Abstract

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is an incurable leukemia characterized by the slow but progressive accumulation of cells in a CD5+ B-cell clone. Like the nonmalignant counterparts, B-1 cells, CLL cells often express surface immunoglobulin with the capacity to bind autologous structures. Previously there has been no established link between antigen-receptor binding and inhibition of apoptosis in CLL. In this work, using primary CLL cells from untreated patients with this disease, it is demonstrated that engagement of surface IgM elicits a powerful survival program. The response includes inhibition of caspase activity, activation of NF-κB, and expression of mcl-1, bcl-2, and bfl-1 in the tumor cells. Blocking phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K), a critical mediator of signals through the antigen receptor, completely abrogated mcl-1 induction and impaired survival in the stimulated cells. These data support the contention that CLL cell survival is promoted by antigen for which the malignant clone has affinity, and suggest that pharmacologic interference with antigen-receptor–derived signals has potential for therapy in patients with CLL.

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is characterized by the abnormal expansion of cells in a CD5+ (B-1) cell clone.1,2 In this distinctive form of leukemia, most of the malignant cells are in the G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle.3,4 Disease results from the progressive accumulation of tumor cells which do not proliferate rapidly, but fail to undergo death.5 In this regard, CLL provides a paradigm for studies of apoptosis inhibition in lymphocytes. In contrast to other B-cell neoplasms such as follicular lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, and mantle cell lymphoma that are characterized by specific cytogenetic abnormalities and dysregulated oncogenes, CLL is not distinguished by a common genetic defect.6 Rather, the diagnosis of CLL is determined by the morphologic and phenotypic properties of the slowly dividing B cells.

Despite their prolonged survival in vivo, most CLL cells do not survive for more than a few days in vitro. A longstanding puzzle for investigators is the propensity of CLL B cells to undergo spontaneous apoptosis in culture. Several lines of evidence support that nonmalignant cells and other host elements extrinsic to CLL cells provide survival signals to the tumor cells in vivo. These factors would include bone marrow stromal cells,7 immune complexes in the context of accessory leukocytes,8 “nurse-like” cells,9 and soluble cytokines such as interleukin 4 (IL-4)10 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα).11,12 On the basis of observations that CD40 ligation in CLL B cells is a powerful stimulus to induction of NF-κB13,14 and survival,13-16 we have proposed that CLL tumor growth in vivo would be promoted by inflammatory elements such as CD40 ligand (CD154), cytokines, and antigens to which the tumor cells bind.4 17

Like nonmalignant B-1 cells, CLL cells usually express surface IgM (sIgM) with the capacity to bind multiple infectious and autologous structures.18-21 In the murine system it is established that the presence of autologous antigens for which the B-cell receptor (BCR) has affinity can positively influence nonmalignant CD5+ B-cell fate and differentiation.22 An emerging body of literature indicates CLL tumor cells often bear mutated Ig gene sequences,23-25 suggesting that the cells have interacted with antigens in vivo. However, the intracellular signaling pathways by which antigens mediate survival in murine and human B-1 cells, and in leukemic B cells, are largely unknown.

The purpose of this study was to determine how sIgM engagement affects CLL cell survival, and to identify key molecular components of an antigen-receptor–driven survival program in the leukemic cells. Here, using freshly isolated cells from more than 20 patients with CLL, we determined that BCR crosslinking favors survival in a process characterized by caspase inhibition, induction of NF-κB, and expression of antiapoptotic molecules including bcl-2, mcl-1, and bfl-1. The antiapoptotic effects of sIgM engagement in CLL cells were magnified when CD40 was also engaged, and were dependent on phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K) activity. Taken together, these data elucidate how antigen extrinsic to a malignant B cell can sustain its survival, and reveal a signaling pathway suitable for therapeutic targeting in this disease.

Materials and methods

CLL samples

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from heparinized peripheral blood samples of patients with CLL who had not received chemotherapy for at least 6 months prior to study. The samples were obtained by phlebotomy upon request by the patients' physicians, according to a New York Presbyterian-Weill Medical Center IRB–approved protocol (#0995-048). The diagnosis of CLL was confirmed in each case by a hematopathologist at the New York Presbyterian Hospital according to standard criteria including expression of CD5, CD19, and CD23 in an expanded B-cell clone.6 The samples were coded by ID number, as they were received in our laboratory.

Cell isolation and culture

Mononuclear cells were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque density centrifugation, and the proportion of leukemic (CLL) cells determined by FACS analysis for coexpression of CD5 and CD19. In cases for which the B cells represented less than 95% of the isolated cells, T cells were depleted by rosetting with sheep erythrocytes (Colorado Serum, Denver, CO). CLL cells were cultivated at 3 × 106cells/mL, at 37°C with 5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Gemini Biological Products, Calabasas, CA) and penicillin, streptomycin, and L-glutamine (C-50). The following reagents were added, as indicated: anti-CD40 mAb (clone M3, murine IgGκ1, 2μg/mL; R&D, Minneapolis, MN); anti-IgM (polyclonal goat anti-human IgM F(ab′)2 fragments, 10μg/mL except in dose-response experiment; American Qualex, San Clemente, CA); anti-CD23 (EBVCS2, murine IgGκ1, 2μg/mL, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA); F(ab′)2 fragments of polyspecific goat antibody (10μg/mL, American Qualex); dexamethasone (10−7 M; Sigma, St Louis, MO). For experiments with the PI3-K inhibitor LY294002, cells were preincubated with LY294002 (final concentration 50 μM; Sigma) in C-50 media for 1 hour prior to stimulation.

Apoptosis assays

Apoptosis was quantitated by the propidium iodide (PI) and annexin V methods. For measurement of subdiploid DNA using PI, 3 × 105 cells were harvested, permeabilized in PI staining solution (PI 50μg/mL, sodium citrate 0.1%, Triton X-100 0.1%, RNase A 20μg/mL), and stored in the dark at 4°C for at least 24 hours prior to analysis by FACS. For studies using annexin V, 1 × 106 cells were washed in annexin-binding buffer with Ca++ and incubated with annexin V–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) according to the manufacturer's instructions (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) prior to FACS analysis.

Statistical considerations

In Figures 1 and 6 the apoptosis data include absolute (“raw”) numbers for the percent of cells undergoing apoptosis in particular assays. Figure 3 and Table1 include summarized data which are based on the determination of specific apoptosis (SA) for stimulated cells in each circumstance. This calculation was required to account for the variable baseline apoptosis rates among samples, and reflects the absolute difference between apoptosis in an experimental circumstance and the baseline for a particular case (media only): SA = Δ = (apoptosis %, experimental circumstance)-(apoptosis %, media only).

sIgM and CD40 engagement favor survival of CLL B cells.

(A) Purified CLL cells were subjected to BCR engagement using goat anti-human IgM F(ab′)2 fragments over a range of doses. (B) Purification of CLL cells was confirmed by FACS for coexpression of CD5 and CD19. (C) The purified cells were cultured for 48 hours with media only, or stimulated by CD40 ligation (anti-CD40 mAb, murine IgGκ1, 2μg/mL), IgM engagement (goat anti-human IgM F(ab′)2, 10μg/mL), CD40 and IgM engagement, or dexamethasone (10−7 M). The percentage of apoptotic cells for each circumstance, measured by annexin V–FITC, is indicated. (D) Apoptosis was determined for cells of another case by the PI method after culture with media only, with anti-IgM F(ab′)2, or with a control polyspecific goat F(ab′)2. The percent of cells with subdiploid DNA (apoptotic percent) is indicated for each histogram. (E) Purified CLL cells were stimulated by CD40 and/or IgM engagement, dexamethasone, or exposed to control antibodies (anti-CD23, murine IgGκ1, 2 μg/mL; or polyspecific goat F(ab′)2, 10 μg/mL) and evaluated for apoptosis by the PI method. Error bars represent the SEM.

sIgM and CD40 engagement favor survival of CLL B cells.

(A) Purified CLL cells were subjected to BCR engagement using goat anti-human IgM F(ab′)2 fragments over a range of doses. (B) Purification of CLL cells was confirmed by FACS for coexpression of CD5 and CD19. (C) The purified cells were cultured for 48 hours with media only, or stimulated by CD40 ligation (anti-CD40 mAb, murine IgGκ1, 2μg/mL), IgM engagement (goat anti-human IgM F(ab′)2, 10μg/mL), CD40 and IgM engagement, or dexamethasone (10−7 M). The percentage of apoptotic cells for each circumstance, measured by annexin V–FITC, is indicated. (D) Apoptosis was determined for cells of another case by the PI method after culture with media only, with anti-IgM F(ab′)2, or with a control polyspecific goat F(ab′)2. The percent of cells with subdiploid DNA (apoptotic percent) is indicated for each histogram. (E) Purified CLL cells were stimulated by CD40 and/or IgM engagement, dexamethasone, or exposed to control antibodies (anti-CD23, murine IgGκ1, 2 μg/mL; or polyspecific goat F(ab′)2, 10 μg/mL) and evaluated for apoptosis by the PI method. Error bars represent the SEM.

Clinical information, CD38 expression, and response to surface IgM engagement

| Case ID . | Sex/age (y) . | Illness duration (y) . | WBC (× 103/μL) . | Purification (%) . | CD38+ (%) . | IgM-mediated apoptosis inhibition (%)* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31 | M/74 | 3.5 | 158 | 94 | 45 | − 2.4 |

| 47 | F/78 | 6 | 102 | 96 | 33 | 13 |

| 58 | F/80 | 6 | 50 | 90 | 44 | 47 |

| 69 | F/80 | 8 | 142 | 91 | 3.3 | 17 |

| 72 | M/43 | 7 | 106 | 96 | 20.4 | 19 |

| 78 | M/57 | 2.5 | 37.8 | 90 | 34 | 27 |

| 86 | M/76 | 5 | 72.9 | 85 | 10.5 | − 6.1 |

| 89 | M/82 | 10 | 26.2 | 87 | 1.7 | − 3.7 |

| 96 | M/48 | 12 | 69.5 | 97 | 2.1 | 14.5 |

| 104 | M/70 | 10 | 79.1 | 86 | 91 | 12.6 |

| 106 | F/65 | 9 | 69.7 | 93 | ND | 1.8 |

| 108 | M/66 | 7 | 52.5 | 79 | 96 | 13.3 |

| 111 | F/60 | 3 | 136.9 | 92 | .1 | 18.1 |

| 114 | M/52 | < 1 | 216 | 95 | 16 | 15.6 |

| 121 | F/79 | 11 | 68 | 67 | 17 | 13 |

| Case ID . | Sex/age (y) . | Illness duration (y) . | WBC (× 103/μL) . | Purification (%) . | CD38+ (%) . | IgM-mediated apoptosis inhibition (%)* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31 | M/74 | 3.5 | 158 | 94 | 45 | − 2.4 |

| 47 | F/78 | 6 | 102 | 96 | 33 | 13 |

| 58 | F/80 | 6 | 50 | 90 | 44 | 47 |

| 69 | F/80 | 8 | 142 | 91 | 3.3 | 17 |

| 72 | M/43 | 7 | 106 | 96 | 20.4 | 19 |

| 78 | M/57 | 2.5 | 37.8 | 90 | 34 | 27 |

| 86 | M/76 | 5 | 72.9 | 85 | 10.5 | − 6.1 |

| 89 | M/82 | 10 | 26.2 | 87 | 1.7 | − 3.7 |

| 96 | M/48 | 12 | 69.5 | 97 | 2.1 | 14.5 |

| 104 | M/70 | 10 | 79.1 | 86 | 91 | 12.6 |

| 106 | F/65 | 9 | 69.7 | 93 | ND | 1.8 |

| 108 | M/66 | 7 | 52.5 | 79 | 96 | 13.3 |

| 111 | F/60 | 3 | 136.9 | 92 | .1 | 18.1 |

| 114 | M/52 | < 1 | 216 | 95 | 16 | 15.6 |

| 121 | F/79 | 11 | 68 | 67 | 17 | 13 |

ID indicates identification number; WBC, white blood cell count; ND, not done.

Apoptosis inhibition reflects the absolute difference between the percentage of annexin V-binding cells after culture with medium or anti-IgM F(ab′)2 fragments for 48 hours. Positive values indicate inhibition of apoptosis; negative values indicate enhancement of apoptosis.

Apoptosis inhibition, as shown in Figure 3 and Table 1, was determined by −Δ and is thereby positive for conditions in which the treatment reduced apoptosis. The statistical significance of differences among these results was evaluated using the Student t test (2-tailed) using the data analysis “toolpack” in Excel (Version 2000; Microsoft, Seattle, WA). Potential correlations were evaluated by regression analyses, also using Excel.

Fluorescence microscopy

Cytospins were prepared using 150 000 CLL cells per slide and fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (10 minutes, 4°C). The cytospins were washed in Tris buffered saline (TBS), permeabilized (0.1% Triton X-100 in TBS) for 5 minutes at 25°C, washed again and air-dried prior to application of Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) with the DNA binding dye 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Visualization and photography were performed using a Nikon Labophot 2 microscope.

Western blot analyses

Cell lysates were prepared using lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 1% NP40) with protease inhibitors (aprotinin, leupeptin, pepstatin A, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), trypsin-chymotrypsin inhibitor) and, as appropriate, with the phosphatase inhibitor Na orthovanadate (1 μM). Protein concentrations were determined using the Bio-rad protein assay (Bio-rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). For each study, a constant amount of protein was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), transferred to polyvinylidenefluoride (PVDF) by using a semidry transfer apparatus, blocked and exposed to primary antibodies for the following human proteins: actin (rabbit Ab; Sigma); phospho-Akt and total Akt (rabbit Abs; New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA); bcl-2 (mouse mAb, IgG1; Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA); mcl-1 (rabbit Ab, S19 clone, Santa Cruz); or polyADP-ribose polymerase (PARP, murine IgG; Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). The blots were washed and exposed to appropriate horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies: goat anti-mouse (Jackson Immunoresearch) or donkey anti-rabbit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway NJ), washed again and imaged using an enhanced chemilumiscence detection system (Amersham). For some analyses the blots were reprobed after exposure to stripping buffer (100 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 2% SDS, 62.5 mM Tris pH 6.8) for 30 minutes at 55°C.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays

Nuclear extracts were prepared using a minimum of 5 × 106 cells as we have described,14 and electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were performed using a T4 kinase end-labeled probe with an NF-κB–binding site from the Igκ promotor (5′-GGGACTTTCC-3′). For each EMSA, 4 μg of nuclear protein was incubated for 10 minutes with DNA binding mix (2 μg poly (dI-dC), 0.25% NP-40, 5% glycerol, 10 mM Tris HCl, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, and 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid [EDTA] at 25°C prior to incubation for 15 minutes with 20 000 cpm of labeled probe. For competition assays, 50 molar excess of unlabeled Oct-1– or NF-κB–specific oligonucleotides were added prior to the addition of labeled probes. The samples were evaluated by electrophoresis in 7% acrylamide and autoradiography.

Ribonuclease protection assay

RNAs were analyzed using Riboquant ribonuclease protection assay kit hAPO-2c (Pharmingen). For each ribonuclease protection assay (RPA), 1.5 μg of RNA was hybridized with the labeled template set. To confirm the identity of each protected fragment, the electrophoretic migration distance of each experimental band was plotted against a standard curve which was generated based on the migration distances of the labeled probes, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Densitometric analyses were performed using Scion NIH Image software, developed at the U.S. National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD) and available on the Internet (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/).

Results

Surface IgM engagement promotes CLL cell survival

Based on our model for the role of CD40 ligand and other immune stimulatory factors in promoting CLL cell survival,4,17 we hypothesized that antigen-receptor engagement provides survival signals to CLL B cells, as these cells express surface sIgM with the capacity to bind autologous structures.18-21 To determine the consequences of sIgM engagment in CLL, we obtained primary tumor cells directly from the peripheral blood of untreated patients with CLL, and applied to those cells an F(ab′)2 preparation of goat anti-human IgM. This type of antibody preparation was selected to avoid any potential Fc receptor–mediated effects of intact immunoglobulin in the B cells. In initial experiments we subjected the CLL cells to sIgM engagement over a range of anti-IgM doses and observed dose-dependent inhibition of apoptosis over the range of 500 ng/mL to 10 μg/mL, above which there was no significant change (Figure 1A). The dose response was significant (correlation coefficient 0.853, Pvalue .0147); we used the 10 μg/mL dose of anti-IgM to evaluate BCR-mediated survival signals thereafter. Based on the established cross talk between CD40 and BCR survival pathways in other B-cell systems26-29 and the powerful role of CD40 ligation in CLL cell survival pathways,13-16 we subjected the CLL cells to sIgM engagement in the presence or absence of an agonistic antibody to CD40. For purposes of comparison, and also as a positive control for CLL cell apoptosis in vitro, we exposed the cells to dexamethasone (10−7 M) an established inducer of CLL cell death.30 31

Due to the fact that previous reports suggested that CLL cells undergo apoptosis upon sIgM engagement,32-34 we elected to confirm our finding that CLL cell survival is favored by BCR crosslinking using several methods for apoptosis measurement. Leukemic B cells were purified (Figure 1B) and stimulated for 48 hours in culture prior to apoptosis measurement by the annexin V method (Figure 1C). In this representative case, the spontaneous apoptosis rate of 32% was reduced to 18% upon CD40 ligation, and to 19% upon sIgM engagement alone. Upon stimulation through both receptors there was a clear and dramatic reduction in the proportion of apoptotic cells (11%). As anticipated, exposure of the cells to dexamethasone resulted in augmented apoptosis (70%). We also used the PI method to quantify the proportion of stimulated cells with subdiploid (cleaved) DNA. In a typical analysis the spontaneous apoptosis rate was 41% (Figure 1D). This was reduced to 3.8% upon BCR engagement using anti-IgM F(ab′)2, but was minimally affected by exposure to a control preparation of polyspecific goat F(ab′)2 fragments (36%). The lack of effect of isotype-matched control antibody preparations was confirmed in analyses using cells from 7 cases. Of note, sIgM engagement reduced apoptosis in CLL cells exposed to dexamethasone (Figure 1E).

We observed typical morphologic changes of apoptosis, or lack thereof, in stimulated CLL cells by staining with the DNA-binding dye DAPI and fluorescence microscopy (Figure 2A-C). As is evident in low-power micrographs, among the BCR-stimulated cells there were many more cells with smooth plasma membranes and diffuse nuclear DNA content than among those exposed to media. Consistent with our previous results, dexamethasone treatment led to a reduction in cell number and viability. High power images (insets) demonstrate characteristic features of apoptosis, with nuclear condensation and plasma membrane blebbing, in many of the cells with media and in most of the cells with dexamethasone. Spontaneous caspase activation was evident in CLL cells cultured with media, based on cleavage of the broad caspase substrate PARP to yield an 85-kd cleavage product (Figure2D). PARP cleavage was reduced in cells stimulated by sIgM crosslinking. Consistent with our previous observations that soluble anti-CD40 mAb is a potent inducer of NF-κB activity but has only slight effects on CLL cell survival in most cases,14caspase inhibition did not occur in cells exposed only to soluble anti-CD40 mAb. However, in this case and 4 others examined, CD40 and sIgM engagement together reduced caspase activity more dramatically than did sIgM crosslinking alone. As expected, dexamethasone exposure enhanced PARP cleavage in the CLL cells.

sIgM engagement inhibits characteristic morphologic features of apoptosis, such as nuclear condensation and plasma membrane blebbing, and inhibits caspase activity in CLL cells.

(A-C) Stimulated CLL cells were evaluated by fluorescence microscopy after staining with DAPI. Low-power micrographs (original magnification 20x) with representative fields and high-power micrographs (insets, original magnification 100x) are included. (D) Cleavage of the broad caspase substrate PARP was determined by western blot analyses. The PARP proform (116 kd) and cleavage product (85 kd) are indicated by arrows.

sIgM engagement inhibits characteristic morphologic features of apoptosis, such as nuclear condensation and plasma membrane blebbing, and inhibits caspase activity in CLL cells.

(A-C) Stimulated CLL cells were evaluated by fluorescence microscopy after staining with DAPI. Low-power micrographs (original magnification 20x) with representative fields and high-power micrographs (insets, original magnification 100x) are included. (D) Cleavage of the broad caspase substrate PARP was determined by western blot analyses. The PARP proform (116 kd) and cleavage product (85 kd) are indicated by arrows.

Data summary in a series of 15 cases

To confirm that our observations regarding the antiapoptotic effects of sIgM engagement represented a pattern common to CLL cases, we measured apoptosis at a common time point (48 hours) by the annexin V method in 15 unselected chemotherapy-naive samples (Table 1, Figure3). According to these measurements, sIgM engagement reduced apoptosis in 12 of 15 CLL cases (80%). The mean apoptosis inhibition upon sIgM engagement for all cases was 13% (standard error of the mean [SEM] 3.4%). For the 12 cases in which there was a survival effect, the mean inhibition upon sIgM engagement was 18% (SEM 3.1%). Consistent with previous studies,4 14 soluble mAb to CD40 provided weak survival signals to the CLL cells of most cases (mean inhibition 6%, SEM 1.2%). However, when both receptors (IgM and CD40) were stimulated, apoptosis inhibition was apparent in 13 of the 15 cases, and the degree of inhibition was intensified (mean 23%, SEM 4.6%). Dexamethasone exposure increased apoptosis in all cases, although the degree of specific (dexamethasone-induced) apoptosis varied from 6% to 50%.

Summary of apoptosis data in a series of 15 CLL cases.

Freshly isolated CLL B cells from 15 unselected cases were cultured with media only or stimulated using anti-CD40 mAb, anti-IgM, or dexamethasone. Apoptosis in each circumstance was measured after 48 hours by annexin V–FITC binding and FACS analysis. As outlined in “Materials and methods,” “apoptosis inhibition” reflects the difference between the apoptosis percent in the experimental circumstance and that measured in the same cells after 48 hours with media only. Each symbol represents the results for a particular case, and the horizontal bars represent the mean for specific apoptosis inhibition in each circumstance. P values were determined by application of the Student t test, based on comparison of results in each experimental circumstance with those for media only.

Summary of apoptosis data in a series of 15 CLL cases.

Freshly isolated CLL B cells from 15 unselected cases were cultured with media only or stimulated using anti-CD40 mAb, anti-IgM, or dexamethasone. Apoptosis in each circumstance was measured after 48 hours by annexin V–FITC binding and FACS analysis. As outlined in “Materials and methods,” “apoptosis inhibition” reflects the difference between the apoptosis percent in the experimental circumstance and that measured in the same cells after 48 hours with media only. Each symbol represents the results for a particular case, and the horizontal bars represent the mean for specific apoptosis inhibition in each circumstance. P values were determined by application of the Student t test, based on comparison of results in each experimental circumstance with those for media only.

The differences in apoptosis rates for stimulated CLL cells in each circumstance, as compared with cells placed in culture with media only, were statistically significant according to the 2-tailed Studentt test. In the analysis of all 15 cases, we determined aP value of .00159 for the difference in apoptosis rates between cells stimulated by sIgM engagement and those with media. This finding indicates the high probability that a survival program is elicited in most CLL cells stimulated through the BCR. Based on previous reports supporting the existence of 2 subtypes of CLL, we analyzed our data by subsets and specific variables including patient's age, sex, duration of disease, peripheral blood leukocyte count, and expression of CD38. However, we did not find a correlation between apoptosis inhibition upon sIgM engagement and any of these factors. In particular, there was no relationship between CD38 expression and BCR-mediated apoptosis inhibition (Pearson correlation coefficient 0.208). Although it is possible that other determinants would define a CLL subset with distinct behavior in this regard, we have not observed 2 distinct subsets in terms of sIgM-responsiveness.

Together with CD40 ligation, BCR engagement promotes NF-κB activity in CLL

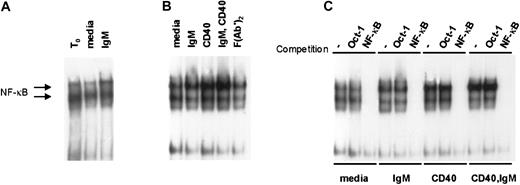

We hypothesized that antigen-receptor engagement in vivo contributes to the constitutive high levels of NF-κB activity observed in primary CLL cells.14 To determine whether BCR engagement augments NF-κB activity in CLL we used EMSA to measure NF-κB binding activity in stimulated CLL cells. In 6 cases examined, we observed a subtle but reproducible increase in NF-κB activity upon sIgM engagement alone. Two representative examples of NF-κB induction upon IgM engagement are shown in Figure4. Consistent with our hypothesis that NF-κB activity in CLL is stimulated by sIgM engagement in vivo, there was reduced activity upon culture with media for 4 hours relative to the NF-κB activity detected in the same cells analyzed at the time of isolation (t0). On the other hand, the waning NF-κB activity was recovered in cultured CLL cells exposed to anti-IgM (Figure 4A). Figure 4B shows data for another representative case, in which we examined also the effects of stimulation through the CD40 receptor. As we and others have reported previously,4,13 14 there was marked induction of NF-κB activity upon CD40 ligation alone. Consistent with the effects observed for CLL cell survival, NF-κB induction was most intense in CLL cells stimulated by both receptors (CD40 and sIgM) (Figure 4B). Finally, to confirm the specificity of the NF-κB signal in stimulated CLL cells, we used a cold oligonucleotide competition assay with 50-fold molar excess of unlabeled probe for either Oct-1 or NF-κB (Figure 4C). These observations indicate that BCR engagement promotes NF-κB activity in CLL and that together with CD40 ligation, sIgM crosslinking would favor transcription of NF-κB target genes in the tumor cells.

IgM and CD40 engagement in CLL cells promote NF-κB activity in CLL cells.

(A) Nuclear extracts were prepared upon purification of the cells (t0), or after 4 hours of culture with media or anti-IgM, and evaluated by EMSA with a labeled probe for NF-κB binding activity. (B) Cells from another case were stimulated in culture for 4 hours prior to preparation of nuclear extracts and evaluation by EMSA. (C) To confirm the specificity of the signals for NF-κB activity, EMSA was performed using the extracts of panel B in the absence or presence of 50-fold molar excess of competitive, unlabeled Oct-1– or NF-κB–binding oligonucleotides.

IgM and CD40 engagement in CLL cells promote NF-κB activity in CLL cells.

(A) Nuclear extracts were prepared upon purification of the cells (t0), or after 4 hours of culture with media or anti-IgM, and evaluated by EMSA with a labeled probe for NF-κB binding activity. (B) Cells from another case were stimulated in culture for 4 hours prior to preparation of nuclear extracts and evaluation by EMSA. (C) To confirm the specificity of the signals for NF-κB activity, EMSA was performed using the extracts of panel B in the absence or presence of 50-fold molar excess of competitive, unlabeled Oct-1– or NF-κB–binding oligonucleotides.

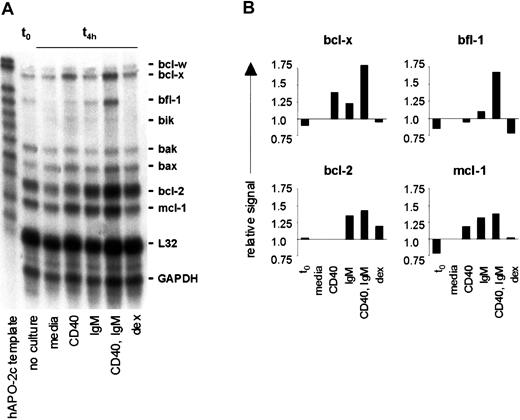

BCR engagement results in expression of mcl-1, bcl-2, and bfl-1

Based on our findings that CLL cells demonstrate high levels of NF-κB activity, which is enhanced by CD40 ligation and engagement of sIgM, and observations that several antiapoptotic bcl-2 family members are NF-κB target genes,35-37 we investigated whether CD40 ligation and sIgM engagement determine expression of specific bcl-2 family members in CLL cells by RPA. In a representative analysis, transcripts for bcl-x, bfl-1, bak, bax, bcl-2, and mcl-1 were evident in unstimulated CLL cells immediately upon isolation (t0), and the most intense signals corresponded to protected transcripts for bcl-2 and mcl-1 (Figure5A). Without stimulation (media only), transcripts for bfl-1, bcl-2, and mcl-1 were reduced within 4 hours in vitro.

CD40 and IgM crosslinking result in transcription of mcl-1, bcl-2, and bfl-1 in CLL B cells.

(A) CLL cells were purified from the peripheral blood of an untreated patient and RNAs isolated from unstimulated cells (t0) or after 4 hours with media only, anti-CD40 mAb, anti-IgM, or dexamethasone. Expression of mRNA encoding specific bcl-2 family members was measured by RPA. The data shown represent those of 5 similar analyses. (B) Densitometric evaluation of these RPA results, with fold induction based on comparison with the L32 signal for each lane.

CD40 and IgM crosslinking result in transcription of mcl-1, bcl-2, and bfl-1 in CLL B cells.

(A) CLL cells were purified from the peripheral blood of an untreated patient and RNAs isolated from unstimulated cells (t0) or after 4 hours with media only, anti-CD40 mAb, anti-IgM, or dexamethasone. Expression of mRNA encoding specific bcl-2 family members was measured by RPA. The data shown represent those of 5 similar analyses. (B) Densitometric evaluation of these RPA results, with fold induction based on comparison with the L32 signal for each lane.

In stimulated CLL cells there was a common pattern among 5 cases examined: bcl-x transcripts were augmented in cells triggered by CD40 (with and without sIgM engagement); bfl-1 transcripts were increased in cells stimulated by either CD40 or sIgM, and were highest in cells activated via both receptors. Bak and bax transcripts were not particularly affected by any stimulation, although bak transcripts were generally reduced upon culture, and bax transcripts were increased. Bcl-2 transcripts were readily evident in CLL cells in all circumstances but in each case were greatest upon stimulation through both CD40 and sIgM. In comparison to cells with media, mcl-1 transcripts were augmented upon sIgM crosslinking alone, CD40 engagement, or both stimuli. Induction of bcl-xL, bfl-1, bcl-2, and mcl-1 were confirmed by densitometry and normalization of each signal to that for L32 in the same lane (Figure 5B). To eliminate the possibility that our results were a nonspecific effect of the stimulatory antibodies used, we exposed CLL cells to control antibody preparations (polyspecific goat F(ab′)2 and murine anti-CD23, as in Figure 1E) and observed that bcl-x, bfl-1, bcl-2, and mcl-1 expression were unchanged (not shown).

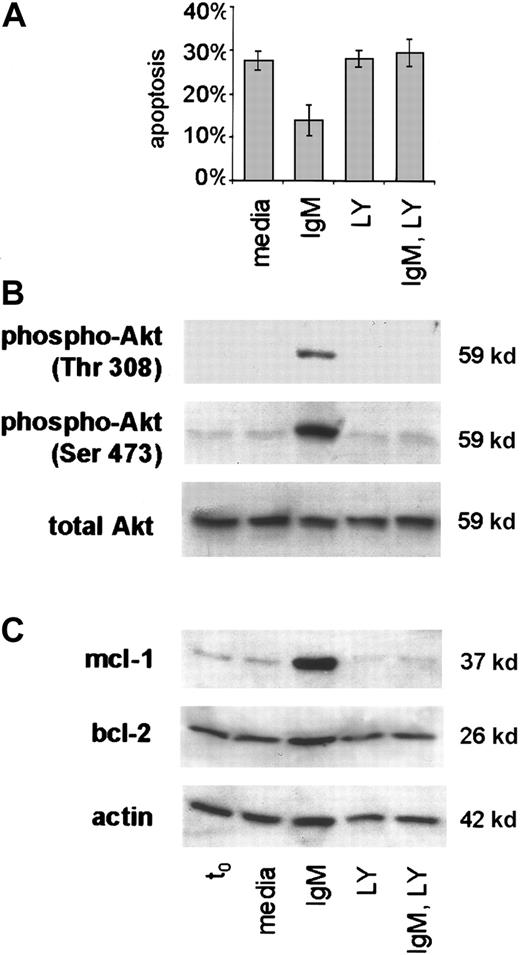

PI3-K inhibition precludes BCR-mediated survival signals in CLL

Mcl-1 is expressed in germinal-center B cells, but its role in antigen-receptor–mediated survival of lymphocytes has not been previously appreciated. Of note, and in contrast to our findings that CLL cells express both mcl-1 and bcl-2, there is usually a reciprocal pattern of mcl-1 and bcl-2 expression in human lymphocytes.38,39 Based on established links between BCR engagement and activation of PI3-K,40,41 and on evidence that bcl-2 and mcl-1 expression are induced upon PI3-K activation in some cell systems,42 43 we considered that interference with PI3-K activity might prevent BCR-mediated survival signals in CLL. To address this possibility we subjected primary CLL cells from 4 cases to sIgM engagement in the absence or presence of LY294002, an inhibitor to PI3-K (Figure 6). In initial experiments, we tested the LY294002 compound over a range of doses and determined that there was no toxic effect or change in viability in otherwise unstimulated CLL cells with doses up to 75 μM (not shown).

PI3-K inhibition blocks BCR-mediated survival signals in CLL.

Freshly isolated CLL B cells were placed in culture with media only or with anti-IgM without or upon preincubation with the PI3-K inhibitor LY294002. (A) Apoptosis was measured by the PI method in the treated cells of 4 cases. Error bars indicate the SEM. (B) Phospho-Akt (thr 308, ser 473) was determined by western blot analyses with lysates taken at the t0 and 1 hour timepoints and specific antibody to the phosphorylated and total forms of Akt. (C) Mcl-1 protein was evaluated using lysates from t0 and 24 hours. The blot was stripped and probed also for bcl-2 and actin.

PI3-K inhibition blocks BCR-mediated survival signals in CLL.

Freshly isolated CLL B cells were placed in culture with media only or with anti-IgM without or upon preincubation with the PI3-K inhibitor LY294002. (A) Apoptosis was measured by the PI method in the treated cells of 4 cases. Error bars indicate the SEM. (B) Phospho-Akt (thr 308, ser 473) was determined by western blot analyses with lysates taken at the t0 and 1 hour timepoints and specific antibody to the phosphorylated and total forms of Akt. (C) Mcl-1 protein was evaluated using lysates from t0 and 24 hours. The blot was stripped and probed also for bcl-2 and actin.

Application of the PI3-K inhibitor resulted in loss of survival in CLL cells stimulated with anti-IgM (Figure 6A). As anticipated, protein kinase B (Akt), an immediate downstream substrate of PI3-K, was phosphorylated at each of 2 critical residues (Thr 308, Ser 473) in CLL cells upon sIgM engagement in the absence of LY294002. However, this did not occur in the presence of inhibitor, and total Akt protein remained constant in all of the treated cells (Figure 6B). Of note, in each case studied, PI3-K inhibition completely abrogated mcl-1 induction in CLL cells stimulated through the BCR (Figure 6C). Whereas changes in bcl-2 at the protein level were subtle, the effects of PI3-K inhibition on mcl-1 expression were marked. Based on these findings, we conclude that PI3-K activity is necessary for mcl-1 induction and survival of CLL cells upon antigen-receptor engagement.

Discussion

In these studies we provide novel evidence that sIgM engagement inhibits apoptosis in primary CLL cells by instigation of a survival program which includes caspase inhibition, induction of NF-κB activity, and expression of bcl-2–related molecules including bcl-2, bfl-1, and mcl-1. We observed that each of these survival effects was heightened when costimulation was provided to the CLL cells through CD40. These findings provide the first demonstration of a molecular pathway by which antigen extrinsic to a malignant B cell can support its survival. The data add to the emerging story that CLL cells receive survival signals in vivo from factors in the microenvironment that are absent upon isolation of the cells in vitro.2,7 8

The observation that BCR engagement influences transcriptional regulation and survival in CLL cells has important implications regarding the possible role for autologous or infectious antigens in CLL pathogenesis. Although the degree of apoptosis inhibition upon sIgM engagement alone was not great (between 10% and 20% for most cases), we contend that such a difference could have a vital impact on a large tumor cell population in vivo. Just as CD40 ligand has more powerful effects on CLL cell survival than soluble antibody to CD40,14 we speculate that real, complex antigens in vivo might have a larger effect on CLL cell survival than do the F(ab′)2 preparations of anti-human IgM, such as we have used in these experiments. Moreover, our findings support that the effects of antigen binding in CLL would be most dramatic in the context of concomitant stimulation by CD40 ligand, as predicted by our model.4 These data indicate that NF-κB activity in CLL would be elevated highly when both receptors are stimulated, and support that expression of antiapoptotic NF-κB target genes, such as bcl-xL and bfl-1,35-37 would be promoted through this activity in vivo. We suggest also that expression of CD40 and BCR-dependent survival signals contributes to resistance to Fas (CD95)–mediated apoptosis in CLL, as has been observed in CLL cells (E.S., unpublished data, 1997; Kitada et al,15and Wang et al44) and which occurs in nonmalignant B cells stimulated through both receptors.45

There are several possible explanations for why our results differ from previous reports that suggest CLL cells can be induced to undergo apoptosis upon BCR engagement.32-34 In an early study of apoptosis in CLL, McConkey and coworkers made the important observation that DNA fragmentation could be induced in CLL cells upon exposure to glucocorticoids, and also noted that cells in 4 of 7 cases underwent apoptosis upon IgM engagement.32 It is possible that the small number of cases studied, differences in antibody reagents, and other factors such as the concentration of CLL cells in culture contribute to the observed differences. In a later study, Osario and coworkers determined that CD6 engagement by antibody alters the response to sIgM binding in CLL cells.33 There are several significant differences in methods between the work of Osario and colleagues and ours, including that group's use of cells that had been frozen and thawed prior to the apoptosis assays and a system of sIgM engagement which involved crosslinking by intact (secondary) antibody in precoated plates. In an intriguing set of observations, Zupo and coworkers determined that in CD38+ CLL cells, sIgD crosslinking resulted in CLL cell differentiation, whereas sIgM ligation resulted in cell death.34 One possible explanation for the difference here is that those investigators selected CD38+ CLL cells in each case for their investigations. We agree with those authors that CD38 expression in CLL cells is not “black and white,” but occurs over a broad range among cells in many of the cases (data not shown). It may be the case that the behavior of CD38+ cells, which are presumably less differentiated, is distinct. Nonetheless, our data, obtained through the strict use of freshly isolated, unselected CLL cells, F(ab′)2 antibody to IgM, and experiments which included control antibody preparations, indicate that the majority of CLL cells from most cases respond to BCR engagement by inhibition of apoptosis. Our findings are entirely consistent with the biology of an indolent tumor in which the malignant B cells generate sIgM with the capacity to bind autologous antigens.

The finding that Akt was phosphorylated normally in CLL cells upon sIgM engagement was anticipated based on studies demonstrating Akt activation by PI3-K upon BCR crosslinking in other human B cell systems, as has been reported by others.40 On the other hand, there are reports of abnormal calcium flux and impaired signal transduction in some CLL cells stimulated through the BCR.46-48 In addition, defects in the BCR-signaling apparatus are described based on abnormal expression of CD79b (Igβ). These are ascribed in some cases to somatic mutations of the gene or to abnormal splicing of CD79b transcripts.49 50 Thus far we have observed Akt phosphorylation upon sIgM engagement in 4 out of 4 CLL cases analyzed by western blot, as shown in Figure 6. Although it is possible that upon further investigation a subset of CLL cases will be identified in which the cells behave distinctly in terms of Akt phosphorylation upon IgM engagement, we suspect that differences in BCR-mediated signals in CLL, as described by others, lie downstream or parallel to the Akt pathway.

There are important therapeutic implications of our observations regarding antigen-receptor–mediated induction of mcl-1 in CLL cells. In the context of previous studies demonstrating that mcl-1 expression is a significant predictor of CLL cell resistance to chemotherapy,51 our data suggest that the presence of antigens to which tumor cells bind would reduce the response to chemotherapy in vivo. Therefore, if one could determine the antigen or antigens to which a particular patient's tumor binds, and eliminate that antigen or antigens, chemotherapies might be more effective. In addition, our findings identify a novel function for PI3-K–dependent Akt activation and mcl-1 expression in survival of B lymphocytes stimulated through the antigen receptor. Although the specific autologous or infectious antigens promoting CLL cell survival must differ among patients, our data indicate that interference with the intracellular PI3-K pathway would block antigen-driven mcl-1 expression and survival in CLL cells. These findings support development of novel pharmacologic agents aimed at the BCR-mediated survival pathway, which might potentiate the response to therapy in CLL cells binding any antigen.

The authors wish to thank Professor Paul Glasserman of Columbia University for expert help and guidance in statistical analyses of our findings. We also thank the patients with CLL and their physicians for provision of samples.

Supported by The William H. Kearns Foundation, and National Institutes of Health grants CA-71589 (E.S.) and CA-68155 (HC.L). R.P. was supported by The Sass Foundation for Medical Research.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Elaine Schattner, Division of Hematology and Medical Oncology, Rm C-640, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, 1300 York Ave, New York, NY 10021; e-mail:ejsch@med.cornell.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal