Abstract

Post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD) is associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). Quantitative and qualitative differences in EBV in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of PTLD patients and healthy controls were characterized. A quantitative competitive polymerase chain reaction (QC-PCR) technique confirmed previous reports that EBV load in PBMCs is increased in patients with PTLD in comparison with healthy seropositive controls (18 539 vs 335 per 106 PBMCs, P = .0002). The average frequency of EBV-infected cells was also increased (271 vs 9 per 106 PBMCs, P = .008). The distribution in numbers of viral genome copies per cell was assessed by means of QC-PCR at dilutions of PBMCs. There was no difference between PTLD patients and healthy controls. Similarly, no differences in the patterns of viral gene expression were detected between patients and controls. Finally, the impact of therapy on viral load was analyzed. Patients with a past history of PTLD who were disease-free (after chemotherapy or withdrawal of immunosuppression) at the time of testing showed viral loads that overlapped with those of healthy seropositive controls. Patients treated with rituximab showed an almost immediate and dramatic decline in viral loads. This decline occurred even in patients whose PTLD progressed during therapy. These results suggest that the increased EBV load in PBMCs of PTLD patients can be accounted for by an increase in the number of infected B cells in the blood. However, in terms of viral copy number per cell and pattern of viral gene expression, these B cells are similar to those found in healthy controls. Disappearance of viral load with rituximab therapy confirms the localization of viral genomes in PBMCs to B cells. However, the lack of relationship between the change in viral load and clinical response highlights the difference between EBV-infected PBMCs and neoplastic cells in PTLD.

Introduction

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a widespread gamma herpesvirus associated with several human malignancies, including nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Burkitt's lymphoma, Hodgkin's disease, and post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD).1-4 In the blood of healthy carriers, the presence of EBV-infected cells can be demonstrated by the spontaneous outgrowth of EBV-immortalized lymphocytes or by polymerase chain reaction (PCR).5,6 Cell fractionation studies show that the PCR-positive population of cells are resting, memory B lymphocytes.7,8 Reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) studies show that these infected cells express a highly restricted set of viral latency genes.9-11 In contrast, in vitro EBV-immortalized lymphoblastoid cells (LCLs) proliferate and express the full set of viral latency genes.12 Thus, the population of infected lymphocytes in healthy carriers is very different from LCLs immortalized in vitro. The absence of a population of immortalized LCLs in healthy carriers is thought to reflect immune surveillance.9

PTLD is an EBV-associated process that occurs in organ and bone marrow transplant recipients as a complication of immunosuppression. Tumor cells often express the full set of viral latency antigens, paralleling the pattern of viral gene expression in LCLs.13 Several groups have reported that EBV loads in the peripheral blood lymphocytes of patients with PTLD are increased at the onset of disease and that viral loads fall with effective treatment.14-18 In the studies described here, we investigated the character of EBV-infected peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in patients with PTLD and in healthy controls. We also assessed the impact of therapy with the humanized anti-CD20 antibody rituximab on viral load and the relationship between viral load and tumor progression.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patients and healthy controls

PTLD patients were seen at the Johns Hopkins Hospital and The Ohio State University. All patients were EBV seropositive prior to transplantation. Patients were described as having either active PTLD or PTLD in remission according to whether physical examination and imaging showed evidence of disease at the time of analysis. The transplanted organ, histology of the tumor, and other clinical information are summarized in Table 1. Healthy controls were platelet donors known to be EBV+ by serology whose leukopheresis products were collected under a human investigations committee–approved protocol.

Summary of patient information

| Patient . | Age . | Race . | Sex . | Transplant . | Days (transplantation to tumor) . | Tumor histology . | Therapy for tumor* . | Time of analysis† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 44 | W | F | Liver | 3110 | Diffuse immunoblastic lymphoma (B cell), EBV+ | XRT, CHOP | Active PTLD |

| P2 | 44 | W | M | Kidney | 2224 | Diffuse large-cell lymphoma (B cell), EBV+ | Withdrawal of immunosuppression | Active PTLD |

| P3 | 48 | W | M | N/A | N/A | Polymorphic B-cell hyperplasia, EBV+ | Withdrawal of immunosuppression | Active PTLD |

| P4 | 48 | W | M | Heart | 2370 | Polymorphic B-cell hyperplasia, EBV+ | CHOP, Etoposide-Ifosfamide | Active PTLD |

| P5 | 49 | W | F | Lung | 190 | Diffuse large-cell lymphoma (B cell), EBV+ | Withdrawal of immunosuppression | Active PTLD |

| P6 | 20 | W | M | Kidney | 1106 | Diffuse immunoblastic lymphoma (B cell), EBV+ | Withdrawal of immunosuppression | Active PTLD |

| P7 | 10 | W | M | Liver | 2920 | Atypical polymorphous lymphoid hyperplasia (B cell), EBV+ | Cytoxan, prednisone | Active PTLD |

| P8 | 34 | W | F | Heart | 2824 | Diffuse large-cell lymphoma (T cell), EBV+ | CHOP, XRT, CVP, EPOCH | Active PTLD |

| P9 | 25 | W | M | Bone marrow | 121 | Diffuse immunoblastic lymphoma (B cell), EBV+ | Donor lymphocyte infusion | Remission |

| P10 | 54 | W | M | Liver | 1992 | Diffuse large-cell lymphoma (B cell), EBV+ | CHOP | Remission |

| P11 | 34 | W | F | Heart | 317 | Diffuse large-cell lymphoma (B cell), EBV+ | ProMACE-CytaBOM | Remission |

| P12 | 61 | W | F | Lung | 106 | Diffuse large-cell lymphoma (B cell), EBV+ | ProMACE-CytaBOM | Remission |

| P13 | 4 | W | M | Liver | 974 | Diffuse small noncleaved cell lymphoma (B cell), EBV+ | Cytoxan, vincristine, ARA-C | Remission |

| P14 | 52 | W | M | Lung | 310 | Diffuse large-cell lymphoma (B cell), EBV+ | CHOP | Remission |

| Patient . | Age . | Race . | Sex . | Transplant . | Days (transplantation to tumor) . | Tumor histology . | Therapy for tumor* . | Time of analysis† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 44 | W | F | Liver | 3110 | Diffuse immunoblastic lymphoma (B cell), EBV+ | XRT, CHOP | Active PTLD |

| P2 | 44 | W | M | Kidney | 2224 | Diffuse large-cell lymphoma (B cell), EBV+ | Withdrawal of immunosuppression | Active PTLD |

| P3 | 48 | W | M | N/A | N/A | Polymorphic B-cell hyperplasia, EBV+ | Withdrawal of immunosuppression | Active PTLD |

| P4 | 48 | W | M | Heart | 2370 | Polymorphic B-cell hyperplasia, EBV+ | CHOP, Etoposide-Ifosfamide | Active PTLD |

| P5 | 49 | W | F | Lung | 190 | Diffuse large-cell lymphoma (B cell), EBV+ | Withdrawal of immunosuppression | Active PTLD |

| P6 | 20 | W | M | Kidney | 1106 | Diffuse immunoblastic lymphoma (B cell), EBV+ | Withdrawal of immunosuppression | Active PTLD |

| P7 | 10 | W | M | Liver | 2920 | Atypical polymorphous lymphoid hyperplasia (B cell), EBV+ | Cytoxan, prednisone | Active PTLD |

| P8 | 34 | W | F | Heart | 2824 | Diffuse large-cell lymphoma (T cell), EBV+ | CHOP, XRT, CVP, EPOCH | Active PTLD |

| P9 | 25 | W | M | Bone marrow | 121 | Diffuse immunoblastic lymphoma (B cell), EBV+ | Donor lymphocyte infusion | Remission |

| P10 | 54 | W | M | Liver | 1992 | Diffuse large-cell lymphoma (B cell), EBV+ | CHOP | Remission |

| P11 | 34 | W | F | Heart | 317 | Diffuse large-cell lymphoma (B cell), EBV+ | ProMACE-CytaBOM | Remission |

| P12 | 61 | W | F | Lung | 106 | Diffuse large-cell lymphoma (B cell), EBV+ | ProMACE-CytaBOM | Remission |

| P13 | 4 | W | M | Liver | 974 | Diffuse small noncleaved cell lymphoma (B cell), EBV+ | Cytoxan, vincristine, ARA-C | Remission |

| P14 | 52 | W | M | Lung | 310 | Diffuse large-cell lymphoma (B cell), EBV+ | CHOP | Remission |

EBV indicates Epstein-Barr virus; N/A, not applicable; PTLD, post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease; XRT, radiation therapy; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, prednisone; CVP, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone; EPOCH, etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone; ProMACE-CytaBOM, prednisone, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, etoposide, cytarabine, bleomycin, vincristine, and methotrexate; and cytarabine.

For more information regarding these standard chemotherapy regimens, see Lister et al.41

Active PTLD or PTLD in remission is determined on the basis of whether the patient had evidence of disease by usual clinical evidence (physical examination, computed tomography scan).

PBMCs and cell lines

PBMCs were isolated by density gradient centrifugation by means of Ficoll-Hypaque 1.077 (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) and cryopreserved immediately. In some experiments, CD19+ B cells were enriched by positive selection by means of immunomagnetic beads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway).

The following cell lines were used: Namalwa, an EBV+Burkitt's lymphoma cell line that contains 2 EBV genomes per cell20; CA46, an EBV− Burkitt's lymphoma cell line; B95.8, an EBV+ marmoset LCL; and Rael, an EBV+ Burkitt's lymphoma cell line. Cell lines were maintained in standard RPMI medium (RPMI 1640, 2 mM L-glutamine, 10 mM Hepes, 100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 10% vol/vol fetal bovine serum).

EBV load measurement

EBV load (copy number of EBV genomes in PBMCs) was determined by a quantitative competitive PCR (QC-PCR) method by means of a detection kit from BioSource International (Camarillo, CA). Briefly, cells (106 PBMCs or mixtures of EBV+ and EBV− cells) were spiked with 200 copies of the Internal Calibration Standard (ICS), a DNA sequence with flanking primer-binding sites identical to those of the EBV sequence to be detected. DNA was isolated by means of the QIAamp Blood Kit (QIAGEN Inc, Valencia, CA) and eluted in 100 μL dH2O. We used 40 μL DNA in amplification reactions. The PCR primers (5′ primer,5′-GTGGTCCGCATGTTTTGATC, including nucleotide positions 6780-6800; 3′ primer,5′-GCAACGGCTGTCCTGTTTGA, including nucleotide positions 6969-6950), one of which is biotinylated, amplify a region of the EBER1 gene that is highly conserved.21 PCR involved an initial denaturation for 2.5 minutes at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 30 seconds at 94°C, 30 seconds at 60°C, and 1 minute at 72°C, with a final extension for 15 minutes at 72°C. The PCR products were denatured and hybridized to either ICS or EBV sequence-specific probes prebound to microwells. The bound PCR products were detected by addition of a streptavidin–horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate followed by the HRP substrate, 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine. The reaction was terminated by addition of a stop solution. The optical density (OD) of microwells was then read in a 7520 Microplate Reader (Cambridge Technology, Cambridge, MA). The copy number of EBV DNA was calculated with the use of the OD of the ICS amplification product as a standard. For quantitation of viral loads greater than 5000 per sample, DNA was diluted 1:100 in dH2O, and 200 copies of ICS were added to each 100 μL of diluted DNA before PCR.

Limiting dilution DNA PCR

The frequency of EBV-infected cells was determined by PCR of serial dilutions of PBMCs. At each dilution, 8 to 24 replicates were prepared. DNA was isolated as above and amplified with primers (5′ primer,5′-CTTTAGAGGCGAATGGGCGCCA, including nucleotide positions 14 068-14 089; 3′ primer,5′-TCCAGGGCCTTCACTTCGGTCT, including nucleotide positions 14 583-14 562) for the BamH-W repeat of B95.8 EBV to give a product of 516 bp.22 Time-release PCR with AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (PerkinElmer, Norwalk, CT) was used to maximize sensitivity.23 The reaction involved an initial denaturation for 3 minutes at 95°C, followed by 60 cycles of 1 minute at 95°C, 30 seconds at 64°C, and 1 minute at 72°C, with a final extension for 15 minutes at 72°C. The PCR products were electrophoresed on a 1.8% agarose gel and transferred in 0.4 N NaOH onto a HyBond N+ membrane (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ). The membrane was hybridized with a [γ-32P]adenosine triphosphate–labeled internal oligonucleotide probe (5′-GTTGCTAGGCCACCTTCTC, including nucleotide positions 14 262-14 280) in Rapid-Hyb buffer system (Amersham) at 42°C overnight. The membrane was then washed and autoradiographed for 20 minutes.

Statistical analysis

The percentage of samples without EBV sequences as determined by PCR with the use of BamHI-W primers was plotted as a function of the input number of PBMCs. The resulting curve was fit with an empiric model of the form f(x) = 1/(1+(x/c)b), where x is the average number of PBMCs in which an EBV-infected cell can be found. This curve has a maximum of 1, a minimum of 0, and a slope of b at the “mid-effect” value of c. The mid-effect value is the input number of PBMCs per sample when the percentage of negative samples is 50%. Assuming the fitted curve approximated a Poisson probability model, we estimated the frequency of EBV-infected cells by interpolation of the best-fit curve at f(x) = 0.37.24 25 For curve fitting and estimation of the frequency of EBV-infected cells, Sigma Plot regression curve fitter software (Version 4.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used. Differences in EBV load and frequency of EBV-infected cells between patients with active PTLD and healthy carriers or patients in remission were tested by means of the Wilcoxon nonparametric test.

RT-PCR for EBV transcripts

RT-PCR primers and internal probes for EBV transcripts are listed in Table 2. Total RNA was extracted from PBMCs by means of TriZol (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD). In each case, 5 μg RNA was used as the template for amplification. Oligo d(T)16 and the GeneAmp RNA PCR kit (PerkinElmer) were used for reverse transcription and PCR. PCR was carried out by means of AmpliTaq Gold and an initial denaturation for 9.5 minutes at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 30 seconds at 94°C, 30 seconds at optimal annealing temperature, and 60 seconds at 72°C, with a final extension for 10 minutes at 72°C. PCR products were electrophoresed, transferred onto Hybond-H+ membrane, and hybridized with internal oligonucleotide probes as described above.

Oligonucleotide primers and probes used in reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction analysis

| Transcript . | Primer or probe designation . | Genome coordinates in B95.8 . | Annealing temperature . | Oligonucleotide sequence . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBER1 | 5′ primer | 6776-6795 | 58°C | 5′-AAAACATGCGGACCACCAGC | 9 |

| 3′ primer | 6648-6629 | 5′-AGGACCTACGCTGCCCTAGA | |||

| Probe | 6718-6737 | 5′-ACGGTGTCTGTGGTTGTCTT | |||

| EBNA1 | 5′ primer (Q exon) | 62440-62457 | 55°C | 5′-GTGCGCTACCGGATGGCG | 9 |

| 5′ primer (U exon) | 67483-67502 | 5′-TTAGGAAGCGTTTCTTGAGC | |||

| 3′ primer (K exon) | 107986-107967 | 5′-CATTTCCAGGTCCTGTACCT | |||

| Probe | 67544-67563 | 5′-AGAGAGTAGTCTCAGGGCAT | |||

| EBNA2 | 5′ primer | 14802-14822 | 60°C | 5′-AGAGGAGGTGGTAAGCGGTTC | 9, 26 |

| 3′ primer | 48583-48562 | 5′-TGACGGGTTTCCAAGACTATCC | |||

| Probe | 48397-48416 | 5′-TGGCGTGTGACGTGGTGTAA | |||

| LMP2A | 5′ primer | 166824-166843 | 57°C | 5′-GCAACACGACGGGAATGACG | 10 |

| 3′ primer | 131-112 | 5′-AAACACGAGGCGGCAATAGC | |||

| Probe | 62-81 | 5′-ATCCAGTATGCCTGCCTGTA | |||

| BZLF1 | 5′ primer | 102826-102807 | 58°C | 5′-GGGAGAAGCACCTCAACCTG | 26 |

| 3′ primer | 102447-102466 | 5′-TTGCTTAAACTTGGCCCGGC | |||

| Probe | 102665-102656/102530-102521 | 5′-AGCCAGAATC/CTGGAGGAAT | |||

| BLLF1 | 5′ primer | 89934-89955 | 63°C | 5′-GTGGATGTGGAACTGTTTCCAG | 26 |

| 3′ primer | 90753-90732 | 5′-CTGTATCCACCGCGGATGTCAC | |||

| Probe | 90682-90663 | 5′-AGTCCATCTCCATGGGACAA | |||

| BART | 5′ primer | 157154-157173 | 55°C | 5′-AGAGACCAGGCTGCTAAACA | 27 |

| 3′ primer | 159194-159175 | 5′-AACCAGCTTTCCTTTCCGAG | |||

| Probe | 157359-157378 | 5′-AAGACGTTGGAGGCACGCTG |

| Transcript . | Primer or probe designation . | Genome coordinates in B95.8 . | Annealing temperature . | Oligonucleotide sequence . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBER1 | 5′ primer | 6776-6795 | 58°C | 5′-AAAACATGCGGACCACCAGC | 9 |

| 3′ primer | 6648-6629 | 5′-AGGACCTACGCTGCCCTAGA | |||

| Probe | 6718-6737 | 5′-ACGGTGTCTGTGGTTGTCTT | |||

| EBNA1 | 5′ primer (Q exon) | 62440-62457 | 55°C | 5′-GTGCGCTACCGGATGGCG | 9 |

| 5′ primer (U exon) | 67483-67502 | 5′-TTAGGAAGCGTTTCTTGAGC | |||

| 3′ primer (K exon) | 107986-107967 | 5′-CATTTCCAGGTCCTGTACCT | |||

| Probe | 67544-67563 | 5′-AGAGAGTAGTCTCAGGGCAT | |||

| EBNA2 | 5′ primer | 14802-14822 | 60°C | 5′-AGAGGAGGTGGTAAGCGGTTC | 9, 26 |

| 3′ primer | 48583-48562 | 5′-TGACGGGTTTCCAAGACTATCC | |||

| Probe | 48397-48416 | 5′-TGGCGTGTGACGTGGTGTAA | |||

| LMP2A | 5′ primer | 166824-166843 | 57°C | 5′-GCAACACGACGGGAATGACG | 10 |

| 3′ primer | 131-112 | 5′-AAACACGAGGCGGCAATAGC | |||

| Probe | 62-81 | 5′-ATCCAGTATGCCTGCCTGTA | |||

| BZLF1 | 5′ primer | 102826-102807 | 58°C | 5′-GGGAGAAGCACCTCAACCTG | 26 |

| 3′ primer | 102447-102466 | 5′-TTGCTTAAACTTGGCCCGGC | |||

| Probe | 102665-102656/102530-102521 | 5′-AGCCAGAATC/CTGGAGGAAT | |||

| BLLF1 | 5′ primer | 89934-89955 | 63°C | 5′-GTGGATGTGGAACTGTTTCCAG | 26 |

| 3′ primer | 90753-90732 | 5′-CTGTATCCACCGCGGATGTCAC | |||

| Probe | 90682-90663 | 5′-AGTCCATCTCCATGGGACAA | |||

| BART | 5′ primer | 157154-157173 | 55°C | 5′-AGAGACCAGGCTGCTAAACA | 27 |

| 3′ primer | 159194-159175 | 5′-AACCAGCTTTCCTTTCCGAG | |||

| Probe | 157359-157378 | 5′-AAGACGTTGGAGGCACGCTG |

See footnote to Table 5 for explanation of abbreviations.

Patients with rituximab treatment

Five patients with active PTLD who failed conventional treatment as listed in Table 1 received 4 weekly infusions of rituximab at a dose of 375 mg/m2. Blood was drawn before treatment and once every month after the first dose of rituximab. In 2 patients, blood was also drawn once or twice per week within the first month in order to pinpoint the onset of response to rituximab. PBMCs were isolated and EBV loads measured by means of QC-PCR as described earlier.

Results

EBV load in peripheral blood

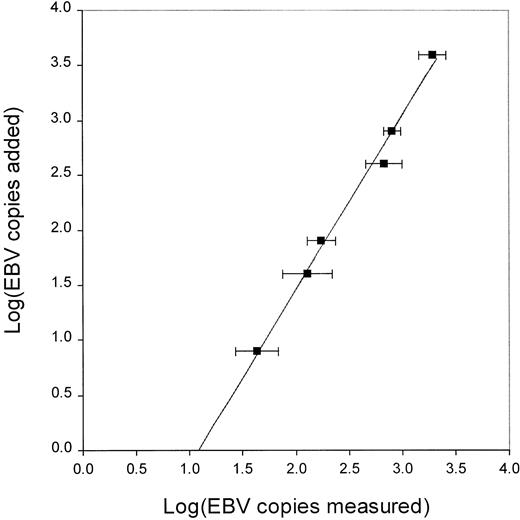

QC-PCR was used to determine EBV load (copy number of EBV genomes in PBMCs). The accuracy and reproducibility of this assay were determined by measuring the copy number of EBV genomes from mixtures of EBV+ and EBV− Burkitt's lymphoma cell lines, Namalwa and CA46, respectively. In contrast to many EBV+cell lines, there are no viral episomes in Namalwa, and thus, the copy number per cell is stable. A log-linear relationship was found between the actual and the measured copy number of EBV genomes (Figure1). Linear regression analysis yielded the standard curve, which was used for calculation of the actual copy number of EBV genomes. The curve is described by the equation: log(added-EBV) = 1.58 × log(measured-EBV) − 1.71.

Log linear relationship between measured and actual copy number of EBV genomes.

The measured copy number of EBV genomes determined by EBV QC-PCR were log linear with the actual copy number of EBV genomes. Known number of Namalwa cells (containing 2 copies of EBV genomes per cell) were mixed with EBV− CA46 cells for a total of 106 cells per aliquot. Each aliquot was spiked with 200 copies of ICS before DNA isolation and QC-PCR. Each data point represents the mean and standard deviation of 4 to 7 separate experiments over a period of 1 year. The curve was fitted by linear regression analysis and the equation for the curve is log(added-EBV) = 1.58 × log(measured-EBV) − 1.71.

Log linear relationship between measured and actual copy number of EBV genomes.

The measured copy number of EBV genomes determined by EBV QC-PCR were log linear with the actual copy number of EBV genomes. Known number of Namalwa cells (containing 2 copies of EBV genomes per cell) were mixed with EBV− CA46 cells for a total of 106 cells per aliquot. Each aliquot was spiked with 200 copies of ICS before DNA isolation and QC-PCR. Each data point represents the mean and standard deviation of 4 to 7 separate experiments over a period of 1 year. The curve was fitted by linear regression analysis and the equation for the curve is log(added-EBV) = 1.58 × log(measured-EBV) − 1.71.

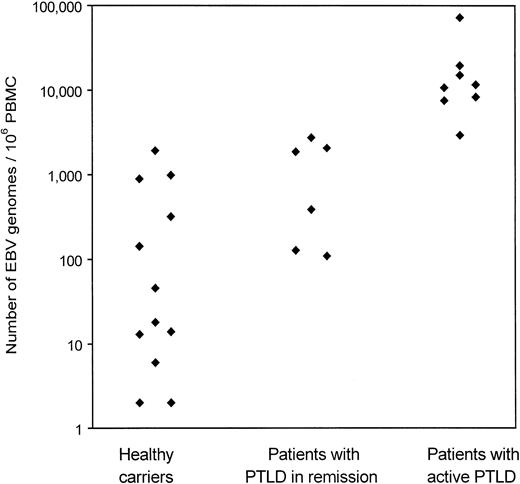

EBV load in the PBMCs of 13 healthy carriers and 14 PTLD patients was determined by EBV QC-PCR (Figure 2; Table3). Of the 14 patients, 8 had active PTLD and 6 were in remission after chemotherapy or withdrawal of immunosuppression. Viral DNA was detected in 12 of 13 healthy carriers and in each of the patients with PTLD. In healthy EBV carriers, viral load ranged from undetectable to 1921 EBV genomes per 106PBMCs (mean, 335). In patients with active PTLD, EBV load ranged from 2930 to 72 537 EBV genomes per 106 PBMCs (mean, 18 539). The difference was significant (P = .0002). In patients with PTLD in remission, EBV load ranged from 109 to 2742 EBV genomes per 106 PBMCs (mean, 1216), significantly lower than viral load in patients with active PTLD (P = .002).

Copy number of EBV genomes in peripheral blood of healthy carriers, patients with PTLD in remission, and patients with active PTLD.

DNA from 1 × 106 PBMCs spiked with 200 copies of ICS was isolated and eluted into 100 μL dH2O. For QC-PCR, 40 μL DNA was used and the EBV load measured and calculated as described in Figure 1. EBV loads in healthy carriers are the average of 6 separate experiments. DNA was isolated independently for each of these experiments.

Copy number of EBV genomes in peripheral blood of healthy carriers, patients with PTLD in remission, and patients with active PTLD.

DNA from 1 × 106 PBMCs spiked with 200 copies of ICS was isolated and eluted into 100 μL dH2O. For QC-PCR, 40 μL DNA was used and the EBV load measured and calculated as described in Figure 1. EBV loads in healthy carriers are the average of 6 separate experiments. DNA was isolated independently for each of these experiments.

Summary of Epstein-Barr virus load and frequency of Epstein-Barr virus-infected cells in peripheral blood mononuclear cells

| . | EBV genomes per 106 PBMCs . | EBV-infected cells per 106 PBMCs . |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy carriers | ||

| H1 | 1921 | 24 |

| H2 | 46 | 4 |

| H3 | 890 | 23 |

| H4 | 6 | 0.33 |

| H5 | 18 | 0.05 |

| H6 | 13 | 0.14 |

| H7 | 2 | |

| H8 | 14 | |

| H9 | ND | |

| H10 | 2 | |

| H11 | 142 | |

| H12 | 320 | |

| H13 | 985 | |

| Average | 335 | 9 |

| Patients with active PTLD | ||

| P1 | 10 711 | 266 |

| P2 | 15 073 | 254 |

| P3 | 8 320 | 119 |

| P4 | 19 579 | 684 |

| P5 | 7530 | 32 |

| P6 | 2930 | |

| P7 | 72 537 | |

| P8 | 11 633 | |

| Average | 18 539 | 271 |

| Patients with PTLD in remission | ||

| P9 | 1867 | |

| P10 | 387 | |

| P11 | 109 | |

| P12 | 128 | |

| P13 | 2742 | |

| P14 | 2065 | |

| Average | 1216 |

| . | EBV genomes per 106 PBMCs . | EBV-infected cells per 106 PBMCs . |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy carriers | ||

| H1 | 1921 | 24 |

| H2 | 46 | 4 |

| H3 | 890 | 23 |

| H4 | 6 | 0.33 |

| H5 | 18 | 0.05 |

| H6 | 13 | 0.14 |

| H7 | 2 | |

| H8 | 14 | |

| H9 | ND | |

| H10 | 2 | |

| H11 | 142 | |

| H12 | 320 | |

| H13 | 985 | |

| Average | 335 | 9 |

| Patients with active PTLD | ||

| P1 | 10 711 | 266 |

| P2 | 15 073 | 254 |

| P3 | 8 320 | 119 |

| P4 | 19 579 | 684 |

| P5 | 7530 | 32 |

| P6 | 2930 | |

| P7 | 72 537 | |

| P8 | 11 633 | |

| Average | 18 539 | 271 |

| Patients with PTLD in remission | ||

| P9 | 1867 | |

| P10 | 387 | |

| P11 | 109 | |

| P12 | 128 | |

| P13 | 2742 | |

| P14 | 2065 | |

| Average | 1216 |

EBV indicates Epstein-Barr virus; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; PTLD, post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease; ND, not detected.

Frequency of EBV-infected cells

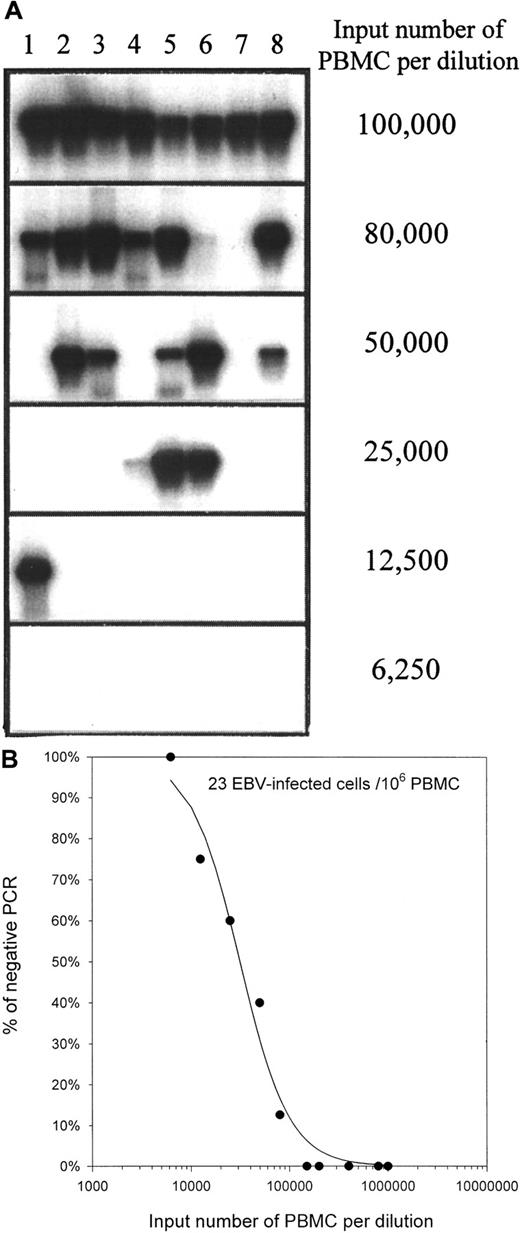

Experiments were carried out to determine whether the increased EBV load in PTLD patients reflects an increase in the frequency of EBV-infected cells or an increase in the copy number of viral genomes per infected cell. PBMCs were serially diluted; DNA was isolated; and PCR for the BamH-W sequences of the viral genome was used to determine the presence or absence of viral DNA in any particular dilution. In contrast to the EBER1 primers used for QC-PCR, the BamH-W primers amplify a region that is repeated up to 11 times in the viral genome. As a result, BamH-W PCR is more sensitive than EBER1 PCR. A representative limiting dilution DNA PCR experiment is presented in Figure 3. Poisson statistical analysis of the limiting dilution DNA PCR studies was used to approximate the frequency of EBV-infected cells in PBMCs in healthy carriers and in patients with active PTLD. The frequencies of EBV-infected cells are summarized in Table 3. Frequencies averaged 9 infected cells per 106 PBMCs (range, 0.05 to 24) in healthy controls and 271 per 106 PBMCs (range, 32 to 684) in patients with active PTLD. The difference was significant (P = .008). EBV load and the frequency of infected cells were correlated (Spearman R = 0.95; Figure 4).

Determination of the frequency of EBV-infected cells in PBMCs by limiting dilution DNA PCR on healthy carrier H3.

(A) Serial dilutions of PBMCs, 8 replicates per input number of PBMCs, were used for DNA isolation. The presence of EBV in the DNA was determined by PCR for the BamH-W region of the virus. The PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis and Southern hybridization. Lanes 1 to 8 show PCR on replicate samples from the same input number of PBMCs. (B) The percentage of negative BamH-W PCR was plotted against the input number of PBMCs. Curve fitting and Poisson analysis were performed for the estimation of the frequency of EBV-infected cells.

Determination of the frequency of EBV-infected cells in PBMCs by limiting dilution DNA PCR on healthy carrier H3.

(A) Serial dilutions of PBMCs, 8 replicates per input number of PBMCs, were used for DNA isolation. The presence of EBV in the DNA was determined by PCR for the BamH-W region of the virus. The PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis and Southern hybridization. Lanes 1 to 8 show PCR on replicate samples from the same input number of PBMCs. (B) The percentage of negative BamH-W PCR was plotted against the input number of PBMCs. Curve fitting and Poisson analysis were performed for the estimation of the frequency of EBV-infected cells.

The frequencies of EBV-infected cells.

The frequencies of EBV-infected cells show a positive correlation with viral loads in PBMCs from PTLD patients and healthy carriers. Open diamonds indicate data from 6 healthy carriers, and filled diamonds indicate data from 5 patients with active PTLD. The correlation coefficient (R) is presented.

The frequencies of EBV-infected cells.

The frequencies of EBV-infected cells show a positive correlation with viral loads in PBMCs from PTLD patients and healthy carriers. Open diamonds indicate data from 6 healthy carriers, and filled diamonds indicate data from 5 patients with active PTLD. The correlation coefficient (R) is presented.

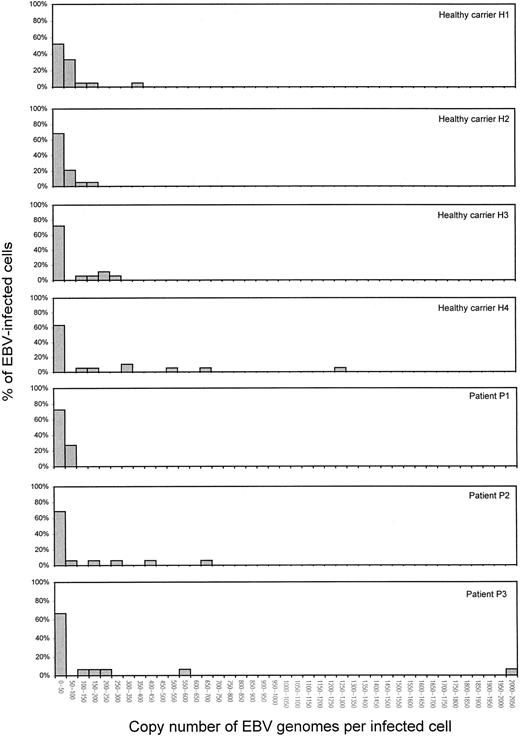

Copy number of EBV genomes per infected cell

The copy number of EBV genomes per infected cell was measured to determine whether increased copy numbers per cell contributed to the increased viral loads in patients with active PTLD. Copy numbers per cell were measured by QC-PCR at dilutions of PBMCs that were estimated to have less than 1 EBV-infected cell. Four healthy carriers and 3 patients with active PTLD were studied. At least 15 samples with detectable viral load at dilutions of PBMCs were measured for each individual. In both healthy carriers and patients with active PTLD, the majority of infected cells harbored fewer than 50 EBV genome copies per cell (Table 4). By visual inspection, the distribution of viral genomes per cell is indistinguishable between healthy donors and PTLD patients (Figure5).

Copy number of Epstein-Barr virus genomes per infected cell

| Healthy carriers . | Patients with active PTLD . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 . | H2 . | H3 . | H4 . | P1 . | P2 . | P3 . |

| 7 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 3 |

| 8 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 10 | 10 |

| 9 | 6 | 6 | 9 | 8 | 12 | 10 |

| 11 | 6 | 7 | 12 | 9 | 12 | 15 |

| 14 | 9 | 8 | 16 | 9 | 18 | 22 |

| 14 | 14 | 10 | 27 | 16 | 20 | 23 |

| 19 | 15 | 10 | 32 | 18 | 21 | 33 |

| 26 | 19 | 11 | 33 | 21 | 22 | 33 |

| 38 | 20 | 15 | 35 | 23 | 22 | 50 |

| 39 | 26 | 17 | 38 | 23 | 25 | 50 |

| 45 | 34 | 20 | 43 | 27 | 42 | 111 |

| 53 | 39 | 25 | 45 | 28 | 79 | 161 |

| 55 | 50 | 30 | 103 | 28 | 156 | 228 |

| 60 | 59 | 148 | 170 | 29 | 280 | 593 |

| 66 | 61 | 156 | 301 | 45 | 418 | 2007 |

| 69 | 68 | 224 | 331 | 46 | 660 | |

| 73 | 96 | 224 | 510 | 51 | ||

| 94 | 120 | 281 | 696 | 59 | ||

| 133 | 177 | 1263 | 63 | |||

| 199 | 67 | |||||

| 390 | 81 | |||||

| 84 | ||||||

| Healthy carriers . | Patients with active PTLD . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 . | H2 . | H3 . | H4 . | P1 . | P2 . | P3 . |

| 7 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 3 |

| 8 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 10 | 10 |

| 9 | 6 | 6 | 9 | 8 | 12 | 10 |

| 11 | 6 | 7 | 12 | 9 | 12 | 15 |

| 14 | 9 | 8 | 16 | 9 | 18 | 22 |

| 14 | 14 | 10 | 27 | 16 | 20 | 23 |

| 19 | 15 | 10 | 32 | 18 | 21 | 33 |

| 26 | 19 | 11 | 33 | 21 | 22 | 33 |

| 38 | 20 | 15 | 35 | 23 | 22 | 50 |

| 39 | 26 | 17 | 38 | 23 | 25 | 50 |

| 45 | 34 | 20 | 43 | 27 | 42 | 111 |

| 53 | 39 | 25 | 45 | 28 | 79 | 161 |

| 55 | 50 | 30 | 103 | 28 | 156 | 228 |

| 60 | 59 | 148 | 170 | 29 | 280 | 593 |

| 66 | 61 | 156 | 301 | 45 | 418 | 2007 |

| 69 | 68 | 224 | 331 | 46 | 660 | |

| 73 | 96 | 224 | 510 | 51 | ||

| 94 | 120 | 281 | 696 | 59 | ||

| 133 | 177 | 1263 | 63 | |||

| 199 | 67 | |||||

| 390 | 81 | |||||

| 84 | ||||||

PTLD indicates post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease.

Distribution of the copy number of EBV genomes per infected cell in 4 healthy carriers and 3 patients with active PTLD.

Copy numbers per cell were measured by QC-PCR at dilutions of PBMCs that were estimated to have less than one EBV-infected cell. The dilutions of PBMCs were mixed with CA46 cells so as to achieve a total cell number of 1 × 106 cells per sample. In a typical experiment on healthy carrier H3 (23 EBV-infected cells per 106 PBMCs), a dilution of 30 000 PBMCs per sample was used. The PBMCs were mixed with 9.7 × 105 CA46 cells before DNA isolation, and 17 DNA samples were measured by QC-PCR. EBV load was detected in 10 of the 17 samples, which was consistent with the percentage of PCR positivity obtained by BamH-W PCR (Figure 3). EBV genome copy numbers per cell are also shown Table 4.

Distribution of the copy number of EBV genomes per infected cell in 4 healthy carriers and 3 patients with active PTLD.

Copy numbers per cell were measured by QC-PCR at dilutions of PBMCs that were estimated to have less than one EBV-infected cell. The dilutions of PBMCs were mixed with CA46 cells so as to achieve a total cell number of 1 × 106 cells per sample. In a typical experiment on healthy carrier H3 (23 EBV-infected cells per 106 PBMCs), a dilution of 30 000 PBMCs per sample was used. The PBMCs were mixed with 9.7 × 105 CA46 cells before DNA isolation, and 17 DNA samples were measured by QC-PCR. EBV load was detected in 10 of the 17 samples, which was consistent with the percentage of PCR positivity obtained by BamH-W PCR (Figure 3). EBV genome copy numbers per cell are also shown Table 4.

RT-PCR analysis of latent and lytic EBV transcripts

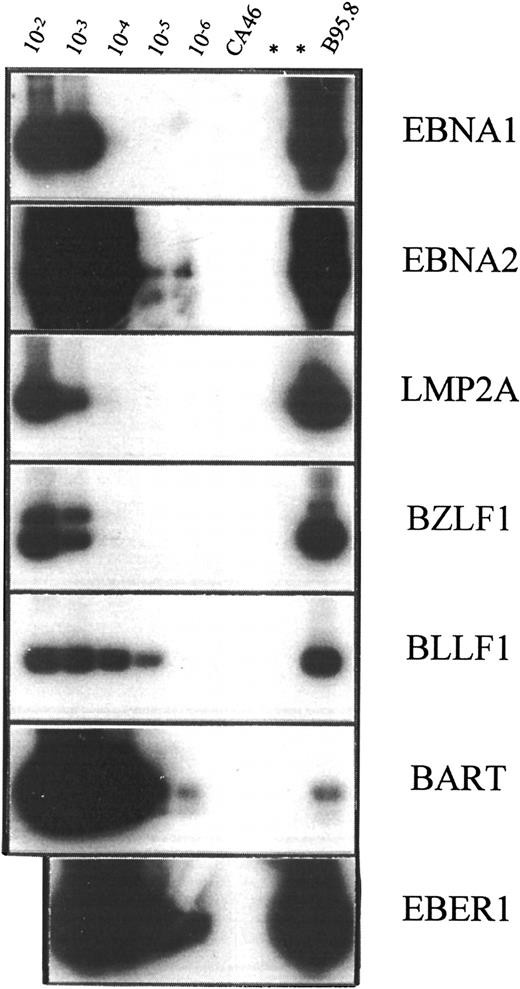

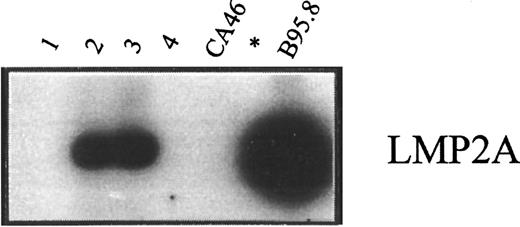

To further characterize the status of EBV infection in peripheral blood of healthy carriers and patients, latent and lytic EBV transcripts were analyzed by RT-PCR in 2 healthy carriers and 2 patients with active PTLD. EBV transcripts analyzed included Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen (EBNA) 1, EBNA2, latent membrane protein (LMP) 2A, BZLF1, BLLF1, and BART. The sensitivity of oligonucleotide primer-probe combinations used in RT-PCR analysis was determined by assay of cell mixtures containing a standard number of EBV− CA46 cells and serial 10-fold dilutions (10−2 to 10−6) of the virus-productive B95.8 cells (Figure 6; Table5). The RNA extracted from aliquots (2 × 106 cells each) of these mixed populations was analyzed by RT-PCR. Since the frequency of cells harboring EBV is increased in patients with active PTLD, PBMCs from healthy carriers were enriched for CD19+ cells in order to achieve similar frequencies of virus-infected cells in specimens from healthy carriers and in patients. About 10% of PBMCs were CD19+ B cells by immunomagnetic selection, so the frequencies of EBV-infected cells were approximately 240 and 40 per 106 CD19+ cells for healthy carriers H1 and H2, respectively. This is close to 266 and 254 per 106 PBMCs of patients P1 and P2, respectively. The pattern of viral gene expression in peripheral blood was indistinguishable between healthy carriers and those patients with active PTLD. The abundant transcript EBER1 was detected in all individuals examined. LMP2A was detected in 1 of 2 healthy carriers and 1 of 2 patients (Figure 7). However, EBNA1 and EBNA2 were not detected in any of the individuals tested, nor were the lytic transcripts BZLF1 and BLLF1. BART was detected in 1 of 2 healthy carriers and in both patients with active PTLD. Results of RT-PCR are summarized in Table 5.

Sensitivity of oligonucleotide primer-probe combinations used in RT-PCR analysis.

RT-PCR was performed on RNA extracted from mixtures of EBV− CA46 cells and serial 10-fold dilutions (10−2 to 10−6) of the virus-productive B95.8 cells. In the case of EBNA1, Rael cells were used instead of B95.8 cells. RNA was extracted from a total of 20 × 106 cells, and a fraction corresponding to 2 × 106 cells was used for each RT-PCR followed by Southern hybridization.

Sensitivity of oligonucleotide primer-probe combinations used in RT-PCR analysis.

RT-PCR was performed on RNA extracted from mixtures of EBV− CA46 cells and serial 10-fold dilutions (10−2 to 10−6) of the virus-productive B95.8 cells. In the case of EBNA1, Rael cells were used instead of B95.8 cells. RNA was extracted from a total of 20 × 106 cells, and a fraction corresponding to 2 × 106 cells was used for each RT-PCR followed by Southern hybridization.

Summary of reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction analysis on peripheral blood mononuclear cells

| . | EBV transcripts . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBER1 . | EBNA1 . | EBNA2 . | LMP2A . | BZLF1 . | BLLF1 . | BART . | |

| Sensitivity of RT-PCR | 10−6 | 10−4 | 10−6 | 10−4 | 10−4 | 10−5 | 10−6 |

| Patients with PTLD | |||||||

| P1 | + | − | − | + | − | − | + |

| P2 | + | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Healthy carriers | |||||||

| H1 | + | − | − | + | − | − | + |

| H2 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| . | EBV transcripts . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBER1 . | EBNA1 . | EBNA2 . | LMP2A . | BZLF1 . | BLLF1 . | BART . | |

| Sensitivity of RT-PCR | 10−6 | 10−4 | 10−6 | 10−4 | 10−4 | 10−5 | 10−6 |

| Patients with PTLD | |||||||

| P1 | + | − | − | + | − | − | + |

| P2 | + | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Healthy carriers | |||||||

| H1 | + | − | − | + | − | − | + |

| H2 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

RT-PCR indicates reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; PTLD, post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease.

RT-PCR analysis of LMP2A transcripts.

RT-PCR analysis was done of LMP2A transcripts in RNA preparations from enriched CD19+ cells of healthy carriers H2 and H1 (lanes 1 and 2) and from PBMCs of patients P1 and P2, both of whom had active PTLD (lanes 3 and 4). In each case, 5 μg RNA was used as the template for amplification. Positive and negative controls were RNA preparations from B95.8 and CA46 cells, respectively.

RT-PCR analysis of LMP2A transcripts.

RT-PCR analysis was done of LMP2A transcripts in RNA preparations from enriched CD19+ cells of healthy carriers H2 and H1 (lanes 1 and 2) and from PBMCs of patients P1 and P2, both of whom had active PTLD (lanes 3 and 4). In each case, 5 μg RNA was used as the template for amplification. Positive and negative controls were RNA preparations from B95.8 and CA46 cells, respectively.

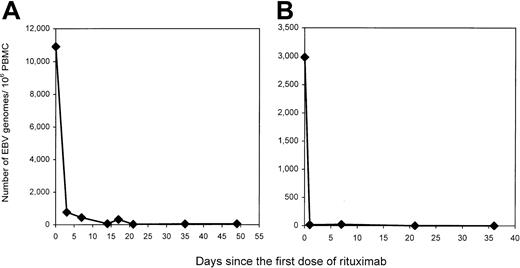

EBV load and tumor response following rituximab therapy

Monoclonal antibodies directed against B-cell markers have been used in the treatment of PTLD.28 Recently, rituximab, a monoclonal antibody targeting CD20, a pan–B-cell marker, has been available for clinical use.29-31 We followed the EBV load in PBMCs of 5 patients with active PTLD treated with rituximab. A dramatic fall in EBV load was seen after therapy in each of the patients studied (Table 6). Two patients with serial measurements in the days after therapy showed that the decline occurred within 24 to 72 hours (Figure8). The rapid disappearance of virus-infected cells is similar to that described for the disappearance of B cells from the periphery following rituximab therapy.32-34 Although all of the patients' tumors expressed CD20, tumors progressed in 3 of 5 patients, including patient P1 whose dramatic fall in viral load is illustrated in Figure 8A. Only one patient's tumor responded to therapy. Curiously, the responding patient (P4) had the highest residual EBV load following rituximab therapy. Note that patient P6 with primary central nervous system lymphoma was inevaluable for tumor response because cranial irradiation was used as the primary treatment and rituximab was used as consolidation. These results provide in vivo evidence that the increased peripheral blood viral load in PTLD patients is harbored in CD20+ cells and that these cells are readily eliminated from the circulation in patients with PTLD, even when there is clinical tumor progression.

Summary of Epstein-Barr virus loads and tumor response in post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease patients following rituximab therapy

| PTLD patients6-150 . | Number of EBV genomes per 106 PBMCs . | Tumor response . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pretreatment . | 5 weeks post-treatment . | ||

| P1 | 10 711 | 46 | Progressed |

| P2 | 15 073 | 222 | Progressed |

| P4 | 19 579 | 3 368 | Responded |

| P6 | 2 930 | 0 | —6-151 |

| P7 | 72 537 | 56-152 | Progressed |

| PTLD patients6-150 . | Number of EBV genomes per 106 PBMCs . | Tumor response . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pretreatment . | 5 weeks post-treatment . | ||

| P1 | 10 711 | 46 | Progressed |

| P2 | 15 073 | 222 | Progressed |

| P4 | 19 579 | 3 368 | Responded |

| P6 | 2 930 | 0 | —6-151 |

| P7 | 72 537 | 56-152 | Progressed |

PTLD indicates post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease; PMBC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell.

All patients had CD20+, EBV+ B-cell lymphoma.

Patient P6 was inevaluable for tumor response because radiation therapy was used as primary treatment and the rituximab was used as consolidation.

This specimen was obtained 5 months post-treatment.

Changes in EBV load in 2 patients whose tumor progressed with rituximab therapy.

Patients P1 and P6 (panels A and B), both of whom had active PTLD and failed conventional treatment, received 4 weekly infusions of rituximab at the dose of 375 mg/m2. Blood was drawn at the indicated time points and PBMCs were isolated. Viral loads were determined by QC-PCR on DNA extracted from 1 × 106PBMCs. Despite the quick decrease in peripheral blood EBV loads, PTLD tumors in both patients progressed.

Changes in EBV load in 2 patients whose tumor progressed with rituximab therapy.

Patients P1 and P6 (panels A and B), both of whom had active PTLD and failed conventional treatment, received 4 weekly infusions of rituximab at the dose of 375 mg/m2. Blood was drawn at the indicated time points and PBMCs were isolated. Viral loads were determined by QC-PCR on DNA extracted from 1 × 106PBMCs. Despite the quick decrease in peripheral blood EBV loads, PTLD tumors in both patients progressed.

Discussion

This investigation shows that an increased frequency of EBV-infected cells, rather than an increased copy number of viral genomes per infected cell, accounts for the increased viral load in the lymphocytes of patients with PTLD. Furthermore, virus-infected cells in the blood of PTLD patients are indistinguishable from those in healthy carriers and differ from LCL-like lymphoblasts in terms of viral gene expression. In addition, in patients with PTLD, a fall in EBV load does not predict clinical response following rituximab therapy.

EBV load has been measured by PCR-based assays by several investigators. These methods include quantitative-competitive PCR (QC-PCR),14,15 semiquantitative PCR,16-18,35,36 and real-time PCR.37-39 Using these techniques, groups of investigators measured EBV load in PTLD patients and in healthy carriers. Their reports all demonstrate increased viral load in patients, but there is striking variability in absolute values across studies (Table 7). The QC-PCR strategy was selected in the current study because it allows the test sample to be co-amplified in the same PCR reactions with a competitor DNA, thus permitting sample, primer pair, and target sequence variation to be internally controlled. Our method differs from the QC-PCR approach used by 2 other groups14 15 in that rather than using series of increasing quantities of competitor DNA, we used a fixed quantity of competitor DNA for co-amplification followed by comparison with a standard curve. The approach used here requires less material and yields a continuous measure. EBV load in patients with PTLD and in healthy carriers reported in this study is similar to what was reported by 2 other groups that used QC-PCR and the group that used real-time PCR. This study confirmed previous reports that PTLD is associated with an increased viral load in PBMCs.

Summary of publications on Epstein-Barr virus load in healthy carriers and patients with post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease

| PCR method . | Copy number of EBV genomes per 106PBMCs7-150 . | Reference . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy carriers . | Patients with PTLD . | ||

| Quantitative competitive | ND to 1921 (13/13) | 2930 to 72 537 (8/8) | Current study |

| Quantitative competitive | ND to 20 (10/10) | 5000 to > 250 000 (13/14), 200 (1/14) | 14 |

| Quantitative competitive | — | 3000 to 40 000 (7/7) | 15 |

| Semiquantitative | ND to 25 (4/4) | 5000 to 5 000 000 (10/10) | 16 |

| Semiquantitative | 200 to 20 000 (10/10) | > 200 000 (5/7), < 20 000 (2/7) | 18 |

| Semiquantitative | ND to 5 (16/16) | N/A | 32 |

| Semiquantitative | ND (5/10), 20 000 to 1 000 000 (5/10) | N/A | 33 |

| Real-time | ND to 675 (13/13) | 2890 to 134 455 (5/5) | 34 |

| PCR method . | Copy number of EBV genomes per 106PBMCs7-150 . | Reference . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy carriers . | Patients with PTLD . | ||

| Quantitative competitive | ND to 1921 (13/13) | 2930 to 72 537 (8/8) | Current study |

| Quantitative competitive | ND to 20 (10/10) | 5000 to > 250 000 (13/14), 200 (1/14) | 14 |

| Quantitative competitive | — | 3000 to 40 000 (7/7) | 15 |

| Semiquantitative | ND to 25 (4/4) | 5000 to 5 000 000 (10/10) | 16 |

| Semiquantitative | 200 to 20 000 (10/10) | > 200 000 (5/7), < 20 000 (2/7) | 18 |

| Semiquantitative | ND to 5 (16/16) | N/A | 32 |

| Semiquantitative | ND (5/10), 20 000 to 1 000 000 (5/10) | N/A | 33 |

| Real-time | ND to 675 (13/13) | 2890 to 134 455 (5/5) | 34 |

PCR indicates polymerase chain reaction; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; PTLD, post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease; ND, not detected.

Data from original papers are normalized to copy number of Epstein-Barr virus genomes per 106 PBMCs for comparison. In studies where the original data are presented as copy number per 106 B cells or copy number per μg DNA, the values are normalized by estimating that B cells account for 10% of PBMCs or that 1 μg DNA corresponds to 0.2 × 106 PBMCs, respectively. Fractions in parentheses represent number of cases within that range (nominator) and total number of cases measured (denominator).

The increased EBV load might reflect an increase in the number of EBV-infected cells, an increase in the copy number of EBV genomes per infected cell, or both. By limiting dilution DNA PCR, we show that the frequencies of EBV-infected cells are increased in the blood of patients with PTLD. In fact, the frequencies of virally infected cells correlate nicely with EBV loads (Figure 4). This is consistent with recent findings of Babcock et al.40 In a similar analysis, they reported 1 to 43, and 4 to 1670 EBV-infected cells per 106 B cells in healthy controls and immunosuppressed patients. Others have reported that the rate of spontaneous LCL outgrowth also increased in the blood of PTLD patients.41

The findings of increased EBV load and increased frequency of EBV-infected cells in the blood of PTLD patients lead to the question of whether the copy number of EBV genomes per cell differs in healthy seropositive individuals and in patients with PTLD. Our data show that the distribution of copy number per cell is indistinguishable between patients with PTLD and healthy carriers (Table 2; Figure 5). Most EBV-infected cells in patients as well as healthy seropositive individuals carry fewer than 50 EBV genomes per cell. Thus, the increased peripheral blood EBV load in patients with PTLD cannot be accounted for by an increased number of viral genomes per infected cell.

RT-PCR analysis showed no difference in the pattern of viral gene expression between healthy carriers and patients with PTLD, with LMP-2A being the only protein-coding transcript detected. Failure to detect other transcripts is unlikely to be a sensitivity issue in that our RT-PCR controls detected 1 positive cell among 104 to 106 negative cells while the lowest frequency of EBV-infected cells in our test samples for RT-PCR is approximately 1 in 104 cells. This pattern of expression is different from viral gene expression of LCLs, which express the full spectrum of EBV latent cycle antigens, namely, the EBNAs 1, 2, 3A, 3B, 3C, -LP, and LMPs 1, 2A, and 2B.12

Thus. EBV-infected cells in peripheral blood of patients with PTLD carry, in general, fewer than 50 copies of viral genomes per cell, express a highly restricted set of viral latency genes, and appear phenotypically as resting memory B cells8 40—the same population of infected cells found in healthy carriers. However, the frequency of infected cells is increased in patients with PTLD. Thus, there is no expansion of LCL-like immunoblasts in the peripheral blood of PTLD patients, as had been thought previously. Instead, virus-infected cells in the blood of patients with PTLD are similar to those found in healthy seropositive individuals.

Analysis of the frequency of infected cells and the copy number of EBV genomes per infected cell demonstrates that an increase in the frequency of infected cells accounts for most, if not all, of the increased EBV load in the PBMCs of PTLD patients. Proliferation of infected cells in the blood seems unlikely to account for the increased number of EBV-infected cells insofar as our evidence suggests that these cells are not expressing the viral proteins that drive proliferation. This conclusion is consistent with that of Babcock et al40 showing that EBV-infected cells in PTLD patients, as in healthy controls, are resting memory B cells. The increased numbers of EBV-infected B cells in PTLD patients may therefore reflect increased numbers of infectious events. If so, the site of infection is not likely to be the peripheral blood because neither lytic transcripts nor increased viral genome copy numbers per cell were detected. The locus of virion production and B-cell infection remains a subject of speculation in healthy individuals and PTLD patients. Babcock et al40 proposed that there is increased virion production in the lymphoid tissue of PTLD patients.

Our analysis of patients with active PTLD and PTLD in remission (after chemotherapy or withdrawal of immunosuppression) confirms a relationship between disease activity and viral load. However, this relationship disappears in patients treated with rituximab. EBV-infected lymphocytes in peripheral blood differ in their sensitivity to rituximab from tumor cells of PTLD insofar as the EBV-infected cells in the blood promptly and dramatically decline with therapy, while the response of tumor cells is variable. EBV-infected lymphocytes also differ from tumor cells in that virus-infected lymphocytes are resting cells that express a restricted set of viral antigens, while tumor cells actively proliferate and commonly express the full set of EBV-latency antigens.13 These differences suggest that virally infected cells in peripheral blood belong to a separate compartment from tumor cells. Thus, monitoring viral load in peripheral blood does not predict clinical response of patients with PTLD tumors.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr Kathryn Kloppenstein for her assistance.

Supported by grant P01CA15396 from the National Cancer Institute.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

R. F. Ambinder, Cancer Research Bldg, Rm 389, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21231; e-mail:rambind@jhmi.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal