Abstract

Desferrioxamine (DFO) and the hydroxypiridinone (HPO) deferiprone (CP20) chelate iron as well as other metals. These chelators are used clinically to treat iron overload, but they induce apoptosis in thymocytes. Thymocyte apoptosis is potentiated by zinc deficiency, suggesting that these iron chelators may induce apoptosis by depleting stores of zinc. Exposure of murine thymocytes to either DFO or deferiprone resulted in significant reductions in the labile intracellular zinc pool. Moreover, increasing intracellular zinc levels, by chronic zinc dietary supplementation to mice or in vitro loading with zinc, abrogated deferiprone-induced murine thymocyte apoptosis. Bidentate hydroxypyridinones such as deferiprone interact with intracellular zinc pools in a manner distinct from that of DFO, which is a hexadentate iron chelator. Whereas deferiprone acts synergistically with the zinc chelator NNNN-tetrakis(2-pyridylmethyl)ethylenediamine (TPEN) to induce apoptosis, DFO does not. This difference is most likely due to the ability of HPOs but not DFO to “shuttle” zinc onto acceptors such as metallothioneins. By nature of its structure, DFO is larger than deferiprone and is thus less able to access some intracellular zinc pools. Additionally, metal complexes of DFO are more stable than those of HPOs and thus are less likely to donate zinc to other acceptors. The ability of deferiprone to preferentially access zinc pools was also demonstrated by inhibition of a zinc-containing enzyme phospholipase C, particularly when combined with TPEN. These findings suggest that bidentate iron chelators access intracellular zinc pools not available to DFO and that zinc chelation is a mechanism of apoptotic induction by such chelators in thymocytes.

Introduction

Patients with thalassemia and other refractory anemias require regular blood transfusions, and the most common cause of death is iron overload. Currently, desferrioxamine (DFO) is the first line treatment of transfusional iron overload, but it is orally inactive due to its high molecular weight and therefore must be given as subcutaneous infusions. Therefore, the design of an orally active, nontoxic, and selective iron chelator remains an important goal. The ideal iron chelator would prevent or modify iron-mediated pathological processes without undue toxicity.

The bidentate 3-hydroxypyridin-4-ones (HPOs), of which deferiprone has been the most extensively used clinically, are a series of orally active iron chelators. Deferiprone is approximately one-third of the molecular weight of DFO and neutrally charged. Therefore, deferiprone is efficiently absorbed from the gut and enters intracellular metal pools more rapidly than DFO, where it can inhibit metalloenzymes such as ribonucleotide reductase.1 In principle these properties could explain some of the toxic effects of this drug, which include neutropenia and bone marrow aplasia in laboratory animals2,3 and agranulocytosis in some patients.4,5 Although induction of bone marrow hypoplasia is dose- and time-dependent in laboratory animals, agranulocytosis in humans appears unpredictable at a daily dose of 75 mg/kg and has been widely regarded as idiosynchratic.4 Deferiprone also induces thymic atrophy in laboratory animals,6 a feature seen with other hydroxypyridinones.7 Thymic atrophy has also been reported in one clinical case receiving deferiprone at postmortem.8 Furthermore, we have shown that thymocyte apoptosis is induced in vitro by HPOs more rapidly than DFO,9 an observation confirmed by others in proliferating but not resting T lymphocytes.10

The induction and inhibition of apoptosis involves signal transduction pathways, and the response is modified by the concentration of free intracellular divalent metal ions.11 Indeed, the trace metal zinc is an essential component of many transcription factors and signal transduction molecules that regulate aspects of cellular metabolism, and zinc levels influence the regulation of mitosis and apoptosis.12 In particular, zinc supplementation in thymocytes inhibits apoptosis induced by glucocorticoids and γ-irradiation, and in vivo zinc deficiency leads to marked thymic atrophy (acrodermatitis enteropathica) and immunodeficiency.12

Current experimental evidence supports 3 major conclusions regarding zinc and apoptosis12: (1)Zinc deficiency resulting from dietary deprivation or the use of specific chelators induces apoptosis. (2) Zinc supplementation in mice or cell culture prevents apoptotic cell death.(3) Zinc may not affect the triggering events or early signs of apoptosis yet does affect later events, preventing endonucleosomal fragmentation mediated by DNA fragmentation factor 40,13though some reports also suggest that zinc may influence the caspase cleavage events associated with apoptosis.14-16

No chelator is entirely specific for a given metal, and both DFO and deferiprone chelate metals other than iron(III). The stability constant of DFO for zinc is logβ1 = 11. In comparison, deferiprone has a higher affinity for zinc, with a stability constant of logβ3 = 19.1.17 Zinc (Zn2+) forms 3 different complexes with monoprotonated bidentate ligands such as hydroxypiridinones, ZnL+, ZnL2, and ZnL3−. The affinity constants for the interaction between zinc and 3-hydroxypiridin-4-one iron chelators are logK1, 7.35; logK2, 6.38; and logK3, 5.38; respectively, with a pKa of 9.74.18 Thus, in principle, both DFO and deferiprone could chelate clinically significant zinc pools in addition to iron. Indeed, zinc deficiency has been reported in up to 14% of patients receiving long-term treatment with deferiprone,19 and the question as to whether thymic involution may result from zinc depletion by deferiprone has been raised.20 21 To address the relevance of intracellular zinc chelation to “iron chelator”–induced thymocyte apoptosis, we have sought to answer 2 questions. First, do clinically used iron chelators reduce intracellular zinc levels significantly following in vitro or in vivo exposure? Second, can apoptosis induced by such iron chelators be abrogated by zinc supplementation in the diet or by the addition of zinc in vitro?

Materials and methods

Materials

DFO was obtained from Novartis (Basel, Switzerland). The hydroxypiridinone 1,2-dimethyl-3-hydroxypyridin-4-one (CP20, L1, or deferiprone) was synthesized as described2(United Kingdom patent GB 2118176) at the Department of Pharmacy, Kings College, London, United Kingdom, and purity was confirmed by elemental analysis, 1H-NMR, and reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. For incubation with thymocytes, chelators were added from a concentrated stock to a final concentration of 300 μM or 100 μM iron-binding equivalents (IBE). DFO coordinates iron in a 1:1 ratio, whereas HPOs coordinate in a 3:1 ratio. Thus, 3 mol HPO binds the equivalent amount of iron as 1 mol DFO. Dexamethasone (crystalline, Sigma, St Louis, MO) was used at a final concentration of 10−7 M. The zinc chelator NNNN-tetrakis(2-pyridylmethyl)ethylenediamine (TPEN) (crystalline, Sigma) was used at 50 μM unless otherwise indicated.

Cell isolation and culture

Thymocytes were obtained from 10- to 12-week-old male BALB/C mice unless otherwise indicated. Thymi were carefully dissected and contaminating connective tissue removed. Cells were suspended at a concentration of 1.5 × 106/mL in thymocyte medium (RPMI 1640 with 10 mM HEPES [Gibco, Paisley, United Kingdom], 5% fetal calf serum [FCS, Northumbria Biological, United Kingdom], and 2% penicillin/streptomycin [Sigma]) and incubated at 37°C in 4% CO2 with or without drugs for the times indicated. Viability was determined by trypan blue dye exclusion.

Measurements of apoptosis

Quantitative comparisons of apoptosis were performed by measuring the proportion of hypodiploid DNA present in bare thymocyte nuclei by flow cytometry as previously described.22Briefly, cells were collected by centrifugation and resuspended at 1 × 106/mL in fluorochrome (0.1% sodium citrate, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 50 μg/mL propidium iodide in deionized water).

For electrophoretic analysis of DNA fragmentation, 1 × 106 cells were spun at 2000 rpm for 5 minutes and the cell pellets resuspended in 20 μL lysis buffer (500 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 1 M Tris [pH 7.4], 10% sodium lauryl sarkosyl, and 10 mg/mL proteinase K) and incubated at 4°C overnight. After incubation at 50°C for 1 hour, ribnonuclease (0.5 mg/mL) was added for 1 hour and the samples warmed to 70°C. A total of 10 μL loading buffer was added and the DNA loaded into dry wells of a 2% agarose gel containing 0.1 μg/mL ethidium bromide.23

Measurements of intracellular zinc concentrations

Thymocytes at 1 × 106/mL in culture medium were incubated for 24 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2 together with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (as a negative control), deferiprone and DFO (300 μM IBE), and dexamethasone (10−7 M, as a positive control for inducing apoptosis in thymocytes). Thymocytes were treated for 24 hours with the drugs prior to flow cytometric analysis. Zinquin was used to quantify labile levels of free intracellular zinc by spectrofluorimetry. To determine whether the iron chelators deferiprone or DFO altered intracellular zinc levels and, if so, how rapidly this occurred, zinquin was added to thymocytes at a final concentration of 25 μM in Hanks buffered salt solution and incubated for 30 minutes. For spectrophotometric measurements, the fluorescence of unloaded cells (due to autofluorescence and light scattering) was subtracted from the readings to derive zinquin-dependent fluorescence. To derive Fmax, washed thymocytes were lysed in the cuvets by the addition of digitonin (50 μM) and the released zinquin was saturated with 25 μM zinc sulfate. Fmin was derived by the addition of 1 M HCl to quench zinc-dependent fluorescence.24 Fluorescence readings were converted into picomoles of zinc per 106 cells using a standard curve derived by titrating increasing amounts of ZnSO4 into a solution of 3 μM zinquin until the fluorescence was equivalent to that obtained with zinquin-labeled cells. Titration medium was as previously described.25

Zinc's effects on iron chelator–treated thymocytes

A total of 1 × 106 thymocytes in RPMI 1640 medium were preincubated with 200 μM ZnSO4 for 2 hours at 37°C and 5%CO2. Either PBS, dexamethsone (10−7 M), or the iron chelators deferiprone and DFO (300 μM IBE) were then added and the cells incubated for 24 hours. Samples were subsequently treated and analyzed by flow cytometry as described above. To assess potential toxic effects of ZnSO4, samples were also analyzed for viability by trypan blue dye exclusion.

Zinc's effects on iron chelator–treated mice

Groups of 8 BALB/C mice (age 6 to 8 weeks at the start of experiment) were obtained from Harlan Olac (Essex, United Kingdom). The weight of the animals at the commencement of the study was 20 to 25 g. The mice were fed either on a diet of high zinc (500 mg/kg RM3(C) diet [rat and mouse no. 3 breeding diet (c); Special Diet Services, Essex, United Kingdom]) or normal levels of zinc as a control (35 mg/kg RM3(C)), which was administered for 30 days. At this time the drugs, CP20 and PBS (as a control), were given at a concentration of 200 mg/kg intraperitoneally daily for 60 days, while the respective diets were continued. The 4 groups of mice were as follows: (1) control diet, PBS; (2) zinc diet, PBS; (3) control diet, CP20; and (4) zinc diet, CP20. At the end of the experiment mice were killed and their thymi were dissected and analyzed as described above.

Effects of iron loading of thymocytes on chelator-induced apoptosis

Thymocytes at 1 × 106/mL were preincubated for 1 hour with ferric sulfate (100 μM) and washed twice with medium, and then deferiprone or DFO (300 μM IBE) was added with or without the further addition of TPEN (50 μM). The cells were incubated for 24 hours and analyzed by flow cytometry as described above and were assessed for their intracellular zinc levels using zinquin incorporation.

Interactions of zinc and iron chelators

Murine thymocytes at 1 × 106/mL were incubated for 24 hours with the iron chelators deferiprone or DFO at a range of concentrations from 0 to 300 μM/mL in the presence of TPEN (0-50 μM/mL) and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Effect of iron and zinc chelators on the activity of phospholipase C

Phospholipase C was assayed using p-nitrophenylphosphoryl-choline (NPPC; Sigma), which is hydrolyzed to phosphorylcholine and p-nitrophenol by phospholipase C. The p-nitrophenol is chromogenic.26 Phospholipase C, 0.1 mg/mL in 60% sorbitol buffered by 0.25 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.2), was incubated for 30 minutes with PBS and dexamethsone (10−7 M) (as controls) or deferiprone or DFO (300 μM IBE) and/or TPEN (50 μM or 0.1 μM). The reaction was started with the addition of 20 mM NPPC in 0.25 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.2). The assay was carried out at 37°C, and the rate of NPPC hydrolysis by phopholipase C was monitored at 10-minute time intervals (0-60 minutes) by measurement of p-nitrophenol at 410 nm. The molar extinction coefficient of p-nitrophenol at 410 nm in 60% sorbitol solution buffered by Tris-HCl (pH 7.2) is 1.54 × 104, and this was used to calculate the number of moles of NPPC hydrolyzed.

Results

Thymocytes undergo accelerated apoptosis following treatment with iron chelators

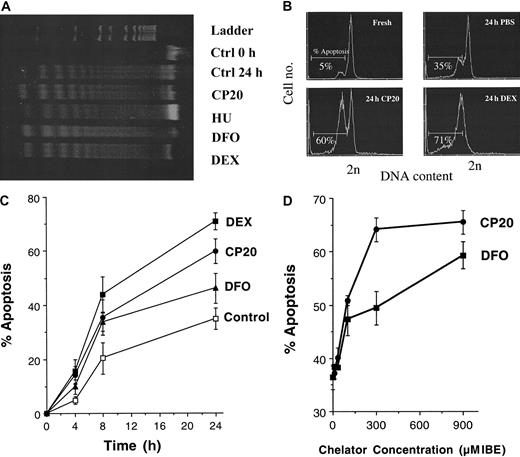

To address whether iron chelators induced apoptosis of murine thymocytes and if this was associated with the DNA fragmentation characteristic of apoptosis, we assessed genomic DNA of thymocytes treated with DFO or deferiprone (CP20) by agarose gel electrophoresis (Figure 1A). “DNA laddering” was evident at 24 hours in control thymocytes incubated in medium (Figure 1A, lane 3) but not at time zero (Figure 1A, lane 2). Thymocytes incubated for 24 hours with CP20 or DFO (Figure 1A, lanes 4 and 6, respectively) showed enhanced DNA fragmentation compared with control cells at 24 hours. Thymocytes treated with dexamethasone (Figure 1A, lane 7), which is known to induce a robust apoptotic response,27 28 also demonstrated enhanced apoptotic laddering compared with control. Hydroxyurea (HU), a ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor, (Figure 1A, lane 5) did not increase apoptosis compared with control at 24 hours. To obtain more quantitative comparisons of the rate and concentration dependence of apoptosis induced by iron chelators, flow cytometric analysis of the hypodiploid DNA from thymocyte nuclei was used. Figure 1B shows the flow cytometric profiles obtained from fresh thymocytes or thymocytes treated for 24 hours with either negative or positive controls, PBS or dexamethsone (10 −7 M), respectively, or with the iron chelator deferiprone (CP20, 300 μM IBE). The DNA content of nuclei from cells scored as subdiploid was quantified. As expected, dexamethasone-treated cells showed a robust increase in subdiploid DNA (70.9% ± 3.2%,P < .001). The percentage of cells with subdiploid DNA was significantly increased in CP20-treated cells (59.8% ± 4.5%) at 24 hours compared with control PBS-treated thymocytes (34.9% ± 4.1%, P < .001). Treatment with DFO (300 μM IBE) also showed an increase in apoptosis compared with control (46.2% ± 5.5%). Additional experiments (n = 4) showed that, by contrast, hydroxyurea 1 mM had minimal effect on apoptosis at 24 hours (39.1% ± 3.7%) compared with control (34.9% ± 4.1%), confirming the findings in Figure 1A. Higher concentrations of hydroxyurea up to 8 mM induced no additional apoptosis (data not shown).

Iron chelators induce apoptosis in thymocytes.

(A) Agarose gel electrophoresis of DNA extracted from fresh murine thymocytes (lane 2) or after 24 hours of incubation with media alone (lane 3) or either CP20, DFO (300 μM IBE, lanes 4 and 6, respectively), HU (1 mM, lane 5), or dexamethasone (DEX) (10−7 M, lane 7). (B) Flow cytometric profiles of freshly isolated thymocytes or thymocytes incubated for 24 hours with either PBS, CP20 (300 μM IBE), or dexamethsone (10−7 M). The cells were washed, fixed in 70% cold ethanol, and stained with propidium iodide for apoptosis measurement by flow cytometry. The data shown are typical flow cytometric profiles obtained following addition of the respective drugs, and the percent of nuclei with less than 2N DNA is given. (C) Thymocytes were incubated for 0, 4, 8, or 24 hours with PBS (control), dexamethasone (10−7 M), or the iron chelators CP20 or DFO (300 μM IBE). The percent apoptosis was measured as indicated in panel B. (D) Thymocytes were incubated for 24 hours with chelator concentrations of 0, 11, 33, 100, 300, and 900 μM IBE and prepared for flow cytometric analysis as indicated above. The data shown are the mean ± SD of 4 independent experiments.

Iron chelators induce apoptosis in thymocytes.

(A) Agarose gel electrophoresis of DNA extracted from fresh murine thymocytes (lane 2) or after 24 hours of incubation with media alone (lane 3) or either CP20, DFO (300 μM IBE, lanes 4 and 6, respectively), HU (1 mM, lane 5), or dexamethasone (DEX) (10−7 M, lane 7). (B) Flow cytometric profiles of freshly isolated thymocytes or thymocytes incubated for 24 hours with either PBS, CP20 (300 μM IBE), or dexamethsone (10−7 M). The cells were washed, fixed in 70% cold ethanol, and stained with propidium iodide for apoptosis measurement by flow cytometry. The data shown are typical flow cytometric profiles obtained following addition of the respective drugs, and the percent of nuclei with less than 2N DNA is given. (C) Thymocytes were incubated for 0, 4, 8, or 24 hours with PBS (control), dexamethasone (10−7 M), or the iron chelators CP20 or DFO (300 μM IBE). The percent apoptosis was measured as indicated in panel B. (D) Thymocytes were incubated for 24 hours with chelator concentrations of 0, 11, 33, 100, 300, and 900 μM IBE and prepared for flow cytometric analysis as indicated above. The data shown are the mean ± SD of 4 independent experiments.

The time dependence of chelator-induced apoptosis was also quantified (Figure 1C). Significant differences between chelator and PBS-treated thymocytes were evident as early as 4 hours after exposure to chelators, with maximal differences at 24 hours (P < .05). The effect of chelator concentration was also examined by incubating thymocytes with increasing concentrations of CP20 or DFO prior to subsequent analysis of apoptosis by flow cytometry (Figure 1D). Increased apoptosis was most obvious at concentrations of 300 μM IBE for CP20 and 900 μM IBE for DFO. Therefore, the iron chelators deferiprone and DFO augment the thymocyte apoptotic program. Thus, chelators used in the treatment of iron overload are potent activators of the classical apoptotic pathway in thymocytes, showing time- and concentration-dependent effects.

Iron chelators reduce levels of intracellular zinc

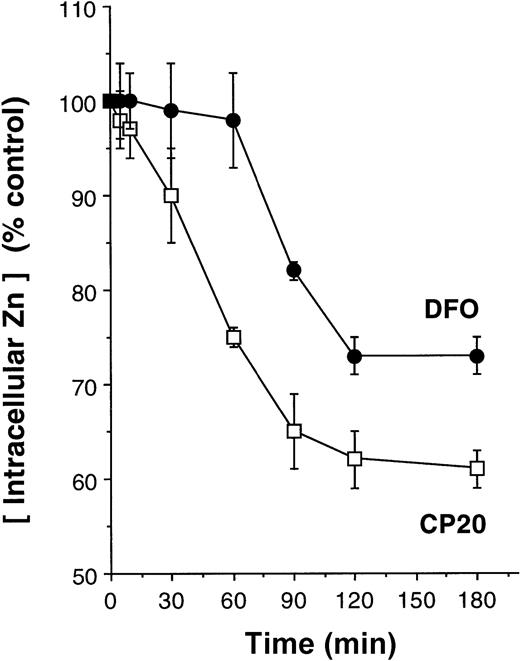

Zinc is known to be an important modulator of apoptosis in thymocytes,29 and zinc chelators induce apoptosis in these cells (see below; Figure 5). We therefore examined whether clinically used iron chelators reduced intracellular levels of zinc and, if so, whether such changes were relevant to the apoptosis induced by iron chelators. To determine concentrations of intracellular zinc we used spectrofluorimetry with zinquin as a detector.24 Zinquin is highly specific for zinc and fluorescence has been shown to be unaffected with the addition of other divalent metals, such as Ca++, Mg2+, Cu2+, Fe2+, Fe3+, Co2+, Ni2+, Hg2+, Ah2+, Li2+, Pb2+, Mn2+, Ba2+, or Al3+.24 Preliminary control experiments in a cell-free system showed that the addition of iron to solutions of zinc and zinquin had no effect on the fluorescence of the free ligand or of the preformed zinc-zinquin complexes (data not shown). Furthermore, the addition of iron chelators deferiprone or DFO (300 μM IBE) had no effect on the fluorescence of preformed zinc-zinquin complexes. To determine whether the iron chelators deferiprone or DFO decreased intracellular zinc levels and, if so, how rapidly this occurred, thymocytes were preloaded with zinquin (25 μM) for 30 minutes before the addition of either CP20 or DFO (300 μM IBE). The addition of deferiprone (CP20) led to immediate reductions in intracellular zinc levels, and by 2 hours this was reduced by 40% (Figure 2). In comparison, zinc levels were sustained for at least 1 hour in thymocytes exposed to DFO; yet, by 2 hours zinc levels had fallen by 30% (Figure 2). These findings are consistent with DFO or deferiprone chelating labile intracellular zinc, leading to secondary dissociation of zinc-zinquin complexes.

Rate of intracellular zinc reductions in thymocytes following treatment with iron chelators.

Thymocytes were preloaded with zinquin (25 μM) for 30 minutes before the addition of PBS (control) or iron chelators CP20 or DFO (300 μM IBE). Zinquin fluorescence was measured by spectrofluorimetry at 390 nm, and the results are expressed as a percentage of control. The data shown are the mean ± SD of 4 independent experiments performed in duplicate.

Rate of intracellular zinc reductions in thymocytes following treatment with iron chelators.

Thymocytes were preloaded with zinquin (25 μM) for 30 minutes before the addition of PBS (control) or iron chelators CP20 or DFO (300 μM IBE). Zinquin fluorescence was measured by spectrofluorimetry at 390 nm, and the results are expressed as a percentage of control. The data shown are the mean ± SD of 4 independent experiments performed in duplicate.

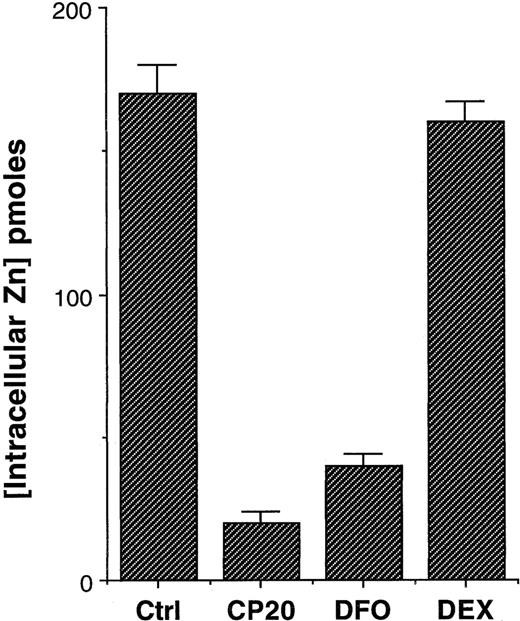

To further confirm that the effects observed were not in some way due to the interaction of the iron chelators with zinquin, rather than effects on the intracellular pool of chelatable zinc, thymocytes were incubated for 24 hours with chelators, and the cells were washed with PBS and then incubated with zinquin (25 μM). Again, rather profound reductions of intracellular zinc were evident in thymocytes treated with deferiprone (CP20) or DFO (Figure3). By contrast, thymocytes treated with dexamethasone had virtually identical levels of intracellular zinc (Figure 3, P < .001). Values calculated from a standard curve indicated that there was a fall in the intracellular levels of zinc from 170 pmol per 106 cells in control cells to 20 and 40 pmol per 106 cells in CP20- and DFO-treated cells, respectively (Figure 3). Thus, either short-term or protracted incubation of thymocytes with iron chelators markedly reduces the intracellular levels of zinquin-detectable zinc. The fall in these levels is both more rapid (Figure 3) and more pronounced (Figure 2) with the HPO deferiprone (CP20) than with DFO. Further experiments over a concentration range of 11 to 300 μM IBE were performed to observe the concentration-dependent effect on intracellular zinc at 24 hours. For CP20 the reduction in intracellular zinc was 17.20% (P < .05), 43% (P < .01), and 89.7% (P < .001) at concentrations of 11, 33, 100, and 300 μM at 24 hours. The respective reductions with DFO were 12.1%, 15.1%, 51.5%, and 76.9%.

Effect of iron chelators on intracellular zinc levels.

Thymocytes were incubated with PBS (control), dexamethazone (10−7 M), or the iron chelators CP20 or DFO (300 μM IBE) for 24 hours. The cells were washed 3 times in PBS prior to the addition of zinquin (25 μM). Zinquin fluorescence was measured by spectrofluorimetry. The data shown are the mean ± SD of 4 independent experiments performed in duplicate.

Effect of iron chelators on intracellular zinc levels.

Thymocytes were incubated with PBS (control), dexamethazone (10−7 M), or the iron chelators CP20 or DFO (300 μM IBE) for 24 hours. The cells were washed 3 times in PBS prior to the addition of zinquin (25 μM). Zinquin fluorescence was measured by spectrofluorimetry. The data shown are the mean ± SD of 4 independent experiments performed in duplicate.

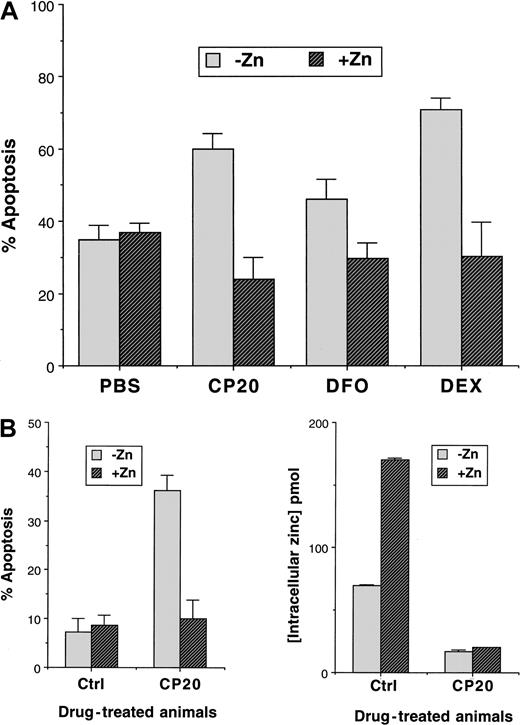

Zinc impairs iron chelator–induced apoptosis in vitro

Having established that iron chelators reduce intracellular levels of zinc, we tested whether zinc supplementation would affect the induction of apoptosis by iron chelators. When zinc was added to thymocyte cultures in the form of zinc sulfate (200 μM), apoptosis was significantly reduced in iron chelator–treated cells (Figure4A). The reduction in apoptosis in control cells treated with ZnSO4 was small (3%) relative to thymocytes exposed to CP20 and ZnSO4 (30% reduction). However, the addition of ZnSO4 also reduced the level of apoptosis in dexamethasone-treated thymocytes by 40% (Figure 4A). Therefore, zinc is an important factor in the propensity of thymocytes to undergo apoptosis.

Effect of zinc on thymocyte apoptosis.

(A) The effects of in vitro addition of zinc sulfate (200 μM) on the apoptotic index of murine thymocytes are shown. Freshly isolated murine thymocytes from 10- to 12-week-old male BALB/C mice were incubated for 24 hours with control (PBS), CP20 or DFO (300 μM IBE), or dexamethasone (10−7 M) prior to be analyzed for apoptosis by flow cytometry. Results are the mean ± SD of 6 independent experiments. (B) The effect of a high-zinc diet on in vivo–induced apoptosis and on the effect on intracellular zinc levels is shown. Mice were fed on either high-zinc or normal diets for 30 days and then administered either control (PBS) or CP20 (200 mg/kg) for 60 days while continuing their respective diets. At the end of this period, the animals were killed and their thymocytes removed immediately. Intracellular zinc levels were measured by the zinquin method and the proportion of cells undergoing apoptosis estimated by flow cytometry after 24 hours overnight in control medium at 37°C (RPMI 1640 medium containing l-glutamine and supplemented with 10% FCS). Results are ± SD of 8 mice on the same regimen.

Effect of zinc on thymocyte apoptosis.

(A) The effects of in vitro addition of zinc sulfate (200 μM) on the apoptotic index of murine thymocytes are shown. Freshly isolated murine thymocytes from 10- to 12-week-old male BALB/C mice were incubated for 24 hours with control (PBS), CP20 or DFO (300 μM IBE), or dexamethasone (10−7 M) prior to be analyzed for apoptosis by flow cytometry. Results are the mean ± SD of 6 independent experiments. (B) The effect of a high-zinc diet on in vivo–induced apoptosis and on the effect on intracellular zinc levels is shown. Mice were fed on either high-zinc or normal diets for 30 days and then administered either control (PBS) or CP20 (200 mg/kg) for 60 days while continuing their respective diets. At the end of this period, the animals were killed and their thymocytes removed immediately. Intracellular zinc levels were measured by the zinquin method and the proportion of cells undergoing apoptosis estimated by flow cytometry after 24 hours overnight in control medium at 37°C (RPMI 1640 medium containing l-glutamine and supplemented with 10% FCS). Results are ± SD of 8 mice on the same regimen.

Dietary zinc supplementation abolishes iron chelator–induced apoptosis in vivo

The observed protective effects of zinc in iron chelator–induced apoptosis could be due to an ex vivo culture artifact. We therefore addressed the relationship of iron, zinc, and the thymocyte apoptosis in mice. Groups of age-matched male BALB/C mice (age 10-12 weeks) were fed with either a normal or a zinc-supplemented diet for 3 months (see “Materials and methods”) and then administered either deferiprone (CP20, 200 mg/kg intraperitoneally) or control PBS for 60 days while continuing on the standard or zinc-supplemented diets. At the end of this interval the animals were killed, the thymi were immediately removed, and thymocyte zinc levels and apoptosis were compared in each group of mice. Mice fed on the high-zinc diet had increased levels of intracellular thymocyte zinc (170 pmol/106 cells for PBS) compared with the mice fed on the standard diet (70 pmol/106 cells for PBS) as measured by zinquin incorporation (Figure 4B). Furthermore, mice on the high-zinc diet receiving daily CP20 had lower levels of zinc (17 pmol/106cells) than those receiving PBS only (P < .001). In mice receiving the standard diet, significantly lower zinc levels were also seen in CP20-treated mice compared with controls (20 and 70 pmol/106 cells for deferiprone [CP20]– and PBS-treated mice respectively, P < .001). Furthermore, oral zinc supplementation (Figure 4B) abolished the proapoptotic effects of CP20 in murine thymocytes, reducing the apoptotic index from 36% back to levels seen in control cells (10.1%). Thus, dietary supplementation of zinc decreases iron chelator–induced thymocyte apoptosis.

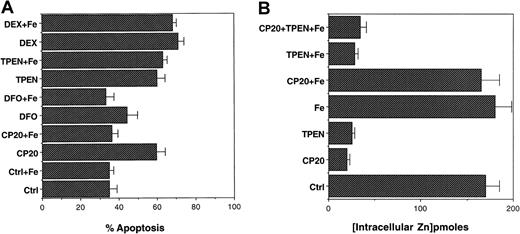

Chelation of intracellular zinc induces thymocyte apoptosis

The above findings suggested an important role for zinc chelation in thymocyte apoptosis induced by iron chelators. To address whether zinc depletion by iron chelators was the apoptotic mechanism, we added exogenous iron to thymocytes prior to challenging the cells with chelators for iron (CP20, DFO) or zinc (TPEN). When thymocytes were pretreated with ferric sulfate, no significant increase in apoptosis was observed in control thymocytes, demonstrating that increasing iron alone does not decrease viability. Furthermore, no effect of adding ferric sulfate on zinquin fluorescence was observed, indicating that loading with iron does not affect intracellular zinc pools.

When thymocytes preloaded with ferric sulfate were exposed to the iron chelators, there was a decrease in the amount of apoptosis induced by CP20 or DFO, but iron loading failed to protect thymocytes from apoptosis induced by the zinc chelator TPEN (Figure5A). Thus, this contrasts with the ability of ZnSO4 to block both iron and zinc chelator–induced apoptosis. Importantly, the inhibition of CP20- and DFO-induced apoptosis by preloading with ferric sulfate was associated with an abrogation of the reduction in intracellular zinc levels by these chelators (Figure 5B). This suggests that in the presence of excess iron, such as would occur in iron overload, iron will be chelated in preference to zinc and reduces the risk of zinc chelation–induced apoptosis. However, when this balance is less than optimal zinc chelation can also occur and would result in thymocyte apoptosis.

Effect of iron supplementation on CP20-, DFO-, and TPEN-induced thymocyte apoptosis.

(A) Thymocytes were preincubated for 2 hours with ferric sulfate (100 μM) prior to the addition of the iron chelators CP20 and DFO (100 μM IBE) or the zinc chelator TPEN (50 μM). The cells were spun, fixed in 70% cold ethanol, and stained with propidium iodide for apoptosis measurement by flow cytometry. The data shown are the mean ± SD of 4 independent experiments performed in triplicate. (B) Thymocytes were incubated with PBS, CP20 (300 μM IBE), TPEN (50 μM), ferric sulfate (100 μM), CP20 plus iron, TPEN plus iron, or CP20 plus iron plus TPEN for 24 hours. The cells were washed 3 times prior to the addition of zinquin (25 μM). Zinquin fluorescence was measured by spectrofluorimetry. The data shown are the mean ± SD of 4 independent experiments performed in duplicate.

Effect of iron supplementation on CP20-, DFO-, and TPEN-induced thymocyte apoptosis.

(A) Thymocytes were preincubated for 2 hours with ferric sulfate (100 μM) prior to the addition of the iron chelators CP20 and DFO (100 μM IBE) or the zinc chelator TPEN (50 μM). The cells were spun, fixed in 70% cold ethanol, and stained with propidium iodide for apoptosis measurement by flow cytometry. The data shown are the mean ± SD of 4 independent experiments performed in triplicate. (B) Thymocytes were incubated with PBS, CP20 (300 μM IBE), TPEN (50 μM), ferric sulfate (100 μM), CP20 plus iron, TPEN plus iron, or CP20 plus iron plus TPEN for 24 hours. The cells were washed 3 times prior to the addition of zinquin (25 μM). Zinquin fluorescence was measured by spectrofluorimetry. The data shown are the mean ± SD of 4 independent experiments performed in duplicate.

Interactions of zinc and iron chelators in thymocyte apoptosis

A property that differentiates metal chelation by DFO from that of deferiprone is the greater stability of metal chelate complexes with DFO. This is because 1:1 chelation (hexadentate) is inherently more stable than 3:1 metal chelation. The combination of their small molecular size, neutral charge, and a tendency for metal-ligand complexes to dissociate at low concentrations provide HPOs with the ideal properties for shuttling iron or zinc from pools unavailable to larger chelators onto ligands that can act as a stable sink for such metals. To further substantiate zinc chelation as an apoptotic mechanism, experiments were undertaken to evaluate effects of combinations of CP20 or DFO with the zinc chelator TPEN over a range of concentrations. These experiments demonstrated that the apoptotic effect of CP20 (Table 1) was antagonistic with high concentrations of TPEN (25-50 μM) but was synergistic with low concentrations of TPEN (0.1-5 μM). Isobologram plots, which are used to visualize drug interactions, confirmed the synergistic interaction of CP20 with TPEN at concentrations of TPEN between 0.1 and 5 μM (graphs not shown). By contrast, when different concentrations of DFO (0-300 μM IBE) were added in combination with TPEN (0-50 μM), no obvious apoptotic synergy or antagonism was apparent (Table1). These findings are thus consistent with CP20 being able to access pools of zinc unavailable to TPEN or DFO. The synergy between CP20 as low as 1μM and TPEN up to 5μM further suggests that CP20 may shuttle zinc molecules from available pools and donate that zinc to TPEN.

Effect of chelator combinations on thymocyte apoptosis

| TPEN, μM . | DFO or CP20, μM IBE . | % apoptosis + DFO . | % apoptosis + CP20 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 33.9 ± 4.2 | 33.9 ± 4.2 |

| 0.1 | 0 | 29.4 ± 1.8 | 25.9 ± 2.4 |

| 5 | 0 | 55.4 ± 4.2† | 46.3 ± 2.4* |

| 0 | 1 | 30.5 ± 3.1 | 33.0 ± 1.6 |

| 0 | 10 | 40.6 ± 2.2 | 39.4 ± 2.8 |

| 0 | 100 | 41.6 ± 3.2 | 55.3 ± 2.1† |

| 0 | 300 | 49.3 ± 5.1* | 71.1 ± 4.3‡ |

| 0.1 | 1 | 31.4 ± 3.6 | 66.6 ± 5.1‡ |

| 0.1 | 10 | 32.4 ± 2.8 | 76.7 ± 3.4‡ |

| 0.1 | 100 | 34.0 ± 1.8 | 71.8 ± 5.4‡ |

| 0.1 | 300 | 36.9 ± 2.2 | 84.9 ± 1.8‡ |

| 5 | 1 | 45.3 ± 4.8* | 79.7 ± 2.6‡ |

| 5 | 10 | 47.4 ± 2.8* | 83.7 ± 3.9‡ |

| 5 | 100 | 48.0 ± 4.1* | 81.1 ± 5.3‡ |

| 5 | 300 | 48.5 ± 3.2* | 80.7 ± 3.2‡ |

| 50 | 1 | 51.2 ± 0.8† | 29.4 ± 4.3 |

| 50 | 10 | 54.7 ± 4.3† | 27.4 ± 2.3 |

| 50 | 100 | 48.6 ± 2.2* | 28.5 ± 2.6 |

| 50 | 300 | 52.0 ± 3.3† | 32.0 ± 1.4 |

| TPEN, μM . | DFO or CP20, μM IBE . | % apoptosis + DFO . | % apoptosis + CP20 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 33.9 ± 4.2 | 33.9 ± 4.2 |

| 0.1 | 0 | 29.4 ± 1.8 | 25.9 ± 2.4 |

| 5 | 0 | 55.4 ± 4.2† | 46.3 ± 2.4* |

| 0 | 1 | 30.5 ± 3.1 | 33.0 ± 1.6 |

| 0 | 10 | 40.6 ± 2.2 | 39.4 ± 2.8 |

| 0 | 100 | 41.6 ± 3.2 | 55.3 ± 2.1† |

| 0 | 300 | 49.3 ± 5.1* | 71.1 ± 4.3‡ |

| 0.1 | 1 | 31.4 ± 3.6 | 66.6 ± 5.1‡ |

| 0.1 | 10 | 32.4 ± 2.8 | 76.7 ± 3.4‡ |

| 0.1 | 100 | 34.0 ± 1.8 | 71.8 ± 5.4‡ |

| 0.1 | 300 | 36.9 ± 2.2 | 84.9 ± 1.8‡ |

| 5 | 1 | 45.3 ± 4.8* | 79.7 ± 2.6‡ |

| 5 | 10 | 47.4 ± 2.8* | 83.7 ± 3.9‡ |

| 5 | 100 | 48.0 ± 4.1* | 81.1 ± 5.3‡ |

| 5 | 300 | 48.5 ± 3.2* | 80.7 ± 3.2‡ |

| 50 | 1 | 51.2 ± 0.8† | 29.4 ± 4.3 |

| 50 | 10 | 54.7 ± 4.3† | 27.4 ± 2.3 |

| 50 | 100 | 48.6 ± 2.2* | 28.5 ± 2.6 |

| 50 | 300 | 52.0 ± 3.3† | 32.0 ± 1.4 |

Thymocytes were incubated with CP20, DFO, or TPEN alone or in combination with each other for 24 hours. The cells were washed, fixed in 70% cold ethanol, and stained with propidium iodide for apoptosis measurement by flow cytometry. The data shown are the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments done in duplicate.

P < .01, as measured by the Studentt test.

P < .05, as measured by the Studentt test.

P < .001, as measured by the Studentt test.

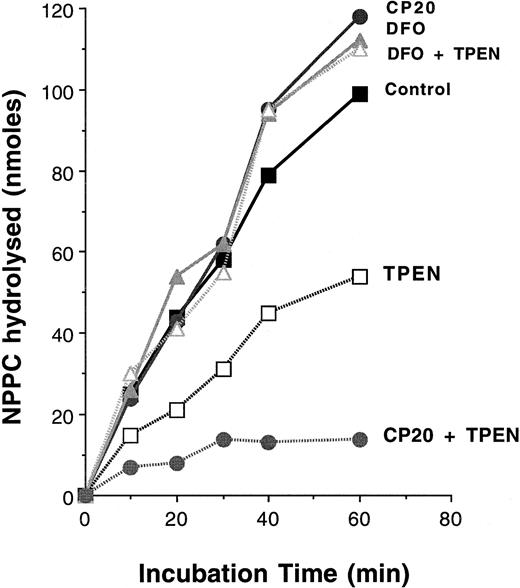

The effect of iron and zinc chelators on the activity of the zinc-coordinated enzyme phospholipase C

The above experiments suggested that HPOs are able to act synergistically with zinc chelators to induce thymocyte apoptosis. The very low concentrations of HPOs required to induce apoptosis in the presence of TPEN, together with considerations of the stability constants, suggests that HPOs shuttle zinc from sites normally unavailable to TPEN alone onto TPEN. To test this issue we used a cell-free system containing the zinc-coordinated enzyme phospholipase C. The effects of the addition of PBS (control), the iron chelators CP20 or DFO (300 μM IBE), or the zinc chelator TPEN (50 μM) on phospholipase C activity was assessed (Figure6). At high concentrations (300 μM IBE), both the iron chelators CP20 and DFO inhibited phospholipase C activity (by 80% and 70%, respectively), whereas dexamethasone had no effect (data not shown). Similarly, as expected, TPEN (50 μM) also inhibited phospholipase C activity (by 90%). Importantly, when very low concentrations of CP20 (1 μM) plus TPEN (0.1 μM) were incorporated into the assay—concentrations that alone did not inhibit phospholipase C—a 90% inhibition was observed, whereas this did not occur with low concentrations of DFO plus TPEN (Figure 6). Therefore, iron chelators, in particular CP20, are capable of chelating zinc ions in vitro and in vivo, and CP20 appears capable of subsuming zinc ions that are bound to proteins.

Effect of iron chelators on the zinc-containing enzyme phospholipase C.

Purified phospholipase C, 0.1 mg/mL in 60% sorbitol, was incubated for 30 minutes with either PBS (control), the iron chelators CP20 or DFO (300 μM IBE), the zinc chelator TPEN (50 μM), or CP20 and DFO (1 μM) in combination with TPEN (0.1 μM). Following this interval, NPPC (20 mM) was added and phospholipase C activity assessed by spectrophotometry over 1 hour at 410 nm. The data shown are the mean ± SD of 4 independent experiments performed in duplicate.

Effect of iron chelators on the zinc-containing enzyme phospholipase C.

Purified phospholipase C, 0.1 mg/mL in 60% sorbitol, was incubated for 30 minutes with either PBS (control), the iron chelators CP20 or DFO (300 μM IBE), the zinc chelator TPEN (50 μM), or CP20 and DFO (1 μM) in combination with TPEN (0.1 μM). Following this interval, NPPC (20 mM) was added and phospholipase C activity assessed by spectrophotometry over 1 hour at 410 nm. The data shown are the mean ± SD of 4 independent experiments performed in duplicate.

Discussion

Thymocytes undergo rapid apoptosis after exposure to various agents, including glucocorticoids, ionizing radiation, and environmental agents. Several lines of evidence suggest that modulation of intracellular zinc levels plays a key physiologic role in thymocyte apoptosis.29 Numerous in vitro studies have also shown a direct stimulatory effect of zinc depletion on apoptosis, particularly following treatment with membrane-permeant zinc chelators such as TPEN.30-33 Conversely, changes in the susceptibility of cells to undergo apoptosis when high levels of exogenous zinc are provided may explain resistance of cells to certain toxic agents, such as glucocorticoids and ionizing radiation in thymocytes.34,35 However, the exact role that zinc plays in the regulation of apoptosis remains ambiguous. Low concentrations of intracellular zinc accelerate apoptosis of lymphoid and myeloid cell lines in vitro36,37 as well as in human leukemia cells, rat splenocytes, and thymocytes.29,35,38 However, there are several scenarios where zinc fails to block apoptosis. For example, cyclophosphamide induces a form of apoptosis in lymphocytes that is resistant to the protective effects of zinc.39 40

The findings in this study show that exposure of iron chelators to murine thymocytes lowers intracellular zinc to levels associated with thymocyte apoptosis. The findings further show that apoptosis is induced both in vitro and in vivo by exposure to deferiprone and that zinc inhibits this process. The addition of deferiprone to thymocytes in vitro reduces intracellular zinc levels within 1 hour of incubation (Figure 2), and sustained incubation of thymocytes with deferiprone or DFO results in a 9-fold or 4.5-fold reduction in intracellular zinc levels, respectively (Figure 3). The more pronounced and rapid rate of reduction in intracellular levels of zinc in thymocytes treated with deferiprone versus DFO appears due to the faster accumulation of deferiprone into intracellular metal pools compared with DFO3 and also to the higher affinity of deferiprone for zinc (logβ3 = 19.11; compared with DFO, logβ1 = 11).17 The concentrations of deferiprone used for the in vitro experiments are clinically relevant because, following oral administration of deferiprone to iron-overloaded patients, peak concentrations of 150 to 450 μM have been described.41 Current clinical use of DFO with slow infusions either intravenously or subcutaneously typically results in plasma concentrations of approximately 10 μM,42 a concentration at which our findings show that significant reduction in intracellular zinc is minimal. It is also likely that zinc-DFO complexes are more stable than those of zinc with HPOs such as deferiprone, because at low concentrations deferiprone donates zinc to intracellular proteins.17 Fluctuating intracellular levels of deferiprone, such as are likely to occur following oral administration, could result in the redistribution of zinc from one target within a cell to another.

In vitro experiments established that zinc inhibits the induction of apoptosis by iron chelators (Figure 4A). Preloading cells with iron in vitro, as previously observed in HL60 cells,10 partially abrogated the apoptotic effects of DFO and deferiprone (Figure 5A,B). However, this also abrogated decrements of zinc levels by these chelators. This suggests that iron-overloaded cells will be protected from the risk of zinc chelation. Although consistent with zinc chelation as the predominant mechanism of apoptotic induction, these findings might also be interpreted as consistent with an iron chelation mechanism. Consideration of the speciation plots for iron and zinc binding within cells is helpful in considering the implications of iron-loading cells on chelator-induced apoptosis. If a plasma concentration of 30 μM deferiprone is considered (a mid-range clinical value), a change in the labile intracellular iron pool has a significant effect on the free chelator available to bind labile zinc. In nonoverloaded cells, the labile iron pool concentration in resting cells has been estimated between 1 or 2 μM 43 and 3 μM 44 and increases with iron loading.45Speciation plots for iron(III) binding to deferiprone at pH 7.0 show that an increase of labile iron from 1 to 10 μM decreases the unbound free ligand concentration from 27 μM to only 3 μM, making chelator virtually unavailable for zinc chelation (R. Hider, personal communication, May 2001). Hence, iron overload would be predicted to inhibit zinc chelation at clinically relevant concentrations of deferiprone. The findings in Figure 5B support the view that iron loading of cells inhibits decrements of intracellular zinc by deferiprone. The inhibition of thymocyte apoptosis by zinc supplementation to chronically dosed mice also argues for zinc chelation as a key mechanism of induction of thymocyte apoptosis with deferiprone. Chronic in vivo administration of deferiprone resulted in decreased levels of thymocyte zinc, particularly in zinc-loaded animals (Figure 4B), and supplementation of the diet with zinc in vivo reduced apoptosis induced by deferiprone. The studies of synergistic apoptosis inducing interactions of deferiprone with the zinc chelator TPEN (see below) also support zinc chelation by deferiprone as a key mechanism for apoptotic induction in thymocytes. Thus, while iron chelation cannot be excluded as an apoptotic mechanism in these cells, there is persuasive evidence for zinc chelation being a key factor.

The exact mechanisms by which intracellular zinc depletion by iron chelators augments apoptosis remain unresolved. While it is arguable that the effects of zinc in vitro are nonphysiologic and may act at the final stage of thymocyte apoptosis by inhibiting the DNA fragmentation factor 40 endonucleases,13 this is unlikely to occur in vivo where zinc supplementation inhibits thymocyte apoptosis induced by iron chelators (Figure 4B). While the protective effects of zinc on apoptosis were originally attributed to its inhibition of a Ca++- and Mg2+-dependent endonuclease, this concept has now been challenged by a number of observations demonstrating the inhibition of apoptosis during the “execution” caspase cleavage phase of cell death.14,40 The particular intracellular zinc pool that is targeted by the iron chelators also requires consideration. As with iron, much of the intracellular zinc is unavailable for immediate chelation because it is tightly complexed to metalloenzymes and not readily exchangeable.12 Using the fluorescent zinc probe zinquin, the intracellular labile chelatable pool has been previously found to be 10% to 20% of the total cellular zinc, and several researchers46 47 suggest that the important fraction of zinc probably resides in a relatively small pool that exchanges its content of zinc with both intracellular and extracellular pools.

Because the affinity of HPOs for zinc is less than for zinquin,17 deferiprone would not be predicted to chelate additional zinc pools to TPEN unless the smaller dimensions of deferiprone allowed access in the zinc pool unavailable to TPEN. Isobologram experiments using deferiprone and the zinc chelator TPEN (not shown) suggest that they interact with each other with respect to the induction of apoptosis and are likely to act on a shared pool of metals. The finding that low concentrations of deferiprone had a synergistic effect on TPEN-induced apoptosis (Table 1) suggests that deferiprone may access pools of chelatable zinc not available to TPEN. Although TPEN has a higher affinity for zinc (logβ2 = 16), because of its larger molecular weight and hexadentate structure it is likely that some pools of zinc are less available to TPEN than to the smaller hydroxypiridinone molecules such as deferiprone. This notion is supported by the findings that DFO does not synergize with TPEN (Table1); although DFO has a similar iron binding constant to deferiprone, its hexadentate structure prevents access to metal pools hidden within protein clefts.48 In support of this concept, experiments using the zinc-containing enzyme phospholipase C showed that low concentrations of both deferiprone and TPEN, but not DFO and TPEN, block enzyme activity (Figure 6). These findings are consistent with a shuttling mechanism for deferipronelike chelators and support the concept that zinc chelation by deferiprone is likely to be the principal mechanism of thymocyte apoptosis. A shuttling effect of low molecular weight chelators onto more stable higher weight chelators is well recognized for iron and other metals,49,50 with there often being a marked synergism of metal removal when the use of a small kinetically labile ligand is combined with that of a larger hexadentate chelator. Typical examples are nitrilotriacetate/DFO with iron removal,51 penicillanimine/DTPA with copper removal,52 and salicylic acid/ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid with plutonium removal.50 Shuttling has been suggested as a mechanism by which the availability of nontransferrin-bound iron to DFO may be increased.53,54Shuttling of iron has recently also been suggested as a mechanism for enhanced action of deferiprone when combined simultaneously with DFO.55

These studies were conducted specifically to address whether thymic atrophy and apoptosis of thymocytes could result from zinc chelation by chelators used for the therapy of iron overload. There are, however, important differences between thymocytes and other cell types that have been found to be targets of chelator toxicity. The thymocytes studied in this paper were predominantly nonproliferating cells: Cell cycle analysis shows that only 5.4% ± 0.9% of cells were in S phase either after immediate isolation or 24 hours of culture. This is in contrast to the cycling peripheral blood T lymphocytes studied by Hileti and coworkers.10 Furthermore, whereas hydroxyurea increased apoptosis in stimulated blood lymphocytes described by Hileti et al, there was negligible increase in thymocyte apoptosis, even at 8 mM concentrations of hydroxyurea. Therefore, the mechanisms of apoptotic induction by iron chelators in proliferating cells are likely to differ from those seen in thymocytes.

The differences observed between the rates of apoptotic induction and the rates of reduction in intracellular zinc by deferiprone and DFO may have clinical relevance and possibly explain why zinc deficiency is observed in a proportion of patients receiving deferiprone.19,56 Why zinc deficiency should be more frequent in those patients with coexistent diabetes56 is not immediately apparent. Recent studies on patients treated with deferiprone show no obvious change in immune function, including peripheral blood T lymphocyte numbers after 1 year of treatment5 or longer.57 However, although these studies included some children, the mean age in both studies was 18 years, and thymic involution begins within 1 year of birth. Furthermore, T-cell numbers do not directly reflect thymic involution, and an effect of deferiprone on the thymic atrophy is unlikely to be detected from the simple measurement of peripheral T-cell numbers or subsets.

In the search for orally active iron chelators with reduced toxicity, it may be important to consider the relative rates at which they may lower intracellular zinc levels. The finding that deferiprone appears to shuttle zinc onto more stable chelators of zinc, even at very low concentrations of the chelator, suggests that zinc moves within intracellular pools in this fashion. In principle, metallothioneins and other natural chelators of zinc could act as zinc acceptors in a manner analogous to TPEN. Finally, these findings suggest that when using combinations of chelators, such as deferiprone and DFO, the potential for the shuttling of metals other than iron needs to be considered. The effect of such combinations on intracellular pools of zinc and apoptosis certainly merits systematic examination.

The authors thank Professor Robert Hider for kindly providing CP20, Dr P. Zalewski for zinquin, and Arnold Pizzey for help with flow cytometric analysis.

Supported by Novartis Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland) by NIH grants CA76379 and DK44158 (J.L.C.), Cancer Center CORE grant CA21765, and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Kirsteen H. Maclean, Dept of Biochemistry, St Jude Children's Research Hospital, 332 N Lauderdale, Memphis, TN 38105; e-mail: kirsteen.maclean@stjude.org.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal