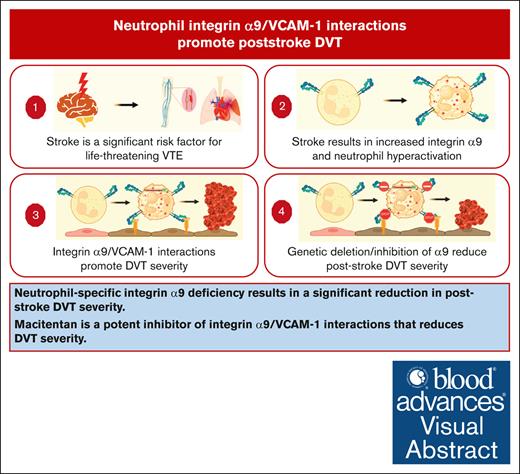

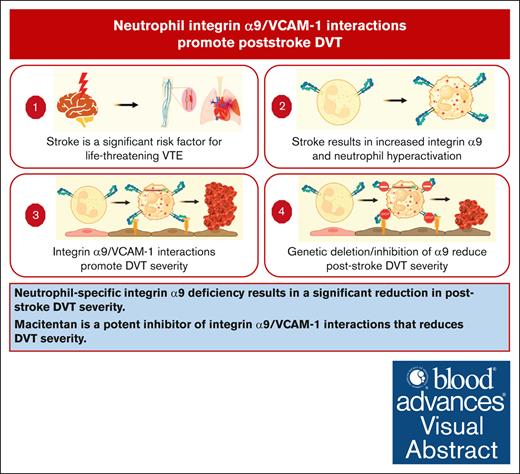

Neutrophil-specific integrin α9 deficiency results in a significant reduction in poststroke DVT severity.

Macitentan is a potent inhibitor of integrin α9/VCAM-1 interactions that reduces DVT severity.

Visual Abstract

Venous thromboembolic events are significant contributors to morbidity and mortality in patients with stroke. Neutrophils are among the first cells in the blood to respond to stroke and are known to promote deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Integrin α9 is a transmembrane glycoprotein highly expressed on neutrophils and stabilizes neutrophil adhesion to activated endothelium via vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1). Nevertheless, the causative role of neutrophil integrin α9 in poststroke DVT remains unknown. Here, we found higher neutrophil integrin α9 and plasma VCAM-1 levels in humans and mice with stroke. Using mice with embolic stroke, we observed enhanced DVT severity in a novel model of poststroke DVT. Neutrophil-specific integrin α9–deficient mice (α9fl/flMrp8Cre+/−) exhibited a significant reduction in poststroke DVT severity along with decreased neutrophils and citrullinated histone H3 in thrombi. Unbiased transcriptomics indicated that α9/VCAM-1 interactions induced pathways related to neutrophil inflammation, exocytosis, NF-κB signaling, and chemotaxis. Mechanistic studies revealed that integrin α9/VCAM-1 interactions mediate neutrophil adhesion at the venous shear rate, promote neutrophil hyperactivation, increase phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase, and induce endothelial cell apoptosis. Using pharmacogenomic profiling, virtual screening, and in vitro assays, we identified macitentan as a potent inhibitor of integrin α9/VCAM-1 interactions and neutrophil adhesion to activated endothelial cells. Macitentan reduced DVT severity in control mice with and without stroke, but not in α9fl/flMrp8Cre+/− mice, suggesting that macitentan improves DVT outcomes by inhibiting neutrophil integrin α9. Collectively, we uncovered a previously unrecognized and critical pathway involving the α9/VCAM-1 axis in neutrophil hyperactivation and DVT.

Introduction

Patients with stroke are at a significant risk of developing life-threatening venous thromboembolic events (VTEs), including deep vein thrombosis (DVT).1-4 Poststroke VTE complications result in worse clinical outcome and are associated with increased rates of in-hospital death and disability, with higher prevalence of in-hospital complications.5 Although pharmacological prophylaxis with anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents can reduce the rates of poststroke VTE, it is associated with a risk of hemorrhagic events including major intracranial bleeding, which may outweigh its benefits.6,7 Given the significant deleterious effects of VTE in patients with stroke, it is imperative to identify novel pathways that can be targeted to reduce poststroke VTE.

Neutrophils are among the first cells in the blood to respond to stroke. In recent years, compelling evidence has emerged implicating neutrophils in the initiation and pathogenesis of DVT.8-26 At the venous shear rate, neutrophils promote thrombus growth through several mechanisms such as the release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs),8,10-13,15,19 secretion of inflammatory mediators,9,10,16 and promotion of endothelial cell activation.27,28 Integrin activation is an essential step for both neutrophil adhesion to activated endothelium and venous thrombus propagation. However, the therapeutic targeting of neutrophil adhesion molecules is associated with neutropenia and an increased rate of infection.29-31 Several adhesion molecules, such as β2 integrins (CD11/CD18), PSGL-1 (CD162), and L-selectin (CD62L), are expressed on all leukocytes; hence, their inhibition may affect innate immunity. In contrast, integrin α9 is highly expressed on neutrophils and expressed at low levels on monocytes, whereas its expression was not detected on lymphocytes and platelets.32-34 Integrin α9 is upregulated upon neutrophil activation and transmigration and is known to stabilize neutrophil adhesion to activated endothelium in synergy with β2 integrin.33,35-37 Integrin α9 binds to multiple ligands, including vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1),35,38 and extracellular matrix proteins including tenascin C, osteopontin, thrombospondin-1, and fibronectin-extra domain A.33,39,40 VCAM-1 canonically participates in the adhesion and transmigration of neutrophils to the activated endothelium and has been suggested as a biomarker for several cardiovascular disorders.41 Importantly, increased plasma VCAM-1 level was independently associated with VTEs.42

We recently demonstrated that neutrophil integrin α9 promotes arterial thrombosis and exacerbates acute ischemic stroke outcomes.32,34,43 However, the role of neutrophil integrin α9 in the pathogenesis of venous thrombosis remains unclear. Considering the relevance of integrin α9 in neutrophil migration,44-46 NETosis,32,34,47 and thromboinflammation,34,43,47 we evaluated the effects of genetic deletion or pharmacological inhibition of integrin α9 on DVT severity using mice with and without stroke. We used neutrophil-specific integrin α9–deficient mice (α9fl/flMrp8Cre+/−), unbiased RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), pharmacogenomic profiling, and virtual screening in combination with in vitro and in vivo experiments to identify pharmacological inhibitors of integrin α9/VCAM-1 interactions.

Methods

Additional methods are available in supplemental Materials.

Mice

Neutrophil-specific integrin α9–deficient mice (α9fl/flMrp8Cre+/−) and littermate controls (α9fl/flMrp8Cre−/−) on a pure C57BL/6J (wild type [WT]) background are described previously.34

IVC stenosis model for DVT and poststroke DVT

The mouse inferior vena cava (IVC) stenosis model of DVT was performed, as previously reported.48-51 Only male mice were used for this model, because ligation in female mice may result in necrosis of the reproductive organs.50,52 Briefly, a midline laparotomy was made, and IVC side branches were ligated. For stenosis, a space holder (30 gauge) was positioned on the outside of the exposed IVC, and a permanent narrowing ligature was placed below the left renal vein. Next, the needle was removed to restrict blood flow to 80% to 90%. To evaluate poststroke DVT, we used an embolic stroke model as we previously reported.43,53 One hour after stroke, DVT was induced by IVC stenosis, and thrombosis was evaluated after 48 hours, as previously reported.48 Only mice that exhibited thrombosis were included to quantify the thrombus weight.

Collection of deidentified stroke and control human neutrophils was approved by the Louisiana State University Health Shreveport institutional review board (protocol number: 0002176) and obtained after informed consent. All animal procedures were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center-Shreveport (P-22-023).

Results

Human and mice with stroke exhibit increased neutrophil integrin α9 levels and higher plasma VCAM-1

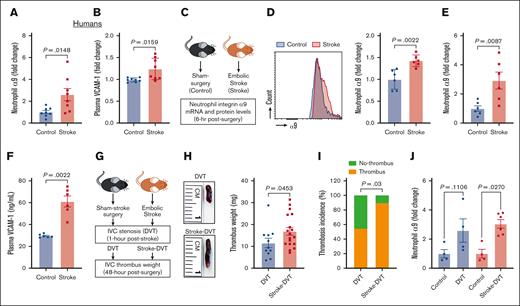

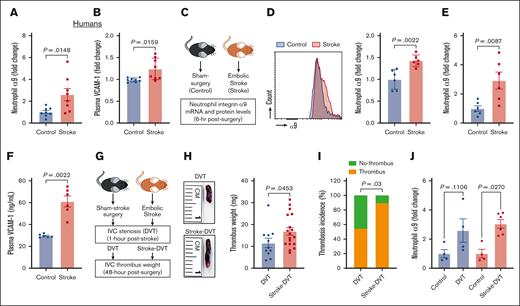

Although previous studies have reported increased integrin α9 levels in activated human neutrophils,37,45 changes in neutrophil integrin α9 levels in patients with stroke have not yet been reported. Here, we determined neutrophils integrin α9 levels from patients with stroke. The baseline demographic data are provided in supplemental Figure 1. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay revealed an approximately threefold increase in integrin α9 levels in neutrophils from patients with stroke compared with controls (Figure 1A). Because VCAM-1 is a ligand of integrin α935,38 and increased plasma VCAM-1 is associated with VTE,42 we next determined plasma VCAM-1 and observed a significant increase in patients with stroke compared with controls (Figure 1B). We have recently reported that stroke induction with a filament model resulted in higher neutrophil integrin α9 levels.34,43 To evaluate the neutrophil integrin α9 levels in the absence of sudden reperfusion, we used an embolic stroke model (Figure 1C), in which a single embolus (∼10 mm) was introduced at the origin of the middle cerebral artery, which closely mimics human thromboembolic stroke.54 Consistent with our previous reports34,43 and human data (Figure 1A), here we observed a significant increase in neutrophil integrin α9 protein (Figure 1D) and messenger RNA expression (Figure 1E), along with increased plasma VCAM-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, and thrombin–antithrombin complex levels (Figure 1F; supplemental Figure 2), in mice with embolic stroke compared with mice with sham surgery. Moreover, stroke also increased vein wall gene expression of Vcam1 (approximately ninefold) and Selp (∼1.2-fold), whereas the expression of Icam1 and Sele did not significantly change compared with controls (supplemental Figure 2).

Stroke leads to increased neutrophil integrin α9, higher plasma VCAM-1 levels, and increased DVT severity. (A) Neutrophil integrin α9 and (B) plasma VCAM-1 levels from patients with stroke and healthy controls. (C) Schematic of experimental design. (D) Representative image of flow-cytometric analysis of integrin α9 for each group (left) and quantification of α9 expression in peripheral neutrophils after stroke or sham surgery in mice (right). (E) Expression of α9 relative to Actb in peripheral neutrophils after stroke or sham surgery. (F) Plasma VCAM-1 levels from mice with stroke and mice with sham surgery. (G) Schematic of experimental design for stroke-DVT studies. (H) Representative IVC thrombus harvested 48 hours after stenosis from each group (left) and thrombus weight (mg; right). Only mice that exhibited thrombosis were included to quantify the thrombus weight. Each dot represents a single mouse. (I) Thrombosis incidence. (J) Expression of α9 relative to Actb in peripheral neutrophils after DVT and stroke-DVT. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) and analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test (A-B,D-F); Fisher exact test (I); and Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the corrected method of Benjamini and Yekutieli (J); n = 8 (A-B); n = 6 (D-F); n = 20 (H-I); and n = 4-6 (J). hr, hour; mRNA, messenger RNA.

Stroke leads to increased neutrophil integrin α9, higher plasma VCAM-1 levels, and increased DVT severity. (A) Neutrophil integrin α9 and (B) plasma VCAM-1 levels from patients with stroke and healthy controls. (C) Schematic of experimental design. (D) Representative image of flow-cytometric analysis of integrin α9 for each group (left) and quantification of α9 expression in peripheral neutrophils after stroke or sham surgery in mice (right). (E) Expression of α9 relative to Actb in peripheral neutrophils after stroke or sham surgery. (F) Plasma VCAM-1 levels from mice with stroke and mice with sham surgery. (G) Schematic of experimental design for stroke-DVT studies. (H) Representative IVC thrombus harvested 48 hours after stenosis from each group (left) and thrombus weight (mg; right). Only mice that exhibited thrombosis were included to quantify the thrombus weight. Each dot represents a single mouse. (I) Thrombosis incidence. (J) Expression of α9 relative to Actb in peripheral neutrophils after DVT and stroke-DVT. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) and analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test (A-B,D-F); Fisher exact test (I); and Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the corrected method of Benjamini and Yekutieli (J); n = 8 (A-B); n = 6 (D-F); n = 20 (H-I); and n = 4-6 (J). hr, hour; mRNA, messenger RNA.

Increased DVT severity after IVC stenosis in mice with stroke

We and others have reported that patients with stroke exhibit a significantly increased risk of VTE.1-3 To establish a mouse model of poststroke DVT, we subjected C57BL/6J (WT) mice to embolic stroke surgery or sham surgery. DVT was induced by IVC stenosis at 1 hour after stoke in both the groups, and thrombosis was evaluated after 48 hours (Figure 1G). We found that mice with stroke exhibited significantly increased DVT severity (increased thrombus weight and thrombosis incidence) compared with mice with sham surgery (Figure 1H-I). Consistently, integrin α9 expression was significantly increased in mice with stroke-DVT (Figure 1J).

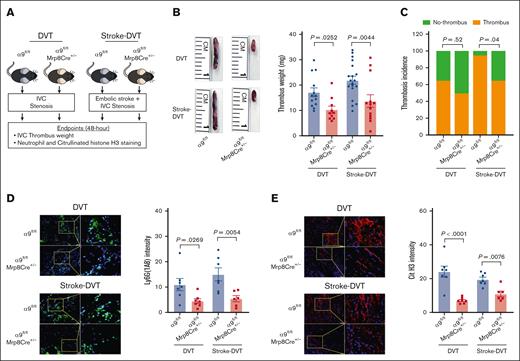

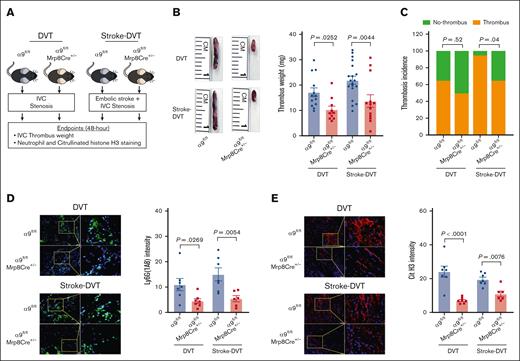

Neutrophil integrin α9 promotes poststroke DVT severity

To evaluate the effect of neutrophil integrin α9 on DVT outcomes, we used neutrophil–specific α9−/− mice (α9fl/fl Mrp8Cre+/−) and littermate controls (α9fl/fl Mrp8Cre−/−; will be referred as α9fl/fl throughout the manuscript). We confirmed the presence of the Mrp8Cre gene using genomic polymerase chain reaction and the deficiency of neutrophil integrin α9 using western blotting (supplemental Figure 3A-C). Neutrophil counts and tail bleeding times were similar between the groups (supplemental Figure 3D-E).

We evaluated DVT outcomes in the absence and presence of stroke using neutrophil–specific α9−/− and α9fl/fl mice (Figure 2A). First, in mice without stroke, we observed a significant IVC thrombus weight compared with that of α9fl/fl mice (Figure 2B), whereas thrombosis incidence was comparable between the groups (Figure 2C). Next, α9fl/fl Mrp8Cre+/− and α9fl/fl mice were subjected to embolic stroke, and DVT outcomes were analyzed 48 hours after IVC stenosis (Figure 2A). Importantly, α9fl/fl Mrp8Cre+/− mice with stroke exhibited significantly reduced DVT severity (lower thrombus weight and thrombosis incidence) compared with α9fl/fl mice with stroke (Figure 2B). Next, we evaluated neutrophil and monocyte infiltration in the IVC thrombi using immunofluorescence and observed that neutrophil–specific α9−/− mice exhibited reduced neutrophil content (Figure 2D) and decreased citrullinated histone H3 expression, a marker of NETs (Figure 2E), along with reduced monocytes and decreased terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase biotin-dUTP nick end labeling-positive cells (supplemental Figure 4A-B; stroke-DVT group) in IVC thrombi. Collectively, these data suggest that integrin α9 promotes DVT severity by increasing neutrophil and monocyte influx after IVC stenosis. We have previously reported that neutrophil integrin α9 mediates platelet aggregation.32 Here, we evaluated platelet-neutrophil aggregates after stroke-DVT surgery. As shown in supplemental Figure 5, platelet-neutrophil aggregates (%) were comparable in α9fl/fl and α9fl/flMrp8Cre+/− mice, thus ruling out the possibility that neutrophil α9 deficiency could affect platelet-neutrophil aggregates. Next, to evaluate whether neutrophil integrin α9 also mediated DVT severity after complete ligation of IVC, we performed a stasis model using α9fl/fl and α9fl/flMrp8Cre+/− mice. As shown in supplemental Figure 6, thrombus weight and thrombosis incidence were comparable between the groups, suggesting neutrophil integrin α9 deficiency does not affect DVT severity in the IVC stasis model.

Neutrophil integrin α9 promotes poststroke DVT severity. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Representative IVC thrombus harvested 48 hours after stenosis from each group (left) and thrombus weight (mg; right). Only mice that exhibited thrombosis were included to quantify the thrombus weight. Each dot represents a single mouse. (C) Thrombosis incidence. (D) Representative cross-sectional immunofluorescence image (left) of the isolated IVC thrombus (48 hours after stenosis) from each group for Ly6G (neutrophils, green) and DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; blue); magnification, 20×; scale bar, 50 μm; and quantification (right). (E) Representative cross-sectional immunofluorescence image (left) of the isolated IVC thrombus (48 hours after stenosis) from each group for the antihistone H3 (citrulline R2 + R8 + R17) (NETs, red) and DAPI (blue); magnification, 20×; scale bar, 50 μm; and quantification (right). Data are mean ± SEM and analyzed by repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the corrected method of Benjamini and Yekutieli (B,D-E); and Fisher exact test (C); n = 20 (B-C); and n = 6-7 (D-E). Cit H3, citrullinated histone H3; DAPI, 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Neutrophil integrin α9 promotes poststroke DVT severity. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Representative IVC thrombus harvested 48 hours after stenosis from each group (left) and thrombus weight (mg; right). Only mice that exhibited thrombosis were included to quantify the thrombus weight. Each dot represents a single mouse. (C) Thrombosis incidence. (D) Representative cross-sectional immunofluorescence image (left) of the isolated IVC thrombus (48 hours after stenosis) from each group for Ly6G (neutrophils, green) and DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; blue); magnification, 20×; scale bar, 50 μm; and quantification (right). (E) Representative cross-sectional immunofluorescence image (left) of the isolated IVC thrombus (48 hours after stenosis) from each group for the antihistone H3 (citrulline R2 + R8 + R17) (NETs, red) and DAPI (blue); magnification, 20×; scale bar, 50 μm; and quantification (right). Data are mean ± SEM and analyzed by repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the corrected method of Benjamini and Yekutieli (B,D-E); and Fisher exact test (C); n = 20 (B-C); and n = 6-7 (D-E). Cit H3, citrullinated histone H3; DAPI, 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

To rule out the possibility of nonspecific effects of Mrp-Cre recombinase expression on DVT outcomes, we subjected the α9fl/fl and α9+/+Mrp8Cre+/− mice to IVC stenosis. IVC thrombus weight was comparable between α9fl/fl and α9+/+Mrp8Cre+/− mice (supplemental Figure 7), suggesting minimal off-target effects of Mrp8-Cre recombinase.

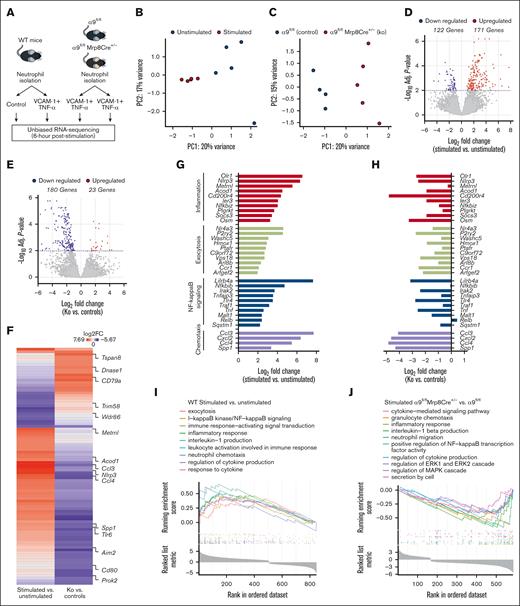

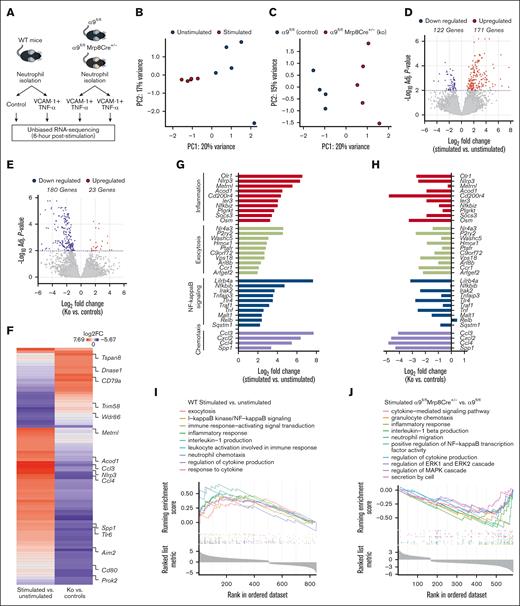

Unbiased transcriptomic revealed integrin α9/VCAM-1 interactions promote gene expressions related to neutrophil inflammation, exocytosis, NF-κB signaling, and chemotaxis

Integrin α9 is known to mediate adhesion and migration via VCAM-1.33 To evaluate the changes in the neutrophil transcriptional response after integrin α9/VCAM-1 interactions, we performed unbiased RNA-seq of (1) WT neutrophils (unstimulated and stimulated with VCAM-1 and tumor necrosis factor-α [TNF-α]); and (2) stimulated neutrophils from α9fl/fl and α9fl/flMrp8Cre+/− mice (Figure 3A). To mimic in vivo conditions, we used VCAM-1 and TNF-α to stimulate neutrophils that induced robust neutrophil hyperactivation (supplemental Figure 8).

Integrin α9 and VCAM-1 interactions promote gene expressions related to neutrophil inflammation, exocytosis, NF-κB signaling, and chemotaxis. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Principal component analysis was performed based on RNA-seq of stimulated and unstimulated WT neutrophils and (C) stimulated neutrophils from littermate controls and neutrophil–specific integrin α9−/− mice. (D) Volcano plots of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) based on RNA-seq analysis of stimulated and unstimulated WT neutrophils and (E) stimulated neutrophils from littermate controls and neutrophil–specific integrin α9−/− mice. (F) Log fold-change of all the shared DEGs from stimulated and unstimulated WT neutrophils and stimulated neutrophils from littermate controls and neutrophil–specific integrin α9−/− mice. (G) Log fold-change of selected genes from DEGs of stimulated and unstimulated WT neutrophils. (H) Log fold-change of selected genes from DEGs of neutrophils from littermate controls and neutrophil–specific integrin α9−/− mice. (I) GSEA was performed based on RNA-seq of stimulated and unstimulated WT neutrophils and (J) stimulated neutrophils from littermate controls and neutrophil–specific integrin α9−/− mice. The significance of the enriched pathways was determined by right-tailed Fisher exact test followed by Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing adjustment; n = 5 (B,D,G,I); and n = 4-5 (C,E,F,H,J). GSEA, gene set enrichment analysis.

Integrin α9 and VCAM-1 interactions promote gene expressions related to neutrophil inflammation, exocytosis, NF-κB signaling, and chemotaxis. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Principal component analysis was performed based on RNA-seq of stimulated and unstimulated WT neutrophils and (C) stimulated neutrophils from littermate controls and neutrophil–specific integrin α9−/− mice. (D) Volcano plots of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) based on RNA-seq analysis of stimulated and unstimulated WT neutrophils and (E) stimulated neutrophils from littermate controls and neutrophil–specific integrin α9−/− mice. (F) Log fold-change of all the shared DEGs from stimulated and unstimulated WT neutrophils and stimulated neutrophils from littermate controls and neutrophil–specific integrin α9−/− mice. (G) Log fold-change of selected genes from DEGs of stimulated and unstimulated WT neutrophils. (H) Log fold-change of selected genes from DEGs of neutrophils from littermate controls and neutrophil–specific integrin α9−/− mice. (I) GSEA was performed based on RNA-seq of stimulated and unstimulated WT neutrophils and (J) stimulated neutrophils from littermate controls and neutrophil–specific integrin α9−/− mice. The significance of the enriched pathways was determined by right-tailed Fisher exact test followed by Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing adjustment; n = 5 (B,D,G,I); and n = 4-5 (C,E,F,H,J). GSEA, gene set enrichment analysis.

Quantitative measurement of total neutrophil messenger RNA expression at 6 hours after stimulation showed distinct transcriptional profiles elicited between stimulated and unstimulated WT neutrophils (Figure 3B), as well as between stimulated neutrophils of α9fl/fl and α9fl/flMrp8Cre+/− mice (Figure 3C). Statistical analysis of differential gene expression (adjusted P < .01) revealed 171 genes that were upregulated, whereas the expression of 122 genes were downregulated in stimulated WT neutrophils compared with unstimulated WT neutrophils, for a total of 293 differentially expressed genes (Figure 3D). In the case of stimulated neutrophils from α9fl/flMrp8Cre+/− mice, we found 23 genes were upregulated, and 180 were downregulated compared with stimulated neutrophils from α9fl/fl mice (Figure 3E). Hierarchical clustering of gene expression revealed gene clusters that were significantly changed in both groups (supplemental Figure 9A-B). The top 20 significantly altered genes are shown in supplemental Figure 10. All shared differentially expressed genes and their fold-changes in both groups are shown in Figure 3F and supplemental Table 1. Genes found to be increased in stimulated WT neutrophils were associated with inflammation, exocytosis, NF-κB signaling, and chemotaxis (Figure 3G), several of which were significantly downregulated in stimulated neutrophils isolated from α9fl/flMrp8Cre+/− mice (Figure 3H).

In the case of stimulated WT neutrophils, gene ontology (GO) enrichment revealed that highly upregulated genes corresponded to biological processes involved in exocytosis, I-κB kinase/NF-κB signaling, inflammatory response, leukocyte activation, interleukin-1 production, neutrophil chemotaxis, and response to cytokine (Figure 3I). Importantly, GO enrichment of stimulated neutrophils from α9fl/flMrp8Cre+/− mice revealed that highly downregulated genes corresponded to biological processes involved in the cytokine-mediated signaling pathway, granulocyte chemotaxis, regulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 (ERK1) and ERK2 cascade, regulation of MAPK cascade, inflammatory response, and secretion by cells (Figure 3J). The top 10 significantly upregulated pathways in stimulated WT neutrophils and the top 10 significantly downregulated pathways in stimulated neutrophils from α9fl/flMrp8Cre+/− mice are shown in supplemental Figure 11A-B. The adjusted P values of the relevant GO pathways of stimulated WT neutrophils and stimulated neutrophils from α9fl/flMrp8Cre+/− mice are shown in supplemental Figure 12A-B.

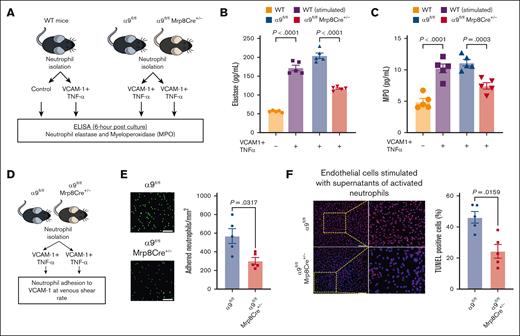

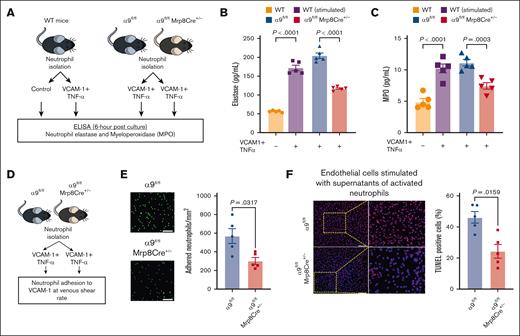

Integrin α9/VCAM-1 interactions promote neutrophil hyperactivation, mediate neutrophil adhesion, induce endothelial cell apoptosis, and enhance DVT severity

Because our transcriptomics data suggested that integrin α9/VCAM-1 interactions promote neutrophil hyperactivation, we next evaluated the effect of integrin α9 and VCAM-1 interactions on the release of neutrophil elastase and myeloperoxidase (MPO) (Figure 4A). First, using WT neutrophils, we found that neutrophils incubated with VCAM-1 and TNF-α (stimulated) exhibited significantly increased secretion of elastase and MPO compared with unstimulated WT neutrophils (Figure 4B-C). To evaluate the effect of neutrophil integrin α9 deficiency, we stimulated neutrophils isolated from α9fl/fl and α9fl/flMrp8Cre+/− mice and found that α9−/− neutrophils exhibited significantly reduced release of elastase and MPO compared with controls (Figure 4B-C). Because integrin α9 engagement is reported to activate the ERK pathway,34,55,56 we next evaluated ERK phosphorylation using western blotting and observed that stimulated neutrophils from α9fl/flMrp8Cre+/− mice exhibited reduced ERK phosphorylation compared with those from α9fl/fl mice (supplemental Figure 13A). To evaluate the role of ERK pathway in α9/VCAM-1–mediated neutrophil activation, we pretreated neutrophils with U0160 (10 μm, an inhibitor of the ERK pathway). Consistent with our previous study,34 we observed that U0160 inhibited elastase release from stimulated control neutrophils but not from stimulated neutrophils of α9fl/flMrp8Cre+/− mice (supplemental Figure 13B).

Interactions between integrin α9 and VCAM-1 promote neutrophil hyperactivation, mediate neutrophil adhesion at venous shear rate, and enhance endothelial cell apoptosis. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Elastase and (C) MPO levels in cell-culture media 6 hours after stimulation. (D) Experimental design. (E) Representative images of the neutrophil adhesion to the VCAM-1 coated slides at venous shear rate (left); magnification, 20×; scale bar, 50 μm; and qualification (right). (F) Representative cross-sectional immunofluorescence image of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase biotin-dUTP nick end labeling-positive mouse endothelial cells incubated with cell supernatant of stimulated neutrophils from α9fl/fl and α9fl/flMrp8Cre+/− mice (left); and quantification (right); magnification, 10×; scale bar, 100 μm. Data are mean ± SEM and analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA followed by the corrected method of Benjamini and Yekutieli (B-C) or the Mann-Whitney test (E-F); n = 5 (B-C); n = 5 (E); and n = 5 (F).

Interactions between integrin α9 and VCAM-1 promote neutrophil hyperactivation, mediate neutrophil adhesion at venous shear rate, and enhance endothelial cell apoptosis. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Elastase and (C) MPO levels in cell-culture media 6 hours after stimulation. (D) Experimental design. (E) Representative images of the neutrophil adhesion to the VCAM-1 coated slides at venous shear rate (left); magnification, 20×; scale bar, 50 μm; and qualification (right). (F) Representative cross-sectional immunofluorescence image of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase biotin-dUTP nick end labeling-positive mouse endothelial cells incubated with cell supernatant of stimulated neutrophils from α9fl/fl and α9fl/flMrp8Cre+/− mice (left); and quantification (right); magnification, 10×; scale bar, 100 μm. Data are mean ± SEM and analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA followed by the corrected method of Benjamini and Yekutieli (B-C) or the Mann-Whitney test (E-F); n = 5 (B-C); n = 5 (E); and n = 5 (F).

Neutrophils adhesion to the activated endothelium is an essential step for venous thrombus propagation.8-16 Integrin α9/VCAM-1 interactions are known to mediate cell adhesion.33 To evaluate the effect of integrin α9 deficiency on neutrophil adhesion to VCAM-1 at the venous shear rate, we perfused isolated neutrophils (using the ibidi flow system; Figure 4D) from α9fl/fl and α9fl/flMrp8Cre+/− mice and observed that neutrophil integrin α9 deficiency resulted in significantly reduced adhesion to VCAM-1 at the venous shear rate (Figure 4E).

Apoptosis of vascular endothelial cells is a key event in DVT initiation, and neutrophils and NETs are known to promote endothelial cell apoptosis.57,58 To evaluate the effects of integrin α9 deficiency on neutrophil-mediated endothelial cell apoptosis, we added the cell supernatants of stimulated neutrophils from α9fl/fl and α9fl/flMrp8Cre+/− mice to mouse venous endothelial cells and evaluated apoptosis. We observed that the supernatants from stimulated α9−/− neutrophils exhibited significantly reduced endothelial cell apoptosis (Figure 4F), along with reduced expression of key apoptotic and inflammatory genes (Casp3 and Nlrp3) (supplemental Figure 14).

Next, to evaluate the in vivo role of integrin α9/VCAM-1 signaling, we treated WT mice and α9fl/flMrp8Cre+/− mice with anti–VCAM-1 antibody and evaluated DVT outcomes. As shown in supplemental Figure 15, anti–VCAM-1 antibody treatment significantly reduced thrombus weight and thrombosis incidence in WT mice but not in α9fl/flMrp8Cre+/− mice, suggesting the in vivo functional role of α9/VCAM-1 axis in the pathogenesis of DVT.

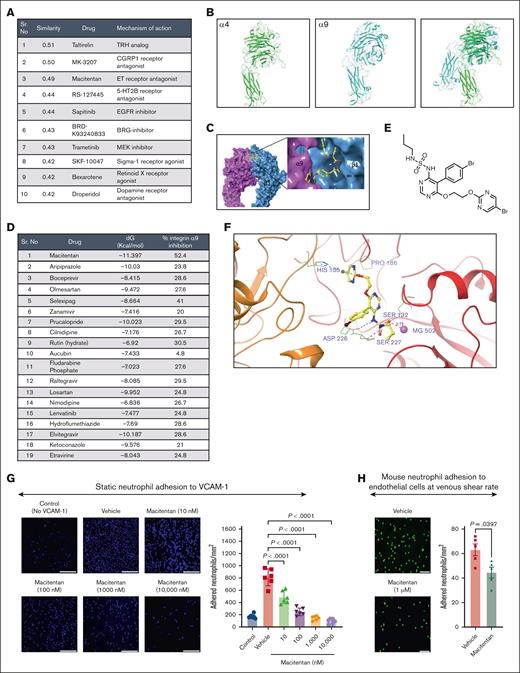

Pharmacogenomic profiling and virtual screening revealed macitentan as a potent inhibitor of the integrin α9/VCAM-1 interactions

To identify potential pharmacological agents that can produce similar gene signatures, first we used the Library of Integrated Network-based Cellular Signatures (LINCS).59 The log2(fold-change) (logFC) and P value for top L1000 genes were extracted from differentially expressed gene analysis of stimulated neutrophils of α9fl/fl and α9fl/flMrp8Cre+/− mice and submitted as an input to inquire a list of the chemical perturbagens altering the gene expression from integrative library of integrated network-based cellular signatures (iLINCS) portal. The top 10 concordant perturbagens with concordance scores >0.321 are shown in Figure 5A.

Pharmacogenomic profiling and virtual screening revealed macitentan as a potent inhibitor of the integrin α9/VCAM-1 interaction. (A) The top 10 concordant perturbagens with concordance scores >0.321 are shown using iLINCS portal based on RNA-seq of neutrophils of littermate controls and neutrophil–specific integrin α9−/− mice. (B) The template (green, α4 subunit) and target (cyan, α9 subunit) models. (C) The predicted α9β1 structure with an inhibitor. (D) List of top-19 compounds with binding energy and percentage inhibition of integrin α9 to VCAM-1. (E) Chemical structure of macitentan. (F) Docked pose of macitentan with integrin α9β1. (G) Representative images of neutrophil adhesion to VCAM-1 in presence of different concentration of macitentan (left); magnification, 10×; scale bar, 100 μm; and quantification (right). (H) Representative images of the mouse neutrophil adhesion to the activated mouse venous endothelial cells coated slides at venous shear rate (left); magnification, 20×; scale bar, 50 μm; and qualification (right). Data are mean ± SEM and analyzed by 1-way ANOVA followed by Sidak multiple comparisons test (G) or Mann-Whitney test (H); n = 6 (G); and n = 5 (H).

Pharmacogenomic profiling and virtual screening revealed macitentan as a potent inhibitor of the integrin α9/VCAM-1 interaction. (A) The top 10 concordant perturbagens with concordance scores >0.321 are shown using iLINCS portal based on RNA-seq of neutrophils of littermate controls and neutrophil–specific integrin α9−/− mice. (B) The template (green, α4 subunit) and target (cyan, α9 subunit) models. (C) The predicted α9β1 structure with an inhibitor. (D) List of top-19 compounds with binding energy and percentage inhibition of integrin α9 to VCAM-1. (E) Chemical structure of macitentan. (F) Docked pose of macitentan with integrin α9β1. (G) Representative images of neutrophil adhesion to VCAM-1 in presence of different concentration of macitentan (left); magnification, 10×; scale bar, 100 μm; and quantification (right). (H) Representative images of the mouse neutrophil adhesion to the activated mouse venous endothelial cells coated slides at venous shear rate (left); magnification, 20×; scale bar, 50 μm; and qualification (right). Data are mean ± SEM and analyzed by 1-way ANOVA followed by Sidak multiple comparisons test (G) or Mann-Whitney test (H); n = 6 (G); and n = 5 (H).

To identify small molecules that can effectively and safely inhibit integrin α9/VCAM-1 interactions, we used a database of the US Food and Drug Administration–approved small molecules and performed computational modeling, docking, and virtual screening. The α9β1 crystal structure is unavailable, therefore we used homology modeling to build an atomistic model. Figure 5B shows the template (green, α4 subunit) and target (cyan, α9 subunit) models, and Figure 5C shows the predicted α9β1 structure with an inhibitor. Based on the docking score (free energy of binding, dG) and number of interactions, we selected the top 19 compounds and performed a cell-free assay to analyze the percentage inhibition of integrin α9 binding to VCAM-1 (Figure 5D; supplemental Figure 16). Based on these results and our iLINCS portal data (Figure 5A), we selected macitentan for further studies. Macitentan is an endothelin receptor antagonist and approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the management of pulmonary arterial hypertension.60Figure 5E shows the chemical structure of macitentan, and Figure 5F shows the docked pose of macitentan with integrin α9β1. Next, we evaluated whether macitentan could also bind to α4β1. As shown in supplemental figure 17, the binding energy of macitentan to α4β1 is very low (–6.922 kcal/mol), suggesting a loose binding. The binding energy of macitentan to α9β1 was –11.397 kcal/mol (Figure 5D), which means that macitentan is highly selective to α9 compared with α4. We then tested the ability of macitentan to inhibit neutrophil adhesion to VCAM-1. We observed that macitentan dose-dependently reduced neutrophil adhesion to VCAM-1, with an IC50 value of 12.3 nM (Figure 5G). Next, we determined the ability of macitentan to inhibit neutrophil adhesion to activated endothelium at the venous shear rate. We observed that macitentan significantly inhibited mouse and human neutrophil adhesion to activated endothelium at the venous shear rate (Figure 5H; supplemental Figure 18). Collectively, these data suggest that macitentan is a potent inhibitor of integrin α9 and VCAM-1 interactions and significantly inhibits neutrophil adhesion to VCAM-1 as well as to activated endothelial cells.

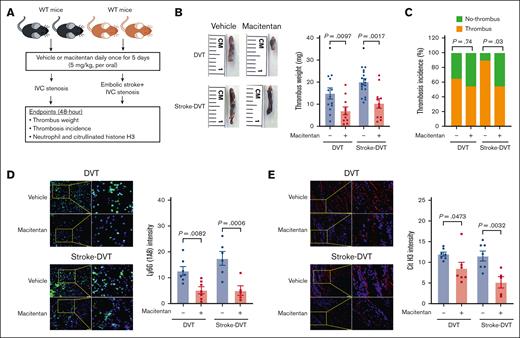

Macitentan pretreatment reduces DVT severity in mice via neutrophil integrin α9

Having observed significantly reduced neutrophil adhesion, we next evaluated the in vivo efficacy of macitentan in reducing DVT severity in the absence and presence of stroke. The approved dose of macitentan for humans is 10 mg; converting it to the mouse equivalent dose resulted in a dose of ∼2 mg/kg.61 Accordingly, we treated WT mice with macitentan at a dose of 2 and 5 mg/kg or an equivalent volume of vehicle for 5 days. We found that macitentan at the dose of 2 mg/kg did not reduce DVT severity (supplemental Figure 19), whereas the 5 mg/kg dose of macitentan significantly reduced thrombus weight (Figure 6A-C). Importantly, mice treated with macitentan (5 mg/kg) also exhibited significantly reduced DVT severity in the presence of stroke (Figure 6D-E), which was concomitant with a significant reduction in plasma elastase and MPO (supplemental Figure 20), as well as neutrophil and citrullinated histone H3 content in the IVC thrombus (Figure 6D-E). To evaluate the effect of macitentan on coagulations parameters, blood counts, and gene expression of endothelial adhesion molecules, we collected plasma samples and harvested IVC samples 6 hours after DVT in WT mice treated with macitentan or vehicle. Circulating neutrophils, monocytes, and platelets, plasma VCAM-1, fibrinogen, thrombin-antithrombin complex, and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, and IVC gene expression of Icam1, Selp, and Sele were comparable between the groups (supplemental Figure 21).

Macitentan pretreatment reduces poststroke DVT severity. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Representative IVC thrombus harvested 48 hours after stenosis from each group (left); and thrombus weight (mg; right). Only mice that exhibited thrombosis were included to quantify the thrombus weight. Each dot represents a single mouse. (C) Thrombosis incidence. (D) Representative cross-sectional immunofluorescence image (left) of the isolated IVC IVC thrombus (48 hours after stenosis) from each group for Ly6G (neutrophils, green) and DAPI (blue). magnification, 20×; scale bar, 50 μm; and quantification (right). (E) Representative cross-sectional immunofluorescence image (left) of the isolated IVC thrombus (48 hours after stenosis) from each group for the antihistone H3 (citrulline R2 + R8 + R17) (NETs, red) and DAPI (blue); magnification, 20×; Scale bar, 50 μm; and quantification (right). Data are mean ± SEM and analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA followed by the corrected method of Benjamini and Yekutieli (B,D,E) or Fisher exact test (C); n = 20 (B-C); and n = 5-6 (D-E). DAPI, 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Macitentan pretreatment reduces poststroke DVT severity. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Representative IVC thrombus harvested 48 hours after stenosis from each group (left); and thrombus weight (mg; right). Only mice that exhibited thrombosis were included to quantify the thrombus weight. Each dot represents a single mouse. (C) Thrombosis incidence. (D) Representative cross-sectional immunofluorescence image (left) of the isolated IVC IVC thrombus (48 hours after stenosis) from each group for Ly6G (neutrophils, green) and DAPI (blue). magnification, 20×; scale bar, 50 μm; and quantification (right). (E) Representative cross-sectional immunofluorescence image (left) of the isolated IVC thrombus (48 hours after stenosis) from each group for the antihistone H3 (citrulline R2 + R8 + R17) (NETs, red) and DAPI (blue); magnification, 20×; Scale bar, 50 μm; and quantification (right). Data are mean ± SEM and analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA followed by the corrected method of Benjamini and Yekutieli (B,D,E) or Fisher exact test (C); n = 20 (B-C); and n = 5-6 (D-E). DAPI, 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

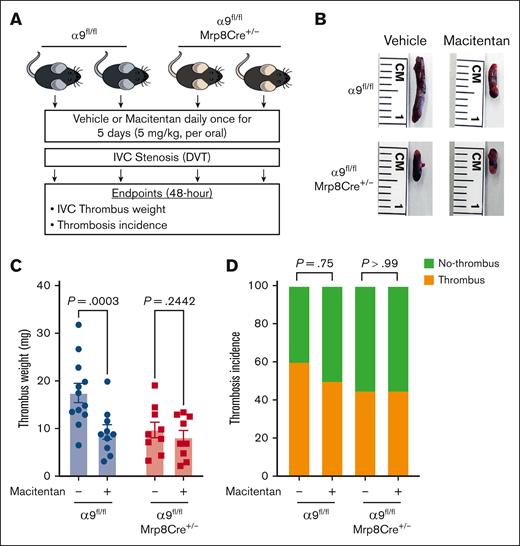

To determine whether the positive effects of macitentan on DVT outcomes are mediated via neutrophil integrin α9, first we evaluated neutrophil adhesion to the activated endothelial cells at the venous shear rate. We treated isolated neutrophils of controls and neutrophil–specific α9−/− mice with either macitentan or vehicle. Macitentan significantly reduced adhesion of control neutrophils but did not change α9−/− neutrophil adhesion (supplemental Figure 22). Next, we treated neutrophil–specific α9−/− mice and littermate controls with macitentan or vehicle for 5 days and performed DVT surgeries (Figure 7A). We found that macitentan treatment significantly reduced the DVT severity in littermate control mice but not in neutrophil–specific α9−/− mice (Figure 7B-D). Comparable neutrophil adhesion and DVT outcomes in the macitentan-treated neutrophil–specific α9−/− mice and vehicle-treated neutrophil–specific α9−/− mice suggested that macitentan most likely reduces DVT severity by inhibiting neutrophil integrin α9. However, the possibility that macitentan can reduce DVT severity via other mechanisms cannot be completely ruled out.

The positive effects of macitentan on DVT outcomes are, at least in part, mediated by neutrophil integrin α9. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Representative IVC thrombus harvested 48-hour post-stenosis from each group. (C) Thrombus weight (mg). Only mice that exhibited thrombosis were included to quantify the thrombus weight. Each dot represents a single mouse. (D) thrombosis incidence. Data are mean ± SEM and analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA followed by the corrected method of Benjamini and Yekutieli (C) or Fisher exact test (D); n = 20 (C-D).

The positive effects of macitentan on DVT outcomes are, at least in part, mediated by neutrophil integrin α9. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Representative IVC thrombus harvested 48-hour post-stenosis from each group. (C) Thrombus weight (mg). Only mice that exhibited thrombosis were included to quantify the thrombus weight. Each dot represents a single mouse. (D) thrombosis incidence. Data are mean ± SEM and analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA followed by the corrected method of Benjamini and Yekutieli (C) or Fisher exact test (D); n = 20 (C-D).

Discussion

Over the last decade, several studies have implicated neutrophils and their integrins in the initiation and development of DVT.8-26 Despite the known association of neutrophil hyperactivation in stroke as well as in DVT, the contribution of neutrophil integrin α9 to the pathogenesis of DVT remains unknown. Previous studies by us and others have shown a key role of integrin α9 in the modulation of arterial thrombosis,32 stroke,34,43 rheumatoid arthritis,62,63 cancer,64-66 and vascular remodeling.67,68 Here, using genetic and pharmacological approaches in combination with transcriptomics, pharmacogenomic profiling, and virtual screening, we uncovered a previously unknown pathway involving integrin α9 and VCAM-1 in promoting DVT. We found that integrin α9-VCAM1 interactions are critical for neutrophil hyperactivation, and pharmacological inhibition of these interactions significantly reduced DVT severity.

In the context of DVT, the role of neutrophil-endothelium interactions has been well characterized, and these interactions are critical for the development of venous thrombi.10,12,14,16 Endothelial VCAM-1 is known to mediate leukocyte adhesion.41,42 The binding of neutrophil integrin α9 to VCAM-1 activates NF-κB and is important for enhancing neutrophil survival in inflammatory microenvironments.35 In human neutrophils, integrin α9 promotes the activation of the PI3K and MAPK-ERK signaling pathways and NF-κB nuclear translocation, which results in the spontaneous delay of cell apoptosis.56 In agreement with these reports, our current data suggest that integrin α9 and VCAM-1 interactions promote the activation of ERK pathways, facilitate neutrophil adhesion at the venous shear rate, and mediate the release of neutrophil elastase and MPO. Neutrophil-mediated endothelial cell injury plays an important role in several inflammatory conditions such as vasculitis and atherosclerosis.57,58 Activated neutrophils release free radicals, proteases such as elastase and MPO, and cytokines that cause endothelial damage.28 Interestingly, thrombosis can be provoked by endothelial cell apoptosis,27 and endothelial activation is a critical step in the pathogenesis of venous thrombosis.69,70 Here, we observed that cell supernatants from activated neutrophils of α9−/− exhibited significantly reduced venous endothelial cell apoptosis, along with reduced expression of key apoptotic and inflammatory genes, suggesting that neutrophil integrin α9 may support venous thrombus formation by promoting endothelial cell apoptosis. Collectively, our data clearly support the mechanistic role of the integrin α9/VCAM-1 axis in the regulation of neutrophil recruitment and hyperactivation during venous thrombosis.

The conventional belief that neutrophils are short-lived effector cells with limited plasticity has recently been challenged by the extreme diversity of neutrophils in vivo, which reflects the rates of cell mobilization, differentiation, and exposure to environmental signals.71 Single-cell RNA-seq of mouse IVC revealed neutrophils as one of the predominant cell types within the vessel wall after IVC ligation, and significantly upregulated genes related to inflammatory processes, oxidative stress, and cell death were observed in neutrophils.72 In line with these observations, VCAM-1 exposure to α9−/−-deficient neutrophil resulted in significantly reduced expression of genes associated with neutrophil inflammation. Based on these and published findings, we propose a mechanistic role for the integrin α9/VCAM-1 axis in the pathogenesis of DVT.

Our proof-of-concept preclinical studies showed that neutrophil integrin α9–deficient mice exhibited reduced DVT severity, suggesting that integrin α9 may be therapeutically targeted to reduce VTE. However, new drug development is a daunting task that can take several years, cost billions of dollars, and have high failure rates. Conversely, drug repurposing is an attractive strategy for identifying new indications for approved agents. In recent years, large-scale drug-perturbation experiments have enabled pharmacogenomic-based screening of approved agents.59,73,74 Based on the pharmacogenomic profiling, in silico, and in vitro findings, we found that macitentan is a potent inhibitor of the integrin α9/VCAM-1 interaction. Consistent with the reported anti-inflammatory effects of macitentan,75,76 we found that macitentan inhibited neutrophil adhesion to the activated endothelium at the venous shear rate and reduced DVT severity. Several studies have shown that the pharmacological inhibition of integrin α9 using an anti-integrin α9 antibody improves stroke outcomes,34,43 reduces the severity of rheumatoid arthritis,62,63 inhibits arterial thrombosis,32 and regulates injury-induced neointimal hyperplasia.67 However, we believe that targeting integrin α9 with a small-molecule inhibitor, macitentan, provides additional advantages over antibody-based approaches, such as already established safety profile, oral administration, economic affordability, and low chances of immunogenicity. The results of a previously published systematic review and meta-analysis show that despite a beneficial effect on angiographic vasospasm, endothelin receptor antagonists do not affect functional outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage and do not affect the incidence of vasospasm-related cerebral infarction, any new cerebral infarction, or case fatality.77 In a rat model of middle cerebral artery occlusion, pretreatment with endothelin receptor antagonist had no effect on regional cerebral blood flow and subsequent hemispheric volume of ischemic damage.78 These reports suggest that the possibility of adverse stroke outcomes after macitentan treatment are minimal.

Despite its strengths, our study has limitations. For example, neutrophils represent the majority of white blood cells in human blood but are less common in mouse blood.79 Moreover, several cytokines and chemokines are differentially expressed in mice and human neutrophils,80,81 suggesting that these findings should be confirmed in future clinical trials. Another limitation is that we only used healthy mice and evaluated DVT severity by thrombus weight and thrombosis incidence. Future studies should evaluate the effects of neutrophil-specific integrin α9 deficiency on DVT outcomes in older mice82,83 and with functionally relevant outcomes such as IVC patency and embolism. In conclusion, our study unequivocally supports the mechanistic role of neutrophil integrin α9 in modulating DVT severity via its interactions with VCAM-1.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Center for Cardiovascular Diseases and Sciences for the use of their hematology analyzer, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center Shreveport Research Core Facility for the flow cytometry service (RRID:SCR_024775), and the Center of Applied Immunology and Pathological Processes Immunophenotyping (RRID:SCR_024781) and Modeling Cores (RRID:SCR_024779) funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS; P20GM134974) for their advice on the flow cytometry and RNA sequencing data analysis.

The authors acknowledge support from the NIH, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) HL158546 (N.D.), NHLBI HL150233, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) DK134011 and NIDDK DK136685 (O.R.), NHLBI HL145753, NHLBI HL145753–01S1, and NHLBI HL145753–03S1 (M.S.B.), NIGMS P20 GM121307, NHLBI HL133497, and NHLBI HL141155 (A.W.O.), and Institutional Development Award Idea, (NIGMS 2P20GM121307-06: T.M.), NHLBI T32HL155022 (M.B. and K.Y.S.), the Career Development Award from American Heart Association (AHA; 20CDA3560123 [N.D.]), 20CDA852609 (T.M.); and 21CDA853487 (M.A.), and the AHA postdoctoral fellowship (24POST1199551; H.K.).

Authorship

Contribution: N.P., H.K., M.R.C., S.K.A., L.C., M.B., R.A., S.J.G., X.S., J.W., X.Z., and M.A.N.B. conducted experiments, analyzed data, and edited the manuscript; M.A., M.S.B., A.W.O., T.M., K.B., and K.Y.S. interpreted the data and edited the manuscript; P.B., P.R., R.S., H.C., and J.D.J. enrolled patients with stroke, interpreted the data, and edited the manuscript; O.R. interpreted and analyzed the data and contributed to the writing of the manuscript; and N.D. acquired funding for the research, designed the study, conducted experiments, analyzed the data, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Nirav Dhanesha, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center-Shreveport, Department of Pathology and Translational Pathobiology, 1501 Kings Highway, BRI F7-26, Shreveport, LA 71103; email: nirav.dhanesha@lsuhs.edu.

References

Author notes

RNA sequencing data are available at Sequence Read Archive database (submission ID: SUB1374990).

Original data are available on request from the corresponding author, Nirav Dhanesha (nirav.dhanesha@lsuhs.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.