Key Points

aGVHD and VOD/SOS syndrome were associated with a higher incidence of TA-TMA, performance status, and HLA mismatch.

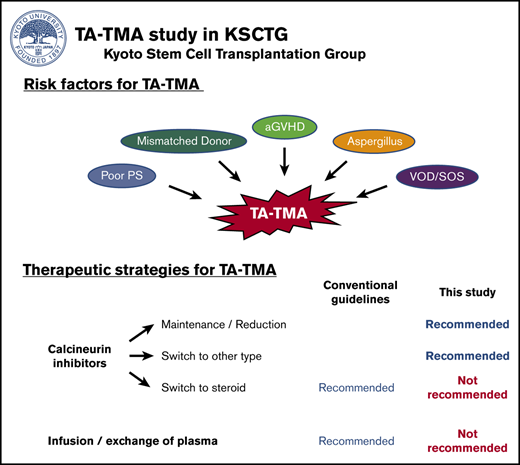

CNI maintenance or reduction induced a better outcome, whereas replacement with steroids and plasma infusion/exchange were not recommended.

Abstract

Transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy (TA-TMA) is a fatal complication of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT). However, so far, no large cohort study determined the risk factors and the most effective therapeutic strategies for TA-TMA. Thus, the present study aimed to clarify these clinical aspects based on a large multicenter cohort. This retrospective cohort study was performed by the Kyoto Stem Cell Transplantation Group (KSCTG). A total of 2425 patients were enrolled from 14 institutions. All patients were aged ≥16 years, presented with hematological diseases, and received allo-HSCT after the year 2000. TA-TMA was observed in 121 patients (5.0%) on day 35 (median) and was clearly correlated with inferior overall survival (OS) (hazard ratio [HR], 4.93). Pre- and post-HSCT statistically significant risk factors identified by multivariate analyses included poorer performance status (HR, 1.69), HLA mismatch (HR, 2.17), acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD; grades 3-4) (HR, 4.02), Aspergillus infection (HR, 2.29), and veno-occlusive disease/sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (VOD/SOS; HR, 4.47). The response rate and OS significantly better with the continuation or careful reduction of calcineurin inhibitors (CNI) than the conventional treatment strategy of switching from CNI to corticosteroids (response rate, 64.7% vs 20.0%). In summary, we identified the risk factors and the most appropriate therapeutic strategies for TA-TMA. The described treatment strategy could improve the outcomes of patients with TA-TMA in the future.

Introduction

Transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy (TA-TMA), a fatal complication, which may develop after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT), is a microvascular occlusive disorder characterized by thrombocytopenia, systemic or intrarenal aggregation of platelets, mechanical injury to erythrocytes, and ischemic organ damage.1 Despite the recent progress in pre- and posttransplant supportive care, TA-TMA is still recognized as a devastating complication after allo-HSCT, exhibiting a mortality rate of up to 60% to 75%.1,2

A variety of studies have been performed to improve the nonfavorable outcomes of TA-TMA. Among these are (1) analyses of risk factors1,3 and (2) evaluations of therapeutic strategies.4 As for risk analyses, a wide range of factors have been proposed, such as acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD), infections, unrelated or HLA-mismatched donor grafts, and the use of a calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) or sirolimus.1,3 However, these analyses are often associated with epidemiological and statistical challenges, one of which is the use of nonstandardized diagnostic criteria for TA-TMA; diagnosis is usually based on the criteria stipulated by either Europe (European Bone Marrow Transplant International Working Group)5 or United States (Blood and Marrow Transplantation Clinical Trial Network)2 but sometimes clinically judged at an earlier stage before all these criteria are fulfilled.6,7 Therefore, most retrospective studies have been based on cases diagnosed by nonharmonized diagnostic criteria, then studies performed using uniform criteria for TA-TMA remain to be performed. Another challenge is represented by selection bias; various types of complications, such as aGVHD and veno-occlusive disease/sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (VOD/SOS), usually appear in the acute phase after allo-HSCT when TA-TMA is most often observed.8 Misjudgment of causality (whether aGVHD/VOD/SOS or other complications resulted in TA-TMA and can be risk factors for TA-TMA, or not) introduces selection bias in the risk analysis for TA-TMA.9

The evaluation of therapeutic strategies such as the newly introduced treatments based on recombinant human thrombomodulin (rhTM),10 defibrotide,11 and eculizumab12 is also important. However, previous studies focusing on newer treatments have been based on relatively small cohorts (N < 100), and their conclusions are unclear. Moreover, conventional treatment methods as stipulated by current guidelines,2 such as replacement of CNIs with corticosteroids, should be revisited and accurately reevaluated.

Therefore, we performed a large multicenter retrospective cohort study and identified incidence, risk factors, appropriate therapeutic strategies, and outcomes of TA-TMA by obtaining all necessary data from clinical records and evaluating these using a standardized protocol. The use of this methodology can overcome previous limitations and lead to new insight into TA-TMA management and total outcome improvement.

Patients and methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This retrospective cohort study performed by the Kyoto Stem Cell Transplantation Group (KSCTG) enrolled adult patients (age ≥16 years) with hematological diseases who received allo-HSCT between 1 January 2000 and 30 September 2016. Cases receiving double-unit cord blood transplantation (CBT) and unrelated peripheral blood stem cell transplantation (PBSCT) were excluded because these are not yet considered standard therapeutic options in Japan. Patients who were followed for less than 30 days or for whom data on donor source, mismatch in HLA, GVHD prophylaxis, date of last follow-up, and number of HSCT were lacking were also excluded. Patients for whom we met difficulties in terms of retrieving the original clinical records (mostly from a relatively large time interval between allo-HSCT and the time of patient inclusion) were also excluded. Our protocol complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional review board of each participating institution or the central review board in Kyoto University Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained individually at each institution.

TA-TMA diagnosis and therapeutic strategies

A set of diagnostic criteria for TA-TMA was established based on conventional criteria.2,5 In this retrospective study, we first listed the patients who were suspected with TA-TMA by attending physicians and then by reviewing their medical records we confirmed the diagnosis if the patients fulfilled 2 of the following diagnostic criteria with TA-TMA: (1) presence of erythrocyte fragmentation and schistocytes (2 counts or more per 1 high-power field) in a peripheral blood smear, (2) concurrently increased serum lactate dehydrogenase levels above institutional baseline, (3) de novo prolonged or progressive thrombocytopenia (platelet count <50 × 109/L or a 50% or greater decrease from previous counts) or anemia (decrease of hemoglobin concentration or increase in red blood cell transfusion requirement), (4) concurrent renal dysfunction (doubling of serum creatinine levels relative to baseline or 50% decrease in creatinine clearance from baseline) and/or neurological dysfunction without other causes, and (5) negative direct and indirect Coombs test results or a decrease in serum haptoglobin concentration.

Therapeutic strategies for TA-TMA, including administration of rhTM, infusion of fresh frozen plasma (FFP), plasma exchange, modulation of CNI, and corticosteroids (CS) were performed based on the decisions of the attending physicians. The modulation of CNI and CS were divided into 4 groups: (1) patients whose CNI were maintained or reduced without replacing and exchanging their CNI type (maintenance/reduction of CNI), (2) patients whose CNI was switched to the different type of CNI irrespective of modulation of CS (switch to other CNIs), (3) patients whose CNI was replaced with CS (switch to CS), and (4) patients whose CS were increased without replacing and exchanging their CNI type (increase of CS). All data regarding the types and the initiation date of the therapeutic strategies were recorded and collated.

Data collection and definition of each covariate

From the KSCTG database, we extracted data on basic pretransplant characteristics and posttransplant clinical courses. Data on TA-TMA were not included in the KSCTG database, and therefore, we reviewed medical records and extracted the data related to the diagnosis and therapeutic strategies for TA-TMA according to the predefined standardized diagnostic criteria listed previously. Patients were categorized into 2 groups with respect to age (<50 years of age vs ≥50 years of age), performance status (PS; 0-1 vs 2-4), hematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index (HCT-CI; 0-2 vs ≥3). Underlying diagnoses were divided into 8 groups: acute myelogenous leukemia/myelodysplastic syndrome (AML/MDS), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL), chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), multiple myeloma (MM), aplastic anemia (AA), and other hematological diseases (others). Patients were divided into high-risk and standard-risk groups according to disease risk. Standard-risk was defined as follows: (1) acute leukemia in first complete remission phase, (2) de novo refractory anemia and ringed sideroblasts, (3) malignant lymphoma/MM in complete or partial remission phase, or (4) all nonmalignant hematological diseases. All other patients were considered high-risk patients. As for conditioning regimens, myeloablative conditioning (MAC) and reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) were defined based on the previously published consensus criteria.13 The year of HSCT was categorized into 2 groups (2000-2009 vs 2010-2016) based on the median HSCT year of the entire cohort. HLA disparity in HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-DR antigens was determined at serology level for related bone marrow transplantation (BMT), related PBSCT, and CBT; a 6/6 match was categorized as an HLA-matched group, and the others as an HLA-mismatched group. For unrelated BMT, HLA disparity was identified at DNA-allelic level; an 8/8 match was categorized as an HLA-matched group, and the others as HLA-mismatched groups. Diagnosis and classification of aGVHD were performed on the basis of traditional criteria by the attending physicians at each center.14,15 Diagnosis of infectious diseases, including any bacterial, fungal (Candida spp and Aspergillus spp), and viral (cytomegalovirus [CMV], adenovirus, and BK virus) infections, was also performed by the attending physicians at the respective center. Standard infection prevention strategies were adopted in accordance with the guidelines of the Japanese Society for Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation and included the use of a protective environment, prophylactic administration of antibiotics (normally fluoroquinolone, fluconazole, and acyclovir), and intravenous immunoglobulin replacement for hypogammaglobulinemia.16 The diagnosis of VOD/SOS was performed based on the traditional criteria by the attending physicians at each center.17

Regarding response to TA-TMA treatment, the patients who had decrease of serum lactate dehydrogenase levels or fragment red blood cells were defined as response to therapy.

Statistical analyses

The cumulative incidence for TA-TMA was calculated using Gray’s test; death from any cause was considered a competing risk. Overall survival (OS) was evaluated in patients with or without TA-TMA using the Simon-Makuch method and compared using the Cox proportional hazard model, treating TA-TMA development as a time-dependent covariate. The cumulative incidence of nonrelapse mortality (NRM) was calculated using Gray’s method, considering relapse and death as competing risks. Correlations between each pre- or posttransplant factor and TA-TMA development were analyzed using the Fine-Gray proportional hazards model; post-HSCT events such as aGVHD and VOD/SOS were treated as time-dependent covariates in correlation with TA-TMA. We evaluated the effect of each TA-TMA treatment on clinical response using a logistic regression model and on OS using the Cox proportional hazards model. Values of P < .05 were considered statistically significant. Factors appearing as significant in the univariate analysis were subjected to the multivariate analyses. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA (version 16.0; Stata Corp, TX) and EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Patient characteristics

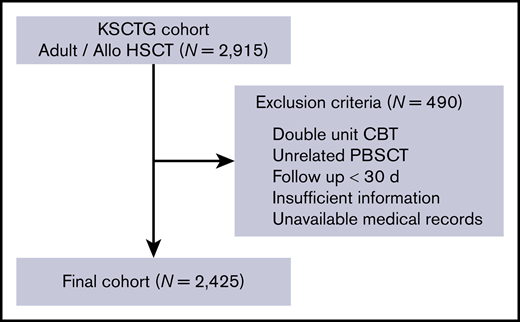

We enrolled 2425 patients who received allo-HSCT in a total of 17 centers from 2000 to 2016. The schematic workflow of inclusion and exclusion of our study patients is shown in Figure 1, and patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median age at HSCT was 50 years (range, 16-74 years), and 1387 (57.2%) of the patients were male. PS at HSCT was poor (2-4) in 359 (14.8%) patients, and HCT-CI score was high (≥3) in 213 patients (8.8%). Overall, 1234 patients were transplanted for AML/MDS, 381 for ALL, and 350 for NHL. As for disease risk, 1217 (50.2%) patients were classified as being at high risk. With regard to donor source, 471 patients (19.4%) received related BMT, 422 (17.4%) related PBSCT, 870 (35.9%) unrelated BMT, and 662 (27.3%) unrelated CBT. HLA mismatch was observed for 1458 (60.2%) patients, owing to the higher proportion of mismatched donor in CBT (91.4%) and unrelated BMT (68.6%). The number of HLA-mismatched patients in each donor source is shown in supplemental Table 1. The median follow-up period for survivors was 1499 days (range, 31-5943 days). Other pre-HSCT characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Schematic workflow of patient inclusion and exclusion. The KSCTG adult allogenic stem cell transplantation cohort consisted of 2915 patients from 17 centers. We excluded patients who fulfilled the mentioned exclusion criteria and finally enrolled 2425 patients in this study.

Schematic workflow of patient inclusion and exclusion. The KSCTG adult allogenic stem cell transplantation cohort consisted of 2915 patients from 17 centers. We excluded patients who fulfilled the mentioned exclusion criteria and finally enrolled 2425 patients in this study.

Incidence of TA-TMA and its impact on post-HSCT outcome

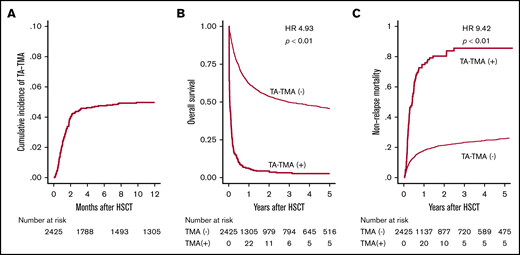

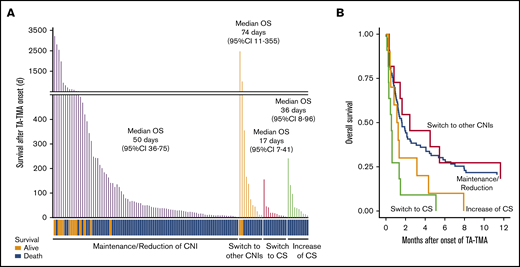

First, 134 patients who were suspected with TA-TMA by attending physicians were listed in this retrospective study, and among them 121 patients who met these criteria were diagnosed with TA-TMA (supplemental Figure 1). After HSCT, TA-TMA was diagnosed on a median of 35 days (range, 3-482 days), and the cumulative incidence of TA-TMA 12 months after HSCT was 5.0% (Figure 2A). Among these 121 patients, 46 and 43 patients fully met the conventional European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation International Working Group (EBMT IWG)18 and Blood and Marrow Transplantation Clinical Trial Network (BMT CTN) criteria,2 respectively (supplemental Figure 1). The 1-year OS of patients with and without TA-TMA was 6.0% and 62.1%, respectively (Figure 2B). The development of TA-TMA correlated with remarkably inferior OS (hazard ratio [HR], 4.93; 95% confidence interval [CI], 4.03-6.02; P < .01), when treating TA-TMA as a time-dependent covariate. Moreover, the 1-year NRM was significantly higher (72.7% vs 17.4%, P < .01) in patients with TA-TMA than in those without TA-TMA (Figure 2C).

Cumulative incidence of TA-TMA and its effect on survival after allo-HSCT. (A) Cumulative incidence of TA-TMA was calculated using Gray’s method. (B) OS is shown in the Simon-Makuch plot, with TA-TMA treated as a time-dependent variable. (C) The cumulative incidence of NRM for patients with or without TA-TMA.

Cumulative incidence of TA-TMA and its effect on survival after allo-HSCT. (A) Cumulative incidence of TA-TMA was calculated using Gray’s method. (B) OS is shown in the Simon-Makuch plot, with TA-TMA treated as a time-dependent variable. (C) The cumulative incidence of NRM for patients with or without TA-TMA.

Pre- and post-HSCT risk factors for the development of TA-TMA

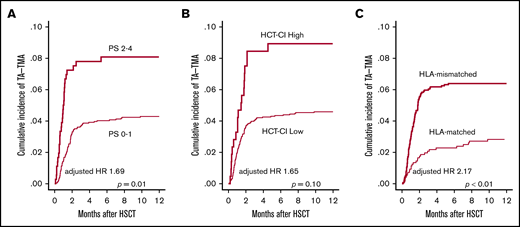

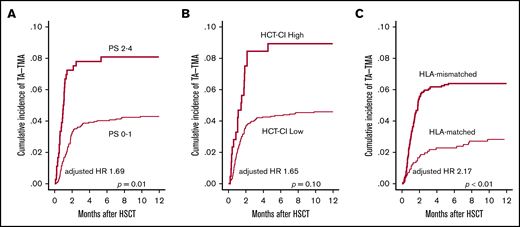

First, we examined pretransplantation risk factors for the development of TA-TMA (Table 2). In the univariate analysis, older age (P = .04), poorer PS (P < .01), higher HCT-CI score (P = .02), CBT (P < .01), and HLA-mismatched donor (P < .01) significantly correlated with the development of TA-TMA (Figure 3A-C; supplemental Figure 2), whereas other factors such as sex, underlying disease, disease risk, prior allo-HSCT, and conditioning regimen did not correlate (Table 2). In the multivariate analysis using the above-mentioned significant pretransplantation factors, poorer PS (HR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.09-2.61; P = .01) and HLA-mismatched donor (HR, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.34-3.52; P < .01) remained significant (Table 2).

Univariate analyses of pretransplantation risk factors for TA-TMA development. The cumulative incidence of TA-TMA was calculated and compared between (A) patients with poor PS (2-4) and those with good PS (0-1), (B) patients with an HCT-CI high score (≥3) and those with a low score of 0-2, and (C) patients who received HLA-mismatched HSCT and those who received HLA-matched HSCT.

Univariate analyses of pretransplantation risk factors for TA-TMA development. The cumulative incidence of TA-TMA was calculated and compared between (A) patients with poor PS (2-4) and those with good PS (0-1), (B) patients with an HCT-CI high score (≥3) and those with a low score of 0-2, and (C) patients who received HLA-mismatched HSCT and those who received HLA-matched HSCT.

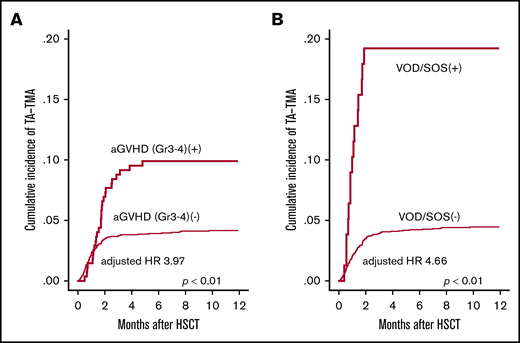

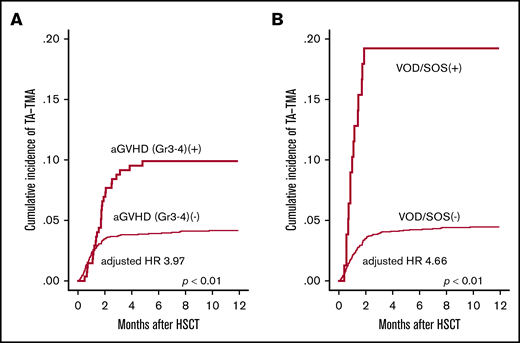

Next, we evaluated the influence of posttransplantation risk factors for the development of TA-TMA. In the univariate analysis, grade 3-4 aGVHD (P < .01), Aspergillus infection (P < .01), CMV reactivation (P < .01), hemorrhagic cystitis (P = .05) and VOD/SOS (P < .01) were significantly correlated with the development of TA-TMA (Figure 4A-B), whereas infections with bacterial, Candida, and CMV were not (Table 3). We further performed multivariate analysis by using the pretransplantation factors (age, PS, HCT-CI, donor source, and HLA mismatch) and posttransplantation factors (grade 3-4 aGVHD, Aspergillus infection, CMV reactivation, hemorrhagic cystitis, and VOD/SOS). In this multivariate model, grade 3-4 aGVHD (HR, 4.02; 95% CI, 2.36-6.83; P < .01), Aspergillus infection (HR, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.15-4.54; P < .01), and VOD/SOS (HR, 4.47; 95% CI, 2.25-8.87; P < .01) were indicated as significant risk factors (Table 3). These analyses were performed treating post-HSCT complications as time-dependent covariates. In the sensitivity analyses in which aGVHD and VOD/SOS were treated as constant covariates, we also observed that aGVHD (HR, 3.66; 95% CI, 2.45-5.48; P < .01) and VOD/SOS (HR, 5.23; 95% CI, 3.17-8.63; P < .01) were significant risk factors for TA-TMA.

Univariate analyses of posttransplantation risk factors for TA-TMA development. The cumulative incidence of TA-TMA was significantly higher in patients who developed (A) severe GVHD (grade 3-4) and (B) VOD/SOS. GVHD and VOD/SOS were treated as time-dependent covariates.

Univariate analyses of posttransplantation risk factors for TA-TMA development. The cumulative incidence of TA-TMA was significantly higher in patients who developed (A) severe GVHD (grade 3-4) and (B) VOD/SOS. GVHD and VOD/SOS were treated as time-dependent covariates.

Because both HLA-mismatched donor and grade 3-4 aGVHD were significant risk factors, we evaluated the statistical interaction between them, finding that GVHD and HLA disparity showed significant interaction toward TA-TMA. In the subgroup analyses regarding HLA disparity, the impact of GVHD on TA-TMA was higher in the HLA-matched subgroup (HR, 7.65; 95% CI, 3.00-19.5; P < .01) than that in the HLA-mismatched subgroup (HR, 3.33; 95% CI, 1.80-6.16; P < .01).

Comparisons of outcomes after treatment of TA-TMA

The therapeutic strategies for TA-TMA were mainly based on the modulation of immunosuppressants and/or addition of other interventions. As for immunosuppressant modulation (N = 115), 85 patients had their CNIs maintained or reduced (the dose of CNI changed to 68.8 ± 13.5% [mean ± standard error] in randomly selected patients), 11 patients had their CNIs switched to a different type of CNI, 10 patients were switched from CNIs to CS, and 9 patients had their CS increased. Meanwhile, additional interventions were used in 86 patients; 47 patients were treated with monotherapy such as rhTM (6; 5.1%), FFP (36; 30.5%), or plasma exchange (4; 3.4%), and 40 patients were treated with combination therapies as follows: FFP+rhTM (13; 11.0%), FFP+PE (11; 9.3%), rhTM+PE (5; 4.2%), or FFP+rhTM+PE (11; 9.3%) (supplemental Table 2).

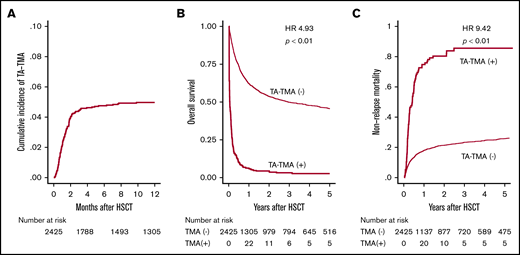

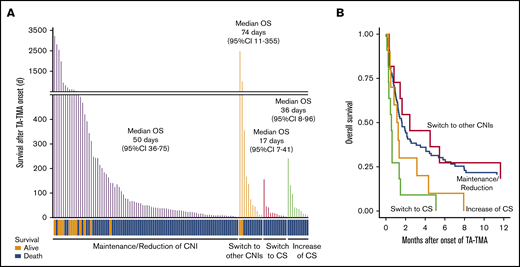

As for the outcomes, the median OS after onset of TA-TMA in the patients who switched their CNIs to CS was remarkably inferior to that of the patients who maintained or reduced their CNIs (17 days; 95% CI, 7-41 vs 50 days; 95% CI, 36-75, P < .01) or to that of the patients who switched their CNIs to a different type (vs 74 days; 95% CI, 11-355, P < .01) (Figure 5A; Table 4). In addition, the death attributed to TA-TMA was more frequently observed in the patients of switch to CS when compared with the patients of maintenance/reduction of CNIs (54.5% vs 17.6%) or the patients of switch to other CNIs (11.1%) (supplemental Table 3).

Continuation of CNI instead of discontinuation improved the outcome of TA-TMA patients. (A) The survival time after TA-TMA onset of the individual patients are shown as bar graphs. TA-TMA patients were divided into 4 groups based on their status of immunosuppressant modulation. The survival status (alive or dead) of each patient is shown at the bottom. The median number of days of OS and 95% CI in each group are displayed. (B) OS after TA-TMA onset was more favorable in the patients who continued the CNI treatment (maintenance/reduction) or were switched to other CNIs than in those for whom CNIs were replaced with CS (switch to CS).

Continuation of CNI instead of discontinuation improved the outcome of TA-TMA patients. (A) The survival time after TA-TMA onset of the individual patients are shown as bar graphs. TA-TMA patients were divided into 4 groups based on their status of immunosuppressant modulation. The survival status (alive or dead) of each patient is shown at the bottom. The median number of days of OS and 95% CI in each group are displayed. (B) OS after TA-TMA onset was more favorable in the patients who continued the CNI treatment (maintenance/reduction) or were switched to other CNIs than in those for whom CNIs were replaced with CS (switch to CS).

To further investigate whether switching from CNIs to CS adversely affected the outcomes of TA-TMA, we performed multivariate analysis focusing on these therapeutic strategies. In the multivariate model, replacement of CNIs with CS (switch to CS) showed significantly inferior outcomes, both in terms of response rate (OR, 0.12; 95% CI, 0.02-0.63; P = .01) and in terms of OS (HR, 3.23; 95% CI, 1.64-6.33; P < .01) compared with CNI maintenance/reduction (Figure 5B). These findings suggested that CNI maintenance/reduction could be a better therapeutic strategy for TA-TMA than switching to CS.

Conversely, the prognostic impact of additional interventions was limited. We found that rhTM did not provide any significant improvement: response rate (OR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.38-2.27; P = .87) and OS (HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.67-1.66; P = .81) (Table 4). We observed similar results for both FFP and PE.

Discussion

This present multicenter retrospective cohort study investigating the risk and outcome of TA-TMA revealed 2 major findings: (1) using predefined and uniform TA-TMA diagnostic criteria, aGVHD, Aspergillus infection, and VOD/SOS were correlated with a significantly higher incidence of subsequent TA-TMA along with other risk factors such as PS and HLA mismatch; and (2) the therapeutic strategy of maintaining or slightly reducing CNI doses resulted in significantly superior outcomes compared with conventional strategies such as replacing CNI with CS (switching from CNI to CS). This study is remarkable also in the sense that one of the largest patient cohorts (N = 2425) was analyzed for incidence, risk factors, and outcome of TA-TMA with the same protocol, including a set of uniform diagnostic criteria for this complication.

Initially, for the diagnosis of TA-TMA, we adopted predefined and uniform diagnostic criteria, and the set of criteria was established as a mixture and modification of those stipulated by EBMT IWG18 and BMT CTN,2 because clinicians usually diagnose TA-TMA and initiate treatment as soon as just some features of the conventional diagnostic criteria are apparent.6,7 It is widely recognized that initiating treatment only when either set of the conventional criteria have been completely satisfied is too late, because organ dysfunction is already typically irreversible at this time point.6 To encourage physicians to try and establish the diagnosis earlier, a Japanese team introduced the concept of “pre-TMA” (defined as a decrease of haptoglobin and progressive thrombocytopenia without disseminated intravascular coagulopathy and Coombs test) and proposed to initiate treatment at this point.19 Our criteria are skewed toward a slightly later phase than those of “pre-TMA” but would appear at a much earlier stage than the conventional diagnostic criteria in the time course of TA-TMA progression.2,18

Using uniform diagnostic criteria for TA-TMA, we confirmed that PS and HLA mismatch (as pretransplant factors) and aGVHD, Aspergillus infection, and VOD/SOS (as posttransplant factors) were significant risk factors for TA-TMA. Basic science results revealed that aGVHD, infection, and VOD/SOS can be triggers of TA-TMA20,21 ; these complications, through donor-derived T-cell activation and production of inflammatory cytokine bursts,22,23 can trigger vascular endothelial injury as a “final common pathway” in TA-TMA.1,20,24

The quality of previous clinico-epidemiological studies has been limited by selection bias. Because these posttransplant complications usually appear during the acute phase after allo-HSCT, a careful review of clinical records and statistical maneuvers are necessary to precisely match the causes with the consequences (whether aGVHD has proceeded TA-TMA [ie, TA-TMA occurred in the cohort with aGVHD] or in turn, TA-TMA was followed by aGVHD [ie, TA-TMA occurred in the cohort without aGVHD]); otherwise, misjudgment at this point causes selection bias and leads to incorrect analyses of risk factors for TA-TMA. Only 1 retrospective study analyzed risk factors for TA-TMA by treating posttransplant factors as time dependent covariates.25 However, most of the previous studies appear to have overlooked the importance of this particular point,26-28 and the results (aGVHD as a risk factor for TA-TMA) are to some extent influenced by this bias. Our analyses were performed after deliberate review and confirmation of clinical records, especially with regard to posttransplant factors, and statistical maneuvers such as treating post-HSCT events as time-dependent variables were adopted. Of 37 patients who experienced TA-TMA and grade 3-4 aGVHD, our clinical record review indicated that aGVHD was followed by TA-TMA only in 27 patients. Risk factor analysis without taking this into account would have led to a bias toward a higher risk ratio of aGVHD regarding TA-TMA,9 and analyses using time-dependent covariates overcame this bias in our study.

In addition to risk factors, we intensively scrutinized the therapeutic strategies implemented after the diagnosis of TA-TMA, and the result went against the conventional guideline strategy of switching from CNI to CS or other drugs.2 This strategy was consistent with the observation that the continuous administration of CNI can damage vascular endothelia and deteriorate TA-TMA.29 However, recent in vitro experiments suggested that moderate concentrations of CNI did not induce severe endothelial damage, whereas extremely high CNI concentrations resulted in these damages in a dose-dependent manner.30 These basic research findings potentially support the continuation of CNI as far as the serum concentration is kept in the moderate range.

The reason why prompt termination of CNI followed by the switch to CS led to the least favorable outcome among all the therapeutic options for TA-TMA could not be completely elucidated in this study because of the wide variety of patient backgrounds and the small number of this cohort. This limitation should be addressed in future study using a larger patient cohort in a prospective manner. An interesting observation in this study is that TA-TMA as the final cause of death was more commonly observed in patients who were switched from CNI to CS when compared with the other subgroups of patients, suggesting that replacement with CS may possibly trigger TA-TMA aggravation and/or coexisting organ damage. Another possibility is a selection bias, that is, patients who could not continue their CNIs because of severe organ damage were selectively included in the CNI to CS group. The other speculation is that the rapid decrease in CNI could aggravate the coexisting aGVHD, which in turn resulted in fatal organ failures and/or infections,31 although we found no statistically significant support for this in this study. Relevant management of aGVHD may be one of the key strategies for securing a better prognosis of TA-TMA.

Other therapeutic maneuvers such as the infusion of rhTM or FFP administration did not show any significant improvement in the outcome after TA-TMA in this study. A previous case series from Japan10 suggested that the efficacy of rhTM in TA-TMA patients might be due to its antithrombotic, anti-inflammatory, and complement-modulating functions, but statistical analysis of the data from our larger cohort failed to find support for their experimental therapy. Other drugs with some potential for TA-TMA such as defibrotide11 or eculizumab12,26,32 were not included in our analysis because these drugs were only recently approved and have not been widely used in our real-world cohort.

Thus, the present study analyzed TA-TMA comprehensively using a relatively large multicenter cohort. However, some limitations to this study exist and must be addressed. For instance, the therapeutic strategy for each patient had not been uniformly decided and was in fact selected at the discretion of the attending physician. Moreover, new agents that can directly improve TA-TMA (rituximab,33 defibrotide,11 and eculizumab12,26 ) were not used in the cohort. Any additional therapeutic effects of these newer drugs should be investigated in future studies in comparison with the current strategy of maintaining or slightly reducing CNIs. Last, post-HSCT clinical data, such as blood pressure or renal function, are not included in this study, which can possibly work as preemptive TA-TMA suggestion markers. Once these limitations have been overcome, highly targeted and complete protocols for prevention and early intervention can be provided.

In summary, we performed a large multicenter cohort retrospective study analyzing incidence, risk factors, therapeutic strategies, and outcomes of TA-TMA by obtaining all the necessary data from clinical records and evaluating these based on a standardized protocol. Our study overcame the previously mentioned challenges such as nonuniform diagnostic criteria and selection bias. We identified risk factors for TA-TMA and suggested the most effective therapeutic strategies such as continuation rather than discontinuation of CNI. We expect that our results and discussions could provide clinically useful information to reduce and properly manage TA-TMA, and in the future, to improve the overall outcome after allo-HSCT along with the effective administration of newer drugs for TA-TMA.

Data sharing requests can be e-mailed to the corresponding author, Yasuyuki Arai (ysykrai@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the physicians and data managers at the centers who contributed valuable data on transplantation and the Kyoto Stem Cell Transplantation Group (KSCTG), which is composed of Kyoto University Hospital, Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital, Japanese Red Cross Osaka Hospital, Kurashiki Central Hospital, Tenri Hospital, Kokura Memorial Hospital, Shizuoka General Hospital, Takatsuki Red Cross Hospital, Japanese Red Cross Wakayama Medical Center, Shinko Hospital, Kyoto City Hospital, Kitano Hospital, Japan Red Cross Otsu Hospital, Kyoto-Katsura Hospital, Shiga General Hospital, Kansai Electric Power Hospital, and Hyogo Prefectural Amagasaki General Medical Center.

This work was supported, in part, by research funding from Takeda Science Foundation, Bristol-Myers Squibb Research Foundation, Koyanagi Foundation, the Uehara Memorial Foundation, and Novartis Foundation in Japan (Y.A.).

Authorship

Contribution: H.M. and Y.A. designed the study, reviewed and analyzed data, and wrote the paper; H.I., T. Mitsuyoshi, N.T., T.K., J.K., and A.T.-K. interpreted data and revised the manuscript; T.I., K.I., Y.U., Y.T., N.A., K.Y., M.N., A.T., N.T., N.I., T.K., M.T., and T. Moriguchi contributed to the data collection and provided critiques on the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

A list of the members of the Kyoto Stem Cell Transplantation Group appears in “Appendix.”

Correspondence: Yasuyuki Arai, Department of Clinical Laboratory Medicine, and Hematology and Oncology, Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, 54 Shogoin Kawahara-cho, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8507, Japan; e-mail: ysykrai@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Appendix

The core members of the Kyoto Stem Cell Transplantation Group are: Hiroyuki Matsui, Yasuyuki Arai, Hiroharu Imoto, Takaya Mitsuyoshi, Naoki Tamura, Tadakazu Kondo, Junya Kanda, Takayuki Ishikawa, Kazunori Imada, Yasunori Ueda, Yusuke Toda, Naoyuki Anzai, Kazuhiro Yago, Masaharu Nohgawa, Akihito Yonezawa, Hiroko Tsunemine, Mitsuru Itoh, Kazuyo Yamamoto, Masaaki Tsuji, Toshinori Moriguchi, and Akifumi Takaori-Kondo.

References

Author notes

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.