Key Points

The JAK1 inhibitor, itacitinib, combined with alemtuzumab (CAMPATH) was safe and well tolerated in patients with T-PLL.

Itacitinib improved constitutional symptoms in patients with T-PLL and resulted in encouraging response and survival outcomes with CAMPATH.

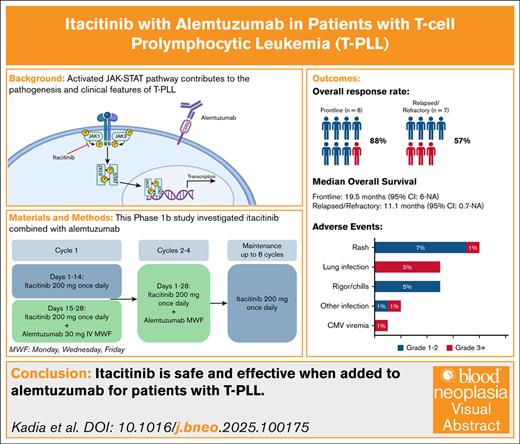

Visual Abstract

T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia (T-PLL) is a mature T-cell neoplasm with an aggressive clinical course. Overall prognosis is poor, and treatment relies on alemtuzumab because of inadequate response to conventional chemotherapy. Three-quarters of cases harbor activating mutations in the JAK-STAT pathway (JAK1, JAK3, STAT5B, IL2RG). We report safety and efficacy from a phase 1B study evaluating the combination of the JAK1 inhibitor itacitinib with alemtuzumab. Patients (N = 15) were aged >18 years, with treatment-naïve (n = 8) or relapsed/refractory (n = 7) T-PLL with adequate organ function, European Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status ≤2, and platelet >30 × 103/μL. Cycle 1 included a lead-in phase with itacitinib monotherapy days 1-14. Beginning day 15, patients also received alemtuzumab 30mg IV 3 times weekly for up to 4 (28-day) cycles or until best response. At best response, up to 8 cycles of maintenance with single-agent itacitinib was allowed. Median age was 65 years (range, 39-83). Ten patients (67%) had complex cytogenetics, 11 (73%) had chromosome 14 abnormality, and 13 (87%) were TCL1A positive by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Among frontline patients, overall response rate (ORR) was 88% (complete remission [CR]: 75%), median event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) were 11.6 and 19.5 months, respectively. Three frontline patients proceeded to allogeneic stem cell transplantation. The ORR in the relapsed/refractory cohort was 57% (CR: 43%), whereas median EFS and OS were 11.1 months. Most (85%) adverse events were grade 1 to 2 and none were attributed to itacitinib. Continued studies evaluating JAK inhibitors in patients with T-PLL are warranted. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT03989466.

Introduction

T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia (T-PLL) is an incurable T-cell leukemia characterized by the proliferation of mature, postthymic prolymphocytes. T-PLL is characterized morphologically as small to medium-sized lymphoid cells with strong positivity for CD52. These lymphocytes are usually positive for CD2, CD3, CD5, CD7, and CD4 with variable positivity of CD8, but negative for terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT), and CD1a. Approximately 90% of patients with T-PLL have recurrent rearrangements of the TCL1 gene located on chromosome 14, such as inv(14)(q11; q32); t(14;14)(q11;q32); and t(X;14)(q28;q11), all leading to the dysregulation of the TCL1 gene family.1 Although uncommon, a subset of T-PLL cases can be TCL1 negative.2 In addition, inactivation of the ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) gene has been described in over two-thirds of cases of T-PLL. Consensus criteria were developed in 2019 by the T-PLL International Study Group in an effort to standardize the diagnostic criteria for T-PLL, such as bone marrow morphology, cytogenetic and molecular findings, as well as a proposed response criterion.3 The prognosis of T-PLL remains poor, with no currently approved therapy. Various cytotoxic chemotherapy agents, such as the purine analogs such as fludarabine, cladribine, and pentostatin, have demonstrated limited activity and nondurable responses.4 Little advancement has been made since the observation of strong CD52 expression led to the investigation of IV alemtuzumab for treatment of T-PLL >2 decades ago, improving median overall survival (OS) from 7 to 17 months in the frontline setting.5-7 Even with consolidative stem cell transplantation (SCT), the estimated 6-year OS rate is only 30%.8,9 Therefore, there is a critical need to identify additional treatments to improve long-term outcomes in patients with T-PLL.

Novel genetic sequencing techniques have identified mutations in the IL2RG-JAK-STAT5B pathway as a key factor contributing to continuous activation of downstream signaling in T-PLL.10-14JAK or STAT mutations occur in ∼50% to 60% of T-PLL cases.10-14 In vitro, use of the STAT5 inhibitor pimozide led to tumor cell death in T-PLL cell lines.10 This observation prompted the use of clinically available JAK inhibitors in patients with relapsed T-PLL and paved the way for potential clinical trials to explore treatments targeting the JAK-STAT pathway. Clinical responses have been reported among relapsed patients treated with the JAK inhibitors tofacitinib and ruxolitinib in combination with alemtuzumab and venetoclax, respectively.15-20 Itacitinib (INCB039110) is an oral JAK1 inhibitor that potently inhibits JAK1 with less selectivity for JAK2, JAK3 and other non-JAK family kinases. In addition, itacitinib has been proven to suppress cytokine signaling, STAT phosphorylation, and cell growth in cell lines dependent on cytokines, such as interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-23, and IL-6.21 Itacitinib has a favorable toxicity profile in patients with hematological malignancies. Tolerability and symptom improvement in patients with myelofibrosis was demonstrated in a phase 2 study with itacitinib.22 In addition, fewer infectious complications were observed compared with systemic steroids in a phase 3 study evaluating itacitinib for the treatment of acute graft-versus-host disease.23,24 To further investigate its safety, tolerability, and activity in patients with T-PLL, we conducted a phase 1B study combining itacitinib with alemtuzumab.

Methods

Patients

This is a single-center, single-arm, cohort expansion investigator-initiated phase 1B pilot study to assess the safety and tolerability of itacitinib in combination with alemtuzumab in patients with T-PLL. T-PLL consensus definition was used for the diagnosis of T-PLL.3 Patients negative for T-cell leukemia/lymphoma1A gene (TCL1A) by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) were subsequently evaluated with a chronic lymphocytic leukemia FISH panel for detection of ATM gene (11q22.3) deletion. Treatment naïve and relapsed/refractory (R/R) patients with active T-PLL aged 18 years or older with European Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status ≤2, adequate liver and kidney function, ejection fraction >45%, and platelet count >30 × 103/μL were eligible for study enrollment. Patients with a history of a previous malignancy were required to demonstrate adequate control and no evidence of disease at the time of enrollment. Details of inclusion and exclusion criteria are available in the supplemental clinical trial protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients enrolled in the study. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX), and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The trial is registered (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03989466).

Treatment

This was a dose deescalation study to determine the maximum tolerated dose of itacitinib, starting at the treatment dose of 200 mg by mouth once daily, and deescalating using the 3+3 design if dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) occurred. Each cycle consisted of 28 days. Cycle 1 of treatment consisted of a monotherapy phase of itacitinib 200 mg by mouth once daily on days 1 to 14 to explore single-agent efficacy and toxicity before the addition of alemtuzumab. After an initial 3-day ramp-up, alemtuzumab 30 mg IV was administered 3 times weekly on days 15 to 28 of cycle 1 (supplemental Figure 1). The combination of itacitinib 200 mg by mouth once daily and alemtuzumab 30 mg IV 3 times weekly was administered for up to a total of 4 cycles. Maintenance with single-agent itacitinib 200 mg by mouth once daily continued for up to an additional 8 cycles starting at the time of best response. Patients deriving benefit could continue itacitinib beyond the initial 12-cycle course for an additional 12 cycles with approval from the principal investigator. Alemtuzumab was administered with premedications such as acetaminophen and diphenhydramine according to institutional standards. Supportive care measures included hematopoietic growth factors at the discretion of the treating physician in addition to antibacterial, antifungal (including Pneumocystis jirovecii prophylaxis), and antiviral prophylaxis following the standard of care. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) polymerase chain reaction monitoring was conducted regularly throughout study treatment. Coadministration of strong CYP3A4 inhibitors increases exposure to itacitinib,25 therefore itacitinib was reduced to 100 mg once daily when coadministered with strong CYP3A4 inhibitors such as voriconazole or posaconazole. Supplemental Figure 1 provides details of the study protocol.

Safety and response assessment

Adverse events (AEs) were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Event version 5. The first 6 weeks of study treatment were the DLT-defining period. Patients were evaluable for toxicity from the time of their first treatment on study. DLT was defined as grade 3 or greater nonhematologic toxicities and grade 3 or 4 hematologic toxicity persisting for 42 days or more posttherapy interruption, in the presence of a hypocellular bone marrow and no evidence of T-PLL. Events occurring commonly in leukemia, such as tumor lysis syndrome, anemia, myelosuppression (<42 days), and infection and/or fever (including in the setting of grade 3-4 neutropenia) were not included in the definition of DLT.

Patients who received at least 1 cycle of therapy were evaluated for response according to the TPLL-International Study Group response criteria.3 Response assessment including bone marrow evaluation and/or computed tomography scan was conducted on day 28 (+/˗ 7 days) of cycle 1. Repeat assessments were conducted on day 28 (+/˗ 7 days) of cycle 2 or beyond as indicated until remission was achieved or nonresponse. Measurable residual disease (MRD) was assessed using multiparameter flow cytometry (MFC) on bone marrow samples. Conventional G-banded karyotyping was performed using standard techniques. Complex karyotype was defined as >3 chromosomal abnormalities. FISH was performed using a dual color break-apart probe to detect TCL1A rearrangements, located at 14q32.13-q32.2. Next-generation sequencing ([NGS] using an 81-gene panel including JAK1, JAK3, STAT5B) was also conducted by bone marrow at baseline and at the end of cycle 1 using an in-house Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified lab.

Statistical analysis

The primary objective was to assess the safety profile of the combination of itacitinib and alemtuzumab in patients with T-PLL. Statistical analysis was performed for the total study population and for frontline and R/R patients separately. No formal hypothesis testing was conducted. Secondary objectives included rate of overall response (complete remission [CR] plus partial remission [PR]), time to response, response duration, event free survival (EFS), and OS in patients with T-PLL treated with itacitinib and alemtuzumab. Single-agent activity of itacitinib was also explored. Survival analysis was carried out for MRD-free survival, CR durability, duration of response (DOR) (including patients showing PR and CR), EFS, and OS for the frontline and R/R patients.

Patients who received any study drug were included in the safety analysis. After informed consent, all reported AEs, drug exposure, and reasons for drug discontinuation were recorded. Descriptive statistics, such as median and range for continuous variables, and percentages for categorical values, were used to summarize the data.

Stata (version 18) MP edition (StataCorp 2023. Stata Statistical Software: Release 18. StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX) was used for statistical analysis and Kaplan-Meier estimator curves, and R software (R Core Team [2023]. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/) for swimmer plot.

Results

Patients

Fifteen patients were enrolled in the study between January 2020 and June 2023, including 8 (53%) treatment-naïve and 7 (47%) R/R patients (Table 1). The median age was 65 years (range, 39-83), and 5 patients (33%) were aged 75 years or older. Most patients were White non-Hispanic (73%) and had an European Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status of 1 (80%). Ten patients (67%) were female. A history of prior malignancy was present in 40% of cases, including 3 patients (20%) who received chemotherapy or radiotherapy for the prior malignancy. Among the 8 treatment-naïve patients, the median age was 70 years (range, 39-83) and 75% were female. Seven patients with R/R disease were enrolled with a median age of 60 years (range, 45-80). Six (86%) R/R patients had previously received alemtuzumab-based therapy, and 2 had undergone allogeneic SCT. Patients in the frontline cohort had a higher median white blood cells (71 × 103/μL vs 27 × 103/μL), absolute lymphocyte count (69 × 103/μL vs 58 × 103/μL), and serum lactate dehydrogenase (492 U/L vs 351 U/L) prior to initiating therapy compared with R/R patients.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristic . | Front line (n = 8) . | Relapsed (n = 7) . | Total (N = 15) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 70 | (39-83) | 60 | (45-80) | 65 | (39-83) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 6 | (75) | 4 | (57) | 10 | (67) |

| Male | 2 | (25) | 3 | (43) | 5 | (33) |

| Race | ||||||

| White Hispanic or Latino | — | — | 1 | (14) | 1 | (7) |

| White Non-Hispanic | 6 | (75) | 5 | (71) | 11 | (73) |

| Other Hispanic or Latino | 2 | (25) | — | — | 2 | (13) |

| Native American Non-Hispanic | — | — | 1 | (14) | 1 | (7) |

| ECOG PS | ||||||

| 0 | 1 | (12) | — | — | 1 | (7) |

| 1 | 5 | (63) | 7 | (100) | 12 | (80) |

| 2 | 2 | (25) | — | — | 2 | (13) |

| Prior malignancy | ||||||

| Yes | 3 | (38) | 3 | (43) | 6 | (40) |

| Chemotherapy | 1 | (12) | 1 | (14) | 2 | (13) |

| Radiotherapy | 1 | (12) | 1 | (14) | 2 | (13) |

| — | — | Previous number of therapies | — | — | ||

| 1 | — | — | 4 | (57) | — | — |

| 2 | — | — | 2 | (29) | — | — |

| 3 | — | — | 1 | (14) | — | — |

| Alemtuzumab | — | — | 6 | (86) | — | — |

| Stem cell transplant | — | — | 2 | (29) | — | — |

| Laboratory values | ||||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.6 | (9-13.3) | 11.4 | (7.2-14.8) | 11.4 | (7.2-14.8) |

| Platelet count (103/μL) | 111 | (37-176) | 95 | (23-201) | 108 | (23-201) |

| White blood count (103/μL) | 71 | (9.6-181.6) | 27 | (2-68.6) | 29 | (2-181.6) |

| Lymphocyte count (103/μL) | 69 | (2-92) | 58 | (19-84) | 68 | (2-92) |

| Neutrophil count (103/μL) | 10 | (2-35) | 22 | (11-47.7) | 14 | (2-47.7) |

| Serum lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 492 | (244-610) | 351 | (220-1361) | 485 | (220-1361) |

| Serum β-2-microglobulin (mg/L) | 2.8 | (2.5-3) | 5.3 | (2.3-12.6) | 3.0 | (2.3-12.6) |

| Characteristic . | Front line (n = 8) . | Relapsed (n = 7) . | Total (N = 15) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 70 | (39-83) | 60 | (45-80) | 65 | (39-83) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 6 | (75) | 4 | (57) | 10 | (67) |

| Male | 2 | (25) | 3 | (43) | 5 | (33) |

| Race | ||||||

| White Hispanic or Latino | — | — | 1 | (14) | 1 | (7) |

| White Non-Hispanic | 6 | (75) | 5 | (71) | 11 | (73) |

| Other Hispanic or Latino | 2 | (25) | — | — | 2 | (13) |

| Native American Non-Hispanic | — | — | 1 | (14) | 1 | (7) |

| ECOG PS | ||||||

| 0 | 1 | (12) | — | — | 1 | (7) |

| 1 | 5 | (63) | 7 | (100) | 12 | (80) |

| 2 | 2 | (25) | — | — | 2 | (13) |

| Prior malignancy | ||||||

| Yes | 3 | (38) | 3 | (43) | 6 | (40) |

| Chemotherapy | 1 | (12) | 1 | (14) | 2 | (13) |

| Radiotherapy | 1 | (12) | 1 | (14) | 2 | (13) |

| — | — | Previous number of therapies | — | — | ||

| 1 | — | — | 4 | (57) | — | — |

| 2 | — | — | 2 | (29) | — | — |

| 3 | — | — | 1 | (14) | — | — |

| Alemtuzumab | — | — | 6 | (86) | — | — |

| Stem cell transplant | — | — | 2 | (29) | — | — |

| Laboratory values | ||||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.6 | (9-13.3) | 11.4 | (7.2-14.8) | 11.4 | (7.2-14.8) |

| Platelet count (103/μL) | 111 | (37-176) | 95 | (23-201) | 108 | (23-201) |

| White blood count (103/μL) | 71 | (9.6-181.6) | 27 | (2-68.6) | 29 | (2-181.6) |

| Lymphocyte count (103/μL) | 69 | (2-92) | 58 | (19-84) | 68 | (2-92) |

| Neutrophil count (103/μL) | 10 | (2-35) | 22 | (11-47.7) | 14 | (2-47.7) |

| Serum lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 492 | (244-610) | 351 | (220-1361) | 485 | (220-1361) |

| Serum β-2-microglobulin (mg/L) | 2.8 | (2.5-3) | 5.3 | (2.3-12.6) | 3.0 | (2.3-12.6) |

Data presented as n (%) or median (range).

ECOG PS, European Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status.

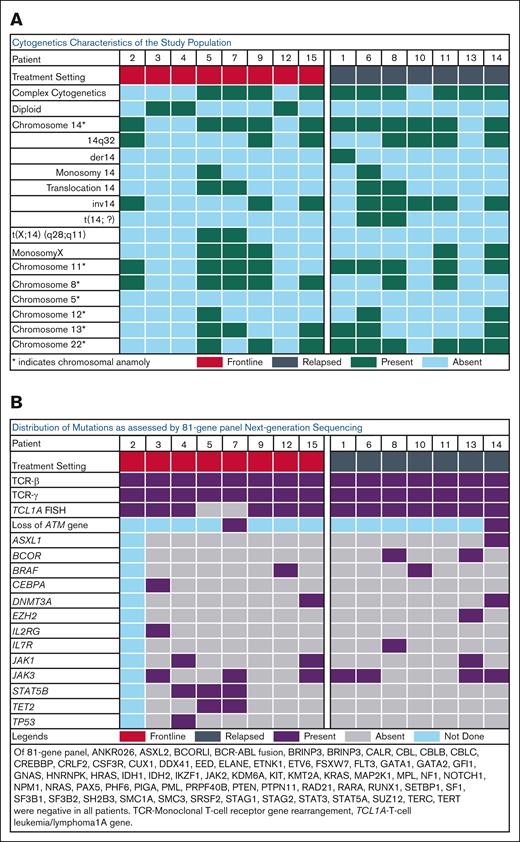

Karyotype analysis is detailed in Table 2 and Figure 1A. Complex karyotypes were predominant (67%), particularly in R/R cases (86%). Chromosome 14 abnormalities were present in 11 patients (73%) including inv(14)(q11;q32) in 8 patients (53%), and translocations involving chromosome 14 in 4 patients (27%). Two patients in the frontline setting had t(X;14)(q28;q11). Abnormalities in chromosome 11 and chromosome 22 were observed in 9 patients (60%) each; 7 patients (47%) had a chromosome 8 abnormality, 6 patients (40%) had a chromosome 13 abnormality, 3 patients (20%) had a chromosome 12 abnormality, and 5 patients (33%) had monosomy X. None of the 15 patients exhibited chromosome 5 anomaly. All R/R patients and 6 (75%) frontline patients had TCL1A rearrangement; 87% of the total study population. Both frontline patients without TCLIA gene rearrangement had t(X;14)(q28;q11), consistent with mature T-cell proliferation (MTCP1) rearrangement. One of these patients also had loss of ATM gene (11q22.3) by FISH. A comprehensive 81-gene NGS panel was performed on 14 patients (Table 2; Figure 1B). NGS revealed JAK3 as the predominant recurrent somatic point mutation (47%) overall. Among the frontline patients, JAK3 and STAT5B were the most common mutations (38% each), followed by JAK1 (25%). One patient in the frontline cohort had a TP53 mutation. JAK3 mutations were present in 57% of patients in the R/R cohort, in addition to BCOR (29%), JAK1 (14%) and BRAF (14%).

Cytogenetic and genomic characteristics

| Characteristic . | Front line (n = 8) . | Relapsed (n = 7) . | Total (N = 15) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytogenetics | ||||||

| Complex | 4 | (50) | 6 | (86) | 10 | (67) |

| Diploid | 3 | (38) | — | — | 3 | (20) |

| Chromosome 14 abnormality∗ | 5 | (63) | 6 | (86) | 11 | (73) |

| inv14 | 3 | (38) | 5 | (71) | 8 | (53) |

| Translocations 14 | 2 | (25) | 2 | (29) | 4 | (27) |

| Monosomy X | 3 | (38) | 2 | (29) | 5 | (33) |

| t(X;14)(q28;q11) | 2 | (25) | — | — | 2 | (13) |

| Chromosome 8 abnormality | 5 | (63) | 2 | (29) | 7 | (47) |

| Chromosome 11 abnormality | 4 | (50) | 5 | (71) | 9 | (60) |

| Chromosome 12 abnormality | 1 | (12) | 2 | (29) | 3 | (20) |

| Chromosome 13 abnormality | 3 | (38) | 3 | (43) | 6 | (40) |

| Chromosome 22 abnormality | 3 | (38) | 6 | (86) | 9 | (60) |

| FISH | ||||||

| TCL1A | 6 | (75) | 7 | (100) | 13 | (87) |

| Mutations | ||||||

| JAK3 | 3 | (38) | 4 | (57) | 7 | (47) |

| JAK1 | 2 | (25) | 1 | (14) | 3 | (20) |

| STAT5B | 3 | (38) | — | — | 3 | (20) |

| BCOR | — | — | 2 | (29) | 2 | (13) |

| BRAF | 1 | (12) | 1 | (14) | 2 | (13) |

| TP53 | 1 | (12) | — | — | 1 | (7) |

| Characteristic . | Front line (n = 8) . | Relapsed (n = 7) . | Total (N = 15) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytogenetics | ||||||

| Complex | 4 | (50) | 6 | (86) | 10 | (67) |

| Diploid | 3 | (38) | — | — | 3 | (20) |

| Chromosome 14 abnormality∗ | 5 | (63) | 6 | (86) | 11 | (73) |

| inv14 | 3 | (38) | 5 | (71) | 8 | (53) |

| Translocations 14 | 2 | (25) | 2 | (29) | 4 | (27) |

| Monosomy X | 3 | (38) | 2 | (29) | 5 | (33) |

| t(X;14)(q28;q11) | 2 | (25) | — | — | 2 | (13) |

| Chromosome 8 abnormality | 5 | (63) | 2 | (29) | 7 | (47) |

| Chromosome 11 abnormality | 4 | (50) | 5 | (71) | 9 | (60) |

| Chromosome 12 abnormality | 1 | (12) | 2 | (29) | 3 | (20) |

| Chromosome 13 abnormality | 3 | (38) | 3 | (43) | 6 | (40) |

| Chromosome 22 abnormality | 3 | (38) | 6 | (86) | 9 | (60) |

| FISH | ||||||

| TCL1A | 6 | (75) | 7 | (100) | 13 | (87) |

| Mutations | ||||||

| JAK3 | 3 | (38) | 4 | (57) | 7 | (47) |

| JAK1 | 2 | (25) | 1 | (14) | 3 | (20) |

| STAT5B | 3 | (38) | — | — | 3 | (20) |

| BCOR | — | — | 2 | (29) | 2 | (13) |

| BRAF | 1 | (12) | 1 | (14) | 2 | (13) |

| TP53 | 1 | (12) | — | — | 1 | (7) |

Data presented as n (%) or median (range).

Patients may be counted more than once.

Cytogenetic and mutation patterns in the study population. Oncoplot demonstrating (A) cytogenetic characteristics and (B) NGS and FISH results of the study population prior to treatment initiation.

Cytogenetic and mutation patterns in the study population. Oncoplot demonstrating (A) cytogenetic characteristics and (B) NGS and FISH results of the study population prior to treatment initiation.

Efficacy

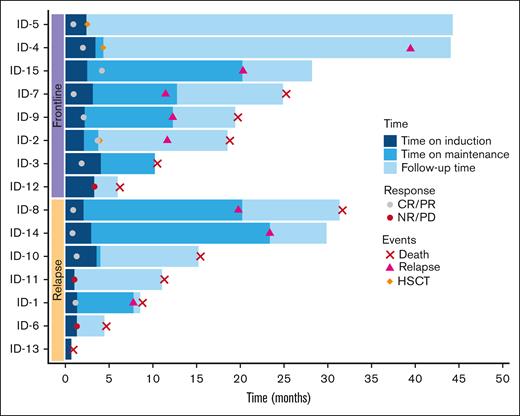

Although no objective responses were observed in white blood cells or lymph node reduction on physical examination during the 2-week window of itacitinib monotherapy, patients experienced an improvement in B-symptoms, splenomegaly, and rash. Overall, 11 (73%) of 15 patients achieved a response, including CR in 7 patients (47%) and PR in 4 patients (27%). Among the 8 frontline patients, the ORR was 88% including CR in 4 (50%) and PR in 3 (38%). The ORR in the R/R group was 57% including 3 patients (43%) who achieved a CR and 1 patient (14%) who achieved a PR (Table 3). All 7 patients who achieved a CR were MRD negative in the bone marrow by MFC. The median number of cycles administered was 4 (1-25) and median time to best response was 1 cycle (range, 1-4). Frontline patients received a greater number of cycles (median: 8 [range, 2-21]) compared with R/R patients (median 4 [range, 1-25]). Six patients (75%) in the frontline cohort received maintenance with single-agent itacitinib for a median of 9 (range, 2-19) additional cycles. Four (57%) patients in the R/R cohort received itacitinib maintenance for a median of 14 additional cycles (range, 1-23). One patient in the frontline and 2 in the R/R cohort did not respond to therapy. Three frontline patients proceeded to allogeneic SCT. Two of these transplanted patients are still alive with OS extending beyond 44 months. Among the remaining 8 responders, allogeneic SCT was not pursued because of age or other comorbidities (n = 3), patient preference (n = 2), and donor availability (n = 2). One patient in the relapsed cohort was treated postallogeneic SCT. Figure 2 presents the clinical course of study patients in a swimmer plot.

Response assessment

| Response and Treatment Outcome . | Front line (n = 8) . | Relapsed (n = 7) . | Total (N = 15) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best response | ||||||

| Complete remission (CR)∗, n (%) | 6 | (75) | 3 | (43) | 9 | (60) |

| Partial remission (PR), n (%) | 1 | (13) | 1 | (14) | 2 | (13) |

| ORR, n (%) | 7 | (88) | 4 | (57) | 11 | (73) |

| NR | ||||||

| Died, n (%) | — | — | 1 | (14) | 1 | (7) |

| NR, n (%) | 1 | (13) | 2 | (29) | 3 | (20) |

| Total | 1 | (13) | 3 | (43) | 4 | (27) |

| Allogeneic SCT | 3 | (38) | 0 | 0 | 3 | (20) |

| Treatment cycles | ||||||

| Total cycles | 8 | (2-21) | 4 | (1-25) | 4 | (1-25) |

| Combination cycles | 2 | (2-4) | 2 | (1-3) | 2 | (1-4) |

| Itacitinib maintenance cycles† | 9 | (2-19) | 14 | (1-23) | 9 | (1-23) |

| Time to best response, mo | 2 | (0.9-4.1) | 1 | (0.8-1.3) | 1.3 | (0.8-4.1) |

| Time to MRD-negativity, mo | 2 | (0.8-7.5) | 0.8 | (0.8-1.2) | 1.2 | (0.8-7.5) |

| Response and Treatment Outcome . | Front line (n = 8) . | Relapsed (n = 7) . | Total (N = 15) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best response | ||||||

| Complete remission (CR)∗, n (%) | 6 | (75) | 3 | (43) | 9 | (60) |

| Partial remission (PR), n (%) | 1 | (13) | 1 | (14) | 2 | (13) |

| ORR, n (%) | 7 | (88) | 4 | (57) | 11 | (73) |

| NR | ||||||

| Died, n (%) | — | — | 1 | (14) | 1 | (7) |

| NR, n (%) | 1 | (13) | 2 | (29) | 3 | (20) |

| Total | 1 | (13) | 3 | (43) | 4 | (27) |

| Allogeneic SCT | 3 | (38) | 0 | 0 | 3 | (20) |

| Treatment cycles | ||||||

| Total cycles | 8 | (2-21) | 4 | (1-25) | 4 | (1-25) |

| Combination cycles | 2 | (2-4) | 2 | (1-3) | 2 | (1-4) |

| Itacitinib maintenance cycles† | 9 | (2-19) | 14 | (1-23) | 9 | (1-23) |

| Time to best response, mo | 2 | (0.9-4.1) | 1 | (0.8-1.3) | 1.3 | (0.8-4.1) |

| Time to MRD-negativity, mo | 2 | (0.8-7.5) | 0.8 | (0.8-1.2) | 1.2 | (0.8-7.5) |

Data presented as n (%) or median (range).

mo: months; MRD, measurable residual disease; NR, no response; ORR: overall response rate.

All achieved minimal residual disease negativity.

Among the 6 frontline and 4 relapsed patients who received maintenance therapy.

Swimmer plot for clinical course of study participants. Swimmer plot showing individual patient’s clinical course since initiation of treatment on study including patient cohort, timing of CR, PR or NR/PD as well as time of relapse, HSCT, or death. Induction phase indicates duration of combination therapy with alemtuzumab and itacitinib. Maintenance indicates duration of itacitinib maintenance after conclusion of combination therapy. CR, complete remission; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; ID: patient number; NR, no response; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial remission.

Swimmer plot for clinical course of study participants. Swimmer plot showing individual patient’s clinical course since initiation of treatment on study including patient cohort, timing of CR, PR or NR/PD as well as time of relapse, HSCT, or death. Induction phase indicates duration of combination therapy with alemtuzumab and itacitinib. Maintenance indicates duration of itacitinib maintenance after conclusion of combination therapy. CR, complete remission; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; ID: patient number; NR, no response; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial remission.

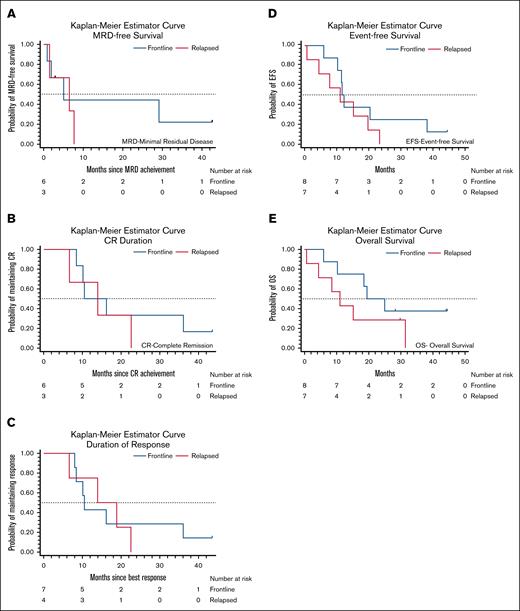

Median EFS was 11.6 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 6-19.7) and median OS was 18.6 months (95% CI, 6-31.4) for the entire cohort. Among the frontline patients, median EFS was 11.6 months (95% CI, 6-38.1) and median OS was 19.5 months (95% CI, 6 to not estimable [NA]) compared to a median EFS of 11.1 months (95% CI, 0.7-19.7) and median OS of 11.1 months (95% CI, 0.7 to NA) for R/R patients (Table 4; Figure 3). Median MRD-free survival was 5 months (95% CI, 0.9 to NA) in the frontline setting and 6.5 months (95% CI, 1.5 to NA) in the R/R setting. Frontline patients had a median CR duration and DOR of 10.5 months, whereas median CR duration and DOR were 13.9 months for R/R patients.

Survival analysis

| Survival times . | Front line . | Relapsed . | Total . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n . | Median . | (95% CI) . | n . | Median . | (95% CI) . | n . | Median . | (95% CI) . | |

| MRD-FS | 6 | 5.0 | (0.9 to NA) | 3 | 6.5 | (1.5 to NA) | 9 | 6.5 | (0.9-29.2) |

| CR durability | 6 | 10.5 | (8.4 to NA) | 3 | 13.9 | (6.6 to NA) | 9 | 13.9 | (6.6-36.1) |

| DOR | 7 | 10.5 | (8-36.1) | 4 | 13.9 | (6.6 to NA) | 11 | 13.9 | (8-22.6) |

| EFS | 8 | 11.6 | (6-38.1) | 7 | 11.1 | (0.7-19.7) | 15 | 11.6 | (6-19.7) |

| OS | 8 | 19.5 | (6 to NA) | 7 | 11.1 | (0.7 to NA) | 15 | 18.6 | (6-31.4) |

| Survival times . | Front line . | Relapsed . | Total . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n . | Median . | (95% CI) . | n . | Median . | (95% CI) . | n . | Median . | (95% CI) . | |

| MRD-FS | 6 | 5.0 | (0.9 to NA) | 3 | 6.5 | (1.5 to NA) | 9 | 6.5 | (0.9-29.2) |

| CR durability | 6 | 10.5 | (8.4 to NA) | 3 | 13.9 | (6.6 to NA) | 9 | 13.9 | (6.6-36.1) |

| DOR | 7 | 10.5 | (8-36.1) | 4 | 13.9 | (6.6 to NA) | 11 | 13.9 | (8-22.6) |

| EFS | 8 | 11.6 | (6-38.1) | 7 | 11.1 | (0.7-19.7) | 15 | 11.6 | (6-19.7) |

| OS | 8 | 19.5 | (6 to NA) | 7 | 11.1 | (0.7 to NA) | 15 | 18.6 | (6-31.4) |

CR, complete remission; DOR: duration of response; EFS: event-free survival; MRD-FS, measurable residual disease–free survival; OS: overall survival.

Remission duration and survival outcomes according to treatment setting. (A) Survival from time of obtaining MRD negativity among frontline and relapsed patients who achieved MRD-negative CR. (B) CR duration among frontline and relapsed patients who achieved CR and (C) DOR among those who achieved a PR or CR. (D) EFS and (E) OS of all frontline and relapsed patients treated on study.

Remission duration and survival outcomes according to treatment setting. (A) Survival from time of obtaining MRD negativity among frontline and relapsed patients who achieved MRD-negative CR. (B) CR duration among frontline and relapsed patients who achieved CR and (C) DOR among those who achieved a PR or CR. (D) EFS and (E) OS of all frontline and relapsed patients treated on study.

Safety

AEs observed with the combination of itacitinib and alemtuzumab were most commonly grade 1 to 2, and no AE had an incidence of >10% (Table 5). No unexpected toxicities were observed with the addition of itacitinib to alemtuzumab. The most common AE observed included rash/skin disorders (8%), lung infection (5%), rigor/chills (5%), dyspnea (5%), and pain (5%). Rigor/chills, dyspnea, and pain were infusion-related reactions observed with alemtuzumab administration. The incidence of grade ≥3 AE was 15%. The most common grade ≥3 AE was lung infection (5%). Of interest, CMV reactivation occurred in 2 patients without evidence of CMV disease, and pneumonia due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Pn jirovecii, and parainfluenza occurred in 1 patient each. One additional patient developed a probable fungal pneumonia because of Aspergillus spp. Alemtuzumab was held in the 2 patients with CMV reactivation and 1 patient with Pn jirovecii pneumonia in the setting of CR, and the patients were transitioned to itacitinib maintenance. Two deaths occurred while on protocol including 1 R/R patient during cycle 1 because of acute respiratory distress syndrome in the setting of active disease, and 1 patient (82 years old) after 11 cycles on protocol because of an unknown cause while in sustained response.

AE

| Event . | Grade 1 . | Grade 2 . | Grade 3 . | Grade 4 . | Grade 5 . | Total . | (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rash/skin disorders | 8 | 3 | 1 | — | — | 12 | (8) |

| Lung infection | — | — | 7 | 1 | — | 8 | (5) |

| Rigor/chills | 6 | 2 | — | — | — | 8 | (5) |

| Dyspnea | 6 | — | 1 | — | — | 7 | (5) |

| Pain, unspecified | 6 | 1 | — | — | — | 7 | (5) |

| Eye disorders, other blurry vision | 6 | — | — | — | — | 6 | (4) |

| Headache (intermittent) | 5 | 1 | — | — | — | 6 | (4) |

| Nausea | 5 | 1 | — | — | — | 6 | (4) |

| Constipation | 5 | — | — | — | — | 5 | (3) |

| Edema limbs | 4 | 1 | — | — | — | 5 | (3) |

| Cough | 4 | — | — | — | — | 4 | (3) |

| Hyperkalemia | 3 | 1 | — | — | — | 4 | (3) |

| Infection and infestation, unspecified | — | 2 | 2 | — | — | 4 | (3) |

| Oral mucositis | 3 | — | 1 | — | — | 4 | (3) |

| Vomiting | 4 | — | — | — | — | 4 | (3) |

| Allergic reaction | — | 1 | 2 | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 3 | — | — | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase elevation | 2 | 1 | — | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| Bruising | 3 | — | — | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| Creatinine elevation | 2 | — | — | 1 | — | 3 | (2) |

| Diarrhea | 3 | — | — | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| Dizziness (intermittent) | 3 | — | — | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| Dysuria | 2 | 1 | — | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| Fall | 2 | — | 1 | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 2 | — | 1 | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders, unspecified | 3 | — | — | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| Hypokalemia | 2 | 1 | — | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders, unspecified | 3 | — | — | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| Sinus bradycardia | 3 | — | — | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| Urinary frequency | 3 | — | — | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| CMV viremia | — | — | 2 | — | — | 2 | (1) |

| Pruritis/itching (intermittent) | — | 2 | — | — | — | 2 | (1) |

| Urinary tract infection | — | 2 | — | — | — | 2 | (1) |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | — | — | — | — | 1 | 1 | (1) |

| Backache (intermittent) | 1 | — | — | — | — | 1 | (1) |

| Diaphoresis | 1 | — | — | — | — | 1 | (1) |

| Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage | — | — | 1 | — | — | 1 | (1) |

| Hives with itching | — | — | 1 | — | — | 1 | (1) |

| Hypotension (intermittent) | 1 | — | — | — | — | 1 | (1) |

| Myalgia | — | 1 | — | — | — | 1 | (1) |

| Numbness (peripheral neuropathy) | — | 1 | — | — | — | 1 | (1) |

| Total | 104 | 22 | 20 | 2 | 1 | 149 | (100) |

| Event . | Grade 1 . | Grade 2 . | Grade 3 . | Grade 4 . | Grade 5 . | Total . | (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rash/skin disorders | 8 | 3 | 1 | — | — | 12 | (8) |

| Lung infection | — | — | 7 | 1 | — | 8 | (5) |

| Rigor/chills | 6 | 2 | — | — | — | 8 | (5) |

| Dyspnea | 6 | — | 1 | — | — | 7 | (5) |

| Pain, unspecified | 6 | 1 | — | — | — | 7 | (5) |

| Eye disorders, other blurry vision | 6 | — | — | — | — | 6 | (4) |

| Headache (intermittent) | 5 | 1 | — | — | — | 6 | (4) |

| Nausea | 5 | 1 | — | — | — | 6 | (4) |

| Constipation | 5 | — | — | — | — | 5 | (3) |

| Edema limbs | 4 | 1 | — | — | — | 5 | (3) |

| Cough | 4 | — | — | — | — | 4 | (3) |

| Hyperkalemia | 3 | 1 | — | — | — | 4 | (3) |

| Infection and infestation, unspecified | — | 2 | 2 | — | — | 4 | (3) |

| Oral mucositis | 3 | — | 1 | — | — | 4 | (3) |

| Vomiting | 4 | — | — | — | — | 4 | (3) |

| Allergic reaction | — | 1 | 2 | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 3 | — | — | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase elevation | 2 | 1 | — | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| Bruising | 3 | — | — | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| Creatinine elevation | 2 | — | — | 1 | — | 3 | (2) |

| Diarrhea | 3 | — | — | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| Dizziness (intermittent) | 3 | — | — | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| Dysuria | 2 | 1 | — | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| Fall | 2 | — | 1 | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 2 | — | 1 | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders, unspecified | 3 | — | — | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| Hypokalemia | 2 | 1 | — | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders, unspecified | 3 | — | — | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| Sinus bradycardia | 3 | — | — | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| Urinary frequency | 3 | — | — | — | — | 3 | (2) |

| CMV viremia | — | — | 2 | — | — | 2 | (1) |

| Pruritis/itching (intermittent) | — | 2 | — | — | — | 2 | (1) |

| Urinary tract infection | — | 2 | — | — | — | 2 | (1) |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | — | — | — | — | 1 | 1 | (1) |

| Backache (intermittent) | 1 | — | — | — | — | 1 | (1) |

| Diaphoresis | 1 | — | — | — | — | 1 | (1) |

| Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage | — | — | 1 | — | — | 1 | (1) |

| Hives with itching | — | — | 1 | — | — | 1 | (1) |

| Hypotension (intermittent) | 1 | — | — | — | — | 1 | (1) |

| Myalgia | — | 1 | — | — | — | 1 | (1) |

| Numbness (peripheral neuropathy) | — | 1 | — | — | — | 1 | (1) |

| Total | 104 | 22 | 20 | 2 | 1 | 149 | (100) |

No patients required dose reduction of itacitinib or alemtuzumab and no dose limiting toxicity was observed with itacitinib dosed at 200 mg once daily in combination with alemtuzumab. Four patients received a concomitant strong CYP3A4 inhibitor while they were in the study, therefore the dose of itacitinib was reduced to 100 mg once daily during the time of coadministration. One patient discontinued treatment after completing 4 cycles because of patient preference.

Discussion

Owing to the rarity of the disease, therapeutic progress for T-PLL has proceeded at a modest pace. Preclinical studies have uncovered recurrent genomic aberrancies in T-PLL that may play an important role in the pathogenesis of the disease, but translating these into clinical practice has been challenging. T-PLL is a disease with profound cytokine-drive manifestations, attributed to the underlying JAK-STAT pathway activation. In this phase 1B pilot study, we sought to target the aberrantly activated JAK-STAT signaling axis with the JAK1 inhibitor itacitinib. We report here the safety and efficacy of the combination of itacitinib with alemtuzumab in patients with T-PLL. The addition of itacitinib 200 mg by mouth once daily to standard alemtuzumab administration, 30 mg IV 3 times weekly, was found to be safe and tolerable without any excess toxicity or requirement for dose reduction. Itacitinib was well tolerated, as observed in all patients during their lead-in monotherapy period, and then further highlighted by the 10 patients who proceeded with itacitinib maintenance for a median of 9 cycles beyond the initial combination cycles with alemtuzumab. The majority of safety events observed were grade 1 to 2 and were most commonly related to underlying disease (ie, rash/skin disorders) or infusion-related reactions with alemtuzumab (rigor/chills, dyspnea, and pain). As anticipated with the use of alemtuzumab, the most common grade 3 AEs were related to infection. Given the low incidence of opportunistic infections, the addition of itacitinib did not appear to increase the infection risk overall. Routine antimicrobial prophylaxis, including Pn jirovecii prophylaxis, was administered to all patients throughout the duration of treatment.

Although our study was small in size with only 15 patients treated, our cohort is representative of a typical T-PLL population, including complex karyotype observed in 67%, chromosome 14 abnormalities in 74%, and TCL1A gene rearrangement in 87% of patients. The regimen demonstrated an ORR of 73%, including an ORR of 88% among treatment-naïve patients and 57% in patients with R/R disease. All 7 patients who achieved a CR also achieved MRD-negativity by MFC. Clinical trial data with alemtuzumab has reported an ORR of 91% in the frontline setting,26 however more contemporary analyses have demonstrated ORR of 81%27 and 74%28 in single-institution and multicenter reports, respectively. With the addition of pentostatin, an improved ORR of 85% has been reported.28 Among frontline and R/R patients combined, an ORR of 69% was observed with alemtuzumab combined with pentostatin4 and 92% with the addition of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone to alemtuzumab.6 Although these results included both frontline and R/R patients, very few relapsed patients had received prior treatment with alemtuzumab, compared with 86% of our R/R cohort. Among patients receiving second-line therapy, retreatment with alemtuzumab results in an ORR of 46%, compared with 44% with pentostatin and 25% with ruxolitinib-based regimens.28 Our study also evaluated MRD by MFC in patients achieving remission and found it to be feasible with good sensitivity in our routine clinical laboratory. MRD-negativity was achieved in all patients achieving CR. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic evaluation of MRD in remission in patients with T-PLL. Although our cohort was too small to determine the prognostic impact of achieving MRD-negativity, this should be routinely implemented and explored with future studies.

Use of itacitinib, a selective rather than pan-JAK inhibitor is advantageous because of its lack of myelosuppressive effects and suppression of cytokine signaling including IL-6, IL-2, tumor necrosis factor-α and interferon-γ, improving symptom burden without adding additional toxicity. Itacitinib led to a noticeable improvement in B-symptoms and blunting of the clinical manifestations of cytokine storm and was safely continued in patients with infectious complications. The observation of a reduction in severe B-symptoms among patients with T-PLL treated with itacitinib was novel and clinically significant, quickly reducing disease-related morbidity in the majority of patients treated on study. Most patients with progressive T-PLL experience fatigue, fevers, night sweats, rash, worsening edema, and effusions related to capillary leak. Although these signs and symptoms are attributed to the aberrantly activated cytokine signaling associated with the disease, the relatively dramatic improvement in these symptoms upon initiation of the JAK1 inhibitor was unexpected and therefore not objectively measured. This highlights the importance of developing tools to evaluate patient-reported outcomes and symptom burden, similar to symptom-assessment in myeloproliferative neoplasms, and including them prospectively in therapeutic trials as well as in response criteria for T-PLL. Resolution of constitutional symptoms has similarly been reported in a R/R patient with T-PLL treated with tofacitinib and ruxolitinib.16 Suppression of cytokine signaling by the JAK inhibitors, leading to symptom burden improvement, makes these agents valuable tools to add on to an otherwise effective therapy.

Although response rates for newly diagnosed patients are high, survival outcomes remain poor in patients with T-PLL. Treatment with alemtuzumab and itacitinib resulted in a median EFS and OS of 11.6 months and 19.5 months, respectively, in frontline patients. Among the R/R patients, median EFS and OS was 11.1 months. Dearden et al reported a 12-month EFS rate of 67% and 48-month OS rate of 37% among 32 frontline patients treated with alemtuzumab, 50% of whom received an allogeneic SCT.26 Larger, retrospective analyses have reported a median EFS of 11 to 12 months and OS of 15 to 18 months with alemtuzumab in the frontline setting.27,28 Even with the addition of chemotherapy such as pentostatin or fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone, median OS still remains no longer than ∼17 months.4,6 Among relapsed patients, a 12-month PFS rate of 26% and 48-month OS rate of 18% were observed in a pilot study with alemtuzumab.26 Allogeneic SCT has been shown to improve EFS and OS in patients with T-PLL.28 Three (38%) of 8 frontline patients (20% overall) in our cohort proceeded to allogeneic SCT, 2 of whom were alive >44 months after treatment initiation. This reinforces the benefit of allogeneic SCT in the frontline setting. Despite the majority of patients in the study not receiving allogeneic SCT, the median OS in this pilot study exceeded what would be expected in treatment-naïve patients. Both median EFS and OS were improved compared to what has been reported in the relapsed setting, particularly in a cohort where 86% of patients previously received treatment with alemtuzumab.27 A novel component of this trial was the use of postremission “maintenance” therapy with itacitinib monotherapy, something that has not been previously explored in T-PLL. The goal was to safely provide a potentially longer remission duration and OS among patients who were unable to proceed to SCT. Among the 5 frontline patients who did not proceed to SCT, 4 received itacitinib maintenance for a median of 10 courses and experienced an EFS and OS of ∼11.6 and 19.8 months, respectively. Four R/R patients received maintenance therapy for a median of 14 cycles, resulting in an EFS and OS of ∼15.4 months, potentially contributing to the prolonged EFS of 11 months observed among relapsed patients overall. These preliminary data suggest a possible signal of activity using JAK inhibition in this setting that warrants further evaluation in larger cohorts. Itacitinib is an ideal agent for continuous therapy because of its favorable side effect profile, oral administration, and positive impact on symptom burden. At minimum, the concept of active postremission therapy (including post SCT) should be further explored in patients with T-PLL in remission, given the short remission duration and high propensity to relapse.

As a JAK1 inhibitor, itacitinib activity may be anticipated in cases with activating JAK1 mutations, activating IL2GR mutations, and potentially in patients with JAK3 mutations by function of its heterodimerization with JAK1. Of 15 patients, a JAK3 mutation was detected in 47%, and a JAK1 or STAT5B mutation was detected in 20% each prior to initiating therapy. Because of our limited number of patients, we were unable to correlate a mutational profile with response or outcomes.

Our study introduces the concept of combining a novel targeted agent, the JAK1 inhibitor itacitinib with alemtuzumab. No new safety signals were observed with this combination and the majority of AEs reported were grade 1 to 2. This study was the first to evaluate maintenance therapy in T-PLL, a disease otherwise characterized by a lack of remission durability. Future studies incorporating JAK inhibitors as well as other targeted agents in patients with T-PLL are warranted.

Acknowledgment

This clinical trial was supported by research funding from Incyte Corporation.

Authorship

Contribution: T.M.K. and H.K. were responsible for study conceptualization, investigation, validation, and review and editing of the manuscript; T.M.K., A.J., and C.R.R. were responsible for data collection, data analysis and interpretation, and review and editing of the manuscript; T.M.K., A.B., F.R., E.J., G.B., N.S., G.M.-B., A.E.Q., J.B., A.F., W.W., C.H., and H.K. were responsible for provision of study materials or patients, data analysis and interpretation, and review and editing of the manuscript; and W.Q. was responsible for data curation, formal analysis, study methodology, validation, and review and editing of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: T.M.K. has been a consultant for AbbVie, Agios, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Genentech, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Servier, and PinotBio; has received research funding from AbbVie, BMS, Genentech, Incyte Corporation, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Cellenkos, Ascentage Pharma, GenFleet Therapeutics, Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca, Amgen, Cyclacel Pharmaceuticals, DeltaFly Pharma, Iterion Therapeutics, GlycoMimetics, and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals; and has received honoraria from Astex Pharmaceuticals. F.R. has received research funding from Prelude, Amgen, Xencor, Celgene/BMS, AbbVie, Astellas, Biomea fusion, and Astex/Taiho; honoraria from Amgen, Celgene/BMS, AbbVie, Astellas, and Biomea Fusion; consultancy fees from Celgene/BMS, AbbVie, and Astellas; and has membership on an entity's board of directors or advisory committees for Astex/Taiho. E.J. has received personal fees from AbbVie, Adaptative Biotechnologies, Amgen, Autolus, Ascentage, Astex/Taiho, BMS, Genentech, Novartis, Takeda, Pfizer, TargetRx, and Terns. G.B. has received research funding from Astex Pharmaceuticals, Ryvu, and PTC Therapeutics; has membership on an entity's board of directors or advisory committees for Pacylex, Novartis, Cytomx, and Bio Ascend; and has received consultancy fees from Catamaran Bio, AbbVie, PPD Development, Protagonist Therapeutics, and Janssen. N.S. has received research funding from Astellas and Stemline therapeutics; honoraria from Amgen; and consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Novartis, Pfizer, and Takeda. G.M.-B. has received research funding from Takeda and Rigel. J.B. has received research funding from Pharmacyclics, BeiGene, AstraZeneca, and AbbVie; and honoraria from Janssen. W.W. has received research funding from Kite, Gilead Sciences, Novartis, GSK, Genentech, Inc, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Loxo Oncology, Juno Therapeutics, Acerta Pharma, Pharmacyclics LLC, AbbVie, Cyclacel Pharmaceuticals Inc, Oncternal Therapeutics, Accutar Biotechnology, Numab Therapeutics, Eli Lilly, Nurix Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, BMS, and Janssen; and serves as the Chair for the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines (chronic lymphocytic leukemia [CLL]). H.K. has received honoraria and/or consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Ascentage, Ipsen Biopharmaceuticals, Kahr Medical, Novartis, Pfizer, Shenzhen TargetRx, Stemline, and Takeda; and grants (paid to institution) from AbbVie, Amgen, Ascentage, BMS, Daiichi-Sankyo, Immunogen, and Novartis. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Tapan M. Kadia, Division of Cancer Medicine, Department of Leukemia, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX, 77030; email: tkadia@mdanderson.org.

References

Author notes

Deidentified data may be made available to qualified clinical investigators on an individual basis after discussion with the corresponding author, Tapan M. Kadia (tkadia@mdanderson.org).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.