Key Points

Use of azacitidine-venetoclax for AML patients who are ineligible for intensive chemotherapy is not cost-effective under current pricing.

The monthly cost of venetoclax would need to decrease by 60% for azacitidine-venetoclax to be cost-effective.

Abstract

The phase 3 VIALE-A trial reported that venetoclax in combination with azacitidine significantly improved response rates and overall survival compared with azacitidine alone in older, unfit patients with previously untreated acute myeloid leukemia (AML). However, the cost-effectiveness of azacitidine-venetoclax in this clinical setting is unknown. In this study, we constructed a partitioned survival model to compare the cost and effectiveness of azacitidine-venetoclax with azacitidine alone in previously untreated AML. Event-free and overall survival curves for each treatment strategy were derived from the VIALE-A trial using parametric survival modeling. We calculated the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of azacitidine-venetoclax from a US-payer perspective. Azacitidine-venetoclax was associated with an improvement of 0.61 quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) compared with azacitidine alone. However, the combination led to significantly higher lifetime health care costs (incremental cost, $159 595), resulting in an ICER of $260 343 per QALY gained. The price of venetoclax would need to decrease by 60% for azacitidine-venetoclax to be cost-effective at a willingness-to-pay threshold of $150 000 per QALY. These data suggest that use of azacitidine-venetoclax for previously untreated AML patients who are ineligible for intensive chemotherapy is unlikely to be cost-effective under current pricing. Significant price reduction of venetoclax would be required to reduce the ICER to a more widely acceptable value.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is the second-most common leukemia in the United States but is the most common cause of leukemia-related death in adults.1 Standard treatment of most fit patients with AML consists of high-intensity induction chemotherapy followed by consolidation and/or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. However, many AML patients are ineligible for intensive chemotherapy because of age or comorbidities. These individuals are generally offered lower-intensity treatment, such as hypomethylating agents (HMAs). However, HMAs have resulted in modest improvement compared with conventional care regimens, with a median overall survival (OS) of only 7 to 11 months and complete response in only 20% of older, unfit patients.2-5 Because of poor outcomes with HMAs, many unfit AML patients never receive active leukemia therapy and are managed only with supportive care measures.6,7

Venetoclax, a selective inhibitor of B-cell lymphoma 2 regulatory protein, initially demonstrated promising efficacy in phase 1b studies when combined with HMAs, such as azacitidine.8,9 Recently, a confirmatory phase 3 study (VIALE-A) randomly assigned previously untreated patients who were unfit for intensive treatment to azacitidine-venetoclax or azacitidine alone.10 This trial reported that azacitidine-venetoclax significantly improved response and transfusion independence (TI) rates and also prolonged OS compared with azacitidine, with a median OS of 14.7 and 9.6 months, respectively. Treatment in both arms was continued until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity, with a median drug exposure of ∼7.0 and ∼4.5 months in the azacitidine-venetoclax and azacitidine groups, respectively.10 On the basis of these clinical trials, current guidelines recommend the use of this combination as standard of care for frontline therapy in older, unfit patients.11

Although azacitidine-venetoclax significantly prolongs OS compared with azacitidine alone, it is unclear whether this regimen represents a cost-effective treatment strategy. Priced at >$12 000 per month, the acquisition costs of venetoclax can be considerable for both patients and payers.12,13 Furthermore, despite an increase in median OS of ∼5 months, azacitidine-venetoclax did not significantly improve quality-of-life measures compared with azacitidine in VIALE-A.10 Lastly, the cost of azacitidine has decreased substantially since generic entry, with a price reduction >70% over the last 5 years in the United States.14 Therefore, we hypothesized that under current pricing, combination therapy with azacitidine-venetoclax in previously untreated patients with AML who are ineligible for intensive chemotherapy would not be a cost-effective strategy when compared with azacitidine alone.

Methods

Patients and intervention

We developed a cost-effectiveness model to compare the use of azacitidine-venetoclax vs azacitidine in older, unfit patients with previously untreated AML. Our modeled patient cohort mirrored the population studied in the phase 3 VIALE-A trial.10 The median age of the population was 76 years, 60% were male, 37% had poor cytogenetic risk status, and all patients were ineligible for standard induction therapy because of age (≥75 years) or comorbidities. Approximately 55% of patients had Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 to 1 and 45% had performance status of 2 to 3, 49% of patients had a bone marrow blast count exceeding 50%, and 51% and 23% of patients had baseline red blood cell (RBC) and platelet (PLT) transfusion dependence, respectively.10 Of note, 25% and 14% of patients in the azacitidine-venetoclax arm had IDH1/2 or FLT3 mutations, respectively, compared with 22% and 20% of those in the azacitidine arm.10

Model construction

Our study was based on a partitioned survival analysis (PartSA). Patients entered our model with previously untreated AML and received either azacitidine-venetoclax or azacitidine alone. The dosing and administration schedule of each regimen was based on the VIALE-A trial.10 Patients who experienced progression on azacitidine-venetoclax or azacitidine entered a postprogression health state before death. In the postprogression health state, we assumed that all patients with actionable mutations received second-line treatment, including gilteritinib for those with FLT3 mutations15 and ivosidenib or enasidenib for those with IDH1 or IDH2 mutations,16,17 respectively. The percentage of patients with these mutations in each treatment arm was based on VIALE-A.10 Patients without actionable mutations were assumed to have received best supportive care.

The cost and utility, as measured in quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), of each treatment strategy were calculated over a lifetime horizon. These outputs were used to generate an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for azacitidine-venetoclax, which reflects the cost in 2020 US dollars for each additional QALY gained compared with azacitidine. This ICER was compared with a willingness-to-pay threshold of $150 000 per QALY gained.18 Our PartSA model used a US payer perspective, with both cost and utility discounted at a rate of 3% annually.19 The model was constructed using TreeAge Pro (TreeAge Software, Williamstown, MA), and additional statistical analyses were performed using R (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria) and STATA (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Efficacy inputs

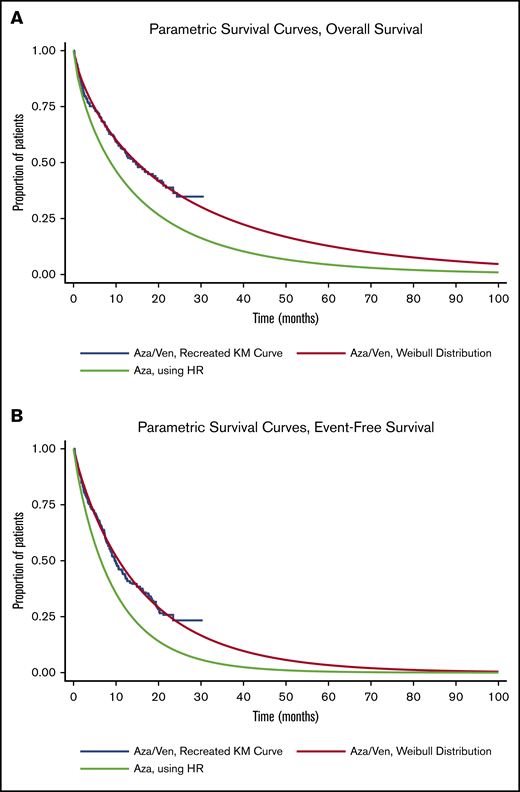

Event-free survival (EFS) and OS curves for azacitidine-venetoclax were derived from VIALE-A using published extrapolation techniques.20,21 Briefly, individual patient–level data were recreated from Kaplan-Meier curves and at-risk tables for OS and EFS for azacitidine-venetoclax. The recreated individual patient–level data were then fit to 6 parametric survival distributions (exponential, Gompertz, Weibull, log-logistic, log-normal, and generalized γ), and the curve that exhibited the best fit per Akaike information criterion and visual inspection was selected for use in the model. Weibull distributions were ultimately chosen for EFS and OS of azacitidine-venetoclax. We then used the hazard ratios reported in VIALE-A to derive EFS and OS for azacitidine alone10 (Figure 1).

Parametric survival curves used in PartSA. Parametric survival curves used to estimate OS (A) and EFS (B). Aza, azacitidine; HR, hazard ratio; KM, Kaplan-Meier; Ven, venetoclax.

Parametric survival curves used in PartSA. Parametric survival curves used to estimate OS (A) and EFS (B). Aza, azacitidine; HR, hazard ratio; KM, Kaplan-Meier; Ven, venetoclax.

Key clinical parameters

Key clinical parameters used in the PartSA model are listed in Table 1. First, we incorporated discontinuation of first-line treatment because of AEs into the model, with rates estimated from VIALE-A.10 In our base-case analysis, we assumed that 50% of all AE-related discontinuation events occurred within the first 2 months of treatment; however, this percentage was varied during sensitivity analyses. Second, our base-case model included treatment interruption for count recovery at the end of cycle 1 for 72% of patients in the azacitidine-venetoclax arm and 57% in the azacitidine arm.10 On the basis of a recent retrospective analysis,22 the duration of dose interruption was 2 weeks, and a subset of patients in the azacitidine-venetoclax arm received 5 doses of filgrastim for count recovery between cycles 1 and 2. Third, our model assumed 20% of patients in the venetoclax arm would require hospitalization during dose ramp-up; this percentage was varied from 0% to 100% during sensitivity analyses. Lastly, our base-case model had 64% and 43% of patients in the azacitidine-venetoclax and azacitidine arms, respectively, achieving postbaseline TI for RBCs or PLTs.22 These values were estimated by averaging the percentage of patients who achieved RBC and PLT TI in each arm of VIALE-A.10 The duration of TI was estimated to be 4 months, informed by a recent population-based study.5

Model clinical parameters

| Result or transition . | Estimate . | Range . | Study or data source . |

|---|---|---|---|

| OS for azacitidine-venetoclax | Weibull: λ = 0.0843388, κ = 0.7800001 | — | 10 |

| EFS for azacitidine-venetoclax | Weibull: λ = 0.079045, κ = 0.9180112 | — | 10 |

| Hazard ratio for OS (azacitidine as reference) | 0.66 | 0.52-0.85 | 10 |

| Hazard ratio for EFS (azacitidine as reference) | 0.63 | 0.49-0.82 | 10 |

| Probability of treatment discontinuation because of AE, % | |||

| Azacitidine-venetoclax | 24 | 12-36 | 10 |

| Azacitidine | 20 | 10-30 | 10 |

| Discontinuation events because of AE occurring within first 2 mo of treatment, % | 50 | 25-75 | Expert opinion |

| Patients receiving growth factor, % | |||

| Azacitidine-venetoclax | 32 | 16-48 | 10 |

| Azacitidine | 0 | 0-16 | Expert opinion |

| No. of doses of growth factor | 5 | 0-10 | Expert opinion |

| Patients experiencing dose interruption after first cycle of treatment, % | |||

| Azacitidine-venetoclax | 72 | 36-100 | 10 |

| Azacitidine | 57 | 29-86 | 10 |

| Median duration of dose interruption, wk | 2 | 0-4 | 22 |

| Patients hospitalized during venetoclax dose ramp-up, % | 20 | 0-100 | Expert opinion |

| Patients achieving TI, % | |||

| Azacitidine-venetoclax | 64 | 32-96 | 10 |

| Azacitidine | 43 | 21-64 | 10 |

| Discount rate, % | 3 | 1.5-6.0 | 19 |

| Result or transition . | Estimate . | Range . | Study or data source . |

|---|---|---|---|

| OS for azacitidine-venetoclax | Weibull: λ = 0.0843388, κ = 0.7800001 | — | 10 |

| EFS for azacitidine-venetoclax | Weibull: λ = 0.079045, κ = 0.9180112 | — | 10 |

| Hazard ratio for OS (azacitidine as reference) | 0.66 | 0.52-0.85 | 10 |

| Hazard ratio for EFS (azacitidine as reference) | 0.63 | 0.49-0.82 | 10 |

| Probability of treatment discontinuation because of AE, % | |||

| Azacitidine-venetoclax | 24 | 12-36 | 10 |

| Azacitidine | 20 | 10-30 | 10 |

| Discontinuation events because of AE occurring within first 2 mo of treatment, % | 50 | 25-75 | Expert opinion |

| Patients receiving growth factor, % | |||

| Azacitidine-venetoclax | 32 | 16-48 | 10 |

| Azacitidine | 0 | 0-16 | Expert opinion |

| No. of doses of growth factor | 5 | 0-10 | Expert opinion |

| Patients experiencing dose interruption after first cycle of treatment, % | |||

| Azacitidine-venetoclax | 72 | 36-100 | 10 |

| Azacitidine | 57 | 29-86 | 10 |

| Median duration of dose interruption, wk | 2 | 0-4 | 22 |

| Patients hospitalized during venetoclax dose ramp-up, % | 20 | 0-100 | Expert opinion |

| Patients achieving TI, % | |||

| Azacitidine-venetoclax | 64 | 32-96 | 10 |

| Azacitidine | 43 | 21-64 | 10 |

| Discount rate, % | 3 | 1.5-6.0 | 19 |

AE, adverse event.

Costs

Costs incorporated into the PartSA model are listed in Table 2. The costs of subcutaneous medications, such as azacitidine and filgrastim, were derived from the Medicare October 2020 average sales price files.14 These costs represented 106% of the average sales prices. We assumed an average total body surface area of 1.7 m2 and an average bodyweight of 70 kg and adjusted for drug wastage by rounding up to the nearest single-use vial size for each dose administered.23 Outpatient administration costs for chemotherapy were derived from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2020 Physician Fee Schedule.24

Model costs

| Cost . | Baseline, US$ . | Range, US$ . | Study or data source . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Venetoclax 400 mg daily, per mo | 11 741.61 | — | 25 |

| Gilteritinib 120 mg daily, per mo | 23 044.80 | — | 25 |

| Ivosidenib 500 mg daily, per mo | 26 831.07 | — | 25 |

| Enasidenib 100 mg daily, per mo | 26 440.94 | — | 25 |

| Voriconazole 200 mg twice daily, per mo | 498.61 | — | 25 |

| Azacitidine 75 mg/m2, per dose | 160.20 | — | J9025 |

| Filgrastim (Granix) 5 μg/kg, per dose | 225.60 | — | J1447 |

| Chemotherapy subcutaneous injection | 80.12 | 69.07-105.81 | CPT 96401 |

| Outpatient visits, per mo | 682.57 | 341.29-1023.86 | 26 |

| Transfusion support, per mo | 3882.14 | 1941.07-5823.20 | 26 |

| Best supportive care, per mo | 5094.56 | 2547.28-7641.84 | 27 |

| Hospitalization for venetoclax ramp-up | 8246.81 | — | DRG 836 |

| End-of-life care | 188 677.66 | 94 338.83-283 016.50 | 28 |

| Cost . | Baseline, US$ . | Range, US$ . | Study or data source . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Venetoclax 400 mg daily, per mo | 11 741.61 | — | 25 |

| Gilteritinib 120 mg daily, per mo | 23 044.80 | — | 25 |

| Ivosidenib 500 mg daily, per mo | 26 831.07 | — | 25 |

| Enasidenib 100 mg daily, per mo | 26 440.94 | — | 25 |

| Voriconazole 200 mg twice daily, per mo | 498.61 | — | 25 |

| Azacitidine 75 mg/m2, per dose | 160.20 | — | J9025 |

| Filgrastim (Granix) 5 μg/kg, per dose | 225.60 | — | J1447 |

| Chemotherapy subcutaneous injection | 80.12 | 69.07-105.81 | CPT 96401 |

| Outpatient visits, per mo | 682.57 | 341.29-1023.86 | 26 |

| Transfusion support, per mo | 3882.14 | 1941.07-5823.20 | 26 |

| Best supportive care, per mo | 5094.56 | 2547.28-7641.84 | 27 |

| Hospitalization for venetoclax ramp-up | 8246.81 | — | DRG 836 |

| End-of-life care | 188 677.66 | 94 338.83-283 016.50 | 28 |

The costs of oral medications, such as venetoclax, gilteritinib, ivosidenib, and enasidenib, were derived from the Medicare plan finder tool13 using methodology from the Memorial Sloan Kettering DrugPricing Laboratory.25 The costs of these medications were adjusted by the Medicare Part D standard benefit parameters to include only plan and payer contributions.

The costs of outpatient physician follow-up,26 transfusion support,26 best supportive care,27 and end-of-life care28 were derived from published literature. Lastly, the cost of hospitalization during venetoclax dose ramp-up and the cost of severe (grade 3+) AEs were based on inpatient Medicare diagnosis-related group–based payments29 (supplemental Table 1). All costs were inflated to 2020 US dollars using the personal consumption expenditure–health index.30

Utilities

Utility values for EFS and postprogression were based on previously published quality-of-life data from the Cancer and Leukemia Group B 9221 trial, evaluating the use of azacitidine in myelodysplastic syndrome.31,32 Patients who were event free were assigned a utility of 0.67 for the first 6 months of treatment, after which the utility increased to 0.80 (Table 3). Because VIALE-A reported no differences in quality-of-life measures between the 2 treatment arms, our base-case model had identical utility values for patients who were receiving azacitidine-venetoclax and azacitidine.10

Model utilities

| Utility . | QALY . | Range . | Study or data source . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Progression-free survival, mo 1-6 | 0.67 | 0.60-0.74 | 31,32 |

| Progression-free survival, mo 7+ | 0.80 | 0.72-0.88 | 31,32 |

| Progressive disease | 0.67 | 0.60-0.74 | 31,32 |

Sensitivity analyses

We incorporated sensitivity analyses to assess uncertainty in our model. During 1-way sensitivity analyses, individual model parameters were varied across the ranges outlined in Tables 1,2-3 to determine their impact on the ICER. Hazard ratios were varied across their 95% confidence intervals, utility values were varied within a 10% range, and most costs and transition probabilities were varied within a 50% range. During probabilistic sensitivity analysis, each parameter was described using a distribution, and we performed 10 000 Monte Carlo simulations, each time randomly sampling from the distribution of model inputs. Costs were described by γ distributions and probabilities and utilities by β distributions.

We also incorporated 2 scenario analyses. In the first, we assumed that patients received antifungal prophylaxis with voriconazole during the first 3 cycles of treatment, a period when patients are at the greatest risk of severe neutropenia. Voriconazole is a strong cytochrome P450 inhibitor, and prior studies have reported that concomitant use of voriconazole and venetoclax requires a 75% venetoclax dose reduction.8,33,34 As a result, we modeled patients to be on 100 mg of venetoclax daily rather than 400 mg for the first 3 cycles of treatment.

In the second scenario analysis, we included a highly conservative set of assumptions that strongly favored azacitidine-venetoclax. First, we assumed that the dose of venetoclax was reduced during the first 3 cycles of treatment, as described in our first scenario analysis. Second, we assumed that patients in the azacitidine-venetoclax arm experienced an earlier increase in utility (ie, after 3 months of treatment rather than 6) to reflect the shorter median time to first response reported in VIALE-A. Lastly, we assumed that no patients in the azacitidine-venetoclax arm required hospitalization during dose ramp-up. This scenario reflected a best-case scenario for the cost-effectiveness of azacitidine-venetoclax.

Results

Base-case analysis

In our base-case analysis, use of azacitidine-venetoclax was associated with an improvement of 0.61 QALYs compared with use of azacitidine alone (1.53 vs 0.91 QALYs, respectively). However, azacitidine-venetoclax was also associated with significantly greater lifetime health care costs than azacitidine ($491 093 vs $331 498, respectively), with an incremental cost of $159 595. Therefore, the ICER for azacitidine-venetoclax was $260 343 per QALY, which is above the willingness-to-pay threshold of $150 000 per QALY (Table 4).

Base-case cost-effectiveness analysis

| Strategy . | Base-case model . | PSA model . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost, US$ . | Incremental cost, US$ . | Effectiveness, QALY . | Incremental effectiveness, QALY . | ICER, US$/QALY . | ICER 95% CI, $/QALY . | |

| Azacitidine-venetoclax | 491 093 | 159 595 | 1.53 | 0.61 | 260 343 | 187 731-532 313 |

| Azacitidine | 331 498 | — | 0.91 | — | — | — |

| Strategy . | Base-case model . | PSA model . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost, US$ . | Incremental cost, US$ . | Effectiveness, QALY . | Incremental effectiveness, QALY . | ICER, US$/QALY . | ICER 95% CI, $/QALY . | |

| Azacitidine-venetoclax | 491 093 | 159 595 | 1.53 | 0.61 | 260 343 | 187 731-532 313 |

| Azacitidine | 331 498 | — | 0.91 | — | — | — |

CI, confidence interval; PSA, probabilistic sensitivity analysis.

Sensitivity analyses

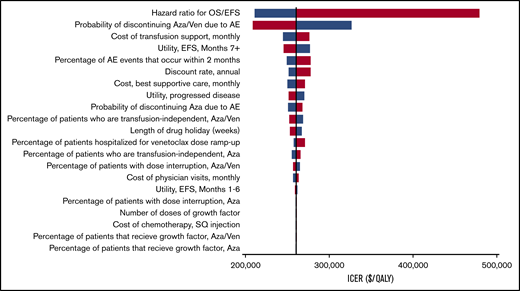

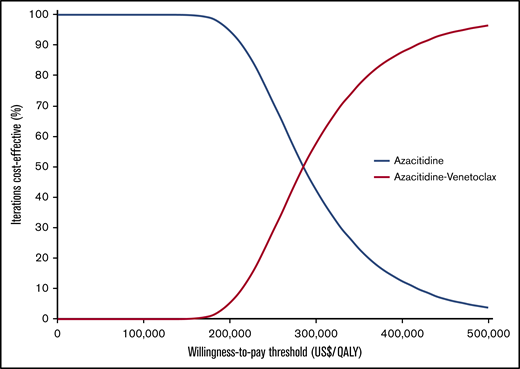

Our model was most sensitive to the hazard ratios for EFS and OS of azacitidine-venetoclax relative to azacitidine (Figure 2). Simultaneously decreasing the hazard ratios of OS and EFS to 0.52 and 0.49, respectively, decreased the ICER to $210 971 per QALY, whereas increasing the hazard ratios to 0.85 and 0.82 increased the ICER to $480 020 per QALY. Other parameters that had a significant impact on the ICER included the probability of azacitidine-venetoclax discontinuation because of AEs, the monthly cost of transfusion support, and the utility of EFS after 6 months. Notably, all ICERs remained above the willingness-to-pay threshold of $150 000 per QALY during 1-way sensitivity analysis. Threshold analysis showed that the price of venetoclax would need to decrease by 60%, from $11 742 to $4659 per month, for azacitidine-venetoclax to be cost-effective compared with azacitidine alone. During probabilistic sensitivity analysis, >99% of iterations produced ICERs greater than the willingness-to-pay threshold of $150 000 per QALY (Figure 3).

One-way sensitivity analyses. All model parameters with ranges in Tables 1-3 were varied during 1-way sensitivity analyses. Blue represents the lower value in the range, whereas red represents the higher value. Aza, azacitidine; SQ, subcutaneous; Ven, venetoclax.

Probabilistic sensitivity analyses. Results of the probabilistic sensitivity analyses were based on 10 000 Monte Carlo simulations.

Probabilistic sensitivity analyses. Results of the probabilistic sensitivity analyses were based on 10 000 Monte Carlo simulations.

In the first scenario analysis, we allowed for venetoclax dose reduction in the first 3 cycles of therapy as a result of concomitant use of voriconazole. Here, azacitidine-venetoclax was associated with an incremental cost of $133 501 ($465 000 vs $331 498), an incremental effectiveness of 0.61 QALYs, and an ICER of $217 778 per QALY compared with azacitidine. In the second scenario analysis, we included venetoclax dose reduction as well as additional conservative assumptions, such as an earlier increase in quality of life with azacitidine-venetoclax and no requirement for hospitalization during venetoclax initiation. Even with these assumptions, azacitidine-venetoclax was not found to be cost-effective, with an incremental cost of $131 852 ($463 350 vs $331 498), an incremental effectiveness of 0.64 QALYs (1.55 vs 0.91 QALYs), and an ICER of $207 140 per QALY.

Discussion

The VIALE-A trial demonstrated that azacitidine-venetoclax confers a statistically significant and clinically meaningful survival benefit in previously untreated AML patients who are ineligible for intensive chemotherapy when compared with azacitidine alone.10 Venetoclax has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for this indication,35 and numerous trials are testing additional venetoclax combinations in AML, including the use of azacitidine-venetoclax as a backbone for triplet combinations.36 In this study, we assessed the value of azacitidine-venetoclax compared with azacitidine in older, unfit patients using a partitioned survival model. Our model showed that azacitidine-venetoclax is unlikely to be cost-effective under current pricing, with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of $260 343 per QALY. Furthermore, we found that a significant price reduction of venetoclax (60%+) is needed before the ICER of azacitidine-venetoclax reaches a widely acceptable value.18

Our study has important strengths. First, our cost-effectiveness analysis was based on a phase 3 randomized study that directly compared azacitidine-venetoclax and azacitidine in previously untreated AML.10 Because our PartSA model derived efficacy inputs for azacitidine-venetoclax using recreated individual patient data from this trial, the estimated EFS and OS of patients in our model closely align with the original results reported in VIALE-A.10 Second, our model incorporated a number of key clinical parameters that could influence the overall cost of treatment with azacitidine-venetoclax, including hospitalization during venetoclax dose ramp-up, achievement of TI, dose delay because of cytopenias, growth factor support, and treatment discontinuation and hospitalization because of AEs. Third, we were conservative when creating our model and included a scenario analysis where our inputs strongly favored azacitidine-venetoclax. Even when assuming a period of lower venetoclax dosing, no required hospitalization for venetoclax dose ramp-up, and an earlier increase in quality-of-life metrics, azacitidine-venetoclax was not found to be cost-effective under current pricing.

An opportunity for increased economic value of venetoclax is the possibility of sustained dose reduction. A number of studies have reported that concurrent use of venetoclax and CYP450 inhibitors, such as voriconazole or posaconazole, requires venetoclax doses as low as 50 mg to be used rather than the standard 400-mg dose.8,33,34 In some clinical practices, antifungal prophylaxis is used during the first few cycles of treatment, particularly during periods of severe neutropenia. We evaluated this in our first scenario analysis, where venetoclax dose reduction from 400 to 100 mg daily, which decreased the monthly cost of venetoclax from ∼$12 000 to ∼$3000, reduced the ICER of azacitidine-venetoclax from $260 343 to $217 778 per QALY. Given that venetoclax is currently priced per milligram, it is feasible that more prolonged use of CYP450 inhibitors (eg, during the entire duration of venetoclax therapy) could further improve the cost-effectiveness of azacitidine-venetoclax. However, it is important to note that the pricing of high-cost cancer therapies can be changed from per milligram to per tablet, potentially limiting the impact of considering CYP450 and venetoclax dose reduction as a means to improve long-term cost-effectiveness.

This economic evaluation comes on the heels of several others that have demonstrated persistently high ICERs for recently approved cancer treatments.37-42 Although some high-cost therapies, such as the use of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in select B-cell malignancies,43,44 have been shown to be cost-effective, other high-cost treatments that only marginally improve clinical outcomes and/or require continuous administration are generally of poor economic value.41 Given the excitement surrounding the use of venetoclax in older, unfit patients with AML,45,46 it is possible additional venetoclax combinations will be approved for AML treatment in the near future. Critical appraisal of the value of these regimens will be important to achieve more cost-effective AML care and curb the alarmingly high costs of cancer treatment.47,48

Although our model has notable strengths, there are limitations to consider. First, cost-effectiveness models are subject to inherent limitations based on the availability of data used to populate the model. For instance, although our efficacy inputs were based on a phase 3 randomized trial, there is uncertainty regarding long-term clinical outcomes for patients beyond the trial period. We attempted to limit such uncertainty by using parametric survival curves that reflected our current clinical understanding of survival outcomes in newly diagnosed patients who are ineligible for intensive induction chemotherapy. Second, our ability to accurately model the costs of the postprogression health state was limited, because data regarding receipt of second-line treatment was not reported in the VIALE-A study. In our base-case analysis, we conservatively assumed that only patients with actionable mutations received second-line treatment. Third, we did not account for variations in provider practice with regard to reducing the length of venetoclax administration (ie, to 21 or 14 days) after first response.49

Fourth, although our utility values were specific to AML health states, we were unable to use direct patient-reported outcomes from the VIALE-A trial, because these EQ-5D scores were not included in the original report.10 Nonetheless, we prescribed identical utility values for both azacitidine-venetoclax and azacitidine in our base-case analysis, because published results from VIALE-A did indicate that there was no quality-of-life benefit with the addition of venetoclax. Fifth, our model only considered direct health care expenditures and did not include indirect or nonmedical costs, such as lost productivity, transportation, or the financial impact of caregivers. Sixth, it is important to note that our model estimated the ICER for the heterogenous AML population enrolled in VIALE-A. It is possible that individual factors, such as cytogenetic risk status, may have affected the cost-effectiveness of azacitidine-venetoclax for each patient. Lastly, our analysis is only applicable to the setting of AML patients unfit for intensive chemotherapy. Clinical trials and future economic analyses will be needed to better define the role of azacitidine-venetoclax in patients who could tolerate standard cytotoxic therapy.

On the basis of the results of VIALE-A and earlier phase 1/2 trials,8,9 azacitidine-venetoclax has quickly surged to become standard of care for the treatment of older, unfit patients with newly diagnosed AML.11 Despite the improvement in OS compared with azacitidine alone reported in VIALE-A, our model shows that azacitidine-venetoclax is unlikely to be a cost-effective treatment strategy under current pricing. For azacitidine-venetoclax to become cost-effective in this clinical setting, a significant venetoclax price reduction would be required.

Requests for original data should be e-mailed to scott.huntington@yale.edu.

Acknowledgments

The Frederick A. DeLuca Foundation supported this work. K.K.P. is funded by the American Society of Hematology Physician-Scientist Career Development Award. A.M.Z. is a Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Scholar in Clinical Research and was also supported by a National Cancer Institute (NCI) Cancer Clinical Investigator Team Leadership Award. Research reported in this publication was in part supported by the NCI, National Institutes of Health (under award P30 CA016359).

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Authorship

Contribution: K.K.P., A.M.Z., and S.F.H. had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis; K.K.P., A.M.Z., and S.F.H. were responsible for conception and design; acquired, analyzed, and interpreted the data; and drafted the manuscript; all authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content; K.K.P. performed statistical analysis; K.K.P., S.F.H., and A.M.Z. obtained funding; and A.M.Z. and S.F.H. supervised the study.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.M.Z. has received research funding (institutional) from Celgene/Bristol-Myers Squibb, AbbVie, Astex, Pfizer, Medimmune/AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Trovagene/Cardiff Oncology, Incyte, Takeda, Novartis, Aprea, and ADC Therapeutics; participated in advisory boards and/or had a consultancy with and received honoraria from AbbVie, Otsuka, Pfizer, Celgene/Bristol-Myers Squibb, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Incyte, Agios, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Novartis, Acceleron, Astellas, Daiichi Sankyo, Cardinal Health, Taiho, Seattle Genetics, BeyondSpring, Trovagene/Cardiff Oncology, Takeda, Ionis, Amgen, Janssen, Epizyme, Syndax, and Tyme; served on clinical trial committees for Novartis, AbbVie, Geron, and Celgene/Bristol-Myers Squibb; and received travel support for meetings from Pfizer, Novartis, and Trovagene/Cardiff Oncology. S.F.H. has been a consultant for Celgene, Bayer, Genentech, Pharmacyclics, AbbVie and received research funding from DTRM Biopharm, Celgene, and TG Therapeutics. N.P. has participated in advisory boards and/or had a consultancy with and received honoraria from Alexion, Pfizer, Agios Pharmaceuticals, Blueprint Medicines, Incyte, Novartis, Celgene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CTI BioPharma, and PharmaEssentia and received research funding (institutional) from Boehringer-Ingelheim, Astellas Pharma, Daiichi Sankyo, Sunesis Pharmaceuticals, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Astex Pharmaceuticals, CTI Biopharma, Celgene, Genentech, AI Therapeutics, Samus Therapeutics, Arog Pharmaceuticals, and Kartos Therapeutics. T.P. has received research support from Agios, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Jazz Pharmaceuticals. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Scott F. Huntington, Department of Hematology/Oncology, Yale University School of Medicine, 333 Cedar St, New Haven, CT 06520; e-mail: scott.huntington@yale.edu.

References

Author notes

K.K.P. and A.M.Z. contributed equally to this work as first authors.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.