Key Points

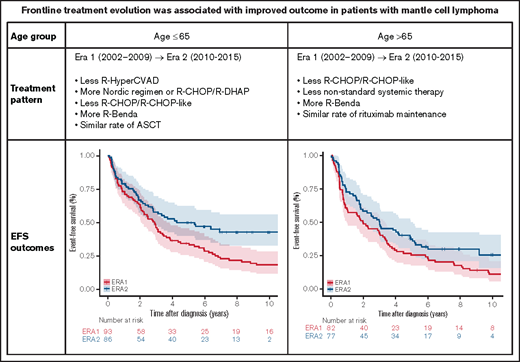

The pattern of frontline treatment of MCL has evolved in both younger and older patients from 2002-2009 to 2010-2015.

The change in frontline treatment was associated with improved EFS and OS in younger patients and improved EFS in older patients.

Abstract

Because there have been a dvances in frontline treatment for mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) over the last 2 decades, we sought to characterize the changes in frontline treatment patterns and their association with outcomes. Patients with newly diagnosed MCL from September 2002 through June 2015 were enrolled in a prospective cohort study, and clinical characteristics, treatment, and clinical outcomes were compared between patients diagnosed from 2002 to 2009 (Era 1) compared with 2010 to 2015 (Era 2). Patient age, sex, and simplified MCL International Prognostic Index (sMIPI) score were similar between the 2 groups. In patients age 65 years or younger, there was less use of rituximab plus hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (R-Hyper-CVAD) (16.1% vs 8.8%) but more use of rituximab plus maximum-strength cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-maxi-CHOP) alternating with rituximab plus high-dose cytarabine (R-HiDAC), also known as the Nordic regimen, and R-CHOP alternating with rituximab plus dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin (R-DHAP) (1.1% vs 26.4%) and less use of R-CHOP or R-CHOP-like regimens (64.5% vs 35.2%) but more use of R-bendamustine (0% vs 12.1%) in Era 2 (P < .001). These changes were associated with improved event-free survival (EFS; 5-year EFS, 34.3% vs 50.0%; P = .010) and overall survival (OS; 5-year OS, 68.8% vs 81.6%; P = .017) in Era 2. In patients older than age 65 years, there was less use of R-CHOP or R-CHOP-like therapy (39.0% vs 14.3%) and nonstandard systemic therapy (36.6% vs 13.0%) but more use of R-bendamustine (0% vs 49.4%). These changes were associated with a trend for improved EFS (5-year EFS, 25.4% vs 37.5%; P = .051) in Era 2. The shift from R-CHOP or R-CHOP-like regimens to R-bendamustine was associated with improved EFS (5-year EFS, 25.0% vs 44.6%; P = .008) in Era 2. Results from this prospective cohort study provide critical real-world evidence for improved outcomes with evolving frontline patterns of care in patients with MCL.

Introduction

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is an uncommon subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) that is characterized by t(11;14)(q13;q32) translocation and cyclin D1 overexpression.1-3 The clinical presentation of MCL is heterogeneous, ranging from indolent to highly aggressive.3-5 The management strategy for MCL is diverse with no universal standard approach across institutions, although there is a consensus that autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) consolidation should be considered in young and fit patients after frontline immunochemotherapy.4,6,7

There have been several notable advances in the frontline treatment of newly diagnosed MCL over the last 2 decades. (1) Addition of the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab to chemotherapy resulted in improved outcomes.8-12 (2) High-dose chemotherapy followed by ASCT in first remission was proven to prolong progression-free survival (PFS) in the European MCL Network trial13 and has been adopted in the management of young and fit patients who are eligible for ASCT; evidence is emerging that it prolongs overall survival (OS).7 (3) Highly effective induction regimens containing high-dose cytarabine (HiDAC) have been developed. The rituximab plus hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (R-Hyper-CVAD) alternating with rituximab plus methotrexate and cytarabine (R-MA) regimen induces high response rate and long-term remission,14-16 but it is associated with high toxicity.17,18 The Nordic Lymphoma Group MCL2 trial established rituximab plus maximum-strength cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-maxi-CHOP) alternating with R-HiDAC as an efficacious induction regimen in patients who were eligible for ASCT.19-21 The European MCL Network trial confirmed the benefit of HiDAC in the randomized MCL Younger trial, which compared rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) alternating with rituximab plus dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin (R-DHAP) to R-CHOP alone as induction regimens in patients eligible for ASCT.22,23 (4) In patients who were ineligible for ASCT, rituximab maintenance therapy after responding to R-CHOP improved survival.24 In patients who were eligible for ASCT, rituximab maintenance after ASCT has demonstrated a survival benefit.25 (5) R-CHOP improved OS compared with rituximab plus fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients who were older or were ineligible for ASCT,24 but the German STiL NHL1 trial and the US BRIGHT trial have demonstrated that rituximab-bendamustine (R-bendamustine) results in superior PFS compared with R-CHOP.26-28 In addition, the SWOG S1106 study showed that R-bendamustine and R-Hyper-CVAD/R-MA had similar induction efficacy, suggesting that R-bendamustine may also be an acceptable induction regimen before ASCT.29,30 (6) Multiple studies have demonstrated that watchful waiting or deferred initial treatment is feasible and appropriate in a subset of patients who present with indolent disease.31-34

Despite the controlled clinical trial data that suggest these therapies have benefit, they require either extended treatment or use of specialized facilities. It is unclear how much physician education, patient acceptance, therapy-acquired resistance, or other factors may slow diffusion of these recommended management strategies. Nevertheless, as a result of the above advances, the practice pattern in managing newly diagnosed MCL has evolved accordingly. In this study, we sought to characterize the changes in frontline treatments and their association with outcomes in patients with newly diagnosed MCL by using a prospectively followed cohort.

Methods

Patients

This study was approved by the institutional review boards at Mayo Clinic and the University of Iowa and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients with newly diagnosed MCL were identified from the Molecular Epidemiology Resource (MER) of the University of Iowa/Mayo Clinic Lymphoma Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE). The MER is a prospective cohort study of lymphoma outcomes35 that includes consecutive patients with newly diagnosed lymphoma (within 9 months of diagnosis) since 2002. Patients enrolled on MER were managed according to the treating physician’s choice and were systematically observed every 6 months for the first 3 years and annually thereafter.

This study included all MER patients with newly diagnosed MCL from September 2002 through June 2015. Baseline clinical characteristics and treatment information were abstracted by using a standard protocol. Disease progression or relapse, re-treatment, and death were verified through medical record review. Frontline treatment was classified as standard immunochemotherapy, nonstandard systemic therapy, and nonsystemic therapy. Standard immunochemotherapy was further classified into 4 categories: R-Hyper-CVAD/R-MA, R-maxi-CHOP/R-HiDAC (Nordic regimen) or R-CHOP/R-DHAP, R-CHOP or R-CHOP-like, and R-bendamustine. Nonstandard systemic therapy included rituximab plus cladribine; rituximab plus fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone; rituximab only; or chemotherapy without rituximab. Nonsystemic treatment included surgery or radiotherapy alone or observation. The R-bendamustine regimen was adopted in 2010 at our institutions; therefore, September 2002 through December 2009 was defined as Era 1 and January 2010 through June 2015 was defined as Era 2.

Statistical analyses

Baseline clinical characteristics and treatment categories between the 2 eras were compared by using χ2 test and analysis of variance. EFS was defined as the time from diagnosis to disease progression or relapse, unplanned re-treatment after initial treatment, or death as a result of any cause. OS was defined as the time from diagnosis to death as a result of any cause. EFS and OS were analyzed by using the Kaplan-Meier method. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated via Cox regression models, with comparisons between eras adjusted for simplified MCL International Prognostic Index (sMIPI).36 Statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.0.3). A P value < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients

A total of 343 patients were included. Baseline clinical characteristics are provided in Table 1. In all, 265 patients (77.3%) were male. The median age at diagnosis was 64 years (range, 32-96 years), and 184 patients (53.6%) were age 65 years or younger. By sMIPI score, 79 (27.6%) had low-risk, 105 (36.7%) had intermediate-risk, and 102 (35.7%) had high-risk disease. There were 175 patients from Era 1 (2002-2009) and 168 from Era 2 (2010-2015). Sex, age, and sMIPI score were similar between the 2 groups (Table 1).

Treatment pattern

Because frontline treatment of MCL depends on the age and fitness of the patients and because age 65 years is considered the cutoff for ASCT, we evaluated the treatment pattern in Era 1 vs Era 2 in younger patients (age 65 years or younger) and older patients (older than age 65 years) separately. As shown in Table 2, for patients age 65 years or younger, compared with Era 1, there was less use of R-Hyper-CVAD/R-MA (16.1% vs 8.8%) but more use of Nordic orR-CHOP/R-DHAP regimens (1.1% vs 26.4%) in Era 2, and less use of R-CHOP/R-CHOP-like regimens (64.5% vs 35.2%) but more use of R-bendamustine (0% vs 12.1%). Use of nonstandard systemic treatment and nonsystemic treatment was similar between eras. The proportions of patients who underwent ASCT (45.2% vs 44.4%) and rituximab maintenance (5.4% vs 5.5%) were similar.

For patients older than age 65 years, use of the intensive R-Hyper-CVAD/R-MA (n = 2; Era 1 only) or Nordic or R-CHOP/R-DHAP regimens (n = 2; Era 2 only) was minimal. Compared with Era 1, there was less use of R-CHOP/R-CHOP-like therapy (39.0% vs 14.3%) and nonstandard systemic therapy (36.6% vs 13.0%) but more use of R-bendamustine (0% vs 49.4%). Use of nonsystemic treatment was similar between the eras. The proportions of patients who underwent ASCT (7.3% vs 6.5%) and rituximab maintenance (9.8% vs 14.3%) were similar.

Survival outcomes

The median follow-up was 13.0 years (95% CI, 12.2-15.9 years) for patients diagnosed in Era 1 (n = 175) and 7.1 years (95% CI, 6.9-8.0 years) for patients diagnosed in Era 2 (n = 168). For the entire cohort, EFS was improved in Era 2 compared with Era 1, with a median EFS of 2.5 years (95% CI, 2.0-3.1 years) vs 3.5 years (95% CI, 2.8-5.4 years) and a 5-year EFS of 30.2% (95% CI, 24.1%-37.8%) vs 43.9% (95% CI, 36.7%-52.4%) in Era 1 vs Era 2 (log-rank P = .002; sMIPI-adjusted HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.51-0.85; P = .002) (Figure 1A). There was also an improvement in OS in Era 2, with a 5-year OS of 59.2% (95% CI, 52.3%-67.0%) vs 68.4% (95% CI, 61.4%-75.7%) in Era 1 vs Era 2 (log-rank P = .007; sMIPI-adjusted HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.50-0.93; P = .016) (Figure 1B).

EFS and OS in 2 different eras. (A) EFS in Era 1 vs Era 2. (B) OS in Era 1 vs Era 2.

EFS and OS in 2 different eras. (A) EFS in Era 1 vs Era 2. (B) OS in Era 1 vs Era 2.

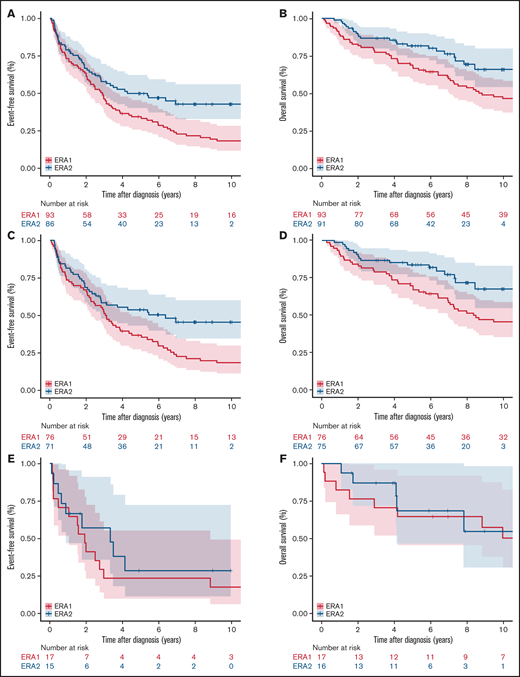

In patients age 65 years or younger, there was an improvement in both EFS (P = .007) and OS (P = .018) in Era 2 (Figure 2A-B; Table 3). The improvement was primarily driven by improved EFS (P = .007) and OS (P = .010) in patients who received standard immunochemotherapy (Figure 2C-D; Table 3). EFS and OS after induction therapy with R-CHOP or R-CHOP-like regimens were similar between the 2 eras (supplemental Figure 1), suggesting that there was no substantial change in supportive care over the study period. Patients who received nonstandard systemic therapy or nonsystemic therapy had similar EFS (P = .721) and OS (P = .447) in Era 1 and Era 2 (Figure 2E-F; Table 3).

EFS and OS in patients age 65 years or younger in 2 different eras. EFS of patients age 65 years or younger (A), who received standard immunochemotherapy (C), and who received nonstandard systemic therapy or nonsystemic therapy in Era 1 vs Era 2. OS of patients (E) age 65 or younger (B), who received standard immunochemotherapy (D), and who received nonstandard systemic therapy or nonsystemic therapy in Era 1 vs Era 2 (F).

EFS and OS in patients age 65 years or younger in 2 different eras. EFS of patients age 65 years or younger (A), who received standard immunochemotherapy (C), and who received nonstandard systemic therapy or nonsystemic therapy in Era 1 vs Era 2. OS of patients (E) age 65 or younger (B), who received standard immunochemotherapy (D), and who received nonstandard systemic therapy or nonsystemic therapy in Era 1 vs Era 2 (F).

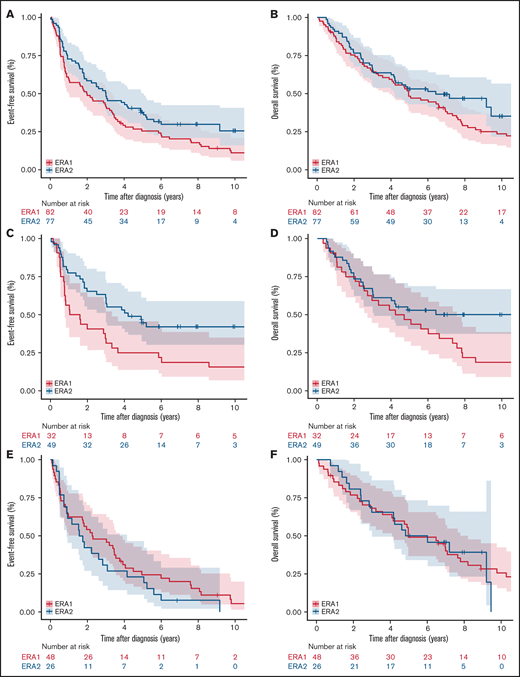

In patients older than age 65 years, there was a trend for improved EFS in Era 2 (P = .086) but no statistically significant difference in OS (P = .259) (Figure 3A-B; Table 3). The shift from R-CHOP/R-CHOP-like regimens to R-bendamustine was associated with an improved EFS (P = .002) and OS (P = .033) in Era 2 (Figure 3C-D; Table 3). Patients who received nonstandard systemic therapy or nonsystemic therapy had similar EFS (P = .091) and OS (P = .501) in Era 1 and Era 2 (Figure 3E-F).

EFS and OS in patients older than age 65 years in the 2 different eras. EFS of patients older than age 65 years (A), (C) who received R-CHOP/R-CHOP-like or R-bendamustine (C), and who received nonstandard systemic therapy or nonsystemic therapy in Era 1 vs Era 2 (E). OS of patients older than age 65 years (B), who received R-CHOP/R-CHOP-like or R-bendamustine (D), and who received nonstandard systemic therapy or nonsystemic therapy in Era 1 vs Era 2 (F).

EFS and OS in patients older than age 65 years in the 2 different eras. EFS of patients older than age 65 years (A), (C) who received R-CHOP/R-CHOP-like or R-bendamustine (C), and who received nonstandard systemic therapy or nonsystemic therapy in Era 1 vs Era 2 (E). OS of patients older than age 65 years (B), who received R-CHOP/R-CHOP-like or R-bendamustine (D), and who received nonstandard systemic therapy or nonsystemic therapy in Era 1 vs Era 2 (F).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first prospective cohort study of MCL frontline pattern of care in the rituximab era. Our data suggest heterogeneous but clearly changing management approaches that were likely influenced by landmark MCL trials and clinical studies. We did observe improved treatment outcomes with evolving frontline immunochemotherapy, which provides important real-world evidence that supports the use of HiDAC-containing induction regimens in patients who were eligible for ASCT and R-bendamustine in patients who were not eligible for ASCT. The change in practice pattern and the associated outcome improvement from Era 1 to Era 2 highlight the importance of conducting clinical trials to constantly improve treatments for MCL and of adopting better treatments in clinical practice.

Several previous studies examined the outcomes of MCL over time using registry data. Data from the Kiel Lymphoma Study Group (1975-1986) and the German Low-Grade Lymphoma Study Group (1996-2004) were primarily from the pre-rituximab era.37 SEER‐18 registry data demonstrated an improved OS from 2000-2006 to 2007-2013, but treatment data were not available.38 Similarly, data from the Swedish Lymphoma Registry showed an improved OS in 2006 to 2010 compared with data from 2000 to 2005, but treatment data for patients enrolled in 2007 or after was limited.39 A subsequent Nordic study using Swedish and Danish registry data demonstrated the benefit of rituximab and ASCT; although frontline treatment regimens were available, survival comparisons for patients from 2000 to 2005 vs those from 2006 to 2011 were not performed.40 Data from the United Kingdom Haematological Malignancy Research Network also demonstrated an improved OS from 2004-2011 to 2012-2015, although the treatment did not seem to be as intensive (50% of the patients were treated with fludarabine-, cyclophosphamide-, and/or chlorambucil-based regimens; rituximab for <40%, HiDAC for <20%, and ASCT for <10%).41 In contrast to the above, our study was based on a prospectively followed cohort with complete frontline treatment information, which allowed us to examine the changes in treatment patterns over time and to correlate the changes in treatment with clinical outcomes in both younger and older patients, which is more informative in analyzing and guiding clinical practice.

Several observations on the practice pattern in our study are worth noting. (1) In younger patients (age 65 years or younger), only ∼45% underwent ASCT. Understanding the reasons for not proceeding to ASCT is important in this age group. Detailed studies of comorbidities, response to induction, treatment-associated toxicities, and other factors will help define patient, disease, and treatment factors that can potentially be improved to increase the rate of ASCT, which is known to improve PFS and potentially OS.7,13 (2) In younger patients, there was increased use of the Nordic and R-CHOP/R-DHAP regimens in Era 2, but 35% of the patients still received an R-CHOP/R-CHOP-like regimen. Understanding the reasons behind the different induction choices is important so that the use of HiDAC-containing induction in patients eligible for ASCT can be maximized to improve treatment outcomes.22,23 (3) Rituximab maintenance was used at a relatively low rate, <10% in younger and <15% in older patients. In patients who were ineligible for ASCT, the role of rituximab maintenance is proven after R-CHOP24 but is controversial after R-bendamustine.42,43 The LYMA study demonstrated that rituximab maintenance improved OS after ASCT,25 but this study was published in 2017. The role of rituximab maintenance in the real-world setting warrants further studies. (4) Encouragingly, the shift from R-CHOP and R-CHOP-like regimens to R-bendamustine between Era 1 and Era 2 was associated with an improved EFS in older patients (older than age 65 years) receiving these regimens, consistent with the StiL NHL1 and BRIGHT trials.26-28

The strengths of this study include the prospective cohort study design, availability of detailed frontline treatment information and sMIPI data, long follow-up, analysis stratified by age group, and the correlation of practice change with treatment outcome. The weaknesses mainly relate to the observational study design in which treatment choice and follow-up management is at the discretion of the treating clinician. In addition, the study lacked racial diversity and included nearly all White patients, so results may not generalize to other racial/ethnic groups. We also lacked detailed analysis on treatment after disease progression. The availability of the immunomodulatory drug lenalidomide,44-46 Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors (BTKi’s)47-52 and the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax53-56 in recent years may have contributed to improved OS over time. For example, the first BTKi, ibrutinib, was approved in 2013, and patients diagnosed in Era 2 were more likely to have had access to BTKi’s at disease relapse. Better treatment options after relapse may have contributed to the improvement in outcomes in Era 2. Future studies that examine patterns of care in relapsed and refractory MCL and the association with outcomes are planned at our centers.

Our study showcases the importance of validating clinical trial outcomes in routine practice with real-world evidence. In a heterogeneous disease with diverse and emerging treatment options, learning from real-world evidence can guide institutional practices that will in turn benefit the patients. As novel agents such as lenalidomide,57,58 BTKi’s (in SHINE, ACE-LY-308, Window-1, TRIANGLE, and ECOG-ACRIN EA4181 studies),2,59 and venetoclax (in Window-2, PrECOG 0405, and OAsIs studies)60 move to the frontline setting, continuing studies of MCL frontline patterns of care will remain important and provide future guidance on clinical practice.

In summary, advances in frontline treatment of MCL were seen in both younger (less R-Hyper-CVAD/R-MA and R-CHOP/R-CHOP-like induction, more Nordic and R-CHOP/R-DHAP regimens) and older patients (less R-CHOP/R-CHOP-like and more R-bendamustine regimens). The changes in induction regimens were associated with improved EFS and OS in younger patients, and a shift from R-CHOP/R-CHOP-like regimens to R-bendamustine was associated with improved EFS in older patients. Results from this prospectively followed cohort provide critical real-world evidence for improved outcomes with evolving patterns of care in patients with MCL.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (P50 CA97274, U01 CA195568).

Authorship

Contribution: A.C., Y.W., J.R.C., and G.S.N. conceived and designed the study; A.C., Y.W., M.C.L., M.J.M., and C.A. collected and analyzed the data; A.C. and Y.W. wrote the manuscript; and A.C., Y.W., M.C.L, M.J.M., B.K.L., U.F., A.L.F., S.I.S., T.M.H., J.P., D.J.I., T.E.W., S.M.A, C.A., S.L.S., J.B.C., P.M., J.R.C., and G.S.N. interpreted the data and edited and provided final approval for the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: Y.W. received research funding (to the institution) from Incyte, InnoCare, LOXO Oncology, Novartis, and Genentech and served on advisory boards (remuneration to institution) for Eli Lilly, TG Therapeutics, LOXO Oncology, and Incyte. M.J.M. received research funding from MorphoSys, Genentech, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Nanostring and served on advisory boards for Pfizer, MorphoSys, and Kite Pharma. U.F. served on an advisory board for Kite Pharma. T.M.H. served on data monitoring committees for Seattle Genetics, Tessa Therapeutics, LOXO Oncology, and Eli Lilly (no personal remuneration for any of these). J.R.C. received research funding (to Mayo Clinic, unrelated to this study) from Genentech, NanoString, and Bristol Myers Squibb, and served on a steering committee for Bristol Myers Squibb (CONNECT Lymphoma Disease Registry; no personal remuneration). The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Yucai Wang, Division of Hematology, Mayo Clinic, 200 1st St SW, Rochester, MN 55905; e- mail: wang.yucai@mayo.edu; and Grzegorz S. Nowakowski, Division of Hematology, Mayo Clinic, 200 1st St SW, Rochester, MN 55905; email: nowakowski.grzegorz@mayo.edu.

References

Author notes

A.C. and Y.W. contributed equally to this study.

Requests for data sharing may be submitted to Yucai Wang (wang.yucai@mayo.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.