochondrial fission and fusion mediated by PIM inhibition could trigger mitochondrial stress and bioenergetic failure, leading to eventual cell death.28

Despite the initial signal observed in the IDH patients, only 2 additional responses were observed in the additional 25 patients with IDH1/2 mutations. Furthermore, when considering BM change from baseline in patients with IDH1/2 mutations, only one-third of patients with BM postbaseline assessment had reduction of at least 50% from baseline, with a median of 3 cycles to achieve maximum reduction of blasts. Knowing the limitations of comparisons between different trials, the observed rates of response to dapolsertib as monotherapy seem to be lower than what has been observed with the specific IDH inhibitors ivosidenib and olutasidenib (used in patients with AML with IDH1 mutations) and enasidenib (used in patients with AML with IDH2 mutations). For these drugs, CR/CRh/CRi rates vary between 26% and 45%, with an mOS between 8.8 and 11.6 months.13-15

PK analyses indicated a more than dose-proportional and time-dependent PK across the evaluated dapolsertib dose ranges. Similar to the approved second-generation FLT3 inhibitors for AML, gilteritinib and quizartinib, dapolsertib was rapidly absorbed, extensively distributed to peripheral tissues, and displayed a long t1/2 suitable for QD dosing administration. In addition, similar to gilteritinib and quizartinib, marginal contribution of renal clearance was observed.

Given the long t1/2 of dapolsertib, steady-state plasma concentrations are expected after 8 to 9 days of continuous treatment. However, the 14-day-on/7-day-off dosing regimen implemented to mitigate neutropenia and hepatotoxicity risks resulted in steady-state concentrations being maintained only until day 14, after which they significantly declined during the washout period, and this pattern is repeated for each treatment cycle.

Integrated PK-biomarker-efficacy models predicted efficacious single-agent dapolsertib doses in humans to be >150 mg daily.29 Consequently, the limited activity of dapolsertib observed in this study, along with delayed clinical response and delayed BM blast infiltration reduction, may be explained by (1) intermittent dosing, which maintains dapolsertib steady-state concentrations for only 1 week per cycle; and (2) even at steady state, the 125-mg RP2D dose did not achieve the predicted efficacious plasma exposure.

In this study, among patients with FLT3-ITD or TKD mutations, none achieved any response to dapolsertib. Additionally, despite the small number of patients, the ability to reduce blast infiltration in the BM seemed very limited in this subset.

The rationale for an approach using simultaneous PIM and FLT3 inhibition was based on the observation that PIM kinases are thought to be drivers of the resistance phenotype, and their inhibition in relapsed samples seemed to restore cell sensitivity to FLT3 inhibitors and enhance their activity in various FLT3 mutations.18 Considering this mechanism of action, exploring combination regimens with other FLT3 inhibitors may elucidate the potential of the unique dual inhibition of dapolsertib against PIM/FLT3. Combinations with other FLT3 inhibitors might represent an alternative strategy to increase sensitivity to FLT3 inhibitors and overcome the acquisition of resistance, which could eventually lead to relapse rate reduction and prolonged survival in patients with AML with FLT3 mutations.

Additionally, recent studies have found that acquisition of FLT3 inhibitor resistance is a complex process and may involve the activation of several alternative signaling pathways in addition to PIM overexpression, including JAK/STAT or RAS/MEK/ERK, or the onset of additional mutations.30 Thus, although targeting any of these pathways via monotherapy is likely to be insufficient to overcome FLT3 resistance, combination of dapolsertib with other novel agents targeting these other pathways may be a promising approach for overcoming FLT3 inhibitor resistance once already established.

In this study, dapolsertib demonstrated a manageable safety profile with less frequent rates of myelotoxicity and no QTc prolongation compared with the reported safety profiles of gilteritinib and quizartinib.6,11,31 Furthermore, no cases of differentiation syndrome were observed, contrasting with specific IDH inhibitors, for which differentiation syndrome is an expected AE.32 Liver toxicity with dapolsertib was expected per the drug class, and caution is warranted, with a careful evaluation of risk/benefit and close monitoring when dapolsertib is coadministered with other drugs with potential hepatotoxicity. Although pneumonia was also observed with dapolsertib, most of these events were determined to be not related to dapolsertib. Together, the observed safety profile of dapolsertib is distinct from gilteritinib, quizartinib, and the current approved specific IDH inhibitors, offering a potential area for further research.

Genomic analyses performed on samples from patients in this study may suggest improved OS in those with SRSF2-mutated or spliceosome-mutated disease, potentially representing an avenue for further exploration of efficacy in AML subsets. Despite the limitation of a post hoc analysis, which needs to be validated in prospective trials, these findings underscore how the role of genomic profiling might inform future treatment plans and may guide more personalized approaches for treatment with dapolsertib.

The pharmacodynamic marker pS6 was identified for dapolsertib target engagement, and pS6 inhibition was observed in 50% of evaluable patients at the C1D14 time point, with long-lasting pS6 inhibition beyond this time point present in a subset of patients with clinical responses. However, no significant relationship was found between clinical response and pS6 inhibition. This conclusion should be taken with caution given the limited sample size of responding patients compared with the overall tested population.

In summary, dapolsertib is well tolerated with modest single-agent activity in patients with R/R AML. Further investigations are ongoing to identify alternative strategies to assess the clinical potential of this first-in-class PIM/FLT3 inhibitor.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all patients and their families who participated in this study as well as all members at each participating institution who participated in data collection and clinical patient care activities.

This study was supported by funding from the Menarini Group. Medical writing support was provided by Shirley Markant with The Phillips Group Oncology Communications, Inc., and was funded by the Menarini Group.

Authorship

Contribution: G.M.M., F.K.A., S.Z., A.G., T.R., and F.B. contributed to data analysis and interpretation; and all authors contributed to data interpretation, had access to primary clinical data, provided review and edits, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: G. Martinelli reports institutional research grants from Pfizer, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Novartis, ARIAD Pharmaceuticals, Astex Pharmaceuticals, AbbVie, Agios, ImmunoGen, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Incyte, Sun Pharma, Telios Pharma, Arog Pharmaceuticals, Merus, Autolus, Blueprint Medicines, GlycoMimetics, Wugen, MacroGenics, Kartos Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, MEI Pharma, and Sunesis; honoraria from and advisory roles with AbbVie, Amgen, ARIAD Pharmaceuticals, BMS, ImmunoGen, Pfizer, Agios, Takeda, and Actinium Pharmaceuticals; and travel/accommodations from AbbVie, Jazz, and Pfizer. S.M. reports research funding from Celgene (now BMS), Jazz Pharmaceuticals, and Novartis; consulting/advisory role fees from BMS, Blueprint Medicines, Celgene (now BMS), Genentech/AbbVie, Novartis, and Recordati (formerly EUSA Pharma); honoraria from Celgene (now BMS) and Recordati (formerly EUSA Pharma); and travel/accommodations from Recordati. A.S. reports consulting/advisory role fees from Incyte and Sanofi; and advisory board fees from BMS, Bayer, Eisai, Gilead, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, and Servier. S.A.S. reports research funding from Beam, Blossom Hill, Caribou, Cellectis, Daiichi Sankyo, Janssen, Kumquat Bio, Kura Oncology, Novartis, Oryzon, Schrödinger, Senti Bio, Sumitomo, Takeda, Terns, Vincerx, Vironexis, and Zentalis; consulting/advisory role fees from AbbVie, Ellipses, Kura Oncology, NKarta, Novartis, Senti Bio, Sobi, Syros, and Terns; and honoraria from GSK Ojjaara speaker bureau. S.V. reports travel/accommodations from AbbVie, Astellas, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Servier. R.B.W. reports institutional research funding from ImmunoGen/AbbVie, Jazz, Kura, and Vor biopharma; institutional preclinical research support from ImmunoGen, Janssen, and Pfizer; and consulting/data and safety monitoring board (DSMB) or advisory board fees from Wugen. A.W. reports consulting/advisory role fees from AbbVie, Astellas, and Servier; honoraria from AbbVie, Astellas, BMS/Celgene, Gilead, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Pfizer, and Servier; and travel/accommodations from AbbVie and Pfizer. G. Marconi reports research funding from AbbVie, Astellas, Pfizer, Daichii Sankyo, AstraZeneca, and Syros; consulting/advisory role fees from AbbVie, Astellas, ImmunoGen, Menarini/Stemline, Pfizer, Ryvu, and Syros; honoraria from AbbVie, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, ImmunoGen, Janssen, Menarini/Stemline, Pfizer, Ryvu, Servier, Syros, Takeda, and UK NEQAS; travel accommodations/expenses from Pfizer, AbbVie, and Jazz; and DSMB or advisory board fees from Syros, ImmunoGen, and Astellas. F.B. reports research funding from Menarini, supported in part by the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca corrente and 5 per mille), and Roche; and advisory board fees from Pfizer. T.R. reports employment, stock or stock options, and patents (granted) and patents pending with Ryvu Therapeutics. P.M. reports grants from AbbVie, Astellas, BMS/Celgene, Daiichi Sankyo, Janssen, Karyopharm, Novartis, Pfizer, and Teva; consulting/advisory role fees from Agios, Astellas, BMS/Celgene, Daiichi Sankyo, Forma Therapeutics, GlycoMimetics, and Tolero Pharmaceuticals; honoraria from AbbVie, Astellas, BMS/Celgene, Daiichi Sankyo, Incyte, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Servier, and Teva; and advisory board fees from AbbVie, Astellas, BMS/Celgene, Daiichi Sankyo, Incyte, Janssen, Karyopharm, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Servier, Syndax, and Teva. A.P., G.M.M., F.K.A., S.Z., A.G., and I.G. report employment with Menarini Group. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Giovanni Martinelli, Seràgnoli Institute, University of Bologna, Via G Massarenti 9, 40138 Bologna, Italy; email: giovanni.martinelli2@unibo.it.

References

Author notes

The data that support the results of this study may be requested for products and the relevant indications that have been authorized by the regulatory authorities in Europe/the United States (or, if not, 2 years have elapsed since the study completion). The Menarini Group will review requests individually to determine whether (1) the requests are legitimate and relevant and meet sound scientific research principles, (2) the requests are within the scope of the participants’ informed consent, and (3) the request is compliant with any applicable law and regulation and with any contractual relationship that Menarini Group and its affiliates and partners have in place with respect to the study and/or the relevant product. Before making data available, requestors will be required to agree in writing to certain obligations, including without limitation, compliance with applicable privacy and other laws and regulations. Proposals should be directed to medicalinformation@menarinistemline.com.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.