Key Points

Human ILC1-like cells kill tumors in a KIR-independent manner.

The cytotoxicity of human ILC1-like cells is impaired in AML at diagnosis but is restored in remission.

Abstract

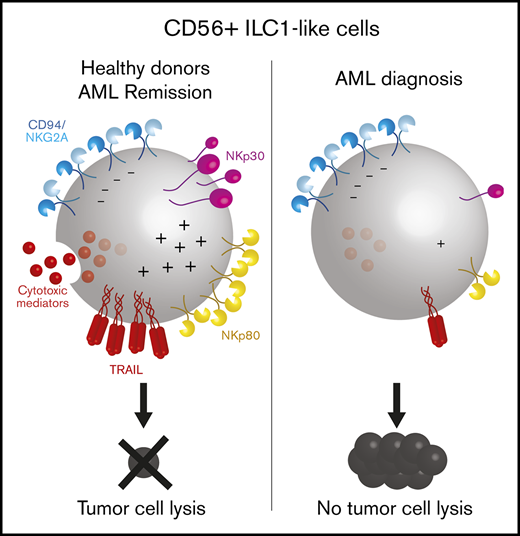

An understanding of natural killer (NK) cell physiology in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) has led to the use of NK cell transfer in patients, demonstrating promising clinical results. However, AML is still characterized by a high relapse rate and poor overall survival. In addition to conventional NKs that can be considered the innate counterparts of CD8 T cells, another family of innate lymphocytes has been recently described with phenotypes and functions mirroring those of helper CD4 T cells. Here, in blood and tissues, we identified a CD56+ innate cell population harboring mixed transcriptional and phenotypic attributes of conventional helper innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) and lytic NK cells. These CD56+ ILC1-like cells possess strong cytotoxic capacities that are impaired in AML patients at diagnosis but are restored upon remission. Their cytotoxicity is KIR independent and relies on the expression of TRAIL, NKp30, NKp80, and NKG2A. However, the presence of leukemic blasts, HLA-E–positive cells, and/or transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) strongly affect their cytotoxic potential, at least partially by reducing the expression of cytotoxic-related molecules. Notably, CD56+ ILC1-like cells are also present in the NK cell preparations used in NK transfer–based clinical trials. Overall, we identified an NK cell–related CD56+ ILC population involved in tumor immunosurveillance in humans, and we propose that restoring their functions with anti-NKG2A antibodies and/or small molecules inhibiting TGF-β1 might represent a novel strategy for improving current immunotherapies.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is the most common acute leukemia in adults, with a 3.7/100 000 incidence per year. AML has a high relapse rate, which decreases patients’ 5-year overall survival to 19%.1 The conventional treatments consist of chemotherapy or allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.2 Moreover, natural killer (NK) cell transfer therapy has been developed and provides good outcome improvement if the donor and recipient are KIR mismatched.3-6

In addition to conventional NKs (cNKs), another lymphocytic innate cell family has recently been identified and named innate lymphoid cells (ILCs). ILCs constitutively express the interleukin-7 (IL-7) receptor α chain (CD127) and are deprived of somatically rearranged antigen-specific receptors and common lineage markers. Whereas cNKs functionally mirror adaptive CD8 T cells, conventional ILCs are considered the innate counterpart of helper CD4 T cells7 ; ILCs secrete pro- or anti-inflammatory cytokines upon sensing the microenvironment and “help” effector cells.7-11

Despite the clear-cut ILC subset delineation, unexpected phenotypic and functional heterogeneity within NK and ILC subsets has recently been reported,12-15 opening novel opportunities for innate cell-based immunotherapies.

Here, we describe an unconventional human ILC1-like cell population with cytotoxic properties that expresses the ILC marker CD127 and CD5616,17 but lacks CD16 and c-Kit (CD117) expression. These CD56+ ILC1-like cells are related to the stage 4b (S4b) NK cells. Their cytolytic mechanism is KIR independent but requires NKp80, NKp30, and TRAIL engagement to lyse both major histocompatibility complex class I (MHCI) positive and negative targets. Similar to previous reports of conventional ILCs18,19 and NKs,20 the frequency and functions of CD56+ ILC1-like cells are impaired in AML patients. At diagnosis, CD56+ ILC1-like cells are significantly reduced, and their killing capacity is defective due to the persistence of NKG2A expression, the inability to release cytotoxic mediators, and the downregulation of NKp80, NKp30, and TRAIL, which is at least partially mediated by transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β). Notably, during remission, the cytotoxic machinery and the receptors’ expression on CD56+ ILC1-like are completely restored.

Overall, we propose that this CD56+ ILC1-like cell population represents an attractive target for immunomodulatory drugs, such as anti-NKG2A antibodies and TGF-βRI inhibitors, in AML patients. Given the presence of these cells in NK-cell preparations used for adoptive transfer, exploiting their properties might provide a powerful approach for maximizing the efficacy of KIR-mismatch independent immunotherapy.

Methods

All the methods used in this article are described as supplemental Information.

Results

CD56+CD16− ILC1-like cells have NK properties and are impaired in AML patients at diagnosis

We recently reported that the ILC1 compartment is numerically and functionally impaired in AML patients at diagnosis.19 Here, we identify a CD16− CD127+ c-Kit− CRTH2− CD56+ cell population, which falls in the ILC1 gate (Figure 1A-B).21 t- t-SNE analysis based on CD127, CD56, CD16, CRTH2, and c-Kit expression is sufficient to clearly discriminate this cell population from conventional ILC (ILC1, ILC2, and “ILC progenitors” [ILCP]22 ) and NK subsets (Figure 1C). In particular, their CD56dim CD16− CD127+ c-Kit− phenotype distinguishes them from the conventional CD56bright and CD56dim NK subsets (Figure 1D). Of note, CD56+ ILC1-like cells do not express CD49a (supplemental Figure 1).

Identification of a CD56+ILC1-like population with NK properties that is impaired in AML patients at diagnosis. (A-B) Representative density plots of the extracellular flow cytometry panel used to identify the cNK cell subsets (A) and the ILC subsets (B) in peripheral blood (PB) mononuclear cells (PBMCs; ILC1 as CRTH2− c-Kit− CD56−, ILC2 as CRTH2+ c-Kit+/− CD56+/−, ILCP as CRTH2− c-Kit+ CD56+/−, and cNKs as CD16− CD56bright and CD16+ CD56dim).21,22 Lineage markers used for the “helper” ILC staining include CD3, CD4, CD8, CD14, CD15, CD16, CD19, CD20, CD33, CD34, CD203c, and FcεRIα; same lineage markers, except for CD16, were used for the cNK staining. (C) CD127, CD56, CD16, CRTH2, c-Kit fluorescence intensity on ILC and NK subsets were concatenated from 5 HDs and analyzed with t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE). c-Kit, CD127, CD56, CD16 expression levels on ILC1, CD56+ ILC1-like cells and NKs are represented in panel D. Representative gating (E) and quantification of CD56+ ILC1-like cell and cNK proportions among lymphocytes in blood from HDs and AML patients at diagnosis (F) (CD56+ ILC1-like cells: HD, n = 47; AML patients: n = 60; cNKs: HD: n = 12, AML: n = 18). (G) Summary of the results of the total ILC proportions and ILC1, ILC2, ILCP, and CD56+ ILC1-like cell subset frequencies among the total ILCs in HD peripheral blood (N = 47, age median 48, interquartile range 31 to 64). (H) Correlation between ILC subsets’ relative frequencies in blood and age (cord blood: n = 9, children: n = 6, [3 to 12] years old, adults: n = 47, age mean 48). (I) CD56+ ILC1-like cell relative frequencies among the total ILCs in tissues from healthy adults (n = 3-18). Spearman correlations were used in panel H. One dot = 1 donor. Mann-Whitney unpaired U tests were used in panel F. ****P < .0001. BM, bone marrow; LN, lymph node. ns, not significant.

Identification of a CD56+ILC1-like population with NK properties that is impaired in AML patients at diagnosis. (A-B) Representative density plots of the extracellular flow cytometry panel used to identify the cNK cell subsets (A) and the ILC subsets (B) in peripheral blood (PB) mononuclear cells (PBMCs; ILC1 as CRTH2− c-Kit− CD56−, ILC2 as CRTH2+ c-Kit+/− CD56+/−, ILCP as CRTH2− c-Kit+ CD56+/−, and cNKs as CD16− CD56bright and CD16+ CD56dim).21,22 Lineage markers used for the “helper” ILC staining include CD3, CD4, CD8, CD14, CD15, CD16, CD19, CD20, CD33, CD34, CD203c, and FcεRIα; same lineage markers, except for CD16, were used for the cNK staining. (C) CD127, CD56, CD16, CRTH2, c-Kit fluorescence intensity on ILC and NK subsets were concatenated from 5 HDs and analyzed with t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE). c-Kit, CD127, CD56, CD16 expression levels on ILC1, CD56+ ILC1-like cells and NKs are represented in panel D. Representative gating (E) and quantification of CD56+ ILC1-like cell and cNK proportions among lymphocytes in blood from HDs and AML patients at diagnosis (F) (CD56+ ILC1-like cells: HD, n = 47; AML patients: n = 60; cNKs: HD: n = 12, AML: n = 18). (G) Summary of the results of the total ILC proportions and ILC1, ILC2, ILCP, and CD56+ ILC1-like cell subset frequencies among the total ILCs in HD peripheral blood (N = 47, age median 48, interquartile range 31 to 64). (H) Correlation between ILC subsets’ relative frequencies in blood and age (cord blood: n = 9, children: n = 6, [3 to 12] years old, adults: n = 47, age mean 48). (I) CD56+ ILC1-like cell relative frequencies among the total ILCs in tissues from healthy adults (n = 3-18). Spearman correlations were used in panel H. One dot = 1 donor. Mann-Whitney unpaired U tests were used in panel F. ****P < .0001. BM, bone marrow; LN, lymph node. ns, not significant.

In AML patients at diagnosis (n = 60, [35 to 97 years old]; supplemental Table 1), the proportions of this population among lymphocytes are strongly reduced (Figure 1E-F), independently of the patients’ age (data not shown). The CD56dim NK compartment is also impaired, whereas the CD56bright NK cell proportions are comparable between the patients and healthy donors (HDs) (Figure 1E-F).

In the HDs (n = 47, median age 48, interquartile range 31 to 64), CD56+ ILC1-like cells represent 38.5% of all Lineage− CD127+ cells in the peripheral blood (range 9.4% to 69.0%; Figure 1G). Similar to the cNK frequencies, which are known to be influenced by age,23-25 compared with the other “helper” ILCs, we observed a significant CD56+ ILC1-like increase in the elderly donors (Figure 1H). The analysis of ILC frequencies within lymphoid and nonlymphoid organs from HDs and cadavers shows that CD56+ ILC1-like cells are also present in those tissues (Figure 1I).

We then evaluated the CD56+ ILC1-like cytokine profile in response to IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18 stimulation (n = 4). When stimulated, these cells secrete interferon-γ and IL-8, the latter distinguishing them from the CD56dim NKs (supplemental Figure 2A-B).

RNA sequencing reveals a CD56+ ILC1-like cell transcriptomic signature

To investigate specific CD56+ ILC1-like cell features, we performed an RNA-sequencing analysis of highly pure ILC and cNK subsets from the peripheral blood of HDs (n = 3) (supplemental Figure 3A-B). In a principal component analysis of the ILC and NK subsets for their expression of cNK markers, CD56+ ILC1-like cells appear to be more closely related to CD56bright NKs and ILCP than ILC1, ILC2, and CD56dim NKs (Figure 2A; supplemental Figure 3C-D).

Transcriptomic signature of ex vivo CD56+ILC1-like cells in peripheral blood from HDs. (A) Principal component analysis (PCA) of ex vivo fluorescence-activated cell–sorted ILC and NK subsets from HDs peripheral blood (n = 3). (B) Heat map of z scores of the expression levels of genes encoding ILC/NK transcription factors (n = 3). (C) Heat map of log counts per million (CPM) of the 100 most differentially expressed genes between CD56+ ILC1-like cells and ILC1, ILC2, ILCP, CD56bright NKs or CD56dim NKs. The GO pathway to which each gene belongs is represented at the left of each heat map: Metabolic process GO0008152 (“Metabolism"); Lymphocyte activation GO0046649 (“Activation”); Leukocyte migration GO0050900 (“Migration”); Immune effector process GO0002252 (“Effector”). Max, maximum; Min, minimum.

Transcriptomic signature of ex vivo CD56+ILC1-like cells in peripheral blood from HDs. (A) Principal component analysis (PCA) of ex vivo fluorescence-activated cell–sorted ILC and NK subsets from HDs peripheral blood (n = 3). (B) Heat map of z scores of the expression levels of genes encoding ILC/NK transcription factors (n = 3). (C) Heat map of log counts per million (CPM) of the 100 most differentially expressed genes between CD56+ ILC1-like cells and ILC1, ILC2, ILCP, CD56bright NKs or CD56dim NKs. The GO pathway to which each gene belongs is represented at the left of each heat map: Metabolic process GO0008152 (“Metabolism"); Lymphocyte activation GO0046649 (“Activation”); Leukocyte migration GO0050900 (“Migration”); Immune effector process GO0002252 (“Effector”). Max, maximum; Min, minimum.

We then analyzed their transcription factor profile at RNA level. These cells express similar levels of TBX21 (T-bet), EOMES, and RUNX3 transcripts as cNKs. Their expression of ZBTB16 (promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger protein [PLZF]) and aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) transcripts is intermediate compared with CD56bright and CD56dim NKs. However, CD56dim NKs express higher levels of NFIL3 transcripts than CD56+ ILC1-like cells (Figure 2B). Furthermore, a principal component analysis reveals that the expression of PLZF, GATA3, Eomes, RORγt, and T-bet at protein level is sufficient to discriminate CD56+ ILC1-like cells from the other ILC and NK subsets (supplemental Figure 3E-H).

Then, we analyzed the 100 genes with the lowest or highest log fold change between the CD56+ ILC1-like cells and conventional ILC/NK subsets (Figure 2C). The CD56+ ILC1-like cells display higher levels of NK-associated transcripts than ILC1, ILC2, and ILCP (eg, EOMES, KLRD1, KLRC2, and KLRF1). CD56+ ILC1-like cell transcriptomic signature includes genes encoding cytokine receptors and chemokine receptors. By associating Gene Ontology (GO) pathways to each of the differentially expressed genes, we observed that they are mostly involved in lymphocyte activation (GO pathway GO0046649), immune effector process (GO0002252), leukocyte migration (GO0050900), and metabolism (GO0008152).

To confirm that CD56+ ILC1-like cells display a specific metabolism compared with the conventional ILC and NK subsets, we evaluated their nutrient uptake and mitochondrial activity (supplemental Figure 4). The CD56+ ILC1-like cells display a lower glucose analog (2-(N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino)-2-deoxyglucose) uptake than the ILC2 and cNKs and a higher fatty acid uptake than the CD56dim NKs. To assess their specific mitochondrial activity, we evaluated the ratio of the uptake of MitoTracker deep red to that of MitoTracker green.26 The ratio in CD56+ ILC1-like cells is higher than in the ILC1 and tend to be higher compared with cNKs. Hence, the distinct metabolic transcriptional pattern of CD56+ ILC1-like cells is reflected by their specific nutrient uptake and mitochondrial activity.

CD56+ ILC1-like cells are cytotoxic effectors regulated by the NKp30, NKp80, TRAIL, and HLA-E pathways

Based on the CD56+ ILC1-like cell-specific transcriptomic signature involving genes participating in immune effector processes and lymphocyte activation, we directly evaluated the CD56+ ILC1-like cell cytotoxic activity (Figure 3). CD56+ ILC1-like cells express NKp30, NKp80, CD94/NKG2A, and DNAM-1 at a high level, whereas low levels of NKp44, NKp46, and NKG2C were observed (Figure 3A). TRAIL expression is comparable between the CD56+ ILC1-like cells and CD56bright NKs but varies depending on the donor’s age (data not shown). Subsequently, we aimed to ascertain whether CD56+ ILC1-like cells contain death-inducing mediators. We observed a significant CD56+ ILC1-like cell production of granzymes A, B, K, and M, perforin and granulysin, with the highest levels measured for granzyme A and M (Figure 3B; supplemental Figure 5A). Next, we cocultured CD56+ ILC1-like cells with the standard NK-sensitive MHCI− K562 cell line (Figure 3C). After 4 hours, CD56+ ILC1-like cells upregulate CD107a, demonstrating their ability to degranulate. To confirm their cytotoxicity, we analyzed CD56+ ILC1-like cell-mediated target lysis using 51Cr-release assays. CD56+ ILC1-like cells lyse K562 to an extent comparable to that of cNKs, whereas the helper ILCs fail to induce any target cell lysis (Figure 3D). In accordance with the absence of KIR receptors, CD56+ ILC1-like cells are also able to lyse the MHCI+ BJAB and U937 cell lines (Figure 3E; supplemental Figure 5B). To investigate whether DNAM-1, NKp30, NKp80, and TRAIL, which are expressed at the highest levels by CD56+ ILC1-like cells (Figure 3A), are involved in cytotoxicity, we cocultured CD56+ ILC1-like cells with targets in the presence of specific blocking reagents (Figure 3F). The addition of anti–DNAM-1 blocking antibodies does not affect the CD56+ ILC1-like cell killing potential. However, the presence of anti-NKp30 blocking antibodies strongly reduces their killing activity. We also confirmed that TRAIL is involved in their cytotoxicity as the CD56+ ILC1-like cell-mediated killing of the TRAIL-sensitive BJAB line27-29 was decreased in the presence of a TRAIL decoy receptor. Subsequently, we cocultured the CD56+ ILC1-like cells with the U937 line, which expresses the ligand for NKp80 (ie, Activation-Induced C-type Lectin (supplemental Figure 5C). The addition of NKp80 blocking antibodies decreases the CD56+ ILC1-like cell-killing capacity. Finally, based on the high expression of CD94/NKG2A by CD56+ ILC1-like cells (Figure 3A), we compared the CD56+ ILC1-like cell-mediated lysis of wild-type (HLA-E negative) and HLA-E–transfected (HLA-E+) 721.221 tumor cells (Figure 3G; supplemental Figure 4D). CD56+ ILC1-like cell cytotoxicity is impaired when the targets express HLA-E. Overall, we show that CD56+ ILC1-like cells display high cytotoxicity triggered by the NKp30, NKp80, and TRAIL pathways and inhibited upon HLA-E binding.

CD56+ILC1-like cells are cytotoxic effectors regulated by the NKp30, NKp80, TRAIL, and HLA-E pathways. (A) Extracellular flow cytometry analysis of NK receptor expression in ILCP, CD56+ ILC1-like cells, and cNKs (n = 4-18). (B) Intracellular flow cytometry was performed using HD PBMCs to assess CD56+ ILC1-like cell production of granzyme A (n = 15), granzyme B (n = 15), granzyme K (n = 12), granzyme M (n = 12), perforin (n = 12), and granulysin (n = 12). (C) Extracellular flow cytometry was performed after a 4-hour coculture of ILC/NK-enriched PBMCs with K562 (ratio E:T 1:1), anti-CD107a, and Golgistop to assess CD56+ ILC1-like cell degranulation (n = 16). (D) Specific lysis of the K562 tumor cell line by CD56+ ILC1-like cells, cNKs, and helper ILCs (results in duplicate). (E) Specific lysis of the U937, K562, and BJAB tumor cell lines by CD56+ ILC1-like cells (results in duplicate). (F) Specific lysis by CD56+ ILC1-like cells of K562 (ratio E:T 20:1), BJAB (ratio E:T 20:1), and U937 (ratio E:T 10:1) tumor cell lines in the presence of anti-DNAM-1, anti-NKp30, and anti-NKp80 blocking antibodies or TRAIL decoy receptor. (G) Specific lysis of wild-type (WT) or HLA-E–transfected 721.221 tumor cell lines by CD56+ ILC1-like cells (results in triplicate). One dot = 1 donor. Statistical tests used for analyses: panel B: Mann-Whitney unpaired U test; panel C: Wilcoxon paired t test, panel G: multiple Holm-Sidak t tests. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001.

CD56+ILC1-like cells are cytotoxic effectors regulated by the NKp30, NKp80, TRAIL, and HLA-E pathways. (A) Extracellular flow cytometry analysis of NK receptor expression in ILCP, CD56+ ILC1-like cells, and cNKs (n = 4-18). (B) Intracellular flow cytometry was performed using HD PBMCs to assess CD56+ ILC1-like cell production of granzyme A (n = 15), granzyme B (n = 15), granzyme K (n = 12), granzyme M (n = 12), perforin (n = 12), and granulysin (n = 12). (C) Extracellular flow cytometry was performed after a 4-hour coculture of ILC/NK-enriched PBMCs with K562 (ratio E:T 1:1), anti-CD107a, and Golgistop to assess CD56+ ILC1-like cell degranulation (n = 16). (D) Specific lysis of the K562 tumor cell line by CD56+ ILC1-like cells, cNKs, and helper ILCs (results in duplicate). (E) Specific lysis of the U937, K562, and BJAB tumor cell lines by CD56+ ILC1-like cells (results in duplicate). (F) Specific lysis by CD56+ ILC1-like cells of K562 (ratio E:T 20:1), BJAB (ratio E:T 20:1), and U937 (ratio E:T 10:1) tumor cell lines in the presence of anti-DNAM-1, anti-NKp30, and anti-NKp80 blocking antibodies or TRAIL decoy receptor. (G) Specific lysis of wild-type (WT) or HLA-E–transfected 721.221 tumor cell lines by CD56+ ILC1-like cells (results in triplicate). One dot = 1 donor. Statistical tests used for analyses: panel B: Mann-Whitney unpaired U test; panel C: Wilcoxon paired t test, panel G: multiple Holm-Sidak t tests. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001.

CD56+ ILC1-like cells possess common features with NK cell developmental intermediates

Freud and colleagues recently showed that ILC3 and NKs share a common progenitor that is distinct from ILC2 progenitors.30 They also demonstrated that S4a NK developmental intermediates possess both NK- and ILC3-related characteristics.31 We thus compared the CD56+ ILC1-like cells with the NK developmental intermediates in terms of phenotype, based on their previously published data31 (Table 1). NKp80 is acquired in NKs upon maturation from the S4b stage, alongside the production of cytotoxic mediators. Based on their expression of NKp80 and cytolytic activity, CD56+ ILC1-like cells are more mature than the S3 and S4a NK cells. However, being CD16-negative, these cells are clearly distinct from S5 NKs. CD56+ ILC1-like cells share similar features with S4b NKs, because they express CD94/NKG2A heterodimers, NKG2D, CXCR3, and CD122, while being devoid of KIR receptors in blood. However, S4b NKs are reportedly CD127low/− and c-Kit+/−. S4b mainly comprises CD56bright NKs, which have a distinct transcriptomic profile compared with CD56+ ILC1-like cells (Figure 2C). In order to formally evaluate the capacity of CD56+ ILC1-like cells to differentiate into other ILC subsets or NK developmental stages, we sorted these cells and cultured them on OP9 stromal cells in the presence of IL-7 with or without the addition of IL-15 (supplemental Figure 6A-B). Their phenotype was analyzed after 10 days. The CD16− CD94high c-Kit− cell population remains the major one upon culture, in particular, in the presence of IL-15. Two minor cell populations emerge by the upregulation of CD16 or c-Kit. Next, to determine whether CD56+ ILC1-like cells represent an effector population generated in the periphery, we monitored their presence in human fetal tissues and during immune reconstitution in humanized mice. CD56+ ILC1-like cells were detectable in all human fetal tissues analyzed (supplemental Figure 6C) and could be identified as early as 8 weeks postreconstitution in humanized mice (supplemental Figure 6D-E). To further dissect their developmental requirement, we monitored the CD56+ ILC1-like cell frequencies in patients with severe combined immunodeficiency (supplemental Figure 6F-G). As conventional ILCs and NKs, CD56+ ILC1-like cells require JAK3 and ADA genes for their development, whereas they are able to develop in the absence of ARTEMIS and CD3D genes. We identified CD56+ ILC1-like cells and cNKs, yet at reduced levels, in an IL2RG-deficient patient, suggesting a hypomorphic mutation with reduced penetrance.32,33 These cells, as cNKs and helper ILCs, are also present in a RAG1-deficient patient, whereas they are decreased in a RAG2-deficient patient, in contrast to cNK and helper ILCs. RAG1 is expressed in common lymphoid progenitors that are committed to the NK lineage34 and might thus be required for the differentiation of CD56+ ILC1-like cells. The absence of CD56+ ILC1-like cells in the RAG1-deficient patient might also be due to the ILC and NK genomic instability observed in mice upon RAG deficiency.35 Overall, these results suggest that CD56+ ILC1-like cells are related to S4b NK cells and therefore might share similarities with cNKs in terms of development.

Extracellular phenotype of CD56+ILC1-like cells compared to previously published NK development stage phenotypes

| Marker . | S3 . | S4a . | S4b . | S5 . | CD56+ ILC1-like . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD16 | − | − | − | + | − |

| CD56 | +/− | + | + | + | + |

| CD127 | + | +/− | Low/− | − | + |

| c-KIT | + | +/− | +/− | +/− | − |

| CD94 | − | + | + | +/− | + |

| NKG2A | − | + | + | + | + |

| NKG2C | − | − | +/− | +/− | +/− |

| NKG2D | − | + | + | + | + |

| KIR2D | − | − | − | + | − |

| NKp80 | − | − | + | + | + |

| CXCR3 | − | +/− | + | + | + |

| CD122 | − | + | + | + | + |

| Perforin | − | − | + | + | + |

| Granzyme A | − | − | +/− | + | + |

| Granzyme B | − | − | +/− | +/− | + |

| Granzyme K | − | − | + | + | + |

| Marker . | S3 . | S4a . | S4b . | S5 . | CD56+ ILC1-like . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD16 | − | − | − | + | − |

| CD56 | +/− | + | + | + | + |

| CD127 | + | +/− | Low/− | − | + |

| c-KIT | + | +/− | +/− | +/− | − |

| CD94 | − | + | + | +/− | + |

| NKG2A | − | + | + | + | + |

| NKG2C | − | − | +/− | +/− | +/− |

| NKG2D | − | + | + | + | + |

| KIR2D | − | − | − | + | − |

| NKp80 | − | − | + | + | + |

| CXCR3 | − | +/− | + | + | + |

| CD122 | − | + | + | + | + |

| Perforin | − | − | + | + | + |

| Granzyme A | − | − | +/− | + | + |

| Granzyme B | − | − | +/− | +/− | + |

| Granzyme K | − | − | + | + | + |

+, expression of the marker; −, no expression of the marker; Low, low expression of the marker.

CD56+ ILC1-like cytotoxicity is impaired in AML patients at diagnosis

In order to evaluate the role of CD56+ ILC1-like cells in AML disease, we investigated their cytotoxic profile at diagnosis. The CD56+ ILC1-like cell expression of TRAIL, NKp30, and NKp80 is strongly reduced in the patients compared with HDs (Figure 4A). Notably, TRAIL and NKp80 are specifically decreased in the CD56+ ILC1-like cells but not in the cNKs. Then, we analyzed the CD56+ ILC1-like cell release of cytotoxic mediators. The patients’ CD56+ ILC1-like cells produce amounts of granzymes A, B, and K and perforin that are similar to those in the HDs, but no granulysin is produced. In contrast, the granulysin levels in the cNKs are not impaired in the patients, and the granzyme A level is even increased in CD56bright NKs in AML (Figure 4B). The degranulation of CD56+ ILC1-like cells in AML is significantly impaired as assessed in cocultures with the K562 line or autologous blasts (Figure 4C-D). This impairment could be explained by the regulation of CD56+ ILC1-like cell cytotoxicity through NKp30, TRAIL, NKp80, or HLA-E in the case of primary AML blasts. Indeed, we observed HLA-E expression in primary AML blasts and NKG2A expression in patients’ CD56+ ILC1-like cells, suggesting that the HLA-E/CD94-NKG2A pathway negatively regulates CD56+ ILC1-like cells (Figure 4E-F). In line with this, in the patients, the CD94/NKG2A expression is preserved on CD56+ ILC1-like cells. Overall, we show that the CD56+ ILC1-like cell cytotoxic machinery is impaired in AML patients at diagnosis, suggesting that these cells are unable to limit AML oncogenesis.

CD56+ILC1-like cell cytotoxicity is impaired in AML patients at diagnosis. (A) TRAIL, NKp30, and NKp80 expression in CD56+ ILC1-like cells and cNKs in HDs (CD56+ ILC1-like: n = 12-18, cNKs: n = 11-15) and AML patients at diagnosis (CD56+ ILC1-like: n = 11-20, cNKs: n = 8-10) by extracellular flow cytometry. (B) Intracellular flow cytometry was performed using PBMCs from AML patients at diagnosis to assess granzyme A (n = 4), granzyme B (n = 4), granzyme K (n = 4), perforin (n = 4), and granulysin (n = 7) expression in the CD56+ ILC1-like cells and cNKs. The results are compared with the values obtained in the HDs. (C-D) CD107a expression in CD56+ ILC1-like cells is assessed by flow cytometry after a 4-hour incubation of ILC/NK-enriched PBMCs from HDs (n = 16) or AML patients at diagnosis (n = 4-13) with medium, the K562 tumor cell line, or blasts at a ratio of 1:1. Representative density plot of CD107a expression is shown in panel C, and the summary results are shown in panel D (1 dot = 1 donor). (E) Representative density plot of HLA-E expression in primary leukemic AML blasts. (F) Summary of HLA-E expression in primary leukemic AML blasts (n = 5). (G) Flow cytometry analysis of CD94, NKG2A, and NKG2C in CD56+ ILC1-like cells from AML patients at diagnosis (n = 3-10) and HDs (n = 5-17). One dot = 1 donor. Statistical tests used: panels A-B,D,G: Mann-Whitney U test. **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001.

CD56+ILC1-like cell cytotoxicity is impaired in AML patients at diagnosis. (A) TRAIL, NKp30, and NKp80 expression in CD56+ ILC1-like cells and cNKs in HDs (CD56+ ILC1-like: n = 12-18, cNKs: n = 11-15) and AML patients at diagnosis (CD56+ ILC1-like: n = 11-20, cNKs: n = 8-10) by extracellular flow cytometry. (B) Intracellular flow cytometry was performed using PBMCs from AML patients at diagnosis to assess granzyme A (n = 4), granzyme B (n = 4), granzyme K (n = 4), perforin (n = 4), and granulysin (n = 7) expression in the CD56+ ILC1-like cells and cNKs. The results are compared with the values obtained in the HDs. (C-D) CD107a expression in CD56+ ILC1-like cells is assessed by flow cytometry after a 4-hour incubation of ILC/NK-enriched PBMCs from HDs (n = 16) or AML patients at diagnosis (n = 4-13) with medium, the K562 tumor cell line, or blasts at a ratio of 1:1. Representative density plot of CD107a expression is shown in panel C, and the summary results are shown in panel D (1 dot = 1 donor). (E) Representative density plot of HLA-E expression in primary leukemic AML blasts. (F) Summary of HLA-E expression in primary leukemic AML blasts (n = 5). (G) Flow cytometry analysis of CD94, NKG2A, and NKG2C in CD56+ ILC1-like cells from AML patients at diagnosis (n = 3-10) and HDs (n = 5-17). One dot = 1 donor. Statistical tests used: panels A-B,D,G: Mann-Whitney U test. **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001.

CD56+ ILC1-like cell cytotoxicity is restored in AML patients during remission and might be modulated by leukemic blasts and TGF-β1

The CD56+ ILC1-like cell proportions in the AML patients at diagnosis and during remission are comparable (n = 14) (Figure 5A). However, we observed a trend toward a CD56+ ILC1-like cell increase upon remission in 5 of 7 patients with paired diagnosis/remission peripheral blood samples (Figure 5B). Then, we evaluated the CD56+ ILC1-like cell degranulation potential in the AML patients during remission. Notably, the CD56+ ILC1-like cell degranulation capacity toward the K562 cells is restored in remission (Figure 5C). As we previously showed that TRAIL, NKp30, and NKp80 were involved in CD56+ ILC1-like cell cytotoxicity (Figure 3F) and that their expression was decreased in CD56+ ILC1-like cells from AML patients at diagnosis (Figure 4A), we investigated their expression in CD56+ ILC1-like cells in remission (n = 6) (Figure 5D). Interestingly, the expression of these molecules is restored in the patients during remission.

CD56+ILC1-like cell cytotoxicity is restored in AML patients during remission and is modulated by blasts and TGF-β1. (A) Comparison of peripheral blood (PB) CD56+ ILC1-like cell relative frequencies in AML patients at diagnosis and during remission (n = 12). (B) Comparison of PB CD56+ ILC1-like cell frequencies in paired AML patient samples at diagnosis and during remission (n = 7). (C) Comparison of CD56+ ILC1-like cell AML patients at diagnosis or during remission to determine the degranulation capacity after a 4-hour coculture of ILC/NK-enriched PBMCs with K562 (ratio E:T 1:1), anti-CD107a, and Golgistop (remission: n = 3). (D) Comparison of TRAIL, NKp30, and NKp80 expression in PB CD56+ ILC1-like cells from AML patients at diagnosis (n = 10) and during remission (n = 5). (E-F) PBMCs from AML patients at diagnosis were depleted of CD33+ blasts and cultured for 24 hours in complete medium. (E) Extracellular flow cytometry was performed to assess TRAIL, NKp30, and NKp80 expression in CD56+ ILC1-like cells (n = 6-7). Correlation between TRAIL expression after the 24 h culture and blast frequencies in PB (n = 4, panel F). (G) PBMCs from HDs were enriched in ILC/NK cells and cultured for 24 hours with medium only or supplemented with rhTGF-β1 at 5 ng/mL (n = 8). TRAIL, NKp30, and NKp80 expression was assessed by flow cytometry after the culture. (H) Heat map of z scores of expression levels of genes encoding TGF-β receptors in ILCs and cNKs (n = 3). (I) Free/total TGF-β1 ratio in sera from HDs and AML patients. Sera with concentrations above the limit of detection of the assay are shown (HDs: n = 9, AML patients: n = 11). (J) Kaplan-Meier overall survival analysis based on TGF-β1 expression in AML patients from The Cancer Genome Atlas program (TCGA) (n = 125). We excluded patients presenting a t(15;17) translocation (ie, patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia as classified according to the 2017 European LeukemiaNet recommendations36) from our analysis since this condition represents a distinct AML pathophysiological entity. Statistical tests used: panels C-D: Mann-Whitney unpaired U test; panels E,G: Wilcoxon paired t test; panel F: Spearman correlation; panel J: difference in overall survival (OS) between AML patients with high (n = 64) or low (n = 61) TGF-β1 expression based on TCGA data. *P < .05, ***P < .001.

CD56+ILC1-like cell cytotoxicity is restored in AML patients during remission and is modulated by blasts and TGF-β1. (A) Comparison of peripheral blood (PB) CD56+ ILC1-like cell relative frequencies in AML patients at diagnosis and during remission (n = 12). (B) Comparison of PB CD56+ ILC1-like cell frequencies in paired AML patient samples at diagnosis and during remission (n = 7). (C) Comparison of CD56+ ILC1-like cell AML patients at diagnosis or during remission to determine the degranulation capacity after a 4-hour coculture of ILC/NK-enriched PBMCs with K562 (ratio E:T 1:1), anti-CD107a, and Golgistop (remission: n = 3). (D) Comparison of TRAIL, NKp30, and NKp80 expression in PB CD56+ ILC1-like cells from AML patients at diagnosis (n = 10) and during remission (n = 5). (E-F) PBMCs from AML patients at diagnosis were depleted of CD33+ blasts and cultured for 24 hours in complete medium. (E) Extracellular flow cytometry was performed to assess TRAIL, NKp30, and NKp80 expression in CD56+ ILC1-like cells (n = 6-7). Correlation between TRAIL expression after the 24 h culture and blast frequencies in PB (n = 4, panel F). (G) PBMCs from HDs were enriched in ILC/NK cells and cultured for 24 hours with medium only or supplemented with rhTGF-β1 at 5 ng/mL (n = 8). TRAIL, NKp30, and NKp80 expression was assessed by flow cytometry after the culture. (H) Heat map of z scores of expression levels of genes encoding TGF-β receptors in ILCs and cNKs (n = 3). (I) Free/total TGF-β1 ratio in sera from HDs and AML patients. Sera with concentrations above the limit of detection of the assay are shown (HDs: n = 9, AML patients: n = 11). (J) Kaplan-Meier overall survival analysis based on TGF-β1 expression in AML patients from The Cancer Genome Atlas program (TCGA) (n = 125). We excluded patients presenting a t(15;17) translocation (ie, patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia as classified according to the 2017 European LeukemiaNet recommendations36) from our analysis since this condition represents a distinct AML pathophysiological entity. Statistical tests used: panels C-D: Mann-Whitney unpaired U test; panels E,G: Wilcoxon paired t test; panel F: Spearman correlation; panel J: difference in overall survival (OS) between AML patients with high (n = 64) or low (n = 61) TGF-β1 expression based on TCGA data. *P < .05, ***P < .001.

We aimed to explore the putative mechanism(s) inhibiting the cytotoxicity of CD56+ ILC1-like cells in patients. To determine whether AML blasts directly impair CD56+ ILC1-like cell functions, we removed the leukemic blasts from PBMCs from AML patients at diagnosis and cultured the blast-depleted cells for 24 hours. Although NKp30 and NKp80 expression is not modulated by the absence of blasts, TRAIL expression is upregulated in the CD56+ ILC1-like cells following blast removal (Figure 5E). A positive correlation was observed between the circulating AML blast frequencies and the extent of TRAIL restoration following blast removal (Figure 5F). To identify potential candidates leading to the CD56+ ILC1-like cell impaired function in AML, we cultured CD56+ ILC1-like cells from HDs with different inhibitory molecules known to be involved in the AML immunosuppressive microenvironment. Interestingly, we observed that the TRAIL and NKp30, but not NKp80, expression levels are decreased following a 24-hour culture with human recombinant TGF-β1 (Figure 5G). TGF-β1 possibly binds TGF-βR, which we found to be expressed on CD56+ ILC1-like cells (Figure 5H). We also found circulating TGF-β1 in the patient serum (Figure 5I). An analysis of data from TCGA shows that overall survival is lower in the patients with a high TGF-β1 expression level (Figure 4J), in line with its immunosuppressive effect.37 We thus hypothesize that TGF-β1 might impair CD56+ ILC1-like cell cytotoxicity in AML patients. AML blasts have been shown to produce AhR ligands.38 We thus incubated NK/ILC-enriched PBMCs from HDs with the AhR ligand FICZ overnight in the presence of IL-2 and evaluated its impact on cNKs and CD56+ ILC1-like cell degranulation toward K562 (supplemental Figure 7A). AhR ligand slightly decreases the degranulation capacity of CD56+ ILC1-like cells and CD56dim NKs in 5 out of 8 donors. Preincubating NK/ILC-enriched PBMCs with the AhR agonist before IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18 stimulation also impairs CD56+ ILC1-like cell function, in terms of their interferon-γ production (supplemental Figure 7B). Overall, CD56+ ILC1-like cell cytotoxicity in AML might be impaired by TGF-β1 and AhR ligands and is restored upon remission.

CD56+ ILC1-like cells are present in NK-cell preparations used for NK-cell transfer therapy

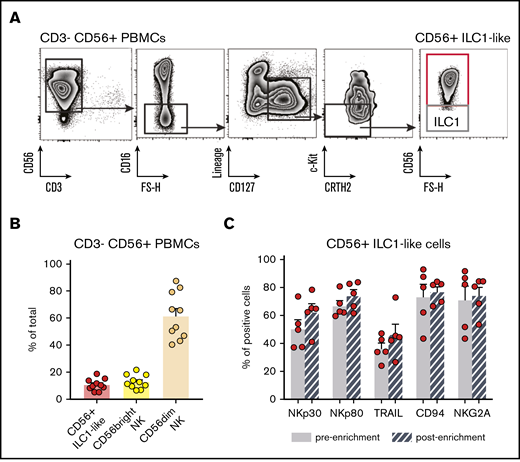

Finally, because CD56+ ILC1-like cells constitutively express the CD56 marker (Figure 1B), we hypothesized that these cells might be present in NK preparations used for NK cell transfer to AML patients. Indeed, haploidentical NK cell transfer consists of injecting enriched CD3−CD56+ haploidentical cells.3-6 To verify this hypothesis, we applied NK cell purification protocols used for transfer therapy to PBMCs from HDs (n = 10). After the 2-step purification process used in the clinical setting, we evaluated the presence of ILCs in the preparation by flow cytometry. Interestingly, the fraction of purified CD3−CD56+ cells contains CD56+ ILC1-like cells in addition to CD16−CD56bright and CD16+CD56dim cNKs (Figure 6A-B). Of note, the CD56+ ILC1-like cell phenotype is conserved after the enrichment (Figure 6C). Therefore, cytotoxic CD56+ ILC1-like cells are present in cell preparations used for the haploidentical transfer of NK cells in AML patients.

CD56+ILC1-like cells are present in NK-cell preparations used for NK-cell transfer therapy. (A) Representative density plots of the extracellular flow cytometry panel used to identify the ILC subsets in CD3− CD56+-enriched fractions of HD PBMCs. (B) Proportions of total ILCs (Lineage−CD127+), CD56bright CD16−, and CD56dim CD16+ NKs in NK-cell transfer therapy products from HD PBMCs (n = 10). (C) NK marker expression on PB CD56+ ILC1-like cells before and after the CD3− CD56+ enrichment (n = 5).

CD56+ILC1-like cells are present in NK-cell preparations used for NK-cell transfer therapy. (A) Representative density plots of the extracellular flow cytometry panel used to identify the ILC subsets in CD3− CD56+-enriched fractions of HD PBMCs. (B) Proportions of total ILCs (Lineage−CD127+), CD56bright CD16−, and CD56dim CD16+ NKs in NK-cell transfer therapy products from HD PBMCs (n = 10). (C) NK marker expression on PB CD56+ ILC1-like cells before and after the CD3− CD56+ enrichment (n = 5).

Discussion

We report the identification of an unconventional CD127+ CD56+ c-Kit− ILC population sharing features with both ILCs and S4b NKs. This innate effector cell type might represent an attractive target for expanding the current options of immunotherapy for AML patients, whose prognosis remains overall unsatisfactory.36

Despite their relatedness with helper ILCs and cNKs in terms of nomenclature, we observed that CD127, c-Kit, CD56, CRTH2, and CD16 expression at protein level are sufficient to discriminate these CD56+ ILC1-like cells. RNA sequencing of these cells shows distinct transcriptomic signature compared with helper ILCs and cNKs.

CD56+ ILC1-like cells share similar features with S4b NK cells in terms of phenotype and function, based on published data.30,31 However, the S4b NK cells are reported to be CD127low/−. Upon culture on OP9 stromal cells, CD56+ ILC1-like cells are able to partially differentiate into both S5 and S4a NK cells. This finding is consistent with their closeness to S4b NKs known to differentiate into S5 NKs. Future studies should further compare the differentiation potential of CD56+ ILC1-like cells and S4b NK cells using OP9 stromal cell culture and humanized mice. The dynamics of transcription factor expression by CD56+ ILC1-like cells throughout the differentiation process and in disease should be further assessed in humanized mice and in AML patients. Based on current data, we hypothesize that CD56+ ILC1-like cells might represent a developmental intermediate subpopulation between ILCs and NK cells. CD56+ ILC1-like cells are present at fetal stage, yet their proportion increases with the age, suggesting an age-driven maturation of these cells. ILCs and NK cells lack the requirement for prior sensitization or exposure to elicit a response to a pathogen or tumor. We offer a hypothesis that CD56+ ILC1-like cells might continue to promote surveillance of tumorigenesis or microbial infections in settings of waning antitumor or antimicrobial cell-mediated immunity. These observations further support the hypothesis that triggering these cells in patients with cancer might help to restrict tumor burden.

Although CD56+ ILC1-like cells can secrete cytokines, their main function resides in their KIR-independent cytotoxic activity. Uncontrolled CD56+ ILC1-like cell activities might be limited by NKG2A/CD94, whereas NKp30, NKp80, and TRAIL are the main receptors conferring cytotoxic potential. We previously described that NKp30 overexpression in ILC2 in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia39 is linked to their hyperactivity. NKp80 has been studied in the context of NK cell maturation31 and has been described as an NK cell coactivating receptor,40 but no reports regarding its expression and role in human ILCs are available. Our results suggest that its presence might be relevant in the context of Activation-Induced C-type Lectin+ targets. Finally, unconventional Eomes− group 1 ILCs have been reported to express TRAIL in the liver and exert TRAIL-dependent cytotoxicity.41-43 Here, we show that the CD56+ ILC1-like cell cytotoxic machinery is impaired in AML patients. Therefore, by therapeutically activating the NKp30, NKp80, and TRAIL pathways and inhibiting NKG2A/HLA-E interactions, the cytotoxicity of CD56+ ILC1-like cell might be restored, and subsequently AML could be controlled. Hence, the administration of the checkpoint inhibitor anti-NKG2A antibody44 could unleash hypofunctional CD56+ ILC1-like cells in AML patients for whom alloreactive NK cell donors cannot be found. Future studies comparing the activity of anti-NKG2A antibodies on CD56+ ILC1-like cells and NKs in AML patients with HLA-E+ and HLA-E− blasts will provide valuable insights on this regard.

Furthermore, our data show that in vitro removal of leukemic blasts contributes to the recovery of TRAIL expression in CD56+ ILC1-like cells. This observation might partially explain the in vivo restored expression of TRAIL in CD56+ ILC1-like cells in AML patients during remission. It has been recently reported that TGF-β controls TRAIL expression in salivary gland ILCs,45 whereas it has been previously reported that leukemic-blast derived microvesicles containing TGF-β1 inhibit TGF-β–receptor expressing immune cells in AML.46 Our findings that TGF-β1 in vitro induces the downregulation of TRAIL and NKp30 in CD56+ ILC1-like cells and that elevated TGF-β1 concentrations are associated with patients’ poor survival suggest that blocking TGF-β1 using small molecule inhibitors, such as galunisertib, might restore the CD56+ ILC1-like cell activity. However, future studies directly assessing the impact of TGF-β1 inhibitors on HDs and AML patients’ CD56+ ILC1-like cell cytotoxicity should be performed to confirm these correlative observations. Then, coadministration with anti-NKG2A antibodies might heighten the therapeutic benefits with rather favorable toxicity profiles as suggested by preclinical studies using combinations of TGF-βRI inhibition and checkpoint blockade.47 Furthermore, AML blasts have been shown to impair NK cell functions in AML patients through the secretion of AhR ligands.38 Our results argue that these ligands also partially impair CD56+ ILC1-like cell functions and might thus be involved in their decreased cytotoxicity in AML patients.

It has been reported that NKp46 triggers TRAIL expression in ILC1 in mice.48 However, in AML patients, we found no correlation between NKp46 and TRAIL expression in CD56+ ILC1-like cells (n = 8, P = .76), suggesting that distinct mechanisms underlie the regulation of receptor expression across species. The observed downregulation of activating receptors might be due to the long-lasting contact with their ligands,49 ultimately leading to CD56+ ILC1-like cell dysfunction. Alternatively, the overexpression of inhibitory receptors might contribute to CD56+ ILC1-like cell impaired function in AML patients. Although the expression of “common” immune checkpoints (eg, PD-1, CTLA-4, and BTLA) was absent in CD56+ ILC1-like cells from both the HDs and the patients, we observed significant levels of IL-1R8 in the HDs’ CD56+ ILC1-like cells (data not shown). IL-1R8 represents a novel immune checkpoint that was shown to negatively regulate NK cell maturation and antiviral and antitumor functions in mice, but it has not been reported in human ILCs to date.50 Future studies are needed to assess the impact of this receptor on human CD56+ ILC1-like cells.

Finally, given that the CD56 marker is a major discriminator of the CD56+ ILC1-like cell phenotype from that of helper ILCs, we hypothesized and confirmed that CD56+ ILC1-like cells are present in the CD3−CD56+-enriched NK cell fractions infused in AML patients. Since several studies have demonstrated that patients’ responses can be influenced by the composition of the NK cell graft,51 the impact of the CD56+ ILC1-like cell presence on parameters, such as relapse and survival, urgently needs to be investigated. In that regard, we envisage to characterize and quantify CD56+ ILC1-like cells in NK preparations that will be transferred to patients to determine the correlation with the clinical outcome (Clinical trial Bologna NKAML Trial 035/2017/0/Sper). Triggering the CD56+ ILC1-like cell compartment in these enriched fractions by anti-NKG2A, monoclonal antibodies could potentiate their KIR-independent antileukemic action. Alternatively, enriching NK fractions with the CD56+ ILC1-like cell compartment or ex vivo expanding CD56+ ILC1-like cells similarly to NK cell expansion, which has been proven to be safe and feasible,52 might help obtain better clinical results without the need of KIR-mismatch.

Overall, this work highlights the importance of improving our knowledge of this CD127+ c-Kit− CD56+ population to help select the best donors for patients and maximize the effects of immunotherapy in AML.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the patients for their dedicated collaboration and HDs for their blood and tissue donations. They thank A. G. Freud and E. M. Mace for their very insightful discussions; G. Coukos, D. Vanheke, M. Girotra, and C. Corrascosa for providing the human fetal samples and humanized mice blood samples; D. Pende (Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico, Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, Genoa, Italy) for providing the masking antibodies against NKp30 (clone F252) and P. Schneider for providing the TRAIL decoy receptor; Karl-Johan Malmberg for providing the HLA-E transfected 721.221 cell line; Hergen Spits for providing the OP9 stromal cells; A. Cornu for technical assistance; and the expertise and assistance of the Flow Cytometry Facility at the University of Lausanne and of the Dean’s Flow Cytometry Center of Research Excellence at Mount Sinai.

This work was supported by the following funding: the Swiss National Science Foundation grant Ambizione PZOOP3_161459 (C.J.), MHV PMPDP3_164447 (S.T.), SNSF project grant 31003A_163204 (P.-C.H.), the Swiss Cancer League grant KFS-3710-08-2015-R (C.J.) and KFS-3949-08-2016 (P.-C.H.), the Fondation Emma Muschamp, the Novartis Foundation for Medical-Biological Research 17C154, the Fondation pour la Recherche Nuovo-Soldati (C.J.), ProFemmes UNIL (S.T.), the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro IG 2017 Id. 20312 and 5×1000-21147 (E.M.), Fondazione Cariplo 2015/0603 (D.M.), Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro IG 21567 (D.M.), and Intramural Research Funding of Istituto Clinico Humanitas (5×1000 project) (D.M.). E.B. is recipient of a doctoral fellowship from the University of Milan.

Authorship

Contribution: B.S., A.G.-C., R.L., G.V., D.F.R., S.T., and C.J. performed the experiments; V.S., M.R., C.R., P.T., E.B., E.-M.J., C.C., M.H., A. Schulz, K.M., A.T., S.S., A.O., M.G.D.P., D.M., A.C., P.-C.H., and A. Steinle provided reagents and patient samples; B.S., T.W., M.S., and D.G. conducted the analysis of the RNA sequencing data; A.H., P.J., and E.M. interpreted and discussed the results; and B.S., A.G.-C., P.R., S.T., and C.J. designed the research, analyzed the experiments, discussed the results, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Camilla Jandus, University of Lausanne, Chemin des Boveresses 155, 1066 Epalinges, Switzerland; e-mail: camilla.jandus@gmail.com; and Sara Trabanelli, University of Lausanne, Chemin des Boveresses 155, 1066 Epalinges, Switzerland; e-mail: sara.trabanelli@gmail.com.

References

Author notes

A.G.-C. and R.L. contributed equally to this study as joint second authors.

S.T. and C.J. contributed equally to this study as joint last authors.

The data for this study have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive at EMBL-EBI under accession number PRJEB34980 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/data/view/PRJEB34980).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![Identification of a CD56+ILC1-like population with NK properties that is impaired in AML patients at diagnosis. (A-B) Representative density plots of the extracellular flow cytometry panel used to identify the cNK cell subsets (A) and the ILC subsets (B) in peripheral blood (PB) mononuclear cells (PBMCs; ILC1 as CRTH2− c-Kit− CD56−, ILC2 as CRTH2+ c-Kit+/− CD56+/−, ILCP as CRTH2− c-Kit+ CD56+/−, and cNKs as CD16− CD56bright and CD16+ CD56dim).21,22 Lineage markers used for the “helper” ILC staining include CD3, CD4, CD8, CD14, CD15, CD16, CD19, CD20, CD33, CD34, CD203c, and FcεRIα; same lineage markers, except for CD16, were used for the cNK staining. (C) CD127, CD56, CD16, CRTH2, c-Kit fluorescence intensity on ILC and NK subsets were concatenated from 5 HDs and analyzed with t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE). c-Kit, CD127, CD56, CD16 expression levels on ILC1, CD56+ ILC1-like cells and NKs are represented in panel D. Representative gating (E) and quantification of CD56+ ILC1-like cell and cNK proportions among lymphocytes in blood from HDs and AML patients at diagnosis (F) (CD56+ ILC1-like cells: HD, n = 47; AML patients: n = 60; cNKs: HD: n = 12, AML: n = 18). (G) Summary of the results of the total ILC proportions and ILC1, ILC2, ILCP, and CD56+ ILC1-like cell subset frequencies among the total ILCs in HD peripheral blood (N = 47, age median 48, interquartile range 31 to 64). (H) Correlation between ILC subsets’ relative frequencies in blood and age (cord blood: n = 9, children: n = 6, [3 to 12] years old, adults: n = 47, age mean 48). (I) CD56+ ILC1-like cell relative frequencies among the total ILCs in tissues from healthy adults (n = 3-18). Spearman correlations were used in panel H. One dot = 1 donor. Mann-Whitney unpaired U tests were used in panel F. ****P < .0001. BM, bone marrow; LN, lymph node. ns, not significant.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/3/22/10.1182_bloodadvances.2018030478/6/m_advances030478f1-1.png?Expires=1764968291&Signature=it6m55zlldzfZK4arZNGpDcbdzq~OwQ5qoi1w21Z~FnQjWoR2O48Jc36pM3cxPmdnSag6Kni7~gqyGn2EoVq1G2h0hj9wTtmS3CP8fThY8-oF7pLY8m4urfO7R85TP~zrhjyaiFo0f3hAe7GOdFqT1FBPStc82KDJQ7ZMqGso~NSRk~vSO~q-Xof4cjx1hUfsT7BFfhweBJbydio~o7G20Ui62C0cA2M4zNVo9pMu-PM-HWBMlBVvSTmvTItTcW863QUswMjWRiBKWDZaTRsMfru7GSXQRsfy6nHtnwwo8s-Cox0AQhFj9Ph5njVbgor88fL1ZWTRblLq~WH81YddA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Identification of a CD56+ILC1-like population with NK properties that is impaired in AML patients at diagnosis. (A-B) Representative density plots of the extracellular flow cytometry panel used to identify the cNK cell subsets (A) and the ILC subsets (B) in peripheral blood (PB) mononuclear cells (PBMCs; ILC1 as CRTH2− c-Kit− CD56−, ILC2 as CRTH2+ c-Kit+/− CD56+/−, ILCP as CRTH2− c-Kit+ CD56+/−, and cNKs as CD16− CD56bright and CD16+ CD56dim).21,22 Lineage markers used for the “helper” ILC staining include CD3, CD4, CD8, CD14, CD15, CD16, CD19, CD20, CD33, CD34, CD203c, and FcεRIα; same lineage markers, except for CD16, were used for the cNK staining. (C) CD127, CD56, CD16, CRTH2, c-Kit fluorescence intensity on ILC and NK subsets were concatenated from 5 HDs and analyzed with t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE). c-Kit, CD127, CD56, CD16 expression levels on ILC1, CD56+ ILC1-like cells and NKs are represented in panel D. Representative gating (E) and quantification of CD56+ ILC1-like cell and cNK proportions among lymphocytes in blood from HDs and AML patients at diagnosis (F) (CD56+ ILC1-like cells: HD, n = 47; AML patients: n = 60; cNKs: HD: n = 12, AML: n = 18). (G) Summary of the results of the total ILC proportions and ILC1, ILC2, ILCP, and CD56+ ILC1-like cell subset frequencies among the total ILCs in HD peripheral blood (N = 47, age median 48, interquartile range 31 to 64). (H) Correlation between ILC subsets’ relative frequencies in blood and age (cord blood: n = 9, children: n = 6, [3 to 12] years old, adults: n = 47, age mean 48). (I) CD56+ ILC1-like cell relative frequencies among the total ILCs in tissues from healthy adults (n = 3-18). Spearman correlations were used in panel H. One dot = 1 donor. Mann-Whitney unpaired U tests were used in panel F. ****P < .0001. BM, bone marrow; LN, lymph node. ns, not significant.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/3/22/10.1182_bloodadvances.2018030478/6/m_advances030478f1-2.png?Expires=1764968291&Signature=y-hE6U~03SJtUd1rQemLP2~B8oIM5E0C4muwm61~kHvbw67STY5ORmgA~HQA5-peCXQW4fHMGtqo-edIhtXPSh2COehp8fERtpAAGPY54shzbHzmovgTQoYY~D3vppibUpmZQI4Al5CHLhEy7tz6sbondz8WiTVtGM-e0dcZmmWYD6CakdGjBNFPaFJgvYCBJ~phpJHkKIbCKR--YTkTQjWpE5fEbmqQAJP2pXWTA~MLMGPH2Ee2w6uyVsfYFGMtobJLiRQSADCVdJ~Ql8ZFyTthIKBiDs6Yxe-0UbQeqSFlnt7x4XCEqVvHmF1l7TXEQF2dWTAK8om~up00TJlLwA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)