Abstract

The aim of this study was to explore further the hypothesis that early stages of normal human hematopoiesis might be coregulated by autocrine/paracrine regulatory loops and by cross-talk among early hematopoietic cells. Highly purified normal human CD34+cells and ex vivo expanded early colony-forming unit–granulocyte-macrophage (CFU-GM)–derived, burst forming unit–erythroid (BFU-E)–derived, and CFU–megakaryocyte (CFU-Meg)–derived cells were phenotyped for messenger RNA expression and protein secretion of various growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines to determine the biological significance of this secretion. Transcripts were found for numerous growth factors (kit ligand [KL], FLT3 ligand, fibroblast growth factor–2 [FGF-2], vascular endothelial growth factor [VEGF], hepatocyte growth factor [HGF], insulinlike growth factor–1 [IGF-1], and thrombopoietin [TPO]); cytokines (tumor necrosis factor–α, Fas ligand, interferon α, interleukin 1 [IL-1], and IL-16); and chemokines (macrophage inflammatory protein–1α [MIP-1α], MIP-1β, regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted [RANTES], monocyte chemotactic protein–3 [MCP-3], MCP-4, IL-8, interferon-inducible protein–10, macrophage-derived chemokine [MDC], and platelet factor–4 [PF-4]) to be expressed by CD34+ cells. More importantly, the regulatory proteins VEGF, HGF, FGF-2, KL, FLT3 ligand, TPO, IL-16, IGF-1, transforming growth factor–β1 (TGF-β1), TGF-β2, RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, IL-8, and PF-4 were identified in media conditioned by these cells. Moreover, media conditioned by CD34+ cells were found to inhibit apoptosis and slightly stimulate the proliferation of other freshly isolated CD34+ cells; chemo-attract CFU-GM– and CFU-Meg–derived cells as well as other CD34+ cells; and, finally, stimulate the proliferation of human endothelial cells. It was also demonstrated that these various hematopoietic growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines are expressed and secreted by CFU-GM–, CFU-Meg–, and BFU-E–derived cells. It is concluded that normal human CD34+ cells and hematopoietic precursors secrete numerous regulatory molecules that form the basis of intercellular cross-talk networks and regulate in an autocrine and/or a paracrine manner the various stages of normal human hematopoiesis.

Introduction

The development of hematopoietic cells is regulated by hematopoietic growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines secreted in the bone marrow (BM) microenvironment by accessory cells (eg, fibroblasts, macrophages, osteoblasts, and endothelial cells) and T lymphocytes (eg, as part of TH1- and TH2-mediated responses),1-5 as well as by a variety of other mechanisms.1-3 Recently, we and others demonstrated the presence of messenger RNA (mRNA) for several regulatory proteins in normal human BM CD34+cells,6-12 megakaryocytes,11-14 and mononuclear cells (MNCs)15 and suggested that an intercellular cross-talk network and/or autocrine/paracrine regulatory loops may play a role in the regulation of normal hematopoiesis. In fact, positive regulatory loops mediated by interleukin 1(IL-1), kit-ligand (KL), FLT3 ligand, and erythropoietin (EPO), and negative ones mediated by transforming growth factor–β1 (TGF-β1), have been postulated.6,8,16,17 Moreover, the expression of mRNAs for various hematopoietic regulatory proteins was recently reported in murine fetal liver–derived hematopoietic stem cells.18

On the basis of these findings, we hypothesized that normal hematopoietic cells have developed mechanisms to communicate with each other. To investigate this possibility, we phenotyped highly purified normal human CD34+ cells and ex vivo expanded human colony-forming unit–granulocyte-macrophage (CFU-GM)–derived, burst forming unit–erythroid (BFU-E)–derived, CFU–megakaryocyte (CFU-Meg)–derived, and CFU-fibroblasts (CFU-F)–derived cells, not only for mRNA expression of growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines but also, and more importantly, by means of highly sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)–based immunoassays, for the presence of secreted proteins in media conditioned by these cells. Furthermore, to better define the role these regulatory proteins play in the biology of hematopoietic cells, we performed various functional assays. Conditioned media harvested from normal CD34+ cells were examined to see whether they would increase survival and/or stimulate proliferation of other freshly isolated CD34+cells, chemo-attract hematopoietic cells, and finally, stimulate endothelial cells.

We demonstrate, for the first time, that numerous growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines are secreted at physiological concentrations by normal human CD34+ cells and myeloid, erythroid, and megakaryocytic precursor cells, and we provide evidence for the existence of intercellular cross-talk networks and autocrine and/or paracrine regulation of normal hematopoiesis.

Materials and methods

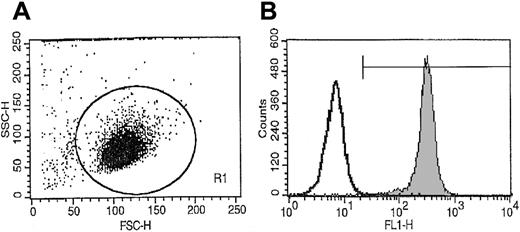

Normal human hematopoietic cells and CD34+ selection by fluorescence-activated cell sorting

Light-density BM MNCs were obtained from consenting healthy donors and depleted of adherent cells and T lymphocytes (A−T− MNCs) as described.19-22A−T− MNCs were enriched for CD34+cells by an immuno-affinity selection with MiniMacs (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) paramagnetic beads as previously described.19,20 Mobilized peripheral blood (mPB) cells were obtained from granuloctye-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF)–mobilized breast cancer patients, and CD34+ cells were isolated as described by us previously.23 The purity of the isolated CD34+ cells was greater than 97% as established by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis (Figure 1). The c-kit receptor positive (c-kit–R+) subset of CD34+ cells was isolated by FACS as described.19 Briefly, 2 × 107human A−T− MNCs were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 5% bovine calf serum (BCS) and labeled for 30 minutes at 4°C with anti–kit-R monoclonal antibodies (clone No. 104D2) directly conjugated with Cy5 (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) (20 μL per 106 cells) and with an anti-CD34 monoclonal antibody directly conjugated with phycoerythrin (PE anti–HPCA-2) (Becton Dickinson) (20 μL per 106cells). After the final incubation, cells were washed 3 × in ice-cold PBS supplemented with 5% BCS and then subjected to FACS analysis with a FACS Star Plus II (Becton Dickinson). The purity of the isolated CD34+kit+ cells was greater than 98%.

Representative FACS analysis of CD34+ cell purity isolated from BM MNCs using paramagnetic immuno-beads.

More than 98% of sorted cells expressed CD34+ antigen on the surface.

Representative FACS analysis of CD34+ cell purity isolated from BM MNCs using paramagnetic immuno-beads.

More than 98% of sorted cells expressed CD34+ antigen on the surface.

Human myeloid, erythroid, and megakaryocytic precursor cells

CD34+ cells were expanded in a serum-free liquid system as previously described.11,19,24 Briefly, CD34+ A−T− MNCs (104/mL) were resuspended in Iscoves Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NJ) supplemented with 25% artificial serum containing 1% delipidated, de-ionized and charcoal-treated bovine serum albumin, 0.27 g/L iron-saturated transferrin, insulin (20 μg/mL), and 2 mM l-glutamine (all from Sigma, St Louis, MO). CFU-GM growth was stimulated with recombinant human (rh) IL-3 (10 ng/mL) plus rh granulocyte-macrophage CSF (GM-CSF) (5 ng/mL). BFU-E growth was stimulated with rhEPO (2000 IU/L) plus rhKL (10 ng/mL). CFU-Meg growth was stimulated with rh thrombopoietin (TPO) (50 ng/mL) plus rhIL-3 (10 ng/mL). Cytokines were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Cultures were incubated at 37°C in a fully humidified atmosphere supplemented with 5% CO2. Under these conditions, approximately 100% of BFU-E–derived cells were glycophorin-A+; 100% of CFU-GM–derived cells were glycophorin-A+ and αIIb/β and expressed CD33; and 85% of CFU-Meg–derived cells were αIIb/β. These CFU-Meg–derived cells were further enriched for populations of αIIb/β cells (greater than 97% purity) by additional selection with immunomagnetic α-CD61 beads (Miltenyi Biotec). BM-derived fibroblasts were expanded and cultured as described previously.19

Reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction

CD34+ cells and CFU-GM–, BFU-E–, CFU-Meg–, and CFU-F–derived cells were analyzed by reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for mRNA expression of various cytokines and growth factors. Briefly, cells were lysed in 200 μL RNAzol (Biotecx Labs, Houston, TX) plus 22 μL chloroform as described.19-22 The aqueous phase was collected and mixed with 1 vol isopropanol (Sigma). RNA was precipitated overnight at −20°C. The RNA pellet was washed in 75% ethanol and resuspended in 3 × autoclaved H2O. Subsequently, mRNA (0.5 μg) was reverse-transcribed with 500 U Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase and 50 pmol of an oligodeoxynucleotide primer complementary to the 3′ end of the reported gene sequences of the appropriate growth factors and cytokines. The resulting complementary DNA (cDNA) fragments were amplified (for 30 cycles) by means of 5 U Thermus aquaticus (Taq) polymerase and primers specific for the 5′ end of the gene sequences of the detected growth factors and cytokines. Amplified products (10 μL) were electrophoresed on a 2% agarose gel and transferred to a nylon filter and further documented photographically. The sequences of primers employed in this study are shown in Table 1.

Sequences of the primers used in reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction studies

| Factor detected . | Sense primer . | Antisense primer . |

|---|---|---|

| KL | GAC AGC TTG ACT GAT CTT CTG GAC | ACT GCT GTC ATT CCT AAG GGA GCT |

| FLT3 L | AAC AAC CTA TCT CCT CCT GCT | GGC ACA TTT GGT GAC AAA GTG |

| M-CSF | TGT TGT TGG TCT GTC TCC TGG | TTC TCC AGC AAC TGG AGA GGT |

| FGF-2 | GGC CAC TTC AAG GAC CCC AAG | TCA GCT CTT AGC AGA CA |

| VEGF | TCG GGC CTC CGA AAC CAT GA | CCT GGT GAG AGA TCT GGT TC |

| HGF | GAG GGA CAT AAG AAA AGA AGA | GTG TGG TAT CAT GGA ACT CCA |

| IGF-1 | ACA TCT CCC ATC TCT CTG GAT TTC CTT TTG | CCC TCT ACT TGC GTT CTT CAA ATG TAC TTC |

| NGF-β | ACA GTT TTA CCA AGG GAG CAG | ATG ATG ACC GCT TGC TCC TGT |

| IL-1β | AGT GAA ATG ATG GCT TAT TAC | TAC ACT CTC CAG CTG TAG AGT |

| IL-3 | GCT CCC ATG ACC CAG ACA ACG TCC | CAG ATA GAA CGT CAG TTT CCT CCG |

| IL-6 | AAC TCC TTC TCC ACA AGC GCC TT | CCG AAG AGC CCT CAG GCT GG |

| IL-16 | CAC TCC CAA AGT TTA CAA GTC | GAG ATT CCT CAG CCT GTG TTG |

| EPO | ATC ACG ACG GGC TGT GCT GAA CAC | GGG AGA TGG CTT CCT TCT GGG CTC |

| TPO | TGC TCC GAG GAA AGG TGC GTT | GGG AAG AGC GTA TAC TGT CCA |

| G-CSF | GCC AGC TCC CTG CCC CAG AGC TTC | GTG TGT CCA AGG TGG GAC CCA ACT |

| GM-CSF | CAG GAG GCC CGG CGT CTC CTG AAC | ACA AGC AGA AAG TCC TTC AGG TTC |

| TNF-α | CAG AGG GAA GAG TTC CCC AG | TTG ACC TTG GTC TGG TAG GAG |

| IFN-α | CTT TGC TTT ACT GAT GGT CCT G | GAT CTC ATG ATT TCT GCT CTG |

| Fas-L | CAA GTC CAA CTC AAG GTC CAT GCC | CAG AGA GAG CTC AGA TAC GTT GAC |

| MIP-1α | CCT TGC TGT CCT CCT CTG CAC | CAC TCA GCT CCA GGT CGC TGA |

| MIP-1β | TGT CCT CCT CAT GCT AGT AG | GTA CTC CTG GCC CAG GAT TC |

| RANTES | TCA TTG CTA CTG CCC TCT GCG | CTC ATC TCC AAA GAG TTG ATG |

| MCP-1 | GCT GCT CAT AGC AGC CAC CTT | ACA ATG GTC TTG AAG ATC ACA |

| MCP-2 | TGC TGA AGC TCA CAC CCT TGC | TGG TCC AGA TGC TTC ATG GAA |

| MCP-3 | ACT GAA CTG AAA ACA AGC CA | TCC AAG GCT TTA TGT TCA AA |

| MCP-4 | AGC TGG AGT ACG TGA AAT GA | AGC TCA TAG TGG AAG GGA AG |

| IL-8 | GCT TTC TGA TGG AAG AGA GCT | CTT GGA TAC CAC AGA GAA TGA |

| IP-10 | CCT GCT TCA AAT ATT TCC CT | CCT TCC TGT ATG TGT TTG GA |

| MDC | GCT CGC CTA CAG ACT GCA CTC CTG | GCT TAT TGA GAA TCA TCT TCA CCC AGG |

| SDF-1 | AAC GCC AAG GTC GTG GTC GTG CTG | CAC ATG TTG AAC CTC TTG TTT AAA AGC |

| PF-4 | GTC CAG TGG CAC CCT CTT GA | AAT TGA CAT TTA GGC AGC TGA |

| Factor detected . | Sense primer . | Antisense primer . |

|---|---|---|

| KL | GAC AGC TTG ACT GAT CTT CTG GAC | ACT GCT GTC ATT CCT AAG GGA GCT |

| FLT3 L | AAC AAC CTA TCT CCT CCT GCT | GGC ACA TTT GGT GAC AAA GTG |

| M-CSF | TGT TGT TGG TCT GTC TCC TGG | TTC TCC AGC AAC TGG AGA GGT |

| FGF-2 | GGC CAC TTC AAG GAC CCC AAG | TCA GCT CTT AGC AGA CA |

| VEGF | TCG GGC CTC CGA AAC CAT GA | CCT GGT GAG AGA TCT GGT TC |

| HGF | GAG GGA CAT AAG AAA AGA AGA | GTG TGG TAT CAT GGA ACT CCA |

| IGF-1 | ACA TCT CCC ATC TCT CTG GAT TTC CTT TTG | CCC TCT ACT TGC GTT CTT CAA ATG TAC TTC |

| NGF-β | ACA GTT TTA CCA AGG GAG CAG | ATG ATG ACC GCT TGC TCC TGT |

| IL-1β | AGT GAA ATG ATG GCT TAT TAC | TAC ACT CTC CAG CTG TAG AGT |

| IL-3 | GCT CCC ATG ACC CAG ACA ACG TCC | CAG ATA GAA CGT CAG TTT CCT CCG |

| IL-6 | AAC TCC TTC TCC ACA AGC GCC TT | CCG AAG AGC CCT CAG GCT GG |

| IL-16 | CAC TCC CAA AGT TTA CAA GTC | GAG ATT CCT CAG CCT GTG TTG |

| EPO | ATC ACG ACG GGC TGT GCT GAA CAC | GGG AGA TGG CTT CCT TCT GGG CTC |

| TPO | TGC TCC GAG GAA AGG TGC GTT | GGG AAG AGC GTA TAC TGT CCA |

| G-CSF | GCC AGC TCC CTG CCC CAG AGC TTC | GTG TGT CCA AGG TGG GAC CCA ACT |

| GM-CSF | CAG GAG GCC CGG CGT CTC CTG AAC | ACA AGC AGA AAG TCC TTC AGG TTC |

| TNF-α | CAG AGG GAA GAG TTC CCC AG | TTG ACC TTG GTC TGG TAG GAG |

| IFN-α | CTT TGC TTT ACT GAT GGT CCT G | GAT CTC ATG ATT TCT GCT CTG |

| Fas-L | CAA GTC CAA CTC AAG GTC CAT GCC | CAG AGA GAG CTC AGA TAC GTT GAC |

| MIP-1α | CCT TGC TGT CCT CCT CTG CAC | CAC TCA GCT CCA GGT CGC TGA |

| MIP-1β | TGT CCT CCT CAT GCT AGT AG | GTA CTC CTG GCC CAG GAT TC |

| RANTES | TCA TTG CTA CTG CCC TCT GCG | CTC ATC TCC AAA GAG TTG ATG |

| MCP-1 | GCT GCT CAT AGC AGC CAC CTT | ACA ATG GTC TTG AAG ATC ACA |

| MCP-2 | TGC TGA AGC TCA CAC CCT TGC | TGG TCC AGA TGC TTC ATG GAA |

| MCP-3 | ACT GAA CTG AAA ACA AGC CA | TCC AAG GCT TTA TGT TCA AA |

| MCP-4 | AGC TGG AGT ACG TGA AAT GA | AGC TCA TAG TGG AAG GGA AG |

| IL-8 | GCT TTC TGA TGG AAG AGA GCT | CTT GGA TAC CAC AGA GAA TGA |

| IP-10 | CCT GCT TCA AAT ATT TCC CT | CCT TCC TGT ATG TGT TTG GA |

| MDC | GCT CGC CTA CAG ACT GCA CTC CTG | GCT TAT TGA GAA TCA TCT TCA CCC AGG |

| SDF-1 | AAC GCC AAG GTC GTG GTC GTG CTG | CAC ATG TTG AAC CTC TTG TTT AAA AGC |

| PF-4 | GTC CAG TGG CAC CCT CTT GA | AAT TGA CAT TTA GGC AGC TGA |

KL indicates kit ligand; FLT3 L, FLT ligand; M-CSF, macrophage colony-stimulating factor; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; IGF, insulin-like growth factor; NGF, nerve growth factor; IL, interleukin; EPO, erythropoietin; TPO, thrombopoietin; G-CSF, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; IFN, interferon; Fas-L, Fas ligand; MIP, macrophage inflammatory protein; MCP, monocyte chemoattractant protein; SDF, stromal cell–derived factor; PF, platelet factor.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

The secretion of growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines by hematopoietic cells was evaluated by Quantikine human immunoassays (all from R&D) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Equal numbers (1 × 106/mL) of CD34+ cells or normal human CFU-GM–, BFU-E–, CFU-Meg–, and BM stroma–derived cells that had been cultured for 24 hours in serum-free conditions prior to the harvesting of the conditioned media were used. The collected media were analyzed by a quantitative sandwich enzyme immunoassay technique. The sensitivity of the ELISA assays was as follows: hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), greater than 40 pg/mL; vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), greater than 5 pg/mL; TPO, greater than 15 pg/mL; fibroblast growth factor–2 (FGF-2), greater than 3 pg/mL; TGF-β1, greater than 31 pg/mL; TGF-β2, greater than 31 pg/mL; GM-CSF, greater than 7 pg/mL; insulin-like growth factor–1 (IGF-1), greater than 12 pg/mL; FLT3 ligand, greater than 7 pg/mL; KL, greater than 3 pg/mL; IL-16, greater than 31 pg/mL; macrophage inflammatory protein–1α (MIP-1α), greater than 31 pg/mL; MIP-1β, greater than 31 pg/mL; monocyte chemoattractant protein–1 (MCP-1), greater than 31 pg/mL; platelet factor–4 (PF-4), greater than 10 pg/mL; and IL-8, greater than 1 pg/mL.

Chemotaxis studies

All experiments were performed in triplicate on BM MNCs, highly purified CD34+ cells, or serum-free expanded myeloid, erythroid, or megakaryocytic cells. Briefly, after isolation, the cells were resuspended in serum-free medium (106/mL) and equilibrated for 10 minutes at 37°C. In the meantime, 600 μL per point of prewarmed serum-free conditioned medium was added to the lower chamber of the Costar Transwell 24-well plate, 6.5 mm diameter, 5 μM pore filter (Costar Corning, Cambridge, MA). Subsequently, 100 μL aliquots of the cell suspension were distributed to the upper chambers, and cultures were incubated at 37°C, 95% humidity, 5% CO2, for 4 hours. The plates were evaluated under an inverted microscope: cells from the lower chambers were collected, and cell number was scored by means of FACScan (Becton Dickinson) as described.22 The cells were gated according to their forward-scatter characteristics (FSCs) and side-scatter characteristics (SSCs) and counted during a 20-second acquisition. The results of chemotaxis of the BM MNCs were recorded by cytometer and shown as the number of events registered in the particular gates. In some chemotaxis experiments, in which highly purified CD34+ cells and BFU-E–, CFU-GM–, and CFU-Meg–derived cells were employed, the results are presented as a migration index: the ratio of (1) the number of cells that migrated toward the conditioned medium that was being tested to (2) the number of cells that migrated toward the serum-free culture medium.

Effects of CD34+ cell–conditioned media on survival and proliferation of CD34+ cells

Purified CD34+ cells were seeded at a density of 1 to 5 × 105/mL in serum-free medium not conditioned (see above) or conditioned by CD34+ cells (2 × 106/mL per 24 hours). After 7 days, the number of living cells was evaluated by the 0.5% trypan blue exclusion test, and the cells were plated in methylcellulose or plasma clot cultures and stimulated to grow CFU-GM, BFU-E, and CFU-Meg colonies. Briefly, CD34+ cells (1 × 104) were cloned in 1 mL Iscoves modified Dulbecco medium supplemented with artificial serum as described above.19-22 Recombinant human growth factors appropriate to the colonies to be grown were added to the mixture, which was then transferred to 3.5-cm plastic petri dishes and incubated (37°C, 95% air, 5% CO2, in a humidified atmosphere). The growth factors and concentrations used were EPO (5000 IU/L) plus KL (100 ng/mL) for BFU-E; IL-3 (20 U/mL) plus GM-CSF (5 ng/mL) for CFU-GM; and TPO (50 ng/mL) for CFU-Meg. Colonies were counted under an inverted microscope on day 11 for CFU-GM and CFU-Meg and on day 14 for BFU-E colonies.

Activation of caspase-3 was determined by FACS through the employing of intracellular staining with a monoclonal antibody that recognizes the activated form of caspase-3 according to the manufacturer's protocols (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA).

Effects of rh factors on survival and proliferation of CD34+ cells

We isolated 1 × 105CD34+kit-R+ MNCs by FACS and then resuspended them in Iscove's DMEM containing the serum-free supplement described previously. The cells were cultured in 6-well plastic plates in the presence (or absence) of rh insulin (20 μg/mL), rhVEGF (100 ng/mL), rhHGF (100 ng/mL), rhFGF-2 (100 ng/mL), rhIGF-1 (100 ng/mL), rhKL (100 ng/mL), and rhFLT3 ligand (100 ng/mL) for 72 hours (37°C, 95% humidity, 5% CO2) and then washed 1 × in PBS before fixation in 4% neutral-buffered formalin. After fixation, the cells were sedimented by gravity onto slides covered with Cell-Tak tissue adhesive (Collaborative Biomedical Products, Bedford, MA). Apoptosis was detected in these cells by means of the in situ apoptosis detection kit Apoptag (Oncor, Gaithersburg, MD) according to the manufacturer's protocol as described.20 25 In this assay, terminal deoxynucleotide transferase was used to label the fragmented ends of DNA that have undergone apoptosis with digoxigenin–deoxyuridine triphosphate. The digoxigenin label was subsequently labeled with anti-digoxygenin antibody, which allowed simple, direct enumeration of apoptotic cells with a fluorescence microscope. Activation of caspase-3 was determined by FACS according to the manufacturer's protocol (BD Pharmingen).

Proliferation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were isolated as previously described in detail.26 The cells were seeded 24 hours before the experiment in 96-well plates coated with fibronectin in growth medium (M199, 90%; fetal calf serum, 10%; bovine brain extract, 1 mg/mL; human epidermal growth factor, 1 ng/mL; hydrocortisone, 1 mg/mL; heparin, 10 U/mL) at a density of 2.5 × 103. The next day, the wells were washed 3 × with sterile, prewarmed PBS, and subsequently we added 100 μL prewarmed growth medium, serum-free medium, or serum-free medium conditioned by CD34+ cells (the last was obtained by culturing CD34+ cells at 2 × 106/mL for 24 hours in serum-free medium). On days 2 and 4, the media were replaced by fresh ones. On day 6, the proliferative status of the cells was evaluated by means of a colorimetric assay (Celltiter 96; Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 20 μL Aqueous One Solution was added to each well, and the plate was incubated for 4 hours at 37°C in a humidified, 5% CO2atmosphere. The plate was then read at 490 nm by means of a 96-well plate reader, and the background absorbance of the culture medium was subtracted to yield the correct absorbance.

Statistical analysis

Arithmetic means and SDs were calculated on a MacIntosh computer with Instat 1.14 (Graphpad, San Diego, CA) software. Data were analyzed by means of the Student t test for unpaired samples. Statistical significance was defined as P < .05.

Results

Numerous growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines are expressed by normal human BM and mPB CD34+ cells, erythroblasts, megakaryoblasts, and myeloblasts

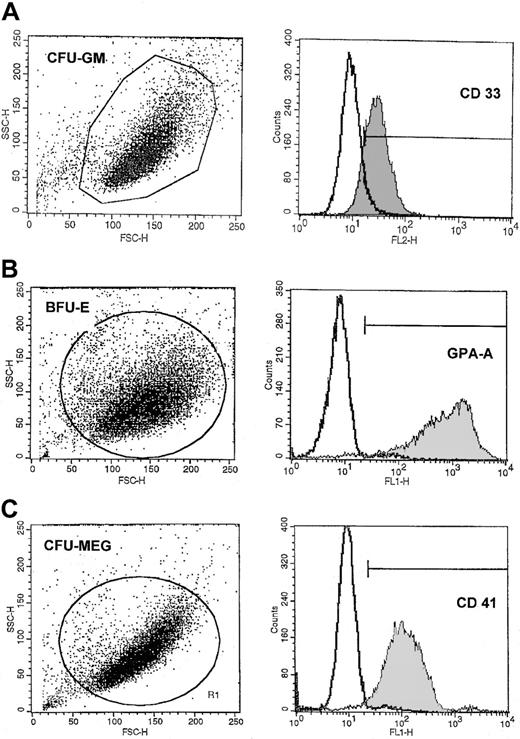

The expression of mRNA for various hematopoietic growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines in normal human highly purified BM and mPB CD34+ cells and CFU-GM– (CD33+), BFU-E– (GPA-A+), CFU-Meg– (CD41+), and CFU-F–derived cells is shown in Table2. The purity of these cells is shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction analysis of highly purified CD34+ cells (n = 3 for bone marrow and n = 5 for peripheral blood), myeloblasts, erythroblasts, megakaryoblasts, and bone marrow–derived fibroblasts (n = 3 for each) for expression of various growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines

| . | CD34+ BM . | CD34+PB . | CFU-GM– derived . | BFU-E– derived . | CFU-Meg– derived . | CFU-F– derived . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KL | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| FLT3 L | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| M-CSF | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| FGF-2 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| VEGF | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| HGF | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| IGF-1 | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| NGF-β | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| IL-1β | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| IL-3 | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| IL-6 | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| IL-16 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| EPO | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| TPO | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| G-CSF | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| GM-CSF | − | + | − | − | + | + |

| TNF-α | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| IFN-α | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Fas-L | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| MIP-1α | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| MIP-1β | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| RANTES | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| MCP-1 | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| MCP-2 | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| MCP-3 | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| MCP-4 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| IL-8 | + | + | − | − | + | − |

| IP-10 | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| MDC | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| SDF-1 | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| PF-4 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| . | CD34+ BM . | CD34+PB . | CFU-GM– derived . | BFU-E– derived . | CFU-Meg– derived . | CFU-F– derived . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KL | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| FLT3 L | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| M-CSF | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| FGF-2 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| VEGF | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| HGF | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| IGF-1 | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| NGF-β | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| IL-1β | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| IL-3 | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| IL-6 | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| IL-16 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| EPO | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| TPO | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| G-CSF | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| GM-CSF | − | + | − | − | + | + |

| TNF-α | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| IFN-α | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Fas-L | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| MIP-1α | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| MIP-1β | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| RANTES | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| MCP-1 | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| MCP-2 | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| MCP-3 | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| MCP-4 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| IL-8 | + | + | − | − | + | − |

| IP-10 | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| MDC | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| SDF-1 | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| PF-4 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

CFU-GM indicates colony-forming unit–granulocyte-macrophage; BFU-E, burst forming unit–erythroid; CFU-Meg, colony-forming unit–megakaryocyte; CFU-F, CFU-fibroblasts. For other abbreviations, see footnote to Table 1.

Representative FACS analysis of purity of CFU-GM–, BFU-E–, and CFU-MEG–derived cells.

The expression of CD33 (A), GPA-A (B), and CD41 (C) on (A) human CFU-GM–, (B) BFU-E–, and (C) CFU-Meg–derived cells (myeloblasts, erythroblasts, and megakaryoblasts, respectively). Lineage-specific cells were expanded from CD34+ cells under serum-free conditions as described in “Materials and methods.”

Representative FACS analysis of purity of CFU-GM–, BFU-E–, and CFU-MEG–derived cells.

The expression of CD33 (A), GPA-A (B), and CD41 (C) on (A) human CFU-GM–, (B) BFU-E–, and (C) CFU-Meg–derived cells (myeloblasts, erythroblasts, and megakaryoblasts, respectively). Lineage-specific cells were expanded from CD34+ cells under serum-free conditions as described in “Materials and methods.”

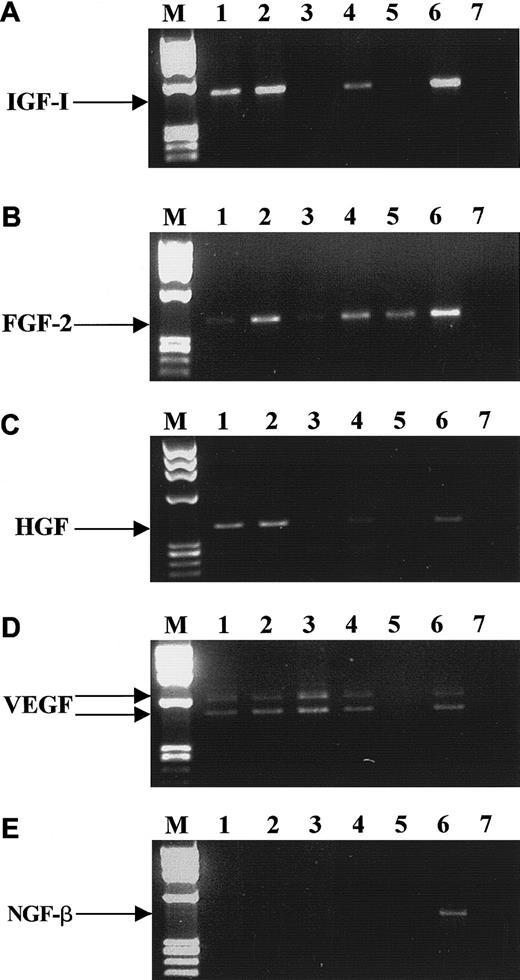

The hematopoietic growth factors we selected for these studies are known to be important regulators of mesodermal development and to activate receptors possessing intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity. We found that both BM- and mPB-derived CD34+ cells express mRNA for KL, FLT3 ligand, FGF-2, VEGF, HGF, and IGF-1 (Table 2), but not for macrophage CSF or NGF-β. However, mRNAs for many of these factors were found to be expressed in CFU-GM–, BFU-E–, CFU-Meg–, and CFU-F–derived cells, and Figure3 shows representative (4 to 8 samples) RT-PCR data for IGF-1, FGF-2, HGF, VEGF, and NGF-β mRNA expression. Table 2 shows mRNAs encoding hematopoietic cytokines in normal human BM or mPB CD34+ cells and precursor cells of various hematopoietic lineages. We found that normal human BM and mPB CD34+ cells express mRNA for growth factors and cytokines that may stimulate cell proliferation (TPO and IL-1) or, alternatively, inhibit it (tumor necrosis factor α[TNF-α], interferon α[IFN-α] and Fas ligand [Fas-L]). However, we were not able to detect mRNA for other growth factors and cytokines (IL-3, IL-6, EPO, G-CSF, and GM-CSF) in these cells. Interestingly, CD34+ cells expressed mRNA for IL-16, which is a ligand for CD4, a known membrane receptor for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).59 CFU-GM–, BFU-E–, CFU-Meg–, and CFU-F–derived cells also expressed IL-16. While human CFU-GM–, BFU-E–, and CFU-Meg–derived cells expressed mRNA only for TPO, TNF-α, IFN-α, and Fas-L, CFU-F–derived fibroblasts expressed mRNA for all the cytokines tested except for IL-1 and EPO.

RT-PCR analysis of mRNA expression for various growth factors by CD34+ cells.

IGF-1 (A), FGF-2 (B), HGF (C), VEGF (D), and NGF-β (E). Lane 1, purified BM CD34+ cells; lane 2, BFU-E–derived cells; lane 3, CFU-GM–derived cells; lane 4, CFU-Meg–derived cells; lane 5, platelets; lane 6, stromal cells; lane 7, negative control of RT-PCR reaction (H2O instead of mRNA). The data are representative of 4 to 8 experiments using cells separated from different donors.

RT-PCR analysis of mRNA expression for various growth factors by CD34+ cells.

IGF-1 (A), FGF-2 (B), HGF (C), VEGF (D), and NGF-β (E). Lane 1, purified BM CD34+ cells; lane 2, BFU-E–derived cells; lane 3, CFU-GM–derived cells; lane 4, CFU-Meg–derived cells; lane 5, platelets; lane 6, stromal cells; lane 7, negative control of RT-PCR reaction (H2O instead of mRNA). The data are representative of 4 to 8 experiments using cells separated from different donors.

We also demonstrated mRNAs for chemokines such as MIP-1α, MIP-1β, RANTES, MCP-3, MCP-4, IL-8, inducible protein 10(IP-10), MDC, and PF-4 in highly purified human BM and mPB CD34+ cells (Table 2). In addition, mPB-derived CD34+ cells expressed mRNA for MCP-2. To our surprise, mRNA for stromal cell–derived factor–1 (SDF-1) and MCP-1 was not expressed in either BM- or mPB-derived CD34+ cells.27 We found that CFU-GM–, BFU-E–, CFU-Meg–, and CFU-F–derived cells also expressed mRNA for various chemokines, but mRNAs for SDF-1 and MCP-1 were found only in CFU-F–derived fibroblasts. We are aware, however, that even though we used highly purified human primary cells, the possibility remained that these cells could be cross-contaminated by other cells and that RT-PCR analysis, even if performed on highly purified cell fractions, is not always conclusive. Also, even if an appropriate mRNA is expressed, it does not necessarily mean that the corresponding protein is synthesized and/or secreted by the cells.

Numerous growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines are secreted by CD34+ cells, erythroblasts, megakaryoblasts, and myeloblasts

Hence, our next step was to attempt to correlate these RT-PCR findings with protein secretion, using sensitive, commercially available ELISA assays. We found that normal human BM-derived CD34+ cells, myeloblasts, erythroblasts, megakaryoblasts, and BM fibroblasts secrete detectable amounts of various hematopoietic growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines (Tables3, 4, and5). These various regulatory proteins were secreted by highly purified CD34+ cells at picogram levels, which could potentially affect their proliferation either by stimulating (eg, KL, FLT3 ligand, and TPO) or inhibiting it (eg, TGF-β1, TGF-β2, and PF-4). Further, these secreted proteins (KL, FLT3 ligand, TPO, and IGF-1) could autoprotect CD34+ cells from undergoing apoptosis. Moreover, proteins such as VEGF, HGF, FGF-2, and IL-8 could attract and/or stimulate human endothelial cells. We confirmed our previous observations that CD34+ cells secrete several HIV-related β-chemokines that could protect these cells from infection by R5 (macrophagotropic) HIV,11,12 and we report here, for the first time, that highly purified human CD34+ cells secrete IL-16, another factor that may interfere with HIV infection.28

Levels of various growth factors and cytokines detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (pg/mL) in media conditioned by normal human hematopoietic cells (n = 3)

| Factor detected . | CD34+ cells BM . | CFU-GM– derived . | BFU-E– derived . | CFU-Meg– derived . | Stroma . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VEGF | 20 ± 7 | 394 ± 35 | 820 ± 22 | 230 ± 22 | 2103 ± 295 |

| HGF | 112 ± 19 | bsd3-150 | bsd | bsd | 1542 ± 279 |

| FGF-2 | 12 ± 3 | bsd | bsd | 13 ± 2 | bsd |

| KL | 18 ± 3 | bsd | —3-151 | bsd | 421 ± 111 |

| FLT3 L | 15 ± 3 | 14 ± 3 | bsd | bsd | 92 ± 12 |

| IGF-1 | 93 ± 21 | — | — | bsd | — |

| IL-16 | 123 ± 29 | bsd | bsd | bsd | — |

| TGF-β1 | 1104 ± 350 | — | 275 ± 48 | 1713 ± 391 | 1954 ± 231 |

| TGF-β2 | 121 ± 27 | — | — | bsd | 313 ± 59 |

| TPO | 34 ± 11 | bsd | bsd | — | 42 ± 19 |

| TNF-α | bsd | — | bsd | bsd | — |

| IFN-α | bsd | — | bsd | bsd | bsd |

| IFN-γ | bsd | — | bsd | bsd | — |

| GM-CSF | bsd | — | — | bsd | 545 ± 87 |

| Factor detected . | CD34+ cells BM . | CFU-GM– derived . | BFU-E– derived . | CFU-Meg– derived . | Stroma . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VEGF | 20 ± 7 | 394 ± 35 | 820 ± 22 | 230 ± 22 | 2103 ± 295 |

| HGF | 112 ± 19 | bsd3-150 | bsd | bsd | 1542 ± 279 |

| FGF-2 | 12 ± 3 | bsd | bsd | 13 ± 2 | bsd |

| KL | 18 ± 3 | bsd | —3-151 | bsd | 421 ± 111 |

| FLT3 L | 15 ± 3 | 14 ± 3 | bsd | bsd | 92 ± 12 |

| IGF-1 | 93 ± 21 | — | — | bsd | — |

| IL-16 | 123 ± 29 | bsd | bsd | bsd | — |

| TGF-β1 | 1104 ± 350 | — | 275 ± 48 | 1713 ± 391 | 1954 ± 231 |

| TGF-β2 | 121 ± 27 | — | — | bsd | 313 ± 59 |

| TPO | 34 ± 11 | bsd | bsd | — | 42 ± 19 |

| TNF-α | bsd | — | bsd | bsd | — |

| IFN-α | bsd | — | bsd | bsd | bsd |

| IFN-γ | bsd | — | bsd | bsd | — |

| GM-CSF | bsd | — | — | bsd | 545 ± 87 |

Cells were cultured for 24 hours in serum-free medium at a concentration of 1 × 106/mL of medium.

BM indicates bone marrow; bsd, below sensitivity of detection. See footnotes to Tables 1 and 2 for other abbreviations.

The sensitivities of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (pg/mL) were as follows: HGF > 40, VEGF > 5, TPO > 15, FGF2 > 3, TGF-β1 > 31, TGF-β2 > 31, GM-CSF > 7, IFN-α > 5, IFN-γ > 10, TNF-α > 10, IGF-1 > 12, IL-16 > 31 pg/mL, FLT3 ligand > 7, and KL > 3.

A dash indicates not done.

Levels of various chemokines detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (pg/mL) in media conditioned by normal human hematopoietic cells (n = 5)

| Factor detected . | CD34+ cells BM . | CFU-GM– derived . | BFU-E– derived . | CFU-Meg– derived . | Stroma . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIP-1α | 2012 ± 477 | bsd4-150 | bsd | bsd | 350 ± 42 |

| MIP-1β | 1309 ± 317 | bsd | bsd | bsd | —4-151 |

| RANTES | 174 ± 29 | bsd | bsd | 2227 ± 431 | 472 ± 63 |

| IL-8 | 103 ± 21 | — | — | 823 ± 54 | 397 ± 45 |

| PF-4 | 130 ± 25 | bsd | bsd | 9597 ± 862 | bsd |

| MCP-1 | bsd | bsd | bsd | bsd | 4221 ± −889 |

| Factor detected . | CD34+ cells BM . | CFU-GM– derived . | BFU-E– derived . | CFU-Meg– derived . | Stroma . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIP-1α | 2012 ± 477 | bsd4-150 | bsd | bsd | 350 ± 42 |

| MIP-1β | 1309 ± 317 | bsd | bsd | bsd | —4-151 |

| RANTES | 174 ± 29 | bsd | bsd | 2227 ± 431 | 472 ± 63 |

| IL-8 | 103 ± 21 | — | — | 823 ± 54 | 397 ± 45 |

| PF-4 | 130 ± 25 | bsd | bsd | 9597 ± 862 | bsd |

| MCP-1 | bsd | bsd | bsd | bsd | 4221 ± −889 |

Cells were cultured for 24 hours in serum-free medium at a concentration of 1 × 106/mL medium.

The sensitivities of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (pg/mL) were as follows: MIP-1α > 31, MIP-1β > 31, MCP-1 > 31, PF-4 > 10, IL-8 > 1.

A dash indicates not done.

Effect of high doses of growth factors on apoptosis and proliferation of CD34+kit+ cells (n = 4)

| Factor tested . | Effect on apoptosis5-150 . | Effect on proliferation5-151 . |

|---|---|---|

| (no factor) | No effect | No effect |

| KL | Inhibition | Stimulatory |

| FLT3L | Inhibition | Stimulatory |

| TPO | Inhibition | Stimulatory |

| IGF-1 | Inhibition | No effect |

| VEGF | No effect | No effect |

| FGF-2 | No effect | No effect |

| HGF | No effect | No effect |

| Factor tested . | Effect on apoptosis5-150 . | Effect on proliferation5-151 . |

|---|---|---|

| (no factor) | No effect | No effect |

| KL | Inhibition | Stimulatory |

| FLT3L | Inhibition | Stimulatory |

| TPO | Inhibition | Stimulatory |

| IGF-1 | Inhibition | No effect |

| VEGF | No effect | No effect |

| FGF-2 | No effect | No effect |

| HGF | No effect | No effect |

See footnote to Table 1 for abbreviations.

Percentage of apoptotic cells at day 4: (no factor) (34 ± 13%); KL (7 ± 3%); FLT3 ligand (12 ± 6%); TPO (7 ± 4%); IGF-1 (15 ± 7%); VEGF (37 ± 15%); FGF-2 (32 ± 19%); and HGF (34 ± 10%).

Determined by the presence of cell division and cell cluster formation.

We also observed that secretion of VEGF by CFU-GM–, BFU-E–, and CFU-Meg–derived cells was significantly higher (eg, up to 820 pg/mL by BFU-E–derived cells) than by CD34+ cells (20 pg/mL). In addition, while cells from erythroid and megakaryocytic lineages secreted high levels of TGF-β1, FGF-2 was secreted by CFU-Meg–derived cells and FLT3 ligand by CFU-GM–derived cells. These growth factors were also secreted by BM fibroblasts (Tables 3 and 4) at higher levels than by CD34+ cells. However, predictably, many of these factors were not detectable at the protein level in media conditioned by these cells (Table 3), although we detected mRNA for them (Table 2).

Further, we found that human CD34+ cells secrete various chemokines, such as MIP-1α, MIP-1β, RANTES, IL-8, and PF-4 (Table4). The potential biological significance of this secretion is intriguing, as endogenously secreted chemokines could attract other cells, stimulate angiogenesis, and regulate cell migration and adhesion.29,30 Some of the identified β-chemokines, such as MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and RANTES, could also interfere with the infectability of hematopoietic cells by R5 HIV.11,12,29 30

Furthermore, CFU-Meg–derived cells secreted RANTES, PF-4, and IL-8 at higher levels than CD34+ or stromal cells. MCP-1 was secreted only by BM fibroblasts, and we did not detect the presence of MCP-1, RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, or PF-4 in media conditioned by CFU-GM– and BFU-E–derived cells (Table 4).

Since normal human endothelial cells secrete several cytokines and growth factors,31 we evaluated whether the CFU-GM–, BFU-E–, and CFU-Meg–derived cells used in this study were contaminated by endothelial progenitors (AC133+and VEGF-R2+) and endothelial cells (AC133−and VEGF-R2+). By employing both surface-receptor analysis (AC133 and VEGF-R2 expression) and RT-PCR for expression of VEGF-R2 mRNA (data not shown), we excluded this possibility.

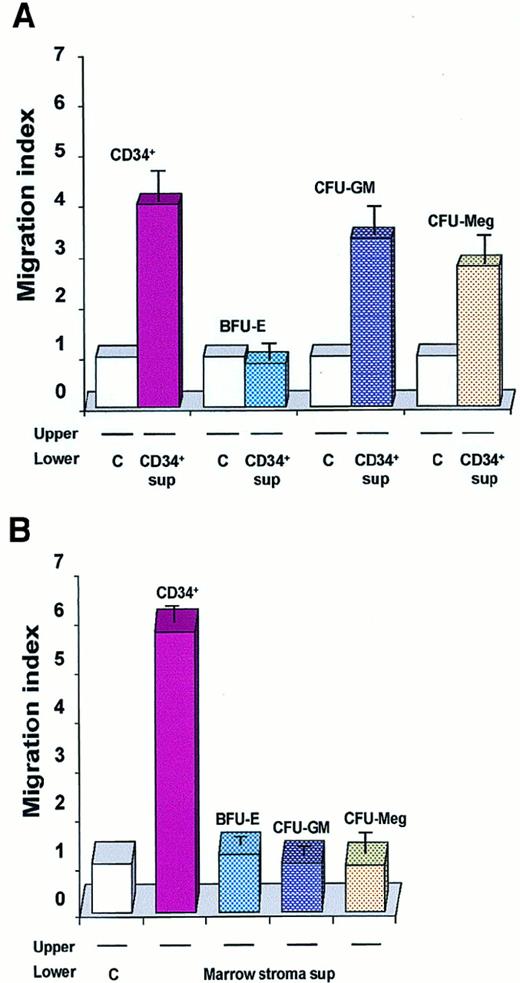

Media conditioned by CD34+ cells attract other CD34+ cells, myeloblasts, and megakaryocytes

To assess the biological significance of these regulators secreted by normal human BM CD34+ cells, we used transwell chemotaxis assays to examine whether conditioned media harvested from these cells attract other hematopoietic cells. To do this, we first evaluated the chemotactic potential of human BM MNCs toward media conditioned by CD34+ cells. Cells showing chemotaxis were collected, counted, and evaluated by FACS according to their FSC and SCC criteria. To our surprise, we found that normal human CD34+ cells secrete chemotactic factors that strongly attract primary human BM MNCs from the monocytic and granulocytic gates (Figure 4C,D).

Representative dot plots (n = 8) of BM MNCs that migrated in a chemotaxis assay to media conditioned by normal human CD34+cells.

Upper panel: dot-plot of cells that migrated to serum-free medium alone. Lower panel: dot-plot of cells that migrated to serum-free medium conditioned by CD34+ cells. (A and E) Dot plot of BM MNCs. (B and F) Dot plot of cells from the lymphocyte gate. (C and G) Dot plot of cells from the monocyte gate. (D and H) Dot plot of cells from the granulocyte gate.

Representative dot plots (n = 8) of BM MNCs that migrated in a chemotaxis assay to media conditioned by normal human CD34+cells.

Upper panel: dot-plot of cells that migrated to serum-free medium alone. Lower panel: dot-plot of cells that migrated to serum-free medium conditioned by CD34+ cells. (A and E) Dot plot of BM MNCs. (B and F) Dot plot of cells from the lymphocyte gate. (C and G) Dot plot of cells from the monocyte gate. (D and H) Dot plot of cells from the granulocyte gate.

When we extended these chemotaxis experiments to other precursors (CFU-GM–, CFU-Meg–, and BFU-E–derived cells), we found that conditioned media harvested from normal human CD34+ cells attracted normal myeloblasts and megakaryoblasts but not erythroblasts (Figure 5A). Contrary to our expectations, conditioned media harvested from normal CD34+cells were also able to attract other CD34+ cells freshly isolated from human BM (Figure 5A). This observation is intriguing as SDF-1, recognized as a strong chemo-attractant of human CD34+ cells,31-34 is not expressed in these cells (Table 2), suggesting that another potent, as yet undiscovered, chemo-attractant exists, and is present in media conditioned by CD34+ cells.

Chemotaxis of CD34+BM MNCs and normal human hematopoietic cells.

Data are presented as a migration index. The data are representative of 3 experiments yielding similar results. (A) Chemotaxis of freshly isolated CD34+ BM MNCs: day-6 BFU-E–derived; day-6 CFU-GM–derived; day-6 CFU-Meg–derived cells to media conditioned by CD34+ cells (CD34+ sup) or to control media (C). (B) Chemotaxis of normal human hematopoietic cells (CD34+ cells and BFU-E–, CFU-GM–, and CFU-Meg–derived cells) to media conditioned by cells from BM stroma or to a control medium.

Chemotaxis of CD34+BM MNCs and normal human hematopoietic cells.

Data are presented as a migration index. The data are representative of 3 experiments yielding similar results. (A) Chemotaxis of freshly isolated CD34+ BM MNCs: day-6 BFU-E–derived; day-6 CFU-GM–derived; day-6 CFU-Meg–derived cells to media conditioned by CD34+ cells (CD34+ sup) or to control media (C). (B) Chemotaxis of normal human hematopoietic cells (CD34+ cells and BFU-E–, CFU-GM–, and CFU-Meg–derived cells) to media conditioned by cells from BM stroma or to a control medium.

Finally, since many potential chemo-attractants are secreted by CFU-F–derived fibroblasts, we evaluated whether media conditioned by these cells attract normal human myeloblasts, megakaryoblasts, erythroblasts, and CD34+ cells. In contrast to media conditioned by CD34+ cells, we found that media conditioned by BM fibroblasts attracted CD34+ cells only (Figure 5B).

Media conditioned by CD34+ cells stimulate proliferation and inhibit apoptosis of CD34+ cells

Having detected in conditioned media harvested from normal CD34+ cells the presence of several factors that may potentially increase cell viability (KL, FLT3 ligand, TPO, and IGF-1) or decrease it (TGF-β1 and TGF-β2), we decided to determine which biological effect (stimulatory or inhibitory) would prevail when freshly isolated CD34+ cells were cultured in media conditioned by other CD34+ cells. To address this question, normal BM CD34+ cells were cultured for 7 days in medium conditioned (or not) by CD34+ cells. At day 7, the cells were counted and their viability was determined by 0.5% trypan blue exclusion tests; clonogenicity was evaluated in methylcellulose cultures. Activation of caspase-3 in these cells was studied by FACS by means of intracellular staining with monoclonal antibodies that recognize the activated form of caspase-3.

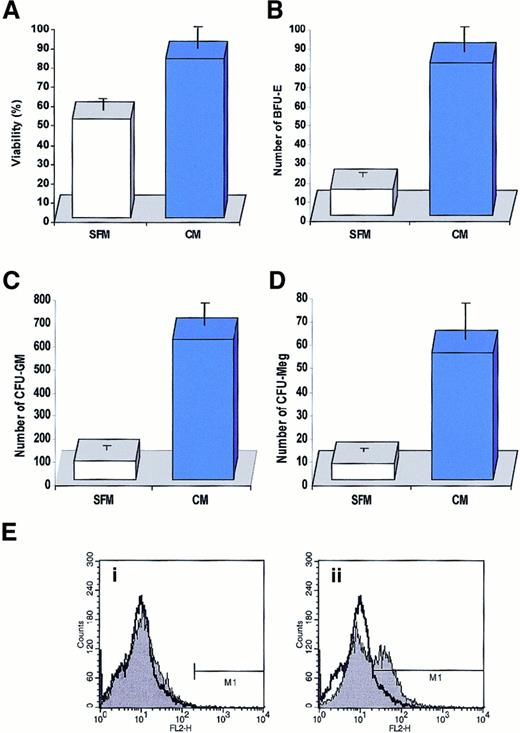

We found that conditioned media harvested from CD34+ cells slightly stimulated the proliferation of freshly isolated CD34+ cells cultured for 7 days (data not shown) and significantly improved their survival (Figure6A). We also found in methylcellulose replating experiments that more lineage-specific progenitor cells, such as BFU-E, CFU-GM, and CFU-Meg, retained their proliferative potential if they were cultured for 7 days in media conditioned by CD34+ cells (Figure 6B-D). Interestingly, this effect depended on the concentration of CD34+ cells employed as “target cells” in our assay. We found that if we cultured our target population of CD34+ cells at low concentration (1 × 105/mL), the protective effect of conditioned media harvested from CD34+ cells at 2 × 106/mL per 24 hours was more evident than if we cultured the target population of CD34+ cells at a concentration of 5 × 105/mL (data not shown). It is obvious that in the latter case CD34+ cells were able to enrich their culture medium much faster with endogenously secreted factors. To further demonstrate that biologically active factors are secreted by CD34+ cells, we cultured 2 sets of samples of CD34+ cells (5 × 105/mL) for 7 days in serum-free medium and every 24 hours gently spun down the cells in both sets. While the cells in the first set were always resuspended in fresh medium, the cells in the second set were resuspended in the “old” (ie, conditioned) medium. We found that the viability of cells cultured for 7 days in the old medium decreased by only 23% ± 6% compared with the cells that were resuspended every day in the fresh medium, which decreased by 58% ± 7%. Thus, these data show that CD34+ cells secrete factors that may improve their survival, at least under the culture conditions employed in this work.

Effect of medium conditioned by CD34+ cells on cell survival.

(A) Effect of media conditioned by human CD34+ cells (2 × 106/mL per 24 hours) on survival of freshly isolated CD34+ cells (105/mL). Cells were cultured for 7 days in media conditioned by CD34+ cells (CM) or in a control serum-free medium (SFM). Cell viability was evaluated by 0.5% trypan blue exclusion tests. The data are representative of 4 experiments yielding similar results. (B) (C) (D) Effect of a medium conditioned by human CD34+ cells on survival of clonogeneic progenitors in CD34+ cells. Cells were cultured for 7 days in media conditioned by CD34+cells (CM, solid bars) or in a control serum-free medium (CFM, open bars). After 7 days, cells were plated in methylcellulose medium and stimulated to grow erythroid (B), myeloid (C), and megakaryocytic (D) colonies. (E) Detection of activated capase-3 by intracellular staining with monoclonal antibody against activated form of this enzyme. Normal human BM-derived CD34+ cells were cultured for 72 hours in conditioned medium harvested from CD34+ cells (i) or serum-free medium (ii). Data are shown in comparison with the intracellular caspase-3 staining in freshly isolated CD34+cells. The experiment was repeated 4 times with similar results.

Effect of medium conditioned by CD34+ cells on cell survival.

(A) Effect of media conditioned by human CD34+ cells (2 × 106/mL per 24 hours) on survival of freshly isolated CD34+ cells (105/mL). Cells were cultured for 7 days in media conditioned by CD34+ cells (CM) or in a control serum-free medium (SFM). Cell viability was evaluated by 0.5% trypan blue exclusion tests. The data are representative of 4 experiments yielding similar results. (B) (C) (D) Effect of a medium conditioned by human CD34+ cells on survival of clonogeneic progenitors in CD34+ cells. Cells were cultured for 7 days in media conditioned by CD34+cells (CM, solid bars) or in a control serum-free medium (CFM, open bars). After 7 days, cells were plated in methylcellulose medium and stimulated to grow erythroid (B), myeloid (C), and megakaryocytic (D) colonies. (E) Detection of activated capase-3 by intracellular staining with monoclonal antibody against activated form of this enzyme. Normal human BM-derived CD34+ cells were cultured for 72 hours in conditioned medium harvested from CD34+ cells (i) or serum-free medium (ii). Data are shown in comparison with the intracellular caspase-3 staining in freshly isolated CD34+cells. The experiment was repeated 4 times with similar results.

To better demonstrate the effect of media conditioned by CD34+ cells in preventing the apoptosis of other CD34+ cells, we also examined activation of caspase-3 (using intracellular FACS staining) in CD34+ cells cultured in fresh medium vs medium conditioned by CD34+ cells. We found that after 72 hours, caspase-3 became activated in 36% ± 7% of CD34+ cells cultured in serum-free medium, compared with no activation in medium conditioned by CD34+ cells (Figure6E).

Survival and proliferation of human CD34+ cells is distinctly regulated by various endogenously secreted growth factors added in recombinant form

Having determined that normal human CD34+ cells endogenously secrete KL, FLT3 ligand, IGF-1, TPO, VEGF, FGF-2, and HGF, we set out to determine the effect these regulators have on apoptosis and/or proliferation of human CD34+ cells. To address this issue, we cultured human CD34+kit+ cells (isolated from BM MNCs by FACS to a purity greater than 98%) under serum-free conditions with each of the growth factors added exogenously and, after 72 hours, counted the total number of cells and the number of apoptotic cells in these cultures. We found that exogenously added rhKL, FLT3 ligand, TPO, and IGF-1, but not VEGF, FGF-2 and HGF, inhibited apoptosis in CD34+kit+ cells (Table 5). Moreover, as we expected, the presence of KL, FLT3 ligand, or TPO in a culture slightly stimulated the proliferation of CD34+kit+ cells. In contrast, exogenously added VEGF, FGF-2, and HGF had no such effect (Table 5).

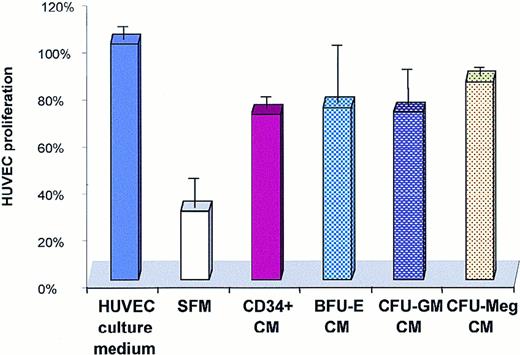

Media conditioned by CD34+ cells and CFU-GM–, CFU-Meg–, and BFU-E–derived cells stimulate proliferation of HUVECs

Using the ELISA assay, we detected the presence of the angiopoietic factors VEGF, FGF-2, HGF, and IL-8 in conditioned media harvested from human CD34+ cells. Similarly, VEGF was found in the conditioned media harvested from CFU-GM, CFU-Meg, and BFU-E cells (Table 3). To determine whether these media affect the biology of endothelial cells, we cultured HUVECs in serum-free media conditioned or not conditioned by human CD34+ cells and CFU-GM–, CFU-Meg–, or BFU-E–derived cells (Figure7). We found that media conditioned by all these cells increased the survival of HUVECs and stimulated their proliferation (Figure 7).

Effect of a medium conditioned by CD34+ cells on proliferation of HUVECs.

HUVECs were cultured for 4 days in a HUVEC culture medium, serum-free medium (SFM), or serum-free medium conditioned by CD34+cells or BFU-E–, CFU-GM–, and CFU-Meg–derived cells. The experiment was repeated 3 times with similar results.

Effect of a medium conditioned by CD34+ cells on proliferation of HUVECs.

HUVECs were cultured for 4 days in a HUVEC culture medium, serum-free medium (SFM), or serum-free medium conditioned by CD34+cells or BFU-E–, CFU-GM–, and CFU-Meg–derived cells. The experiment was repeated 3 times with similar results.

Discussion

The involvement of autocrine/paracrine regulatory axes has been proposed in the growth of many solid tumors35 and leukemias,36-39 as well as normal hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells.6-10,40-42 We and others have shown that normal human CD34+ cells express mRNA for several hematopoietic regulators (KL, FLT3 ligand, EPO, IL-1, and TGF-β1)6-10 and that perturbation of expression of mRNA for KL or FLT3 ligand by sequence-specific antisense oligomers8 or neutralization of TGF-β1 by monoclonal antibodies6 affects the formation of hematopoietic colonies. Together, these published data suggest that some stages of normal hematopoiesis are regulated by autocrine/paracrine axes.6-10 43

Advances in cell isolation and culture techniques have made it possible to obtain highly purified cells, such as human CD34+ cells, myeloblasts, megakaryoblasts, and erythroblasts, for research purposes.3,19 44 Moreover, sensitive ELISA immunoassays now permit detection of picogram levels of hematopoietic growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines. Hence, after finding that highly purified normal human CD34+ cells and early CFU-GM–, BFU-E–, CFU-Meg–, and CFU-F–derived cells express mRNA for various growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines, we went on to perform extensive studies to evaluate whether these factors are in fact secreted by these cells.

In this study, we reconfirmed that normal CD34+ cells express mRNA for KL, FLT3 ligand, IL-1, IL-8, and TGF-β16-9 and identified transcripts for 17 other growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines. We demonstrated the presence of mRNA for FGF-2, VEGF, HGF, IGF-1, TPO, IL-16, TNF-α, IFN-α, Fas-L, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, RANTES, MCP-3, MCP-4, IP-10, MDC, and PF-4 in CD34+ cells. However, mRNA for EPO and SDF-1 could not be demonstrated by us in contrast to others' reports.10,27More importantly, we demonstrated for the first time that CD34+ cells not only express transcripts for, but also secrete detectable amounts of VEGF, HGF, FGF-2, KL, FLT3 ligand, IGF-1, TPO, IL-16, TGF-β1, TGF-β2, RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, IL-8, and PF-4 proteins into culture media. These findings provide evidence of putative positive/negative autocrine/paracrine axes that could regulate the development of normal hematopoietic cells. Interestingly, we did not observe mRNA for either IL-3 or G-CSF in normal human CD34+ cells (Table 2), which is consistent with an observation first made by Jiang et al.36 Moreover, that group showed that, in contrast to normal progenitors, BCR-ABL+ CD34+ cells produce IL-3 and G-CSF endogenously and suggested that they play a role in the autocrine proliferation of early malignant chronic myeloid leukemia cells.36

To better understand the biological significance of our findings, we examined whether conditioned media harvested from CD34+cells promote proliferation and survival of freshly isolated CD34+ cells, chemo-attract other CD34+ cells or more mature CFU-GM–, BFU-E–, and CFU-Meg–derived cells, and stimulate the proliferation of endothelial cells (HUVECs). We found that conditioned media harvested from CD34+ cells stimulated proliferation slightly and inhibited apoptosis of freshly isolated BM CD34+ cells, a fact that could be explained by the presence of KL, FLT3 ligand, TPO, IGF-1, and IL-1 proteins in these media. Since CD34+ cells were also found to secrete inhibitors, such as TGF-β1, TGF-β2, and PF-4, as well as to express mRNA for TNF-α, IFN-α, and Fas-L, it appears that the effects of positive hematopoietic regulators present in these media predominated. Using antisense oligomers, we previously reported that perturbation of expression of receptors for KL and FLT3 ligand,8 but not VEGF, FGF-2, or HGF,20,45,46affects the proliferation and survival of human CD34+ cells and suggested that both KL and FLT3 ligand may operate as autocrine regulators in these cells.8 Secretion of KL by normal CD34+ cells has also been suggested recently by other investigators, who found that kitlow/−CD34+cells began to proliferate after transduction with kit cDNA, even when exogenous KL was absent from the culture medium.41 Here, in agreement with these observations, we show that KL and FLT3 ligand are secreted by normal human CD34+ cells and thus play an important role in the biology of these cells. Moreover, since human CD34+ cells were found to secrete TPO and express c-mpl,47,48 a putative role for c-mpl–TPO in autocrine regulation of CD34+ cells needs further investigation. Similarly, since human CD34+ cells express CD95 (Apo/Fas) and TNF receptors (TNF-Rs) (55 kd and 75 kd) (data not shown), and as we found that mRNAs for Fas-L and TNF-α are expressed in these cells, we suggest that 2 other negative regulatory axes (Fas-L–CD95 and TNF-α–TNF-R), in addition to the TGF-β1–TGF-β R axis,6,16 17 may operate at early stages of hematopoiesis.

We are aware, however, that the ELISA assays were performed on a population of CD34+ cells that remains heterogeneous even after purification, containing, in addition to hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells, endothelial,31,49,50stromal,51 and lymphoid52 progenitor cells. Nevertheless, our finding of many hematopoietic regulators detectable in conditioned media harvested from human CD34+cells may have important implications not only for understanding the biology of hematopoietic stem cells but also for therapeutic purposes. It has recently been postulated that human stem cells proliferate and self-renew if exposed to high concentrations of growth factors and, in contrast, differentiate at low concentrations.5 Thus, the presence of hematopoietic stimulators endogenously secreted by CD34+ cells at low concentrations, as shown by us, could explain the difficulty experienced in achieving ex vivo expansion of human hematopoietic stem cells.

The fact that media conditioned by CD34+ cells were found to attract other hematopoietic cells is intriguing. However, although CD34+ cells were shown to secrete many chemokines, SDF-1, which is known to be an important chemo-attractant of CD34+cells,31-34 was not expressed in these cells. Hence, we suggest that chemo-attractants for human CD34+ cells other than SDF-1 exist and are secreted by normal human CD34+cells. Currently, we are working on identifying these factors. We are also phenotyping lymphoid cells, which are attracted by human CD34+ cells, in an attempt to identify the subsets of lymphocytes that may co-regulate proliferation of hematopoietic cells.4

Finally, in our study, the stimulation of endothelial cells (HUVECs) by media conditioned by CD34+ cells correlated with the secretion of VEGF, FGF-2, HGF, and IL-8 proteins by CD34+cells, which indicates the existence of cross-talk between normal hematopoietic progenitors and endothelium.53-55Proliferation of HUVEC cells was also stimulated by conditioned media harvested from CFU-Meg–, BFU-E–, and CFU-GM–derived cells. Hence, we postulate here that, like leukemic cells,17,56-59 normal hematopoietic cells possess a mechanism allowing them to stimulate the proliferation of endothelium. We believe that this may be a common mechanism to secure vascularization and an appropriate supply of blood to the areas of intensive hematopoiesis.53 54

The secretion of various chemokines by normal human CD34+cells observed in this study is also intriguing and has important consequences for cell biology. In agreement with this, we recently reported that the β-chemokines RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β are endogenously secreted by CD34+ cells and megakaryoblasts,11,12 similarly to natural killer cells,60 and autoprotect them from infection by R5 HIV. Here, we report that human CD34+ cells secrete IL-16, which could possibly protect them from infection by X4 HIV.28Thus, our data collectively suggest that CD34+ cells could be autoprotected from infection by R5 and X4 HIV by means of endogenously secreted β-chemokines and IL-16, respectively.

Many growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines were also expressed and secreted by more differentiated cells and might potentially play an important role in the cross-talk between different subsets of hematopoietic cells.61 However, defining the precise role these factors play in CFU-GM, CFU-Meg, or BFU-E development will require more study. Interestingly, we also found that medium conditioned by CFU-F–derived fibroblasts attracts normal human CD34+ cells but does not attract the more differentiated cells, such as myeloblasts, megakaryoblasts, and erythroblasts. These observations suggest that the chemotaxis of hematopoietic cells to stroma is regulated developmentally and explains why only early CD34+ cells home to BM hematopoietic niches.1,3 One of the putative candidates for this effect is SDF-1 secreted by BM stromal cells.31-34

The endogenously secreted factors we describe (and presumably those as yet undiscovered) may play a key role in the biology of early hematopoietic cells in vivo. In vitro, where recombinant molecules are used, this effect will probably differ, especially when one considers that endogenously secreted factors are very often much more biologically effective than recombinant proteins.62 As an example, autocrine TGF-β1 secretion in human hematopoietic progenitors up-regulates bcl-2 expression and regulates the survival and differentiation of primitive proliferating hematopoietic progenitors by cell cycle–independent mechanisms,17whereas exogenously added TGF-β1 affects the cell cycle and inhibits proliferation of these cells.6,22 Hence, the proper biological combination of these various factors is necessary to provide stimulatory signals and gradients to the cells, and consequently various scenarios in which these mechanisms operate are possible.63,64 A full understanding of the precise role in normal hematopoiesis of the numerous endogenously secreted regulators we identified here will require more investigation. These regulators may serve to attract hematopoietic cells, modulate the expression of adhesion molecules on their surface, and thus regulate their adhesion and homing, stimulate the secretion of regulatory molecules by accessory cells,65 and/or influence survival of the cells and/or costimulate their proliferation.

Finally, it will be important to evaluate secretion of these factors by hematopoietic cells derived from the patients suffering from many and various hematological diseases, eg, cytopenias, myelodysplastic syndromes, and myeloproliferative disorders. When we develop a better understanding of intercellular cross-talk in normal and pathological states, we may target the various mechanisms regulating synthesis of these endogenous factors for new pharmacological approaches.

In conclusion, we provide the first evidence that normal human BM or PB CD34+ cells, myeloblasts, erythroblasts, and megakaryoblasts secrete numerous growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines that contribute to intercellular cross-talk networks and regulate various stages of hematopoiesis. We believe that our observations open a new area of investigation into hematopoiesis.

The authors thank Dr D. Cines (Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, University of Pennsylvania) for HUVECs, A. Dobrowsky and K. Esler for technical assistance, and Dr Mitch Weiss (CHOP, Philadelphia) for comments.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 HL61796-01 (M.Z.R.), the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society grant 64907-00 (M.Z.R.), and Canadian Blood Services R & D grant XE0004 (A.J.-W.).

M.M. and A.J.W. contributed equally to this work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Mariusz Z. Ratajczak, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, 405A Stellar Chance Labs, 422 Curie Blvd, Philadelphia PA 19104; e-mail: mariusz@mail.med.upenn.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal