Key Points

Macrophage FVIIa-PAR2 signaling supports fetal liver erythropoiesis.

Macrophage PAR2 signaling is dispensable for the postnatal steady-state but contributes to stress-induced erythropoiesis.

Abstract

Deficiencies in many coagulation factors and protease-activated receptors (PARs) affect embryonic development. We describe a defect in definitive erythropoiesis in PAR2-deficient mice. Embryonic PAR2 deficiency increases embryonic death associated with variably severe anemia in comparison with PAR2-expressing embryos. PAR2-deficient fetal livers display reduced macrophage densities, erythroblastic island areas, and messenger RNA expression levels of markers for erythropoiesis and macrophages. Coagulation factor synthesis in the liver coincides with expanding fetal liver hematopoiesis during midgestation, and embryonic factor VII (FVII) deficiency impairs liver macrophage development. Cleavage-insensitive PAR2-mutant mice recapitulate the hematopoiesis defect of PAR2-deficient embryos, and macrophage-expressed PAR2 directly supports erythroblastic island function and the differentiation of red blood cells in the fetal liver. Conditional deletion of PAR2 in macrophages impairs erythropoiesis, as well as increases inflammatory stress, as evidenced by upregulation of interferon-regulated hepcidin antimicrobial peptide. In contrast, postnatal macrophage PAR2 deficiency does not have any effect on steady-state Kupffer cells, bone marrow macrophage numbers, or erythropoiesis, but erythropoiesis in macrophages from PAR2-deficient mice is impaired following hemolysis. These data identify a novel function for macrophage PAR2 signaling in adapting to rapid increases in blood demand during gestational development and postnatal erythropoiesis under stress conditions.

Introduction

The primary function of the blood coagulation cascade is to prevent blood loss and assure hemostasis after vessel injury, but expanding evidence shows that the hemostatic system also regulates hematopoiesis in the bone marrow niche.1-3 In addition, deficiencies in coagulation factors and protease activated receptors (PARs) affect mouse embryonic development. For example, embryos deficient in tissue factor (TF),4-6 coagulation factor V (FV) and prothrombin,7,8 and the thrombin receptor PAR19 die in early gestation because yolk sac vasculature fails to develop. In contrast, FX-deficient10 and FVII-deficient11 embryos do not suffer from embryonic lethality because of maternal rescue; nevertheless, they die from perinatal hemorrhage.

Although platelet thrombin receptor–deficient PAR3−/− and PAR4−/− mice develop normally,12 PAR2−/− mice on a mixed genetic background display a partial, albeit poorly defined, embryonic lethality.13 Mice with double deficiency in PAR1 and PAR2 show a highly penetrant embryonic lethality in comparison with single PAR1 or PAR2 deficiency,14 suggesting partial compensation of these 2 receptors during embryogenesis. A prominent neural closure defect during midgestational development of double-deficient mice indicates that epithelial cell–expressed matriptase, a potent PAR2 activator, regulates epithelial integrity. However, mice with combined deficiency of PAR2 and matriptase also show synthetic lethality and die on or before embryonic day 14.5 (E14.5) as the result of an aberrant feto-maternal barrier and selective deficiency in expression of the tight junction protein claudin-1 in the placenta.15 Given the apparently complex interactions between proteases and PARs in different tissues, additional insights into these developmental pathways can be expected from studies with cell type–specific PAR deletions in mice.

In addition to the documented interactions of PARs in embryonic development, PAR2 in particular has been shown to interact with other signaling receptors,16 including innate immune Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4).17-20 Although PAR2 is a target for upstream coagulation protease complexes (ie, TF-FVIIa and the TF-FVIIa-FXa initiation complex),19,21,22 further complexity arises from cross talk of coagulation and transmembrane protease cascades that also efficiently activate PAR2.23,24 Although transmembrane protease cascades likely regulate neural crest development through PAR2,14 it is clear that control of coagulation initiation by TF during embryonic development is also required, as demonstrated by the lethality of knockouts of the first Kunitz domain of TF pathway inhibitor that is apparent during midgestation.25,26 These phenotypes coincide with establishment of definitive hematopoiesis in the liver that bridges to postnatal bone marrow hematopoiesis during embryonic development.27 Here, we describe a pivotal role for macrophage-expressed PAR2 in regulating fetal erythropoiesis and use cleavage-insensitive PAR2-mutant mice to confirm the requirement for proteolytic activation of embryo-expressed PAR2 during gestational development.

Materials and methods

Mice

Mice were bred in the animal facilities at Scripps Research or in the Translational Animal Research Center of the University Medical Center Mainz. PAR2flfl mice (F2rl1tm3.1Ruf)22 were crossed with LysMcre mice [Lyz2tm1(cre)Ifo] for myeloid cell PAR2 deletion or with a ubiquitously expressed cre strain to generate PAR2−/− mice. PAR2 R38E/R38E (F2rl1tm1.1Ruf) mice were generated by the same targeting strategy, introducing an Arg 38 to Glu mutation preventing canonical activation by all proteases.28 C57BL/6N mice or littermate PAR2flfl mice were used as controls. We also used independently generated PAR2−/− mice backcrossed with C57BL/6J13 and FVII-deficient mice that were obtained by an unintended nucleotide insertion following CRISPR targeting and resulting stop codons in the beginning of the FVII heavy chain, which led to messenger RNA (mRNA) decay. All animal experiments were performed under approved protocols of the Scripps Research Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee or at the Johannes Gutenberg University Medical Center Mainz with approval of the local authorities.

Timed mating

Female mice of the indicated genotypes were mated overnight with male mice, and embryos were recovered after defined periods of embryonic development. Organs were collected for fetal liver histology and RNA expression analyses, as well as genotyping. All RNA expression analyses presented in the article were from mice with no visible anemia. Homozygous PAR2−/− embryos were collected from timed mating of PAR2−/− parents at E19.5 for blood analysis.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

Reagents were obtained from Thermo Fisher, with the exception of phenol and chloroform (Sigma-Aldrich). Fetal livers or livers from 9- to 10-week-old adult mice were collected in TRIzol Reagent, RNA was isolated by phenol-chloroform extraction followed by genomic DNA digestion using a TURBO DNA-free DNase kit, and 100 ng of RNA was used to synthesize complementary DNA using SuperScript VILO Master Mix. mRNA expression was analyzed using Applied Biosystems SYBR Green PCR Master Mix and CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad), using the 2−ΔΔCT method and normalized to r18s as a housekeeping gene. The expression of hepcidin antimicrobial peptide 1 (Hamp-1) was also normalized to F4/80 expression (normalized Hamp-1/normalized F4/80) or to DNase II expression (normalized Hamp-1/normalized DNase II) for the corresponding embryo. The primer pairs used are shown in Table 1.

PCR primers used in this study

| Primer . | Forward primer (5′-3′) . | Reverse primer (5′-3′) . |

|---|---|---|

| r18s | CTTAGAGGGACAAGTGGCG | ACGCTGAGCCAGTCAGTGTA |

| KLF-1 | AGAAGAGAGAGAGGAGGC | AGTGCCGGGAGACTCGGAA |

| GATA-1 | TATGGCAAGACGGCACTCTAC | GGTGTCCAAGAACGTGTTGTT |

| Bcl-11a | TGGTATCCCTTCAGGACTAGGT | TCCAAGTGATGTCTCGGTGGT |

| β-globin | ATGGCCTGAATCACTTGGAC | ACGATCATATTGCCCAGGAG |

| F4/80 | CTCTGTGGTCCCACCTTCAT | GATGGCCAAGGATCTGAAAA |

| Mcam (CD146) | CCCAAACTGGTGTGCGTCTT | GGAAAATCAGTATCTGCCTCTCC |

| Id3 | CTGTCGGAACGTAGCCTGG | GTGGTTCATGTCGTCCAAGAG |

| Nr1h3 (LXR-a) | CTCAATGCCTGATGTTTCTCCT | TCCAACCCTATCCCTAAAGCAA |

| EpoR | GGGCTCCGAAGAACTTCTGTG | ATGACTTTCGTGACTCACCCT |

| DNase II | GAGACGGTGATCAAGAACCAA | AATTTTGCCAGAACTGGACCT |

| Hamp-1 | TTGCGATACCAATGCAGAAGA | GATGTGGCTCTAGGCTATGTT |

| Aif1 | CTTGAAGCGAATGCTGGAGAA | GGCAGCTCGGAGATAGCTTT |

| Csfr1 (CD115) | TGTCATCGAGCCTAGTGGC | GGTCCAAGGTCCAGTAGGG |

| Trem-2 | CTGGAACCGTCACCATCACTC | CGAAACTCGATGACTCCTCGG |

| Hexb | GAGTGCGAGTCCTTCCCTAGT | CTAAACCTCGTAACGCTCCCC |

| P2ry12 | TTCCTGGGGTTGATAACCATTG | GGTGAGAATCATGTTAGGCAGTG |

| Tmem-119 | CCTACTCTGTGTCACTCCCG | CACGTACTGCCGGAAGAAATC |

| Prothrombin | CTGGTTATAAAGGGCGGGTGAC | GCCAGCACAGAACATGTTGTCAG |

| FVII | CCGTCTCCCCGTAGCTGCCT | TGCGGCACAATTCACGTGTCCT |

| FX | TTCCGGATGAACGTGGCCCCT | ATGCGTGCGTCCAAAACCGCT |

| Primer . | Forward primer (5′-3′) . | Reverse primer (5′-3′) . |

|---|---|---|

| r18s | CTTAGAGGGACAAGTGGCG | ACGCTGAGCCAGTCAGTGTA |

| KLF-1 | AGAAGAGAGAGAGGAGGC | AGTGCCGGGAGACTCGGAA |

| GATA-1 | TATGGCAAGACGGCACTCTAC | GGTGTCCAAGAACGTGTTGTT |

| Bcl-11a | TGGTATCCCTTCAGGACTAGGT | TCCAAGTGATGTCTCGGTGGT |

| β-globin | ATGGCCTGAATCACTTGGAC | ACGATCATATTGCCCAGGAG |

| F4/80 | CTCTGTGGTCCCACCTTCAT | GATGGCCAAGGATCTGAAAA |

| Mcam (CD146) | CCCAAACTGGTGTGCGTCTT | GGAAAATCAGTATCTGCCTCTCC |

| Id3 | CTGTCGGAACGTAGCCTGG | GTGGTTCATGTCGTCCAAGAG |

| Nr1h3 (LXR-a) | CTCAATGCCTGATGTTTCTCCT | TCCAACCCTATCCCTAAAGCAA |

| EpoR | GGGCTCCGAAGAACTTCTGTG | ATGACTTTCGTGACTCACCCT |

| DNase II | GAGACGGTGATCAAGAACCAA | AATTTTGCCAGAACTGGACCT |

| Hamp-1 | TTGCGATACCAATGCAGAAGA | GATGTGGCTCTAGGCTATGTT |

| Aif1 | CTTGAAGCGAATGCTGGAGAA | GGCAGCTCGGAGATAGCTTT |

| Csfr1 (CD115) | TGTCATCGAGCCTAGTGGC | GGTCCAAGGTCCAGTAGGG |

| Trem-2 | CTGGAACCGTCACCATCACTC | CGAAACTCGATGACTCCTCGG |

| Hexb | GAGTGCGAGTCCTTCCCTAGT | CTAAACCTCGTAACGCTCCCC |

| P2ry12 | TTCCTGGGGTTGATAACCATTG | GGTGAGAATCATGTTAGGCAGTG |

| Tmem-119 | CCTACTCTGTGTCACTCCCG | CACGTACTGCCGGAAGAAATC |

| Prothrombin | CTGGTTATAAAGGGCGGGTGAC | GCCAGCACAGAACATGTTGTCAG |

| FVII | CCGTCTCCCCGTAGCTGCCT | TGCGGCACAATTCACGTGTCCT |

| FX | TTCCGGATGAACGTGGCCCCT | ATGCGTGCGTCCAAAACCGCT |

Analysis of fetal liver erythropoiesis by flow cytometry

Fetal livers from E15.5 PAR2flfl-LysMcre+/−, PAR2flfl, or PAR2−/− embryos were cooled on ice, and single-cell suspensions were obtained by passing through a 30-µm filter, achieving mechanical dispersion in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline with 0.5% bovine serum albumin, 2 mM EDTA. Live cells were identified by Fixable Viability Dye eFluor 506 (Invitrogen). Erythrocyte differentiation was quantified on Fc-blocked samples stained with CD71-PerCP-eFluor 710 and Ter119-FITC (Invitrogen).29 Flow cytometry measurements were performed on an Attune NxT flow cytometer (Thermo Fisher).

Histology

Fetal livers were fixed in phosphate-buffered formaldehyde solution 4% (Roti-Histofix 4%; Roth) and embedded in paraffin, and 2.5- to 3-µm-thick sections were processed for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining or immunohistochemistry. For macrophage staining, deparaffinized sections were treated with proteinase K to retrieve antigen, followed by staining with primary antibody F4/80 antigen (Acris Antibodies; BM4007), biotinylated secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories; BA-4000), and VECTASTAIN Elite ABC-HRP Reagent (Vector Laboratories; PK-7100), according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Images were taken on a Leica DMi microscope using a bright-field 40× objective and acquisition software Leica Application Suite V4.12, and Leica camera model MC170HD (exposure, 30 ms; γ, 0.60; and gain, 1.8×). Photographs were taken of ≥8 field views per mouse for H&E-stained and F4/80-stained samples. Erythroblast islands and F4/80 staining were quantified using ImageJ software by setting a color threshold and determining the average area of erythroid cells and F4/80.

Phenylhydrazine-induced acute hemolytic anemia

Ten- to 12-week-old PAR2flfl-LysMcre+/− or littermate PAR2flfl mice were injected intraperitoneally with phenylhydrazine (50 mg/kg body weight) on 2 consecutive days.29 Blood was taken on days 0, 3, 6, and 9 for blood counts that were performed with a VETSCAN HM5 hematology analyzer (Abaxis).

Peripheral blood analysis

Reticulocytes were stained with New methylene blue solution and nucleated red blood cell (nRBC) counts were determined in blood smears stained with Wright solution from PAR2−/− embryos at E19.5. To analyze blood count in adult mice, vena cava blood from 11- to 12-week-old male and female mice was collected in EDTA tubes and counted using a VETSCAN HM5 hematology analyzer (Abaxis).

Flow cytometry analysis of bone marrow macrophages

Bone marrow cells were flushed out with phosphate-buffered saline, and cell suspensions were recovered by passing through a 70-µm filter. Red cells were lysed with hypotonic buffer, followed by viability staining with Fixable Viability Dye eFluor 506 (Invitrogen) for 30 minutes. Fc block and antibody labeling were performed for 15 minutes in the dark at 4°C, and samples were analyzed on an Attune NxT flow cytometer (Thermo Fisher). The following antibodies were used: CD45 (APC-eFluor 780; clone 30-F11; eBioscience), GR-1 (PE; clone RB6-8C5; eBioscience), CD115 (PE-Cy7; clone AFS98; BioLegend), F4/80 (APC; clone BM8; BioLegend), B220 (FITC; clone RA3-6B2; eBioscience), VCAM-1 (eFluor 450; clone 429; eBioscience).

Statistical analysis

All data are based on ≥3 pregnancies. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism (version 8.0.2; GraphPad Software). For group comparisons, an unpaired Student t test or Mann-Whitney U test was used for analysis of parametric or nonparametric data. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze differences between multiple groups.

Results

PAR2 deficiency causes a partially penetrant severe embryonic anemia

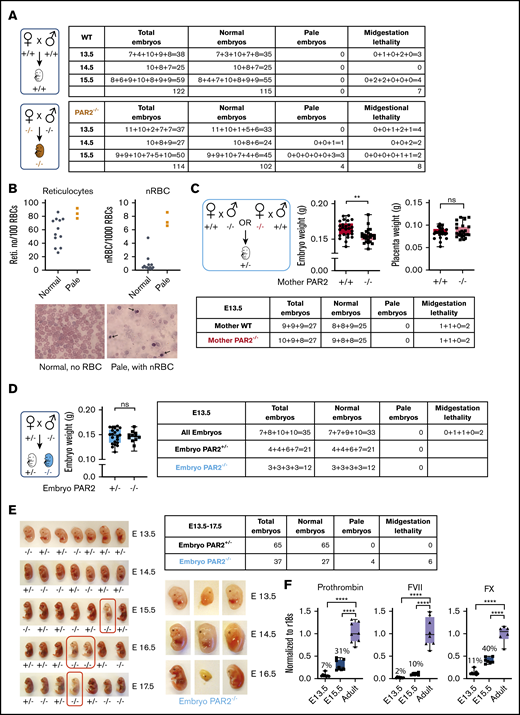

Prior studies showed that PAR2 deficiency causes a partial embryonic lethality on a mixed genetic background13 and severe lethality in combination with PAR1 deletion.14 We generated PAR2flfl mice by homologous recombination of the PAR2 locus in C57BL/6N embryonic stem cells and derived PAR2−/− animals on a homogeneous genetic background by crossing them with a ubiquitously expressed cre-deleter line. We analyzed pregnancies of PAR2−/− mice between E13.5 and E15.5 in comparison with time mated wild-type (WT) parents. Although most of the embryos of both genotypes appeared macroscopically normal, a small, but similar, number of WT and PAR2−/− embryos had died in midgestation and were partially resorbed (Figure 1A).

PAR2 deficiency causes a partially penetrant severe embryonic anemia. (A) WT and PAR2−/− embryos were collected between E13.5 and E15.5 from homozygous mating of WT and PAR2−/− parents, and the numbers of normal, pale, and midgestation dead embryos were determined. The number of embryos are shown for individual pregnancies. (B) The numbers of reticulocytes and nRBCs in peripheral blood were counted in 12 normal and 3 pale PAR2−/− embryos at E19.5. Blood smears were stained with Wright solution. Arrows point to nRBC in the blood from 1 of the pale embryos. (C) PAR2+/− embryos were collected at E13.5 from mating of WT or PAR2−/− mother with PAR2−/− or WT father, respectively, and the numbers of normal, pale, and dead embryos, as well as embryo and placenta weight, were determined. Data are mean ± standard deviation (SD). **P < .01, unpaired Student t test; not significant (ns), Mann-Whitney U test. (D) PAR2+/− and PAR2−/− embryos were collected at E13.5 from mating of PAR2+/− mother with PAR2−/− father, and the numbers of normal, pale, and dead embryos, as well as embryo weights, were determined. Data are mean ± SD. ns, unpaired Student t test. (E) We used an independently targeted line to collect PAR2+/− and PAR2−/− embryos at E13.5 to E17.5 from the mating of a PAR2+/− mother with a PAR2−/− father. Examples of PAR2+/− and PAR2−/− embryos with pale (red boxes) or midgestation lethal phenotypes shown. (F) Livers from WT adult mice, as well as fetal livers from WT embryos at E13.5 and E15.5, were collected, and the mRNA expression of coagulation factors prothrombin, FVII, and FX was normalized to r18s as a housekeeping gene. The percentage above the columns shows the relative expression of coagulation factors at each embryonic stage in comparison with adult liver measured in parallel. ****P < .0001, 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett multiple-comparisons test.

PAR2 deficiency causes a partially penetrant severe embryonic anemia. (A) WT and PAR2−/− embryos were collected between E13.5 and E15.5 from homozygous mating of WT and PAR2−/− parents, and the numbers of normal, pale, and midgestation dead embryos were determined. The number of embryos are shown for individual pregnancies. (B) The numbers of reticulocytes and nRBCs in peripheral blood were counted in 12 normal and 3 pale PAR2−/− embryos at E19.5. Blood smears were stained with Wright solution. Arrows point to nRBC in the blood from 1 of the pale embryos. (C) PAR2+/− embryos were collected at E13.5 from mating of WT or PAR2−/− mother with PAR2−/− or WT father, respectively, and the numbers of normal, pale, and dead embryos, as well as embryo and placenta weight, were determined. Data are mean ± standard deviation (SD). **P < .01, unpaired Student t test; not significant (ns), Mann-Whitney U test. (D) PAR2+/− and PAR2−/− embryos were collected at E13.5 from mating of PAR2+/− mother with PAR2−/− father, and the numbers of normal, pale, and dead embryos, as well as embryo weights, were determined. Data are mean ± SD. ns, unpaired Student t test. (E) We used an independently targeted line to collect PAR2+/− and PAR2−/− embryos at E13.5 to E17.5 from the mating of a PAR2+/− mother with a PAR2−/− father. Examples of PAR2+/− and PAR2−/− embryos with pale (red boxes) or midgestation lethal phenotypes shown. (F) Livers from WT adult mice, as well as fetal livers from WT embryos at E13.5 and E15.5, were collected, and the mRNA expression of coagulation factors prothrombin, FVII, and FX was normalized to r18s as a housekeeping gene. The percentage above the columns shows the relative expression of coagulation factors at each embryonic stage in comparison with adult liver measured in parallel. ****P < .0001, 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett multiple-comparisons test.

In contrast, anemic embryos with a pale appearance and apparently normal gestational development were observed only in PAR2−/− pregnancies at E14.5 and E15.5 (Figure 1A) (P = .0514, Fisher’s exact test). We analyzed late-gestation pregnancies (E19.5) in PAR2−/− mice and found that the peripheral blood of 3 recovered pale PAR2−/− embryos had an increase in reticulated red blood cells (RBCs) and nRBCs compared with the remaining PAR2−/− embryos from the same pregnancies (Figure 1B). During fetal hematopoiesis in the mouse, the transition from nRBC to enucleated RBC is typically completed by E17.5, although primitive nucleated erythroblasts may continue to circulate.30 Therefore, the persistence of nRBCs and reticulocytes in late gestation indicated defective hematopoiesis leading to anemia. Occasionally, we also observed live newborn mice with a pale appearance; however, such pups were typically no longer discernible the following day, indicating that the severe anemia was compatible with embryonic development but also caused perinatal lethality.

PAR2 and matriptase double-deficient embryos display midgestational lethality resulting from failure of the placental epithelial barrier.15 Therefore, we investigated whether maternal PAR2 deficiency was primarily responsible for the severe anemia (eg, by impairing placental function). We analyzed PAR2+/− heterozygous embryos at E13.5 resulting from timed mating of WT mothers with PAR2−/− fathers or of PAR2−/− mothers with WT fathers. In pregnancies developing in both maternal genotypes, 2 of 27 heterozygous embryos showed delayed development or partial resorption (Figure 1C). The remaining embryos appeared macroscopically normal without signs of anemia; however, embryo weights were significantly lower in pregnancies from PAR2−/− mothers vs WT mothers but placenta weights were not different (Figure 1C). These data suggested that isolated maternal PAR2 deficiency caused a mild developmental delay but no significant increase in embryonic lethality of PAR2-expressing embryos.

To specifically analyze the roles of embryonic PAR2 in development, we also mated PAR2+/− mothers with PAR2−/− fathers. The resulting PAR2+/− and PAR2−/− E13.5 embryos from the same pregnancies did not differ in weight (Figure 1D). However, PAR2−/− embryos were only recovered at half the expected frequency relative to PAR2+/− heterozygotes. These data indicated that embryonic PAR2 deficiency, when PAR2-expressing embryos were present in the same pregnancy, caused partial early embryonic lethality leading to full resorption of embryos prior to midgestation, as previously described on a mixed genetic background.13

We also backcrossed the mice generated by Damiano et al13 for 8 generations with C57BL/6J mice and analyzed pregnancy loss in PAR2+/− mothers with the mating scheme used above. Analysis of embryo phenotypes at E13.5 to E17.5 confirmed the underrepresentation of PAR2−/− embryos in comparison with PAR2+/− embryos (Figure 1E) (P = .0478, χ2 test). In addition, embryos with delayed midgestational development or paleness were all genotyped as PAR2 knockout in this series of pregnancy induction (P < .0001, χ2 test). Significantly more anemic PAR2-knockout embryos were found in pregnancies at E15.5 to E17.5 (Figure 1E) (P = .0095, Fisher’s exact test), consistent with findings in experiments with the separately targeted PAR2 locus shown in Figure 1A. However, there was no apparent increase in the percentage of anemic embryos from E15.5 to E17.5, suggesting that the anemia was stochastic and not progressive in late-gestational development.

The number of pregnancies analyzed in Figure 1A was too small to assess embryonic lethality of PAR2−/− embryos in comparison with WT pregnancies, but the weaning record indicated an underrepresentation of male PAR2-deficient mice. Although WT controls showed the expected sex distribution (2078/4101 males; 50.7%), male mice were underrepresented in PAR2−/− litters (731/1762 males; 41.4%) (P < .01, χ2 test) with average litter sizes of 6.42 for WT mile and 4.85 for PAR2−/− mile. These data indicated a sex bias in embryonic and perinatal lethality of PAR2−/− mice.

Embryonic PAR2 supports erythropoiesis in the fetal liver

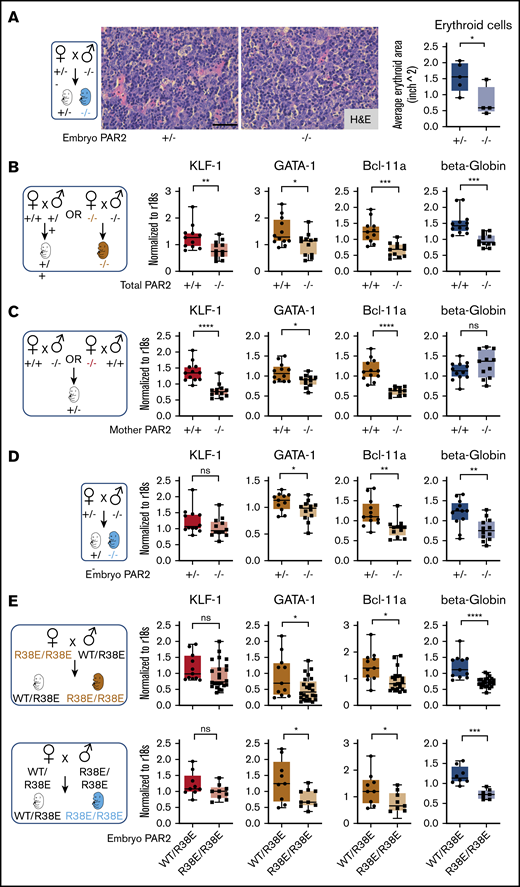

During mouse development, the site of hematopoiesis shifts from the yolk sac and aorta-gonad-mesonephros region to the fetal liver, whereas bone marrow expansion of hematopoiesis at later stages of gestation prepares the organism for postnatal life.31 The fetal liver is the active site of hematopoiesis starting at E13.5 to E15.5, with erythroid maturation and, eventually, progressive enucleation of erythrocytes in further development.32 At these stages of development, liver synthesis of PAR2-activating coagulation proteases was detectable, albeit at reduced levels compared with adult animals (Figure 1F). The differentiation of late-stage primitive erythroblasts occurs in a niche called the “erythroblastic island.” We found that erythroblastic island sizes in livers of E15.5 PAR2−/− embryos were markedly reduced compared with PAR2+/− embryos from the same pregnant mother (Figure 2A), indicating that the anemia in PAR2 deficiency was due to diminished RBC production rather than increased peripheral destruction or loss.

Embryonic PAR2 supports erythropoiesis in the fetal liver. (A) Fetal livers were collected from PAR2+/− and PAR2−/− embryos at E15.5, resulting from the mating of a PAR2+/− mother with a PAR2−/− father, and erythroid cell area was quantified on H&E-stained sections with ImageJ; scale bar, 50 µm. Each point in the graph is the average erythroid cell area from ≥8 field of views per mouse. (B-D) Fetal livers were collected at E13.5 from different timed mating strategies, and mRNA gene expression for erythroid master regulators and β-globin was normalized to r18s. Color coding indicate transcripts changed by maternal and embryonic PAR2 deficiency (beige bars), by only maternal PAR2 deletion (red bars), or by only embryonic PAR2 deletion (blue bars). (E) Expression of the indicated genes in fetal livers collected at E15.5 from WT/PAR2 R38E heterozygous embryos and from PAR2 R38E/PAR2 R38E homozygous embryos in PAR2 R38E/PAR2 R38E homozygous mothers or WT/PAR2 R38E heterozygous mothers. All data are mean ± standard deviation. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001, unpaired Student t test. Mann-Whitney U test was used for for KLF-1 (D) and Bcl-11a and KLF-1 (E, upper row).

Embryonic PAR2 supports erythropoiesis in the fetal liver. (A) Fetal livers were collected from PAR2+/− and PAR2−/− embryos at E15.5, resulting from the mating of a PAR2+/− mother with a PAR2−/− father, and erythroid cell area was quantified on H&E-stained sections with ImageJ; scale bar, 50 µm. Each point in the graph is the average erythroid cell area from ≥8 field of views per mouse. (B-D) Fetal livers were collected at E13.5 from different timed mating strategies, and mRNA gene expression for erythroid master regulators and β-globin was normalized to r18s. Color coding indicate transcripts changed by maternal and embryonic PAR2 deficiency (beige bars), by only maternal PAR2 deletion (red bars), or by only embryonic PAR2 deletion (blue bars). (E) Expression of the indicated genes in fetal livers collected at E15.5 from WT/PAR2 R38E heterozygous embryos and from PAR2 R38E/PAR2 R38E homozygous embryos in PAR2 R38E/PAR2 R38E homozygous mothers or WT/PAR2 R38E heterozygous mothers. All data are mean ± standard deviation. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001, unpaired Student t test. Mann-Whitney U test was used for for KLF-1 (D) and Bcl-11a and KLF-1 (E, upper row).

Differentiation of erythrocytes in the fetal liver is accompanied by the expression of adult β-globin and induction of erythroid master regulators, such as common erythroid transcription factors GATA-1 and KLF-1, as well as those uniquely expressed in definitive erythroid lineages (eg, BCL-11A).33 We analyzed mRNA expression of these genes in the fetal liver of embryos from different mating schemes (Figure 2B-E). In the homozygous mating with PAR2 deficiency of mother and embryo, liver transcript levels of all erythropoiesis regulators were significantly reduced in comparison with WT pregnancies (Figure 2B). In a mating scheme yielding PAR2+/− embryos, maternal PAR2 deficiency caused reduced levels of KLF-1 and other erythropoiesis regulators, but β-globin expression was not influenced by maternal PAR2 expression (Figure 2C), suggesting that the altered transcripts were sensitive to delayed embryonic development indicated by the reduced embryo weight seen with this mating scheme (Figure 1C). In contrast, in PAR2−/− embryos carried by PAR2+/− mothers, the expression of KLF-1 was unchanged, whereas the other genes, including β-globin, were also decreased in the livers of PAR2-deficient embryos relative to PAR2+/− embryos (Figure 2D), demonstrating that embryonic PAR2 directly regulated fetal erythropoiesis.

Because prior studies have demonstrated an apparent compensation of PAR1 for loss of PAR2 in embryonic development,14 we also analyzed cleavage-insensitive PAR2-R38E mice19 which support PAR1/PAR2 heterodimer signaling.34 Male mice were underrepresented in weanlings of the PAR2 R38E strain (1089 male mice of 2436; 44.7%; Chi2 P < .01), as seen for PAR2−/− mice, with average litter sizes of 5.10 for PAR2 R38E as compared with 6.42 for WT mice. Completely PAR2 cleavage-insensitive PAR2-R38E/PAR2-R38E homozygous embryos displayed lower β-globin, GATA-1, and BCL-11a expression compared with PAR2-WT/PAR2-R38E embryos with a single protease-sensitive allele from the same pregnancies (Figure 2E), in line with the results from PAR2-knockout mice. However, the reduction in KLF-1 expression seen with PAR2−/− mothers was not apparent in PAR2-R38E/PAR2-R38E homozygous embryos from PAR2 cleavage-resistant mothers, suggesting that the maternal phenotype involves PAR2 cross-activation by other PARs,35-38 GPCR scaffolding functions of PAR2, or contributions to nonproteolytic signaling pathways.39 Thus, despite some effects of maternal PAR2 deficiency, embryonic proteolytic PAR2 signaling primarily drives erythropoiesis in the mouse fetal liver.

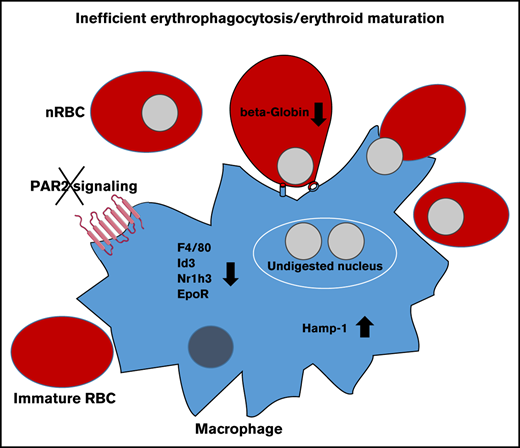

Embryonic PAR2 regulates fetal liver macrophages

Definitive erythropoiesis in the liver is orchestrated by macrophages that support the differentiation of late-stage primitive erythroblasts in the erythroblastic island. These central macrophages regulate erythroblast development by providing survival signals through cell-cell interactions and, at later stages, RBC maturation through phagocytosis of nuclei expelled from maturing nucleated erythrocytes.40,41 In line with diminished erythroid cell areas, the frequency of F4/80+ macrophages was also reduced in the fetal liver of E15.5 PAR2-deficient embryos in signaling-competent PAR2+/− mothers (Figure 3A). Reduced liver macrophage abundance was confirmed by transcript analysis in total liver RNA for Kupffer cell markers, specifically lineage-determining transcriptional regulators, Id3 and Nr1h3 (LXRa).42,43 Expression of F4/80, Id3, and Nr1h3 (LXRa) as early as E13.5 in PAR2+/− embryos was not influenced by maternal PAR2 deficiency, but it was markedly reduced in PAR2−/− vs PAR2+/− embryos (Figure 3B). Pericyte markers that are known to be expressed by hepatic stellate cells (Nestin, NG2, Pdgfrb, Cxcl12)44 were not differentially expressed (data not shown), with the exception of Mcam (CD146), which is also known to be synthesized by macrophages (Figure 3B-C).45

Embryonic PAR2 regulates fetal liver macrophages. (A) Fetal livers were collected from PAR2+/− and PAR2−/− embryos at E15.5, resulting from the mating of a PAR2+/− mother with a PAR2−/− father. Each point in the graph is the average F4/80 area from ≥8 field of views per mouse. Scale bar, 50 µm. Fetal livers were collected at E13.5 (B) and at E15.5 (C) from different timed mating strategies of PAR2 signaling–deficient mice, and mRNA gene expression for macrophage markers and regulators of apoptotic cell clearance capacity was analyzed. (D) Fetal livers were collected at E15.5 from mating of heterozygous FVII-deficient mice (WT/F7KO), and mRNA expression of FVII and macrophage differentiation markers was determined for WT (WT/WT) and FVII-deficient (F7KO/F7KO) embryos. All data are mean ± standard deviation. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001, Mann-Whitney U test for Nr1h3 (B) and Id3 (D); all other P values were calculated using the Student t test.

Embryonic PAR2 regulates fetal liver macrophages. (A) Fetal livers were collected from PAR2+/− and PAR2−/− embryos at E15.5, resulting from the mating of a PAR2+/− mother with a PAR2−/− father. Each point in the graph is the average F4/80 area from ≥8 field of views per mouse. Scale bar, 50 µm. Fetal livers were collected at E13.5 (B) and at E15.5 (C) from different timed mating strategies of PAR2 signaling–deficient mice, and mRNA gene expression for macrophage markers and regulators of apoptotic cell clearance capacity was analyzed. (D) Fetal livers were collected at E15.5 from mating of heterozygous FVII-deficient mice (WT/F7KO), and mRNA expression of FVII and macrophage differentiation markers was determined for WT (WT/WT) and FVII-deficient (F7KO/F7KO) embryos. All data are mean ± standard deviation. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001, Mann-Whitney U test for Nr1h3 (B) and Id3 (D); all other P values were calculated using the Student t test.

Nuclear receptors, including LXRa,46 have been linked to clearance of apoptotic cells by regulating the expression of engulfment receptors in macrophages (eg, the erythropoietin receptor [EpoR])47 or bridging molecules involved in phagocytosis. Expression of EpoR was also reduced in PAR2−/− embryos relative to PAR2+/− embryos, but it was not influenced by maternal PAR2 deficiency (Figure 3B). These differences were also seen in homozygous PAR2-R38E/R38E cleavage-resistant embryos relative to PAR2-WT/PAR2-R38E heterozygous embryos in the same pregnancies (Figure 3C), confirming PAR2 proteolytic signaling as the major regulator for fetal liver macrophage development.

Therefore, we asked whether coagulation proteases, which are expressed during these stages of embryonic development in the fetal liver (Figure 1F), are involved in PAR2 cleavage. FVII mRNA levels were reduced by >90% in homozygous fetal livers (Figure 3D) of mice with a mistargeted F7 allele, leading to premature stop codons in the FVII catalytic domain–coding sequence. Although early embryonic lethality of FVII-deficient embryos is rescued by maternal FVII,11 macrophage marker expression was significantly reduced in livers of mice lacking embryonic FVII expression (Figure 3D). Thus, FVIIa-PAR2 signaling is the likely driver for macrophage development in the fetal liver.

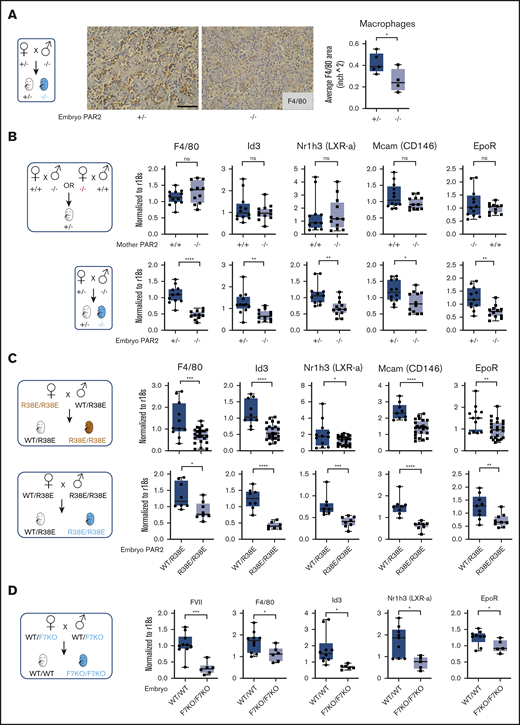

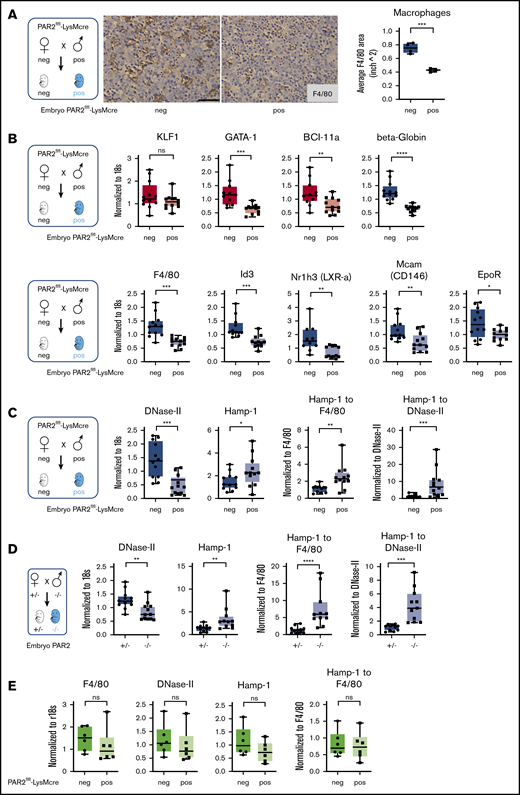

Macrophage PAR2 regulates fetal erythropoiesis

Because fetal liver macrophage markers were reduced in PAR2−/− embryos, we hypothesized that macrophage PAR2 directly regulated fetal erythropoiesis. Therefore, we evaluated embryonic development in PAR2flfl-LysMcre mice with cell type–specific deletion of PAR2 in myeloid cells, including macrophages. Macrophage PAR2-deficient fetal livers had reduced density of F4/80+ macrophages compared with PAR2flfl embryos in the same pregnancies (Figure 4A). Mirroring the findings in PAR2-deficient embryos, PAR2 deficiency in macrophages did not cause any reduction in KLF-1 expression, but erythropoiesis and macrophage markers were significantly reduced (Figure 4B).

Macrophage PAR2 regulates fetal erythropoiesis. (A) Immunohistochemistry of fetal livers collected from PAR2flfl-LysMcre and PAR2flfl control embryos at E15.5 and stained for the macrophage marker F4/80. Scale bar, 50 µm. (B) mRNA expression in fetal livers was analyzed for erythroid master regulators, β-globin, F4/80, macrophage markers, and regulators of apoptotic cell clearance capacity. Fetal livers were collected from PAR2flfl-LysMcre and PAR2flfl embryos at E15.5 (C) and from PAR2+/− and PAR2−/− embryos at E13.5 (D), and mRNA expression of DNase II and Hamp-1 was normalized to r18s. To compensate for reduced macrophage numbers, Hamp-1 expression was also normalized to F4/80, using the data depicted for the corresponding genotypes in panel B or Figure 3B or it was normalized to DNase II by calculating the expression relative to F4/80 or DNase II for each embryo. All data are mean ± standard deviation. (E) Livers were collected from 9- to 10-week-old adult female mice, and F4/80, DNase II, and Hamp-1 mRNA expression was normalized to r18s or F4/80. (A-D) *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001, Mann-Whitney U test for Id3 and Nr1h3 (B), Hamp-1 to F4/80 and Hamp-1 to DNase II (C), and Hamp-1 and Hamp-1 to F4/80 (D); all other P values were calculated using the unpaired Student t test. (E) Mann-Whitney U test for F4/80; all other P values were calculated using the unpaired Student t test. neg, negative; pos, positive.

Macrophage PAR2 regulates fetal erythropoiesis. (A) Immunohistochemistry of fetal livers collected from PAR2flfl-LysMcre and PAR2flfl control embryos at E15.5 and stained for the macrophage marker F4/80. Scale bar, 50 µm. (B) mRNA expression in fetal livers was analyzed for erythroid master regulators, β-globin, F4/80, macrophage markers, and regulators of apoptotic cell clearance capacity. Fetal livers were collected from PAR2flfl-LysMcre and PAR2flfl embryos at E15.5 (C) and from PAR2+/− and PAR2−/− embryos at E13.5 (D), and mRNA expression of DNase II and Hamp-1 was normalized to r18s. To compensate for reduced macrophage numbers, Hamp-1 expression was also normalized to F4/80, using the data depicted for the corresponding genotypes in panel B or Figure 3B or it was normalized to DNase II by calculating the expression relative to F4/80 or DNase II for each embryo. All data are mean ± standard deviation. (E) Livers were collected from 9- to 10-week-old adult female mice, and F4/80, DNase II, and Hamp-1 mRNA expression was normalized to r18s or F4/80. (A-D) *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001, Mann-Whitney U test for Id3 and Nr1h3 (B), Hamp-1 to F4/80 and Hamp-1 to DNase II (C), and Hamp-1 and Hamp-1 to F4/80 (D); all other P values were calculated using the unpaired Student t test. (E) Mann-Whitney U test for F4/80; all other P values were calculated using the unpaired Student t test. neg, negative; pos, positive.

Function of the central macrophage in erythroblastic islands is dependent on DNase II, which is important for breakdown of nuclei expelled by erythroblasts, and DNase II–deficient mice die in utero from severe anemia with complete penetrance, in contrast to the PAR2−/− phenotype.48 Impaired DNA clearance causes macrophage inflammatory activation and interferon regulated factor 3/7 (IRF3/7)-dependent induction of interferon-regulated genes, such as Hamp-1,49 and anemia of DNase II–deficient embryos is rescued by deletion of Irf3/7. Consistent with reduced macrophage numbers, DNase II expression was lower in PAR2flfl-LysMcre fetal livers relative to PAR2flfl mice from the same pregnancies (Figure 4C).

Remarkably, despite reduced macrophage numbers, Hamp-1 expression was increased. Normalization to F4/80 or to DNase II expression as a surrogate for macrophage abundance further substantiated the marked upregulation of Hamp-1 (Figure 4C). Similar results were observed in complete PAR2-deficient embryos (Figure 4D). In contrast, when erythropoiesis has shifted to the bone marrow in adult mice, expression of these marker genes for macrophage abundance and activation was unchanged in livers of mice with PAR2-deficient macrophages (Figure 4E). These data suggest that the previously demonstrated phagocytosis defect of PAR2-deficient macrophages50 may cause increased macrophage inflammatory activation, specifically during fetal erythropoiesis in mice, and contributes to the subsequent development of severe anemia in a subset of embryos. Note that the expression analysis in these fetal livers was performed on embryos that did not display any visible anemia, indicating that inflammatory stress was already detectable in partially compensated erythroblastic islands.

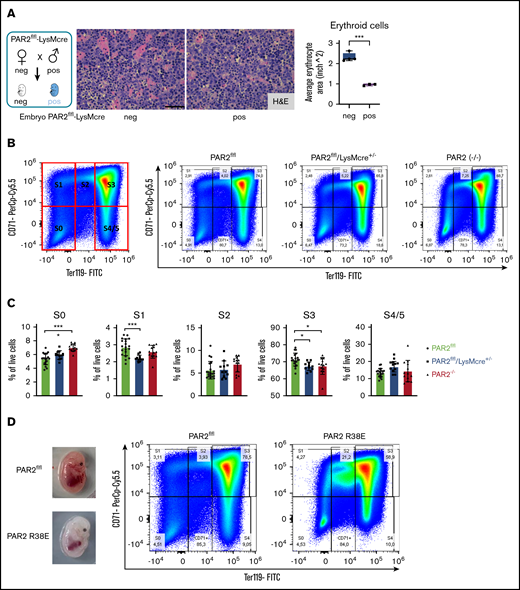

Fetal livers from macrophage PAR2-deficient mice also exhibited smaller erythroblastic islands (Figure 5A). We analyzed erythropoiesis by CD71/Ter119 staining of cell suspensions from fetal livers recovered at E15.5. Flow cytometry resolves the progressive maturation from CD71+/Ter119− erythroblasts (in gate S1) to CD71low/Ter119+ mature erythrocytes (in gates S4/S5) (Figure 5B). Livers from macrophage PAR2-deficient embryos in WT mothers and from PAR2−/− embryos in PAR2−/− mothers showed a slight relative increase in CD71−/Ter119− (S0) proerythroblasts, whereas erythroblast maturation was impaired, as indicated by reduced frequencies of cells in gates S1 and S3 (Figure 5C). Cells in these gates showed no difference in forward scatter between PAR2-deficient and WT embryos, indicating a similar cell size and suggesting that the smaller erythroblastic island areas observed in fetal liver were caused by reduced cell numbers rather than by diminished erythroblast size. None of the analyzed embryos was visibly anemic. Therefore, we screened additional pregnancies for pale embryos at E15.5. Fetal liver analysis of the depicted anemic PAR2-R38E embryo indicated that erythroblast maturation to S3 was similarly prevented with an accumulation of less mature erythroblasts in S2 (Figure 5D). Thus, macrophage PAR2 signaling regulates erythroblast maturation in the fetal liver.

Macrophage PAR2 signaling in erythroblast maturation. (A) Fetal livers were collected from PAR2flfl-LysMcre+/− and PAR2flfl control embryos at E15.5. Representative H&E staining and quantification of erythroid cell area with ImageJ are shown. Scale bar, 50 µm. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of erythrocyte differentiation in E15.5 livers from the indicated mouse strains. A representative plot of CD71/Ter119 staining is shown along with the gates used in the quantification shown in panel C. Gates were quantified for the indicated number of analyzed embryos. (D) Appearance and flow cytometry analysis of erythrocyte development in E15.5 fetal liver of a WT embryo and a PAR2 R38E embryo with pale phenotype. *P < .05, ***P < .001, ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test.

Macrophage PAR2 signaling in erythroblast maturation. (A) Fetal livers were collected from PAR2flfl-LysMcre+/− and PAR2flfl control embryos at E15.5. Representative H&E staining and quantification of erythroid cell area with ImageJ are shown. Scale bar, 50 µm. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of erythrocyte differentiation in E15.5 livers from the indicated mouse strains. A representative plot of CD71/Ter119 staining is shown along with the gates used in the quantification shown in panel C. Gates were quantified for the indicated number of analyzed embryos. (D) Appearance and flow cytometry analysis of erythrocyte development in E15.5 fetal liver of a WT embryo and a PAR2 R38E embryo with pale phenotype. *P < .05, ***P < .001, ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test.

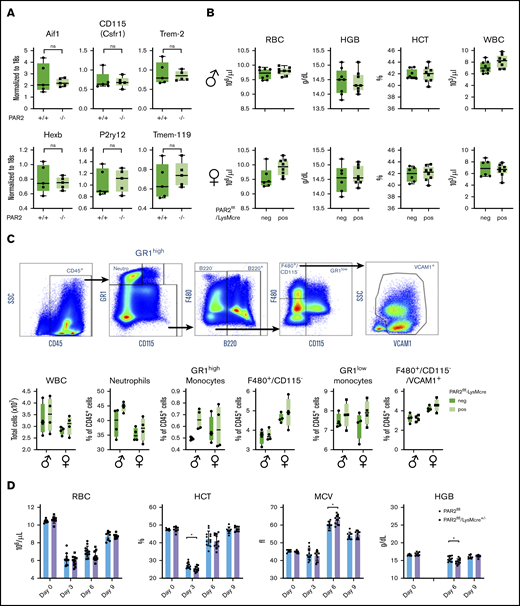

Macrophage PAR2 is dispensable for steady-state postnatal erythropoiesis

During mouse embryonic development, macrophages develop first in the yolk sac and populate the body, including the developing brain. Fetal liver–derived monocytes differentiate into macrophages, which then dilute the population of yolk sac–derived macrophages, with the exception of microglia that self-renew and are of yolk sac origin in the adult animal.51 PAR2 deficiency did not alter myeloid cell (Aif1, Csfr1, Trem2) or microglia marker (Hexb, P2ry12, Tmem-119) expression in adult brains (Figure 6A),52 indicating that PAR2 does not play a role in the development of yolk sac macrophages.

Macrophage PAR2 is dispensable for steady-state postnatal erythropoiesis. (A) Brains were collected from adult WT and PAR2−/− mice, and mRNA gene expression was analyzed for myeloid populations in brain (Aif1, Csfr1, Trem2) or for more specific microglia markers (Hexb, P2ry12, Tmem-119). (B) Peripheral blood from 11- to 12-week-old adult male and female PAR2flfl-LysMcre mice and PAR2flfl littermate control mice was collected for differential blood counting. (C) Representative fluorescence-activated cell sorting plots, gating strategy following gating on single cells, and quantification of different WBC populations in the bone marrow from 8- to 10-week-old adult male and female PAR2flfl-LysMcre mice and PAR2flfl littermate control mice. Most macrophages in the bone marrow are F480+/CD115−/VCAM1+. Using 2-way ANOVA, there was no significant differences between genotypes. (D) RBC counts, hematocrit (HCT), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), and hemoglobin levels (HGB) in male and female PAR2flfl-LysMcre mice and PAR2flfl littermate control mice challenged at days 0 and 1 with phenylhydrazine (50 mg/kg body weight). HGB levels were not analyzed at day 3 because of interference with the injected phenylhydrazine. *P < .05, unpaired Student t test.

Macrophage PAR2 is dispensable for steady-state postnatal erythropoiesis. (A) Brains were collected from adult WT and PAR2−/− mice, and mRNA gene expression was analyzed for myeloid populations in brain (Aif1, Csfr1, Trem2) or for more specific microglia markers (Hexb, P2ry12, Tmem-119). (B) Peripheral blood from 11- to 12-week-old adult male and female PAR2flfl-LysMcre mice and PAR2flfl littermate control mice was collected for differential blood counting. (C) Representative fluorescence-activated cell sorting plots, gating strategy following gating on single cells, and quantification of different WBC populations in the bone marrow from 8- to 10-week-old adult male and female PAR2flfl-LysMcre mice and PAR2flfl littermate control mice. Most macrophages in the bone marrow are F480+/CD115−/VCAM1+. Using 2-way ANOVA, there was no significant differences between genotypes. (D) RBC counts, hematocrit (HCT), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), and hemoglobin levels (HGB) in male and female PAR2flfl-LysMcre mice and PAR2flfl littermate control mice challenged at days 0 and 1 with phenylhydrazine (50 mg/kg body weight). HGB levels were not analyzed at day 3 because of interference with the injected phenylhydrazine. *P < .05, unpaired Student t test.

We next asked whether macrophage PAR2 plays a role in postnatal erythropoiesis. In 11- to 12-week-old mice of either sex, RBC counts, hemoglobin, hematocrit, and white blood cell (WBC) levels were indistinguishable between mice with macrophage PAR2 deficiency and control mice (Figure 6B), indicating that macrophage PAR2 was specifically required for definitive hematopoiesis in the liver during midgestation. Because postnatal hematopoiesis is primarily orchestrated by macrophages in the bone marrow, we characterized bone marrow macrophages supporting erythroblast islands based on the expression of F4/80 and VCAM-1.53 Total WBC counts and the abundance of monocytes, neutrophils, and bone marrow macrophages were not different between PAR2flfl-LysMcre mice and littermate control female or male PAR2flfl mice (Figure 6C). Thus, the fetal macrophage defect in PAR2-deficient mice did not persist into adulthood with steady-state erythropoiesis.

Acute hemolysis requires rapid de novo production of RBCs. To study postnatal erythropoiesis under stress conditions, we induced acute anemia by 2 injections of phenylhydrazine on consecutive days in PAR2flfl-LysMcre+/− mice and littermate PAR2flfl mice. Mice with macrophage PAR2 deficiency showed a reduced hematocrit 3 days after the induction of hemolysis, as well as reduced hemoglobin levels 6 days after (Figure 6D). These data indicated that macrophage PAR2 was dispensable for steady-state erythropoiesis but that it contributed during embryonic development, as well as during hemolytic stress in adult animals.

Discussion

Deficiencies in coagulation factors and PARs affect mouse embryonic development, but phenotypes of single PAR deficiencies are often obscured by the compensation by other receptors. Although most PAR1/PAR2 double-deficient embryos do not survive to birth,14 PAR2 single-deficient embryos exhibit an unresolved partial preterm lethality.13 We show in this article, using independently targeted PAR2 signaling-deficient mice, that embryonic PAR2 deficiency causes early embryonic lethality, as documented for PAR1−/− mice, as well as impairs erythropoiesis, leading to severe anemia and fetal death with variable penetrance. Furthermore, we show that macrophage autonomous PAR2 signaling causes this impairment of definitive hematopoiesis during the rapid adaptive changes associated with prenatal fetal development.

Anemia can be caused by peripheral consumption of RBCs in hemolytic diseases. Our data show that maternal PAR2 deficiency reduces embryo weights and, concordantly, the expression of erythroid master regulators, such as KLF-1, GATA-1, and BCL-11A, in the fetal liver. However, embryonic PAR2 deficiency alone also reduced GATA-1 and BCL-11A expression, together with β-globin and markers of Kupffer cell specification and identity.42,43 These markers were not influenced by maternal PAR2 deficiency alone. Based on these data, we conclude that PAR2 deficiency in macrophages primarily impaired erythropoiesis, rather than increased RBC consumption during fetal development. These differences were also seen in homozygous PAR2 R38E cleavage-resistant embryos relative to PAR2 R38E/WT heterozygous embryos, confirming that PAR2 proteolytic signaling is the major regulator of fetal hematopoiesis.

Cell type–specific deletion of PAR2 in the embryo demonstrated that myeloid cell expression of PAR2 was required for normal macrophage numbers in the fetal liver. One possible role for PAR2 is to support Kupffer cell development. PAR2 promotes cancer cell migration,23 as well as stimulates migration of neutrophils,54 dendritic cells,55 and microglia.56 During terminal events in erythrocyte differentiation in erythroblastic islands, fetal liver macrophages interact with erythroblasts via several adherence proteins and engulf extruded erythrocyte nuclei.53,57,58 Because PAR2 inactivation leads to decreased phagocytosis and bacterial clearance,50 the more likely function of fetal liver macrophage PAR2 is to aid in the removal of extruded erythroid nuclei. A failure to efficiently clear nuclei, such as seen in DNase II–knockout mice, also causes severe anemia and fetal death.48

The clearance of apoptotic cells and nuclei by macrophages occurs in a coordinated manner to ensure tissue homeostasis. Therefore, engulfment is linked to anti-inflammatory signaling to avoid undesirable immune reactions. The nuclear receptor LXRα plays an important role in such anti-inflammatory signaling, as does the upregulation of so-called “eat me” signals (eg, the EpoR that supports phagocytosis). Reduced numbers of liver macrophages in PAR2-deficient mice were associated with reduced expression of engulfment genes in the fetal liver. Conversely, impaired DNA clearance causes macrophage inflammatory activation through IRF3 and IRF7 signaling.49 In striking similarity to DNase II–deficient mice, we find that interferon-regulated Hamp-1 is increased in the liver of animals with macrophage PAR2 deficiency, despite reduced macrophage numbers. The deregulated fetal liver macrophage interferon signaling is in line with established roles of coagulation protease activation of PAR2 as a crucial component of the lipopolysaccharide-induced interferon response in myeloid cells.19

However, macrophage PAR2 proteolytic signaling is not required for primitive macrophage development giving rise to microglia or for postnatal bone marrow erythropoiesis and Kupffer cell abundance, which is in contrast to its significant role during definitive hematopoiesis and erythropoiesis in the fetal liver. Distinct differences in protease milieus between the bone marrow niche1 and the fetal liver may contribute to the nonessential role in postnatal erythropoiesis, at least under steady-state conditions. In contrast, under stress conditions in adult animals, PAR2 deficiency in macrophages causes measurable impairments in erythropoiesis, suggesting that PAR2 activation in macrophages is particularly important under stress conditions in fetal and postnatal environments.

Our data from mice with macrophage PAR2 deficiency add to the growing evidence that PAR2 participates in macrophage and myeloid cell activation. PAR2 modulates macrophage alternative activation in the context of TLR signaling59 and plays a specific role in the interferon response downstream of TLR4 signaling.19 This process is specifically regulated by coagulation factors,60 and innate immune PAR2 signaling regulates inflammation associated with cardio-metabolic disorders,61-64 as well as tumor immune evasion.22 The demonstrated deregulated inflammatory signaling of PAR2-deficient macrophages in the fetal erythroblastic island may indicate an unrecognized role for PAR2 in linking inflammation and erythropoiesis, which is of potential importance for adult hematopoiesis under stress conditions, aging, or in pathological conditions with aberrant erythropoiesis.

Data sharing requests should be sent to Wolfram Ruf (e-mail: ruf@scripps.edu or ruf@uni-mainz.de).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NIH HL60742) (W.R.), the Humboldt Foundation of Germany (W.R.), and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (CRC1292). M.S. was supported by a Virchow Fellowship from the Center of Thrombosis and Hemostasis (Mainz, Germany), which is funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF 01EO1003 and BMBF 01EO1503).

Authorship

Contribution: M.S. designed, performed, and analyzed experiments and wrote the manuscript; Y.K.L., K.G., T.S.N., M.K., S.D., C.D.S.R., H.W., and S.R. performed experiments and analyzed data; and W.R. conceptualized and supervised the study, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Wolfram Ruf, Center for Thrombosis and Hemostasis, Johannes Gutenberg University Medical Center, Langenbeckstr 1, 55131 Mainz, Germany; e-mail: ruf@scripps.edu or ruf@uni-mainz.de.