Abstract

Cyclin A1 is a newly discovered cyclin that is overexpressed in certain myeloid leukemias. Previously, the authors found that the frequency of cyclin A1 overexpression is especially high in acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL). In this study, the authors investigated the mechanism of cyclin A1 overexpression in APL cells and showed that the APL-associated aberrant fusion proteins (PML–retinoic acid receptor alpha [PML-RARα] or PLZF-RARα) caused the increased levels of cyclin A1 in these cells. The ectopic expression of either PML-RARα or PLZF-RARα in U937 cells, a non-APL myeloid cell line, led to a dramatic increase of cyclin A1 messenger RNA and protein. This elevation of cyclin A1 was reversed by treatment with all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) in cells expressing PML-RARα but not PLZF-RARα. ATRA also greatly reduced the high levels of cyclin A1 in the APL cell lines NB4 and UF-1. No effect of ATRA on cyclin A1 levels was found in the ATRA-resistant NB4-R2 cells. Further studies using ligands selective for various retinoic acid receptors suggested that cyclin A1 expression is negatively regulated by activated RARα. Reporter assays showed that PML-RARα led to activation of the cyclin A1 promoter. Addition of ATRA inhibited PML-RARα–induced cyclin A1 promoter activity. Taken together, our data suggest that PML-RARα and PLZF-RARα cause the high-level expression of cyclin A1 seen in acute promyelocytic leukemia.

Introduction

Mammalian cyclin A1 is a highly tissue-specific cyclin with prominent expression only in testis in normal tissues.1-3 The mammalian cyclin A1 has a homologue in Xenopus, and, interestingly, the Xenopus cyclin A1 is expressed in eggs and early embryos, but not in late embryos or cultured cells.4 Although the role of Xenopus cyclin A1 in early development is still unknown, the cyclin A1-cdk2 activity has been shown to function in the p53-independent apoptosis pathway induced by ionizing radiation before the midblastula transition.5

Recently, a cyclin A1 deletional murine model has been established.6 In cyclin A1−/− mice, male germ cells of the testis cannot enter the first meiotic division; thus, the males are defective in spermatogenesis, which results in male sterility. However, the meiotic cell cycle for oogenesis seems normal in these mice. This transgenic model demonstrated that cyclin A1 has an important role in the regulation of the meiotic cell cycle during spermatogenesis. No other abnormalities have been reported for the cyclin A1−/− mice as of yet. In contrast, the deletion of murine cyclin A2 (homologue of human cyclin A) is embryonically lethal.7 Together, these results suggest that cyclin A1 and cyclin A2 have different biological functions.

Although human cyclin A1 has high expression only in the testis, we and others also found cyclin A1 expression in CD34+hematopoietic progenitor cells, which suggests that cyclin A1 may have a function in hematopoiesis.8,9 So far, no conclusive evidence shows that cyclin A1 functions in the mitotic cell cycle. But the expression of a Xenopus cyclin A1 mutant in yeast had a severe effect on the cell cycle of the yeast by inducing aberrant spindle movement.10 Also, we recently showed that the human cyclin A1 messenger RNA (mRNA), protein- and cdk2-associated kinase activity are highly regulated during the mitotic cell cycle in the MG63 osteosarcoma cell line.11 Furthermore, we observed that cyclin A1 interacts with important cell-cycle regulators (Rb and E2F-1) in the leukemic cell line NB4.11 In addition, cyclin A1 can activate the transcription factor B-Myb by phosphorylating its c-terminus (C.M. et al, unpublished data, January 2000).

Previously, we studied a large collection of leukemia samples from patients and found high levels of cyclin A1 expression in all of the acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) samples.8 APL is a subtype (French-American-British classification subtype M3) of acute myeloid leukemia and is characterized by a t(15;17) chromosomal translocation in 99% of the cases.12 This translocation causes the fusion of 2 genes, PML andRARα, leading to the aberrant fusion protein PML–retinoic acid receptor alpha (PML-RARα), which disrupts the function of both normal PML and RARα.12 The PML-RARα fusion protein has an important role in the development of APL, as shown by transgenic murine models.13-15 On the basis of this knowledge, we decided to test the hypothesis that the PML-RARα fusion protein is responsible for the overexpression of cyclin A1 in APL. We show that the ectopic expression of PML-RARα is sufficient to elevate levels of cyclin A1 in U937 myeloid leukemia cells and cyclin A1 is negatively regulated by the RARα pathway. Induction of cyclin A1 occurs at the transcriptional level, since PML-RARα co-expression led to induction of cyclin A1 promoter activity. These results appear to explain why cyclin A1 is overexpressed in APL cells and raise the possibility that overexpression of cyclin A1 may contribute to the aberrant proliferation of these leukemia cells.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

Human leukemic cells were cultured in RPMI with L-glutamine and 10% fetal calf serum. NB4 and NB4-R2 cells were gifts from Dr Lanotte (St Louis-Hospital, Paris, France), and the UF-1 cells were a gift from Dr Kizaki (Keio University, Tokyo, Japan). The stable U937 cell line (PR9) that can express PML-RARα in a Zn2+-inducible fashion was previously described,16 and it was kindly provided by Dr Pelicci (Perugia University, Perugia, Italy). The stable PLZF-RARα–expressing U937 cell line (B412) was a gift from Dr Ruthardt (University of Frankfurt, Frankfurt, Germany).17For induction of either PML-RARα or PLZF-RARα in these cells, 0.1 mmol/L ZnSO4 was added to the culture media. All cell lines were cultured in regular RPMI plus 10% fetal calf serum.

Northern blot analysis

Total RNA was extracted from cells by means of Trizol reagent (GIBCO-BRL, Gaithersburg, MD), and a standard Northern blot protocol was used.18 The complementary DNA (cDNA) fragments of cyclin A1, cyclin A, and β-actin were used as probes. For analyzing the half-life of cyclin A1 mRNA, cells were treated with 10 μg/mL actinomycin D, and cyclin A1 mRNA levels were followed over time by Northern blot analysis.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Quantitation of mRNA levels for cyclin A1 was also carried out by means of the 5′ nuclease assay real-time fluorescence detection method as described previously.19 Briefly, cDNA was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in the ABI prism 7700 sequence detector (PE Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Oligonucleotide probes annealed to the PCR products during the annealing and extension steps. The probes were labeled at the 5′ end with VIC (GAPDH) or FAM (cyclin A1) and at the 3′ end with TAMRA, which served as a quencher. The 5′ to 3′ nuclease activity of the Taq polymerase cleaved the probe and released the fluorescent dyes (VIC or FAM), which were detected by the laser detector of the sequence detector. After the detection threshold was reached, the fluorescence signal was proportional to the amount of PCR product generated. Initial template concentration was calculated from the cycle number when the amount of PCR product passed a threshold set in the exponential phase of the PCR reaction. Primers and probes were described previously.19 All probes were positioned across exon-exon junctions. Gene expression levels were calculated by means of standard curves generated by serial dilutions of U937 cDNA. The relative amounts of gene expression were calculated by using the expression of GAPDH as an internal standard. At least 3 independent analyses were performed for each gene, and data are presented as mean ± SE.

Immunoblot analysis

Immunoblots were performed as described18 with the use of an antibody against a C-terminal peptide of cyclin A1.11 Leukemia cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline and lysed in RIPA buffer, and the protein concentration was determined by protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). For each sample, 20 μg total protein was loaded per lane, and 4% to 15% gradient gels were used for protein separation. Proteins of the gel were transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane. An anti-actin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) was used to confirm equal loading.

Treatment of cells with retinoids

The following retinoids were used in this study: ATRA (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO); 9-cis retinoic acid (Sigma Chemical); and retinoid receptor–specific ligands AM580 (RARα), SR11346 (RARβ), SR11254 (RARγ), SR11246 (retinoid X receptor [RXR]), SR11283 (anti–AP-1), and SR11256 (panagonist) (gifts of Dr Dawson, SRI International, Menlo Park, CA). The concentration and time for treatment were noted in Figure legends.

Luciferase reporter assays

Transient transfections and reporter assays in U937 cells were carried out by electroporation as described previously.20A total of 21 μg of plasmid was electroporated; this consisted of 10 μg reporter plasmid and 10 μg expression plasmid together with 1 μg of the renilla-luciferase–expressing pRL-SV40 plasmid (Promega, Madison, WI). The previously described cyclin A1 reporter plasmids contained base pairs −1199 to +145 (1344 bp) and base pairs −190 to −145 (335 bp), respectively.20 25 In experiments without PML-RARα expression, empty expression vector was used to reach the total of 21 μg. Luciferase activity for firefly and renilla luciferase was analyzed 14 hours after transfection; experiments were independently carried out at least 3 times; and the bars represent mean ± SE.

Results

The ectopic expression of APL-associated fusion proteins PML-RARα and PLZF-RARα induces elevation of cyclin A1 levels in U937 cells

To investigate whether the expression of the fusion protein PML-RARα was sufficient to induce a high level of cyclin A1 expression, we used an engineered U937 leukemia cell line (PR9) that has a stable integration of the PML-RARα cDNA under the control of the Zn2+-inducible murine metallothionein 1 promoter.16 This cell line allowed us to analyze the influence of PML-RARα on cyclin A1 levels by comparing the cyclin A1 RNA levels before and after adding Zn2+ to the medium.

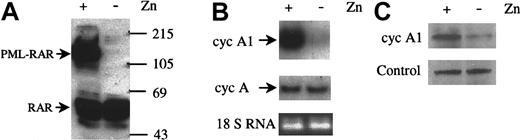

The anti-RARα immunoblot in Figure 1A shows the induction of PML-RARα protein when 100 μmol/L ZnSO4 was added to PR9 cells for 24 hours. During this period, the level of cyclin A1 mRNA was dramatically increased, as shown by Northern blot (Figure 1B, upper panel), while the cyclin A mRNA level did not change significantly (Figure 1B, middle panel). Densitometric measurement indicated a 10.9-fold increase of cyclin A1 in Zn2+-induced cells. An anti-cyclin A1 immunoblot also showed that the protein levels of cyclin A1 increased when PML-RARα was expressed (Figure 1C). Adding Zn2+ to the control parental U937 cells or to empty vector transfected U937 cells did not change cyclin A1 mRNA under the same experimental conditions (data not shown). In addition, Zn2+ treatment of U937 cells transfected with a Zn2+-inducible C/EBPα cDNA led to cyclin A1 down-regulation, thus further evidencing the specificity of cyclin A1 induction by PML-RARα (data not shown).

Induction of cyclin A1 by PML-RARα expression.

(A) Immunoblot showing induction of PML-RARα by ZnSO4(0.1 mmol/L, 24 hours) in U937-PR9 cells that were stably transfected with PML-RARα under control of a Zn2+-inducible promoter. On each lane, 30 μg protein was loaded, and the blot was probed with an anti-RARα rabbit polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Protein markers are shown in kilodaltons. (B) Northern blot showing elevation of cyclin A1 RNA (upper panel) but not cyclin A (middle panel) when PML-RARα was induced by ZnSO4. Equal loading was shown by staining for the 18-strand RNA (18s RNA). PR9 cells were induced to express PML-RARα for 24 hours, and total RNA was isolated. On each lane, 20 μg RNA was loaded. (C) Immunoblot showing that cyclin A1 protein levels also increased after induction of PML-RARα in U937-PR9 cells (24 hours, ZnSO4). On each lane, 30 μg protein was loaded. The lower panel shows a nonspecific band recognized by the anti–cyclin-A1 antibody that served as an internal control for loading of protein.

Induction of cyclin A1 by PML-RARα expression.

(A) Immunoblot showing induction of PML-RARα by ZnSO4(0.1 mmol/L, 24 hours) in U937-PR9 cells that were stably transfected with PML-RARα under control of a Zn2+-inducible promoter. On each lane, 30 μg protein was loaded, and the blot was probed with an anti-RARα rabbit polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Protein markers are shown in kilodaltons. (B) Northern blot showing elevation of cyclin A1 RNA (upper panel) but not cyclin A (middle panel) when PML-RARα was induced by ZnSO4. Equal loading was shown by staining for the 18-strand RNA (18s RNA). PR9 cells were induced to express PML-RARα for 24 hours, and total RNA was isolated. On each lane, 20 μg RNA was loaded. (C) Immunoblot showing that cyclin A1 protein levels also increased after induction of PML-RARα in U937-PR9 cells (24 hours, ZnSO4). On each lane, 30 μg protein was loaded. The lower panel shows a nonspecific band recognized by the anti–cyclin-A1 antibody that served as an internal control for loading of protein.

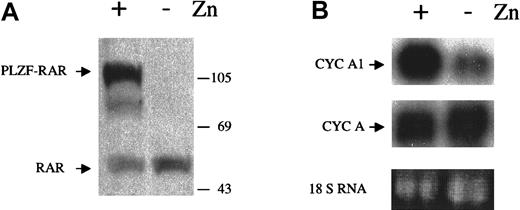

Since PML-RARα disrupts the functions of both normal PML and RARα, we hypothesized that either the PML or the RARα pathway was involved in the regulation of cyclin A1. To determine which of the 2 pathways was involved, we studied whether another fusion protein, PLZF-RARα, could affect cyclin A1 level. PLZF-RARα is a fusion protein generated by a t(11;17) chromosomal translocation that fuses the zinc-finger protein PLZF to RARα. This translocation is observed in a small portion of APL cases.12 The PLZF-RARα fusion protein can also function as a dominant negative protein to disrupt the RARα function. Since this rare translocation does not involve PML, it should not affect the normal functions of PML. To test the effects of PLZF-RARα on cyclin A1 levels, we used another engineered U937 cell line with stable integration of the PLZF-RARα cDNA under the control of the Zn2+-inducible metallothionein 1 promoter.17 This cell line, B412, expressed the fusion protein PLZF-RARα when ZnSO4 was added, as shown by an anti-RARα immunoblot (Figure 2A). The Northern blot in Figure 2B showed that the expression of PLZF-RARα could also elevate cyclin A1 mRNA dramatically (8.1-fold increase by densitometric measurement), and the cyclin A mRNA level did not change significantly. Again, the addition of ZnSO4 to the parental U937 cells did not change cyclin A1 levels (data not shown). These results suggested that the RARα pathway was involved in the regulation of cyclin A1, which is disrupted in APL cells.

Induction of cyclin A1 by expression of PLZF-RARα.

(A) PLZF-RARα was induced by ZnSO4 (0.1 mmol/L, 24 hours) in U937-B412 cells. The immunoblot was performed as described in the legend for Figure 1. (B) Cyclin A1 RNA levels before and after induction of PLZF-RARα in B412 cells (Northern blot, upper panel). The same blot was also probed with a cyclin A probe after stripping of the cyclin A1 probe (middle panel), and no difference was observed for cyclin A. Equal loading was shown by staining for the 18s RNA. B412 cells were induced to express PLZF-RARα for 24 hours, and total RNA was isolated. On each lane, 20 μg RNA was loaded.

Induction of cyclin A1 by expression of PLZF-RARα.

(A) PLZF-RARα was induced by ZnSO4 (0.1 mmol/L, 24 hours) in U937-B412 cells. The immunoblot was performed as described in the legend for Figure 1. (B) Cyclin A1 RNA levels before and after induction of PLZF-RARα in B412 cells (Northern blot, upper panel). The same blot was also probed with a cyclin A probe after stripping of the cyclin A1 probe (middle panel), and no difference was observed for cyclin A. Equal loading was shown by staining for the 18s RNA. B412 cells were induced to express PLZF-RARα for 24 hours, and total RNA was isolated. On each lane, 20 μg RNA was loaded.

ATRA reversed elevated levels of cyclin A1 mRNA induced by PML-RARα but not by PLZF-RARα

Since the oncogenic effect of PML-RARα can be reversed by ATRA, which activates RARα and restores the normal functions of the RARα pathway, we tested whether ATRA could also reverse the elevated levels of cyclin A1 induced by PML-RARα in PR9 cells. As shown in Figure3, ATRA treatment of PR9 (induced by Zn2+ for 24 hours to express PML-RARα) reversed the elevation of cyclin A1 mRNA in a time- and dose-dependent manner. When 10−6 mol/L ATRA was used, an 80% reduction of cyclin A1 mRNA was observed by 6 hours, and these transcripts continued to decrease to almost undetectable levels at 48 hours. Since ATRA reduced the cyclin A1 mRNA level below base level before induction of PML-RARα, we tested and confirmed that ATRA could also reduce the expression of cyclin A1 in the parental U937 cells (data not shown). The dose-response experiments showed that as little as 10−12 mol/L ATRA (24 hours) could significantly decrease the level of cyclin A1 mRNA in PR9 cells (Figure 3B-C). In contrast to the strong effects of ATRA on PML-RARα–expressing U937 cells, a much weaker reaction to ATRA was observed in PLZF-RARα–expressing U937 cells (Figure 3C). At all concentrations tested, a stronger reactivity to ATRA was noted in PML-RARα– than in PLZF-RARα–expressing U937 cells (Figure 3C).

Effects of ATRA on PML-RARα– and PLZF-RARα–induced elevation of cyclin A1 in inducibly transfected U937 cells.

(A) PR9 cells were induced to express PML-RARα for 24 hours, and expression of cyclin A1 mRNA was analyzed by Northern blot at various time points after addition of ATRA (1 μmol/L). On each lane, 20 μg total RNA was loaded. (B) Dose-effect of ATRA (24 hours) was analyzed as in panel A. (C) Real-time PCR was used to compare the dose-dependent effects of ATRA on PML-RARα– and on PLZF-RARα–expressing U937 cells (see “Materials and methods” for details on the procedure). Shown are means and SEM of 3 independent analyses. At all concentrations of ATRA, the effects on cyclin A1 expression were more pronounced in PML-RARα– than in PLZF-RARα–expressing cells.

Effects of ATRA on PML-RARα– and PLZF-RARα–induced elevation of cyclin A1 in inducibly transfected U937 cells.

(A) PR9 cells were induced to express PML-RARα for 24 hours, and expression of cyclin A1 mRNA was analyzed by Northern blot at various time points after addition of ATRA (1 μmol/L). On each lane, 20 μg total RNA was loaded. (B) Dose-effect of ATRA (24 hours) was analyzed as in panel A. (C) Real-time PCR was used to compare the dose-dependent effects of ATRA on PML-RARα– and on PLZF-RARα–expressing U937 cells (see “Materials and methods” for details on the procedure). Shown are means and SEM of 3 independent analyses. At all concentrations of ATRA, the effects on cyclin A1 expression were more pronounced in PML-RARα– than in PLZF-RARα–expressing cells.

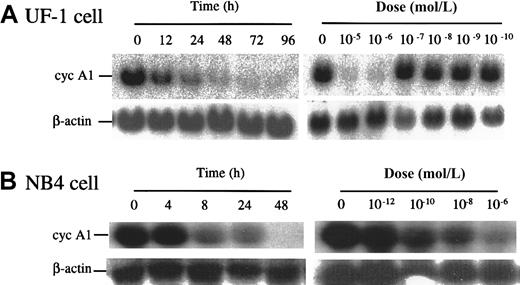

Cyclin A1 levels were reduced by ATRA in patient-derived promyelocytic leukemia cell lines

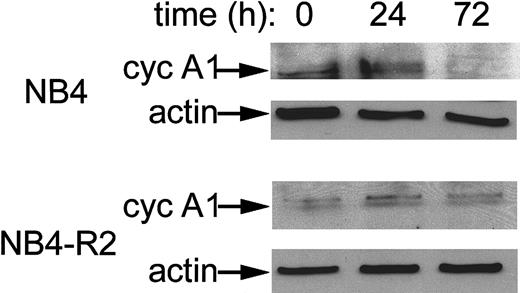

We tested 2 APL cell lines, UF-1 and NB4, that naturally express PML-RARα and high levels of cyclin A1. As shown in Figure4A, exposure of UF-1 to ATRA dramatically reduced expression of cyclin A1 mRNA in a dose- and time-dependent manner. A 70% decrease of cyclin A1 mRNA level occurred at 12 hours' exposure to ATRA (10−6 mol/L), and concentrations higher than 10−7 mol/L were effective. Similar results were also observed for NB4 cells with a 90% reduction at 8 hours (10−6 mol/L), and the cyclin A1 mRNA level became nearly undetectable at 48 hours (Figure 4B). For NB4 cells, ATRA concentrations as low as 10−10 mol/L markedly reduced cyclin A1 mRNA levels at 24 hours (Figure 4B). The UF-1 cells were established from an individual with APL whose leukemic cells had become refractory to ATRA. Previous studies have shown that UF-1 APL cells were more resistant to ATRA than NB4 cells.21,22 This was also observed here. An anti–cyclin-A1 immunoblot showed that the level of cyclin A1 protein was also reduced by ATRA treatment in NB4 cells. After 72 hours of incubation, negligible levels of cyclin A1 protein were present (Figure 5). We also analyzed the effects of ATRA on NB4-R2 cells, an NB4-derived cell line that is resistant to ATRA.23 24 This cell line did not down-regulate cyclin A1 upon ATRA exposure as demonstrated by Western blot analyses (Figure 5). Similar results were obtained at the mRNA level (data not shown).

ATRA reduced levels of cyclin A1 RNA in the APL cell lines UF-1 and NB4.

(A) Northern blots showing the time course and dose response of cyclin A1 mRNA levels in UF-1 cells exposed to ATRA. In the time-course study, 10−6 mol/L ATRA was used. In the dose-response study, cells were harvested 24 hours after treatment. On each lane, 20 μg total RNA was loaded, and equal loading was confirmed by probing the blot with an actin probe. (B) NB4 cells were studied in a manner similar to that described in panel A.

ATRA reduced levels of cyclin A1 RNA in the APL cell lines UF-1 and NB4.

(A) Northern blots showing the time course and dose response of cyclin A1 mRNA levels in UF-1 cells exposed to ATRA. In the time-course study, 10−6 mol/L ATRA was used. In the dose-response study, cells were harvested 24 hours after treatment. On each lane, 20 μg total RNA was loaded, and equal loading was confirmed by probing the blot with an actin probe. (B) NB4 cells were studied in a manner similar to that described in panel A.

Reduction of cyclin A1 protein levels by ATRA in NB4 cells but not in ATRA-resistant NB4-R2 cells.

Immunoblot analysis showing cyclin A1 protein levels in NB4 cells at 0, 24, and 72 hours of exposure to ATRA (10−6 mol/L). On each lane, 20 μg total protein was loaded. An anti-actin antibody was used to demonstrate equal loading.

Reduction of cyclin A1 protein levels by ATRA in NB4 cells but not in ATRA-resistant NB4-R2 cells.

Immunoblot analysis showing cyclin A1 protein levels in NB4 cells at 0, 24, and 72 hours of exposure to ATRA (10−6 mol/L). On each lane, 20 μg total protein was loaded. An anti-actin antibody was used to demonstrate equal loading.

RARα is involved in the regulation of cyclin A1

To determine the role of different isoforms of retinoid receptors in the regulation of cyclin A1, we tested a panel of retinoids that could preferentially activate different receptor isoforms. NB4 cells were treated for 3 days with various retinoids (5 × 10−7 mol/L), and the levels of cyclin A1 mRNA were analyzed by Northern blot. As shown in Figure6, compounds that activated RARα and, to a lesser extent, RARβ reduced cyclin A1 levels in NB4 cells. Ligands for RARγ, RXR, and an anti–AP-1 retinoid had no effect on cyclin A1 mRNA levels. In contrast, expression of cyclin A mRNA decreased only slightly after exposure to the retinoids, and little difference in potency was observed among various analogues.

Modulation of levels of cyclin A1 RNA by retinoids selective for different retinoid acid receptor isoforms.

NB4 cells were treated with the indicated ligands (5 × 10−7 mol/L) for 3 days, and Northern blot was performed with the simultaneous use of the 32P-labeled cyclin A1 and cyclin A probes. On each lane, 20 μg total RNA was loaded.

Modulation of levels of cyclin A1 RNA by retinoids selective for different retinoid acid receptor isoforms.

NB4 cells were treated with the indicated ligands (5 × 10−7 mol/L) for 3 days, and Northern blot was performed with the simultaneous use of the 32P-labeled cyclin A1 and cyclin A probes. On each lane, 20 μg total RNA was loaded.

PML-RARα does not alter the mRNA half-life of cyclin A1

To investigate whether cyclin A1 mRNA was stabilized by the expression of PML-RARα, we determined the half-life of cyclin A1 mRNA by treating PR9 cells (under both inducing and noninducing conditions for PML-RARα) with actinomycin D followed by Northern blot analysis. As shown in Figure 7, the half-life of cyclin A1 did not change markedly under noninducing and inducing conditions, with calculated half-lives of cyclin A1 being 3.6 and 4.5 hours for noninduced and induced cells, respectively. These results suggested that the increased level of cyclin A1 mRNA caused by PML-RARα was probably a result of increased transcription of cyclin A1.

Half-life of cyclin A1 mRNA in PR9 cells with and without induction of PML-RARα.

The Northern blot was performed as described in “Materials and methods.” For uninduced and induced cells, 20 and 10 μg RNA was loaded, respectively. The calculated half-lives were 3.6 and 4.5 hours for uninduced (−Zn2+) and induced (+Zn2+) cells, respectively.

Half-life of cyclin A1 mRNA in PR9 cells with and without induction of PML-RARα.

The Northern blot was performed as described in “Materials and methods.” For uninduced and induced cells, 20 and 10 μg RNA was loaded, respectively. The calculated half-lives were 3.6 and 4.5 hours for uninduced (−Zn2+) and induced (+Zn2+) cells, respectively.

PML-RARα expression leads to increased cyclin A1 promoter activity. Potential effects of PML-RARα on the human cyclin A1 promoter were analyzed in transient transfection assays with the use of firefly luciferase as the reporter and renilla luciferase driven from an SV40 promoter for standardization purposes. These experiments were carried out in the native U937 cell line. Expression of PML-RARα reduced luciferase activity of the empty vector (PGL3-Basic) by 80% (Figure8A). In contrast, PML-RARα led to an increase of cyclin A1 promoter activity by more than 2-fold. The effect was stronger in the 1344-bp promoter fragment than in the 335-bp promoter fragment (Figure 8A). This experiment was performed 6 times and always led to the same, albeit relatively small, stimulation. To determine whether the increase of cyclin A1 promoter activity upon PML-RARα expression was specific, the experiments were repeated in the presence of ATRA (10−6 mol/L). PGL3-Basic activity was similar in these experiments and in the experiments performed in the absence of ATRA (Figure 8B). In stark contrast, ATRA not only inhibited the PML-RARα–mediated increase of cyclin A1 promoter activity but actually led to a decrease of cyclin A1 promoter activity when PML-RARα was co-expressed (Figure 8B).

Activation of the cyclin A1 promoter by PML-RARα and reversal of this effect by ATRA.

U937 cells were transiently transfected with cyclin A1 promoter-luciferase constructs and either PML-RARα expression vector or an empty vector control. Expression of a renilla luciferase expression vector was used for standardization purposes. (A) Activity of the empty luciferase reporter vector PGL3-Basic was reduced by 80% upon PML-RARα expression. In contrast, the cyclin A1 promoter constructs were activated more than 2-fold (1344-bp construct) or 1.7-fold (335-bp construct). (B) The activating effects of PML-RARα were reversed when ATRA (10−6 mol/L) was added after electroporation.

Activation of the cyclin A1 promoter by PML-RARα and reversal of this effect by ATRA.

U937 cells were transiently transfected with cyclin A1 promoter-luciferase constructs and either PML-RARα expression vector or an empty vector control. Expression of a renilla luciferase expression vector was used for standardization purposes. (A) Activity of the empty luciferase reporter vector PGL3-Basic was reduced by 80% upon PML-RARα expression. In contrast, the cyclin A1 promoter constructs were activated more than 2-fold (1344-bp construct) or 1.7-fold (335-bp construct). (B) The activating effects of PML-RARα were reversed when ATRA (10−6 mol/L) was added after electroporation.

Discussion

Recently, we observed that cyclin A1 is often overexpressed in APL, a subtype of acute myeloid leukemia.8 To elucidate the mechanism of cyclin A1 overexpression in APL, we tested whether the APL-associated aberrant fusion protein PML-RARα was responsible for the elevation of cyclin A1 mRNA. Using a stable PML-RARα–expressing cell line, we found that expression of PML-RARα was sufficient to induce the elevation of levels of cyclin A1. Employing similar approaches, we showed that induction of expression of another APL-associated fusion protein, PLZF-RARα, also increased the levels of cyclin A1. Control experiments involving non-transfected and empty-vector–transfected U937 cell lines as well as a Zn2+-inducible C/EBPα U937 cell line demonstrated the specificity of cyclin A1 induction by the APL fusion proteins.

Since both fusion proteins disrupt the normal RARα function, our results strongly suggested that the RARα pathway negatively regulates the expression of cyclin A1 and that this negative regulation is disrupted by the aberrant fusion proteins. This hypothesis was further supported by the observation that ATRA, which can restore the normal functions of RARα, reversed the PML-RARα–induced increase of cyclin A1 in PR9 cells. The effect of ATRA on the PLZF-RARα–expressing B412 cell lines was significantly weaker. But in contrast to the clinically observed ATRA resistance of PLZF-RARα–expressing APL, a decrease in cyclin A1 expression was noted. One possible explanation would be that inducible expression systems (even in initially clonal populations) contain cells with highly differing degrees of transgene expression. Therefore, it is possible that non–PLZF-RARα–expressing or only low-level PLZF-RARα–expressing cells are responsible for the decrease of cyclin A1 expression. This explanation is even more likely considering that non-transfected U937 cells showed decreased cyclin A1 expression upon ATRA exposure as well (data not shown).

In addition to the effects of ATRA on the genetically engineered cell lines, ATRA lowered cyclin A1 levels in the APL cell lines UF-1 and NB4. Again, ATRA-resistant NB4-R2 cells did not respond to ATRA. By analyzing the activity of retinoids that were selective for various retinoid acid receptor isoforms, we showed that activated RARα mediated the negative regulation of cyclin A1. This is congruent with the fact that APL is caused by the abnormal fusion product of PML and RARα, and clinical remissions of APL occur by administering ATRA to these individuals.

Further experiments concerning the molecular mechanism of cyclin A1 induction by PML-RARα hinted at the transcriptional level as the origin of cyclin A1 overexpression in APL. First, cyclin A1 was consistently induced by PML-RARα at the mRNA as well as at the protein level. Second, PML-RARα did not change the cyclin A1 mRNA half-life. Third, promoter assays demonstrated that PML-RARα expression led to an increase of cyclin A1 promoter activity. The degree of cyclin A1 promoter induction upon PML-RARα expression was relatively small but highly consistent. The decrease of promoter activity after addition of ATRA further indicated the specificity of the PML-RARα effect on the cyclin A1 promoter.

How does PML-RARα act upon the cyclin A1 promoter and how is this effect reversed by ATRA? Previously, ligand-activated RARα has been reported to mediate transcriptional repression through AP-1 sites in promoter regions of genes.26,27 In our experiments, an anti–AP-1 ligand did not have any effect on cyclin A1 levels in NB4 cells, indicating that activated RARα probably does not affect the cyclin A1 promoter through AP-1 sites. In addition, the known human cyclin A1 promoter sequence does not contain consensus retinoic acid response elements (RAREs).25 Our previous work showed that expression of cyclin A1 is tightly regulated by histone deacetylase activity, and several lines of evidence suggested the existence of a tissue-specific repressor of cyclin A1 promoter activity.19 The findings presented in the current study are consistent with a model in which the repressor mechanism of the cyclin A1 promoter itself is repressed by PML-RARα and PLZF-RARα. This hypothesis would explain why the repressor proteins PLZF-RARα and PML-RARα can lead to cyclin A1 induction and activation of the cyclin A1 promoter in the absence of known RAREs in the promoter sequence. Activation of RARα can decrease cyclin A1 levels, but the exact mechanism of repression is unclear. The relevant repressor mechanism might be specific for hematopoietic cells since PML-RARα activated the cyclin A1 promoter in U937 cells but not in NIH3T3 cells or in Cos-7 cells (data not shown). Future work will focus on the further characterization of this repressor mechanism.

Whether cyclin A1 overexpression plays a role in the pathogenesis of APL also needs further investigation. The ectopic expression of PML-RARα in U937 cells was previously shown to lead to a loss of the capacity to differentiate in response to either vitamin D3or transforming growth factor β1.16 PLZF-RARα expression had similar effects on U937 cells except that it did not cause enhanced sensitivity to retinoid acid.17 Cyclin A1 is likely to function in the progression of the mitotic cell cycle when it is expressed.11 In addition to the binding of cyclin A1 to Rb-family members, we recently discovered that it can also phosphorylate and activate B-Myb, an essential transcription factor for G1/S progression (C.M. et al, unpublished data). B-Myb is of crucial importance for the proliferation of hematopoietic cells, and its activation by cyclins is required to gain strong transcriptional activity.28 29 These findings imply a role for cyclin A1 in acute promyelocytic leukemia, but further studies are necessary to elucidate the potential role of cyclin A1 in the pathogenesis of acute myeloid leukemia.

In summary, 2 discoveries were made in this study: (1) Overexpression of cyclin A1 observed in APL cells is caused by the expression of the aberrant fusion proteins, PML-RARα and PLZF-RARα. PML-RARα itself can lead to activation of the cyclin A1 promoter. (2) Cyclin A1 is negatively regulated by the RARα pathway, which is disrupted by the abnormal fusion proteins. The exact relevance of cyclin A1 in the pathogenesis of acute promyelocytic leukemia awaits further studies.

Acknowledgments

H.P.K. holds the Mark Goodson Chair in Oncology Research and is a member of the Jonsson Cancer Center. Annette Westermann and Silvia Klümpen for excellent technical assistance; Drs Kizaki, Lanotte, Pelicci, and Ruthardt for providing cell lines used in this study; and Dr Behre for providing RNA from the C/EBPα inducibly transfected cell line.

Supported by grant no. 5R01CA26038-22 from National Institutes of Health and US Department of the Army grant DAMD17-96-1-6054, as well as the Parker Hughes, C. and H. Koeffler Funds, Horn Foundation, and Lymphoma Foundation of America. C.M's work is supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Mu 1328/2-1), the Deutsche Krebshilfe (10-1539-Mü1), and the IMF-program at the University of Münster.

C.M. and R.Y. contributed equally to this article.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

H. Phillip Koeffler, Division of Hematology/Oncology, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center/UCLA School of Medicine, 8700 Beverly Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90048.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal