Key Points

A single A-to-T base pair mutation in the enhancer ∼117 kb upstream of GATA2 drives allelic imbalance and overexpression of GATA2.

The mutation segregates with MonoMAC disease across a large kindred, suggesting overexpression of GATA2 as a novel cause of GATA2 deficiency.

Abstract

Mutations in the transcription factor GATA2 can cause MonoMAC syndrome, a GATA2 deficiency disease characterized by several findings, including disseminated nontuberculous mycobacterial infections, severe deficiencies of monocytes, natural killer cells, and B lymphocytes, and myelodysplastic syndrome. GATA2 mutations are found in ∼90% of patients with a GATA2 deficiency phenotype and are largely missense mutations in the conserved second zinc-finger domain. Mutations in an intron 5 regulatory enhancer element are also well described in GATA2 deficiency. Here, we present a multigeneration kindred with the clinical features of GATA2 deficiency but lacking an apparent GATA2 mutation. Whole genome sequencing revealed a unique adenine-to-thymine variant in the GATA2 –110 enhancer 116,855 bp upstream of the GATA2 ATG start site. The mutation creates a new E-box consensus in position with an existing GATA-box to generate a new hematopoietic regulatory composite element. The mutation segregates with the disease in several generations of the family. Cell type–specific allelic imbalance of GATA2 expression was observed in the bone marrow of a patient with higher expression from the mutant-linked allele. Allele-specific overexpression of GATA2 was observed in CRISPR/Cas9-modified HL-60 cells and in luciferase assays with the enhancer mutation. This study demonstrates overexpression of GATA2 resulting from a single nucleotide change in an upstream enhancer element in patients with MonoMAC syndrome. Patients in this study were enrolled in the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases clinical trial and the National Cancer Institute clinical trial (both trials were registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT01905826 and #NCT01861106, respectively).

Introduction

The MonoMAC syndrome is a bone marrow failure syndrome first described in 2011.1-4 Its name derives from the distinguishing clinical features of the syndrome, including severe deficiency of monocytes and frequent infections with Mycobacterium avium complex organisms.5 Severe deficiencies in dendritic cells, B cells, and natural killer (NK) cells are also observed. Patients frequently present in adolescence with immunodeficiencies because of monocytopenia and other cytopenias and can progress to myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), or chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Disease progression is often accompanied by the appearance of cytogenetic abnormalities, particularly trisomy 8 and monosomy 7. Other common symptoms include a hypocellular bone marrow, immune deficiency with refractory human papilloma virus (HPV) infections, as well as other opportunistic bacterial and fungal infections.6-8

Heterozygous germ line mutations in the transcription factor GATA2 are found in most patients with MonoMAC, leading to the disease being named GATA2 deficiency syndrome.9 The lack of homozygous or compound heterozygous GATA2 mutations implicates haploinsufficiency, which is consistent with its pattern of dominant inheritance.10,11 Over 350 germ line mutations have been documented, and most of these are either missense mutations in the conserved zinc-finger domains or truncation mutations in other regions of the gene.12 In addition, 2 regulatory mutations in intron 5 have been identified: a point mutation in several unrelated families that mutates a Fli1 transcription factor binding site from the intronic enhancer element, and one 3 generation family, with one member who underwent transplantation, harboring a 28 bp deletion that deletes the E-box from the composite element in intron 5.13 Approximately 5% to 10% of patients with all of the hallmarks of GATA2 deficiency lack a GATA2 gene mutation.8,14

The GATA2 protein binds directly to a consensus DNA sequence (A/T)GATA(A/G) in the regulatory regions of target genes, including a self-regulatory loop in its own promoter and enhancer elements.10 The coupling of an E-box (CANNTG) upstream of a GATA element separated by an 8 bp spacer forms a composite element, a critical regulatory element at many hematopoietic loci.15 Murine studies have shown that composite elements at +9.5kb (corresponding to the human intron 5 enhancer) and −77kb distal to Gata2 (human −110 enhancer) are essential for normal hematopoiesis.12,16-18 The −110 enhancer is relocated in the myeloid malignancy–associated inv(3:3)(q21q26) inversion, resulting in the downregulation of GATA2 and the upregulation of EVI1.19,20

We investigated an extended multigeneration family with the hallmark symptoms of the MonoMAC syndrome who lacked a coding sequence or intron 5 mutation in GATA2. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) revealed a unique single base pair variant in the highly conserved −110 distal GATA2 enhancer. This mutation created a new GATA element consensus 8 bp downstream of an existing E-box, thus generating a new composite element. GATA2 expression studies on patient samples, CRISPR-modified cell lines, and luciferase assays demonstrated aberrant GATA2 expression from this altered enhancer.

Methods

Patient samples

The clinical protocols were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Clinical Research Center. The procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975, as revised in 2008. All participants gave written informed consent. Patients were enrolled in the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases clinical trial 13-I-1057 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01905826) and National Cancer Institute clinical trial 13-C-0132 (https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01861106). Patient peripheral blood and bone marrow samples were collected and genotyped using standard techniques.

DNA sequencing

Sequencing was performed on genomic DNA (gDNA) isolated from peripheral blood leukocytes. Whole exome sequencing (WES) is described elsewhere; patients 1 and 2 here are patients 24 and 26, respectively, in Table 1; supplemental Figure 2 in West et al.21 WGS was done at Psomagen (Rockville, MD). Direct DNA sequencing was done at the National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research Genomics Core. Please refer to supplemental Methods.

Blood and bone marrow results

| Sample . | Patient 1 2012 . | Patient 1 2013 . | Normal range (female) . | Patient 2 2011 . | Patient 2 2014 . | Patient 2 2016 . | Normal range (male) . | Patient 2 mother (carrier) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (K/μL) | 2.54 | 2.22 | 3.98-10.04 | 2.5 | 2 | 2.64 | 4.23-9.07 | 5.41 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.9 | 10.7 | 11.2-15.7 | 13.6 | 13.5 | 12 | 13.7-17.5 | 13.9 |

| Platelet count (K/μL) | 202 | 167 | 173-369 | 178 | 219 | 243 | 161-347 | 258 |

| Neutrophils, absolute (K/μL) | 0.81 | 0.33 | 1.56-6.13 | 2 | 1 | 1.74 | 1.78-5.38 | 3.34 |

| Monocytes, absolute (K/μL) | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.24-0.86 | 0 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.30-0.82 | 0.45 |

| CD3+ T cells, absolute (cells/μL) | 1663 | 1498 | 714-2266 | nd | 772 | 640 | 714-2266 | 998 |

| CD19+/CD20+ B cells, absolute (cells/μL) | 14 | 27 | 59-329 | nd | 9 | 6 | 61-321 | 213 |

| NK cells, absolute (cells/μL) | 10 | 22 | 126-729 | nd | 126 | 93 | 126-729 | 150 |

| Trisomy 8 (%) | 70 to <80 | 85 | 0 | 50 | 85 | 80 | 0 | 0 |

| Bone marrow cellularity (%) | 5-10 | 5-10 | 60-70 | 15-25 | 25 | 30 | 60-70 | 30-40∗ |

| Sample . | Patient 1 2012 . | Patient 1 2013 . | Normal range (female) . | Patient 2 2011 . | Patient 2 2014 . | Patient 2 2016 . | Normal range (male) . | Patient 2 mother (carrier) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (K/μL) | 2.54 | 2.22 | 3.98-10.04 | 2.5 | 2 | 2.64 | 4.23-9.07 | 5.41 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.9 | 10.7 | 11.2-15.7 | 13.6 | 13.5 | 12 | 13.7-17.5 | 13.9 |

| Platelet count (K/μL) | 202 | 167 | 173-369 | 178 | 219 | 243 | 161-347 | 258 |

| Neutrophils, absolute (K/μL) | 0.81 | 0.33 | 1.56-6.13 | 2 | 1 | 1.74 | 1.78-5.38 | 3.34 |

| Monocytes, absolute (K/μL) | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.24-0.86 | 0 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.30-0.82 | 0.45 |

| CD3+ T cells, absolute (cells/μL) | 1663 | 1498 | 714-2266 | nd | 772 | 640 | 714-2266 | 998 |

| CD19+/CD20+ B cells, absolute (cells/μL) | 14 | 27 | 59-329 | nd | 9 | 6 | 61-321 | 213 |

| NK cells, absolute (cells/μL) | 10 | 22 | 126-729 | nd | 126 | 93 | 126-729 | 150 |

| Trisomy 8 (%) | 70 to <80 | 85 | 0 | 50 | 85 | 80 | 0 | 0 |

| Bone marrow cellularity (%) | 5-10 | 5-10 | 60-70 | 15-25 | 25 | 30 | 60-70 | 30-40∗ |

Peripheral blood and bone marrow characteristics in patients 1 and 2 with MonoMAC.

Blood cell counts and bone marrow cytogenetics for patient 1 before bone marrow transplant (BMT), and patient 2, 5 and 2 years before and just before BMT. The asymptomatic carrier mother for patient 2 is also shown. The NIH Clinical Center normal ranges for adult female (patient 1) and adult male (patient 2) are given.

nd, not defined.

Indicates normal for age.

Statistical analyses and graphing were performed using Prism, version 9.3.1 (GraphPad Software, Inc, San Diego, CA). Variant bam files were reviewed with the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV; version 2.11.1, http://software.broadinstitute.org), and additional sequence analysis performed with MacVector, version 18.2.3 (MacVector, Inc, Apex, NC). Haplotyping was done by visual alignment of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and variant phasing confirmed with trioPhaser22 and SHAPEIT4.23

Cell sorting bone marrow and RNA isolation

Bone marrow pathology and diagnostic flow cytometry were done as previously described.24 Bone marrow collected from patient 2 was subjected to fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) using antibody staining. Cell subsets were collected directly into Trizol (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for RNA isolation. Total RNA was isolated from whole blood samples using the PAXgene Blood RNA Tube system (Becton, Dickinson & Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ). The complementary DNA (cDNA) for sequencing and expression analysis was made and amplified using the Superscript III One-Step reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR) kit (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Please refer to supplemental Methods.

CRISPR/Cas9 mediated genome editing

The promyeloblastic cell line HL-60 (CLL-240) was acquired from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and cultured under the recommended conditions. The CRISPR/Cas9 ribonuclear particle was assembled in vitro as described by the manufacturer instructions (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA). Fluorescently labeled donor DNA25 and fluorescently labeled tracrRNA were combined with the ribonuclear particle and used to transfect HL-60 cells. Cells were sorted by FACS and heterozygous A-to-T mutants identified by DNA sequencing. Please refer to supplemental Methods.

GATA2 expression

Total RNA was isolated from 1 × 107 cultured cells using the PAXgene Blood RNA Tube system or RNAeasy kit (Qiagen). The cDNA was made with the Qiagen One-Step Viral Reverse Transcriptase Kit (Qiagen, Gaithersburg, MD) using manufacturer instructions. Absolute quantification of GATA2 messenger RNA (mRNA) was done by digital PCR (dPCR) using the QIAcuity Digital PCR system (Qiagen) with probe sets from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA) and analyzed with the QIAcuity Software Suite, version 1.2. Please refer to supplemental Methods.

Transcriptome sequencing (RNA-Seq) was done at Psomagen (Rockville, MD) on libraries constructed with mRNA using the Illumina TruSeq system. The read count was normalized to fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads.

Luciferase assays

The luciferase reporter gene plasmids, pGL4.10[luc2] and pGL4.13[luc2/SV40], and the transfection control plasmid pGL4.75[hRluc/CMV] were acquired from Promega (Madison, WI). The pGL4.10-GATA2Enh plasmids were made with the GATA2 promoter corresponding to the H1 enhancer activity-by-contact element26 and a 477 bp fragment of the GATA2 enhancer spanning the A-to-T mutation. Plasmids were transfected into HL-60 cells, and luminescence was measured using the Dual-Glo Reagent Kit (Promega). Please refer to supplemental Methods.

Results

Patient 1

The index patient is currently a woman aged 38 years who presented at the age of 17 with disseminated Herpes Simplex Virus-2. Six years later, she developed extensive genital HPV, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia III, and anal intraepithelial neoplasia III. At the age of 27, she developed a refractory cytopenia; a bone marrow biopsy was 5% to 10% cellular with dysplastic features. Cytogenetics showed 70% of metaphases displayed trisomy 8. At the NIH, her peripheral blood white blood cell count (WBC) was low at 2500/μL (Table 1), with low absolute neutrophil, monocyte, NK, and CD19+ B-cell counts. Her bone marrow biopsy was markedly hypocellular with trilineage hypoplasia (Figure 1A-B), with 80% of metaphases displaying trisomy 8. Flow cytometry showed a profound loss of monocytes typical of GATA2 deficiency (Figure 1E). Her family history was notable for a paternal uncle who died in his early thirties from aplastic anemia/MDS and a paternal second cousin in his late twenties with MDS and trisomy 8 (patient 2) (Figure 2). Two great aunts died from mycobacterial infections. Her father was evaluated at age 67 and had a normal complete blood count (CBC) and normal T-cell, B-cell, and NK-cell (TBNK) counts. Her brother was evaluated at the NIH at age 27 and had normal CBC and TBNK counts. At age 28, she underwent a 10 of 10 matched unrelated donor peripheral blood stem cell transplant after conditioning with busulfan and fludarabine, receiving 8 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg.27 She remains well with a normal CBC, a normal bone marrow, and 100% donor chimerism with normal cytogenetics 10 years after transplant.

Bone marrow aspirate smears from patients 1 and 2. (A) Patient 1 sample with markedly hypocellular marrow biopsy with trilineage hypoplasia (original magnification ×100 with hematoxylin and eosin [H&E] staining). (B) Patient 1 paucicellular smear with erythroid cells and a dysplastic multinucleated cell shown on inset (original magnification ×1000 with Wright-Giemsa stain). (C) Patient 2 sample with hypocellular bone marrow biopsy (original magnification ×100 with H&E staining). (D) Patient 2 with dysplastic megakaryocytes with separated nuclear lobes noted on aspirate smear (1000× with Wright-Giemsa stain). (E) Flow cytometry analysis of bone marrow samples. Scatter plots are shown for monocytes (CD14 and CD64), dendritic cells (CD123 and HLA DR), and lymphocytes (CD10 and CD20). The indicated population is marked with the square and percentage given above. Samples are shown for a normal control, a typical patient with GATA2 deficiency (R396Q), and the 2 patients in this study.

Bone marrow aspirate smears from patients 1 and 2. (A) Patient 1 sample with markedly hypocellular marrow biopsy with trilineage hypoplasia (original magnification ×100 with hematoxylin and eosin [H&E] staining). (B) Patient 1 paucicellular smear with erythroid cells and a dysplastic multinucleated cell shown on inset (original magnification ×1000 with Wright-Giemsa stain). (C) Patient 2 sample with hypocellular bone marrow biopsy (original magnification ×100 with H&E staining). (D) Patient 2 with dysplastic megakaryocytes with separated nuclear lobes noted on aspirate smear (1000× with Wright-Giemsa stain). (E) Flow cytometry analysis of bone marrow samples. Scatter plots are shown for monocytes (CD14 and CD64), dendritic cells (CD123 and HLA DR), and lymphocytes (CD10 and CD20). The indicated population is marked with the square and percentage given above. Samples are shown for a normal control, a typical patient with GATA2 deficiency (R396Q), and the 2 patients in this study.

Pedigree for the family with MonoMAC syndrome. Family pedigree with the generation indicated on the left. Bone marrow failure cases are shown with full shading, confirmed carriers of the GATA2 enhancer mutant are shown with left half shading, and other obligate carriers are shown with a shaded inner circle. The patients who underwent transplantation in this study are indicated with red arrows, and patient 1 is the female on the left, and patient 2 is the male on right. Patients 3 and 4 are shown with blue arrows. Suspected MonoMAC syndrome cases are shown with upper left quarter shading. Deceased individuals are indicated with a diagonal line with the age of death in years indicated when known (d). A diamond indicates individuals of unspecified sex with the number given or “n” for an undetermined number of individuals. An asterisk (∗) indicates genotyped individuals for the GATA2 enhancer mutation (red, RefSeq allele; blue, novel variant; and black, RefSeq in individuals not in line for inheritance of the novel variant). Clinical data for other family members are indicated when known. AA, aplastic anemia; ca, cancer; TB, tuberculosis.

Pedigree for the family with MonoMAC syndrome. Family pedigree with the generation indicated on the left. Bone marrow failure cases are shown with full shading, confirmed carriers of the GATA2 enhancer mutant are shown with left half shading, and other obligate carriers are shown with a shaded inner circle. The patients who underwent transplantation in this study are indicated with red arrows, and patient 1 is the female on the left, and patient 2 is the male on right. Patients 3 and 4 are shown with blue arrows. Suspected MonoMAC syndrome cases are shown with upper left quarter shading. Deceased individuals are indicated with a diagonal line with the age of death in years indicated when known (d). A diamond indicates individuals of unspecified sex with the number given or “n” for an undetermined number of individuals. An asterisk (∗) indicates genotyped individuals for the GATA2 enhancer mutation (red, RefSeq allele; blue, novel variant; and black, RefSeq in individuals not in line for inheritance of the novel variant). Clinical data for other family members are indicated when known. AA, aplastic anemia; ca, cancer; TB, tuberculosis.

Patient 2

The patient is currently a male aged 34 years who presented at age 18 with a skin infection in the right knee and a low WBC with a normal hemoglobin and platelet count. A bone marrow exam demonstrated hypocellularity with normal cytogenetics. However, a bone marrow exam 2 years later was 15% to 20% cellular with trisomy 8 in 50% of the metaphases (Table 1). He was diagnosed with aplastic anemia and treated with a course of horse-anti-thymocyte globulin (H-ATG) and cyclosporine. He developed serum sickness requiring a prolonged course of corticosteroids leading to avascular necrosis in both hips requiring bilateral hip arthroplasty. A bone marrow exam 1 year later showed 25% cellularity (Figure 1C), with trisomy 8 in 85% of metaphases. There were atypical megakaryocytes with separated nuclear lobes in the aspirate smear (Figure 1D). Flow cytometry showed a loss of monocytes in the marrow (Figure 1E). He was treated with Neulasta monthly for low WBCs. He was seen at the NIH at the age of 22. At that time, his WBC was 2500/μL, and he had a low monocyte count (Table 1). He returned at the age of 25 and his WBC had dropped to 2000/μL, and his absolute neutrophil count (ANC) dropped to 1000/μL. At that time, his NK cell count and CD19+ B cells were also low. The bone marrow biopsy was 25% cellular with myelodysplasia and 85% of metaphases with trisomy 8. He underwent a 10 of 10 matched unrelated donor bone marrow transplant at age 27.27 He remains well with a normal CBC 7 years after transplant, with 100% donor chimerism at the time of publication.

The family history is notable in several regards (Figure 2). His second cousin on his maternal side is the index patient in this report (Figure 2). His maternal grandmother died of tuberculosis of the bone. His 69-year-old mother is followed at the NIH and is in good health with a normal CBC, normal TBNK, and a normal bone marrow with normal cytogenetics. His father is in good health, as are his 36-year-old sister and 30-year-old brother. They were evaluated at the NIH at the age of 22 and 28, respectively, and both had normal CBC and TBNK panels.

Patients 3 and 4

The third and fourth presumptively affected family members are 2 deceased individuals; a first cousin, once removed (1r), and his daughter, a second cousin to patients 1 and 2 (Figure 2). The first cousin (1r) presented at age 16 years with pneumonia. He proceeded to develop MDS with the absence of monocytes along with lymphedema, another symptom common in GATA2 deficiency. He died at age 37 years with what was described as “like leukemia” disease. His daughter, a second cousin to the first 2 patients, developed anal and vaginal cancer requiring radiation therapy along with “bone marrow problems” with anemia and low WBC. She died at the age 37 years from complications of bowel surgery. These patients were not evaluated at the NIH.

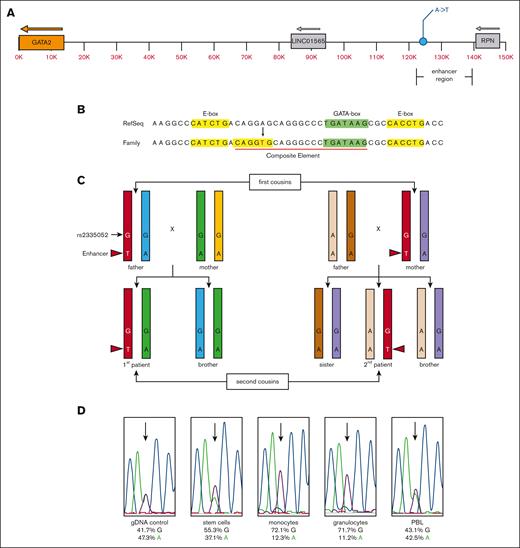

DNA sequence analysis

Patients 1 and 2 both displayed clinical evidence of MonoMAC syndrome, but no GATA2 coding, splicing or intronic enhancer13 mutations were detected by WES of peripheral blood cells.21 WGS was used to identify variants outside the coding sequences covered by WES. These data revealed a novel adenine-to-thymine variant 116 855 bp upstream of the GATA2 ATG start site in the 2 patients and 1 parent in each sibship, consistent with autosomal dominant inheritance (Figure 3A) (supplemental Table 1). The WGS variant allele frequency averaged 56 % A/44 % T for the 2 patients and their respective parent, with an average read depth of 66 reads. The variant was not detected in other family members, with a read depth of ∼40 reads. These results were confirmed with direct DNA sequencing. This variant lies within the P300 element of the GATA2 distal enhancer. Alignment of the human GATA2 enhancer sequence with mouse Gata2 showed the variant lied within the most conserved region of the enhancer that includes a CD34+-specific DNase I hypersensitive site (supplemental Figures 1-2). The A-to-T mutation created a new consensus for an E-box regulatory element (CANNTG) 8 bp upstream of an existing GATA-box regulatory element (W)GATAA(R) making a new composite element (E-box-N8-GATA-box)28 (Figure 3B). Targeted direct DNA sequencing on several members of the kindred showed the enhancer variant was absent in all other asymptomatic family members tested (Figures 2C, and 3C).

Schematic representation of the novel GATA2 enhancer variant and expression allelic imbalance. (A) Diagram of the GATA2 locus with the relative positions of the GATA2 gene (orange), the minimal translocated super enhancer region,16,17,19,29,30 corresponding to the −110 region enhancer containing the unique A-to-T variant (GRCh38.p7 chr3:128,604,048) and neighboring LINC01565 and RPN genes. (B) Genomic sequence with the RefSeq and novel family variant is indicated (red font). The position of the E-box (yellow highlight), GATA-box (green highlight), and composite element (red underline) are indicated. (C) Diagram of the haplomap for the patients and their parents based on WGS and direct DNA sequencing (refer to supplemental Tables 1-2). The chromosome strands are indicated by color with the shared enhancer strand among carrier and affected individuals colored red. The position and genotype of the unique enhancer variant are indicated with the nucleotide base and red arrowhead. Each other color represents the other GATA2 allele within each respective individual. The relative position and genotype of the fiducial SNP rs2335052 is also indicated. The rs2335052 population has a variant allele frequency of ∼20% (dbSNP Build 155), and it has no known clinical significance (ClinVar ID# 134467). (D) Direct DNA sequencing traces from gDNA (control) and cDNA from stem cells (CD34+), monocytes (CD14+), granulocytes, and PBL. The relative signal intensity for the guanine (G) (black) and adenine (A) (green) bases at rs2335052 (arrows) are given below each sample trace as a percent of total signal for all 4 nucleotide bases. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry notation is used to designate nucleotide sequence.

Schematic representation of the novel GATA2 enhancer variant and expression allelic imbalance. (A) Diagram of the GATA2 locus with the relative positions of the GATA2 gene (orange), the minimal translocated super enhancer region,16,17,19,29,30 corresponding to the −110 region enhancer containing the unique A-to-T variant (GRCh38.p7 chr3:128,604,048) and neighboring LINC01565 and RPN genes. (B) Genomic sequence with the RefSeq and novel family variant is indicated (red font). The position of the E-box (yellow highlight), GATA-box (green highlight), and composite element (red underline) are indicated. (C) Diagram of the haplomap for the patients and their parents based on WGS and direct DNA sequencing (refer to supplemental Tables 1-2). The chromosome strands are indicated by color with the shared enhancer strand among carrier and affected individuals colored red. The position and genotype of the unique enhancer variant are indicated with the nucleotide base and red arrowhead. Each other color represents the other GATA2 allele within each respective individual. The relative position and genotype of the fiducial SNP rs2335052 is also indicated. The rs2335052 population has a variant allele frequency of ∼20% (dbSNP Build 155), and it has no known clinical significance (ClinVar ID# 134467). (D) Direct DNA sequencing traces from gDNA (control) and cDNA from stem cells (CD34+), monocytes (CD14+), granulocytes, and PBL. The relative signal intensity for the guanine (G) (black) and adenine (A) (green) bases at rs2335052 (arrows) are given below each sample trace as a percent of total signal for all 4 nucleotide bases. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry notation is used to designate nucleotide sequence.

Haplomaps of the GATA2 locus for the 2 patients and their first-degree relatives confirmed that the enhancer variant was within the GATA2 allele shared by the affected individuals and their respective parent and not present in the other family members (Figure 3C; supplemental Tables 1-2).

GATA2 cell-type allelic imbalance

The effect of the enhancer mutation on GATA2 gene expression was investigated using cells isolated from the bone marrow of the second patient before transplant. Patient 2 was heterozygous for the common exon variant rs2335052 (G/A), which facilitated the use of the G residue as a fiducial marker to identify the enhancer mutation allele. The G allele was inherited maternally and mapped to the GATA2 enhancer mutation allele (Figure 3C; supplemental Table 1). A bone marrow aspirate from patient 2 was sorted using FACS to examine stem cells, monocytes, and granulocytes. GATA2 cDNA was synthesized and used for direct DNA sequencing. This showed a cell-type specific allelic imbalance between the wildtype (wt) and enhancer-mutant alleles of GATA2 (Figure 3D). All cell types examined showed higher expression for the enhancer mutation associated GATA2 allele. This expression bias was most pronounced in monocytes and granulocytes. The allelic bias observed in the peripheral blood lymphocyte (PBL) sample was within the variation among normal control samples; therefore, its significance is not known. A PBL sample from the mother of the patient 2 showed an allelic imbalance for the mutant enhancer allele (62%) at common SNP rs1573858, which was also within the variation among normal control samples.

CRISPR/Cas9 modified cell lines

The biological effect of the enhancer mutation was investigated using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing to engineer the HL-60 promyelocytic leukemia cell line to have the A-to-T enhancer variant. The resultant cell line was grown under standard conditions, and GATA2 RNA expression was investigated by dPCR and RNA-Seq (Figure 4) (supplemental Figures 3-4). Expression of GATA2 mRNA in HL-60 cells with the A-to-T enhancer mutation was modestly, but consistently, higher than wt cells (Figure 4A). As the cell density increased in culture, this difference became more pronounced (Figure 4B). GATA2 expression remained constant in the wt cells but it increased with cell density in the mutant enhancer cells (supplemental Figure 4).

GATA2 expression in CRISPR/Cas9-modified HL-60 cultured cells. (A) Grand means from several independent dPCR experiments. The P values from t tests are shown in each panel when significant. The TBP and HPRT1 genes were used as reference control genes. The GATA2:TBP signal ratio for the wt enhancer is 1.067 ± 0.030 and for the A-to-T mutant is 1.093 ± 0.0209, and the GATA2:HPRT1 signal ratio for wt is 0.3065 ± 0.0215 and for the A-to-T mutant is 0.3353 ± 0.0173. (B) HL-60 dPCR mutant:wt cell GATA2 expression ratio normalized to HPRT1 expression. Expression increased in the mutant cell line through 4 days of continuous growth, with the average mutant:wt ratio of 1.269 ± 0.220. (C) GATA2 expression measured with rs2335052 allele-specific dPCR probes and normalized with TBP. The total expression is the sum of the 2 rs2335052 probes; wt 0.4623 ± 0.01968, mutant 0.5964 ± 0.02892 when normalized to TBP (t test; P ≤ .0001). (D) Ratio of the reference and alternate sequence alleles at rs2335052 in wt (1.007 ± 0.04127) and A-to-T enhancer mutant cell lines (1.408 ± 0.04411).

GATA2 expression in CRISPR/Cas9-modified HL-60 cultured cells. (A) Grand means from several independent dPCR experiments. The P values from t tests are shown in each panel when significant. The TBP and HPRT1 genes were used as reference control genes. The GATA2:TBP signal ratio for the wt enhancer is 1.067 ± 0.030 and for the A-to-T mutant is 1.093 ± 0.0209, and the GATA2:HPRT1 signal ratio for wt is 0.3065 ± 0.0215 and for the A-to-T mutant is 0.3353 ± 0.0173. (B) HL-60 dPCR mutant:wt cell GATA2 expression ratio normalized to HPRT1 expression. Expression increased in the mutant cell line through 4 days of continuous growth, with the average mutant:wt ratio of 1.269 ± 0.220. (C) GATA2 expression measured with rs2335052 allele-specific dPCR probes and normalized with TBP. The total expression is the sum of the 2 rs2335052 probes; wt 0.4623 ± 0.01968, mutant 0.5964 ± 0.02892 when normalized to TBP (t test; P ≤ .0001). (D) Ratio of the reference and alternate sequence alleles at rs2335052 in wt (1.007 ± 0.04127) and A-to-T enhancer mutant cell lines (1.408 ± 0.04411).

Similar to patient 2, HL-60 cells are heterozygous at SNP rs2335052. We investigated whether the same SNP showed allelic imbalance in the modified HL-60 cells as seen in the bone marrow of patient 2 (Figure 4C). Total GATA2 expression was higher in the mutant enhancer cells (Figure 4C). This increased expression could be accounted for from the increased expression of 1 allele of the GATA2 gene (Figure 4D), because the ratio of the 2 GATA2 alleles of rs2335052 was greater in enhancer mutants.

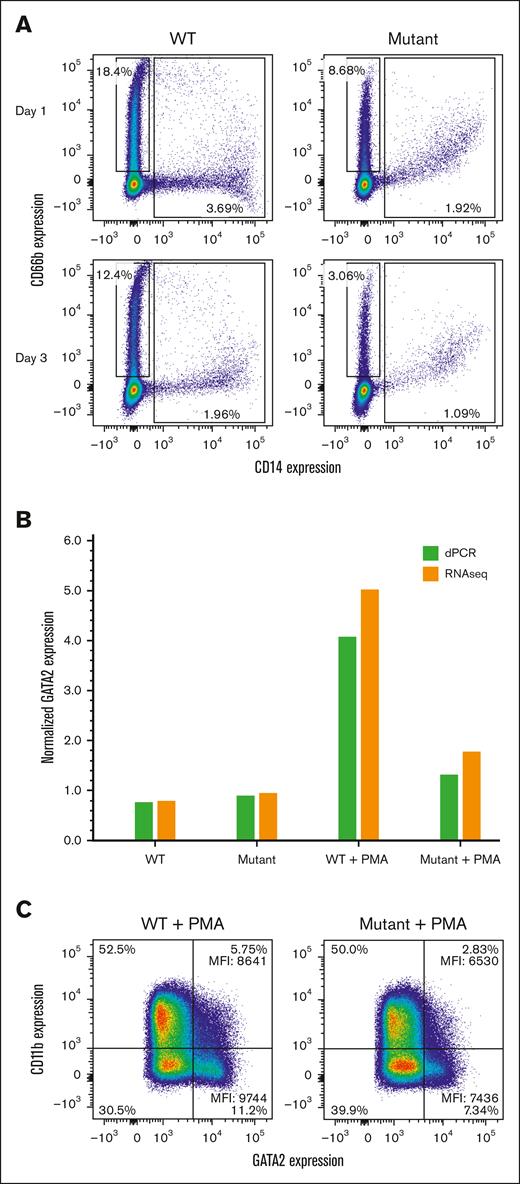

HL-60 differentiation

Because HL-60 cells can spontaneously express myeloid markers during differentiation in culture, we examined the surface expression of CD11b and CD14 to assess monocyte/macrophage differentiation and CD66b to assess neutrophil differentiation. The expression of the CD14 and CD66b differentiation markers was markedly lower in the enhancer mutant cells with indications of a less differentiated state (CD14+ CD66b+ cells) (Figure 5A). As the cells grew denser, differentiation was less pronounced in both cell lines, particularly in the enhancer mutant cells (Figure 5A, lower panel).

Effect of the enhancer mutation on HL-60 cell differentiation during growth or after PMA stimulation. (A) Comparison of neutrophil and monocyte markers on unstimulated HL-60 wt and A-to-T enhancer mutant cell lines after passage for 1 or 3 days. Cells were surface stained with an anti-human CD14 monoclonal antibody for monocyte differentiation (X-axis) and with an anti-human CD66b monoclonal antibody for neutrophil differentiation (Y-axis). Boxes indicate cells that are CD14– CD66+ (neutrophils) or CD14+ CD66b –/+ (monocytes or less differentiated cells). (B) Relative GATA2 RNA levels were measured +/− PMA by dPCR or RNA-seq: wt change 0.77 to 4.44, mutant change 0.92 to 1.47. Levels of GATA2 RNA were normalized with TBP (dPCR) or fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (RNA-seq). (C) Cells were surface stained for CD11b (Y-axis) and intracellularly stained for GATA2 (X-axis) for control (CTL) or PMA-stimulated cells. All cells expressed GATA2 and were gated into low or high expressing cells (right quadrants), with the percentages for each quadrant shown. The mean florescence intensity (MFI) values are given.

Effect of the enhancer mutation on HL-60 cell differentiation during growth or after PMA stimulation. (A) Comparison of neutrophil and monocyte markers on unstimulated HL-60 wt and A-to-T enhancer mutant cell lines after passage for 1 or 3 days. Cells were surface stained with an anti-human CD14 monoclonal antibody for monocyte differentiation (X-axis) and with an anti-human CD66b monoclonal antibody for neutrophil differentiation (Y-axis). Boxes indicate cells that are CD14– CD66+ (neutrophils) or CD14+ CD66b –/+ (monocytes or less differentiated cells). (B) Relative GATA2 RNA levels were measured +/− PMA by dPCR or RNA-seq: wt change 0.77 to 4.44, mutant change 0.92 to 1.47. Levels of GATA2 RNA were normalized with TBP (dPCR) or fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (RNA-seq). (C) Cells were surface stained for CD11b (Y-axis) and intracellularly stained for GATA2 (X-axis) for control (CTL) or PMA-stimulated cells. All cells expressed GATA2 and were gated into low or high expressing cells (right quadrants), with the percentages for each quadrant shown. The mean florescence intensity (MFI) values are given.

HL-60 cells will differentiate into an adherent macrophage-like phenotype upon stimulation with PMA (phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate).31 We investigated the effect of the enhancer variant on PMA stimulation by measuring GATA2 mRNA expression and the macrophage surface marker (CD11b) by flow cytometry (Figure 5B-C). PMA stimulation led to an increase in GATA2 mRNA expression in wt HL-60 cells, however, there was a lower response in the enhancer mutant cell line (Figure 5B). Flow cytometry with CD11b showed a somewhat higher level of macrophage-like differentiation in wt HL-60 cells than the enhancer mutant cells (Figure 5C). The difference was more pronounced when examining intracellular GATA2 protein levels for each cell type (Figure 5C). Together, these data indicate HL-60 cells with the enhancer mutant are less responsive to PMA–stimulated macrophage differentiation in GATA2+ high expressing cells.

Luciferase assays

The effect of the A-to-T mutation on enhancer activity was investigated using a luciferase reporter assay in the HL-60 cell line. Two plasmid constructs were made that express the luc2 gene by a combination of the conserved region of the GATA2 –110 enhancer, spanning the family variant, and either the SV40 promoter or the ∼1.8kb GATA2 H1 promoter element26 (Figure 6A). The SV40-based plasmid showed a 1.8-fold increase in luciferase activity from the mutant enhancer plasmid compared with the wt enhancer (Figure 6B). The H1 GATA2 promoter–based plasmid showed a 1.6-fold increase with the mutant enhancer plasmid compared with the wt enhancer (Figure 6C).

Luciferase assay for GATA2 enhancer variant activity. Plasmids expressing firefly luciferase were cotransfected with a reference plasmid expressing Renilla luciferase into HL-60 cells. The A-to-T mutant constructs are indicated as mutant. (A) Schematic diagram of the plasmid constructs used to assay enhancer activity (refer to “Methods”). (B) Plasmid containing the SV40 promoter with the wt and mutant GATA2 enhancer element. Grand means from 3 separate trials are shown with standard deviations. The normalized luminescence is plotted as relative fluorescence units (RFU). The mutant enhancer signal was significantly higher than the wt enhancer: no DNA, 6.200 ± 3.654; vector, 33.85 ± 3.623; wt, 49.10 ± 4.109; and mutant, 88.66 ± 9.860. (C) Plasmid containing the GATA2 H1 promoter fragment with the wt and mutant GATA2 enhancer element. The normalized luminescence is plotted as relative fluorescence units (RFU). Grand means from 3 separate trials are shown with standard deviations: no DNA, 0; vector, 2.667 ± 0.5774; wt, 8.000 ± 3.606; and mutant, 11.67 ± 4.509.

Luciferase assay for GATA2 enhancer variant activity. Plasmids expressing firefly luciferase were cotransfected with a reference plasmid expressing Renilla luciferase into HL-60 cells. The A-to-T mutant constructs are indicated as mutant. (A) Schematic diagram of the plasmid constructs used to assay enhancer activity (refer to “Methods”). (B) Plasmid containing the SV40 promoter with the wt and mutant GATA2 enhancer element. Grand means from 3 separate trials are shown with standard deviations. The normalized luminescence is plotted as relative fluorescence units (RFU). The mutant enhancer signal was significantly higher than the wt enhancer: no DNA, 6.200 ± 3.654; vector, 33.85 ± 3.623; wt, 49.10 ± 4.109; and mutant, 88.66 ± 9.860. (C) Plasmid containing the GATA2 H1 promoter fragment with the wt and mutant GATA2 enhancer element. The normalized luminescence is plotted as relative fluorescence units (RFU). Grand means from 3 separate trials are shown with standard deviations: no DNA, 0; vector, 2.667 ± 0.5774; wt, 8.000 ± 3.606; and mutant, 11.67 ± 4.509.

Discussion

GATA2 is a master regulator for hematopoietic stem cell and progenitor cell proliferation.32 Deleterious mutations in GATA2 result in bone marrow failure and the clinical syndrome GATA2 deficiency. The most common mutations are either missense mutations in the conserved second zinc-finger domain or nonsense mutations elsewhere in the protein.10 One common exception are intronic regulatory mutations that disrupt a composite element or its downstream FLI1 binding site.13 Approximately 10% of patients with all the disease manifestations of GATA2 deficiency lack any mutation in the coding sequencing or intronic enhancer element.

GATA2 –110 enhancer

Murine studies first identified a distal enhancer element located −77 kb from Gata2.16Gata2 expression was several fold lower in myeloid progenitor cells with a 257 bp deletion at the core of the −77 enhancer.17 This 257 bp core overlaps with the A-to-T mutation found in the MonoMAC kindred described here. The murine −77 enhancer and homologous −110 enhancer in humans include a highly conserved region that contains GATA motifs, but there is no consensus composite element.17,28 However, the mutation found in the family described here creates a composite enhancer element within this highly conserved regulatory region. Composite elements are a highly conserved regulatory motifs that are critical in hematopoiesis and bind both GATA1 and GATA2.15,17,33,29 The Gata2 +9.5 intronic composite element (human intron 5) plays an essential role in hematopoiesis and has been directly implicated in MonoMAC syndrome.34

The importance of the −110 enhancer was also demonstrated in 2014 when 2 groups described a chromosomal inversion between 3q21 and 3q26, resulting in a high-risk AML by repositioning the GATA2 upstream enhancer near the MECOM locus, which in turn, resulted in EVI1 overexpression19,20 and a decrease in GATA2 expression because of the relocation of the -110 enhancer away from the GATA2 locus. The decrease in GATA2 expression in inv(3)q21q26.2 AML is often allele specific.35

The unique variant discovered in the kindred presented here creates a composite element consensus sequence at the core of a highly conserved region of an enhancer documented to have a critical regulatory role in GATA2 expression. The inheritance pattern of this mutation matches the expected pattern for the medical history of this family.

GATA2 overexpression

Overexpression of GATA2 occurs in some patients with AML, and its high expression correlates with resistant disease and poor overall survival.6,36-38 Moreover, the overexpression of Gata2 in mouse models disrupts normal hematopoiesis.38-40 In particular, the overexpression of GATA2 leads to aberrant megakaryopoiesis, a common phenotype of MonoMAC, and, specifically, among the patients described here.41GATA2 expression appears to be exquisitely regulated in hematopoietic cells; maintenance of GATA2 within a critical physiologic window appears to be critical because ectopically increased GATA2 expression blocks differentiation.39,42

We applied CRISPR technology to create HL-60 cells with the same heterozygous genotype at the −110 enhancer as the family under study. Expression studies using dPCR and RNA-Seq showed ∼25% increase in GATA2 mRNA expression in the modified cells. Less differentiation in HL-60 cells with the enhancer mutation, particularly upon PMA stimulation to a macrophage-like phenotype, was also observed. These relatively modest differences may explain disease latency, despite its germ line inheritance. The patients described here presented with disease in their late teens. Moreover, the penetrance of GATA2 deficiency is incomplete, with estimates ranging from 20% to 50%.21,38,43-45 Examples of this incomplete penetrance are observed in the pedigree presented here, with the father of patient 1 and the mother of patient 2 being obligatory carriers. Therefore, one might expect a subtle change in GATA2 expression from this mutation. In vitro luciferase assays in HL-60 cells also showed that the mutant allele confers a higher level of GATA2 expression.

Haploinsufficiency is the likely mechanism for most germ line GATA2 mutations, therefore, a similar phenotype from overexpression might be unexpected. However, few GATA2 mutations have been tested, and there are notable exceptions, including the gain-of-function mutations L359V and G320D46,47 and the mutations R308P and S447R.10,48 Furthermore, a simple haploinsufficiency model does not explain the phenotypic complexities of some GATA2 mutations.48-50 The T354M mutation, for example, binds more tightly to PU.1 than wt GATA2 protein and skews cell fate to granulocytes.49,51 The T354M, as well as R398W, mutations also reduce wt GATA2 protein binding, suggesting a function-specific gain-of-function phenotype.49-53 The interactions between the GATA2 protein and its DNA binding-sites and protein interactions are complex and context dependent, involving cell type, protein characteristics, as well as dosage.53

Allelic imbalance

The absence of homozygous mutations in GATA2 deficiency suggests haploinsufficiency as a common mechanism for disease. Monoallelic expression of the germ line mutated GATA2 allele has been reported in a symptomatic member of a large kindred, and this allelic imbalance is related to variable penetrance.38

The GATA2 promoter/enhancer activity is very context dependent.18,54 An allelic bias in GATA2 expression was observed in cells derived from the bone marrow of patient 2, and it was cell type specific. This effect was more pronounced in more differentiated cells, suggesting that GATA2 enhancer effects vary in different cell types. However, we cannot specifically demonstrate overexpression in the patient samples. The allelic imbalance also observed in HL-60 cells did correlate with an overall increase in GATA2 expression, although we cannot identify an allele-specific cDNA marker in HL-60 cells. A similar phenomenon has been described for a point mutation in the enhancer element in intron 5.13,43,55 In this case, the mutation disrupted an ETS-binding motif (E26 transformation-specific), which led to a decrease in GATA2 expression. However, similar to this study, the greatest change was seen in granulocytes, with a modest change in CD3– PBMC cells. The allelic imbalance could be part of the mechanism driving the cell-type specific pathology. Attempts to measure total GATA2 in the patient samples were inconclusive because of the lack of sample material and the significant variation in GATA2 levels found in normal control PBL samples.

Enhancers and human disease

Enhancer elements are cis-acting DNA sequences that bind clusters of transcription factors to increase the expression of ≥1 genes. Enhancers generally function over these long distances through modified chromatin structure and chromatin loops. The importance of enhancer loops in GATA2 expression may be reflected in the predominance of cohesin and chromatin-modifying somatic gene mutations in GATA2 deficiency disease progression.21 Moreover, single nucleotide and small indel variants in enhancer elements have recently been associated with several types of diseases, including Alzheimer disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, and cancers, including hematologic malignancies.30,56-61

In summary, we investigated a large multigenerational family in which at least 4 individuals displayed the clinical features of GATA2 deficiency but lacked any mutation in GATA2. Through the application of genomic sequencing techniques, we identified a single nucleotide A-to-T variant in the −110 enhancer that created a novel composite element enhancer motif.28 This mutation cosegregated with the expected inheritance pattern of disease in this family over several generations and resulted in cell-type specific allelic imbalance in GATA2 expression in bone marrow cells. Moreover, this variant resulted in higher GATA2 expression in CRISPR/Cas9-modified cultured cells and in vitro luciferase assays. The GATA2 regulatory network is exquisitely controlled, and overexpression, as well as loss-of-function, appear to disrupt this axis and lead to the acquisition of a disease phenotype. This study demonstrates that mutations in the regulatory elements distant from the canonical gene can cause disease, and this may represent an alternative pathway for MonoMAC syndrome.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Center for Cancer Research (CCR) Genomics Core for their assistance in direct and array DNA sequencing.

This project has been funded in whole (or in part) with federal funds from the NCI, National Institutes of Health (NIH), under contract number HHSN261200800001E, project number ZIABC010870. This research was supported in part by the intramural research program of the NIH, NCI, CCR and in part by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government.

Authorship

Contribution: R.R.W. designed the research, carried out experimentation and data analysis, and drafted the manuscript; T.R.B. Jr carried out experiments and data analysis, wrote PERL scripts, and provided critical revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual content; L.M.T. carried out experimentation; L.J.E. carried out experimentation and data analysis; K.R.C. carried out experimentation, provided critical revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and reviewed the histopathology; D.T. carried out data analysis and provided critical revisions of the manuscript; J.D. worked with patient consents and family histories and provided critical revisions of the manuscript; S.M.H. provided critical revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual content; and D.D.H. supervised the study and drafted the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Dennis D. Hickstein, Immune Deficiency–Cellular Therapy Program, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, 9000 Rockville Pike, Bldg 10/CRC, Room 3-3142, Bethesda, MD 20892; e-mail: hicksted@mail.nih.gov.

References

Author notes

All Whole Genome Sequencing data from this study are deposited in the dbGaP database (www.ncbi.nih.gov/gab) with the accession number phs003269.v1.p1.

RNA-Seq data are deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information, Gene Expression Omnibus (accession number GSE227436).

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Dennis D. Hickstein (hicksted@mail.nih.gov), for other forms of data sharing (westrob@mail.nih.gov).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![Bone marrow aspirate smears from patients 1 and 2. (A) Patient 1 sample with markedly hypocellular marrow biopsy with trilineage hypoplasia (original magnification ×100 with hematoxylin and eosin [H&E] staining). (B) Patient 1 paucicellular smear with erythroid cells and a dysplastic multinucleated cell shown on inset (original magnification ×1000 with Wright-Giemsa stain). (C) Patient 2 sample with hypocellular bone marrow biopsy (original magnification ×100 with H&E staining). (D) Patient 2 with dysplastic megakaryocytes with separated nuclear lobes noted on aspirate smear (1000× with Wright-Giemsa stain). (E) Flow cytometry analysis of bone marrow samples. Scatter plots are shown for monocytes (CD14 and CD64), dendritic cells (CD123 and HLA DR), and lymphocytes (CD10 and CD20). The indicated population is marked with the square and percentage given above. Samples are shown for a normal control, a typical patient with GATA2 deficiency (R396Q), and the 2 patients in this study.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/7/20/10.1182_bloodadvances.2023010458/2/m_blooda_adv-2023-010458-gr1.jpeg?Expires=1767714919&Signature=xcYMu0REtB-iCYygPPTgYedxidtcjUHVP8j5UC1zHVcajWzjnNKjzluwubEzKX28NZ4RRw2n5u1AOkpFrkQYylAzsyTy9RUxZecjpT6XXHoMEt638R5XQSS8p4VQ~2KEU~WIgRzIcS-~xA~Nm1~wfyRfw-YLZ-faH~BK0RNe9KKOccsV3xHGKA-GyJ00KyU6118D~7h5JQPYFGLTzE-3srM6hdopLsuWStNbMSSChPqYcUn7QNDacvQv4b4phWgcHs4CaFOes3OHu6k7V47cMBZopJVkLveNan8zd87v0hY8KmFf9y1YKwQwVchAOkg3RdwXHToZANoF3wJJTPGuMw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)