Abstract

STI 571 (formerly known as CGP 57148B) is a known inhibitor of the c-abl, bcr-abl, and platelet-derived growth-factor receptor (PDGFR) tyrosine kinases. This compound is being evaluated in clinical trials for the treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia. We sought to extend the activity profile of STI 571 by testing its ability to inhibit the tyrosine kinase activity of c-kit, a receptor structurally similar to PDGFR. We treated a c-kit expressing a human myeloid leukemia cell line, M-07e, with STI 571 before stimulation with Steel factor (SLF). STI 571 inhibited c-kit autophosphorylation, activation of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase, and activation of Akt without altering total protein levels of c-kit, MAP kinase, or Akt. The concentration that produced 50% inhibition for these effects was approximately 100 nmol/L. STI 571 also significantly decreased SLF-dependent growth of M-07e cells in a dose-dependent manner and blocked the antiapoptotic activity of SLF. In contrast, the compound had no effect on MAP kinase activation or cellular proliferation in response to granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. We also tested the activity of STI 571 in a human mast cell leukemia cell line (HMC-1), which has an activated mutant form of c-kit. STI 571 had a more potent inhibitory effect on the kinase activity of this mutant receptor than it did on ligand-dependent activation of the wild-type receptor. These findings show that STI 571 selectively inhibits c-kit tyrosine kinase activity and downstream activation of target proteins involved in cellular proliferation and survival. This compound may be useful in treating cancers associated with increased c-kit kinase activity.

c-kit, a 145-kd transmembrane glycoprotein, is the normal cellular homologue of the viral oncogene v-kit and a member of the receptor tyrosine kinase subclass III family that includes receptors for platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and flt3 ligand.1-3 The c-kit gene product is expressed by hematopoietic progenitor cells, mast cells, germ cells, interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC), and some human tumors.4-8 Studies of mice with inactivating mutations of c-kit or its ligand, Steel factor (SLF), demonstrated that normal functional activity of the c-kit gene product is absolutely essential for maintenance of normal hematopoiesis,9,10melanogenesis,5 gametogenesis,11 and growth and differentiation of mast cells and ICC.12-14 We and others showed that SLF is produced by human and murine hematopoietic stromal cells, including endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and bone marrow–derived stromal cells.15,16 The biologic features of SLF and c-kit were reviewed by Broudy17 and Lyman and Jacobsen.18

In addition to its importance in normal cellular physiologic activities, c-kit plays a role in the biologic aspects of certain human cancers, including germ cell tumors, mast cell tumors, gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST), small-cell lung cancer, melanoma, breast cancer, acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), and neuroblastoma.19-27Proliferation of tumor cell growth mediated by c-kit occurs either by a specific mutation of the c-kit polypeptide that results in ligand-independent activation or by autocrine stimulation of the receptor.21,23 In some types of tumors, inhibition of c-kit activity reduces cellular proliferation, suggesting a role for use of pharmacologic inhibitors of c-kit in the treatment of c-kit–dependent malignancies.20,21,28 29

STI 571 (formerly known as CGP 57148B), a 2-phenylaminopyrimidine derivative, is a known inhibitor of the c-abl, bcr-abl, and PDGF receptor (PDGFR) tyrosine kinases.30,31 This compound is currently being evaluated in clinical trials for the treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML).32,33 There is a close homology between the kinase domains of PDGFR and c-kit. Previous reports on other PDGFR kinase inhibitors noted that some of these compounds can inhibit the kinase activity of c-kit.34,35Therefore, we speculated that STI 571 would also potently inhibit the kinase activity of c-kit. Using biochemical and cell-based assays of receptor activation, signal transduction, proliferation, and apoptosis, we found that STI 571 inhibited the SLF-dependent activation of wild-type c-kit kinase activity. The concentration that produced 50% inhibition (IC50) for these effects was approximately 100 nmol/L, which is similar to the concentration required for inhibition of bcr-abl and PDGFR. We also performed similar studies using a mast cell leukemia cell line, HMC-1, that expresses a constitutively activated c-kit polypeptide.36 37 STI 571 had a more potent inhibitory effect on the kinase activity of this mutant receptor than it did on ligand-dependent activation of the wild-type receptor. We conclude that STI 571 is a potent inhibitor of c-kit kinase activity and may be useful in treating tumors that are partly or completely dependent on c-kit for proliferation or survival.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

M-07e is a human myeloid leukemia cell line that is dependent on the growth factors interleukin 3, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), or SLF (Sigma, St Louis, MO) for proliferation.38 These cells, a generous gift of Dr Hal Broxmeyer (Indiana University School of Medicine), were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Gibco-BRL, Rockville, MD) supplemented with 10% fetal-calf serum (FCS) and 200 U/mL recombinant human GM-CSF (Immunex, Seattle, WA). HMC-1, a factor-independent cell line derived from a patient with mast cell leukemia, expresses a juxtamembrane mutant c-kit polypeptide that has constitutive kinase activity.37,39 40 The HMC-1 cells were generously provided by Dr Joseph Butterfield (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN) and maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Gibco-BRL) supplemented with 10% FCS.

Reagents

Dr Elizabeth Buchdunger (Novartis Pharma, Basel, Switzerland) generously provided STI 571 for these experiments. Fresh stock solutions of inhibitor (10 mmol/L) were made before each experiment by dissolving 5 mg STI 571 in 1 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Gibco-BRL).

Antibodies

An anti-c-kit monoclonal antibody was used at a dilution of 1:200 (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN). An antiphosphotyrosine (anti-P-Tyr) antibody (PY20) was used at a dilution of 1:1000 (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY). An antiphospho-p44/p42 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase antibody that identifies MAP kinase phosphorylated at threonine 202 and tyrosine 204 was used at a dilution of 1:1000 (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA). Antibodies to total MAP kinase and total Akt (New England Biolabs) were both used at a dilution of 1:1000. An antiphospho-Akt antibody that identifies Akt phosphorylated at serine 473 was used at a dilution of 1:1000 (New England Biolabs). Peroxidase-conjugated goat-antimouse antibody was used at a dilution of 1:5000 and goat antirabbit antibody at a dilution of 1:10 000 (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Protein lysates

M-07e cells were grown in serum-free RPMI 1640 at 37°C for approximately 18 hours before they were incubated for 90 minutes in the presence of various concentrations of STI 571. The cells were then pelleted and resuspended in 1 mL RPMI 1640. STI 571 was added to each tube to achieve the same concentration used during the 90 minutes of preincubation. The cells were then incubated with inhibitor and growth factor (SLF [Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO] or GM-CSF) for 15 minutes at 37°C. Subsequently, the cell pellets were lysed with 100 to 250 μL of protein lysis buffer (50 mmol/L Tris, 150 mmol/L sodium chloride, 1% NP-40, and 0.25% deoxycholate, with addition of the inhibitors aprotinin, leupeptin, pepstatin, phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride, and sodium orthovanadate [Sigma]). Western immunoblot analysis was performed as previously described.41Experiments with HMC-1 cells were performed in the same way except that neither SLF nor GM-CSF was added.

Proliferation assays

Cells were added to 96-well plates at a density of 20 000 cells/well for HMC-1 and 50 000 cells/well for M-07e. Experiments with M-07e were performed with use of GM-CSF or SLF as a growth factor supplement. Experiments using HMC-1 were performed without growth factor supplementation. Proliferation at 48 hours was measured with an XTT-based assay (Roche Molecular Biochemicals).

Apoptosis assays

Results

STI 571 inhibits kinase activity of wild-type and mutant c-kit polypeptide

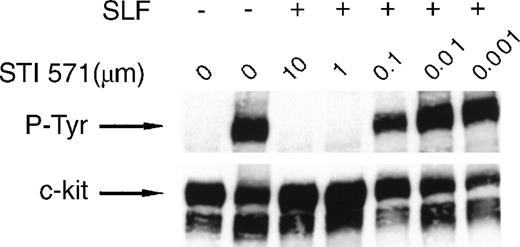

We used the factor-dependent human myeloid leukemia cell line M-07e to test the ability of STI 571 to inhibit the kinase activity of wild-type c-kit receptor. Lysates prepared from M-07e cells were probed with an anti-P-Tyr specific antibody. In these experiments, SLF-dependent activation was measured by receptor autophosphorylation.44 45 No significant c-kit autophosphorylation was observed in the absence of SLF (Figure1). Inhibition of SLF-induced c-kit autophosphorylation by STI 571 was dose dependent, with complete inhibition observed at both 10 and 1.0 μmol/L. Inhibition was also apparent at a dose of 0.5 μmol/L, although limited c-kit autophosphorylation still occurred. At an STI 571 dose of 0.1 μmol/L, c-kit activation was approximately 50% that in SLF-stimulated cells not treated with inhibitor. Thus, we found that SLF activates c-kit and that this activation was effectively inhibited by doses of STI 571 in the range of 0.1 to 10 μmol/L.

STI 571 inhibits Steel factor (SLF)–dependent phosphorylation of c-kit.

Serum was withheld from M-07e cells overnight before they were pretreated with various concentrations of STI 571 for 90 minutes. Cells were then treated with vehicle (phosphate-buffered saline) or SLF (final concentration, 200 ng/mL) for 15 minutes. Whole cell lysates were immunoblotted by using an antiphosphotyrosine (anti-P-Tyr) antibody. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with a monoclonal antibody specific for human c-kit. The arrow indicates the position of the 145-kd isoform of c-kit. Representative results from 1 of 8 independent experiments are shown.

STI 571 inhibits Steel factor (SLF)–dependent phosphorylation of c-kit.

Serum was withheld from M-07e cells overnight before they were pretreated with various concentrations of STI 571 for 90 minutes. Cells were then treated with vehicle (phosphate-buffered saline) or SLF (final concentration, 200 ng/mL) for 15 minutes. Whole cell lysates were immunoblotted by using an antiphosphotyrosine (anti-P-Tyr) antibody. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with a monoclonal antibody specific for human c-kit. The arrow indicates the position of the 145-kd isoform of c-kit. Representative results from 1 of 8 independent experiments are shown.

To determine whether STI 571 modulated expression of c-kit protein, the membrane was stripped and reprobed with an anti-c-kit primary antibody. The total amount of expressed c-kit protein did not change after exposure to STI 571 (Figure 1). Thus, STI 571 was found to inhibit SLF-dependent c-kit autophosphorylation but not expression of c-kit protein.

Activating mutations of c-kit have been found in several types of human malignant disease, including mastocytosis and mast cell leukemia, AML, GIST, and seminoma and dysgerminoma tumors.22-24,46-49 These mutations occur in 2 distinct regions of the cytoplasmic portion of the c-kit polypeptide—the juxtamembrane domain and the kinase domain.22,46-48,50 The mutations result in ligand-independent constitutive kinase activity.51-53 STI 571 functions as a competitive inhibitor of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) binding to the kinase domain; therefore, mutations that alter receptor structure or function might abrogate the inhibitory effects of STI 571 on c-kit kinase activity.

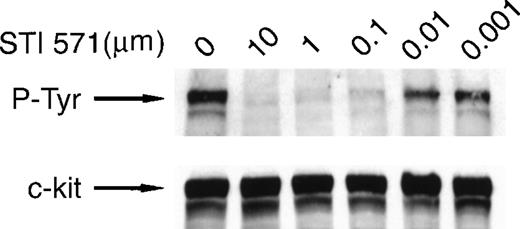

To test the efficacy of STI 571 in inhibiting the activity of mutant forms of c-kit, we used a human mast cell leukemia cell line (HMC-1) that expresses a constitutively activated c-kit polypeptide.37 Lysates prepared from HMC-1 cells were probed with an anti-P-Tyr antibody, and receptor activation was assessed by measuring autophosphorylation. As reported previously,37 c-kit autophosphorylation was observed in the absence of SLF (Figure 2). Inhibition of c-kit autophosphorylation by STI 571 was dose dependent, with complete inhibition observed at doses of 10 and 1.0 μmol/L. Nearly complete inhibition occurred at a dose of 0.1 μmol/L. Limited autophosphorylation of c-kit was observed when STI 571 doses of 0.001 to 0.01 μmol/L were used. Thus, our study showed that STI 571 not only inhibits the autophosphorylation of the mutated c-kit receptor in HMC-1 cells but is also a more potent inhibitor of this mutated receptor than it is of the wild-type c-kit receptor. To determine whether STI 571 modulated expression of c-kit protein, the membrane was stripped and reprobed with an anti-c-kit antibody. There was no change in the expression of c-kit protein in cells treated with STI 571 (Figure 2). Therefore, we found that STI 571 decreases autophosphorylation of mutant c-kit polypeptide by inhibiting c-kit kinase activity rather than by down-regulating expression of c-kit protein.

STI 571 inhibits autophosphorylation of an activated mutant form of c-kit.

HMC-1 cells were treated with various concentrations of STI 571 for 90 minutes. Whole cell lysates were prepared and immunoblotted with an anti-P-Tyr monoclonal antibody. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with a monoclonal antibody specific for human c-kit. The arrow indicates the position of the 145-kd isoform of c-kit. Representative results from 1 of 8 independent experiments are shown.

STI 571 inhibits autophosphorylation of an activated mutant form of c-kit.

HMC-1 cells were treated with various concentrations of STI 571 for 90 minutes. Whole cell lysates were prepared and immunoblotted with an anti-P-Tyr monoclonal antibody. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with a monoclonal antibody specific for human c-kit. The arrow indicates the position of the 145-kd isoform of c-kit. Representative results from 1 of 8 independent experiments are shown.

STI 571 inhibits c-kit–dependent but not GM-CSF receptor–dependent activation of MAP kinase

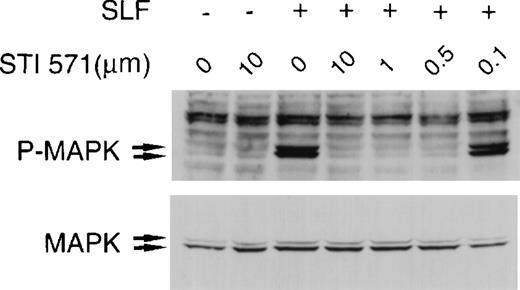

Treatment of hematopoietic cells with SLF or GM-CSF results in activation of MAP kinase.54-56 We sought to test the specificity of STI 571 by examining its effects on SLF-dependent and GM-CSF–dependent activation of MAP kinase in M-07e cells. Complete inhibition of SLF-dependent activation of MAP kinase occurred at 10-, 1.0-, and 0.5-μmol/L concentrations of STI 571 (Figure3). At a dose of 0.1 μmol/L STI 571, MAP kinase–activation levels were significantly lower than those in control SLF-stimulated cells. Total MAP kinase expression was not altered by treatment with STI 571 (Figure 3).

STI 571 inhibits SLF-dependent activation of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase.

Whole cell lysates of M-07e cells were prepared and immunoblotted with a polyclonal antibody specific for the doubly phosphorylated forms of p44 and p42 MAP kinase (Erk1 and Erk2). The membrane was stripped and reprobed with an antibody for total p44 and p42 MAP kinase. The arrows indicate the locations of p44 and p42 MAP kinase. Representative results from 1 of 8 independent experiments are shown.

STI 571 inhibits SLF-dependent activation of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase.

Whole cell lysates of M-07e cells were prepared and immunoblotted with a polyclonal antibody specific for the doubly phosphorylated forms of p44 and p42 MAP kinase (Erk1 and Erk2). The membrane was stripped and reprobed with an antibody for total p44 and p42 MAP kinase. The arrows indicate the locations of p44 and p42 MAP kinase. Representative results from 1 of 8 independent experiments are shown.

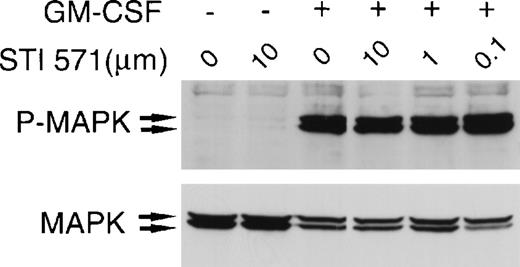

To confirm the specificity of STI 571, we examined the compound's effect on GM-CSF–dependent activation of MAP kinase. At concentrations of 0.1 to 10 μmol/L, STI 571 did not affect GM-CSF–induced MAP kinase activation in M-07e cells (Figure4). Moreover, treatment with STI 571 did not alter total expression of MAP kinase. Thus, we found that STI 571 inhibits SLF-dependent but not GM-CSF–dependent activation of MAP kinase.

STI 571 does not inhibit granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)–dependent activation of MAP kinase.

Serum was withheld from M-07e cells overnight. The cells were then pretreated with various concentrations of STI 571 for 90 minutes before the addition of vehicle or GM-CSF (final concentration, 200 U/mL) for 15 minutes. Whole cell lysates were immunoblotted with an antibody specific for phospho-MAP kinase. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with an antibody for total p44 and p42 MAP kinase. The arrows indicate the locations of p44 and p42 MAP kinase. Representative results from 1 of 2 independent experiments are shown.

STI 571 does not inhibit granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)–dependent activation of MAP kinase.

Serum was withheld from M-07e cells overnight. The cells were then pretreated with various concentrations of STI 571 for 90 minutes before the addition of vehicle or GM-CSF (final concentration, 200 U/mL) for 15 minutes. Whole cell lysates were immunoblotted with an antibody specific for phospho-MAP kinase. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with an antibody for total p44 and p42 MAP kinase. The arrows indicate the locations of p44 and p42 MAP kinase. Representative results from 1 of 2 independent experiments are shown.

To confirm that STI 571 could inhibit signal-transduction events downstream of an activated mutant form of c-kit, we treated HMC-1 cells with various concentrations of inhibitor. Complete inhibition of MAP kinase activation occurred at 10- and 1.0-μmol/L concentrations of STI 571 (Figure 5). Partial inhibition was observed at a dose of 0.1 μmol/L, and no inhibition occurred at a dose of 0.01 μmol/L. Total MAP kinase expression was not altered by treatment with STI 571 (Figure 5). Therefore, we found that STI 571 inhibits the kinase activity of this mutant form of c-kit and blocks c-kit–dependent activation of MAP kinase.

STI 571 inhibits c-kit–dependent activation of MAP kinase in HMC-1 cells.

HMC-1 cells were treated with various concentrations of STI 571 for 90 minutes. Whole cell lysates were immunoblotted with an antibody specific for phospho-MAP kinase. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with an antibody for total p44 and p42 MAP kinase. The arrows indicate the locations of p44 and p42 MAP kinase. Representative results from 1 of 8 independent experiments are shown.

STI 571 inhibits c-kit–dependent activation of MAP kinase in HMC-1 cells.

HMC-1 cells were treated with various concentrations of STI 571 for 90 minutes. Whole cell lysates were immunoblotted with an antibody specific for phospho-MAP kinase. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with an antibody for total p44 and p42 MAP kinase. The arrows indicate the locations of p44 and p42 MAP kinase. Representative results from 1 of 8 independent experiments are shown.

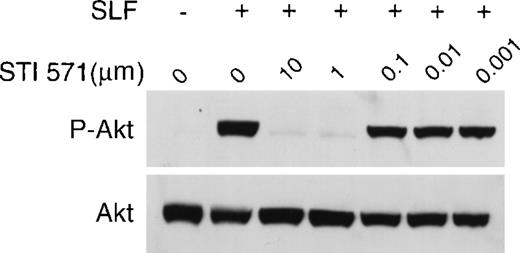

STI 571 inhibits c-kit–dependent activation of Akt

SLF-dependent activation of the c-kit receptor results in activation of phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K).55,57 One of the downstream events of the PI3K signal-transduction cascade is phosphorylation and resultant activation of the proto-oncogene Akt.58 To assess the effect of STI 571 on this pathway, we probed lysates from M-07e cells treated with SLF (with and without STI 571) with an antibody specific for the activated (phosphorylated) form of Akt. At doses ranging from 1.0 to 10 μmol/L, STI 571 markedly inhibited SLF-dependent Akt phosphorylation (Figure6). Partial inhibition of Akt activation occurred at a dose of 0.1 μmol/L STI 571. The kinase inhibitor had no effect on the expression of total Akt protein (Figure 6). Thus, STI 571 inhibited SLF-dependent activation of Akt but not expression of total Akt protein.

STI 571 inhibits SLF-dependent activation of Akt.

Whole cell lysates of M-07e cells were prepared and immunoblotted with a polyclonal antibody specific for Akt protein that had been activated by phosphorylation of serine 473. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with an antibody to total Akt. Representative results from 1 of 8 independent experiments are shown.

STI 571 inhibits SLF-dependent activation of Akt.

Whole cell lysates of M-07e cells were prepared and immunoblotted with a polyclonal antibody specific for Akt protein that had been activated by phosphorylation of serine 473. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with an antibody to total Akt. Representative results from 1 of 8 independent experiments are shown.

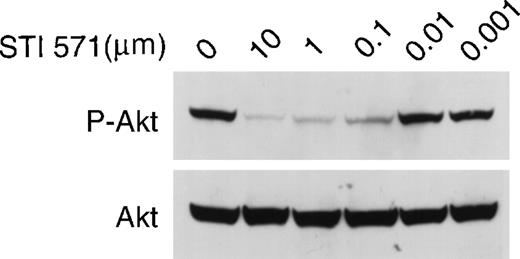

To test whether STI 571 could inhibit mutant c-kit receptor activation of the signal-transduction pathways leading to Akt, we performed similar studies using HMC-1 cells. STI 571 in doses ranging from 0.1 to 10 μmol/L strongly inhibited Akt phosphorylation (Figure7). In contrast, no inhibition occurred at a dose of 0.01 μmol/L. STI 571 had no effect on the expression of total Akt protein (Figure 7). Therefore, the observed decrease in phosphorylated Akt protein was found to be a result of inhibition of Akt activation and not due simply to an effect on total cellular Akt expression. Thus, we conclude that STI 571 inhibition of mutant c-kit kinase activity blocks both MAP kinase activation and Akt activation.

STI 571 inhibits c-kit–dependent activation of Akt in HMC-1 cells.

Whole cell lysates of M-07e cells were prepared and immunoblotted with a polyclonal antibody specific for Akt protein that had been activated by phosphorylation of serine 473. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with an antibody to total Akt. Representative results from 1 of 8 independent experiments are shown.

STI 571 inhibits c-kit–dependent activation of Akt in HMC-1 cells.

Whole cell lysates of M-07e cells were prepared and immunoblotted with a polyclonal antibody specific for Akt protein that had been activated by phosphorylation of serine 473. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with an antibody to total Akt. Representative results from 1 of 8 independent experiments are shown.

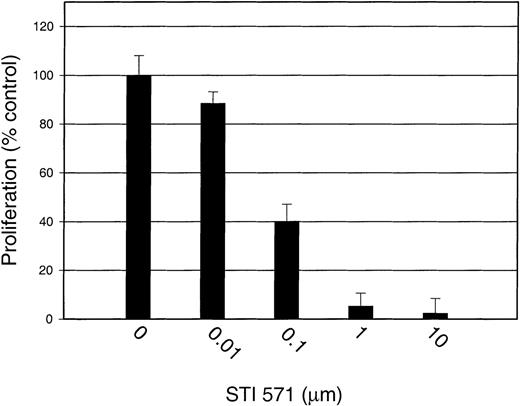

STI 571 inhibits c-kit–dependent proliferation but not GM-CSF receptor–dependent proliferation

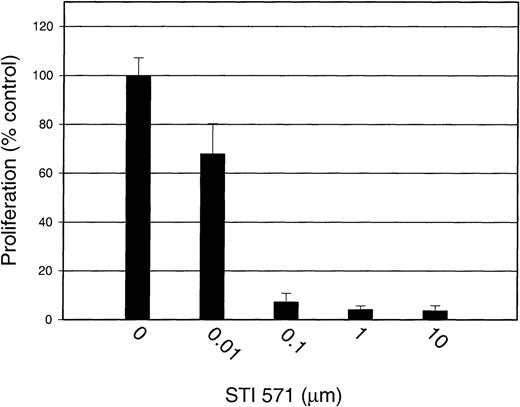

Proliferation assays were conducted to study the effect of STI 571 on both SLF-dependent and GM-CSF–dependent proliferation of M-07e cells. At inhibitor concentrations of 10 and 1.0 μmol/L, SLF-induced proliferation was significantly decreased, by 97.6% ± 6.0% and 94.7% ± 5.3%, respectively, compared with that of cells treated with SLF but not STI 571 (Figure8). With 0.1 μmol/L STI 571, cellular proliferation was reduced by 59.9% ± 7.0%, and with 0.01 μmol/L, proliferation was decreased by 11.5% ± 4.8%. The decrease in proliferation in the presence of 0.1 to 10 μmol/L inhibitor was significant (P ≤ .001).

STI 571 inhibits SLF-dependent proliferation of M-07e cells.

Serum was withheld from M-07e cells overnight before they were used in proliferation assays. Cells were plated in a 96-well plate at a concentration of 50 000 cells/well and grown in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% fetal-calf serum (FCS) with and without 200 ng/mL SLF. STI 571 was added at the same time as SLF. Proliferation at 48 hours was measured with an XTT-based assay system. Results are expressed as the percentage of maximal proliferation (SLF only) (± SD). Representative results from 1 of 6 independent experiments are shown.

STI 571 inhibits SLF-dependent proliferation of M-07e cells.

Serum was withheld from M-07e cells overnight before they were used in proliferation assays. Cells were plated in a 96-well plate at a concentration of 50 000 cells/well and grown in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% fetal-calf serum (FCS) with and without 200 ng/mL SLF. STI 571 was added at the same time as SLF. Proliferation at 48 hours was measured with an XTT-based assay system. Results are expressed as the percentage of maximal proliferation (SLF only) (± SD). Representative results from 1 of 6 independent experiments are shown.

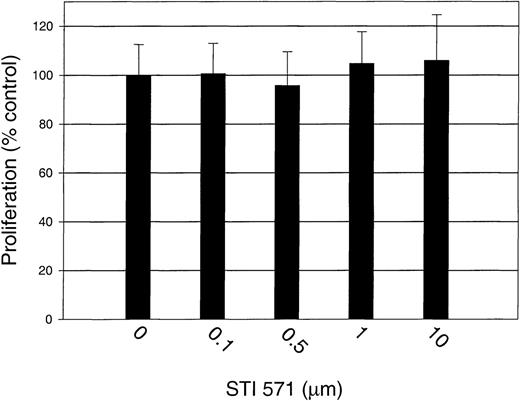

To test the specificity of STI 571 further, we measured the proliferation of GM-CSF–stimulated M-07e cells in the presence and absence of STI 571. Proliferation was not significantly affected by the addition of STI 571, even at a dose of 10 μmol/L (Figure9).Thus, we demonstrated that STI 571 selectively inhibits SLF-dependent but not GM-CSF–dependent proliferation of M-07e cells.

STI 571 has no effect on GM-CSF–dependent proliferation of M-07e cells.

Serum was withheld from M-07e cells overnight before they were used in proliferation assays. Cells were plated in a 96-well plate at a concentration of 50 000 cells/well and grown in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FCS with and without 200 U/mL GM-CSF. STI 571 was added at the same time as GM-CSF. Proliferation at 48 hours was measured with an XTT-based assay system. Results are expressed as the percentage of maximal proliferation (GM-CSF only) (± SD). Representative results from 1 of 2 independent experiments are shown.

STI 571 has no effect on GM-CSF–dependent proliferation of M-07e cells.

Serum was withheld from M-07e cells overnight before they were used in proliferation assays. Cells were plated in a 96-well plate at a concentration of 50 000 cells/well and grown in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FCS with and without 200 U/mL GM-CSF. STI 571 was added at the same time as GM-CSF. Proliferation at 48 hours was measured with an XTT-based assay system. Results are expressed as the percentage of maximal proliferation (GM-CSF only) (± SD). Representative results from 1 of 2 independent experiments are shown.

To test the biologic effect of inhibiting the kinase activity of a mutant c-kit receptor, we cultured HMC-1 cells for 48 hours in the presence of various concentrations of STI 571. At inhibitor concentrations of 0.1 to 10 μmol/L, proliferation was decreased by 90% to 95% compared with results in cells treated with medium only (Figure 10). Partial inhibition of proliferation occurred at a dose of 0.01 μmol/L STI 571, and no inhibition was observed at a dose of 0.001 μmol/L (data not shown). The decrease in proliferation with doses of 0.01 to 10 μmol/L inhibitor was significant (P < .001). Therefore, these experiments showed that STI 571 inhibits proliferation of HMC-1 cells with the same dose-response range observed for inhibition of receptor autophosphorylation, MAP kinase activation, and Akt activation.

STI 571 inhibits proliferation of HMC-1 cells.

HMC-1 cells were plated in 96-well plates at a concentration of 20 000 cells/well and cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FCS with and without various concentrations of STI 571. Cellular proliferation at 48 hours was measured with an XTT-based assay system. Results are expressed as the percentage of maximal proliferation (cells only; no STI 571) (± SD). Representative results from 1 of 6 independent experiments are shown.

STI 571 inhibits proliferation of HMC-1 cells.

HMC-1 cells were plated in 96-well plates at a concentration of 20 000 cells/well and cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FCS with and without various concentrations of STI 571. Cellular proliferation at 48 hours was measured with an XTT-based assay system. Results are expressed as the percentage of maximal proliferation (cells only; no STI 571) (± SD). Representative results from 1 of 6 independent experiments are shown.

STI 571 abrogates the antiapoptotic effect of c-kit activation

The effects of SLF on hematopoietic progenitors are both mitogenic and antiapoptotic.59,60 The mechanism by which c-kit activation prevents apoptosis is unknown but may involve PI3K-dependent activation of Akt.61 62 In our proliferation assays, we observed not only a decrease in proliferation but also morphologic features consistent with cellular death (data not shown). Because of these morphologic observations and our earlier finding that STI 571 inhibited SLF-dependent activation of Akt, we hypothesized that STI 571 would block the antiapoptotic effects of SLF.

To test our hypothesis, we withheld serum and growth factor from M-07e cells for 24 hours before treating the cells with either complete medium (10% FCS and GM-CSF), RPMI and 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) with and without SLF (200 ng/mL), or RPMI, 1% BSA, and SLF, and various doses of STI 571. Apoptosis was assessed 24 and 48 hours later by using a flow cytometric assay to measure cellular binding of an annexin V–FITC conjugate, as well as uptake of the vital stain 7-AAD.42 Consistent with findings of previous studies,38 the M-07e cells underwent apoptosis after removal of specific hematopoietic growth factors (Table1). Apoptosis could be prevented by adding GM-CSF or SLF. However, simultaneous addition of SLF and STI 571 at doses of 10 or 1 μmol/L resulted in abrogation of the antiapoptotic effect of SLF. The addition of STI 571 at a dose of 0.1 μmol/L had no effect on the ability of SLF to prevent apoptosis.

Effect of STI 571 on the antiapoptotic effect of Steel factor (SLF) on M-07e cells

| Condition . | Early apoptosis (% of stained cells) . | Late apoptosis (% of stained cells) . |

|---|---|---|

| 10% fetal-calf serum (FCS) + GM-CSF | 4.4 | 1.8 |

| 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) | 18.9 | 11.9 |

| SLF | 10.4 | 4.5 |

| SLF + 10 μmol/L STI 571 | 20.8 | 12.2 |

| SLF + 1 μmol/L STI 571 | 20.5 | 11.3 |

| SLF + 0.1 μmol/L STI 571 | 10.8 | 4.5 |

| Condition . | Early apoptosis (% of stained cells) . | Late apoptosis (% of stained cells) . |

|---|---|---|

| 10% fetal-calf serum (FCS) + GM-CSF | 4.4 | 1.8 |

| 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) | 18.9 | 11.9 |

| SLF | 10.4 | 4.5 |

| SLF + 10 μmol/L STI 571 | 20.8 | 12.2 |

| SLF + 1 μmol/L STI 571 | 20.5 | 11.3 |

| SLF + 0.1 μmol/L STI 571 | 10.8 | 4.5 |

GM-CSF indicates granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Serum and growth factor were withheld from M-07e cells for 24 hours before the cells were treated with either complete medium (10% FCS and GM-CSF), RPMI and 1% BSA with and without SLF (200 ng/mL), or RPMI, 1% BSA, and SLF, and various doses of STI 571. Apoptosis at 48 hours was assessed by using a flow cytometric assay to measure cellular binding of a conjugate of annexin V and fluorescein isothiocyanate, conjugated (FITC), as well as uptake of the vital stain 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD). A total of 10 000 cells were analyzed for each condition. Results are expressed as the percentage of cells that stained positively for annexin V-FITC only (early apoptosis) or for both annexin V-FITC and 7-AAD (late apoptosis). Representative results from 1 of 3 independent experiments are shown.

HMC-1 cells treated with STI 571 underwent morphologic changes consistent with cellular death. To test whether STI 571 was inducing programmed cell death in these cells, we treated the HMC-1 cells for 72 hours with various doses of inhibitor. Apoptosis was assessed with a flow cytometric assay as described above. In doses of 1 to 10 μmol/L, STI 571 potently induced apoptosis in HMC-1 cells. A less potent effect was observed at a dose of 0.1 μmol/L (Table2), and there was no effect on apoptosis at a dose of 0.01 μmol/L. We conclude that the survival and proliferation of HMC-1 cells depends on the kinase activity of the mutant c-kit polypeptide.

Effect of STI 571 on apoptosis in HMC-1 cells

| Condition . | Early apoptosis (% of stained cells) . | Late apoptosis (% of stained cells) . |

|---|---|---|

| Medium only | 3.6 | 5.7 |

| 10 μmol/L STI 571 | 52.7 | 31.9 |

| 1 μmol/L STI 571 | 63.7 | 32.0 |

| 0.1 μmol/L STI 571 | 30.7 | 13.2 |

| 0.01 μmol/L STI 571 | 4.9 | 4.3 |

| Condition . | Early apoptosis (% of stained cells) . | Late apoptosis (% of stained cells) . |

|---|---|---|

| Medium only | 3.6 | 5.7 |

| 10 μmol/L STI 571 | 52.7 | 31.9 |

| 1 μmol/L STI 571 | 63.7 | 32.0 |

| 0.1 μmol/L STI 571 | 30.7 | 13.2 |

| 0.01 μmol/L STI 571 | 4.9 | 4.3 |

HMC-1 cells were grown in RPMI-1640 and 10% FCS with and without various concentrations of STI 571. Apoptosis at 72 hours was assessed by using a flow cytometric assay to measure cellular binding of an annexin V–FITC conjugate, as well as uptake of the vital stain 7-AAD. A total of 10 000 cells were analyzed for each condition. Results are expressed as the percentage of cells that stained positively for annexin V-FITC only (early apoptosis) or for both annexin V-FITC and 7-AAD (late apoptosis). Representative results from 1 of 4 independent experiments are shown.

Discussion

STI 571 was identified previously as a potent inhibitor of the c-abl protein kinase and shown to have similar activity against v-abl and both the p210 and p190 forms of bcr-abl.31,63,64Additionally, STI 571 was found to inhibit the kinase activity of the α and β chains of PDGFR.30,31,64 Experiments using cell-based assay systems revealed that the IC50 for inhibition of these enzymes was 0.2 to 0.3 μmol/L. The selectivity of STI 571 was confirmed by testing its activity against a panel of protein kinases. For example, the IC50 was above 100 μmol/L for the kinase activity of epidermal growth factor receptor, fibroblast growth factor receptor, insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor, v-src, c-fgr, c-lyn, v-fms, protein kinase A, various protein kinase C isoforms, casein kinases 1 and 2, and cdc2.30,31In murine xenograft models of human CML, STI 571 was confirmed to have significant antitumor activity, with minimal toxicity.31Currently, this compound is being evaluated in clinical trials for the treatment of CML.32 33

In our studies of cells expressing wild-type c-kit protein, we found that STI 571 potently inhibited the activity of c-kit kinase activity, resulting in inhibition of autophosphorylation. Inhibition of receptor kinase activity markedly decreased activation of MAP kinase and a PI3K-dependent enzyme (Akt). STI 571 had no effect on total cellular expression of c-kit, Erk-1, Erk-2, or Akt. Treatment of M-07e cells with STI 571 inhibited SLF-dependent but not GM-CSF–dependent proliferation and abrogated the antiapoptotic activity of SLF (but not GM-CSF). The IC50 for these effects was about 100 nmol/L, which is similar to the IC50 of 100 to 300 nmol/L observed with use of bcr-abl or PDGFR as a target.

Because of its structure, c-kit is classified as a type III receptor tyrosine kinase. All members of this family have an extracellular domain containing 5 immunoglobulin-like domains, a single transmembrane domain, and a cytoplasmic domain with a split kinase domain and a hydrophilic kinase insert sequence.17 The juxtamembrane and kinase domains of these receptors are strongly conserved.35Interestingly, STI 571 can inhibit the kinase activity of c-kit, PDGFRα, and PDGFRβ but has no effect on the kinase activity of the related receptor tyrosine kinases c-fms and flk2/flt3 (data not shown).31,64 65

c-kit has been implicated in the pathophysiologic mechanisms of a variety of human tumors, including mastocytosis and mast cell leukemia, testicular cancer, small-cell lung cancer, GIST, AML, neuroblastoma, melanoma, and breast cancer. Two general mechanisms of c-kit activation in malignant cells have been described: (1) autocrine or paracrine stimulation of the receptor by SLF, and (2) acquisition of activating mutations.8,21-23,26-28 66-69

Autocrine or paracrine stimulation of c-kit has been observed in some human cancers, including neuroblastoma and small-cell lung cancer.20,21,28 Experimental approaches to demonstrating the role of the SLF–c-kit axis in cancer cell biology have been hampered by the lack of a specific way to inhibit c-kit signal transduction. Previous studies used reagents such as the tyrphostins AG1295 and AG1296 to inhibit c-kit kinase activity. These studies, however, were limited by the poor solubility of these compounds in cell culture media and by variable specificity.29,34 Other approaches for inhibiting c-kit experimentally included use of antisense oligonucleotides, transfection of dominant negative c-kit constructs, and antibodies that neutralize the c-kit ligand-binding site. The first 2 techniques are limited by delivery efficiency and the inability to totally inhibit c-kit expression or activity.20,70,71 Use of neutralizing antibodies is constrained by the binding affinity of the antibody. Additionally, autocrine stimulation of receptor by its cognate ligand can, at least in some cases, occur intracellularly and thus cannot be inhibited by extracellular antibody.72 In this study, we found that STI 571 specifically inhibits c-kit, in addition to its previously reported effects on PDGFR, c-abl, v-abl, and bcr-abl. Thus, this compound may be useful in vitro for defining the role of the SLF–c-kit axis in tumor cell proliferation.

Activating mutations of c-kit have been described in cases of human mast cell disorders, seminoma, and GIST.22,23,46,47,73 For mast cell disorders and GIST, the presence of the c-kit mutation, the type of mutation, or both, has clinical prognostic importance.24,46,73,74 Interestingly, these tumors arise in tissue types (mast cells, germ cells, and ICC) whose development depends on the activity of the SLF–c-kit axis. Indeed, these cells are absent in mice with inactivating mutations of either SLF or c-kit.5,13,14 75 The development of tumors in these tissues may require either mutation of c-kit or an alternative way to activate the downstream effectors of c-kit signal transduction.

Pharmacologic inhibition of c-kit is a potential novel approach to treatment of malignancies that are partly or completely dependent on the activity of an activated c-kit receptor. Although current medical treatments for seminoma are curative for most patients, there are no effective medical treatments for patients with advanced mast cell disease or recurrent or metastatic GIST.76,77 Indeed, a 1999 retrospective review of chemotherapy for GIST found a response rate of less than 10%.78

We used the HMC-1 cell line to test the ability of STI 571 to inhibit the kinase activity of a mutant form of c-kit. This factor-independent cell line was originally derived from a patient with mast cell leukemia and expresses a constitutively activated c-kit protein.37 40 In our studies, STI 571 potently inhibited receptor autophosphorylation, MAP kinase activation, and Akt activation without affecting levels of c-kit, Erk-1, Erk-2, or Akt. Additionally, doses of 0.01 to 10 μmol/L STI 571 inhibited HMC-1 cellular proliferation. HMC-1 cells appear to be strongly dependent on the activity of the mutant receptor to prevent apoptosis, since 85% to 95% of cells exposed to 1 to 10 μmol/L STI 571 for 48 to 72 hours underwent programmed cell death. The IC50 for induction of apoptosis was approximately 0.1 μmol/L. Thus, STI 571 can potently inhibit the kinase activity of the mutant c-kit polypeptide expressed by HMC-1 cells. The effect of STI 571 on receptor activation was even more potent than that observed when the wild-type c-kit receptor was used as a target. It is unknown whether this particular c-kit mutation actually increases the sensitivity of the kinase domain to inhibition by the compound or whether the observed differences in kinase sensitivity resulted from unrelated factors, such as differential cellular uptake of the compound.

On the basis of these studies, we propose that STI 571 may be useful for treatment of malignancies that are completely or partly dependent on the activity of wild-type or mutant c-kit for proliferation or survival. In phase I and II clinical trials of treatment of patients with CML, STI 571 was effective and well tolerated.32 33 In these trials, trough levels of 1 μmol/L were readily obtained in patients, and this level of STI 571 is an order of magnitude greater than the IC50 for inhibition of c-kit (B. Druker, unpublished data, March 2000). Further studies are warranted to determine the potential efficacy of inhibiting c-kit kinase activity as a novel strategy for treatment of human cancers.

Acknowledgment

We thank Michael Moody for his help in preparing figures.

Supported by a Merit Review Grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs (M.C.H.).

Reprints:Michael C. Heinrich, R&D–19, 3710 SW US Veterans Hospital Road, Portland, OR 97207; e-mail: heinrich@ohsu.edu.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.