Abstract

Concurrent infections in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection stimulate HIV replication. Chemokine receptors CXCR4 and CCR5 can act as HIV coreceptors. The authors hypothesized that concurrent infection increases the HIV load through up-regulation of CXCR4 and CCR5. Using experimental endotoxemia as a model of infection, changes in HIV coreceptor expression were assessed in 8 subjects injected with lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 4 ng/kg). The expression of CXCR4 and CCR5 on CD4+ T cells was increased 2- to 4-fold, 4 to 6 hours after LPS injection. In whole blood in vitro, LPS induced a time- and dose-dependent increase in the expression of CXCR4 and CCR5 on CD4+ T cells. Similar changes were observed after stimulation with cell wall components ofMycobacterium tuberculosis (lipoarabinnomannan) orStaphylococcus aureus (lipoteichoic acid), or with staphylococcal enterotoxin B. LPS increased viral infectivity of CD4-enriched peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) with a T-tropic HIV strain. In contrast, M-tropic virus infectivity was reduced, possibly because of elevated levels of the CCR5 ligand cytokines RANTES and MIP-1β. LPS-stimulated up-regulation of CXCR4 and CCR5 in vitro was inhibited by anti-TNF and anti-IFNγ. Incubation with recombinant TNF or IFNγ mimicked the LPS effect. Anti–interleukin 10 (anti–IL-10) reduced CCR5 expression, without influencing CXCR4. In accordance, rIL-10 induced up-regulation of CCR5, but not of CXCR4. Intercurrent infections during HIV infection may up-regulate CXCR4 and CCR5 on CD4+ T cells, at least in part via the action of cytokines. Such infections may favor selectivity of HIV for CD4+ T cells expressing CXCR4.

Introduction

During the course of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, concurrent infections stimulate viral replication. Replication of HIV-1 is enhanced in HIV-infected patients with active tuberculosis, returning to baseline after tuberculostatic treatment.1,2 Also, a number of other infectious diseases often encountered during the course of HIV infection has been reported to accelerate HIV replication.3-6 Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), the major cell wall component of gram-negative bacteria, and staphylococcal antigens stimulate HIV expression in vitro.7 8 Together, these data suggest that concurrent infection offers an advantage to HIV-1 to infect cells and to replicate.

Chemokines are chemotactic proteins that direct leukocytes to the site of inflammation. Chemokine receptors CXCR4 and CCR5 can act as HIV coreceptors, together with CD4, and are essential for viral entry into cells.9-13 Individuals with a homozygous defect in CCR5 are less susceptible to HIV-1 infection, suggesting a key role for this receptor in HIV-1 pathogenesis.14,15 Macrophage (M)-tropic HIV-1 isolates use CCR5 as coreceptor early in the course of HIV infection, whereas T-cell tropic viruses use CXCR4 for entry into CD4+ T cells, typically in a later stage of infection. An expansion of receptor use to include CXCR4 has been associated with a sharp decline in the number of peripheral CD4+ T cells,16 indicating that disease progression can correlate with HIV coreceptor type.

Recently, a number of studies have indicated that an increase in CXCR4 and CCR5 expression is associated with an enhanced entry of HIV-1 into cells of the immune system.17-21 We hypothesized that during concurrent infection, invading microorganisms or their antigens up-regulate HIV coreceptors on CD4+ T cells, resulting in an increase in HIV replication. To test this hypothesis, we studied the expression of CXCR4 and CCR5 on CD4+ T cells in the well-defined model of human endotoxemia22 and after in vitro incubation with a lipid glycoprotein cell wall component ofMycobacterium tuberculosis (lipoarabinomannam, LAM), a cell wall component of Staphylococcus aureus (lipoteichoic acid, LTA) and staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB). The association of HIV coreceptor expression and HIV infectivity was examined by measuring replication of T- and M-tropic viruses in LPS-stimulated CD4+-enriched peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Because cytokines influence HIV-1 replication,23 24 we also determined the role of important proinflammatory and antiinflammatory cytokines with the use of neutralizing antibodies and recombinant products.

Patients, materials, and methods

In vivo study

Eight healthy HIV-negative male subjects, age 23 ± 1 years (mean SE), were admitted to the clinical research unit of the Academic Medical Center, after documentation of good health by history, physical examination, hematologic and biochemical screening, chest radiographs, and electrocardiogram. The participants did not smoke, used no medication, and had no febrile illness within 2 weeks before start of the study. The study was approved by the institutional research and ethics committees and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before enrollment. All volunteers received a bolus intravenous injection of LPS (from Escherichia coli, lot G, US Pharmacopeial Convention, Rockville, MD) at a dose of 4 ng/kg body weight. Venous blood samples were obtained directly before the injection of LPS and 1, 2, 4, 6, and 24 hours thereafter. Blood was collected in heparin-containing vials and processed for flow cytometry immediately.

Flow cytometry

Heparinized whole blood was prepared for fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis as follows. Erythrocytes in 4.5 mL whole blood were lysed with bicarbonate-buffered ammonium chloride solution (pH 7.4). Leukocytes were recovered after centrifugation at 1450 rpm for 5 minutes and counted. The 1 × 106 cells were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline containing EDTA 100 mmol/L, sodium azide 0.1%, and bovine serum albumin 5% (cPBS) and placed on ice. Triple staining was obtained by incubation for 1 hour with direct-labeled antibodies CD3-PE, CD4-Cy (both from Coulter Immunotech, Marseille, France) and either CXCR4-FITC or CCR5-FITC (R&D Systems, Abingdon, United Kingdom). Nonspecific staining was controlled for by incubation of cells with FITC-labeled mouse IgG2 (Coulter Immunotech). Cells were then washed twice in ice-cold cPBS and resuspended for flow cytofluorometric analysis (Calibrite; Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA). At least 10 000 lymphocytes were counted. Data on mean cell fluorescence intensity (MCF) are represented as the difference between MCF intensities of specifically stained cells and nonspecifically stained cells. Data on the number of positive cells were obtained by setting a quadrant marker for nonspecific staining.

In vitro studies

For each experiment, blood was collected from 6 healthy subjects using a sterile collecting system consisting of a butterfly needle connected to a syringe (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) and incubated at 37°C for 8 hours. Anticoagulation was obtained using heparin (Leo Pharmaceutical Products, Weesp, The Netherlands; final concentration 10 U/mL blood). Whole blood was added to sterile polypropylene tubes and diluted 1:1 with RPMI 1640 (Bio Whittaker, Verviers, Belgium). LPS (from E coli serotype 0111: B4; Sigma, St Louis, MO) was added for the time course (10 ng/mL) and dose-response study. In separate experiments, LAM (mannose-capped, isolated and prepared from M tuberculosis strain H37Rv), kindly provided by J. T. Belisle (Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, under National Institutes of Health Contract NO1-A1-75320), LTA or SEB (both from Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO) were added at a concentration of 1 μg/mL. Whole blood was also stimulated with LPS (10 ng/mL) in the presence of a neutralizing mouse antihuman tumor necrosis factor (TNF) monoclonal antibody (mAb, MAK 195F,25 kindly provided by Knoll, Ludwigshafen, Germany), a neutralizing mouse antihuman interferon-γ monoclonal antibody (IFNγ mAb), a neutralizing mouse antihuman interleukin 10 (IL-10) mAb (both R&D systems), or an isotype-matched mouse IgG (Central Laboratory of the Netherlands Red Cross Blood Transfusion Service [CLB], Amsterdam, The Netherlands). The concentration of all antibodies was 10 μg/mL. Whole blood was also incubated with recombinant (r) TNF (Knoll), rIFNγ, or rIL-10 (both CLB, all 10 ng/mL). In addition, CD4+-enriched PBMCs were stimulated with PHA for 6 days, after LPS (10 ng/mL) was either added or omitted for 24 hours. FACS analysis was performed in whole blood and PBMCs as described above.

Viral TCID50 determination and in vitro HIV-1 infection

Viral stocks grown on PBMCs were assayed for their tissue culture infectious dose 50% per milliliter (TCID50) values on CD4+-enriched lymphocytes isolated from fresh buffy coats by standard Ficoll-Hypaque density centrifugation. PBMCs were activated with 5 μg/mL PHA (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO) and cultured in RPMI media containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Bio Whittaker), penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 U/mL) with 100 U/mL IL-2 (Chiron, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). On day 4 of culture, the cells underwent a CD4+ enrichment by incubating with CD8 immunomagnetic beads (Dynal) and separating out the CD8+ lymphocytes. CD4+-enriched lymphocytes were plated at 2 × 105 cells per well in 96-well plates with 5-fold serial dilutions of the virus. The wells were fed on day 7 with fresh media and scored on day 14 for p24 levels and the number of positive wells identified. This figure was used to determine the TCID50 value for each virus. For the HIV-1 in vitro infectivity assay, CD4+-enriched lymphocytes were generated as described above. On day of infection, the CD4+-enriched cells were treated either with or without LPS (100 ng/mL) and cultured for 8 hours at 37°C, after which a T-tropic molecular cloned virus (LAI) and an M-tropic molecular cloned virus (SF162) were used to infect the cells. Infections were performed using 4-fold limiting dilutions of the virus, starting at 240 TCID50 down to 1 TCID50. After a 2-hour incubation period, the cells were spun and washed 3 times and fed with fresh RPMI media containing IL-2. The cultures were carried for 10 days and fed with fresh IL-2 containing media on days 4, 7, and 10. Viral replication was monitored on day 10 by the use of a standard p24 antigen enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as previously described.26

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β were measured with ELISA (all from R&D Systems) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. The detection limits of assays were 31.5 (MIP-1α, RANTES) and 15.6 pg/mL (MIP-1β).

Statistical analysis

All values are given as means ± SEM. In vivo data were analyzed by 1-way analysis of variance. Data of in vitro stimulations of whole blood and end-point viral dilutions required to establish infection of CD4+-enriched lymphocytes in vitro were analyzed using the Wilcoxon test. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

HIV coreceptor expression on circulating CD4+ T cells during human endotoxemia

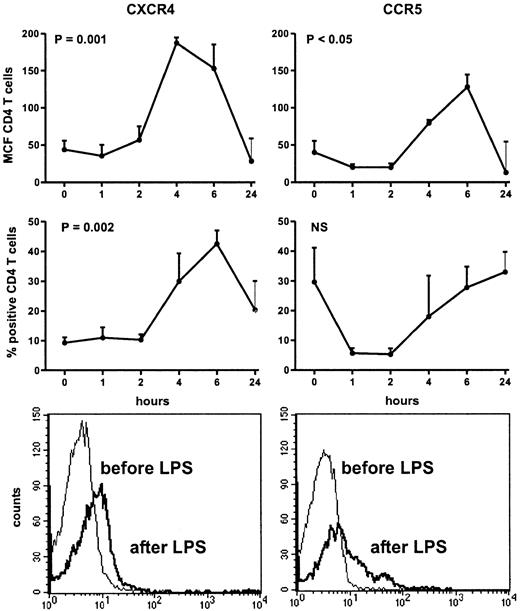

Injection of LPS was associated with transient influenza-like symptoms, including headache, chills, vomiting, myalgia, and fever (peak temperatures: 38.6°C ± 0.3°C). Injection of LPS induced a decrease in the number of lymphocytes (from 1.6 ± 0.1 to 0.3 ± 0.0 × 109/L at 4 hours, P = .048). The fraction of CD4+ T cells decreased from 41.1 ± 3.9% to 28.4 ± 5.7% at 4 hours (P = .05). Intravenous LPS induced an increase in the expression of CXCR4 on circulating CD4+ T cells, peaking after 4 hours (MCF: from 43.8 ± 11.7 at baseline to 187.2 ± 32.1; P = .001), and returning to the initial level of expression after 24 hours (Figure1). In addition, the fraction of CD4+ T cells expressing CXCR4 also increased significantly, peaking after 6 hours (from 9.3% ± 1.8% at baseline to 42.6% ± 9.7%; P = .002). LPS elicited an up-regulation of CCR5 on circulating CD4+ T cells (MCF: from 40.1 ± 15.2 to 79.4 ± 16.5 at 6 hours;P = .01), returning to baseline after 24 hours. In contrast, the fraction of CCR5-positive CD4+ T cells did not change after injection with LPS. To determine whether the increase in CD4+ T cells positive for CXCR4 or CCR5 was not due to a relative loss of CD4+ T cells negative for CXCR4 or CCR5 from the circulation during endotoxemia, we analyzed the MCF on HIV-coreceptor–positive CD4+ T cells before and after LPS administration. LPS resulted in an increase in the MCF of CXCR4 on CXCR4-positive T cells from 115.2 ± 12.2 at baseline to 325.4 ± 13.1 at 6 hours. The MCF of CCR5 on CCR5 positive CD4+ T cells showed an increase 6 hours after LPS injection (from 91.9 ± 13.8 to 232.2 ± 32.3). MCF of both HIV coreceptors returned to baseline at 24 hours.

Up-regulation of CD4+ T-cell surface CXCR4 and CCR5 after intravenous injection of LPS (4 ng/kg) into 8 subjects.

Data expressed as mean (SE) difference between specific and nonspecific mean cell fluorescence (MCF) and as fraction of positive CD4+ T cells. Lower panels are histograms showing the mean channel fluorescence of CD4+ T cells positive for CXCR4 or CCR5 in a representative volunteer before and 6 hours after receiving LPS.

Up-regulation of CD4+ T-cell surface CXCR4 and CCR5 after intravenous injection of LPS (4 ng/kg) into 8 subjects.

Data expressed as mean (SE) difference between specific and nonspecific mean cell fluorescence (MCF) and as fraction of positive CD4+ T cells. Lower panels are histograms showing the mean channel fluorescence of CD4+ T cells positive for CXCR4 or CCR5 in a representative volunteer before and 6 hours after receiving LPS.

HIV coreceptor expression on CD4+ T cells after whole blood stimulation with (myco)bacterial agents

Having established that LPS causes an increase in the expression of CXCR4 and CCR5 on circulating CD4+ T cells, we performed a dose response and time course study of this effect in whole blood in vitro (Figure 2). Both HIV coreceptors were up-regulated after 8-hour stimulation with LPS, which lasted for 24 hours (CXCR4) or even 48 hours (CCR5). Because the in vivo effect of LPS was present at 6 hours, we chose to perform additional experiments with the 8-hour incubation period. A dose of 10 ng/mL induced significant up-regulation of both receptors. When higher doses were used, no additional effect was seen (Figure 2). Next, we sought to determine whether other bacterial products also up-regulate HIV coreceptors. For this purpose whole blood was incubated with LAM (a cell wall component of M tuberculosis), LTA (a cell wall component of S aureus) or SEB (a superantigen produced by S aureus). All 3 agents induced an up-regulation of CXCR4 and CCR5 on CD4+ T cells (Figure3).

Up-regulation of the fraction of CD4+ T cells expressing CXCR4 and CCR5 after stimulation with LPS.

Upper panels: whole blood was stimulated for 8 hours with different concentrations of LPS. Lower panels: whole blood was stimulated with LPS (10 ng/mL) for different periods.

Up-regulation of the fraction of CD4+ T cells expressing CXCR4 and CCR5 after stimulation with LPS.

Upper panels: whole blood was stimulated for 8 hours with different concentrations of LPS. Lower panels: whole blood was stimulated with LPS (10 ng/mL) for different periods.

Up-regulation of CD4+ T-cell surface CXCR4 and CCR5 after whole blood stimulation with 1 g/mL of LAM, LTA, or SEB for 8 hours.

*P < .05 compared with incubation of whole blood with medium (RPMI) alone. Before: expression before stimulation.

Up-regulation of CD4+ T-cell surface CXCR4 and CCR5 after whole blood stimulation with 1 g/mL of LAM, LTA, or SEB for 8 hours.

*P < .05 compared with incubation of whole blood with medium (RPMI) alone. Before: expression before stimulation.

HIV coreceptor expression and HIV replication in peripheral blood mononuclear cells

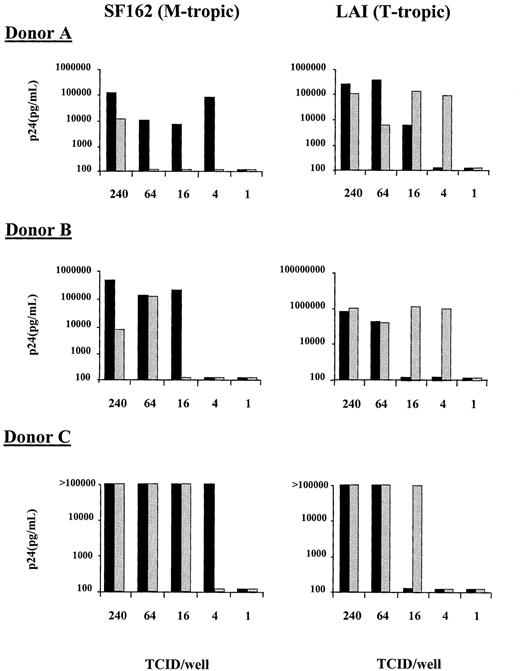

To determine whether HIV coreceptor up-regulation on CD4+ T cells correlates with HIV-1 replication, an in vitro system was developed with CD4+-enriched PBMCs. As in whole blood, LPS induced an increase in the fraction of CD4+cells expressing CXCR4 (from 20.9% at baseline to 49.9% after addition of LPS. Control: 22.3%) and CCR5 (from 9.6% at baseline to 37.8% after addition of LPS. Control: 14.2%; results from one representative experiment of 3 separate experiments). Infectivity of LPS-treated and nontreated CD4+-enriched PBMCs was determined using both the T-tropic (LAI) and M-tropic (SF162) molecular cloned viruses at limiting dilutions of infectivity and determining viral p24 production on day 10 of culture. Because the virus was washed out 2 hours after infection, our assay monitors the infectability of CD4+ cells during this period. With the T-tropic virus, an increase in the infectivity of the CD4+-enriched population was observed in the presence of LPS with a lower TCID50required to establish infection than in cultures to which no LPS was added (Figure 4). This increase in T-tropic HIV infectivity coincided with the enhancement of CXCR4 cell surface expression. In contrast, the M-tropic virus (SF162) showed an increase in the level of virus required to establish infection on the LPS-treated CD4+-enriched cells in comparison to cells that were not treated with LPS (Figure 4). This decrease in M-tropic infectivity was despite the increase in CCR5 cell surface expression. These results were reproduced in a total of 4 experiments in 3 different donors; for donor C the experiment was performed twice with similar results. Comparison of end-point viral dilutions required to establish infection of CD4-enriched PBMCs in the presence or absence of LPS, revealed an increased infectivity with T-tropic virus in the presence of LPS, with a concurrently decreased infectivity with M-tropic virus (both P = .011 for the difference between with or without LPS). Because it has been previously shown that LPS-treated macrophages can secrete elevated levels of chemokines, we wished to determine whether an enhancement in the secretion of RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β could explain the reduction in M-tropic viral infectivity. The levels of these chemokines were measured in supernatant of LPS-stimulated and nonstimulated CD4+-enriched lymphocytes. LPS induced an increase in the concentration of MIP-1β (14.6 vs 6.8 ng/mL in non-LPS stimulated cells) and RANTES (3322 vs 1661 pg/mL ml in non-LPS stimulated cells) but not of MIP-1α.

Infectivity of CD4+-enriched PBMCs with an M-tropic (SF162, left panels) and a T-tropic (LAI, right panels) virus.

PBMCs were treated for 8 hours without LPS (black bars) or with 100 ng/mL LPS (shaded bars) before being infected for 2 hours with 4-fold limiting dilutions of virus. After infection the cells were washed and cultured for an additional 10 days and viral infection was monitored by p24 production. Results of experiments with cells from 3 different donors are shown.

Infectivity of CD4+-enriched PBMCs with an M-tropic (SF162, left panels) and a T-tropic (LAI, right panels) virus.

PBMCs were treated for 8 hours without LPS (black bars) or with 100 ng/mL LPS (shaded bars) before being infected for 2 hours with 4-fold limiting dilutions of virus. After infection the cells were washed and cultured for an additional 10 days and viral infection was monitored by p24 production. Results of experiments with cells from 3 different donors are shown.

Role of cytokines in HIV coreceptor up-regulation on CD4+ T cells

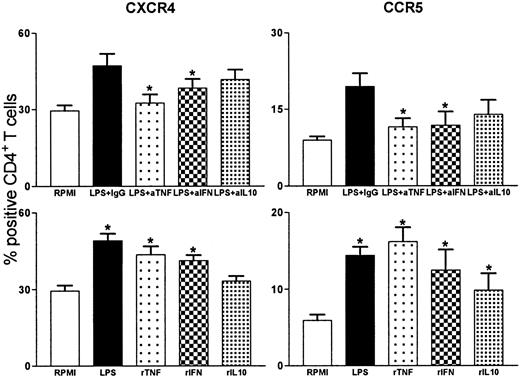

Both intercurrent infections and experimental endotoxemia result in an enhanced cytokine production. We studied the role of TNF, IFNγ, and IL-10 in the LPS-induced effects on HIV coreceptor expression (Figure 5). Therefore, whole blood was incubated with LPS in the presence of an irrelevant antibody, or a neutralizing antibody against either TNF, IFNγ, or IL-10. The LPS-induced up-regulation of the fraction of CD4+ T cells positive for CXCR4 was partially inhibited by anti-TNF and by anti-IFNγ (P = .028 versus incubation with LPS and an irrelevant antibody for both). Anti–IL-10 did not influence the expression of CXCR4. Similarly, the LPS-induced up-regulation of CCR5 expression was partially inhibited by anti-TNF and by anti-IFNγ, although these effects were more modest than for CXCR4 (P = .028 and P = .046, respectively, vs incubation with LPS and an irrelevant antibody). Anti–IL-10 tended to reduce the LPS effect. To further examine the role of cytokines in the absence of LPS stimulation, whole blood was incubated with either rTNF, rIFNγ, or rIL-10. In accordance with the inhibiting effect of anti-TNF and anti-IFNγ, expression of CXCR4 was up-regulated by rTNF or rIFNγ (P = .03 and P = .021, respectively, vs RPMI), whereas rIL-10 had no effect on CXCR4. Recombinant TNF or rIFNγ induced expression of CCR5 on CD4+ T cells to a lesser extent (P = .03 vs RPMI for both). In contrast to the absence of an IL-10 effect on CXCR4, rIL-10 up-regulated CCR5 on CD4+ T cells (P = .021 compared with RPMI).

Role of TNF, IFN, and IL-10 in LPS effects on CXCR4 and CCR5 expression on CD4+ T cells.

Whole blood was incubated with LPS (10 ng/mL) and cytokine or control (10 μg/mL) mAbs or recombinant cytokines (10 ng/mL) for 8 hours. Upper panels: effect of anti-TNF, anti-IFNγ, and anti–IL-10 on LPS-induced effects. *P < .05 compared with LPS+IgG (irrelevant control). Lower panels: effects of recombinant TNF, IFNγ, and IL-10. Data represent the fraction of CD4+ T cells that stained positive for either CXCR4 or CCR5. Similar results were obtained for either CXCR4 or CCR5. *P < .05 compared with RPMI.

Role of TNF, IFN, and IL-10 in LPS effects on CXCR4 and CCR5 expression on CD4+ T cells.

Whole blood was incubated with LPS (10 ng/mL) and cytokine or control (10 μg/mL) mAbs or recombinant cytokines (10 ng/mL) for 8 hours. Upper panels: effect of anti-TNF, anti-IFNγ, and anti–IL-10 on LPS-induced effects. *P < .05 compared with LPS+IgG (irrelevant control). Lower panels: effects of recombinant TNF, IFNγ, and IL-10. Data represent the fraction of CD4+ T cells that stained positive for either CXCR4 or CCR5. Similar results were obtained for either CXCR4 or CCR5. *P < .05 compared with RPMI.

Discussion

Concurrent infections in patients with HIV are associated with an increase in HIV replication3-6 and an enhanced susceptibility of immune cells for HIV infection.27 The chemokine receptors CXCR4 and CCR5 serve as coreceptors for HIV entry in CD4+ T cells. We used the model of intravenous LPS administration to healthy subjects to test the hypothesis that intercurrent febrile diseases may result in enhanced HIV replication through up-regulation of HIV coreceptors on circulating CD4+ T cells. Indeed, we found that during human endotoxemia, both the surface expression of CXCR4 and CCR5 per CD4+ T cell, as well as the fraction of CD4+ T cells expressing CXCR4, increased in peripheral blood. Stimulations of whole blood in vitro with antigens derived from M tuberculosis and S aureus induced similar changes in CXCR4 and CCR5 expression on CD4+ T cells. The heightened expression of CXCR4 correlated with an increase in the infectability of CD4+-enriched PBMCs with a T-tropic HIV-1 molecular cloned virus in vitro. In contrast, CCR5 surface expression did not result in an increased HIV infectability pattern but rather was associated with a decrease in replication of an M-tropic HIV-1 strain. Therefore, pathogens commonly found in HIV-infected patients may increase viral burden in blood by up-regulation of CXCR4. Moreover, intercurrent infections may contribute to the selection of CXCR4-using viruses during the course of disease progression.

The human endotoxemia model has some limitations. Intravenous injection of LPS induces a short-lasting febrile illness and an associated transient inflammatory response. In addition, the model uses the circulation as the body compartment to which the stimulus is administered and in which the responses are measured. Hence, in this study the up-regulation of HIV coreceptors was transient, just like the experimentally induced illness, and HIV coreceptor expression was only measured on CD4+ T cells derived from peripheral blood, the body compartment that was challenged with LPS. Presumably, similar changes in HIV coreceptor expression can be observed for longer periods and in other compartments, when clinical diseases are studied. Of special interest is the finding that macrophages may act as a reservoir for HIV during concurrent infections.28 Moreover, M avium, a pathogen commonly found in HIV patients, has been found to increase CCR5 expression and stimulate HIV production within macrophages.20

The effect of LPS on HIV coreceptors in vivo was most evident for CXCR4. This is in agreement with HIV coreceptor expression on macrophages after LPS stimulation.29 CXCR4 expression correlated with infectability of PBMCs with T-tropic strains, thereby supporting the idea that concurrent infections increase CXCR4 expression and subsequent HIV replication. In contrast, CCR5 expression did not correlate with an increase in replication of an M-tropic HIV strain. It has been shown that LPS induces production of CC-chemokines that inhibit HIV replication in T lymphocytes in vitro.30In accordance, the LPS stimulation of CD4+-enriched cells resulted in the higher production of RANTES and MIP-1. Also, during LPS-induced human endotoxemia, production of CC-chemokines is known to be enhanced.31 Hence, the net effect of LPS or other bacterial products on CCR5 expression and production of CCR5 blocking ligands in vivo remains to be determined. The HIV isolates associated with viral transmission and found early after infection are predominantly those which utilize the CCR5 coreceptor. In patients with an advanced stage of disease, a switch in receptor use from CCR5 to CXCR4 is often observed,16 suggesting that not only the extent of expression but also the type of HIV coreceptor modulates the course of HIV infection. Antigens from microorganisms often causing disease during an HIV infection heighten the susceptibility of macrophages to T-tropic HIV-1 in vitro.29 It has been proposed that a more favorable environment for T-tropic HIV-1 may result in viral transition of M-tropic to T-tropic HIV-1 phenotype, associated with disease progression.29 Indeed, because T-tropic but not M-tropic replication was associated with enhanced HIV coreceptor expression, bacterial antigens may be involved in the emergence of X4 and R5 × 4 variants.

It should be noted that we did not directly test our hypothesis that endotoxemia increases the susceptibility of CD4+ T cells to HIV infection. For this, HIV infectability of CD4+ T cells obtained before and 4 to 6 hours after endotoxin injection should have been determined. Such studies are difficult to perform, however, considering the fluctuation in CD4 counts after LPS treatment, and the fact that the cells would need to go through multiple processing steps (unlike with FACS analysis), during which CC chemokine and chemokine receptor patterns may alter, thereby obscuring the true in vivo picture. Nonetheless, these studies could provide further support for our hypothesis.

The precise mechanism for the observed up-regulation is unknown. Presumably, immune activation and subsequent cytokine secretion modulate HIV disease.23 TNF is reported to stimulate HIV expression in cell cultures,32-34 as well as in specific T-cell lines,35,36 and during concurrent infection.24 IFNγ induced CCR5 expression in a monocytic cell line, resulting in enhanced HIV entry.18 Moreover, it was found that anti-IFNγ or anti-TNF can block HIV production in IL-2 stimulated PBMCs in vitro.37 This points toward an important role for these proinflammatory cytokines in HIV expression. In this study, LPS-induced up-regulation of CXCR4 and CCR5 on CD4+ T cells was attenuated by anti-TNF and anti-IFNγ. Furthermore, rTNF and rIFNγ increased the fraction of CD4+ T cells expressing CXCR4 and CCR5. Overall, cytokine modulation of CXCR4 expression was more evident than of CCR5. Taken together, these data indicate that TNF and IFNγ may induce HIV expression through up-regulation of HIV coreceptors.

IL-10 is the most important antiinflammatory cytokine produced in the endotoxemia model.38 It has been reported that IL-10 enhances CCR5, but not CXCR4 expression on monocytes, correlating with an increase in HIV expression.17 Also in a T cell line, IL-10 synergized with TNF in enhancing HIV transcription.39 We examined the effect of anti–IL-10 on LPS-induced HIV coreceptor expression. Similar to the effect on monocytes, IL-10 influenced CCR5, but not CXCR4 on CD4+ T cells, ie, rIL-10 up-regulated CCR5 expression, whereas anti–IL-10 attenuated LPS-induced CCR5 up-regulation. It is speculative why IL-10 only exerts effect on CCR5. Considering the important role of IL-10 in mucosal diseases,40 it was suggested that IL-10 maintains CCR5 expression in mucosal tissues, facilitating primary HIV infection.17

In summary, (myco)bacterial antigens increased the expression of CXCR4 and CCR5 on circulating CD4+ T cells in humans and in whole blood through direct antigenic stimulation of CXCR4 and CCR5 on CD4+ T cells, as well as indirect stimulation of these receptors via cytokines. Expression of CXCR4 correlated with an increase in T-tropic HIV replication. Expression of CCR5 did not correlate with M-tropic replication, possibly because of the production of blocking CC chemokines by bacterial products. Therefore, concurrent infections during the course of an HIV infection may induce a favorable environment for T-tropic viral strains. HIV coreceptors, considered targets for HIV therapy,41 may be important determinants of the course of an HIV infection. Close surveillance and aggressive treatment of intercurrent disease in HIV-infected patients is implicated. For some pathogens, adequate antibiotic prophylaxis may reduce the HIV load.

Acknowledgment

We thank Moustapha Chalaby for excellent technical assistance.

Supported by grants from the “Mr. Willem Bakhuys Roozeboom” Foundation to N.P.J. and the Royal Dutch Academy of Arts and Sciences to W.A.P. and T.v.d.P.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Tom van der Poll, Laboratory of Experimental Medicine, Room G2-132, Academic Medical Center, Meibergdreef 9, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands; e-mail: t.vanderpoll@amc.uva.nl.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal