CD2+ T lymphocytes obtained from either the donor of bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) or a third party were cultured in mixed lymphocyte reactions (MLRs) with either allogeneic dendritic cells (DCs) or peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs). When autologous or allogeneic BMSCs were added back to T cells stimulated by DCs or PBLs, a significant and dose-dependent reduction of T-cell proliferation, ranging from 60% ± 5% to 98% ± 1%, was evident. Similarly, addition of BMSCs to T cells stimulated by polyclonal activators resulted in a 65% ± 5% (P = .0001) suppression of proliferation. BMSC- induced T-cell suppression was still evident when BMSCs were added in culture as late as 5 days after starting of MLRs. BMSC-inhibited T lymphocytes were not apoptotic and efficiently proliferated on restimulation. BMSCs significantly suppressed both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (65% ± 5%, [P = .0005] and 75% ± 15% [P = .0005], respectively). Transwell experiments, in which cell-cell contact between BMSCs and effector cells was prevented, resulted in a significant inhibition of T-lymphocyte proliferation, suggesting that soluble factors were involved in this phenomenon. By using neutralizing monoclonal antibodies, transforming growth factor β1 and hepatocyte growth factor were identified as the mediators of BMSC effects. In conclusion, our data demonstrate that (1) autologous or allogeneic BMSCs strongly suppress T-lymphocyte proliferation, (2) this phenomenon that is triggered by both cellular as well as nonspecific mitogenic stimuli has no immunologic restriction, and (3) T-cell inhibition is not due to induction of apoptosis and is likely due to the production of soluble factors.

Introduction

Bone marrow is a complex tissue containing hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and their progeny in close contact with a connective tissue network of stromal cells constituting the bone marrow microenvironment.1 Bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) comprise a multifunctional tissue consisting of heterogeneous cell populations that provide a specialized microenvironment for controlling the process of hematopoiesis.2

BMSC progenitors can be readily isolated from bone marrow and expanded ex vivo without any apparent modification in phenotype or loss of function.3 Purified and culture-expanded human stromal stem cells differentiate along the osteogenic, chondrogenic, myogenic, and adipogenic lineages both in vitro4-8 and in vivo.9,10 BMSCs constitutively secrete regulatory molecules and cytokines that stimulate and enhance the proliferation of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells.11

When reinfused in nonhuman models, ex vivo–expanded BMSCs migrate to and become incorporated into several tissues of the recipient animals where BMSCs are capable to elicit tissue-specific differentiation programs indicating that, similarly to hematopoietic stem cells, BMSCs have multiorgan homing capacity and an intrinsic degree of plasticity.12,13 On the basis of this peculiar functional activity, BMSCs may be used either to replace marrow microenvironment damaged by myeloablative chemotherapy or to correct acquired or inherited disorders of bone, muscle, or cartilage or used as vehicles for gene therapy.14,15 Furthermore, the importance of marrow microenvironment has been highlighted by the demonstration that the developmental potential of hematopoietic stem cells could be reprogrammed by changing their microenvironment.16

Overall, these findings strongly support a crucial role of BMSCs in improving the rate and quality of myeloid as well as lymphoid engraftment after lympho-myeloablative and stroma-damaging treatment. Thus, BMSCs seem to play a key role in regulating the maturation and proliferation as well as functional activation of lymphocytes.17-20 With the use of a murine model, Li et al21 have recently demonstrated that donor-derived BMSCs can migrate into the thymus and participate in the positive selection of T lymphocytes after bone marrow transplantation (BMT) plus bone grafts. It, therefore, seems that BMSCs may provide a scaffold for the adhesion of early T cells and, at least in culture, supply the appropriate stimuli for thymus precursor cell proliferation.22 It has been reported that the injection of genetically modified BMSCs in baboon is not followed by their rejection because of the lack of immunogenicity of BMSCs.23 Indeed, the distinct immunophenotype profile of BMSCs, ie, low expression of costimulatory molecules associated with the absence of HLA class II expression,24 25 suggests they may play an active role in modulating T-cell proliferation.

In the present study, we evaluated the inhibitory activity of BMSCs added to mixed lymphocyte reactions (MLRs) involving autologous or allogeneic T cells and third-party peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Furthermore, we tested the inhibitory effect of BMSCs by using dendritic cells (DCs) as stimulators, because these cells are considered professional antigen-presenting cells capable of modulating T-lymphocyte activation. In addition, the mechanism(s) underlying BMSC-mediated suppression of T-lymphocyte proliferation was investigated by evaluating (1) the role of cell-cell contact, (2) the capacity of monoclonal antibodies neutralizing distinct cytokines to restore T-cell proliferation, and (3) BMSC-induced T-cell apoptosis.

Materials and methods

Human BMSCs

Normal human bone marrow mononuclear cells (1-3 × 106/mL) resuspended in alpha-medium (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with fetal bovine serum (12.5%), horse serum (12.5%), L-glutamine (2 mM), 2-mercaptoethanol (0.1 mM), inositol (0.2 mM), folic acid (0.02 mM), and freshly dissolved hydrocortisone (0.001 mM) were inoculated into 175-cm2tissue culture flasks and incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere supplemented with 5% CO2. The cultures were fed by complete replacement of complete alpha-medium on a weekly basis. Confluent stromal layers were trypsinized for at least 3 consecutive weeks to ensure the substantial depletion of monocyte macrophages, which was tested by flow cytometry analysis by using an anti-CD14 monoclonal antibody.

Human T lymphocytes

Human T lymphocytes (CD2+ cell purity of 96% ± 2%) were isolated from the buffy-coat of healthy donors by means of a MiniMACS high-gradient magnetic CD2+ cell sorting system (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergish Gladbach, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. To evaluate the inhibition by BMSCs on T-lymphocyte subpopulations, we also isolated CD4+and CD8+ T lymphocytes from the buffy-coat of healthy donors (n = 3) by using a MiniMACS high-gradient magnetic sorting system (Miltenyi Biotec). CD4+ and CD8+ cell purity was 97% ± 2% and 96% ± 3%, respectively. Each subpopulation was used instead of CD2+ cells in the proliferative assay described below.

Stimulators

Human DCs were generated ex vivo from highly purified mobilized CD34+ cells after 10 to 12 days' culture in complete medium consisting of 10% recovery-phase autologous serum Iscoves modified Dulbecco media supplemented with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (50 ng/mL), tumor necrosis factor α (10 ng/mL), stem cell factor (50 ng/mL), andflk-2/flt-3 ligand (50 ng/mL). Peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) were obtained by means of the Ficoll-Hypaque (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) gradient separation of the buffy-coat of healthy donors. Both cell populations were irradiated with 30 Gy before use.

Cell surface phenotype

Marrow stromal cells detached using trypsin/EDTA were washed and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline supplemented with human serum (1%), fetal bovine serum (1%), and mouse serum (10%). BMSCs (1 × 105/mL) were then stained for 30 minutes on ice with combinations of saturating amounts of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated or phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated monoclonal antibodies. Fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies recognizing CD45, CD44, CD50, CD90, and HLA-ABC were purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA); the FITC- or PE-conjugated antibodies against CD13, CD14, and HLA-DR were purchased from Becton Dickinson (San Jose, CA,); CD106 was obtained from Southern Biotechnology Associates (Birmingham, AL). Each fluorescence analysis included appropriate PE- and FITC-conjugated negative isotype controls. The percentage of positive cells was determined by subtracting the percentage of fluorescent cells in the control from the percentage of cells positively stained with the appropriate antibody. The cells were analyzed by using a FACScan laser flow cytometry system (Becton Dickinson) equipped with a Macintosh PowerMac G3 personal computer (Apple Computer, Cupertino, CA) and Cell Quest (Becton Dickinson) software.

Mixed leukocyte reactions

BMSCs and stimulators were irradiated (30 Gy) before being cultured with the T lymphocytes. CD2+ cells (5 × 104) were mixed at different stimulator-to-responder ratios with PBLs or DCs with or without BMSCs in V-bottomed 96-well culture plates to ensure efficient cell-cell contact for 7 days in 0.2 mL modified RPMI-1640 medium (GIBCO BRL) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum. T-cell proliferation was measured on day 6 by means of an 18-hour pulse with3H-thymidine (3H-TdR) (0.037 MBq/well [1 μCi/well], specific activity 24.79 × 1010Bq/mmol [6.7 Ci/mmol]) (Amersham, Buckingham, United Kingdom).3H-TdR incorporation was measured by using a liquid scintillation counter (Betaplate, Wallac, Boston, MA). The data are presented as stimulation index values calculated by using the following formula: proliferation of T lymphocytes incubated with cellular or aspecific polyclonal activators with or without BMSCs/proliferation of T lymphocytes alone. The experiments were performed by using either autologous or allogeneic BMSCs with respect to CD2+ cells. In addition, phytohemagglutinin (PHA; 2 μg/mL) or interleukin 2 (IL-2; 500 U/mL) was used instead of PBLs or DCs to induce T-cell proliferation. The experiments were performed at least 3 times for each point described.

Restimulation of T lymphocytes following culture with BMSCs

To evaluate whether or not BMSC-induced inhibition of T-cell function was reversible, T lymphocytes were initially incubated for 7 days with irradiated BMSCs and either irradiated DCs or PHA. T cells were then harvested by Fycoll-Hypaque centrifugation and cultured with the same stimulators as those used for the primary culture. After 48 hours, the cells were pulsed with 3H-TdR for a further 18 hours. 3H-TdR incorporation was measured and expressed as cpm and represents the mean of 6 separate replicates; the SE never exceeded 9% of the mean.

Transwell cultures

Transwell chambers with a 0.3-μm pore size membrane (Corning Costar, Cambridge, MA) were used to separate the lymphocytes and stimulators physically from the BMSCs. Lymphocytes at 10 × 105 cells/well were cocultured with 2 × 105 irradiated DCs or PHA (2 μg/mL), whereas autologous or allogeneic BMSCs at 10 × 106 cells/well were placed in the inner transwell chamber. After 5 days of culture, the CD2+ cells were harvested, plated at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells/well in 96-well plates, and pulsed with3H-TdR for a further 18 hours.

Cytokines inhibiting T-lymphocyte proliferation

To identify soluble factors responsible for the inhibitory effect of BMSCs, neutralizing monoclonal antibodies directed against cytokines that are known to be produced by BMSCs were added in MLRs containing T cells (5 × 104), irradiated PBLs (5 × 104), and/or irradiated third-party BMSCs (5 × 104). In these experiments, positive controls included MLRs set up with T cells and irradiated PBLs with or without neutralizing monoclonal antibodies. In addition, MLRs were set up that contained T cells, irradiated PBLs, and the appropriate cytokines. The following recombinant human (rh) cytokines and neutralizing monoclonal antibodies were used: transforming growth factor-β1 (rhTGF-β1; Genzyme, Cambridge, MA; 0.1-1 μg/mL) and monoclonal antibody anti–rhTGF-β1 (R&D System, Minneapolis, MN; 0.1-1 μg/mL), hepatocyte growth factor (rhHGF; R&D System; 0.25-2.5 μg/mL) and monoclonal antibody anti-rhHGF (R&D System; 0.25-2.5 μg/mL), interleukin-6 (rhIL-6; PromoCell GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany; 1-5 μg/mL) and monoclonal antibody anti–rhIL-6 (R&D System; 1-5 μg/mL), interleukin-11 (rhIL-11, StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada; 25-50 μg/mL) and monoclonal antibody anti–rhIL-11 (R&D System; 25-50 μg/mL).

Determination of the percentage of apoptotic T lymphocytes

The percentage of apoptotic T lymphocytes after 7 days' culture with the above-mentioned stimulators (with or without BMSCs) was evaluated by using the annexin V/propidium iodine (PI) staining technique (Bender; MedSystems Diagnostics GmbH, Vienna, Austria) or double staining with CD3 monoclonal antibody (Becton Dickinson) and PI, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Furthermore, on the basis of experimental evidence concerning the expression of CD10 by human T cells that undergo apoptosis,26 the percentage of T lymphocytes expressing the CD10 antigen (Becton Dickinson) was evaluated by means of flow cytometry analysis after they had been cultured with stimulators in the presence of BMSCs.

Statistical analysis

The results were statistically analyzed by using the Statview statistical package (BrainPower, Calabasas, CA) run on a Macintosh PowerMac G3 personal computer (Apple Computer). The Studentt test for paired data (2-tail) was used to test the probability of significant differences between samples.

Results

T-cell proliferation is inhibited by cocultivation with BMSCs

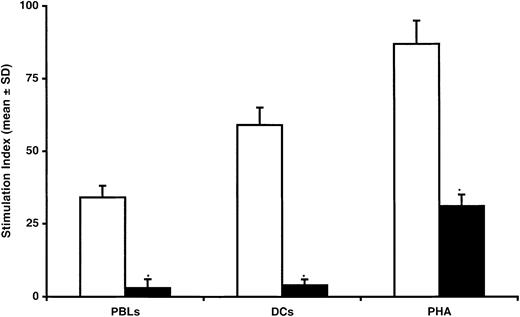

BMSCs were generated by culturing marrow-derived mononuclear cells (MNCs) in a Dexter-type culture system. After 2 to 3 weeks of incubation, marrow cells gave rise to a confluent stromal cell layer. At confluence, marrow stroma cells were passaged and replated at low density. After 3 passages, stroma cells were negative for the expression of CD45, CD14, CD34, CD50, and HLA-DR but expressed HLA-ABC, CD44, CD13, and CD90 (data not shown). The effect of BMSCs on T-cell proliferation was evaluated by mixing BMSCs and T lymphocytes in the presence of various stimuli. As shown in Figure1, there was a significant reduction in T-lymphocyte proliferation when mixed cultures of T lymphocytes stimulated by irradiated allogeneic PBLs (1:1 ratio) were performed in the presence of irradiated autologous BMSCs (90% ± 3%, as measured by means of 3HTdR incorporation; P = .0001). Similarly, when T-lymphocyte proliferation was elicited by means of aspecific polyclonal activators such as PHA (Figure 1) or IL-2 (data not shown), the addition of autologous BMSCs strongly inhibited T-cell proliferation. To assess further the inhibitory effect of BMSCs on T-lymphocyte proliferation, we used CD34+ cell-derived allogeneic DCs, which are considered to be the prototype of professional antigen-presenting cells. Addition of autologous BMSCs to the mixed T-lymphocyte and irradiated allogeneic DC cultures consistently reduced T-lymphocyte proliferation by more than 90% (P = .0001; Figure 1). The inhibition of T-cell proliferation was not observed when third-party BMSCs containing ≥5% of CD14+ cells were added to T cells stimulated by irradiated PBLs. Indeed, under these conditions, T-cell proliferation was increased over the values observed in standard MLRs of T cells plus PBLs, probably because of the antigen-presenting cell function exerted by CD14+ cells (Table 1).

Inhibitory effect of BMSCs on T-lymphocyte proliferation induced by allogeneic PBLs, DCs, or PHA.

Seven-day mixed cultures were performed with (black bars) or without (white bars) BMSCs. Data are expressed as mean ± SD of triplicates of 6 separate experiments. The stimulation index (SI) was calculated by using the following formula: proliferation of T lymphocytes incubated with cellular or humoral stimuli with or without BMSCs/proliferation of T lymphocytes alone. *Statistically significant (P = .004, at least) when compared with MLRs performed in the presence of BMSCs (Student t test for paired data).

Inhibitory effect of BMSCs on T-lymphocyte proliferation induced by allogeneic PBLs, DCs, or PHA.

Seven-day mixed cultures were performed with (black bars) or without (white bars) BMSCs. Data are expressed as mean ± SD of triplicates of 6 separate experiments. The stimulation index (SI) was calculated by using the following formula: proliferation of T lymphocytes incubated with cellular or humoral stimuli with or without BMSCs/proliferation of T lymphocytes alone. *Statistically significant (P = .004, at least) when compared with MLRs performed in the presence of BMSCs (Student t test for paired data).

Effect of third-party bone marrow stromal cells containing variable percentages of CD14+ cells on T-cell proliferation

| MLRs* . | Stimulation index (mean ± SD) . |

|---|---|

| T cells + PBLs | 36 ± 2 |

| T cells + PBLs + BMSCs containing 34% CD14+ cells | 51 ± 4† |

| T cells + PBLs + BMSCs containing 4% CD14+cells | 10 ± 1‡ |

| MLRs* . | Stimulation index (mean ± SD) . |

|---|---|

| T cells + PBLs | 36 ± 2 |

| T cells + PBLs + BMSCs containing 34% CD14+ cells | 51 ± 4† |

| T cells + PBLs + BMSCs containing 4% CD14+cells | 10 ± 1‡ |

MLR, mixed lymphocyte reaction; PBL, peripheral blood lymphocyte; BMSC, bone marrow stromal cell.

CD2+ (5 × 104) T cells were mixed at 1:1 ratio with allogeneic PBLs ± BMSCs.

Significantly increased as compared with MLRs without BMSCs (P = .001).

Significantly decreased as compared with MLRs without BMSCs (P = .001).

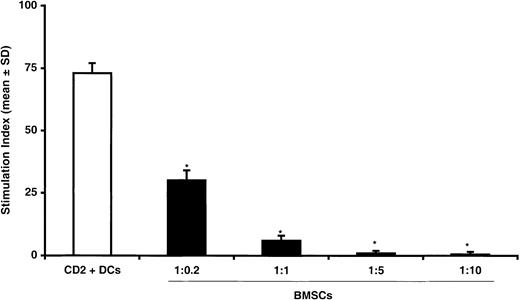

To investigate whether the inhibitory effect of BMSCs on T-lymphocyte proliferation was dose dependent, we cultured T lymphocytes and irradiated allogeneic DCs (1:1 ratio) with increasing amounts of irradiated BMSCs for 7 days. As shown in Figure2, addition of autologous BMSCs resulted in a dose-dependent inhibitory effect with a significant reduction of T-lymphocyte proliferation being observed at a 1:0.2 ratio, with a peak at a 1:5 ratio. Comparable inhibition was also observed when third-party BMSCs were used (data not shown). To demonstrate that the inhibition of DC-induced T-lymphocyte proliferation was caused by coculture with allogeneic or autologous BMSCs and was not due to a bulk effect, we cultured T lymphocytes with irradiated allogeneic DCs (1:1 ratio) in the presence of increasing amounts of irradiated autologous T lymphocytes for 7 days. Under these culture conditions, no suppression of T-lymphocyte proliferation was detected even when irradiated autologous T lymphocytes were added at a 1:10 ratio (data not shown), thus suggesting that the reduction of T-cell proliferation specifically required the presence of BMSCs.

Dose dependence of inhibitory effect of BMSCs on T-lymphocyte proliferation.

T lymphocytes were cultured with allogeneic CD34+cell–derived DCs at 1:1 ratio without (white bars) BMSCs or in the presence of increasing numbers of BMSCs (black bars) from 1:0.2 to 1:5 ratios. The data are expressed as mean ± SD of triplicates of 3 separate experiments. *Statistically significant when compared with MLRs performed in the presence of BMSCs (Student t test for paired data).

Dose dependence of inhibitory effect of BMSCs on T-lymphocyte proliferation.

T lymphocytes were cultured with allogeneic CD34+cell–derived DCs at 1:1 ratio without (white bars) BMSCs or in the presence of increasing numbers of BMSCs (black bars) from 1:0.2 to 1:5 ratios. The data are expressed as mean ± SD of triplicates of 3 separate experiments. *Statistically significant when compared with MLRs performed in the presence of BMSCs (Student t test for paired data).

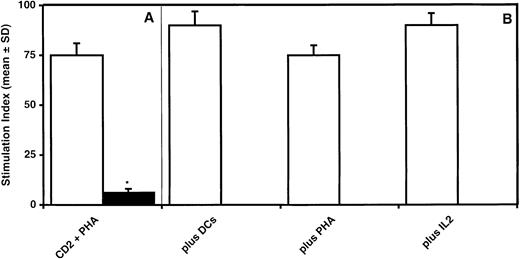

BMSC-inhibited T lymphocytes proliferate on restimulation

To evaluate whether or not the inhibition of T-lymphocyte proliferation induced by BMSCs was reversible, T cells stimulated by PHA and cultured for 7 days in the presence of irradiated BMSCs were recovered by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation and restimulated with either irradiated DCs, PHA, or IL-2. Following the initial 7-day culture of T cells with PHA in the presence of irradiated BMSCs (1:1 ratio), T-lymphocyte proliferation was reduced by 90% as compared with MLRs without BMSCs (P = .0001) (Figure3A). When T lymphocytes were harvested and restimulated for 2 days with allogeneic DCs, PHA, or IL-2, the restimulation led to a degree of proliferation that was comparable to that observed in control cultures without BMSCs, thus demonstrating that BMSC-induced inhibition of T-cell proliferation is a reversible phenomenon (Figure 3B).

BMSC-induced inhibition of T-lymphocyte proliferation is reversible.

Suppression of T-cell proliferation by BMSCs (A) is restored if T cells are recovered after a 7-day culture period and restimulated by DCs, PHA, or IL-2 in the absence of BMSCs (B). The data are expressed as mean ± SD of triplicates of 3 separate experiments. *Statistically significant when compared with MLRs performed in the presence of BMSCs (Student t test for paired data).

BMSC-induced inhibition of T-lymphocyte proliferation is reversible.

Suppression of T-cell proliferation by BMSCs (A) is restored if T cells are recovered after a 7-day culture period and restimulated by DCs, PHA, or IL-2 in the absence of BMSCs (B). The data are expressed as mean ± SD of triplicates of 3 separate experiments. *Statistically significant when compared with MLRs performed in the presence of BMSCs (Student t test for paired data).

T-lymphocyte proliferation is inhibited by the delayed addition of BMSCs

To investigate whether or not the delayed addition of BMSCs could suppress T-cell proliferation, BMSCs were added in a 1:1 ratio to 5-day-old cultures of T lymphocytes stimulated by either allogeneic DCs or PHA. As shown in Figure 4, T-lymphocyte proliferation induced by DCs or PHA was significantly inhibited by the delayed addition of BMSCs (75% ± 3% and 90% ± 2%, respectively).

Delayed addition of BMSCs inhibits T-lymphocyte proliferation induced by DCs or PHA.

T cells were cultured for 7 days before adding BMSCs (1:1 ratio). T cells proliferated without BMSCs (white bars) or were inhibited in the presence of BMSCs (black bars). The data are expressed as mean ± SD of triplicates of 6 separate experiments. *Statistically significant when compared with MLRs performed in the presence of BMSCs (Studentt test for paired data).

Delayed addition of BMSCs inhibits T-lymphocyte proliferation induced by DCs or PHA.

T cells were cultured for 7 days before adding BMSCs (1:1 ratio). T cells proliferated without BMSCs (white bars) or were inhibited in the presence of BMSCs (black bars). The data are expressed as mean ± SD of triplicates of 6 separate experiments. *Statistically significant when compared with MLRs performed in the presence of BMSCs (Studentt test for paired data).

CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes are equally inhibited by BMSCs

To investigate whether or not BMSCs could selectively inhibit the proliferation of T-lymphocyte subsets, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells stimulated by allogeneic PBLs, DCs, or PHA were cultured with or without BMSCs (1:1 ratio). As shown in Figure5, the addition of BMSCs equally suppressed the proliferation of both CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes induced by cellular or humoral stimuli.

CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell proliferation is equally inhibited by BMSCs.

Highly purified CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes were used as responders in cultures with allogeneic PBL, DCs, or PHA with (black bars) or without (white bars) BMSCs. Addition of BMSCs resulted in a significant inhibition of both CD4+ and CD8+ cells without statistical differences in all points evaluated (*P = .0005, Student t test for paired data). The percentage of inhibition obtained by using the whole CD2+ cell population was significantly higher (**P = .0001, Student t test for paired data). The data are expressed as mean ± SD of triplicates of 3 separate experiments.

CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell proliferation is equally inhibited by BMSCs.

Highly purified CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes were used as responders in cultures with allogeneic PBL, DCs, or PHA with (black bars) or without (white bars) BMSCs. Addition of BMSCs resulted in a significant inhibition of both CD4+ and CD8+ cells without statistical differences in all points evaluated (*P = .0005, Student t test for paired data). The percentage of inhibition obtained by using the whole CD2+ cell population was significantly higher (**P = .0001, Student t test for paired data). The data are expressed as mean ± SD of triplicates of 3 separate experiments.

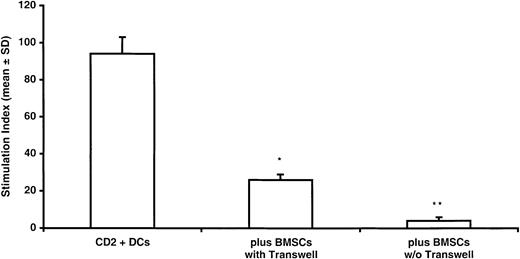

Mechanism(s) of BMSC-induced T-cell suppression

To investigate the mechanism(s) underlying BMSC-mediated T-cell suppression, we initially evaluated whether BMSC inhibition of T-cell proliferation was dependent on a cell-cell contact mechanism. To test this hypothesis, MLRs were performed by using transwell chambers to separate CD2+ cells and stimulators physically from the BMSCs. By using the transwell system, ie, when BMSCs were separated from effectors, T-lymphocyte proliferation was significantly inhibited (70% ± 13%; P = .0001; Figure6), thus suggesting that a soluble factor was involved in suppressing T-cell proliferation. However, the rate of T-lymphocyte inhibition was further increased when a cell-cell contact between BMSCs and effector cells was allowed (P = .004).

Cell-cell contact is not required to achieve inhibition of T-cell proliferation.

T lymphocytes and DCs were cultured in the transwell plates to avoid cell-cell contact with BMSCs. Under this culture condition, a significant inhibition (70% ± 5%) of T-cell proliferation was observed which suggested that a soluble factor(s) may be involved in BMSC-induced suppression of T-cell proliferation. In fact, inhibition of T-cell proliferation obtained in standard culture allowing cell-cell contact was significantly higher as compared with that observed in the transwell system. Data are expressed as mean ± SD of triplicates of 3 separate experiments. *Statistically significant when compared with MLRs performed in the transwell in the presence of BMSCs. **Statistically significant when compared with MLRs performed in the presence of BMSCs without transwell.

Cell-cell contact is not required to achieve inhibition of T-cell proliferation.

T lymphocytes and DCs were cultured in the transwell plates to avoid cell-cell contact with BMSCs. Under this culture condition, a significant inhibition (70% ± 5%) of T-cell proliferation was observed which suggested that a soluble factor(s) may be involved in BMSC-induced suppression of T-cell proliferation. In fact, inhibition of T-cell proliferation obtained in standard culture allowing cell-cell contact was significantly higher as compared with that observed in the transwell system. Data are expressed as mean ± SD of triplicates of 3 separate experiments. *Statistically significant when compared with MLRs performed in the transwell in the presence of BMSCs. **Statistically significant when compared with MLRs performed in the presence of BMSCs without transwell.

To identify inhibitory cytokines potentially suppressing T-cell proliferation, monoclonal antibodies neutralizing distinct cytokines that are known to be produced by BMSCs were evaluated for their capacity to restore T-cell proliferation.

Although addition of neutralizing monoclonal antibodies anti–rhIL-6 and anti–rhIL-11 failed to restore T-cell proliferation suppressed by BMSCs, addition of monoclonal antibodies neutralizing either rhTGF-β1 (1 μg/mL) or rhHGF (2.5 μg/mL) increased BMSC-suppressed T-lymphocyte proliferation by 1.8- and 1.6-fold, respectively. When anti–rhTGF-β1 (1 μg/mL) and anti-rhHGF (2.5 μg/mL) were simultaneously added to BMSC-containing MLRs, T-cell proliferation was restored at values that were comparable to those detected in MLRs without BMSCs.

As compared with control MLRs containing T cells plus irradiated PBLs but not BMSCs, addition of TGF-β1 (1 μg/mL) or rhHGF (2.5 μg/mL) reduced T-cell proliferation by 1.7- and 1.6-fold, respectively (Table 2). When rhTGF-β1 (1 μg/mL) and rhHGF (2.5 μg/mL) were simultaneously added to MLRs without BMSCs, T-cell proliferation was suppressed at values that were comparable to those detected in BMSC-containing MLRs (Table 2).

Modulation of T-cell proliferation by monoclonal antibodies neutralizing BMSC-derived cytokines

| MLRs* . | Stimulation index (mean ± SD) . |

|---|---|

| T cells + PBLs | 60 ± 5 |

| T cells + PBLs + BMSCs | 25 ± 3† |

| T cells + PBLs + BMSCs + anti-rhIL-6 (5 μg/mL) | 24 ± 4‡ |

| T cells + PBLs + rhIL-6 (5 μg/mL) | 55 ± 32-153 |

| T cells + PBLs + BMSCs + anti-rhIL-11 (50 μg/mL) | 20 ± 2‡ |

| T cells + PBLs + rhIL-11 (50 μg/mL) | 52 ± 22-153 |

| T cells + PBLs + BMSCs + anti-rhTGF-β (0.1 μg/mL) | 25 ± 2‡ |

| T cells + PBLs + BMSCs + anti-rhTGF-β (1 μg/mL) | 45 ± 12-153 |

| T cells + PBLs + rhTGF-β (1 μg/mL) | 35 ± 8† |

| T cells + PBLs + BMSCs + anti-rhHGF (0.25 μg/mL) | 24 ± 3‡ |

| T cells + PBLs + BMSCs + anti-rhHGF (2.5 μg/mL) | 39 ± 82-153 |

| T cells + PBLs + rhHGF (2.5 μg/mL) | 38 ± 5† |

| T cells + PBLs + BMSCs + anti-rhTGF-β (1 μg/mL) + anti-rhHGF (2.5 μg/mL) | 55 ± 22-153 |

| T cells + PBLs + rhTGF-β (1 μg/mL) + rhHGF (2.5 μg/mL) | 27 ± 3† |

| MLRs* . | Stimulation index (mean ± SD) . |

|---|---|

| T cells + PBLs | 60 ± 5 |

| T cells + PBLs + BMSCs | 25 ± 3† |

| T cells + PBLs + BMSCs + anti-rhIL-6 (5 μg/mL) | 24 ± 4‡ |

| T cells + PBLs + rhIL-6 (5 μg/mL) | 55 ± 32-153 |

| T cells + PBLs + BMSCs + anti-rhIL-11 (50 μg/mL) | 20 ± 2‡ |

| T cells + PBLs + rhIL-11 (50 μg/mL) | 52 ± 22-153 |

| T cells + PBLs + BMSCs + anti-rhTGF-β (0.1 μg/mL) | 25 ± 2‡ |

| T cells + PBLs + BMSCs + anti-rhTGF-β (1 μg/mL) | 45 ± 12-153 |

| T cells + PBLs + rhTGF-β (1 μg/mL) | 35 ± 8† |

| T cells + PBLs + BMSCs + anti-rhHGF (0.25 μg/mL) | 24 ± 3‡ |

| T cells + PBLs + BMSCs + anti-rhHGF (2.5 μg/mL) | 39 ± 82-153 |

| T cells + PBLs + rhHGF (2.5 μg/mL) | 38 ± 5† |

| T cells + PBLs + BMSCs + anti-rhTGF-β (1 μg/mL) + anti-rhHGF (2.5 μg/mL) | 55 ± 22-153 |

| T cells + PBLs + rhTGF-β (1 μg/mL) + rhHGF (2.5 μg/mL) | 27 ± 3† |

BMSC, bone marrow stromal cell; MLR, mixed lymphocyte reaction; PBL, peripheral blood lymphocyte; rhIL-6, recombinant human interleukin 6; TGF, transforming growth factor; hepatocyte growth factor.

CD2+ (5 × 104) T cells were mixed at 1:1 ratio with allogeneic PBLs ± BMSCs.

Statistically different as compared with MLRs without BMSCs (P = .0001).

Not statistically different as compared with MLRs with BMSCs (P = .05).

Not statistically different as compared with MLRs without BMSCs (P = .05).

To test whether or not the inhibitory effect of BMSCs was associated with T-lymphocyte apoptosis, the percentage of CD2+/PI+ cells and the expression of CD10 antigen, which may represent a reliable marker for identifying and isolating apoptotic T-lymphocytes,27 were evaluated after 7-day culture of T lymphocytes with DCs (or PHA) and BMSCs. The percentage of CD2+ cells that were also PI+ was less than 2% ± 1%; furthermore, the harvested CD2+cells did not express CD10 antigen on their cell surface (data not shown).

Discussion

In the present paper, we demonstrate that (1) ex vivo-expanded BMSCs have an inhibitory effect on T-cell proliferation triggered by allogeneic PBLs and DCs, or mitogens such as PHA or IL-2; (2) this effect is dose dependent and is still evident when BMSCs come from a third party; (3) BMSC-inhibited T lymphocytes are not apoptotic and efficiently proliferate when restimulated with cellular or humoral activators in the absence of BMSCs; (4) the delayed addition of BMSCs to MLRs leads to the inhibition of T-cell proliferation; (5) CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are equally inhibited by BMSCs; and (6) BMSC-released cytokines, such as rhHGF and/or rhTGF-β1, mediate the inhibitory effects of BMSCs.

Bone marrow is the major source of the adult hemopoietic stem cells that renew circulating blood elements. Adult bone marrow also contains stromal stem cells, which contribute to the regeneration of several tissues such as bone, cartilage, muscle, ligament, tendon, adipose tissue, and marrow stroma.9 Human BMSCs have been identified and characterized, and it has been shown that they support hematopoietic progenitors and secrete a number of hematopoietic cytokines both constitutively and in response to IL-1.27,28 Genetically modified BMSCs are not rejected when transplanted in baboons, thus suggesting that they are not significantly immunogenic.24 This finding may be due to the peculiar immunophenotypic features of BMSCs, such as the lack of HLA class II as well as the T-cell costimulatory molecule B7.25,29 Current technology allowing the ex vivo expansion of BMSCs without any apparent loss of phenotype and function25,29 opens the way to the clinical application of BMSCs in allogeneic BMT. Recently, Lazarus et al30 reported a phase I BMSC dose-escalation study evaluating the cotransplantation of HLA-identical BMSCs together with either peripheral blood or bone marrow–derived hematopoietic stem cells from the same donor in patients with advanced hematologic malignancies. To date, no significant toxicities have been observed, and the 15 evaluable patients experienced a reduction of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).30

Data reported in our paper confirm the inhibitory effect of BMSCs on T-cell proliferation triggered by cellular or humoral stimuli. To further evaluate the inhibitory effect of BMSCs, we also used as MLR stimulators allogeneic professional antigen-presenting cells (ie, CD34+ cell–derived DCs) known to be the best stimulators of T-cell proliferation. Even under these experimental conditions, there was a dramatic and dose-dependent reduction of T-cell proliferation. Indeed, when the amount of CD14+ macrophages contaminating stromal cell layers of a third party was 5%, no evidence of suppression of T-cell proliferation could be detected. This finding is likely to be due to the peculiar antigen expression profile of CD14+ cells, including the high expression of MHC class I and II antigens as well as expression of costimulatory molecules, which results in a strong stimulation of T-cell proliferation.

As far as the mechanism(s) underlying the inhibitory effect of BMSCs is concerned, data reported herein rule out the possibility that BMSCs induce T-cell apoptosis, whereas they strongly suggest that cell-cell contact is not a mandatory requirement for suppressing T-cell proliferation, whereas BMSCs produce soluble factors, including rhTGF-β1 and rhHGF, which mediate suppression of T-cell proliferation. Blocking studies with anti–rhTGF-β1 and anti-rhHGF monoclonal antibodies suggest that these 2 BMSC-produced cytokines work in a synergistic manner because T-cell proliferation is fully restored when both antibodies are used. Recent data in a murine model of allogeneic BMT demonstrating that the treatment with rhHGF ameliorates acute GVHD strongly corroborate our findings.31

Several cell types, including graft-facilitating cells,32 veto cells,33 and even CD34+ cells,34 have been demonstrated in in vitro and in vivo models to be able to exert immunoregulatory effects resulting in prevention of GVHD or tolerogenic activities. Ex vivo–generated BMSCs might be useful in clinical situations in which engraftment failure is high, such as HLA-mismatched sibling, matched unrelated donor marrow, or umbilical cord blood transplantation, and may decrease GVHD and facilitate the engraftment and proliferation of hemopoietic progenitors. Reinfusion of BMSCs aimed at exploiting an immunoregulatory role might eventually be of relevance also in the setting of allografting with reduced conditioning regimens.

The obvious prerequisite for stromal cell–based therapy is that stromal cells must be capable of efficient engraftment. Although it has been demonstrated in various animal models, the engraftment of BMSCs in patients undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplantation appears to be absent35 or limited, as recently shown by us in recipients of allogeneic T-cell–depleted stem cell allografts.36Recent studies using ex vivo–generated stromal cells have clearly shown that, when stromal cells are transplanted in the human-sheep xenograft model of in utero transplantation, they seed the bone marrow, enhance hematopoietic recovery, and are capable of eliciting tissue-specific differentiation programs.37 38 However, the question is still open for humans, and no conclusive evidence has yet been provided concerning the homing properties and in vivo persistence of ex vivo–generated stromal cells.

In conclusion, the data presented in this paper clearly demonstrate that BMSCs suppress T-cell proliferation induced by cellular or humoral stimuli. This finding implies that the in vitro phenomenon we report herein is likely to be an antigen-independent immunologic effect. In addition, BMSC-induced T-cell suppression has no immunologic restriction because both autologous and third-party BMSCs can suppress T-cell proliferation. The mechanism underlying BMSC-mediated suppression of T-cell proliferation—which seems to be due to a production of cytokines by stromal cells—indeed requires further investigation in appropriate in vivo models analyzing both homing and functional properties of reinfused BMSCs. Such in vivo models should also address the question of the clinical relevance of BMSC-mediated T-cell suppression.

We thank Drs. F. Locatelli and R. Maccario (Department of Pediatrics, Università di Pavia, Pavia, Italy) for providing a critical review of the manuscript and Dr A. Anichini (Department of Experimental Oncology, Istituto Nazionale Tumori, Milan, Italy) for helpful discussion.

Supported in part by grants from “Ministero dell'Istruzione, Università e Ricerca,” and “Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro” (A.I.R.C.).

M.D.N. and C.C.-S. contributed equally to this work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Massimo Di Nicola, “C Gandini” Bone Marrow Transplantation Unit, Istituto Nazionale Tumori, Via Venezian, 1 Milan, Italy; e-mail: dinicola@istitutotumori.mi.it.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal