R115777 is a nonpeptidomimetic enzyme-specific inhibitor of farnesyl protein transferase (FT) that was developed as a potential inhibitor of Ras protein signaling, with antitumor activity in preclinical models. This study was a phase 1 trial of orally administered R115777 in 35 adults with poor-risk acute leukemias. Cohorts of patients received R115777 at doses ranging from 100 mg twice daily (bid) to 1200 mg bid for up to 21 days. Dose-limiting toxicity occurred at 1200 mg bid, with central neurotoxicity evidenced by ataxia, confusion, and dysarthria. Non–dose-limiting toxicities included reversible nausea, renal insufficiency, polydipsia, paresthesias, and myelosuppression. R115777 inhibited FT activity at 300 mg bid and farnesylation of FT substrates lamin A and HDJ-2 at 600 mg bid. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), an effector enzyme of Ras-mediated signaling, was detected in its phosphorylated (activated) form in 8 (36.4%) of 22 pretreatment marrows and became undetectable in 4 of those 8 after one cycle of treatment. Pharmacokinetics revealed a linear relationship between dose and maximum plasma concentration or area under the curve over 12 hours at all dose levels. Weekly marrow samples demonstrated that R115777 accumulated in bone marrow in a dose-dependent fashion, with large increases in marrow drug levels beginning at 600 mg bid and with sustained levels throughout drug administration. Clinical responses occurred in 10 (29%) of the 34 evaluable patients, including 2 complete remissions. Genomic analyses failed to detect N-ras gene mutations in any of the 35 leukemias. The results of this first clinical trial of a signal transduction inhibitor in patients with acute leukemias suggest that inhibitors of FT may have important clinical antileukemic activity.

Introduction

Adult acute leukemias remain formidable therapeutic challenge. Only 70% of adults with newly diagnosed acute myelogenous leukemias (AMLs) achieve complete remission (CR) after cytotoxic induction chemotherapy. Although these CRs may be prolonged in 35% to 40% of younger adults (age < 60),1-5 the remainder have a relapse and die. Certain subgroups, including older adults,3,5,6 patients with AMLs linked to environmental or occupational exposures (including therapy-induced AMLs), and patients with previous myelodysplasia (MDS) or other antecedent hematologic disorders,7,8 have extremely poor outcomes, with CR rates of 40% or less, CR durations less than 12 months, and cure rates less than 10% to 15%.3,5,6 The overall outlook for adult acute lymphoblastic leukemias (ALLs) is similar,9-11 with a particularly poor prognosis in Philadelphia chromosome (Ph+) disease.9 12 Thus, new approaches are needed to improve the outcome for adults with refractory leukemias.

Improved understanding of signal transduction pathways has resulted in identification of a panoply of potential therapeutic targets.13-16 Among these are the membrane-associated G proteins encoded by the ras family of proto-oncogenes. Ras proteins are activated downstream of protein tyrosine kinases (PTKs, eg, growth factor receptors) and, in turn, trigger a cascade of phosphorylation events through sequential activation of Raf, MEK-1, and ERKs (extracellular signal-related kinases). These events are critical to survival of hematopoietic cells.16-19

The Ras proteins are synthesized as cytosolic precursors that must attach to the cell membrane to transmit signals. Membrane attachment depends on the addition of a 15-carbon farnesyl group to Ras, a reaction that is catalyzed by the enzyme farnesyltransferase (FT).20-22 FT inhibitors (FTIs) were developed on the premise that FT inhibition would prevent Ras processing and, therefore, transduction of proliferative signals.22-24 Subsequent studies, however, have suggested that the cytotoxic actions of FTIs might also involve other farnesylated polypeptides, including RhoB25,26 and components of the phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase (PI3K)/AKT-2 pathway.27

Mutations and abnormal expression of ras genes, especially N-ras, are detected in roughly 10% to 15% of MDS (especially those transforming to AML)28,29 and in 15% to 25% of AMLs studied to date.30-33 In addition, the coupling of Ras proteins to PTKs raises the possibility that PTK-driven malignancies might be susceptible to FTIs.34 35

R115777, a potent and selective nonpeptidomimetic competitive FT inhibitor,22 decreases proliferation of T24H-ras–transfected NIH 3T3 cells as well asK-ras–transformed CAPAN-2 pancreatic cancer cells and several human colon cancer lines in vitro.22,36Phase 1 trials of R115777 in adults with solid tumors37demonstrated oral bioavailability, with a linear relationship between dose and maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) or area under the concentration curve at over 12 hours (AUC0-12h) at doses up to 500 mg twice daily (bid). Dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) on various schedules included reversible myelosuppression, neuropathy, fatigue, and serum creatinine elevations.36 37

To test the potential molecular, biologic, and clinical effects of R115777 in adults with refractory and relapsed acute leukemias, we conducted a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Results of this trial provide the first evidence for successful inhibition of FT in neoplastic cells in vivo as well as promising antileukemic activity.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patient eligibility and selection

Adults, aged 18 years or older, with pathologically confirmed acute leukemia that was unlikely to be cured by existing therapies, including AML or ALL resistant to or relapsed after 2 prior induction regimens (or fewer); newly diagnosed AML in adults over age 60 with poor-risk features (antecedent hematologic disorder, adverse cytogenetics); AML arising from MDS or secondary AML; and chronic myelogenous leuekmia in blast crisis (CML-BC) were eligible for study entry provided they met the following criteria: Zubrod performance status 0 to 2; normal bilirubin; hepatic enzymes twice normal or less; serum creatinine 1.5 times normal or less; and left ventricular ejection fraction 45% or higher. Complete recovery from toxicities of previous treatment, an interval of 3 weeks or more from previous chemotherapy, and an interval of 1 week or more from any growth factor therapy was required before beginning R115777.

Patients were ineligible if they had a peripheral blast count of 50 000/μL or higher; disseminated intravascular coagulation; active central nervous system leukemia; prior allogeneic stem cell transplantation; prior radiation up to more than 25% of bone marrow; concomitant radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or immunotherapy; coexisting medical or psychiatric conditions that could interfere with study procedures; or known allergy to imidazoles. Pregnant or lactating women were ineligible. All patients provided written informed consent according to respective University of Maryland, Baltimore institutional review board guidelines.

Complete history and physical examination were performed within 3 days of study entry. Because cataract development was noted in Wistar rats with prolonged exposure at high doses of R115777,22 28 all patients underwent visual acuity testing at baseline and at the end of R115777 administration. The following laboratory parameters were obtained at 3 days or less before entry: complete blood count with differential; electrolyte panel, magnesium, calcium, phosphate, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, glucose, uric acid, amylase, cholesterol, total protein and albumin, hepatic transaminases, bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase; coagulation profile (prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, fibrinogen, fibrin degradation products); urinalysis; bone marrow aspirate (biopsy when indicated) with histochemical, cytogenetic and immunophenotypic analysis; chest x-ray; electrocardiogram; bacterial, fungal, and viral cultures of throat, stool, and urine; and, for women of childbearing potential, a pregnancy test. Additional studies (lumbar puncture with cerebrospinal fluid cytospin, computed tomography scans, gallium scans, multiple gated acquisition, or echocardiogram) were performed when clinically indicated.

Treatment schema

Patients received R115777 capsules by mouth every 12 hours with food for 21 days unless otherwise indicated. The drug was discontinued after 7 days if there was less than a 25% decrease in circulating blasts or if severe nausea and vomiting occurred despite adequate antiemetic treatment (≥ 5 episodes in 24 hours). Drug was discontinued at any time for other grade 3 or higher nonhematologic side effects. Using a modified dose-escalation schema, the first 6 patients enrolled received 100 mg bid. Dose escalation could proceed if no more than one of 3 patients experienced DLT, defined as either grade 3 or higher nonhematologic toxicity or grade 4 bone marrow aplasia with myelosuppression lasting 40 days or more. Following completion of the first dose level, cohorts of 4 to 6 patients were treated with the following doses: 300 mg bid, 600 mg bid, 900 mg bid, and 1200 mg bid. The occurrence of any DLT in 33% of a patient cohort defined the maximal tolerated dose (MTD). Once MTD was reached, an expanded cohort of patients was treated at the dose level below MTD and observed for DLT. Patients with evidence of response or without disease progression after the first 21 days were eligible to receive up to 3 more 21-day cycles of R115777, with a 7-day drug-free hiatus between each cycle.

Definitions of response

To assess response to therapy, a bone marrow aspiration was performed weekly during the first 21-day cycle and at the end of each subsequent cycle or at any time that leukemia regrowth was suspected. Hematologic recovery was defined as an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of at least 500/μL and a transfusion-independent platelet count of 50 000/μL. CR required a normal bone marrow aspirate with absence of identifiable leukemia, ANC of 1000/μL or higher, platelet count of 100 000/μL or higher, and absence of blasts in peripheral blood.38 Clearance of cytogenetic abnormalities was not required for CR, but was noted and described separately. Partial response (PR) was defined as the presence of trilineage hematopoiesis in the marrow with normalization of peripheral counts but with 5% to 25% blasts in the marrow.38 No response (NR) was defined as persistent leukemia in marrow or blood or both without significant decrease from pretreatment levels and without improvement in peripheral counts.

The ras gene mutations

Bone marrow cells obtained before treatment were analyzed for the presence of N-ras gene mutations using polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-amplified genomic DNA. Primers were designed to amplify 2 DNA fragments of approximately 100 base pairs each, one containing codons 12 and 13 and the other containing codon 61,28which were screened for mutations using single-strand conformational polymorphism (SSCP) and heteroduplex analysis. Mutations were identified by comparing banding patterns with specimens containing known N-ras mutations or by direct sequencing of the PCR product. Mutations in N-ras codons 12, 13, and 61 were also analyzed by a nested PCR method in which wild-type sequence is digested by restriction enzyme followed by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis. Samples were also analyzed for K-ras mutations as determined by restriction endonuclease-mediated selective PCR (REMS-PCR)39 and gel analysis.

Measures of intracellular FT activity

To determine whether leukemic cell FT activity is inhibited in vivo by R115777, we examined serial marrow samples obtained at weekly intervals for R115777-related changes in FT activity.

FT enzyme inhibition.

Bone marrow cells were isolated by centrifugation in Accuspin-Histopaque tubes, depleted of red blood cells by distilled water lysis, pelleted, and frozen for subsequent analysis. All samples from each individual were run simultaneously. Frozen cell pellets were processed by adding 0.2 mL sonication buffer (20 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.5, plus 1 mM dithiothreitol and 20 μM ZnCl2, supplemented with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and Calbiochem Protease Inhibitor Cocktail, San Diego, CA), sonicated for 20 seconds, and centrifuged at 300 000g for 20 minutes in a Beckman microultracentrifuge (Palo Alto, CA). Aliquots of supernate were assayed for protein41 and adjusted to 0.5 mg/mL (10 μg/20 μL). FT activity was measured using a scintillation proximity assay (SPA) kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotechnology, Piscataway, NJ). In brief, triplicate 20 μL samples were incubated for 60 minutes at 37°C with the lamin B peptide substrate (Biotin-YRASNRSCAIM) and [1-3H(n)]farnesyl-pyrophosphate.40 The resulting farnseylated peptide was recovered using streptavidin-conjugated scintillant-containing beads and quantitated as described by the supplier. Geranylgeranyltransferase (GGT) type 1 assays were performed using an SPA modification that involved incubating biotin-YRASNRSCAIL peptide substrate with [1-3H(n)] geranylgeranylphosphate for 120 minutes at 37°C.40

Farnesylation of lamin A and HDJ-2.

The intranuclear intermediate filament protein lamin A42and the chaperone protein HDJ-243 are polypeptides that undergo farnesylation-dependent processing and, therefore, undergo mobility shifts when FT is inhibited.44,45 Thus, serial measurement of farnesylated and unfarnesylated lamin A and HDJ-2 in leukemic bone marrow cells before and during R115777 administration might serve as useful markers of FT inhibition.46,47 To assess the feasibility of this approach, heparinized bone marrow aspirates were cooled to 4°C and shipped by overnight courier to one of the authors (S.H.K.). Bone marrow mononuclear cells were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque sedimentation and washed with buffer A (RPMI 1640 medium containing 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, at 4°C). Aliquots were removed for cell counts and preparation of Wright-stained cytospins for morphologic examination. Cell lysates were then prepared as previously described in detail.46 Aliquots containing total cellular protein from 5 × 105 marrow mononuclear cells were subjected to electrophoresis on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–polyacrylamide gels containing 8% (vol/vol) acrylamide, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed48,49 with immunologic agents that react to a polypeptide that is uniquely present in prelamin A,46,50monoclonal antibody against mature lamin A,51 anti–HDJ-2 or antihistone H1 using techniques previously described in detail.46 Log phase K562 human leukemia cells (American Tissue Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) incubated for 24 hours in RPMI 1640 medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin G, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM glutamine, and 0.1% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) or the indicated concentration of R115777 (added from a 1000 × stock in DMSO) served as negative and positive controls, respectively.

Phosphorylation of signaling intermediates ERK1/ERK2.

To assess ERK1/ERK2 phosphorylation, bone marrow aspirates were subjected to Ficoll-Hypaque gradient sedimentation followed by extraction with Tris-buffered salt solution containing nonionic detergent and protease inhibitors. After SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, extracts were transferred to Immobilin-P membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA), probed with anti-ERK1/ERK2 antibody (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY), and visualized by enhanced chemoluminescence (Amersham). Phosphorylated forms were identified by their slowed gel migration. Repeat probing with phosphotyrosine-specific antibody identified the presence or absence of tyrosine phosphorylation. Band intensity was quantitated by phosphorimage analysis using ImageQuant software.

Pharmacokinetics

Blood samples for pharmacokinetic studies were obtained immediately before administration of R115777 and at 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, and 12 hours thereafter on days 1, 8, 15, and 22; immediately prior to the morning dose of R115777 on days 3 through 5; and at 24, 36, 48, and 72 hours after the last dose if dosing was stopped on day 8, 15, or 22. At each time point, 6 mL heparinized blood was transported on ice and centrifuged within 2 hours (1000g for 10 minutes). Separated plasma was immediately frozen on dry ice, stored at −70°C, and shipped in batches to Janssen Research Foundation (JRF, Beerse, Belgium), where levels were determined using a validated high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) assay.37Plasma concentration-time profiles of R115777 were analyzed by standard noncompartmental methods using the software package WinNonlin (Pharsight, Mountain View, CA). The following pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated: maximum plasma concentration (Cmax), time to maximum plasma concentration (tmax), trough plasma concentration (C0h), and area under the plasma concentration versus time curve over a 12-hour dosing interval calculated by trapezoidal summation (AUC12h). Because the pharmacokinetic profile of R115777 is biphasic,37 initial (T1/2 dominant) and terminal half-lives (T1/2 terminal) were estimated by linear regression of the log-transformed concentration versus time data. The accumulation ratio was calculated by dividing the AUC12h determined on day 8 or 15 by that of day 1.

To assess R115777 levels in the target organ, bone marrow aspirates were obtained concomitantly with morning predose plasma samples on days 1, 8, 15, and 22 (when feasible). Cells were sedimented from heparinized marrow, frozen at −70°C, and extracted prior to HPLC analysis at JRF.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 35 patients with leukemia were entered into this phase 1 study of R115777. One patient failed to take drug as instructed and was not evaluable. The remaining 34 patients were evaluable for toxicity or response to R115777. Their demographic and disease characteristics are detailed in Table 1. Median age was 65 (range 24-77), and 67.6% (23 of 34) were men. Twenty-five (74%) had AML (6 newly diagnosed, 9 relapsed, 10 refractory to induction or reinduction therapies). Cytogenetic analyses were evaluable in 21 and abnormal in 12 (57%), with chromosome 7 abnormalities detected in 4. Of 6 patients with ALL, 3 were Ph+; all 3 patients with CML-BC had cytogenetic aberrations (2 complex, 1 Ph−). None of the leukemic marrow populations from the 35 patients harbored detectable N-rasmutations despite the reported incidence of N-ras mutations in AMLs and MDS.28-33

Patient characteristics

| R115777 dose (mg) . | Patient no. . | Age/Sex . | Diagnosis . | Stage of disease . | Cytogenetics . | Poor-risk markers . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 1 | 59 M | AML, M5 | Relapse 2 | 46 XY | CD34 |

| 2 | 51 M | AML, M1 | Relapse 2 | 46 XY | CD34, 7 | |

| 3 | 68 F | CML-BC | Refractory | 46 XY, Ph- | CD34 | |

| 4 | 75 M | AML, M7 | Refractory | 46 XY | CD34 | |

| 5 | 47 M | AML, M1 | Relapse | 46 XY | CD34 | |

| 6 | 72 M | AML, M1 | New | 46 XY | None | |

| 300 | 7 | 69 M | CML-BC | Refractory | t (9; 22;16) | CD34, 7, 20 |

| 8 | 52 F | ALL, L2 | Refractory | t (9; 22) | CD13 | |

| 9 | 71 M | ALL, L2 | Relapse 1 | No growth | CD13 | |

| 10 | 75 M | AML, M4 | New | 46 XY | CD34 | |

| 11 | 67 M | AML, M7 | New | 47 XY, +8 | CD34 | |

| 600 | 12 | 55 M | AML, M1 (2°) | Relapse | 46 XY, 20q- | CD34, 7, 2 |

| 13 | 65 M | AML, M4 | Refractory | 46 XY | None | |

| 14 | 24 F | ALL, L2 | Relapse 1 | 46 XX | None | |

| 15 | 61 M | AML, M0 | Refractory | t (4;12) | CD34, 7 | |

| 16 | 73 M | AML, M2 | Relapse | inv (18) | CD34 | |

| 17 | 54 F | AML, M4 | Refractory | 47 XX, +15 | CD34 | |

| 18 | 72 F | AML, M1 | Refractory | T (2;7), t (x;1) | CD34 | |

| 19 | 73 M | AML, M1 | New | Not done | Not done | |

| 900 | 20 | 73 M | AML, M1 | Relapse 2 | t (7;14) | CD34, 7 |

| 21 | 60 M | ALL, L2 | Refractory | t (9; 22) | CD33 | |

| 22 | 42 M | AML, M5 | Refractory | No growth | CD34 | |

| 23 | 38 F | CML, BC | Refractory | t (9; 22) | Not done | |

| 24 | 69 M | AML, M2 | New | 46 XY | CD34, 7 | |

| 25 | 60 F | ALL, L2 | New | t (9; 22) | None | |

| 26 | 39 M | AML, M5 | Relapse 1 | inv (11) | None | |

| 27 | 26 F | AML, M4 | Refractory | 45 XX, −7 | CD34, 7, 20 | |

| 28 | 75 F | AML, M0 | Refractory | No growth | CD34 | |

| 29 | 75 M | AML, M0 | Refractory | 46 XY | CD34 | |

| 30 | 77 M | AML, M1 | Refractory | −7q, iso (17) | CD34 | |

| 1200 | 31 | 24 F | AML, M4 | Relapse 2 | 47 XX, +8 | CD34, 7 |

| Subpop t (8; 11) | ||||||

| 32 | 72 M | AML, M4 | Relapse 1 | −1q, der (2) | None | |

| t (p21; ?) | ||||||

| 33 | 59 M | AML, M0 | Relapse 2 | 46 XY | CD34 | |

| 34 | 22 F | ALL, L2 | Relapse 1 | 46 X Y | None |

| R115777 dose (mg) . | Patient no. . | Age/Sex . | Diagnosis . | Stage of disease . | Cytogenetics . | Poor-risk markers . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 1 | 59 M | AML, M5 | Relapse 2 | 46 XY | CD34 |

| 2 | 51 M | AML, M1 | Relapse 2 | 46 XY | CD34, 7 | |

| 3 | 68 F | CML-BC | Refractory | 46 XY, Ph- | CD34 | |

| 4 | 75 M | AML, M7 | Refractory | 46 XY | CD34 | |

| 5 | 47 M | AML, M1 | Relapse | 46 XY | CD34 | |

| 6 | 72 M | AML, M1 | New | 46 XY | None | |

| 300 | 7 | 69 M | CML-BC | Refractory | t (9; 22;16) | CD34, 7, 20 |

| 8 | 52 F | ALL, L2 | Refractory | t (9; 22) | CD13 | |

| 9 | 71 M | ALL, L2 | Relapse 1 | No growth | CD13 | |

| 10 | 75 M | AML, M4 | New | 46 XY | CD34 | |

| 11 | 67 M | AML, M7 | New | 47 XY, +8 | CD34 | |

| 600 | 12 | 55 M | AML, M1 (2°) | Relapse | 46 XY, 20q- | CD34, 7, 2 |

| 13 | 65 M | AML, M4 | Refractory | 46 XY | None | |

| 14 | 24 F | ALL, L2 | Relapse 1 | 46 XX | None | |

| 15 | 61 M | AML, M0 | Refractory | t (4;12) | CD34, 7 | |

| 16 | 73 M | AML, M2 | Relapse | inv (18) | CD34 | |

| 17 | 54 F | AML, M4 | Refractory | 47 XX, +15 | CD34 | |

| 18 | 72 F | AML, M1 | Refractory | T (2;7), t (x;1) | CD34 | |

| 19 | 73 M | AML, M1 | New | Not done | Not done | |

| 900 | 20 | 73 M | AML, M1 | Relapse 2 | t (7;14) | CD34, 7 |

| 21 | 60 M | ALL, L2 | Refractory | t (9; 22) | CD33 | |

| 22 | 42 M | AML, M5 | Refractory | No growth | CD34 | |

| 23 | 38 F | CML, BC | Refractory | t (9; 22) | Not done | |

| 24 | 69 M | AML, M2 | New | 46 XY | CD34, 7 | |

| 25 | 60 F | ALL, L2 | New | t (9; 22) | None | |

| 26 | 39 M | AML, M5 | Relapse 1 | inv (11) | None | |

| 27 | 26 F | AML, M4 | Refractory | 45 XX, −7 | CD34, 7, 20 | |

| 28 | 75 F | AML, M0 | Refractory | No growth | CD34 | |

| 29 | 75 M | AML, M0 | Refractory | 46 XY | CD34 | |

| 30 | 77 M | AML, M1 | Refractory | −7q, iso (17) | CD34 | |

| 1200 | 31 | 24 F | AML, M4 | Relapse 2 | 47 XX, +8 | CD34, 7 |

| Subpop t (8; 11) | ||||||

| 32 | 72 M | AML, M4 | Relapse 1 | −1q, der (2) | None | |

| t (p21; ?) | ||||||

| 33 | 59 M | AML, M0 | Relapse 2 | 46 XY | CD34 | |

| 34 | 22 F | ALL, L2 | Relapse 1 | 46 X Y | None |

AML indicates acute myelogenous leukemia; CML-BC, chronic myelogenous leukemia in blast crisis; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Toxicities

As depicted in Table 2, no significant toxicity occurred in patients receiving the first 2 dose levels of R115777. At 600 mg bid, 3 of 8 (37.5%) developed one or more grade 1 to 2 toxicities without DLT. All were older than age 55, and 2 of 3 were older than age 65. One patient developed grade 1 fatigue that began by day 6 and resolved within 2 days of discontinuing the drug on day 21. Two patients developed transient serum creatinine elevations (≤ 2.7 mg/dL, onset days 8 and 23) that resolved without intervention within 72 hours.

Toxicities of R115777 related to dose level

| Dose (no. patients) . | 100 mg (6) . | 300 mg (5) . | 600 mg (8) . | 900 mg (11) . | 1200 mg (4) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | 2 (grade 1) | 1 (grade 1) | 2 (grade 1-2) | 2 (grade 2) | |

| Neurologic | |||||

| Visual | 1 (grade 1) | ||||

| Confusion | 2 (grade 1) | 2 (grade 3) | |||

| Ataxia | 1 (grade 3) | ||||

| Neuropathy | 2 (grade 1) | ||||

| Headache | 2 (grade 1) | ||||

| Renal/endocrine | |||||

| Polydipsia | 2 (grade 1) | 4 (grade 2) | |||

| Creatinine | 2 (grade 1) | 4 (grade 1-2) | |||

| Gastrointestinal | |||||

| Nausea | 1 (grade 1) | 2 (grade 1) | 3 (grade 2) | 3 (grade 2) | |

| Vomiting | 2 (grade 1) | 1 (grade 2) | |||

| Neutropenia < 500/mm3 | 2 | 5 | |||

| Fever/infection | 1 (grade 2) | 3 (grade 2) |

| Dose (no. patients) . | 100 mg (6) . | 300 mg (5) . | 600 mg (8) . | 900 mg (11) . | 1200 mg (4) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | 2 (grade 1) | 1 (grade 1) | 2 (grade 1-2) | 2 (grade 2) | |

| Neurologic | |||||

| Visual | 1 (grade 1) | ||||

| Confusion | 2 (grade 1) | 2 (grade 3) | |||

| Ataxia | 1 (grade 3) | ||||

| Neuropathy | 2 (grade 1) | ||||

| Headache | 2 (grade 1) | ||||

| Renal/endocrine | |||||

| Polydipsia | 2 (grade 1) | 4 (grade 2) | |||

| Creatinine | 2 (grade 1) | 4 (grade 1-2) | |||

| Gastrointestinal | |||||

| Nausea | 1 (grade 1) | 2 (grade 1) | 3 (grade 2) | 3 (grade 2) | |

| Vomiting | 2 (grade 1) | 1 (grade 2) | |||

| Neutropenia < 500/mm3 | 2 | 5 | |||

| Fever/infection | 1 (grade 2) | 3 (grade 2) |

At 900 mg bid, 6 (55%) of 11 patients experienced one or more grade 1 to 2 toxicities without formal DLT. Grade 1 to 2 polydipsia was detected in 4 (36%) of 11, began by day 3, abated within 5 to 10 days without specific intervention or drug discontinuation, and was not accompanied by hypernatremia, serum hyperosmolality, hyperglycemia, or intravascular collapse. One patient (aged 75) with polydipsia received concomitant antihypertensive treatment with an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor and developed creatinine elevation (baseline 1.3 mg/dL; peak 2.8 mg/dL) that improved within 2 days of discontinuing both R115777 and the ACE inhibitor. An additional 3 patients, all over age 70, developed transient, nonoliguric renal dysfunction of 5 days' duration or less. In addition, grade 1, nonprogressive fingertip paresthesias occurred on day 15 in one patient who had previous vincristine-related neuropathy and during the third cycle in one patient, who had no previous neuropathy. Although the toxicities encountered at 900 mg bid were reversible and were not dose limiting by strict definitions, their occurrences led to temporary (≤ 4 days) drug discontinuation in 3 patients (27%), all of whom were aged 70 or older.

When the dose of R115777 was increased to 1200 mg bid, 3 of 4 patients experienced grade 2 to 3 central neurotoxicities, including confusion, ataxia, and visual disturbances, that were dose limiting. These toxicities occurred by day 4 and necessitated immediate drug discontinuation. All symptoms resolved completely within 72 hours, but drug was not reinstituted. Thus, these patients did not complete the first course of therapy.

Drug-induced myelosuppression was not detected consistently at lower dose levels, but occurred frequently at 600 mg and 900 mg bid. At these dose levels, white blood cell (WBC) count nadir occurred on median day 16 (range, 3-22), with 2 of 8 patients at 600 mg bid and 5 of 8 patients at 900 mg bid reaching WBC nadir of 500/μL or less and an ANC of 100/μL or less.

Clinical outcome

Table 3 depicts the clinical outcome for the 34 evaluable patients. Measurable responses (CR and PR) occurred at all dose levels where drug administration was adequate for evaluation (100-900 mg bid), without a clear dose-response relationship. Overall response rate was 10 (29%) of 34, with 8 PRs (6 AML, 2 CML-BC) and 2 hematologic CRs (both AML). The response rate in AML was 32% (8 of 25), including 3 (50%) of 6 newly diagnosed, 3 (33%) of 9 relapsed, and 2 of 10 (20%) refractory. Both CRs occurred in patients with relapsed AML. The first (patient 2) entered CR in the course of receiving 3 cycles of R115777 100 mg bid, with the unmaintained CR duration being 7 months. At relapse, he was retreated into second CR with R115777, with the current duration of the second CR being 3+ months. The second (patient 16) entered CR following a 15-day course of R115777 600 mg bid; R115777 was discontinued because of profound neutropenia (ANC ≤ 100/μL). He remained in an unmaintained CR of 3 months' duration and did not undergo retreatment. The 2 patients with refractory AML who responded to R115777 exhibited deletions of all or part of chromosome 7, a genetic lesion known to be associated with aberrant ras expression or signaling, as exemplified by AML associated with defects in the neurofibomatosis (NF-1) gene.52 Two of the 3 patients with CML-BC (both Ph+ with complex cytogenetics) achieved PR, as evidenced by decreasing peripheral WBC counts, normalization of platelet count, and decreases in peripheral and bone marrow blasts. In contrast, none of the patients with ALL (including Ph+) responded and all demonstrated disease progression within 7 to 21 days of starting R115777.

Clinical outcome

| R115777 dose (mg) . | Patient no. . | Diagnosis . | % Marrow blasts . | Total no. courses . | Clinical outcome . | Survival from R115777 (mo) . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Rx . | End . | ||||||

| 100 | 1 | M5 | 95 | 95 | 1 | NR | 2.5 |

| 2 | M1 | 37 | 4 | 3 | CR 7 mo | 15 + | |

| 3 | CML-BC | 37 | 51 | 1 | NR | 6 | |

| 4 | M7 ? | NE | NE | 1 | NR | 5 | |

| 5 | M1 | 100 | 100 | 1 | NR | 1 | |

| 6 | M1 | 20 | 8 | 4 | PR | 14 + | |

| 300 | 7 | CML-BC | 39 | 7 | 3 | PR | 14.5 + |

| 8 | Ph + L2 | 80 | > 95 | 1 | NR | 5 | |

| 9 | L2 | 39 | 86 | 1 | NR | 1.5 | |

| 10 | M4 | 25 | 8 | 4 | PR | 7 | |

| 11 | M7 | 25 | 25 | 3 | NR | 5.5 | |

| 600 | 12 | M1 | 36 | 88 | 1 | NR | 0.5 |

| 13 | M4 | 83 | 64 | 1 | NR | 7 | |

| 14 | L2 | 90 | 80 | 1 | NR | 4 | |

| 15 | M0 | 75 | > 95 | 1 | NR | 3 | |

| 16 | M2 | 18 | 3 | 1 | CR 3 mo | 10 | |

| 17 | M4 | 75 | > 95 | 1 | NR | 11.5 | |

| 18 | M1 | 85 | 90 | 1 | NR | 4 | |

| 19 | M1 | 80 | 20 | 2 | PR | 12.5 + | |

| 900 | 20 | M1 | 60 | 25 | 3 | PR | 11 + |

| 21 | Ph + ALL | 70 | > 95 | 1 | NR | 5 | |

| 22 | M5 | > 95 | > 95 | 1 | NR | 2 | |

| 23 | CML-BC | 27 | 14 | 1 | PR | 11 + | |

| 24 | M2 | 25 | 25 | 1 | NR | 10.5 + | |

| 25 | Ph + ALL | 90 | 90 | 1 | NR | 0.5 | |

| 26 | M5 | 35 | 35 | 1 | NR | 7.5 | |

| 27 | M4 | 27 | 8.5 | 3 | PR | 9 | |

| 28 | M0 | NE | NE | 1 | NR | 1.5 | |

| 29 | M0 | 75 | 95 | 1 | NR | 2 | |

| 30 | M1 | 50 | 25 | PR | 5 | ||

| 1200 | 31 | M4 | 85 | — | 1 | Neurotoxicity | 3 |

| 32 | M4 | 60 | — | 1 | Neurotoxicity | 5 | |

| 33 | M0 | 90 | — | 1 | Neurotoxicity | 9.5 + | |

| 34 | L2 | 90 | 100 | 1 | NR | 3 | |

| R115777 dose (mg) . | Patient no. . | Diagnosis . | % Marrow blasts . | Total no. courses . | Clinical outcome . | Survival from R115777 (mo) . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Rx . | End . | ||||||

| 100 | 1 | M5 | 95 | 95 | 1 | NR | 2.5 |

| 2 | M1 | 37 | 4 | 3 | CR 7 mo | 15 + | |

| 3 | CML-BC | 37 | 51 | 1 | NR | 6 | |

| 4 | M7 ? | NE | NE | 1 | NR | 5 | |

| 5 | M1 | 100 | 100 | 1 | NR | 1 | |

| 6 | M1 | 20 | 8 | 4 | PR | 14 + | |

| 300 | 7 | CML-BC | 39 | 7 | 3 | PR | 14.5 + |

| 8 | Ph + L2 | 80 | > 95 | 1 | NR | 5 | |

| 9 | L2 | 39 | 86 | 1 | NR | 1.5 | |

| 10 | M4 | 25 | 8 | 4 | PR | 7 | |

| 11 | M7 | 25 | 25 | 3 | NR | 5.5 | |

| 600 | 12 | M1 | 36 | 88 | 1 | NR | 0.5 |

| 13 | M4 | 83 | 64 | 1 | NR | 7 | |

| 14 | L2 | 90 | 80 | 1 | NR | 4 | |

| 15 | M0 | 75 | > 95 | 1 | NR | 3 | |

| 16 | M2 | 18 | 3 | 1 | CR 3 mo | 10 | |

| 17 | M4 | 75 | > 95 | 1 | NR | 11.5 | |

| 18 | M1 | 85 | 90 | 1 | NR | 4 | |

| 19 | M1 | 80 | 20 | 2 | PR | 12.5 + | |

| 900 | 20 | M1 | 60 | 25 | 3 | PR | 11 + |

| 21 | Ph + ALL | 70 | > 95 | 1 | NR | 5 | |

| 22 | M5 | > 95 | > 95 | 1 | NR | 2 | |

| 23 | CML-BC | 27 | 14 | 1 | PR | 11 + | |

| 24 | M2 | 25 | 25 | 1 | NR | 10.5 + | |

| 25 | Ph + ALL | 90 | 90 | 1 | NR | 0.5 | |

| 26 | M5 | 35 | 35 | 1 | NR | 7.5 | |

| 27 | M4 | 27 | 8.5 | 3 | PR | 9 | |

| 28 | M0 | NE | NE | 1 | NR | 1.5 | |

| 29 | M0 | 75 | 95 | 1 | NR | 2 | |

| 30 | M1 | 50 | 25 | PR | 5 | ||

| 1200 | 31 | M4 | 85 | — | 1 | Neurotoxicity | 3 |

| 32 | M4 | 60 | — | 1 | Neurotoxicity | 5 | |

| 33 | M0 | 90 | — | 1 | Neurotoxicity | 9.5 + | |

| 34 | L2 | 90 | 100 | 1 | NR | 3 | |

For abbreviations, see Table 1.

As of 10/15/2000.

FT enzyme inhibition

The activity of FT was compared in paired marrow samples obtained before treatment on days 1 and 8 from 21 of the 30 evaluable patients who received 100 to 900 mg bid R115777. Samples were obtained immediately prior to the morning dose of R115777 and, therefore, reflected nadir levels of FT inhibition. Relative to pretreatment values, the enzyme was not inhibited consistently in patients receiving 100 mg bid. Beginning at 300 mg bid, however, R115777 suppressed marrow cell FT activity in all patients by a mean of 75% (range 50%-95%) (Figure 1) without clear dose-related increases. There was no apparent relationship between the depth of FT inhibition and clinical response.

Inhibition of FT enzyme activity in leukemic bone marrow samples by day 8 of R115777 administration.

Results are expressed as percent residual FT activity relative to day 0 (baseline) values. FT enzyme activity was not reproducibly inhibited in patients receiving R115777 100 mg bid. Beginning at 300 mg bid, however, R115777 suppressed FT activity relative to baseline values in all marrow samples studied.

Inhibition of FT enzyme activity in leukemic bone marrow samples by day 8 of R115777 administration.

Results are expressed as percent residual FT activity relative to day 0 (baseline) values. FT enzyme activity was not reproducibly inhibited in patients receiving R115777 100 mg bid. Beginning at 300 mg bid, however, R115777 suppressed FT activity relative to baseline values in all marrow samples studied.

Inhibtion of protein farnesylation

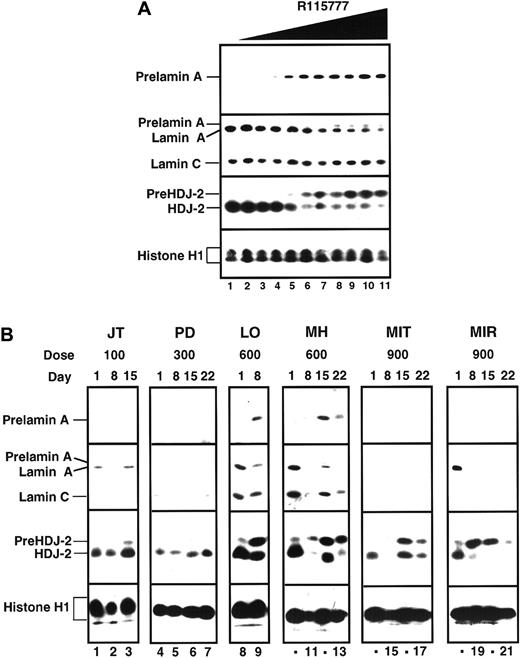

Data summarized in Figure 2and Table 4 indicate that R115777 blocked protein farnesylation in marrow cells obtained on days 8 through 21 as detected by accumulation of prelamin A and pre–HDJ-2. This effect was detected consistently in marrow cells obtained from patients treated with 600 mg R115777 bid, but not at lower doses. At 900 mg bid, an unexpected decrease in lamin A following R115777 made interpretation of prelamin A results problematic even though 7 of 10 pretreatment marrows studied expressed lamin A. On the other hand, pre–HDJ-2 appeared or increased in at least 6 (86%) of 7 patients by day 8 of R115777 treatment at this dose level.

Effect of R115777 on FT-dependent processing of prelamin A and HDJ-2 in K562 cells in vitro and in leukemic bone marrow samples in situ.

(A) Log-phase K562 cells were incubated for 24 hours with diluent (lane 1) or concentrations of R115777 ranging from 0.78 to 100 nM in 2-fold increments (lanes 2-11). At the completion of the incubation, samples were sedimented at 200g, washed once in serum-free RPMI 1640, and prepared for analysis as described in “Patients, materials, and methods.” R115777 causes a dose-dependent increase in signals for prelamin A and HDJ-2. (B) Bone marrow samples harvested before therapy (day 0) or at weekly intervals during therapy with the indicated dose of R115777 were prepared for immunoblotting as described in “Patients, materials, and methods.” Inhibition of prelamin A and pre–HDJ-2 processing at the 100 and 300 mg bid doses was not detected. Prelamin A appeared in some samples obtained from patients during treatment with 600 and 900 mg (eg, LO and MH, lanes 8-13). In samples from other patients, lamin A was undetectable before treatment (MIT, lanes 14-17) or disappeared during the course of treatment (eg, MIR, lanes 18-21), making it impossible to use prelamin A as a marker of FT inhibition. In contrast, an increase in pre–HDJ-2 was detectable in many of these same samples, as illustrated in lanes 14-21 and summarized in Table 4. The median blast count for the day 1 samples shown in this figure was 90%.

Effect of R115777 on FT-dependent processing of prelamin A and HDJ-2 in K562 cells in vitro and in leukemic bone marrow samples in situ.

(A) Log-phase K562 cells were incubated for 24 hours with diluent (lane 1) or concentrations of R115777 ranging from 0.78 to 100 nM in 2-fold increments (lanes 2-11). At the completion of the incubation, samples were sedimented at 200g, washed once in serum-free RPMI 1640, and prepared for analysis as described in “Patients, materials, and methods.” R115777 causes a dose-dependent increase in signals for prelamin A and HDJ-2. (B) Bone marrow samples harvested before therapy (day 0) or at weekly intervals during therapy with the indicated dose of R115777 were prepared for immunoblotting as described in “Patients, materials, and methods.” Inhibition of prelamin A and pre–HDJ-2 processing at the 100 and 300 mg bid doses was not detected. Prelamin A appeared in some samples obtained from patients during treatment with 600 and 900 mg (eg, LO and MH, lanes 8-13). In samples from other patients, lamin A was undetectable before treatment (MIT, lanes 14-17) or disappeared during the course of treatment (eg, MIR, lanes 18-21), making it impossible to use prelamin A as a marker of FT inhibition. In contrast, an increase in pre–HDJ-2 was detectable in many of these same samples, as illustrated in lanes 14-21 and summarized in Table 4. The median blast count for the day 1 samples shown in this figure was 90%.

Inhibition of lamin A and HDJ-2 processing in leukemia marrow blasts

| R115777 dose (mg bid) . | No. positive for . | |

|---|---|---|

| Pre–HDJ-2 . | Prelamin A4-150 . | |

| 100 | 0/4 | 0/2 |

| 300 | 0/5 | 0/1 |

| 600 | 5/6 | 4/4 |

| 900 | 6/7 | 0/1 |

| R115777 dose (mg bid) . | No. positive for . | |

|---|---|---|

| Pre–HDJ-2 . | Prelamin A4-150 . | |

| 100 | 0/4 | 0/2 |

| 300 | 0/5 | 0/1 |

| 600 | 5/6 | 4/4 |

| 900 | 6/7 | 0/1 |

Effects on inhibition of ERK activation

The ERK kinases are phosphorylated at the end of a signal transduction pathway that starts with activated PTKs or activated Ras and progresses through Raf and MEK-1 kinases.15,16 53 To determine whether this pathway was inhibited by R115777, serial measurements of unphosphorylated and phosphorylated ERK were performed on bone marrow samples from 22 patients, 8 (36.4%) of which displayed constitutive ERK phosphorylation at baseline (Figure3). Following R115777, phospho-ERK became undetectable in 4 (50%) of the 8 patients in whom activated ERK was detectable in pretreatment samples.

Detection of ERK and phospho-ERK in leukemic marrow samples from 4 selected patients obtained before therapy (baseline) and at weekly intervals during R115777 administration.

ERK expression was detected before and after treatment in marrow samples from all 4 patients, and phospho-ERK as detected in 3 samples at baseline. Of note, phospho-ERK disappeared following R115777 treatment in samples from 2 of the 3 patients whose marrow populations exhibited baseline phospho-ERK expression.

Detection of ERK and phospho-ERK in leukemic marrow samples from 4 selected patients obtained before therapy (baseline) and at weekly intervals during R115777 administration.

ERK expression was detected before and after treatment in marrow samples from all 4 patients, and phospho-ERK as detected in 3 samples at baseline. Of note, phospho-ERK disappeared following R115777 treatment in samples from 2 of the 3 patients whose marrow populations exhibited baseline phospho-ERK expression.

Pharmacokinetics

Plasma pharmacokinetics were obtained during the first cycle of R115777 in 32 of the 35 patients entered on study. The data demonstrated a linear relationship between dose and Cmax or AUC12h for all dose levels tested, including 1200 mg bid (Figure 4). R115777 was rapidly absorbed with peak plasma concentrations reached within 2 to 3 hours. Pharmacokinetic parameters are shown in Table5. The T1/2 associated with the first phase of elimination, as determined on day 1, appeared to be independent of dose and ranged from 1.7 to 4.2 hours. The terminal T1/2 associated with the second phase of elimination, as determined on day 22, varied with the ability to quantify R115777 in plasma and ranged form 14.1 to 61.7 hours, with a median of approximately 20 hours. These data are consistent with a biphasic elimination curve, as described in the previous phase 1 study.37 Steady-state conditions were obtained within 3 days of bid dosing. The accumulation ratio was independent of dose and duration of administration, with an overall mean ratio (± SD) of 1.24 ± 0.69 on day 8 and 1.10 ± 0.83 on day 15, indicating little accumulation of R115777 following a bid dosing schedule.

Relationship between dose and AUC12h.

Day 1 individual (0) and mean (●) AUC12h achieved following oral administration of R115777 at dose levels 100 to 1200 mg bid. There is a dose-proportional relationship between R115777 dose and AUC12h for all doses from 100 to 1200 mg bid.

Relationship between dose and AUC12h.

Day 1 individual (0) and mean (●) AUC12h achieved following oral administration of R115777 at dose levels 100 to 1200 mg bid. There is a dose-proportional relationship between R115777 dose and AUC12h for all doses from 100 to 1200 mg bid.

Pharmacokinetics dose of R115777 (mg bid)

| . | 100 mg Mean ± SD . | 300 mg Mean ± SD . | 600 mg Mean ± SD . | 900 mg Mean ± SD . | 1 200 mg Mean ± SD . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | |||||

| Tmax, h | 3.2 ± 1.5 | 2.5 ± 1.0 | 2.9 ± 1.1 | 3.9 ± 2.0 | 3.3 ± 1.5 |

| Cmax, ng/mL | 282 ± 221 | 882 ± 224 | 1 728 ± 938 | 1 893 ± 1 549 | 2 615 ± 508 |

| AUC12h, ng · h/mL | 1 573 ± 1 489† | 3 763 ± 810 | 8 898 ± 4 493 | 9 080 ± 9 934 | 14 587 ± 603 |

| T1/2dom, h | 2.4 ± 0.7 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 3.3 ± 0.7 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 2.9 |

| No. patients tested | 6 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 3 |

| Day 8 | |||||

| C0h, ng/mL | 46.0 ± 35.6 | 88.8 ± 45.8 | 573 ± 488 | 430 ± 578 | ND |

| Tmax, h | 2.0 ± 0.9 | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 2.6 ± 1.2 | 2.7 ± 1.3 | ND |

| Cmax, ng/mL | 271 ± 165 | 811 ± 305 | 1 840 ± 875 | 1 680 ± 885 | ND |

| AUC12h, ng · h/mL | 1 459 ± 932 | 3 525 ± 1 306 | 10 274 ± 6 440 | 9 056 ± 6 490 | ND |

| Ratio AUC12h | 1.23 ± 0.66 | 0.96 ± 0.19 | 1.4 ± 0.79 | 1.26 ± 0.87 | ND |

| No. patients tested | 6 | 3 | 8 | 8 | 1 |

| Day 15 | |||||

| C0h, ng/mL | 60.7 ± 53.8 | 123 ± 103 | 245 ± 116 | 257 ± 443 | ND |

| Tmax, h | 1.6 ± 1.3 | 2.0 ± 0.0 | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 2.3 ± 1.0 | ND |

| Cmax, ng/mL | 266 ± 208 | 1 048 ± 708 | 1 192 ± 522 | 2 004 ± 1 151 | ND |

| AUC12h, ng · h/mL | 1 235 ± 466 | 4 330 ± 2 792 | 8 079 ± 3 419 | 7 154 ± 3 659 | ND |

| Ratio AUC12h | 1.00 ± 0.61 | 0.87 ± 0.41 | 0.85 ± 0.26 | 1.6 ± 1.46 | ND |

| No. patients tested | 5 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 0 |

| Day 22 | |||||

| T1/2term, h | 35.2 ± 23.0 | 16.4 | 20.3 ± 2.5 | 19.0 ± 5.4 | ND |

| No. patients tested | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 0 |

| . | 100 mg Mean ± SD . | 300 mg Mean ± SD . | 600 mg Mean ± SD . | 900 mg Mean ± SD . | 1 200 mg Mean ± SD . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | |||||

| Tmax, h | 3.2 ± 1.5 | 2.5 ± 1.0 | 2.9 ± 1.1 | 3.9 ± 2.0 | 3.3 ± 1.5 |

| Cmax, ng/mL | 282 ± 221 | 882 ± 224 | 1 728 ± 938 | 1 893 ± 1 549 | 2 615 ± 508 |

| AUC12h, ng · h/mL | 1 573 ± 1 489† | 3 763 ± 810 | 8 898 ± 4 493 | 9 080 ± 9 934 | 14 587 ± 603 |

| T1/2dom, h | 2.4 ± 0.7 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 3.3 ± 0.7 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 2.9 |

| No. patients tested | 6 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 3 |

| Day 8 | |||||

| C0h, ng/mL | 46.0 ± 35.6 | 88.8 ± 45.8 | 573 ± 488 | 430 ± 578 | ND |

| Tmax, h | 2.0 ± 0.9 | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 2.6 ± 1.2 | 2.7 ± 1.3 | ND |

| Cmax, ng/mL | 271 ± 165 | 811 ± 305 | 1 840 ± 875 | 1 680 ± 885 | ND |

| AUC12h, ng · h/mL | 1 459 ± 932 | 3 525 ± 1 306 | 10 274 ± 6 440 | 9 056 ± 6 490 | ND |

| Ratio AUC12h | 1.23 ± 0.66 | 0.96 ± 0.19 | 1.4 ± 0.79 | 1.26 ± 0.87 | ND |

| No. patients tested | 6 | 3 | 8 | 8 | 1 |

| Day 15 | |||||

| C0h, ng/mL | 60.7 ± 53.8 | 123 ± 103 | 245 ± 116 | 257 ± 443 | ND |

| Tmax, h | 1.6 ± 1.3 | 2.0 ± 0.0 | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 2.3 ± 1.0 | ND |

| Cmax, ng/mL | 266 ± 208 | 1 048 ± 708 | 1 192 ± 522 | 2 004 ± 1 151 | ND |

| AUC12h, ng · h/mL | 1 235 ± 466 | 4 330 ± 2 792 | 8 079 ± 3 419 | 7 154 ± 3 659 | ND |

| Ratio AUC12h | 1.00 ± 0.61 | 0.87 ± 0.41 | 0.85 ± 0.26 | 1.6 ± 1.46 | ND |

| No. patients tested | 5 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 0 |

| Day 22 | |||||

| T1/2term, h | 35.2 ± 23.0 | 16.4 | 20.3 ± 2.5 | 19.0 ± 5.4 | ND |

| No. patients tested | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 0 |

tmax indicates time to maximum plasma concentration; Cmax, maximum plasma concentration; AUC12h, area under the concentration curve at over 12 hours; T1/2dom, T1/2 dominant; C0h, trough plasma concentration; ND not done; T1/2term, T1/2 terminal.

Oral administration resulted in accumulation of R115777 in bone marrow cells in a dose-dependent manner. Whereas doses of 100 and 300 mg bid yielded mean day 8 drug levels of 160 ng/g cell pellet (range, 78-264), major increases in marrow R115777 levels were noted at 600 mg bid (mean day 8 level, 1723 ng/g cell pellet; range, 823-3920) and 900 mg bid (mean, 2942 ng/g cell pellet; range, 2032-3642). Comparison of bone marrow levels with the plasma Cmin obtained on day 8 for this subset of patients revealed that marrow levels were 2.5- to 3.5-fold higher than concomitant plasma levels (Cmin) at all dose levels (Table 6). Serial measurements indicated that marrow R115777 levels were relatively steady for all patients at each dose level from week to week administration (data not shown).

Comparison of day 8 bone marrow and plasma R115777 levels

| R115777 dose (mg bid) . | Marrow level (ng/g cell pellet)6-150 . | Plasma Cmin (ng/mL plasma)6-150 . | Marrow/plasma ratio6-150 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100-300 (5)6-151 | 153 (129-202) | 53 (25-109) | 2.9 (1.4-6.2) |

| 600 (7) | 1742 (812-3920) | 655 (322-1544) | 2.7 (2.0-3.7) |

| 900 (3) | 2942 (2032-3642) | 799 (171-1841) | 3.7 (1.7, 11.2, 11.9) |

| R115777 dose (mg bid) . | Marrow level (ng/g cell pellet)6-150 . | Plasma Cmin (ng/mL plasma)6-150 . | Marrow/plasma ratio6-150 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100-300 (5)6-151 | 153 (129-202) | 53 (25-109) | 2.9 (1.4-6.2) |

| 600 (7) | 1742 (812-3920) | 655 (322-1544) | 2.7 (2.0-3.7) |

| 900 (3) | 2942 (2032-3642) | 799 (171-1841) | 3.7 (1.7, 11.2, 11.9) |

Mean (range).

Number of patients with both marrow and plasma levels determined.

Discussion

The present phase 1 study represents the first clinical trial of a signal transduction inhibitor in patients with AML and ALL. In this cohort of patients, we found the toxicities of R115777 to be dose related and to consist of reversible renal toxicity, transient myelosuppression, and dose-limiting neurotoxicity. The observed neurotoxicity is consistent with the pivotal role that Ras plays in neuronal development and survival, particularly in response to nerve growth factor,54 where Ras participates through activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway.55 The etiology of the polydipsia, which occurred in the absence of osmotic diuresis (eg, diabetes), defects in pituitary function, or primary metabolic disturbances, is unclear at this time. Transient and reversible renal dysfunction was preceded by polydipsia in patients over 60 years old, but otherwise there was no clear link between the 2 disorders. Renal dysfunction, which has also been noted in previous phase 1 studies of the nonpeptidomimetic FTI SCH6633647 as well as R115777,37 might reflect a role for farnesylated proteins in maintaining normal glomerular and tubular functions.

Our studies demonstrate that R115777 accumulates in the bone marrow in a dose-dependent manner, reaches concentrations that equal or exceed Cmax, and remains present at sustained levels throughout the duration of administration. Overall, the pharmacokinetic studies support the notion that the twice-daily administration of R115777 over 7 to 21 days achieves steady-state drug concentrations in both plasma and marrow that are sufficient to inhibit FT activity in target leukemic marrow cells in a dose-dependent fashion. This inhibition was subsequently demonstrated using direct measurements of FT activity as well as assays for accumulation of prelamin A and especially pre–HDJ-2, 2 polypeptides whose processing is FT dependent. The ability to detect processed HDJ-2 in the majority of pretreatment marrow populations and the reproducible increase in unfarnesylated protein (pre–HDJ-2) detected in marrow samples from patients treated with at least 600 mg bid for at least 7 days suggests that this assay provides a consistent marker of functional enzyme inhibition. As such, this assay may be useful in monitoring R115777 therapy to ensure achievement of intracellular FTI levels that, in turn, translate into functional enzyme blockade. In contrast, lamin A was not expressed consistently in these marrow samples (Table 4),48 making assays for prelamin A less informative in these diseases.

In this phase 1 study, we were not able to discern a quantitative relationship between FT enzyme inhibition, the accumulation of pre–HDJ-2, and clinical response. Such correlations can be uncovered only with larger numbers of patients receiving a dose of R115777 that has been determined to be effective at least on the basis of intracellular biochemical activities. Phase 2 studies of R115777 in patients with AML receiving a more uniform dose are needed to address this important issue.

Multiple downstream targets appear to be affected by FT inhibition. The observation that R115777 results in ERK dephosphorylation raises the possibility that one target in these leukemic marrow cells might be the Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK pathway. Even though ERK phosphorylation was detected in only 36.4% of the leukemic marrow populations obtained prior to R115777, it disappeared in half of the leukemias where it was initially demonstrated. Likewise, the finding that 3 of the 5 patients with AML with chromosome 7 abnormalities, which are associated with aberrant Ras expression,52responded to R115777 also suggests that R115777 might exert its antileukemic effects, at least in part, by interrupting Ras function. On the other hand, the occurrence of clinical responses in the absence of detectable ras mutations is also noteworthy. Although this result might reflect inhibition of growth factor-driven Ras activation,15,17-19 the possibility that the antileukemic effects of R115777 are partially or completely Ras-independent cannot be ruled out. Recent studies have demonstrated that FTIs interfere with farnesylation and function of other proteins, including RhoB24-26 and possibly other intermediates in cell survival pathways.27 Unfortunately, RhoB is expressed in such limited amounts that it could not be analyzed in the present study.46 Thus, further studies are required to determine which FT substrate(s) is critical to the antileukemic effects of R115777 in the clinical setting.

Our results indicate that R115777 produces responses in roughly 30% of patients. The entry criteria were designed to include only patients who were likely to do poorly with traditional cytotoxic chemotherapies. In this small cohort of patients, the effects of R115777 were detected in AML variants and in myeloid CML-BC, but not in ALLs (including Ph+ variants). The observation that responsive patients tended to have a lower percentage of marrow blasts (< 40%) than nonresponders (> 70%) raises the possibility that responsive leukemic clones may be those with some residual capacity to differentiate. Consistent with this possibility, many patients achieved CR or PR without the profound marrow aplasia typically associated with induction chemotherapy. If R115777 is truly able to facilitate some differentiation of blasts, FTIs might find application in disease states such as high-risk MDS, where some capacity for differentiation still persists, or in minimal residual disease states, that is, after cytoreductive induction chemotherapy.

Multiple assays of farnesylation demonstrated that FT enzyme activity was reproducibly inhibited at doses of 600 mg bid. At this dose level, clinical responses were detected in 2 (29%) of 7 AMLs, nonhematologic toxicities were acceptable to patients and myelosuppression was transient (< 7 days). At the next higher dose level (900 mg bid), the nonhematologic toxicities were troublesome enough that 3 (27%) of that patient cohort were unable to receive 21 days of treatment. Based on the clinical and molecular data from this phase 1 study, it is reasonable to suggest a dose of 600 mg R115777 bid for phase 1I trials in hematologic malignancies, with possible dose escalation in selected cohorts of younger patients. Based on the promising results presented above, additional trials are needed to address several issues, including optimal duration of dosing to achieve CR or maximal clinical responses, duration of responses, and the effects of combining R115777 with traditional cytotoxic agents.

We wish to thank Chris Bowden for thoughtful advice; Maureen Craig, Kim Altobelli, Patrician Engelen, and Jacqueline Toner for technical expertise and assistance; and Veronica Greenidge for secretarial expertise.

Supported by National Cancer Institute Cooperative Agreement U01 CA69854 (J.E.K.) and by a grant from Janssen Research Foundation (J.R. and J.E.K.). J.L. is a Scholar in Clinical Research of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Judith E. Karp, University of Maryland Greenebaum Cancer Center, 22 S Greene St, Rm S9D07, Baltimore, MD 21201; e-mail:jkarp@umm.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal