Abstract

The t(12;21)(p13;q22) chromosomal translocation is the most frequent illegitimate gene recombination in a pediatric cancer and occurs in approximately 25% of common acute lymphoblastic leukemia (cALL) cases. This rearrangement results in the in frame fusion of the 5′-region of the ETS-related gene, TEL(ETV6), to almost the entire acute myeloid leukemia 1 (AML1) (also called CBFA2 orPEBP2AB1) locus and expression of the TEL-AML1 chimeric protein. Although AML1 stimulates transcription, TEL-AML1 functions as a repressor of some AML1 target genes. In contrast to the wild type AML1 protein, both TEL and TEL-AML1 interact with N-CoR, a component of the nuclear receptor corepressor complex with histone deacetylase activity. The interaction between TEL and N-CoR requires the central region of TEL, which is retained in TEL-AML1, and TEL lacking this domain is impaired in transcriptional repression. Taken together, our results suggest that TEL-AML1 may contribute to leukemogenesis by recruiting N-CoR to AML1 target genes and thus imposing an altered pattern of their expression.

Introduction

Chromosomal translocations involving either the acute myeloid leukemia 1 (AML1) or TEL gene constitute some of the most frequently observed genetic aberrations in a variety of different myeloid and lymphoid leukaemias.1,2The AML1 gene, which encodes a transcription factor with a DNA-binding domain (DBD) related to Drosophila runt, was first identified through its fusion with theETO gene in t(8;21)(q22;q22) associated with acute myeloid leukemia (AML).3,4 The TEL gene, on the other hand, encodes an ETS family transcription factor identified by its fusion with the PDGFRB locus in cases of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CML) with t(5;12)(q33;p13).5Subsequently, in a variety of hemopoietic neoplasms TEL has been found rearranged with a number of different genes6including AML1.7,8 The t(12;21)(p13;q22)–associated TEL-AML1 fusion protein retains the so-called pointed domain (PD), which is responsible for mediating oligomerization of TEL9 and all known functional regions of AML1.10

AML1 is required for expression of genes whose products are associated with blood cell development.11,12 In contrast to AML1, the transiently expressed TEL-AML1 protein repressed the activities of reporter constructs driven by regulatory regions derived from hemopoiesis-specific genes including the lymphoid-specificTCRβ enhancer13 and the IL3promoter.14 Recent results, which have also shown that the wild type TEL protein can bind DNA15 and/or exert transcriptional repression,16-18 lend support to the notion that the TEL moiety of the fusion protein is chiefly responsible for its action as a transcriptional repressor of AML1 target genes. Given the unknown nature of the mechanisms by which TEL and TEL-AML1 repress transcription, we sought to examine whether, in analogy with the acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL)–associated RARα fusion proteins,19-21 they could involve recruitment of nuclear receptor corepressor complexes.

Materials and methods

Expression and luciferase reporter plasmids

Mammalian and in vitro expression vectors for full-length and partial N-CoR,22 TEL,15,18 TRAC-2 (SMRT),23 and mSin3A24 proteins were previously described by others. TEL-AML1 was generated from the REH cell25 RNA by reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). The 5′-end of the AML1 construct was generated by RT-PCR from the K562 cell RNA and used to replace the TEL portion in the TEL-AML1 complementary DNA (cDNA). The above cDNAs were sequenced to confirm that there were no PCR-introduced errors and were then cloned into the pcDNA3.1(+) expression vector (Invitrogen, Westbrook, ME). All the AML1 expression vectors are based on the human AML1 isoform that encodes a protein of 479 amino acids in length and is often referred to as AML1B.26 Both TEL(Δ53-116) and TEL(Δ53-116) AML1 were constructed in a cytomegalovirus (CMV) major immediate-early promoter/enhancer–based expression vector pSCTOP.27 Expression vectors for the wild type TEL and TEL(Δ119-336) were as previously described.18 Mammalian 2-hybrid expression vectors were derived from pGALO and pNLVP16 plasmids28 by subcloning indicated cDNAs in frame with the coding regions for the GAL4 DNA-binding and VP16-activating domains, respectively. The GAL4(UAS)5-TkLUC reporter was as previously described.21 TEL-RE-TkLUC was constructed by inserting an annealed oligonucleotide pair with a single ETS consensus binding site, 5′-GATCCTAAACAGGAAGTG-3′, into theBacillus amyloliquefaciens H (BamHI) site of pT109LUC.29

In vitro and in vivo co-immunoprecipitation assays

We synthesized sulfur 35 (35S)–methionine–labeled proteins in vitro using a rabbit reticulocyte lysate–coupled transcription-translation system (TNT; Promega, Charbonnieres, France). To ensure that approximately equal amounts of various in vitro translated proteins or deletion mutants of a given protein were used in each experiment, efficiency of each translation reaction was checked by Western blot analysis with an appropriate antibody (not shown). For a given co-immunoprecipitation, 1-2 μL in vitro translated protein (from a 50-μL transcription-translation reaction) was incubated at 4°C for 1 hour in NETN [20 mmol/L Tris (tris[hydroxymethyl] aminomethane) (pH 8.0),100 mmol/L sodium chloride (NaCl),1 mmol/L ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), and 0.5% NP-40] with 1 μL of a specific antibody. The total reaction volume was 500 μL.

Following the addition of 15 μL Protein A/G PLUS agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), the incubation was continued for an extra hour. Protein A/G PLUS agarose beads were then washed twice with 500 μL H buffer [20 mmol/L HEPES (4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid) (pH 7.7), 50 mmol/L potassium chloride (KCl), 20% glycerol, and 0.1% NP-40] and resuspended in 500 μL NETN buffer. A second35S-methionine–labeled protein (5 μL out of 50 μL total transcription-translation reaction) was then added to the above solution, and incubation was continued in NETN buffer at 4°C for an additional hour with gentle rocking. Subsequently, Protein A/G PLUS agarose beads were washed 5 times with 500 μL H buffer. Bound proteins were eluted in Laemmeli loading buffer and separated on a 5% or 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The gels were fixed in 25% isopropanol and 10% acetic acid, dried, and exposed to Kodak Biomax film (Kodak-Eastman, Rochester, NY).

For co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous N-CoR and TEL-AML1 from REH cells25 or transfected 293T cells, whole cell extracts were prepared as described.30 The cell extracts were incubated at 4°C for 60 minutes with polyclonal antibodies specific against mSin3A, human N-CoR (C-20), murine N-CoR (N-19) (all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; brand names in parentheses), AML1 (J.H. and L.M.W., unpublished data, April 1998), or amino terminus of TEL31 in NETN buffer containing protease inhibitors. Immunocomplexes were isolated by overnight incubation at 4°C with Protein A/G PLUS agarose beads, washed 5 times in H buffer, and analyzed using an anti-TEL antibody31 by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

Cell culture, transfections, and reporter assays

Mammalian 2-hybrid experiments were carried out by cotransfecting the 293T cells with 100 ng of GAL4(UAS)5-TkLUC reporter plasmid; 50 ng GAL4(DBD)-N-CoR, GAL4(DBD)-SMRT, or GAL4(DBD)-mSin3A expression vector (or an empty vector, pGALO); 100 ng CMV-lacZ internal control; and 200 ng of an expression vector for a given VP16 fusion protein. In the remaining transient cotransfection assays, 200 ng of a given reporter and 50 or 100 ng (Figure 3, legend) of each expression vector were used. Western blot analysis of transiently expressed proteins was carried out to monitor the levels of expression of each protein (not shown). All transient transfections of 293T cells, maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), were performed using the calcium phosphate precipitation method as previously described.21 All transfections were performed in triplicates, and the results represent an average of at least 3 independent experiments. The error bars correspond to SD.

Results

Although initially discovered through studies of transcriptional regulation by nuclear receptors, N-CoR32 or SMRT33 have subsequently been shown to be part of the multisubunit corepressor complexes, which include associated histone deacetylases (HDACs).34,35 To evaluate whether the abilities of TEL and TEL-AML1 to repress transcription may be due to recruitment of nuclear receptor corepressor/HDAC complexes, we first investigated their interactions with N-CoR and SMRT using in vitro co-immunoprecipitation experiments. Both TEL and TEL-AML1, but not the wild type AML1 protein, readily co-immunoprecipitated with35S-methionine–labeled N-CoR (Figure 1A, compare lane 5 with lanes 4, 6, and 7). These results were entirely dependent on the presence of TEL in the co-immunoprecipitation reaction, as anti-TEL antibodies alone failed to co-immunoprecipitate the35S-methionine–labeled N-CoR proteins (Figure 1A, B, and F, lane 2). In this respect, it is also noteworthy that cross-reactivity was not observed between anti-AML1 antibodies and N-CoR (Figure 1A, lane 3). Association between N-CoR and TEL in vitro was unaffected by the deletion of TEL amino acids 53-116 (Figure 1B, lane 4), which contain its PD and are important for its interaction with the mSin3A protein36 (F.G and A.Z., unpublished results, February 1999). However, deletion of the central region of TEL, which lies between its PD and ETS domains (amino acids 119-336), considerably (more than 50%) reduced the level of co-immunoprecipitated 35S-methionine–labeled N-CoR (Figure1B, lane 5), thereby indicating that this region is required for interaction between the 2 proteins in vitro. Given that the above mapped N-CoR interaction domain is retained in the TEL moiety of the TEL-AML1 fusion protein, these results are consistent with the ability of TEL-AML1, but not AML1, to interact with N-CoR (Figure 1A).

TEL and TEL-AML1 interact with N-CoR in vitro.

The in vitro–translated TEL, TEL(Δ53-116), TEL(Δ119-336), TEL-AML1, TEL(Δ53-116)-AML1, and/or AML1 proteins were evaluated for their abilities to interact with (A, B)35S-methionine–labeled N-CoR or (C) SMRT as well as with (D-F) the indicated amino- and carboxy-terminal deletions of N-CoR. The co-immunoprecipitation with mSin3A shown in panel F, lanes 5 and 6, was used as a positive control. The numbers represent the first and the last amino acid in a given protein (or its deletion mutant). In panels A-F, lane 1, 20% of the input is shown. Specificity of the antibody used for a given co-immunoprecipitation is indicated above each panel. In the absence of a given antibody target protein (TEL or AML1), neither full-length N-CoR nor its deletion mutants (amino acids 1-1461, 1586-2453, or 1-758) were co-immunoprecipitated by anti-TEL (shown in panels A, B, and F, lane 2, and panels D and E, lanes 4 and 5, respectively) or anti-AML1 (shown in panel A, lane 3). Prior to their use in a given co-immunoprecipitation reaction, levels of each in vitro translated protein were evaluated by Western blotting to ensure that approximately equal amounts of all antibody-specific input proteins were used for each experiment (data not shown).

TEL and TEL-AML1 interact with N-CoR in vitro.

The in vitro–translated TEL, TEL(Δ53-116), TEL(Δ119-336), TEL-AML1, TEL(Δ53-116)-AML1, and/or AML1 proteins were evaluated for their abilities to interact with (A, B)35S-methionine–labeled N-CoR or (C) SMRT as well as with (D-F) the indicated amino- and carboxy-terminal deletions of N-CoR. The co-immunoprecipitation with mSin3A shown in panel F, lanes 5 and 6, was used as a positive control. The numbers represent the first and the last amino acid in a given protein (or its deletion mutant). In panels A-F, lane 1, 20% of the input is shown. Specificity of the antibody used for a given co-immunoprecipitation is indicated above each panel. In the absence of a given antibody target protein (TEL or AML1), neither full-length N-CoR nor its deletion mutants (amino acids 1-1461, 1586-2453, or 1-758) were co-immunoprecipitated by anti-TEL (shown in panels A, B, and F, lane 2, and panels D and E, lanes 4 and 5, respectively) or anti-AML1 (shown in panel A, lane 3). Prior to their use in a given co-immunoprecipitation reaction, levels of each in vitro translated protein were evaluated by Western blotting to ensure that approximately equal amounts of all antibody-specific input proteins were used for each experiment (data not shown).

To determine which regions of N-CoR interact with TEL, we carried out a co-immunoprecipitation analysis using a series of35S-methionine–labeled N-CoR deletion mutants (Figure1D-F). This analysis showed that the first 758 amino acids of N-CoR, which contain the so-called repression domain I (RPDI), were sufficient for interaction with TEL (Figure 1F, lane 3). Consistent with these results, an isoform of SMRT that lacks N-CoR–related amino-terminal sequences (including RPD1), but is otherwise highly homologous to it, did not appear to interact with TEL both in vitro and in vivo (Figures1C and 2A). Nevertheless, we cannot exclude the possibility that a SMRT isoform, which possesses N-CoR–related RPD1,37 would interact with the TEL protein.

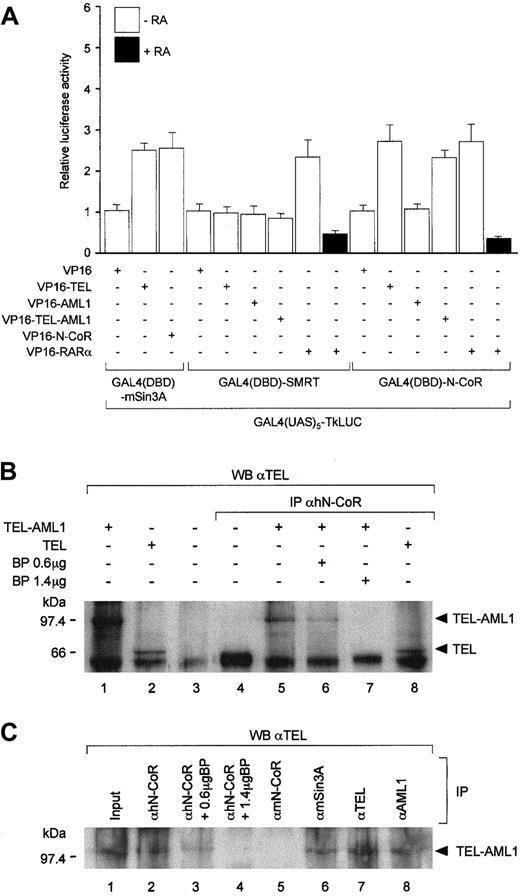

TEL and TEL-AML1 interact with N-CoR in vivo.

(A) Mammalian 2 hybrid analysis of interaction between the entire N-CoR, SMRT, or mSin3A (as a positive control) fused to the GAL4(DBD) and VP16-activation domain tagged TEL or TEL-AML1. In agreement with the in vitro co-immunoprecipitation results, full-length AML1 fused to the VP16-activation domain failed to interact with GAL4(DBD)-N-CoR. No significant interaction was also detected in this assay between SMRT and TEL or AML1. Interactions between VP16-TEL and GAL4(DBD)-mSin3A are shown as a positive control. Interactions between GAL4(DBD)-N-CoR or GAL4(DBD)-SMRT and VP16 tagged RARα in the absence or presence of all-trans-retinoic acid (RA) are used as additional positive and negative controls, respectively. Co-transfection of an empty GAL4(DBD) vector (pGALO) either with VP16-TEL or VP16-AML1 did not result in activation of the luciferase gene expression (not shown). (B) Co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous human (h) N-CoR and TEL-AML1 (lanes 5-7) or TEL (lane 8) from 293T cells transfected with their respective expression vectors. Lanes 6 and 7 show decreasing levels of the co-immunoprecipitated TEL-AML1 protein with increasing amounts of the N-CoR antigenic peptide in the reaction. Input (20%) is shown in lanes 1-3. Lane 3 corresponds to protein extract derived from untransfected 293T cells. Size markers in kd are indicated on the left of the panel. (C) Antibodies against human N-CoR co-immunoprecipitate the endogenous TEL-AML1 protein from REH cells with t(12;21). Proteins were co-immunoprecipitated from whole cell extracts using polyclonal antibodies specific against human N-CoR (lane 2), murine N-CoR (lane 5), mSin3A (lane 6), TEL (lane 7), and AML1 (lane 8), as indicated. Immunoprecipitated material was resolved by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using anti-TEL antibody. Lanes 3 and 4 correspond to co-immunoprecipitation carried out in the presence of 0.6- and 1.4-μg N-CoR antigenic peptide. Lane 1 represents 20% of the input for the co-immunoprecipitation reaction. Size markers in kd are indicated on the left of the panel.

TEL and TEL-AML1 interact with N-CoR in vivo.

(A) Mammalian 2 hybrid analysis of interaction between the entire N-CoR, SMRT, or mSin3A (as a positive control) fused to the GAL4(DBD) and VP16-activation domain tagged TEL or TEL-AML1. In agreement with the in vitro co-immunoprecipitation results, full-length AML1 fused to the VP16-activation domain failed to interact with GAL4(DBD)-N-CoR. No significant interaction was also detected in this assay between SMRT and TEL or AML1. Interactions between VP16-TEL and GAL4(DBD)-mSin3A are shown as a positive control. Interactions between GAL4(DBD)-N-CoR or GAL4(DBD)-SMRT and VP16 tagged RARα in the absence or presence of all-trans-retinoic acid (RA) are used as additional positive and negative controls, respectively. Co-transfection of an empty GAL4(DBD) vector (pGALO) either with VP16-TEL or VP16-AML1 did not result in activation of the luciferase gene expression (not shown). (B) Co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous human (h) N-CoR and TEL-AML1 (lanes 5-7) or TEL (lane 8) from 293T cells transfected with their respective expression vectors. Lanes 6 and 7 show decreasing levels of the co-immunoprecipitated TEL-AML1 protein with increasing amounts of the N-CoR antigenic peptide in the reaction. Input (20%) is shown in lanes 1-3. Lane 3 corresponds to protein extract derived from untransfected 293T cells. Size markers in kd are indicated on the left of the panel. (C) Antibodies against human N-CoR co-immunoprecipitate the endogenous TEL-AML1 protein from REH cells with t(12;21). Proteins were co-immunoprecipitated from whole cell extracts using polyclonal antibodies specific against human N-CoR (lane 2), murine N-CoR (lane 5), mSin3A (lane 6), TEL (lane 7), and AML1 (lane 8), as indicated. Immunoprecipitated material was resolved by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using anti-TEL antibody. Lanes 3 and 4 correspond to co-immunoprecipitation carried out in the presence of 0.6- and 1.4-μg N-CoR antigenic peptide. Lane 1 represents 20% of the input for the co-immunoprecipitation reaction. Size markers in kd are indicated on the left of the panel.

In addition to the amino terminal TEL-interacting region of N-CoR described above, a very low level association between the carboxy-terminal half of the corepressor (amino acids 1586-2453) and TEL (Figure 1E, lane 2) or TEL-AML1 (not shown) was also detected in our in vitro co-immunoprecipitation assay. In this respect, it is worth noting that a weak association between the transiently expressed TEL and SMRT isoform identical to that used in this study was detected by a co-immunoprecipitation assay.38 Whether these results reflect a second much weaker interaction domain or some indirect association between TEL and the carboxy-terminal halves of the 2 corepressors remains to be established. It is unlikely, however, that these weaker interactions could be mediated by mSin3A, as deletion of its interaction domain (PD) in TEL36 does not appear to diminish its ability to interact with the N-CoR proteins (Figure 1B, lane 4; Figure 1D,E, lane 3).

The above in vitro data documenting the interaction between N-CoR and the TEL protein was confirmed in vivo using the mammalian 2-hybrid assay (Figure 2A). As expected from the previously published data, which showed co-immunoprecipitation between the TEL and mSin3A proteins,36 VP16-TEL interacted readily with GAL4(DBD)-mSin3A. Additionally, in agreement with a well documented mechanism of nuclear receptor action,32 33 GAL4(DBD)-N-CoR or GAL4(DBD)-SMRT interacted with VP-16-RARα in the absence, but not in the presence, of all-trans-retinoic acid (RA). As indicated by comparable enhancement of reporter gene activation, VP16-TEL or -TEL-AML1 interacted with GAL4(DBD)-N-CoR to a degree similar to that reflected in the interactions between the control proteins. Consistent with our in vitro results (see above), AML1 fused to the VP16-activation domain failed to interact with GAL4(DBD)-N-CoR, and similarly, VP16-TEL or VP16-TEL-AML1 did not appear to interact with GAL4(DBD)-SMRT in this assay (Figure 2A).

To further address the physiological relevance of association between TEL-AML1 and N-CoR, we set out to co-immunoprecipitate the 2 proteins from cells transfected with their respective expression vectors (Figure2B) or from the REH leukemic cell line, which possesses the TEL/AML1 rearrangement (Figure 2C). Using antibodies to endogenously express human N-CoR, both TEL-AML1 and TEL were readily co-immunoprecipitated from transfected 293T cells (Figure 2B, lanes 5 and 8, respectively). Specificity of this assay was corroborated by blocking of the TEL-AML1 and TEL co-immunoprecipitation with the addition of increasing amounts of an antigenic peptide derived from the N-CoR protein (Figure 2B, lanes 6 and 7, and data not shown). Similarly, Western blotting of proteins co-immunoprecipitated from the REH cell extracts with anti-human N-CoR (Figure 2C, lane 2), but not normal rabbit serum (data not shown) or antimurine N-CoR antibody (Figure 2C, lane 5) controls, revealed an anti-TEL reactive protein. The same band was seen with anti-TEL antibodies in the REH cell extracts without immunoprecipitation (Figure 2C, lane 1) or after immunoprecipitation with anti-mSin3A (Figure 2C, lane 6); anti-TEL (Figure 2C, lane 7); or anti-AML1 (Figure 2C, lane 8) antibodies. As before, addition of the N-CoR antigenic peptide inhibited the co-immunoprecipitation (Figure2C, lanes 3 and 4). It should be noted that the protein co-immunoprecipitated from REH cells migrates slightly higher than TEL-AML1 co-immunoprecipitated from transfected 293T cells. Nevertheless, the above observations strongly indicate that despite its higher than expected molecular size, the species co-immunoprecipitated from REH cells corresponds to the TEL-AML1 protein. In this respect, it is worth noting that previous studies31 demonstrated anti-TEL reactive proteins in REH cells, which also migrated above 100 kd. Taken together, our co-immunoprecipitation results are consistent with the in vitro and in vivo data described above and strongly suggest that TEL-AML1 engages in a stable complex with N-CoR at physiological concentrations in vivo.

Discussion

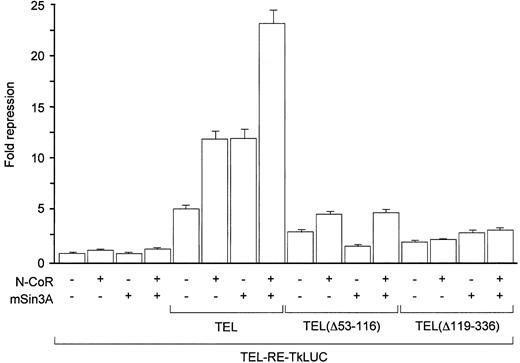

The above data addressing the interaction between TEL and N-CoR suggested that TEL might possess a transcriptional repression domain that requires N-CoR for activity. Consistent with the above hypothesis, TEL could repress the expression of a reporter gene containing a single ETS binding site (shown to bind TEL in vitro)15 fused upstream from the HSV-Tk promoter (Figure3). As expected, co-expression of N-CoR stimulated repression by the wild type TEL, but not by the mutant protein in which the N-CoR interaction domain was deleted (Figure 3). Co-expression of mSin3A, an additional component of the co-repressor complex with which TEL was shown to interact36 (data not shown), displayed a similar degree of stimulation of TEL-mediated repression and dependency of this effect on an intact interaction domain (PD) in the TEL protein. It is noteworthy that both corepressors were required for maximal repression by TEL, suggesting that both mSin3A and N-CoR may interact with independent domains of TEL and with each other to form a stable repressor/corepressor complex. Nevertheless, N-CoR was able to potentiate the repression of TEL lacking the mSin3A interaction domain, but mSin3A was ineffective in stimulating repression by TEL lacking the N-CoR binding region (Figure 3). These results could suggest that interaction between TEL and N-CoR may be more critical for the stability of the TEL/corepressor complex in vivo. They are also in agreement with previous reports18 addressing the role of the central region of TEL in transcriptional repression as well as the requirement of both the PD and central region for optimal effects of TEL on transcription from a reporter gene in vivo.

Coexpression of N-CoR potentiates transcriptional repression by TEL, but not by TEL lacking the N-CoR interaction domain.

TEL, TEL(Δ53-116), or TEL(Δ119-336) expression plasmid (50 ng) was cotransfected with 200 ng of a luciferase reporter containing a single ETS consensus binding site upstream of HSV-Tk minimal promoter (TEL-RE-TkLUC) and 100 ng expression vectors for N-CoR and/or mSin3A as indicated. The expression of TEL had no effect on the reporter activity in the absence of the ETS binding site, and there were no significant variations observed in the expression of TEL proteins between different samples (data not shown).

Coexpression of N-CoR potentiates transcriptional repression by TEL, but not by TEL lacking the N-CoR interaction domain.

TEL, TEL(Δ53-116), or TEL(Δ119-336) expression plasmid (50 ng) was cotransfected with 200 ng of a luciferase reporter containing a single ETS consensus binding site upstream of HSV-Tk minimal promoter (TEL-RE-TkLUC) and 100 ng expression vectors for N-CoR and/or mSin3A as indicated. The expression of TEL had no effect on the reporter activity in the absence of the ETS binding site, and there were no significant variations observed in the expression of TEL proteins between different samples (data not shown).

Taken together, this work strongly suggests that N-CoR plays an important role in transcriptional repression by TEL and probably also the TEL-AML1 fusion protein. N-CoR recruitment has also been implicated in the function of the t(8;21)-associated AML1-ETO fusion protein.39-41 Given that both N-CoR and mSin3A can independently recruit HDACs,34 35 it is likely that as with the APL-associated fusion proteins, HDAC recruitment will prove to be important in the molecular pathogeneses of leukemias associated withAML1 gene rearrangements. The discoveries that recruitment of nuclear receptor corepressors also underlies the molecular pathogeneses of AML1-associated acute leukaemias highlight their importance in hemopoiesis and further indicate the potential value of HDAC inhibitors in antileukemic therapies.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to G. Groseveld, C. D. Laherty, R. N. Eisenman, C. A. Hassig, S. L. Schreiber, C. K. Glass, M. Soderstrom, and S. Waxman for their generous gifts of molecular clones, expression vectors, and antibodies, which were used in this study.

Supported by grants (A.Z., L.M.W., and M.G.) from the Specialist Programme and a project grant (J.H. and L.M.W.) from the Leukaemia Research Fund of Great Britain, London, England. Partially supported by grant CA59936-06, the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, and contract BMH4-CT96-1355 from the Biomed 2 Research Programme. F.G. and J.H. were also supported by the TMR Programme Marie Curie Research Training Grants from the European Commission, and K.P. was also supported by an ICR studentship.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Arthur Zelent, Leukaemia Research Fund Centre at the Institute of Cancer Research, Chester Beatty Laboratories, 237 Fulham Road, London SW3 6JB, England; e-mail:a.zelent@icr.ac.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal