Abstract

Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is an expensive, resource-intensive, and medically complicated modality for treatment of many hematologic disorders. A well-defined care coordination model through the continuum can help improve health care delivery for this high-cost, high-risk medical technology. In addition to the patients and their families, key stakeholders include not only the transplantation physicians and care teams (including subspecialists), but also hematologists/oncologists in private and academic-affiliated practices. Initial diagnosis and care, education regarding treatment options including HCT, timely referral to the transplantation center, and management of relapse and late medical or psychosocial complications after HCT are areas where the referring hematologists/oncologists play a significant role. Payers and advocacy and community organizations are additional stakeholders in this complex care continuum. In this article, we describe a care coordination framework for patients treated with HCT within the context of coordination issues in care delivery and stakeholders involved. We outline the challenges in implementing such a model and describe a simplified approach at the level of the individual practice or center. This article also highlights ongoing efforts from physicians, medical directors, payer representatives, and patient advocates to help raise awareness of and develop access to adequate tools and resources for the oncology community to deliver well-coordinated care to patients treated with HCT. Lastly, we set the stage for policy changes around appropriate reimbursement to cover all aspects of care coordination and generate successful buy-in from all stakeholders.

Introduction

Care coordination is a growing focus of health care reform efforts to address fragmentation of the health care delivery system leading to poor-quality care with system inefficiencies.1 It is defined as “deliberate organization of patient care activities between two or more participants (including the patient) involved in a patient’s care to facilitate the appropriate delivery of health care services.”2(p41) Possible benefits of well-coordinated care include improved clinical efficiency with reduced waste, such as fewer medication errors, reduction in unnecessary or repetitive tests and services, and fewer emergency room visits and preventable hospital readmissions.3 In addition, novel approaches to care coordination could lead to innovative ways to manage patient referrals and care transitions while keeping patients and families informed. Patients with multiple chronic medical conditions requiring multidisciplinary care, many medications, or frequent transitions from 1 care setting to another are challenges in the delivery of high-quality coordinated patient care. Incidentally, the costs involved in caring for this group constitute a major proportion of the overall health care expenditure.4 Recent developments such as the oncology patient-centered medical home have focused on improving health care delivery for patients with cancer by increasing coordination, minimizing variation, and reducing overutilization to enhance patient experiences and satisfaction, but they have targeted only patients undergoing chemotherapy.5,6

Use of hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) as a treatment modality for many hematologic malignancies and some solid tumors has continued to grow, highlighting areas for further development and unmet need.7-10 In this article, we review coordination problems unique to patients treated with HCT and identify pertinent stakeholders throughout the continuum of care. We describe the existing care coordination models and propose a framework for a coordination model for HCT using components from existing models to appropriately meet the complex needs of these patients. Finally, we review challenges to implementing the new model and conclude by describing the metrics to assess its effectiveness. The approach we describe may be applicable to other areas in hematology/oncology in the design and evaluation of care coordination interventions and programs, because the underlying concepts and operational processes are similar.

Methods

A working group of HCT clinicians, transplantation program medical directors and administrators, and representatives from large national payers was convened and facilitated by the National Marrow Donor Program/Be The Match in 2016. The working group met via conference calls and WebEx over a 6-month period to develop an understanding of care coordination issues and potential solutions specifically focused on the experience of the patient treated with HCT. A literature search of existing care coordination models across all clinical specialties was performed to identify components applicable to HCT.

This article summarizes the efforts of the working group in describing components of an ideal care coordination framework for patients treated with HCT and provides suggestions for implementation despite perceived barriers by transplantation programs and hematology/oncology practices.

Coordination issues and stakeholders in HCT

Patients treated with HCT face many challenges, such as multiple levels of transition of care, the requirement for extensive caregiver support and communication, psychosocial and financial stress, geographic displacement from home to receive specialized care at the transplantation center, the need for efficient posttransplantation clinical care, and the need for optimal provider-to-provider communication. Difficulty in accessing and navigating the health care system across providers and institutions, a lack of timely education or information available to the patient to help in decision making, and a need for emotional and logistical support throughout this process are some other barriers to care coordination experienced by this population.

Manageable comorbidity profile, optimal disease risk, availability of a suitable donor, good social support, and secure financial background should be considered prerequisites for a successful HCT.11 This is because socioeconomically disadvantaged patients, those without adequate social support, those with extensive comorbidities or a low level of health literacy, rural residents, and elderly patients are at high risk for poor care coordination after HCT and experience a high likelihood of poor outcomes.12-14 Another vulnerable group in regard to care coordination is the pediatric and adolescent and young adult population, for whom special care needs, knowledge gaps, and a need for continued access to care during transition from pediatric to adult providers pose challenges.

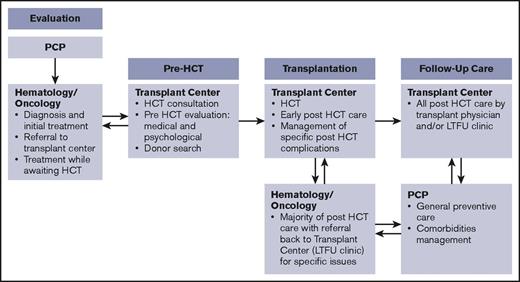

Primary stakeholders in this process are patients and their caregivers and families. In addition to transplantation center staff (clinicians, social workers, case managers, and financial counselors), other important stakeholders include primary care physicians, the hematologists/oncologists who are the main referring providers, and other subspecialists, such as those in behavioral health, home care, and pharmacy. Payers and payer case managers and advocacy and support organizations are also critical in addressing some of the barriers in care coordination. The working group identified involvement of various stakeholders for coordination across different phases of the transplantation continuum.15 Figure 1 illustrates a simplified version of the timeline for a patient treated with HCT going through these 4 phases, highlighting the role of 3 main stakeholders (the primary care physician, hematologist/oncologist, and transplantation center). Figure 2 identifies the main issues in coordination and the roles and responsibilities of all stakeholders during each phase.

Phases in the HCT continuum and involvement of main stakeholders. Follow-up care can take place at the transplantation center for a few patients, but most other patients return to their referring hematology/oncology providers. LTFU, long-term follow-up; PCP, primary care provider.

Phases in the HCT continuum and involvement of main stakeholders. Follow-up care can take place at the transplantation center for a few patients, but most other patients return to their referring hematology/oncology providers. LTFU, long-term follow-up; PCP, primary care provider.

Issues and stakeholders in care coordination. Evaluation (A), pretransplantation (B), transplantation event (C), and follow-up care (D). AD, administrator; C, consulting; CC, care coordinator; CG, caregiver; CP, consulting provider; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; Hem/Onc, hematologist/oncologist; I, informed; P, payer; PCM, payer case manager; Pt, patient; R, responsible; SSI, supplemental security income; SW, social worker; TC, transplant center; TFC, transplantation financial coordinator; TP, transplantation physician.

Issues and stakeholders in care coordination. Evaluation (A), pretransplantation (B), transplantation event (C), and follow-up care (D). AD, administrator; C, consulting; CC, care coordinator; CG, caregiver; CP, consulting provider; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; Hem/Onc, hematologist/oncologist; I, informed; P, payer; PCM, payer case manager; Pt, patient; R, responsible; SSI, supplemental security income; SW, social worker; TC, transplant center; TFC, transplantation financial coordinator; TP, transplantation physician.

Phase 1: evaluation.

This phase begins when a patient is diagnosed with a disease for which transplantation is a treatment option and ends with a transplantation consultation.

Phase 2: pretransplantation.

This phase begins after a transplantation consultation and includes determination of optimal candidacy from medical and psychosocial perspectives. The patient transitions to the transplantation phase at the time of transplantation workup. Effective communication among the key participants and delivery of information to the patient are the 2 main issues in this phase.

Phase 3: transplantation event.

The patient receives therapy in the inpatient or outpatient setting during the transplantation phase. Coordination issues during this phase revolve around clinical, emotional, and social support for the patient and preparation for transition of care. Traditionally, this phase ranges from 30 to 120 days after transplantation.

Phase 4: follow-up care.

The posttransplantation phase is the most complex phase in terms of coordination, because it is the time of greatest transition for the patient, moving from full support at the transplantation center to his or her community hematologist/oncologist, with periodic visits to the transplantation center. This is also the phase where there is the most variation in the existing care models for follow-up care, depending on patient factors (insurance, proximity to transplantation center, clinical status) and infrastructure of the transplantation center (whether there is continuity of care or periodic long-term follow-up).

Existing care coordination models

Care coordination has been identified as 1 of 6 national priorities for health care in the National Strategy for Quality Improvement in Health Care.16 Various models have been developed and implemented in different areas and settings of medicine before and since the advent of the Affordable Care Act. Table 1 summarizes these models. In addition, the Healthcare Delivery Working Group from the National Institutes of Health Blood and Marrow Transplant Late Effects Consensus Conference has also recently identified research gaps and described elements of an ideal health care delivery model for HCT survivors.16 Finally, the comprehensive agenda around survivorship care developed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology to assist the oncology community in the delivery of comprehensive, coordinated posttreatment care to all cancer survivors helps provide valuable guidance in the coordination of care for HCT survivors.17

The common themes in these patient-centered models are use of a patient navigator or care coordinator for support, innovative ways to deliver care and communicate, including use of technology, patient education on and engagement in the care, and supportive reimbursement policies.18-24 Although these models are at different stages in terms of development and execution at this time, all will continue to evolve with ongoing changes in technology dissemination, the health care delivery system, and reimbursement policies.

Care coordination model for HCT

The elements of a successful care coordination model for HCT include the defining and accepting of accountability and responsibility by providers, patient and provider education, early referrals, psychosocial support, identification of a key contact person, community partnerships, frequent needs assessments, and effective communication among stakeholders at all time points, with use of health care information technology and with adequate reimbursements for these services. Some of the preferred components of this proposed framework are as follows:

Patient navigator: The main aims of implementing a navigation process are to assist and anticipate the complexities and barriers of health care systems and provide culturally targeted education and psychosocial support to help improve the quality of life of patients. Multiple studies have examined the benefits of a nurse navigator, with some reporting positive impacts on patient satisfaction and quality of life, a decrease in number of disparities, and lower rates of hospitalization.19,25 In the case of HCT, a navigator is especially attractive because of the multiple transitions from diagnosis to post-HCT phases. Currently, multiple individuals perform this role or parts of it at different time points along the continuum of HCT care, such as the pre-HCT coordinator, social worker, and payer case manager. However, this is not continued throughout the process and is not uniform across centers or payer types, because of lack of definitive policies and reimbursement methods. In assigning a patient navigator to a patient receiving a transplant, the overlap between the patient navigator’s role and that of other support services, such as social workers, case managers, community outreach workers, and patient advocates, must be considered. The choice between a lay versus professional navigator is also important and may depend on the reimbursement policies and infrastructure of transplantation programs.

Telemedicine: Studies have shown that the use of telemedicine to monitor patients requiring chronic care patients or to allow specialists to provide care to patients over a large geographic region can improve care.20,23 Both the Veterans Affairs model and virtual integrated practice model have demonstrated successfully that various communication technologies can bring geographically dispersed team members together virtually to extend care beyond the traditional visits to brick-and-mortar clinics.21,22 A recent analysis from a large transplantation center showed no impact of distance from the transplantation center or rural/urban residence on clinical outcomes, and this was felt to be in part a result of the use of telemedicine strategies for delivering post-HCT care.26 Use of telemedicine as part of dedicated long-term follow-up programs may also contribute to better outcomes in patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease.27,28 Some transplantation programs are working toward developing additional resources in this area, but a wider application could help with coordination of post-HCT care, with benefits for a larger population. The provision of telehealth could help lessen patient burden through reduction of travel and lodging costs and elimination of the need to miss work because of frequent visits to the transplantation center or other providers.

Survivorship clinics: The ongoing efforts to improve the care for survivors have indicated that there is a continued need for the development of sustainable, cost-effective care models that can help improve health and quality of life for cancer and HCT survivors.29,30 Most transplantation centers lack the resources and infrastructure to provide survivorship care.29,31 HCT is mostly limited to academic centers, and hence, shared care models would need to link academic centers with community-based practices, especially for patients who transition out from the transplantation center for ongoing care needs. A partnership between a transplantation center and local health care system would use a trained HCT coordinator to act as the point person for a patient’s post-HCT care, while maintaining the ability to loop in the transplantation team as needed.

Self-management support and educational interventions: The success of any care coordination model is dependent on patient self-management. Tailored educational interventions to deliver information and support to patients and their caregivers could help in developing self-efficacy, behavior change, and enhanced patient understanding. In general, the transplantation community has done well in this area through extensive educational materials that are provided to patients and families at the beginning of this process. Many educational materials in a variety of languages are available through the National Marrow Donor Program/Be The Match and patient advocacy organizations. Ensuring that all care providers and staff are aware of the available materials and use them to reinforce verbal education throughout the process is vital. If necessary, interpreters should be engaged to participate in patient visits. Resources should be used to enable care teams to become more culturally competent within the context of an increasingly diverse population.32 Peer-to-peer programs established by several organizations provide patients with support from others who have been through the same or similar treatments. An innovative study is examining Internet-based survivorship care for meeting psychoeducational, information, and resource needs of patients treated with HCT.33 Evidence for use of social media as a tool to improve health communication, especially in the adolescent and young adult population, is emerging, but information from these platforms needs to be monitored for quality and reliability, while maintaining users’ confidentiality and privacy.34 Efforts to increase knowledge need to be directed not only at patients but also at health care providers, especially the hematologists/oncologists who resume post-HCT care for a majority of patients, as shown in Figure 1. Additional curriculum items pertaining to transplantation survivorship during hematology/oncology fellowship, continuing medical education activities (organized by professional societies) to increase knowledge about management of physical and psychosocial complications of HCT, and increased use of treatment summaries and survivorship care plans may help promote a shared-care model for post-HCT care.

Standardization: Standardization of treatment protocols based on evidence-based guidelines can inform the development of care pathways, standardized data collection and referral forms, and patient-oriented information such as patient instructions. Also, collection of patient-reported outcomes using standardized tools can be integrated into the electronic medical record system to help improve communication and visit planning. Professional societies such as the American Society of Clinical Oncology, American Society of Hematology, and American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation play an important role in creating resources for improving standardization of care to achieve better patient outcomes and increase safety. For example, in response to the American College of Physicians Pediatric to Adult Care Transition Initiative, the American Society of Hematology has released a toolkit for hematologists and their patients to ease the transition between pediatric and adult care, traditionally considered an area lacking optimum coordination of care.35

Psychosocial and financial support: In addition to educational materials and peer-connect programs and support provided through transplantation programs, it is essential to develop resources for psychological support before, during, and after HCT for patients and caregivers. Financial burden resulting from HCT is emerging as an important challenge for these patients.36-38 An HCT financial assessment performed by the financial coordinator of the transplantation center that considers the patient’s primary and secondary insurance and prescription coverage and estimates the patient’s out-of-pocket costs (medications, travel, and lodging) can help educate a patient and his or her family on the expected economic burden of transplantation.

Challenges and limitations

Challenges exist to implementation of the model proposed here. Indeed, any HCT care coordination model that aims to improve quality of care and decrease costs requires buy-in and resource support from all stakeholders to be successful. Alignment of payment policies to support delivery of well-coordinated care is a major limitation. Although Affordable Care Act initiatives have encouraged the provision of coordinated care, they have mostly focused on primary care. In the absence of adequate reimbursement for components of this framework, it may be impossible to improve the uptake of care coordination approaches at the different points throughout the transplantation continuum, such as telemedicine services or integration of psychosocial care and educational efforts with routine clinical care. Also, there is huge variation not only in the patient population, including clinical and sociodemographic profiles, but also in the capacities, infrastructures, organizational commitment, and available resources of the practices and transplantation centers that care for patients pre- and post-HCT.26 Each patient treated with HCT, provider, and payer has unique needs and capacities (Table 2).

Recommendations for individual centers and practices

We have proposed framework components but acknowledge that it will be difficult to create a one-size-fits-all model. It may not be possible for individual hematology/oncology practices and/or transplantation centers to apply all the listed components at 1 time. However, we have provided an exhaustive list of interventions for coordination issues and suggestions for assignment of stakeholder responsibility. There is a need for the individual practices and centers to conduct thorough needs assessments for issues around care coordination and availability of optimal resources to address those issues at their individual levels. There may be differences in care coordination gaps and availability of resources, so it is highly likely that the components of the framework will have to be integrated sequentially rather than all at once at the individual practice or transplantation center level. The working group is also developing a toolkit, which may be used as a resource by relevant stakeholders, depending on their follow-up practices and available resources, to help address issues around care coordination for patients treated with HCT.

Metrics to assess effectiveness

Evaluation is vital to the success of any program. Identifying the measures for judging effectiveness of a care coordination model up front is as important as developing and implementing the model. The benchmarking aspect of a model can help provide information to compare providers and centers. These metrics can serve as the basis of establishing the benefits of care coordination. Successful care coordination as reflected by these measures will be important to advance them further by ensuring incentives from payers for quality, value, and outcomes in the delivery of care.

Different perspectives may be used to measure success in coordinating care effectively and efficiently.39 The patient perspective would include measuring patient experience, change in health behavior or knowledge, patient satisfaction with care, and reduction in disruptions of daily life. Integration of these patient-reported measures into the electronic medical record could help in assessing the effectiveness of care coordination in the long term during the care delivery itself. This would, however, require extensive time, effort, and commitment from all stakeholders, including the electronic medical record vendors.

An audit of a case management system that examines the ratio of number of care coordinators to patients for whom they care would yield information from a health care professional and institution perspective. A system-level perspective could examine changes in health care utilization (hospital admissions, emergency room visits, provider visits) and costs using institutional, registry, or administrative claims data as metrics to measure the success of a care coordination program. However, cost containment and reduction in health care utilization cannot be the sole measures for effectiveness of care coordination; more emphasis needs to be placed on patient safety and experiences throughout the continuum.40

Conclusion

A focus on the delivery of high-quality coordinated care through accountable care organizations, community health teams, and medical homes is a major component of the Affordable Care Act and is one of the standards for many accrediting agencies. It is likely that, in the future, more stringent accreditation policies may arise that will require structures and processes in place to help provide well-coordinated care to patients both before and after HCT.

We have provided broad approaches and specific steps that can be used by different stakeholders to help change the landscape of care delivery for patients requiring HCT. The joint efforts of various stakeholders in developing this framework will help in reaching our goal of the delivery of comprehensive, coordinated care to all patients treated with HCT. We hope to convince policymakers that access to adequate tools, resources, and knowledge to implement such a model and appropriate reimbursement to cover all aspects of care for patients treated with HCT can help ensure the success of this medically complicated, resource-intensive endeavor.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following individuals for their thoughtful and committed participation in a series of meetings that led to the creation of this report: Michael Boo, Ruth Brentari, Allan Chernov, Stephanie Farnia, and Krishna Komanduri. The authors also thank Alicia Silver, Kate Houg, and Kristen Bostrom of the National Marrow Donor Program for their assistance with this project.

Authorship

Contribution: N.K., P.M., K.E., and N.S.M. designed the review; N.K., P.M., and K.E. conducted the literature search and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; and all other authors offered critical review of the paper and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: P.M., A.B., and C.F.L. are employed by for-profit companies (Anthem Inc., Optum, and HCA-Sarah Cannon, respectively) and hold stock/ownership interests. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Nandita Khera, Mayo Clinic, 5777 E Mayo Blvd, Phoenix, AZ 85054; e-mail: khera.nandita@mayo.edu.