Key Points

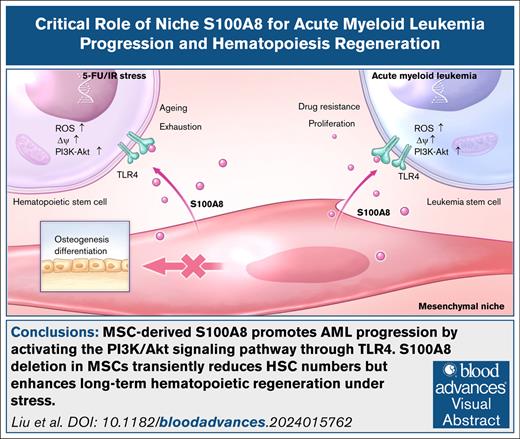

MSC-derived S100A8 promotes AML progression by activating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway through Toll-like receptor 4.

S100A8 deletion in MSCs transiently reduces HSC numbers but enhances long-term hematopoietic regeneration under stress.

Visual Abstract

The role of inflammation in regulating acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and stressed hematopoiesis is significant, although the molecular mechanisms are not fully understood. Here, we found that mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) had dysregulated expression of the inflammatory cytokine S100A8 in AML. Upregulating S100A8 in MSCs increased the proliferation of AML cells in vitro. In contrast, removing S100A8 from MSCs in the murine MLL-AF9 AML model resulted in longer survival and less infiltration of leukemia cells. S100A8 binds to the Toll-like receptor 4 on leukemia cells, activating the PI3K/Akt pathway. In addition, removing S100A8 from MSCs caused a temporary decline in hematopoietic stem cell (HSCs) numbers, but facilitated long-term hematopoietic recovery under stress. Furthermore, S100A8 inhibited MSC differentiation into osteoblasts and reduced the expression of osteopontin, which is required for supporting HSCs. Our findings highlight the importance of niche inflammation in promoting AML development while impeding hematopoietic regeneration.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) establish themselves in a safe bone marrow (BM) environment composed of a complex, interconnected network of hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells that play critical roles in regulating HSC dormancy, proliferation, and migration.1 Under normal circumstances, hematopoiesis strikes a delicate balance between expansion and quiescence to achieve maximum production output.2,3 Both extrinsic1 and intrinsic factors4 act hard to maintain this homeostasis while also allowing for adaptive responses5 and recovery6 in the face of emergencies such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a genetically heterogeneous disease characterized by clonal expansion of myeloid blasts evolved from hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs).7 Adequate hematopoiesis regeneration under stress determines AML outcomes and is governed by BM HSC niche.8,9

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) are a pivotal component of the BM niche,10-14 which forms various BM components, such as adipogenic, osteogenic, and chondrogenic lineages.15,16 Inflammation influences HSC activity and AML development through niche-dependent interactions, as demonstrated by a growing body of research.17-20 In response to external stimulation, BM niche cells release factors that promote myelopoiesis.21-23 However, the precise mechanisms and roles of proinflammatory factors in the mesenchymal niche are poorly understood.

S100A8, a member of the S100 protein family, typically forms a heterodimer with S100A9, another family member. Together, S100A8/A9 functions as a potent inflammatory complex, regulating Ca2+ balance, apoptosis, cell migration, proliferation, differentiation, energy metabolism, and inflammatory responses. The S100A8/A9 heterodimer represents the predominant form, accounting for up to 45% of all cytosolic proteins in neutrophils and ∼40-fold less in monocytes.24,25 It has been reported that S100A8 and S100A9 are highly expressed in AML cells and are involved in disease progression and drug resistance.26,27 Moreover, recent research has found elevated levels of BM MSC–derived S100A8 in patients with myeloid neoplasms such as myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and myeloproliferative neoplasm.28-30 Escalating S100A8/A9 expression in MSCs is associated with increased MSC proliferation during the early osteogenic differentiation phase, whereas mature osteogenesis is inhibited, resulting in disruption of trabecular bone structure.29,31 The effects of S100A8/A9 on stromal cells are similar to the remodeling of the BM microenvironment observed in AML. Notably, MSC-derived S100A8/A9 has been linked to MDS disease progression by causing mitochondrial dysfunction, eliciting oxidative stress responses, and impairing DNA damage repair in HSPCs.29 However, the specific role of MSC-derived S100A8/A9 in AML progression has not been previously reported.

Given that a previous study has reported that AML cell–derived S100A8 exerts opposite, rather than synergistic, effects with S100A9 on disease progression,27 we focused on the effects of aberrant expression of MSC-derived S100A8 on HSC regeneration and AML development in this study.

Materials and methods

Mice

S100A8flox/flox mice were obtained from GemPharmatech LLC. Prx1-Cre mice were purchased from Biocytogen Pharmaceuticals Co Ltd (Beijing, China). C57BL/6 and B6.SJL mice were bought from GemPharmatech LLC. S100A8flox/flox mice were crossed with Prx1-Cre mice to produce Prx1-Cre; S100A8flox/flox and S100A8flox/flox mice. Mice aged 8 to 12 weeks were used in all experiments. All animal procedures followed the animal care guidelines approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at Zhongnan Hospital and Wuhan University.

Flow cytometry analysis and cell sorting

Mice BM and peripheral blood (PB) samples were prepared as described previously.32 Phenotypic analysis of lineage cells, HSPCs, leukemia stem cells (LSCs), leukemic granulocyte/macrophage progenitor populations (L-GMPs), MSCs, and osteoblasts (OBCs) was performed according to previous studies.33 LSK cells (Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+), long-term HSCs (LT-HSCs; Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+CD34–Flt3–), short-term HSCs (ST-HSCs; Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+CD34+Flt3–), MPPs (multipotent progenitors; Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+CD34+Flt3+), GMPs (Lin–Sca-1–c-Kit+CD16/32hiCD34hi), common myeloid progenitors (Lin–Sca-1–c-Kit+CD16/32MedCD34hi), megakaryocyte/erythroid progenitors (Lin–Sca-1–c-Kit+CD16/32–CD34–), CLPs (common lymphoid progenitors; Lin–IL-7R+Sca-1Medc-KitMed), LSCs (YFP+CD117+Gr-1–), L-GMPs (IL-7R/Lin–YFP+c-KithiCD34+CD16/32hi), MSCs (CD45–TER119–CD31–LepR+), and OBCs (CD45–TER119–CD31–CD166+Sca-1–) were analyzed by flow cytometry. Immature cells were obtained by sorting mouse HSPC and human LSCs with CD117 MicroBeads and CD34 MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). The antibody details are provided in supplemental Table 1.

Measurement of ROS

The intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) were measured using 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate or CellROX Deep Red Reagent staining. Briefly, cells were incubated with HSC or LSC marker antibodies for 30 to 45 minutes before being treated with 10-μM 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (Beyotime; S0033S) or CellROX Deep Red Reagent (Invitrogen; C10422) for 10 minutes at 37°C in the dark. After incubation, the cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline and analyzed by flow cytometry. An increase in fluorescence intensity indicates elevated ROS levels.

TMRE staining

Mitochondrial membrane potential was identified by tetramethylrhodamine, ethyl ester (TMRE; Beyotime; C2001S), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, cells were incubated with HSC or LSC marker antibodies for 30 to 45 minutes, stained with 50-nM TMRE for 10 minutes, and then analyzed using flow cytometry.

Statistics

All experiments were performed in triplicate, with at least 3 replicates in each experiment. The significance of differences between the 2 groups was assessed using unpaired 2-tailed Student t tests. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. Overall survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method, with log-rank tests used for comparisons. Details of other experimental procedures are described in the supplemental Methods (∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001).

Samples from patients with AML and healthy donors

All BM specimens from patients with AML and healthy donors were obtained with informed consent from Zhongnan Hospital and Wuhan University, respectively. All studies involving human samples were approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhongnan Hospital and Wuhan University.

Results

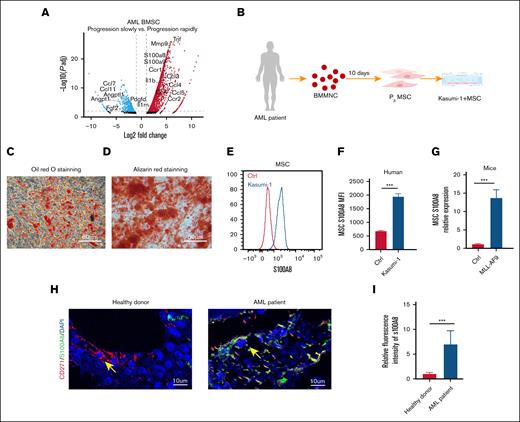

Expression of MSC-derived S100A8 increased in AML

In our previous study, we found a significant increase in the expression of BM MSC–derived S100A8 in a cohort of rapidly advancing murine models of AML33 (Figure 1A), suggesting that the aberrant expression of MSC-derived S100A8 may be involved in the regulation of leukemic disease progression and warrants further functional investigation. Here, we validated the expression of S100A8 in MSCs derived from BM with AML status. Volunteer-derived BM mononuclear cells were obtained and in vitro cultured to produce human BM MSCs (Figure 1B). MSC marker expression and differentiation functions were validated (supplemental Figure 1; Figure 1C-D). After 48 hours of cocultivation with leukemic cells, MSCs showed an increase in S100A8 expression (Figure 1E-F). Consistently, MSC-derived S100A8 expression in MLL-AF9 AML mice was significantly higher than that in normal mice (Figure 1G). Furthermore, our analysis of human BM sections showed very little expression of S100A8 in healthy human MSCs, whereas MSCs derived from patients with AML expressed a lot of S100A8 (Figure 1H-I). The data presented above support the aberrant expression of S100A8 in the presence of AML, implying that S100A8 may be involved in AML progression.

Expression of MSC-derived S100A8 under leukemic state. (A) Transcriptome sequencing data compare the expression of cytokines in MSC-derived AML mice with rapid vs slow disease progression. (B) Flowchart of coculture of patient-derived BM MSC with leukemic cells Kasumi-1. (C) Identify the adipose differentiation capacity of MSC by Oil Red O staining. (D) Identifying the osteogenic differentiation capacity of MSC by Alizarin red staining. (E) Flow plots of representative fluorescence intensity of S100A8 in MSC coculture with Kasumi-1 and control MSC. (F) Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of S100A8 in MSCs after coculture with Kasumi-1 cells (n = 3). (G) Expression of S100A8 in BM MSCs from MLL-AF9 mice and normal mice (n = 5). (H-I) Representative immunofluorescence images of human BM sections from a healthy donor and a patient with AML stained for CD271 (red), S100A8 (green), and DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; blue), along with quantitative analysis of S100A8 expression based on confocal microscopy (scale bars, 10 μm; n = 6). ∗∗∗P < .001. Ctrl, control; MNC, mononuclear cells.

Expression of MSC-derived S100A8 under leukemic state. (A) Transcriptome sequencing data compare the expression of cytokines in MSC-derived AML mice with rapid vs slow disease progression. (B) Flowchart of coculture of patient-derived BM MSC with leukemic cells Kasumi-1. (C) Identify the adipose differentiation capacity of MSC by Oil Red O staining. (D) Identifying the osteogenic differentiation capacity of MSC by Alizarin red staining. (E) Flow plots of representative fluorescence intensity of S100A8 in MSC coculture with Kasumi-1 and control MSC. (F) Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of S100A8 in MSCs after coculture with Kasumi-1 cells (n = 3). (G) Expression of S100A8 in BM MSCs from MLL-AF9 mice and normal mice (n = 5). (H-I) Representative immunofluorescence images of human BM sections from a healthy donor and a patient with AML stained for CD271 (red), S100A8 (green), and DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; blue), along with quantitative analysis of S100A8 expression based on confocal microscopy (scale bars, 10 μm; n = 6). ∗∗∗P < .001. Ctrl, control; MNC, mononuclear cells.

MSC-derived S100A8 deletion is dispensable for normal hematopoiesis

To fully understand the role of S100A8 in leukemogenesis, MSC-specific S100A8 knockout (Prx1-Cre+/–;S100A8flox/flox) mice and control mice were created (Prx1-Cre–/–;S100A8flox/flox) by crossing S100A8flox/flox mice with Prx1-Cre mice (supplemental Figure 2). We first examined the functional role of MSC-derived S100A8 in normal hematopoiesis. We discovered that removing S100A8 had no discernible effect on the frequencies and numbers of HSPCs and lineage cells (supplemental Figure 3), indicating that MSC-derived S100A8 was not required for homeostatic hematopoiesis in mice.

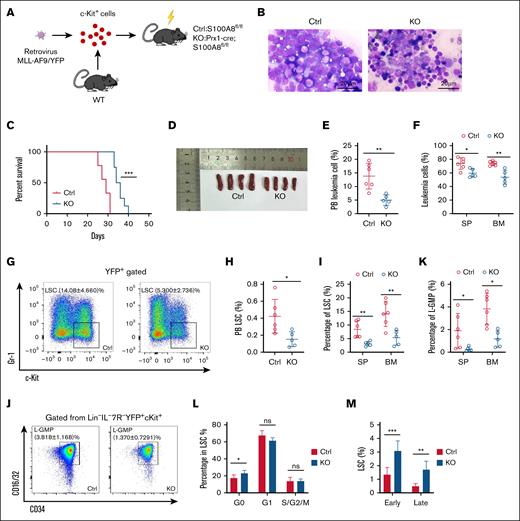

MSC-derived S100A8 drives murine AML progression and maintains LSC function

MLL-AF9–induced murine AML model was constructed with S100A8 knockout and control mice as recipients (Figure 2A-B). S100A8 deletion significantly improved survival rate and reduced leukemic burden in AML mice (Figure 2C; supplemental Figure 4). Not surprisingly, S100A8 knockout recipients had lower spleen (SP) weights than controls (Figure 2D). Furthermore, we found that S100A8 knockout recipients had a significantly lower ratio of YFP+ leukemic cells (Figure 2E-F), as well as lower malignant cell counts in (supplemental Figure 5A-B) in the PB, SP, and BM. Furthermore, the percentages (Figure 2G-I) and numbers (supplemental Figure 5C-D) of LSCs (YFP+c-Kit+Gr-1– cells) in PB, SP and BM were significantly reduced after S100A8 deletion, as were L-GMPs (IL-7R/Lin–YFP+c-KithiCD34+CD16/32hi) in SP and BM (Figure 2J-K; supplemental Figure 5E). Finally, we examined the characteristics of LSCs in a murine AML model, and we discovered that S100A8 knockout recipients had more G0 phase cells and higher apoptosis rates than control mice (Figure 2L-M). Collectively, we can reasonably conclude that S100A8 plays an important role in promoting the maintenance of LSCs.

Effect of S100A8 deletion in MSCs on disease progression and LSCs in MLL-AF9 leukemic mice. (A) A flow diagram of the MLL-AF9 leukemia model, with S100A8-deficient and control mice as recipients. (B) Leukemic cell infiltration revealed by BM Wright-Giemsa staining in S100A8-deficient and control MLL-AF9 mice. (C) Survival of MLL-AF9 mice in the S100A8-deficient and control groups (n = 8-9). (D) SP size of MLL-AF9 mice in the S100A8-deficient and control groups (n = 4). (E) The proportion of PB leukemia cells in S100A8-deficient and control MLL-AF9 mice (n = 5-6). (F) The proportion of SP and BM leukemia cells in S100A8-deficient and control MLL-AF9 mice (n = 5-7). (G) A flow representation of BM LSCs (YFP+c-Kit+Gr-1–) in MLL-AF9 mice. (H) The proportion of PB LSCs in S100A8-deficient and control MLL-AF9 mice (n = 5-6). (I) Proportion of SP and BM LSCs in S100A8-deficient and control MLL-AF9 mice (n = 5-7). (J) Flow representation of BM L-GMPs (IL-7R/Lin–YFP+c-KithiCD34+CD16/32hi) in MLL-AF9 mice. (K) Proportion of L-GMPs of SP and BM of S100A8-deficient vs control MLL-AF9 mice (n = 5-7). (L) Cell cycle of BM LSCs in S100A8-deficient and control MLL-AF9 mice (n = 5-6). (M) Apoptosis of BM LSCs in S100A8-deficient and control MLL-AF9 mice (n = 6). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. Ctrl,control; KO, knockout; WT, wild-type.

Effect of S100A8 deletion in MSCs on disease progression and LSCs in MLL-AF9 leukemic mice. (A) A flow diagram of the MLL-AF9 leukemia model, with S100A8-deficient and control mice as recipients. (B) Leukemic cell infiltration revealed by BM Wright-Giemsa staining in S100A8-deficient and control MLL-AF9 mice. (C) Survival of MLL-AF9 mice in the S100A8-deficient and control groups (n = 8-9). (D) SP size of MLL-AF9 mice in the S100A8-deficient and control groups (n = 4). (E) The proportion of PB leukemia cells in S100A8-deficient and control MLL-AF9 mice (n = 5-6). (F) The proportion of SP and BM leukemia cells in S100A8-deficient and control MLL-AF9 mice (n = 5-7). (G) A flow representation of BM LSCs (YFP+c-Kit+Gr-1–) in MLL-AF9 mice. (H) The proportion of PB LSCs in S100A8-deficient and control MLL-AF9 mice (n = 5-6). (I) Proportion of SP and BM LSCs in S100A8-deficient and control MLL-AF9 mice (n = 5-7). (J) Flow representation of BM L-GMPs (IL-7R/Lin–YFP+c-KithiCD34+CD16/32hi) in MLL-AF9 mice. (K) Proportion of L-GMPs of SP and BM of S100A8-deficient vs control MLL-AF9 mice (n = 5-7). (L) Cell cycle of BM LSCs in S100A8-deficient and control MLL-AF9 mice (n = 5-6). (M) Apoptosis of BM LSCs in S100A8-deficient and control MLL-AF9 mice (n = 6). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. Ctrl,control; KO, knockout; WT, wild-type.

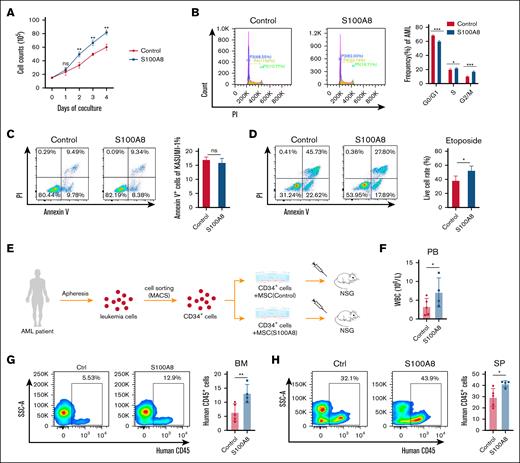

MSC-derived S100A8 is essential for human AML cell growth

To further validate the role of MSC-derived S100A8 in AML development, we performed an experiment in which S100A8 was overexpressed in human BM MSCs (supplemental Figure 6) and then cocultured with the human AML cell line Kasumi-1. Overexpression of S100A8 in MSCs increased the growth of Kasumi-1 cells (Figure 3A) and facilitated their cell cycle progression (Figure 3B). Furthermore, overexpression of S100A8 did not significantly alter the rate of apoptosis (Figure 3C), but it increased the resistance of Kasumi-1 cells to etoposide (Figure 3D). Then, leukemia cells from patients with AML were used, and CD34+ leukemia cells were enriched using magnetic-activated cell sorting. CD34+ leukemia cells were cocultured with S100A8-overexpressing and control MSCs for 48 hours. Then, leukemia cells were transplanted into immunodeficient mice, along with the MSC suspension (Figure 3E). After 30 days, white blood cell count in S100A8-overexpressing mice was higher than in the control group, as were the levels in the BM and SP (Figure 3F-H). Finally, these findings indicate that S100A8 plays a role in the development and drug resistance of human AML cells.

Effect of S100A8 overexpression in MSCs on the growth and drug resistance of human AML cells in vitro. (A) Growth curve of Kasumi-1 cells cocultured with MSCs overexpressing S100A8 or control MSCs (n = 3). (B) Effects of S100A8 overexpression on the cell cycle of Kasumi-1; flow diagram (left) and statistical plots (right; n = 3). (C) S100A8 overexpression affects apoptosis in Kasumi-1 cells, with flow representative plots (left) and statistical plots (right; n = 3). (D) Effect of S100A8 overexpression on etoposide (2 μM) resistance in Kasumi-1 cells, with flow diagram (left) and statistical plots (right; n = 3). (E) Flow of patient-derived xenograft (PDX) modeling after coculture of patient-derived AML cells with MSCs. (F) PB white blood cell (WBC) counts in PDX mice with S100A8 overexpression vs the control group (n = 4-5). (G) Percentage of BM leukemia cells of PDX mice in the S100A8 overexpression and control group (n = 4-5). (H) The percentage of SP leukemia cells in PDX mice with S100A8 overexpression vs the control group (n = 4-5). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. Ctrl, control; MACS, magnetic-activated cell sorting; ns, not significant; NSG, NOD scid gamma mice.

Effect of S100A8 overexpression in MSCs on the growth and drug resistance of human AML cells in vitro. (A) Growth curve of Kasumi-1 cells cocultured with MSCs overexpressing S100A8 or control MSCs (n = 3). (B) Effects of S100A8 overexpression on the cell cycle of Kasumi-1; flow diagram (left) and statistical plots (right; n = 3). (C) S100A8 overexpression affects apoptosis in Kasumi-1 cells, with flow representative plots (left) and statistical plots (right; n = 3). (D) Effect of S100A8 overexpression on etoposide (2 μM) resistance in Kasumi-1 cells, with flow diagram (left) and statistical plots (right; n = 3). (E) Flow of patient-derived xenograft (PDX) modeling after coculture of patient-derived AML cells with MSCs. (F) PB white blood cell (WBC) counts in PDX mice with S100A8 overexpression vs the control group (n = 4-5). (G) Percentage of BM leukemia cells of PDX mice in the S100A8 overexpression and control group (n = 4-5). (H) The percentage of SP leukemia cells in PDX mice with S100A8 overexpression vs the control group (n = 4-5). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. Ctrl, control; MACS, magnetic-activated cell sorting; ns, not significant; NSG, NOD scid gamma mice.

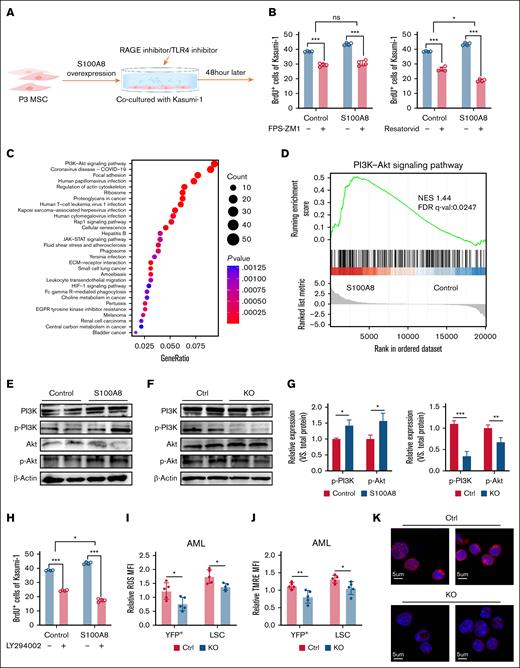

MSC-derived S100A8 regulates AML development via the TLR4/PI3K/Akt pathway

RAGE and Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) are the most common S100A8 receptors,34 and to investigate the mechanism by which S100A8 acts on leukemic cells, we added a RAGE inhibitor (FPS-ZM1) or a TLR4 inhibitor (resatorvid) to MSC and Kasumi-1 coculture systems. The addition of TLR4 inhibitors resulted in the most significant decrease in leukemic cell proliferation (Figure 4A-B), indicating that MSC-derived S100A8 acts primarily by binding leukemic cell TLR4. To delve deeper into the molecular mechanism, we conducted transcriptomic analyses. The results revealed notable differences in gene expression in Kasumi-1 cells between the group cocultured with overexpressed S100A8 and the control group, as well as significant alterations in the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway (Figure 4C-D). Western blot experiments revealed that phosphorylated PI3K and Akt protein levels were significantly higher in the S100A8 overexpression group but lower in the S100A8-deficient group (Figure 4E-G), and the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 significantly reduced leukemic cell proliferation (Figure 4H). A recent article reported that PI3K/Akt regulates oxidative stress to promote drug resistance in leukemia progression, and changes in the HIF-1 pathway were also revealed in our sequencing results35 (Figure 4C). We then examined ROS levels in LSCs. Flow cytometry analysis revealed a lower intracellular level of ROS in LSCs from S100A8 knockout mice than the control group (Figure 4I). TMRE staining was used to determine mitochondrial membrane potential. Flow cytometry analysis revealed a decrease in TMRE fluorescence in LSCs from S100A8 knockout mice compared to the control group (Figure 4J). Furthermore, DNA damage was found to be lower in BM cells from S100A8-deficient AML mice than control cells (Figure 4K). Overall, these findings showed that S100A8 promoted leukemia progression through TLR4/PI3K/Akt signaling.

Molecular mechanisms by which MSC-derived S100A8 promotes AML progression. (A) Flowchart of rescue experiment with RAGE inhibitor or TLR4 inhibitor added to the cocultivation system. (B) Effect of RAGE inhibitor (FPS-ZM1; 500 nM) or TLR4 inhibitor (resatorvid; 5 μM) treatment on leukemic cell proliferation in the S100A8 overexpression group (n = 4). (C) The cocultivation of MSCs with KASUMI-1 cells after S100A8 overexpression was followed by transcriptome sequencing of the Kasumi-1 cells (n = 3). Gene Ontology analysis of the signaling pathway of Kasumi-1 in the S100A8 overexpression group vs the control group. (D) Gene set enrichment analyses evaluating changes in Kasumi-1 of the S100A8 overexpression group compared to control group. (E) PI3K, Akt expression and its phosphorylation level in Kasumi-1 of the S100A8 overexpression group compared to control group. (F) PI3K, Akt expression, and its phosphorylation level in leukemic cells of S100A8-deficient and control AML mice. (G) Western blot analysis with protein quantification of P-PI3K and p-Akt (n = 4). (H) Effect of PI3K inhibitor (LY294002; 10 μM) treatment on leukemic cells proliferation in the S100A8 overexpression group (n = 4). (I) MFI of ROS in leukemic cells and LSCs in S100A8-deficient and control AML mice (n = 5). (J) MFI of TMRE in leukemic cells and LSCs in S100A8-deficient and control AML mice (n = 5). (K) Representative γ-H2AX images of BM cells of S100A8-deficient and control AML mice (scale bars, 20 μm; n = 5). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. Ctrl, control; FDR, false discovery rate; NES, normalized enrichment score; KO, knockout; q-val, q value.

Molecular mechanisms by which MSC-derived S100A8 promotes AML progression. (A) Flowchart of rescue experiment with RAGE inhibitor or TLR4 inhibitor added to the cocultivation system. (B) Effect of RAGE inhibitor (FPS-ZM1; 500 nM) or TLR4 inhibitor (resatorvid; 5 μM) treatment on leukemic cell proliferation in the S100A8 overexpression group (n = 4). (C) The cocultivation of MSCs with KASUMI-1 cells after S100A8 overexpression was followed by transcriptome sequencing of the Kasumi-1 cells (n = 3). Gene Ontology analysis of the signaling pathway of Kasumi-1 in the S100A8 overexpression group vs the control group. (D) Gene set enrichment analyses evaluating changes in Kasumi-1 of the S100A8 overexpression group compared to control group. (E) PI3K, Akt expression and its phosphorylation level in Kasumi-1 of the S100A8 overexpression group compared to control group. (F) PI3K, Akt expression, and its phosphorylation level in leukemic cells of S100A8-deficient and control AML mice. (G) Western blot analysis with protein quantification of P-PI3K and p-Akt (n = 4). (H) Effect of PI3K inhibitor (LY294002; 10 μM) treatment on leukemic cells proliferation in the S100A8 overexpression group (n = 4). (I) MFI of ROS in leukemic cells and LSCs in S100A8-deficient and control AML mice (n = 5). (J) MFI of TMRE in leukemic cells and LSCs in S100A8-deficient and control AML mice (n = 5). (K) Representative γ-H2AX images of BM cells of S100A8-deficient and control AML mice (scale bars, 20 μm; n = 5). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. Ctrl, control; FDR, false discovery rate; NES, normalized enrichment score; KO, knockout; q-val, q value.

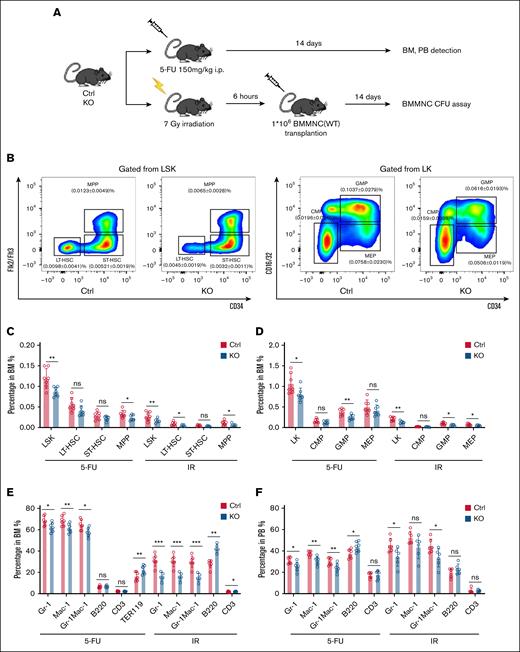

MSC-derived S100A8 deletion inhibits HSC expansion under short-term stress

Impairment of normal hematopoiesis and leukemia progression are closely related processes during leukemia development and are regulated by the BM niche.36 To investigate how MSC-derived S100A8 influences hematopoiesis under leukemic conditions, we used the MLL-AF9 mouse model. S100A8 knockout recipients exhibited increased numbers of nonleukemic hematopoietic progenitor cells and mature myeloid cells compared to control mice (supplemental Figure 7), suggesting that S100A8 may regulate hematopoiesis in response to leukemic stress. Interestingly, we found that S100A8 was significantly upregulated in MSCs after 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and irradiation (IR) exposure (supplemental Figure 8A-C). As expected, the frequencies and numbers of LSKs (Lin–c-Kit+Sca-1+), LT-HSCs, and ST-HSCs were nearly all lower in S100A8–/– BM at day 14 after 5-FU treatment and IR exposure than in controls (Figure 5A-C; supplemental Figure 8D). Notably, 5-FU treatment and IR exposure resulted in lower percentages and numbers of GMPs, whereas decreased megakaryocyte/erythroid progenitors were observed in S100A8–/– mice after IR exposure, whereas common myeloid progenitors showed no significant difference between the 2 groups after 5-FU treatment and IR exposure (Figure 5D; supplemental Figure 8E). Consistent with these findings, S100A8–/– mice had significantly fewer mature myeloid cells after 5-FU and IR treatment in both BM and PB (Figure 5E-F; supplemental Figure 8F-G). Overall, our findings indicate that S100A8 promotes HSC expansion under short-term hematopoietic stresses.

Effect of MSC-derived S100A8 deletion on 5-FU and IR stress hematopoiesis. (A) Construction of the 5-FU and IR stress model. (B) A representative flow pattern of HSPC in BM. (C) Proportion of BM HSC in the S100A8-deficient and control groups 14 days after 5-FU and IR treatment (n = 6-7). (D) The proportion of BM hematopoietic progenitors in the S100A8-deficient and control groups 14 days after 5-FU and IR treatment (n = 6-7). (E) The percentage of BM mature lineage cells in the S100A8-deficient and control groups 14 days after 5-FU and IR (n = 6-7). (F) Proportion of PB mature lineage cells in the S100A8-deficient and control groups 14 days after 5-FU and IR treatment (n = 6-7). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. Ctrl, control; i.p., intraperitoneal; KO, knockout.

Effect of MSC-derived S100A8 deletion on 5-FU and IR stress hematopoiesis. (A) Construction of the 5-FU and IR stress model. (B) A representative flow pattern of HSPC in BM. (C) Proportion of BM HSC in the S100A8-deficient and control groups 14 days after 5-FU and IR treatment (n = 6-7). (D) The proportion of BM hematopoietic progenitors in the S100A8-deficient and control groups 14 days after 5-FU and IR treatment (n = 6-7). (E) The percentage of BM mature lineage cells in the S100A8-deficient and control groups 14 days after 5-FU and IR (n = 6-7). (F) Proportion of PB mature lineage cells in the S100A8-deficient and control groups 14 days after 5-FU and IR treatment (n = 6-7). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. Ctrl, control; i.p., intraperitoneal; KO, knockout.

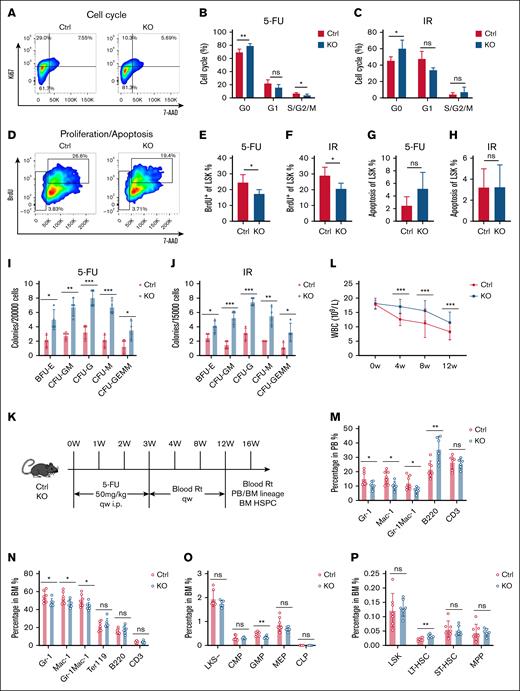

Deletion of MSC-derived S100A8 increases HSC quiescence under hematopoietic stress

Given the observation that S100A8 causes short-term expansion of HSCs during hematopoietic stress, we hypothesized that S100A8 may modulate HSC quiescence. As expected, HSCs from S100A8 knockout mice had a higher percentage in the G0 phase but a decreasing trend in the G1 and S/G2/M phases after 5-FU treatment and IR exposure (Figure 6A-C). Furthermore, an in vivo 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation assay revealed that S100A8 deletion reduced proliferation of HSCs in mice after 5-FU and IR challenge, whereas apoptosis rates were comparable between S100A8 knockout and control HSCs (Figure 6D-H). These findings suggest that S100A8 promotes hyperactivation of HSCs in response to stress stimuli. To assess the functional impact of S100A8 on HSCs, we used a colony formation assay. The results showed that the number of colonies formed in the group with S100A8 deletion was significantly higher after treatment with 5-FU and IR (Figure 6I-J). These findings suggest that S100A8 promotes the entry of HSCs into the proliferation cycle as a means of short-term hematopoietic recovery under stressful conditions, albeit at the expense of impairing the general function of HSCs.

Effect of S100A8 deficiency on the cell cycle and function of HSCs under stress. (A) Flow representation of the LSK cell cycle. (B-C) Cell cycle of LSK cells in the S100A8-deficient and control groups after 14 days of 5-FU treatment (B) and IR exposure (C) (n = 4-5). (D) A flow representation of proliferation and apoptosis of LSK cells. (E-F) Proliferation of LSK cells in the S100A8-deficient and control group after 14 days of 5-FU treatment (E) and IR exposure (F) (n = 4–5). (G-H) Apoptosis of LSK cells in the S100A8-deficient and control group after 14 days of 5-FU treatment (G) and IR exposure (H) (n = 4–5). (I-J) The total number of BM colonies in the S100A8-deficient and control groups after 14 days of 5-FU treatment (I) and IR exposure (J) (n = 4). (K) Flow of 5-FU treatment for long-term hematopoietic model development. (L) Dynamic changes in PB WBC in S100A8 deletion and control groups treated with 5-FU (n = 7-8). (M-N) The proportion of PB (M) and BM (N) mature myeloid cells and lymphocytes 16 weeks after the first 5-FU treatment (n = 6–7). (O) Proportion of BM HPCs at 16 weeks after 5-FU treatment (n = 6-7). (P) Proportion of BM HSCs 16 weeks after 5-FU treatment (n = 6-7). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. BFU-E, burst-forming unit–erythroid; CFU-F, colony-forming unit–fibroblast; CFU-G, colony-forming unit–granulocyte; CFU-GM, colony-forming unit–granulocyte/macrophage; CFU-GEMM, colony-forming unit–granulocyte/erythrocyte/macrophage/megakaryocyte; i.p., intraperitoneal; Rt, routine test; qw, once weekly.

Effect of S100A8 deficiency on the cell cycle and function of HSCs under stress. (A) Flow representation of the LSK cell cycle. (B-C) Cell cycle of LSK cells in the S100A8-deficient and control groups after 14 days of 5-FU treatment (B) and IR exposure (C) (n = 4-5). (D) A flow representation of proliferation and apoptosis of LSK cells. (E-F) Proliferation of LSK cells in the S100A8-deficient and control group after 14 days of 5-FU treatment (E) and IR exposure (F) (n = 4–5). (G-H) Apoptosis of LSK cells in the S100A8-deficient and control group after 14 days of 5-FU treatment (G) and IR exposure (H) (n = 4–5). (I-J) The total number of BM colonies in the S100A8-deficient and control groups after 14 days of 5-FU treatment (I) and IR exposure (J) (n = 4). (K) Flow of 5-FU treatment for long-term hematopoietic model development. (L) Dynamic changes in PB WBC in S100A8 deletion and control groups treated with 5-FU (n = 7-8). (M-N) The proportion of PB (M) and BM (N) mature myeloid cells and lymphocytes 16 weeks after the first 5-FU treatment (n = 6–7). (O) Proportion of BM HPCs at 16 weeks after 5-FU treatment (n = 6-7). (P) Proportion of BM HSCs 16 weeks after 5-FU treatment (n = 6-7). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. BFU-E, burst-forming unit–erythroid; CFU-F, colony-forming unit–fibroblast; CFU-G, colony-forming unit–granulocyte; CFU-GM, colony-forming unit–granulocyte/macrophage; CFU-GEMM, colony-forming unit–granulocyte/erythrocyte/macrophage/megakaryocyte; i.p., intraperitoneal; Rt, routine test; qw, once weekly.

To see whether S100A8 affects long-term HSC maintenance, we gave S100A8 knockout and control mice 4 injections of 5-FU (50 mg/kg) once per week. The hematopoietic phenotypes of S100A8 knockout and control mice were then assessed at 4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks (Figure 6K). The results revealed a significant increase in white blood cell count 4 weeks after S100A8 deletion (Figure 6L). Surprisingly, S100A8 knockout mice had lower percentages of mature PB and BM myeloid cells than control mice (Figure 6M-N), as well as reduced frequencies of GMPs (Figure 6O). However, it is worth noting that the proportion and absolute number of LT-HSCs were higher in the S100A8-deficient group than in controls (Figure 6P). This finding suggests that S100A8 reduces HSCs and myeloid differentiation bias in a prolonged stressful environment, causing HSCs to exhibit a senescent phenotype.

To determine whether S100A8 contributes to HSC senescence under prolonged stress, we assessed senescence-associated features in HSCs. Flow cytometry revealed a significantly lower proportion of C12FDG+ cells in the S100A8-deficient group than in controls (supplemental Figure 9A-B). Immunofluorescence staining further showed decreased γ-H2AX accumulation in BM HSCs from knockout mice (supplemental Figure 9C). Consistently, quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis demonstrated downregulation of senescence-related genes p16Ink4a and p19Arf in CD34–LSK cells lacking S100A8 (supplemental Figure 9D), supporting a role for S100A8 in promoting stress-induced HSC senescence.

Collectively, elevated S100A8 expression not only reduces the number of HSCs but also promotes the development of senescent phenotypes, thereby weakening their long-term hematopoietic reconstitution capacity. These results indicate that S100A8 may serve as an important negative regulator of long-term hematopoietic function.

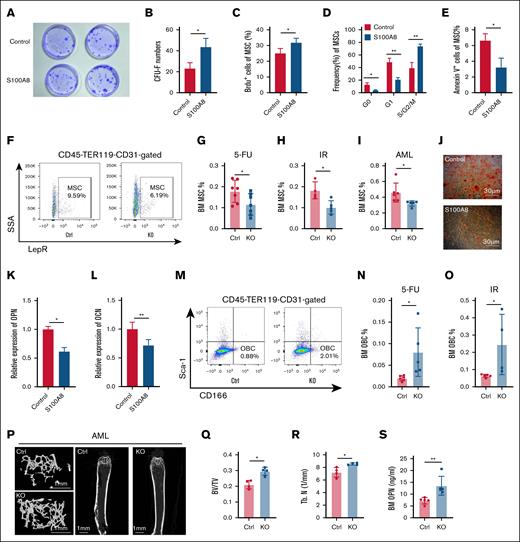

S100A8 remodeled the BM microenvironment

We investigated whether dysregulated expression of S100A8 causes microenvironment remodeling, which affects hematopoietic homeostasis and leukemia progression. After overexpressing S100A8, MSCs were cultured for 72 hours. Then, colony-forming unit–fibroblast experiments were performed, which revealed that S100A8 overexpression significantly increased colony-forming unit–fibroblast formation (Figure 7A-B). Flow cytometry analysis revealed that the group with S100A8 overexpression had a higher proliferation rate (Figure 7C). In addition, the S100A8 overexpression group showed a decrease in G0 and G1 phase cells, along with an increase in S/G2/M phase cells (Figure 7D). Furthermore, the S100A8 overexpression group had a lower apoptosis ratio than the control group (Figure 7E). Subsequent investigations into MSCs in the mouse model revealed a lower percentage of MSCs in S100A8 knockout mice than in control mice after 5-FU and IR exposure, as well as in AML mice (Figure 7F-I). Furthermore, our findings showed that S100A8 overexpression in vitro inhibited MSC differentiation into OBCs and reduced osteopontin (OPN) and osteocalcin expression, while promoting adipogenic differentiation (Figure 7J-L; supplemental Figure 10). In contrast, S100A8-deficient mice showed an increase in OBCs after 5-FU and IR exposure in AML mice, leading to increased secretion of OPN (Figure 7M-S). This suggests that remodeling of the BM microenvironment by S100A8 may have an indirect effect on stress hematopoiesis and leukemia progression.

Effects of S100A8 on MSC proliferation and differentiation. (A) Representative plots of CFU-F for the S100A8 overexpression group and control group. (B) CFU-F counts in the S100A8 overexpression group and control group (n = 3). (C) The proliferation of MSCs in the S100A8 overexpression and control groups (n = 4). (D) Cell cycle status of MSCs in the S100A8 overexpression and control groups (n = 3). (E) MSC apoptosis in the S100A8 overexpression and control groups (n = 3). (F) Flow diagram of BM MSCs of S100A8-deficient and control mice. (G-I) MSC ratio in BM of S100A8-deficient and control mice after 5-FU treatment (G), IR exposure (H), and AML (I; n = 5-7). (J) Representative images of Alizarin red staining (osteogenic differentiation) of MSC in the S100A8 overexpression and control groups. (K-L) quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction analysis of osteoblastic differentiation relative genes (OPN and OCN) in MSCs from the S100A8 overexpression group and control group (n = 3). (M) A flow diagram of BM OBCs from S100A8-deficient and control mice. (N-O) OBC ratio in the BM of S100A8-deficient and control mice after 5-FU treatment (N) and IR exposure (O; n = 5-6). (P-R) Microcomputed tomography analysis of the trabecular bone in S100A8-deficient and control AML mice. Representative images are displayed in panel P (scale bars, 1 mm). (Q-R) Trabecular BT/BV and Tb. N in the femoral metaphysis are illustrated (n = 4). (S) Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay analysis of BM protein concentrations of OPN in S100A8-deficient and control AML mice (n = 5). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. BT/BV, bone volume/total volume; Ctrl, control; KO, knockout; Tb. N, trabecular number.

Effects of S100A8 on MSC proliferation and differentiation. (A) Representative plots of CFU-F for the S100A8 overexpression group and control group. (B) CFU-F counts in the S100A8 overexpression group and control group (n = 3). (C) The proliferation of MSCs in the S100A8 overexpression and control groups (n = 4). (D) Cell cycle status of MSCs in the S100A8 overexpression and control groups (n = 3). (E) MSC apoptosis in the S100A8 overexpression and control groups (n = 3). (F) Flow diagram of BM MSCs of S100A8-deficient and control mice. (G-I) MSC ratio in BM of S100A8-deficient and control mice after 5-FU treatment (G), IR exposure (H), and AML (I; n = 5-7). (J) Representative images of Alizarin red staining (osteogenic differentiation) of MSC in the S100A8 overexpression and control groups. (K-L) quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction analysis of osteoblastic differentiation relative genes (OPN and OCN) in MSCs from the S100A8 overexpression group and control group (n = 3). (M) A flow diagram of BM OBCs from S100A8-deficient and control mice. (N-O) OBC ratio in the BM of S100A8-deficient and control mice after 5-FU treatment (N) and IR exposure (O; n = 5-6). (P-R) Microcomputed tomography analysis of the trabecular bone in S100A8-deficient and control AML mice. Representative images are displayed in panel P (scale bars, 1 mm). (Q-R) Trabecular BT/BV and Tb. N in the femoral metaphysis are illustrated (n = 4). (S) Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay analysis of BM protein concentrations of OPN in S100A8-deficient and control AML mice (n = 5). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. BT/BV, bone volume/total volume; Ctrl, control; KO, knockout; Tb. N, trabecular number.

Discussion

Myeloid cells exhibit the baseline alarming protein S100A8 expression as a marker, whereas MSCs typically do not express S100A8 under steady-state conditions. In this study, we found that the presence of AML, 5-FU treatment, and IR all led to an increase in S100A8 expression. These findings highlight the critical role of MSC-derived S100A8 as a potent proinflammatory factor in AML and hematopoietic regeneration during stress.

Using an in vitro coculture system of MSCs with leukemia cells and an MLL-AF9 leukemia mouse model, we discovered that MSC-derived S100A8 promotes leukemia cell proliferation and drug resistance while reducing the survival of leukemic mice. These results highlight the pivotal role of S100A8 in shaping a leukemia-supportive BM microenvironment and underscore its potential as a therapeutic target in AML. Notably, monoclonal antibodies targeting S100A8/A9 are already under investigation for their therapeutic potential in myeloid malignancies, including myeloproliferative neoplasms, MDSs, and leukemia.37 According to reports, the cell membrane receptors RAGE and TLR4 are the primary binding receptors for S100A8 homodimers and S100A8/A9 heterodimers.38 Our findings further show that TLR4 is the primary binding receptor for S100A8 in leukemia cells, as evidenced by the inhibition of RAGE and TLR4 receptors in the coculture system. S100A8 activates the downstream PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, which regulates leukemia cell growth and proliferation. Dysregulation of the PI3K pathway is common in various human cancers, accounting for ∼50% of de novo AML cases exhibiting this aberration.39-43 The PI3K inhibitor was introduced into the coculture system, and subsequent findings confirmed the role of S100A8 in modulating leukemia cell proliferation via the PI3K pathway. A recent study discovered that DNA damage is inextricably linked to the PI3K/Akt pathway, which controls the senescence of HSCs.44 In this study, we discovered that LSCs in the S100A8-deficient group had lower levels of ROS and DNA damage, indicating that S100A8 may play a regulatory role in the PI3K/Akt pathway, which is associated with DNA damage and subsequent promotion of leukemia cell proliferation.

Previous research has shown that AML development and HSC aging are associated with the accumulation of DNA damage and increased ROS levels. Modifications in antioxidant enzyme levels in the plasma of individuals with AML, that is, the decreased antioxidant status found in the plasma of patients with AML, are most likely due to elevated ROS levels, as evidenced by the decline in antioxidant activity. This decrease in antioxidant activity indicates that oxidative stress is widely recognized as a significant factor in AML progression and recurrence.45-50 In contrast, BM cells from transcription factor Meis1-deficient mice had reduced colony formation and significantly fewer LT-HSCs, which lost quiescence due to ROS accumulation in HSCs. ATF4 deficiency causes severe defects in HSCs, leading to a complex aging-like phenotype, and the HSC defects in ATF4–/– mice are linked to elevated production of mitochondrial ROS.

In our study, we found that MSC-derived S100A8 increased ROS levels not only in LSCs but also in HSCs (supplemental Figure 11A-D). This study demonstrates that increased S100A8 expression in MSCs contributes to short-term hematopoietic recovery after IR and 5-FU–induced stress, which is consistent with previous research highlighting the role of an inflammatory microenvironment in promoting swift hematopoiesis recovery, particularly of the myeloid lineage.22 The underlying mechanism may involve activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway and upregulation of the transcription factor GATA2 (supplemental Figure 11E-H), both of which are associated with myeloid differentiation. Nonetheless, this phenomenon has been shown to have a negative impact on the long-term preservation of HSCs, eventually reducing the stem cell reservoir. Our findings also indicate that the long-term maintenance of HSCs is compromised by sustained 5-FU stress. According to our findings, S100A8 promotes the entry of G0-phase HSCs into the cell cycle. HSC quiescence and activation are highly complex interactions governed by a variety of cell-intrinsic and -extrinsic factors.51-53 Our findings identify S100A8 as a critical regulator in determining the fate of HSCs, particularly in "awakening" dormant HSCs in response to hematological insults caused by IR and 5-FU. S100A8 clearly directs HSC differentiation toward the myeloid lineage, but the sustained inflammatory response it mediates may eventually lead to HSC exhaustion. Increased levels of ROS may explain the contradictory effect of S100A8 expression, which inhibits the preservation of healthy HSCs while concurrently facilitating leukemia progression.

The decline in HSC function and hematopoietic impairment associated with S100A8 may be attributable to dysregulation of MSCs. Under stress conditions such as IR, 5-FU treatment, and AML, aberrant upregulation of S100A8 drives MSCs into cell cycle progression while simultaneously impairing their osteogenic differentiation capacity. Consequently, diminished osteogenic differentiation reduces the expression and secretion of OPN, a critical bridging protein primarily from MSCs and OBCs. Previous studies have demonstrated that OPN negatively regulates HSC54 and its depletion induces phenotypes characteristic of hematopoietic senescence.55 Specifically, when young HSCs are exposed to an OPN-deficient niche, their ability to engraft is reduced, whereas the frequency of LT-HSCs increases, and stem cell polarity is lost. Conversely, when aged HSCs are exposed to thrombin-cleaved OPN, the aging process is reversed, resulting in increased engraftment, decreased HSC frequency, increased stem cell polarity, and restoration of the balance between lymphoid and myeloid cells in PB.55

In summary, our findings reveal the dual role of the mesenchymal niche inflammatory factor S100A8: facilitating AML progression via TLR4/PI3K/Akt pathway and suppressing stress hematopoiesis. In addition, S100A8 stimulates the production of ROS in both HSCs and LSCs, causing HSC senescence and promoting leukemia cell self-renewal. This novel finding sheds new light on the relationship between niche inflammation, hematopoiesis, and malignant transformation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all of the patients who took part in this study, as well as their families.

This study was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of China program (grant numbers 81900116, 82370176, 82000127, 82200254, and 82470117), the Key Research and Development Program of Hubei Province (2023BCB025), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2042025YXB011) and the Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University discipline construction platform project (grant numbers 202021, PDJH202217).

Authorship

Contribution: X. Liu, J.W., and F.Z. contributed to conceptualization; X. Liu, J.W., and X. Li contributed to methodology; F.Z. contributed to validation, writing, including review and editing, and supervision; X. Liu and J.W. provided formal analysis; X. Liu, J.W., X. Li, L.M., G.C., Q.W., N.Z., X.T., Y.T., H.J., Y.L., R.L., M.S., and W.Y. conducted investigation; L.L., T.H., J.W., and X. Li provided resources; X. Liu, J.W., and R.P. curated data and contributed to visualization; X. Liu wrote the original draft; X. Liu and F.Z. administered the project; X. Liu, X.Z., and F.Z. acquired funding; and all authors reviewed and authorized the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Fuling Zhou, Department of Hematology, Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, 169 Donghu Rd, Wuhan 430071, People's Republic of China; email: zhoufuling@whu.edu.cn; and Xian Zhang, Department of Hematology, Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, 169 Donghu Rd, Wuhan 430071, People's Republic of China; email: sunshining1013@163.com.

References

Author notes

X. Liu, J.W., and X. Li contributed equally to this study as joint first authors.

The RNA sequencing data sets used in this study were reanalyzed from our previously published work. The raw data have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GSE107814).

The data sets used and/or analyzed during this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding authors, Fuling Zhou (zhoufuling@whu.edu.cn) and Xian Zhang (sunshining1013@163.com).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.