Key Points

In older and/or frail patients with CLL, treatment with acalabrutinib is highly efficacious and can improve underlying frailty.

No unexpected safety signals occurred, with infections accounting for most of high-grade AEs and 3 of 5 deaths.

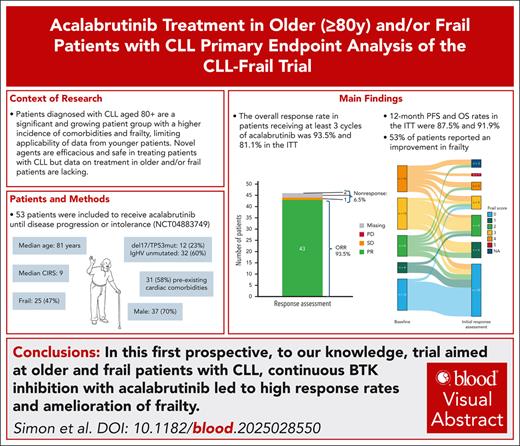

Visual Abstract

Because frail patients and patients aged ≥80 years with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) are still underrepresented in clinical trials, the CLL-Frail trial aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of acalabrutinib in these patients. The primary end point was the overall response rate (ORR) after 6 cycles of treatment to test the null hypothesis of ORR ≤65%. Fifty-three patients were included in the trial, and 34 patients are still on therapy. Adverse events (AEs) were the most frequent reason for early discontinuation (10 patients), whereas 5 patients stopped treatment because of death. Median age was 81 years, and 47.2% of patients were frail. The ORR for the 46 patients receiving ≥3 cycles of treatment was 93.5% (95% confidence interval, 82.1-98.6) meeting the primary end point of this trial (P < .001). The estimated 12-month progression-free and overall survival rates were 93.3% and 95.7%, respectively, after a median follow-up of 19 months. 53.5% of patients reported an improvement in their self-perceived frailty. Although all patients experienced AEs, and severe (Common Terminology Criteria of ≥3) events were reported in 63.5% of patients, there were no events of severe bleeding and atrial fibrillation was rare (2 cases of Common Terminology Criteria Grades 2 and 3). Five patients died, of which 4 deaths happened during or <28 days after treatment. Infections/COVID-19 were the cause of death in 3 cases. To our knowledge, this is the first prospective trial in older and/or frail patients with CLL demonstrating a high efficacy and safe treatment with acalabrutinib monotherapy. This trial was registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov as #NCT04883749.

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a disease primarily affecting older patients, with a median age at diagnosis of 72 years, and >60% of patients diagnosed at age >65 years.1 Thus, an increasing number of patients will surpass the age of 80 years after initial CLL treatment, whereas ∼20% of patients receive their first diagnosis of the disease above this age threshold.2 With octogenarians being one of the fastest growing age groups in the United States,3 health care providers will potentially face a significant number of patients diagnosed with CLL aged ≥80 years in the near future.

Continuous treatment with Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors (BTKis) is well established in first-line and relapse therapy for CLL,4-6 and remains one of the mainstays of current treatment approaches, especially in patients with high-risk disease characteristics.7,8 Ibrutinib, as the first approved BTKi, was, however, associated with an increased risk of cardiac side effects, limiting its use especially in patients with preexisting comorbidities.9 Second-generation BTKis such as acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib were subsequently shown to have a superior tolerability with at least sustained efficacy.10,11

However, data on BTKi therapy in older patients aged >80 years are scarce. Large-scale randomized trials that led to the drug approval in the first-line therapy setting such as the Resonate-2, ELEVATE-TN, and SEQUOIA trials all reported median ages of 71, 70, and 70 years, respectively, limiting their applicability in the guidance of treatment in patients aged ≥80 years.4-6

Fitness within clinical trials in CLL and hematology is often assessed by the physician via the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group or Karnofsky performance index scores based on the perceived abilities of the patient. However, patients of advanced age are also at an increased risk of comorbidities, polypharmacy, cachexia, and a loss of physiological reserve, commonly referred to as frailty. Frailty as a symptom complex, usually defined by either Fried’s phenotype criteria12 or Rockwood’s accumulated deficits model,13 often overlaps with symptoms of malignant diseases,14 and is well known as a factor with impact on treatment tolerability, efficacy, and overall survival (OS).15,16 Yet, it is rarely assessed in large-scale randomized trials, often due to operational reasons, as comprehensive geriatric assessments are time consuming for both patients and physicians. The Fatigue, Resistance, Ambulation, Ilness and weight Loss (FRAIL) scale score is a 5-item questionnaire filled out by patients and has been shown to correlate with Fried’s frailty phenotype.17,18

The CLL-Frail trial aimed to determine the efficacy and safety of acalabrutinib monotherapy in older and/or frail patients as defined by the FRAIL scale score.

Methods

Study design and participants

The CLL-Frail trial is an ongoing, investigator-initiated, international, multicenter phase 2 trial conducted by the German CLL Study Group. The trial enrolled patients with CLL requiring treatment according to international workshop on CLL 2018 criteria.19 A maximum of 1 previous therapy was allowed, excluding a previous therapy with acalabrutinib or disease refractory to previous BTK inhibition. Eligible patients had to be either aged ≥80 years or considered frail according to the FRAIL scale score. The FRAIL scale score determines frailty via a self-assessment questionnaire, in which each positive answer results in 1 point (supplemental Material, available on the Blood website), with any score of ≥3 considered frail. There was no upper age or comorbidity boundary, measured per cumulative illness rating scale (CIRS) score. Patients had to have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score of ≤3. To account for an increasing number of fit patients with CLL aged ≥80 years, in whom numerical age does not equal biological age, the study population aimed to include 50% patients with a FRAIL scale score of ≥3, indicating frailty. The complete list of inclusion/exclusion criteria is available in the study protocol (supplemental Material).

Written informed consent was provided before enrollment, and the trial protocol was approved by the responsible health authorities and institutional review boards. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice Guideline. The CLL-Frail trial is registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier: NCT04883749).

Procedures

Acalabrutinib is administered as a daily oral dosage of 100 mg twice daily, starting on cycle 1, day 1, and continuing until disease progression or intolerance. One cycle of treatment consists of 28 days. Patients will receive treatment for up to 42 cycles or until the last patient included within the trial had reached 24 cycles of treatment, whichever occurs first. After termination of the clinical trial, continuation of acalabrutinib outside of the study is encouraged for patients responding to treatment and with good tolerability of the medication.

To minimize strenuous procedures and study visits in this specific cohort, neither computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging or bone marrow biopsies were mandatory within the trial, but left to the investigator’s discretion, for example in case of unexplained cytopenia. Confirmation of CLL at screening was determined centrally via 8-color flow cytometry. Furthermore, karyotyping, fluorescence in situ hybridization, immunophenotyping, and mutational analysis of immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region gene (IGHV) and TP53 were centrally assessed at the Universities of Ulm and Cologne. BTKi resistance mutation analyses were only performed in patients with previous BTKi therapy or at relapse. Data on race and ethnicity were not collected in this trial.

An initial response assessment was performed after 6 cycles of treatment, at cycle 7, day 1, with the final restaging being performed at cycle 25, day 1, that is, after 24 completed cycles of treatment. Staging procedures followed international workshop on CLL 2018 criteria. At both initial response assessment as well as final restaging, FRAIL scale scoring was/will be repeated via the patient’s own assessment.

An interim safety analysis was performed after the first 30 patients included into the trial had reached the initial response assessment, and was previously reported.20 As no unexpected safety signals occurred, recruitment and study therapy were continued.

The reporting period for adverse events (AEs) lasted from the first dose of study drug until 28 days after the last dose of study treatment or end of the trial, whichever occurs first. Patients were followed up at least once a month during the first 6 months of treatment, after which a de-escalation to 3-monthly visits was possible. In patients with stable disease characteristics after 12 months of observation, visits were mandatory at least once every 6 months. After clinical disease progression, visits were performed at least once a year until the end of the study. AEs were reported according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 5.0) and the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities classification system.

Hypertension, infections with a Common Terminology Criteria (CTC) grade >2, cardiac events, falls, fractures, cognitive impairment/dementia, late-onset (ie, >4 weeks after treatment completion) neutropenia with at least grade 3, second primary malignancies, and elevations in liver biochemistry were considered AEs of particular interest (AEPI). Reporting of AEPIs was required until patients received new CLL treatment or were considered as end of study.

Relatedness of AEs and deaths to study treatment were determined by local investigators.

Outcomes

The primary end point of this trial was the overall response rate (ORR; defined as the rate of patients with complete response or partial response) after 6 completed cycles of treatment with acalabrutinib and was assessed at the initial response assessment at cycle 7 day 1.

Secondary end points reported here were the progression-free survival (PFS; defined as the time from registration to first disease progression or death from any cause), OS (defined as the time from registration to death from any cause), as well as feasibility and safety parameters. Other secondary end points, such as ORR after 24 completed cycles of treatment, event-free survival, duration of response, and time to next treatment, as well as the exploratory end point of health-related quality of life, will be analyzed later when extended follow-up data become available.

Predefined exploratory end points focused on the evaluation of the FRAIL scale score after 6 completed cycles of treatment (ie, assessed at the initial response assessment at cycle 7, day 1) and on subgroup analyses of PFS and OS according to the FRAIL scale score. Additionally, safety was analyzed on an exploratory basis with focus on specific issues raised in this older/frail population with cardiac comorbidities or cardioactive medication and interaction risks in the context of acalabrutinib. Further post hoc exploratory analyses included univariate analyses of potential prognostic factors for PFS (by Cox proportional hazards regression) and for premature treatment discontinuation (by logistic regression).

Statistical analyses

The primary end point analysis of ORR after 6 completed cycles of treatment was done using a 1-sided 1-sample binomial test with an overall significance level of 2.5%. The null hypothesis was ORR ≤65%, with the alternative hypothesis ORR >65%. Because this is, to our knowledge, the first prospective trial aimed specifically at older and frail patients with CLL, the threshold was determined according to real-world data, such as an analysis by Michallet et al showing a response rate of 69% in older, mostly relapsed patients treated with ibrutinib,21 and published trial data from a pooled analysis of the German CLL Study Group on patients aged ≥80 years with an ORR of 73% for frontline therapy with targeted agents (mostly venetoclax).22 Due to a known comparable efficacy with an improved tolerability of acalabrutinib over ibrutinib,23 the study treatment was expected to increase the ORR compared with the aforementioned published data to at least 85%. To achieve statistical significance with a power of 90%, a sample size of 49 patients was required. The 95% confidence interval (CI) of the primary end point was calculated according to the Clopper-Pearson method, and time-to-event analyses were performed using the Kaplan-Meier methodology.

Per protocol, all patients who received at least 3 complete cycles of treatment, including at least 1 administered dose in cycle 4, comprised the full analysis set (FAS), and were considered for the analyses of primary and secondary efficacy end points. To maintain the power of 90% for achieving statistical significance, patients with an early dropout before reaching the first administered dose in cycle 4 were replaced. To account for selection bias possibly introduced by this approach, predefined sensitivity analyses on efficacy were performed on the intention-to-treat (ITT) population, which contained all registered patients regardless of the number of administered cycles. The safety population comprised all patients who received at least 1 dose of study drug and was considered for safety analyses.

The data cutoff of this primary end point analysis was 15 January 2024.

Analyses were performed using SPSS (version 28.0.1.0) and R (version 4.0.3).

Results

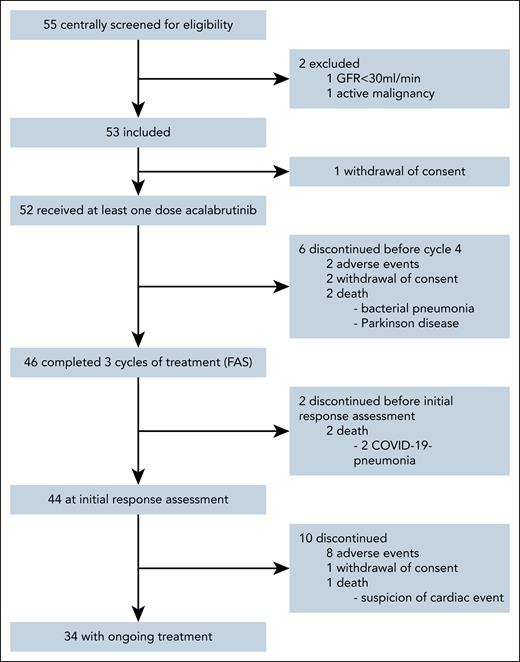

Between 1 June 2021 and 6 July 2023, 55 patients were screened for eligibility from a total of 20 participating sites in Germany and Austria. Fifty-three patients were included into the trial (ITT population) with a median observation time of 17.7 months (interquartile range, 13.4-22.3). One patient withdrew consent before receiving study medication and was excluded from the safety population, which consists of 52 patients. Six patients (12%) discontinued therapy before reaching the first administered dose in cycle 4, leading to 46 patients with at least 3 completed cycles of therapy as defined per protocol as FAS (Figure 1, CONSORT).

Within the FAS, the median age was 81 years (range, 54-88), and 48% of patients were considered frail with a FRAIL scale score of ≥3. There was a high prevalence of multimorbidity with a median CIRS score of 8 (range, 2-18), and 65% of patients having a score >6, usually considered a cutoff for unfit patients in CLL trials.24 Patients with recorded frailty had a higher degree of comorbidity with a median CIRS score of 9 (range, 2-17), and 80% of patients having a score of >6. Twenty-five patients (54%) had a preexisting cardiac comorbidity according to the CIRS score. Fifteen (33%) and 13 (28%) patients were taking antiplatelet and/or anticoagulation medication as concomitant medication, respectively. Twenty patients (43%) were Binet stage C at study inclusion. Reasons for initiating treatment are summarized in supplemental Table 1. Unmutated IGHV and TP53 aberrations were present in 61% and 22% of patients, respectively. Thirty-three patients (72%) of the study population were treatment naïve. In the previously treated cohort, previous lines of treatment included chemoimmunotherapy in 10 patients (77%), whereas 3 patients (23%) were treated with targeted therapy. Additional baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1, baseline characteristics for the ITT population vs FAS were similar and can be found in supplemental Table 2.

Patient characteristics

| Patient characteristics . | FAS . | |

|---|---|---|

| All patients | 46 | |

| Age (y) | ||

| Mean | 80.3 | |

| Median | 81 | |

| Range | 54-88 | |

| Age (y), n (%) | ||

| <75 | 3 | (6.5) |

| ≥75 and <80 | 12 | (26.1) |

| ≥80 and <85 | 22 | (47.8) |

| ≥85 | 9 | (19.6) |

| Frail scale score, n (%) | ||

| Median | 2 | |

| Not frail (0) | 12 | (26.1) |

| Prefrail (1, 2) | 12 | (26.1) |

| 1 | 4 (8.6) | |

| 2 | 8 (17.4) | |

| Frail (≥3) | 22 | (47.8) |

| 3 | 12 (26.1) | |

| 4 | 10 (21.7) | |

| 5 | 0 | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 13 | (28.3) |

| Male | 33 | (71.7) |

| Previous treatment, n (%) | ||

| Treatment naïve | 33 | (71.7) |

| Relapsed/refractory∗ | 13 | (28.3) |

| Binet stage, n (%) | ||

| A | 16 | (34.8) |

| B | 10 | (21.7) |

| C | 20 | (43.5) |

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 11 | (23.9) |

| 1 | 21 | (45.7) |

| 2 | 11 | (23.9) |

| 3 | 3 | (6.5) |

| Total CIRS score | ||

| Mean | 8.1 | |

| Median | 8 | |

| Range | 2-18 | |

| Total CIRS score, n (%) | ||

| ≤6 | 16 | (34.8) |

| >6 | 30 | (65.2) |

| Creatinine clearance (according to Cockcroft-Gault), mL/min | ||

| Mean | 61.5 | |

| Median | 58.9 | |

| Range | 28.9-102.8 | |

| Creatinine clearance, n (%) | ||

| <70 | 34 | (73.9) |

| ≥70 | 12 | (26.1) |

| Cytogenetic groups hierarchy (according to Döhner et al41), n (%) | ||

| Deletion 17p | 8 | (17.4) |

| Deletion 11q | 14 | (30.4) |

| Trisomy 12 | 2 | (4.3) |

| No abnormalities | 7 | (15.2) |

| Deletion 13q | 15 | (32.6) |

| TP53 status, n (%) | ||

| None | 36 | (78.3) |

| Deletion 17p and/or mutated | 10 | (21.7) |

| IGHV mutation status, n (%) | ||

| Unmutated | 28 | (60.9) |

| Mutated | 18 | (39.1) |

| Complex karyotype, n (%) | ||

| Noncomplex (<3 aberrations) | 39 | (84.8) |

| Complex | 7 | (15.2) |

| CLL-IPI risk group, n (%) | ||

| Low | 1 | (2.2) |

| Intermediate | 3 | (6.5) |

| High | 34 | (73.9) |

| Very high | 8 | (17.4) |

| Patient characteristics . | FAS . | |

|---|---|---|

| All patients | 46 | |

| Age (y) | ||

| Mean | 80.3 | |

| Median | 81 | |

| Range | 54-88 | |

| Age (y), n (%) | ||

| <75 | 3 | (6.5) |

| ≥75 and <80 | 12 | (26.1) |

| ≥80 and <85 | 22 | (47.8) |

| ≥85 | 9 | (19.6) |

| Frail scale score, n (%) | ||

| Median | 2 | |

| Not frail (0) | 12 | (26.1) |

| Prefrail (1, 2) | 12 | (26.1) |

| 1 | 4 (8.6) | |

| 2 | 8 (17.4) | |

| Frail (≥3) | 22 | (47.8) |

| 3 | 12 (26.1) | |

| 4 | 10 (21.7) | |

| 5 | 0 | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 13 | (28.3) |

| Male | 33 | (71.7) |

| Previous treatment, n (%) | ||

| Treatment naïve | 33 | (71.7) |

| Relapsed/refractory∗ | 13 | (28.3) |

| Binet stage, n (%) | ||

| A | 16 | (34.8) |

| B | 10 | (21.7) |

| C | 20 | (43.5) |

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 11 | (23.9) |

| 1 | 21 | (45.7) |

| 2 | 11 | (23.9) |

| 3 | 3 | (6.5) |

| Total CIRS score | ||

| Mean | 8.1 | |

| Median | 8 | |

| Range | 2-18 | |

| Total CIRS score, n (%) | ||

| ≤6 | 16 | (34.8) |

| >6 | 30 | (65.2) |

| Creatinine clearance (according to Cockcroft-Gault), mL/min | ||

| Mean | 61.5 | |

| Median | 58.9 | |

| Range | 28.9-102.8 | |

| Creatinine clearance, n (%) | ||

| <70 | 34 | (73.9) |

| ≥70 | 12 | (26.1) |

| Cytogenetic groups hierarchy (according to Döhner et al41), n (%) | ||

| Deletion 17p | 8 | (17.4) |

| Deletion 11q | 14 | (30.4) |

| Trisomy 12 | 2 | (4.3) |

| No abnormalities | 7 | (15.2) |

| Deletion 13q | 15 | (32.6) |

| TP53 status, n (%) | ||

| None | 36 | (78.3) |

| Deletion 17p and/or mutated | 10 | (21.7) |

| IGHV mutation status, n (%) | ||

| Unmutated | 28 | (60.9) |

| Mutated | 18 | (39.1) |

| Complex karyotype, n (%) | ||

| Noncomplex (<3 aberrations) | 39 | (84.8) |

| Complex | 7 | (15.2) |

| CLL-IPI risk group, n (%) | ||

| Low | 1 | (2.2) |

| Intermediate | 3 | (6.5) |

| High | 34 | (73.9) |

| Very high | 8 | (17.4) |

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; IGHV, immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region; IPI, international prognostic index.

All relapsed/refractory patients had only a single previous treatment.

Patients with a self-reported FRAIL scale score of ≥3 were younger, more likely to be female, and had better kidney function compared with nonfrail patients (supplemental Table 3).

At the time of the analysis, 34 patients of the safety population (65%) remained on therapy, whereas 18 patients (35%) stopped treatment. Reasons for premature discontinuation were AEs in 10 (56%), death in 5 (28%), and withdrawn consent in 3 (17%) patients, respectively (Figure 1). Twenty-five patients (48%) had at least 1 dose adjustment due to any reason, including 22 (42%) due to AEs. Most of these were temporary, with a median dose intensity until cycle 7, day 1, of 96% (interquartile range, 88%-100%). Sixteen frail patients (74%) remained on therapy vs 18 patients not considered frail (64%), showing a similar number of administered treatment cycles in both groups (supplemental Table 4).

Within the FAS, 43 of 46 patients achieved a partial response at cycle 7, day 1, corresponding to an ORR of 93.5% (95% CI, 82.1-98.6) meeting the primary end point of the trial (P < .001; supplemental Figure 3). One patient (FRAIL score 4, aged 77 years) had stable disease (2%), and 2 patients (both FRAIL score 4, and aged 85 years) had missing response assessments (4%) because of fatal COVID-19 infections before initial response assessment. Nine patients met the clinical criteria for complete response but did not have confirmatory bone marrow biopsies or computed tomography scan as these were not mandatory; therefore, no patient achieved a complete response at the time point of analysis. In the ITT population, the ORR was 81.1% (95% CI, 68.0-90.6), with 7 additional patients not part of the FAS without response assessments considered as nonresponders.

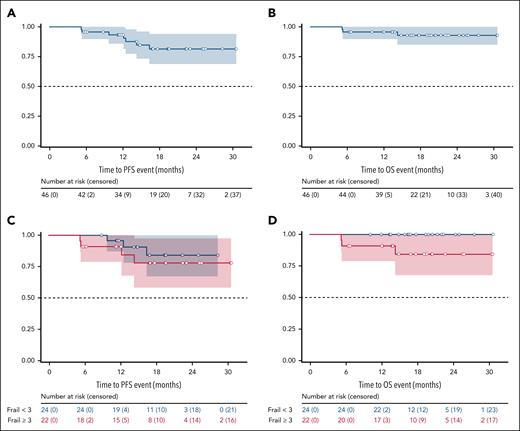

In the FAS, 4 progressive diseases were reported, none of which was Richter transformations and all in patients who had discontinued acalabrutinib (supplemental Figure 1). The median PFS was not reached, and the estimated 12-month PFS rate was 93.3% (95% CI, 85.9-100; Figure 2A). One patient with disease progression required subsequent therapy and was treated with a combination of chlorambucil and obinutuzumab. Median OS was not reached, and the estimated 12-month OS rate was 95.7% (95% CI, 89.8-100; Figure 2B). The estimated 12-month PFS and OS rates in frail patients were similar compared with nonfrail patients, with 90.9% (95% CI, 78.9-100) vs 95.7% (95% CI, 87.3-100) and 90.9 (95% CI, 78.9-100) vs 100%, respectively.

Progression-free and overall survival. Kaplan-Meier curves for PFS (A), OS (B) for the FAS. (C-D) PFS and OS according to frail (red) and nonfrail (blue) status, respectively.

Progression-free and overall survival. Kaplan-Meier curves for PFS (A), OS (B) for the FAS. (C-D) PFS and OS according to frail (red) and nonfrail (blue) status, respectively.

Predefined sensitivity analyses of PFS and OS in the ITT population showed similar survival trajectories as in the FAS, with a total of 5 progressive diseases in the ITT population, median PFS and OS likewise not reached, and estimated 12-month PFS and OS rates of 87.5% (95% CI, 78.1-96.9) and 91.9% (95% CI, 84.3-99.5), respectively (supplemental Figure 2). In univariate analyses, age ≥80 years and relapsed/refractory pretreatment status were associated with impaired PFS. These were, however, not associated with an early treatment cessation (supplemental Figures 4 and 5).

Overall, 5 deaths were recorded in the ITT population. Causes of death were infections in 3 cases (1 bacterial pneumonia and 2 COVID-19 pneumonias, the latter both in vaccinated individuals) and concomitant disease in 1 case. There was 1 fatal severe AE (SAE) termed suspicion of cardiac event, in a patient with sudden death at home and known first-grade atrioventricular block and right bundle branch block.

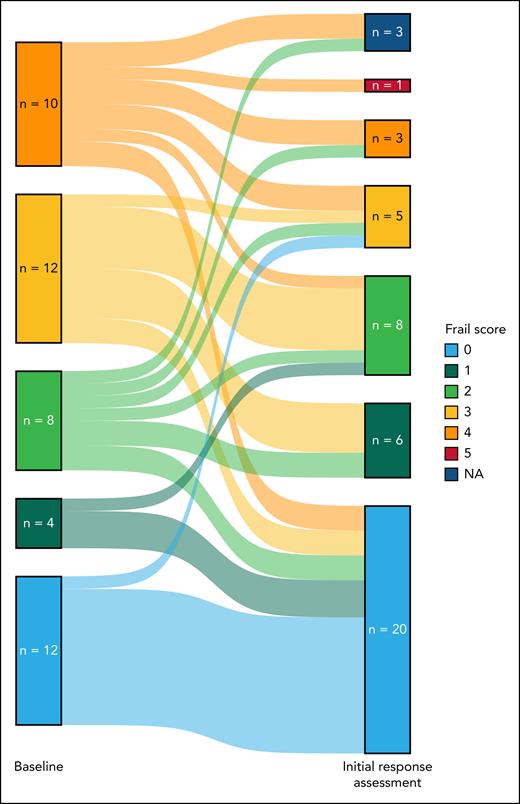

Notably, 23 of 43 (53%; 3 missing results) FAS patients had an improvement in their FRAIL scale scores, with 9 (21%) patients considered frail at month 6, compared with 22 (48%) at screening (Table 2; Figure 3).

Crosstable of FRAIL scale score results at baseline and initial response assessment (cycle 7, day 1) for the FAS

|

|

Two of these patients died before reaching the initial response assessment, 1 patient (with documented partial response at the initial response assessment) had no available data for the FRAIL scale score at the initial response assessment. Color legend: green, FRAIL scale score improvement from baseline; yellow, no change from baseline/missing; orange, worse than baseline.

Sankey plot of self-reported FRAIL scale scores at baseline and initial response assessment in the FAS. NA, not assessed.

Sankey plot of self-reported FRAIL scale scores at baseline and initial response assessment in the FAS. NA, not assessed.

All 52 patients of the safety population (100%) experienced an AE, with CTC° ≥3 AEs being reported in 63% of the patients. Forty-nine (94%) patients experienced an AE for which treatment/supportive care was necessary, and almost half of the patients (46%) received inpatient therapy for an AE. On a case basis, this corresponds to 40 of 485 AEs (8%) requiring inpatient therapy, with a median of 9 days (interquartile range, 5-15) until the resolution of these events. AEs leading to treatment discontinuation are reported in the supplemental Table 6.

The most common AEs were COVID-19 in 21 patients (40%) and hematoma in 19 patients (37%), with the most common hematologic AEs being anemia and thrombocytopenia in 9 (17%) and 6 (12%) patients, respectively. The most common CTC° ≥3 AEs were anemia and COVID-19 in 6 patients (12%) each. Other AEs on a patient basis are reported in Table 3.

AEs

| AE . | All grades, n (%) . | Grade ≥3, n (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| 52 (100) . | 33 (63.5) . | |

| COVID-19 | 21 (40.4) | 6 (11.5) |

| Hematoma | 19 (36.5) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 12 (23.1) | 1 (1.9) |

| Anemia | 9 (17.3) | 6 (11.5) |

| Constipation | 9 (17.3) | 0 |

| Headache | 9 (17.3) | 0 |

| Fatigue | 8 (15.4) | 0 |

| Edema peripheral | 8 (15.4) | 0 |

| Contusion | 7 (13.5) | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 6 (11.5) | 1 (1.9) |

| Vertigo | 6 (11.5) | 0 |

| Dehydration | 6 (11.5) | 1 (1.9) |

| Rash | 6 (11.5) | 2 (3.8) |

| Nausea | 6 (11.5) | 0 |

| Cardiac failure | 4 (7.7) | 3 (5.8) |

| Palpitations | 4 (7.7) | 0 |

| Hypertension | 1 (1.9) | 0 |

| Hypertensive crisis | 1 (1.9) | 0 |

| AE . | All grades, n (%) . | Grade ≥3, n (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| 52 (100) . | 33 (63.5) . | |

| COVID-19 | 21 (40.4) | 6 (11.5) |

| Hematoma | 19 (36.5) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 12 (23.1) | 1 (1.9) |

| Anemia | 9 (17.3) | 6 (11.5) |

| Constipation | 9 (17.3) | 0 |

| Headache | 9 (17.3) | 0 |

| Fatigue | 8 (15.4) | 0 |

| Edema peripheral | 8 (15.4) | 0 |

| Contusion | 7 (13.5) | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 6 (11.5) | 1 (1.9) |

| Vertigo | 6 (11.5) | 0 |

| Dehydration | 6 (11.5) | 1 (1.9) |

| Rash | 6 (11.5) | 2 (3.8) |

| Nausea | 6 (11.5) | 0 |

| Cardiac failure | 4 (7.7) | 3 (5.8) |

| Palpitations | 4 (7.7) | 0 |

| Hypertension | 1 (1.9) | 0 |

| Hypertensive crisis | 1 (1.9) | 0 |

Data are presented at the patient level for the safety population (n = 52). Depicted are AEs with an occurrence of ≥10% of all patients, and cardiac AEs with an occurrence of ≥5%.

A total of 40 SAEs occurred in 26 (50%) patients, with COVID-19 being the most common SAE in 5 of 52 patients within the safety population (10%).

Twenty-five percent of patients experienced a cardiac AE of any grade, whereas 5 patients (10%) experienced higher grade (CTC° ≥3) events. Two cases of atrial fibrillation were documented in the 2 patients (4%) with CTC grades 2 and 3, respectively. The most common cardiac AE with CTC grade 3 was cardiac failure in 3 patients (6%), with no patient experiencing a cardiac failure of higher CTC grade. The 3 affected patients were suffering from preexisting heart failure and/or documented heart failure medication. Other cardiac toxicities were reported as AEPIs; the most frequent cases were palpitations (n = 8), cardiac/left ventricular failure (n = 6), and valvular diseases (n = 6). Further cardiac AEPI are listed in supplemental Table 7. Differentiating by cardiac comorbidities prior to treatment initiation, patients with CIRS category heart score <1 point experienced less cardiac toxicities as compared with patients with a heart score ≥1 point (5/22 [23%] vs 8/30 [27%] patients), as well as less severe cardiac toxicities (CTC ≥3; 0 vs 5 [17%]). There was 1 case of grade 1 hypertension and grade 2 hypertensive crisis each in patients with preexisting hypertension. Within the safety population, 69% of patients reported antihypertensive medication at baseline.

Encouragingly, even with a high number of AEs concerning bleeding (all preferred terms including the words hematoma, contusion, hemorrhage, bleeding, epistaxis, or petechiae) with 53 cases (11% of all AEs), there were no cases of a higher grade (CTC° ≥3). For 15 patients taking anticoagulants at study enrollment, there was an increased risk of hematoma compared with patients without these medications (7/15 [47%] vs 12/37 [32%] patients).

There were 8 second primary malignancies reported in 6 patients (12%), all nonmelanoma skin cancers.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective trial aimed specifically at treatment evaluation with the BTKI acalabrutinib in older and/or frail patients with CLL. The primary end point of the trial was met with an ORR of 93.5%, exceeding the predefined threshold of 65%.

While the efficacy of targeted agents in CLL treatment in general is undoubted, their efficacy in older or frail patients is mostly impacted by an inferior tolerability and early treatment discontinuations.25 This was previously shown in the analysis by Michallet et al, with 32% of patients stopping therapy prematurely, of whom only 6% were due to CLL progression,21 and further corroborated in a real-world analysis on treatment with venetoclax in 342 older patients with CLL, in which 42% of patients discontinued therapy early.26

Acalabrutinib was well tolerated in this analysis compared with previous real-world and trial data, with only 15 patients discontinuing therapy early due to AEs or death, acknowledging a notable impact of COVID-19 infections. Nonetheless, AEs were still frequent, with 63% of patients experiencing severe (CTC° ≥3) events and the most common reason for treatment discontinuation. Reassuringly, rates of atrial fibrillation (4%) were lower compared with ibrutinib therapy, with reported rates of 10% to 16%.27,28

Previously published data in second-generation BTKi in younger patients reported 21% any-grade cardiac AEs for zanubrutinib and 17% for acalabrutinib.28,29 With a median observation time of 18 months in the CLL-Frail trial, 25% of patients experienced cardiac AEs. Although being influenced by a high degree of preexisting cardiac diseases and age-related AEs such as valvular diseases, cardiac side effects in older patients under treatment with BTKis remain a concern. Notably, severe cardiac side effects in this trial only occurred in 30 patients with previously existing cardiac conditions, underscoring the need for a thorough risk-benefit assessment prior to treatment initiation.30

Frailty, characterized by heightened vulnerability to stressors, is also influenced by the hematologic malignancy, as the 2 share a significant overlap in symptoms.14 Additionally, frailty is often overlooked in the frameworks of clinical trials, in which assessments such as age or creatinine clearance have traditionally been used.31,32 This limitation is highlighted in this trial, in which patients classified as frail were observed to have younger ages and better kidney function compared with their nonfrail counterparts. Although frailty remains a challenging aspect in both fitness assessment as well as the treatment of geriatric patients, discarding it might lead to overtreatment in some patients who do not tolerate certain agents, as well as undertreatment of patients who are merely impacted by their underlying disease and could benefit from well-designed treatment plans.33,34 In the CLL-Frail study, this is reflected in similar PFS and OS rates for both frail and nonfrail patients. Encouragingly, an improvement in self-reported frailty in 23 of 43 patients (53%) was also shown here through the treatment of the underlying malignant disease, in line with a previous post hoc analysis of 67 patients treated with venetoclax plus obinutuzumab and a median age of 71 years, with the number of patients with 2 or more geriatric impairments decreasing from 61% to 36%.35

Though CLL-Frail is a phase 2 trial providing, to our knowledge, the first prospective data within this age and fitness group, it does not compare to current treatment approaches offering the possibility of time-limited treatment, which might yield better tolerability through reduced exposure, such as combinations of Bcl-2 inhibitors with either CD20 antibodies36 or BTKis.37 Additionally, side effects were common, and a third of patients discontinued therapy during the limited observation time of 18 months, compared with 21% or 14% of younger patients at early readouts in the ELEVATE-TN38 and SEQUOIA6 trials, respectively. Thus, improving tolerability of treatment to further enhance efficacy and patients’ quality of life should be the main goal of subsequent studies. Data on the latter will be reported at the final readout of this trial and further guide decision-making. Finally, future trials should additionally not only implement novel treatment approaches, but also ideally multidisciplinary approaches aimed at supporting older and frail patients according to their limitations associated with aging, which were shown to significantly reduce toxicity in patients treated with chemoimmunotherapy.39,40

In conclusion, although careful patient selection and shared decision-making remain essential, the high response rates and improvement in frailty underscore the remarkable efficacy and feasibility of BTK inhibition with acalabrutinib in this previously underrepresented age group. These findings encourage the use of effective targeted agents also in patients with CLL and advanced age or frailty. Additionally, they should lead to broader inclusion criteria or predefined quotas aimed at this patient cohort in future clinical trials in CLL.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all patients and their families, physicians, and trial staff at the sites for their participation in the study. The authors also thank Christina Paulitschek, Katharina Löhers, and Marina Stockem, who worked as project managers; Ronald D’Brot, Dilara Celik, Henrik Gerwin, Annette Niederhausen, and Michael Verhülsdonk, who worked as data managers; and Christina Rhein, who worked as a safety manager in the CLL-Frail trial; as well as the monitors from the Competence Network Malignant Lymphoma (Kompetenznetz Maligne Lymphome).

M.H. is supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Sonderforschungsbereich 1530, and projects B01 and Z01. The trial was sponsored by the German CLL Study Group, with financial support and study drug provision from AstraZeneca.

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Authorship

Contribution: F.S., B.E., and M.H. were responsible for the conception and design of the study; F.S., R.Ligtvoet., S.R., A.M.-F., M.F., J.S., K.F., and B.E. were responsible for the trial management; F.S., J.-P.B., T.N., J.v.T., R. Liersch, T.G., K.J.-U., M.G., T.W., I.S., D.W., C.Spoer., U.V.-K., M.R., C.Schneider., M.E., T.D., G.C., B.S., J.K., E.T., and S.S. were responsible for recruitment and treatment of patients; F.S., R.Ligtvoet., S.R., and B.E. had access to the raw data; F.S. and B.E. did a central review of all clinical data; C.Schneider., E.T., S.S., and K.-A.K. did the laboratory analyses; R.Ligtvoet. and S.R. performed the statistical analyses; F.S. and B.E. wrote the first draft of the manuscript; and all authors interpreted the data and reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: F.S. reports speakers fee/honoraria from AstraZeneca; travel support from Eli Lilly; and research support (institution) from AstraZeneca. J.-P.B. has served on advisory boards for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, and Janssen; and has received honoraria from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Eli Lilly, and Janssen. T.N. has served on advisory boards; and has received honoraria and travel grants from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Janssen, Eli Lilly, and Roche. J.v.T. has received honoraria from BeiGene, AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Roche, AstraZeneca, and Eli Lilly; reports consulting or advisory roles for BeiGene, AstraZeneca, AbbVie, and Amgen; and has received travel support from Eli Lilly, AbbVie, AstraZeneca, and BeiGene. I.S. reports a consultancy role for AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Janssen, Eli Lilly, and Roche. D.W. has been served on advisory boards for AbbVie, Gilead Sciences, BeiGene, Pierre Fabre, Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD), Janssen, Eli Lilly, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS)/Celgene, Novartis, Amgen, Roche, Pfizer, and Miltenyi; has received research support/research from AbbVie, BMS/Celgene, BeiGene, Pfizer, Novartis, Roche, Incyte, Jazz, and Takeda. C.Schneider. has received honoraria from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Janssen-Cilag, MSD, and Novartis. M.R. has received honoraria from Roche, Janssen Oncology, AstraZeneca, AbbVie, and MSD; reports a consulting or advisory role for AbbVie, Roche, and AstraZeneca; has received research funding from Roche (institution) and AbbVie (institution); and travel support from AstraZeneca and Takeda. J.K. has received honoraria/served on advisory board for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, BMS, Daiichi Sankyo, Incyte, Ipsen, Janssen, Eli Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Oncopeptides, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and Takeda. K.-A.K. has received consultancy fees, speaker bureau fees, and research support from Janssen, Roche, and AbbVie. E.T. declares a consulting or advisory role for Roche, AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, and Janssen; has served on speakers bureau for Roche, AbbVie, Janssen-Cilag, AstraZeneca, and BeiGene; and has received travel support from AbbVie, BeiGene, AstraZeneca, and Janssen. S.S. has received advisory board honoraria, research support, travel support, and speakers’ fees from AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Celgene, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Janssen, Novartis, and Sunesis. S.Ro. has received honoraria from MSD. A.M.-F. reports research funding from AstraZeneca (institution), honoraria from AstraZeneca, and travel support from AbbVie. M.F. has received research funding (institution) from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Janssen, and Roche; and has received honoraria from AbbVie. K.F. has received advisory board honoraria from AbbVie, Roche, and AstraZeneca; has received honoraria from Roche and AstraZeneca; and has received travel support from Roche. V.G. declares consulting or advisory role for AstraZeneca, AbbVie, Janssen, Gilead Sciences, Roche, Bayer, and Berlin-Chemie; speakers’ bureau for AstraZeneca, AbbVie, Janssen, Gilead Sciences, Roche, Novartis, and Heel. M.H. declares institutional research support from AbbVie, Roche, Janssen, AstraZeneca, Gilead Sciences, and BeiGene. B.E. has served on advisory boards for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, MSD, Galapagos, Janssen, and Eli Lilly; has received honoraria from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Eli Lilly, MSD, and Roche; and has received research support/research funding/grants from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Janssen, and Roche. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Florian Simon, German CLL Study Group, Gleueler Str 176-178, 50935 Köln, Germany; email: florian.simon@uk-koeln.de.

References

Author notes

Data can be shared upon request from the corresponding author, Florian Simon (florian.simon@uk-koeln.de).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal