Key Points

Hapln1b encodes a structural protein that is absolutely necessary for hematopoietic stem cell emergence.

The ECM is necessary for vasculature development, but also for kit signaling in the major vessels, to promote definitive hematopoiesis.

Abstract

During early vertebrate development, hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) are produced in hemogenic endothelium located in the dorsal aorta, before they migrate to a transient niche where they expand to the fetal liver and the caudal hematopoietic tissue, in mammals and zebrafish, respectively. In zebrafish, previous studies have shown that the extracellular matrix (ECM) around the aorta must be degraded to enable HSPCs to leave the aortic floor and reach blood circulation. However, the role of the ECM components in HSPC specification has never been addressed. In this study, hapln1b, a key component of the ECM, was specifically expressed in hematopoietic sites in the zebrafish embryo. Gain- and loss-of-function experiments all resulted in the absence of HSPCs in the early embryo, showing that hapln1b is necessary, at the correct level, to specify HSPCs in the hemogenic endothelium. Furthermore, the expression of hapln1b was necessary to maintain the integrity of the ECM through its link domain. By combining functional analyses and computer modeling, we showed that kitlgb interacts with the ECM to specify HSPCs. The findings show that the ECM is an integral component of the microenvironment and mediates the cytokine signaling that is necessary for HSPC specification.

Introduction

The emergence of blood cells is a highly conserved process that consists of many different waves in distinct anatomical locations. The first cells that emerge in zebrafish and mammals consist of primitive myeloid and erythroid cells,1-4 Definitive hematopoiesis is then initiated by the emergence of the transient erythromyeloid precursors (EMPs), which arise in the yolk sac in mice and humans1,2 and in the posterior blood island in zebrafish embryos.5 Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) are then specified in the aorta-gonads-mesonephros (AGM) region, where they form small intra-aortic clusters.6-11 HSPCs are derived directly from the aortic hemogenic endothelium (HE), and specification is controlled by the correct balance of several extrinsic factors, such as VEGF, hedgehog, notch, BMP, and transforming growth factor β signaling.12-16 Early HSPC specification from the HE in zebrafish is marked by the expression of gata2b17 followed by runx1.12 Budding of zebrafish HSPCs occurs between 32 and 60 hours post fertilization (hpf), from the HE in the dorsal aorta.18,19 This process is dependent on inflammatory cytokines produced by neutrophils and macrophages.20-22 Macrophage- and vascular-mediated extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation is also necessary to enable HSPCs to migrate into the veins.23,24 They then migrate to the caudal hematopoietic tissue (CHT), where they interact with endothelial cells and expand significantly in number.25,26

The exact mechanisms controlling HSPC emergence from the HE and their expansion in the CHT remain to be fully characterized. We and others have previously shown that these 2 processes are highly dependent on cytokine signaling. In particular, in zebrafish, we showed the important and nonredundant roles of oncostatin M and kit-ligand b (kitlgb) in this process.25,27 Proteoglycans, major components of the ECM, interact with several hematopoietic cytokines (granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, interleukin-3, and Kitlg) and maintain the proximity of stromal cells, HSPCs and cytokines in the niche.28-30 We studied the role of hapln1b, an ECM-associated protein, in this process. We focused on hapln1b, as it has been shown to be expressed in the vasculature and hematopoietic tissues.31 Furthermore, this gene is important for correct vascular development of the tail vasculature.31 In mammals, there are HAPLN1, 2, 3, and 4 genes,32 whereas in zebrafish, there are hapln1a, 1b, 2, 3, and 4.31 Hapln1 codes for a link protein, required to attach several chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans to the hyaluronic acid (HA) backbone (a ubiquitous glycosaminoglycan) to make large, negatively charged, ECM structures.33 In mammals, Hapln1 is a secreted ECM protein that stabilizes aggrecan-hyaluronan complexes and is required for correct craniofacial34 and neocortex development.35 Loss of HAPLN1 expression promotes melanoma metastasis, but is also necessary to maintain immune cell motility.36 HAPLN1 is essential for maintaining lymphatic vessel integrity and reducing endothelial cell permeability, thus preventing visceral metastasis.37 Knockout mouse studies have also revealed a role in maintaining perineural nets (PNNs), a hyaluronan backbone meshlike network of proteins that surround neurons and regulate neuronal plasticity,38 as well as neural differentiation and development.39-41 Furthermore, PNNs are responsible for binding chemorepulsive molecules, such as Semaphorin3a,42 and transcription factors, such as Otx2, that are exchanged between different neural cells to enhance cortical plasticity.43 Hapln1a was recently shown to be necessary for ECM expansion in the developing zebrafish heart, and CRISPR-Cas9 hapln1a mutants show reduced atrial size and chamber ballooning.44 Hapln1a is also necessary for maintaining HA stability, therefore stabilizing the ECM,45 and sema3d, for mediating signal transduction in skeletal growth and patterning in fin regeneration.46

In this study, hapln1b was necessary for mediating kitlgb-kitb interactions and inducing runx1 expression in the HE during HSPC specification in the zebrafish embryo. Gain and loss of function of hapln1b both resulted in defective hematopoiesis. Therefore, we conclude that this gene is essential, at the correct dosage, for the specification of HSPCs from the HE and their development after their emergence.

Materials and methods

Zebrafish strains and husbandry

AB* (WT) zebrafish, along with transgenic and mutant strains were kept in a 14-/10-hour light/dark cycle at 28°C.47 We used the following transgenic animals: lmo2:eGFPzf71,48 gata1:DsRedsd2,49 kdrl:eGFPs843,50 kdrl:Hsa.HRAS-mCherrys896,51 cmyb:GFPzf169,52 globin:eGFPcz332,53 sox10:mRFPvu234,54 mpx:GFPi113,55 and mpeg1:mcherrygl23.56 All animals were zebrafish embryos aged less than 120 hours post fertilization (hpf); therefore, there was no requirement for authorization of animal experimentation. However, our adult animals were raised according to the animal facilities guidelines of the University of Geneva.

WISH staining and analysis

Whole mount in situ hybridization (WISH) was performed on 4% paraformaldehyde-fixed embryos at the developmental time points indicated. Digoxygenin-labeled probes were synthesized with an RNA Labeling kit (SP6/T7; Roche). RNA probes were generated by linearization of TOPO-TA or ZeroBlunt vectors (Invitrogen) containing the polymerase chain reaction–amplified complementary DNA sequence. WISH was performed as previously described.57 Phenotypes were scored by comparing expression with siblings. All injections were repeated 3 independent times. Analysis was performed with R or GraphPad Prism software. Embryos were imaged in 100% glycerol with an Olympus MVX10 microscope. The oligonucleotide primers used for the production of ISH probes are listed in supplemental Table 2.

Western blot analysis

Pools of ∼30 embryos were collected. Cells were lysed in IP Lysis Buffer (IP Lysis Buffer) with protease inhibitor cocktail (Merck), and protein was extracted and then separated by gel electrophoresis and incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-HA antibody (1:1000 ab18181; abcam) followed by goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L)-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (1706516; BioRad). Staining was revealed by using Western Bright Sirius (1:1; Adventa) and an exposure of 1 minute, 15 seconds.

Cell sorting and flow cytometry

Zebrafish transgenic embryos (15-20 per biological replicate) were incubated in 0.5 mg/mL Liberase (Roche) solution and shaken for 90 minutes at 33°C, then dissociated, filtered, and resuspended in 0.9× phosphate-buffered saline and 1% fetal calf serum. Dead cells were labeled and excluded by staining with 5 nM Sytox red (Life Technologies) or 300 nM DRAQ7 (Biostatus). Cell sorting was performed on the Aria II (BD Biosciences) or the nS3 (BioRad). Data were analyzed with FlowJo and GraphPad Prism.

Quantitative real-time PCR and analysis

RNA was extracted with the Qiagen RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) and reverse transcribed into cDNA with a Superscript III kit (Invitrogen) or qScript (Quanta Biosciences). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed with the Sybr Fast Universal qPCR kit (Kapa Biosystems) and run on the CFX Connect real-time system (BioRad). All primers are listed in supplemental Table 1. Analyses were performed with Microsoft Excel or GraphPad Prism.

Synthesis of full-length mRNA and microinjection

The PCR primers used to amplify the cDNA of interest are listed in supplemental Table 2. Kitlgb and kitlga messenger RNA (mRNA) was synthesized and injected as previously described.25,27 mRNA was reverse transcribed with the mMessage mMachine kit SP6 (Ambion) from a linearized pCS2+ vector containing PCR products. After transcription, RNA was purified by phenol chloroform extraction. Hapln1b mRNA was injected at 200 pg, unless otherwise stated.

Immunofluorescence

Images were obtained with a Nikon SMZ1500 microscope or a Nikon inverted A1r spectral confocal microscope. Confocal z-stack image acquisition in multiple fluorescent channels was used to examine the entire dorsal aorta in the AGM . Immunofluorescence double staining was performed as described previously,58 with anti-p-akt S473 (1:25; cat. no. 9271; Cell Signaling) and AlexaFluor 594–conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:1000; cat. no. A11012; Life Technologies).

Imaging

WISH products were imaged on an Olympus MVX10 microscope in 100% glycerol. Fluorescent images were taken with an IX83 microscope and processed by CellSens Dimension software (Olympus). All images were processed with Adobe Photoshop. Time-lapse imaging was obtained with a Nikon inverted A1r spectral confocal microscope, processed with Fiji, and analyzed with GraphPad Prism.

Morpholinos

All morpholino oligonucleotides (MOs) were purchased from Gene Tools and are listed in supplemental Table 3. MO efficiency was tested by using PCR from total RNA extracted from a pool of 8 to 10 embryos at 24 hpf. Hapln1b full-length primers (supplemental Table 2) were used to test MO efficiency. The hapln1b morpholino was injected at 3 ng, unless otherwise stated. All MOs used were splice-blocking MOs.

Structural modeling and electrostatic properties of kitlga and kitlgb

Structural models for zebrafish kitlga and kitlgb were constructed based on a consensus approach using homology-modeling, template-based structure modeling, and ab initio structure prediction as implemented in i-TASSER, Phyre2, and RaptorX.59-61 Vacuum electrostatic potential calculations were performed and displayed with the built-in module in PyMOL v. 2.3 (https://pymol.org/2/). Isoelectric point calculations were performed via the Prot-pI server (https://www.protpi.ch).

Results

Hapln1b is specifically expressed in early embryonic hematopoietic tissues

Previous studies have shown that hapln1b is expressed in the vasculature at 24 to 28 hpf, and that its loss of function results in abnormal angiogenesis.31 However, its role during embryonic hematopoiesis has never been investigated. In zebrafish, hapln1b is the only hapln family member to display a hematopoietic expression pattern (Figure 1; supplemental Figure 1A), despite retaining high sequence identity and conserved peptides capable of forming disulphide bonds (supplemental Figure 1A-B). Synteny, phylogeny, and sequence identity analyses revealed that hapln1a and hapln1b originate from a duplication of the HAPLN1 gene in mammals (supplemental Figure 2A-B). Even across these species, peptides capable of forming disulphide bonds within the link domain have been conserved (supplemental Figure 2C). We therefore focused our study on hapln1b and first examined its expression pattern. We established that hapln1b is initially expressed at ∼12 hpf and would therefore not be derived from maternal RNA62 (supplemental Figure 4A). Hapln1b is expressed between 20 and 26 hpf along the aorta, in the developing CHT and in the hypochord, as previously described.31 Further analyses at 26 hpf revealed that hapln1b is also expressed in the aorta and vein region, ventral to the notochord (Figure 1Ai). The expression may be within the DA/PCV joint.63 Between 30 and 36 hpf the expression begins to decrease, becoming more localized to the CHT, before being completely restricted to the marginal fold at 48 hpf (Figure 1A). Expression was also scored in the cardiac precursors at 36 hpf and in possible cranial cartilaginous structures (Figure 1Aii-iii). By 4 and 5 days post fertilization (dpf) expression was restricted to the cranial structures and was absent from the hematopoietic tissue (Figure 1B).

Hapln1b is expressed by vascular cells and hematopoietic progenitors. (A) WISH of hapln1b expression from 20 to 48 hpf. (Ai) Section at 26 hpf, displaying aorta (a) and vein (v) and notochord (n). (Aii-iii) ventral view at 36 and 48 hpf. (B) WISH of hapln1b expression at 4 and 5 dpf. (Biv-v) Dorsal view at 4 and 5 dpf. (C-E) Experimental outline and qPCR expression of hapln1b from FACS-sorted endothelial cells. (F) qPCR expression of hapln1b in FACS-sorted hematopoietic progenitors (EMPs and HSPCs). All qPCR data are from biological triplicates (except for whole GFP− in panel D, where data represent biological duplicates). Data indicate expression relative to ef1a (calculated by [2Ct(hapln1b) − Ct(ef1a)] × 10 000). (D) Two-tailed Student t-test, whole GFP− and GFP+; P = .0035; heads and tails, P = .75. (E-F) Analysis was performed by 1-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons. (E) Whole GFP− and GFP+, P = .99; whole GFP− and heads, P = .44; and whole GFP− and tails, P = .99. (F) Whole and EMPs, P = .0081; whole and HSPCs, P = .0449. (G) SMART (http://smart.embl.de/) prediction of hapln1b protein structure. IG, immunoglobulinlike domain; Link, HA Link domain; aa, amino acid.

Hapln1b is expressed by vascular cells and hematopoietic progenitors. (A) WISH of hapln1b expression from 20 to 48 hpf. (Ai) Section at 26 hpf, displaying aorta (a) and vein (v) and notochord (n). (Aii-iii) ventral view at 36 and 48 hpf. (B) WISH of hapln1b expression at 4 and 5 dpf. (Biv-v) Dorsal view at 4 and 5 dpf. (C-E) Experimental outline and qPCR expression of hapln1b from FACS-sorted endothelial cells. (F) qPCR expression of hapln1b in FACS-sorted hematopoietic progenitors (EMPs and HSPCs). All qPCR data are from biological triplicates (except for whole GFP− in panel D, where data represent biological duplicates). Data indicate expression relative to ef1a (calculated by [2Ct(hapln1b) − Ct(ef1a)] × 10 000). (D) Two-tailed Student t-test, whole GFP− and GFP+; P = .0035; heads and tails, P = .75. (E-F) Analysis was performed by 1-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons. (E) Whole GFP− and GFP+, P = .99; whole GFP− and heads, P = .44; and whole GFP− and tails, P = .99. (F) Whole and EMPs, P = .0081; whole and HSPCs, P = .0449. (G) SMART (http://smart.embl.de/) prediction of hapln1b protein structure. IG, immunoglobulinlike domain; Link, HA Link domain; aa, amino acid.

We then further analyzed the expression of hapln1b in different cell populations. We sorted endothelial cells from dissected kdrl:eGFP embryos at 26 and 48 hpf (Figure 1C), as previously described.25 Consistent with the WISH, hapln1b was enriched in endothelial cells extracted from whole embryos at 26 hpf (Figure 1D) but no enrichment was noted at 48 hpf (Figure 1E), concordant with our WISH data. However, hapln1b was also highly enriched in early EMPs (lmo2:GFP+gata1:DsRed+cells at 28 hpf)5 and nascent HSPCs (kdrl:mCherry+cmyb:GFP+ cells at 36 hpf),18 compared with whole embryos at 28 hpf (Figure 1F), which showed a potential link between hapln1b and embryonic definitive hematopoiesis. Amino acid structural analysis (using SMART; http://smart.embl.de/) revealed that hapln1b contains an immunoglobulin domain and 2 HA link domains (Figure 1G). We next investigated how this ECM protein interferes with developmental hematopoiesis.

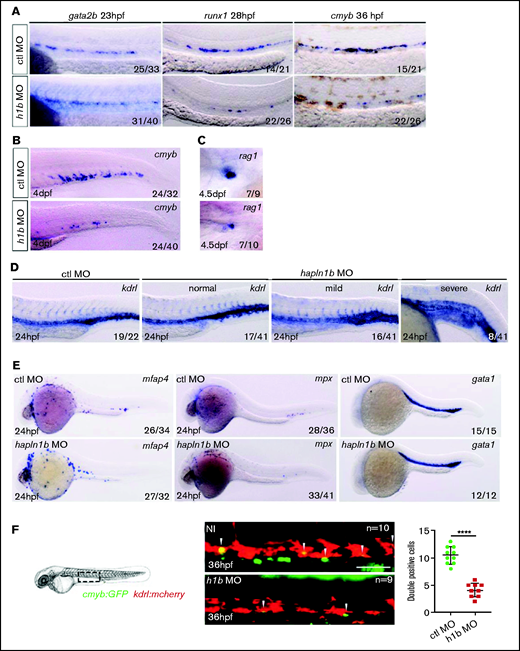

Hapln1b is necessary for specifying HSPCs from the HE

To further investigate the role of this gene in hematopoiesis, we injected a splice-blocking MO for hapln1b. This process efficiently reduced the mRNA levels (supplemental Figure 4B-C), either because the nonspliced RNA was too long to be amplified, or because the resulting RNA was degraded. Inhibiting hapln1b expression did not affect gata2b expression, the earliest known marker of HE specification17 (Figure 2A). However, runx1 and cmyb expression was robustly decreased in the aortic region (Figure 2A). Accordingly, additional downstream expression of cmyb at 4 dpf in the CHT and rag1 at 4.5 dpf in the thymus were also decreased (Figure 2A-C). To further validate the specificity of our MO, we then rescued the loss of runx1 in hapln1b morphants by coinjecting the MO with hapln1b mRNA (supplemental Figure 4D). Hapln1b morphants displayed normal vascular specification, although in some cases the formation of the CHT was perturbed, as seen in the “mild” cases (Figure 2D) and as previously described.31 In a small number of embryos, the vasculature was severely affected as represented in the “severe” phenotype (Figure 2D). We then further analyzed the development of both the aorta and vein and found that hapln1b morphants had an increased diameter of the vein and a slight decreased aortic diameter (supplemental Figure 3A-B). We observed no change in the emergence of primitive macrophages or red blood cells, as marked by mfap4 and gata1 at 24 hpf (Figure 2E), respectively, although some embryos displayed a decrease in mfap4 cells in the tail region, possibly because of disrupted vasculature formation (Figure 2E). We noted, however, a decrease in primitive circulating neutrophils, as marked by mpx (Figure 2E), although neutrophils were still present on the yolk sac. This change in distribution, as for macrophages, may be related to the loss of function of the vasculature depicted in Figure 2D. Loss of hapln1b thus results in a loss of HSPCs but does not affect primitive hematopoiesis. We next sought to confirm the loss of HSPCs in hapln1b morphants by using confocal imaging in double-transgenic kdrl:mCherry;cmyb:eGFP embryos. The images revealed a similar decrease in HSPC budding (Figure 2F) that correlated with the loss of runx1 and cmyb expression shown in Figure 2A, but no change in circulating cells when imaged at 30 hpf (supplemental Movies 1 [control (ctrl) MO; n = 3] and 2 [h1b MO; n = 3]). We then investigated the effect of hapln1b overexpression on embryonic hematopoiesis.

Hapln1b is necessary for the specification of HSPC from the hemogenic endothelium. (A) Gata2b, runx1, and cmyb ISH in control MO, or hapln1b MO-injected embryos (injected at 3 ng throughout, unless otherwise stated). (B) ISH expression of cmyb, in control MO–, or hapln1b MO–injected embryos. (C) Rag1 expression in the thymus after control MO or hapln1b MO injection. (D) ISH expression of kdrl in control MO– or hapln1b MO–injected embryos. Hapln1b morphants displayed 3 phenotypes: normal, mild, and severe. (E) ISH expression of mfap4, mpx, and gata1 in control MO– or hapln1b MO–injected embryos. H1b, hapln1b. (F) Imaging double-transgenic kdrl:mCherry/cmyb:GFP embryos at 36 hpf. Bar represents 50 µm. Control (ctl) MO vs hapln1b mRNA injected, P < .0001. Student unpaired t-test.

Hapln1b is necessary for the specification of HSPC from the hemogenic endothelium. (A) Gata2b, runx1, and cmyb ISH in control MO, or hapln1b MO-injected embryos (injected at 3 ng throughout, unless otherwise stated). (B) ISH expression of cmyb, in control MO–, or hapln1b MO–injected embryos. (C) Rag1 expression in the thymus after control MO or hapln1b MO injection. (D) ISH expression of kdrl in control MO– or hapln1b MO–injected embryos. Hapln1b morphants displayed 3 phenotypes: normal, mild, and severe. (E) ISH expression of mfap4, mpx, and gata1 in control MO– or hapln1b MO–injected embryos. H1b, hapln1b. (F) Imaging double-transgenic kdrl:mCherry/cmyb:GFP embryos at 36 hpf. Bar represents 50 µm. Control (ctl) MO vs hapln1b mRNA injected, P < .0001. Student unpaired t-test.

Hapln1b overexpression is sufficient to reduce HSPC emergence and downstream survival

We next induced overexpression of hapln1b by injecting the full-length mRNA at the 1-cell stage and analyzed the effect on developmental hematopoiesis. Hapln1b overexpression did not change HE programming, vessel development, and early HSPC specification, as marked by gata2b at 22 hpf, kdrl at 24 hpf, and runx1 at 28 hpf, respectively (Figure 3A). However, on further investigation, we found that the aorta presented a smaller diameter, whereas the vein was unaffected (supplemental Figure 3C-D). Moreover, we noted a decrease in cmyb signal at 36 hpf in the AGM region (Figure 3A). Hapln1b overexpression also decreased cmyb signal at 48 hpf in the CHT, suggesting that newly formed HSPCs did not colonize this tissue. The absence of the cmyb signal along the aorta, as in the non-injected controls, indicated that HSPCs were not lodged and were not unable to migrate from the aorta (Figure 3B). Accordingly, rag1 staining in the thymus at 4.5 dpf and cmyb in the CHT at 4 dpf were also decreased (Figure 3C). To further analyze this loss of cmyb signal, we then imaged double-positive kdrl:mCherry;cmyb:eGFP embryos to examine HSPC emergence from the HE.18 Hapln1b overexpression significantly reduced the number of double-positive, nascent HSPCs in the AGM region at 36 and 48 hpf (Figure 3D-D′). As expected, the number of HSPCs present in the CHT niche at 3 and 4 dpf was also significantly reduced (Figure 3E- E′). To further examine this loss of cmyb at 36 hpf from the HE, we used time-lapse confocal microscopy to image double-positive kdrl:mCherry;cmyb:eGFP embryos and examine the endothelial-to-hematopoietic transition events in the aorta. We imaged from 34 to 42 hpf to observe HSPC budding from the HE. We observed clusters of cells in the AGM region of control embryos, preparing to bud and enter circulation (supplemental Movies 3 and 4). However, in hapln1b-overexpressing embryos, almost no cells initiated budding. Occasionally, some cmyb:GFP+ cells were detected, but none underwent endothelial-to-hematopoietic transition (supplemental Movies 5 and 6). We then examined blood circulation at 28 hpf after mRNA injection and found normal circulation in 6 of 10 control (non-injected) embryos (supplemental Movie 7). Only 4 of 10 hapln1b-overexpressing embryos (supplemental Movie 8) showed normal circulation, whereas 6 of 10 embryos showed slower blood circulation. We therefore concluded that hapln1b overexpression is sufficient to prevent normal HSPC budding from the HE.

Hapln1b overexpression inhibits HSPC budding and development. (A) ISH expression of kdrl, runx1, and cmyb in non-injected or hapln1b mRNA–injected embryos. (B-C) ISH expression of cmyb in non-injected or hapln1b mRNA–injected embryos. (D-D′) Double-transgenic kdrl:mCherry/cmyb:GFP embryos at 36 and 48 hpf. Bar represents 50 µm. (D′) NI vs +h1b-injected at 36 hpf, P < .0001; and at 48 hpf, P = .0003. (E-E′) Imaging double-transgenic kdrl:mCherry/cmyb:GFP embryos at 3 and 4 dpf. Bar represents 50 µm. (E′) NI vs +h1b injected at 3 dpf, P = .0003; and at 4 dpf, P = .004. NI, non-injected, +h1b: hapln1b mRNA–injected.

Hapln1b overexpression inhibits HSPC budding and development. (A) ISH expression of kdrl, runx1, and cmyb in non-injected or hapln1b mRNA–injected embryos. (B-C) ISH expression of cmyb in non-injected or hapln1b mRNA–injected embryos. (D-D′) Double-transgenic kdrl:mCherry/cmyb:GFP embryos at 36 and 48 hpf. Bar represents 50 µm. (D′) NI vs +h1b-injected at 36 hpf, P < .0001; and at 48 hpf, P = .0003. (E-E′) Imaging double-transgenic kdrl:mCherry/cmyb:GFP embryos at 3 and 4 dpf. Bar represents 50 µm. (E′) NI vs +h1b injected at 3 dpf, P = .0003; and at 4 dpf, P = .004. NI, non-injected, +h1b: hapln1b mRNA–injected.

We next investigated how hapln1b affects cytokine signaling in the aortic region, which could be responsible for controlling HSPC differentiation.

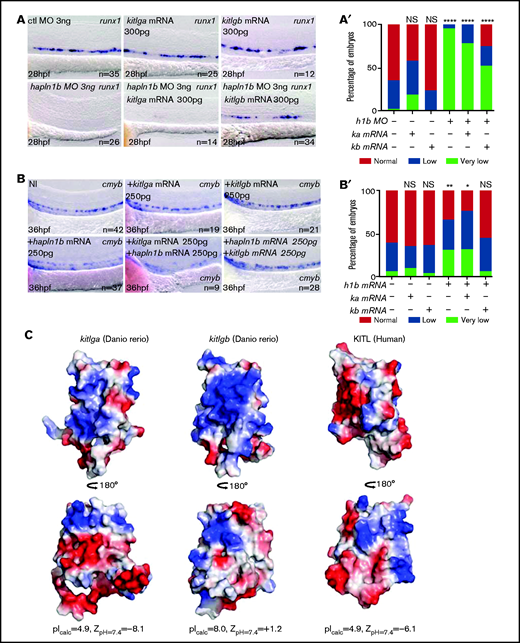

Hapln1b mediates the kitlgb-kitb interactions that are necessary for proper HSPC specification from the HE

We next attempted to decipher the mechanism by which hapln1b affects hematopoiesis. Our previous studies indicated that HSPCs express kitb and that kiltgb and kitb are essential for runx1 expression in the HE at 28 hpf.27 As we found a similar decrease in runx1 in hapln1b morphants, we investigated a possible link between kiltgb signaling and hapln1b. Previous studies have indicated that kitlgb is expressed in the CHT region by ISH at 24 hpf and is likely to exist more commonly as the membrane-bound form, because of a loss of 1 of the 2 cleavage sites.64 By contrast, kitlga represents the more soluble form of this ligand, as it retains the 2 cleavage sites.64 We also investigated the expression of kiltgb in fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)–sorted cells and found no enrichment in globin:GFP+ cells at 20 hpf, primitive macrophages sorted from mpeg1:mcherry embryos at 24 hpf, primitive neutrophils sorted from mpx:eGFP embryos at 24 hpf, or neural crest cells sorted from sox10:mRFP embryos at 26 hpf (supplemental Figure 5A-D). We also found no enrichment of kitlgb in endothelial cells sorted from dissected embryos at 19 to 20 hpf (supplemental Figure 5E). However, we found a significant enrichment in tail endothelial cells at 26 hpf (supplemental Figure 5F), consistent with the previously published ISH expression pattern of kitlgb.64 We therefore concluded that kiltgb would be present in the AGM at low concentrations and that an additional element would be needed to mediate effective interaction with its receptor to initiate runx1 expression. We tested this hypothesis by attempting to rescue the loss of runx1 observed in hapln1b morphants and the loss of cmyb observed in hapln1b-overexpressing embryos by injecting kitlgb mRNA.

To verify the specificity of our kitlgb injection, we also injected kitlga mRNA, which does not play any role in HSPC specification and development.27 Injection of either kitlga or kitlgb did not alter the expression of runx1 at 28 hpf, as anticipated. Injection of the hapln1b MO induced a similar loss of runx1 at 28 hpf (Figure 4A-A′). We then coinjected the hapln1b MO with kitlgb mRNA, which resulted in a rescue of the runx1 signal in 16 of 34 embryos (Figure 4A-A′). As expected, kiltga did not rescue the loss of runx1 in hapln1b morphants (Figure 4A-A′). We then attempted to rescue the decrease of cmyb signal in the hapln1b-overexpressing embryos by injecting kitlgb mRNA. Compared with non-injected controls, hapln1b mRNA reduced cmyb expression at 36 hpf, as observed earlier (Figure 4B-B′). Although kitlgb injection alone did not alter cmyb expression at 36 hpf (Figure 4B-B′), coinjection of both hapln1b and kitlgb mRNAs increased cmyb expression to control levels (Figure 4B-B′). Altogether, the data suggest that the dose of hapln1b controls accessibility of kitlgb to the HE.

Hapln1b interacts with kitlgb to maintain kitlgb-kitb interactions in the AGM. (A) ISH expression pattern of runx1 in control morphants, kitlga mRNA–injected embryos, kitlgb mRNA–injected embryos, hapln1b morphants, embryos injected with both hapln1b MO and kitlga mRNA, and embryos injected with both hapln1b MO and kitlgb mRNA. (A′) Analysis of runx1 expression. All results are compared with control MO. Data were analyzed by Fisher’s exact test using R. Control (ctl) MO vs +kitlga, P = .05826; NI vs +kitlgb, P = .7939; NI vs +hapln1b, P < .0001; NI vs +hapln1b+kitlga, P < .0001; and NI vs +hapln1b+kitgb: P < .0001. (B) ISH expression of cmyb in NI control embryos, hapln1b mRNA–injected embryos, kitlgb mRNA–injected embryos, and embryos injected with both hapln1b and kitlgb. (B′) analysis of cmyb expression. All analysis is compared with the NI control. Data were analyzed by Fisher’s exact test using R. NI vs +kitlga, P = .8373; NI vs +kitlgb, P = .99; NI vs +hapln1b, P = .0051; NI vs +hapln1b+kitlga, P = .036; and NI vs +hapln1b+kitgb, P = .8617. h1b, hapln1b; ka, kitlga; Kb, kitlgb. (C) Electrostatic potential of KITL, kiltga and kitlgb at biological pH. Blue, positive charge; white, neutral charge; red, negative charge. NI, non-injected.

Hapln1b interacts with kitlgb to maintain kitlgb-kitb interactions in the AGM. (A) ISH expression pattern of runx1 in control morphants, kitlga mRNA–injected embryos, kitlgb mRNA–injected embryos, hapln1b morphants, embryos injected with both hapln1b MO and kitlga mRNA, and embryos injected with both hapln1b MO and kitlgb mRNA. (A′) Analysis of runx1 expression. All results are compared with control MO. Data were analyzed by Fisher’s exact test using R. Control (ctl) MO vs +kitlga, P = .05826; NI vs +kitlgb, P = .7939; NI vs +hapln1b, P < .0001; NI vs +hapln1b+kitlga, P < .0001; and NI vs +hapln1b+kitgb: P < .0001. (B) ISH expression of cmyb in NI control embryos, hapln1b mRNA–injected embryos, kitlgb mRNA–injected embryos, and embryos injected with both hapln1b and kitlgb. (B′) analysis of cmyb expression. All analysis is compared with the NI control. Data were analyzed by Fisher’s exact test using R. NI vs +kitlga, P = .8373; NI vs +kitlgb, P = .99; NI vs +hapln1b, P = .0051; NI vs +hapln1b+kitlga, P = .036; and NI vs +hapln1b+kitgb, P = .8617. h1b, hapln1b; ka, kitlga; Kb, kitlgb. (C) Electrostatic potential of KITL, kiltga and kitlgb at biological pH. Blue, positive charge; white, neutral charge; red, negative charge. NI, non-injected.

As proteoglycans are negatively charged, we sought to examine the possible electrostatic compatibility of kitlgb with such a biological environment. In the absence of an experimentally determined structure for zebrafish kitlgb and kitlga, we leveraged available structural information at high resolution on human KITL (SCF) 65,66 and the related hematopoietic cytokines Flt3 ligand and colony-stimulating factor 1,67-69 to derive reliable models based on homology-based approaches and ab initio structure prediction.

Our analysis revealed that Kitlgb would be expected to display an overall positive electrostatic potential as manifested by a Z-potential value of +1.2 mV at physiological pH and as illustrated by extensive patches of positively charged amino acids at the protein surface (Figure 4C). Such physicochemical properties are in sharp contrast to zebrafish Kitlga and human KITL, which are pronouncedly acidic with very similar electrostatic properties characterized by strongly negative electrostatic ζ-potentials at physiological pH. As proteoglycans are negatively charged, the overall positively charged Kitlgb, but not the negatively charged Kitlga, would mediate favorable interactions with the ECM in hemogenic and hematopoietic tissues, therefore activating the Kitb receptor, consistent with our findings.

Finally, to further confirm that hapln1b expression is necessary for kitlgb signaling we examined phospho-AKT, a downstream marker of the kit receptor activation.70 Control MO– and kitlgb mRNA-injected embryos showed a robust increase in the number of phospho-AKT+ cells in the dorsal aorta (supplemental Figure 6A-B). Hapln1b morphants displayed a large decrease in phospho-AKT+ cells in the DA, which was rescued in kitlgb mRNA–injected hapln1b morphants (supplemental Figure 6A-B). We then coinjecting MOs at half doses and confirmed that signaling of both hapln1b and kitlgb is required for HSPC specification. Half-dose hapln1b morphants showed a moderate decrease in runx1 (supplemental Figure 6C). Half-dose kitlgb morphants showed normal runx1 expression (supplemental Figure 6C). Half-dose hapln1b/kitlgb double morphants showed a robust decrease in runx1 expression (supplemental Figure 6C), suggesting an interaction of both genes to specify HSPCs.

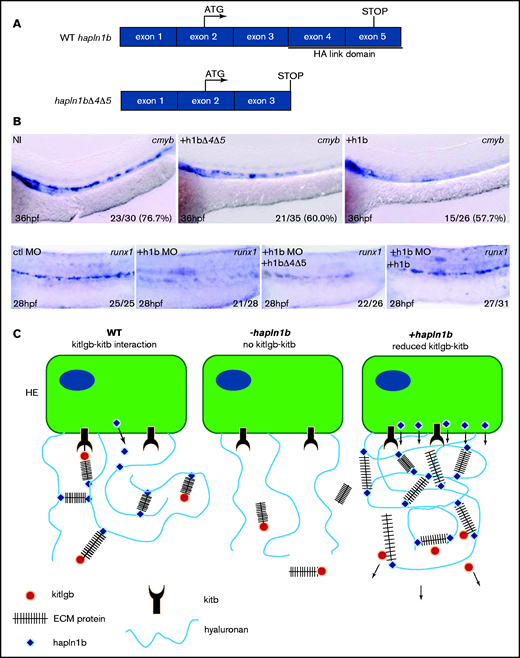

The link domain is necessary for hapln1b functions

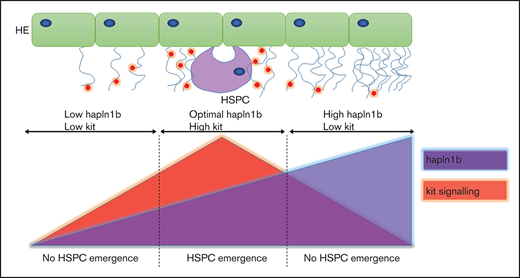

Finally, we wanted to verify that hapln1b interacts with HA through its link domain. We cloned a truncated version of the hapln1b mRNA lacking exons 4 and 5 (hapln1bΔ4Δ5), which encode the HA link domain (Figure 5A). Compared with the non-injected controls, hapln1bΔ4Δ5 mRNA–injected specimens did not show a reduction of cmyb levels at 36 hpf, whereas wild-type hapln1b mRNA–injected specimens did (Figure 5B), as shown earlier (Figure 3A). Furthermore, hapln1b full-length mRNA, and not hapln1bΔ4Δ5 mRNA, rescued the loss of runx1 at 28 hpf, observed in hapln1b morphants (Figure 5B), when the product of both mRNAs (HA-tagged versions) were detected at 24 hpf (supplemental Figure 4E). We therefore concluded that the link domain is necessary for hapln1b to fulfill its function: the assembly of the ECM. We therefore propose the following model, wherein kitlgb is distributed along the aorta by interacting with the ECM. The ECM structure is maintained by proteoglycans forming links with the HA backbone (mediated by the link domain of hapln1b), enabling kiltgb to reach the AGM. A loss of hapln1b will prevent HA links from being formed and will prevent kitlgb distribution to the AGM, reducing runx1 expression (Figure 5C). When hapln1b is overexpressed, HSPC budding is reduced as the HA links are increased, resulting in a tight ECM that would also reduce kitlgb distribution to the AGM. Therefore, a lower concentration of kitlgb in the AGM would result in the budding and development of fewer HSPCs (Figure 5C).

Hapln1b overexpression inhibits cmyb through interactions mediated by the link domains. (A) Schematic representation of WT hapln1b and a truncated version that lacks exons 4 and 5 (hapln1bΔ4Δ5). (B) ISH expression of cmyb in NI control embryos, hapln1b mRNA–injected embryos and hapln1bΔ4Δ5-injected embryos at 36 hpf. ISH expression of runx1 in control MO (ctl MO), hapln1b MO (h1b MO), hapl1b MO, and hapln1bΔ4Δ5 mRNA–injected (h1b MO and h1bΔ4Δ5), and hapl1b MO and hapln1b full-length mRNA (h1bMO and h1b)–injected embryos at 28 hpf. (C) Summary of proposed model. In the wild-type situation, hapn1b helps kitlgb to interact with kitb in the AGM to permit runx1 expression and HSPC formation. Loss of hapln1b results in a loss of kitlgb interaction with kitb, no runx1 expression, and no HSPCs forming. Overexpression of hapln1b results in a dense ECM and reduced kitlgb interaction with kitb, impairing HSPC emergence and survival. HE, hemogenic endothelium; NI, non-injected.

Hapln1b overexpression inhibits cmyb through interactions mediated by the link domains. (A) Schematic representation of WT hapln1b and a truncated version that lacks exons 4 and 5 (hapln1bΔ4Δ5). (B) ISH expression of cmyb in NI control embryos, hapln1b mRNA–injected embryos and hapln1bΔ4Δ5-injected embryos at 36 hpf. ISH expression of runx1 in control MO (ctl MO), hapln1b MO (h1b MO), hapl1b MO, and hapln1bΔ4Δ5 mRNA–injected (h1b MO and h1bΔ4Δ5), and hapl1b MO and hapln1b full-length mRNA (h1bMO and h1b)–injected embryos at 28 hpf. (C) Summary of proposed model. In the wild-type situation, hapn1b helps kitlgb to interact with kitb in the AGM to permit runx1 expression and HSPC formation. Loss of hapln1b results in a loss of kitlgb interaction with kitb, no runx1 expression, and no HSPCs forming. Overexpression of hapln1b results in a dense ECM and reduced kitlgb interaction with kitb, impairing HSPC emergence and survival. HE, hemogenic endothelium; NI, non-injected.

Discussion

We have shown that hapln1b is expressed along the embryonic endothelium before HSPC emergence, before it becomes restricted to non hematopoietic tissue at later stages (Figure 1). Hapln1b is required, in the correct concentration, to specify HSPCs from the HE and to maintain HSPC budding and release into circulation. We found that loss of hapln1b results in a loss of runx1 and of downstream HSPC specification markers (Figure 2A-C). As proteoglycans can bind cytokines, it is possible that hapln1b is responsible for maintaining HA linking to proteoglycans to favor cytokine-receptor interaction. This notion was corroborated by a recent study showing that HA glycosaminoglycans are closely associated with early Flk1+ hematoendothelial cell progenitors during gastrulation and act as a cytokine trap to enhance VEGF-mediated angiogenesis and primitive hematopoiesis.71 Our previous data have shown that kitlgb-kitb signaling is essential for maintaining runx1 expression and HSPC specification in the HE.27 However, we and others64 have demonstrated that kitlgb is highly expressed in the posterior blood island but not in the aortic HE region. When we modulated hapln1b expression, we were able to change the structure of the ECM, as the loss of hapln1b affects the vasculature in the CHT vessels and affects the overall CHT structure (Figure 2D). The disruption of the CHT structure after hapln1b knockdown was also noted in a previous study.31 This, coupled with the fact that hapln1b morphants were rescued with kitlgb mRNA injections (Figure 4A), leads us to conclude that hapln1b mediates HA linking with proteoglycans and is responsible for stabilizing the ECM scaffold and distributing kitlgb to the HE (Figure 5C). Our data show that the ECM most likely plays a crucial role in maintaining the signaling environment in proximity to the AGM, to mediate HSPC specification from the HE. Furthermore, our results showed an involvement of the ECM in the CHT, further suggesting that the ECM is a key player in maintaining the embryonic niche to help in expanding HSPCs. Although we have highlighted kiltgb as a key cytokine that interacts with the ECM, there are most likely many others that contribute to the extrinsic signaling microenvironment. Fully characterizing and understanding these molecules is an important step in improving the currently challenging derivation of HSPCs from iPSCs.

In contrast to our loss-of-function assays, overexpression of hapln1b resulted in normal HSPC specification, as indicated by normal runx1 expression (Figure 3A), but caused a reduction in HSPC emergence and later expansion within the hematopoietic tissue, as indicated by a reduction of cmyb expression (Figure 3B). As we found that HSPC emergence was reduced, but never completely ablated, we reasoned that overexpression of hapln1b is likely to result in a denser ECM, reducing the accessibility of kitlgb to the hemogenic microenvironment. We confirmed this by rescuing HSPC expansion in hapln1b-overexpressing embryos by overexpressing kiltgb mRNA (Figure 4B). Recent mouse studies have indicated that Kitlg is required throughout HSPC development in the AGM region.72 This was further corroborated by additional studies showing that c-kit is expressed by proliferating HSPCs in the AGM73 and that Kitlg maintains HSPCs in mouse AGM cultures.74 It is therefore likely that reducing the concentration of kitlgb in our hapln1b-overexpressing embryos restricts HSPC emergence and decreases downstream survival and HSPC maturation (Figure 5C). It is also possible that the ECM is too dense to enable HSPC to bud and migrate to the CHT, as results in previous studies have indicated that ECM degradation, 23,24 biomechanical forces exerted by blood flow,75 and mechanical instability in the aorta76 are essential for HSPCs to enter the blood circulation.

A similar role for Hapln1 has been demonstrated in the PNNs in the mouse central nervous system, as it is necessary for maintaining the HA mesh surrounding the neurons.38 These PNNs bind molecules to maintain neuronal plasticity and development, further implicating this gene in maintaining the ECM. Recent studies have shown that HSPCs migrate to the fetal niche and the CHT and expand their initial number in response to several cytokines.23,25,26 It is possible that many cytokine gradients and concentrations are maintained in the fetal niche by ECM components, such as hapln1b. Understanding them in more detail helps in fully characterizing HSPC expansion and provides alternative methods of improving HSPC expansion ex vivo.

Acknowledgments

J.Y.B. holds a Chair in Life Sciences funded by the Gabriella Giorgi-Cavaglieri Foundation and is also funded by the Swiss National Fund (310030_184814) and the “Fondation Privée des HUG”. R.M. and C.B.M. were funded by a British Heart Foundation IBSR Fellowship (FS/13/50/30436).

Authorship

Contribution: S.N.S. performed structural analysis of KITL, kitlga, and kitlgb; C.B.M., P.C., and C.P. performed the experiments; C.B.M. and J.Y.B. designed the research and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript; and S.N.S. and R.M. edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Christopher B. Mahony, Institute of Cancer and Genomic Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham B152TT, United Kingdom; E-mail: c.mahony@bham.ac.uk; and Julien Y. Bertrand, University of Geneva, CMU, Rue Michel-Servet, 1, Geneva 4 1211, Switzerland; e-mail: julien.bertrand@unige.ch.

References

Author notes

All important information can be obtained by contacting the corresponding authors (c.mahony@bham.ac.uk and julien.bertrand@unige.ch). All raw data will be accessible on the YARETA public server once the manuscript is accepted using this DOI: 10.26037/yareta:gkc7f4ro4rbnfioo7ryiqpwqda

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![Hapln1b is expressed by vascular cells and hematopoietic progenitors. (A) WISH of hapln1b expression from 20 to 48 hpf. (Ai) Section at 26 hpf, displaying aorta (a) and vein (v) and notochord (n). (Aii-iii) ventral view at 36 and 48 hpf. (B) WISH of hapln1b expression at 4 and 5 dpf. (Biv-v) Dorsal view at 4 and 5 dpf. (C-E) Experimental outline and qPCR expression of hapln1b from FACS-sorted endothelial cells. (F) qPCR expression of hapln1b in FACS-sorted hematopoietic progenitors (EMPs and HSPCs). All qPCR data are from biological triplicates (except for whole GFP− in panel D, where data represent biological duplicates). Data indicate expression relative to ef1a (calculated by [2Ct(hapln1b) − Ct(ef1a)] × 10 000). (D) Two-tailed Student t-test, whole GFP− and GFP+; P = .0035; heads and tails, P = .75. (E-F) Analysis was performed by 1-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons. (E) Whole GFP− and GFP+, P = .99; whole GFP− and heads, P = .44; and whole GFP− and tails, P = .99. (F) Whole and EMPs, P = .0081; whole and HSPCs, P = .0449. (G) SMART (http://smart.embl.de/) prediction of hapln1b protein structure. IG, immunoglobulinlike domain; Link, HA Link domain; aa, amino acid.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/5/23/10.1182_bloodadvances.2020001524/2/m_advancesadv2020001524f1.png?Expires=1769086676&Signature=RtqoQZe~4hdX6~XeK2vp~fr8XePZpABsY9qufVoFjA~0yesck-3VUKzatb0FFRDGB5kdfsMRAlY4HFncTLgRVdEiMkXp1qeuVWp3mA~EnB7SMWCeorUBnaTV9vUej-DvV-v2kqxJt8wu0WhdfoNtIwbhJ-10eSZFuwM5fNmPFhjdUbY2rpKOtVCIBDFP5jJOnpdvX9WRSvn6ZAJ-f9L64iRnNmOnOCRDKcA9y5Wk33M4vhs~oF-NRPXpJMOeYymaNYQuB5mru5DC1bFsHgF9IjGph55CMY247DJI4Yl95fLOi9frzMT9PNt-YhHjcy7JInhKZP7qGWNm2q3H-YoNAA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)