Key Points

An AADACL1 ether lipid substrate is phosphorylated in platelets and acts as an endogenous inhibitor of PKC isoforms.

AADACL1 inhibition reduces circulating platelet reactivity and modulates thrombosis and hemostasis in vivo.

Abstract

We previously reported the discovery of a novel lipid deacetylase in platelets, arylacetamide deacetylase-like 1 (AADACL1/NCEH1), and that its inhibition impairs agonist-induced platelet aggregation, Rap1 GTP loading, protein kinase C (PKC) activation, and ex vivo thrombus growth. However, precise mechanisms by which AADACL1 impacts platelet signaling and function in vivo are currently unknown. Here, we demonstrate that AADACL1 regulates the accumulation of ether lipids that impact PKC signaling networks crucial for platelet activation in vitro and in vivo. Human platelets treated with the AADACL1 inhibitor JW480 or the AADACL1 substrate 1-O-hexadecyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol (HAG) exhibited decreased platelet aggregation, granule secretion, Ca2+ flux, and PKC phosphorylation. Decreased aggregation and secretion were rescued by exogenous adenosine 5′-diphosphate, indicating that AADACL1 likely functions to induce dense granule secretion. Experiments with P2Y12−/− and CalDAG GEFI−/− mice revealed that the P2Y12 pathway is the predominate target of HAG-mediated inhibition of platelet aggregation. HAG itself displayed weak agonist properties and likely mediates its inhibitory effects via conversion to a phosphorylated metabolite, HAGP, which directly interacted with the C1a domains of 2 distinct PKC isoforms and blocked PKC kinase activity in vitro. Finally, AADACL1 inhibition in rats reduced platelet aggregation, protected against FeCl3-induced arterial thrombosis, and delayed tail bleeding time. In summary, our data support a model whereby AADACL1 inhibition shifts the platelet ether lipidome to an inhibitory axis of HAGP accumulation that impairs PKC activation, granule secretion, and recruitment of platelets to sites of vascular damage.

Introduction

Platelets respond rapidly to many physiological and pathological stressors, including arterial injury, inflammation, atherosclerotic plaque rupture, and tumor growth. Activated platelets form homotypic (platelet-platelet) and heterotypic (platelet-leukocyte) aggregates that adhere to sites of vascular damage to prevent blood loss in response to physiological cues (hemostasis) or in response to pathological stimuli (thrombosis). For both of these processes, the platelet’s most abundant surface receptor, the αIIbβ3 integrin, is converted to an active conformation that facilitates intracellular signaling, fibrinogen binding, and secretion of bioactive molecules (eg, adenosine 5′-diphosphate [ADP], growth factors, and cytokines) from intracellular granules that amplify initial signals and recruit additional platelets to the site of injury.

Platelet granule secretion amplifies activation through intracellular molecules, including Rap GTPases, and protein kinases, such as protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms, which are activated downstream of phospholipase C, via the phospholipase C products diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol 1,4,5 triphosphate. DAG binds directly to several PKCs, whereas inositol 1,4,5 triphosphate induces intracellular Ca2+ release1 to help activate calcium-sensitive PKCs and other molecules. Human platelets express 3 PKC subfamilies that play nonredundant and antagonistic roles in secretion: “conventional” isoforms (PKCα, PKCβΙ, and PKCβII), “novel” isoforms (PKCδ, PKCθ, and PKCε), and “atypical” isoforms (PKCη and PKCζ).2 Mouse platelets lacking PKCα fail to secrete α or dense granule contents.3 Moreover, small molecule PKC inhibitors suppress platelet secretion, which is consistent with genetic data showing a positive role for PKC in regulating secretion from both α and dense granules, which contain proteins or small molecules (eg, ADP), respectively.4 Interestingly, PKCδ has been implicated as both a positive and a negative regulator of platelet secretion, depending on which agonist receptor is activated,5,6 but how its precise function is integrated with other PKCs is unresolved.

Regulation of PKC isoforms is a multistep process involving lipid and/or calcium signaling. Conventional PKC activation requires DAG binding to tandem C1a and C1b domains in the N-terminus and Ca2+ binding to the C2 domain to relieve autoinhibition.7,8 PKCs are also regulated by ether lipids, such as 1-O-hexadecyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol (HAG), which was originally discovered as a precursor to the vasoactive agonist, platelet activating factor. HAG is more stable than DAG,9 can reportedly inhibit or activate PKC kinase activity in vitro,9-14 and can block PKC translocation to intracellular membranes, most likely via competition with DAG.15,16 Direct HAG binding to PKC C1 domains has been inferred, but unlike DAG or other PKC activators, HAG alone does not increase PKC activity, which suggests a distinct regulatory mechanism.17,18

To identify unique molecular events that regulate human platelet activation, we previously discovered a HAG hydrolase, arylacetamide deacetylase-like 1 (AADACL1/NCEH1), via competitive activity–based protein profiling.19-21 We implicated AADACL1 via its lipid substrate, HAG, as an important regulator of human platelet aggregation and thrombus formation ex vivo, but how AADACL1 regulates these crucial platelet functions or how AADACL1 contributes to in vivo physiology was unknown. Here, we provide compelling evidence that the AADACL1 substrate HAG is converted to a phosphorylated species 1-O-hexadecyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphate (HAGP) over time and that HAGP negatively regulates platelet granule secretion via direct inhibition of PKC isoforms. We also show that HAG itself has agonist properties. Moreover, irreversible AADACL1 inhibition protects against rat arterial thrombosis and delays hemostasis in rats, both of which require platelet activation. Collectively, these data reveal a novel platelet lipid signaling node that regulates PKC signaling networks critical for platelet aggregation, secretion, and clot formation in vivo.

Methods

Human and rodent platelet isolation

Resting human platelets were isolated by gel filtration or centrifugation as described previously20 and in the supplemental Data. Mouse and rat platelets were isolated as described in Stefanini et al22 and in the supplemental Data. All human and rodent experiments were conducted according to approved University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Campbell University Institutional Review Board and Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocols, respectively.

Platelet aggregation and secretion

Pure lipid monomers were dried under N2 and resuspended in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Lipids, the AADACL1 inhibitor JW48023 or the diacylglycerol kinase inhibitor R59022,24 in DMSO were gently mixed with purified human platelets (300 × 109/L) in glass aggregation cuvettes for 0.5 to 30 minutes to final concentrations of 2 to 30 μM at 37°C. For secretion experiments, a luminescence detection reagent (CHRONO-LUME) was added 2 minutes prior to agonist addition. Platelets were stimulated with collagen or convulxin (gift of Ken Clemetson) in the absence of fibrinogen under stirring conditions in a Model 700 Lumi-aggregometer for up to 5 minutes. Mouse and rat platelets (200 × 109/L) were treated as above. Optical aggregation and secretion data were reported as maximum amplitudes and nanomole ATP secreted, respectively. All aggregation reagents and supplies were from Chrono-log Corp.

Intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence

C1a or C1b peptides (50 amino acids) of PKCα or PKCδ were commercially obtained (Bio-synthesis Inc) and reconstituted in the presence of Zn2+ to preserve zinc finger secondary structures. Fluorescence emission (Em340-350) of the single tryptophan (W) within each peptide was measured using excitation 280 nm in a SPEX FluoroLog-3 fluorescence spectrophotometer. Small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) containing dioleoylphosphatidylcholine (DOPC), 5 mol% dioleoylphosphatidylserine (DOPS), and 20 mol% HAG, HAGP, or DAG were made via sonication as described.25 Increasing concentrations of SUVs were incubated with 200 to 500 nM peptide in binding buffer (20 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-1-ethanesulfonic acid pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl) under stirring conditions for 10 replicates. Fluorescence maxima were normalized to fluorescence in the absence of lipid (F0) and fitted to hyperbolic decay curves to calculate a dissociation constant (Kd) using SigmaPlot software.

Kinase assays

Purified PKCα or PKCδ (50 ng; Promega) was pretreated with HAGP monomers for 15 minutes at 37°C in kinase buffer (20 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-1-ethanesulfonic acid pH 7.4, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 1 mM ATP) before addition of peptide substrate (PepTag from Promega) and 16 μM phorbol 12-myristate, 13-acetate (PMA). For vesicle experiments, PKCα was pretreated with vesicles containing 20 mol% DAG and either control vesicles (DOPC and DOPS only) or HAGP vesicles (DOPC, DOPS, and 20 mol% HAGP). The final DAG concentration was estimated to be 16 μM. Reactions proceeded for 1 hour at 37°C and were stopped by the addition of 4 μM Gö6983, a broad-spectrum PKC inhibitor. Reactions were briefly spun and loaded in alternate lanes on 0.8% agarose gels to optimize quantitation. Samples were electrophoresed for 30 minutes in TAE buffer (40 mM Tris-acetate, 1 mM EDTA) to separate phosphorylated and unphosphorylated peptides by charge. Gels were scanned with a Typhoon Trio Variable Mode Imager using a 532-nm excitation wavelength and a 580-nm band pass emission filter. Phosphorylated peptide was quantified with ImageQuant software and expressed as a percentage: phosphorylated peptide/(phosphorylated peptide + unphosphorylated peptide) × 100.

In vivo assays

For platelet aggregation, adult (>6 months) Sprague Dawley (SD) rats were injected with JW480 (8 to 11 mg/kg) or vehicle control (ethanol). Blood was drawn after 4 to 5 hours, and platelet aggregation was measured by the whole blood impedance method.26 For thrombosis assays, SD rats (3.5 to 5 weeks old) were anesthetized with pentobarbital before injection with 40 mg/kg JW480 or ethanol (IV volume 0.14% body weight) for 5 minutes. The right common carotid artery was then exposed to 40% FeCl3 on 2 × 2-mm filter paper for 2 minutes, and blood flow was measured 1 to 2 mm distal to the site of injury for 30 minutes using a Transonic Doppler probe. Time to vessel occlusion (TTO) was defined as the time at which blood flow reached 25% of baseline (flow without FeCl3). Experiments were terminated after 30 minutes, using a TTO of 30 if no occlusion occurred. For tail bleeding, adult SD rats were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane and injected with JW480 or DMSO (IV volume 0.03% body weight) for 5 minutes. After the distal 2 mm was resected, the tail was immersed in warm saline up to 30 minutes. Bleeding time was recorded as the time at which blood flow stopped and did not continue for 30 seconds. All animal experiments were analyzed using Mann-Whitney U nonparametric tests.

Results

The AADACL1 substrate, HAG, inhibits dense granule secretion

We previously showed that pretreatment of platelets with the AADACL1 inhibitor JW480 or the AADACL1 lipid substrate, HAG, reduced human platelet aggregation via unknown mechanisms.20 Because aggregation was inhibited in platelets activated with low agonist concentrations, we hypothesized that AADACL1 regulates platelet secretion, which amplifies agonist-dependent signals. To test this, we pretreated human platelets for 30 minutes with purified HAG or its deacetylated product, 1-O-hexadecyl-sn-glycerol (HG), and measured ATP secretion from dense granules. Exogenous HAG, but not HG, dose-dependently decreased ATP release from collagen-stimulated platelets by 54% ± 15% (Figure 1A). The AADACL1-specific inhibitor, JW480, also blocked collagen-stimulated ATP secretion (45% ± 20%; Figure 1A), suggesting potentially similar mechanisms for both HAG and JW480. However, inhibition of aggregation and secretion by JW480 or HAG were completely reversed by addition of the dense granule component, ADP (Figure 1B-C). Taken together, these data indicate that a major function of human AADACL1 is to metabolize HAG and stimulate the release of ADP via dense granule secretion.

HAG and JW480 inhibit dense granule secretion in human platelets. (A) Washed human platelets (300 × 109/L) were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of HAG, HG, JW480, or DMSO vehicle control (0.5%, not shown) for 30 minutes at room temperature before warming to 37°C for the last 5 minutes. Aggregation was initiated with 1 to 2 μg/mL collagen, and secretion of ATP was measured with the CHRONO-LUME reagent, which was added 2 minutes prior to agonist. The results are normalized to DMSO-treated controls, which were set to 100% (*P < .05 for HAG or JW480 vs HG, n = 4). (B-C) Washed human platelets were pretreated with 10 μM JW480, 10 μM HAG, or DMSO (0.5%) for 30 minutes at 37°C before addition of 0.375 to 1.0 μg/mL collagen. For the indicated samples, ADP (10 μM) was added immediately after collagen, and platelet aggregation (B; ***P < .001, n = 6) or secretion (C; ***P < .001, n = 3) was measured for 3 minutes. n.s., not significant.

HAG and JW480 inhibit dense granule secretion in human platelets. (A) Washed human platelets (300 × 109/L) were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of HAG, HG, JW480, or DMSO vehicle control (0.5%, not shown) for 30 minutes at room temperature before warming to 37°C for the last 5 minutes. Aggregation was initiated with 1 to 2 μg/mL collagen, and secretion of ATP was measured with the CHRONO-LUME reagent, which was added 2 minutes prior to agonist. The results are normalized to DMSO-treated controls, which were set to 100% (*P < .05 for HAG or JW480 vs HG, n = 4). (B-C) Washed human platelets were pretreated with 10 μM JW480, 10 μM HAG, or DMSO (0.5%) for 30 minutes at 37°C before addition of 0.375 to 1.0 μg/mL collagen. For the indicated samples, ADP (10 μM) was added immediately after collagen, and platelet aggregation (B; ***P < .001, n = 6) or secretion (C; ***P < .001, n = 3) was measured for 3 minutes. n.s., not significant.

HAG preferentially inhibits P2Y12 signaling in mouse platelets

Because JW480 treatment blocks collagen-induced Rap1 and PKC activation in platelets,20 AADACL1 most likely regulates (1) a rapid calcium-dependent node involving CalDAG GEFI, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor that activates Rap1; and/or (2) a slower PKC-dependent node that induces granule secretion in response to multiple receptors, including the ADP receptor P2Y12.22 To determine whether one or both of these pathways are regulated by HAG, we pretreated mouse platelets lacking either CalDAG GEFI or P2Y12 with HAG and then stimulated with convulxin, which potently activates platelets via the collagen receptor, glycoprotein VI. HAG pretreatment completely blocked aggregation of CalDAG GEFI−/− platelets (Figure 2A), but only partially blocked aggregation of P2Y12−/− platelets compared with DMSO controls (Figure 2B). Therefore, HAG or a metabolite mainly impacts ADP secretion downstream of P2Y12 signaling, which is still intact in CalDAG GEFI-deficient platelets.

HAG abolishes P2Y12-dependent signaling but only partially inhibits CalDAG GEFI-dependent signaling in mouse platelets. Washed mouse platelets lacking CalDAG GEFI (A) or P2Y12 (B) were pretreated with 10 μM HAG or DMSO for 30 minutes at room temperature and stimulated with 1.25 μg/mL convulxin. Aggregation was observed for 3 minutes (panel A, **P < .007 for HAG vs DMSO; panel B, *P < .05 for HAG vs DMSO, n = 4 for each group).

HAG abolishes P2Y12-dependent signaling but only partially inhibits CalDAG GEFI-dependent signaling in mouse platelets. Washed mouse platelets lacking CalDAG GEFI (A) or P2Y12 (B) were pretreated with 10 μM HAG or DMSO for 30 minutes at room temperature and stimulated with 1.25 μg/mL convulxin. Aggregation was observed for 3 minutes (panel A, **P < .007 for HAG vs DMSO; panel B, *P < .05 for HAG vs DMSO, n = 4 for each group).

Endogenous HAGP is a bioactive metabolite of HAG

Because HAG is an established substrate for AADACL1,19,20,23 endogenous HAG should accumulate when AADACL1 activity is blocked. However, lipidomic analysis revealed that HAG did not accumulate significantly in total lipid extracts from human platelets treated with JW480, even though pull-down experiments with an activity-based probe confirmed that AADACL1 activity was blocked (supplemental Figure 1). We therefore asked if HAG was metabolized to other lipid products. Because HAG can be a substrate for a lipid kinase,27 we searched for a phosphorylated species in human platelets via liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS). In the presence of JW480 and collagen, we detected HAGP (m/z 437.2) by normal phase liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization tandem MS (NPLC-ESI/MS/MS; Figure 3A; supplemental Figure 2). Unstimulated platelets showed a trend toward increased HAGP accumulation, but this did not reach statistical significance (Figure 3A). We also observed a significant, time-dependent increase in the ratio of HAGP to HAG in platelets pretreated with HAG and stimulated with collagen (Figure 3B), consistent with a metabolic conversion of HAG to its phosphorylated species. To determine whether HAGP is a substrate for AADACL1, we isolated microsomal membranes from cells overexpressing human AADACL1 and measured substrate deacetylation. Although AADACL1 deacetylated HAG by 76% ± 3.4%, consistent with previous experiments,19 HAGP was not significantly deacetylated in either control microsomes or AADACL1-overexpressing microsomes (Figure 3C).

Endogenous HAGP accumulates in the absence of AADACL1 activity but is not a substrate of AADACL1. (A) Human platelets were pretreated with 10 μM JW480 or 0.5% DMSO for 10 minutes at 37°C prior to treatment with buffer or 10 μg/mL collagen for 5 minutes. Total lipids were extracted, and ∼10% of the reconstituted lipids were subjected to normal phase LC coupled with high-resolution normal phase liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization tandem MS (NPLC-ESI/MS/MS). HAGP was identified by comparison with a synthetic standard ([M-H]− at m/z 437.2). HAGP levels were normalized to phosphatidylinositol for relative quantitation and expressed as a percentage of HAGP from control platelets treated only with DMSO (*P = .01 for JW480-treated vs DMSO-treated collagen-stimulated samples; n = 3). (B) Human platelets were pretreated with 30 µM HAG or DMSO for the indicated time at 37°C prior to stimulation with 1 μg/mL collagen for 3 minutes. Total lipids were extracted, and ∼2.5% of the reconstituted lipids were subjected to high-resolution MS as in panel A (**P = .001 for HAG-treated 15 minutes plus collagen vs DMSO-treated with no HAG plus collagen; ***P < .0001 for HAG plus collagen 30 minutes vs DMSO-treated with no HAG plus collagen; n = 4). (C) Deacetylation of purified HAGP was tested using AADACL1-expressing microsomes and detected by reverse phase LC-MS. Microsomes from AADACL1-transfected HEK cells (0.1 mg total protein) were incubated with either 20 μM purified HAGP or HAG for 30 minutes at 37°C and extracted with methanol before centrifugation and LC-MS analysis. Integrated peak areas were used for relative quantitation, and HAGP deacetylation (% lipid hydrolysis) was calculated as product/(product + substrate) × 100 (**P < .001 for AADACL1 vs control for HAG; n = 3). (D) Washed human platelets (300 × 109/L) were treated with 10 μM R59022 or 0.5% DMSO for 10 minutes before addition of the indicated concentrations of HAG for an additional 30 minutes. Aggregation (D) and secretion (E) were induced simultaneously with 1 to 2 μg/mL collagen for 4 minutes (*P < .04, **P < .002, and ***P < .001 for R59022 vs control; n = 5). (F) Washed human platelets (3 × 109/L) were incubated with 30 µM HAG or DMSO vehicle control (0.5%) for the indicated times at 37°C. Aggregation was initiated with 0.75 μg/mL collagen, and platelet aggregation was observed for 4 minutes postagonist stimulation (n = 4). (G) Platelets were treated with the indicated concentrations of HAG, and aggregation was observed for 4 minutes postaddition of HAG without collagen (n = 3). (H) Platelets loaded with Fluo-4 were pretreated with either 0.25% DMSO (negative control) or 30 µM HAG for the indicated times prior to stimulation with convulxin (200 ng/mL) in the presence of 1 mM extracellular calcium (n = 5). CVX, convulxin.

Endogenous HAGP accumulates in the absence of AADACL1 activity but is not a substrate of AADACL1. (A) Human platelets were pretreated with 10 μM JW480 or 0.5% DMSO for 10 minutes at 37°C prior to treatment with buffer or 10 μg/mL collagen for 5 minutes. Total lipids were extracted, and ∼10% of the reconstituted lipids were subjected to normal phase LC coupled with high-resolution normal phase liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization tandem MS (NPLC-ESI/MS/MS). HAGP was identified by comparison with a synthetic standard ([M-H]− at m/z 437.2). HAGP levels were normalized to phosphatidylinositol for relative quantitation and expressed as a percentage of HAGP from control platelets treated only with DMSO (*P = .01 for JW480-treated vs DMSO-treated collagen-stimulated samples; n = 3). (B) Human platelets were pretreated with 30 µM HAG or DMSO for the indicated time at 37°C prior to stimulation with 1 μg/mL collagen for 3 minutes. Total lipids were extracted, and ∼2.5% of the reconstituted lipids were subjected to high-resolution MS as in panel A (**P = .001 for HAG-treated 15 minutes plus collagen vs DMSO-treated with no HAG plus collagen; ***P < .0001 for HAG plus collagen 30 minutes vs DMSO-treated with no HAG plus collagen; n = 4). (C) Deacetylation of purified HAGP was tested using AADACL1-expressing microsomes and detected by reverse phase LC-MS. Microsomes from AADACL1-transfected HEK cells (0.1 mg total protein) were incubated with either 20 μM purified HAGP or HAG for 30 minutes at 37°C and extracted with methanol before centrifugation and LC-MS analysis. Integrated peak areas were used for relative quantitation, and HAGP deacetylation (% lipid hydrolysis) was calculated as product/(product + substrate) × 100 (**P < .001 for AADACL1 vs control for HAG; n = 3). (D) Washed human platelets (300 × 109/L) were treated with 10 μM R59022 or 0.5% DMSO for 10 minutes before addition of the indicated concentrations of HAG for an additional 30 minutes. Aggregation (D) and secretion (E) were induced simultaneously with 1 to 2 μg/mL collagen for 4 minutes (*P < .04, **P < .002, and ***P < .001 for R59022 vs control; n = 5). (F) Washed human platelets (3 × 109/L) were incubated with 30 µM HAG or DMSO vehicle control (0.5%) for the indicated times at 37°C. Aggregation was initiated with 0.75 μg/mL collagen, and platelet aggregation was observed for 4 minutes postagonist stimulation (n = 4). (G) Platelets were treated with the indicated concentrations of HAG, and aggregation was observed for 4 minutes postaddition of HAG without collagen (n = 3). (H) Platelets loaded with Fluo-4 were pretreated with either 0.25% DMSO (negative control) or 30 µM HAG for the indicated times prior to stimulation with convulxin (200 ng/mL) in the presence of 1 mM extracellular calcium (n = 5). CVX, convulxin.

To test whether conversion of HAG to HAGP is required for the inhibitory properties of HAG, we pretreated human platelets with the DAG kinase inhibitor R59022, which specifically targets Ca2+-dependent isoforms, such as DGKα,24 prior to stimulation with collagen. R59022 largely prevented HAG inhibition of aggregation (Figure 3D) and secretion (Figure 3E). These data suggest that HAG can be phosphorylated by a Ca2+-sensitive DGK isoform and that HAGP is the primary lipid involved in HAG-mediated inhibition of human platelets. To further understand this mechanism, we conducted a time course of HAG pretreatment during collagen-induced platelet aggregation. Pretreatment with a high concentration of HAG (30 μM) for 30 minutes completely inhibited aggregation, as expected (Figure 3F). Surprisingly, very short times of HAG pretreatment enhanced the kinetics of collagen-induced aggregation, suggesting that HAG itself might have weak agonist properties that diminish upon metabolism to HAGP. In fact, HAG addition to stirred platelets was sufficient to induce shape change (Figure 3G) and Ca2+ flux (Figure 3H) in the absence of agonist, whereas Ca2+ flux was decreased in convulxin-stimulated platelets at later times that correlated with HAGP production (Figure 3H). Thus, temporal HAGP accumulation correlates with inhibition of aggregation, secretion, and Ca2+ signaling and strongly implicates HAGP as a key endogenous regulator of platelet activation, whereas HAG itself appears to be a weak agonist.

HAGP binds C1 domains and inhibits PKCα kinase activity

Both conventional and novel PKC isoforms contain highly homologous tandem lipid binding domains, termed C1a and C1b, each having high affinity for PKC activators like DAG and DAG mimetics, such as PMA.17,28 To test if HAG or HAGP directly associates with PKC C1 domains, we measured changes in intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence of peptides representing the entire C1a domain of human PKCα or PKCδ incubated with small unilamellar phospholipid vesicles (SUVs) supplemented with HAG, HAGP, or DAG as a positive control. HAGP vesicles bound to the PKCα C1a domain with a Kd similar to that of DAG-containing vesicles (Table 1; Kd of 5.4 vs 5.5 nM). Similarly, HAGP- and HAG-containing vesicles bound equally well to the C1a domain of the PKCδ isoform (Kd of 25 and 21 nM, respectively), which was comparable to DAG binding (Kd of 15 nM).

Because HAGP directly interacted with C1 domains, we asked whether HAGP affected PKCα or PKCδ kinase activity. Recombinant, human PKCα, or PKCδ was pretreated with HAGP monomers or large unilamellar vesicles containing HAGP and stimulated with PMA to activate PKCs as measured by the phosphorylation of a fluorescent peptide substrate. Increasing concentrations of HAGP monomers reduced PMA-stimulated PKCα activity below unstimulated levels, with a 50% inhibitory concentration of 8.8 ± 2.7 μM (Figure 4A solid line). Pretreatment with HAGP-containing vesicles also impaired DAG-induced PKCα activation (Figure 4B). Importantly, PKCα pretreatment with JW480 did not affect kinase activity (supplemental Figure 3), which reinforces the selectivity of this compound. Neither HAG nor HAGP stimulated PKCα activity in the absence of PMA or DAG, consistent with previous reports (data not shown).18 The effect of HAGP monomers on PKCδ activity, however, was not conclusive due to poor stimulation of kinase activity by PMA (Figure 4C). We therefore used another approach described below to determine the effects of AADACL1 signaling on PKCδ.

HAGP inhibits PKC kinase activity in vitro. (A) Recombinant, human PKCα (50 ng) was pretreated with the indicated concentrations of HAGP monomers for 15 minutes at 37°C and stimulated with 16 μM PMA in the presence of a fluorescent peptide substrate. Basal kinase activity in the absence of HAGP and PMA is shown by the dashed line (*P < .04 for 20 and 40 µM HAGP treatment vs no HAGP; n = 7). (B) PKCα was pretreated with control vesicles containing 95 mol% DOPC and 5 mol% DOPS (solid line), or HAGP vesicles containing 75 mol% DOPC, 5 mol% DOPS, and 20 mol% HAGP (dashed line) and stimulated with separate vesicles containing DAG (16 μM final), and phosphorylation was measured as above (*P < .05 for HAGP vs control; n = 6). (C) Human, recombinant PKCδ was pretreated as in panel A. Basal kinase activity in the absence of HAGP is depicted by the dashed line, whereas PMA stimulation is shown by the solid line (n = 5).

HAGP inhibits PKC kinase activity in vitro. (A) Recombinant, human PKCα (50 ng) was pretreated with the indicated concentrations of HAGP monomers for 15 minutes at 37°C and stimulated with 16 μM PMA in the presence of a fluorescent peptide substrate. Basal kinase activity in the absence of HAGP and PMA is shown by the dashed line (*P < .04 for 20 and 40 µM HAGP treatment vs no HAGP; n = 7). (B) PKCα was pretreated with control vesicles containing 95 mol% DOPC and 5 mol% DOPS (solid line), or HAGP vesicles containing 75 mol% DOPC, 5 mol% DOPS, and 20 mol% HAGP (dashed line) and stimulated with separate vesicles containing DAG (16 μM final), and phosphorylation was measured as above (*P < .05 for HAGP vs control; n = 6). (C) Human, recombinant PKCδ was pretreated as in panel A. Basal kinase activity in the absence of HAGP is depicted by the dashed line, whereas PMA stimulation is shown by the solid line (n = 5).

HAG modulates PKCδ phosphorylation in platelets

Although the above experiments demonstrated that purified PKCα could be inhibited by HAGP, they did not provide insight into which PKCs are affected by HAGP in platelets. Because PKCα is constitutively phosphorylated on 3 conserved serine/threonine residues independently of agonists (data not shown and Steinberg29 ), we measured PKCδ phosphorylation on T505, which occurs in an agonist-dependent manner.30 Collagen stimulation markedly increased PKCδ T505 phosphorylation in human platelets (Figure 5A), which was reduced dose-dependently by JW480 (Figure 5A-B). In contrast, PKCθ phosphorylation at the homologous residue, T538, was unaffected by agonist or JW480, which is consistent with a previous report.31 Similarly, HAG-pretreated platelets showed a significant decrease in PKCδ but not PKCθ phosphorylation (Figure 5C-D). HAG activity was confirmed by measuring aggregation before platelet lysis (supplemental Figure 4). Taken together, these data indicate that inhibition of AADACL1 specifically modulates PKCδ but not PKCθ phosphorylation, most likely due to the interaction of HAGP with PKC C1 domains.

AADACL1 inhibition reduces PKCδ but not PKCθ phosphorylation in human platelets. (A) Human platelets were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of JW480 as in Figure 1 and stimulated with 0.375 to 1 μg/mL collagen. Platelets were lysed in 10 mM CHAPS buffer on ice, and PKCδ phosphothreonine 505 (T505) or PKCθ phosphothreonine 538 (T538) was detected with specific antibodies. Pleckstrin and total PKCδ served as loading controls for panels A and C, respectively. (B) Phosphorylation of T505 and T538 was quantified with ImageJ from data in panel A (*P < .05 for PKCδ T505 DMSO vs 10 μM JW480; n = 2). (C) Human platelets were treated with the indicated concentrations of HAG, stimulated with 0.375 μg/mL collagen, and then prepared as in panel A. (D) Phosphorylation of T505 and T538 was quantified with ImageJ from data in panel C (*P < .04 for PKCδ T505 in “no HAG” without collagen vs “no HAG” with collagen; **P < .02 for PKCδ T505 “no HAG” plus collagen vs 10 μM HAG plus collagen; n = 3).

AADACL1 inhibition reduces PKCδ but not PKCθ phosphorylation in human platelets. (A) Human platelets were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of JW480 as in Figure 1 and stimulated with 0.375 to 1 μg/mL collagen. Platelets were lysed in 10 mM CHAPS buffer on ice, and PKCδ phosphothreonine 505 (T505) or PKCθ phosphothreonine 538 (T538) was detected with specific antibodies. Pleckstrin and total PKCδ served as loading controls for panels A and C, respectively. (B) Phosphorylation of T505 and T538 was quantified with ImageJ from data in panel A (*P < .05 for PKCδ T505 DMSO vs 10 μM JW480; n = 2). (C) Human platelets were treated with the indicated concentrations of HAG, stimulated with 0.375 μg/mL collagen, and then prepared as in panel A. (D) Phosphorylation of T505 and T538 was quantified with ImageJ from data in panel C (*P < .04 for PKCδ T505 in “no HAG” without collagen vs “no HAG” with collagen; **P < .02 for PKCδ T505 “no HAG” plus collagen vs 10 μM HAG plus collagen; n = 3).

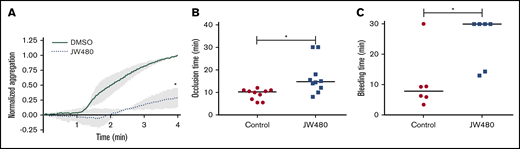

AADACL1 regulates platelet function in vivo

Our data point to a role for AADACL1 as a novel regulator of ether lipid crosstalk with PKC signaling in human platelets. We therefore asked whether inhibition of AADACL1 impacted circulating platelet function in rats, which abundantly express platelet AADACL1 (supplemental Figure 5A), unlike mice.20 Blood drawn from JW480- vs vehicle-treated rats exhibited a pronounced inhibition of platelet aggregation as detected by whole blood aggregometry (Figure 6A). Consistent with our previous results with isolated human platelets,20 JW480 treatment dose-dependently inhibited aggregation of purified rat platelets (supplemental Figure 5B-C). We next assessed the ability of JW480 to impact thrombosis induced by FeCl3 injury of rat carotid arteries. Although the control group occluded 10.3 minutes after injury, the JW480-treated group showed delayed occlusion at 14.8 minutes (Figure 6B). Although 2 JW480-treated rats did not occlude during the maximum time allowed by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocol, this did not affect the median time to occlusion (TTO). To assess the effects of AADACL1 inhibition on hemostasis, we conducted tail bleeding assays on rats injected with JW480. JW480 significantly increased bleeding times compared with controls (30.0 vs 7.78 minutes, respectively; Figure 6C); similar to the thrombosis assay, 4 JW480-treated rats did not clot within the time allowed. Thus, inhibition of AADACL1 blocked platelet aggregation, protected against FeCl3-induced thrombosis, and impaired hemostasis in vivo, which establishes an important physiological role for AADACL1 in the platelet response to vascular injury.

JW480 impedes thrombosis and hemostasis. (A) Adult SD rats were injected IV with vehicle control or 8 to 11 mg/kg JW480 for 3 hours before blood was harvested into acid citrate dextrose. Platelet function was measured in recalcified blood using impedance aggregometry in response to 50 to 100 ng/mL convulxin. Aggregation was normalized to the maximum value observed in the absence of JW480, which was set to 1.0 (*P < .04; n = 3). (B) Adolescent SD rats (3.5 to 5 weeks old) were injected IV with vehicle control or 40 mg/kg JW480 for 5 minutes. Carotid artery thrombosis was induced with 40% FeCl3 for 2 minutes and scored as the “time to occlusion,” which is defined as reduction of blood flow to 25% of normal levels prior to injection of JW480 (control 10.3 minutes vs JW480 14.8 minutes; *P < .004; n = 10 per group). (C) Adult SD rats (≥6 months) were injected IV with vehicle control or 3.5 to 10 mg/kg JW480 as in panel B before measuring bleeding times from lateral tail veins (control 30 vs JW480 7.8 minutes; *P < .03; n = 6 per group). TTO and bleeding data were expressed as medians and analyzed using Mann-Whitney U tests.

JW480 impedes thrombosis and hemostasis. (A) Adult SD rats were injected IV with vehicle control or 8 to 11 mg/kg JW480 for 3 hours before blood was harvested into acid citrate dextrose. Platelet function was measured in recalcified blood using impedance aggregometry in response to 50 to 100 ng/mL convulxin. Aggregation was normalized to the maximum value observed in the absence of JW480, which was set to 1.0 (*P < .04; n = 3). (B) Adolescent SD rats (3.5 to 5 weeks old) were injected IV with vehicle control or 40 mg/kg JW480 for 5 minutes. Carotid artery thrombosis was induced with 40% FeCl3 for 2 minutes and scored as the “time to occlusion,” which is defined as reduction of blood flow to 25% of normal levels prior to injection of JW480 (control 10.3 minutes vs JW480 14.8 minutes; *P < .004; n = 10 per group). (C) Adult SD rats (≥6 months) were injected IV with vehicle control or 3.5 to 10 mg/kg JW480 as in panel B before measuring bleeding times from lateral tail veins (control 30 vs JW480 7.8 minutes; *P < .03; n = 6 per group). TTO and bleeding data were expressed as medians and analyzed using Mann-Whitney U tests.

Discussion

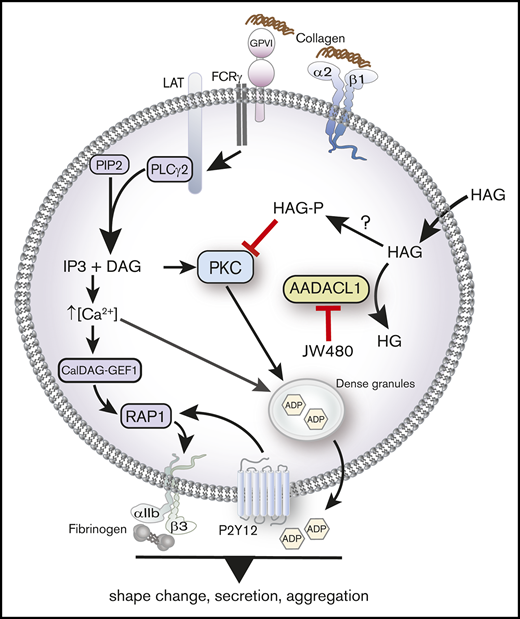

We previously identified AADACL1 as a lipid deacetylase in human platelets that positively regulates platelet function through an unknown mechanism. Based on our new pharmacological, biochemical, and in vivo data, we now propose that AADACL1 and the HAG metabolite, HAGP, contribute to platelet function in both purified and circulating platelets, most likely by inhibiting PKC-dependent secretion (Figure 7). Importantly, decreased aggregation and secretion caused by HAG or JW480, the selective inhibitor of AADACL1,23 can be restored to normal levels by the coaddition of ADP, a secondary agonist normally secreted from dense granules. ADP addition also bypasses aggregation defects in mouse platelets lacking PKCα, which display severely impaired dense granule biogenesis and nearly absent α and dense granule secretion.3

AADACL1 metabolizes HAG to modulate PKC signaling in human platelets. Collagen binding to glycoprotein VI and α2β1 receptors initiates complex signaling cascades leading to the release of intracellular Ca2+ and formation of DAG, which activate the small GTPase Rap1 and PKC isoforms. PKC mediates ADP release from dense granules, which directly stimulates ADP receptors that contribute to αIIbβ3 integrin activation, fibrinogen binding, and subsequent platelet aggregation. We and others have determined that AADACL1 hydrolyzes the endogenous inhibitory lipid HAG to its inactive metabolite HG and that HAG can be rapidly converted to a phosphorylated metabolite called HAGP by an unknown lipid kinase that may be DGK. We show here for the first time that HAGP directly interacts with PKCα C1 domains and reduces kinase activity. Because HAGP is not a substrate for AADACL1, however, its levels are likely controlled by AADACL1-dependent hydrolysis of the HAGP precursor, HAG. We therefore propose that either inhibition of AADACL1 by JW480 or administration of high extracellular HAG concentrations results in accumulation of HAGP, which potentially competes for DAG binding to PKC isoforms to inhibit PKC activity and ultimately impairs ADP release and platelet aggregation.

AADACL1 metabolizes HAG to modulate PKC signaling in human platelets. Collagen binding to glycoprotein VI and α2β1 receptors initiates complex signaling cascades leading to the release of intracellular Ca2+ and formation of DAG, which activate the small GTPase Rap1 and PKC isoforms. PKC mediates ADP release from dense granules, which directly stimulates ADP receptors that contribute to αIIbβ3 integrin activation, fibrinogen binding, and subsequent platelet aggregation. We and others have determined that AADACL1 hydrolyzes the endogenous inhibitory lipid HAG to its inactive metabolite HG and that HAG can be rapidly converted to a phosphorylated metabolite called HAGP by an unknown lipid kinase that may be DGK. We show here for the first time that HAGP directly interacts with PKCα C1 domains and reduces kinase activity. Because HAGP is not a substrate for AADACL1, however, its levels are likely controlled by AADACL1-dependent hydrolysis of the HAGP precursor, HAG. We therefore propose that either inhibition of AADACL1 by JW480 or administration of high extracellular HAG concentrations results in accumulation of HAGP, which potentially competes for DAG binding to PKC isoforms to inhibit PKC activity and ultimately impairs ADP release and platelet aggregation.

We demonstrated that HAG treatment dramatically inhibited platelet aggregation in mouse platelets lacking the Rap1 exchange factor CalDAG GEFI (CalDAG GEFI−/−; Figure 2A). CalDAG GEFI−/− platelets display severely reduced Rap1 activation and platelet aggregation, yet some Rap1 activation remains due to PKC-mediated ADP secretion.22,32 However, when CalDAG GEFI−/− platelets are treated with antagonists to the ADP receptor P2Y12, these platelets fail to activate Rap1 or PKC and do not aggregate even in response to high concentrations of agonist.22 Therefore, HAG (or more likely HAGP) behaves similarly to P2Y12 antagonists in that it completely blocked aggregation in the absence of CalDAG GEFI, presumably by disrupting ADP secretion. However, because HAG treatment partially inhibited aggregation in P2Y12−/− platelets (Figure 2B), other mechanisms may also exist. One such mechanism may be reduced Ca2+-dependent signaling because we showed here that HAG reduced convulxin-stimulated Ca2+ flux in human platelets (Figure 3F). If decreased Ca2+ flux also occurs in P2Y12−/− mouse platelets treated with HAG, this may explain the partial decrease in aggregation observed in Figure 2B.

Despite HAG being an excellent substrate for AADACL1,19,20,23 we found no evidence of HAG accumulation upon AADACL1 inhibition (supplemental Figure 1). Instead, we detected significant HAGP accumulation in platelets treated with either JW480 or HAG, which is consistent with previous reports in rabbit platelets showing rapid conversion of HAG to phosphorylated species, including HAGP.33 Even though HAGP accumulated under these conditions, we showed that HAGP is a poor substrate for AADACL1 in vitro, suggesting that HAGP levels are indirectly modulated by AADACL1-dependent metabolism of its precursor HAG. In fact, HAGP levels may be directly controlled by calcium-sensitive diacylglycerol kinases (eg, DGKα). DGKα is expressed in human platelets,27,34 and when platelets are pretreated with a small molecule DGK inhibitor, R59022, HAG-mediated inhibition of aggregation and secretion was blocked (Figure 3D-E). This suggests that calcium-sensitive DGKs potentially catalyze the phosphorylation of HAG to HAGP and that this conversion is critical for HAG-mediated inhibition in human platelets. Because R59022 has also been shown to act as a serotonin receptor antagonist,24 however, these results do not formally exclude other mechanisms.

In addition to its inhibitory properties, which are likely indirect, HAG acted as a weak platelet agonist depending on time of exposure. When platelets were exposed to HAG for <5 minutes, the rate of collagen-induced aggregation was accelerated (Figure 3F). Moreover, HAG itself induced platelet shape change and Ca2+ flux at these early time points in the absence of agonist (Figure 3G-H). Whether HAG itself has agonist properties or is rapidly converted to another product that induces shape change and Ca2+ flux is unknown.35,36

HAG has most often been described as an inhibitor of PKC/DAG signaling, but also as an activator of PKCs.9-14,37,38 Slater et al showed an HAG-dependent increase in the activity of various PKCs isoforms when induced by PMA, which may be due to an interaction between HAG and low-affinity phorbol ester binding sites that enhance high-affinity phorbol ester binding.18 We observed that HAGP either presented as monomers or incorporated into phospholipid vesicles inhibited purified, full-length PKCα kinase activity stimulated with PMA or DAG. Because PMA and DAG bind to well-described C1 lipid-binding domains of various PKC isoforms to relieve autoinhibition, we speculate that HAGP might compete with PMA or DAG for binding to one or both PKC C1 domains to interfere with kinase activity and/or cellular membrane localization. We also observed that small unilamellar vesicles containing HAGP or HAG bound to C1a domain peptides from PKCα and PKCδ with high affinity, similar to vesicles containing DAG. Absolute molar quantities of HAG or HAGP are unknown in cells, however, so proof of an intracellular competition mechanism with DAG will require further investigation. Furthermore, HAGP does not stimulate kinase activity in the absence of PMA or other PKC activators and is therefore not a DAG or PMA mimetic but an antagonist, which is similar to the behavior of other uncharged ether lipids that interact with PKC.18 In contrast, HAGP appeared to enhance rather than inhibit PKCδ kinase activity in vitro, but this was not statistically significant, possibly due to the low dynamic range of PKCδ activity under these conditions.

The activation loop of some novel PKCs, including PKCδ T505, is phosphorylated in an agonist-dependent manner in a variety of cell types, including platelets.30,39-41 In our experiments, HAG or JW480 treatment inhibited agonist-induced PKCδ phosphorylation, which correlated with reduced collagen-stimulated platelet function. However, Bhavanasi et al42 showed that specific inhibition of PKCδ both inhibits and potentiates platelet granule secretion depending on the agonist, whereas another group reported that PKCδ inhibition has no effect on platelet secretion.6 Collectively, these data suggest a complex modulation of PKCδ activity given its multiple, seemingly conflicting roles in platelet function.

We provide evidence that AADACL1 regulates platelet aggregation in the context of thrombosis and hemostasis in rats: pharmacological inhibition of AADACL1 via JW480 prolonged occlusion time in an acute model of thrombosis and bleeding time in a model of hemostasis. Although these effects of JW480 are very likely due to its ability to directly inhibit platelet function, it is possible that JW480 also affects thrombin generation or other procoagulation events, but this will require further investigation. Inhibition of AADACL1 in rats (except for increased bleeding time) produced similar thrombotic and secretion phenotypes compared with wild-type mice treated with PKC inhibitors and to mouse platelets from PKCα−/− mice.3,43 PKCδ−/− mice, in contrast, exhibit faster occlusion times in carotid arteries,5 consistent with a role for novel PKCs as negative regulators of platelet activation.44 Because AADACL1 is not expressed in mouse platelets and negatively impacted at least 2 PKC isoforms thought to have opposing actions, AADACL1-dependent mechanisms may not recapitulate mouse models of thrombosis and hemostasis.

In summary, we propose a molecular model in which AADACL1 metabolizes and prevents the accumulation of inhibitory ether lipids that modulate PKC-dependent secretion in vitro and in vivo. HAG appears to be a weak agonist, but through its metabolite HAGP, negatively regulates platelet secretion and aggregation, inhibits PKC activity/phosphorylation, and likely protects against acute thrombosis while also impacting hemostasis (Figure 7). Analysis of signaling nodes involving ether lipid-protein interactions should provide insight into the metabolic scope of AADACL1 and further address the physiological contribution of this enzyme to the closely interwoven processes of thrombosis and hemostasis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the blood donors. They also thank David Paul (Bergmeier Laboratory) for providing the reagents and expertise for the Ca2+ flux experiment.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants 5R01HL126124 (L.V.P. and S.P.H.) and 5R01HL130404 (W.B.).

Authorship

Contribution: S.P.H., N.G., P.W., A.W., L.L., Z.G., B.C., H.R.A., R.G.P., R.P., and R.M. performed experiments; S.P.H., N.G., and T.M.L. created the figures; S.P.H., W.B., N.G., and L.V.P. designed the research; and S.P.H., N.G., and L.V.P. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for P.W. is Rockefeller University, New York, NY.

The current affiliation for A.W. is Nova Southeastern University, Davie, FL.

The current affiliation for R.P. is Dignify Therapeutics, Durham, NC.

Correspondence: Stephen P. Holly, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, Campbell University, PO Box 1090, 205 Day Dorm Rd, Buies Creek, NC 27506; e-mail: sholly@campbell.edu.

References

Author notes

Send data sharing requests via e-mail to Stephen P. Holly (sholly@campbell.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![Endogenous HAGP accumulates in the absence of AADACL1 activity but is not a substrate of AADACL1. (A) Human platelets were pretreated with 10 μM JW480 or 0.5% DMSO for 10 minutes at 37°C prior to treatment with buffer or 10 μg/mL collagen for 5 minutes. Total lipids were extracted, and ∼10% of the reconstituted lipids were subjected to normal phase LC coupled with high-resolution normal phase liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization tandem MS (NPLC-ESI/MS/MS). HAGP was identified by comparison with a synthetic standard ([M-H]− at m/z 437.2). HAGP levels were normalized to phosphatidylinositol for relative quantitation and expressed as a percentage of HAGP from control platelets treated only with DMSO (*P = .01 for JW480-treated vs DMSO-treated collagen-stimulated samples; n = 3). (B) Human platelets were pretreated with 30 µM HAG or DMSO for the indicated time at 37°C prior to stimulation with 1 μg/mL collagen for 3 minutes. Total lipids were extracted, and ∼2.5% of the reconstituted lipids were subjected to high-resolution MS as in panel A (**P = .001 for HAG-treated 15 minutes plus collagen vs DMSO-treated with no HAG plus collagen; ***P < .0001 for HAG plus collagen 30 minutes vs DMSO-treated with no HAG plus collagen; n = 4). (C) Deacetylation of purified HAGP was tested using AADACL1-expressing microsomes and detected by reverse phase LC-MS. Microsomes from AADACL1-transfected HEK cells (0.1 mg total protein) were incubated with either 20 μM purified HAGP or HAG for 30 minutes at 37°C and extracted with methanol before centrifugation and LC-MS analysis. Integrated peak areas were used for relative quantitation, and HAGP deacetylation (% lipid hydrolysis) was calculated as product/(product + substrate) × 100 (**P < .001 for AADACL1 vs control for HAG; n = 3). (D) Washed human platelets (300 × 109/L) were treated with 10 μM R59022 or 0.5% DMSO for 10 minutes before addition of the indicated concentrations of HAG for an additional 30 minutes. Aggregation (D) and secretion (E) were induced simultaneously with 1 to 2 μg/mL collagen for 4 minutes (*P < .04, **P < .002, and ***P < .001 for R59022 vs control; n = 5). (F) Washed human platelets (3 × 109/L) were incubated with 30 µM HAG or DMSO vehicle control (0.5%) for the indicated times at 37°C. Aggregation was initiated with 0.75 μg/mL collagen, and platelet aggregation was observed for 4 minutes postagonist stimulation (n = 4). (G) Platelets were treated with the indicated concentrations of HAG, and aggregation was observed for 4 minutes postaddition of HAG without collagen (n = 3). (H) Platelets loaded with Fluo-4 were pretreated with either 0.25% DMSO (negative control) or 30 µM HAG for the indicated times prior to stimulation with convulxin (200 ng/mL) in the presence of 1 mM extracellular calcium (n = 5). CVX, convulxin.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/3/22/10.1182_bloodadvances.2018030767/2/m_advances030767f3.png?Expires=1761944526&Signature=ofLEyYgbneKrpwFuXTG8vcCQ7DB8aR8rVRZRVxUwIFqtkwA4kncsHs3UlDRhvDGkK-VOljryZy0E8zDsWqvTonMlscwvrut5-xBhfVsfJQtDaibqJSxhikhjBgrrGCLto6cR~ANE0QC6mE3RX3bLoYSmaKMcj8KCaWQh1dHHEZaa2h~J7OuzXNSs5qh3gYCLPNfMB7C3~GRsiNEd2NGTjr3JbKdAlAR5URGSZOtrUETx3aKJxhai0l-jbRqIthHGC-liwv4nAcATxY4wuKp4HAJQM-jojzch2alEb7cKbeM8ks-sv7I-0iJQ9nWuxGJSJHMdrI45Q99otP2lhGrPKg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Endogenous HAGP accumulates in the absence of AADACL1 activity but is not a substrate of AADACL1. (A) Human platelets were pretreated with 10 μM JW480 or 0.5% DMSO for 10 minutes at 37°C prior to treatment with buffer or 10 μg/mL collagen for 5 minutes. Total lipids were extracted, and ∼10% of the reconstituted lipids were subjected to normal phase LC coupled with high-resolution normal phase liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization tandem MS (NPLC-ESI/MS/MS). HAGP was identified by comparison with a synthetic standard ([M-H]− at m/z 437.2). HAGP levels were normalized to phosphatidylinositol for relative quantitation and expressed as a percentage of HAGP from control platelets treated only with DMSO (*P = .01 for JW480-treated vs DMSO-treated collagen-stimulated samples; n = 3). (B) Human platelets were pretreated with 30 µM HAG or DMSO for the indicated time at 37°C prior to stimulation with 1 μg/mL collagen for 3 minutes. Total lipids were extracted, and ∼2.5% of the reconstituted lipids were subjected to high-resolution MS as in panel A (**P = .001 for HAG-treated 15 minutes plus collagen vs DMSO-treated with no HAG plus collagen; ***P < .0001 for HAG plus collagen 30 minutes vs DMSO-treated with no HAG plus collagen; n = 4). (C) Deacetylation of purified HAGP was tested using AADACL1-expressing microsomes and detected by reverse phase LC-MS. Microsomes from AADACL1-transfected HEK cells (0.1 mg total protein) were incubated with either 20 μM purified HAGP or HAG for 30 minutes at 37°C and extracted with methanol before centrifugation and LC-MS analysis. Integrated peak areas were used for relative quantitation, and HAGP deacetylation (% lipid hydrolysis) was calculated as product/(product + substrate) × 100 (**P < .001 for AADACL1 vs control for HAG; n = 3). (D) Washed human platelets (300 × 109/L) were treated with 10 μM R59022 or 0.5% DMSO for 10 minutes before addition of the indicated concentrations of HAG for an additional 30 minutes. Aggregation (D) and secretion (E) were induced simultaneously with 1 to 2 μg/mL collagen for 4 minutes (*P < .04, **P < .002, and ***P < .001 for R59022 vs control; n = 5). (F) Washed human platelets (3 × 109/L) were incubated with 30 µM HAG or DMSO vehicle control (0.5%) for the indicated times at 37°C. Aggregation was initiated with 0.75 μg/mL collagen, and platelet aggregation was observed for 4 minutes postagonist stimulation (n = 4). (G) Platelets were treated with the indicated concentrations of HAG, and aggregation was observed for 4 minutes postaddition of HAG without collagen (n = 3). (H) Platelets loaded with Fluo-4 were pretreated with either 0.25% DMSO (negative control) or 30 µM HAG for the indicated times prior to stimulation with convulxin (200 ng/mL) in the presence of 1 mM extracellular calcium (n = 5). CVX, convulxin.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/3/22/10.1182_bloodadvances.2018030767/2/m_advances030767f3.png?Expires=1763021997&Signature=jABYzt3IS561Z-LNOVQYuPfc9nW1kGg99MgFdizF923g8zJC3W1jY-KDggNEjp2~gMdqibArvGyC-W4mchpKgHCGSbPvnxsRpN7cHCf89~31yGB-hhWG8g-9cxLB7jwFYKGIuQ97TVu496yNUBu3mwjJIppBB6xCiCRrTLzwRrrlIZ4nZ7j1Beqgmb9T79zc~vOa2HgVqalMx4XlyC3B722JaaMo3kyM-9YXxW8qsEWcvZ1xeeBAwJ0F6NHZEB8zDp4olmrLYMtL6lfZ9oy0WCNywRfMHARr9sOjvmScEcZwrcoWdNHyKILUjlKt4uf99DokqQsdkdxQU3V7CMtX0Q__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)