Familial platelet disorder with predisposition to acute myelogenous leukemia (FPD/AML) is an autosomal dominant familial platelet disorder characterized by thrombocytopenia and a propensity to develop AML. Mutation analyses of RUNX1 in 3 families with FPD/AML showing linkage to chromosome 21q22.1 revealed 3 novel heterozygous point mutations (K83E, R135fsX177 (IVS4 + 3delA), and Y260X). Functional investigations of the 7 FPD/AML RUNX1 Runt domain point mutations described to date (2 frameshift, 2 nonsense, and 3 missense mutations) were performed. Consistent with the position of the mutations in the Runt domain at the RUNX1-DNA interface, DNA binding of all mutant RUNX1 proteins was absent or significantly decreased. In general, missense and nonsense RUNX1 proteins retained the ability to heterodimerize with PEBP2β/CBFβ and inhibited transactivation of a reporter gene by wild-type RUNX1. Colocalization of mutant RUNX1 and PEBP2β/CBFβ in the cytoplasm was observed. These results suggest that the sequestration of PEBP2β/CBFβ by mutant RUNX1 may cause the inhibitory effects. While haploinsufficiency of RUNX1causes FPD/AML in some families (deletions and frameshifts), mutant RUNX1 proteins (missense and nonsense) may also inhibit wild-type RUNX1, possibly creating a higher propensity to develop leukemia. This is consistent with the hypothesis that a second mutation has to occur, either in RUNX1 or another gene, to cause leukemia among individuals harboring RUNX1 FPD/AML mutations and that the propensity to acquire these additional mutations is determined, at least partially, by the initial RUNX1 mutation.

Introduction

The most frequent mutations associated with leukemia are recurrent somatic chromosomal translocations or inversions, many of which involve the polyomavirus enhancer-binding protein or core-binding factor transcriptional regulation complex (PEBP2/CBF). Several translocations involve the α subunit of this complex, the RUNX1 gene (also called AML1, CBFα2, or PEBP2αB) on chromosome 21q22.1 (t(8;21), t(3;21), and t(12;21)). Additionally, the β subunit of the complex, PEBP2β also called CBFβ, is disrupted in inv(16)(p13;q22).1 An abundance of evidence points to the existence of genes that predispose to hematologic malignancies. However, large multiple-generation families with hematologic malignancies alone are rare.2 Only 2 loci for familial hematologic malignancies have been identified to date, 1 on chromosome 21q22.13 and the other on 16q22.4 5 These loci contain RUNX1 andPEBP2β/CBFβ, respectively.

Studies of families that demonstrate single-gene inheritance for leukemia predisposition should help to identify the genes and mechanisms involved in the first steps of leukemia development. The autosomal dominant familial platelet disorder (FPD)/AML (acute myelogenous leukemia; Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man no. 601399) is a good model to validate this hypothesis because, in addition to developing thrombocytopenia, patients show a propensity for progression to myelodysplasia and acute myeloid leukemia.6-9 Affected individuals within the same family may present with variable clinical severity at varying ages. FPD/AML was linked to 21q22.1-22.2,3,9 including the region that contains RUNX1, and germline RUNX1 mutations were subsequently identified in 6 pedigrees.10

Heterozygous missense mutations and biallelic nonsense or frameshift mutations in RUNX1 were also identified in sporadic leukemias,11 and other point mutations have been characterized in patients with M0-AML and various myeloid malignancies,12 including some with acquired trisomy and tetrasomy of chromosome 21.13 While missense mutations abolish the DNA binding and transactivation activities of RUNX1, they do not affect heterodimerization with PEBP2β/CBFβ. In addition, these mutant proteins inhibit wild-type RUNX1 in cotransfection studies.11 12

The evolutionarily conserved 128 amino acid Runt domain, present in most of RUNX1 isoforms, is involved in DNA binding and heterodimerization with PEBP2β/CBFβ.14,15Heterodimerization of RUNX1 with PEBP2β/CBFβ promotes DNA binding by stabilizing the interaction of the complex with the DNA.16,17 All RUNX1 point mutations described in FPD/AML patients10 and most RUNX1 point mutations in patients with sporadic leukemias11-13 are within the Runt domain and alter amino acids essential for DNA binding and heterodimerization.18,19 Longer RUNX1 proteins also contain a transactivation domain and domains involved in self-regulation, protein-protein interaction, and cellular localization.20 RUNX1 regulates the activity of several important hematopoietic genes, such as macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) receptor,21 T-cell receptor α and β,22 granulocyte-macrophage (GM)–CSF,23myeloperoxidase,24 and neutrophil elastase,25by binding to a core sequence (TGT/cGGT) found in their promoters or enhancers.

It has been proposed that haploinsufficiency for RUNX1 is responsible for FPD/AML.10 However, hyperactivating, inhibitory, and loss-of-function RUNX1 point mutations have all been reported in sporadic leukemia.11 This diversity in the mechanisms of pathogenesis of sporadic AML RUNX1 mutations suggested that FPD/AML RUNX1 mutations warranted further functional studies. Here we describe 3 new RUNX1 mutations in FPD/AML and potential mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of the disease based on in vitro studies of 7 RUNX1 FPD/AML mutations.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and genomic DNA isolation

Our FPD/AML pedigrees are shown in Figure1. Pedigree 1 has been extensively described.7 Fourteen members of the family have a hemorrhagic diathesis characterized by a long bleeding time, abnormal platelet aggregation, and decreased numbers of platelet-dense bodies. Among the affected individuals, there were 3 documented cases of myeloblastic leukemia, 2 documented cases of myelomonoblastic leukemia, and 3 cases of leukemia by history.

The FPD/AML pedigrees unique to this study.

All 3 pedigrees show linkage to FPD/AML locus (21q22.1-22.2). Half-filled symbols represent individuals who had a bleeding disorder and, where studied, a platelet defect as well, and completely filled symbols represent affected individuals who developed leukemia.

The FPD/AML pedigrees unique to this study.

All 3 pedigrees show linkage to FPD/AML locus (21q22.1-22.2). Half-filled symbols represent individuals who had a bleeding disorder and, where studied, a platelet defect as well, and completely filled symbols represent affected individuals who developed leukemia.

Pedigree 2 (previously unreported) has 8 affected individuals from 4 generations with a clinical history of prolonged bleeding. Constitutional thrombocytopenia was found in 5 members, 3 of whom had extensive platelet evaluations documenting aspirinlike aggregation defects and dense granule abnormality demonstrable by electron microscopic morphology and quinacrine fluorescence. Three individuals developed AML, and a fourth was said to have died of “pernicious anemia.”

Pedigree 3 consists of 15 affected individuals from 4 generations of a family with a bleeding disorder characterized by impaired platelet aggregation associated with decreased numbers and contents of both platelet-dense and α granules26,27 as well as a unique platelet phospholipid defect and decreased α-2 adrenergic receptors.28,29 The platelet counts in this family are at or slightly below the lower limit of normal.26,27 Two members of the family developed AML, and another was reported to have died of leukemia.29

Blood samples were obtained from healthy and affected individuals after obtaining informed consent and in accordance with institutional guidelines for human subjects. DNA was isolated from blood leukocytes using standard protocols.

Linkage analysis

Genotype information was generated with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of chromosome 21 microsatellite markers from the Genome Database (http://www.gdb.org). Linkage analysis was as previously described.4 5 At least 7 microsatellite repeat polymorphisms in the FPD/AML critical region of chromosome 21q22.1 3 were genotyped in each family.

Mutation analyses

All 9 exons of RUNX1 were amplified from genomic DNA using primers designed to the flanking region of each exon. Single-strand conformational polymorphism analysis was performed on PCR fragments of less than 400 base pairs using a Genephor apparatus and the GeneGel 12.5 kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany). Exons showing conformational changes were directly sequenced in both directions using BigDye terminator cycle sequencing (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and analyzed on an ABI377 sequencer.

RT-PCR

First-strand complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from patient (individuals IV:2 and V:2, pedigree 2) and control RNA using Superscript II reverse transcriptase. PCR was performed using primers AML1RTF3 (Figure 2D, primer C, 5′-CTGCTCCGTGCTGCCTACGCACTG-3′) in exon 3 of AML1b and AMLRTR1 (5′-CGCAGCTGCTCCAGTTCACTGAGC-3′) in exon 6 as reverse primer on these double-stranded cDNAs, cloned into a TA vector, and sequenced. A cryptic splice site was observed in one clone. Primers covering the cryptic splice junction of exon 4 and 5 (F2AMLmF4, Figure 2D, primer A, 5′-TAATGACCTCAGGGAAAAGCTTC-3′) and within the nucleotides of exon 4 excluded from the mutant transcript (F2AMLF1, Figure 2D, primer B, 5′-TGTCGGTCGAAGTGGAAGAGG-3′) were designed and used with AML1RTR1 to amplify a PCR product on patients' cDNA; no mutant transcript was observed in control cDNA.

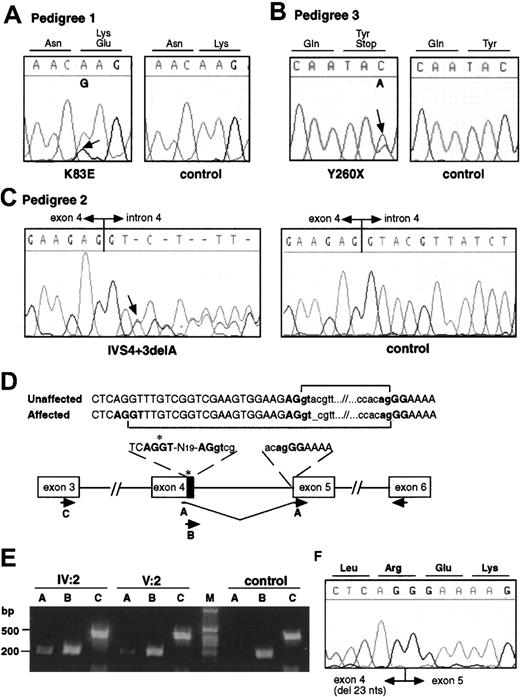

Mutation analysis in FPD/AML pedigrees.

Electropherograms from affected and control individuals showing the A>G substitution leading to the K83E missense mutation in pedigree 1 (A), the C>A substitution resulting in a nonsense mutation Y260X in pedigree 3 (B), and the deletion of an A at the +3 position of the splice donor site of intron 4 in pedigree 2 (IVS4 + 3delA, C). Arrows indicate the point of the mutations. (D) Schematic representation of the cryptic splice site within exon 4 used in the mutated transcript in pedigree 2 and the RT-PCRs used to analyze the splicing. A, B, and C represent forward primers used in the RT-PCR experiment. Primer A is specific to the mutated form, and primer B is specific to the wild-type form. Primer C was used as control. The same reverse primer was used in each reaction. The 23 nucleotides of exon 4 excluded from the mutant transcript are indicated by the black box. (E) RT-PCR on patient and control RNA as described in panel D. The primer specific to the mutated form does not show any amplification on control RNA. (F) Sequence analysis of the mutant exon 4–exon 5 junction.

Mutation analysis in FPD/AML pedigrees.

Electropherograms from affected and control individuals showing the A>G substitution leading to the K83E missense mutation in pedigree 1 (A), the C>A substitution resulting in a nonsense mutation Y260X in pedigree 3 (B), and the deletion of an A at the +3 position of the splice donor site of intron 4 in pedigree 2 (IVS4 + 3delA, C). Arrows indicate the point of the mutations. (D) Schematic representation of the cryptic splice site within exon 4 used in the mutated transcript in pedigree 2 and the RT-PCRs used to analyze the splicing. A, B, and C represent forward primers used in the RT-PCR experiment. Primer A is specific to the mutated form, and primer B is specific to the wild-type form. Primer C was used as control. The same reverse primer was used in each reaction. The 23 nucleotides of exon 4 excluded from the mutant transcript are indicated by the black box. (E) RT-PCR on patient and control RNA as described in panel D. The primer specific to the mutated form does not show any amplification on control RNA. (F) Sequence analysis of the mutant exon 4–exon 5 junction.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Amino acids 24 to 189 of RUNX1, including the Runt domain, were expressed in Escherichia coli, purified, and subjected to electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) essentially as described previously.11 The wild-type expression plasmid was previously described,11 and mutant RUNX1 plasmids were obtained by site-directed mutagenesis on wild-type pQE9-RUNX1 using Strategene's “quick change” method according to the manufacturer's instruction manual (Stratagene, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). For K90fsX101 an alternative vector, pQE13, was used instead to express it in fusion with a more bulky N-terminal appendage containing hexahistidines and dihydrofolate reductase. Mutant constructs were confirmed by sequencing.

Affinity assay of RUNX1-PEBP2β/CBFβ association

The heterodimerization activity of RUNX1 mutants impaired in DNA binding was assayed by MagExtractor kit (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan). Briefly, the hexahistidine-tagged RUNX1 fragment (1 μg) was incubated with tagless PEBP2β/CBFβ (1 μg) and mixed with nickel-coated magnetic beads. The mixture was successively washed with buffers containing 30 mM imidazole and eluted by the buffer supplied by the manufacturer. Proteins in each fraction were analyzed as previously described.11

Subcellular localization

For functional studies of mutated RUNX1 proteins, the wild-type RUNX1 sequence (1-453) was inserted into the pEF-BOS mammalian expression plasmid. Construction of RUNX1 mutants was carried out using the megaprimers method,30 and the resultant plasmids were transfected into NIH3T3 or REF52 (H58N, K83N, R177Q, and R177X only) cells using a nonliposomal transfection reagent FuGENE6 (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany). Immunofluorescence labeling of RUNX1 and PEBP2βCBFβ and microscopy were as previously described.11 For each transfection 50 cells were visualized.

Transactivation assays

The luciferase reporter plasmid (pM-CSF-R-luc) and the effector plasmid (pEF-AML1), containing the 453 amino acid isoform of RUNX1 with the mutations to be studied, were transfected at a fixed ratio (0.5 and 0.8 μg per assay, respectively) into U937, HL60, and Jurkat cells. Cell extracts were prepared 48 hours after transfection and assayed essentially as described.11 To study the inhibitory effect of mutant RUNX1 proteins on wild-type RUNX1 reporter gene activation, 0.5 μg pM-CSF-R-luc and 0.1 to 0.8 μg pEF constructs expressing either RUNX1 with or without mutations or PEBP2β-MYH11 were cotransfected into U937, HL60, and Jurkat cells. The total amount of DNA transfected was kept constant (1.3 μg) by supplementing appropriate amounts of the backbone pEF plasmid, thereby avoiding potential artifacts due to unbalanced DNA dosages.

Partial rescue from repression was obtained by transfecting varying doses of PEBP2βCBFβ with a repressive dose of wild-type and mutant proteins.

Results

Linkage and mutation analyses of the 3 new pedigrees

Each of the 3 families demonstrated features typical of FPD/AML. A candidate region genetic linkage analysis provided maximum 2-point log odds ratio scores of 3.14, 2.15, and 2.43 (θ = 0) with markers D21S1413 in pedigree 1, IFNAR in pedigree 2, and D21S65 in pedigree 3. Extended haplotype analysis of each family indicated an approximate 3 megabase common nonrecombinant interval on human chromosome 21q22.1 containing RUNX1 in affected individuals.

Pedigree 1 showed an A>G substitution in exon 3 resulting in a missense mutation, K83E (Figure 2A). The mutation segregates with the disorder in the family and was absent in 188 unrelated control chromosomes. Pedigree 2 showed a one-base deletion in the splice donor site of intron 4, IVS4 + 3delA (Figure 2C). The mutation segregates with the disorder in the family and was absent in 184 unrelated control chromosomes. Reverse transcriptase (RT)–PCR on RNA from affected individuals showed the use of a cryptic donor splice site, not used in control RNA, 23 nucleotides upstream of the normal splice site (Figure 2D-F). The novel transcript generated by the use of the cryptic splice site results in a frameshift after amino acid 135, addition of 41 unrelated residues, and termination at codon 177 (R135fsX177). Pedigree 3 showed a C>A substitution in exon 7B resulting in a nonsense mutation, Y260X (Figure 2B). The mutation segregated with the disease in all family members tested.

Effects of RUNX1 FPD/AML mutations on DNA binding and heterodimerization activities of the Runt domain

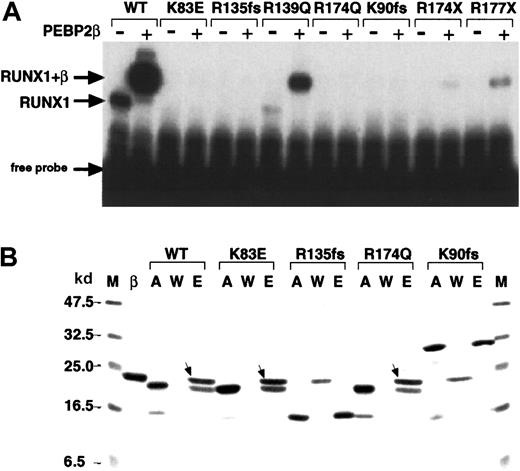

We examined the function of the Runt domain for 2 new (K83E and R135fsX177; SWISS-PROT Q01196) and 5 described (R139Q, R174Q, K90fsX101, R174X, R177X)10 FPD/AML point mutations. On EMSA analyses, R139Q, R174X, and R177X alone showed barely detectable DNA binding but produced a supershift band of increased intensity in the presence of PEBP2β/CBFβ, indicating that heterodimerization of these mutants with PEBP2β/CBFβ still occurs (Figure3A). K83E, R135fsX177, R174Q, and K90fsX101 showed no detectable DNA binding in the presence or absence of PEBPβ/CBFβ. An affinity assay of these mutants for heterodimerization with PEBP2β/CBFβ revealed that both missense mutants retained the ability to heterodimerize whereas both frameshift mutants did not (Figure 3B).

Alterations in the DNA binding and heterodimerization activities of the Runt domain of FPD/AML RUNX1 mutations.

(A) Partial RUNX1 proteins (as indicated) were subjected to EMSA in the presence (+) and absence (−) of PEBP2β/CBFβ. WT indicates wild-type RUNX1. The position of the RUNX1 and RUNX1/CBFβ complexes with the DNA are indicated. (B) Affinity assay of the indicated partial RUNX1 proteins with PEBP2β/CBFβ. M indicates molecular weight marker as indicated both to the left and right; β, PEBP2β/CBFβ; A, input RUNX1 protein; W, unbound proteins in washed fractions; E, bound proteins eluted at 250 mM imidazole. The bands marked with arrows indicate the β subunits associated with RUNX1 proteins.

Alterations in the DNA binding and heterodimerization activities of the Runt domain of FPD/AML RUNX1 mutations.

(A) Partial RUNX1 proteins (as indicated) were subjected to EMSA in the presence (+) and absence (−) of PEBP2β/CBFβ. WT indicates wild-type RUNX1. The position of the RUNX1 and RUNX1/CBFβ complexes with the DNA are indicated. (B) Affinity assay of the indicated partial RUNX1 proteins with PEBP2β/CBFβ. M indicates molecular weight marker as indicated both to the left and right; β, PEBP2β/CBFβ; A, input RUNX1 protein; W, unbound proteins in washed fractions; E, bound proteins eluted at 250 mM imidazole. The bands marked with arrows indicate the β subunits associated with RUNX1 proteins.

Subcellular localization of the FPD/AML RUNX1 mutants and colocalization with PEBP2β/CBFβ

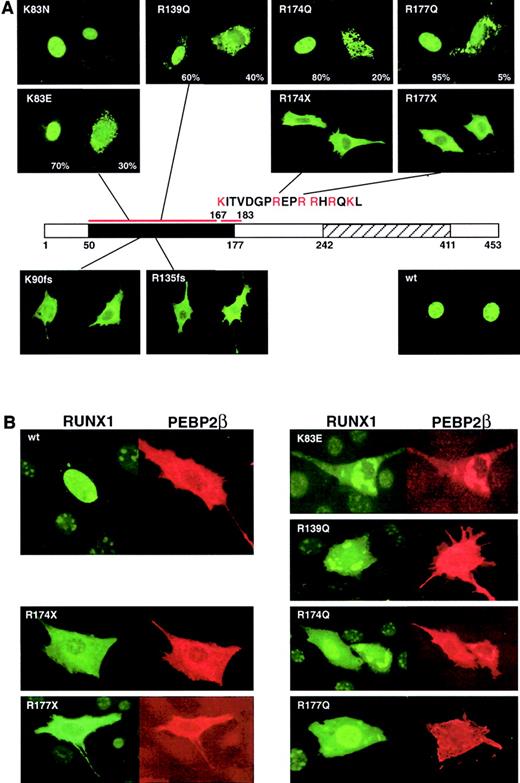

In RUNX1 a nuclear localization signal (NLS) is present at amino acids 167 to 183 at the end of the Runt domain. RUNX1 wild-type protein is localized in the nucleus with a diffuse pattern and is excluded from the nucleoli (Figure 4A). Transfection of mutant full-length cDNAs into NIH3T3 cells and immunostaining the expressed RUNX1 proteins revealed that the frameshift (R135fsX177 and K90fsX101, no NLS) and nonsense (R174X and R177X, half of the NLS is missing) mutants are localized almost exclusively in the cytoplasm. Consistent with the importance of basic amino acids in the NLS, R174Q and R177Q (a sporadic mutation described by Osato et al11) showed cytoplasmic localization in 20% and 5% of observed cells, respectively (Figure 4A).

Subcellular localization of mutant RUNX1 proteins and colocalization with PEBP2β/CBFβ.

(A) Subcellular localization of the indicated RUNX1 proteins was detected by immunofluorescence staining with anti-αB1. A schematic of the RUNX1 protein is shown with the Runt and transactivation domains indicated. The sequence of the NLS is indicated. (B) Double staining for mutant RUNX1 and PEBP2β/CBFβ reveals that the subunits are colocalized in the cytoplasm within speckled dotlike structures for the missense mutants and a diffuse staining pattern for the frameshift and nonsense mutations. All examples in this figure are in NIH3T3 cells. Original magnification, × 400.

Subcellular localization of mutant RUNX1 proteins and colocalization with PEBP2β/CBFβ.

(A) Subcellular localization of the indicated RUNX1 proteins was detected by immunofluorescence staining with anti-αB1. A schematic of the RUNX1 protein is shown with the Runt and transactivation domains indicated. The sequence of the NLS is indicated. (B) Double staining for mutant RUNX1 and PEBP2β/CBFβ reveals that the subunits are colocalized in the cytoplasm within speckled dotlike structures for the missense mutants and a diffuse staining pattern for the frameshift and nonsense mutations. All examples in this figure are in NIH3T3 cells. Original magnification, × 400.

While the K83E and R139Q mutations are not within the known NLS, both mutant proteins showed reduced nuclear localization. K83E showed cytoplasmic localization in 30% of transfected cells, in contrast to the normal nuclear localization seen in K83N (a sporadic mutation; Figure 4A).11 This observation may suggest that the K83E mutation (K, positive, hydrophilic, C6; E, negative, hydrophilic, C5) results in greater loss of function than the K83N mutation (N, polar, hydrophobic, C4). The R139Q mutation is at a site involved in DNA binding18 and was expected to affect DNA binding rather than nuclear localization. However, cytoplasmic localization was observed in 40% of cells. The observed defect in nuclear localization in K83E and R139Q is consistent with earlier studies31 and may point to the existence of an additional unidentified N-terminal domain critical for nuclear localization.

In contrast to RUNX1, PEBP2β/CBFβ is normally localized in the cytoplasm before heterodimerization32 and can enter the nucleus only with RUNX1.31 However, the regulation of the heterodimerization remains unknown, and it has been shown that both proteins may have different cellular localizations when transfected in the same cells.31 The missense mutants showed speckled dotlike distribution in the cytoplasm, markedly different from the diffuse pattern of the truncated or nonsense mutants. Double staining for the α and β subunits revealed that they colocalized within these speckled patterns (Figure 4B).

Transactivation abilities of the FPD/AML RUNX1 mutants

The transactivation potential of the mutant RUNX1 proteins was measured using a reporter construct based on the M-CSF receptor promoter as a myeloid-specific RUNX1-target.33,34Wild-type RUNX1 demonstrated more than 100-fold transactivation compared with the FPD/AML mutants, which showed no significant transactivation with or without PEBP2β/CBFβ (Figure5A). Despite the retention of DNA binding activity and C-terminal activation domains, R139Q failed to transactivate. Several mutants showed persistently lower luciferase activities than the mock-transfected plasmid, indicating that these mutants could hinder the function of endogenous RUNX1 in U937 cells. To allow measurement of inhibition of the wild-type transactivational activities caused by the mutant proteins, the reporter construct and a fixed amount of nonsaturating wild-type RUNX1 plasmid were cotransfected with varying amounts of FPD/AML mutant plasmids encoding mutant proteins with DNA and/or PEBP2β/CBFβ binding activity. PEBP2β/CBFβ-MYH11 and K83N repressed the M-CSF receptor promoter as previously reported.11 35 With the exception of R177X, all of the mutants showed varying degrees of interference with the wild-type protein function in all cell lines tested (U937, HL60, and Jurkat). Most notably, K83E and R174Q showed potent inhibition similar to that of PEBP2β/CBFβ-MYH11 (Figure 5B). The results of cotransfection reporter assays using frameshift mutants are not reproducible within or between cell lines.

Transactivation of the M-CSF receptor promoter by exogenously expressed RUNX1 proteins.

(A) Cells were transfected with a luciferase reporter plasmid and the indicated RUNX1 expression constructs. Luciferase activities were measured and presented as the fold increase relative to the control transfected with the backbone expression vector. (B) The wild-type RUNX1 and missense RUNX1 mutants were coexpressed in varying doses as indicated. Luciferase activities are expressed as fold changes relative to the activity observed at the standard dose (0.3 μg) of the wild-type RUNX1 alone. (C) PEBP2β/CBFβ was transfected in varying doses with a repressive dose of wild-type and mutant RUNX1 proteins. In panels A-C, each value represents the mean of 3 separate experiments. The luciferase activity of the y-axis in panel C is shown as relative luciferase units (RLU). Deviations of the measurements are given by thin vertical bars. The chimeric protein PEBP2β/CBFβ-MYH11 and the sporadic mutation K83N were used as controls in each experiment. All examples in this figure are in U937 cells.

Transactivation of the M-CSF receptor promoter by exogenously expressed RUNX1 proteins.

(A) Cells were transfected with a luciferase reporter plasmid and the indicated RUNX1 expression constructs. Luciferase activities were measured and presented as the fold increase relative to the control transfected with the backbone expression vector. (B) The wild-type RUNX1 and missense RUNX1 mutants were coexpressed in varying doses as indicated. Luciferase activities are expressed as fold changes relative to the activity observed at the standard dose (0.3 μg) of the wild-type RUNX1 alone. (C) PEBP2β/CBFβ was transfected in varying doses with a repressive dose of wild-type and mutant RUNX1 proteins. In panels A-C, each value represents the mean of 3 separate experiments. The luciferase activity of the y-axis in panel C is shown as relative luciferase units (RLU). Deviations of the measurements are given by thin vertical bars. The chimeric protein PEBP2β/CBFβ-MYH11 and the sporadic mutation K83N were used as controls in each experiment. All examples in this figure are in U937 cells.

Because all inhibitory mutants maintained the ability to heterodimerize and all colocalized with PEBP2β/CBFβ, sequestration of PEBP2β/CBFβ by mutant RUNX1 proteins may be the major inhibitory mechanism. To test this hypothesis, PEBP2β/CBFβ was cotransfected in increasing amounts together with inhibitory amounts of mutant RUNX1, resulting in the restoration of near- normal reporter gene activity (Figure 5C).

Discussion

Five RUNX1 point mutations and a deletion of the entire RUNX1 gene have previously been described in FPD/AML. Here we report 3 new RUNX1 point mutations associated with the disease. Y260X, in pedigree 3, is at the beginning of the transactivating domain and removes a part of the negative regulatory region for DNA binding.20,31 It is the first described familial RUNX1 mutation outside the Runt domain. As such, the studies described in this paper are not appropriate to test the functional implications of this mutation. Functional analyses of 7 mutants (2 frameshift, 2 nonsense, and 3 missense mutations) were performed to investigate the mechanisms that contribute to FPD/AML, particularly the propensity to develop AML. The capacity to bind DNA was reduced or abolished in all mutant proteins as expected from the sites of substitutions in the Runt domain. The missense and nonsense mutant proteins (largely intact Runt domain) retained the capacity to heterodimerize with PEBP2β/CBFβ. The frameshift mutant proteins, which lack a substantial part of the Runt domain, failed to heterodimerize, as has been reported in a sporadic RUNX1 AML nonsense mutation S114X.11 These observations are consistent with the known crystal structure and predicted binding domain of mouse Runx1. The positions of the 3 missense mutations are not critical for the structural integrity of the dimerization site, whereas the frameshift mutant proteins are predicted to fold abnormally and lack Runt domain residues required for heterodimerization.18

Do the mechanisms of pathogenesis of sporadic leukemias provide any clues to the mechanisms of pathogenesis in FPD/AML? In many sporadic hematologic malignancies, the same chromosomal rearrangements consistently appear, supporting the hypothesis that these events are a prerequisite for tumor induction. The somatic mutations acquired in leukemia by translocations and inversions are heterozygous in affected cells; normal copies of the translocated genes are still present. Consequently, the mechanism(s) of disease pathogenesis may include (1) a gain of function by chimeric fusion proteins, (2) haploinsufficiency, (3) a dominant-negative effect of the chimeric fusion proteins, and/or (4) a combination of these mechanisms. However, it is unlikely that the mutations described here have a gain-of-function activity.

Haploinsufficiency of RUNX proteins

The importance of gene dosage to the normal function of CBF transcriptional regulators is seen in the autosomal dominant human bone disorder, cleidocranial dysplasia, caused by mutations inRUNX2 (also called CBFα1).36,37Runx2+/− mice show skeletal defects similar to those in cleidocranial dysplasia.38 RUNX2 mutations may be heterozygous missense mutations, insertions, and deletions in either the Runt DNA binding domain or more C-terminal domains responsible for transactivation.39 RUNX2 point mutations are predicted to affect the folding and stability of RUNX2,18 resulting in haploinsufficiency of RUNX2 and defects in bone formation.36 40-43

Complete deletion of RUNX1 results in haploinsufficiency in FPD/AML.10 The 2 FPD/AML splice site mutations resulting in frameshifts R135fsX177 and K90fsX101 cause loss of DNA binding, heterodimerization, nuclear localization, and transactivation functions and are also likely to act through simple haploinsufficiency.

Dominant-negative effects of mutant RUNX proteins?

Translocations involving RUNX1 produce chimeric proteins, most notably RUNX1/AML1-ETO(MTG8) in AML t(8;21) and TEL-RUNX1/AML1 in ALL t(12;21). These chimeric proteins both retain the entire Runt domain and have been shown to interfere with transactivation by the normal RUNX1 in a dominant-negative manner.44-46 RUNX1/AML1-ETO and related fusion proteins have been shown to form complexes with PEBP2β/CBFβ and other nuclear proteins more efficiently than wild-type RUNX1.47-49 Moreover, naturally occurring isoforms of RUNX1 proteins that contain only the Runt domain can also suppress transactivation by full-length RUNX1.50 Deletion of a negative regulatory domain for heterodimerization in the C-terminal region of full-length RUNX1 (amino acids 372-451) results in more efficient heterodimer formation.31 Thus, chimeric RUNX1 proteins resulting from translocations and the isoforms of RUNX1 without the transactivation domain50 may act in the same manner by dimerizing with PEBP2β/CBFβ more efficiently than the wild type.

Cotransfection of equal amounts of wild-type and mutant plasmids closely mimics the in vivo situation of one normal and one mutant allele. All FPD/AML RUNX1 missense and nonsense mutants studied, except R177X, show a decrease in their transactivation capacities and an inhibitory effect on wild-type RUNX1 upon cotransfection and thus also seem to act as dominant-negative inhibitors. Both the missense and nonsense mutants still interact with PEBP2β/CBFβ, and both nonsense mutants studied here lack the negative regulatory domain for heterodimerization. R139Q and the 2 nonsense mutant proteins maintain some degree of DNA binding, although the DNA binding of the nonsense mutations may be irrelevant in vivo due to their cytoplasmic localization resulting from a direct disruption of the NLS. The missense mutants, while appropriately translocated to the nucleus most of the time, also show some cytoplasmic staining. The inhibitory nature of these mutants is likely to be due to competition with wild type for dimerization with PEBP2β/CBFβ and its sequestration. In the case of R174X, this must occur in the cytoplasm, whereas for the missense mutations it may occur in both the nucleus and cytoplasm. R177X, which differs from R174X by only 3 amino acids, did not show significant repression of the wild-type RUNX1 in the cotransfection assay and may be considered as haploinsufficient. Structural analysis of the C-terminal end of the Runt domain by nuclear magnetic resonance suggested that this is a region of conformational flexibility.51 R174X, which lacks 3 amino acids in this region, might show decreased flexibility and increased affinity for PEBP2β/CBFβ over R177X. Alternatively, the lack of inhibition by R177X could be due to technical difficulties inherent in the assay, as seen by the inconclusive results observed for the frameshift mutations.

One of the notable features of the FPD/AML RUNX1 missense mutants studied here is the colocalization of the RUNX1 and PEBP2β/CBFβ in cytoplasmic speckles, where sequestration of PEBP2β/CBFβ could occur. There is a correlation between colocalization, PEBP2β/CBFβ interaction in vitro, and the level of the inhibitory effect. Because no such pattern was seen with the nonsense and frameshift mutants prematurely terminated within the Runt domain, the presence of the C-terminal region must be required for aggregation of RUNX1 into the speckled cytoplasmic patterns. This raises the possibility that the speckled structures could be the result of C-terminal–associating molecules, which could also be sequestered in the cytoplasm.

It was recently shown that dimerization with PEBP2β/CBFβ protects RUNX1 from ubiquitin-proteasome–mediated degradation, and substitution of K83 to R was shown to increase the half-life of RUNX1 as lysine residues are ubiquitylated.52 Preferential binding of mutant RUNX1 proteins to PEBP2β/CBFβ may increase their half-lives. K83E may be the most potent nonchimeric mutant inhibitor of wild-type RUNX1 described so far because K83 is a residue important for ubiquitinylation.

Mice heterozygous for the RUNX1/AML1-ETO or PEBP2β/CBFβ-MYH11 knocked-ins showed defects in definitive hematopoiesis similar to those observed in Runx1−/− or PEBP2β/CBFβ−/−mice.53,54 Thus, expression of strong dominant-negative inhibitors of RUNX1 seems to produce an embryonic lethal phenotype. The dominant transmission of RUNX1 mutations in FPD/AML implies that strong dominant-negative RUNX1 mutations would also be expected to be lethal. Another study recently showed dominant-negative mutations inCEBPA encoding the C/EBPα transcription factor in sporadic AML. However the dominant-negative effects of the predominantly frameshift mutations described in this study do not have an inhibitory effect by themselves but by increased formation of a secondary protein product by use of a downstream-initiating methionine.55

Progression to leukemia in FPD/AML

Haploidy of RUNX1 is clearly sufficient for normal development but possibly insufficient for tumor suppression. Runx1−/−mice show a complete lack of definitive hematopoietic cells in the fetal liver, with death occurring from hemorrhages in the central nervous system at 12.5 days after coitus.56Runx1+/− mice demonstrate minimal changes in phenotype,56-58 although closer hematologic analysis has revealed a trend for bone marrow progenitor cells to have increased sensitivity to G-CSF, possibly reflecting a propensity to develop myelogenous leukemia.59

The presence of biallelic RUNX1 mutations in sporadic leukemias may indicate that RUNX1 functions as a classical tumor suppressor gene.11,13 However, in other cases of sporadic leukemia only monoallelic RUNX1 mutations were described.11,13 Also, in FPD/AML leukemic patients—one each from the families with the complete RUNX1 deletion and R177X (annotated as R203X by Song et al10)—analysis of leukemic cells failed to detect RUNX1 mutations or deletion of the second RUNX1 allele.

Two tumor suppressor genes (p53 and p27Kip1) have been shown to be haploinsufficient for tumor suppression in hemizygous mice where the potential complication of dominant-negative mutations can be excluded.60,61 A revision of the Knudson model has been proposed to accommodate haploinsufficiency. The normal level of biologic activity of a tumorigenic gene is tightly controlled, and an increase or decrease in this activity leads to increased tumor susceptibility. In a multiprotein complex or molecular cascade, hemizygous loss of each of 2 (or more) partners or molecules in the same pathway may be almost as tumorigenic as homozygous loss of any one partner.62

While mutations in early-acting genes such as RUNX1 predispose to development of hematologic malignancies, the affected lineage and consequent type of malignancy may depend upon which genes subsequently sustain downstream “hits” from additional somatic mutation. For example, combined positivity for antigens CD34, C-KIT, and HLA-DR characterizes the CBF leukemias AML-M2 (RUNX1/AML1-ETO t(8;21)) and AML-M4Eo (PEBP2β/CBFβ-MYH11 inv(16)).63 C-KIT (CD117) is a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor for stem cell factor, which is required for normal hematopoiesis. Mutations in C-KIT have been described in various sporadic hematologic malignancies and other diseases.63-67 For example, mutations of residue D816 in exon 17 of C-KIT were detected in 6 of 15 patients with either t(8;21) AML-M2 or inv(16) AML-M4Eo.68

It is difficult to make a robust correlation between the type of mutation and the proportion of patients who develop leukemia in FPD/AML families, because of the limited number of individuals identified and a lack of detailed clinical information. It would appear, however, that families with mutations acting simply via haploinsufficiency (deletions and frameshift mutations) show a smaller proportion of affected individuals who develop leukemia than do families transmitting mutations that may act in a dominant-negative fashion (Figure6). This is consistent with the hypothesis that a second mutation has to occur in RUNX1 or other genes to cause leukemia among individuals harboring an inheritedRUNX1 mutation, and these mutations are more likely to occur in the individuals with lower biologic activity of RUNX1. For example, in 2 of the largest FPD/AML pedigrees, a markedly higher rate of leukemia is seen in the family with strong predicted dominant-negative K83E mutation (57%) compared with the pedigree with a complete deletion of RUNX1 (24%).

A summary of the FPD/AML RUNX1 mutants and the studies presented in this paper.

The FPD/AML RUNX1 mutants are listed in descending order of PEBP2/CBF activity. The Runt and transactivation domains are indicated on the mutant proteins as appropriate. Pedigrees 1 to 6 are from Song et al,10 and A1 and A2 are described in this paper. The results of the EMSA (DNA binding), affinity assay (PEBP2β/CBFβ subunit interaction), subcellular localization, and transactivation studies are summarized. The ratio of leukemic FPD individuals to FPD-affected individuals in each pedigree is indicated on the right. In the largest FPD/AML pedigrees, a markedly higher rate of leukemia is seen in the family with strong predicted dominant-negative K83E mutation (pedigree A1, dominant-negative, 57%) compared with the pedigree with a complete deletion of RUNX1 (pedigree 1, haploinsufficiency, 24%).

A summary of the FPD/AML RUNX1 mutants and the studies presented in this paper.

The FPD/AML RUNX1 mutants are listed in descending order of PEBP2/CBF activity. The Runt and transactivation domains are indicated on the mutant proteins as appropriate. Pedigrees 1 to 6 are from Song et al,10 and A1 and A2 are described in this paper. The results of the EMSA (DNA binding), affinity assay (PEBP2β/CBFβ subunit interaction), subcellular localization, and transactivation studies are summarized. The ratio of leukemic FPD individuals to FPD-affected individuals in each pedigree is indicated on the right. In the largest FPD/AML pedigrees, a markedly higher rate of leukemia is seen in the family with strong predicted dominant-negative K83E mutation (pedigree A1, dominant-negative, 57%) compared with the pedigree with a complete deletion of RUNX1 (pedigree 1, haploinsufficiency, 24%).

Thus, we propose that the less functional PEBP/CBF transcriptional regulation complex present in a hematopoietic cell due to variable inhibitory effects of heterozygous mutations, or mutations of both alleles, the higher the propensity to develop leukemia. This mechanism is valid for FPD/AML or sporadic leukemia patients. Clearly, biallelic mutations would be more prone to leukemia development although additional genetic changes may still be required in other genes. Analyses of additional FPD/AML and sporadic leukemia cases with additional clinical and molecular data, including mutation analyses of genes coding for partners of PEBP/CBF or molecules in the same tumorigenic pathway, will help provide evidence for this hypothesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and their families for their participation, Loretta Dougherty and Pauline Crewther for reading the manuscript, Wendy Cook for discussions on haploinsufficiency, Frédéric Schütz and Melanie Bahlo for aid with statistics, and Dong-Er Zhang for providing the M-CSF-R-luc reporter plasmid.

Supported by grants from the Ligue Genevoise Contre le Cancer, the Fondation Pour la Lutte Contre le Cancer, the Fondation Dr Henri Dubois-Ferrière Dinu Lipatti, and the Nossal Leadership Fellowship from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research to H.S.S.; the International Postgraduate Research (Australian government) and Melbourne International Research scholarships to J.M.; the Swiss FNRS (31-57149.99) to S.E.A.; Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture, Japan, to Y.I.; grants from the NIH (DK55820 and DK58161), Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (T98006), ALS (6443-00), and the American Cancer Society (RPG-99-319-01-LBC) to M.H.

J.M. and F.W. contributed equally to this article.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Hamish S. Scott, Genetics and Bioinformatics Div, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Royal Parade, Parkville, PO Royal Melbourne Hospital, Victoria 3050, Australia; e-mail: hscott@wehi.edu.au.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal