Key Points

The French STIM1 study significantly contributes to understanding treatment-free remission in CML, clarifying its long-term survival implications.

Very long-term monitoring of patients who have discontinued treatment is necessary over such extended follow-up periods.

Visual Abstract

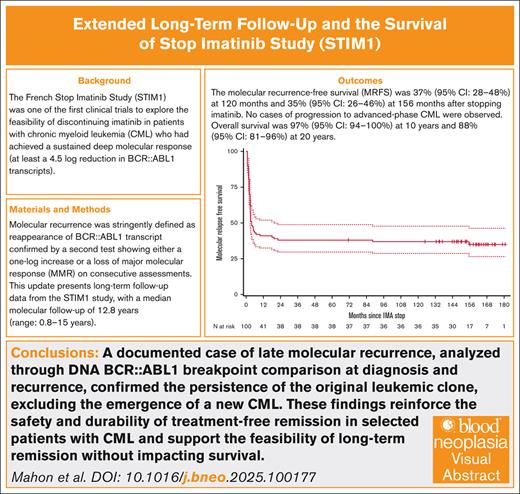

The French Stop Imatinib study (STIM1) was one of the first trials to explore the possibility of discontinuing imatinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) who had achieved a sustained molecular response (at least a 4.5-log reduction). The stringent criteria for molecular recurrence (MRec) were defined as BCR::ABL1 transcript positivity confirmed by a second test showing either a 1-log increase or loss of major molecular response across consecutive assessments. This comprehensive update presents long-term follow-up data from the STIM1 study, with a median molecular follow-up of 12.8 years (range, 0.8-15). Results showed a molecular recurrence-free survival rate of 37% (95% confidence interval [CI], 28-48) at 120 months, and 35% (95% CI, 26-46) at 156 months after imatinib discontinuation. Importantly, no patients experienced CML progression during the follow-up. Overall survival rates were 97% (95% CI, 94-100) at 10 years and 88% (95% CI, 81-96) at 20 years. A case of late MRec, confirmed through DNA BCR::ABL1 breakpoint analysis and comparison at diagnosis and recurrence, indicated the persistence of the original disease rather than the onset of new CML. This study offers valuable insights into the safety and feasibility of imatinib discontinuation for patients with CML, supporting long-term remission while maintaining survival. This study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov as #NCT00478985.

Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a model of success in modern cancer therapy, with a life expectancy close to that of the general population.1 The tyrosine kinase activity of the BCR::ABL1 protein, translated from BCR::ABL1 gene, the marker and the driver of the disease was first targeted in humans 25 years ago with the discovery of oral tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI).2 Imatinib, a first-generation TKI, has demonstrated remarkable efficacy in achieving deep molecular responses (DMR) in patients with CML.3,4 The French Stop Imatinib study (STIM), initially conducted to explore the possibility of treatment discontinuation in patients with undetectable minimal residual disease, has previously reported pioneer results regarding the achievement and maintenance of treatment-free remission (TFR).5,6 Based on our historical experience with stopping interferon (IFN) in patients with CML in remission, we defined criteria for stopping TKIs, introducing the concept of a sustained DMR.7 At that time, molecular quantification of BCR::ABL1 messenger RNA was not yet fully standardized, but undetectable minimal residual disease corresponded approximately to an MR4.5-log reduction.8 Besides the question of which factors can predict TFR, its impact on survival is of paramount importance. In the current report, we update these results with very long follow-up data.8 As the landscape of CML treatment evolves, understanding the long-term consequences of discontinuation on patient survival is important.

Patients and methods

Patients were included according to the criteria already reported.6 From July 2007 to December 2009, 100 patients with CML were included, of whom 50 were previously treated with IFN-α because historically the first step of imatinib indication was for patients who were IFN-resistant. The historically stringent criteria were undetectable minimal residual disease sustained for at least 2 years, at that time when we started the study the 4.5-log reduction was not standardized on the International Scale.6 DMR is now considered when the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) sensitivity achieves at least 4-log reduction using International Scale.

Molecular recurrence (MRec) was defined as positivity of the BCR::ABL1 transcript in a reverse transcriptase-quantitative PCR assay confirmed by a second analysis point with a 1-log increase relative to the first analysis point on 2 consecutive assessments or loss of major molecular response (MMR).6

Written informed consent was obtained for all patients. The ethics committee, in agreement with the French public health code, approved the protocol. For the patient with late recurrence, BCR::ABL1 genomic breakpoint was sequenced at diagnosis and at MRec. Library was prepared using the protocol Illumina: Nextera Rapid Capture Custom Enrichment, and was then sequenced on MiSeq using MiSeq reagent kit v3, 2 × 250 cycles. BCR::ABL1 breakpoints were determined by bioinformatics processing in NextGene Software using a structural variant detection workflow (supplemental Data).9 For the recurrent case, BCR::ABL1 transcripts were reanalyzed. Three additional different molecular tools were used: reverse transcriptase-digital droplet PCR (ddPCR) using the kit QXDx BCR-ABL %IS, reverse transcriptase-quantitative PCR using a more efficient reverse transcriptase (RT) (Vilo4) and digital PCR on genomic DNA based on BCR::ABL1 fusion junction.10

Statistical methods

The overall survival (OS) was defined as death from any cause since diagnosis, whereas alive patients were censored at their last follow-up. In the event of loss to follow-up, investigators were asked to check French death registers (https://deces.matchid.io or https://arbre.app/insee) to see whether their patients had been declared dead and, if so, to indicate the date of death. The molecular monitoring was performed as previously reported, and every 3 months after 2 years.6

Molecular recurrence-free survival (MRFS) was defined as time from imatinib cessation to relapse or death events (whichever happened first) and censoring for alive patients at their last molecular follow-up. The Kaplan-Meier method was used for graphic illustrations.

Molecular recurrence-free remission was measured as the relapse events incidence since the time from imatinib cessation with death without relapse as a competing risk. The cumulative incidence function was used for graphic illustrations.

Results

From July 2007 to December 2009, 100 patients were included, of whom 50 were previously treated with IFN-α. According to the previous analysis and those performed by other groups, there was no difference between patients who received IFN and those who were treated with TKI, and preliminary results of the STIM1 study were reported in 2010.6 The median durations of imatinib treatment in the IFN-α group were 62 months (mean, 63 months), and 57 months (mean, 62 months) for patients without IFN-α.

It is important to remember that the definition of relapse or recurrence in this study was more stringent compared with other studies, as the STIM1 study was the first trial to propose TKI discontinuation.

At the time of this 2023 analysis, the median molecular follow-up after imatinib discontinuation was 153 months (range, 9-180). MRFS was 43% (95% confidence interval [CI], 33-52) at 6 months, 40% (95% CI, 30-49) at 18 months, 37% (95% CI, 28-48) at 120 months, and 35% (95% CI, 26-46) at 156 months. Compared with the 2017 analysis, 1 additional MRec was observed at 90 months. This patient had a molecular relapse without loss of hematological response, detected during systematic follow-up. Mutation testing was negative at the time of loss of MMR. No cytogenetic documentation was available. A second rapid response was achieved after resuming treatment. The patient passed away on 22 April 2022, 7 years later, while in DMR. The death was unrelated (postoperative complications following femoral neck fracture).

The median follow-up was 153 months for the 38 patients who remained in molecular response without treatment, and 154 months for the 62 patients who re-initiated treatment. The cumulative incidence of MRec, accounting for competing events (including the death of 1 patient in DMR), is presented in Figure 1B. The median age of the STIM1 cohort was 72 years at the last follow-up. With a median follow-up of 12.75 years, none of the patients experienced CML progression.

Follow-up after imatinib discontinuation (median 12.8 [0.8-15] years). (A) MRFS: 37% (95% CI, 28-48) at 120 months and 35% (95% CI, 26-46) at 156 months. (B) Cumulative incidence of MRec. One additional MRec appeared at 90 months of follow-up. (C) The OS rate was 97% (95% CI, 94-100) at 10 years, and 88% (95% CI, 81-96) at 20 years. IMA, imatinib

Follow-up after imatinib discontinuation (median 12.8 [0.8-15] years). (A) MRFS: 37% (95% CI, 28-48) at 120 months and 35% (95% CI, 26-46) at 156 months. (B) Cumulative incidence of MRec. One additional MRec appeared at 90 months of follow-up. (C) The OS rate was 97% (95% CI, 94-100) at 10 years, and 88% (95% CI, 81-96) at 20 years. IMA, imatinib

Fifteen patients died: 3 before molecular relapse (due to cardiovascular and other causes), and 12 from causes unrelated to CML (1 accident, 4 secondary cancers, 3 cardiovascular diseases, and 4 other diseases; Table 1).

Patient Characteristics

| Patients Characteristics . | 2023 . | 2017 analysis8 . |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, y, median (min-max) | 53 (24-74) | |

| Age at TKI discontinuation, y, median (min-max) | 60 (29-80) | |

| Age at last follow-up, y, median (min-max) | 72 (40-93) | – |

| Follow-up, overall, mo, median (min-max) | 153.3 (9.7-180.4) | 77 (9-95) |

| Follow-up alive patients, mo, median (min-max), | 157.5 (66.5-180.4) | 80 (55-93) |

| Lost to sight patients | 13 | 3 |

| MRecs | 62 | 61 |

| Non CML-related deaths | 12 | 4 |

| Death before MRec | 3 | 1 |

| Age at death, y, median (min-max) | 77 (49-85) | – |

| Patients Characteristics . | 2023 . | 2017 analysis8 . |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, y, median (min-max) | 53 (24-74) | |

| Age at TKI discontinuation, y, median (min-max) | 60 (29-80) | |

| Age at last follow-up, y, median (min-max) | 72 (40-93) | – |

| Follow-up, overall, mo, median (min-max) | 153.3 (9.7-180.4) | 77 (9-95) |

| Follow-up alive patients, mo, median (min-max), | 157.5 (66.5-180.4) | 80 (55-93) |

| Lost to sight patients | 13 | 3 |

| MRecs | 62 | 61 |

| Non CML-related deaths | 12 | 4 |

| Death before MRec | 3 | 1 |

| Age at death, y, median (min-max) | 77 (49-85) | – |

max, maximum; min, minimum.

It is not possible to compare the STIM1 cohort with other studies of patients treated with TKIs with such long follow-up. As an indicator, according to the long-term outcomes of imatinib treatment for CML, the estimated OS rate at 10 years was 83.3%.11 In contrast, in STIM1, the OS rate was 97% (95% CI, 94-100) at 10 years and 88% (95% CI, 81-96) at 20 years (Figure 1C).

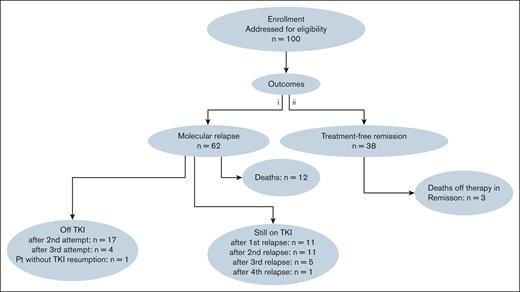

The treatment rechallenge was as follows: 17 patients discontinued TKI therapy for a second TFR attempt, among them, 4 patients subsequently attempted a third TFR. Eleven patients remained on TKI after their first relapse, 11 after their second relapse, 5 after their third relapse, and 1 after a fourth relapse. One patient did not resume TKI therapy after relapse (Figure 2).

The CONSORT diagram of the 100 patients included in the STIM study. Pt, patient.

The CONSORT diagram of the 100 patients included in the STIM study. Pt, patient.

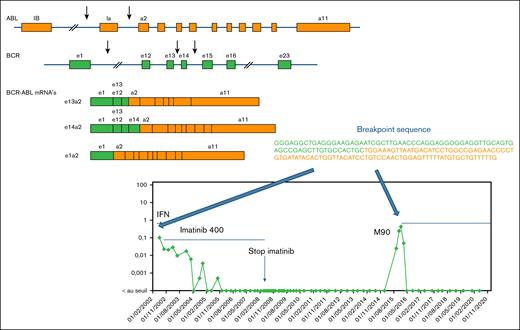

Among the 38 patients in TFR, residual disease was detected at least once during follow-up without loss of molecular response. Five patients experienced MRec later than 6 months after imatinib discontinuation at 7, 18, 20, 22, and 90 months. Sequencing of the BCR::ABL1 fusion junction at diagnosis and recurrence in the latest relapsed patient confirmed the same sequence, proving it was the same leukemic clone Fig. 3.

Late MRec. For the patient with the MRec at month 90, BCR::ABL1 breakpoints were sequenced at both diagnosis and MRec to check if it was the same disease. DNA was sent to the Institute of Hematology and Blood Transfusion, Department of Molecular Genetics, Prague, Czech Republic. The library was prepared using the Illumina Nextera Rapid Capture Custom Enrichment protocol. For the enrichment of sequences covering the BCR::ABL1 breakpoint, a custom probe set developed by Thomas Ernst and colleagues from Jena was used. This panel consists of 4608 probes, targeting both the BCR gene region (23522352-23660424) and the ABL gene region (133589068-133763262). The cumulative target length in this setting is 312 268 bp. The library was quantified using Quant-iT PicoGreen, and its quality was controlled using an Agilent Technologies 2100 Bioanalyzer with a DNA 1000 chip. The library was then sequenced on a MiSeq system using the MiSeq reagent kit v3 with 2 × 250 cycles. The BCR::ABL1 breakpoints were determined by bioinformatics processing using NextGene Software in a structural variant detection workflow. The sequence of the breakpoint from the diagnostic sample was strictly similar as compared with the sample from the MRec sample.

Late MRec. For the patient with the MRec at month 90, BCR::ABL1 breakpoints were sequenced at both diagnosis and MRec to check if it was the same disease. DNA was sent to the Institute of Hematology and Blood Transfusion, Department of Molecular Genetics, Prague, Czech Republic. The library was prepared using the Illumina Nextera Rapid Capture Custom Enrichment protocol. For the enrichment of sequences covering the BCR::ABL1 breakpoint, a custom probe set developed by Thomas Ernst and colleagues from Jena was used. This panel consists of 4608 probes, targeting both the BCR gene region (23522352-23660424) and the ABL gene region (133589068-133763262). The cumulative target length in this setting is 312 268 bp. The library was quantified using Quant-iT PicoGreen, and its quality was controlled using an Agilent Technologies 2100 Bioanalyzer with a DNA 1000 chip. The library was then sequenced on a MiSeq system using the MiSeq reagent kit v3 with 2 × 250 cycles. The BCR::ABL1 breakpoints were determined by bioinformatics processing using NextGene Software in a structural variant detection workflow. The sequence of the breakpoint from the diagnostic sample was strictly similar as compared with the sample from the MRec sample.

Although BCR::ABL1 transcripts were undetectable for almost 9 years, additional molecular assays, especially ddPCR on genomic DNA, revealed persistent CML cells—suggesting that leukemic stem cells (LSC) may survive for many years after stopping treatment.

Discussion

The STIM1 trial provides the longest follow-up data to date on TFR after imatinib discontinuation in CML. Approximately 35% to 37% of patients maintained MRFS up to 13 years after stopping treatment, demonstrating the feasibility of durable remission. To our knowledge, this is the longest remission period ever reported after TKI discontinuation, and it confirms the potential for long-term disease control in a subset of patients.

Importantly, the safety profile over this extended follow-up period is excellent. No patients experienced disease progression, and OS rates remained high—97% at 10 years, and 88% at 20 years. These findings further support the long-term safety of TKI discontinuation in appropriately selected patients.

A notable case of very late MRec was observed nearly 9 years after treatment cessation. DNA BCR::ABL1 breakpoint analysis confirmed the reactivation of the original leukemic clone, ruling out the development of a new malignancy. This observation highlights the persistence of the original leukemic clone and supports the hypothesis that LSC can remain dormant for many years. It also reinforces the need for extended molecular surveillance, even beyond the commonly accepted monitoring period, because relapse can occur long after achieving deep and sustained remission.

Since the first proposals of TKI discontinuation nearly 2 decades ago, molecular monitoring techniques have significantly evolved. In particular, PCR sensitivity has improved, and novel digital technologies, such as ddPCR, now allow more accurate detection of minimal residual disease. In parallel, the definitions of molecular relapse have been refined. Although the STIM1 study retained its original, more stringent criteria for relapse to ensure consistency across time, we addressed the evolving definitions and current international consensus—now centered on the loss of MMR—in the discussion section of the article.

Despite sustained TFR in many patients, persistent low-level residual disease remains detectable in a significant proportion, underscoring the complexity of achieving true eradication of leukemic cells. This biological challenge continues to be the focus of active research, particularly with respect to the nature, origin, and long-term behavior of LSC.

This update, which emphasizes long-term survival and molecular outcomes, provides a critical reference for clinicians evaluating the feasibility and safety of TKI discontinuation. One of the key messages is that lifelong molecular monitoring should be considered to ensure early detection of relapse and prompt therapeutic intervention, if necessary.12

The French STIM1 study remains a cornerstone in the understanding of TFR in CML. This long-term follow-up strengthens its legacy and contributes to the evolving debate on the definition of cure in leukemia. The concept of an “operational cure,” as originally proposed by John Goldman, remains highly relevant today, reflecting the delicate balance between treatment discontinuation, sustained remission, and the biological persistence of disease.13

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Fanny Robbesyn for monitoring the clinical trial. They thank the French Ministry of Health (Programme Hospitalier de Recherche 2006 grant); the Institut National du Cancer; Jan Zuna and Katerina Machova Polacova, from Institute of Hematology and Blood Transfusion, Department of Molecular Genetics, for the determination of transcript breakpoint; Thomas Ernst for sharing the panel design; and Marina Migeon, Claudine Chollet, and Lisa Boureau for the quantification of BCR::ABL1 transcript, especially on genomic DNA and RNA by digital PCR for the late molecular case.

Authorship

Contribution: P.R., D.R., and F.-X.M. were responsible for conception and design; F.-X.M. was responsible for financial support and administrative support; S.D., G.E., and F.-X.M. performed and analyzed the molecular biology; D.R., F.N., F.R.-H., V.D., M.-P.N., J.-C.I., B.V., E.C., P.R., G.E., and F.-X.M. were responsible for provision of study materials or patients’ assembly of data; G.E., S.D., F.-X.M., and K.M.P. were responsible for data analysis and interpretation; F.-X.M. was responsible for writing of the manuscript; and all authors were responsible for final approval of the manuscript and were accountable for all aspects of the work.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: G.E. is a speaker for Incyte and Novartis. S.D. is a speaker for Incyte and Novartis. D.R. is a consultant for Novartis Pharma; a speaker for Novartis and Incyte Biosciences; and board entity for Novartis Pharma, Incyte biosciences, GSK, and Ascentage Pharma. F.R.-H. is a speaker for Incyte and Novartis. F.N. is a consultant for Sun Pharma Ltd, Novartis Pharma, and Kumquat science; a speaker for Novartis and Incyte Biosciences; board entity for Novartis Pharma, Incyte biosciences, GSK, and Ascentage Pharma; and has received institutional grants from Novartis Pharma and Incyte Biosciences Europe. P.R. is speaker for Incyte Biosciences and Amgen; and a consultant for Novartis Pharma and Amgen. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: François-Xavier Mahon, Institut Bergonié, Bordeaux, 229 cours de l'Argonne 33076, Bordeaux cedex, France; email: francois-xavier.mahon@u-bordeaux.fr.

References

Author notes

Data presented in the study comprise an update of the STIM trial already reported preliminarily in https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70233-3 and in https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.68.2914.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![Follow-up after imatinib discontinuation (median 12.8 [0.8-15] years). (A) MRFS: 37% (95% CI, 28-48) at 120 months and 35% (95% CI, 26-46) at 156 months. (B) Cumulative incidence of MRec. One additional MRec appeared at 90 months of follow-up. (C) The OS rate was 97% (95% CI, 94-100) at 10 years, and 88% (95% CI, 81-96) at 20 years. IMA, imatinib](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodneoplasia/3/1/10.1016_j.bneo.2025.100177/1/m_bneo_neo-2025-000603-gr1.jpeg?Expires=1770722028&Signature=0k5X6~3Jml5CcHT0qyVcr3sOXWI8TuGPMmtX-A0pFqWGkIo4Y6oVb1iGbYNJs8RP8tdtGeL14JX4uJqkdi9K-HiJ7nGatyxiCE-zV0AJGaVEz58g4RyHulTIkU-v4PAPsr~jXS-0vNryJ9hhK-k7teWQ5Z7ZDqZs5d7XgF7b1b-wyJ~tvnZTgjrNQJZpwsi9ynbQ7PMu~LH9HOZNGb532QpWUbcFmI8EDMX2iV9cwjDJlbngxrc6z0IATgqO7MhA0jpnCveGclg7YPTKYKpzrzsjPcWwuHp4OXUupWO9BHqhXsVInXq4GDtTTqw1mWmtw2aCeHjyhZSTKq4BE~a5Dw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)