Preclinical models have shown that transplantation of marrow mesenchymal cells has the potential to correct inherited disorders of bone, cartilage, and muscle. The report describes clinical responses of the first children to undergo allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT) for severe osteogenesis imperfecta (OI), a genetic disorder characterized by defective type I collagen, osteopenia, bone fragility, severe bony deformities, and growth retardation. Five children with severe OI were enrolled in a study of BMT from human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–compatible sibling donors. Linear growth, bone mineralization, and fracture rate were taken as measures of treatment response. The 3 children with documented donor osteoblast engraftment had a median 7.5-cm increase in body length (range, 6.5-8.0 cm) 6 months after transplantation compared with 1.25 cm (range, 1.0-1.5 cm) for age-matched control patients. These patients gained 21.0 to 65.3 g total body bone mineral content by 3 months after treatment or 45% to 77% of their baseline values. With extended follow-up, the patients' growth rates either slowed or reached a plateau phase. Bone mineral content continued to increase at a rate similar to that for weight-matched healthy children, even as growth rates declined. These results suggest that BMT from HLA-compatible donors may benefit children with severe OI. Further studies are needed to determine the full potential of this strategy.

Introduction

Bone marrow mesenchymal cells can differentiate to a variety of tissues including bone, cartilage, muscle, and fat.1-7 Thus, in principle, bone marrow transplantation (BMT) could provide effective therapy for disorders that involve cells derived from mesenchymal precursors.8One attractive candidate is osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) or “brittle bone disease,” a genetic disorder caused by defects in type I collagen, the major structural protein of the extracellular matrix of bone.9-11 Patients with severe OI have numerous painful fractures, progressive deformities of the limbs and spine, retarded bone growth, and short stature. There is no cure for OI, and only one class of drugs, the bisphosphonates, which can reduce or prevent bone resorption, appear to have therapeutic potential.12-14

Ideally, therapy for OI should be directed toward improving bone strength by improving the structural integrity of collagen and thereby the quality of the bone.15,16 Although the existence of circulating osteoblast progenitors is controversial,17preclinical studies have demonstrated that whole bone marrow contains cells that can engraft and become competent osteoblasts after transplantation.18 Moreover, because collagen is a secreted product, even a low level of osteoblast engraftment might be beneficial to OI patients.6 19 Guided by this rationale, we undertook a pilot study to demonstrate the feasibility of transplanting bone marrow–derived mesenchymal cells in children with OI.

Although providing a basis for continued testing of this strategy, our initial analysis20 included only 6 months of clinical follow-up and did not directly compare results with those for control patients or healthy children. Here we demonstrate improvement in the linear growth, total body bone mineral content (TBBMC), and fracture rate of 3 children with severe OI (2 children from the original report20) who had engraftment of donor osteoblasts and 18-36 months of clinical follow-up.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patients

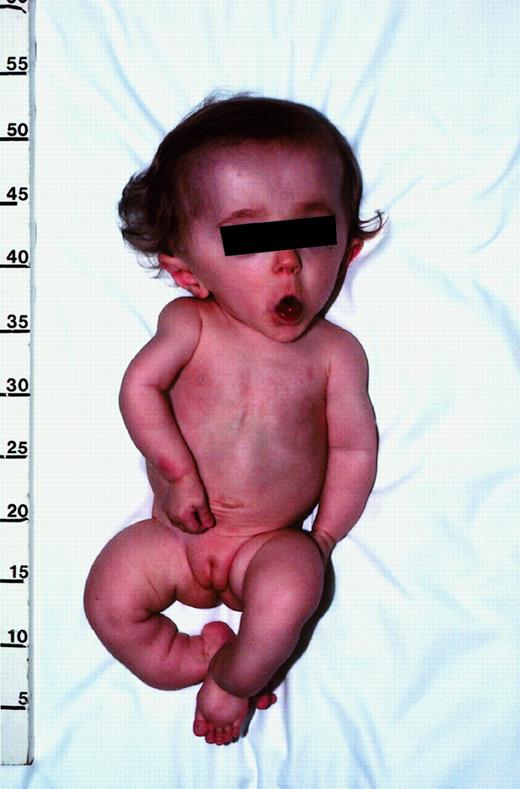

Five children with OI were enrolled with informed parental consent in a pilot clinical trial that had been approved by the Institutional Review Board of St Jude Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, TN. Each patient had genetic and physical features typical of progressive deforming (type III) OI9-11 (Figure1). Two cases were excluded from the present analysis because we could not document donor osteoblast engraftment after treatment, rendering the mesenchymal engraftment status unknown. None of the patients received growth hormone before or during this study.

Photograph of patient no. 1 illustrating the typical features of progressive deforming (type III) OI.

This 13-month-old girl has relative macrocephaly, triangular facies, and blue sclera (blocked by screen). Although not evident here, she also has malformed teeth, which is indicative of dentinogenesis imperfecta. Her extremities are shorter than normal, with mild curvature of the arms and marked angulation deformities of the lower legs. On roentgenograms (not shown), the bones appeared thin and osteopenic, with prominent curvatures not evident from physical examination. The humerus had an angulation of about 30°, and one of the lower legs was angulated approximately 100°. There was also evidence of old fractures. The thoracic cage was small, and the ribs were malformed. Published with parental consent.

Photograph of patient no. 1 illustrating the typical features of progressive deforming (type III) OI.

This 13-month-old girl has relative macrocephaly, triangular facies, and blue sclera (blocked by screen). Although not evident here, she also has malformed teeth, which is indicative of dentinogenesis imperfecta. Her extremities are shorter than normal, with mild curvature of the arms and marked angulation deformities of the lower legs. On roentgenograms (not shown), the bones appeared thin and osteopenic, with prominent curvatures not evident from physical examination. The humerus had an angulation of about 30°, and one of the lower legs was angulated approximately 100°. There was also evidence of old fractures. The thoracic cage was small, and the ribs were malformed. Published with parental consent.

Patient no. 1 was a 13-month-old girl with a weight of 5.04 kg and a height of 54.5 cm at the time of transplantation. Patient no. 2 was a 13-month-old boy whose weight and height were 5.04 kg and 56.0 cm, respectively. Engraftment data and other details are given in Horwitz et al.20 Patient no. 3, a 17-month-old boy, weighed 6.7 kg (median weight for age 4 months), was 54.0-cm long (median length for age 1 month), and had an occipital frontal head circumference of 47.0 cm, which ranked in the 20th percentile for the patient's age. The TBBMC was 84.8 g (55% of predicted mean for weight-matched healthy children). DNA analysis revealed a guanine-to-adenine mutation in exon 24 of the COL1A2 gene, resulting in a glycine-to-serine substitution at residue 370 of proα2(I). Patient no. 3 received 16 doses of 1 mg/kg busulfan and 4 doses of 50 mg/kg cyclophosphamide as the conditioning regimen. Chimerism was less than complete after engraftment, but it improved to 100% donor cells after rapid reduction of the cyclosporine.

Osteoblast engraftment at 3 months after treatment was 1.2%. Stage 3 graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) of the skin developed on day 19, resolving without sequelae during therapy with prednisone and an anti–T-cell monoclonal antibody (Abx-Cbl-1; Abgenix Corp, Fremont, CA).

Controls

The control patients were 2 children with clinical features and genetic mutations consistent with severe OI.9 10 Control no. 1 was a 13-month-old boy weighing 7.3 kg (median weight for 5 months of age) and measuring 63-cm long (median length for 4 months). DNA analysis revealed an adenine-to-cytosine mutation 4 base pair (bp) downstream of exon 41 in the COL1A1 gene. Control no. 2 was a 13-month-old girl weighing 7.1 kg (median weight for 6 months) and measuring 66-cm long (median length for 6 months). DNA analysis revealed a 9–bp deletion in exon 17 of the COL1A1gene. Both children could sit with support, but they could not creep, crawl, or stand. They did not receive specific therapy, including growth hormone therapy, during the observation period covered by this analysis. The clinical features of the 3 patients and 2 controls are summarized in Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients and regimens

| Subject . | Age, m . | Sex . | Weight, kg . | Length, cm . | Conditioning regimen . | Total nucleated cell dose, × 108 cells per kg . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient no. | ||||||

| 1 | 13 | F | 5.0 | 54.5 | busulfan (1 mg/kg × 16 doses) | 5.7 |

| Ara C (2 g/m2 × 6 doses) | ||||||

| cyclo (45 mg/kg × 2 doses) | ||||||

| 2 | 13 | M | 5.0 | 56.0 | busulfan (40 mg/m2 × 8 doses) | 6.2 |

| cyclo (60 mg/kg × 2 doses) | ||||||

| TBI (180 cGy × 5 doses) | ||||||

| 3 | 17 | M | 6.7 | 54.0 | busulfan (1 mg/kg × 16 doses) | 5.5 |

| cyclo (50 mg/kg × 4 doses) | ||||||

| Control no. | ||||||

| 1 | 13 | M | 7.3 | 63.0 | ||

| 2 | 13 | F | 7.1 | 66.0 |

| Subject . | Age, m . | Sex . | Weight, kg . | Length, cm . | Conditioning regimen . | Total nucleated cell dose, × 108 cells per kg . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient no. | ||||||

| 1 | 13 | F | 5.0 | 54.5 | busulfan (1 mg/kg × 16 doses) | 5.7 |

| Ara C (2 g/m2 × 6 doses) | ||||||

| cyclo (45 mg/kg × 2 doses) | ||||||

| 2 | 13 | M | 5.0 | 56.0 | busulfan (40 mg/m2 × 8 doses) | 6.2 |

| cyclo (60 mg/kg × 2 doses) | ||||||

| TBI (180 cGy × 5 doses) | ||||||

| 3 | 17 | M | 6.7 | 54.0 | busulfan (1 mg/kg × 16 doses) | 5.5 |

| cyclo (50 mg/kg × 4 doses) | ||||||

| Control no. | ||||||

| 1 | 13 | M | 7.3 | 63.0 | ||

| 2 | 13 | F | 7.1 | 66.0 |

Total nucleated cell dose includes cells from unmanipulated bone marrow (per kg recipient weight) that were transplanted. All patients received cyclosporine as prophylaxis against GVHD. Data for controls are presented at 13 months of age to facilitate comparison with patients. Ara C indicates cytarabine; cyclo, cyclophosphamide; and TBI, total body irradiation (added because sibling donor was a HLA-DRB1 mismatch).

Methods

The clinical and laboratory procedures are described in detail elsewhere.20 Briefly, patient length was determined by direct measurement, in triplicate, from crown to heel by the same observer (P.L.G.). Growth velocity is defined as the difference between the first and last measurement of each interval, reported as a percentage of the median growth velocity for age- and sex-matched healthy children.21 Total body bone mineral content was determined by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry performed on a whole-body scanner (Hologic QDR 2000 Densitometer; Hologic, Waltham, MA) with a pediatric platform and body size–specific computer software.22

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the quantitative outcome data was not possible due to the small numbers of patients and controls.

Results

Growth

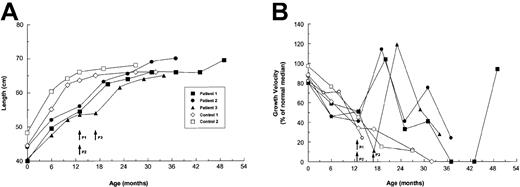

Before treatment, the 3 patients and their controls had similar growth rates (Figure 2), which were typical of children with untreated type III OI.23,24 From 6-13 months of age, the patients grew a median of 5.0 cm, and the controls grew a median of 7.2 cm. The growth of children with severe OI generally reaches a plateau at about 12 months of age.23This restriction was evident in our control patients, who grew only a median 1.25 cm (range, 1.0-1.5 cm), or 17% of the predicted median for age-matched healthy children,21 during the ensuing 6 months. By contrast, each of the patients showed accelerated growth during the first 6 months after treatment, with a median growth of 7.5 cm (range, 6.5-8.0 cm). The patients' growth rates early after treatment were similar to those predicted for age-matched healthy children (Figure 2B). With extended follow-up, the growth rates slowed but still exceeded the control rates; patient no. 1 had a growth rebound 30 months after treatment (42 months of age).

Growth profiles of OI patients and controls from birth to the most recent assessment.

(A) Absolute growth in cm. (B) Growth velocity is defined as the difference between the first and last measurement of each interval, reported as a percentage of the median growth velocity for age- and sex-matched healthy children.21 Controls were children with OI who did not receive specific therapy during the observation period. Each symbol represents a crown-to-heel measurement. Arrows indicate the times of transplantation for patients (P).

Growth profiles of OI patients and controls from birth to the most recent assessment.

(A) Absolute growth in cm. (B) Growth velocity is defined as the difference between the first and last measurement of each interval, reported as a percentage of the median growth velocity for age- and sex-matched healthy children.21 Controls were children with OI who did not receive specific therapy during the observation period. Each symbol represents a crown-to-heel measurement. Arrows indicate the times of transplantation for patients (P).

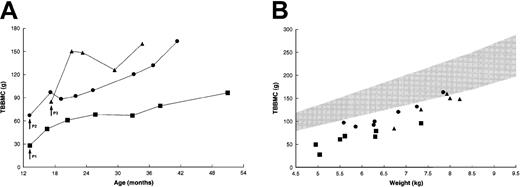

Bone mineral content

Each of the patients was osteopenic at the time of treatment, with a TBBMC of 25% to 60% of predicted mean for weight-matched healthy children (Figure 3A).22During the next 3 months, the TBBMC increased by 21.6 to 65.3 g or 45% to 77% above baseline values. Patient no. 1 had a further increase in TBBMC, to 95.8 g, while patient no. 2 attained a final TBBMC of 161.5 g. Patient no. 3, who had the most striking initial increase, showed additional improvement following a sharp decline. The rate of gain in TBBMC among these patients slightly exceeded that for weight-matched healthy children (Figure 3B); thus, the last few measurements approached the lower limit of the normal range.

Changes in TBBMC after BMT.

(A) Absolute measurements by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. Patient no. 2 had progressive increases in TBBMC after the placement of intramedullary rods at 29 months of age. (B) TBBMC as a function of body weight. The shaded area represents the normal range (mean ± 2 SD) of measurements for weight-matched healthy children.22Data for control patients were not available. Arrows indicate the times of transplantation. Symbols correspond to those in Figure 2.

Changes in TBBMC after BMT.

(A) Absolute measurements by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. Patient no. 2 had progressive increases in TBBMC after the placement of intramedullary rods at 29 months of age. (B) TBBMC as a function of body weight. The shaded area represents the normal range (mean ± 2 SD) of measurements for weight-matched healthy children.22Data for control patients were not available. Arrows indicate the times of transplantation. Symbols correspond to those in Figure 2.

Fractures

The rate of radiographically documented fractures decreased from a median of 10 (range, 4-18) during the 6 months immediately preceding treatment to a median of 2 (range, 0-3) during the next 6 months. The fracture rate remained at a median of 2, (range, 1-2), from month 7 to month 12 after treatment. A median of 2 fractures (range, 1-10) per year was observed thereafter. By contrast, the rate of fractures among control patients, 3-5 per year (median, 4), did not change appreciably during the observation period.

Toxicity

Because the toxicity associated with BMT is largely due to the conditioning regimen and the immunocompetent T cells in the graft, all subjects who underwent transplantation were considered eligible for the evaluation of toxicity. Patient no. 2 developed sepsis, transient pulmonary insufficiency, and a bifrontal hygroma, while patient no. 3 developed acute GVHD. Each of these complications resolved uneventfully. None of the patients had other toxic episodes associated with BMT including chronic GVHD.

Discussion

The working hypothesis of our current BMT protocol for severe childhood OI is that whole marrow contains mesenchymal precursor cells that can engraft in the skeleton and generate osteoblasts capable of modifying abnormal bone structure. We previously showed that such treatment produces histologic changes in trabecular bone which are indicative of new, dense bone formation.20 Less clear was the clinical significance of these findings. Although the linear growth rate, TBBMC, and fracture rate appeared to improve in some patients, the lack of reliable controls and long-term follow-up evaluation prevented us from delineating these responses over time.

Here we report growth acceleration for 3 children with severe OI during the first 6 months following transplantation, in contrast to retarded growth for age-matched controls. With longer follow-up, the growth rates of the treated patients slowed, but remained generally higher than control rates. Glorieux et al12 studied the growth rates of 10 prepubertal children treated with pamidronate, a bisphosphonate compound that inhibits bone resorption. Although the patients' mean pretreatment growth rate was maintained, there was no evidence of growth stimulation. We also observed rapid increases in TBBMC within the first 3 months after treatment, followed by additional gains that extended to the final assessment. Glorieux et al12 reported improvement in the bone mineral density of the lumbar spine in 4 prepubertal patients treated with pamidronate for 2 or more years. Plotkin et al14 reported improvement in the same measure of bone mineralization in 9 children less than 3 years old. However, comparison of these data with ours is difficult, as regional measurements of bone mineral density do not necessarily reflect mineralization over the entire skeleton.25Moreover, recent reports indicate that the increased bone mineralization seen with bisphosphonate treatment may not improve bone strength.26 Bisphosphonates, which inhibit bone remodeling, may also adversely affect other biomechanical properties of bone,27 thereby raising concerns regarding their long-term efficacy in the treatment of severe OI.

Gains in TBBMC are substantially influenced by increases in body size.19 Hence, improvements in bone mineral content measurements may simply reflect the consequences of growth. This appears unlikely in our patients because the TBBMC began to increase rapidly within the first 3 months after treatment, even though more than 70% of the linear growth during the first 6 months occurred in the latter half of this interval. The patients also showed late increases in TBBMC during times when growth rates were slowing. Finally, the patients' rates of TBBMC gain were similar to, or even slightly exceeded, those among weight-matched healthy children (Figure3B). Although serial control measurements are not available for comparison, this observation suggests a beneficial effect from BMT. Because OI is a syndrome of osteoporosis, bone mineralization would not be expected to parallel that in weight-matched healthy children. Consistent with this prediction, Plotkin et al14reported that the bone mineral density of the lumbar spine decreased during the second year of life in 6 children with severe OI.

We suggest that the positive effects of BMT in this study were due to the integration of competent donor cells of the osteoblastic lineage into developing bone. Whether the graft included osteogenic precursors with long-term repopulating ability or only committed osteoblasts with relatively short life spans is unclear. Additional bone biopsies to resolve this issue were precluded by ethical considerations. Conceivably, the slowing of growth rates with longer follow-up could indicate a temporary benefit due to short-lived osteoblast engraftment. However, gains in TBBMC were observed during the entire study period, and patient no. 1 showed a growth spurt at 43 months of age (2.5 years after treatment), which is consistent with the growth profile of type IV OI patients.23 Taken together, these findings suggest durable engraftment of osteogenic donor cells, which potentially could convert a severe clinical phenotype to a less severe one.

Conceivably, the bone marrow conditioning regimen removed bone resorbing osteoclasts, leading to marked increases in TBBMC through reduced bone resorption and potentially to increases in growth. Several observations argue against this interpretation. BMT usually reduces rather than stimulates normal bone mineralization.28-30Also, osteolytic lesions in myeloma patients do not respond to high does of alkylating agents, but the lesions can be successfully managed with bisphosphonate therapy,31 which indicates that the alkylating agents received by our patients probably did not significantly inhibit osteoclast function. Finally, there is no evidence that bone marrow conditioning regimens can stimulate linear growth. In several studies this procedure inhibited the growth and development of children.32-35

We conclude from this pilot study that improvements in bone structure and function following allogeneic BMT in children with severe OI20 can lead to objective clinical benefits. The durability of the observed responses remains in question and may well depend on whether engraftment included long-lived osteoblast progenitors with self-renewal potential.17 This uncertainty underscores the need for more complete knowledge of mesenchymal cell biology and for methods to ensure that sufficient numbers of osteogenic cells engraft in patients and produce competent osteoblasts. With these refinements, BMT may become a useful addition to the strategies of corrective surgery, physical therapy, and medical treatments now employed in the management of children with severe OI.

We gratefully acknowledge Maureen Kinnarney, Peggy Brown, Sharon Nooner, and Dr Jarmo Korkko for excellent assistance. We also thank John Gilbert for his critical editorial review and Jean Johnson for assistance in preparation of the manuscript.

Supported by the Clinical Investigator Development Award K08 HL 03266 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), Bethesda, MD; the Clinical Scientist Award T99102 from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, New York, NY; the Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA 21765 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Bethesda, MD; the Hartwell Foundation; the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Edwin M. Horwitz, St Jude Children's Research Hospital, 332 North Lauderdale, Memphis, TN 38105; e-mail:edwin.horwitz@stjude.org.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal