Key Points

The use of terminal complement blockade is compatible with virus-specific T-cell (VST) expansion and clinical effectiveness.

VST and complement-blocking agent concurrent therapy may be safely used in patients with thrombotic microangiopathy and viral infections.

Introduction

The immunological response to viral infection is complicated and requires an intricate balance between the innate and adaptive arms of the immune system.1 Patients who are immunosuppressed are at increased risk of morbidity and mortality from ubiquitous viruses, and may not respond to traditional antiviral therapy.2,3 Virus-specific T cells (VSTs) generated in a rapid manufacturing process using pools of overlapping antigenic viral peptides (pepmix) have been used to successfully treat recurrent and/or refractory viral infections in this population.4-6 The complement system is essential for viral immunity and complement proteins are known to direct and modify the cellular immune response to viral infections.7,8 Thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA), a severe complication in susceptible individuals that can lead to organ failure or death, can be often triggered by viruses that can lead to complement-mediated systemic endothelial injury.9-14 The use of complement blockers has been reported to mitigate TMA,15 but the impact of complement blockade on the efficacy of VST activity has not yet been described. We assessed the impact of terminal complement blocker eculizumab on VST activity in patients receiving concurrent therapies for TMA and viral infection.

Methods

Patients with cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), adenovirus and/or BK viremia, invasive viral disease, or symptomatic hemorrhagic cystitis/nephritis received quadrivalent donor-derived and/or third-party donor VSTs as previously described5 after study approval by the institutional review board. Clinical response to VSTs was determined 4 weeks after each infusion or at time of death. Complete response (CR) was defined as resolution of viremia by blood polymerase chain reaction quantification and/or resolution of associated symptoms. Partial response (PR) was defined as >50% reduction in viremia and associated symptoms.5,6 Interferon-γ enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISpot) was performed by pulsing patient peripheral blood mononuclear cells with the pertinent viral pepmix.5,6,16

High-risk complement-mediated TMA was diagnosed using published criteria.15 Eculizumab off-label therapy was administered using pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic-guided drug dosing with detailed drug level and complement blockade monitoring as previously reported.15,17 We evaluated response to VST infusions that were carried out under full blood complement blockade.

Results and discussion

One hundred seventy-seven patients have received a total of 351 infusions of VSTs during the duration of the study (2016-2020). Eighteen patients had TMA and received eculizumab at some point during VST therapy. Five patients were excluded from analysis. Two patients completed eculizumab therapy and had normalization of blood complement activity prior to infusion of VST. Three patients died, 6 to 10 days after VST infusion, of intracerebral hemorrhage, alveolar hemorrhage, and disseminated candidemia, respectively, which is prior to the expected timeframe of clinical efficacy.

Thirteen patients included in the analysis received a total of 34 evaluable VST infusions during complement blockade. Demographics and disease characteristics are shown in Table 1. Ten patients received VSTs derived from their respective hematopoietic stem cell donors, 1 patient received both donor-derived VSTs and partially HLA-matched VSTs derived from a third-party donor, and 2 patients received third-party VSTs. The median number of VST infusions was 2 (range, 1-6). Indications for repeated infusion in a single patient included having persistent or new viral disease, receiving partially HLA-matched third-party VSTs (which are likely to be rejected after 4-6 weeks), and/or experiencing delayed recovery of endogenous T cells after hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT). Twelve patients were allogeneic HSCT recipients whereas 1 patient was treated for severe disseminated adenoviral infection with secondary complement-mediated TMA.

The median time between starting eculizumab and the first VST infusion under complement blockade was −20 days (range, −68 to +10 days). All but 1 patient had consistently therapeutic eculizumab trough levels (>100 μg/mL) and adequate complement suppression (CH50 complement activity <10% of normal value) during VST infusion and for 4 weeks after each VST infusion. One patient had intermittently subtherapeutic eculizumab drug levels although sC5b-9 normalized with therapy suggesting adequate complement control.

Full outcome data are presented in Table 1. The median viral load at first infusion was 128 049 copies per milliliter for adenovirus, 28 168 copies per milliliter for BK virus, 2481 IU/mL for CMV, and 21 627 IU/mL for EBV. Any response (CR and PR) was seen in 24 of 34 infusions (70.6%) with 17 of 24 (70.8%) of those responses being CR. The median absolute lymphocyte count at first infusion was 140 cells per microliter (range, 300-1640) and the median post-HSCT day at first infusion was day +63 (range, 29-224). Responses occurred in 5 of 7 infusions for CMV (71.4%; 4 CR, 1 PR), 5 of 6 infusions for EBV (83.3%; 2 CR, 3 PR), 5 of 7 infusions for adenovirus (71.4%; 5 CR, 0 PR), and 9 of 14 infusions for BK virus (64.2%; 6 CR, 3 PR). Three patients died: 1 from disseminated adenovirus, 1 with multiorgan failure but improved BK viremia, and 1 with multiorgan failure with complete resolution of adenoviremia. The 5 nonresponses for BK virus were from 4 patients: 3 of them responded to subsequent VST infusions administered during complement blockade (2 received different partially matched third-party products and 1 received a second infusion of their donor-derived product). The fourth patient has only received 1 infusion to date and had a CR for adenovirus, showing an ability to still have an antiviral response while under complement blockade. Similar findings were seen with EBV and adenovirus, where, for each virus, 1 nonresponder had a clinical response after a second infusion of the donor-derived product. Together, 12 of 13 patients (92.3%) ultimately had any clinical response to VSTs given while under complement blockade with a CR to at least 1 virus in 10 of 13 patients (76.9%). These response rates are comparable with both previously published data from other institutions using multivalent VSTs, and with our own institutional experience of VST infusion without complement blockade.4-6,18 There were no documented VST infusion-associated reactions and no de novo acute graft-versus-host disease.

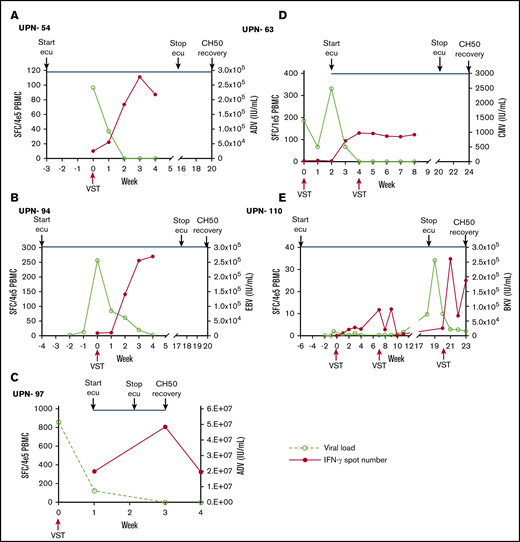

We performed an interferon-γ ELISpot in 5 patients to investigate the number of antiviral T lymphocytes present in the blood of patients following VST infusion during complement blockade. All 5 patients had a CR or PR and showed evidence of T-cell expansion, suggesting that complement inhibition does not interfere with the activity of infused allogeneic T cells in a meaningful way (Figure 1).

Expansion of antiviral T cells correlated with viral load under the influence of complement blockade. (A-E) Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from patients at the time of VST infusion and weekly for the first 4 weeks afterward. Interferon-γ ELISpot was performed on samples after stimulation with pools of overlapping viral peptides (pepmix) from the treated virus. Interferon-γ (IFN-γ)–secreting T cells at each time point were plotted with the corresponding viral polymerase chain reaction quantification at that time. The timing of complement blockade is indicated by the start of eculizumab (ecu), discontinuation of ecu, and the time of CH50 normalization. CH50 normalization is a marker that complement blockade is no longer occurring in blood. Each panel represents ELISpot assay performed on samples isolated from distinct individual patients. ADV, adenovirus; BKV, BK virus; SFC, spot-forming cell.

Expansion of antiviral T cells correlated with viral load under the influence of complement blockade. (A-E) Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from patients at the time of VST infusion and weekly for the first 4 weeks afterward. Interferon-γ ELISpot was performed on samples after stimulation with pools of overlapping viral peptides (pepmix) from the treated virus. Interferon-γ (IFN-γ)–secreting T cells at each time point were plotted with the corresponding viral polymerase chain reaction quantification at that time. The timing of complement blockade is indicated by the start of eculizumab (ecu), discontinuation of ecu, and the time of CH50 normalization. CH50 normalization is a marker that complement blockade is no longer occurring in blood. Each panel represents ELISpot assay performed on samples isolated from distinct individual patients. ADV, adenovirus; BKV, BK virus; SFC, spot-forming cell.

Based on these data, we believe the use of terminal complement inhibition is compatible with clinical response to VSTs in patients receiving both eculizumab and VSTs. Although commencing VST therapy after initiation of eculizumab raises the question of whether complement blockade promotes viremia, we previously have shown that there is no increased incidence of viral infection in pediatric HSCT recipients treated with eculizumab.19 Terminal complement blockade in our patients did not impact VST response, as demonstrated through monitoring of viral load and interferon-γ production. Novel evidence shows that the intracellularly active complement system, the complosome, plays a key role in the regulation of cell metabolic pathways that underlie normal human T-cell responses. In such cases, a specific intracellular targeting of complement proteins C5a or C5aR1 would be required to inhibit VSTs.7,20

These data are important for planning future studies. That certain viruses can trigger complement-mediated TMA leading to multiorgan injury and death is well described, and such cases may require concomitant therapy with complement inhibition and VSTs to control both viral illness and complement overactivation.10,21 Animal models demonstrate that complement system overactivation is implicated in acute respiratory distress syndrome22 (one of the immune-driven pathologies observed in severe cases of coronavirus such as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus) and suggests that inhibition of complement signaling might be an effective treatment option.23 A subgroup of patients with severe COVID-19 is shown to have a hyperinflammatory syndrome with multiorgan failure, for which treatment with immune-modulating therapy, including complement-blocking agents, may be of benefit.24,25 In the search for a novel and effective therapy option for COVID-19, there are ongoing efforts to generate T cells directed against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Such VSTs may need to be used in conjunction with complement blockers in severe cases, so it is imperative for us to know that complement-modulating therapy does not impact T-cell activation and effectiveness. In summary, our data suggest that the use of terminal complement blockade is compatible with VST expansion and clinical effectiveness. Complement-blocking agent therapy may be initiated or continued in patients receiving VST therapy if they have evidence of life-threatening complement overactivation.

Please contact jeremy.rubinstein@cchmc.org for queries regarding data.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) Bone Marrow Tissue Repository and the Cell Processing Core laboratory for ongoing technical assistance.

This work was supported by divisional funds from the Division of Bone Marrow Transplantation and Immune Deficiency. Part of the research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number R01HD093773 (S.J. and S.M.D.).

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Authorship

Contribution: J.D.R., S.J., S.M.D., and A.S.N. collected and analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; X.Z. performed the ELISpot assays and provided contributions in data analysis and presentation; C.M.B. and P.J.H. created and shared the technology for generation of VSTs; C.L., T.L., and J.A.C. oversaw the preparation and quality control of infused cellular products; M.S.G. performed patient monitoring, collaborated in trial design, and contributed to clinical outcome analysis; and all authors edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.J. and S.M.D. have a US provisional patent application pending, and have research support from Alexion. S.J. has received travel support from Omeros. C.M.B. has equity ownership in Mana Therapeutics, serves on the scientific advisory board and has filed patents that cover generation of virus-specific T cells, has stock ownership in Neximmune and Torque, and serves on the board of directors of Cabaletta Bio. P.J.H. is a cofounder of, and is on the board of directors of, Mana Therapeutics and has intellectual property related to virus-specific T cells. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jeremy D. Rubinstein, Division of Bone Marrow Transplantation and Immune Deficiency, Cancer and Blood Disease Institute, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, 3333 Burnet Ave, MLC 7015, Cincinnati, OH 45229; e-mail: jeremy.rubinstein@cchmc.org.