Abstract

In present studies, treatment with tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–related apoptosis inducing ligand (TRAIL, also known as Apo-2 ligand [Apo-2L]) is shown to induce apoptosis of the human acute leukemia HL-60, U937, and Jurkat cells in a dose-dependent manner, with the maximum effect seen following treatment of Jurkat cells with 0.25 μg/mL of Apo-2L (95.0% ± 3.5% of apoptotic cells). Susceptibility of these acute leukemia cell types, which are known to lack p53wt function, did not appear to correlate with the levels of the apoptosis-signaling death receptors (DRs) of Apo-2L, ie, DR4 and DR5; decoy receptors (DcR1 and 2); FLAME-1 (cFLIP); or proteins in the inhibitors of apoptosis proteins (IAP) family. Apo-2L–induced apoptosis was associated with the processing of caspase-8, Bid, and the cytosolic accumulation of cytochrome c as well as the processing of caspase-9 and caspase-3. Apo-2L–induced apoptosis was significantly inhibited in HL-60 cells that overexpressed Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL. Cotreatment with either a caspase-8 or a caspase-9 inhibitor suppressed Apo-2L–induced apoptosis. Treatment of human leukemic cells with etoposide, Ara-C, or doxorubicin increased DR5 but not DR4, Fas, DcR1, DcR2, Fas ligand, or Apo-2L levels. Importantly, sequential treatment of HL-60 cells with etoposide, Ara-C, or doxorubicin followed by Apo-2L induced significantly more apoptosis than treatment with Apo-2L, etoposide, doxorubicin, or Ara-C alone, or cotreatment with Apo-2L and the antileukemic drugs, or treatment with the reverse sequence of Apo-2L followed by one of the antileukemic drugs. These findings indicate that treatment with etoposide, Ara-C, or doxorubicin up-regulates DR5 levels in a p53-independent manner and sensitizes human acute leukemia cells to Apo-2L–induced apoptosis.

Introduction

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), also called Apo-2 ligand (Apo-2L), is a member of the TNF family, which has been shown to induce apoptosis of a variety of tumor cell lines more efficiently than normal cells.1-3 While in a recent report, TRAIL was demonstrated to induce apoptosis of human hepatocytes, it has also been shown to actively suppress human mammary adenocarcinoma growth in mice without any significant toxic effects, which are seen with the in vivo use of TNF and Fas ligand (CD95L).3,4 Apo-2L can bind to several members of the TNF receptor family, ie, death receptors (DRs) 4 and 5, decoy receptors (DcRs) 1 and 2, and osteoprotegerin.1 DR4 and DR5 contain a cytoplasmic region consisting of a stretch of 80 amino acids, designated the death domain (DD), responsible for transducing the death signal.1 Ligation by Apo-2L recruits the adaptor molecule FADD to the DD of DR4 and DR5.5 Through its death effector domain, FADD interacts with caspase-8 and caspase-10.5,6 Although FADD−/− cells have been shown to be sensitive to apoptosis induced by the ligation of DR4 and DR5 but not of Fas,7 both caspase-8 and FADD are essential to the function of TRAIL-mediated death-inducing signaling complex (DISC).5 Once recruited to FADD, caspase-8 drives its auto-activation through oligomerization and subsequently activates the downstream effector caspases, such as caspase-3, caspase-6, and caspase-7.6,8 Activated and processed caspase-8 can also cleave and activate the BH3 domain containing pro-apoptotic molecule Bid, which then translocates to the mitochondria triggering the pre-apoptotic mitochondrial events, including the cytosolic release of cytochrome (cyt) c.9-11 In the cytosol, cyt c and deoxyadenosine triphosphate (dATP) bind to Apaf-1 and cause its oligomerization.12,13 Apaf-1, in turn, binds and processes procaspase-9 into an active caspase that recruits, cleaves, and activates the effector caspase-3.12-14 Activated caspase-3 can proteolytically cleave a number of cellular proteins, eg, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), lamins, DFF 45 (ICAD, DNA fragmentation factor), fodrin, gelsolin, PKCδ, Rb, and DNA-PK, resulting in the morphologic features and DNA fragmentation of apoptosis.6,8,15 Thus, Apo-2L–induced caspase-3 activation may occur either directly through the activity of caspase-8 and/or through Apaf-1–mediated activity of caspase-9. This is supported by the observation that while Apaf−/− cells are sensitive to Fas L and TNFα, they are relatively resistant to Apo-2L–induced apoptotic signaling.16

There are several known determinants of Apo-2L–induced apoptotic signaling. Treatment with DNA-damaging anticancer agents can induce p53 and/or NFkB, which, in turn, can up-regulate DR5 and/or DR4 expression, thereby enhancing Apo-2L–induced apoptotic signaling.17,18 In contrast, DcR1, which is bound to the cell membrane through a glycolipid anchor and lacks DD, and the levels of DcR2, which has an incomplete and inactive DD, bind and titrate down Apo-2L and can act as inhibitors of Apo-2L–induced apoptosis.1 Additionally, an endogenous intracellular protein, FLAME-1 (also known as cFLIP, CASH, CLARP, MRIT, I-FLICE, and Usurpin), which has an N-terminus FADD homology and C-terminus caspase homology domains without caspase activity, has a dominant-negative effect against caspase-8 and caspase-10 and can potentially inhibit Apo-2L–induced death signaling.19 Finally, the levels of inhibitors of apoptosis proteins (IAP) family members, which include cIAP1, cIAP2, XIAP, and survivin, may also inhibit Apo-2L–induced apoptosis by specifically binding to and inhibiting the activities of caspase-3, caspase-9, and caspase-7.20-22 Although the ability of Apo-2L to induce apoptosis has been examined in a variety of human tumor cell types, the molecular steps of Apo-2L–induced apoptosis and its determinants have not been comprehensively evaluated in the human acute leukemia cells.

Etoposide, Ara-C, and doxorubicin are highly active antileukemic drugs.23 Intracellularly, following their interaction with DNA, these drugs ultimately cause DNA damage and cell-cycle arrest.24 By, as yet, undefined signal(s), this drug-induced DNA-damage and/or cell-cycle perturbation triggers the mitochondrial ΔΨm and release of cyt c, which ultimately results in the activities of caspase-9 and caspase-3. Recently, etoposide, CPT-11, doxorubicin, 5-FU, and, to a lesser extent, taxol were shown to augment Apo-2L–induced apoptosis of epithelial cancer cells.18 25-28 However, neither the molecular determinants of Apo-2L–induced apoptosis nor the interaction between chemotherapeutic agents and Apo-2L had been examined in human acute leukemia cells. In the present studies, our findings demonstrate that Apo-2L treatment triggers the processing of caspase-8 and Bid, and also causes cytosolic accumulation of cyt c, followed by Apaf-1–mediated caspase-9 and caspase-3 processing and apoptosis of human acute leukemia cells. Furthermore, our results show that treatment with etoposide, Ara-C, or doxorubicin increases DR5 levels and enhances Apo-2L–induced apoptosis of acute leukemia HL-60, U937, and Jurkat cells, which are known to lack p53wt function.

Materials and methods

Reagents

We purchased z-IETD-fmk and z-LEHD-fmk from Enzyme Systems Products (Livermore, CA). Anti–Apaf-1 and anti-Bid antiserums9,13 were kindly provided by Dr Xiaodong Wang of the University of Texas, Southwestern School of Medicine (Dallas). The recombinant human homotrimeric TRAIL (Apo-2L) (leucine zipper construct) was a gift from Immunex Corp (Seattle, WA).4Fas receptor (CD95) and ligand (FasL) monoclonal antibodies were purchased from Transduction Labs (Lexington, KY). Monoclonal anti-XIAP antibody was purchased from Boehringer Mannheim (Indianapolis, IN), while anti–cIAP-1 antibody was purchased from Pharmingen Inc (San Diego, CA). Polyclonal anti-DR4, anti-DcR1 and anti-DcR2, and anti–Apo-2L antibodies as well as Apo-2L R2 (DR5):Fc were purchased from Alexis Corp (San Diego, CA). Polyclonal anti-DR5 was obtained from Cayman Chemicals Co (Ann Arbor, MI).

Cell culture

Human acute leukemia HL-60, HL-60/Bcl-2, HL-60/Bcl-xL, U937, and Jurkat cells were maintained in a humidified 5.0 % CO2 environment in RPMI medium supplemented with 100 U penicillin per milliliter, 100 μg streptomycin per milliliter, 1% nonessential amino acids, 1% essential amino acids, and 10% bovine calf serum (Gibco Laboratories, Grand Island, NY), as previously described.29

Preparation of S-100 fraction and Western analysis of cytosolic cytochrome c

Untreated and drug-treated cells were harvested by centrifugation at 1000g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The cell pellets were washed once with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended with 5 vol buffer (20 mmol/L Hepes-KOH, pH 7.5, 10 mmol/L KCl, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 1 mmol/L sodium EDTA, 1 mmol/L sodium EGTA [ethylene glycol-bis {B-amino ethyl ether} N,N,N′,N-tetra acetic acid], 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol, and 0.1 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride), containing 250 mmol/L sucrose. The cells were homogenized with a 22-gauge needle, and the homogenates were centrifuged at 100 000g for 30 minutes at 4°C (S-100 fraction).12,30 The supernatants were collected, and the protein concentrations of S-100 were determined by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). We used 20 to 30 μg of the S-100 fraction for Western blot analysis of cyt c, as described previously.31 32

Western analyses of proteins

Western analyses of DR4, DR5, Apo-2L, caspase-8, caspase-9, caspase-3, Fas R, Fas L, Bid, PARP, XIAP, cIAP, survivin, and β-actin were performed with the use of specific antiserums or monoclonal antibodies according to previously reported protocols.31 32 Horizontal scanning densitometry was performed on Western blots by acquisition into Adobe PhotoShop (Apple, Cupertino, CA) and analysis by the NIH Image Program (US National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). The expression of β-actin was used as a control.

Apoptosis assessment by Annexin-V staining

After drug treatments, cells were resuspended in 100 μL staining solution (containing Annexin-V fluorescein and propidium iodide Annexin-V-FLUOS Staining Kit buffer, Boehringer Mannheim). Following incubation at room temperature for 15 minutes, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.29 Annexin V binds to cells that express phosphotidylserine on the outer layer of the cell membrane, and propidium iodide stains the cellular DNA of cells with a compromised cell membrane. This allows for the discrimination of live cells (unstained with either fluorochrome) from apoptotic cells (stained only with Annexin V) and necrotic cells (stained with both Annexin V and propidium iodide).33

Morphology of apoptotic cells

After drug treatment, 50 × 103 cells were washed with PBS (pH 7.3) and resuspended in the same buffer. Cytospin preparations of the cell suspensions were fixed and stained with Wright stain. Cell morphology was determined by light microscopy. In all, 5 different fields were randomly selected for counting of at least 500 cells. The percentage of apoptotic cells was calculated for each experiment, as described previously.34

Statistical analysis

Significant differences between values obtained in a population of leukemic cells treated with different experimental conditions were determined by paired t-test analyses. A one-way analysis of variance was also applied to the results of the various treatment groups, and post hoc analysis was performed by means of the Bonferroni correction method.

Results

Apo-2L induces apoptosis of human acute leukemia, HL-60, U937, and Jurkat cells

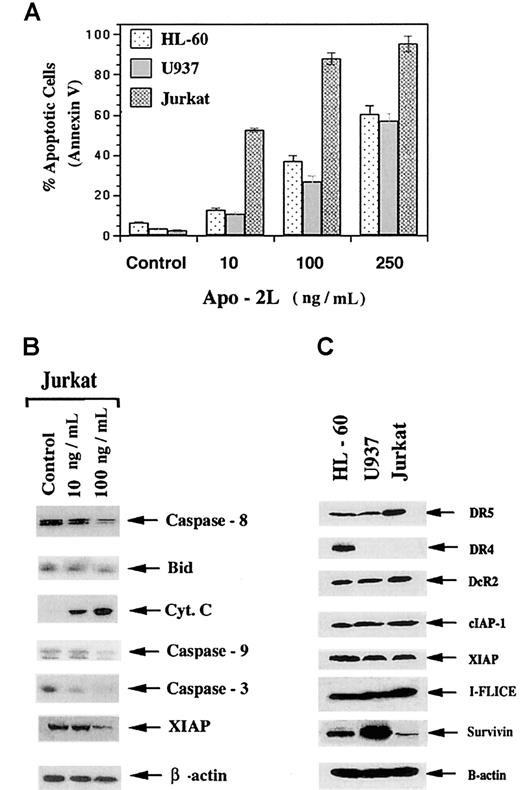

Although Apo-2L has been reported to induce apoptosis of a variety of tumor cell types,3,4 the sensitivity of human acute leukemia cells to Apo-2L–induced apoptosis and its molecular determinants had not been comprehensively determined. The results of present studies (Figure 1A) demonstrate that exposure to Apo-2L for 24 hours induced a dose-dependent increase in apoptosis of the cultured acute leukemia HL-60, U937, and Jurkat cells, as determined by Annexin V staining followed by flow cytometry. This was confirmed by light-microscopic morphologic examination of the Wright-stained, cytospun, Apo-2L–treated cells (data not shown). Jurkat cells demonstrated the highest sensitivity: exposure to 250 ng/mL of Apo-2L induced apoptosis of 95.0% ± 3.5% of the cells. Treatment with 100 ng/mL of Apo-2L also produced significantly more apoptosis of Jurkat, followed by HL-60 and U937 cells (P < .01). As shown in Figure 1B, treatment of Jurkat cells with Apo-2L was associated with the processing of caspase-8 and Bid, as well as the cytosolic accumulation of cyt c. Exposure to Apo-2L also resulted in the processing of caspase-9 and caspase-3 and down-regulation of XIAP. In these immunoblots, with the commercially available antibodies, we have not been able to uniformly detect the cleaved fragments of the processed pro-forms of caspase-8, caspase-9, and caspase-3. With processing, the levels of the pro-forms decline, as shown in the immunoblots. These effects were more pronounced after treatment of Jurkat cells with 100 ng/mL Apo-2L, as compared with 10 ng/mL (Figure 1B). Exposure to Apo-2L also induced similar molecular events in HL-60 and U937 cells (data not shown). Thus, in the acute leukemia cells, Apo-2L also triggered the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis. Some but not all previous reports had shown a positive correlation of the sensitivity to Apo-2L with the expression of DR4 and DR5, or with the intracellular levels of FLAME-1.3,4,27,28In contrast, as also previously reported for other cell types,3,18 27 data presented in Figure 1C do not show such a correlation in the leukemic cells. As compared with other cell types, Jurkat cells, which demonstrated the highest sensitivity to Apo-2L, expressed higher levels of DR5, but lacked the expression of DR4 (Figure 1C). Inconsistent with their increased sensitivity to Apo-2L, Jurkat cells expressed more DcR2 and FLAME-1 (I-FLICE) although their survivin levels were the lowest of the 3 cell types (Figure 1C). All cell types expressed barely detectable levels of DcR1 (data not shown).

Apo-2L induces apoptosis of HL-60, U937, and Jurkat cells.

Cells were exposed to the indicated concentrations of Apo-2L for 24 hours (A). Following this, the percentage of apoptotic cells were determined (see “Results”). Apo-2L induced the processing and down-regulation of caspase-8, Bid, caspase-9, caspase-3, and XIAP, as well as cytosolic accumulation of cyt c in Jurkat cells (B). Following exposure of Jurkat cells to 100 ng/mL of Apo-2L for 24 hours, cell lysates were obtained and Western analyses of the indicated proteins were performed (see “Results”). Western analyses of DR4, DR5, DcR2, cIAP-1, XIAP, I-FLICE (FLAME-1 or cFLIP), and survivin in HL-60, U937, and Jurkat cells (C).

Apo-2L induces apoptosis of HL-60, U937, and Jurkat cells.

Cells were exposed to the indicated concentrations of Apo-2L for 24 hours (A). Following this, the percentage of apoptotic cells were determined (see “Results”). Apo-2L induced the processing and down-regulation of caspase-8, Bid, caspase-9, caspase-3, and XIAP, as well as cytosolic accumulation of cyt c in Jurkat cells (B). Following exposure of Jurkat cells to 100 ng/mL of Apo-2L for 24 hours, cell lysates were obtained and Western analyses of the indicated proteins were performed (see “Results”). Western analyses of DR4, DR5, DcR2, cIAP-1, XIAP, I-FLICE (FLAME-1 or cFLIP), and survivin in HL-60, U937, and Jurkat cells (C).

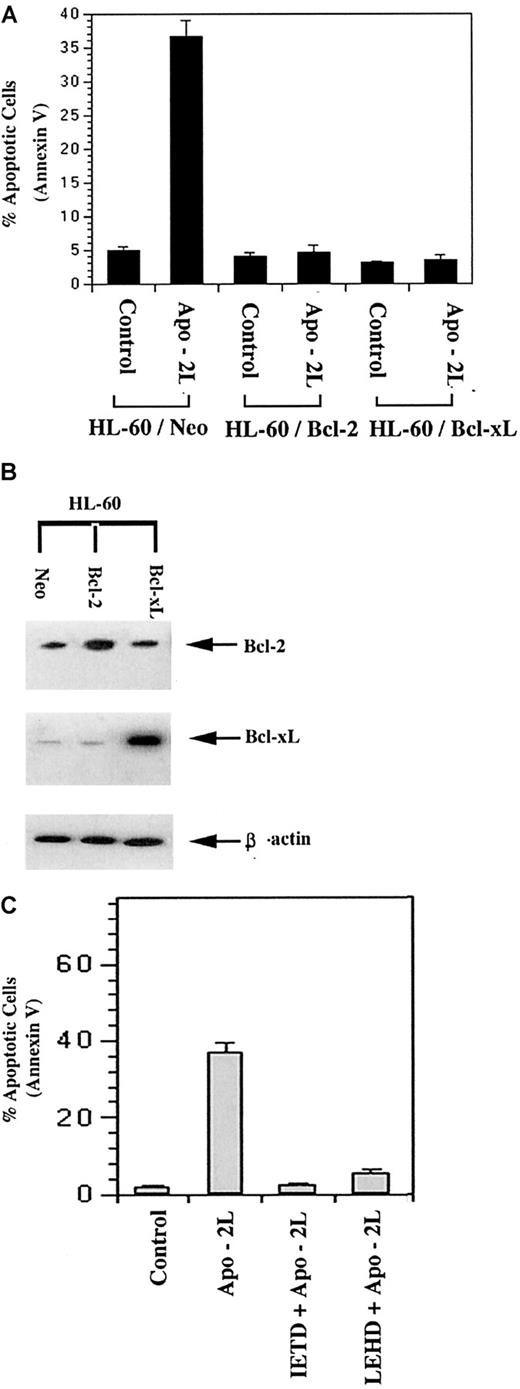

Apo-2L–induced apoptosis of leukemic cells was inhibited by overexpression of Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL

We examined the effect of Bcl-2 or Bcl-xLoverexpression on Apo-2L–induced apoptosis of HL-60 cells. As compared with HL-60/neo cells, HL-60/Bcl-2 and HL-60/Bcl-xL cells possess approximately 3-fold higher levels of Bcl-2 and 5-fold higher levels of Bcl-xL, respectively (Figure2B).35 Exposure to 100 ng/mL of Apo-2L induced apoptosis of 37.0% ± 2.0% of HL-60/neo cells. However, Apo-2L–induced apoptosis was suppressed in HL-60/Bcl-2 and HL-60/Bcl-xL cells (Figure 2A). This supported the observation that, in HL-60 cells, Apo-2L triggered the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis. This conclusion was further supported by the finding that cotreatment with the relatively specific caspase-9 inhibitor z-LEHD-fmk was as effective as the caspase-8 inhibitor z-IETD-fmk in suppressing Apo-2L–induced apoptosis of HL-60 cells (Figure 2C).

Overexpression of Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL inhibited Apo-2L–induced apoptosis of HL-60 cells (A).

Following treatment with 100 ng/mL of Apo-2L, the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by Annexin V staining and flow cytometry (A). Western blot analyses of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL levels demonstrating overexpression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xLin HL-60/Bcl-2 and HL-60/ Bcl-xL cells, respectively. Levels of β-actin served as the loading control (B). Cotreatment with the relatively specific caspase-8 inhibitor (z-IETD-fmk, 50 μmol/L) or caspase-9 inhibitor (z-LEHD-fmk, 100 μmol/L) inhibited Apo-2L–induced apoptosis (C).

Overexpression of Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL inhibited Apo-2L–induced apoptosis of HL-60 cells (A).

Following treatment with 100 ng/mL of Apo-2L, the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by Annexin V staining and flow cytometry (A). Western blot analyses of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL levels demonstrating overexpression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xLin HL-60/Bcl-2 and HL-60/ Bcl-xL cells, respectively. Levels of β-actin served as the loading control (B). Cotreatment with the relatively specific caspase-8 inhibitor (z-IETD-fmk, 50 μmol/L) or caspase-9 inhibitor (z-LEHD-fmk, 100 μmol/L) inhibited Apo-2L–induced apoptosis (C).

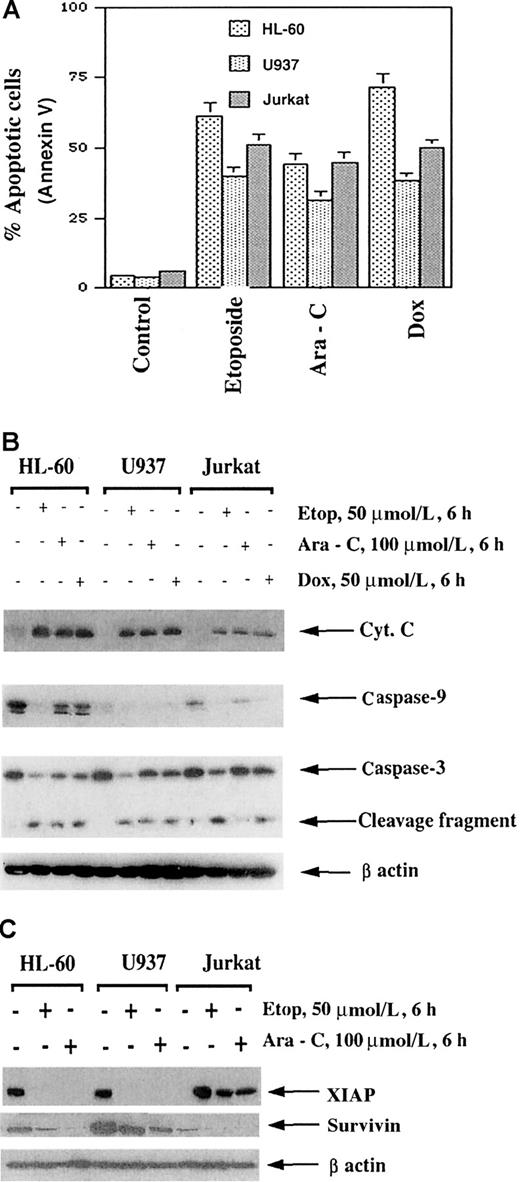

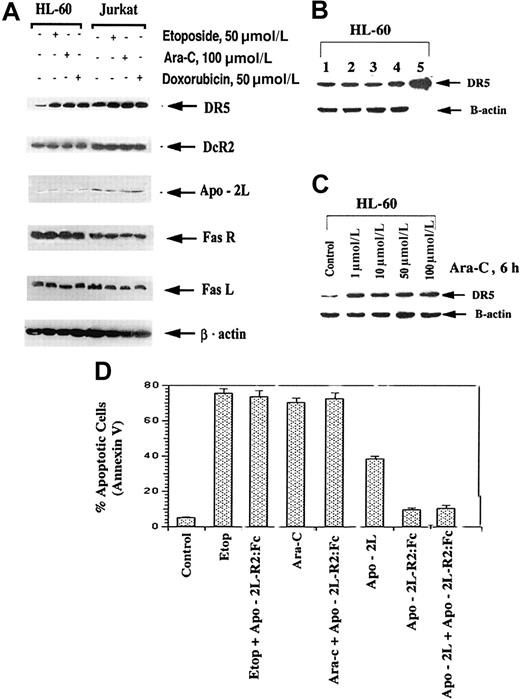

Etoposide-, Ara-C–, or doxorubicin-induced apoptosis is associated with up-regulation of DR5 but not DR4, Fas, or DcR1 and DcR2

Etoposide, Ara-C, and doxorubicin are commonly used antileukemic drugs. With the goal of preclinically investigating the antileukemic activity of novel combinations of Apo-2L with relatively high but clinically deliverable doses of etoposide, Ara-C, or doxorubicin, we first determined the sensitivity and molecular cascade of apoptosis triggered by these drugs in HL-60, U937, and Jurkat cells. Figure3A clearly demonstrates that high but clinically achievable and relevant doses of etoposide, Ara-C, and doxorubicin induced apoptosis of approximately 30% to 75% of the leukemic cells. As also previously reported by us,35,36these drugs triggered the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis by inducing the cytosolic accumulation of cyt c as well as the processing of caspase-9 and caspase-3 (Figure 3B). Treatment with etoposide, Ara-C, and doxorubicin (not shown) was also associated with down-regulation of XIAP and survivin levels (Figure 3C). XIAP has been previously reported to be processed during Fas-mediated apoptosis,37 while survivin expression is cell-cycle phase–dependent and is down-regulated during the nonmitotic phases.38Importantly, treatment with etoposide, Ara-C, or doxorubicin induced DR5 levels in HL-60 and Jurkat cells (Figure4A). This was also observed to a lesser extent in U937 cells (data not shown). In contrast, DcR2, Apo-2L, FasL, and Fas levels remained unaffected (Figure 4A). In all cell lines, DcR1 levels were barely detectable (data not shown). Figure 4B-C shows that exposure of HL-60 cells to 1.0 μmol/L or higher Ara-C for 6 hours or longer was necessary to produce an increase in DR5 levels. Lower levels and shorter exposure intervals to Ara-C did not increase DR5 levels in any cell type (data not shown). Although not shown, treatment with Ara-C, while markedly increasing DR5, reduced DR4 levels in HL-60 cells. This was not observed in the other cell types, which express very low levels of DR4 (data not shown).

Etoposide (50 μmol/L), Ara-C (100 μmol/L), and doxorubicin (50 μmol/L) induced apoptosis of HL-60/neo, U937, and Jurkat cells.

Cells were treated with the drugs at the indicated concentrations for 6 hours followed by incubation for 18 hours in drug-free medium. After these treatments, the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by Annexin V staining followed by flow cytometry (A). Molecular events of apoptosis induced by etoposide, Ara-C, or doxorubicin (B). Cells were treated with the indicated drugs for 6 hours, and then cell lysates were obtained for Western analyses of procaspase-3, procaspase-9, cytosolic cyt c, and Bid protein. Alternatively, Western analysis of XIAP and survivin was performed on the cell lysates (C) (see “Results”).

Etoposide (50 μmol/L), Ara-C (100 μmol/L), and doxorubicin (50 μmol/L) induced apoptosis of HL-60/neo, U937, and Jurkat cells.

Cells were treated with the drugs at the indicated concentrations for 6 hours followed by incubation for 18 hours in drug-free medium. After these treatments, the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by Annexin V staining followed by flow cytometry (A). Molecular events of apoptosis induced by etoposide, Ara-C, or doxorubicin (B). Cells were treated with the indicated drugs for 6 hours, and then cell lysates were obtained for Western analyses of procaspase-3, procaspase-9, cytosolic cyt c, and Bid protein. Alternatively, Western analysis of XIAP and survivin was performed on the cell lysates (C) (see “Results”).

Etoposide, Ara-C, and doxorubicin increase DR5 levels in HL-60 and Jurkat cells (A).

Following exposures of HL-60 and Jurkat cells with the indicated drug concentrations, DR5, DcR2, Apo-2L, Fas, Fas L, and β-actin levels were determined by immunoblot analyses (see “Results”). Effect of exposure intervals to Ara-C on DR5 levels of HL-60 cells (B). HL-60 cells were exposed to 1.0 μmol/L Ara-C for 6 hours. Cell lysate of untreated (lane 1), or drug-treated cells after 2 (lane 2), 4 (lane 3), 6 (lane 4), and 24 hours (of which 18 hours were in drug-free medium) (lane 5) were subjected to immunoblot analysis of DR5 levels (see “Results”). Levels of β-actin were used as the loading control. Effect of the dose of Ara-C on DR5 levels (C). HL-60 cells were exposed to different concentrations of Ara-C for 6 hours. Following this, immunoblot analysis of DR5 levels was performed; β-actin levels were used as the loading control.

Etoposide, Ara-C, and doxorubicin increase DR5 levels in HL-60 and Jurkat cells (A).

Following exposures of HL-60 and Jurkat cells with the indicated drug concentrations, DR5, DcR2, Apo-2L, Fas, Fas L, and β-actin levels were determined by immunoblot analyses (see “Results”). Effect of exposure intervals to Ara-C on DR5 levels of HL-60 cells (B). HL-60 cells were exposed to 1.0 μmol/L Ara-C for 6 hours. Cell lysate of untreated (lane 1), or drug-treated cells after 2 (lane 2), 4 (lane 3), 6 (lane 4), and 24 hours (of which 18 hours were in drug-free medium) (lane 5) were subjected to immunoblot analysis of DR5 levels (see “Results”). Levels of β-actin were used as the loading control. Effect of the dose of Ara-C on DR5 levels (C). HL-60 cells were exposed to different concentrations of Ara-C for 6 hours. Following this, immunoblot analysis of DR5 levels was performed; β-actin levels were used as the loading control.

Although treatment with the antileukemic drugs did not increase Apo-2L expression, to confirm that etoposide- or Ara-C–induced apoptosis was not mediated by even a transient induction of Apo-2L and that triggering of DR5-mediated apoptosis, we compared the effect of cotreatment with Apo-2L-R2(DR5):Fc on apoptosis induced by the antileukemic drugs or by Apo-2L. If treatment with the antileukemic drug produced any Apo-2L in the culture medium of the cells, apoptosis triggered by this, through induced DR5, would be blocked by Apo-2L-R2. As shown in Figure 4D, cotreatment with Apo-2L-R2:Fc (20 ng/mL) inhibited Apo-2L– but not etoposide- or Ara-C–induced apoptosis of HL-60 cells.

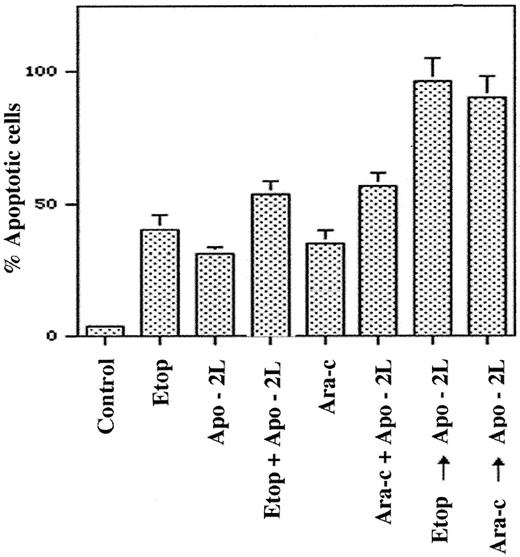

Pretreatment with the antileukemic drugs increases Apo-2L–induced apoptosis

To determine the functional significance of DR5 induction by the antileukemic drugs, we compared the apoptotic effects of the sequential treatment with Ara-C, etoposide, or doxorubicin followed by Apo-2L (6 hours of the drug followed by drug washout and 18 hours of Apo-2L treatment) with those of the drug administered alone or together with Apo-2L. Figure 5 demonstrates that significantly more apoptosis was observed following a sequential treatment of HL-60 cells with etoposide or Ara-C followed by Apo-2L, as compared with treatment with Apo-2L or either of the drugs alone. Sequential treatment with the drug followed by Apo-2L also yielded more apoptosis than cotreatment with Apo-2L plus Ara-C or etoposide (P < .01). To adequately assess the potentiating effects of pretreatment with the antileukemic drugs on Apo-2L–induced apoptosis, relatively lower concentrations of etoposide or Ara-C were used for these studies. Although not shown, a sequential treatment with Ara-C or etoposide followed by Apo-2L was also more effective than treatment with the reverse sequence of Apo-2L followed by either of the 2 drugs. For example, exposure to the reverse sequence of Apo-2L (100 ng/mL) for 18 hours followed by Ara-C (10 μmol/L for 6 hours) produced apoptosis of only 47% ± 6% of cells, as compared with apoptosis of 88% ± 9% cells observed with treatment with Ara-C followed by Apo-2L. Similar observations were made when doxorubicin was administered with Apo-2L, and Jurkat cells were used to investigate these treatment schedules (data not shown).

Pretreatment with etoposide or Ara-C enhances Apo-2L–induced apoptosis of HL-60 cells.

HL-60 cells were exposed to etoposide (5.0 μmol/L, 6 hours), Ara-C (10.0 μmol/L, 6 hours), or Apo-2L (100 ng/mL, 18 hours), and the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined at the end of 24 hours (see “Results”). Cells were also exposed to etoposide plus Apo-2L (total 24 hours), or Ara-C plus Apo-2L (total 24 hours). Alternatively, cells were treated with etoposide (5.0 μmol/L, 6 hours), followed by Apo-2L (100 ng/mL, 18 hours) or Ara-C (10.0 μmol/L, 6 hours), followed by Apo-2L (100 ng/mL, 18 hours). Following these treatments, the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by Annexin V staining and flow cytometry (see “Results”).

Pretreatment with etoposide or Ara-C enhances Apo-2L–induced apoptosis of HL-60 cells.

HL-60 cells were exposed to etoposide (5.0 μmol/L, 6 hours), Ara-C (10.0 μmol/L, 6 hours), or Apo-2L (100 ng/mL, 18 hours), and the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined at the end of 24 hours (see “Results”). Cells were also exposed to etoposide plus Apo-2L (total 24 hours), or Ara-C plus Apo-2L (total 24 hours). Alternatively, cells were treated with etoposide (5.0 μmol/L, 6 hours), followed by Apo-2L (100 ng/mL, 18 hours) or Ara-C (10.0 μmol/L, 6 hours), followed by Apo-2L (100 ng/mL, 18 hours). Following these treatments, the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by Annexin V staining and flow cytometry (see “Results”).

Discussion

Several reports have demonstrated the sensitivity and molecular correlates of Apo-2L–induced apoptosis of cancer cells.3,4,25-28 Some of these reports have also shown that chemotherapeutic agents increase Apo-2L–induced apoptosis of epithelial cancer cells.25-28 In the present studies, however, we demonstrate for the first time that Apo-2L signals apoptosis of acute leukemia HL-60, U937, and Jurkat cells mainly through the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis. Since these cells lack a functional p53wt, our data also indicate that Apo-2L–induced apoptosis is independent of p53 status. This has also been demonstrated for other tumor cell types.27Although the Apo-2L–sensitive acute leukemia cell types studied here expressed DR5 and, in HL-60, also DR4, the level of expression of these death-signaling receptors did not correlate with the sensitivity to Apo-2L. This correlation has been demonstrated by some but not all previously reported studies.3,25,27 DcR1 and DcR2 do not transduce Apo-2L–induced death signal.1,2 DcR2 has also been shown to inhibit apoptotic signaling by inducing NFkB activity.39 Ectopic overexpression of DcR1 and DcR2 has been shown to inhibit Apo-2L–induced apoptosis.1,40However, in the present studies, the level of expression of the decoy receptors did not correlate with resistance to Apo-2L–induced apoptosis of the leukemic cells. These findings are similar to other previously reported observations about melanoma and breast cancer cells.3,25,41 We also did not find any correlation between intracellular FLAME-1 (cFLIP or I-FLICE) levels and the sensitivity of the leukemic cells to Apo-2L–induced apoptosis. The spliced variants of cFLIP are the long form (cFLIPL) and short form (cFLIPS). cFLIPL, which was the variant detected in our immunoblots by the antibody used, has the inhibitory effect on Fas L- and TRAIL-induced DISC activity.41Although, similarly to our findings, increased levels of cFLIP have been shown to inhibit apoptosis owing to death receptor signals and have been correlated with resistance to Apo-2L–induced apoptosis,27,42-45 this has not been observed in all cell types.3 Since FLAME-1 exerts its inhibitory effect by binding to FADD and caspase-8, this dominant-negative effect on the activity of the DISC may depend on the levels and role of FADD in mediating Apo-2L–induced apoptosis.5

Treatment of the acute leukemia cells with Apo-2L clearly resulted in the processing of caspase-8, Bid, caspase-9, and caspase-3, as well as the cytosolic accumulation of cyt c. This indicates that Apo-2L–induced processing and activation of caspase-8 triggered caspase-3 activity through the intrinsic (mitochondrial) pathway of apoptosis. Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL overexpression have been previously shown to exert their inhibitory effect on apoptosis by blocking the release of cyt c and mitochondrial ΔΨm induced by a variety of apoptotic stimuli that engage the intrinsic pathway to apoptosis.35,36 Accordingly, present studies demonstrate that overexpression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xLinhibited Apo-2L–induced apoptosis of HL-60 cells. Keogh et al46 have recently reported that in CEM cells with known overexpression of Bcl-2, UV- but not TRAIL-induced cytosolic accumulation of cyt c and apoptosis was blocked. However, in this report they did not show Bcl-2 overexpression, raising the possibility that Bcl-2 expression was relatively low. The conclusion that Apo-2L predominately engages the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis in these cells is also confirmed by our observation that the inhibition of caspase-9 activity by z-LEHD-fmk was as effective as the inhibition of caspase-8 by z-ITED-fmk in suppressing Apo-2L–induced apoptosis of HL-60 cells. These findings suggest that acute leukemia HL-60 cells may be of the type II variety with respect to the death receptor–initiated apoptotic signaling, as was previously found for CD95 signaling.47 Apo-2L–induced activity of the effector caspases, such as caspase-3, was also associated with down-regulation of XIAP levels. As has been previously reported, this may be due to XIAP processing by caspase-3.37

Previous studies and data presented here demonstrate that antileukemic drugs that cause DNA damage, eg, etoposide, Ara-C, and doxorubicin, also trigger the mitochondrial or intrinsic pathway of apoptosis.16,34-36 The resulting cytosolic accumulation of cyt c produces Apaf-1–, dATP-, and caspase-9–mediated activation of caspase-3,34-36 all of which can be inhibited by overexpression of Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL.34-36 In the present studies, we have extended these observations and demonstrated that etoposide- and Ara-C–induced caspase activity and apoptosis are also associated with down-regulation of the levels of XIAP and survivin. Although survivin has not been shown to be processed by caspases, its levels are low in nonmitotic phases of the cell cycle and increase markedly during mitosis.38 Since treatment with relatively high but clinically achievable and relevant doses of Ara-C, etoposide, or doxorubicin, as employed in the present studies, is known to arrest and increase the percentage of acute leukemia cells in the premitotic phases (G1, S, or G2) of the cell cycle, this may lower survivin expression in the drug-treated cells. Recent studies have suggested that chemotherapeutic agents might trigger apoptosis by inducing Fas or Fas L and activating the Fas-dependent pathway to apoptosis.48-50 However, other reports have shown that chemotherapeutic agents induce apoptosis through a Fas-independent pathway of apoptosis.51 52 Data from present studies also support this by demonstrating that etoposide, Ara-C, and doxorubicin did not induce Fas or Fas L. Treatment with these drugs also did not increase the expression of Apo-2L. Furthermore, cotreatment with a fusion protein containing the extracellular domains of DR4 or DR5 fused to the immunoglobin Fc region, ie, Apo-2L R1, or R2:Fc, did not inhibit etoposide- or Ara-C–induced, but blocked Apo-2L–induced, apoptosis. These data make it unlikely that FasL or Apo-2L expression is induced by etoposide or Ara-C or that the ligation of DR5 in the acute leukemic cells plays any significant role in apoptosis induced by these antileukemic drugs.

Although Apo-2L expression was not enhanced, treatment with etoposide, Ara-C, and doxorubicin increased DR5 but not DR4 levels in the 3 acute leukemia cell types. This was observed after treatment with a threshold concentration and an exposure interval of each of the drugs. As noted above, these concentrations of the drugs are clinically achievable during the administration of induction therapy in relapsed leukemias with relatively high doses of these drugs. Previous reports have implicated p53 and NFkB as the transactivating factors in DR5 and DR4 up-regulation by DNA-damaging drugs such as etoposide or doxorubicin.18 53 Although the role of p53wtfunction in mediating DR5 up-regulation by the antileukemic drugs in the acute leukemia cells studied here can be excluded, NFkB may have been involved in mediating this effect. Regardless of the transcriptional activator involved in DR5 induction, the results presented here indicate that the increased DR5 levels due to treatment with antileukemic drugs should preferentially potentiate Apo-2L–induced apoptosis when exposure to Apo-2L follows treatment with the antileukemic drug. This was corroborated by our findings, which show that pretreatment of the leukemic cells with each of the 3 antileukemic drugs yielded more Apo-2L–induced apoptosis than treatment with Apo-2L, the drugs alone, or even cotreatment with Apo-2L plus each of the antileukemic drugs, or by the reverse sequence of exposure to Apo-2L followed by the antileukemic drugs.

In summary, although Apo-2L and each of the antileukemic drugs studied here are shown to engage the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis by up-regulating DR5 levels, pretreatment with the drugs increases the responsiveness to Apo-2L–induced apoptosis. These data suggest a strategy to rationally combine Apo-2L and conventional antileukemic drugs in a regimen that would optimize the antileukemic activity and induce apoptosis of acute leukemia cells, which lack a functional p53wt.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Kapil Bhalla, Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, 12902 Magnolia Dr, MRC 3 East, Rm 3056, Tampa, FL 33612; e-mail: bhallakn@moffitt.usf.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal