Neutrophils (polymorphonuclear leukocytes [PMNs]) carry potent destructive enzymes that can destroy invasive bacteria or damage normal tissue. PMNs have a half-life of only 6 hours in the blood, but the details of this homeostasis are unknown. In a rat model of endotoxemia, P-selectin was selectively up-regulated in hepatic sinusoids and veins where it was necessary for phagocytosis of PMNs by Kupffer cells in the liver, as opposed to the spleen or the lungs. Apoptotic PMNs appeared in the lungs and spleen only after inactivation of Kupffer cells by gadolinium chloride (GdCl3). Blocking of Fas protein reduced the number of apoptotic cells in the liver; binding of annexin V to phosphatidylserine (PS) reduced the number of PMNs phagocytosed by Kupffer cells. The results support a clearance pathway in which apoptosis and phagocytosis are effected by Kupffer cells after P-selectin–mediated sequestration.

Introduction

Circulating polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs), the first line of defense against invasion by pathogenic bacteria, influence the balance between humoral and cell-mediated immunity in the early stages of the immune response by synthesizing and releasing immunoregulatory cytokines.1 Under pathologic conditions PMNs may injure normal tissue by releasing reactive oxygen intermediates, toxic cationic proteins, and degradative enzymes.2 Because 10 million new granulocytes are released into the bloodstream from the bone marrow every minute, an equal number must be removed within a relatively short period to maintain a proper balance in cell numbers.3 Therefore, regulating the number of PMNs in the circulation and prompt removal of senescent PMNs may be important for maintaining normal immune function and preventing tissue injury.

Complete absence of endothelial P-selectin results in neutrophilia, indicating that P-selectin is involved in removal of PMNs4-6 from the circulation. Furthermore, expression of P-selectin on hepatic endothelia promotes phagocytosis of PMNs by Kupffer cells.7 Circulating Fas ligand is involved in mediating neutropenia,8 suggesting a pathway for PMN senescence. However, questions remain concerning the sites of P-selectin expression and of PMN sequestration by macrophages and the timing and location of the Fas/Fas ligand (FasL) stimulation toward apoptosis, although interactions between leukocytes and endothelia have been reviewed.9 10

Material and methods

Antibodies and drugs

Antibody (Ab) HIS48 to granulocytes, polyclonal Ab to P-selectin, CD61 monoclonal Ab (MoAb) to platelet, and annexin V-biotin to phosphatidylserine (PS) were from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). Abs to Fas and FasL were from Wako (Osaka, Japan) and Pharmingen. ED1 and ED2 Abs to the macrophage-related antigens were from Serotec (Kidlington, Oxford, United Kingdom). A control Ab to rat IgG, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), and fucoidin, antagonists to P-selectin, and gadolinium chloride (GdCl3), an agent used to block the function of Kupffer cells, were from Sigma (St Louis, MO). Proteinase K and biotin-16-2′-deoxyuridine-5′-triphosphate (biotin-16-dUTP) were from Boehringer (Mannheim, Germany). Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) was from Gibco BRL (Gaithersburg, MD). Other Abs, including biotinylated goat anti–mouse Ig, biotinylated goat anti–rabbit Ig, goat Ig to mouse IgG, goat Ig to rabbit IgG, mouse peroxidase–antiperoxidase (PAP) Ab complex, rabbit PAP Ab complex, and peroxidase–conjugated streptavidin, were from Dako (Carpinteria, CA).

Experimental design

In the first experiment, 7- to 9-week-old male Wistar rats (Nippon Biological Supply, Tokyo, Japan) were injected with LPS (0.1 mg/kg intravenously [IV]) or sterile saline, and perfusion fixed at 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 hours after injection. In the second experiment, animals were treated with anti–P-selectin Ab (2.0 mg/kg, IV) or LMWH (70-125 IU/mg, 30 mg/kg, IV), or fucoidin (10 mg/kg) 10 minutes after the injection of LPS. In some animals, GdCl3 (10 mg/kg, IV) was administered 6 hours before the LPS injection. Blocking of PS by annexin V-biotin (500 μg/kg) binding was performed. Animals were killed 30 minutes after injection of annexin V. In vivo injections of anti-Fas/FasL Abs (2.5 mg/kg) and a control Ab to IgG were also performed. The liver of each animal was perfusion fixed at 1, 3, 6, and 12 hours after the LPS or saline injection. The paraffin sections (4 μm), stained with the immunohistochemistry and TUNEL methods, as well as the semithin sections (0.2 μm) stained with toluidine blue, were analyzed by light microscopy at × 250. Cell number/mm2was counted. Each value is expressed as a mean ± SD of 3 to 5 rats, and some statistical analyses were performed using the Student t test. A level of P < .05 was considered significant. This study conformed to the guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals established by the Animal Care Committee of Tokyo Medical and Dental University.

Quantitation of circulating PMNs

The number of PMNs was counted by a method described by Bouwens and coworkers.11 For each animal, a total tissue area of approximately 8 mm2 (130 fields, 0.0625 mm2/field) was counted from a random sample of 5 sections. The paraffin sections (4 μm) stained with Ab HIS48 were analyzed by light microscopy at × 250. The number of PMNs/mm2 was counted. Blood samples were taken aseptically from the tail vein at 0, 1, 3, 6, and 12 hours after LPS or saline treatment, and smears were prepared immediately. Circulating total leukocyte numbers were determined by light microscopic counting. Giemsa- and TUNEL-stained smear samples of both control (treated with saline only) and treated animals were examined by light microscopy and 500 leukocytes were counted, and total PMN numbers were determined by reference to total leukocyte counts. Given variable PMN counts, results were expressed as a percentage of the PMN- or TUNEL-positive cell count. The statistical significance of data was assessed; P < .05 was considered significant.

DNA nick end-labeling and immunohistochemistry

Paraffin sections on glass slides coated with poly-L-lysine were stained by the TUNEL (a method that is often used to detect fragmented DNA; it uses a reaction catalyzed by exogenous TdT, often referred to as end-labeling) and immunohistochemistry method.7 In situ detection of apoptotic cells has been performed by the IV injection of annexin V-biotin.12 13 In brief, animals were killed 30 minutes after injection of annexin V-biotin, sections were stained using peroxidase–conjugated strepatavidin, and colored blue by 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine solution.

Results

Expression of P-selectin and accumulation of PMNs in situ

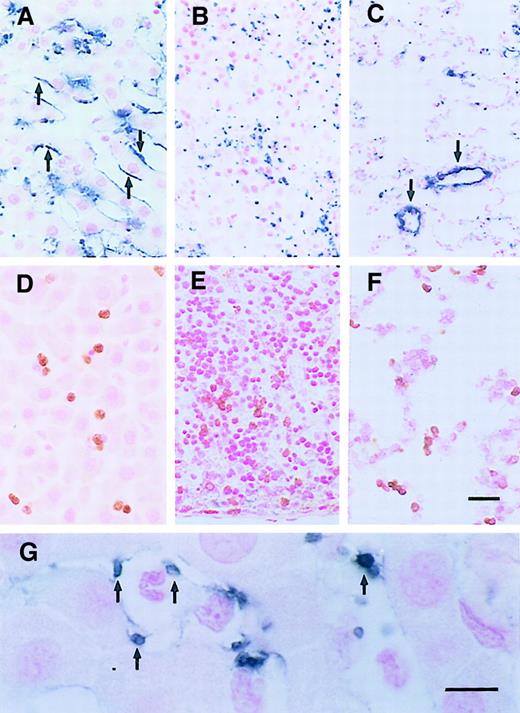

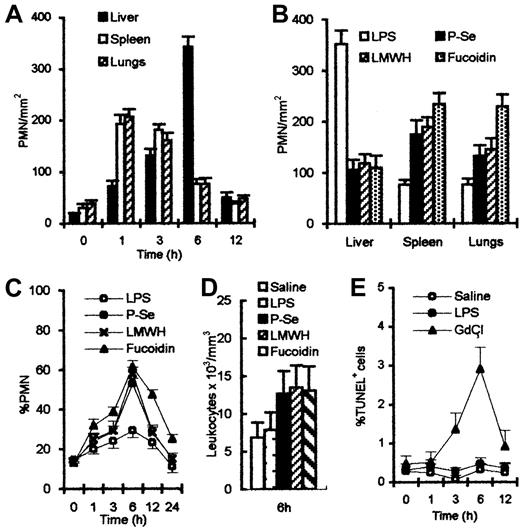

After LPS treatment, the rat liver expressed P-selectin on endothelial cells in portal veins, sublobular veins, and sinusoids. Expression peaked at 6 hours (Figure 1A). No expression of P-selectin was seen on endothelial cells of splenic sinusoids or pulmonary capillaries, although some expression could be found on platelets and large vessels in the spleen and lungs (Figure1B,C). This difference in expression of P-selectin among the liver, spleen, and lungs reflects functional heterogeneity of the vasculature in the respective organs. PMNs were identified in liver (Figure 1D), spleen (Figure 1E), and lungs (Figure 1F) by a specific Ab to PMN (HIS48). Many platelets in the sinusoids of the liver were labeled by platelet marker, an MoAb to CD61 (F11) (Figure 1G). F11 MoAbs react with β3-integrin chain (CD61), which associates with αIIb-integrin chain to form the glycoprotein (gp)IIb/IIIa (CD41/CD61) complex. Platelets were closely associated with the trapped PMNs. The kinetics of PMN appearance in the liver, spleen, and lungs were evaluated by counting PMNs in 130 fields, each 0.0625 mm2 in area. After the injection of LPS, the number of PMNs increased rapidly and peaked at 1 hour in the spleen and lungs, and thereafter was reduced. In contrast, the number of PMNs in the liver increased to a peak at 6 hours (Figure2A). Serial sections showed that the areas of P-selectin expression correlated with the presence of PMNs in the liver. Pretreatment with Ab to P-selectin, or antagonists to P-selectin, LMWH and fucoidin, blocked P-selectin and decreased the arrest of PMNs in the liver, but led to increased accumulation in the spleen or lungs (Figure 2B). Blocking P-selectin also increased the number of PMNs (Figure 2C) and total leukocytes (Figure 2D) in peripheral blood. To confirm that the hepatic sequestration pathway requires an intact phagocytic mechanism of Kupffer cells, rats were pretreated with GdCl3. This led to the appearance of TUNEL-positive PMNs in peripheral blood (Figure 2E). These results indicate that systemic LPS stimulates focal P-selectin expression in the liver where senescent PMNs are sequestered and phagocytosed.

Localization of P-selectin, PMNs, and platelets 6 hours after LPS injection.

(A) P-selectin was expressed on sinusoidal endothelia of the liver (arrows), not the splenic sinusoids (B), nor the pulmonary capillaries (C), although some trapped platelets (B, blue spots) and large vessels (C, arrows) were labeled. (D) PMNs were labeled with Ab HIS48 (brown) in the hepatic sinusoids, splenic sinusoids (E), and pulmonary capillaries (F). (G) Platelets in hepatic sinusoids were labeled by MoAb CD61 (arrows). Scale bars, panels A-F, 20 μm; panel G, 10 μm.

Localization of P-selectin, PMNs, and platelets 6 hours after LPS injection.

(A) P-selectin was expressed on sinusoidal endothelia of the liver (arrows), not the splenic sinusoids (B), nor the pulmonary capillaries (C), although some trapped platelets (B, blue spots) and large vessels (C, arrows) were labeled. (D) PMNs were labeled with Ab HIS48 (brown) in the hepatic sinusoids, splenic sinusoids (E), and pulmonary capillaries (F). (G) Platelets in hepatic sinusoids were labeled by MoAb CD61 (arrows). Scale bars, panels A-F, 20 μm; panel G, 10 μm.

Number of PMNs after various treatments.

(A) Number of PMNs reached maximal levels at 1 hour in spleen and lungs, 6 hours in the liver after LPS injection. (B) Number of PMNs was reduced in the liver after treatment with anti–P-selectin Ab or LMWH or fucoidin; significant increases were observed in spleen and lungs, compared with LPS treatment alone. (C) Percent of PMNs in peripheral blood increased and combined treatment increased more and peaked 6 hours after LPS injection. (D) About 2-fold higher total leukocyte count with anti–P-selectin Ab or LMWH or fucoidin than control was observed in peripheral blood. (E) Percent of circulating TUNEL-positive cells showed no significance between saline and LPS treatment; however, a significant increase was observed 6 hours after GdCl3injection.

Number of PMNs after various treatments.

(A) Number of PMNs reached maximal levels at 1 hour in spleen and lungs, 6 hours in the liver after LPS injection. (B) Number of PMNs was reduced in the liver after treatment with anti–P-selectin Ab or LMWH or fucoidin; significant increases were observed in spleen and lungs, compared with LPS treatment alone. (C) Percent of PMNs in peripheral blood increased and combined treatment increased more and peaked 6 hours after LPS injection. (D) About 2-fold higher total leukocyte count with anti–P-selectin Ab or LMWH or fucoidin than control was observed in peripheral blood. (E) Percent of circulating TUNEL-positive cells showed no significance between saline and LPS treatment; however, a significant increase was observed 6 hours after GdCl3injection.

Control animals, injected with saline, showed no increased accumulation of PMNs. These cells were rare in hepatic sinusoids, splenic sinusoids, and pulmonary capillaries. No staining by anti–P-selectin Abs was observed on endothelial cells in the spleen or lungs, nor on endothelial cells in hepatic sinusoids in control animals. Weak staining of portal vein endothelia was seen.

Apoptosis and elimination of PMNs in the liver

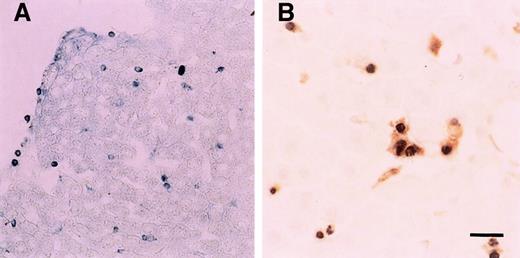

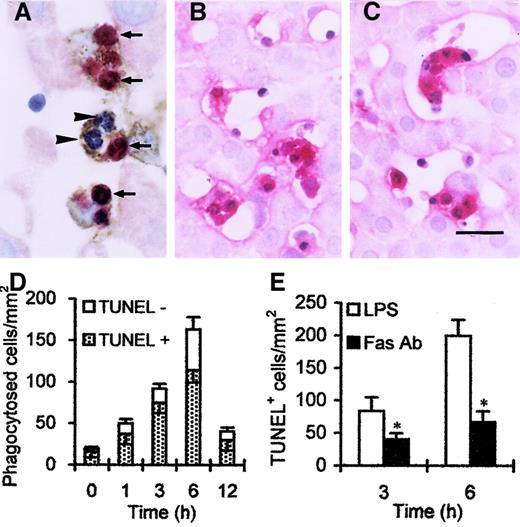

In situ annexin V binding showed apoptotic PMNs in the liver (Figure 3A). Double staining for cells with DNA fragmentation (black) and macrophages (brown) showed that PMN apoptosis occurred in the liver, with most apoptotic cells localized in hepatic sinusoids or within ED1+/ED2+macrophages (Figure 3B). Surprisingly, very few apoptotic PMNs were found in the spleen and lungs though many PMNs were present in these tissues in the first hours after LPS injection (Figure 1E,F). In addition, blood smear preparations also showed few circulating TUNEL-positive cells (data not shown). It is interesting to note that both PMNs with DNA fragmentation (red by TUNEL) and those without DNA fragmentation (blue by hematoxylin) were frequently found in Kupffer cells (Figure 4A, brown). In fact, more than 30% of phagocytosed PMNs showed no DNA fragmentation at 6 hours (Figure 4D). This indicates that Kupffer cells phagocytose PMNs, which are not frankly apoptotic.

In situ annexin V binding and DNA nick end-labeling assay 6 hours after LPS injection.

(A) A number of annexin V binding-positive cells (blue spots) were in the liver. (B) Double staining showed apoptotic PMNs (black) were phagocytosed by Kupffer cells (brown). Scale bar, 20 μm.

In situ annexin V binding and DNA nick end-labeling assay 6 hours after LPS injection.

(A) A number of annexin V binding-positive cells (blue spots) were in the liver. (B) Double staining showed apoptotic PMNs (black) were phagocytosed by Kupffer cells (brown). Scale bar, 20 μm.

PMNs and Kupffer cells in the liver.

(A) Double staining showed that TUNEL-positive (red, arrows) and TUNEL-negative (blue, arrowheads) PMNs were trapped by ED2+Kupffer cells (brown). Both PMNs and Kupffer cells were labeled by Fas (B) and FasL (C) after LPS injection. (D) Number of phagocytosed cells peaked 6 hours after LPS injection; moreover, TUNEL-negative cells occupied more than 30% in phagocytosed cells. (E) Number of TUNEL-positive cells was reduced at 3 hours, and significant reduction was observed 6 hours after combined treatment with anti-Fas Ab, compared with LPS treatment alone. *P < .05 versus LPS treatment only. Scale bar, 20 μm.

PMNs and Kupffer cells in the liver.

(A) Double staining showed that TUNEL-positive (red, arrows) and TUNEL-negative (blue, arrowheads) PMNs were trapped by ED2+Kupffer cells (brown). Both PMNs and Kupffer cells were labeled by Fas (B) and FasL (C) after LPS injection. (D) Number of phagocytosed cells peaked 6 hours after LPS injection; moreover, TUNEL-negative cells occupied more than 30% in phagocytosed cells. (E) Number of TUNEL-positive cells was reduced at 3 hours, and significant reduction was observed 6 hours after combined treatment with anti-Fas Ab, compared with LPS treatment alone. *P < .05 versus LPS treatment only. Scale bar, 20 μm.

To evaluate the pathway through which apoptosis is initiated in sequestered cells, expression of Fas and FasL in situ was evaluated; as shown in Figure 4, panels B and C. Both Fas and FasL were expressed on PMNs and Kupffer cells. Injection of anti–Fas IgG Ab partly blocked apoptosis (Figure 4E). These results indicate that apoptosis is initiated or accelerated by the Fas/FaL pathway.

Phagocytic blockade with GdCl3 resulted in neutrophilia. Under these conditions apoptotic PMNs were found in the spleen (Figure5A,B) and lungs (Figure 5C,D) and decreased in the liver (Figure 5E,F). Partial phagocytic blockade of macrophages was also effected by injection of annexin V. This treatment also resulted in inhibition of phagocytosis by Kupffer cells (Figure5G).

Apoptotic cells after various treatments.

A number of TUNEL-positive cells (blue spots: spleen [A], lungs [C]) and annexin V-positive cells (spleen [B], lungs [D]) were labeled. (E) The number of TUNEL-positive cells in the liver peaked 6 hours after LPS; however, a significant increase was observed in spleen and lungs only after combined treatment with LPS and GdCl3. (F) A number of annexin V-positive cells were observed in the liver 6 hours after LPS. But significant increases were found in spleen and lungs after GdCl3 treatment. (G) The number of phagocytosed cells was reduced, and significant reduction was observed in the liver 6 hours after combined treatment with annexin V, compared with LPS treatment alone. *P < .05 versus LPS treatment only. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Apoptotic cells after various treatments.

A number of TUNEL-positive cells (blue spots: spleen [A], lungs [C]) and annexin V-positive cells (spleen [B], lungs [D]) were labeled. (E) The number of TUNEL-positive cells in the liver peaked 6 hours after LPS; however, a significant increase was observed in spleen and lungs only after combined treatment with LPS and GdCl3. (F) A number of annexin V-positive cells were observed in the liver 6 hours after LPS. But significant increases were found in spleen and lungs after GdCl3 treatment. (G) The number of phagocytosed cells was reduced, and significant reduction was observed in the liver 6 hours after combined treatment with annexin V, compared with LPS treatment alone. *P < .05 versus LPS treatment only. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Discussion

The PMNs enter the bloodstream as postmitotic, terminally differentiated cells that ordinarily undergo apoptosis within 8 to 12 hours. Remarkably little has been understood about their fate, largely because of rapid elimination and cell dynamics. We present evidence that (1) endotoxemia selectively up-regulated hepatic P-selectin exposure, (2) active phagocytosis of apoptotic circulating PMNs was essentially limited to the liver, (3) viable PMNs were sequestered and the Fas/FasL system produced PMN apoptosis, and (4) PMNs were phagocytosed by Kupffer cells through surface PS.

Some reports showed a decrease in PMN apoptosis by inflammatory agents such as LPS, but most of these studies were performed in vitro.14-18 These studies were performed with prolonged exposure of cells to high concentrations of LPS, conditions that differ dramatically from our in vivo studies. LPS is cleared from the blood and detoxified and degraded in Kupffer cells and hepatocytes within 30 minutes of injections.19-22 The small dose of LPS used for these studies (0.1 mg/kg body weight) was chosen to induce expression of P-selectin and increase the number of PMNs in the circulation without causing disseminated intravascular coagulation or shock. We assumed that the resulting expression of P-selectin and excess of the PMNs occurred with little effect on PMN longevity. This approach enabled us to characterize the time course and magnitude of P-selectin expression, define the heterogeneous expression of P-selectin, and quantify and examine the localization and elimination of PMNs in the liver.

Almost no tissue injury was observed in our model of endotoxemia, despite accumulation of large numbers of PMNs in the liver, spleen, and lungs. Accumulation of PMNs was transient, which indicates that mechanisms must exist to remove PMNs from capillaries without tissue injury.

Our data indicate that selective P-selectin expression on hepatic endothelia but not splenic or pulmonary endothelia is functionally related to selective clearance of PMNs by Kupffer cells. These results indicate first, that P-selectin and Kupffer cells are involved in PMN accumulation in the liver, and second, that PMNs released from the spleen and lungs subsequently are arrested in the liver. This release of PMNs from spleen and lungs is consistent with previous demonstration of shedding of L-selectin by PMNs sequestered in the lungs,23 as well as our own results showing few L-selectin–positive PMNs in the liver (data not shown). A recent study has reported that PMN margination in pulmonary capillaries does not require E- and P-selectins,24 and we found no expression of P-selectin on pulmonary capillaries.

Exposure of PS on the outer surface of the plasma membrane is an early indicator of apoptosis in mammalian cells25 and can be detected in situ by IV injection of biotin-conjugated annexin V in animals.26 The normal extent of detection for apoptotic PMNs is a few in the liver, and none in spleen or lungs. Chromatin condensation and DNA fragmentation appear to occur within a few minutes, and rapid phagocytosis of apoptotic cells probably interrupts full completion of the apoptotic process. This may explain why these processes are rarely observed in static histologic observations. However, injection with a small amount of LPS increased numbers of annexin V-binding cells and TUNEL-positive cells in the liver. Few positive cells could be found in the spleen or lungs. The results indicated that PMN apoptosis occurred in the liver, with most apoptotic cells localized in hepatic sinusoids or within Kupffer cells. Paucity of apoptosis and phagocytosis of PMNs in the spleen and lungs was an unexpected finding in our study, because PMNs were also found in the spleen and lungs. In addition, peripheral blood smear preparations showed few TUNEL-positive cells (data not shown). These results indicate that both apoptosis and phagocytosis of PMNs occur in the liver, but not the spleen or lungs, and must depend on mechanisms in the hepatic microenvironment. Surprisingly, some phagocytosed PMNs were negative on TUNEL staining (Figure 4A, arrowheads) and more than 30% of phagocytosed PMNs showed no DNA fragmentation at 6 hours (Figure4D); this indicates that some viable PMNs were phagocytosed and killed within Kupffer cells.

Differentiated macrophages, a constitutive source of FasL in the immune system, play a key role in regulating numbers of peripheral T lymphocytes.27,28 Liver macrophages (Kupffer cells) apparently have an analogous function in the homeostasis of peripheral T lymphocytes29 and circulating PMNs in this study. Recent studies have demonstrated that membrane-bound, as opposed to soluble FasL, or tumor necrosis factor-α30 is highly effective in inducing apoptosis in T cells. This finding is consistent with our observation that cell-to-cell contact appears essential in Kupffer cell-mediated apoptosis.7 We have found the concentration of apoptotic cells to be highest in regions enriched in Kupffer cells, and within these regions Kupffer cells may initiate or propagate apoptotic events. Cultured and isolated PMNs constitutively express Fas/FasL and are highly sensitive to Fas/FasL interactions.31 We tested whether expression of Fas and FasL in situ agreed with our quantitative data; as shown in the results, both Fas and FasL were expressed on PMNs and Kupffer cells. Injection of anti–Fas IgG Ab partly blocked apoptosis. These results suggest that PMNs may be committed to autocrine death by virtue of their constitutive coexpression of cell surface Fas and FasL. Furthermore, Kupffer cells can serve as a source of FasL, which may function in juxtacrine and paracrine pathways mediating apoptosis of circulating PMNs in the course of maintaining PMN homeostasis. Induction of apoptosis by macrophages is of interest, particularly considering recent reports that occurrence of apoptosis is consistent with macrophage cytocidal activity30,32 33 where cells are engulfed before overall death of the tissue, and subsequently acquire a morphology typical of apoptosis. Injection of anti-FasL and control IgG Abs did not measurably inhibit apoptosis. It is possible that the anti-FasL Ab was cleared by the rat phagocytic system too rapidly to inhibit apoptosis.

Studies on the mechanism of selective phagocytosis of apoptotic PMNs by macrophages in vitro show that macrophage surface molecules including CD36 and αvβ3-vitronectin receptors appear to bind apoptotic PMNs via a molecular bridge with thrombospondin.34 Apoptotic cells have been shown to expose PS on the external leaflet of their plasma membrane.35 This PS, normally sequestered in the internal leaflet of the plasma membrane, may be recognized by receptors on macrophages.36,37 In our study, blocking the activity of Kupffer cells with GdCl3 severely affected homeostasis of PMN numbers, resulting in an apoptotic neutrophilia caused at least in part by a delayed removal of PMNs. In the course of this neutrophilia, a number of apoptotic PMNs were found in the spleen and lungs and decreased in the liver 6 hours after GdCl3 injection. In vivo binding of PS by injected annexin V resulted in inhibition of phagocytosis by Kupffer cells. The findings suggest that recognition of apoptotic PMNs by Kupffer cells is mediated partly through external translocation of PS. These fundamental membrane structure-function relationships established in the erythrocyte paradigm are being applied increasingly to lymphocytes,38 platelets, and PMNs, suggesting that elimination of blood cells occurs through PS recognition by Kupffer cells.

The results suggest that up-regulation of the P-selectin–mediated, hepatic clearance pathway may be a common mechanism for the neutropenia that occurs in many bacterial infections such as brucellosis, tuberculosis, and acute, early endotoxemia. We speculate that malfunction of this clearance pathway may be relevant in some diseases characterized by neutrophil-induced tissue injury.39

We thank Akira Masuda for his technical assistance.

Supported, in part, by grant R01 HL57867 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Jialan Shi, VA Boston Healthcare Center, 1400 VFW Pkwy, West Roxbury, MA 02132; e-mail: jialan_shi@hms.harvard.edu.

![Fig. 5. Apoptotic cells after various treatments. / A number of TUNEL-positive cells (blue spots: spleen [A], lungs [C]) and annexin V-positive cells (spleen [B], lungs [D]) were labeled. (E) The number of TUNEL-positive cells in the liver peaked 6 hours after LPS; however, a significant increase was observed in spleen and lungs only after combined treatment with LPS and GdCl3. (F) A number of annexin V-positive cells were observed in the liver 6 hours after LPS. But significant increases were found in spleen and lungs after GdCl3 treatment. (G) The number of phagocytosed cells was reduced, and significant reduction was observed in the liver 6 hours after combined treatment with annexin V, compared with LPS treatment alone. *P < .05 versus LPS treatment only. Scale bar, 20 μm.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/98/4/10.1182_blood.v98.4.1226/6/m_h81611407005.jpeg?Expires=1769091907&Signature=jw~5~gZlFYQmGlWA7WPZ0TWbl~bz07Jk-lrVpzCsximfsOF1Xs8fv-CcQAHoaiaDRUN2xF-iNM5Kph22phGfF~euFrZqiF~UXxFWux93VBGrV6EMpKhxObq-iBrH1I45O5ND~2oHzmwMl-v1UnXke7ZoITXkUih~QCnJh9B6IjMlYmezcV1rq9aOzd~LflT6QVY-~eY1b~35jbm2YBvI9ElxhP3eh5ngB9CZuJKWBYp~IxiuFyDTY53gVXN8HufRkVFwCyhzSHd~5xAbzji10IJCCGUmjLzUbpbLtp-yjtLYVy5WE9prsTLr2mAmLY9jOz~C6wnRwwrTXlJmLgdgKg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal