Key Points

Inflammasome activation plays a key role in venous thrombosis.

Tissue factor released from pyroptotic macrophages contributes to venous thrombosis.

Crosstalk between coagulation and innate immunity contributes to the progression of many diseases, including infection and cardiovascular disease. Venous thromboembolism (VTE), including pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis (DVT), is among the most common causes of cardiovascular death. Here, we show that inflammasome activation and subsequent pyroptosis play an important role in the development of venous thrombosis. Using a flow restriction–induced mouse venous thrombosis model in the inferior vena cava (IVC), we show that deficiency of caspase-1, but not caspase-11, protected against flow restriction–induced thrombosis. Interleukin-1β expression increased in the IVC following ligation, indicating that inflammasome is activated during injury. Deficiency of gasdermin D (GSDMD), an essential mediator of pyroptosis, protected against restriction-induced venous thrombosis. After induction of venous thrombosis, fibrin was deposited in the veins of wild-type mice, as detected using immunoblotting with a monoclonal antibody that specifically recognizes mouse fibrin, but not in the caspase-1–deficient or GSDMD-deficient mice. Depletion of macrophages by gadolinium chloride or deficiency of tissue factor also protected against venous thrombosis. Our data reveal that tissue factor released from pyroptotic monocytes and macrophages following inflammasome activation triggers thrombosis.

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a leading cause of cardiovascular death,1 affecting 300000 to 600000 individuals (1 to 2 per 1000) each year in the United States.2-4 The initiation of venous thrombus formation is a multifactorial process that involves a complex cascade of events. Endothelial activation and recruitment of immune cells, including monocytes and neutrophil, are observed in deep vein thrombosis (DVT).5 It appears that crosstalk between monocytes, neutrophils, and platelets is responsible for the initiation and amplification of DVT.5 Both platelets and endothelium play an important role in venous thrombosis.5 Besides directly participating in thrombosis, platelets contribute to DVT through several other mechanisms, including supporting coagulation, forming platelet-leukocyte aggregates, therebysupporting leukocyte recruitment, promoting neutrophil extracellular traps formation, etc.6

Venous thrombi are rich in fibrin and red blood cells.7 Hypercoagulable state is thought to be one of the major risk factors for the formation of venous thrombi.8 Accordingly, tissue factor (TF) derived from myeloid leukocytes is a central initiator of DVT.5 It is known that blood flow restriction or stasis, and subsequent local hypoxia, is a major factor driving DVT.9-12 Hypoxia can induce expression of the inflammasome NLRP3 and caspase-1.13 Importantly, expression of caspase-1 is elevated in patients with VTE,13 suggesting a potential role of the inflammasome in DVT. We recently showed that TF released from monocytes and macrophages following inflammasome activation triggers coagulation during sepsis.14 In this study, we used caspase-1–deficient mice to demonstrate that inflammasome activation plays an important role in the development of DVT. Development of DVT was also inhibited by deficiency of gasdermin D (GSDMD) and TF, and monocyte depletion. Our findings identify a novel mechanism of DVT, which is through TF released from pyroptotic monocytes and macrophages following inflammasome activation.

Methods

Mice

Wild-type (WT) C57BL/6J, Casp1−/−, Casp11−/−, Gsdmd−/−, B6.Cg-Tg(UBC-cre/ERT2)1Ejb/J Cre transgenic mice, TF floxed mice, and WT littermates were housed in the University of Kentucky Animal Care Facility,14 following institutional and National Institutes of Health guidelines after approval by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male mice at 8 to 12 weeks were used in all experiments. Inducible TF-deficient mice were generated by breeding the B6.Cg-Tg(UBC-cre/ERT2)1Ejb/J Cre transgenic mice with TF floxed mice. CreERT2-recombinase expression for removal of TF was induced by intraperitoneal injections of tamoxifen (Sigma) at 100 mg/kg per day for 5 consecutive days at 4 to 5 weeks of age, and subsequent experiments were carried out at 5 weeks postinduction. WT littermates were also treated with tamoxifen.

Induction of flow restriction model in mice

The model of DVT was induced using a stenosis model in inferior vena cava (IVC). In brief, mice were anesthetized and placed in a supine position. The abdomen was opened along the midline, and the intestines were exteriorized gently. Warmed saline was applied to intestine regularly during the surgery to prevent drying out. The IVC was gently separated from aorta and then was ligated under the left renal vein with a 7-0 polypropylene suture over a spacer (30-gauge needle [0.3 mm × 25 mm]). After that, the spacer was removed to create a 90% stenosis without endothelial disruption. All visible side branches were ligated completely. Finally, the intestines were returned to the peritoneal cavity; the peritoneum was closed with 6-0 suture, and the skin was closed with staples. After 48 hours, thrombi were harvested for measurement.

Fibrin extraction for immunoblotting analysis

Thrombi were homogenized in 10 volumes (mg:µL) of the tissue protein extraction reagent (T-PER; Thermo, Cat. no. 78510) containing protease cocktail inhibitor (Sigma, Cat. no. P8340) and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. After centrifugation at 10000g for 10 minutes, the supernatant was collected for β-actin detection. The pellet was homogenized in 3 M urea and vortexed for 2 hours at 37°C. After centrifugation at 14000g for 15 minutes, the pellet was resuspended in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) buffer and vortexed at 65°C for 30 minutes for fibrin detection.

Western blot

For detection of fibrin and interleukin (IL)-1β by western blot, tissue homogenates were analyzed using SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on 4% to ∼15% gradient gels, immunoblotted using antifibrin (59D8) antibody15 at 1 µg/mL or anti–IL-1β polyclonal antibody (1 μg/mL, GeneTex, GTX74034). For detection of TF by western blot, brain tissue homogenates were analyzed using SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on 4% to 15% gradient gels, immunoblotted using anti-TF antibody at 0.5 µg/mL (Abcam, ab189483).

Monocyte and macrophage depletion

Statistical analysis

Nonparametric data (weight and length of thrombus) were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test (2-sided). Parametric results (monocytes depletion and neutrophil counts) were analyzed using 2-tailed Student t test. DVT incidence was analyzed by χ2 analysis. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted on biological replicates in GraphPad Prism 7.

Results and discussion

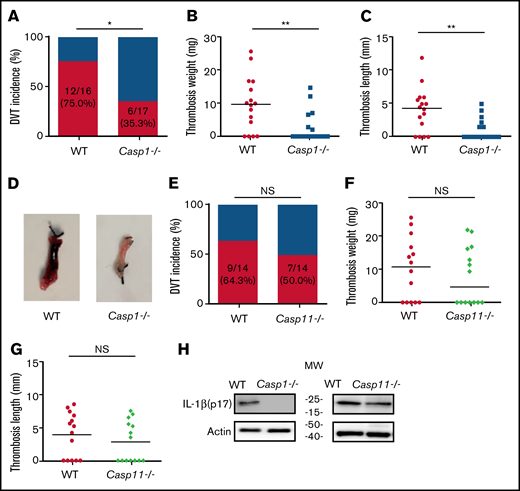

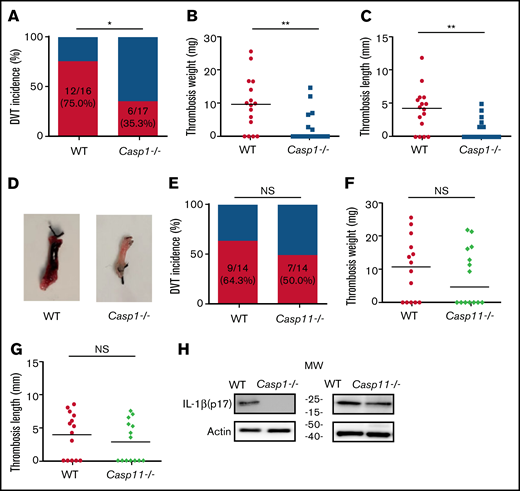

Deficiency of caspase-1 protects against venous thrombosis following IVC ligation

To investigate the role of inflammasome activation in venous thrombosis development, we compared formation of venous thrombosis between WT and caspase-1–deficient mice18 utilizing an IVC stenosis model to induce DVT. Forty-eight hours after IVC ligation, 75.0% of the WT mice developed venous thrombosis (Figure 1A). In contrast, only 35.3% of the caspase-1–deficient mice developed venous thrombosis. The weight and length of thrombi were also reduced in the caspase-1–deficient mice (Figure 1B-D). Although activation of the canonical pathway of inflammasome leads to caspase-1 cleavage and activation, activation of the noncanonical pathway of inflammasome results in cleavage and activation of caspase-11.19-21 To determine whether the noncanonical inflammasome pathway is involved in venous thrombosis, we examined venous thrombosis in caspase-11–deficient mice. Although the incidence of thrombosis in the caspase-11–deficient mice is slightly lower than in WT mice (50.0% for caspase-11–deficient mice vs 64.3% for WT), the difference did not reach statistical significance (Figure 1E). Accordingly, the weight and length of thrombi were not affected by caspase-11 deficiency (Figure 1F-G). Thus, the noncanonical inflammasome pathway does not play a major role in venous thrombosis. In agreement with the contribution of caspase-1 to venous thrombosis, IL-1β was detected in the thrombi of WT mice and caspase-11–deficient mice, but not in the caspase-1–deficient mice (Figure 1H).

Inflammasome activation triggers venous thrombosis following IVC ligation. (A-D) WT (n = 16) and caspase-1–deficient mice (n = 17) were subjected to IVC stenosis. Thrombus prevalence (A), thrombus weight (B), and thrombus length (C) were measured at 48 hours after the surgery. Representative images of thrombi are shown in panel D. Lines in dot plots represent medians. ⋆P < .05; ⋆⋆P < .01. The χ2 method was used in panel A and Mann-Whitney U test was used in panels B and C. (E-G) WT mice (n = 14) and caspase-11–deficient mice (n = 14) were subjected to IVC stenosis. Thrombus prevalence (E), thrombus weight (F), and thrombus length (G) were measured at 48 hours after the surgery. (H) Western blot analysis of clots from WT, caspase-1– and caspase-11–deficient mice. IL-1β in the lysates of clots was measured by immunoblot with an anti–IL-1β polyclonal antibody. NS, not significant .

Inflammasome activation triggers venous thrombosis following IVC ligation. (A-D) WT (n = 16) and caspase-1–deficient mice (n = 17) were subjected to IVC stenosis. Thrombus prevalence (A), thrombus weight (B), and thrombus length (C) were measured at 48 hours after the surgery. Representative images of thrombi are shown in panel D. Lines in dot plots represent medians. ⋆P < .05; ⋆⋆P < .01. The χ2 method was used in panel A and Mann-Whitney U test was used in panels B and C. (E-G) WT mice (n = 14) and caspase-11–deficient mice (n = 14) were subjected to IVC stenosis. Thrombus prevalence (E), thrombus weight (F), and thrombus length (G) were measured at 48 hours after the surgery. (H) Western blot analysis of clots from WT, caspase-1– and caspase-11–deficient mice. IL-1β in the lysates of clots was measured by immunoblot with an anti–IL-1β polyclonal antibody. NS, not significant .

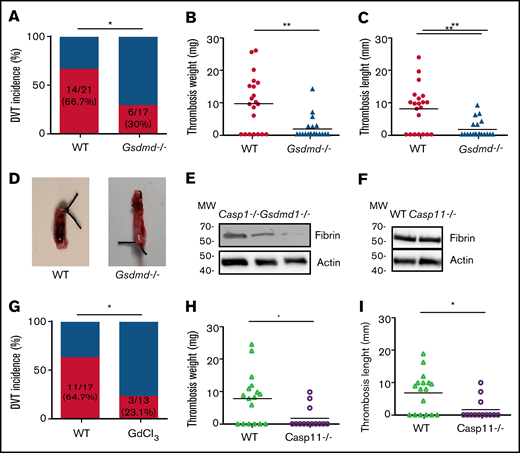

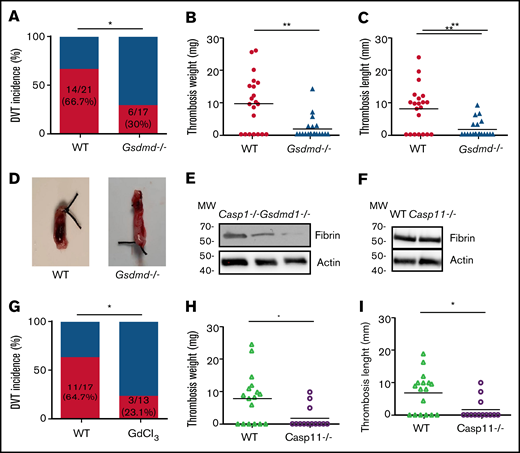

Inflammasome activation enhances venous thrombus formation through pyroptosis

Inflammasome activation leads to release of inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and -18, as well as a GSDMD-mediated programmed necrotic cell death, pyroptosis.18,22,23 To determine whether pyroptosis contributes to the development of DVT, we examined flow restriction–induced venous thrombosis in the GSDMD-deficient mice.24 Of GSDMD-deficient mice, 30.0% produced thrombi, whereas 66.7% of the WT littermates developed thrombi (Figure 2A). Both thrombus weight and length in the IVC following flow restriction were reduced in the GSDMD-deficient mice (Figure 2B-D). These data demonstrate that pyroptosis is required for flow restriction–induced venous thrombosis. Platelets play a key role in arterial thrombosis. To determine whether inflammasome activation may also contribute to arterial thrombosis, we observed the effect of inflammasome and pyroptosis on platelet aggregation and FeCl3-induced carotid artery thrombosis. Our data indicate that FeCl3-induced carotid artery thrombosis was not affected by deficiency of caspase-1 or GSDMD (supplemental Figure 1A). Accordingly, platelet aggregation in response to thrombin or collagen was not affected by deficiency of caspase-1 or GSDMD (supplemental Figure 1B-C).

Pyroptosis of monocytes and macrophages is responsible for DVT. (A-D) WT (n = 21) and GSDMD-deficient mice (n = 20) were subjected to IVC stenosis. Thrombus prevalence (A), thrombus weight (B), and thrombus length (C) were measured at 48 hours after the surgery. Representative images of thrombi are shown in panel D. Lines represent the medians. ⋆P < .05; ⋆⋆P < .01. The χ2 method was used in panel A, and Mann-Whitney U test was used in panels B and C. (E) Western blot analysis of clots from WT, caspase-1, and GSDMD-deficient mice. Fibrin in the same amount of tissue lysates was detected by immunoblot with an antifibrin monoclonal antibody (59D8). (F) Fibrin in the same amount of proteins of the tissue lysates from WT and caspase-11–deficient mice was detected by immunoblot with an antifibrin monoclonal antibody (59D8). (G-I) Effect of monocyte depletion on venous thrombosis. C57BL/6J mice administered with GdCl3 (n = 13) or buffer (n = 17) were subjected to IVC stenosis. Thrombus prevalence (G), thrombus weight (H), and thrombus length (I) were measured at 48 hours after the surgery. Lines represent the medians. ⋆P < .05. The χ2 method was used in panel G, and Mann-Whitney U test was used in panels H and I. Ctrl, control.

Pyroptosis of monocytes and macrophages is responsible for DVT. (A-D) WT (n = 21) and GSDMD-deficient mice (n = 20) were subjected to IVC stenosis. Thrombus prevalence (A), thrombus weight (B), and thrombus length (C) were measured at 48 hours after the surgery. Representative images of thrombi are shown in panel D. Lines represent the medians. ⋆P < .05; ⋆⋆P < .01. The χ2 method was used in panel A, and Mann-Whitney U test was used in panels B and C. (E) Western blot analysis of clots from WT, caspase-1, and GSDMD-deficient mice. Fibrin in the same amount of tissue lysates was detected by immunoblot with an antifibrin monoclonal antibody (59D8). (F) Fibrin in the same amount of proteins of the tissue lysates from WT and caspase-11–deficient mice was detected by immunoblot with an antifibrin monoclonal antibody (59D8). (G-I) Effect of monocyte depletion on venous thrombosis. C57BL/6J mice administered with GdCl3 (n = 13) or buffer (n = 17) were subjected to IVC stenosis. Thrombus prevalence (G), thrombus weight (H), and thrombus length (I) were measured at 48 hours after the surgery. Lines represent the medians. ⋆P < .05. The χ2 method was used in panel G, and Mann-Whitney U test was used in panels H and I. Ctrl, control.

Inflammasome activation increases TF release in venous thrombosis

A venous thrombus is rich in fibrin. By using western blot with a monoclonal antibody specifically recognizing mouse fibrin,15 we detected fibrin formation in the venous thrombus milieu of WT and caspase-1 or GSDMD-deficient mice following IVC ligation.25 Our data indicate that normalized fibrin concentration was less in thrombus tissues from the caspase-1– or GSDMD-deficient mice than thrombus tissues from WT mice (Figure 2E). In contrast, deficiency of caspase-11 had no impact on fibrin concentration in the thrombus tissues (Figure 2F). Previous studies have shown that TF derived from myeloid leukocytes plays an important role in the development of DVT.5 We hypothesized that TF released from pyroptotic monocytes and macrophages may trigger venous thrombosis. Indeed, flow restriction–induced venous thrombosis was markedly inhibited in inducible whole-body TF-deficient mice (supplemental Figure 2). Flow restriction–induced venous thrombosis was also diminished in mice in which monocytes and macrophages were predepleted by administration of GdCl3 (supplemental Figure 3; Figure 2G-I). Depletion of monocytes and macrophages by GdCl3 did not affect neutrophil counts in peripheral blood and the function of neutrophil to form neutrophil extracellular traps (supplemental Figure 4). These data demonstrate that TF from monocytes and macrophages plays a key role in venous thrombosis.

Our results demonstrate that TF released from pyroptotic macrophages plays an important role in venous thrombosis and thus uncovers the mechanisms linking inflammation and thrombosis. Considering the risks of the anticoagulant treatment of venous thrombosis, strategies specifically targeting inflammasome activation and pyroptosis may lead to the development of novel therapeutics against venous thrombosis.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge fibrin antibodies provided by Hartmut Weiler at Medical College of Wisconsin and Rodney M. Camire at the University of Pennsylvania.

This work was supported by grants K99HL145117 (C.W., who is a K99 awardee); National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) grant R01 HL124266 (A.A.-L.); National Science Foundation grant CHE-1709381 (Y.W.), NIH/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grants R56 AI137020 (Y.W.), R21 AI142063 (Y.W.), NIH/NHLBI grant R01 HL142640 (Y.W.), NIH/National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) grants R01 GM132443 (Y.W.); and NIH/NHLBI R01 HL146744 (Z.L.), R01 HL142640 (Z.L.), and NIH/NIGMS R01 GM132443 (Z.L.).

Authorship

Contribution: Y.Z., M.T., and Z.L. designed and performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript, assisted by G.Z., J.C., C.W., A.A.-L., S.S.S., N.M., Y.W., who contributed to manuscript preparation; T.S. and N.M. provided mice and discussed the experiments; and all authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

ORCID profiles: C.W., 0000-0001-7725-7881; A.A.-L., 0000-0002-8178-7102.

Correspondence: Zhenyu Li, University of Kentucky, 741 South Limestone St, BBSRB, Room 351, Lexington, KY 40536; e-mail: zhenyuli08@uky.edu.

References

Author notes

For access to materials, datasets, or protocols, please contact the corresponding author at zhenyuli08@uky.edu.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.