Key Points

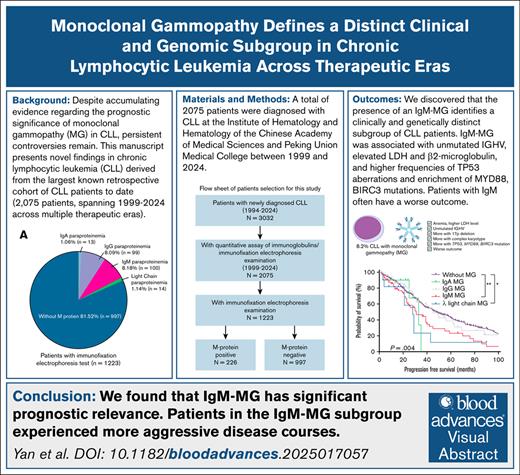

A largest known retrospective cohort of 2075 patients with CLL (1999-2024) was leveraged.

This study reveals that the presence of an IgM-MG identifies a clinically and genetically distinct subgroup of patients with CLL.

Visual Abstract

Monoclonal gammopathy (MG) in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) portends heterogeneous outcomes, yet its molecular drivers and therapeutic implications remain undefined. In this retrospective analysis of 2075 patients with CLL (1999-2024), MG was detected in 18.47% cases, with immunoglobulin M (IgM) (8.18%), IgG (8.09%), light-chain (1.14%), and IgA (1.06%) subtypes demonstrating divergent clinicogenomic profiles. Patients with IgA-MG were older at diagnosis, whereas those with IgG-MG had a younger age and a higher frequency of mutated immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable (IGHV). In contrast, IgM-MG was associated with unmutated IGHV, elevated lactate dehydrogenase and β2-microglobulin levels, higher frequencies of TP53 aberrations, and enrichment of MYD88, BIRC3, and DDX3X mutations. IgG-MG was associated with shorter time-to-first treatment (TTFT) only, whereas IgM-MG correlated with significantly inferior TTFT, progression-free survival, and overall survival. Subgroup analyses revealed that the adverse prognostic impact of MG was pronounced in IGHV-mutated CLL but attenuated in unmutated cases. Prognostic discrimination by the CLL-International Prognostic Index (CLL-IPI) remained robust regardless of MG status. Notably, patients with IgM-MG did not experience significant survival benefit from targeted therapy compared with conventional regimens. These findings demonstrate that MG subtypes, particularly IgM-MG, define biologically and clinically distinct subsets of CLL. Given the limited efficacy of Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors in IgM-MG, immunofixation-based MG profiling may inform risk-adapted treatment strategies and personalized therapy selection.

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), the most common adult leukemia in Western countries, demonstrates marked clinical heterogeneity ranging from indolent to rapidly progressive disease. Although the introduction of targeted therapies, including Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors (BTKis) and B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) inhibitors, has revolutionized treatment paradigms and improved survival outcomes, significant challenges persist in predicting individual therapeutic responses and long-term prognosis.1 Notably, ∼30% of patients develop resistance to covalent BTKis through BTK C481S or PLCG2 mutations, and novel noncovalent inhibitors and BTK degrader are now emerging to circumvent these mechanisms. In this evolving landscape, identifying biomarkers that predict early relapse or guide sequential therapies is imperative.

Monoclonal gammopathy (MG), characterized by clonal immunoglobulin secretion, traditionally serves as a diagnostic hallmark of plasma cell disorders, but it is increasingly recognized in B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas (B-NHLs). Approximately 17.3% to 34.6% of patients with CLL harbor detectable MG, a prevalence comparable to other B-NHL subtypes, such as 100% in Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM), 18% to 37.6% in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), 26% in follicular lymphoma (FL), and 10.7% to 42% marginal zone lymphoma (MZL).2 Emerging evidence suggests that MG in B-NHLs may transcend its diagnostic utility and participate in disease pathogenesis. Tumor-derived immunoglobulins in FL and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma exhibit antigen-binding specificity to microbial components or apoptotic cell epitopes, facilitating microenvironmental interactions that promote clonal survival and proliferation.3,4 In addition, CLL-derived immunoglobulins recognize bacterial epitopes and apoptotic blebs, implicating chronic antigen stimulation in leukemogenesis.5 These observations presume that the presence, isotype, and concentration of MG may mirror intrinsic tumor biology and influence clinical trajectories.

The prognostic significance of MG in CLL remains contentious. Earlier retrospective analyses failed to demonstrate significant differences in outcomes between MG-positive and MG-negative CLL cohort, irrespective of paraprotein isotype.6 However, subsequent research revealed that patients with MG-positive CLL often have shorter progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) compared with their MG-negative counterparts.7,8 In particular, IgM can be detected in patients with CLL; the IgM subtype of MG has been closely associated with advanced Rai/Binet stages, del(17p)/TP53 mutations, and poorer clinical outcomes.8-16 Despite these findings, some studies reported no significant survival difference between patients with CLL with or without IgM paraprotein.17

Beyond monoclonal proteins, broader humoral immune dysfunction, including hypogammaglobulinemia and IgA deficiency, correlates with accelerated time-to-first treatment (TTFT) and infection-related mortality.9,18-20 Hypogammaglobulinemia has been linked to shorter OS.21 Nevertheless, conflicting data persist regarding the clinical relevance of IgG deficiency, emphasizing the need for rigorous stratification by immunoglobulin subtype and treatment modality.22,23

Despite accumulating evidence on the prognostic implications of MG in CLL, persistent controversies arise from methodological limitations in prior studies, predominantly small single-center cohorts, heterogeneous MG detection methodologies, and insufficient representation of patients treated with modern targeted agents. These knowledge gaps critically hinder the translation of MG biomarkers into clinical decision frameworks for precision treatment. To bridge these critical gaps, a large retrospective cohort of 2075 patients with CLL (1999-2024) was studied, systematically evaluating both qualitative and quantitative dimensions of MG across therapeutic eras. These insights aim to explore the prognostic significance of MG in patients with CLL across different therapeutic landscapes, offering insights into its utility in guiding treatment strategies.

Patients and methods

Study design

A total of 2075 patients were diagnosed with CLL at the Institute of Hematology and Hematology of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College between 1999 and 2024. All cases involved in this study were from the National Longitudinal Cohort of Hematological Diseases in China (NICHE, NCT04645199) and approved by the ethics committees of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Blood Disease Hospital, and patients’ informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Clinical features, including age, sex, biological parameters (platelet count, white blood cell count, lactate dehydrogenase [LDH], β2-microglobulin [β2MG], serum protein profile or immunoglobulin levels), and survival data, were collected.

Immunofixation electrophoresis

Serum immunoglobulin quantification was performed using spectrophotometry, and immunoglobulin concentrations were subsequently calculated based on a calibration curve derived from known immunoglobulin standards. Normal immunoglobulin levels were determined according to established clinical laboratory reference ranges: globulin, 20 to 40 g/L; IgM, 0.46 to 3.04 g/L; IgG, 7.51 to 15.6 g/L; and IgA, 0.7 to 4 g/L. Immunofixation electrophoresis (IFE) was conducted by immunoprecipitating patients' serum on agarose gel, followed by analysis of the precipitate to identify monoclonal proteins. Patients were defined as MG positive if they demonstrated a distinct monoclonal protein band detected by IFE in serum, with clearly identifiable heavy-chain (IgG, IgM, or IgA) and/or light-chain (kappa or lambda) components. Patients without detectable monoclonal protein by IFE were classified as MG negative.

Molecular genetic characteristic testing

The karyotypes were conducted using conventional metaphase cytogenetic analysis with R- and G-banding techniques. Abnormal karyotype was defined as the presence of any clonal cytogenetic abnormality, whereas complex karyotype was defined by the presence of at least 3 chromosome aberrations. Fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis was performed on the interphase nuclei of uncultured bone marrow (BM) cells. Commercial probes including 11q22.3(LSI ATM/CEP11), 17p13.1(LSI TP53/CEP17), and 13q14.2 (LSI RB-1) (Vysis, Abbott) were used for routine screening according to the manufacturer’s instructions.24 Immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable (IGHV) gene analysis was performed as previously described.25 Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of IGHV-IGHDIGHJ was performed on genomic DNA or complementary DNA samples using the IGH Somatic Hypermutation Assay version 2.0 (Invivoscribe Technologies, San Diego, CA). IGHV sequences with <98% homology to the germline sequence were considered mutated IGHV.

Targeted sequencing of a 112-gene panel was conducted on 717 patients with CLL, as previously reported.26,27 Libraries for 185 samples were prepared using the Ion AmpliSeq Library Kit 2.0 on the Ion Chef System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and sequenced using Ion Torrent NGS platforms. For the remaining 532 samples, 281-panel sequencing libraries were prepared using the Agilent SureSelect Human All Exon Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform, generating 150-bp paired-end reads (Illumina, San Diego, CA).

Outcomes and statistical analysis

Patients with CLL who received treatment were classified into the following 3 groups based on their first-line therapy: (1) the chemotherapy group, comprising patients treated with traditional chemotherapeutic agents only, without CD20 monoclonal antibodies, BTKis, or BCL-2 inhibitors; (2) the immunochemotherapy group, comprising patients treated with CD20 monoclonal antibodies, either alone or in combination with chemotherapy, but without targeted therapies; and (3) the targeted therapy group, comprising patients treated with BTKi and/or BCL-2 inhibitors. TTFT was defined as time from diagnosis to first treatment. PFS was recorded as the interval from treatment to disease progression, relapse, death from any cause, or the last follow-up evaluation. For OS, the time interval was measured from treatment initiation to death for all causes or last follow-up. OS, PFS, and TTFT were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Continuous variables were summarized as medians and interquartile ranges, whereas categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Group comparisons were performed using independent-sample t tests for continuous variables and χ2 or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables. Rai and CLL-International Prognostic Index (CLL-IPI) staging distributions were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Proportional hazards regression models were applied to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) for disease progression and death, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical significance was defined as a 2-sided P value ≤.05. Multiple comparisons were adjusted using Bonferroni correction where applicable. GraphPad Prism 9 and SPSS Statistics 29 were used for all statistics.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Institute of Hematology & Blood Diseases Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Result

Baseline characteristics

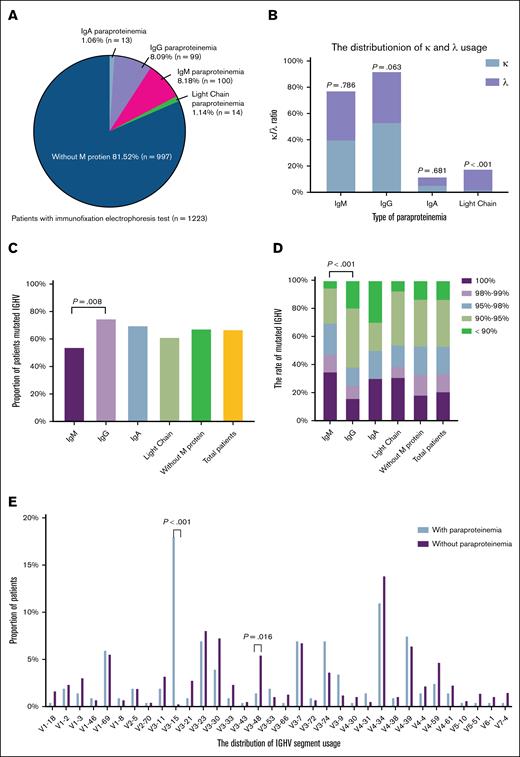

A total of 2075 patients were included in this study, all of whom underwent serum immunoglobulin level testing. Among these, 1223 patients completed IFE (supplemental Figure 1; available on the Blood website). The baseline characteristics were compared between patients with and without IFE testing. No significant differences were found regarding age, sex, or most baseline laboratory findings (supplemental Table 1). MG was identified in 226 of 1223 patients (18.47%). Within the MG-positive cohort, IgM-MG was most common (n = 100, 8.18%), followed by IgG type (n = 99, 8.09%), light-chain type (n = 14, 1.14%), and IgA type (n = 13, 1.06%) (Figure 1A). Light-chain MG was predominantly of lambda type, whereas other MG subtypes had no significant light-chain preference (Figure 1B). The median age at diagnosis in the MG-positive group was 60 years (range, 29-85). Compared with the MG-negative group, the MG-positive individuals exhibited a higher male predominance and were more likely to present with splenomegaly, anemia, hypoalbuminemia, elevated LDH levels, and elevated β2MG levels (Table 1). Overall, MG-positive patients were diagnosed at later clinical stages with more aggressive disease phenotypes. Notably, distinct clinical profiles emerged among MG subtypes: IgM-type MG was more strongly associated with elevated LDH (IgA vs IgG vs IgM: 38.46% vs 26.60% vs 41.94%, P = .084), abnormal karyotype (IgA vs IgG vs IgM: 50.00% vs 41.57% vs 58.33%, P = .088), and TP53 deletions (IgA vs IgG vs IgM: 9.09% vs 5.38% vs 17.39%, P = .026), whereas IgA-type MG was associated with older age at diagnosis (IgA vs IgG vs IgM: 66.38 years vs 58.88 years vs 60.17 years, P = .063) (supplemental Table 2).

The distribution of MG in CLL and its relationship to IGHV gene. (A) Distribution of different subtypes of MG. (B) The distribution of lambda and kappa light-chain use in different types of paraproteinemia. (C) Proportion of patients with mutated IGHV in different MG group. (D) Relationship between MG subtypes and IGHV mutational status. (E) The distribution of IGHV segment use in patients with or without MG.

The distribution of MG in CLL and its relationship to IGHV gene. (A) Distribution of different subtypes of MG. (B) The distribution of lambda and kappa light-chain use in different types of paraproteinemia. (C) Proportion of patients with mutated IGHV in different MG group. (D) Relationship between MG subtypes and IGHV mutational status. (E) The distribution of IGHV segment use in patients with or without MG.

Baseline characteristics of patients with CLL with and without MG

| Characteristics, n/N(%) . | M protein negative (N = 997) . | M protein positive (N = 226) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 643/997 (64.49) | 155/226 (68.58) | .244 |

| Age at diagnosis, median (SD) | 59.4 (10.43) | 60.19 (10.86) | .309 |

| Age > 65 years | 284/997 (28.49) | 69/226 (30.53) | .540 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 686/987 (69.50) | 143/223 (64.13) | .118 |

| Splenomegaly | 534/987 (54.10) | 167/223 (74.89) | <.001 |

| White blood cell count ≥100 × 109/L | 98/997 (9.83) | 21/226 (9.29) | .806 |

| Hemoglobin level <110 g/L | 209/997 (20.96) | 101/226 (44.69) | <.001 |

| Platelet count <100 × 109/L | 205/997 (20.56) | 66/226 (29.20) | .005 |

| Albumin <35 g/L | 34/962 (3.53) | 42/222 (18.92) | <.001 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase ≥248 U/L | 193/941 (20.51) | 76/214 (35.51) | <.001 |

| β2MG >3.5 mg/L | 270/865 (31.21) | 115/196 (58.67) | <.001 |

| Rai stage | <.001 | ||

| 0 | 138/997 (13.84) | 18/226 (7.96) | |

| I | 205/997 (20.56) | 18/226 (7.96) | |

| II | 335/997 (33.60) | 74/226 (32.74) | |

| III | 114/997 (11.43) | 50/226 (22.12) | |

| IV | 205/997 (20.56) | 66/226 (29.20) | |

| CLL-IPI stage | <.001 | ||

| Low | 254/718 (35.38) | 37/168 (22.02) | |

| Intermediate | 222/718 (30.92) | 50/168 (29.76) | |

| High | 179/718 (24.93) | 64/168 (38.10) | |

| Very high | 63/718 (8.77) | 17/168 (10.12) | |

| Abnormal karyotype | 423/891 (47.47) | 98/197 (49.75) | .564 |

| Complex karyotype | 180/891 (20.20) | 43/197 (21.83) | .609 |

| FISH examination | |||

| With TP53 deletion (17p) | 85/895 (9.50) | 23/210 (10.95) | .523 |

| With ATM deletion (11q) | 89/847 (10.51) | 17/203 (8.37) | .365 |

| With 13q deletion (13q) | 120/551 (21.78) | 16/137 (11.68) | .008 |

| CEP12 (+12) | 148/728 (20.33) | 30/157 (19.11) | .729 |

| With mutated IGHV | 518/766 (67.62) | 111/171 (64.91) | .495 |

| Initiate treatment within the follow-up period | 560/997 (56.17) | 177/226 (78.32) | <.001 |

| Treatment regimens | .342 | ||

| Chemotherapy | 189/555 (34.05) | 50/174 (28.74) | |

| Immunochemotherapy | 153/555 (27.57) | 56/174 (32.18) | |

| Targeted therapy | 213/555 (38.38) | 68/174 (39.08) |

| Characteristics, n/N(%) . | M protein negative (N = 997) . | M protein positive (N = 226) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 643/997 (64.49) | 155/226 (68.58) | .244 |

| Age at diagnosis, median (SD) | 59.4 (10.43) | 60.19 (10.86) | .309 |

| Age > 65 years | 284/997 (28.49) | 69/226 (30.53) | .540 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 686/987 (69.50) | 143/223 (64.13) | .118 |

| Splenomegaly | 534/987 (54.10) | 167/223 (74.89) | <.001 |

| White blood cell count ≥100 × 109/L | 98/997 (9.83) | 21/226 (9.29) | .806 |

| Hemoglobin level <110 g/L | 209/997 (20.96) | 101/226 (44.69) | <.001 |

| Platelet count <100 × 109/L | 205/997 (20.56) | 66/226 (29.20) | .005 |

| Albumin <35 g/L | 34/962 (3.53) | 42/222 (18.92) | <.001 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase ≥248 U/L | 193/941 (20.51) | 76/214 (35.51) | <.001 |

| β2MG >3.5 mg/L | 270/865 (31.21) | 115/196 (58.67) | <.001 |

| Rai stage | <.001 | ||

| 0 | 138/997 (13.84) | 18/226 (7.96) | |

| I | 205/997 (20.56) | 18/226 (7.96) | |

| II | 335/997 (33.60) | 74/226 (32.74) | |

| III | 114/997 (11.43) | 50/226 (22.12) | |

| IV | 205/997 (20.56) | 66/226 (29.20) | |

| CLL-IPI stage | <.001 | ||

| Low | 254/718 (35.38) | 37/168 (22.02) | |

| Intermediate | 222/718 (30.92) | 50/168 (29.76) | |

| High | 179/718 (24.93) | 64/168 (38.10) | |

| Very high | 63/718 (8.77) | 17/168 (10.12) | |

| Abnormal karyotype | 423/891 (47.47) | 98/197 (49.75) | .564 |

| Complex karyotype | 180/891 (20.20) | 43/197 (21.83) | .609 |

| FISH examination | |||

| With TP53 deletion (17p) | 85/895 (9.50) | 23/210 (10.95) | .523 |

| With ATM deletion (11q) | 89/847 (10.51) | 17/203 (8.37) | .365 |

| With 13q deletion (13q) | 120/551 (21.78) | 16/137 (11.68) | .008 |

| CEP12 (+12) | 148/728 (20.33) | 30/157 (19.11) | .729 |

| With mutated IGHV | 518/766 (67.62) | 111/171 (64.91) | .495 |

| Initiate treatment within the follow-up period | 560/997 (56.17) | 177/226 (78.32) | <.001 |

| Treatment regimens | .342 | ||

| Chemotherapy | 189/555 (34.05) | 50/174 (28.74) | |

| Immunochemotherapy | 153/555 (27.57) | 56/174 (32.18) | |

| Targeted therapy | 213/555 (38.38) | 68/174 (39.08) |

FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; SD, standard deviation.

Further exploration revealed associations between MG subtype and IGHV mutation status. Among patients with IgM-MG, 45.83% harbored unmutated IGHV, significantly higher than the proportion observed among the remaining patients (31.79%, 275/865, P = .015), which included those with other types of MG or no MG. In contrast, 75% of patients with IgG-type MG exhibited mutated IGHV status (Figure 1C-D). In addition, MG-positive patients exhibited preferential use of the VH3 gene segment, particularly VH3-15 (18.09% vs 0.35%, P < .001) (Figure 1E; supplemental Figure 2A). No significant differences in CDR3 length were observed between MG-positive and MG-negative groups (supplemental Figure 2B).

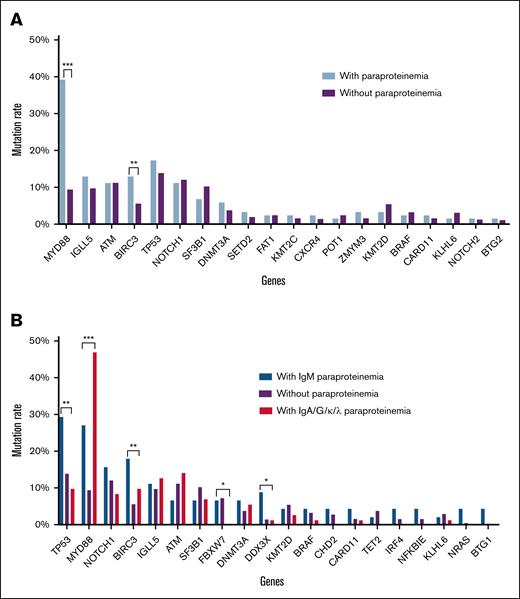

M protein and gene mutation

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) data from 717 patients (114 MG positive, 603 MG negative) revealed distinct genetic profiles. MG-positive CLL was significantly associated with higher frequencies of MYD88 (39.47% vs 9.62%, P < .001) and BIRC3 mutations (13.16% vs 5.8%, P = .005) (Figure 2A). Furthermore, IgM-type MG was notably linked to mutations in TP53, BIRC3, and DDX3X, whereas IgG-/IgA-/light-chain-type MG had a stronger correlation with MYD88 mutations (Figure 2B). The frequency of NFKBIE mutations was also slightly higher in patients with IgM-MG compared with those without IgM-MG (4.55% vs 0.89%, P = .081). This underscores distinct molecular characteristics associated with MG subtypes.

Gene mutation spectrum detected by next-generation target sequencing. (A) Gene mutation rate in MG-positive and MG-negative patients with CLL. (B) Mutation rates in patients with different types of paraproteinemia. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001.

Gene mutation spectrum detected by next-generation target sequencing. (A) Gene mutation rate in MG-positive and MG-negative patients with CLL. (B) Mutation rates in patients with different types of paraproteinemia. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001.

Given the prominence of MYD88 mutations, particularly MYD88 L265P common in WM, mutation hotspots in MG-positive CLL were evaluated. Among MG-positive patients, the most frequent MYD88 mutations were V204F and L265P (each 26.67%), followed by V217F/A (20%). In MG-negative CLL, the most common mutations were also V204F and L265P, with frequencies of 23.21% and 41.07%, respectively (supplemental Figure 3). Thus, the mutation sites of MYD88 in patients with MG-positive CLL did not differ significantly from those of patients with MG-negative CLL.

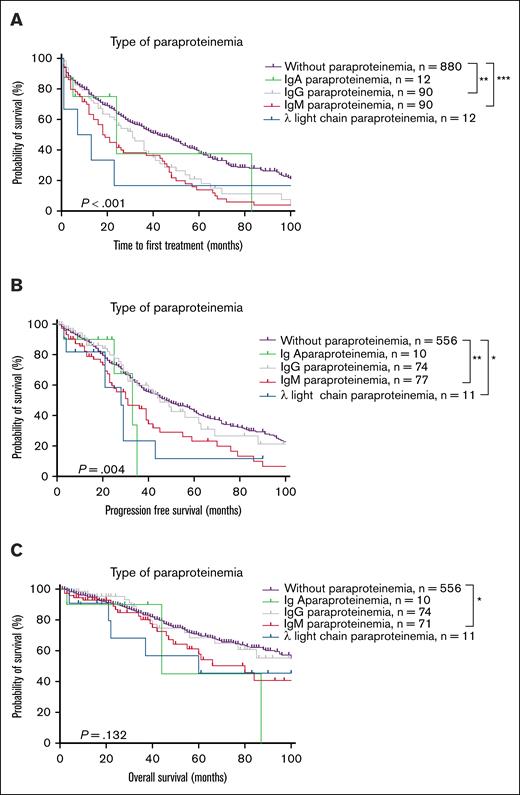

Prognostic impact of MG subtypes

Patients were stratified into 5 subgroups based on MG: MG-negative, IgA-MG, IgG-MG, IgM-MG, and lambda light-chain-MG CLL. Owing to the small number of cases with kappa light-chain MG (n = 2), it was not included in the survival analysis. Survival analyses revealed that compared with patients with MG-negative CLL, those with IgM-MG had shorter TTFT, PFS, and OS (median TTFT 18 months vs 42 months, P < .001; median PFS 31 months vs 48 months, P = .001; median OS 80 months vs 124 months, P = .044). However, patients with IgG-MG had shorter TTFT only (median TTFT 31 months vs 42 months, P = .006, 95% CI: 0.4627-0.9429), whereas patients with IgA-MG had no significant survival differences. Patients with lambda light-chain MG had shorter PFS but similar TTFT and OS compared with patients with MG-negative CLL (median PFS 28 months vs 48 months, P = .030, 95% CI:0.1707-1.289) (Figure 3; supplemental Figure 4). Furthermore, owing to these small numbers of patients with IgA- and light-chain MG, clinical outcome trends cannot be reliably analyzed and definitive conclusions regarding their prognostic significance cannot be identified.

Survival analysis of MG-positive and MG-negative patients with CLL. (A) TTFT. (B) PFS. (C) OS. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001.

Survival analysis of MG-positive and MG-negative patients with CLL. (A) TTFT. (B) PFS. (C) OS. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001.

Prognostic impact of IgM-MG across different subgroups and treatment modalities

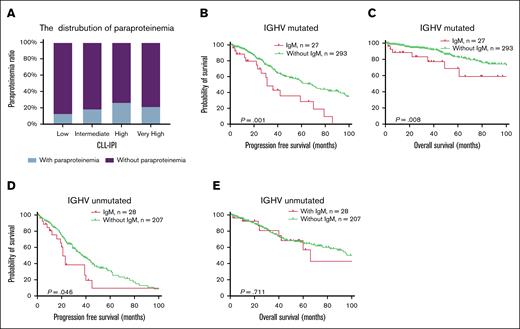

The CLL-IPI score is a widely used prognostic system for CLL.28 The distribution of MG positivity differed across CLL-IPI risk categories, being highest in patients with high-risk CLL-IPI (Figure 4A). Subgroup analyses demonstrated that MG's adverse survival impact remained significant in IGHV-mutated CLL cases but diminished in IGHV-unmutated cases (Figure 4B-E). CLL-IPI maintained robust prognostic stratification irrespective of MG status (supplemental Figure 5).

Subgroup survival analysis of patients with MG stratified by IGHV mutation status. (A) The proportion of patients with MG in each risk group of CLL-IPI. (B-C) PFS and OS in patients with CLL with mutated IGHV. (D-E) PFS and OS in patients with CLL with unmutated IGHV.

Subgroup survival analysis of patients with MG stratified by IGHV mutation status. (A) The proportion of patients with MG in each risk group of CLL-IPI. (B-C) PFS and OS in patients with CLL with mutated IGHV. (D-E) PFS and OS in patients with CLL with unmutated IGHV.

The proportion of patients with TP53 deletions was observed to be significantly higher among patients with IgM-MG compared with those without IgM-MG (17.39% vs 9.08%, P = .010). Previous studies have well established that TP53 deletions confer poorer prognosis in patients with CLL.29 Therefore, an important question was whether the adverse prognostic impact of IgM-MG was independent of TP53 deletions. To address this, subgroup survival analyses were performed. The analysis revealed that within the subgroup of patients with TP53-deleted CLL, IgM-MG positivity was associated with significantly poorer outcomes (supplemental Figure 6A-B). In addition, within the subgroup of patients with IgM-MG, TP53 deletion also demonstrated significant prognostic impact (supplemental Figure 6C-D). Thus, the data clearly suggest that IgM-MG positivity represents an adverse prognostic factor independent of TP53 deletion status.

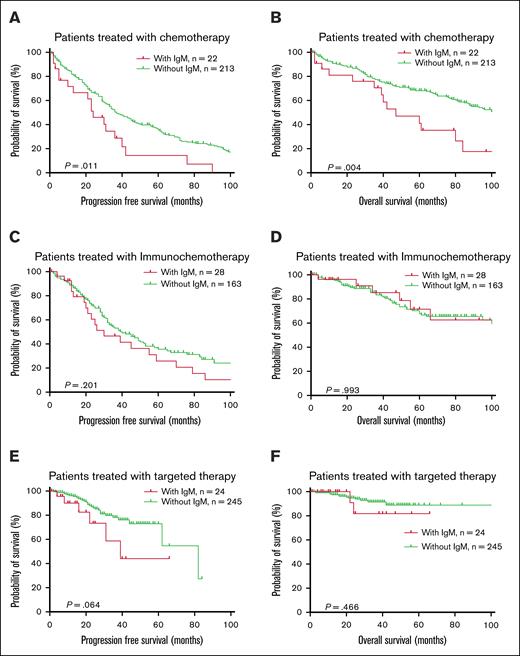

The patients were further divided into 3 groups based on first-line treatment regimens: traditional chemotherapy, immunochemotherapy, and targeted therapy. IgM-MG did not significantly affect PFS or OS in patients receiving immunochemotherapy but was associated with shorter survival in patients treated with traditional chemotherapy (Figure 5). In patients receiving targeted therapy as first-line treatment, those with IgM-MG had a trend toward inferior PFS compared with IgM-MG–negative counterparts, though this difference approached but did not reach statistical significance (median PFS: 39 vs 82 months; P = .064). Notably, no significant disparity in OS was observed between these subgroups (5-year OS rate 81.82% vs 88.85%; P = .466) (Figure 5). When stratified by treatment modalities, targeted therapy demonstrated superior survival outcomes over chemoimmunotherapy in IgM-MG–negative patients (median PFS: 82 vs 40 months; P < .001). Conversely, for IgM-MG–positive individuals, survival benefits of targeted agents were not statistically distinguishable from conventional chemotherapy or immunochemotherapy regimens (median PFS: 39 vs 24 months, P = .065, 39 and 30 months, P = .477; supplemental Figure 7).

Survival curve based on first-line treatment subgroups. (A-B) PFS and OS in patients with CLL treated with chemotherapy as first-line treatment. (C-D) PFS and OS in patients with CLL treated with immunochemotherapy. (E-F) PFS and OS in patients with CLL treated with targeted therapy.

Survival curve based on first-line treatment subgroups. (A-B) PFS and OS in patients with CLL treated with chemotherapy as first-line treatment. (C-D) PFS and OS in patients with CLL treated with immunochemotherapy. (E-F) PFS and OS in patients with CLL treated with targeted therapy.

Prognostic impact of immunoglobulin levels

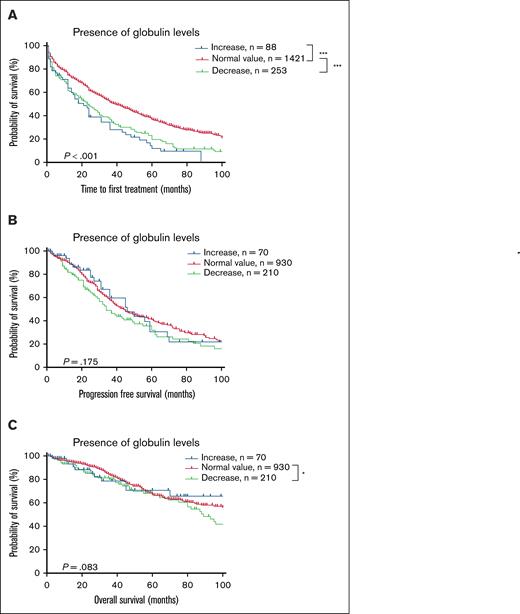

In addition to monoclonal immunoglobulins, immunoglobulin deficiency, predominantly isolated IgM deficiency, frequently accompanied CLL (supplemental Figure 8A). To investigate the impact of serum globulin levels on prognosis, the patients were categorized into the following 3 groups: elevated globulin, normal globulin, and decreased globulin levels. Survival analysis revealed that patients with low globulin levels had worse TTFT and OS but no significant difference in PFS (Figure 6). After confirming the adverse prognostic impact of low globulin levels, the patients were further classified based on IgM, IgG, and IgA levels (normal, elevated, or decreased). Patients with elevated IgM level (>3.04 g/L) had significantly worse TTFT, those with elevated IgG level (>15.6 g/L) had significantly worse TTFT and PFS, whereas those with elevated IgA levels had no significant differences in outcomes. It should be noted that elevated immunoglobulin levels described here differs from monoclonal protein (Mprotein) detected by IFE, as the elevated levels here reflect quantitative immunoglobulin measurements exceeding normal reference ranges, representing a different analytical dimension from immunofixation results. Reduced immunoglobulin levels (IgM < 0.46 g/L, IgG < 7.51 g/L, or IgA < 0.7 g/L) were associated with shorter TTFT but had no significant effect on PFS or OS (supplemental Figure 9).

Survival curve according to serum globulin level at diagnosis. (A) TTFT. (B) PFS. (C) OS. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001.

Survival curve according to serum globulin level at diagnosis. (A) TTFT. (B) PFS. (C) OS. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001.

Discussion

This large-scale study comprehensively delineates the clinical and molecular heterogeneity of MG-positive CLL, revealing that IgM-type MG defines a distinct high-risk subgroup characterized by aggressive disease phenotypes, unmutated IGHV status, and enrichment of specific genetic lesions. Higher prevalence rates of TP53, BIRC3, and DDX3X mutations were observed in IgM-MG CLL. The findings demonstrated that patients with CLL with IgM-type MG represented a distinct subgroup of patients. Importantly, these patients exhibited poorer outcomes, especially in patients treated with traditional chemotherapy and targeted therapy. In addition, patients with CLL with IgM-type MG derive less benefit from BTKis, highlighting the need for alternative therapeutic approaches for this subgroup. Integrating prior evidence, the findings of this study suggested that MG in CLL exhibits complex and multifactorial roles. The detection of MG positivity at the very early stages of CLL pathogenesis implies its potential involvement in disease initiation. Furthermore, the inferior prognosis associated with IgM-MG likely stems from dual interplay between high-risk molecular genetic features and immunosuppressive microenvironmental remodeling.

B cells produce immunoglobulins as a critical component of both the innate and adaptive immune systems. Aberrant B-cell activation and proliferation can lead to abnormal polyclonal or monoclonal production of immunoglobulins. A prospective cohort study demonstrated that elevated polyclonal and abnormal MG and free light-chain ratios represented early biomarkers, detectable up to 9.8 years before the clinical diagnosis of CLL. Notably, 44% of patients with CLL had M protein or abnormal free light-chain ratios before diagnosis, whereas hypogammaglobulinemia typically only emerged within 3 years before diagnosis.30 These findings suggest that monoclonal immunoglobulins occur early during CLL pathogenesis, whereas hypogammaglobulinemia represents a later event reflecting disease progression. In addition, familial CLL studies revealed that unaffected relatives of patients exhibit significantly higher serum IgM levels than the general population. Given that serum IgM plays critical roles in pathogen clearance, apoptotic cell removal, and immune regulation, persistently elevated IgM levels may disrupt immune homeostasis, potentially contributing to genetic susceptibility to CLL.31 Nevertheless, further investigation is required to elucidate the precise mechanistic role of immunoglobulins in CLL initiation and progression.

The early emergence of MG in CLL pathogenesis, preceding hypogammaglobulinemia, suggests a bidirectional interplay between clonal B cells and immune dysregulation. Elevated IgM levels may foster an immunosuppressive niche by recruiting myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and regulatory T cells (Tregs), as evidenced in WM.32 From the microenvironment perspective, monoclonal IgM might also be a sign of chronic antigenic stimulation, which is associated with immune exhaustion. The CLL clone could be responding to self or environmental antigens, driving it to continuously activate and differentiate. Over time, constant antigen/BCR engagement not only feeds the leukemia but also leads to an exhausted T-cell compartment and an accumulation of suppressive myeloid cells. In summary, immune dysfunction is broadly prevalent in most patients with CLL. MG-positive CLL may exist in a niche characterized by heightened microenvironmental activation and potentially dampened immune surveillance.

In addition to potentially influencing the immune microenvironment of CLL, specific molecular genetic abnormalities associated with MG may also affect patient prognosis and therapeutic resistance. Previous studies have yielded inconsistent conclusions regarding the prognostic significance of MG in CLL (supplemental Table 3). In addition to limited sample sizes, heterogeneous treatment regimens likely contribute significantly to these discrepancies. In this study, patients were stratified according to different first-line treatment modalities. In addition, among patients without MG, targeted therapies demonstrated superior outcomes compared with other treatment strategies. Conversely, patients with MG derived limited benefit from targeted therapies, exhibiting survival outcomes similar to those receiving non-targeted treatments (supplemental Figure 8). The observation of diminished BTKi efficacy in patients with IgM-type MG aligns closely with emerging evidence regarding resistance mechanisms to BTKi therapy.

Patients with CLL with IgM-type MG were more likely to harbor complex karyotypes, TP53 mutations/deletions, and BIRC3, NFKBIE, and DDX3X mutations. Previous studies have established that complex karyotypes and TP53 abnormalities were associated with relapse and resistance to targeted therapy.33-35BIRC3 encodes a protein involved in regulating the NF-κB signaling pathway, and BIRC3 mutations may lead to abnormal activation of this pathway, bypassing BTK-dependent signaling and sustaining tumor cell survival and proliferation.36 Indeed, sequencing studies of patients with CLL treated with ibrutinib have revealed that BIRC3 mutations are more frequent in ibrutinib-resistant patients compared with ibrutinib-sensitive patients.37NFKBIE mutations also could promote NF-κB activation, again allowing the leukemia to thrive despite BTK blockade. Therefore, NF-κB pathway aberrations frequently co-occurred with IgM-secreting CLL and conferred BTKi resistance. Although the association between DDX3X mutations and resistance to targeted therapies has not yet been established, some studies suggest that DDX3X mutations are associated with high-risk CLL or disease relapse.38,39 In addition, a recent sequencing study reported a higher frequency of TP53 mutations in IgM-MG CLL, consistent with the findings of this study.40 These results partially explain the shorter survival observed in patients with IgM-MG CLL, particularly in the context of targeted therapies. Notably, the adverse prognostic impact of IgM-MG is independent of CLL-IPI stage and IGHV mutation status. Given the ease and affordability of IFE, this test could serve as a practical prognostic marker in clinical settings. In the ASPEN trial, patients with WM harboring IgM paraproteins exhibited favorable responses to BTKi therapy,41 highlighting a differential biological context between WM and IgM-MG CLL. Potential explanations for this discrepancy might include differences in underlying genomic features, signaling pathway dependencies, or the tumor microenvironment between WM and CLL.

In CLL, infectious complications remain a leading cause of mortality,42 with hypogammaglobulinemia recognized as a key contributor to infection risk. Hypogammaglobulinemia develops in most patients with CLL over the disease course, often becoming more pronounced with disease progression and in advanced stages. Studies have revealed that patients with CLL often exhibit reductions in 1 or more immunoglobulin types, and such deficiencies were associated with progression and increased all-cause mortality.20-23,43,44 However, the impact of hypogammaglobulinemia on OS remains controversial, with conflicting results reported in the literature.9,18,19,21,22 These discrepancies underscore the complexity of interpreting the clinical relevance of hypogammaglobulinemia, which may be influenced by factors such as nutritional status, disease burden, and treatment modality. The findings of this study further highlight this complexity. The deficiencies in individual immunoglobulin isotypes were primarily associated with a shorter TTFT, without significant impact on PFS or OS. Thus, it is hypothesized that hypogammaglobulinemia at diagnosis may reflect an active disease state, resulting in earlier treatment initiation.

In conclusion, MG in CLL is more than an epiphenomenon. It seems to be interwoven with the molecular and immunologic pathways of disease aggressiveness and treatment resistance. Patients with IgM-type MG-positive CLL are diagnosed at later clinical stages and exhibit distinct IGHV mutation statuses and IGHV segment use. IgM-type MG often denotes a clone with intrinsic survival advantages (through TP53 disruption or NF-κB activation) that diminish dependence on BTK signaling, thereby contributing to BTKi resistance. IFE detection is a simple, accessible, and cost-effective assay that may serve as a clinically relevant biomarker for disease stratification in CLL. Its routine use could enhance risk assessment by identifying biologically aggressive subgroups, thereby supporting more personalized therapeutic strategies. Given the suboptimal response to targeted therapies observed in patients with IgM-MG, alternative or combinatorial treatment approaches are urgently needed to improve outcomes in this high-risk population.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Nature Science Foundation of China (82200215, 82170193, 82170194, and 82370197), the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (2022-I2M-1-022), projects of medical and health technology development program in Shandong province (20220304045414), and the Natural Science Foundation of Dongying (2023ZR028).

Authorship

Contribution: Y. Yan and B.Y. conceived and designed the study, acquired, analyzed, and interpreted the data, and drafted and critically revised the manuscript; T.Q., G.L., W.C., T.W., G.A., and D.Z. critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version of the manuscript; Y. Yu, W.X., and J.L. acquired the data and approved the final version of the manuscript; and L.W. and S.Y. conceived and designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, critically revised the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Shuhua Yi, Institute of Hematology and Blood Diseases Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, 288 Nanjing Rd, Heping District, Tianjin 300020, China; email: yishuhua@ihcams.ac.cn; and Liang Wang, Shengli Oilfield Central Hospital No. 31 Jinan Road Dongying, Shandong Province 257000 China; email: wangliang235@gmail.com.

References

Author notes

Y. Yan, B.Y., and T.Q. contributed equally to this study as joint first authors.

L.W. and S.Y. contributed equally to this study as joint corresponding authors.

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article or the supplemental material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors, Shuhua Yi (yishuhua@ihcams.ac.cn) and Liang Wang (wangliang235@gmail.com).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.