In multiple myeloma cells, insulinlike growth factor–I (IGF-I) activates 2 distinct signaling pathways, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphoinositol 3-kinase (PI-3K), leading to both proliferative and antiapoptotic effects. However, it is unclear through which of these cascades IGF-I regulates these different responses. The present studies identify a series of downstream targets in the PI-3K pathway, including glycogen synthase kinase–3β, p70S6 kinase, and the 3 members of the Forkhead family of transcription factors. The contribution of the MAPK and PI-3K pathways and, where possible, individual elements to proliferation and apoptosis was evaluated by means of a series of specific kinase inhibitors. Both processes were regulated almost exclusively by the PI-3K pathway, with only minor contributions associated with the MAPK cascade. Within the PI-3K cascade, inhibition of p70S6 kinase led to significant decreases in proliferation and protection from apoptosis. Activation of p70S6 kinase could also be prevented by MAPK inhibitors, indicating regulation by both pathways. The Forkhead transcription factor FKHRL1 was observed to provide a dual effect in that phosphorylation upon IGF-I treatment resulted in a loss of ability to inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis. The PI-3K pathway was additionally shown to exhibit cross-talk and to regulate the MAPK cascade, as inhibition of PI-3K prevented activation of Mek1/2 and other downstream MAPK elements. These results define important elements in IGF-I regulation of myeloma cell growth and provide biological correlates critical to an understanding of growth-factor modulation of proliferation and apoptosis.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a lymphoid cancer of terminally differentiated B-lineage or plasma cells characterized by accumulation of malignant cells in the bone marrow. While the molecular lesions contributing to initiation and progression of this disease are still poorly understood, significant advances in understanding the biology of MM have resulted from the study of signaling pathways that contribute to survival and/or proliferation of these cells. Considerable attention has been focused over the past several years on interleukin 6 (IL-6) as a major growth factor in MM.1-3Such a role for IL-6 is predicated largely on the identification of a number of IL-6–dependent cell lines,4 the ability of primary explants to proliferate in response to IL-6,5 and the transient effect on tumor growth in patients treated with antibodies to IL-6 or IL-6 receptor.6,7 The most convincing evidence for a critical IL-6 role in plasma cell tumor development comes from animal models in which such tumors fail to develop in IL-6–null mice.8,9 It should be noted that most MM cell lines are not IL-6 dependent, and a proliferative response to IL-6 was reported in only 40% to 60% of cells isolated from patients with advanced MM.3 Thus, a potentially important role for other growth factors in myeloma development appears likely. Among such candidates, several studies have recently demonstrated that insulinlike growth factor–I (IGF-I) can act as a myeloma growth factor,10-14 producing effects similar to those observed upon IL-6 stimulation. Furthermore, IGF-I induces proliferation of IL-6–independent and IL-6–dependent cell lines11,13,14and can act synergistically with IL-6.12

Given the potential role of IGF-I as a significant factor in myeloma development, characterization of the associated signaling pathway is important both to an understanding of disease biology and to providing a basis for entertaining novel therapeutic approaches. IGF-I signaling is initiated upon binding of ligand to cognate receptor (IGF-IR), consisting of homodimers of 2 extracellular α-subunits that serve as the binding domain, and homodimers of 2 transmembrane β-subunits that possess intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity.15 Ligand binding activates the β-subunit tyrosine kinase domains, resulting in autophosphorylation of receptor and several associated substrates. Recent studies in myeloma lines13,14,16 have identified 2 distinct downstream pathways activated by IGF-I. The first of these involves receptor phosphorylation of the insulin response substrate 1 and its activation of PI-3K and subsequently Akt kinase (PI-3K pathway). Several important biological characteristics have been associated with this segment of the PI-3K pathway. Akt subsequently phosphorylates Bad, a member of the Bcl-2 family, producing an antiapoptotic effect. Also, regulation of Akt phosphorylation by the PTEN tumor suppressor gene is critical in tumor cell proliferation, as in vivo growth of a myeloma line lacking PTEN can be prevented by expression of normal PTEN protein following gene transfection.17 The second pathway associated with IGF-I stimulation signals through the Shc, Grb-2, Sos complex, resulting in activation of Ras and subsequently the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling cascade. Whereas at least part of the effect of the PI-3K pathway has been demonstrated to be associated with apoptosis, the role of additional members of this cascade, as well as those in the MAPK pathway, has, in terms of proliferation or apoptosis, not been defined in myeloma cells.

In an effort to associate biological functions with specific elements of the PI-3K and MAPK pathways, we have, in the present studies, identified a series of downstream elements and determined their roles in proliferation and/or apoptosis. Additionally, we have identified cross-talk between elements of these pathways that further identify previously unappreciated complex interactions in cell growth regulation. Results of these studies provide new insights into the mechanism by which IGF-I serves as a potent regulator of myeloma cell growth.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

Human MM cell lines H929, OPM-2, MM144, and RPMI8226 were cultured in RPMI1640 (Biofluids, Rockville, MD) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL) at 37°C in humidified 95% air and 5% CO2. H929 cells expressing wild-type or mutant FKHRL1 were maintained in 10% FCS containing G418 (1 mg/mL).

Reagents and antibodies

Human recombinant IGF-I was purchased from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ). LY294002, PD98059, rapamycin, anti–p-Ser256-FKHR, anti-FKHR, anti–Ser193-AFX, anti–p-Ser473–Akt, anti–p-Thr308-Akt, anti–Ser9–glycogen synthase kinase–3β (anti–Ser9–GSK3β), anti–p-Thr421/Ser424-p70S6K, anti–p-Mek1/2; anti–p-p44/42 MAP kinase antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Anti–p-Ser253-FKHRL1, anti–p-Thr32-FKHRL1, and anti–HA-tag antibodies were obtained from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY). Horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antimouse or antirabbit antibodies were from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY). G418 was purchased from Invitrogen–Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA).

Retrovirus production and infection

Plasmids encoding wild-type (pECE-HA-FKHRL1WT) and mutant (pECE-HA-FKHRL1Thr32Ala, pECE-HA-FKHRL1Ser253Ala, and pECE-HA-FKHRL1Ser315Ala) Forkhead transcription factors18were kindly provided by Dr M. Greenberg, Division of Neuroscience, Children's Hospital, Harvard Medical School (Boston, MA). The inserts from pECE-HA-FKHRL1WT or the mutant derivatives were released with BamHI and EcoRI and ligated into the pFB-neo retroviral vector (Stratagene, LaJolla, CA) to give pFB-HA-FKHRL1 WT and mutant derivatives. The recombinant retrovirus DNA, isolated from ampicillin-resistant clones, was amplified in DH5α cells, purified, and transfected into BOSC23 cells with Lipofectamine (Invitrogen–Life Technologies). After 48 hours, packaged virus was collected and used to infect H929 cells (5 × 105) in the presence of polybrene (8 μg/mL). Clonal cell lines were generated by limited dilution in growth media containing 1 mg/mL G418.

Western blotting and immunoprecipitation

Cells (1 × 107) were grown in serum-free media for 14 hours and pretreated with indicated concentrations of LY294002, PD98059, or rapamycin for 1 hour. Cultures either were stimulated with 100 ng/mL IGF-I for 5 minutes or other indicated times, or were not stimulated. Following treatment, cells were washed with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1 mM sodium orthovanadate (Na3VO4) and 1 mM sodium fluoride (NaF) and then solubilized in lysis buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 2.5 mM EDTA, 10 mM leupeptin, 10 mM pepstatin, 10 mM aprotinin, 10 mM NaF, 10 mM NaPPi, 1 mM 4-(2-aminoethyl)-benzenesulfony fluoride hydrochloride (AEBSF), and 250 mM Na3VO4. After incubation for 30 minutes at 4°C, cell debris and nuclei were removed by centrifugation at 15 000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C. Protein concentration was determined by BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Lysates were snap frozen in dry ice and stored at −80°C. Equal concentrations of total protein (50 μg per lane) combined with an equal volume of 2 × Laemmli buffer were boiled at 100°C for 3 minutes, and then separated on 8% to 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–polyacrylamide gels followed by electrophoretic transfer to Immobilon polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dried milk in Tris-buffered saline–Tween20 and incubated for 1 or 2 hours with specific antibody. Detection was performed by a standard procedure with the use of 0.2 μg/mL of a panel of secondary horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antibodies and chemiluminescence (ECL, Amersham, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom).

[3H]-thymidine incorporation assay

DNA synthesis was measured as previously described.13 Briefly, exponentially growing cells were washed with PBS and resuspended in serum-free RPMI1640 for 2 hours. Following pretreatment with indicated concentrations of LY294002 (10 μM), PD98059 (20 μM), and rapamycin (10 nM) for 1 hour, cells were incubated at a density of 3 × 104 per well in 96-well culture plates (Costar, Cambridge, MA) with or without 100 ng/mL IGF-I for 48 hours at 37°C. To measure DNA synthesis, 0.5 μCi (18.5 kBq) [3H]-thymidine (Amersham International, Arlington Heights, IL) per well was added during the final 4 hours of culture. Cells were harvested onto glass filters with an automatic cell harvester (Cambridge Technology, Cambridge, MA) and counted by means of an LKB beta plate scintillation counter (Wallac, Gaithersburg, MD). All experiments were performed in triplicate.

MTT assay for cell proliferation

Proliferation of MM cells was also examined by colorimetric 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazollium bromide (MTT) assay as previously described.19 Following pretreatment with the above described inhibitors, cells were incubated in 96-well culture plates with or without 100 ng/mL IGF-I for 20, 44, and 68 hours. First, 10 μL 5 mg/mL MTT (Sigma, St Louis, MO) was added to each well for 4 hours; this was followed by incubation overnight in 100 μL 10% SDS in 0.01 N HCl at 37°C. Optical density of plates was read on a Bio-Rad 550 microplate reader (Hercules, CA) at 570 nm. In some experiments, following incubation with 100 ng/mL IGF-I, cells were incubated in growth media plus dexamethasone (Dex) (10 μM) for 48 hours and then subjected to MTT assay.

Detection of apoptotic cells

Following pretreatment with or without indicated kinase inhibitors, cells were incubated in growth media in the presence or absence of 100 ng/mL IGF-I for 1 hour followed by addition of 1 μM Dex for 36 hours. Apoptotic cells were detected according to the manufacturer's instructions (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD). Briefly, cells (1 × 105) were incubated with 3 μL annexin V–biotin and 5 μL propidium iodide for 15 minutes. Streptavidin fluorescein was then added for an additional 15 minutes, after which cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (FACScan, Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) with the use of Cell Quest software.

Statistical analysis

Student t test was performed to analyze the statistical significance of differences between experimental groups by means of the Statview J 4.11 software statistical package (Abacus Concept, Berkeley, CA). P < .05 by the 2-tailed test was considered significant.

Densitometry analysis for quantitative determination of Western blot bands in the linear range was performed with a DeskScan 4c (Hewlett-Packard, Meriden, CT) and analyzed by National Institutes of Health Image 1.61 computer software.

Results

We have previously described activation of both the MAPK and PI-3K kinase pathways following treatment of myeloma cells with IGF-I.13 In these studies, Akt was identified as a downstream element in the PI-3K pathway and found to subsequently phosphorylate Bad, an important event leading to antiapoptotic effects. Since the response to IGF-I is both proliferative and antiapoptotic, we have here sought to identify additional downstream targets and, where possible, determine their roles in these biological processes.

Downstream elements in the PI-3K pathway

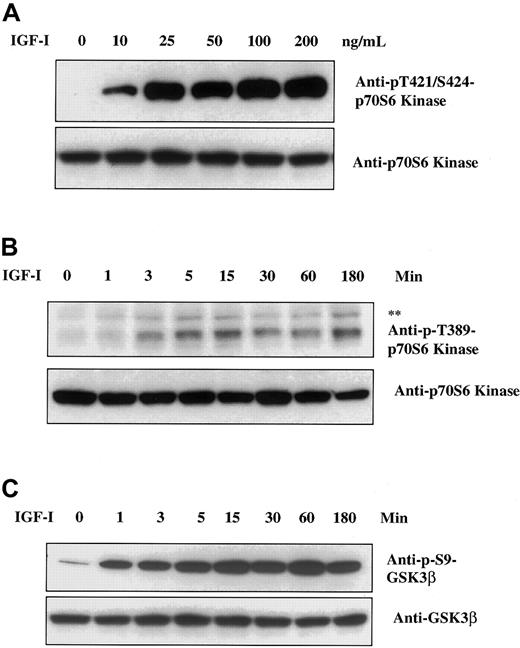

Akt appears to be a key protein involved in signaling to a number of additional downstream elements. We therefore used Western blot analysis to search for targets of Akt kinase activity that might be important in regulation of myeloma cell growth. As seen in Figure1A, IGF-I stimulation of H929 cells leads to phosphorylation of the 70-kd ribosomal protein S6 kinase (p70S6) (an important effector of both cell survival and growth20-22) as detected by antibodies specific for p-Thr421/Ser424 sites. Increasing p70S6 phosphorylation was observed at IGF-I concentrations ranging from 10 to 200 ng/mL. With the use of an additional antibody directed to p-Thr389 in a time course study (Figure 1B), phosphorylation was evident at 3 minutes, peaked at 15 minutes, and remained at these levels for 180 minutes. These findings indicate that IGF-I induces phosphorylation of p70S6K in a dose- and time-dependent manner. The p-Thr389-p70S6K antibody also detects p85S6K when phosphorylated at Thr389. The p85S6K and p70S6K are isoforms of the same kinase and differ by a 23–amino acid extension that constitutively targets p85S6K to the nucleus.23

Effect of IGF-I on p70S6 kinase and GSK3β.

IGF-I induces phosphorylation of p70S6 kinase and GSK3β. H929 cells were cultured in serum-free growth medium for 16 hours and then stimulated with increasing concentrations of IGF-I (1-200 ng/mL) for 5 minutes (panel A) or with 100 ng/mL IGF-I for times indicated (panels B and C). Cell lysates were resolved on 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Protein was transferred to membranes and blotted with the indicated antibodies. The upper band (**) in panel B designates the phosphorylated form of p85S6 kinase, an isoform of p70S6 kinase.

Effect of IGF-I on p70S6 kinase and GSK3β.

IGF-I induces phosphorylation of p70S6 kinase and GSK3β. H929 cells were cultured in serum-free growth medium for 16 hours and then stimulated with increasing concentrations of IGF-I (1-200 ng/mL) for 5 minutes (panel A) or with 100 ng/mL IGF-I for times indicated (panels B and C). Cell lysates were resolved on 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Protein was transferred to membranes and blotted with the indicated antibodies. The upper band (**) in panel B designates the phosphorylated form of p85S6 kinase, an isoform of p70S6 kinase.

In similar experiments, we examined the status of GSK3β, an additional target of Akt as defined in other systems.24 25IGF-I stimulation resulted in phosphorylation of GSK3β at Ser9 beginning at 1 minute and peaking at approximately 60 minutes (Figure1C). Thus, both p70S6K and GSK3β are rapidly phosphorylated following IGF-I stimulation, and phosphorylation is maintained at maximum levels for at least 1 hour.

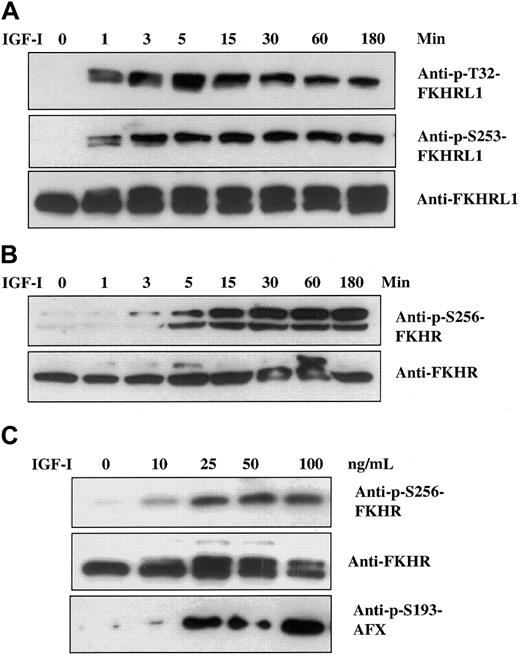

IGF-I induces phosphorylation of the Forkhead family of transcription factors

Recent studies from several laboratories18 26-29 have identified a family of transcription factors (termed Forkhead) that appear to be downstream of Akt and are candidates for playing important roles in both cell proliferation and death. This family is composed of 3 members designated FKHR, FKHRL1, and AFX. We therefore assessed the status of these factors in MM cells. Time course studies revealed that FKHRL1 was rapidly phosphorylated (1 minute) at positions Thr32 and Ser253, with maximum levels attained between 5 and 15 minutes and significant levels remaining for at least 180 minutes (Figure2A). Phosphorylation of FKHR and AFX, the other 2 members of FKHR family, was similarly tested with the use of phospho-specific antibodies recognizing Ser256 in FKHR and Ser193 in AFX. Although, on the basis of the antisera used, the level of FKHR protein appeared lower than the level of FKHRL1, phosphorylated FKHR (Ser256) was detected at 3 minutes, reaching maximum levels by 15 minutes and remaining stable for 180 minutes (Figure 2B). Dose-response curves (Figure 2C) indicated that both FKHR and AFX were phosphorylated at IGF-I concentrations beginning at 10 ng/mL, with maximum effect observed at 25 ng/mL. A similar dose response was found for FKHRL1 (not shown). Thus, all 3 members of the Forkhead family are phosphorylated in a time- and dose-dependent fashion following IGF-I treatment.

Effect of IGF-I on Forkhead transcription factors.

IGF-I induces time- and dose-dependent phosphorylation of Forkhead transcription factors FKHRL1, FKHR, and AFX. H929 cells were cultured in serum-free medium for 16 hours and stimulated with 100 ng/mL IGF-I for indicated times (panels A and B) or increasing concentrations of IGF-I (1 to 100 ng/mL) for 5 minutes (panel C). Cell lysates were analyzed as described in Figure 1 with the use of the antibodies indicated. Anti-FKHRL1 recognizes 2 bands, of which the upper band represents the phosphorylated form.

Effect of IGF-I on Forkhead transcription factors.

IGF-I induces time- and dose-dependent phosphorylation of Forkhead transcription factors FKHRL1, FKHR, and AFX. H929 cells were cultured in serum-free medium for 16 hours and stimulated with 100 ng/mL IGF-I for indicated times (panels A and B) or increasing concentrations of IGF-I (1 to 100 ng/mL) for 5 minutes (panel C). Cell lysates were analyzed as described in Figure 1 with the use of the antibodies indicated. Anti-FKHRL1 recognizes 2 bands, of which the upper band represents the phosphorylated form.

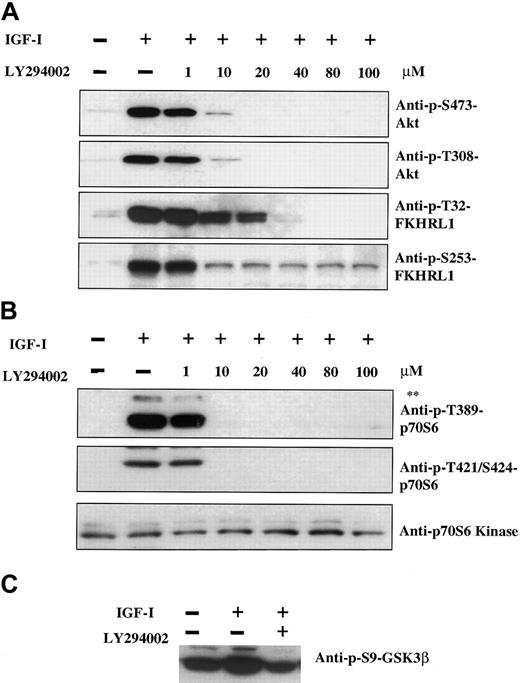

Having identified p70S6 kinase, GSK3β, and the Forkhead family as downstream elements in IGF-I signaling, we next sought to determine whether phosphorylation of these proteins was dependent on the PI-3K/Akt pathway; we did this by employing the PI-3K inhibitor LY294002. As shown in Figure 3A, 100 ng/mL IGF-I induced phosphorylation of Akt at positions Ser473 and Thr308. Phosphorylation was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner, with complete inhibition observed at 20 μM LY294002. Phosphorylation of FKHRL1 at Thr32 was similarly inhibited, although slightly higher concentrations of LY294002 were required. Maximal inhibition of FKHRL1 Ser253 was attained at 10 μM concentration, although complete inhibition was not observed even at higher concentrations. The difference between the effect of LY294002 at these 2 residues raises the possibility that additional pathways activated by IGF-I may contribute to FKHRL1 phosphorylation. In the case of p70S6 kinase (Figure 3B), complete inhibition of phosphorylation was observed at 10-μM concentrations of inhibitor. GSK3β exhibited significant levels of constitutive phosphorylation, which was increased upon IGF-I treatment (Figure 3C). The IGF-I–mediated increase could be inhibited by LY294002, but not the constitutive basal level, indicating that GSK3β is likely to be coregulated by other pathways that are independent of IGF-I.

Pathway by which IGF-I induces phosphorylation of Akt, FKHRL1, p70S6 kinase, and GSK3β.

IGF-I induces phosphorylation of Akt, FKHRL1, p70S6 kinase, and GSK3β via the PI-3K pathway. H929 cells were cultured in serum-free medium for 16 hours and pretreated with increasing concentrations of the PI-3K inhibitor LY294002 (1 to 100 μM) prior to stimulation with IGF-I (100 ng/mL, 5 minutes). Cell lysates were analyzed as described in Figure 1with the use of antibodies indicated. The upper band (**) in panel B represents phosphorylated p85S6 kinase as described in Figure1.

Pathway by which IGF-I induces phosphorylation of Akt, FKHRL1, p70S6 kinase, and GSK3β.

IGF-I induces phosphorylation of Akt, FKHRL1, p70S6 kinase, and GSK3β via the PI-3K pathway. H929 cells were cultured in serum-free medium for 16 hours and pretreated with increasing concentrations of the PI-3K inhibitor LY294002 (1 to 100 μM) prior to stimulation with IGF-I (100 ng/mL, 5 minutes). Cell lysates were analyzed as described in Figure 1with the use of antibodies indicated. The upper band (**) in panel B represents phosphorylated p85S6 kinase as described in Figure1.

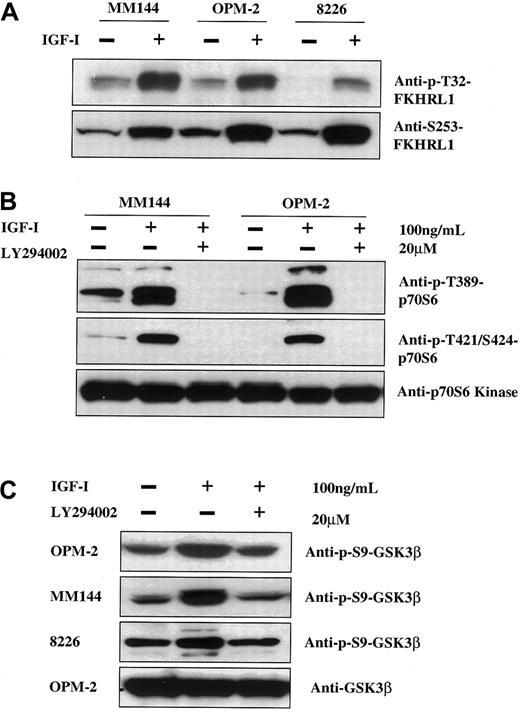

To rule out the possibility that the PI-3K downstream elements identified above were not reflective of myeloma signaling in general, we assessed the ability of IGF-I to phosphorylate these targets in other MM lines. As seen, Forkhead family members (Figure4A), p70S6 kinase (Figure 4B), and GSK3β (Figure 4C) are phosphorylated in an IGF-I–dependent manner in all lines tested. Furthermore, this phosphorylation can be specifically inhibited by LY294002.

IGF-I induction of phosphorylation of FKHRL1, p70S6 kinase, and GSK3β in other MM cell lines.

IGF-I induces phosphorylation of FKHRL1, p70S6 kinase, and GSK3β via the PI-3K pathway in other MM cell lines. Cells from MM144, OPM-2, and RPMI8226 were cultured in media without serum for 16 hours and left untreated (panel A) or treated with the PI-3K inhibitor LY294002 (20 μM) (panels B, C). Cells were then stimulated with IGF-I (100 ng/mL) for 5 minutes and lysates were analyzed as in Figure 1 with the use of the indicated antibodies.

IGF-I induction of phosphorylation of FKHRL1, p70S6 kinase, and GSK3β in other MM cell lines.

IGF-I induces phosphorylation of FKHRL1, p70S6 kinase, and GSK3β via the PI-3K pathway in other MM cell lines. Cells from MM144, OPM-2, and RPMI8226 were cultured in media without serum for 16 hours and left untreated (panel A) or treated with the PI-3K inhibitor LY294002 (20 μM) (panels B, C). Cells were then stimulated with IGF-I (100 ng/mL) for 5 minutes and lysates were analyzed as in Figure 1 with the use of the indicated antibodies.

Pathway cross-talk and regulation of p70S6 kinase

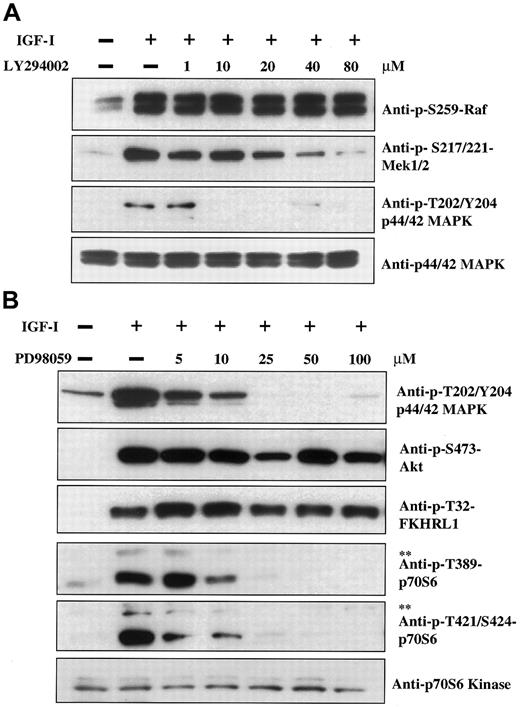

Previous studies13 14 have revealed that IGF-I stimulation activates both the PI-3K and MAPK pathways. We therefore wished to address the question of whether these 2 pathways were involved in cross-regulation and/or coregulation of downstream elements. Experiments were thus performed with the use of LY294002 as an inhibitor of the PI-3K pathway and PD98059 as an inhibitor of the MAPK pathway. IGF-I induces phosphorylation of Raf, Mek1/2, and p44/42 MAPK (Figure 5A, lanes 1 and 2) as expected for the classical MAPK cascade. Surprisingly, treatment with the PI-3K inhibitor LY294002 led to inhibition of Mek1/2 and p44/42 phosphorylation at concentrations of 20 and 10 μM, respectively. Phosphorylation of the upstream element, Raf, was not affected. Thus, the PI-3K pathway is capable of regulating activation of elements in the MAPK pathway, and such regulation appears to occur at the level of Mek kinase. Cross-talk between these pathways is unidirectional as the Mek kinase inhibitor PD98059, which effectively inhibits p44/42 MAPK phosphorylation (Figure 5B, upper panel), does not affect phosphorylation of PI-3K pathway components Akt and FKHRL1 (Figure 5B, second and third panels). It was further observed that, in addition to this cross-talk, PD98059 inhibited phosphorylation of p70 and p85S6 kinases in a dose-dependent manner beginning at concentrations in the 5 to 10 μM range. As we demonstrated above (Figure 3) that p70S6 kinase phosphorylation is inhibited by the PI-3K inhibitor LY294002, these results indicate that p70S6 kinase can be regulated by both pathways.

Cross-talk between the PI-3K and MAPK pathways and MAPK regulation of p70S6 kinase.

H929 cells were cultured in serum-free medium for 16 hours followed by treatment for 1 hour with increasing concentrations of the PI-3K inhibitor LY294002 (panel A) or the MAPK (Mek1/2) inhibitor PD98059 (panel B). Cells were then stimulated with IGF-I (100 ng/mL, 5 minutes) and lysates were analyzed as described in Figure 1 by use of the indicated antibodies. The upper band (**) in panel B designates phosphorylated p85S6 kinase as described in Figure 3.

Cross-talk between the PI-3K and MAPK pathways and MAPK regulation of p70S6 kinase.

H929 cells were cultured in serum-free medium for 16 hours followed by treatment for 1 hour with increasing concentrations of the PI-3K inhibitor LY294002 (panel A) or the MAPK (Mek1/2) inhibitor PD98059 (panel B). Cells were then stimulated with IGF-I (100 ng/mL, 5 minutes) and lysates were analyzed as described in Figure 1 by use of the indicated antibodies. The upper band (**) in panel B designates phosphorylated p85S6 kinase as described in Figure 3.

Biological associations with signaling pathways

While the above, and previous, data have defined a number of components in the MAPK and PI-3K pathways, little is known about the contributions of these pathways, and particular elements therein, to the regulation of proliferation and/or cell death in myeloma cells. We addressed this issue by the use of kinase inhibitors employing both MTT and [3H]-thymidine incorporation assays as indicators of proliferation. Treatment of myeloma cells with IGF-I led to significant proliferation (P < .001) in both assays (Figure6), and the effects of the different inhibitors were also consistent between assays. The PI-3K inhibitor LY294002, had, by far, the most pronounced effect on proliferation in either assay, resulting in inhibition in the range of 70% to 75%. Rapamycin, an inhibitor of p70S6 kinase, was also effective, inhibiting proliferation by approximately 40%. Treatment with the MAPK inhibitor PD98059 produced only marginal and statistically not significant effects. These results suggest that the PI-3K pathway is the major effector of myeloma cell proliferation and that p70S6 kinase in this cascade regulates, to a considerable extent, the ultimate effect of IGF-I.

IGF-I–induced proliferation and the PI-3K pathway.

IGF-I–induced proliferation is predominantly associated with the PI-3K pathway. H929 cells were starved for 2 hours in serum-free growth media followed by treatment with the PI-3K inhibitor LY294002 (10 μM), the MAPK inhibitor PD98059 (50 μM), or the p70S6 kinase inhibitor rapamycin (10 nM). Cells were then seeded at 3 × 104 per well in 96-well plates in serum-free media with or without 100 ng/mL IGF-I for 24, 48, or 72 hours. Proliferation was measured by MTT assay (panel A). DNA synthesis was also measured by [3H]-thymidine uptake at 48 hours following treatment as above (panel B). Results are presented as mean ± SE (n = 4). Data are representative of 3 separate experiments. *P < .01 versus control. **P < .001 versus control.

IGF-I–induced proliferation and the PI-3K pathway.

IGF-I–induced proliferation is predominantly associated with the PI-3K pathway. H929 cells were starved for 2 hours in serum-free growth media followed by treatment with the PI-3K inhibitor LY294002 (10 μM), the MAPK inhibitor PD98059 (50 μM), or the p70S6 kinase inhibitor rapamycin (10 nM). Cells were then seeded at 3 × 104 per well in 96-well plates in serum-free media with or without 100 ng/mL IGF-I for 24, 48, or 72 hours. Proliferation was measured by MTT assay (panel A). DNA synthesis was also measured by [3H]-thymidine uptake at 48 hours following treatment as above (panel B). Results are presented as mean ± SE (n = 4). Data are representative of 3 separate experiments. *P < .01 versus control. **P < .001 versus control.

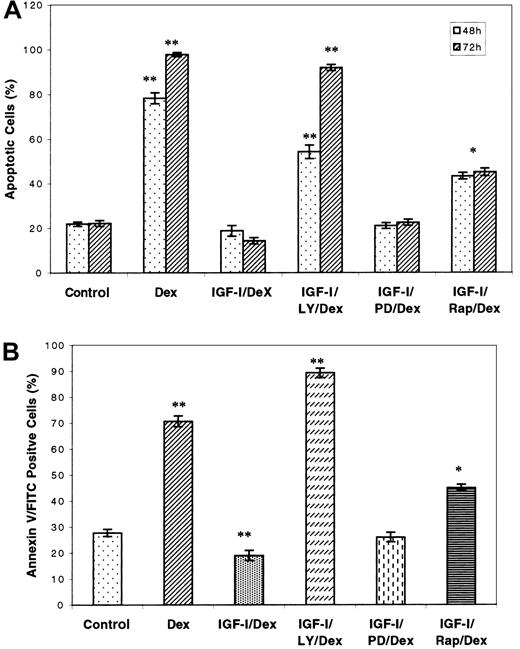

LY294002 and rapamycin inhibit IGF-I rescue of Dex-induced apoptosis

As the growth of tumor cells is the sum of the effects of proliferation and cell death, we used the same inhibitors to assess the contribution of the respective pathways to apoptosis by means of both trypan blue and annexin V staining. It has been reported that IGF-I protects MM cells against Dex-induced apoptosis, but the mechanism by which this occurs is unclear.30 As shown in Figure7, incubation of H929 cells with 1 μM Dex caused readily induced apoptosis, which was completely reversed by IGF-I treatment as determined by either assay. However, pretreatment of cells with the PI-3K inhibitor LY294002 completely abolished the protective effect of IGF-I. Rapamycin treatment inhibited IGF-I protection by approximately 20% to 30%. PD98059, the MAPK inhibitor, did not suppress IGF-I rescue. These results suggest that activation of the PI-3K, but not MAPK pathway, is the mechanism by which IGF-I prevents Dex-induced apoptosis in MM cells. Furthermore, p70S6 kinase is at least partly responsible for this effect.

PI-3K pathway and the IGF-I–mediated rescue of Dex-induced apoptosis.

The PI-3K pathway is responsible for IGF-I–mediated rescue of Dex-induced apoptosis. Cells were starved for 1 hour and incubated in growth media with or without the PI-3K inhibitor LY294002 (10 μM), the MAPK inhibitor PD98059 (50 μM), or the p70S6 kinase inhibitor rapamycin (10 nM) for 1 hour. Culture was then continued in the presence or absence of 100 ng/mL IGF-I for 1 hour, after which Dex or control media were added to yield a final 1 μM Dex concentration. Dead cells were enumerated after 48 or 72 hours by trypan blue exclusion (panel A). Similarly treated cells were stained with annexin V and propidium iodide after incubation for 36 hours and then examined by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) (panel B). Results are presented as mean ± SE (n = 3). Data are representative of 3 separate experiments. *P < .01 versus control. **P < .001 versus control.

PI-3K pathway and the IGF-I–mediated rescue of Dex-induced apoptosis.

The PI-3K pathway is responsible for IGF-I–mediated rescue of Dex-induced apoptosis. Cells were starved for 1 hour and incubated in growth media with or without the PI-3K inhibitor LY294002 (10 μM), the MAPK inhibitor PD98059 (50 μM), or the p70S6 kinase inhibitor rapamycin (10 nM) for 1 hour. Culture was then continued in the presence or absence of 100 ng/mL IGF-I for 1 hour, after which Dex or control media were added to yield a final 1 μM Dex concentration. Dead cells were enumerated after 48 or 72 hours by trypan blue exclusion (panel A). Similarly treated cells were stained with annexin V and propidium iodide after incubation for 36 hours and then examined by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) (panel B). Results are presented as mean ± SE (n = 3). Data are representative of 3 separate experiments. *P < .01 versus control. **P < .001 versus control.

Role of Forkhead transcription factors in myeloma cell growth

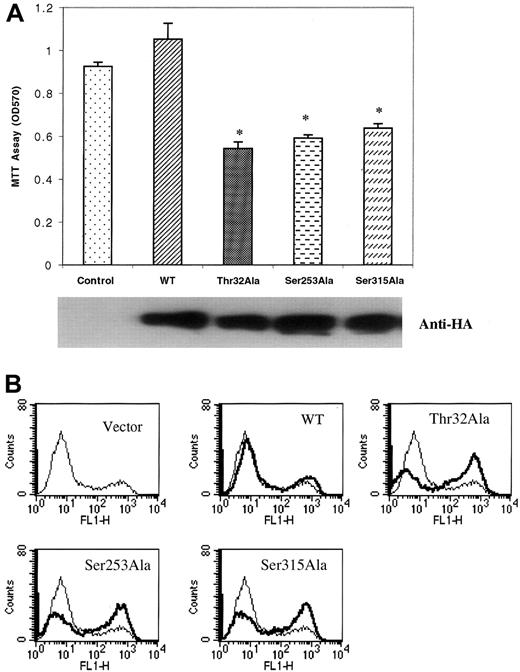

As shown in Figure 2, the Forkhead transcription factors are downstream elements in the PI-3K pathway. To examine the biological role of these proteins, we selected the most abundantly expressed member of this family, FKHRL1, to assess contributions to both proliferation and apoptosis. For these experiments, we expressed in myeloma cells wild-type (WT) and 3 FKHRL1 mutants, Thr32Ala, Ser253Ala, and Ser315Ala, in which the threonine or serine phosphorylation site was replaced by an alanine residue. Mutant constructs were HA tagged and readily detected by anti-HA antibodies in transfected cells (Figure8A). An MTT proliferation assay (Figure8A) revealed that expression of WT FKHRL1 had little effect on IGF-I–mediated proliferation (a small but statistically not significant increase was noted). However, each of the 3 mutants produced a significant decrease in proliferative response. To examine the role of FKHRL1 in apoptosis, the same transfected lines were evaluated for their effect on IGF-I protection from Dex-induced apoptosis. As seen in Figure 8B, IGF-I protected against apoptosis (vector control), and apoptosis was only slightly increased in the wild-type tranfectant. However, cells expressing each of the phosphorylation site mutants demonstrated marked increases in apoptosis (average, 23%), indicating an ability to counteract the protective effect of IGF-I. Thus, the FKHRL1 mutants all produced a dual effect in that they inhibited proliferation and increased apoptosis.

Effect of mutant FKHRL1.

Expression of mutant FKHRL1 inhibits proliferation and IGF-I rescue of Dex-induced apoptosis. (A) Effect of expression of mutant FKHRL1 on proliferation of H929 cells. Cell clones expressing PFB vector (Control), PFB-FKHRL1-WT (WT), PFB-FKHRL1-Thr32Ala (Thr32Ala), PFB-FKHRL1-Ser253Ala (Ser253Ala), or PFB-FKHRL1-Ser315Ala (Ser315Ala) were cultured in serum-free media containing 100 ng/mL IGF-I for 48 hours. Proliferation was assessed by MTT assay. Results are presented as mean ± SE (n = 4). Data are representative of 3 separate experiments. *P < .01. Expression of the various constructs was confirmed by blotting with antibodies to the HA tag. (B) Effect of expression of mutant FKHRL1 on IGF-I rescue of Dex-induced apoptosis. H929 clones, indicated as above, were pretreated with 100 ng/mL IGF-I for 1 hour followed by incubation with 1 μM Dex for an additional 36 hours. Cells were stained with annexin V and propidium iodide. Apoptotic cells were enumerated by FACS analysis.

Effect of mutant FKHRL1.

Expression of mutant FKHRL1 inhibits proliferation and IGF-I rescue of Dex-induced apoptosis. (A) Effect of expression of mutant FKHRL1 on proliferation of H929 cells. Cell clones expressing PFB vector (Control), PFB-FKHRL1-WT (WT), PFB-FKHRL1-Thr32Ala (Thr32Ala), PFB-FKHRL1-Ser253Ala (Ser253Ala), or PFB-FKHRL1-Ser315Ala (Ser315Ala) were cultured in serum-free media containing 100 ng/mL IGF-I for 48 hours. Proliferation was assessed by MTT assay. Results are presented as mean ± SE (n = 4). Data are representative of 3 separate experiments. *P < .01. Expression of the various constructs was confirmed by blotting with antibodies to the HA tag. (B) Effect of expression of mutant FKHRL1 on IGF-I rescue of Dex-induced apoptosis. H929 clones, indicated as above, were pretreated with 100 ng/mL IGF-I for 1 hour followed by incubation with 1 μM Dex for an additional 36 hours. Cells were stained with annexin V and propidium iodide. Apoptotic cells were enumerated by FACS analysis.

Discussion

A critical element to the understanding of myeloma development is elucidation of growth factors and their associated biochemical pathways that promote either growth or survival. Substantial attention has been focused on the role of IL-6 in plasma cell neoplasia.1-3However, it has become apparent that myeloma cells respond to a variety of growth factors that may play important roles in disease progression.31 A number of studies have suggested that IGF-I may play such a role both in vitro11-13 and in vivo.13,32 It appears as if virtually all myeloma lines proliferate in response to IGF-I and that this growth factor also produces an antiapoptotic effect. In combination, these 2 responses clearly provide a growth and survival advantage to developing tumor cells. It should be noted that myeloma cells are constantly exposed to IGF-I as this factor is synthesized by the liver and found throughout the circulation as well as produced by osteoblasts in the bone marrow matrix.31 33

An assessment of the mechanisms by which factors such as IGF-I stimulate myeloma cells is clearly critical both to an understanding of the biology of this disease and to providing a basis for novel therapeutic approaches. Recent studies from several laboratories12-14,16 have begun to analyze the biochemical pathways associated with IGF-I signaling. It is clear that IGF-I stimulation leads to activation of both the MAPK and PI-3K cascades. Several elements of the PI-3K pathway, including the PTEN tumor suppressor gene, Akt kinase, and Bad, have been demonstrated to affect myeloma cell growth both in vitro and in vivo.17 However, additional elements downstream in these cascades and their functions in either proliferation or apoptosis have yet to be defined. Here, we have described experiments in which a number of downstream targets have been identified and functional correlates established for both MAPK and PI-3K pathways. Three elements downstream of Akt in the PI-3K pathway, p70S6 kinase, GSK3β (Figure1), and the Forkhead family of transcription factors (Figure 2), were all shown to be phosphorylated following IGF-I stimulation in a PI-3K/Akt–dependent manner as determined by use of specific PI-3K inhibitors (Figure 3). Phosphorylation of these targets is general among myeloma lines and could be demonstrated in multiple examples (Figure 4).

Phosphorylation of GSK3β leads to a reduction in activity that normally involves suppression of glycogen synthase and thus allows cells to complete glycogen synthesis.24,25 This process is key to metabolic regulation and may also be important to tumor cell growth as nutrients are depleted. In contrast, phosphorylation of p70S6 kinase leads to activation and subsequent phosphorylation of the 40S ribosomal subunit, resulting in stimulated protein synthesis.22 The Forkhead family of transcription factors is composed of 3 members, FKHR, FKHRL1, AFX, which exhibit DNA-binding activity and have been identified as substrates for phosphorylation by Akt.18,26-29 These genes were originally identified in chromosomal translocations associated with human rhabdomyosarcomas. FKHR is the mammalian counterpart of DAF-16, a member of the signaling pathway downstream of the homolog of the IGF-I receptor inCaenorhabditis elegans.34 DAF-16 has been shown to play an important role in life-span determination, suggesting that the Forkhead family may function as regulators of cell growth and survival. In fact, it has been shown that FKHRL1 contributes to cell growth and survival response to growth-factor stimulation.18,35 In the absence of growth factor, unphosphorylated Forkhead proteins translocate to the nucleus and activate target genes that inhibit cell cycle progression through the G0/G1 phase36 and induce apoptosis by activating Fas ligand.18 Upon activation of the PI-3K/Akt pathway by certain growth factors, Forkheads become phosphorylated, leading to retention in the cytoplasm and binding to 14-3-3 proteins.37 As a result, activation of target genes is prevented, resulting in both a proliferative and an antiapoptotic effect. All 3 members of the Forkhead family are expressed in myeloma cells (although FKHRL1 appears to be the most abundant) and are phosphorylated upon IGF-I stimulation at all sites for which specific antibodies are available. In the case of FKHRL1, complete inhibition of phosphorylation by LY294002 was observed at Thr32, but not at Ser253. This result suggests that Ser253 may be phosphorylated by additional kinase(s) independent of Akt. This premise is supported by the observation that kinase-dead Akt did not completely block the IGF-I–induced phosphorylation of FKHRL1 at Ser253 in PC12 cells.38 It is likely that Ser315 is also phosphorylated, as phosphorylation at this site has been associated with appearance of the slower moving band (Figure 2A, panel 3) following growth-factor stimulation.18 35

Use of inhibitors specific for either the MAPK or PI-3K pathways clearly demonstrated (Figure 5) that inhibition of the MAPK pathway had no effect on Akt or Forkhead phosphorylation, whereas phosphorylation of both was abrogated by PI-3K inhibition (Figure 4). Somewhat surprisingly, treatment of cells with the PI-3K inhibitor LY294002 resulted in inhibition of phosphorylation of the MAPK pathway element Mek1/2 and its downstream target p44/42 MAPK, demonstrating cross-talk resulting in regulation of the MAPK pathway by PI-3K. Raf, immediately upstream of Mek1/2, did not exhibit inhibition of phosphorylation, suggesting that the effect was at the level of Mek1/2. Studies in other cell types have previously suggested the possibility of such cross-talk. For example, overexpression of the p110γ subunit of PI-3K led to activation of p44/42 MAPK.39,40Furthermore, inhibition of PI-3K by pharmacological inhibitors in Cos cells stimulated with epidermal growth factor41 or lysophosphatidic acid42 or in L6 cells stimulated with insulin43 resulted in inhibition of MAPK activity. However, such cross-inhibition was not observed in all cell types. The present results demonstrate direct regulation of the MAPK pathway at the level of Mek1/2 in myeloma cells by PI-3K. This cross-talk is unidirectional as the MAPK inhibitor PD98059 failed to impair phosphorylation of Akt or FHHRL1. However, PD98059 completely inhibited phosphorylation of p70S6 kinase at concentrations between 10 and 25 μM (Figure 5). This result appears to explain conflicting data in the literature in which activated MAP kinase was reported to directly phosphorylate p70S6K in vitro44 but upstream mutants of Raf or Ras could not block activation.45 As p70S6 phosphorylation was also blocked by PI-3K inhibition at similar concentrations, these findings further indicate that p70S6 can be regulated by both pathways.

While it is known that IGF-I activates both MAPK and PI-3K pathways in myeloma cells, to date there exists minimal experimental evidence to indicate their specific involvement in proliferation and/or apoptosis. The PI-3K/Akt pathway, through phosphorylation of Bad and subsequent modulation of caspase activity, has been suggested to be a regulator of apoptosis.13 However, little is known about additional apoptotic regulators in this pathway or its possible link to proliferative activity. Proliferative effects have, in general, been presumed to be linked to the MAPK pathway. To address these questions, a series of kinase inhibitors were employed in both proliferation and apoptosis assays. Results from both MTT and thymidine incorporation assays (Figure 6) revealed that inhibition of the PI-3K pathway reduced proliferation approximately 70% to 75%, whereas inhibition of the MAPK pathway reduced proliferation by 10% or less (not statistically significant). This finding suggests that the PI-3K pathway is the major effector of IGF-I–mediated proliferation in myeloma cells. Furthermore, the observation of cross-talk in which PI-3K regulates MAPK activity would indicate that inhibition of the PI-3K pathway would also prevent any proliferation associated with MAPK activity. The ability of rapamycin, an inhibitor of p70S6 kinase, to significantly reduce proliferation further suggests that protein synthesis is an important factor in achieving maximal response. The role of p70S6 kinase in regulating aspects of proliferation appears to be complex. Since PI-3K regulates phosphorylation of this enzyme, it is not surprising that PI-3K inhibitors would reduce proliferation to at least the same extent as rapamycin. However, as noted above, inhibition of MAPK also prevents phosphorylation of p70S6 kinase, yet proliferation is not reduced to the same extent as with rapamycin alone. We find no obvious explanation for the differing effects of the 2 inhibitors acting through separate pathways on the same target, though a number of possibilities can be considered. First, it is possible that PI-3K inhibition results in additional effects that impair protein translation or other functions downstream of p70S6 kinase and are unique to this pathway. Second, inhibition of phosphorylation may not strictly correlate with inhibition of activity. Third, rapamycin may inhibit protein synthesis or other pathways through mechanisms not involving p70S6 phosphorylation.

Modulation of proliferation was also linked to IGF-I–mediated phosphorylation of the Forkhead transcription factor FKHRL1 (Figure8A). Phosphorylation of FKHRL1 leads to sequestration in the cytoplasm and prevents down-regulation of cell cycle progression. Transfection of mutated FKHRL1 in which each of the 3 potential phosphorylation sites had been altered (one per construct) resulted in significant decreases in proliferation with each. It thus appears that removal of any of the 3 phosphorylation sites is sufficient to prevent sequestration to a large enough extent that the normal effect of cell cycle down-regulation occurs, as reflected by a decrease in proliferation. Thus, the Forkhead family is likely to play a significant role in regulating growth of myeloma cells.

To examine the other major contribution to overall cell growth, namely cell death, we took advantage of previous studies demonstrating that Dex induced myeloma cell death that could be prevented by IGF-I.30 Using the same set of kinase inhibitors, we examined their abilities to prevent IGF-I–mediated rescue of Dex-induced apoptosis (Figure 7). The PI-3K inhibitor LY294002 was able to completely block IGF-I rescue, whereas the MAPK inhibitor had no effect. Rapamycin partially (approximately 20%) negated the IGF-I rescue, indicating that protein synthesis is likely to play a role in the ability of IGF-I to prevent apoptosis. Analysis of the FKHRL1 mutants (Figure 8B) revealed that each increased apoptosis by approximately 23%. Thus, as was observed in the proliferative response, alteration of a single phosphorylation site was sufficient to allow induction of apoptosis-promoting genes.

The above studies have identified a series of downstream targets in the PI-3K pathway, including GSK3β, p70S6 kinase, and the 3 members of the Forkhead family of transcription factors. Biological correlates to proliferation and apoptosis were established for both p70S6 kinase and the Forkhead family member FKHRL1, revealing important roles in both of these processes. Interestingly, the PI-3K pathway was demonstrated to be the major regulator of both proliferation and apoptosis, with only minimal contributions to either by the MAPK cascade. This result is in agreement with a previous study indicating that insulin-induced activation of MAPK in cerebellar granule cells could be completely blocked by PD98059 with no effect on survival.46 Thus, the PI-3K pathway may be a key regulator of myeloma cell growth, and targeting of this pathway may be an important consideration in therapeutic approaches. The understanding gained from analyses such as these is critical to an appreciation of the biology of myeloma development and provides new insights into the regulation of neoplastic growth.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Stuart Rudikoff, Laboratory of Cellular and Molecular Biology, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD 20892-4255; e-mail: rudikoff@helix.nih.gov.

![Fig. 6. IGF-I–induced proliferation and the PI-3K pathway. / IGF-I–induced proliferation is predominantly associated with the PI-3K pathway. H929 cells were starved for 2 hours in serum-free growth media followed by treatment with the PI-3K inhibitor LY294002 (10 μM), the MAPK inhibitor PD98059 (50 μM), or the p70S6 kinase inhibitor rapamycin (10 nM). Cells were then seeded at 3 × 104 per well in 96-well plates in serum-free media with or without 100 ng/mL IGF-I for 24, 48, or 72 hours. Proliferation was measured by MTT assay (panel A). DNA synthesis was also measured by [3H]-thymidine uptake at 48 hours following treatment as above (panel B). Results are presented as mean ± SE (n = 4). Data are representative of 3 separate experiments. *P < .01 versus control. **P < .001 versus control.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/99/11/10.1182_blood.v99.11.4138/6/m_h81122649006.jpeg?Expires=1769336110&Signature=B47wS7tX5t-XKhIMR1BRLSePBBv2L5lec9livA2xtj-Uy3XpxF5l0-SU-jKTM0uueSTefgz5Lm8uAX4BMvNGqHdVhXuvLWVk6LfJLSpEauTC2j5f3Axz349YtkmKnTelQHf2XIC7dYgLeg7gr1bRBAuMQVvbllIY9Jpnadw3P2eflgeoCl6mh1PT3ftWRE3sCNndG8gBNvtV1b7JJ~2b3NJUBIFDmmTEdCU1YwfxYkq1me52BT6kj8MVHsaXUUwAsszCvT0pFBMOHFyCmNmiD0O9t4oo6keAGQbl9qbrZ2dKuejfbmq~KBp8leiPP8Ev6nA2oyfZr4f6I1s9q~dqWw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal