Key Points

We demonstrate risk factors for HCoV LRTI in allogeneic HCT recipients and significance of virologic documentation by BAL on mortality.

Hyperglycemia associated with steroid use appears to be a strong predictor of HCoV disease progression.

Abstract

Data are limited regarding risk factors for lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) caused by seasonal human coronaviruses (HCoVs) and the significance of virologic documentation by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) on outcomes in hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) recipients. We retrospectively analyzed patients undergoing allogeneic HCT (4/2008-9/2018) with HCoV (OC43/NL63/HKU1/229E) detected by polymerase chain reaction during conditioning or post-HCT. Risk factors for all manifestations of LRTI and progression to LRTI among those presenting with HCoV upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) were analyzed by logistic regression and Cox proportional hazard models, respectively. Mortality rates following HCoV LRTI were compared according to virologic documentation by BAL. A total of 297 patients (61 children and 236 adults) developed HCoV infection as follows: 254 had URTI alone, 18 presented with LRTI, and 25 progressed from URTI to LRTI (median, 16 days; range, 2-62 days). Multivariable logistic regression analyses showed that male sex, higher immunodeficiency scoring index, albumin <3 g/dL, glucose >150 mg/dL, and presence of respiratory copathogens were associated with occurrence of LRTI. Hyperglycemia with steroid use was associated with progression to LRTI (P < .01) in Cox models. LRTI with HCoV detected in BAL was associated with higher mortality than LRTI without documented detection in BAL (P < .01). In conclusion, we identified factors associated with HCoV LRTI, some of which are less commonly appreciated to be risk factors for LRTI with other respiratory viruses in HCT recipients. The association of hyperglycemia with LRTI might provide an intervention opportunity to reduce the risk of LRTI.

Introduction

Novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is currently circulating worldwide, causing significant morbidity and mortality.1 Seasonal human coronaviruses (HCoVs) are already known to be ubiquitous and recognized as respiratory pathogens in humans, typically causing mild respiratory illness in immunocompetent individuals.2 Limited data suggest that detection of HCoVs in lower respiratory tract specimens is associated with high rates of mortality in hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) recipients.3 However, risk factors for progression to lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) among patients who presented with HCoV upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) and the significance of HCoV detection in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), indicating lower respiratory tract involvement, are rarely systematically evaluated in this high-risk population.4,5 Understanding these features of HCoVs is crucial when evaluating the significance of SARS-CoV-2 in transplant recipients.6 The objective of this study was to identify risk factors for HCoV LRTI in allogeneic HCT recipients and investigate whether outcomes differ among patients with LRTI according to virologic documentation of lower respiratory tract involvement by BAL.

Methods

Study design

We reviewed allogeneic HCT recipients whose first HCoV infection was documented during conditioning or after transplantation through June 2019 to identify risk factors for LRTI.7 The transplant recipients were identified from 2 cohorts at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (Fred Hutch). The first cohort included patients who underwent transplantation between July 2009 and September 2018 and had respiratory tract samples collected and tested for clinical purposes. The second cohort was a subset of patients from a prospective surveillance study of allogeneic HCT recipients undergoing transplantation from April 2008 to February 2010 in which standardized respiratory symptom surveys and multiplex respiratory polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests were performed regardless of symptoms at several timepoints: pre-HCT, weekly during the first 100 days post-HCT, and at least every 3 months through 1 year post-HCT.8 Clinical samples were also collected at clinicians’ discretion if respiratory symptoms were noted. For the current study, we included subjects with respiratory symptoms at the time of first detection of HCoV. For evaluation of outcome following LRTI according to virologic documentation by BAL, we included all transplant recipients with first HCoV LRTI. Demographic and clinical data were extracted from Fred Hutch’s database and medical chart review. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Fred Hutch and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Laboratory testing

Upper (nasopharyngeal and nasal wash) and lower (BAL) respiratory tract samples were tested by multiplex semiquantitative, reverse-transcription PCR for 12 respiratory viruses. This laboratory developed assay detects all 4 species of seasonal HCoVs (OC43/NL63/HKU1/229E); however, strain-specific PCR is not routinely performed.8-10 All PCR reactions were performed according to College of American Pathologists standards. Some pediatric transplant recipients underwent a commercial multiplex qualitative respiratory PCR assay (FilmArray; BioFire Diagnostics, Salt Lake City, UT) for an initial diagnosis, after which HCoV was evaluated by the laboratory developed test for quantification.11 Institutional standard investigation of BAL specimens includes broad diagnostic tests, including multiplex PCR for respiratory viruses; conventional cultures for bacteria, fungi, mycobacteria, and viruses; shell vial culture for cytomegalovirus; immunofluorescent antibody staining for Pneumocystis jirovecii; Aspergillus galactomannan enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; cytopathologic examination; and PCR for Legionella and fungus.3

Definitions

URTI was defined as HCoV detection in an upper respiratory tract sample with respiratory symptoms. As previously described, proven or probable LRTI was defined as having virus detected from a lower respiratory tract sample (BAL) with or without new pulmonary infiltrates by chest radiography, respectively.12 Possible LRTI was defined as having virus detected from an upper respiratory tract sample with new pulmonary infiltrates (but without confirmation of virus in a lower respiratory tract sample). Patients who met criteria for LRTI within 1 day of URTI were considered to have LRTI at presentation and were not included in the LRTI progression analysis.7 A HCoV illness event was considered to be a new event if ≥12 weeks elapsed between 2 positive samples or if there were ≥2 negative HCoV samples between 2 HCoV-positive samples.13 A respiratory copathogen was defined as a pathogen detected in a concurrent respiratory sample. A copathogen in blood was defined as a pathogen or antigen (bacteria, fungi, virus, or Aspergillus galactomannan enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) detected in a blood sample obtained within 2 days of diagnosis of HCoV infection.12 Nearest values of blood cell counts and serum glucose within 2 weeks before HCoV diagnosis were recorded. Similarly, lowest serum albumin value and highest daily steroid dose within 2 weeks prior to HCoV diagnosis were collected. Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) grades represent maximum grades. GVHD severity at the time of HCoV infection was assessed by the highest daily corticosteroid dose administered within 2 weeks prior to the diagnosis of HCoV infection. Glucose values were categorized as most recent glucose value >150 mg/dL, ≤150 mg/dL, or missing.14 The variable of most recent glucose value >150 mg/dL was further subcategorized according to whether the high glucose values were observed repeatedly or not within 2 weeks before HCoV diagnosis.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics were compared among disease categories using χ2 or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Student t test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables (as appropriate). The probability of progression to HCoV LRTI among patients who presented with HCoV URTI was estimated by cumulative incidence curves, treating death as a competing risk. Gray’s test was used to compare cumulative incidence probabilities between categories. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for progression to HCoV LRTI within 90 days of HCoV URTI. Logistic regression models were used to evaluate cross-sectional association between each risk factor and occurrence of LRTI among all patients with first HCoV infection (including patients who presented with HCoV LRTI). Overall survival rates following HCoV LRTI were compared according to virologic documentation by BAL (log-rank test).

All covariates with P values < 0.1 in the univariable analyses were candidates for inclusion in the multivariable models. Immunodeficiency scoring index (ISI) was originally developed to predict progression to respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) LRTI as a discreate variable in transplant recipients.15 ISI was treated as a continuous variable in multivariable models given a limited number of outcome events, and steroid use and blood cell counts were not included in the same models with ISI, as these are components of ISI.15 For multivariable Cox regression models, serum glucose levels were correlated with steroid use, and it was not feasible to calculate each effect given the sample size. Therefore, we created a composite variable for glucose and steroid use to evaluate the joint effects. For multivariable logistic regression models, we also performed a sensitivity analysis where to evaluate whether including steroid use and cell counts instead of ISI provided a better-fitting model. Two-sided P values < .05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Patient characteristics

Among 2553 patients undergoing allogeneic HCT during the study period, 297 patients (61 children and 236 adults) had documented symptomatic HCoV infection (supplemental Figure 1). Characteristics of each HCoV infection group are shown in Table 1. The majority of first HCoV infections occurred after day 30 following HCT (254/297, 86%) with a median of 174 days and a range of −9 to 3489 days relative to the date of HCT. Among patients with first HCoV infection, 254 had URTI alone, 18 presented with LRTI, and 25 progressed from URTI to LRTI (progression rate of 9% after a median of 16 days; range, 2-62 days). Among 254 patients who had URTI only during first HCoV infection episodes, 10 patients developed LRTI during the subsequent HCoV infection episodes. The days from the first episode and subsequent episode of those 10 patients were as follows: median of 549 days, range of 38 days to 795 days. A total of 53 patients (2.1%) were found to have HCoV LRTI (16 proven/probable LRTI and 37 possible LRTI) in this entire cohort.

Risk factors for occurrence of LRTI

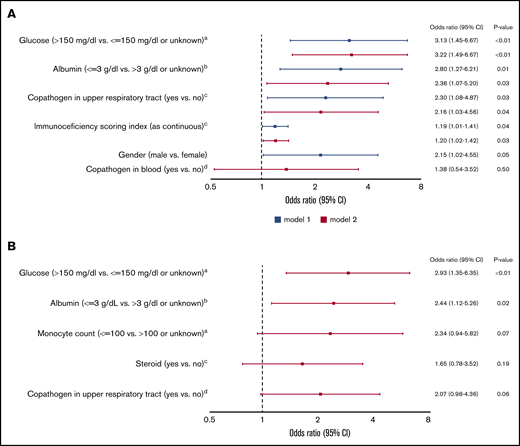

In univariable logistic regression models, all variables shown in supplemental Table 1 were evaluated to identify factors associated with occurrence of LRTI. In multivariable models including ISI as a continuous variable, male sex, higher ISI, albumin level <3 g/dL, glucose value >150 mg/dL, and presence of respiratory copathogens at HCoV diagnosis were associated with LRTI (Figure 1A). Although steroid use and monocytopenia were associated with LRTI in univariable models, these were not included in above adjusted models, since cytopenia and steroid use are components of ISI (as described in “Methods”). Therefore, we also performed additional multivariable analyses to evaluate the independent effects of steroid use and monocytopenia (instead of ISI); only hypoalbuminemia (<3 g/dL) and hyperglycemia (>150 mg/dL) remained significant (Figure 1B).

Multivariable logistic regression models for occurrence of HCoV LRTI among 297 patients with first HCoV infection (43 outcome events). (A) Models including ISI. aNearest value within 2 weeks before HCoV diagnosis. bLowest albumin level in the 2 weeks before HCoV diagnosis. cAt HCoV diagnosis. dA pathogen or antigen detected in a blood within 2 days of HCoV diagnosis. (B) Models including steroid use and monocyte count instead of ISI. aNearest value within 2 weeks before HCoV diagnosis. bLowest albumin level in the 2 weeks before HCoV diagnosis. cHighest daily steroid dose in the 2 weeks before HCoV diagnosis. dAt HCoV diagnosis. CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Multivariable logistic regression models for occurrence of HCoV LRTI among 297 patients with first HCoV infection (43 outcome events). (A) Models including ISI. aNearest value within 2 weeks before HCoV diagnosis. bLowest albumin level in the 2 weeks before HCoV diagnosis. cAt HCoV diagnosis. dA pathogen or antigen detected in a blood within 2 days of HCoV diagnosis. (B) Models including steroid use and monocyte count instead of ISI. aNearest value within 2 weeks before HCoV diagnosis. bLowest albumin level in the 2 weeks before HCoV diagnosis. cHighest daily steroid dose in the 2 weeks before HCoV diagnosis. dAt HCoV diagnosis. CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Risk factors for progression to LRTI

Univariable analyses for progression to HCoV LRTI revealed risk-factor candidates, including transplant number, ISI, steroid dose, and glucose value >150 mg/dL (supplemental Table 1). Given the high collinearity between steroid use and hyperglycemia and the limited number of events, a composite variable for glucose and steroid was included into multivariable models to evaluate the effect of both factors. Models consistently demonstrated significant association of hyperglycemia with steroid use with progression to LRTI (Table 2). Figure 2 shows the cumulative incidence curve of progression to LRTI stratified by the categories of the composite variable. The probability of progression to LRTI in patients with hyperglycemia and steroid use at the time of HCoV URTI reached 100% at day 48 (P < .01 with Gray’s test). Furthermore, we examined the relationship between highest daily steroid dose (mg/kg) and glucose value (mg/dL) among 130 patients who had systemic steroid use in the 2 weeks prior to HCoV URTI (Figure 3), and the correlation was weak (R2 = 0.13). Of note, higher viral load (lower Ct value) was not associated with increased risk of occurrence of or progression to LRTI (supplemental Table 1).

Cumulative incidence of progression to HCoV LRTI by day 90 among 279 patients presenting with first HCoV URTI.P value is < .01 with Gray’s tests. Among 129 patients with no steroid, none of 13 patients with glucose values >150 mg/dL progressed to LRTI and 7 of 116 (6%) patients with glucose values ≤150 mg/dL or unknown progressed to LRTI. With the limited sample size, we combined those as a group of no steroid use.

Cumulative incidence of progression to HCoV LRTI by day 90 among 279 patients presenting with first HCoV URTI.P value is < .01 with Gray’s tests. Among 129 patients with no steroid, none of 13 patients with glucose values >150 mg/dL progressed to LRTI and 7 of 116 (6%) patients with glucose values ≤150 mg/dL or unknown progressed to LRTI. With the limited sample size, we combined those as a group of no steroid use.

Relationship between glucose value and steroid dose. Scatterplots depict the relationship between highest daily steroid dose (mg/kg) and glucose value (mg/dL) among 130 patients who received systemic steroids in 2 weeks prior to human coronavirus URTI (R2 = 0.13). Glucose was the nearest within 2 weeks before URTI.

Relationship between glucose value and steroid dose. Scatterplots depict the relationship between highest daily steroid dose (mg/kg) and glucose value (mg/dL) among 130 patients who received systemic steroids in 2 weeks prior to human coronavirus URTI (R2 = 0.13). Glucose was the nearest within 2 weeks before URTI.

Outcomes following proven/probable vs possible LRTI

The probabilities of overall survival at 90 days following proven/probable and possible LRTI are shown in Figure 4A (log-rank test, P < .01). The outcomes following proven/probable LRTI were worse than possible LRTI, and the trend appears to be consistent after stratifying groups according to oxygen use at the time of LRTI diagnosis (Figure 4B; log-rank test, P = .03). Among 16 patients with proven/probable LRTI, 8 patients were found to have respiratory copathogens such as RSV, human metapneumovirus, rhinovirus, Staphylococcus aureus, Elizabethkingia, and Aspergillus fumigatus, and 3 of 8 patients with copathogens died within 90 days of LRTI diagnosis. Similarly, 4 of 8 patients who had no respiratory copathogen died within 90 days.

Overall survival by day 90 according to HCoV LRTI categories among patients with first HCoV LRTI (N = 53). (A) Kaplan-Meier estimate of overall survival by LRTI categories (proven/probable vs possible LRTI; P < .01). (B) Kaplan-Meier estimate of overall survival according to LRTI categories (proven/probable vs possible LRTI) with oxygen requirement at LRTI diagnosis (P = .03).

Overall survival by day 90 according to HCoV LRTI categories among patients with first HCoV LRTI (N = 53). (A) Kaplan-Meier estimate of overall survival by LRTI categories (proven/probable vs possible LRTI; P < .01). (B) Kaplan-Meier estimate of overall survival according to LRTI categories (proven/probable vs possible LRTI) with oxygen requirement at LRTI diagnosis (P = .03).

Discussion

This study demonstrated that hypoalbuminemia, male sex, high serum glucose, presence of respiratory copathogens, and higher ISI were associated with the occurrence of HCoV LRTI. Hyperglycemia frequently occurred in the context of steroid use and appeared to be unrelated to steroid dose. Steroids with hyperglycemia did increase the risk of progression to LRTI among patients who presented with HCoV URTI, but steroids without hyperglycemia did not. Mortality rates following proven/probable HCoV LRTI were higher than possible LRTI.

A novel finding is that hyperglycemia is an important risk factor for occurrence of LRTI based on the multivariable logistic regression models. Similarly, Cox regression models using a composite variable of glucose value and steroid use consistently demonstrated a significant association between hyperglycemia with steroid use and progression from URTI to LRTI (Table 2). Prior studies in HCT recipients suggested that steroid use and active GVHD status were associated with occurrence of HCoV LRTI; however, steroid dose and serum glucose level were not evaluated.4,5 Systemic corticosteroid use, standard therapy for active GVHD, can induce hyperglycemia, and higher doses of steroid use are a known risk factor for progression to LRTI with other respiratory viruses in transplant recipients; therefore, we hypothesized that the effect of hyperglycemia primarily reflects the impact of steroid dose.7,13,16 However, there was only a weak correlation between steroid dose and glucose value (Figure 3). Thus, it appears that glucose values were independent of steroid dose and hyperglycemia in the context of steroid use is a risk factor for progression to LRTI.

Whether hyperglycemia as a risk factor for respiratory viral disease progression in immunocompromised hosts is poorly understood. Jung et al reported that among cancer patients who received steroids as part of induction therapy, steroid-induced hyperglycemia was associated with serious infection (bacterial and fungal infection).17 A recent study indicated that hyperglycemia (each 10-mg/dL increase in glucose level) was associated with increased risk of viremia/viruria in transplant recipients.18 Hyperglycemia has been recognized as a prognostic factor for poor outcomes in patients with SARS-CoV-2 regardless of the previous history of diabetes, and routine screening of hyperglycemia has been proposed for hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2.19-21 Several clinical studies suggested that patients with diabetes are at risk for severe H1N1 influenza infections.22 In an animal model, diabetic mice had increased susceptibility to severe infections with influenza virus, and the enhanced susceptibility was reversed with insulin.23 Hyperglycemia affects innate immunity in various ways, and the exact mechanisms remain to be elucidated.24,25 Recent data highlighted the role of increased glucose metabolism in influenza A virus–induced cytokine storm; influenza A virus promotes O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine transferase binding to interferon regulatory factor 5, leading to subsequent downstream inflammatory cytokine production.26 The role of hyperglycemia with or without steroid use as well as glycemic control on progression to LRTI due to HCoV or other respiratory viruses should be further evaluated.

The role of HCoV infection in immunocompromised hosts has not been well understood until recently, and particularly, data concerning risk factors for LRTI in transplant recipients are still limited.3-5,27-29 Our institutions have been consistently utilizing multiplex PCR for clinically relevant respiratory viruses for over a decade, allowing us to identify risk factors for HCoV LRTI in the current PCR era. Multivariable logistic regression analyses revealed additional risk factors, relatively less commonly appreciated as risk factors for LRTI due to other respiratory viruses in HCT recipients.7,13,15,16,30,31 Whether these factors are also relevant to LRTI due to SARS-CoV-2 in this high risk population requires further study, although some studies have already shown male sex as a risk factor for poor outcomes related to SARS-CoV-2 in cancer patients.32,33 The presence of respiratory copathogens has not been well recognized as a risk factor for progression to LRTI due to HCoV or other respiratory viruses perhaps other than parainfluenza virus in HCT recipients.4,5,7,13,29,31,34-36 It is possible that some previous studies either did not evaluate this as a potential risk factor, or did not have the diagnostic capability to assess for this in the pre-PCR era. Overall, progression rates in patients with HCoV URTI are lower than those with other respiratory viruses, which may indicate that having more virulent respiratory viral copathogens (eg, RSV, human metapneumovirus) increases the risk of progression to LRTI.13,37,38 Revisiting the role of respiratory copathogens in LRTI outcomes is worth considering in this current molecular diagnostic era.

Hypoalbuminemia was associated with occurrence of HCoV LRTI, but not with progression from URTI to LRTI. Eichenberger et al also reported hypoalbuminemia was associated with occurrence of LRTI in logistic regression models in HCT recipients.5 Among our 43 patients with HCoV LRTI, 18 presented with HCoV LRTI, who were included into logistic regression models, but not into Cox regression models. This may partly explain the difference in association with outcomes and implies that hypoalbuminemia is a marker of severe illness due to LRTI rather than a risk factor for progression from URTI to LRTI. A similar observation was found for ISI, although the caveat is that our sample size only allowed us to use this scoring index as a continuous variable in multivariable models.15 Assessments of risk factors for progression from URTI to LRTI are particularly relevant for the design of early-intervention strategies to reduce the risk of disease progression. Further studies are needed to assess whether ISI as a discrete variable can predict progression to HCoV LRTI.

Important negative findings in the present study include that obesity and higher viral loads were not associated with increased risk of either occurrence of HCoV LRTI or progression to LRTI. Both factors have been identified as risk factors for progressive disease in SARS-CoV-2 infection.39-43 However, some studies in immunocompromised hosts did not demonstrate the association between obesity and poor outcomes with SARS-CoV-2 infection.6,32 Similarly, not all studies have been able to demonstrate a correlation of viral loads with outcome after SARS-CoV-2 infection,44,45 and previous studies for other respiratory viruses in transplant recipients also did not demonstrate that higher viral loads are a risk factor for progression to LRTI.7,13,46

Cytopenia in ≥1 cell line has been well recognized as a risk factor for LRTI due to majority of other clinically relevant respiratory viruses in immunocompromised hosts.7,13,31,34,35 A recent paper has shown an association with HCoV LRTI outcome, but another has not.4,5 In our analysis, cytopenias were significant when analyzed in univariable models and as part of the ISI but did not reach statistical significance in adjusted models when analyzed individually (Figure 1; supplemental Table 1). Our study also differs from other studies in terms of overall rates of LRTI.4,5,27 This could be due to a differential distribution of risk factors for LRTI as well as less complete virologic documentation of mild URTI.

The current study showed that patients with proven/probable HCoV LRTI had worse overall survival compared with those with possible LRTI. The mortality rates in patients with proven/probable HCoV LRTI were high regardless of the presence of respiratory copathogens, especially with oxygen requirement at the time of LRTI diagnosis. Overall, these results are consistent with previous studies of other respiratory viruses, suggesting the significance of virologic documentation of lower respiratory tract involvement by BAL.12,47,48 Additional studies are needed to assess whether proven/probable LRTI is an independent risk factor for mortality or whether the BAL procedure is just a marker of severe illness (eg, sicker patients are more likely to undergo BAL procedures).

This study has several limitations. Although this cohort represents one of the largest number of allogeneic HCT recipients infected with HCoV, the sample size was nonetheless too small to perform full multivariable Cox models to assess the independent effect of hyperglycemia on progression from URTI to LRTI from steroid dose. HbA1c may be a better indicator to predict LRTI outcome than glucose level given that HbA1c has less variability within subjects. No significant association between HbA1c and LRTI outcome was found in univariable analyses (supplemental Table 1); however, a substantial proportion of subjects did not have an HbA1c level within 3 months before HCoV diagnosis, and further studies are needed to address this question. Proven/probable LRTI may be more relevant outcomes given different mortality rates seen between patients with proven/probable LRTI and those with possible LRTI. However, our sample size did not allow us to analyze for these outcomes separately. At our institutions, HCT recipients with lower respiratory tract symptoms and radiographic abnormalities typically undergo BAL procedures. Nevertheless, the ultimate decision was deferred to the attending physicians, and some proven LRTI might have been classified as possible LRTI. Since many institutions do not routinely perform BAL for virologic confirmation, our results for any LRTI outcomes, from a practical point of view, can be broadly applicable. Many studies of respiratory viruses in HCT recipients have used definitions of LRTI that include possible cases.15,49-52 Lastly, given the nature of retrospective studies, we cannot rule out the possibility of other confounders.

In conclusion, our risk factor analyses for HCoV LRTI outcomes demonstrated unique features for HCoV compared with other respiratory viruses previously evaluated in HCT recipients. Whether these observations are also applicable to SARS-CoV-2 in HCT recipients requires further study. Assessing the independent effect of hyperglycemia from the use of steroids on progression from URTI to LRTI due to HCoV or other respiratory viruses is warranted, as this might provide an opportunity for interventions, including glycemic control, to reduce the risk of LRTI for this vulnerable population.

Original data are available by request to the corresponding author (cogimi@fredhutch.org).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ashley Akramoff and Anthony Mallory for data collection and Chris Davis for database services.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, grant K23AI139385 (C.O.), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants R01HL081595 and K24HL093294 (M.B.), and National Cancer Institute grants CA18029 (W.M.L. [clinical database]) and grant CA15704 (H.X.); the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center Vaccine and Infectious Disease Division (biorepository); and a Seattle Children’s Research Institute Clinical Research Scholars Program Award (C.O.).

Authorship

Contribution: C.O. designed this study, assisted in analysis, interpreted results, and wrote the manuscript; H.X. and W.M.L. performed the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript; A.W., M.U.O., and K.K.M. provided clinical input, interpreted results, and reviewed the manuscript; K.R.J. provided technical oversight for laboratory and reviewed the manuscript; and J.A.E. and M.B. provided oversight, designed the study, interpreted results, and reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.W. reports research support from Ansun Biopharma, Allovir, VB Tech, and Amazon and is an advisory board member for Kyorin Pharmaceutical. J.A.E. reports research support from AstraZeneca, Merck, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, and Novavax; is an advisory board member and consultant for Sanofi Pasteur; and is a consultant for Meissa Vaccines. M.B. reports research support from Amazon, GSK, Regeneron, Ridgeback, Janssen, Gilead, and VirBio; consultant fees from Allovir, Janssen, Gilead, Moderna, and VirBio; and is an advisory board member for Evrys Bio (option to purchase shares). Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Chikara Ogimi, Pediatric Infectious Diseases Division, Seattle Children’s Hospital, 4800 Sand Point Way NE, MA.7.226, Seattle, WA 98105; e-mail: cogimi@fredhutch.org.

References

Author notes

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.