Key Points

A symptom-adapted PA intervention during intensive induction is feasible for older adults with AML.

A PA intervention during induction chemotherapy may attenuate decline in function but requires further study.

Visual Abstract

Interventions to maintain physical function during treatment may improve outcomes for older adults with acute myeloid leukemia (AML). We tested the feasibility of a randomized physical activity (PA) intervention among older adults (aged ≥60 years) receiving induction chemotherapy for newly diagnosed AML, and estimated the effect on physical function, quality of life (QOL), and symptoms. Intervention participants were offered PA sessions 5 days per week, tailored daily to symptoms during the induction hospitalization, along with weekly behavioral counseling sessions that continued monthly by phone for 6 months. The primary outcome was feasibility (recruitment, retention, and participation). The key secondary outcome of interest was the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB). SPPB score was assessed at baseline, weekly during hospitalization, and at 3 and 6 months. Among 96 eligible patients, 70 enrolled (mean age, 72.1 ± 6.3 years [range, 60-88]). Primary feasibility targets were met, with a recruitment rate of 72%, adherence of 74%, and average participation of 3 sessions per week. Among survivors, the retention rates were 96% and 95% at 3 (n = 51/53) and 6 (n = 42/44) months, respectively. In exploratory analyses, SPPB scores were maintained or improved in 38% of intervention participants vs 25% of controls at end of induction (n = 66; P = .21). There were no differences between groups in QOL or symptoms. A PA intervention with behavioral counseling during induction was feasible for older adults receiving intensive therapy for AML. This trial was registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov as #NCT01519596.

Introduction

Despite expanding treatment options for older adults with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), outcomes remain poor.1-3 Older adults are at high risk for side effects, including decline in physical function during and after treatment,4,5 which can impair quality of life (QOL) and jeopardize ongoing therapies needed for disease control. Developing interventions to maintain or improve physical function has the potential to improve treatment tolerance, QOL, and eligibility for therapies.6-10 Strategies to enhance resilience have the potential to expand access to curative-intent therapy for a larger proportion of older adults.

Physical performance (assessed by the Short Physical Performance Battery [SPPB]) serves as a marker of physical vulnerability in intensively treated older adults with AML. Specifically, SPPB is predictive of survival at diagnosis11 and declines during induction chemotherapy,5,12 with lower scores at the time of remission associated with shorter survival.13 We postulate that physical activity (PA) interventions designed to maintain or improve physical performance could maintain fitness during therapy and potentially translate into improved survival.

Few studies have evaluated the feasibility of conducting PA interventions among older adults receiving chemotherapy for hematologic malignancies,14,15 and only 1 study has focused on older adults receiving intensive AML therapy.8 Adapting interventions to older adults with AML, who often have concurrent comorbid conditions, functional limitations, high symptom burden, and frequent changes in clinical status, is critical to developing strategies to maximize resilience during and after treatment. Using lessons learned from prior work8 and social cognitive theory, we developed a unique symptom-adapted multimodal PA intervention.16 The design emphasized exercise sessions tailored to daily changes in symptoms during induction therapy and behavioral counseling to bolster PA self-efficacy to maintain participation. Although this study was conducted before the approval of hypomethylating and venetoclax-based therapies, issues related to therapy tolerability and loss of function persist.

Our primary objectives were to test the feasibility of conducting a randomized symptom-adapted PA intervention among older adults receiving intensive chemotherapy for newly diagnosed AML, and to estimate the size of the intervention’s effect on objectively measured physical function. Secondary objectives included describing the effects of the PA intervention on self-reported physical function, health-related QOL, and symptoms.

Methods

Study design overview

Detailed information on the methodology of this study was previously published.16 This 24-week, 2-arm, randomized controlled trial was conducted at the Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Comprehensive Cancer Center from October 2012 until February 2017. All participants provided written informed consent in accordance with the Wake Forest University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board, with protocol execution and adverse events routinely evaluated by a data safety and monitoring board.

Eligibility, recruitment, and randomization

Eligibility criteria were age ≥60 years, newly diagnosed AML with pathologic confirmation based on World Health Organization criteria, and planned intensive induction chemotherapy. Participants had to be ambulatory, without cognitive deficits (≤3 incorrect responses on the Pfeiffer Mental Status Scale), have adequate English skills to understand and complete questionnaires, and have no active medical conditions that precluded participation in PA according to the treating physician’s judgment.

Potential participants were approached in the leukemia ward for participation by a study nurse within 7 days of hospital admission or in-hospital diagnosis. Consenting patients were randomly assigned to the PA protocol or usual care in a 1:1 ratio at registration.

Intervention

The intervention was previously described and included a multimodal, tiered PA component offered 5 days per week during inpatient induction hospitalization and a behavioral counseling component offered during hospitalization with postdischarge follow-up by telephone.16

PA component

PA sessions were conducted by a trained exercise interventionist with a background in sports medicine, with training and oversight provided by a study-supported physical therapist with experience in the inpatient oncology setting. The PA intervention was designed to adapt to fluctuating symptoms to enhance opportunities for participation. A standard, intermediate, or low-intensity session was offered at each visit, with intensity collaboratively determined by the interventionist’s assessment and participant’s preference.16 Participants could move between activity tiers daily as needed to adapt to symptoms, clinical status, or preferences, focusing on safe daily regular participation rather than a required “dose” of PA.

The standard (ward-based, 40-50 minutes) session included cardiovascular, strength, flexibility, and balance training. Each session included walking within the medical ward followed by strength and flexibility exercises using resistance bands and in-room balance training.

The intermediate (room-based, 30-40 minutes) sessions were conducted when participants were unable or unwilling to leave their room, substituting an arm ergometer (hand crank cycle) for the cardiovascular component,17 followed by strength, flexibility, and balance training as described earlier.

The low-intensity sessions were performed in bed for participants who were unable or unwilling to safely perform activities out of bed (20-30 minutes), with up to 10 minutes of cardiovascular activity using the arm ergometer, and progressive strength exercises with or without resistance bands.

Behavioral counseling component

Intervention participants received an ∼30-minute behavioral counseling session weekly during hospitalization with postdischarge phone follow-up to enhance adherence and promote longer-term behavioral change. Sessions addressed perceived benefits from PA participation, self-regulatory skills for behavior change, barriers to adherence, and functional weekly goals. This information was provided to the interventionist to reinforce PA sessions. Postdischarge follow-up phone counseling (every 2 weeks for the first month, then monthly through 6 months) emphasized maintenance and adaptation to progressive functional goals. Counseling aligns with social cognitive theory by integrating self-efficacy, outcome expectation, goal setting, and self-evaluations, taking into account the dynamic nature of the environment and personal factors influencing participation and desired outcomes.

Control condition

Control participants received usual care including physical, occupational, and recreational therapy per the clinical team. Participants interacted with the study nurse weekly while hospitalized and at follow-up time points for functional and QOL outcome evaluations.

Measures/outcomes

Feasibility

The primary end points for this study were measures of feasibility (recruitment, retention, adherence, and safety) with goals prespecified in the protocol. We aimed to recruit ≥60% of consecutive eligible patients. Retention was defined as the proportion of surviving randomly assigned participants who completed scheduled follow-up assessments (3 and 6 months from baseline), with a goal of ≥85% of eligible participants completing visits. The target adherence rate was ≥70% of participation in offered PA sessions, with a goal of averaging 3 PA sessions per week during induction hospitalization. Safety was assessed using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4 to grade adverse events attributable to the study intervention. Intervention feedback was collected via survey at end of hospitalization.

Key secondary outcome: SPPB

Physical function was assessed weekly during hospitalization and at 3- and 6-month follow-up visits. Change in SPPB during induction therapy was the protocol-specified variable of interest to be used for sample size calculations for a fully powered efficacy trial. The SPPB is a composite measure consisting of a timed 4-minute walk, timed repeated chair stands, and 3 hierarchical standing balance tests, each scored from 0 to 4 (with higher score indicating better performance), with total score ranging from 0 to 12. A total score of 0 required one of the following criteria for all components: tried but unable, could not stand unassisted, not attempted because participant or examiner felt it was unsafe, or participant could not understand the instructions. Refusal to perform the test for other reasons was not scored. SPPB is predictive of survival and toxicity in AML and declines for many older adults during therapy.5,11,18,19 An accepted clinically meaningful change in SPPB is 0.5.20 In addition to analyzing SPPB as a continuous score, change in total SPPB score at the last hospitalization assessment was categorized as stable (difference of 0), improved (increase of ≥1), declined (decrease of ≥1), and always 0 (0 at each time point due to inability to perform the test). These categories were further collapsed into dichotomous groups of stable or improved vs declined (with “always 0” grouped as “declined”).

Additional secondary outcomes

Grip strength was assessed with a hydraulic hand dynamometer as a measure of upper extremity strength.21 Self-reported function was assessed using the Pepper Assessment Tool for Disability (including basic instrumental activities of daily living and mobility items).22 Higher scores indicate worse function. The Mobility Assessment Tool, a novel 10-item computer-based assessment that uses animated video clips to portray function, was also used.23

Data on QOL and symptoms were collected at baseline and 3 and 6 months. Global health-related QOL was assessed using the FACT-Leu (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Leukemia).24 The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale was used to assess depressive symptoms.22 Distress was assessed using the Distress Thermometer,22 and fatigue using the 13-item FACIT-Fatigue (Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Fatigue) scale.25 The Digit Symbol Substitution Test was used to measure attention and perceptual speed.26,27

Covariates/clinical outcomes

Information collected from the medical records included demographics, smoking status, comorbid conditions (abstracted from provider documentation or coding), AML disease characteristics,28 laboratory data, chemotherapy information, length of induction hospitalization, receipt of physical therapy during induction therapy, treatment outcomes (including complete remission [CR] and CR with incomplete count recovery), and vital status.

Statistical analysis

The sample size was based on feasibility considerations and designed to rule out a clinically relevant SPPB effect size. Specifically, with a recruitment rate of ≥68%, we would be confident that the true rate was ≥60% for this population (ie, the lower limit of a 1-sided 95% confidence interval [CI] would be 61%). We anticipated that 10 participants would die in the hospital and considered retention to be ≥75% if ≥85% of surviving participants completed the study. Furthermore, if we observed no difference in SPPB score, we aimed to rule out a possible effect size (Cohen's d) >0.5 (upper 95% CI of 0.43 for n = 60). Frequencies were used to describe recruitment and retention. All enrolled patients were included in the feasibility analyses, with retention calculated among survivors. Demographic characteristics were compared by decline status using a t test for age and χ2 test for race and sex. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study population at baseline and compared using t tests, χ2, and Fisher exact tests. Adherence was assessed by calculating the percentage of participants who declined a session, the mean and standard deviation (SD) of number of sessions, overall and by week, and the percentage of eligible sessions that were completed (adherence rate). Quantitative program evaluation data were summarized using descriptive statistics. Change from baseline over the first 4 weeks of hospitalization was examined in mixed models with a compound symmetric error structure to examine group and week effects and their interaction. At 3 and 6 months, functional measures were compared between the 2 groups using t tests. In exploratory analyses, change in SPPB category using the dichotomous variable was compared from baseline to the end of hospitalization using χ2 tests. Change in SPPB category was also evaluated among those who achieved remission to explore the benefits of the intervention among those who respond to induction therapy.

CR, 30-day mortality, falls, intensive care unit requirement, residual disease on day-14 bone marrow assessment, disposition, receipt of consolidation therapy, relapse, and receipt of bone marrow transplant were compared between groups using χ2 or Fisher exact tests. Length of stay, number of PA sessions, and number of hospitalizations among participants who survived for 6 months were summarized using median and interquartile range and compared by group using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Disposition, length of stay, and number of PA sessions were analyzed among participants who did not die during hospitalization. Overall survival was summarized using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test.

Qualitative analyses were conducted using the postintervention feedback questionnaire (n = 26). A codebook, developed by an independent researcher from the Qualitative and Patient-Reported Outcomes Shared Resource of the Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Comprehensive Cancer Center using an inductive approach, was tested on 25% of survey responses and refined. Data were coded in Microsoft Excel. Codes were not mutually exclusive; multiple codes were applied to some responses. After all responses were coded, reports were run for each code, and summarized using content analysis methodologies.29

Results

Recruitment and retention

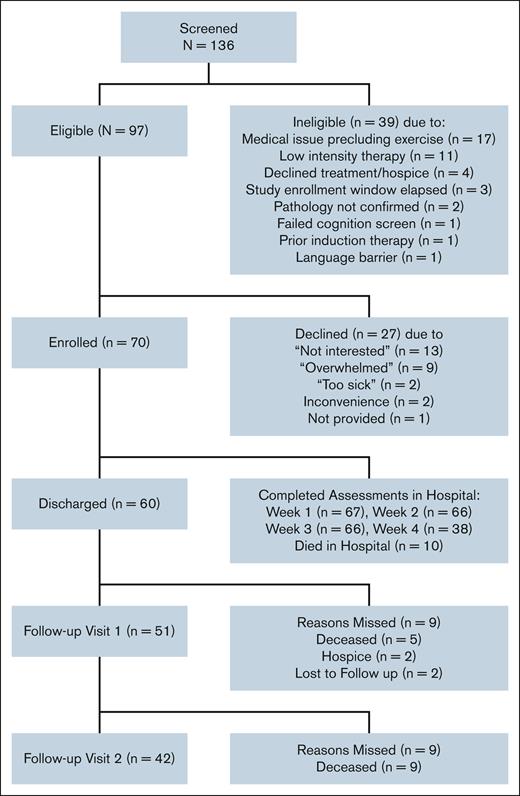

Among 136 screened consecutive patients with newly diagnosed AML aged ≥60 years, 97 met the eligibility criteria (Figure 1), and 70 enrolled. The recruitment rate was 72.1% (feasibility target >60%), with 35 participants randomly assigned to the intervention and control groups, respectively. Among those who declined participation, a common reason reported was “feeling overwhelmed.” Compared with patients who declined participation, enrolled patients trended toward older age (72.0 vs 69.5 years; P = .07), with no significant difference in race or sex (11.4% vs 3.7% non-White and 30.0% vs 44.4% female, respectively; P > 1.0 for both). Among those enrolled and eligible for 3- and 6-month follow-up, the retention rates were 96% (n = 51/53) and 95% (n = 42/44) (target ≥80%), respectively.

Cohort characteristics

Baseline characteristics of study participants stratified by randomization are presented in Table 1. The mean overall study population age was 72.1 (SD, 6.3) years. Most participants were White (88.6%) and male (70%), with slightly more than half presenting with ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) performance status of ≤1. Most had intermediate (62.3%) or poor-risk (33.3%) cytogenetics. The most common regimen was anthracycline plus cytarabine (77.1%), followed by clofarabine (16%). At diagnosis, the mean SPPB score was 7.0 (SD, 3.8), indicating physical frailty (<9) despite the low ECOG scores. Characteristics did not differ significantly between the intervention and control groups, except for more patients with diabetes in the control group. The median duration of hospitalization for induction chemotherapy was 35.4 days for the total cohort (26 days for those who died while hospitalized and 37 days for survivors).

Baseline cohort characteristics among older adults with AML enrolled in a randomized PA intervention study

| Characteristics . | Total N = 70 . | PA n = 35 . | Control n = 35 . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % or mean (SD) . | % or mean (SD) . | % or mean (SD) . | ||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, mean, y | 72.1 (6.3) | 71.8 (6.4) | 72.3 (6.2) | .72 |

| 60-69 | 34.3 | 28.6 | 40.0 | |

| 70-79 | 54.3 | 60.0 | 48.6 | |

| ≥80 | 11.4 | 11.4 | 11.4 | |

| Sex (male) | 70 | 74.3 | 65.7 | .43 |

| Race (White) | 88.6 | 82.9 | 94.3 | .26 |

| Married | 65.7 | 68.6 | 62.9 | .61 |

| Education level (n = 68) | ||||

| Below high school | 12.9 | 17.1 | 8.6 | .50 |

| High school | 30.0 | 31.4 | 28.6 | |

| College/above | 57.1 | 51.4 | 62.9 | |

| Behaviors | ||||

| Self-reported PA (≥3 d/wk) | ||||

| Mild | 38.2 | 37.1 | 39.4 | .85 |

| Moderate | 31.9 | 28.6 | 35.3 | .55 |

| Strenuous | 5.8 | 8.6 | 2.9 | .61 |

| Tobacco | .31 | |||

| Current | 10.0 | 7.1 | 5.7 | |

| Former | 57.1 | 60.0 | 54.3 | |

| Never | 32.9 | 25.7 | 40.0 | |

| Clinical | ||||

| Hemoglobin (n = 68), g/dL | 9.3 (1.6) | 9.2 (1.7) | 9.4 (1.5) | .60 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase, U/L | 522.3 (943.6) | 555.8 (686.6) | 488.7 (1154.7) | .77 |

| White cell count, ×103/μL | 17.7 (36.2) | 22.3 (46.2) | 13.1 (21.9) | .29 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.1 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.5) | 1.2 (0.5) | .81 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29.2 (6.1) | 29.6 (7.4) | 28.6 (4.4) | .47 |

| ECOG score (≤1) | 57.1 | 54.3 | 60 | .63 |

| Previous myelodysplastic syndrome | 25.7 | 20.0 | 31.4 | .27 |

| Cytogenetic risk group (n = 69) | ||||

| Favorable | 4.4 | 8.6 | 0 | .31 |

| Intermediate | 62.3 | 57.1 | 67.7 | |

| Poor | 33.3 | 34.3 | 32.3 | |

| Coronary artery disease | 24.3 | 28.6 | 20.0 | .40 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 10.0 | 14.3 | 5.7 | .43 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 34.3 | 22.9 | 45.7 | .04 |

| Congestive heart failure | 4.3 | 5.7 | 2.9 | 1.0 |

| Prior cancer | 34.3 | 34.3 | 34.3 | 1.0 |

| Renal dysfunction | 10.0 | 8.6 | 11.4 | 1.0 |

| HCT-CI | 2.0 (1.8) | 2.1 (2.0) | 2.0 (1.8) | .90 |

| Induction treatment, anthracycline + cytarabine | 77.1 | 82.9 | 71.4 | .25 |

| Geriatric assessment measures | ||||

| PAT-D (n = 62) (range, 1-5; impairment >1) at the time of treatment | 1.8 (0.7) | 1.9 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.6) | .37 |

| Activities of Daily Living subscale (n = 67) | 1.4 (0.5) | 1.4 (0.4) | 1.4 (0.5) | .96 |

| Instrumental Activities of Daily Living subscale (n = 63) | 1.6 (0.7) | 1.6 (0.8) | 1.5 (0.6) | .68 |

| Mobility subscale (n = 66) | 2.5 (1.2) | 2.7 (1.3) | 2.3 (1.2) | .13 |

| SPPB (range, 0-9; impairment <9; n = 68) | 7.0 (3.8) | 7.1 (3.7) | 6.8 (4.1) | .73 |

| SPPB score of <9 (n = 68), % | 52.9 | 54.3 | 51.5 | .82 |

| SPPB walk score (range, 0-4) | 2.5 (1.5) | 2.7 (1.5) | 2.4 (1.5) | .44 |

| SPPB balance score (range, 0-4) | 2.8 (1.5) | 2.9 (1.5) | 2.7 (1.6) | .67 |

| SPPB chair stand score (range, 0-4) | 1.7 (1.4) | 1.6 (1.3) | 1.8 (1.4) | .57 |

| MAT-SF (n = 66) | 53.1 (11.3) | 51.7 (11.1) | 54.8 (11.3) | .26 |

| Grip strength (kg) | ||||

| Male (n = 47) | 34.9 (9.5) | 33.9 (8.6) | 36.0 (10.6) | .46 |

| Female (n = 20) | 21.2 (5.4) | 23.1 (4.3) | 19.5 (5.9) | .15 |

| Distress thermometer (n = 69) | 4.6 (3.1) | 4.9 (3.1) | 4.4 (3.1) | .55 |

| CES-D (n = 69) | 12.0 (7.7) | 13.4 (8.2) | 10.5 (8.9) | .15 |

| FACT-Leu (n = 68) | 127.4 (19) | 127.5 (18.7) | 127.2 (19.7) | .95 |

| FACT-Emotional (n = 68) | 18.9 (3.5) | 18.6 (3.7) | 19.2 (3.3) | .50 |

| FACT-Functional (n = 68) | 16.6 (6.3) | 16.9 (5.9) | 16.4 (6.7) | .72 |

| FACT-G (n = 68) | 80.8 (13.0) | 80.9 (13.2) | 80.7 (12.9) | .95 |

| FACT-Physical (n = 69) | 21.6 (5.0) | 21.3 (5.1) | 21.9 (5.0) | .62 |

| FACT-Social (n = 69) | 23.7 (3.9) | 24.1 (4.2) | 23.3 (3.5) | .37 |

| FACT-Fatigue (n = 69) | 31.9 (11.4) | 31.9 (9.9) | 32.0 (12.9) | .97 |

| Digit symbol substitution test (n = 64) | 36.1 (13.0) | 34.4 (13.7) | 38.0 (12.2) | .27 |

| Characteristics . | Total N = 70 . | PA n = 35 . | Control n = 35 . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % or mean (SD) . | % or mean (SD) . | % or mean (SD) . | ||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, mean, y | 72.1 (6.3) | 71.8 (6.4) | 72.3 (6.2) | .72 |

| 60-69 | 34.3 | 28.6 | 40.0 | |

| 70-79 | 54.3 | 60.0 | 48.6 | |

| ≥80 | 11.4 | 11.4 | 11.4 | |

| Sex (male) | 70 | 74.3 | 65.7 | .43 |

| Race (White) | 88.6 | 82.9 | 94.3 | .26 |

| Married | 65.7 | 68.6 | 62.9 | .61 |

| Education level (n = 68) | ||||

| Below high school | 12.9 | 17.1 | 8.6 | .50 |

| High school | 30.0 | 31.4 | 28.6 | |

| College/above | 57.1 | 51.4 | 62.9 | |

| Behaviors | ||||

| Self-reported PA (≥3 d/wk) | ||||

| Mild | 38.2 | 37.1 | 39.4 | .85 |

| Moderate | 31.9 | 28.6 | 35.3 | .55 |

| Strenuous | 5.8 | 8.6 | 2.9 | .61 |

| Tobacco | .31 | |||

| Current | 10.0 | 7.1 | 5.7 | |

| Former | 57.1 | 60.0 | 54.3 | |

| Never | 32.9 | 25.7 | 40.0 | |

| Clinical | ||||

| Hemoglobin (n = 68), g/dL | 9.3 (1.6) | 9.2 (1.7) | 9.4 (1.5) | .60 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase, U/L | 522.3 (943.6) | 555.8 (686.6) | 488.7 (1154.7) | .77 |

| White cell count, ×103/μL | 17.7 (36.2) | 22.3 (46.2) | 13.1 (21.9) | .29 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.1 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.5) | 1.2 (0.5) | .81 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29.2 (6.1) | 29.6 (7.4) | 28.6 (4.4) | .47 |

| ECOG score (≤1) | 57.1 | 54.3 | 60 | .63 |

| Previous myelodysplastic syndrome | 25.7 | 20.0 | 31.4 | .27 |

| Cytogenetic risk group (n = 69) | ||||

| Favorable | 4.4 | 8.6 | 0 | .31 |

| Intermediate | 62.3 | 57.1 | 67.7 | |

| Poor | 33.3 | 34.3 | 32.3 | |

| Coronary artery disease | 24.3 | 28.6 | 20.0 | .40 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 10.0 | 14.3 | 5.7 | .43 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 34.3 | 22.9 | 45.7 | .04 |

| Congestive heart failure | 4.3 | 5.7 | 2.9 | 1.0 |

| Prior cancer | 34.3 | 34.3 | 34.3 | 1.0 |

| Renal dysfunction | 10.0 | 8.6 | 11.4 | 1.0 |

| HCT-CI | 2.0 (1.8) | 2.1 (2.0) | 2.0 (1.8) | .90 |

| Induction treatment, anthracycline + cytarabine | 77.1 | 82.9 | 71.4 | .25 |

| Geriatric assessment measures | ||||

| PAT-D (n = 62) (range, 1-5; impairment >1) at the time of treatment | 1.8 (0.7) | 1.9 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.6) | .37 |

| Activities of Daily Living subscale (n = 67) | 1.4 (0.5) | 1.4 (0.4) | 1.4 (0.5) | .96 |

| Instrumental Activities of Daily Living subscale (n = 63) | 1.6 (0.7) | 1.6 (0.8) | 1.5 (0.6) | .68 |

| Mobility subscale (n = 66) | 2.5 (1.2) | 2.7 (1.3) | 2.3 (1.2) | .13 |

| SPPB (range, 0-9; impairment <9; n = 68) | 7.0 (3.8) | 7.1 (3.7) | 6.8 (4.1) | .73 |

| SPPB score of <9 (n = 68), % | 52.9 | 54.3 | 51.5 | .82 |

| SPPB walk score (range, 0-4) | 2.5 (1.5) | 2.7 (1.5) | 2.4 (1.5) | .44 |

| SPPB balance score (range, 0-4) | 2.8 (1.5) | 2.9 (1.5) | 2.7 (1.6) | .67 |

| SPPB chair stand score (range, 0-4) | 1.7 (1.4) | 1.6 (1.3) | 1.8 (1.4) | .57 |

| MAT-SF (n = 66) | 53.1 (11.3) | 51.7 (11.1) | 54.8 (11.3) | .26 |

| Grip strength (kg) | ||||

| Male (n = 47) | 34.9 (9.5) | 33.9 (8.6) | 36.0 (10.6) | .46 |

| Female (n = 20) | 21.2 (5.4) | 23.1 (4.3) | 19.5 (5.9) | .15 |

| Distress thermometer (n = 69) | 4.6 (3.1) | 4.9 (3.1) | 4.4 (3.1) | .55 |

| CES-D (n = 69) | 12.0 (7.7) | 13.4 (8.2) | 10.5 (8.9) | .15 |

| FACT-Leu (n = 68) | 127.4 (19) | 127.5 (18.7) | 127.2 (19.7) | .95 |

| FACT-Emotional (n = 68) | 18.9 (3.5) | 18.6 (3.7) | 19.2 (3.3) | .50 |

| FACT-Functional (n = 68) | 16.6 (6.3) | 16.9 (5.9) | 16.4 (6.7) | .72 |

| FACT-G (n = 68) | 80.8 (13.0) | 80.9 (13.2) | 80.7 (12.9) | .95 |

| FACT-Physical (n = 69) | 21.6 (5.0) | 21.3 (5.1) | 21.9 (5.0) | .62 |

| FACT-Social (n = 69) | 23.7 (3.9) | 24.1 (4.2) | 23.3 (3.5) | .37 |

| FACT-Fatigue (n = 69) | 31.9 (11.4) | 31.9 (9.9) | 32.0 (12.9) | .97 |

| Digit symbol substitution test (n = 64) | 36.1 (13.0) | 34.4 (13.7) | 38.0 (12.2) | .27 |

CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale; FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General; HCT-CI, hematopoietic cell transplantation–specific comorbidity index; MAT-SF, Mobility Assessment Tool–short form; PAT-D, Pepper Assessment Tool for Disability.

Feasibility outcomes

The total number of potential PA sessions for intervention participants (5 per week during hospitalization) was 877. A total of 184 sessions (22%) were not administered because of medical contraindication. Of the remaining sessions for which participants were eligible, 152 sessions were declined by the participant (23%). The average number of sessions attended per participant was 14.4 (SD, 9.4), with a weekly average of 2.9 sessions (SD, 1.7) during weeks with at least 1 eligible day. The number of sessions per person per week was higher (mean, 3.7 [SD, 1.4]) when at least 5 sessions were eligible per week. The adherence rate for PA session participation was 74% (target ≥70%). Participation was lower among those who died during induction hospitalization (n = 6) compared with survivors (median, 6 vs 13 sessions), with adherence rates of 67% and 83%, respectively.

Participant intervention feedback (n = 26) was positive. Among the respondents, 88% “liked the program,” 88% “found the program helpful,” and 69% “planned to continue PA after discharge.” The types of exercise reported to be most helpful were the combination of balance/stretch bands/walking (30.8%), stretch bands alone (23%), balance alone (15.4%), and walking alone (15.4%). Qualitative feedback from open-ended questions addressed the benefits of exercise, staffing and motivation, specific exercises, challenges with participation, and suggestions/feedback. Highlights are included in supplemental Table 1 and emphasize the positive impact of exercise on physical and mental health as well as recovery, the value of staff motivation, and preference for resistance band exercises. Physical symptoms such as fatigue, disruptions from added visits, and medical issues represented challenges limiting participation.

SPPB

SPPB was the outcome variable of interest for a larger efficacy trial. Total and component SPPB scores declined significantly (indicating worse functioning) during the first 4 weeks of induction hospitalization (P < .05), without significant differences between groups during this time period (Table 2). Decline in SPPB scores during hospitalization was more pronounced among those aged ≥75 than <75 years (supplemental Table 2). SPPB scores were similar between groups among those who were evaluable at 3-month follow-up (n = 51; mean ± standard error SPPB score, 6.7 ± 0.9 in intervention vs 6.9 ± 0.8 in control group) and at 6-month follow-up (n = 42; 8.1 ± 0.9 in intervention and 8.2 ± 0.8 in control group; Table 3).

Weekly functional assessment during induction hospitalization by intervention arm

| Measures . | Intervention arm . | Baseline LSM (SE) . | Week 1 LSM (SE) . | Week 2 LSM (SE) . | Week 3 LSM (SE) . | Week 4 LSM (SE) . | P value time . | P value arm . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPPB total score (range, 0-12) | PA | 7.1 (0.7) | 6.1 (0.7) | 5.3 (0.7) | 4.5 (0.8) | 4.4 (4.4) | <.001 | .5 |

| Higher indicates better function | Usual care | 6.8 (0.7) | 5.3 (0.8); d∗ = 0.18 (−0.30 to 0.66); n = 65 | 4.1 (0.8); d = 0.26 (−0.21 to 0.74); n = 66 | 4.0 (0.8); d = 0.11 (−0.38 to 0.61); n = 59 | 4.3 (1.0); d = −0.02 (−0.56 to 0.60); n = 38 | ||

| SPPB walk score (range, 0-4) | PA | 2.7 (0.3) | 2.1 (0.3) | 1.9 (0.3) | 1.6 (0.3) | 1.6 (0.3) | <.001 | .4 |

| Higher indicates better function | Usual care | 2.4 (0.3) | 2.1 (0.3) | 1.4 (0.3) | 1.4 (0.3) | 1.4 (0.4) | ||

| SPPB balance score (range, 0-4) | PA | 2.9 (0.3) | 2.5 (0.3) | 2.2 (0.3) | 1.7 (0.3) | 1.8 (0.4) | <.001 | .5 |

| Higher indicates better function | Usual care | 2.7 (0.3) | 2.0 (0.3) | 1.7 (0.3) | 1.6 (0.3) | 2.0 (0.4) | ||

| SPPB chair stand score (range, 0-4) | PA | 1.6 (0.2) | 1.5 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.3) | <.001 | .6 |

| Higher indicates better function | Usual care | 1.8 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.3) | ||

| Grip strength | PA | 31.1 (1.7) | 30.2 (1.7) | 28.9 (1.7) | 28.6 (1.8) | 28.2 (1.9) | <.001 | .4 |

| Higher indicates better function | Usual care | 30.2 (1.7) | 28.6 (1.7) | 28.5 (1.8) | 25.8 (1.8) | 28.4 (2.1) | ||

| MAT-SF | PA | 51.7 (2.0) | 52.2 (2.0) | 50.1 (2.1) | 50.2 (2.2) | 50.4 (2.3) | .04 | .9 |

| Higher indicates better perceived function | Usual care | 53.9 (2.1) | 50.2 (2.1) | 49.5 (2.2) | 49.2 (2.4) | 50.5 (2.1) | ||

| PAT-D total score | PA | 1.9 (0.2) | 2.1 (0.2) | 2.2 (0.2) | 2.4 (0.2) | 2.1 (0.2) | <.001 | .9 |

| Higher indicates worse self-reported function | Usual care | 1.7 (0.2) | 2.1 (0.2) | 2.1 (0.2) | 2.4 (0.2) | 2.3 (0.3) | ||

| PAT-D Activities of Daily Living subscale | PA | 1.4 (0.1) | 1.6 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.2) | 1.9 (0.2) | 1.7 (0.2) | .009 | 1.0 |

| Higher indicates worse self-reported function | Usual care | 1.4 (0.1) | 1.8 (0.2) | 1.6 (0.2) | 1.8 (0.2) | 1.7 (0.2) | ||

| PAT-D Instrumental Activities of Daily Living subscale | PA | 1.6 (0.2) | 1.9 (0.2) | 2.0 (0.2) | 2.0 (0.2) | 2.1 (0.2) | .002 | .8 |

| Higher indicates worse self-reported function | Usual care | 1.5 (0.2) | 1.8 (0.2) | 1.9 (0.2) | 2.0 (0.2) | 2.2 (0.3) | ||

| PAT-D Mobility subscale | PA | 2.7 (0.2) | 3.0 (0.2) | 3.1 (0.3) | 2.9 (0.3) | 3.0 (0.3) | .01 | .7 |

| Higher indicates worse self-reported function | Usual care | 2.3 (0.2) | 2.8 (0.3) | 3.1 (0.3) | 3.2 (0.3) | 2.8 (0.4) | ||

| Digit symbol substitution test | PA | 33.9 (2.5) | 35.9 (2.5) | 35.2 (2.6) | 32.7 (2.7) | 33.2 (2.9) | .64 | .2 |

| Higher indicates better performance | Usual care | 37.2 (2.6) | 38.1 (2.6) | 40.0 (2.7) | 39.3 (2.7) | 40.0 (3.4) |

| Measures . | Intervention arm . | Baseline LSM (SE) . | Week 1 LSM (SE) . | Week 2 LSM (SE) . | Week 3 LSM (SE) . | Week 4 LSM (SE) . | P value time . | P value arm . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPPB total score (range, 0-12) | PA | 7.1 (0.7) | 6.1 (0.7) | 5.3 (0.7) | 4.5 (0.8) | 4.4 (4.4) | <.001 | .5 |

| Higher indicates better function | Usual care | 6.8 (0.7) | 5.3 (0.8); d∗ = 0.18 (−0.30 to 0.66); n = 65 | 4.1 (0.8); d = 0.26 (−0.21 to 0.74); n = 66 | 4.0 (0.8); d = 0.11 (−0.38 to 0.61); n = 59 | 4.3 (1.0); d = −0.02 (−0.56 to 0.60); n = 38 | ||

| SPPB walk score (range, 0-4) | PA | 2.7 (0.3) | 2.1 (0.3) | 1.9 (0.3) | 1.6 (0.3) | 1.6 (0.3) | <.001 | .4 |

| Higher indicates better function | Usual care | 2.4 (0.3) | 2.1 (0.3) | 1.4 (0.3) | 1.4 (0.3) | 1.4 (0.4) | ||

| SPPB balance score (range, 0-4) | PA | 2.9 (0.3) | 2.5 (0.3) | 2.2 (0.3) | 1.7 (0.3) | 1.8 (0.4) | <.001 | .5 |

| Higher indicates better function | Usual care | 2.7 (0.3) | 2.0 (0.3) | 1.7 (0.3) | 1.6 (0.3) | 2.0 (0.4) | ||

| SPPB chair stand score (range, 0-4) | PA | 1.6 (0.2) | 1.5 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.3) | <.001 | .6 |

| Higher indicates better function | Usual care | 1.8 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.3) | ||

| Grip strength | PA | 31.1 (1.7) | 30.2 (1.7) | 28.9 (1.7) | 28.6 (1.8) | 28.2 (1.9) | <.001 | .4 |

| Higher indicates better function | Usual care | 30.2 (1.7) | 28.6 (1.7) | 28.5 (1.8) | 25.8 (1.8) | 28.4 (2.1) | ||

| MAT-SF | PA | 51.7 (2.0) | 52.2 (2.0) | 50.1 (2.1) | 50.2 (2.2) | 50.4 (2.3) | .04 | .9 |

| Higher indicates better perceived function | Usual care | 53.9 (2.1) | 50.2 (2.1) | 49.5 (2.2) | 49.2 (2.4) | 50.5 (2.1) | ||

| PAT-D total score | PA | 1.9 (0.2) | 2.1 (0.2) | 2.2 (0.2) | 2.4 (0.2) | 2.1 (0.2) | <.001 | .9 |

| Higher indicates worse self-reported function | Usual care | 1.7 (0.2) | 2.1 (0.2) | 2.1 (0.2) | 2.4 (0.2) | 2.3 (0.3) | ||

| PAT-D Activities of Daily Living subscale | PA | 1.4 (0.1) | 1.6 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.2) | 1.9 (0.2) | 1.7 (0.2) | .009 | 1.0 |

| Higher indicates worse self-reported function | Usual care | 1.4 (0.1) | 1.8 (0.2) | 1.6 (0.2) | 1.8 (0.2) | 1.7 (0.2) | ||

| PAT-D Instrumental Activities of Daily Living subscale | PA | 1.6 (0.2) | 1.9 (0.2) | 2.0 (0.2) | 2.0 (0.2) | 2.1 (0.2) | .002 | .8 |

| Higher indicates worse self-reported function | Usual care | 1.5 (0.2) | 1.8 (0.2) | 1.9 (0.2) | 2.0 (0.2) | 2.2 (0.3) | ||

| PAT-D Mobility subscale | PA | 2.7 (0.2) | 3.0 (0.2) | 3.1 (0.3) | 2.9 (0.3) | 3.0 (0.3) | .01 | .7 |

| Higher indicates worse self-reported function | Usual care | 2.3 (0.2) | 2.8 (0.3) | 3.1 (0.3) | 3.2 (0.3) | 2.8 (0.4) | ||

| Digit symbol substitution test | PA | 33.9 (2.5) | 35.9 (2.5) | 35.2 (2.6) | 32.7 (2.7) | 33.2 (2.9) | .64 | .2 |

| Higher indicates better performance | Usual care | 37.2 (2.6) | 38.1 (2.6) | 40.0 (2.7) | 39.3 (2.7) | 40.0 (3.4) |

Data are reported as LSM with SE from a mixed model; all interactions were nonsignificant.

LSM, least squares mean; SE, standard error.

d = difference in terms of effect size (in number of SD), with 95% CI.

Function and patient-reported outcomes at 3 and 6 months by intervention arm

| Measures . | 3 months . | 6 months . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA (n = 24) . | Control (n = 27) . | P value . | PA (n = 20) . | Control (n = 22) . | P value . | |

| Mean (SE) . | Mean (SE) . | Mean (SE) . | Mean (SE) . | |||

| Physical function | ||||||

| SPPB (range, 0-12; impairment <9) (n=51 at 3 months; n=41 at 6 months) | 6.7 (0.9) | 6.9 (0.8) | 0.88 | 8.1 (0.9) | 8.2 (0.8) | 0.87 |

| Gait speed (m/s) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) | .66 | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | .98 |

| SPPB walk score | 2.5 (0.3) | 2.5 (0.3) | .90 | 2.9 (0.3) | 3.2 (0.3) | .49 |

| SPPB balance score | 2.5 (0.4) | 2.8 (0.3) | .53 | 2.9 (0.3) | 3.2 (0.3) | .62 |

| SPPB chair stand score | 1.8 (0.3) | 1.6 (0.3) | .62 | 2.2 (0.3) | 1.8 (0.3) | .41 |

| Grip strength (kg) (n = 44 at 3 months; n = 41 at 6 months) | ||||||

| Male | 30.5 (2.2) | 32.8 (2.2) | .48 | 30.2 (2.2) | 31.9 (2.0) | .57 |

| Female | 18.0 (3.1) | 19.0 (2.2) | .81 | 23.3 (3.8) | 16.9 (1.4) | .07 |

| PAT-D (range, 1-5; impairment >1) (n = 40 at 3 months; n = 38 at 6 months) | 2.1 (0.2) | 1.9 (0.2) | .53 | 2.0 (0.2) | 1.7 (.01) | .21 |

| Activities of Daily Living subscale (n = 47 at 3 months; n = 42 at 6 months) | 1.5 (0.1) | 1.4 (0.1) | .58 | 1.5 (0.1) | 1.5 (0.1) | .87 |

| Instrumental Activities of Daily Living subscale (n = 44 at 3 months; n = 39 at 6 months) | 2.0 (0.2) | 1.7 (0.2) | .45 | 1.7 (0.2) | 1.6 (0.2) | .68 |

| Mobility subscale (n = 45 at 3 months; n = 41 at 6 months) | 2.8 (0.3) | 2.8 (0.3) | .90 | 2.9 (0.3) | 2.3 (0.2) | .12 |

| MAT-SF (n = 46 at 3 months; n = 41 at 6 months) | 52.3 (2.8) | 50.1 (2.5) | .57 | 54.2 (2.3) | 53.7 (2.1) | .87 |

| QOL and symptoms | ||||||

| Distress thermometer (n = 46 at 3 months; n = 42 at 6 months) | 3.4 (0.6) | 2.7 (0.5) | .36 | 3.0 (0.6) | 2.6 (0.5) | .69 |

| CES-D (n = 46 at 3 months; n = 41 at 6 months) | 8.3 (1.3) | 8.2 (1.2) | .98 | 8.9 (1.6) | 8.3 (1.8) | .79 |

| FACT-Leu (n = 46 at 3 months; n = 42 at 6 months) | 129.4 (3.6) | 132.3 (3.4) | .57 | 132.4 (4.6) | 139.0 (3.6) | .31 |

| FACT-Emotional (n = 47 at 3 months; n = 42 at 6 months) | 19.0 (0.6) | 19.4 (0.6) | .60 | 19.6 (0.7) | 20.0 (0.6) | .70 |

| FACT-Functional (n = 46 at 3 months; n = 42 at 6 months) | 15.7 (1.1) | 16.2 (1.4) | .77 | 16.8 (1.3) | 19.0 (1.3) | .23 |

| FACT-G (n = 46 at 3 months; n = 42 at 6 months) | 80.9 (2.6) | 80.8 (2.4) | .98 | 81.9 (2.7) | 86.6 (2.9) | .25 |

| FACT-Physical (n = 47 at 3 months; n = 42 at 6 months) | 22.0 (1.3) | 21.6 (0.9) | .79 | 22.1 (1.2) | 22.5 (1.2) | .77 |

| FACT-Social (n = 47 at 3 months; n = 42 at 6 months) | 23.2 (0.8) | 23.6 (0.9) | .78 | 23.5 (0.9) | 25.0 (0.8) | .20 |

| FACT-Fatigue (n = 46 at 3 months; n = 42 at 6 months) | 35.6 (2.9) | 35.8 (1.8) | .96 | 37.6 (2.5) | 35.8 (2.5) | .63 |

| Digit symbol substitution test (n = 46 at 3 months; n = 42 at 6 months) | 46.8 (3.2) | 49.2 (2.8) | .57 | 44.9 (3.1) | 47.9 (4.1) | .57 |

| Measures . | 3 months . | 6 months . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA (n = 24) . | Control (n = 27) . | P value . | PA (n = 20) . | Control (n = 22) . | P value . | |

| Mean (SE) . | Mean (SE) . | Mean (SE) . | Mean (SE) . | |||

| Physical function | ||||||

| SPPB (range, 0-12; impairment <9) (n=51 at 3 months; n=41 at 6 months) | 6.7 (0.9) | 6.9 (0.8) | 0.88 | 8.1 (0.9) | 8.2 (0.8) | 0.87 |

| Gait speed (m/s) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) | .66 | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | .98 |

| SPPB walk score | 2.5 (0.3) | 2.5 (0.3) | .90 | 2.9 (0.3) | 3.2 (0.3) | .49 |

| SPPB balance score | 2.5 (0.4) | 2.8 (0.3) | .53 | 2.9 (0.3) | 3.2 (0.3) | .62 |

| SPPB chair stand score | 1.8 (0.3) | 1.6 (0.3) | .62 | 2.2 (0.3) | 1.8 (0.3) | .41 |

| Grip strength (kg) (n = 44 at 3 months; n = 41 at 6 months) | ||||||

| Male | 30.5 (2.2) | 32.8 (2.2) | .48 | 30.2 (2.2) | 31.9 (2.0) | .57 |

| Female | 18.0 (3.1) | 19.0 (2.2) | .81 | 23.3 (3.8) | 16.9 (1.4) | .07 |

| PAT-D (range, 1-5; impairment >1) (n = 40 at 3 months; n = 38 at 6 months) | 2.1 (0.2) | 1.9 (0.2) | .53 | 2.0 (0.2) | 1.7 (.01) | .21 |

| Activities of Daily Living subscale (n = 47 at 3 months; n = 42 at 6 months) | 1.5 (0.1) | 1.4 (0.1) | .58 | 1.5 (0.1) | 1.5 (0.1) | .87 |

| Instrumental Activities of Daily Living subscale (n = 44 at 3 months; n = 39 at 6 months) | 2.0 (0.2) | 1.7 (0.2) | .45 | 1.7 (0.2) | 1.6 (0.2) | .68 |

| Mobility subscale (n = 45 at 3 months; n = 41 at 6 months) | 2.8 (0.3) | 2.8 (0.3) | .90 | 2.9 (0.3) | 2.3 (0.2) | .12 |

| MAT-SF (n = 46 at 3 months; n = 41 at 6 months) | 52.3 (2.8) | 50.1 (2.5) | .57 | 54.2 (2.3) | 53.7 (2.1) | .87 |

| QOL and symptoms | ||||||

| Distress thermometer (n = 46 at 3 months; n = 42 at 6 months) | 3.4 (0.6) | 2.7 (0.5) | .36 | 3.0 (0.6) | 2.6 (0.5) | .69 |

| CES-D (n = 46 at 3 months; n = 41 at 6 months) | 8.3 (1.3) | 8.2 (1.2) | .98 | 8.9 (1.6) | 8.3 (1.8) | .79 |

| FACT-Leu (n = 46 at 3 months; n = 42 at 6 months) | 129.4 (3.6) | 132.3 (3.4) | .57 | 132.4 (4.6) | 139.0 (3.6) | .31 |

| FACT-Emotional (n = 47 at 3 months; n = 42 at 6 months) | 19.0 (0.6) | 19.4 (0.6) | .60 | 19.6 (0.7) | 20.0 (0.6) | .70 |

| FACT-Functional (n = 46 at 3 months; n = 42 at 6 months) | 15.7 (1.1) | 16.2 (1.4) | .77 | 16.8 (1.3) | 19.0 (1.3) | .23 |

| FACT-G (n = 46 at 3 months; n = 42 at 6 months) | 80.9 (2.6) | 80.8 (2.4) | .98 | 81.9 (2.7) | 86.6 (2.9) | .25 |

| FACT-Physical (n = 47 at 3 months; n = 42 at 6 months) | 22.0 (1.3) | 21.6 (0.9) | .79 | 22.1 (1.2) | 22.5 (1.2) | .77 |

| FACT-Social (n = 47 at 3 months; n = 42 at 6 months) | 23.2 (0.8) | 23.6 (0.9) | .78 | 23.5 (0.9) | 25.0 (0.8) | .20 |

| FACT-Fatigue (n = 46 at 3 months; n = 42 at 6 months) | 35.6 (2.9) | 35.8 (1.8) | .96 | 37.6 (2.5) | 35.8 (2.5) | .63 |

| Digit symbol substitution test (n = 46 at 3 months; n = 42 at 6 months) | 46.8 (3.2) | 49.2 (2.8) | .57 | 44.9 (3.1) | 47.9 (4.1) | .57 |

When estimating the effect size for the difference between the groups in weekly SPPB score during treatment, we found that the largest difference expressed in effect size was d = 0.28 (95% CI, −0.21 to 0.74; n = 66) at week 2; this did not rule out a potential effect size difference of 0.50. In exploratory analyses of categorical SPPB, a numerically higher proportion of intervention participants, compared with controls, maintained or improved their SPPB score (32% vs 19%) during induction hospitalization (P = .21; Figure 2), although this difference did not reach statistical significance. Among those who achieved remission (n = 42), 50% of intervention participants as opposed to 23% of controls maintained or improved their SPPB score during hospitalization (P < .07 compared with decline or persistent score of 0).

Percentage of participants with maintained/improved physical performance vs decline (≥1-point change in SPPB score) from baseline to end of induction by intervention arm, and remission status. (A) Overall population. (B) Remission cohort.

Percentage of participants with maintained/improved physical performance vs decline (≥1-point change in SPPB score) from baseline to end of induction by intervention arm, and remission status. (A) Overall population. (B) Remission cohort.

Secondary outcomes of function and QOL

Table 2 presents weekly functional measure scores for evaluable intervention and control participants during the induction hospitalization. All measures of physical function, including self-reported function, demonstrated significant declines from baseline to week 4 in both groups (P < .05 for all). There were no significant differences between groups in mean functional measures or Digit Symbol Substitution Test scores. Table 3 details functional and QOL measure scores at 3 and 6 months after enrollment, which were similar in the 2 groups.

Clinical outcomes

Clinical outcomes are presented by assigned group in supplemental Table 3. CR rates (also including CR with incomplete count recovery) were 60% and 66% in the intervention and control groups, respectively (P = .6), with no significant difference in early mortality. Length of stay in days (37.6 vs 40.1) and proportion discharged home after induction hospitalization (71.4% vs 65.7%) were similar between the groups (P > .5). Similar proportions of patients received consolidation therapy (60% vs 62.9%) and proceeded to stem cell transplantation (22.9% vs 25.7%) between the 2 groups (P > .5 for both). Median overall survival in the intervention arm was 11.4 vs 13.3 in the control arm (P = .2).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first randomized study to show that older adults hospitalized with AML can regularly participate in a PA intervention while receiving intensive induction chemotherapy. Our study design facilitated high recruitment and participation and demonstrated no safety concerns. This pilot can serve as a model for design of supportive care interventions specifically for older patients with multimorbidity and poor functional status, who are routinely excluded from such studies. Furthermore, our study provides preliminary data suggesting that objectively measured physical performance (SPPB) may be maintained or improved during treatment with intervention for some older adults. Maintenance of physical function is a priority for older adults and may translate into greater opportunities to tolerate disease-modifying therapy.

Few clinical trials have evaluated the feasibility of PA interventions specifically among older adults with hematologic malignancies receiving active treatment.30,31 Older adults represent a more challenging population to study because of competing comorbidities and functional impairments. However, older adults are at highest risk of functional decline during therapy and therefore may have the most to gain from interventions designed to maintain function,5 particularly in the setting of AML therapy wherein candidacy for curative treatments such as transplantation may be influenced by physical function after induction.

Randomized PA interventions in younger AML populations have shown mixed feasibility results.32 Specifically, Alibhai et al tested a home-based exercise intervention for AML survivors aged ≥40 years and demonstrated safety with a 38% recruitment rate and 28% adherence, without measurable benefits for QOL, fatigue, or physical fitness.7 Another study by Alibhai et al evaluated supervised exercise during intensive induction therapy for adults aged ≥18 years among 83 participants (median age, 59 years).6 Recruitment, retention, and adherence rates were 56%, 96%, and 54%, respectively. There were no differences in QOL measures between the groups, but physical fitness, lower body strength, and grip strength improved in the intervention group. Results from a randomized 3-week inpatient walking intervention among 24 patients (mean age, 49 years) receiving AML chemotherapy suggested positive impact on fatigue, warranting further study.33 Limited nonrandomized pilot PA intervention studies specifically enrolling older adults with hematologic malignancies (with only 1 focused on AML)8,14,15 showed mixed feasibility with variable recruitment, participation, and adherence.

Our study demonstrates the feasibility of randomizing older adults with AML to a PA intervention during intensive treatment. Our high rates of recruitment and retention are likely attributable to intervention initiation in the inpatient setting and integration into clinical workflows. Tailoring the intervention with adaptations to include increased frequency, flexibility, and use of behavioral counseling increased participation relative to our initial pilot.8 Importantly, patient satisfaction and perception of benefit were high, with the majority interested in continuing activity after induction. Participant feedback, including recommendations for types of exercises, will be helpful in designing a future efficacy trial.

Our pilot also shows the challenges of testing a behavioral intervention in a high-morbidity setting. For example, ∼20% of potential intervention sessions were medically contraindicated during the course of the study. Although some patients improved and resumed participation, others did not. Between enrollment and 3-month follow-up, ∼20% of patients died or enrolled in hospice care because of complications of treatment or refractory disease. Future studies may consider powering outcomes based on subsets of participants most likely to benefit, such as those expected to achieve remission.

Our outcome of interest was the SPPB because of the utility of this measure in assessing objective change in physical function, its association with survival in AML,11,13,19 and its use as an outcome measure in PA intervention trials in other older adult settings. Our pilot confirms prior observations regarding clinically significant decline in SPPB scores during induction chemotherapy5 with score improvement observed by 6 months among survivors.34 Decline was particularly pronounced among adults aged >75 years. Our pilot study met prespecified criteria supporting the design of a fully powered efficacy trial, with preliminary data suggesting that the intervention could prevent functional decline, particularly among those who achieve remission. This is consistent with studies in younger AML populations demonstrating benefits of PA for objective functional outcomes.35

Similar to other studies, we observed significant declines in self-reported physical function during induction therapy but did not observe a difference between groups in self-reported functional measures, QOL, or symptoms. Although our study was not powered to detect differences in these outcomes, it highlights the importance of including a control group in pilot studies given that both groups demonstrated some resilience in functional measures over time. This might explain the differences between our study results and those of other published single-arm studies.8,15 It is also possible that these outcomes were not as directly affected by the intervention, which targeted strength, balance, and aerobic capacity. Another consideration is that patient-reported function may be influenced by psychosocial and health factors such as acute medical conditions, which are prominent for patients with AML and less likely to be affected by the intervention.36 Furthermore, the accepted threshold for clinically meaningful change in SPPB is based on future risk prediction rather than perceived functional benefit, which could explain the differential impact and warrants consideration in future trial design. Finally, our study population differed in having a higher prevalence of functional limitations at baseline and additional factors during inpatient treatment that may have negatively influenced QOL and symptoms.

Strengths of this study include an exclusive focus on older adults with broad eligibility, including participants with poor performance status and multimorbidity, reflecting patients seen in practice. The intervention was tested early during treatment with a goal of preventing decline rather than reacting to treatment-associated disability, which remains the current clinical standard. The intervention design lends itself to implementation mapping in future trials. Specifically, the intervention could be conducted using the usual care resources, including a physical therapist supported by a physical therapy assistant, with a health coach or nurse navigator facilitating behavioral counseling. Additional strengths include randomization, extensive characterization of the cohort, and detailed outcome assessments. Limitations include the relatively small sample size and single-center experience, which may influence the generalizability of pilot studies. Another potential limitation is the focus on inpatient intervention without outpatient maintenance, which could be incorporated in future studies. Despite the uptake of less intensive therapies such as hypomethylating agents combined with venetoclax for older adults with AML, concerns regarding the maintenance of physical function persist. Our symptom-adapted intervention framework and behavioral counseling could inform new studies designed to maintain function in either the inpatient or outpatient setting, and may be relevant to other intensive settings, including stem cell transplantation, which is increasingly offered to older adults.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the feasibility of conducting a symptom-adapted randomized inpatient PA intervention among older adults treated intensively for AML. The results can be used to support the design of an efficacy trial to prevent decline in physical performance during AML therapy. Future directions include testing symptom-adapted PA interventions for patients treated with less intensive therapies and PA integration into multimodality geriatric assessment–guided supportive care.

Acknowledgments

H.D.K. was funded by the Wake Forest University Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30 AG-021332), Paul B. Beeson Emerging Leaders Career Development Award in Aging Research (K23AG038361; supported by the National Institute on Aging, American Federation for Aging Research, John A. Hartford Foundation, and Atlantic Philanthropies), the Gabrielle’s Angel Foundation for Cancer Research, and the Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Comprehensive Cancer Center’s National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA012197. J.A.T. received funding from the Gabrielle’s Angel Foundation for Cancer Research and the Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Comprehensive Cancer Center’s National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA012197.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the National Cancer Institute or other federal agencies.

Authorship

Contribution: H.D.K. contributed to concept and design, study accrual, manuscript writing, data interpretation, and approval of the final manuscript; J.A.T. contributed to concept and design, data analysis, manuscript writing, data interpretation, and approval of the final manuscript; W.J.R. and S.M. contributed to concept and design, manuscript editing, data interpretation, and approval of the final manuscript; T.S.P. contributed to study accrual, manuscript writing, data interpretation, approval of the final manuscript; L.E. and D.H. contributed to study accrual, manuscript writing, and approval of the final manuscript; W.D.-W. contributed to concept and design, manuscript editing, and approval of the final manuscript; B.L.P. contributed to concept and design, study accrual, manuscript editing, and approval of the final manuscript; and S.K. contributed to concept and design, manuscript editing, data interpretation, and approval of the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Heidi D. Klepin, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Medical Center Blvd, Winston Salem, NC 27157; email: hklepin@wakehealth.edu.

References

Author notes

Deidentified individual participant data that underlie the reported results will be made available 3 months after publication for a period of 3 years after the publication date following institutional protocols. Proposals for access and requests for study protocol should be sent to the corresponding author, Heidi D. Klepin (hklepin@wakehealth.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.