Key Points

Ibrutinib administration in combination with tisagenlecleucel was feasible and well tolerated by patients.

Administration of ibrutinib before apheresis may reduce the proportion of senescent T cells in the final manufactured product.

Visual Abstract

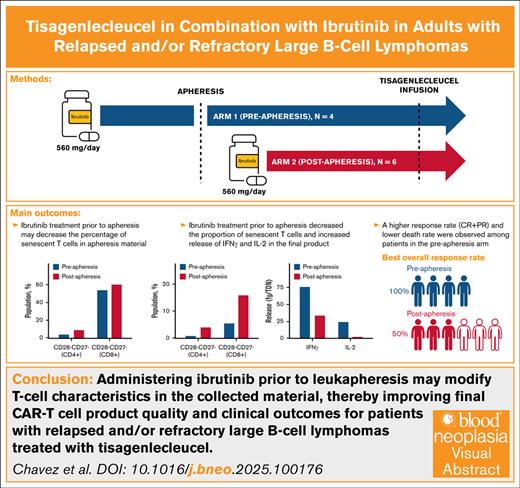

The mechanisms underlying chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell failure are not fully understood; however, T-cell differentiation and presence of an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment are thought to contribute. Ibrutinib, a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor, has been shown to modify both T-cell phenotype and tumor microenvironment. Preliminary data suggest that combining ibrutinib with tisagenlecleucel may improve efficacy of CAR T-cell therapy; however, it is unknown whether the timing of ibrutinib treatment affects clinical outcomes. This phase 1b exploratory study assessed tisagenlecleucel in combination with ibrutinib for safety, efficacy, and feasibility in adult patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL). Ibrutinib (560 mg/d) was started ≥21 days before apheresis (preapheresis arm, n = 4) or after apheresis for ≥21 days before tisagenlecleucel infusion (postapheresis arm, n = 6). Both arms received ibrutinib continuously thereafter for up to 24 months after infusion. As of study termination (1 November 2021), 10 patients were treated and underwent posttisagenlecleucel response assessment. Final product manufactured from patients in the preapheresis arm had higher interferon gamma and interleukin-2 release and a reduction in senescent T cells. Fewer patients in the preapheresis arm vs the postapheresis arm experienced cytokine release syndrome (1/4 vs 5/6) or death (1/4 vs 4/6). Although increased tisagenlecleucel expansion was observed in the postapheresis arm, a higher response rate was observed in the preapheresis arm (4/4 vs 3/6). Altogether, these findings suggest administering ibrutinib before leukapheresis may modify T-cell characteristics in the collected material, thereby improving final CAR T-cell product quality and clinical outcomes for patients with R/R LBLC treated with tisagenlecleucel. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT03876028.

Introduction

Large B-cell lymphomas (LBCL) are aggressive B-cell malignancies, with diffuse LBCL comprising ∼25% of all mature B-cell neoplasms.1 Although LBCL subtypes are heterogeneous, with varying outcomes and prognoses, advances in treatment and disease understanding have increased the 5-year relative survival rate to 64.6%.2 Despite ongoing improvements in disease management, 30% to 40% of patients with LBCL will relapse and 10% are refractory to first-line treatment.2-4 The prognosis of patients who relapse or are refractory to second or later-line chemotherapy is poor, with median overall survival (OS) of ∼6 months.5 These findings highlight the need for alternative treatment options for patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) LBCL, especially those who have received multiple lines of therapy.

CD19-directed chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies have been shown to be safe and effective in patients with R/R B-cell malignancies and are approved for use in patients with R/R LBCL in the second (axicabtagene ciloleucel, lisocabtagene maraleucel) and third-line or later settings (axicabtagene ciloleucel, lisocabtagene maraleucel, tisagenlecleucel).6-8 Despite higher response rates for CAR T-cell therapy (52%-82%9-11) than for salvage chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplant, the median progression-free survival (PFS) is only ∼3 to 6 months for all patients who had received CAR T-cell infusion, regardless of CAR T-cell product used.9,10,12

Our understanding of the exact mechanisms of failure of, or relapse after, CAR T-cell therapy is evolving. In addition to target antigen loss, evidence suggests that changes in T-cell expansion ex vivo and in vivo, related, in part, to preinfusion T-cell differentiation status, may affect product characteristics and efficacy; in addition, an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment may hinder the cytotoxic effects, expansion, and persistence of CAR T cells.13-16 These observations suggest a potential benefit of using an agent capable of modulating the tumor-associated immunosuppressive environment and maintaining a less-differentiated T-cell phenotype to support CAR T-cell efficacy.13,14

Ibrutinib is a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor that inhibits B-cell receptor signaling. Ibrutinib is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency for treating patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)/small lymphocytic lymphoma and Waldenström macroglobulinemia, as well as for previously treated chronic graft-versus-host disease in the United States and R/R mantle cell lymphoma in Europe.17,18 Based on preclinical studies using samples from patients with CLL and mantle cell lymphoma as well as correlative studies in a small number of patients with CLL, administration of ibrutinib with tisagenlecleucel is predicted to potentiate the expansion and prolong the persistence of the CAR T cells, leading to increased efficacy of tisagenlecleucel.19-21 Furthermore, combining ibrutinib with tisagenlecleucel may decrease the severity of cytokine release syndrome (CRS), a primary adverse event (AE) associated with CAR T-cell therapy.22 Although preliminary data suggest that combining ibrutinib with tisagenlecleucel may improve the efficacy of CAR T-cell therapy, it is unknown whether the timing of ibrutinib treatment (ie, before apheresis vs after apheresis) affects clinical outcomes. Here, we report the safety, tolerability, cellular kinetics, and preliminary efficacy of ibrutinib before, and concurrent with, tisagenlecleucel in patients with R/R LBCL.

Methods

Study design

This was a phase 1b, multicenter, open-label, nonrandomized exploratory study of up to 40 patients aged ≥18 years with confirmed LBCL (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03876028). Key eligibility criteria included ≥2 lines of previous systemic therapy (including an anti-CD20 and anthracycline-based chemotherapy); progression/relapse after, or ineligibility/not consenting for, autologous stem cell transplant; and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) of 0 or 1 at screening. Key exclusion criteria included diagnoses of Richter transformation, Burkitt lymphoma, and primary LBCL of the central nervous system (CNS). Patients with previous anti-CD19–directed therapy, gene therapy, adoptive T-cell therapy, allogeneic stem cell transplant, or ibrutinib therapy within the 30 days before screening were excluded. Patients with active CNS involvement were excluded, except if the CNS involvement had been effectively treated >4 weeks before enrollment. The study design, protocol, and amendments were reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards or independent ethics committees at study sites and by health authorities before implementation. All study participants provided written informed consent.

Treatment

The study enrolled patients into 2 parallel arms (supplemental Figure 1), each receiving a single infusion of tisagenlecleucel (0.6 × 108 to 6.0 × 108 CAR+ T cells) preceded and followed by daily ibrutinib administration (560 mg). In arm 1 (“preapheresis”), ibrutinib was administered for ≥21 days before apheresis and for ≥21 days after apheresis until tisagenlecleucel infusion. In arm 2 (“postapheresis”), ibrutinib was initiated after the patient’s leukapheresis product was accepted for manufacture and continued for ≥21 days until tisagenlecleucel infusion. Patients in both arms received ibrutinib continuously through lymphodepletion, CAR T-cell infusion, and postinfusion follow-up. Ibrutinib was discontinued in patients who were in complete response (CR) at the month-12 evaluation after tisagenlecleucel infusion. For all other patients, ibrutinib was continued daily through the month-24 evaluation in the absence of disease progression or meeting any other criteria for treatment discontinuation. Bridging chemotherapy was not given concurrently with ibrutinib in either arm unless patients were unable to achieve sufficient disease control to allow leukapheresis and infusion. Patient enrollment into the 2 arms was done sequentially.

Study objectives and end points

The primary end point was to assess the safety and tolerability of tisagenlecleucel in combination with ibrutinib through determining the incidence and severity of AEs and serious AEs (SAEs), changes in laboratory parameters, and ibrutinib dose modifications after tisagenlecleucel infusion. Secondary end points included postbaseline response rate at 3 months and 6 months, best overall response rate (ORR; CR plus partial response [PR]) from randomization/start of treatment, duration of response (DOR) in patients with a best response of CR, PFS from randomization/start of treatment, OS, cellular kinetics, and cellular and humoral immunogenicity. Exploratory end points to be used for the generation of new scientific hypotheses included assessing molecular characteristics and composition of leukapheresis material; final product; and peripheral blood including T-cell and B-cell populations, markers of exhaustion, soluble immune factors, and pharmacokinetic parameters.

Cellular kinetics and immunogenicity

In vivo cellular kinetics (ie, CAR transgene levels) in the peripheral blood and tissues were determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). The effect of ibrutinib on tisagenlecleucel cellular kinetics was characterized using various pharmacokinetic parameters: maximal expansion of CAR transgene in vivo (Cmax), time to maximal expansion (Tmax), area under the curve, last quantifiable CAR transgene (Clast), time to last quantifiable CAR transgene levels in the peripheral blood (Tlast), and apparent half-life of CAR transgene in the peripheral blood (T1/2). Preexisting and treatment-induced cellular immunogenicity (presence of T lymphocytes activated by the tisagenlecleucel protein) and humoral immunogenicity (anti-murine CAR19 [mCAR19] titers) against tisagenlecleucel were assessed by interferon gamma (IFN-γ) staining and/or flow cytometry, respectively. A patient was defined as positive for tisagenlecleucel treatment-induced or -boosted anti-mCAR19 antibodies if the anti-mCAR19 antibody median fluorescence intensity at any time after infusion was at least 2.28-fold higher (for samples analyzed on or before 5 May 2021) or 2.38-fold higher (for samples analyzed on or after 6 May 2021) than preinfusion levels for patients whose baseline status was positive (treatment-boosted); if the baseline status was negative, any positive result after baseline was interpreted as treatment induced.

Flow cytometry and cell viability

Multiparameter flow cytometry was used for leukapheresis and final product characterization to evaluate T-cell phenotypes and CD4/CD8 status. Total number of CAR+ T cells available for dosing was calculated based on T-cell surface CAR expression (as determined by the flow cytometry assay used for final product release) and total viable nucleated cell number (based on NC200 measurement and the total cell suspension volume available for final product formulation). Annexin-V binding by flow cytometry was evaluated in conjunction with cell surface markers and live/dead dye to identify apoptotic, necrotic, and viable fractions within the CD3+ T-cell population. A separate flow cytometry assay was used to evaluate T-cell phenotypes in postinfusion samples. Viable singlet mononuclear cells were identified, followed by gating of the CAR+ and CAR−CD3+ T-cell populations and further subsetting into CD4+ and CD8+ fractions. Memory phenotypes were identified with CD45RA, CD45RO, CCR7, CD27, and CD28. Due to low numbers of CAR+ cells after infusion, immunophenotyping of downstream memory subsets is reported for CAR− cells.

Statistical methods

Up to a total of 20 patients were planned to be enrolled in each schedule group in the efficacy analysis set, with a 0.4 probability of observing at least 1 rare event that has a 2.5% chance of occurring, and 0.64 probability for observing at least 1 rare event that has a 5% chance of occurring. Data were summarized using descriptive statistics. Median DOR, PFS, and OS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Due to the small sample size, no formal comparative statistical analyses were completed. Descriptive statistics for cellular kinetics parameters were estimated from individual concentration-vs-time profiles using a noncompartmental approach with the modeling program Phoenix (Pharsight, Mountain View, CA).

Results

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics

Between 11 June 2019 and study termination on 1 November 2021, a total of 10 patients were treated with ibrutinib and received infusion with tisagenlecleucel at 2 treatment centers. Three patients in the preapheresis arm (75%) and 1 patient in the postapheresis arm (17%) completed the study follow-up period and entered the 15-year long-term follow-up protocol. The remaining 6 patients (1 patient in the preapheresis arm [25%], 5 patients in the postapheresis arm [83%]) discontinued the study during follow-up due to death (1 patient in the preapheresis arm [25%], 4 patients in the postapheresis arm [67%]) or progressive disease (1 patient in the postapheresis arm [17%]). The study was prematurely concluded after the safety/schedule selection phase for reasons unrelated to safety or lack of efficacy. The therapeutic landscape for R/R LBCL was rapidly changing during the time of study conduct and, in this context, the sponsor made the decision to deprioritize the study, leading to its early termination. The enrichment phase of the study was, therefore, not enrolled. The median age of all patients was 61.0 years (range, 32-76). In the preapheresis and postapheresis arms, median age was 59 and 64 years, respectively. Most patients were male (n = 8, 80%) and White (n = 9, 90%; 7/9 were non-Hispanic). Most patients (n = 8, 80%) had stage III or stage IV LBCL at the time of initial diagnosis and at the time of study entry; all patients with stage IV LBCL (n = 5) were in the postapheresis arm. Bone marrow involvement was observed in 1 patient (10%) in the postapheresis arm at the time of study entry. No patient in the preapheresis arm had extralymphatic involvement compared with 4 patients (67%) in the postapheresis arm (Table 1). Germinal center B-cell type comprised most (n = 6, 60%) of lymphoma subtypes at study entry, followed by activated B-cell type (n = 3, 30%). Median time from initial diagnosis to tisagenlecleucel infusion was 18.7 months (50.7 months vs 18.4 months in the preapheresis and postapheresis arms, respectively). Most patients (n = 8, 80%) received 2 to 3 previous lines of therapy; 2 patients in the preapheresis arm (50%) received 5 previous lines of therapy (Table 1). Half of all patients (n = 5, 50%) had elevated lactate dehydrogenase levels at study entry. Two patients (33%) in the postapheresis arm received at least 1 bridging chemotherapy regimen, which included dexamethasone (n = 2, 33.3%), gemcitabine (n = 1, 16.7%), oxaliplatin (n = 1, 16.7%), and rituximab (n = 1, 16.7%). All patients (n = 10, 100%) received lymphodepleting chemotherapy before tisagenlecleucel infusion (preapheresis arm: 25% fludarabine/cyclophosphamide [n = 1], 75% bendamustine [n = 3]; postapheresis arm: 83% fludarabine/cyclophosphamide [n = 5], 17% bendamustine [n = 1]). One patient in the preapheresis arm (25%) had received ibrutinib before study entry.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics (safety set)

| Demographic characteristics . | Tisagenlecleucel + ibrutinib, preapheresis N = 4 . | Tisagenlecleucel + ibrutinib, postapheresis N = 6 . | All patients N = 10 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median, y | 59 | 64 | 61 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 0 | 2 (33) | 2 (20) |

| ECOG PS at screening, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 3 (75) | 3 (50) | 6 (60) |

| 1 | 1 (25) | 3 (50) | 4 (40) |

| ECOG PS at baseline, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 3 (75) | 1 (17) | 4 (40) |

| 1 | 1 (25) | 4 (67) | 5 (50) |

| 2 | 0 | 1 (17) | 1 (10) |

| LDH > ULN at study entry, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 2 (50) | 3 (50) | 5 (50) |

| No | 2 (50) | 3 (50) | 5 (50) |

| Stage at time of study entry, n (%) | |||

| Stage I | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Stage II | 2 (50) | 0 | 2 (20) |

| Stage III | 2 (50) | 0 | 2 (20) |

| Stage IV | 0 | 6 (100) | 6 (60) |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bone marrow involved at study entry, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 0 | 1 (17) | 1 (10) |

| No | 4 (100) | 5 (83) | 9 (90) |

| Extralymphatic sites involved by lymphoma at study entry, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 0 | 4 (67) | 4 (40) |

| No | 4 (100) | 2 (33) | 6 (60) |

| Cell of origin of cancer, n (%) | |||

| Geminal center B-cell type | 2 (50) | 4 (67) | 6 (60) |

| Activated B-cell type | 1 (25) | 2 (33) | 3 (30) |

| Other | 1 (25) | 0 | 1 (10) |

| No. of previous lines of therapy, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 2 (50) | 4 (67) | 6 (60) |

| 3 | 0 | 2 (33) | 2 (20) |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 2 (50) | 0 | 2 (20) |

| Demographic characteristics . | Tisagenlecleucel + ibrutinib, preapheresis N = 4 . | Tisagenlecleucel + ibrutinib, postapheresis N = 6 . | All patients N = 10 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median, y | 59 | 64 | 61 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 0 | 2 (33) | 2 (20) |

| ECOG PS at screening, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 3 (75) | 3 (50) | 6 (60) |

| 1 | 1 (25) | 3 (50) | 4 (40) |

| ECOG PS at baseline, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 3 (75) | 1 (17) | 4 (40) |

| 1 | 1 (25) | 4 (67) | 5 (50) |

| 2 | 0 | 1 (17) | 1 (10) |

| LDH > ULN at study entry, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 2 (50) | 3 (50) | 5 (50) |

| No | 2 (50) | 3 (50) | 5 (50) |

| Stage at time of study entry, n (%) | |||

| Stage I | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Stage II | 2 (50) | 0 | 2 (20) |

| Stage III | 2 (50) | 0 | 2 (20) |

| Stage IV | 0 | 6 (100) | 6 (60) |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bone marrow involved at study entry, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 0 | 1 (17) | 1 (10) |

| No | 4 (100) | 5 (83) | 9 (90) |

| Extralymphatic sites involved by lymphoma at study entry, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 0 | 4 (67) | 4 (40) |

| No | 4 (100) | 2 (33) | 6 (60) |

| Cell of origin of cancer, n (%) | |||

| Geminal center B-cell type | 2 (50) | 4 (67) | 6 (60) |

| Activated B-cell type | 1 (25) | 2 (33) | 3 (30) |

| Other | 1 (25) | 0 | 1 (10) |

| No. of previous lines of therapy, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 2 (50) | 4 (67) | 6 (60) |

| 3 | 0 | 2 (33) | 2 (20) |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 2 (50) | 0 | 2 (20) |

LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Efficacy

Among 10 patients enrolled and treated, the best ORR (CR + PR) in the preapheresis and postapheresis arms was 4 of 4 (100%) and 3 of 6 (50%) patients, respectively. The 3-month and 6-month ORRs remained constant in the preapheresis (3/4 [75%]) and postapheresis (2/6 [33%]) arms. CR was achieved by 3 patients (75%) in the preapheresis arm and by 2 patients (33%) in the postapheresis arm. One patient achieving CR in each treatment arm was in CR before infusion in response to ibrutinib treatment. At the end of the study, 3 patients in the preapheresis arm (75%) and 1 patient in the postapheresis arm (17%) remained in remission. Median DOR, PFS, and OS were not reached in the preapheresis arm. In the postapheresis arm median DOR was 17.2 months, PFS was 1.40 months, and OS was 8.4 months (Table 2). Throughout the study, 5 deaths were reported: 4 in the postapheresis arm (67%) and 1 in the preapheresis arm (25%). All deaths were due to progressive disease.

Efficacy summary by treatment (safety set)

| Parameter . | Tisagenlecleucel + ibrutinib, preapheresis N = 4 . | Tisagenlecleucel + ibrutinib, postapheresis N = 6 . | All patients N = 10 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best overall response, n (%) | |||

| CR | 3 (75) | 2 (33) | 5 (50) |

| PR | 1 (25) | 1 (17) | 2 (20) |

| PD | 0 | 3 (50) | 3 (30) |

| ORR (CR + PR), n (%) | 4 (100) | 3 (50) | 7 (70) |

| 3-month (CR + PR) | 3 (75) | 2 (33) | 5 (50) |

| 6-month (CR + PR) | 3 (75) | 2 (33) | 5 (50) |

| Patients with DOR event, n (%) | 1 (25) | 2 (33) | 3 (30) |

| Patients censored, n (%) | 3 (75) | 1 (17) | 4 (40) |

| Median DOR, mo | NE | 17.18 | NE |

| Patients with PFS event, n (%) | 1 (25) | 5 (83) | 6 (60) |

| Patients censored, n (%) | 3 (75) | 1 (17) | 4 (40) |

| Median PFS, mo | NE | 1.40 | 10.83 |

| Patients with OS event, n (%) | 1 (25) | 4 (67) | 5 (50) |

| Patients censored, n (%) | 3 (75) | 2 (33) | 5 (50) |

| Median OS, mo | NE | 8.41 | NE |

| Parameter . | Tisagenlecleucel + ibrutinib, preapheresis N = 4 . | Tisagenlecleucel + ibrutinib, postapheresis N = 6 . | All patients N = 10 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best overall response, n (%) | |||

| CR | 3 (75) | 2 (33) | 5 (50) |

| PR | 1 (25) | 1 (17) | 2 (20) |

| PD | 0 | 3 (50) | 3 (30) |

| ORR (CR + PR), n (%) | 4 (100) | 3 (50) | 7 (70) |

| 3-month (CR + PR) | 3 (75) | 2 (33) | 5 (50) |

| 6-month (CR + PR) | 3 (75) | 2 (33) | 5 (50) |

| Patients with DOR event, n (%) | 1 (25) | 2 (33) | 3 (30) |

| Patients censored, n (%) | 3 (75) | 1 (17) | 4 (40) |

| Median DOR, mo | NE | 17.18 | NE |

| Patients with PFS event, n (%) | 1 (25) | 5 (83) | 6 (60) |

| Patients censored, n (%) | 3 (75) | 1 (17) | 4 (40) |

| Median PFS, mo | NE | 1.40 | 10.83 |

| Patients with OS event, n (%) | 1 (25) | 4 (67) | 5 (50) |

| Patients censored, n (%) | 3 (75) | 2 (33) | 5 (50) |

| Median OS, mo | NE | 8.41 | NE |

NE, not estimable; PD, progressive disease.

Safety

Overall, the combination of tisagenlecleucel and ibrutinib was well tolerated across ibrutinib preapheresis and postapheresis arms. No AEs started or worsened within 2 days of the leukapheresis procedure. All patients experienced at least 1 AE after infusion, 90% of which were treatment related (ibrutinib or tisagenlecleucel). Of 10 patients, 8 (80%) had AEs of grade ≥3 and 5 (50%) had SAEs (Table 3).23 The 1 fatal SAE (postapheresis arm) was due to LBCL disease progression. A complete list of AEs reported during the study can be found in supplemental Table 1.

Overview of AEs (safety set)

| Category . | Tisagenlecleucel + ibrutinib, preapheresis . | Tisagenlecleucel + ibrutinib, postapheresis . | All patients . |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 4 . | N = 6 . | N = 10 . | |

| n (%) . | n (%) . | n (%) . | |

| AEs∗,† | 4 (100) | 6 (100) | 10 (100) |

| Treatment-related | 3 (75) | 6 (100) | 9 (90) |

| AEs with grade ≥3 | 3 (75) | 5 (83) | 8 (80) |

| Treatment-related | 2 (50) | 3 (50) | 5 (50) |

| SAEs | 2 (50) | 3 (50) | 5 (50) |

| Treatment-related | 2 (50) | 0 | 2 (20) |

| Fatal SAEs | 0 | 1 (17) | 1 (10) |

| AEs leading to discontinuation | 1 (25) | 0 | 1 (10) |

| AEs leading to dose adjustment/interruption | 0 | 1 (17) | 1 (10) |

| AEs requiring additional therapy | 3 (75) | 6 (100) | 9 (90) |

| Category . | Tisagenlecleucel + ibrutinib, preapheresis . | Tisagenlecleucel + ibrutinib, postapheresis . | All patients . |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 4 . | N = 6 . | N = 10 . | |

| n (%) . | n (%) . | n (%) . | |

| AEs∗,† | 4 (100) | 6 (100) | 10 (100) |

| Treatment-related | 3 (75) | 6 (100) | 9 (90) |

| AEs with grade ≥3 | 3 (75) | 5 (83) | 8 (80) |

| Treatment-related | 2 (50) | 3 (50) | 5 (50) |

| SAEs | 2 (50) | 3 (50) | 5 (50) |

| Treatment-related | 2 (50) | 0 | 2 (20) |

| Fatal SAEs | 0 | 1 (17) | 1 (10) |

| AEs leading to discontinuation | 1 (25) | 0 | 1 (10) |

| AEs leading to dose adjustment/interruption | 0 | 1 (17) | 1 (10) |

| AEs requiring additional therapy | 3 (75) | 6 (100) | 9 (90) |

CTCAE, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities.

A patient with multiple severity grades for an AE is only counted under the maximum grade. A listing of medical history and current medical conditions was provided, using the MedDRA version 24.1 at the time of reporting.

AEs were graded according to CTCAE version 4.03, with the exception of CRS, which was graded using a scale by Lee et al.23

Hematological disorders, including cytopenias, were the most frequently reported all-grade (9/10 [90%]) and grade ≥3 (7/10 [70%]) AEs. Among hematological AEs, decreased white blood cell count (all-grade, 8/10 [80%]; grade ≥3, 6/10 [60%]), decreased neutrophil count (all-grade, 7/10 [70%]; grade ≥3, 4/10 [40%]), anemia (all-grade, 6/10 [60%]; grade ≥3, 3/10 [30%]), and decreased lymphocyte count (all-grade, 5/10 [50%]; grade ≥3, 5/10 [50%]) were the most common (Table 4). In the preapheresis arm, 1 patient (25%) experienced grade 3 neutropenia lasting 10 days after tisagenlecleucel infusion; no other patients had grade 3 or 4 neutropenia or thrombocytopenia. CRS was reported in 6 patients (60%): 1 patient in the preapheresis arm (25%) and 5 patients in the postapheresis arm (83%); all cases were grades 1 or 2 (Table 4). Serious neurological AEs, grades 1 or 2, were experienced by 5 patients in the postapheresis arm (83%), including 1 case of grade 1 immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome (17%). One patient in the preapheresis arm (25%) experienced the serious neurological AE of tremor (Table 4).

AEs of special interest (safety set)

| AEs, n (%) . | Tisagenlecleucel + ibrutinib, preapheresis N = 4 . | Tisagenlecleucel + ibrutinib, postapheresis N = 6 . | All patients N = 10 . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All grades . | Grade ≥3 . | All grades . | Grade ≥3 . | All grades . | Grade ≥3 . | |

| CRS | 1 (25) | 0 | 5 (83) | 0 | 6 (60) | 0 |

| Hematological disorders, including cytopenias | 3 (75) | 3 (75) | 6 (100) | 4 (67) | 9 (90) | 7 (70) |

| Anemia | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 5 (83) | 2 (33) | 6 (60) | 3 (30) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 0 | 0 | 1 (17) | 0 | 1 (10) | 0 |

| Lymphocyte count decreased | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 4 (67) | 4 (67) | 5 (50) | 5 (50) |

| Neutropenia | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 0 | 0 | 1 (10) | 1 (10) |

| Neutrophil count decreased | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 6 (100) | 3 (50) | 7 (70) | 4 (40) |

| Platelet count decreased | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 2 (33) | 1 (17) | 3 (30) | 2 (20) |

| White blood cell count decreased | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | 6 (100) | 4 (67) | 8 (80) | 6 (60) |

| Serious neurological adverse reactions | 1 (25) | 0 | 5 (83) | 0 | 6 (60) | 0 |

| Aphasia | 0 | 0 | 1 (17) | 0 | 1 (10) | 0 |

| Encephalopathy | 0 | 0 | 1 (17) | 0 | 1 (10) | 0 |

| Hallucination | 0 | 0 | 1 (17) | 0 | 1 (10) | 0 |

| Muscular weakness | 0 | 0 | 1 (17) | 0 | 1 (10) | 0 |

| Neurotoxicity | 0 | 0 | 2 (33) | 0 | 2 (20) | 0 |

| Tremor | 1 (25) | 0 | 3 (50) | 0 | 4 (40) | 0 |

| ICANS | ||||||

| Grade 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (17) | 0 | 1 (10) | 0 |

| AEs, n (%) . | Tisagenlecleucel + ibrutinib, preapheresis N = 4 . | Tisagenlecleucel + ibrutinib, postapheresis N = 6 . | All patients N = 10 . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All grades . | Grade ≥3 . | All grades . | Grade ≥3 . | All grades . | Grade ≥3 . | |

| CRS | 1 (25) | 0 | 5 (83) | 0 | 6 (60) | 0 |

| Hematological disorders, including cytopenias | 3 (75) | 3 (75) | 6 (100) | 4 (67) | 9 (90) | 7 (70) |

| Anemia | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 5 (83) | 2 (33) | 6 (60) | 3 (30) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 0 | 0 | 1 (17) | 0 | 1 (10) | 0 |

| Lymphocyte count decreased | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 4 (67) | 4 (67) | 5 (50) | 5 (50) |

| Neutropenia | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 0 | 0 | 1 (10) | 1 (10) |

| Neutrophil count decreased | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 6 (100) | 3 (50) | 7 (70) | 4 (40) |

| Platelet count decreased | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 2 (33) | 1 (17) | 3 (30) | 2 (20) |

| White blood cell count decreased | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | 6 (100) | 4 (67) | 8 (80) | 6 (60) |

| Serious neurological adverse reactions | 1 (25) | 0 | 5 (83) | 0 | 6 (60) | 0 |

| Aphasia | 0 | 0 | 1 (17) | 0 | 1 (10) | 0 |

| Encephalopathy | 0 | 0 | 1 (17) | 0 | 1 (10) | 0 |

| Hallucination | 0 | 0 | 1 (17) | 0 | 1 (10) | 0 |

| Muscular weakness | 0 | 0 | 1 (17) | 0 | 1 (10) | 0 |

| Neurotoxicity | 0 | 0 | 2 (33) | 0 | 2 (20) | 0 |

| Tremor | 1 (25) | 0 | 3 (50) | 0 | 4 (40) | 0 |

| ICANS | ||||||

| Grade 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (17) | 0 | 1 (10) | 0 |

ICANS, immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome.

Of 10 patients, while on ibrutinib, 4 (40%) had ≥1 dose interruption (2 patients in each treatment arm; Table 5). One patient in the preapheresis arm (25%) experienced 2 dose interruptions. Dose interruptions were the result of AEs in 3 patients (30%), the other 1 (10%) at physician discretion. Dose reductions were experienced by 3 patients (30%; 1 in the preapheresis arm, 2 in the postapheresis arm). Dose reductions were due to AEs in 2 patients and at physician decision in 1 patient. In total, 6 patients (60%) permanently discontinued ibrutinib (2/4 [50%] patients in the preapheresis arm, and 4/6 [67%] patients in the postapheresis arm) before 1 year. Among those who permanently discontinued ibrutinib, progressive disease was the most common reason for discontinuation (3/6 [50%]), followed by physician decision (2/6 [30%]) and AEs (1/6 [20%] reported as worsening bradycardia; Table 5).

Duration of exposure, dose adjustments, and discontinuation of ibrutinib

| Parameter . | Tisagenlecleucel + ibrutinib, preapheresis N = 4 . | Tisagenlecleucel + ibrutinib, postapheresis N = 6 . | All patients N = 10 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median duration of ibrutinib exposure (range), wk | 39.5 (13-61) | 13.0 (10-65) | 16.1 (10-65) |

| Before apheresis (n = 3) | 3.7 (3-4) | 0 | NA∗ |

| Between apheresis and infusion | 4.4 (3-6) | 4.7 (4-6) | 4.7 (3-6) |

| After infusion | 33.2 (3-52) | 7.9 (6-60) | 12.1 (3-60) |

| Ibrutinib dose reductions, n (%) | |||

| No dose reduction | 3 (75) | 4 (67) | 7 (70) |

| At least 1 dose reduction | 1 (25) | 2 (33) | 3 (30) |

| AE | 1 (25) | 1 (17) | 2 (20) |

| Physician decision | 0 | 1 (17) | 1 (10) |

| Ibrutinib dose interruptions, n (%) | |||

| No dose interruption | 2 (50) | 4 (67) | 6 (60) |

| At least 1 dose interruption | 2 (50) | 2 (33) | 4 (40) |

| AE | 2 (50) | 1 (17) | 3 (30) |

| Physician decision | 0 | 1 (17) | 1 (10) |

| Permanent ibrutinib discontinuation, n (%) | 2 (50) | 4 (67) | 6 (60) |

| AE | 1 (25) | 0 | 1 (10) |

| Physician decision | 0 | 2 (33) | 2 (20) |

| Progressive disease | 1 (25) | 2 (33) | 3 (30) |

| Parameter . | Tisagenlecleucel + ibrutinib, preapheresis N = 4 . | Tisagenlecleucel + ibrutinib, postapheresis N = 6 . | All patients N = 10 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median duration of ibrutinib exposure (range), wk | 39.5 (13-61) | 13.0 (10-65) | 16.1 (10-65) |

| Before apheresis (n = 3) | 3.7 (3-4) | 0 | NA∗ |

| Between apheresis and infusion | 4.4 (3-6) | 4.7 (4-6) | 4.7 (3-6) |

| After infusion | 33.2 (3-52) | 7.9 (6-60) | 12.1 (3-60) |

| Ibrutinib dose reductions, n (%) | |||

| No dose reduction | 3 (75) | 4 (67) | 7 (70) |

| At least 1 dose reduction | 1 (25) | 2 (33) | 3 (30) |

| AE | 1 (25) | 1 (17) | 2 (20) |

| Physician decision | 0 | 1 (17) | 1 (10) |

| Ibrutinib dose interruptions, n (%) | |||

| No dose interruption | 2 (50) | 4 (67) | 6 (60) |

| At least 1 dose interruption | 2 (50) | 2 (33) | 4 (40) |

| AE | 2 (50) | 1 (17) | 3 (30) |

| Physician decision | 0 | 1 (17) | 1 (10) |

| Permanent ibrutinib discontinuation, n (%) | 2 (50) | 4 (67) | 6 (60) |

| AE | 1 (25) | 0 | 1 (10) |

| Physician decision | 0 | 2 (33) | 2 (20) |

| Progressive disease | 1 (25) | 2 (33) | 3 (30) |

NA, not applicable.

Not all patients received ibrutinib treatment before apheresis.

Cellular kinetics

After tisagenlecleucel infusion, CAR transgene levels in the peripheral blood were measured using qPCR and reported by patient response status (Table 6). Among responders (CR/PR) in the preapheresis arm (n = 3), Cmax (geometric mean [geometric coefficient of variation, %]) was 590 (117.8%) copies per microgram, whereas in the postapheresis arm (n = 3), Cmax (geometric mean [geometric coefficient of variation, %]) was 3980 (160.2%) copies per microgram. Maximal expansion (geometric mean [geometric coefficient of variation, %]) for 2 patients with stable disease/progressive disease with evaluable kinetics in the postapheresis arm was 1350 (278.1%). There were no nonresponders in the preapheresis arm. Median Tmax among responders was 10 and 6 days in the preapheresis and postapheresis treatment arms, respectively. The 2 nonresponders in the postapheresis arm had a Tmax of 10 days. Median Tlast of CAR+ T cells was 26.2 days in the preapheresis arm (all responders) and 282 days for responders or 37.9 days for nonresponders in the postapheresis arm. CAR+ T cells were detected for as long as 658 days and 752 days in preapheresis and postapheresis arms, respectively (Table 6). Longitudinal qPCR profiles quantifying transgene expression/expansion can be seen in supplemental Figure 2. Higher tisagenlecleucel expansion was associated with the occurrence of CRS. Maximal expansion (geometric mean [geometric coefficient of variation, %]) was 2390 (158.7%) copies per microgram and 357 (49.6%) copies per microgram in patients with grade 1 or 2 CRS and in patients with no CRS, respectively.

Peripheral blood cellular kinetic parameters for tisagenlecleucel by qPCR, by treatment group, and by best overall response (pharmacokinetic analysis set)

| . | Tisagenlecleucel + ibrutinib, preapheresis N = 4 . | Tisagenlecleucel + ibrutinib, postapheresis N = 5 . | All patients N = 9 . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter . | Statistics . | CR/PR . | SD/PD . | CR/PR . | SD/PD . | |

| AUC0-28d, copies/microgram × days | n | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 7 |

| Geo-mean | 10 100 | 39 300 | 13 300 | 19 500 | ||

| Geo-CV% | 97.8 | 76.2 | 256.1 | 135.4 | ||

| Cmax, copies/microgram | n | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 8 |

| Geo-mean | 590 | 3 980 | 1 350 | 1 490 | ||

| Geo-CV% | 117.8 | 160.2 | 278.1 | 212.1 | ||

| Tmax, d | n | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 8 |

| Median | 10.1 | 6.17 | 9.88 | 9.80 | ||

| Min; max | 5.51; 16.1 | 2.72; 9.76 | 9.85; 9.91 | 2.72; 16.1 | ||

| Tlast, d | n | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 8 |

| Median | 26.2 | 282 | 37.9 | 38.2 | ||

| Min; max | 12.8; 658 | 27.4; 752 | 27.0; 48.9 | 12.8; 752 | ||

| . | Tisagenlecleucel + ibrutinib, preapheresis N = 4 . | Tisagenlecleucel + ibrutinib, postapheresis N = 5 . | All patients N = 9 . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter . | Statistics . | CR/PR . | SD/PD . | CR/PR . | SD/PD . | |

| AUC0-28d, copies/microgram × days | n | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 7 |

| Geo-mean | 10 100 | 39 300 | 13 300 | 19 500 | ||

| Geo-CV% | 97.8 | 76.2 | 256.1 | 135.4 | ||

| Cmax, copies/microgram | n | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 8 |

| Geo-mean | 590 | 3 980 | 1 350 | 1 490 | ||

| Geo-CV% | 117.8 | 160.2 | 278.1 | 212.1 | ||

| Tmax, d | n | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 8 |

| Median | 10.1 | 6.17 | 9.88 | 9.80 | ||

| Min; max | 5.51; 16.1 | 2.72; 9.76 | 9.85; 9.91 | 2.72; 16.1 | ||

| Tlast, d | n | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 8 |

| Median | 26.2 | 282 | 37.9 | 38.2 | ||

| Min; max | 12.8; 658 | 27.4; 752 | 27.0; 48.9 | 12.8; 752 | ||

AUC, area under the curve; AUC0-28d, AUC from time zero to day 28; Clast, last quantifiable concentration in peripheral blood; Cmax, maximum (peak) concentration in the peripheral blood; CV%, percent coefficient of variation; Geo-mean, geometric mean; max, maximum; min, minimum; PD, progressive disease; Tlast, time to last observed quantifiable concentration in peripheral blood; SD, stable disease.

Humoral and cellular immunogenicity

At baseline, 8 patients (80%) tested positive for mCAR19 antibodies. Treatment-induced anti-mCAR19 antibodies was observed in 1 patient (25%) in the preapheresis arm. Cellular immunogenicity responses (T-cell activation in the peripheral blood) remained low for most patients throughout the study (<1%).

Manufacturing

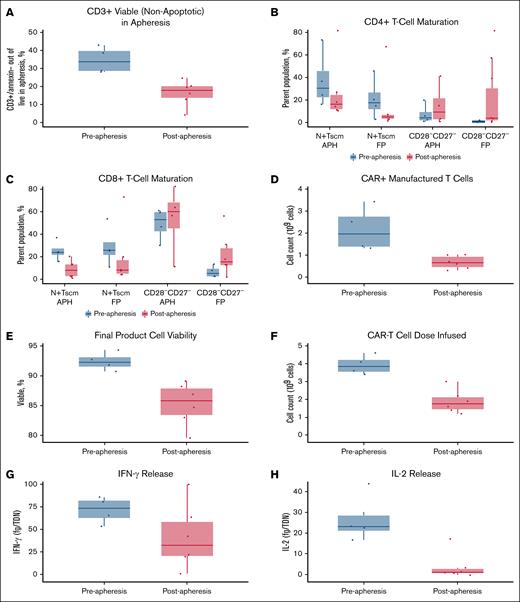

Leukapheresis material collected from patients in the preapheresis arm showed a higher proportion of viable (nonapoptotic) CD3+ cells compared with apheresis material collected from patients in the postapheresis arm (Figure 1A). Ibrutinib treatment before apheresis was associated with lower percentages of senescent (CD27−CD28−) CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the apheresis and final product material compared with the postapheresis arm; a higher percentage of naive/T-cell stem cell memory (Tscm) cells was also observed compared with the postapheresis arm, but this elevated level was already present at screening (Figures 1B-C and 2). No trends in CD8+ or CD4+ central memory (CCR7+CD45RA−) T-cell abundance (percentage) were observed (Figure 2). The differences seen in leukapheresis material were retained after manufacturing. Among patients in the preapheresis arm, the final manufactured product had a higher total CAR+ cell number and higher percent viability compared with the postapheresis arm (Figures 1D-E). As a result, patients in the preapheresis arm received a twofold higher median tisagenlecleucel dose of CAR+ viable T cells (3.85 × 108 [range, 3.4 × 108 to 4.6 × 108] vs 1.75 × 108 [range, 1.2 × 108 to 3.0 × 108], respectively; Figure 1F) and a sixfold higher median total T-cell dose than the postapheresis arm. The final product material from patients in the preapheresis arm was characterized by increased production of IFN-γ (effector cytokine considered as a biomarker for potency; Figure 1G) and increased production of interleukin-2 (IL-2; proliferative cytokine considered a marker of self-renewal) upon antigen-specific stimulation compared with the postapheresis arm (Figure 1H). In contrast, the final product from patients in the postapheresis arm showed very low levels of IL-2 release upon antigen-specific stimulation (Figure 1H).

Apheresis and final product characterization. (A) Percentage of CD3+ cells in apheresis material. (B) Proportion of CD4+ naive/Tscm and CD28−CD27− cells in collected apheresis material and final product. (C) Proportion of CD8+ naive/Tscm and CD28−CD27− cells in collected apheresis material and final product. (D) CAR+ manufactured cell count. (E) Cell viability in final product. (F) Number of CAR+ T cells dosed. (G) IFN-γ production by final product after antigen-specific stimulation. (H) IL-2 production by the final product after antigen-specific stimulation. fg, femtogram; FP, final product; N, naive; TDN, transduced cell number.

Apheresis and final product characterization. (A) Percentage of CD3+ cells in apheresis material. (B) Proportion of CD4+ naive/Tscm and CD28−CD27− cells in collected apheresis material and final product. (C) Proportion of CD8+ naive/Tscm and CD28−CD27− cells in collected apheresis material and final product. (D) CAR+ manufactured cell count. (E) Cell viability in final product. (F) Number of CAR+ T cells dosed. (G) IFN-γ production by final product after antigen-specific stimulation. (H) IL-2 production by the final product after antigen-specific stimulation. fg, femtogram; FP, final product; N, naive; TDN, transduced cell number.

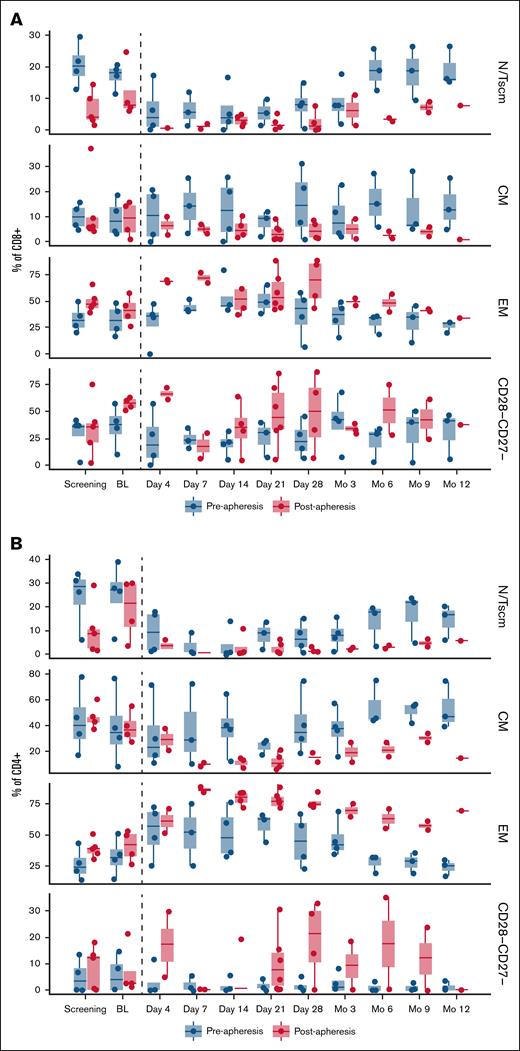

Clinical PBMC biomarker analysis. (A) Plot of CD8+CD4− T-cell populations by treatment arm and visit. (B) Plot of CD4+CD8− T-cell populations by treatment arm and visit. Only visits through month 12 are presented. Day −1 visits were used as baseline except for patients with missing day −1 assessments (n = 2). For these 2 patients, the most recent pretreatment unscheduled visit was used as baseline. BL, baseline; CM, central memory; EM, effector memory; N/Tscm, naive/stem cell memory T cell; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell.

Clinical PBMC biomarker analysis. (A) Plot of CD8+CD4− T-cell populations by treatment arm and visit. (B) Plot of CD4+CD8− T-cell populations by treatment arm and visit. Only visits through month 12 are presented. Day −1 visits were used as baseline except for patients with missing day −1 assessments (n = 2). For these 2 patients, the most recent pretreatment unscheduled visit was used as baseline. BL, baseline; CM, central memory; EM, effector memory; N/Tscm, naive/stem cell memory T cell; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell.

Postinfusion biomarker and immunophenotype analysis

Some T-cell differences were observed between preapheresis and postapheresis arms at screening (ie, naive or effector memory cells). Furthermore, both the CD4+ and CD8+ populations in the postapheresis arm had higher proportions of exhausted/senescent T cells (CD27−CD28−) than in the preapheresis arm (Figure 2). Phenotypic differences between treatment arms were maintained through month 12.

Discussion

Ibrutinib administered in combination with tisagenlecleucel was feasible and well tolerated by patients in both the preapheresis and postapheresis settings, as well as during lymphodepletion, tisagenlecleucel infusion, and the postinfusion period. Overall, the preapheresis arm had lower rates of CRS and discontinuation, along with higher response rates, than the postapheresis arm. However, the differences in outcomes between the preapheresis and postapheresis arms should be interpreted with caution and used primarily for hypothesis generation due to the low number of patients in each cohort and heterogeneous disease characteristics in the 2 treatment arms.24,25 At study entry, for example, patients in the postapheresis arm had more advanced disease, more frequent extralymphatic site involvement, and higher ECOG PS.

Despite the small number of patients, individual patient cellular kinetics over time were consistent with the interpatient variability seen in the expansion profiles observed in the JULIET clinical trial of tisagenlecleucel in R/R LBCL.26,27 Although data from this study indicate that patients in the postapheresis arm had greater CAR T-cell expansion in vivo than patients in the preapheresis arm, such comparisons should be interpreted with caution because of the small sample size and high interindividual variability. This enhanced expansion observed in the postapheresis group, however, may have contributed to the increased incidence of CRS observed in the postapheresis arm. A similar positive association between maximal in vivo expansion and CRS severity was observed in JULIET.28 All 5 patients who experienced grade 1 CRS in the postapheresis arm had higher mean expansion relative to the mean observed in the preapheresis arm. Furthermore, the 1 patient in the preapheresis arm who experienced grade 1 CRS had the highest expansion relative to other patients in the preapheresis arm. Based on previous observations of cellular kinetics in the JULIET trial, differences in in vivo expansion between the 2 groups are unlikely to have arisen from differences in dose or selected final product attributes (eg, transduction efficiency, viability).28 No conclusions can be made regarding the effect of ibrutinib on CAR T-cell persistence in the 2 treatment arms because there were too few patients with available data.

Differences in leukapheresis material between the 2 arms may have contributed to efficacy outcomes.29-31 Patients in the preapheresis arm showed a lower proportion of senescent T cells compared with material collected from patients in the postapheresis arm. Patients in the preapheresis arm also had lower ECOG PS and no extralymphatic involvement, which may indicate more indolent disease. This, together with the retention of naive/Tscm cells, likely contributed to a final product with reduced abundance of exhaustion/senescence markers; preserved IFN-γ secretion; and, notably, increased IL-2 production. In particular, the increased IL-2 production may have contributed to the enhanced antitumor efficacy seen in the preapheresis arm.32 Together, this may also support the collection of T cells earlier in a patient’s disease course to maintain a higher percentage of naive/Tscm phenotype in the leukapheresis material.

Overall, compared with ibrutinib administration after leukapheresis, providing ibrutinib before leukapheresis may improve T-cell characteristics in the collected material, thereby improving the quality of the final manufactured product and clinical outcomes, regardless of in vivo expansion, for patients with R/R LBLC treated with tisagenlecleucel. These data suggest that the T-cell phenotype in the leukapheresis and/or final product material may be more, or at least as, important to improving clinical outcomes with CAR T-cell therapy than modulating the in vivo immunosuppressive environment with ibrutinib. Further studies are needed to confirm these findings and to better characterize not only the pretreatment impact of ibrutinib but also the importance of T-cell phenotype on clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and families enrolled in this study as well as the investigators and study site personnel. Medical writing support was provided by Kymberleigh Frankovich of HCG, and funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

The study was sponsored by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Authorship

Contribution: J.C.C., A.B., B.E., and S.J.S. designed the study; J.C.C., E.N., F.L.L., and S.J.S. were involved with patient accrual and clinical care; and all authors contributed to the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of interest-disclosure: J.C.C. reports consultancy with Kite Pharma, Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), MorphoSys, Bayer, Karyopharm, AbbVie, BeiGene, Adicet, Cellectar, and Pfizer; speakers bureau fees from BeiGene and Epizyme; and research funding from Merck and AstraZeneca. E.N. reports travel support from Genentech and Genmab. A.B. ended employment with Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research and reports current employment at AstraZeneca. A.L. and R.A. report current employment with Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research. J.M. reports current employment with, is a current holder of stock options in, and holds patents with, Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research. D.Q. and P.K. report current employment and stock holdings with Novartis. F.L.L. reports consultancy/scientific advisory role with A2, Allogene, Amgen, Bluebird Bio, BMS/Celgene, Calibr, Caribou, Cellular Biomedicine Group, Cowen, Daiichi Sankyo, EcoR1, Emerging Therapy Solutions, GammaDelta Therapeutics, Gerson Lehrman Group, Iovance, Kite Pharma, Janssen, Legend Biotech, Novartis, Sana, Takeda, Wugen, Umoja, and Pfizer; reports contracts for service with Kite Pharma (institutional), Allogene (institutional), CERo Therapeutics (institutional), Novartis (institutional), BlueBird Bio (institutional), BMS (institutional), National Cancer Institute, and Leukemia and Lymphoma Society; reports education/editorial activities with Aptitude Health, American Society of Hematology, BioPharma Communications CARE Education, Clinical Care Options Oncology, Imedex, and Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer; and holds several institutional patents (unlicensed) in the field of cellular immunotherapy. B.E. ended employment with Novartis, is a current holder of stocks, and holds patents with Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research; and reports current employment with Miltenyi Biotec. P.G. ended employment with Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation and reports current employment at Genentech. M.L. reports current employment with IQVIA and is contracted by Novartis. D.H. reports current employment with Novartis and is a Novartis shareholder. M.M. ended employment with Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research and reports current employment at AstraZeneca and is a Novartis shareholder. S.J.S. reports consultancy with, and honoraria from, Allogene, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Genentech, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Juno/Celgene, Loxo Oncology, Nordic Nanovector, Novartis, and Tessa Therapeutics; and research funding from Novartis, Genentech, and F. Hoffmann-La Roche.

The current affiliation for A.B. is AstraZeneca, Cambridge, UK.

The current affiliation for B.E. is Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany.

The current affiliation for J.C.C. is Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL.

The current affiliation for P.G. is Genentech, South San Francisco, CA.

The current affiliation for M.M. is AstraZeneca, Barcelona, Spain.

Correspondence: Julio C. Chavez, Department of Malignant Hematology, Moffitt Cancer Center, 12902 Magnolia Dr, CSB7, Tampa, FL 33612; email: jcesar.chavez@gmail.com.

References

Author notes

Presented, in part, at the 62nd annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, virtual, 5 to 8 December 2020 (doi:10.1182/blood-2020-134270).

Novartis is committed to sharing with qualified external researchers access to patient-level data and supporting clinical documents from eligible studies. These requests are reviewed and approved by an independent review panel based on scientific merit. All data provided are anonymized to respect the privacy of patients who have participated in the trial in line with applicable laws and regulations. The data availability of these trials is according to the criteria and process described at www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.