Key Points

Hospice utilization is suboptimal in patients with hematologic malignancies.

Hospice utilization is associated with improved end-of-life care quality outcomes in Medicare beneficiaries with hematologic malignancies.

Abstract

Patients with hematologic malignancies are thought to receive more aggressive end-of-life (EOL) care and have suboptimal hospice use compared with patients with solid tumors, but descriptions of EOL outcomes from comprehensive cohorts have been lacking. We used the population-based Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results–Medicare dataset to describe hospice use and indicators of aggressive EOL care among Medicare beneficiaries who died of hematologic malignancies in 2008-2015. Overall, 56.5% of decedents used hospice services for median 9 days (interquartile range, 3-27), 33.0% died in an acute hospital setting, 36.8% had an intensive care unit (ICU) admission in the last 30 days of life, and 13.3% received chemotherapy within the last 14 days of life. Hospice use was associated with 96% lower probability of inpatient death (adjusted risk ratio [aRR], 0.038; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.035-0.042), 44% lower probability of an ICU stay in the last 30 days of life (aRR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.54-0.57), and 62% decrease in chemotherapy use in the last 14 days of life (aRR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.35-0.41). Hospice enrollees spent on average 41% fewer days as inpatient during the last month of life (adjusted means ratio, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.57-0.60) and had 38% lower mean Medicare spending in the last month of life (adjusted means ratio, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.61-0.64). These associations were consistent across histologic subgroups. In conclusion, EOL care quality outcomes and hospice enrollment were suboptimal among older decedents with hematologic cancers, but hospice use was associated with a consistent decrease in aggressive care at EOL.

Introduction

The benefits of hospice care at the end of life (EOL) are well established in patients with solid organ malignancies. Hospice care at EOL in these patients has been shown to improve quality of life for patients and families, as well as family perceptions of quality EOL care.1,2 Timely referral to hospice and avoidance of aggressive care at the EOL are set forth as quality standards by the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the National Quality Forum (NQF).3,4 Key care quality measures as delineated by the NQF in 2016 include (1) avoidance of intensive care unit (ICU) admission in the last 30 days of life, (2) avoidance of chemotherapy administration in the last 14 days of life, and (3) avoidance of death in an acute care hospital, which is a preference expressed by a majority of people with cancer and their families.4-7

EOL care quality outcomes have been described less extensively in patients with hematologic malignancies. Data suggest that patients with hematologic malignancies receive more aggressive and, therefore, suboptimal EOL care compared with patients with advanced solid tumor malignancies. In particular, lower rates of hospice enrollment, fewer days on hospice, and higher rates of chemotherapy at the EOL have been observed among patients with hematologic malignancies.8-10 Potential barriers to quality EOL care and timely hospice referral in patients with hematologic malignancies include transfusion dependence, the potential for “cure” despite advanced disease, uncertainty regarding prognosis, and concerns about affecting patients’ hope.11-13

Furthermore, many clinicians articulate a perception that hospice may not meet the needs of patients with blood cancers.14 This perception stems from the idea that these patients have a unique symptom burden, a greater need for ongoing frequent clinic visits, and may derive palliative benefits from transfusion support at EOL that is practically precluded by hospice enrollment.12,15-19 Moreover, there is debate among hematologists about whether established EOL care quality measures are applicable to patients with hematologic malignancies.13 Treatment of leukemias and lymphomas often leads to profound cytopenias and a risk for sudden hemorrhage and infections, which often cannot be managed in the ambulatory setting, leading to a high likelihood of hospital or ICU admissions. Nevertheless, the NQF and American Society of Clinical Oncology do not differentiate EOL care quality measures for patients with different solid or hematologic malignancies. It remains uncertain whether hospice care at EOL is associated with a similar degree of improvement in EOL care quality in hematologic malignancies as it yields for patients with solid tumors.

Prior work demonstrates that indicators of EOL care quality can be derived from administrative Medicare claims, but these data have primarily been analyzed in the context of solid tumors.20,21 We sought to describe EOL care quality measures among decedents with hematologic malignancies who did or did not use hospice services. Our objective was also to determine whether the use of hospice and patterns of EOL care differ among different hematologic malignancies (eg, acute leukemia, myeloma, or lymphoma), which can vary in their clinical course and symptomatology in the terminal phase. We hypothesized that claims-based indicators of EOL care quality would be improved for patients with hematologic malignancies using hospice services, regardless of specific histology.

Methods

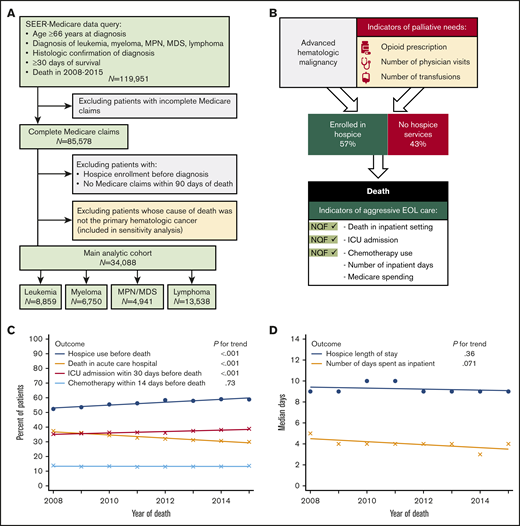

This study used deidentified data and was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board at Rhode Island Hospital. Using the population-based linked Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare registry, we selected fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries with acute or chronic leukemias, multiple myeloma, myeloproliferative neoplasms, myelodysplastic syndrome, and all subtypes of lymphoma who were diagnosed at age 66 years or older, who died between 2008 and 2015 with a cause of death ascribed to the hematologic malignancy, and who had ≥30 days of observed survival since diagnosis (Figure 1A). The SEER-Medicare program links cancer registry data from 18 geographical regions of the United States, covering ∼30% of the country’s population, to all inpatient and outpatient health services billed to Medicare, the principal source of health insurance for persons in the United States aged 65 years or older.22 The data set has been used extensively for the evaluation of patterns of care, including EOL care, among Medicare beneficiaries.12,20,21,23-27 We excluded patients who were enrolled in hospice prior to the diagnosis of their hematologic malignancy and those who did not have any evidence of health services billed to Medicare within 90 days of death. Using Medicare hospice enrollment files, we identified patients who used hospice services at any point before death. We also constructed claims-based indicators of high palliative needs: use of opioids, use of transfusions, and number of days with physician visits (using codes for office visits). These constructs (Figure 2B) were determined using claims within 30 days before hospice enrollment for those who used hospice services and within 30 days before death for decedents not enrolled in hospice, as previously described.12

Characteristics of Medicare beneficiary decedents with hematologic malignancies included in the study. (A) Cohort selection for analysis; the main analysis was conducted in the population of beneficiaries whose death was ascribed to their hematologic malignancy on the death certificate, but a sensitivity analysis confirmed findings in the entire population, regardless of reported cause of death. (B) Diagram showing claims-based covariates (indicators of palliative care needs ascertained within 30 days before hospice enrollment for hospice enrollees or before death for nonenrollees) and EOL outcomes (indicators of aggressive EOL care), including 3 NQF EOL care quality indicators. (C) Trends in the proportions of decedents with hematologic malignancies using hospice, dying in the acute care hospital, having an ICU admission, or receiving chemotherapy at EOL. (D) Linearized trends in median hospice LOS and in median number of days spent in the inpatient setting (within the last 30 days of life). P values for trends were derived from univariate robust Poisson models. MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasm.

Characteristics of Medicare beneficiary decedents with hematologic malignancies included in the study. (A) Cohort selection for analysis; the main analysis was conducted in the population of beneficiaries whose death was ascribed to their hematologic malignancy on the death certificate, but a sensitivity analysis confirmed findings in the entire population, regardless of reported cause of death. (B) Diagram showing claims-based covariates (indicators of palliative care needs ascertained within 30 days before hospice enrollment for hospice enrollees or before death for nonenrollees) and EOL outcomes (indicators of aggressive EOL care), including 3 NQF EOL care quality indicators. (C) Trends in the proportions of decedents with hematologic malignancies using hospice, dying in the acute care hospital, having an ICU admission, or receiving chemotherapy at EOL. (D) Linearized trends in median hospice LOS and in median number of days spent in the inpatient setting (within the last 30 days of life). P values for trends were derived from univariate robust Poisson models. MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasm.

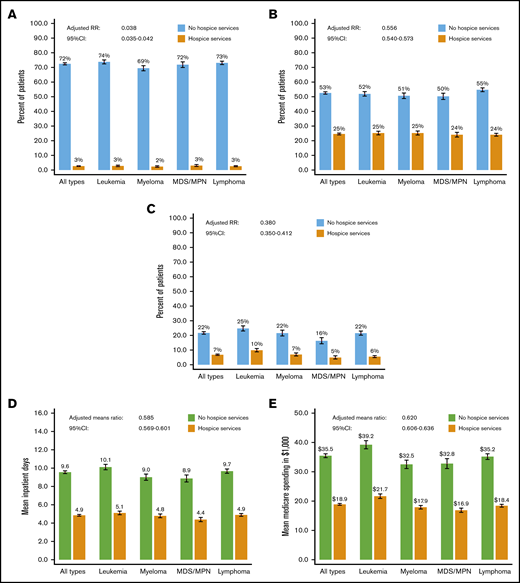

EOL care quality outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries with hematologic malignancies across major histology groups, stratified by hospice use. Proportion of patients dying in the acute care hospital (A), having an ICU admission in the last 30 days of life (B), or receiving chemotherapy in the last 14 days of life (C). (D) Mean number of days spent as an inpatient in the last 30 days of life. (E) Mean cumulative Medicare spending in the last 30 days of life. Vertical error bars represent 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Adjusted risk ratios (RR) and means ratios are from multivariable models in the aggregate cohort of all histologies, adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, comorbidities, performance status, survival from diagnosis, and temporal trends.

EOL care quality outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries with hematologic malignancies across major histology groups, stratified by hospice use. Proportion of patients dying in the acute care hospital (A), having an ICU admission in the last 30 days of life (B), or receiving chemotherapy in the last 14 days of life (C). (D) Mean number of days spent as an inpatient in the last 30 days of life. (E) Mean cumulative Medicare spending in the last 30 days of life. Vertical error bars represent 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Adjusted risk ratios (RR) and means ratios are from multivariable models in the aggregate cohort of all histologies, adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, comorbidities, performance status, survival from diagnosis, and temporal trends.

From inpatient and outpatient Medicare claims, we then ascertained 3 previously described indicators of aggressive EOL care: death in an acute care hospital, ICU admission in the last 30 days of life, and chemotherapy administration in the last 14 days of life (Figure 2B). We also calculated the number of days spent on hospice (referred to as “hospice length of stay [LOS]”), the number of days spent in the acute hospital in the last 30 days of life, and Medicare spending on medical services in the last 30 days of life. To account for the increasing role of oral targeted agents in hematologic malignancies, the use of chemotherapy was observed only among beneficiaries with Medicare Part D coverage for ≥3 months before death. Administration of therapy was determined using a combination of previously described diagnosis and procedure codes, according to the International Classification of Diseases 9-Clinical Modification, the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System, and prescription events.12,28,29 Although we focused on decedents whose death was attributed to the hematologic malignancy, because attributions on death certificates are of uncertain accuracy, we also performed a confirmatory sensitivity analysis including patients with any cause of death.30

Most factors leading to hospice enrollment are clinical events (disease progression, patient refusal of further cancer-directed therapy) that are not observable in the data; as such, we did not conduct any multivariable modeling of factors associated with the use of hospice services. To examine the association between the use of hospice services before death and indicators of EOL care quality, we compared binary outcomes in multivariable hierarchical robust Poisson models (reporting relative risk [RR]), count outcomes in negative binomial models, and mean costs in a log-γ model.31 All estimates are reported with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Models were adjusted for histology (leukemia, myeloma, myelodysplastic syndrome [MDS]/myeloproliferative neoplasm [MPN], or lymphoma), age, sex, race, marital status, Medicaid coinsurance (indicator of low socioeconomic status), prevalent poverty in the county of residence, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) comorbidity index (a version of the Charlson comorbidity index that is derived from Medicare claims),32 prior diagnosis of dementia, Davidoff’s claims-based indicator of poor performance status,33 calendar year, and survival from diagnosis (stratified as 0-6, 6-12, 12-24, and >24 months; proxy for disease aggressiveness). Additionally, we accounted for regional variation in hospice use by using a random intercept for the NCI health services area of the patient’s residence. Indicators of comorbidity or poor performance status were established using claims from 12 months prior to death. Costs were inflation adjusted to 2017 dollars using the personal consumption expenditures health-by-function price index.34

Results

Among 34 088 Medicare decedents with hematologic malignancies, 8859 had leukemia (26.0%), 6750 had myeloma (19.8%), 4941 had MDS/MPN (14.5%), and 13 538 had lymphoma (39.7%). Overall, 19 267 (56.5%) used hospice services before death. Median age at the time of death for hospice enrollees was 80 years, which was higher than for nonenrollees (77 years) (Table 1). Use of hospice services was associated with sociodemographic variables as well: it was less frequent among men, nonwhite beneficiaries, dual eligibles with Medicaid coinsurance, and those living in areas of higher prevalent poverty (P < .0001). Hospice enrollment was more frequent among patients with poor performance status, prior dementia, and survival >6 months from diagnosis, whereas the average comorbidity index was lower for hospice enrollees than for nonenrollees (P < .0001).

Patient characteristics and proportions receiving hospice services before death

| Variable* . | No hospice (n = 14 821) . | Hospice (n = 19 267) . | Total (N = 34 088) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histology, n (%) | |||||

| Leukemia | 4 148 (46.8) | 4 711 (53.2) | 8 859 | ||

| Myeloma | 2 739 (40.6) | 4 011 (59.4) | 6 750 | ||

| MDS/MPN | 2 146 (43.4) | 2 795 (56.6) | 4 941 | ||

| Lymphoma | 5 788 (42.8) | 7 750 (57.2) | 13 538 | ||

| Age at time of death, median (IQR), y | 77 (72-84) | 80 (75-86) | 79 (73-85) | ||

| Sex, n (%) | |||||

| Females | 6 294 (40.0) | 9 446 (60.0) | 15 740 | ||

| Males | 8 527 (46.5) | 9 821 (53.5) | 18 348 | ||

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||||

| White non-Hispanic | 11 164 (40.8) | 16 210 (59.2) | 27 374 | ||

| White Hispanic | 1 177 (52.1) | 1 083 (47.9) | 2 260 | ||

| African American | 1 258 (51.1) | 1 206 (48.9) | 2 464 | ||

| Asian/other | 1 222 (61.4) | 768 (38.6) | 1 990 | ||

| Marital status, n (%) | |||||

| Married | 8 110 (45.0) | 9 894 (55.0) | 18 004 | ||

| Not married | 6 711 (41.7) | 9 373 (58.3) | 16 084 | ||

| Medicaid coinsurance, n (%) | |||||

| No | 11 589 (41.5) | 16 345 (58.5) | 27 934 | ||

| Yes | 3 232 (52.5) | 2 922 (47.5) | 6 154 | ||

| Poverty prevalence†, n (%) | |||||

| 0 to <5 | 3 528 (42.3) | 4 808 (57.7) | 8 336 | ||

| 5 to <10 | 3 974 (42.6) | 5 355 (57.4) | 9 329 | ||

| 10 to <20 | 4 152 (43.1) | 5 478 (56.9) | 9 630 | ||

| 20 to 100 | 3 028 (46.9) | 3 431 (53.1) | 6 459 | ||

| Unknown | 139 (41.6) | 195 (58.4) | 334 | ||

| Any prior chemotherapy‡, n (%) | |||||

| No | 2 747 (38.3) | 4 421 (61.7) | 7 168 | ||

| Yes | 5 975 (46.4) | 6 912 (53.6) | 12 887 | ||

| Performance status, n (%) | |||||

| Not poor | 11 653 (51.1) | 11 164 (48.9) | 22 817 | ||

| Poor | 3 168 (28.1) | 8 103 (71.9) | 11 271 | ||

| Dementia, n (%) | |||||

| No | 14 005 (44.1) | 17 763 (55.9) | 31 768 | ||

| Yes | 816 (35.2) | 1 504 (64.8) | 2 320 | ||

| NCI comorbidity index, median (IQR) | 2.9 (1.3-4.7) | 2.4 (1.1-4.4) | 2.7 (1.3-4.6) | ||

| Survival from diagnosis, mo, n (%) | |||||

| ≤6 | 4 642 (47.7) | 5 083 (52.3) | 9 725 | ||

| 6-12 | 1 917 (43.3) | 2 509 (56.7) | 4 426 | ||

| 12-24 | 2 085 (41.1) | 2 993 (58.9) | 5 078 | ||

| >24 | 6 177 (41.6) | 8 682 (58.4) | 14 859 |

| Variable* . | No hospice (n = 14 821) . | Hospice (n = 19 267) . | Total (N = 34 088) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histology, n (%) | |||||

| Leukemia | 4 148 (46.8) | 4 711 (53.2) | 8 859 | ||

| Myeloma | 2 739 (40.6) | 4 011 (59.4) | 6 750 | ||

| MDS/MPN | 2 146 (43.4) | 2 795 (56.6) | 4 941 | ||

| Lymphoma | 5 788 (42.8) | 7 750 (57.2) | 13 538 | ||

| Age at time of death, median (IQR), y | 77 (72-84) | 80 (75-86) | 79 (73-85) | ||

| Sex, n (%) | |||||

| Females | 6 294 (40.0) | 9 446 (60.0) | 15 740 | ||

| Males | 8 527 (46.5) | 9 821 (53.5) | 18 348 | ||

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||||

| White non-Hispanic | 11 164 (40.8) | 16 210 (59.2) | 27 374 | ||

| White Hispanic | 1 177 (52.1) | 1 083 (47.9) | 2 260 | ||

| African American | 1 258 (51.1) | 1 206 (48.9) | 2 464 | ||

| Asian/other | 1 222 (61.4) | 768 (38.6) | 1 990 | ||

| Marital status, n (%) | |||||

| Married | 8 110 (45.0) | 9 894 (55.0) | 18 004 | ||

| Not married | 6 711 (41.7) | 9 373 (58.3) | 16 084 | ||

| Medicaid coinsurance, n (%) | |||||

| No | 11 589 (41.5) | 16 345 (58.5) | 27 934 | ||

| Yes | 3 232 (52.5) | 2 922 (47.5) | 6 154 | ||

| Poverty prevalence†, n (%) | |||||

| 0 to <5 | 3 528 (42.3) | 4 808 (57.7) | 8 336 | ||

| 5 to <10 | 3 974 (42.6) | 5 355 (57.4) | 9 329 | ||

| 10 to <20 | 4 152 (43.1) | 5 478 (56.9) | 9 630 | ||

| 20 to 100 | 3 028 (46.9) | 3 431 (53.1) | 6 459 | ||

| Unknown | 139 (41.6) | 195 (58.4) | 334 | ||

| Any prior chemotherapy‡, n (%) | |||||

| No | 2 747 (38.3) | 4 421 (61.7) | 7 168 | ||

| Yes | 5 975 (46.4) | 6 912 (53.6) | 12 887 | ||

| Performance status, n (%) | |||||

| Not poor | 11 653 (51.1) | 11 164 (48.9) | 22 817 | ||

| Poor | 3 168 (28.1) | 8 103 (71.9) | 11 271 | ||

| Dementia, n (%) | |||||

| No | 14 005 (44.1) | 17 763 (55.9) | 31 768 | ||

| Yes | 816 (35.2) | 1 504 (64.8) | 2 320 | ||

| NCI comorbidity index, median (IQR) | 2.9 (1.3-4.7) | 2.4 (1.1-4.4) | 2.7 (1.3-4.6) | ||

| Survival from diagnosis, mo, n (%) | |||||

| ≤6 | 4 642 (47.7) | 5 083 (52.3) | 9 725 | ||

| 6-12 | 1 917 (43.3) | 2 509 (56.7) | 4 426 | ||

| 12-24 | 2 085 (41.1) | 2 993 (58.9) | 5 078 | ||

| >24 | 6 177 (41.6) | 8 682 (58.4) | 14 859 |

IQR, interquartile range.

Percentages are by row, indicating the proportion of patients in each category receiving hospice services.

Individuals with income less than the federal poverty level in the county of residence.

Within 1 year prior to death, ascertained only for beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Part D (n = 20 055).

Only 64% of this older population of beneficiaries with hematologic cancers had a record of receiving any chemotherapy within 1 year before death, and this proportion was lower among hospice enrollees (61.0% vs 68.5%; P < .001). Use of hospice services was significantly associated with indicators of higher palliative needs, including prescriptions for opioids (adjusted RR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.34-1.47), administration of blood transfusions (adjusted RR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.26-1.38), and mean number of physician visits (adjusted means ratio, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.18-1.24) within 30 days before hospice enrollment or death (supplemental Figure 1).

Among histologies, we observed the expected distribution of baseline sociodemographic characteristics, with predominance of men in all categories and a relatively high (14.7%) proportion of black patients with myeloma (Table 2). Receipt of chemotherapy within 1 year before death was highest in myeloma (75.0%) and lowest in MDS/MPN (56.2%). The frequency of hospice enrollment was similar across the histologies, as was median hospice LOS (9 days; interquartile range [IQR], 3-27), with 26.7% of hospice enrollees entering hospice within 3 days before death. Median time from diagnosis to hospice enrollment was 18 months (IQR, 4-50), and ranged from 10 months (IQR, 2-42) in leukemia to 28 months (IQR, 9-59) in myeloma. Overall, 33.0% of patients died in an acute hospital setting, 36.8% had an ICU admission in the last 30 days of life, and 13.3% received chemotherapy within the last 14 days of life. The proportion dying in the inpatient setting was highest in leukemias (36.0%) and lowest in myeloma (29.6%), whereas the proportion of patients admitted to the ICU was similar between histologies (36-37%). We observed a significant increase in the proportion of beneficiaries enrolled in hospice before death between 2008 and 2015 (P < .001), and a significant decrease in the proportion dying in the acute care hospital (P < .001; Figure 1C). However, there also was a significant increase in patients with ICU admissions at the EOL (P < .001) but no significant change in the proportion receiving chemotherapy at the EOL, in the hospice LOS, or in the median number of days spent in the hospital during the last month of life (Figure 1D). These trends were generally consistent across histologies, although we observed a significant increase in the use of chemotherapy at EOL in myeloma (P < .001) and a decreased hospice LOS in leukemia and myeloma (supplemental Figure 2).

Patient demographics and EOL outcomes, stratified by type of hematologic malignancy

| Variable . | All patients (N = 34 088) . | Leukemia (n = 8859) . | Myeloma (n = 6750) . | MDS/MPN (n = 4941) . | Lymphoma (n = 13 538) . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age at time of death (IQR), y | 79 (73-85) | 79 (73-85) | 77 (72-84) | 81 (75-87) | 79 (74-86) | |||||

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Females | 15 740 (46.2) | 3918 (44.2) | 3179 (47.1) | 2043 (41.3) | 6 600 (48.8) | |||||

| Males | 18 348 (53.8) | 4941 (55.8) | 3571 (52.9) | 2898 (58.7) | 6 938 (51.2) | |||||

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||||||

| White non-Hispanic | 27 374 (80.3) | 7282 (82.2) | 4943 (73.2) | 4157 (84.1) | 10 992 (81.2) | |||||

| White Hispanic | 2 260 (6.6) | 510 (5.8) | 458 (6.8) | 242 (4.9) | 1 050 (7.8) | |||||

| African American | 2 464 (7.2) | 564 (6.4) | 991 (14.7) | 257 (5.2) | 652 (4.8) | |||||

| Asian/other | 1 990 (5.8) | 503 (5.7) | 358 (5.3) | 285 (5.8) | 844 (6.2) | |||||

| Any prior chemotherapy,* n (%) | ||||||||||

| No | 7 168 (35.7) | 1891 (36.6) | 1039 (25.0) | 1238 (43.8) | 3 000 (37.9) | |||||

| Yes | 12 887 (64.3) | 3271 (63.4) | 3116 (75.0) | 1589 (56.2) | 4 911 (62.1) | |||||

| EOL outcomes, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Hospice use | 19 267 (56.5) | 4711 (53.2) | 4011 (59.4) | 2795 (56.6) | 7 750 (57.2) | |||||

| ≤3 d on hospice | 5 139 (26.7) | 1373 (29.1) | 1022 (25.5) | 819 (29.3) | 1 925 (24.8) | |||||

| Inpatient death | 11 254 (33.0) | 3193 (36.0) | 1998 (29.6) | 1628 (32.9) | 4 435 (32.8) | |||||

| ICU admission within 30 d | 12 535 (36.8) | 3345 (37.8) | 2401 (35.6) | 1752 (35.5) | 5 037 (37.2) | |||||

| Chemotherapy within 14 d | 2 663 (13.3) | 871 (16.9) | 534 (12.9) | 280 (9.9) | 978 (12.4) | |||||

| Hospice LOS, median (IQR), d | 9 (3-27) | 9 (3-24) | 9 (3-27) | 9 (3-25) | 10 (4-29) |

| Variable . | All patients (N = 34 088) . | Leukemia (n = 8859) . | Myeloma (n = 6750) . | MDS/MPN (n = 4941) . | Lymphoma (n = 13 538) . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age at time of death (IQR), y | 79 (73-85) | 79 (73-85) | 77 (72-84) | 81 (75-87) | 79 (74-86) | |||||

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Females | 15 740 (46.2) | 3918 (44.2) | 3179 (47.1) | 2043 (41.3) | 6 600 (48.8) | |||||

| Males | 18 348 (53.8) | 4941 (55.8) | 3571 (52.9) | 2898 (58.7) | 6 938 (51.2) | |||||

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||||||

| White non-Hispanic | 27 374 (80.3) | 7282 (82.2) | 4943 (73.2) | 4157 (84.1) | 10 992 (81.2) | |||||

| White Hispanic | 2 260 (6.6) | 510 (5.8) | 458 (6.8) | 242 (4.9) | 1 050 (7.8) | |||||

| African American | 2 464 (7.2) | 564 (6.4) | 991 (14.7) | 257 (5.2) | 652 (4.8) | |||||

| Asian/other | 1 990 (5.8) | 503 (5.7) | 358 (5.3) | 285 (5.8) | 844 (6.2) | |||||

| Any prior chemotherapy,* n (%) | ||||||||||

| No | 7 168 (35.7) | 1891 (36.6) | 1039 (25.0) | 1238 (43.8) | 3 000 (37.9) | |||||

| Yes | 12 887 (64.3) | 3271 (63.4) | 3116 (75.0) | 1589 (56.2) | 4 911 (62.1) | |||||

| EOL outcomes, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Hospice use | 19 267 (56.5) | 4711 (53.2) | 4011 (59.4) | 2795 (56.6) | 7 750 (57.2) | |||||

| ≤3 d on hospice | 5 139 (26.7) | 1373 (29.1) | 1022 (25.5) | 819 (29.3) | 1 925 (24.8) | |||||

| Inpatient death | 11 254 (33.0) | 3193 (36.0) | 1998 (29.6) | 1628 (32.9) | 4 435 (32.8) | |||||

| ICU admission within 30 d | 12 535 (36.8) | 3345 (37.8) | 2401 (35.6) | 1752 (35.5) | 5 037 (37.2) | |||||

| Chemotherapy within 14 d | 2 663 (13.3) | 871 (16.9) | 534 (12.9) | 280 (9.9) | 978 (12.4) | |||||

| Hospice LOS, median (IQR), d | 9 (3-27) | 9 (3-24) | 9 (3-27) | 9 (3-25) | 10 (4-29) |

Within 1 year prior to death; ascertained only for beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Part D.

The measures of EOL care differed between hospice enrollees and nonenrollees, with hospice enrollees being consistently less likely to receive aggressive modalities of care at the EOL (Figure 2A-C). In multivariable models adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, comorbidities, performance status, survival time from diagnosis, and temporal trends, the use of hospice services was associated with a 96% decrease in the probability of inpatient death (adjusted RR, 0.038; 95% CI, 0.035-0.042), a 44% decrease in the probability of an ICU stay in the last 30 days of life (adjusted RR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.54-0.57), and a 62% decrease in the use of chemotherapy in the last 14 days of life (adjusted RR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.35-0.41). These associations were consistent across major histology groups, as studied in select common specific histologies: acute myeloid leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, chronic myeloid leukemia, and aggressive and indolent non-Hodgkin lymphomas (supplemental Figure 3). Furthermore, across all histologies, hospice enrollees had fewer inpatient days in the last 30 days of life and lower Medicare spending (Figure 2D-E), with an average 41% decrease in the number of inpatient days (adjusted means ratio, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.57-0.60) and a 38% decrease in mean Medicare spending (adjusted means ratio, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.61-0.64).

In the sensitivity analysis, the use of hospice services was more frequent among beneficiaries who died of a cancer other than their primary hematologic malignancy (66.4%) and was much lower among those who had an infection, cardiovascular disease, or other medical event recorded as the cause of death (20.5%, 26.7%, and 44.4%, respectively; supplemental Table 1). Patients dying from infections were most likely to die in the inpatient setting (72.7%), have an ICU admission in the last month of life (69.2%), or be enrolled in hospice for ≤3 days before death (46.2%). However, the associations between the use of hospice services and the indicators of EOL care quality were very similar to the main analysis (supplemental Table 2).

Discussion

In this population-based analysis of EOL care quality among Medicare beneficiaries with hematologic malignancies, we have described a strong association between the use of hospice services and less aggressive care at EOL. Patients with hematologic malignancy who enrolled in hospice at the EOL met established EOL care quality measures at markedly higher rates than did those not enrolled in hospice, similar to outcomes reported among patients with solid tumors in prior studies.35 Interestingly, we found very little variation in these associations and outcomes between subtypes of hematologic cancers, despite their clinical heterogeneity.

These results extend our prior observations from a cohort of Medicare beneficiaries with acute and chronic leukemias.12 What is striking about the current data are its uniformity across a broad range of blood cancer histologies, despite quite different clinical courses for these diseases. For example, although patients with MDS/MPN often succumb to their disease via a mechanism of prolonged bone marrow failure or transformation to acute leukemia, those suffering from myeloma or lymphoma often pursue multiple lines of palliative therapy for relapsing and remitting disease, somewhat akin to metastatic solid tumors, and often over the course of many years. The homogeneity of the association between hospice use and EOL outcomes supports the idea that inferior EOL care quality outcomes in patients with blood cancers may be more attributable to biases and preferences of hematologists and patients with blood cancers or to more global differences in the overall responsiveness of hematologic malignancies to treatment compared with solid tumors, rather than any fundamentally different disease-specific needs. This notion is further supported by the fact that patients whose cause of death was listed as a blood cancer had more EOL chemotherapy use and less hospice use, proportionally, than did patients whose cause of death was listed as “other cancer.” We note, however, that causes of death designated on death certificates are often inaccurate, because distinguishing whether a patient died as a result of infection or their hematologic cancer may not be possible.

The literature on the EOL care among patients with hematologic malignancies cites much higher rates of chemotherapy use at the EOL than we identified in the Medicare data. A retrospective case series from MD Anderson Cancer Center reported that 21% of decedents with hematologic malignancies received chemotherapy in the last 14 days of life.9 This discrepancy has several possible explanations. First, the MD Anderson Cancer Center data set encompassed patients of all ages, whereas our analysis includes only those aged 66 years and older. In younger patients, chemotherapy at the EOL may be more appropriate and goal concordant, wherein some “EOL chemotherapy use” represents treatment-related mortality that is unfortunately expected with aggressive induction regimens and stem cell transplantation. A second plausible explanation is that there is a divide in practice patterns for treatment of aggressive blood cancers between community and academic practices. Community practitioners may be more likely to adhere to EOL care quality outcomes and be less aggressive, in general, in the treatment of blood cancers. Supporting this notion, a prior analysis conducted in the Medicare population suggests that acute myeloid leukemia is being significantly undertreated in the community, with 60% of patients older than 65 years of age never receiving any chemotherapy for AML; indeed, in our study, 36% of patients across all histologies did not receive any chemotherapy.36,37 Although this still seems remarkably high, it is in keeping with previously reported data. Because a significant portion of patients with indolent malignancies, such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia or low-grade MDS, may never require active chemotherapy, we included only patients whose cause of death was a hematologic malignancy. This choice accounted for the possibility that the large number of patients who never received chemotherapy could be attributed to indolent diseases for which chemotherapy may not have been indicated.36,37

Interestingly, despite an increase in hospice utilization and a decrease in inpatient deaths between 2008 and 2015, we also observed an increase in terminal ICU admissions and chemotherapy administration, but no increase in the hospice LOS. We attribute the increase in hospice utilization to overall national trends as the value of hospice care has been increasingly recognized, palliative care burgeoned as a specialty, and initiatives aimed at increasing EOL care discussions took hold.38 The somewhat surprising increase in some indicators of aggressive EOL care may be related to a marked expansion of treatment options for hematologic cancers, including less intensive therapies that replaced cytotoxic chemotherapy for older patients. Availability of additional treatment options may lead patients to pursue active anticancer therapy even in very advanced disease, when previously they may have elected not to receive cancer-directed therapy. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that the steepest trends in the terminal ICU admissions and chemotherapy use at the EOL were observed in myeloma, a disease transformed during the period of our study by the emergence of many effective novel chemotherapeutic agents. Notably, the trend in increased ICU admissions at the EOL occurred in our patient population, whereas a study looking at EOL trends among all Medicare beneficiaries over a similar time period (2009-2015) showed a stabilization in EOL ICU admissions.38 This, along with the fact that decedents in our cohort had lower rates of hospice enrollment (56% vs 60%), were more likely to die in inpatient settings (33% vs 22%), and were more likely to have an ICU admission in the last 30 days of life (37% vs 27%) compared with a contemporary population of Medicare beneficiaries with cancer described by Teno et al, points to the need for a direct comparison and analysis of EOL outcomes between patients with hematologic malignancies and those with solid tumors.39

Our results have significant implications for future efforts to improve the EOL care for older patients with hematologic malignancies, as well as for research that could elucidate why they have suboptimal use of hospice services. We found that hospice enrollees with hematologic malignancies had significantly higher indicators of palliative needs, but evident delayed enrollment and suboptimal hospice LOS suggest that some of those needs may not be reliably met with current hospice services. Despite late enrollment, hospice use was strongly associated with less aggressive care at the EOL. Our prior work suggests that transfusion dependence is 1 major barrier to hospice use in blood cancers, and adequate coverage for palliative transfusions by the Medicare hospice benefit might facilitate earlier enrollment. Hospice and palliative care providers should research and define interventions that could alleviate suffering of patients with hematologic malignancies, whose symptoms and concerns at the EOL may differ from those experienced by patients with solid cancers. Another issue that remains to be better addressed in clinical practice is the conflict between goal-concordant care and the administrative indicators of EOL care quality. The arrival of novel therapies may accentuate the difficulty that patients with hematologic malignancies have already been facing when considering a lingering possibility of cure, despite advanced disease. Providing goal-concordant care may sometimes go against EOL care quality measures established primarily for solid tumors with a longer and more clinically apparent terminal phase. Indeed, our results question whether current “quality measures” represent true care quality if the current hospice services may not be meeting the needs of patients with hematologic malignancies. As the acceptance of hospice increases nationwide, it will be important to make this service more meaningful by offering it earlier in the course of disease rather than in the last days of life.

Our study is limited by several factors. First, descriptive data derived from administrative claims do not elucidate clinical reasons for the use of hospice services, hospitalizations, or ICU admissions; however, they can serve as a benchmark illustrating the EOL outcomes of older patients with hematologic malignancies in the United States. Second, the years that our study covered represented a period during which the importance of palliative care in the treatment of solid tumors burgeoned, but the importance and implementation of palliative care in the hematologic treatment setting were in their infancy. It is possible that outcomes continue to improve as awareness of these issues increases, and we hope to illustrate changes in practice patterns in further research.

Earlier and more frequent use of hospice care services is a plausible solution to improving EOL care quality in hematologic malignancies.40 Ultimately, however, our observations support the need for more research to establish the value of palliative care and hospice for patients with hematologic malignancies and to identify the barriers to achieving quality EOL care in these patients.

Presented in part at the 60th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Diego, CA, 1-4 December 2018.

Data sharing requests should be sent to Adam J. Olszewski (e-mail: adam_olszewski@brown.edu).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the efforts of the National Cancer Institute, the Office of Research, Development and Information, CMS, Information Management Services, Inc., and the SEER Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database.

The collection of cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Public Health as part of the statewide cancer reporting program mandated by California Health and Safety Code Section 103885, the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute SEER Program (under contract HHSN261201000140C awarded to the Cancer Prevention Institute of California, contract HHSN261201000035C awarded to the University of Southern California, and contract HHSN261201000034C awarded to the Public Health Institute), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Program of Cancer Registries (under agreement U58DP003862-01 awarded to the California Department of Public Health). T.W.L. is supported by a Mentored Research Scholar Grant from the American Cancer Society (MRSG-15-185-01-PCSM). A.J.O. is supported by a Research Scholar Grant from the American Cancer Society (128608-RSGI-15-211-01-CPHPS) and an Institutional Development Award Program Infrastructure for Clinical Translational and Research grant from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (U54GM115677).

The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and endorsement by the State of California Department of Public Health, the National Cancer Institute, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or their contractors and subcontractors is not intended nor should be inferred.

Authorship

Contribution: P.C.E. designed research, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; T.W.L. interpreted data and wrote the manuscript; and A.J.O. curated the data, conducted all statistical analyses, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Adam Olszewski, Division of Hematology-Oncology, Rhode Island Hospital, 593 Eddy St, George-353, Providence, RI 02903; e-mail: adam_olszewski@brown.edu.

References

Author notes

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.