Key Points

Although patients with MM and WM generate SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, their antibody-mediated effector functions are significantly imparied.

Administration of at least two SARS-CoV-2 booster doses can overcome ineffective vaccine responses in nearly 90% of patients with MM and WM.

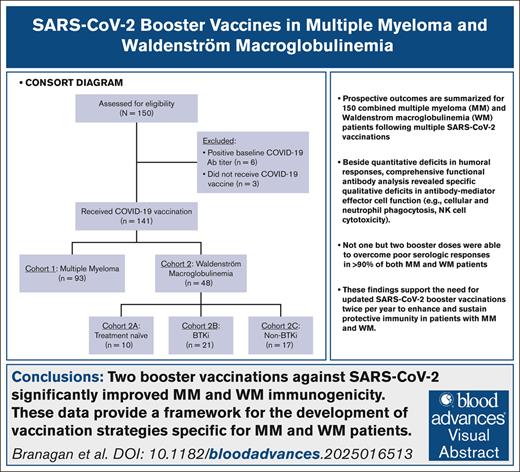

Visual Abstract

Patients with multiple myeloma (MM) and Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM) have increased risk of severe coronavirus disease 2019. Impaired humoral responses to the primary vaccination series against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) have been reported in patients with MM and WM, but the impact of booster vaccinations and functional status of the elicited antibodies are unknown. We performed a prospective cohort study investigating SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with MM (n = 93) and WM (n = 48). The primary end point was effective immune response (EIR) at 28 days after the primary vaccination series (ie, anti–spike SARS-CoV-2 antibody titer >250 U/mL). The EIR rate after the primary vaccination series was 47% and 25% in patients with MM and WM, respectively. After the first and second booster vaccinations, the EIR rates increased to 84% and 91% in patients with MM and 60% and 89% in those with WM, respectively. Factors associated with lower EIR in patients with MM were hypogammaglobulinemia, lymphopenia, and treatment with anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody or corticosteroid. In patients with WM, treatment with a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor or rituximab was associated with a lower EIR, whereas asymptomatic and treatment-naïve patients had a higher EIR. Functional profiling identified reduced antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis, neutrophil phagocytosis, and natural killer cell activity against wild-type and variant SARS-CoV-2 (Alpha, Beta, and Gamma) in patients with MM and WM compared to healthy donors. Our data demonstrate that although patients with MM and WM have impaired humoral responses to the primary SARS-CoV-2 vaccination series, repeated booster vaccines significantly improve immunogenicity. This trial was registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov as #NCT04830046.

Introduction

Plasma cell dyscrasias (PCD), such as multiple myeloma (MM) and Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM), are hematologic malignancies characterized by the proliferation of neoplastic plasma cells in the bone marrow that secrete a monoclonal immunoglobulin. The rate of infections is higher in patients with a PCD than in the general population,1,2 and infection is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality.3,4 The increased susceptibility to infection is due to immunosuppression caused by the disease itself, as well as treatment regimens and host-related factors (eg, age, comorbidities, and frailty).5

Impaired humoral immunity due to B-cell dysfunction frequently occurs with PCD and manifests as hypogammaglobulinemia (ie, suppression of uninvolved polyclonal immunoglobulins).5,6 Defects in cellular and innate immunity have also been described, including T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, dendritic cells, the alternative complement pathway, and neutropenia.5,7-12 This immune dysfunction is often exacerbated by treatments used for PCD. Specifically, therapies that deplete the B-cell and plasma cell compartments by targeting B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA), CD38, CD20, and Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) may worsen hypogammaglobulinemia.5,13-15 T-cell immunodeficiency can be caused by proteasome inhibitors, anti-CD38 monoclonal antibodies, and the lymphodepleting chemotherapy administered for chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy.5,16-19 Corticosteroids and autologous stem cell transplantation are also highly immunosuppressive.20

The mechanisms underlying immunosuppression in PCD also result in impaired immune responses to vaccinations. Although there are limited data on patients with WM,21 suboptimal antibody production has been reported in patients with MM after vaccination against Streptococcus pneumoniae and seasonal influenza22,23; for example, 1 study showed that the standard influenza vaccination resulted in seroprotection in only <20% of patients with MM.22 However, using either a 2- or 3-dose series of a high-dose influenza vaccination significantly improves immunogenicity in patients with MM,24,25 highlighting the need to develop vaccination strategies for this specific patient population.

Patients with a PCD have an increased risk of severe complications with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory distress syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).26 Impaired antibody-mediated responses to the primary vaccination series for SARS-CoV-2 have been reported in both patients with MM and WM,27-34 but there are limited data on the impact of booster vaccinations on immunogenicity.

We performed a prospective cohort study to compare vaccine responses against SARS-CoV-2 in patients with MM and WM. We assessed responses to both the primary and booster vaccinations and identified clinical factors predictive of vaccine response.

Methods

Patients and study design

This prospective cohort study was approved by the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Institutional Review Board and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice Guidelines. Patients were enrolled at the Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. All patients provided written consent. The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier: NCT04830046).

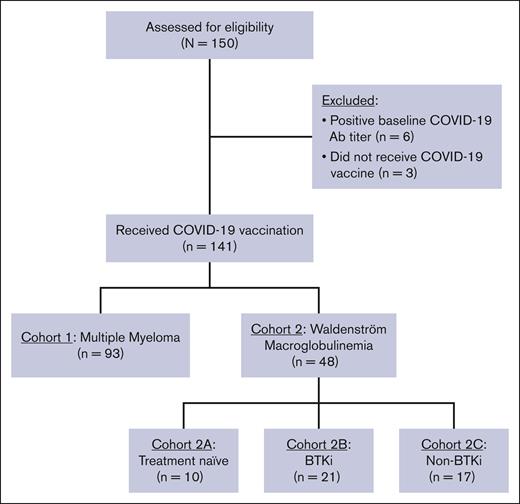

Inclusion criteria were age ≥18 years and a diagnosis of MM or WM per the International Myeloma Working Group and World Health Organization criteria, respectively. Eligible patients had intended to receive a SARS-CoV-2 vaccination within 60 days, and none had received a prior SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. We excluded patients with a previous COVID-19 infection by clinical history and/or serological testing (ie, positive baseline SARS-CoV-2 antibody titer). The 2-cohort trial design is shown in Figure 1. Patients with MM were assigned to cohort 1, and patients with WM were assigned to cohort 2. Patients with WM in cohort 2 were assigned into 3 subgroups based on treatment history: cohort 2A (treatment naïve), cohort 2B (active treatment with BTK inhibitor [BTKi]), and cohort 2C (previously or currently treated, excluding BTKi).

The primary study end point was the effective immune response (EIR) rate at 28 days after the second or final dose of the primary vaccination series against SARS-CoV-2. EIR was defined as a positive anti–spike SARS-CoV-2 antibody titer >250 U/mL.29 Key secondary end points were to investigate the following: (1) durability of an EIR after vaccination; (2) clinical correlates of attaining an EIR; (3) rates of COVID-19 infection after vaccination; and (4) functional biomarkers of immune response.

Study assessments

Patient and disease characteristics, treatment history, complete blood counts, and immunoglobulin levels were obtained at baseline. SARS-CoV-2 serologies were assessed at baseline and at 28 days and 12 months after the primary vaccination series. Serologies were also obtained after booster vaccinations in a subset of patients. SARS-CoV-2 serologies were measured with a quantitative electrochemiluminescence immunoassay that detects antibodies to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein receptor–binding domain (Roche Diagnostics). SARS-CoV-2 antibody titer ≥0.80 U/mL was considered positive.

Vaccine administration

SARS-CoV-2 vaccines were obtained through commercial supply and were administered per the package insert. Specific vaccine product selection was based on the availability of BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech), messenger RNA 1273 (mRNA-1273; Moderna), or JNJ-78436735 (Johnson & Johnson). The primary vaccination series for BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 included 2 doses of the original monovalent vaccine, whereas JNJ-78436735 included 1 dose of the monovalent vaccine.

Functional antibody profiling

Functional profiling occurred in 3 cohorts: patients with MM (n = 23), patients with WM (n = 14), and noncancer (NC) healthy donors (n = 14). Plasma was collected in all patients after receiving 2 doses of an mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (ie, primary vaccination series). As previously described, spike antibody subclasses and isotypes against SARS-CoV-2 wild type (WT) and variants of concern were quantified.35 Antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP), antibody-dependent neutrophil phagocytosis (ADNP), antibody-dependent complement depositions, and antibody-dependent NK-cell activity were also assessed as previously described.35

Statistical analyses

Baseline clinical characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics with median/range for continuous variables and numbers/percentages for categorical variables. Nonparametric comparisons of continuous variables were made using the Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis test. Comparisons of categorical variables were made using the Fisher exact test or χ2 test. Logistic regression models were fitted to identify predictors of attaining an EIR after SAR-CoV-2 vaccination; results are presented as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. P values < .05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed in the R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Patient characteristics

Between June 2019 and August 2021, a total of 150 patients were enrolled, of whom 9 were excluded from the final analysis due to baseline serological evidence of prior COVID-19 infection (n = 6) or not receiving vaccination (n = 3; Figure 1). The final cohort included 141 patients: 93 patients with MM (cohort 1) and 48 patients with WM (cohort 2). Among patients with WM, there were 10, 21, and 17 patients in cohorts 2A, 2B, and 2C, respectively. The baseline clinical characteristics of patients with MM and WM are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. All patients included in the final cohort received a primary SARS-CoV-2 vaccination series: BNT162b2 (n = 77 [55%]), mRNA-1273 (n = 51 [36%]), and JNJ-78436735 (n = 13 [9%]).

Baseline clinical characteristics of patients with MM before the initial SARS-CoV-2 vaccination (cohort 1)

| Patient characteristic . | All patients (n = 93) . |

|---|---|

| Age, y | |

| Median (range) | 65 (44-84) |

| >75, n (%) | 7 (8) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 48 (52) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 83 (89) |

| Non-White | 10 (11) |

| COVID-19 vaccine, n (%) | |

| BNT162b2 | 49 (53) |

| mRNA-1273 | 34 (37) |

| JNJ-78436735 | 10 (11) |

| R-ISS stage, n (%) | |

| I | 46/85 (54) |

| II | 24/85 (28) |

| III | 15/85 (18) |

| Involved heavy and/or light chain, n (%) | |

| IgG | 51 (55) |

| IgA | 16 (17) |

| κ | 61 (66) |

| λ | 24 (26) |

| Nonsecretory | 1 (1) |

| Median monoclonal protein (range), g/dL | 0.05 (0-3.68) |

| Treatment status, n (%) | |

| Treatment naïve | 8 (9) |

| Previously treated | 85 (91) |

| Median no. of previous treatment lines (range) | 1 (1-7) |

| Current treatment regimens,∗n (%) | |

| Immunomodulatory agent | 46 (53) |

| Corticosteroid | 40 (46) |

| Proteasome inhibitor | 35 (40) |

| Anti-CD38 monoclonal Ab | 32 (37) |

| BCMA CAR-T | 12 (14) |

| Alkylating agent | 4 (5) |

| Belantamab mafodotin | 1 (1) |

| Elotuzumab | 1 (1) |

| Hypogammaglobulinemia (IgG <400 mg/dL), n (%) | 17 (18) |

| IV immunoglobulin within 90 days, n (%) | 13 (14) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |

| Pulmonary disease | 10 (11) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 2 (2) |

| Diabetes | 12 (13) |

| Hypertension | 53 (57) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 6 (6) |

| Obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2) | 39 (42) |

| Current tobacco use | 0 (0) |

| Patient characteristic . | All patients (n = 93) . |

|---|---|

| Age, y | |

| Median (range) | 65 (44-84) |

| >75, n (%) | 7 (8) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 48 (52) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 83 (89) |

| Non-White | 10 (11) |

| COVID-19 vaccine, n (%) | |

| BNT162b2 | 49 (53) |

| mRNA-1273 | 34 (37) |

| JNJ-78436735 | 10 (11) |

| R-ISS stage, n (%) | |

| I | 46/85 (54) |

| II | 24/85 (28) |

| III | 15/85 (18) |

| Involved heavy and/or light chain, n (%) | |

| IgG | 51 (55) |

| IgA | 16 (17) |

| κ | 61 (66) |

| λ | 24 (26) |

| Nonsecretory | 1 (1) |

| Median monoclonal protein (range), g/dL | 0.05 (0-3.68) |

| Treatment status, n (%) | |

| Treatment naïve | 8 (9) |

| Previously treated | 85 (91) |

| Median no. of previous treatment lines (range) | 1 (1-7) |

| Current treatment regimens,∗n (%) | |

| Immunomodulatory agent | 46 (53) |

| Corticosteroid | 40 (46) |

| Proteasome inhibitor | 35 (40) |

| Anti-CD38 monoclonal Ab | 32 (37) |

| BCMA CAR-T | 12 (14) |

| Alkylating agent | 4 (5) |

| Belantamab mafodotin | 1 (1) |

| Elotuzumab | 1 (1) |

| Hypogammaglobulinemia (IgG <400 mg/dL), n (%) | 17 (18) |

| IV immunoglobulin within 90 days, n (%) | 13 (14) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |

| Pulmonary disease | 10 (11) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 2 (2) |

| Diabetes | 12 (13) |

| Hypertension | 53 (57) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 6 (6) |

| Obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2) | 39 (42) |

| Current tobacco use | 0 (0) |

Ab, antibody; BMI, body mass index; CAR-T, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy; R-ISS, Revised Multiple Myeloma International Staging System.

Among patients who were receiving active treatment at the time of vaccination (n = 87).

Baseline clinical characteristics of patients with WM before the initial SARS-CoV-2 vaccination (cohort 2)

| Patient characteristic . | All patients (n = 48) . |

|---|---|

| Age, y | |

| Median (range) | 67 (49-81) |

| >75, n (%) | 5 (10) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 28 (58) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 46 (96) |

| Non-White | 2 (4) |

| COVID-19 vaccine, n (%) | |

| BNT162b2 | 28 (58) |

| mRNA-1273 | 17 (35) |

| JNJ-78436735 | 3 (6) |

| MYD88 mutation, n (%) | |

| Mutated | 35 (73) |

| WT | 8 (17) |

| Unknown | 5 (10) |

| CXCR4 mutation, n (%) | |

| Mutated | 11 (23) |

| WT | 12 (25) |

| Unknown | 25 (52) |

| Asymptomatic WM, n (%) | 8 (17) |

| Treatment status, n (%) | |

| Treatment naïve | 12 (25) |

| Previously treated | 36 (75) |

| Median no. of previous treatment lines (range) | 1 (1-4) |

| Current treatment regimens,∗n (%) | |

| BTKi | 21 (58) |

| Rituximab | 8 (17) |

| Venetoclax | 4 (8) |

| Bendamustine | 2 (4) |

| Proteasome inhibitor | 2 (4) |

| Corticosteroid | 2 (4) |

| Fludarabine | 1 (2) |

| Median serum immunoglobulin level (IQR), mg/dL | |

| IgM | 837 (39-5835) |

| IgG | 598 (121-1825) |

| IgA | 42 (5-285) |

| Hypogammaglobulinemia (IgG <400 mg/dL), n (%) | 34 (71) |

| IV immunoglobulin within 90 days, n (%) | 5 (10) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |

| Pulmonary disease | 7 (15) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 6 (13) |

| Diabetes | 1 (2) |

| Hypertension | 15 (31) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 7 (15) |

| Obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2) | 5 (10) |

| Current tobacco use | 6 (13) |

| Patient characteristic . | All patients (n = 48) . |

|---|---|

| Age, y | |

| Median (range) | 67 (49-81) |

| >75, n (%) | 5 (10) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 28 (58) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 46 (96) |

| Non-White | 2 (4) |

| COVID-19 vaccine, n (%) | |

| BNT162b2 | 28 (58) |

| mRNA-1273 | 17 (35) |

| JNJ-78436735 | 3 (6) |

| MYD88 mutation, n (%) | |

| Mutated | 35 (73) |

| WT | 8 (17) |

| Unknown | 5 (10) |

| CXCR4 mutation, n (%) | |

| Mutated | 11 (23) |

| WT | 12 (25) |

| Unknown | 25 (52) |

| Asymptomatic WM, n (%) | 8 (17) |

| Treatment status, n (%) | |

| Treatment naïve | 12 (25) |

| Previously treated | 36 (75) |

| Median no. of previous treatment lines (range) | 1 (1-4) |

| Current treatment regimens,∗n (%) | |

| BTKi | 21 (58) |

| Rituximab | 8 (17) |

| Venetoclax | 4 (8) |

| Bendamustine | 2 (4) |

| Proteasome inhibitor | 2 (4) |

| Corticosteroid | 2 (4) |

| Fludarabine | 1 (2) |

| Median serum immunoglobulin level (IQR), mg/dL | |

| IgM | 837 (39-5835) |

| IgG | 598 (121-1825) |

| IgA | 42 (5-285) |

| Hypogammaglobulinemia (IgG <400 mg/dL), n (%) | 34 (71) |

| IV immunoglobulin within 90 days, n (%) | 5 (10) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |

| Pulmonary disease | 7 (15) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 6 (13) |

| Diabetes | 1 (2) |

| Hypertension | 15 (31) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 7 (15) |

| Obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2) | 5 (10) |

| Current tobacco use | 6 (13) |

IQR, interquartile range.

Among patients who were receiving active treatment at the time of vaccination (n = 36).

Humoral response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination

Overall, the EIR rate at 28 days after the primary SARS-CoV-2 vaccination series (ie, antispike antibody >250 U/mL) was 47% in patients with MM and 25% in patients with WM (Table 3). A positive titer (ie, antispike antibody ≥0.8 U/mL) was observed in 94% of patients with MM and 65% of patients with WM, and the median antispike antibody titer was 188.0 U/mL (range, 0-4161) and 2.2 U/mL (range, 0-2500), respectively. Among patients with WM, the EIR rates in treatment naïve (cohort 2A), active BTKi therapy (cohort 2B), and previously/currently treated subgroups (cohort 2C) were 60%, 10%, and 24%, respectively.

Humoral responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in MM and WM

| Vaccine responses . | Cohort 1, MM (n = 93) . | Cohort 2, WM . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients (n = 48) . | 2A (n = 10) . | 2B (n = 21) . | 2C (n = 17) . | ||

| 28 days after primary vaccination series | |||||

| EIR, n (%) | 44/93 (47) | 12/48 (25) | 6/10 (60) | 2/21 (10) | 4/17 (24) |

| Positive Ab titer, n (%) | 87/93 (94) | 31/48 (65) | 9/10 (90) | 12/21 (57) | 10/17 (59) |

| Median Ab titer (range), U/mL | 188.0 (0-4 161) | 2.2 (0-2 500) | 282.3 (0-2 500) | 0.8 (0-2 500) | 0.6 (0-2 500) |

| After first booster | |||||

| EIR, n (%) | 66/79 (84) | 25/42 (60) | 7/10 (70) | 12/19 (63) | 6/13 (46) |

| Positive Ab titer, n (%) | 79/79 (100) | 31/42 (74) | 9/10 (90) | 14/19 (74) | 8/13 (62) |

| Median Ab titer (range), U/mL | 5 130 (3.2-25 000) | 998.5 (0-25 000) | 2 500 (0-25 000) | 1 215 (0-12 500) | 9.1 (0-2 500) |

| After second booster | |||||

| EIR, n (%) | 30/33 (91) | 16/18 (89) | 4/4 (100) | 6/7 (86) | 6/7 (86) |

| Positive Ab titer, n (%) | 33/33 (100) | 17/18 (94) | 5/5 (100) | 6/7 (86) | 7/7 (100) |

| Median Ab titer (range), U/mL | 8 169 (52.2-25 000) | 3 379 (0-12 500) | 5 829 (2 996-12 500) | 2 506 (0-7 996) | 5 731 (58.3-12 500) |

| 12 months after primary vaccination series ± booster(s) | |||||

| EIR, n (%) | 68/80 (85) | 33/40 (83) | 8/10 (80) | 14/17 (82) | 11/13 (85) |

| Positive Ab titer, n (%) | 80/80 (100) | 40/40 (100) | 10/10 (100) | 17/17 (100) | 13/13 (100) |

| Median Ab titer (range), U/mL | 3 955 (3.6-25 000) | 2 063 (0.4-25 000) | 3 086 (11.2-25 000) | 1 843 (0.4-10 908) | 3 414 (0.8-12 500) |

| Vaccine responses . | Cohort 1, MM (n = 93) . | Cohort 2, WM . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients (n = 48) . | 2A (n = 10) . | 2B (n = 21) . | 2C (n = 17) . | ||

| 28 days after primary vaccination series | |||||

| EIR, n (%) | 44/93 (47) | 12/48 (25) | 6/10 (60) | 2/21 (10) | 4/17 (24) |

| Positive Ab titer, n (%) | 87/93 (94) | 31/48 (65) | 9/10 (90) | 12/21 (57) | 10/17 (59) |

| Median Ab titer (range), U/mL | 188.0 (0-4 161) | 2.2 (0-2 500) | 282.3 (0-2 500) | 0.8 (0-2 500) | 0.6 (0-2 500) |

| After first booster | |||||

| EIR, n (%) | 66/79 (84) | 25/42 (60) | 7/10 (70) | 12/19 (63) | 6/13 (46) |

| Positive Ab titer, n (%) | 79/79 (100) | 31/42 (74) | 9/10 (90) | 14/19 (74) | 8/13 (62) |

| Median Ab titer (range), U/mL | 5 130 (3.2-25 000) | 998.5 (0-25 000) | 2 500 (0-25 000) | 1 215 (0-12 500) | 9.1 (0-2 500) |

| After second booster | |||||

| EIR, n (%) | 30/33 (91) | 16/18 (89) | 4/4 (100) | 6/7 (86) | 6/7 (86) |

| Positive Ab titer, n (%) | 33/33 (100) | 17/18 (94) | 5/5 (100) | 6/7 (86) | 7/7 (100) |

| Median Ab titer (range), U/mL | 8 169 (52.2-25 000) | 3 379 (0-12 500) | 5 829 (2 996-12 500) | 2 506 (0-7 996) | 5 731 (58.3-12 500) |

| 12 months after primary vaccination series ± booster(s) | |||||

| EIR, n (%) | 68/80 (85) | 33/40 (83) | 8/10 (80) | 14/17 (82) | 11/13 (85) |

| Positive Ab titer, n (%) | 80/80 (100) | 40/40 (100) | 10/10 (100) | 17/17 (100) | 13/13 (100) |

| Median Ab titer (range), U/mL | 3 955 (3.6-25 000) | 2 063 (0.4-25 000) | 3 086 (11.2-25 000) | 1 843 (0.4-10 908) | 3 414 (0.8-12 500) |

At least 1 booster vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 was administered in 79 patients with MM (1 booster, n = 27; 2 boosters, n = 52) and 45 patients with WM (1 booster, n = 20; 2 boosters, n = 25). The median time from completing the primary vaccination series to receiving the first and second boosters was 5.1 and 11.3 months, respectively, in patients with MM and 4.3 and 10.0 months, respectively, in patients with WM. The EIR rates after the first and second booster vaccinations were 84% and 91% in patients with MM, respectively, and 60% and 89% in patients with WM, respectively. At 12 months after the primary SARS-CoV-2 vaccination series (including the subsequent booster vaccinations), the EIR rate was 85% and 83% in patients with MM and WM, respectively. All tested patients had a positive antispike antibody titer at 12 months.

Predictors of humoral response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination

We performed a preplanned univariate analysis to identify baseline clinical factors associated with a humoral response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination (ie, EIR at 28 days after the primary vaccination series; Table 4). In patients with MM, the EIR rate was significantly lower with hypogammaglobulinemia (6% vs 57%; P < .001), lymphopenia (32% vs 68%; P < .001), and active treatment with an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody (31% vs 56%; P = .03) or corticosteroid (30% vs 60%; P = .006). Current (<2 months) anti-CD38 monoclonal use was also associated with a significantly lower EIR rate (31% vs 63%; P = .004). Patients with MM with an immunoglobulin G (IgG) isotype had a significantly higher EIR rate (59% vs 33%; P = .02). In patients with WM, the EIR rate was significantly lower if on active treatment with a BTKi (10% vs 50%; P = .01) or rituximab (0% vs 50%; P = .04), whereas asymptomatic (63% vs 18%; P = .01) and treatment-naïve patients (50% vs 17%; P = .04) had a significantly higher EIR rate. A primary vaccination series with mRNA-1273 was associated with a significantly higher EIR rate than BNT162b2 in both patients MM (65% vs 39%; P = .03) and WM (53% vs 11%; P = .004).

Predictors of an EIR at 28 days after primary SARS-CoV-2 vaccination series in MM and WM

| . | OR (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|

| MM | ||

| Age >75 years | 0.17 (0.01-1.49) | .11 |

| Male sex | 1.34 (0.55-3.29) | .54 |

| Non-White race | 1.77 (0.39-9.16) | .51 |

| mRNA-1273 (vs BNT162b2) | 2.86(1.07-7.97) | .03 |

| R-ISS stage III (vs I/II) | 0.53 (0.13-1.93) | .39 |

| IgG isotype (vs non-IgG) | 2.82 (1.13-7.32) | .02 |

| Treatment naïve | 1.12 (0.20-6.45) | 1.00 |

| Current treatment | ||

| IMiD | 1.74 (0.71-4.33) | .22 |

| PI | 0.43 (0.16-1.10) | .06 |

| Anti-CD38 mAb | 0.37 (0.13-0.97) | .03 |

| BCMA CAR-T | 1.11 (0.01-89.4) | 1.00 |

| Corticosteroid | 0.29 (0.11-0.73) | .006 |

| Previous ASCT | 1.59 (0.60-4.27) | .37 |

| CR (vs less than CR) | 1.27 (0.42-3.89) | .80 |

| >1 previous treatment line (vs 0-1) | 0.35 (0.10-1.05) | .07 |

| Hypogammaglobulinemia | 0.04 (0.01-0.25) | .004 |

| IV immunoglobulin within 90 days | 0.29 (0.05-1.24) | .08 |

| ALC ×103/μL | 0.23 (0.09-0.54) | <.001 |

| Pulmonary disease | 1.13 (0.24-5.30) | 1.00 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1.11 (0.01-89.4) | 1.00 |

| Diabetes | 1.66 (0.41-7.20) | .54 |

| Hypertension | 0.58 (0.23-1.44) | .22 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 1.12 (0.14-8.84) | 1.00 |

| Obesity | 1.87 (0.75-4.71) | .15 |

| Current tobacco use | UTC | UTC |

| WM | ||

| Age >65 years | 2.93 (0.60-19.6) | .18 |

| Male sex | 0.38 (0.06-1.86) | .31 |

| Non-White race | UTC | UTC |

| mRNA-1273 (vs BNT162b2) | 8.82 (1.69-63.4) | .004 |

| MYD88 mutation | 0.63 (0.08-7.83) | .63 |

| CXCR4 mutation | 0.32 (0.01-4.77) | .59 |

| Asymptomatic WM | 7.86 (1.58-46.5) | .01 |

| Treatment naïve | 4.80 (1.03-26.2) | .04 |

| Current BTKi use | 0.11 (0.01-0.85) | .01 |

| Current rituximab use | UTC | .04 |

| Progressive disease | 2.90 (0.34-19.8) | .28 |

| >1 previous treatment line (vs 0-1) | 3.29 (0.51-21.7) | .20 |

| Hypogammaglobulinemia | 1.36 (0.27-9.37) | 1.00 |

| IV immunoglobulin within 90 days | 2.24 (0.16-23.0) | .58 |

| ALC ×103/μL | 0.87 (0.46-1.13) | .48 |

| Pulmonary disease | 1.23 (0.10-9.13) | 1.00 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 0.57 (0.01-5.97) | 1.00 |

| Diabetes | UTC | UTC |

| Hypertension | 0.67 (0.10-3.40) | .73 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 1.23 (0.10-9.13) | 1.00 |

| Obesity | 0.73 (0.01-8.52) | 1.00 |

| Current tobacco use | 0.57 (0.01-5.97) | 1.00 |

| . | OR (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|

| MM | ||

| Age >75 years | 0.17 (0.01-1.49) | .11 |

| Male sex | 1.34 (0.55-3.29) | .54 |

| Non-White race | 1.77 (0.39-9.16) | .51 |

| mRNA-1273 (vs BNT162b2) | 2.86(1.07-7.97) | .03 |

| R-ISS stage III (vs I/II) | 0.53 (0.13-1.93) | .39 |

| IgG isotype (vs non-IgG) | 2.82 (1.13-7.32) | .02 |

| Treatment naïve | 1.12 (0.20-6.45) | 1.00 |

| Current treatment | ||

| IMiD | 1.74 (0.71-4.33) | .22 |

| PI | 0.43 (0.16-1.10) | .06 |

| Anti-CD38 mAb | 0.37 (0.13-0.97) | .03 |

| BCMA CAR-T | 1.11 (0.01-89.4) | 1.00 |

| Corticosteroid | 0.29 (0.11-0.73) | .006 |

| Previous ASCT | 1.59 (0.60-4.27) | .37 |

| CR (vs less than CR) | 1.27 (0.42-3.89) | .80 |

| >1 previous treatment line (vs 0-1) | 0.35 (0.10-1.05) | .07 |

| Hypogammaglobulinemia | 0.04 (0.01-0.25) | .004 |

| IV immunoglobulin within 90 days | 0.29 (0.05-1.24) | .08 |

| ALC ×103/μL | 0.23 (0.09-0.54) | <.001 |

| Pulmonary disease | 1.13 (0.24-5.30) | 1.00 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1.11 (0.01-89.4) | 1.00 |

| Diabetes | 1.66 (0.41-7.20) | .54 |

| Hypertension | 0.58 (0.23-1.44) | .22 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 1.12 (0.14-8.84) | 1.00 |

| Obesity | 1.87 (0.75-4.71) | .15 |

| Current tobacco use | UTC | UTC |

| WM | ||

| Age >65 years | 2.93 (0.60-19.6) | .18 |

| Male sex | 0.38 (0.06-1.86) | .31 |

| Non-White race | UTC | UTC |

| mRNA-1273 (vs BNT162b2) | 8.82 (1.69-63.4) | .004 |

| MYD88 mutation | 0.63 (0.08-7.83) | .63 |

| CXCR4 mutation | 0.32 (0.01-4.77) | .59 |

| Asymptomatic WM | 7.86 (1.58-46.5) | .01 |

| Treatment naïve | 4.80 (1.03-26.2) | .04 |

| Current BTKi use | 0.11 (0.01-0.85) | .01 |

| Current rituximab use | UTC | .04 |

| Progressive disease | 2.90 (0.34-19.8) | .28 |

| >1 previous treatment line (vs 0-1) | 3.29 (0.51-21.7) | .20 |

| Hypogammaglobulinemia | 1.36 (0.27-9.37) | 1.00 |

| IV immunoglobulin within 90 days | 2.24 (0.16-23.0) | .58 |

| ALC ×103/μL | 0.87 (0.46-1.13) | .48 |

| Pulmonary disease | 1.23 (0.10-9.13) | 1.00 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 0.57 (0.01-5.97) | 1.00 |

| Diabetes | UTC | UTC |

| Hypertension | 0.67 (0.10-3.40) | .73 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 1.23 (0.10-9.13) | 1.00 |

| Obesity | 0.73 (0.01-8.52) | 1.00 |

| Current tobacco use | 0.57 (0.01-5.97) | 1.00 |

Values corresponding to P < 0.05 are set in bold.

ALC, absolute lymphocyte count; ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; CI, confidence interval; CR, complete response; IMiD, immunomodulatory agent; mAb, monoclonal antibody; OR, odds ratio; PI, proteasome inhibitor; UTC, unable to calculate.

Functional characterization of humoral response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination

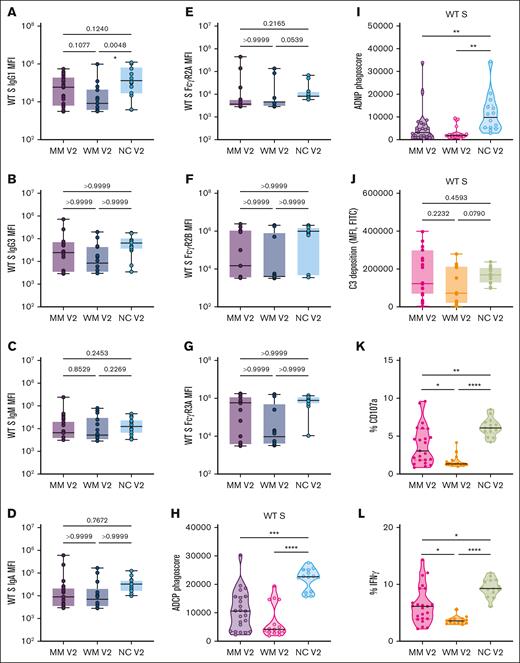

We performed a functional characterization of the WT SARS-CoV-2 spike antibodies that were generated after a primary mRNA-based vaccination series in patients with MM (n = 23), patients with WM (n = 14), and NC healthy donors (n = 14). WT SARS-CoV-2 spike antibodies (ie, IgG1, IgG3, IgM, and IgA) were detected in all tested patients. Patients with MM and WM had similar WT spike antibody titers compared to NC healthy donors, with the exception of a lower IgG1 in patients with WM (Figure 2A-D). FcγR2A, FcγR2B, and FcγR3A titers for WT SARS-CoV-2 were also similar (Figure 2E-G). Spike-specific ADCP, ADNP, and antibody-dependent NK-cell activity responses to WT SARS-CoV-2 were significantly lower in patients with MM and WM, whereas antibody-dependent complement deposition responses were preserved (Figure 2H-L).

Functional profiling of SARS-CoV-2 WT spike antibody responses. (A-G) Box plots of IgG1, IgG3, IgM, IgA, FcR2A, FcR2B, FcR3A, or FcR3B titers in log10 MFI. Lines represent the minimum, lower quartile, median, upper quartile, and maximum. Statistical significance between groups was tested with a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis multiple comparisons test. P values are as indicated. (H) Truncated violin plot of phagoscores from ADCP assay. The dashed lines represent quartiles, with a solid black line for median. Statistical significance between groups was tested with a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis multiple comparisons test. P values are indicated as follows: not significant (ns), P = .1234; ∗P = .0332; ∗∗P = .0021; ∗∗∗P = .0002; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (I) Truncated violin plot of phagoscores from the ADNP assay. The dashed lines represent quartiles, with a solid black line denoting the median. Statistical significance between groups was tested with a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis multiple comparisons test. P values are indicated as follows: ns, P = .1234; ∗P = .0332; ∗∗P = .0021; ∗∗∗P = .0002; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (J) Box plot of antibody-dependent complement deposition, shown as the MFI of FITC+ beads. Lines represent the minimum, lower quartile, median, upper quartile, and maximum. Statistical significance between groups was tested with a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis multiple comparisons test. P values are as indicated. (K-L) Truncated violin plots of antibody-dependent NK-cell activation: percentage of CD107a+ NK cells or percentage of IFN-γ+ NK cells. Dashed lines represent quartiles, with a solid black line denoting the median. Statistical significance between groups was tested with a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis multiple comparisons test. P values are indicated as follows: ns, P = .1234; ∗P = .0332; ∗∗P = .0021; ∗∗∗P = .0002; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; IFN-γ, interferon gamma; MFI, median fluorescence intensity.

Functional profiling of SARS-CoV-2 WT spike antibody responses. (A-G) Box plots of IgG1, IgG3, IgM, IgA, FcR2A, FcR2B, FcR3A, or FcR3B titers in log10 MFI. Lines represent the minimum, lower quartile, median, upper quartile, and maximum. Statistical significance between groups was tested with a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis multiple comparisons test. P values are as indicated. (H) Truncated violin plot of phagoscores from ADCP assay. The dashed lines represent quartiles, with a solid black line for median. Statistical significance between groups was tested with a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis multiple comparisons test. P values are indicated as follows: not significant (ns), P = .1234; ∗P = .0332; ∗∗P = .0021; ∗∗∗P = .0002; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (I) Truncated violin plot of phagoscores from the ADNP assay. The dashed lines represent quartiles, with a solid black line denoting the median. Statistical significance between groups was tested with a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis multiple comparisons test. P values are indicated as follows: ns, P = .1234; ∗P = .0332; ∗∗P = .0021; ∗∗∗P = .0002; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (J) Box plot of antibody-dependent complement deposition, shown as the MFI of FITC+ beads. Lines represent the minimum, lower quartile, median, upper quartile, and maximum. Statistical significance between groups was tested with a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis multiple comparisons test. P values are as indicated. (K-L) Truncated violin plots of antibody-dependent NK-cell activation: percentage of CD107a+ NK cells or percentage of IFN-γ+ NK cells. Dashed lines represent quartiles, with a solid black line denoting the median. Statistical significance between groups was tested with a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis multiple comparisons test. P values are indicated as follows: ns, P = .1234; ∗P = .0332; ∗∗P = .0021; ∗∗∗P = .0002; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; IFN-γ, interferon gamma; MFI, median fluorescence intensity.

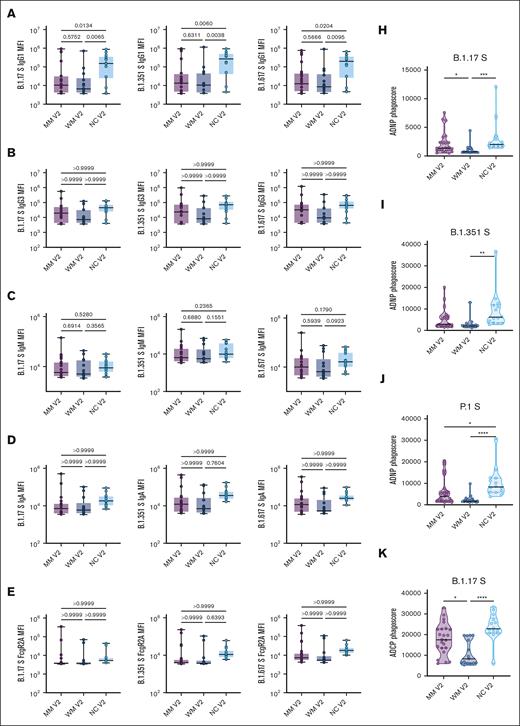

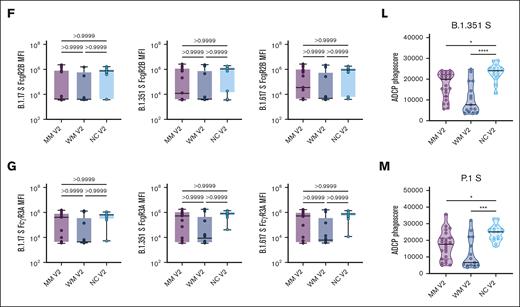

Spike antibodies for SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern were also evaluated, including the Alpha (B.1.1.7), Beta (B.1.351), and Gamma (P.1) variants (Figure 3). For all 3 variants, the IgG1 titer and ADNP and ADCP responses were significantly lower in patients with MM and WM than NC healthy donors.

Functional profiling of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern spike antibody responses. (A-G) Box plots of B.1.17 S–, B.1.351 S–, and B.1.617 S–specific IgG1, IgG3, IgM, IgA, FcR2A, FcR2B, FcR3A, or FcR3B titers in log10 MFI. Lines represent the minimum, lower quartile, median, upper quartile, and maximum. Statistical significance between groups was tested with a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis multiple comparisons test. P values are as indicated. (H-J) Truncated violin plots of B.1.17 S–, B.1.351 S–, and P.1 S–directed ADNP. The dashed lines represent quartiles, with a solid black line denoting the median. Statistical significance between groups was tested with a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis multiple comparisons test. P values are indicated as follows: ns, P = .1234; ∗P = .0332; ∗∗P = .0021; ∗∗∗P = .0002; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (K-M) Truncated violin plots of B.1.17 S–, B.1.351 S–, and P.1 S–directed ADCP. The dashed lines represent quartiles, with a solid black line denoting the median. Statistical significance between groups was tested with a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis multiple comparisons test. P values are indicated as follows: ns, P = .1234; ∗P = .0332; ∗∗P = .0021; ∗∗∗P = .0002; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

Functional profiling of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern spike antibody responses. (A-G) Box plots of B.1.17 S–, B.1.351 S–, and B.1.617 S–specific IgG1, IgG3, IgM, IgA, FcR2A, FcR2B, FcR3A, or FcR3B titers in log10 MFI. Lines represent the minimum, lower quartile, median, upper quartile, and maximum. Statistical significance between groups was tested with a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis multiple comparisons test. P values are as indicated. (H-J) Truncated violin plots of B.1.17 S–, B.1.351 S–, and P.1 S–directed ADNP. The dashed lines represent quartiles, with a solid black line denoting the median. Statistical significance between groups was tested with a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis multiple comparisons test. P values are indicated as follows: ns, P = .1234; ∗P = .0332; ∗∗P = .0021; ∗∗∗P = .0002; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (K-M) Truncated violin plots of B.1.17 S–, B.1.351 S–, and P.1 S–directed ADCP. The dashed lines represent quartiles, with a solid black line denoting the median. Statistical significance between groups was tested with a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis multiple comparisons test. P values are indicated as follows: ns, P = .1234; ∗P = .0332; ∗∗P = .0021; ∗∗∗P = .0002; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

Breakthrough COVID-19 infections

Nineteen patients (13%) developed a COVID-19 infection within 12 months after the initial SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. The incidence of a breakthrough COVID-19 infection in patients with MM and WM was 17% (n = 16/93) and 6% (n = 3/48), respectively. Among those with a breakthrough infection, 9 patients (47%) had attained an EIR (all patients with MM). Severe COVID-19 infection requiring hospitalization occurred in 6 patients, all of whom had MM. There were no deaths related to COVID-19, and the treatment included antiviral therapy, corticosteroids, protocol-directed treatment, and best supportive care.

Discussion

We performed a prospective study to investigate humoral responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with MM and WM. Our findings show that the majority of patients exhibited low antibody responses to the primary SARS-CoV-2 vaccination series. Only 47% of patients with MM and 25% of patients with WM achieved an EIR to the primary vaccination series. These results add to the collective evidence of low vaccine responses against SARS-CoV-2, seasonal influenza, and S pneumoniae in patients with MM and WM22,23,27,28,30-34 and highlights that humoral immune dysfunction is a hallmark of both these hematologic malignancies.

An important finding was the benefit of booster vaccinations on improving EIR rates against SARS-CoV-2. Despite low responses to the primary SARS-CoV-2 vaccination series, we show, to our knowledge, for the first time that 2 booster vaccinations can lead to an EIR in nearly 90% of patients with MM and WM. This response rate compares favorably to that described with only 1 booster vaccination36 and indicates that repeated antigen exposure through booster vaccinations may overcome the impaired humoral response intrinsic to MM and WM. A dose-response relationship with immunogenicity has also been reported with the influenza vaccine in patients with MM.24 Compared to a single standard vaccine (20%), the use of a 2-dose series with a high-dose influenza vaccine resulted in antibody production in 47% and 65% of patients after 1 and 2 doses, respectively.24 Preliminary results from a recent randomized trial also showed that using a 3-dose series of high-dose influenza vaccine at 0, 2, and 4 months significantly improved immunogenicity compared to 1 high-dose vaccination.25 Collectively, these results may also explain our observation of higher vaccine responses with mRNA-1273 than with BNT162b2. Although both vaccines encode nearly the same product, the mRNA-1273 formulation used during the study period contained a higher mRNA dose than BNT162b2 (100 μg vs 30 μg),37,38 suggesting that the higher antigen exposure with mRNA-1273 accounts for the differences in response rates.29,34

Our study provides the framework to herald the development of novel vaccination strategies in patients with MM and WM. The dose-response relationship between SARS-CoV-2 booster vaccinations and antibody production demonstrates that repeated antigen exposure is a strategy to improve immunogenicity in patients with MM and WM. Using a high-dose vaccine is an alternative strategy, as first described with the seasonal influenza vaccine in patients with MM.24 These strategies should be prospectively evaluated in patients with MM and WM for other vaccine-preventable pathogens, such as S pneumoniae, respiratory syncytial virus, and herpes zoster. In particular, there is an urgent need to improve protection against invasive pneumococcal disease in patients with MM, who have a 154-fold increased risk of infection compared to the general population and a case fatality rate of 18%.39 There are currently 4 commercially available vaccines against S pneumoniae (ie, PCV13, PCV20, PCV21, and PPSV23), and novel pneumococcal vaccine schedules that increase antigen exposure should be investigated in patients with MM.

In contrast to prior studies, we investigated the effector functions of antispike antibodies produced after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Despite the production of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, we show that patients with MM and WM have decreased antibody-mediated effector functions (eg, cellular and neutrophil phagocytosis and NK-cell cytotoxicity). The discovery of impaired opsonophagocytic function indicates that humoral immune dysfunction in patients with MM and WM extends beyond hypogammaglobulinemia. Moreover, it may provide a mechanistic insight to explain the breakthrough COVID-19 infections we and others have observed despite antibody production after vaccination.40 Although we did not investigate the role of T-cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in this study, previous reports indicate such impairments exist in patients with MM and WM and likely contribute to breakthrough infections.32,41,42 Taken together, these findings highlight the need for ongoing strategies beyond vaccination in managing COVID-19 in patients with MM and WM. This includes the use of IV immunoglobulin, monoclonal antibodies (eg, pemivibart), and antiviral agents (eg, remdesivir and nirmatrelvir-ritonavir), especially because immunocompromised patients remain at high risk for severe COVID-19 even in the postpandemic era.43

Specific antineoplastic therapies adversely affected responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Similar to previous studies,30-32,34,44,45 agents that deplete the B-cell and plasma cell compartments and cause hypogammaglobulinemia, such as daratumumab, isatuximab, rituximab, and BTKi, were associated with lower vaccine responses. In addition, corticosteroids were linked to reduced responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. We could not assess the impact of BCMA-directed therapies (eg, bispecific antibodies and chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy) due to limited number of patients because the study was initiated early in the COVID-19 pandemic, before the approval of any BCMA-directed therapies. However, we anticipate similarly low vaccine responses given the B-cell aplasia and hypogammaglobulinemia associated with these treatments.19 Timing the administration of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccination around these offending antineoplastic agents whenever possible may be a strategy to enhance immunogenicity. The International Myeloma Working Group infection guidelines recommend this strategy for other vaccinations and should be extended to patients with MM and WM receiving the SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.5 In patients with WM, temporary interruption of BTKi peri-vaccination was evaluated as a potential strategy to improve immunogenicity, but the increased antibody production was only transient.46 Caution is needed with this approach because temporary interruption of BTKi is associated with withdrawal syndrome and shorter progression-free survival in patients with WM.47,48 By contrast, in patients with MM, holding monoclonal antibody therapy around vaccination is both reasonable and feasible and, in the context of combination therapy, is unlikely to result in disease progression in the majority of patients.49,50

This multicenter study has several important strengths, including a prospective design, high rates of booster vaccination, and functional studies examining the antispike antibodies produced after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. A limitation is the lack of a comparator group of healthy individuals, although earlier studies established an impaired humoral response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with MM and WM.27,28,30-33 This study was also not designed to assess vaccine effectiveness against COVID-19 infection, and antibody levels are used are surrogates. We defined an adequate immune response (ie, EIR) as an antispike antibody titer >250 U/mL, similar to a prior study’s evaluation of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with MM.29 However, there is no clear antibody titer to define protection against SARS-CoV-2 in patients with MM and WM. This is further emphasized by our data showing that antibody-mediated effector cell dysfunction can occur despite antibody production. Notably, this study was not designed to compare vaccine responses between patients with MM and WM, and any direct comparison would be confounded by differences in treatment regimens and comorbidities. Lastly, the rate of infection overall and hospitalization for severe disease without any mortality is encouraging and collectively reflects the progress in vaccination, treatment, and supportive care during the pandemic.51,52

In summary, this prospective study demonstrates that patients with MM and WM have impaired humoral responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, including both antibody production and antibody-mediated effector cell function. Antineoplastic therapies that deplete the B-cell and plasma cell compartments adversely affected vaccine responses, but the 2 booster vaccinations against SARS-CoV-2 significantly improved immunogenicity. Unlike the above mentioned influenza vaccine schedules in MM and WM adding a booster after 1 to 3 months to align with seasonal risk, SARS-CoV-2 remains a year-round threat. In our study, the median time between booster doses was ∼5 to 6 months. These findings support the need for updated SARS-CoV-2 booster doses twice per year to enhance and sustain protective immunity. Our study provides a framework for the development of vaccination strategies specific to patients with MM and WM.

Acknowledgments

Support for this study was provided by the Jonathan Aibel and Jule Rohwein Fund, the Cathy and James Stone Fund, the Rob and Fran Silverman Fund, and the Jon Orszag and Mary Kitchen Fund.

Authorship

Contribution: A.R.B. conceived the idea; M.L., Z.B., R.N.-M., M.G., M.L.G., K.L., L.P., and R.V. collected data; J.N.G., M.L., G.A., and N.H. analyzed data; S.R.S., C.S.M., A.J.Y., N.S.R., E.A., J.B., C.H., O.N., J.J.C., C.F., P.G.R., and E.O. enrolled patients in the study; A.R.B. and J.N.G. wrote the initial manuscript draft; and all authors aided in interpreting data and critically reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.R.B. received honoraria/research funding from Adaptive Biotechnologies, BeiGene, CSL Behring, Genzyme, Karyopharm, Pharmacyclics, and Sanofi. J.J.C. received honoraria from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Cellectar, Johnson & Johnson (J&J), Kite, Loxo, and Pharmacyclics; and research funding from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Cellectar, Loxo, and Pharmacyclics. S.P.T. received honoraria/research funding from ADC Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, and BeiGene. S.R.S. received honoraria/research funding from ADC Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, and BeiGene. P.G.R. received honoraria/research funding from Celgene/Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Karyopharm, Oncopeptides, Regeneron, and Sanofi. A.J.Y. reports consulting for AbbVie, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Amgen, BMS, Celgene, GSK, J&J, Karyopharm, Oncopeptides, Pfizer, Prothena, Regeneron, Sanofi, Sebia, and Takeda; and research funding to institution from Amgen, BMS, GSK, J&J, and Sanofi. M.L. received honoraria from Genmab, Sanofi, MJH Life Sciences, Genentech, Center for Business Models, and C4X Discovery. C.S.M. has served on the scientific advisory board of Adicet Bio; reports consultancy/honararia form Genentech, Nerviano, Secura Bio, and Oncopeptides; and research funding from EMGD Serono, Karyopharm, Sanofi, Nurix, BMS, H3 Biomedicine/Eisai, Springworks, Abcuro, Novartis, and Opna Bio. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Andrew R. Branagan, Center for Multiple Myeloma, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit St, Boston, MA 02114; email: abranagan@mgh.harvard.edu.

References

Author notes

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Andrew R. Branagan (abranagan@mgh.harvard.edu).